|

|

|

[Page 170]

Avrom Bialilev, Former Secretary of the Sokolov Kehile, (Gevatayim)

Pinkhas Rafalovitsh, (Tel Aviv)

Translated by Tina Lunson

According to historical sources the establishment of the Jewish community in Sokolov dates from the 15th century. In 1665 there was mention of local Jews in connection with the privilege that the proprietor of Sokolov and Vengrov, Jan Krashinski, had issued to encourage the settlement of Jews.

The privilege of the year 1665 honored all the rights that the Jews held from the earlier proprietors of Sokolov and permitted them to have their own court of Jewish law. Sokolov was then handed over to a new proprietor (Mikhal Aginski) and he confirmed the privileges to develop artisanry and trade.

In the 18th century the town proprietor (Jan Aginski) set out statutes about gathering the heads of the community each year on the second Sunday after the holiday of Holy Jan, in the following manner: The heads of the community wrote down the names of all the heads of households who paid no less than 25 guilden a year sklodke. The names were to be written on individual cards and given to the town Rov [rabbi]. The Rov placed all the cards from the whole community in a sack, shook it three times and withdrew five cards with his right hand. He read out each card and recorded it in a list. The five elected were to choose the community managers who would direct all the affairs of the Jews.

Unfortunately the community records were destroyed during the two great fires that occurred in the town. And the last

[Page 171]

record book that was found with the Rov and judge Mordkhe Halbershtat of blessed memory went missing in the time of the dark Hitler epoch. Thus we have no details of community life until the tsarist era.

Under Tsarist Rule

In the time of tsarist rule in Poland the so-called dozor buzshnitsi or synagogue council was founded. It was composed of three members plus the town Rov. That council, along with the mayor of the town, directed the community matters and taxed the Jews on their own houses with a community tax (etat), to sustain the Rov and the community institutions such as the shul, mikve, cemetery and so on. The tax lists and administrative work were overseen by an office of the local magistrate.

Of the last dozores – who lived in the time when the tsarist powers were driven out of Poland – Rov Alter Rozenblum (son of Alter Dovid z”l) was well known; he was a Talmud scholar, author of a book about the laws of blessings, and he had a little bank business in his house; Hersh Tuvye Ber, a representative householder; Meyshe Moshezon, a ladies' tailor, gabay of the khevre kadisha [burial society] and also Rov of the town; and Rov Yitskhak Zelig Morgnshtern zts'l (Sokolov rebi, a grandson of the Kotsker Rebi Mendele zts”l).

The appointing of a town rov, a ritual slaughterer, a cantor or even a bathhouse attendant called for great oversight. The process created factions and went on for a long and stubborn fight until the candidate was accepted.

It often even came to an intervention by the local authorities, and in the best case to arbitration by outside rabonim. The disputes against a bathhouse attendant went so far that once the bathhouse was burned and that led to the explosion of a water boiler.

Community Properties

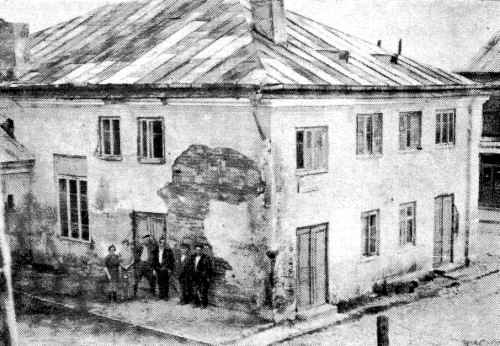

|

|

| The new study-house [beys-medresh] |

Social Help

Thanks to the initiative of a group of young people, a place for the poor sick was founded, where one could borrow various instruments – hot-water bags, cupping glasses and so on – and receive medical help.

The loan office played a large role in the town, as it provided almost the whole Jewish population with loans and savings accounts. The fund was directed by Hersh Tuvye Ber of blessed memory and Dovid Tsukerman and with special thanks, Mordkhay Elenberg (in Israel).

Although the community council did not involve itself with social support,

[Page 174]

there were several well-to-do men and women who from time to time collected khale loaves for shabes, bread, and other goods to distribute among the needy.

Sources of Livelihood in Sokolov

Shoemaking was the chief source of livelihood and reached into the far corners of Russia, even the far East. Approximately 300 families were involved with it. Brokers came to Sokolov from distant places in Russia to buy up boots. There were also a significant number of tailors in town and fur coat makers, who carried their products to markets in other towns. A large part of the Jewish population consisted of grain merchants.

|

|

| The mikve [ritual bath] |

Village merchants went around to the villages of the whole Sokolov region from Sunday until Friday, and bought pelts and various agricultural products from the peasants. As in every town, there were also porters, wagon-drivers, brokers and Jewish teachers of children. As well, there was a large number of large and small food and other kinds of shops.

[Page 175]

The First World War

The quiet, almost idyllic, way of life in Sokolov went on without substantial change over long generations until the First World War. During WW I dozens of homeless families began coming from different places in Poland, wherever the front was active.

With much devotion the local community did all it could to alleviate the fate of the homeless. A committee was formed to provide bread for them and roofs over their heads.

With the occupation of Sokolov by the German military, a couple of dozen Jews were felled by the withdrawing Russian pogromists the Cossacks.

The economic situation in Sokolov became very difficult; people simply began to starve and typhus and other diseases spread through town.

In 1916 the German administration published a statute that brought order to community life, introduced general, proportional and secret elections to the Jewish community council institutions, and broadened the competency of the kehile that carried a religious character.

Elected as council dozores were Yeshaye Shafran, Meyshe Moshezon, Hersh Tuvye Ber, Kh. Sh. Rozenboym and Yeshaye Landoy. Avrom Bialilev was designated as Secretary.

For the first time the kehile carried out a registration of the Jewish population. The office of the kehile was in one of the side rooms of the shul, and later in a room at the new study house.

The kehile administration at first worked out its yearly budget independently. It was busy bringing order to all the matters of the kehile, introducing order to the cemeteries, and working out a plan for the graves with aisles and numbers that were previously not there.

Then the council busied itself with renovating and freshening the shul. They also had an ark built for the Torah scrolls, adorned with beautiful wood carvings. For this they engaged two special woodcarvers from Mezshritsh. So it is worth emphasizing the great service of the first Jewish Secretary of the magistrate, Hersh Grinberg, who put much toil into renovating the shul and the holy ark.

[Page 176]

The “Joint”

The American Joint Distribution Committee helped the Jewish population out in their difficult economic situation. For that goal a committee was elected that operated the free kitchen from which almost the entire Jewish population of Sokolov benefited. The heads of that committee were Rakatsh, Binyumin Rubinshteyn, Pinkhas Tshernitski, Binyumen Elnberg, Mordkhe Elnberg and others.

An aide committee, Soymekh noyflim, was created at that time thanks to the initiative of the Jewish community, which was concerned with material and medical help for the poor. Heading that committee were Hersh Keyt, Leyb Altman of blessed memory, Avrom Ayzenberg and others. Barukh Dabzshinski was Secretary.

Communal Work

Many changes entered into Jewish life in Sokolov during the time of the German occupation. Electric lights replaced the oil lamps, a change brought about by Yeshaye Shafran, the builder of the electric station in town.

A large number of the Jewish youth switched their cloth caps for fedoras, and the long frock coat for a short jacket. Two libraries were founded and several parties: Mizrakhi, Tsionim klalim, Poaley Tsion left, Poaley Tsion right, the Bund and others.

The town was visited by numerous officials, literati, singers and concert ensembles. A Yiddish folks-school was founded, directed by Jewish teachers, and the kheyder Yanve by the Mizrakhi party.

The Rise of the Polish State in 1918

In the early times of the rise of the Polish state, the Jewish council management worked on the same basis as before. Because of the frequent government demands in the time when the Endetsye were part of the government, the Jewish council transformed into a kind of national institution that had to concern itself with Polish issues too, in order to properly defend the Jewish population against discrimination and excesses.

At the time of the elections to the Polish parliament, the kehile took an active part

by helping to create the nationalities block by which Jews and Germans in the Sokolov area could vote for the nationalities slate.

[Page 177]

The Polish kehile statute was published in 1923 and elections took place for all the Jewish political parties in existence in our town. The battle for votes was intense. There were election meetings during which speakers for various parties fought one another. A council of thirteen persons and a management of eight persons were elected.

The head of the Kehile management was Skshidlover and of the council, Kopovi. As dozores in the Polish era those elected were Skshidlover (Mizrakhi), Lustigman (Aguda), Keyt (Aguda), Yisroel Goldfarb (Aguda), Kopovi (Mizrakhi), Yisroel Man (Poale-Tsion Left), M. Lashinski (Tsionistn), Tsitinski (Handworkers), Avrom Vaynberg (Handworkers), Ferger (Handworkers), B. Rafalovitsh (Mizrakhi) though Y. Goldfarb (Aguda) stepped into his place, Zarembski (Poale-Tsion Right), Sender Rubinshteyn (Mizrakhi), M. Elster (Handworkers), Radzinski (Mizrakhi), and Shpadl (Aguda).

The kehile worked out its budget which was approved by the council and the local government.

The budget included, besides the necessities of the kehile, also various subsidies for Keren-kayemet, Keren-ha'yesod, Beys-Yankev schools, and also support for the local social institutions such as Soymeykh noyflim, TOZ, Talmud Torah, Mizrakhi, the shul and others. For the election a block was created of handworkers and the Aguda against Mizrakhi and Zionism.

During that time the American Joint was working in Poland and thanks to their support the kehile carried out a foundational renovation of the public bath where it installed tubs, showers and mikves.

The Ritual-Slaughter Question

The kehile spent a great deal of its toil and energy bringing order. The organization of Jewish ritual slaughter of animals for food, which was in the hands of private practioners, was, according to an agreement with the slaughterers, given over to the kehile.

The kehile management had to endure an extended struggle with the slaughter limitations which the Polish parliament deputy Mrs. Pristorova introduced in the Polish parliament. They had to

[Page 178]

constantly fight to maintain the necessary consignment of kosher slaughter for the Jewish population.

A slaughter house for chickens was built, which made it possible to hold control over the organization of slaughter, and it prevented contamination by the slaughterers, who had before slaughtered privately in various places.

The Jewish council was in fact the representative of the Jewish population in the town's various ceremonial and state cultural events. It also defended Jews in the time of the boycott actions against Jewish trade that the Polish anti-Semitic organizations conducted.

At the time of the greatest boycott tension in 1938 – when on a market day a pogrom broke out in town against Jewish traders and shops ¬– the local authorities were alerted and also the Jewish parliament deputies. Those suffering were registered as they needed help due to the rapid approach of Passover.

The Jewish council management often coordinated its activities with Jewish members of the town council, which would hold its meetings in the kehile management venue. The Jewish council management worked under the leadership of kehile chairman Khayim Yankev Shpadel until the last moment when the Second World War broke out.

Eliezer Rubinshteyn, “Shedletser vokhnblat”, 1937

Translated by Tina Lunson

Historical documents and materials are almost non-existent in Sokolov; the great fire in 1910 destroyed a lot and thus it is difficult to create a picture of that one-time Jewish life in the town.

One of the remaining documents of the distant past is the pinkes of the “Khevre kadishe tehilim” which began the written record in sav-kuf-ayin (1810).

That record-book consists of 172 pages of large parchment. The inscription on the title page accords: “Relating to the holy psalms society Sokolov, Shabsey Yehuda the ritual slaughterer”; the first record in the book was made on “the first day of Iyar sav-kuf-ayin lamed pey-kuf (1810).

After the introduction about the significance of reciting psalms – written in large manuscript letters – come seventeen precepts for the society which deal with the obligations and assignments of the group members.

According to the precepts, each person who belongs to the society obligates himself to recite daily twenty-one chapters of psalms and do that not fast, but word for word; the one who stands at the cantor's stand in shul must possess a pleasant voice, joy and intention of the heart (precepts 1, 2, and 3).

About mutual devotedness and friendship among the members the precepts 6 and 7 – which obligate the entire society to recite psalms – instruct that if one member becomes sick, and the same in case one has died, ten people are obliged to hold an all-night study session and attend to prayers the deceased's home during the seven days of shive.

The society is also obliged in precept 8 to observe the yortsaytn of the late holy Rov Ben Rokhl (tes”vov) and the late well-known genius Rov Shabsay ben Pesl who died with a good reputation (28 Tamuz).

The procedure for taking new members into the society was not an easy one. Requests received to become a member of the society were considered only at the general meeting, during the interim days of sukes (precept 9). The requests were given to the “manager of the month” who presented them to eighteen people. The registration fee amounted to

[Page 180]

not less than “fourteen Polish gold coins and honey-cake and brandy for the other people” (precept 10).

The same eighteen people who also decided about exclusion from the society stood for elected overseers, managers, trustees and three accountants (precept 11). The members' dues amounted to one large Polish coin per week per person (precept 13). The punishment for not coming to recite psalms “with the group” amounted to one “large Polish” on a weekday, and three on Shabes or a holiday. With that money they held a big feast on every new moon.

These were the precepts of the society, accepted and established on the first day of Iyar sav-kuf-ayin lamed pey-kuf (1810) and signed with dozens of signatures.

Revenue for the society in that same year tes-kuf-ayin was 498 z'rsh and the expenses were 774 z'rsh.

In order to allow that women and children could also belong to the society the terms for them to join were lighter than for others.

All 172 pages are closely written and contain records, notes and inscriptions about meetings, accepting and excluding members, punishments and so on. The date of the last page is the year sav-reysh-nun-hey, although opposite, on the previous page of the record-book a later date is given – and appears to be the last – the date of Rosh khoydesh Sivan sav-reysh-samekh-zayin, when the continuation of the ongoing chronological inscriptions in the Pinkes were interrupted.

The last inscription in the book was made by Ben-Tsion Shamesh, who died not long before the Second World War at the age of 84 years.

Pinkhas Rafalovitsh (Tel Aviv)

Translated by Tina Lunson

The Jewish cooperative loan and savings fund in Sokolov was organized in 1907.

The chief initiator for establishing the above-mentioned cooperative institution in Sokolov was Mordkhe Elenberg. It was not easy for him to realize his idea. The skepticism of various city proprietors about the thought of a cooperative and the fear of something new delayed his final achievement. But thanks to the energetic work of Mordkhe Elenberg to inspire the necessary number of members needed, according to the laws, the loan fund could begin its activities.

The management of the loan fund consisted of the following distinguished proprietors of the town: Khayim Shmuel Rozenboym, Pinkhas Futerman, Note Finklshteyn, Khayim Leyb Levin, Nakhman-Yosl Morgenshtern, Kahyim Tuvye Ber and Mordkhe Elenberg as technical director of the loan fund.

About 200 loan funds existed at the time in Congress Poland. The program of all those institutions was to help the Jewish small traders and artisans with loans for longer terms with low interest.

The movement of organizing cooperative financial institutions in the towns and villages was lead and encouraged by the “YK'A” society, which supported them with generous financial help. The actual capital for the loan fund consisted of member contributions and deposits from the local Jewish population but the main capital came from the financial help of the “YK'A” society.

The management led an intensive campaign and raised the fund to a high economic factor in the town. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Jewish life was paralyzed. The members could not repay their loans.

The activity of the loan fund was interrupted.

[Page 182]

Reorganization

The rise of independent Poland significantly changed the economic structure of the country. Trade and artisanry revived with new investments corresponding to the new economic situation. Unfortunately the craftsmen had no financial opportunities to attain them. And the merchants were harried, in need of financial help to be able to produce the merchandise for their clients.

Considering the situation, the social-economic department of the Zionist organization in Poland decided to create a corporation that would concern itself with reorganizing the Jewish loan funds and would give them the necessary financial help for their activities. Thanks to the intensive work by that department, they organized the “Society for the Cooperatives Union” in Warsaw in a short period of time. The society reorganized the loan fund and gave financial help within the range of their abilities.

The “YK'O” and the “Joint”

The decision by the American Joint Distribution Committee and the YK'O to take part in financial help for the reorganization of the cooperative societies and loan funds was fundamental to the cooperative movement and quickened the tempo of the reorganization on stable foundations.

The representatives of the above-mentioned world-famous social association organized the “review association”, which administered the entire cooperative effort and was the central agency for the majority of the loan funds and folks-banks in Poland.

The heads of the review association were Dr. Mayer Kluml, Rafal Shereshevski, engineer A. Berkenheym and others. The review association also organized a board of inspectors of qualified cooperative activists like Khayim Shoshkes, Mikhelson, Goldfarb and others.

The inspectors visited each loan fund, specified the correct methods for their activity, organized new loan-funds and had supervision over them. The cooperative movement developed quickly and in a short time there were hundreds of loan-funds in Poland associated with the Central Bank for Cooperatives in Warsaw.

In 1920 the Jewish loan fund in Sokolov opened again, in Velvel Yospershteyn's house at Dluga Street 22. The administration

[Page 183]

was composed of Yankl Tikulski, Mendl Lashitski, Yitskhak Skole, Meyshe Meyshezon, Shabasil Perger, Platner and Binyumin Rubinshteyn.

The personnel were Yualke Shlafmits, Borekh Yisroel Yedlin and Meyshe Hokhberg (now in Israel). The loan fund in Sokolov developed broad activities. The number of members grew from year to year. The population had trust in its work, they brought their deposits to the loan fund; the fund's capital increased and thanks to that it had the possibility of giving its members larger loans.

Devaluation

In 1923 Poland underwent a devaluation of the Polish zloty, which brought about a terrible economic crisis. Trade and artisanry were as though paralyzed. The members who owed loans could not repay them. The financial basis of the loan fund collapsed and the danger of the liquidation of such an important institution was large. The managers of the loan-fund decided to mass all efforts to make its further existence possible. The management intervened with the review association and asked for their help to save the loan-fund from liquidation.

The review association came in return and approved a significant sum as a long-term loan, and thanks to that the loan-fund was saved from going under.

The Loan-fund Receives the Right to be a Bank

The Polish currency stabilized and the economic situation improved. The wholesalers again gave merchandise on credit against bills of exchange. The shops and workshops were no longer as empty as before and revenue rose. The enumerators counted the exchange bills precisely. The shopkeepers and handworkers complained because all of the bills of exchange were sent for collection to the Polish “Bank of Trade and Industry” – the only bank that existed in Sokolov. The small shopkeepers and artisans did not have any credit there and had to pay the exchange in the terms stipulated by 12 noon, or else the exchange could go into objection. If so, the wholesalers could not send their exchange bills for collection except in a bank. It was necessary to create a Jewish bank.

[Page 184]

Pondering the situation, the board and administration decided to reorganize the loan-fund as a bank. The general meeting of the members of the loan-fund happily accepted the decision.

The management undertook all the necessary steps and after intensive work and help from the review association, it received permission from them. On an auspicious day the sign of the loan-fund was replaced with a larger sign: “Bank for Small Traders and Handworkers”.

A board and managers were elected for the bank of the following members, in alphabetical order: Meyshe Grinberg, Aron Hendler, Avrom Zaionts, Khayim Zilberman, Mendele Lashitski, Meyshe Meyshezon, Meyshe Seber, Yisroel Fisher, Meyshe Perelshteyn, Alter Khayim Kapovoy and Binyumin Rubinshteyn and Pinkhes Rafalovitsh.

The Bank's Activities

With the opening of the bank the cooperative movement in Sokolov entered a new phase. Bills of exchange came in for collection from every corner of Poland. The volume of business at the bank increased several times over, deposits flowed in. Thanks to that it became possible to increase the quantity of loans for the members.

Plus the review association designated a certain amount of money for the disposition of the bank to make portfolios in the Central Bank for Cooperatives. In a word the Jewish folks-bank was a colossal factor for the Jewish shopkeepers and craftsmen to realize a livelihood for their families.

The small staff from the loan-fund was no longer enough for the broad activity of the bank. As the staff grew, Avrom Tsishinski was engaged as technical leader and Yitskhak Shlofmits as a second bookkeeper.

General Meeting

The annual general meeting of the bank was the event of the day. The excitement of the members and at the gathering was high and the debates were always in earnest, with attention and love for the institution. The speakers in the debates stressed the great importance of the bank for the Jewish masses, and the presentations were only in the direction of protecting the institution.

[Page 185]

Foreign Policy

Trouble came for Jews when the anti-Semitic economic “ovsham” politics of then-Minister Skladkovski rattled Jewish trade and production. The Endekes opened Christian shops and workshops in several towns and villages in Poland. A large number of Polish shops and workshops opened in Sokolov, which tore customers away from the Jewish stores. For half of the year Endeke gentile gangs stood in picket lines in front of Jewish shops and did not allow Christian customers to enter. The gentile youths often attacked the Jewish shopkeepers or artisans with stones, splitting their heads, because they would not lock up their shops. The situation was literally catastrophic for the smaller shopkeepers and the sellers in the market were literally going hungry. The difficult situation foretold a crisis for the bank.

The management struggled with self-sacrifice to sustain the existence of the bank in order to provide help for the Jewish traders and artisans in their hard battle against the anti-Semitic policies of the Polish government.

Other shopkeepers, artisans, wagon-drivers and village visitors tried with colossal bravery in their fight against the anti-Semitism, to retain their economic positions. Broken and hungry, they guarded the shops and workshops and did not let them be liquidated.

It is also worthwhile to mention that in the years from 1929 to 1930 a “Bank kupietski” (Merchants Bank) was founded in Sokolov. The founder and director of the bank was Leybush Rozenfeld of blessed memory. The larger merchants of the town were mostly concentrated there. The bank was included in the review board of the Aguda. The management was composed of: Rov Meyshe Morgenshtern, Hershl Zaltsberg, Tuvye Tsipelevitsh and others.

After the death of Leybush Rozenfeld a few years before the last world war, the bank was liquidated.

Nosn Fademberg (Los Angeles)

Translated by Tina Lunson

Sokolov was a town of craftsmen, small traders, village salesmen and laborers. They all worked hard for their piece of bread and they fulfilled the verse “by the sweat of your brow you will eat your bread” to its full measure.

The village-visiting salesmen went tens of viorsts by foot carrying heavy packs: shirts, cobbler's lasts, nails, pieces of leather, linens, scissors, needles, thread and other things to repair peasant shoes and clothing. In the packs they also carried talis un t'filin and a little food, so they would not have eat God forbid from the non-Jews.

A craftsman set out for the villages on Monday at dawn, in order to meet the peasants before they went out to work in the fields. If he got a little work, he would stop and open his pack and sit back. He would work until late at night by an oil lamp. He did not eat anything cooked, only bread and tea, and slept in the barn on some straw. If there was work for a whole week, that was good. If not he was off to seek work from other peasants. Friday at dawn he put his pack on his shoulders along with a few potatoes, greens and carrots which the “good peasant” had given him and with a pack full of gifts set off for home and the family for Shabes.

The Sokolov craftsmen worked “God's hours,” and from four or five in the morning one could hear sewing machines, the shoemakers' hammers clapping, , wood being planed, pelts being scraped, and iron being beaten at the forges. The craftsmen would work several hours, then go to daven, have a bite to eat, and go back to work until afternoon, have supper and work until late at night, never having eaten their fill. They somehow just got by all the weekdays, but Shabes lay as a heavy weight on each craftsman and laborer the whole week.

All the town residents hoped for the Thursday market day. It was often a joyful day for many, and for

[Page 187]

others, a disappointment. A whole week of livelihood for the family hung on the one day. Before dawn one could already hear the clatter of the peasant wagons and the clopping of the horse hooves on the stones of the paved streets. And as soon as the peasants had shown up in the market square our little town Sokolov became a noisy and happy place.

We would get up at dawn, go to the study house, daven quickly, often skipping things, and put in a little grievance to the Master of the universe so that He would also know it was market day in Sokolov.

The craftsmen put the wives and children to work carrying the boots, hats, fur coats, tin-ware and other produced items. Mountains of merchandise filled the narrow space between the walkways of Aron Karpe's house on Rogov Street, up to Ayzik Mendel the shoemaker's house at the corner of Shedlets Street.

The first to appear in the market square were the grain dealers. They ran fast as lightning from one wagon to the next, touching, looking, sticking a hand into the sacks to pull out a little grain and spreading it out across the palm of the hand, separating the grains to better see the size and quality. After that they started to bargain, settle on a price and drive home.

The real tumult began after the peasants had sold their produce, when they visited the craftsmen's shops. They talked in loud voices and shouted over one another in negotiating a price, so they could hardly understand each other. The stall-sitters – who spent the whole week across from the “brass house” near the new study-house – would carry their “creations” to the stalls and in a broken Polish tell the peasants what they had for sale: fresh rolls, kvass, soda-water, salt, pepper, herring, soap and other things one could not get in a village.

The Sokolov craftsmen would often drive around to the larger fairs in various towns and villages of Poland. For a day or two drive to a fair Leybke the wagon-driver pulled on his boots with the high cuffs. Across his broad shoulders hung a loose coat or a hooded fur cape as he drove from one craftsman to another, asking if they wanted to drive with him to the fair, and the sound of their horse-shoed boots rang up from the stone streets.

On the day of travel to the fair Leybke watered the horses,

[Page 188]

harnessed them to the long wagon, collected the merchandise and passengers and took to the road. He drove slowly, dozing through the night both in the winter snow and frost and in summer sometimes soaked by rain, until arriving at the fair.

They stood at the stalls all day. Between the customers and the others they grabbed a bite of food. After the fair they packed up the merchandise, prayed the afternoon service, ate some cooked food, climbed back into the wagon and dragged themselves home.

The situation of the apprentices was a hard one. They were wakened at dawn to carry water into the house, chop wood, heat the oven, carry laundry to the “strige” and attend to the children. They worked until ten or twelve at night. The night before Shabes and before holidays they worked the whole night. They knew nothing of joy, play, or doing anything for themselves.

Enslaved, controlled from their earliest youth, many ran away, not having had any opportunity even to learn to read a Jewish book or handwriting. Therefore they taught themselves to sing and more than once you could hear them singing to the beat of the shoemaker's hammer: “Little hammer, little hammer, clap, clap harder nail after nail, or “I am a little tailor, I live out the day, all day merry and gay.” One also heard the young men in the shuln singing “What is the meaning of this rainstorm, what's the story that it tells?”

The strange unfamiliar sounds carried over the town like a lovely symphony from early until late in the night. And so singing wove thoughts and feelings of longing for another life. Questions arose to penetrate minds. But knowledge was limited, the environment was without culture and we did not get any answer to the questions that bored into our heads.

The activists of 1905, the “Tsitsilistn” as they were called, Nekhe Veligure, Grintshe Mandelboym, and Gele Grinberg, came home for Peysakh and for Sukes and brought with them old Yiddish newspapers, proclamations, booklets. Meyshe Khayim Shpilman (or klezmer) opened a library and brought in booklets to read for a certain fee. Later

[Page 189]

a group of young men and women organized and created their own library. One read widely, about thoughts, feelings and questions that had lain sleeping, not answered. And when the Germans – the later barbarians – took our town in 1915 and offered a little cultural and political freedom, they were surprised to see the knowledge and understanding that the quiet, naive young men and women displayed.

They had blossomed and grown into intelligent and conscious cultural activists with comprehension of cultural, national and world problems.

Cultural clubs were created, political parties, drama circles, and as in every little town, so in ours – differences of opinion that later led to people dividing into specific political ideologies. On one side was the Poaley-tsien with Ayzik Flatner, Borukh Vinogura, Shertsman, Itshe Farbiazsh, Shleyme Hokhberg and others; on the other side was the Bund with Borukh Rozenboym, Naske Fademberg, Itshe Shpanke, Nekhe Veligure and others. They brought in speakers, discussions, one group conducted a battle with the others and together all became more intelligent through it, more conscious. Our town eventually educated poets (Ayzik Flatner), literary critics (Borukh Vinogura), writers, teachers, political activists and others.

Edited by A. Rubenshteyn, Kh. Rotshteyn

Translated by Tina Lunson

For a long time various persons had come around with ideas about creating a branch of TOZ in Sokolov. True, institutions whose task was to distribute medical help to the poor population already existed, but their activity was not coordinated and permanent, and was limited to single areas. And of course their results were not satisfactory either. Thus efforts were made by various circles to found in Sokolov an institution that could satisfy the needs of the whole Jewish population of the town, and whose task would be not only to provide help in time of need but also through daily educational work, raising the level of sanitation of the Jewish masses – an area that had been neglected for many years. It became clear that the only institution that could accomplish this was TOZ.

Unfortunately the efforts of individuals were not successful because of a lack of agreement among the wider community in Sokolov and a lack of financial resources. Only after the creation of a local central aid committee was the initiative renewed and this time with success, thanks to the first sum of money that the aid committee assigned to the goal and the good will of the TOZ Central in Warsaw.

Thus the local TOZ branch was established, which quickly won the sympathy of every level of the local population, which came to expression in the large number of people (278) who declared their membership in the institution.

Ambulatorium, Dental Clinic, School Hygiene

Looking at the great need in the town – which had grown even more during the events of the previous year and which

[Page 191]

had also called attention to the sanitation situation of the local Jewish population – the founders of the new institution decided to first open an ambulatorium under the leadership of Dr. Gradzshentshik.

Over that range of time – that is from the 20th of January until the 20th of November 1938 – the ambulatorium made 499 examinations, besides the 66 visits to the residences of the sick.

Medical examinations in the ambulatorium and in private residences by month:

Month Amb. Homes Total January 17 -- 17 February 53 3 56 March 80 20 100 April 41 14 55 May 74 15 89 June 71 7 78 July 50 7 57 August 15 -- 15 September 14 -- 14 October 34 -- 34 November 50 -- 50 Totals 499 66 565

Review of the social origins of those examined established that they came from the poorest in the town; no few of them had long harbored various illnesses which had continued to develop.

The poverty of those people made it impossible for them to be examined by a doctor; a change was introduced that set payment for a visit in the ambulatorium to a minimal 50 groshen.

A large number of those examined by the TOZ doctor also received discounted or partly-free prescriptions. (154 prescriptions were given out up to the first of June.)

The dental clinic helped 203 persons, although it must be noted that the clinic was active only until the 14th

[Page 192]

of June, and that with breaks in service because of a lack of funds.

A very large number of children from the Beys Yankev and Talmud-Torah schools were given dental fillings for free.

The dental clinic was directed by the woman Dr. R. Nelken.

All the children of the Beys Yankev and Talmud-Torah schools and the general schools were examined three to five times a month by a doctor who also took the opportunity to give them the appropriate prophylactic advice.

Light therapy, Fish oil

Thanks to the first outlay from the TOZ Central it was possible to open a light-therapy office. Over the short period of time, that is from the 7th to the 20th, 204 exposures to the quartz lamp were made.

As it was predicted that all the children of the town would need such light treatment, the cost was small and was from 10 to 30 groshen.

In the previous winter 250 bottles of fish oil were given out, of those 37 for free and 213 at discount prices.

Summer Colonies

One of the most important undertakings of TOZ was sending children to summer camps, and of course the obligation existed for the local branch while it was approaching its summer work.

Because wedid not have the relationships that were necessary to open our own camps, we joined with the TOZ branch in Vengrov. And it was decided that the Sokolov children would be taken into their camp in Yarnits.

It must be stated that the camp plan in the previous summer was one of the finest accomplishments of the local branch, although not all of the children who needed the fresh air and good nutrition had the opportunity to get it. However this was not our fault because we did not have this year's better opportunities at our disposal.

[Page 193]

Through our agency we sent five children to the camp in Otvotsk, and 64 to the summer camp in Yarnits, for whom we paid the Vengrov TOZ branch the sum of 2240 zlotych (35 zl. per child). Given the transportation fees which were 103.10 zl., the real total reached 2343.10 zl.

Against that we received:

From 17 children 10 zl. 170 zl From 16 children 20 zl 320 ” From 5 children 25 zl 125 ” From 2 children 30 zl 60 ” From 10 children 35 zl 350 ” From 5 children 38 zl 190 ” From 2 children 40 zl 80 ” No fees from 7 * children Totals: 64 children 1,295 zl The remainder of the amount, 978 zl, was covered by the TOZ fund. * For these seven children a member of the administration paid the sum of 70 zl.

To our great satisfaction the camps had a very good effect on the children, who on average added two kilos of weight, and whose health improved significantly.

Dr. Gradzshentshik visited the camp once, as did other members of the administration and uninvited guests.

Nutrition and Clothing

Nutrition for poor Jewish school children was overseen by a special section that consisted of teachers, members of the TOZ administration, and others, under the direction of Mr. Y. Nelken.

Until last year the nutrition program was led by a special committee, and with the change of directors the nutrition program at TOZ improved, and although in our case there was very little money available, the results were very satisfactory.

Last winter the nutrition program, carried out in the hall at TOZ, was very impressive.

[Page 194]

During the winter months the nutrition program served 305 children from the general schools, Beys Yankev and Talmud-Torah. That nutrition cost 860 zl a month.

A short time ago the same section distributed clothing to 115 poor children.

|

|

| The administration of TOZ in Sokolov |

Various

There were 39 meetings and reports from the TOZ administration.

127 letters were received over the time period up to the 20th of November, and 107 letters were sent. From time to time there were also communications and announcements from the TOZ administration and other publishers.

Fourteen social events were organized, from which the Khanike and Purim balls in particular brought in goodly proceeds to our branch, as did the presentation of the singer Meyshe Miadovski and two readings by Dr. Y. Kantor from Warsaw. (The small number of social events is explained by the fact that all the local presentations were organized through the rising social club and the proceeds went to the benefit of the TOZ.)

[Page 195]

|

|

| Sokolov children who received nutrition benefits |

[Page 196]

During that time our branch was visited by messengers from the Central TOZ in Warsaw: Dr. M. Shleykher (Shedlets), Y. Feld and Y. Altuski (two times).

Several took part in the national convention: In the third conference, Dr. G. Gradzshintshik; in the summer camps conference, Y. Nelkin and Sh. Rubenshteyn; in the local shuls conference, Dr. Gradzshentshik and Y. Elenberg.

TOZ also sponsored a very active reading room which was furnished with press publications from this country and from abroad.

From TOZ Bulletin 1938

Edited by A. Rubenshteyn, Kh. Rotshteyn

by Khanina Rotshteyn

Translated by Tina Lunson

Since the last Thursday before Peysakh went by without any big events, people began to believe that perhaps things would quiet down a little; just then an alarm was spread that the boycott was indicated for four weeks, that is until Peysakh, and from now on things would get better. But already on the first day of the holiday it appeared that this was no more than an illusion. It became impossible to pass through the streets in peace and not be beaten. So for example the eighty- year-old Faynershteyn met with a stone on the leg and had to take to his bed on the first day of the holiday. On the second day Malka Bekerman, Feyge Botshan and others were beaten, and on Monday night the windowpanes were knocked out at the tailor Lipe Rotshteyn's; the next day, Tuesday night, a huge stone was thrown through the window of the healer A. Vans; it also broke through the shutters and came into the house. Also all of the windowpanes were broken out of Menakhem Rozen's house.

But what played out on the last Thursday, during the interim days of Peysakh, surpassed everything else that has happened until today in Sokolov. It wasn't enough just to walk through the streets on which the attack took place and to see the mountains of glass on the ground and the broken panes, scattered boards and pillows. One had also to see the bandaged heads in order to have some small concept of the Endek-like hooliganism.

Thursday, from early in the morning, there were a lot of picketers who began to drag the Christian customers away from the Jewish shops – thereby creating this strange fact: A priest went into a Jewish shop to buy something. The picketers called him out but he did not obey them and bought the things that he needed. When he later came out onto the street the picketers ran after him calling out “Zshidovski kshondz.”

When the bands saw that they were “out of work” because the Jewish stores were already empty of customers, they began to throw stones into the shops and overturn the street stalls; the merchants were robbed and killed. But for them that was too little;

[Page 198]

a whistle was heard and they began beating any Jew they saw. Jews hurried to lock up their shops quickly and many were beaten while doing so.

The following dealers were killed and these merchants were robbed: M. Kukavke, M. Vishnievski (from Vengrov), P. Zaklikovska, B. B. Bamer, Sh. Fridman, H. Sukenik, A. Tsibulski, A. D. Goldfarb and others.

The author of these lines was surrounded by a band of hooligans under the leadership of the Endek Shventokhovski and was badly beaten.

The hooligans took off to the poorest streets – Sheroke and Vinitse – and began a pogrom. The residents resisted them, but the large number of hooligans stopped that at the onset. In these streets there was no house left with a whole windowpane. In one residence where the hooligans tried to break in the door in order to tear inside, the resident defended himself with a hatchet in hand and they retreated.

Among the leaders of the bands people spotted the well-known “hero” Stshinski, the collector for the local fire-fund Pitshke, Yan Svientokhovski and the councilman Retshke.

Altogether, on the streets Sheroke, Venitse, Pienkne, Nietsale, Olshevska, Nove and others nearly 500 windowpanes were broken out. A Christian attacked a Jewish butcher shop, snatched up the knife from the table and ran out into the street with it.

This is a list of the beaten and killed: Hershl Sukenik, his sister Blime Sukenik, Velvl Rozenboym (severely wounded, had to go to a doctor). Yankev Tshekhanovitsh, Meyshe Perlshteyn, Khanina Rotshteyn (two head wounds), Binyumin Kokhanovitsh, Motl Goldfarb, Gitl Tshekhanovitsh (badly wounded, had to go to a doctor). Rokhl Hershberg, Shimen Vierzshbitski, Feyge Hendel, Yoysef Pentsak, Meyshe Rozentsvayg, Shmuel Akive Hokhberg, Yisroel Naydorf (badly wounded, had to go to a doctor), Avrom Fridman, Shualke Radzinski, Meyshe Vishnievski (from Vengrov), Yente Himelfarb, Dovid Litevski and Yisroel Itsik Glikman.

After the events the Jewish community council sent telegrams to Premier Skadkovski and to the governor of Lublin.On Sunday an investigative committee arrived from Shedlets and two high police officers arrived from Lublin.

[Page 199]

A small but characteristic episode: A drunken corporal from Shedlets was running around the streets and harassing the Jewish passersby, when he encountered A. H. Kopovi, a member of the synagogue committee. The latter stood up to him; the corporal shouted, “If I had a revolver with me I would shoot you on the spot.” A policeman came up but the corporal quickly called up some Christian “witnesses” who all said they had heard Mr. Kopovi harassing the corporal first. The lie was not successful however and the corporal was arrested, and sent to Shedlets. But the same evening he was again seen wandering around the streets. For a meeting that took place Sunday in the meeting hall, the attorney Stipulkovski came as special guest from Warsaw (he was famous from the Pshitiker trial). The meeting drew several thousand peasants from around the entire region. The police watch was reinforced. No offensive came about.

As a result of the inquiry that the Shedlets and Lublin investigative authorities conducted, on Sunday night they went out to make arrests from among the Endekes in Sokolov and the surrounding villages. They arrested the brothers Shembovski, Bulbetovski, Tsheka, the brothers Stshinski and others.

On Monday evening when they were being taken to Shedlets, several dozen of the local Endekes gathered in front of the police wagon and gave a long-lasting ovation with the Hitler salute.

Today the Jewish residents of the village Lozov were alarmed about a frightening destruction that took place the night before in their homes. Their shutters were hacked in, the windowpanes and the upper vent windows were smashed, and the houses were full of stones. An old Jew (Polakevitsh) was badly wounded.

The previous night in the village Tribniets there was an attack on the house of the solitary Jewish resident as people threw stones and also shot into the house.

At the moment as I end this letter people tell me that windowpanes are being broken out in many houses.

The crisis because of these events is an emergency. No craftsmen can work, some of the shopkeepers are forced to close their shops, as they do not have the wherewithal to pay the rent.

A Jewish settlement is being ruined.

Khanina Rotshteyn, 1937

by Pinkhas Rafelovitsh (Tel Aviv)

Translated by Tina Lunson

The first step in establishing a dedicated national-religious institution of education in Sokolov was taken in 1918, when Yankev Grinberg – a community activist and then-president of the Mizrakhi movement in Sokolov and now Vice President of the Knesset (Israeli parliament) – founded the Kheyder Mizrakhi with the help of a group of Mizrakhi members; it was housed in the local Mizrakhi location on Nietsala Street, in Alter Bekerman's house. The teacher of the kheyder was Yitskhak Shmidman, now one of the most prominent rabonim in America.

Rov Shmidman came to and settled in Sokolov during the First World War along with a group of homeless Jews who had been driven out of the town of Pinsk and its environs. He was already a Talmud expert, gifted with pedagogical abilities and with a deep religious-nationalist consciousness, and a devoted member of Mizrakhi. Thanks to all these good qualities he was engaged as a teacher at the Mizrakhi school, and indeed he fulfilled his assignment completely, displaying much devotion and responsibility. He planted in the hearts of his young pupils a love for the people Yisroel, for the land of Israel and for the Torah of Yisroel. Many of his pupils were later among the founders of the khalutsim [pioneer] youth movement under Mizrakhi in Poland, were active general Zionists and involved in Mizrakhi work in acquiring land.

For numerous reasons the Mizrakhi kheyder closed in 1921.

With the emergence of the independent Polish Republic came the law about enforced education, which included all children from the ages of 6 to 14. The government concerned itself with finding the necessary school buildings in all the towns and villages. It was the first

[Page 201]

time that the government opened special schools for Jewish children. Those schools were called shabesuvkes because one did not study in them on Shabes, and the teaching personnel were Jewish, so that the children felt comfortable in them. After a short time however those schools were liquidated, although the program of study in them was the same in spirit as the general study programs and was taught in the Polish language. As a result of that Jewish children were forced to study in the general schools along with the Christian children. In Sokolov the school was located in a large building on Kupientiner Street, in a neighborhood where the Polish “mixed breeds” lived.

The new arrangement by the school authorities created a serious problem for the Jewish parents, who demanded an urgent solution for the following two reasons: a) Studies at the general school began at 8 AM and ended at 2 in the afternoon. The children, who spent six hours in the school, came home exhausted and could not devote themselves to religious study or go on to attend a kheyder. And b) The anti-Semitism among the Poles also infected their children, which created humiliation and misery for their Jewish school friends. Walking home after school was literally a hardship for the Jewish children who were often attacked by the Christian children with sticks and with stones. In time the Jewish children resisted them in groups and very often repaid the little gentiles for their chicaneries. Sometimes the opposite also happened, although the Christian children were always in the majority. The frequent interventions of the Jewish parents with the school director Pravetski were to little effect. He gave them to understand that despite his good will it was impossible to influence the Christian pupils so that they would not pick on their Jewish friends, and expressed his thought that his defending the zshides could have the opposite effect. By the way Pravetski was a democrat and a patriot and he was shot by the Germans in the Second World War.

In view of the situation of the Mizrakhi in Sokolov it was decided at a general gathering to establish a religious-national school that would also be honored by the authorities. In that school, which would belong to the Yavne school system under Mizrakhi in Poland, children would learn sacred studies in a broad sense and also secular subjects according to the general

[Page 202]

program of studies for schools of that type, which freed the students from attending the state schools (shkola povshechna).

The gathering elected a pedagogical council which consisted of the following members: Sender Rubinshteyn, Hershl Zaltsberg, Meyshe (Ber Leyb's) Grinberg, Yehude Hersh Skshidlover, Hertske (Itsl Milkhiker's son) Vaysberg, Mordkhe Likever, Farbiazsh, Shakhne Radzinski (Mordkhe Zalmen's son-in-law) may God avenge his blood, and separately the living Pinkhas Rafalovitsh, Leybish Shulevitsh, Avrom Bialiliev, Shmuel Kleynman. The writer of these lines was elected as a representative of the Council, and Shmuel Kleynman was designated as director of the school.

|

|

| The Yavne School in Sokolov |

The first meeting of the council took place at the home of Sender Rubinshteyn of blessed memory. At that meeting the individual members were assigned to the various functions in the preparations for opening the school: a) creating an appropriate site for the school; b) arranging for the teaching personnel; and c) securing the necessary financial means. The members on whom the task of creating the financial means lay were very hesitant to take it on and it was hard to free them from their fear of the heavy difficulty, knowing as they did that without the necessary financial means nothing God forbid would come

[Page 203]

of the great plans. The doubts were sincere and the mood was tense. Then Sender Rubinshteyn of blessed memory saved the situation.

I will never forget the moment when Sender turned to the group with heartfelt words and appealed to them not to be afraid of the difficulty since it dealt with such a sacred matter as the education of the young generation. It was not a time to have such thoughts, he said, when dealing with the fate of a generation that -was the future of our people and the basis of its existence. Sender ended his sincere words with the declaration that he was taking upon himself the personal responsibility for one half of the expenses that were necessary for the goal. His words had the desired effect, the matter was taken care of and the members set about their work energetically.

It was not easy to locate a site with three rooms for the three classes of the school because as is known in Sokolov there were not any free apartments, and especially not apartments that were appropriate for such a school. After strenuous efforts we succeeded in getting the entry hall of the large shul. The entry hall consisted of two large rooms on either side of the entry of the shul. In one of the rooms the tailors prayed on Shabes and the Lomaze Hasidim prayed in the other room. I must mention my indebtedness for the help that I received from Peysakh-Meyshe Naydorf, the gabay of the first minyen, and from Itsl Milkhiker, the previously-mentioned chief gabay in the shul. They helped to procure the rooms for the Yavne school.

In order not to reduce the livelihood of the local elementary teachers by opening the school, the pedagogical board decided to engage some of the good melamdim in town as teachers in the school. It was difficult to get a teacher who was an observer of the Torah and the mitsvos to support the set program of the Yavne schools. Since there was no suitable candidate among the Sokolovers, Shmuel Kleynman traveled to Shedlets and after great efforts he succeeded in engaging one of the best teachers in Shedlets, an old Mizrakhi member, an outstanding pedagogue with years of experience, Dovid Morgnshtern. At the same time we engaged teachers for the secular studies whose qualifications matched

[Page 204]

the requirements of the official school authorities and who were responsible to them.

The opening of the school took place after peysakh with the participation of local community leaders of various persuasions and the honorable representative from Mizrakhi and well-known leader Khayim-Shmuel Rozenboym of blessed memory. The students from all three levels had gathered in the large shul – all in their holiday clothes – beaming with pride that they could finally be done with the chicanery of the gentile boys and, to the point, that they would study sacred subjects and secular subjects in one and the same school. The many greetings from the guests and from the members of the pedagogical board were responded to by the even younger students who displayed extraordinary abilities: Yisroel-Mayer Vaysberg, Meyshe Perla may God avenge his blood and separate for a long good life Eliezer Rubinshteyn. Their appearances were received by a large audience with great enthusiasm.

In the first period after the opening of the school the pedagogical board had to trouble itself in order to be able to cover the budget and we often had to pay the teachers their earnings out of or own pockets. The only income then was the tuition fees, so the deficit grew with each month. Honoring the importance of this educational institution the administration of the Jewish community council approved a yearly subsidy for the school. Our representatives on the town council, Alter-Khayim Kapovi, Pinkhas Tshernitski and separate for a long good life Avrom Bialilev influenced the Jewish councilmen of all persuasions and procured an action to receive a subsidy from the magistrate as well. All together, after a long and difficult struggle with the antisemitic council, the Endekes, we got through a decision to designate a yearly subsidy for the school. From time to time we also received a stipend from the Yavne central at Mizrakhi in Poland. Thanks to all those stipends we could more or less cover the budget.

Every month there were examinations in all the classes, which were an intellectual experience and a satisfaction for the hard work put into the school, because they displayed the continual progress of the students in their studies. The rabonim also conducted such examinations. They stayed in town in appreciation of Mizrakhi and were delighted by the preparedness of the pupils and of

[Page 205]

their great abilities. The Hitler-sword that destroyed our town cut off the lives of those full-of-promise students. Only a few of them were saved and now live in Israel. It is my obligation to mention all the teachers who over the years educated the hundreds of students in the Sokolov Yavne school in love of the Torah and mitsvos, for the land of Israel and the Jewish people: Dovid Morgnshtern and Shloyme Yablonka from Shedlets; the brothers Meyshe and Nakhman – Zaromb; A. Platnik – Visoki-Litevsk; the writer Ayzik Ruskolenker – Kolne; Yona Bandrimer – Ostrov-Mazovietsk; the Sokolovers: Meyshe Kotlarski, Yona Posmanter, Yisroel Zinger, Akive Likhtenshteyn (Pese Khaye'tshke's son), Akive Shtern may God avenge his blood, separate for a long good life Yitskhak Shulevitsh and Khayim Veydler, the teacher for secular studies. All fulfilled their assignments with devotion and love and had a great part in the intellectual development of the fine Sokolov youth.

May their memories be for a blessing.

Yekhiel Ornshteyn (Tel Aviv)

Translated by Tina Lunson

At the beginning of the First World War, our town (like everywhere, probably) split into two groups, one favoring the Russian army and the other German. The discussion leaders of the groups were Berke Litvak and Meyshe Mendl Orenshteyn. During the day the disputes took place in Aron–Osher Zaionts' shop, and in the morning and evening in the old bes–medresh [study house]. By the way, Aron Asher's arguments were not so firey because he cleverly knew how to listen, see and be silent, so he cooled the heat of the dispute and could arbitrate and say with a smile, “These and those are the words of the living God,”– that everything is from the Master of the Universe, in any case.

Meyshe Mendl, the easy–going one, would be quiet for a while but the hot–blooded Berke could not stop for one minute: “What does that mean?” he complained. “Of course ‘the words of the living God’ but many messengers are sent from above and we must do our assignments completely.” And the dispute blazed up again, but not with as much heat. The coolness lasted until minkhe time when people came to the old bes–medresh to say a prayer to God. There, both of them wanted to draw supporters to his side. And the dispute flickered without cooling and the voices reached up to the heavens. Berke Litvak, who favored the Russians, demonstrated with signs and wonders that the great, powerful Russia with so many soldiers must be the victor: Don't you remember the Russo–Japanese War in 1904 when General Stessel (himself not a Russian) sold Port Arthur to the Japanese for ten thousand rubles, that briber, that greased paw, but in ten years the Russian Army was well developed with all kinds of weapons. And the Russian victory was good for the Jews. And Meyshe Mendl maintained exactly the opposite. That for the Germans with their higher

[Page 210]

culture and discipline, one of their soldiers equaled ten Russian soldiers. And they would bring order and cleanliness to the grimy Russian that needs nothing and has nothing, and you could convince him to make pogroms whenever he liked. Now we hear of new decrees and they are driving people from the villages and from the towns on the border. That's how a German victory would bring salvation for the Jews.

Mr. Berke Litvak was a cigarette–maker and sold them himself. His vending place was on Dluga Street near the fence opposite Yudl Bliakhar's stall, where he carried out his illegal trade in his full–packed pockets. When the war neared the River Bug and the Russians marched through Dluga Street with their heavy canon and various troops, Berke Litvak with his long, wide beard went out into the street. He stood there beaming with his boxes open and distributed cigarettes among the soldiers, saying “Please take one,” until some of the gentlemen pushed him aside and grabbed all the boxes of cigarettes, giving him a few good blows, and as an addition ripped out hunks of his beard. He gritted his teeth about his poor Jewish chin and ended with a mi she'beyrekh for escaping death.

So Berke Litvak, beaten, felt, with his broken face, as though his world had collapsed and, ashamed, he crawled into a nearby alley.

And a little later the same thing happened to Meyshe Mendl Orenshteyn, who was also disappointed in his high–cultured Germans. In the first days of the German occupation he was standing in front of his shop with apple tarts and other delicacies, when along came several German officers. They told him to weigh two trays of the apple tarts, the best kind, asked him to pack them well, and instead of paying they snorted like neighing horses shouted into his face, “You cursed, filthy Jew!” and hit him over the head with a pointed rod and disappeared.

That day Meyshe Mendl closed his shop and did not go back. As always he went to the bes–medresh but took to bed broken and sickly, feeling as though his world had collapsed.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Sokołów Podlaski, Poland

Sokołów Podlaski, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Jul 2021 by JH