[Pages 175-226]

APPENDICES

APPENDIX 1.

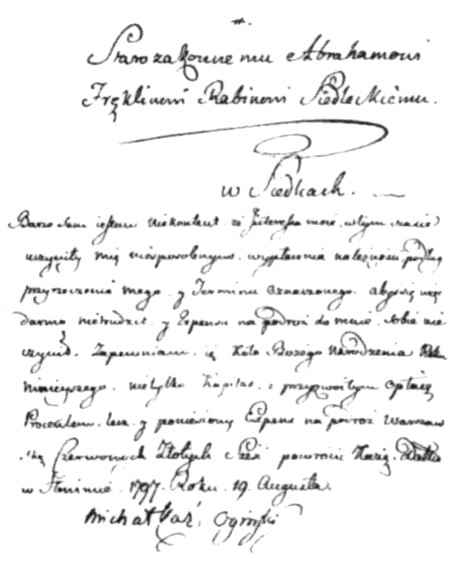

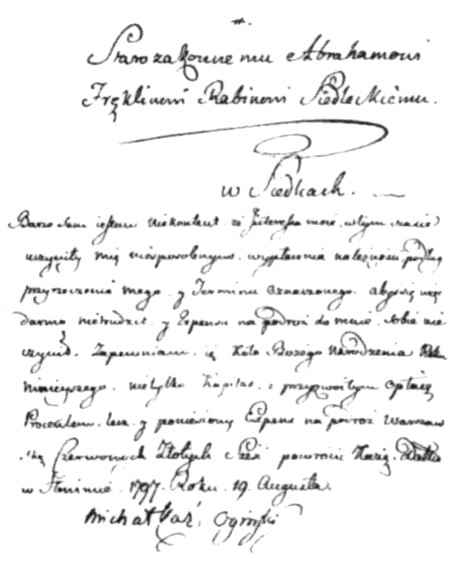

MICHAŁ KAZIMIERZ OGIŃSKI'S LETTER TO RABBI ABRAHAM FRĘKLIN FROM 1797

[The Polish text renders the contents of the letter in eighteenth century Polish, for that is the language of the original. For the sake of clarity, this translation is given in modern English.—trans.]

|

To the Orthodox Abraham Fręklin,

the Siedlce Rabbi

in Siedlce—

I am myself discontented with the fact that my interests have made it impossible for me to pay the charge according to my promise and within the indicated timeframe; therefore, do not trouble yourself in vain and do not incur the expense of traveling to me. I assure you that around Christmas of this year I will cover the cost not only of the capital, with a decent interest payment, but I will order that the expenses incurred in the Warsaw journey of six red zlotys be reimbursed.

Dated 19

August 1797 in Słonim.

Michał Kaź: Ogiński |

Source: D. Michalec, Aleksandra Ogińska I jej czasy (Siedlce, 1999), pp. 58, 156.

APPENDIX 2.

LIST OF VICTIMS OF THE 1906 POGROM IN SIEDLCE

1. Borycz Jan (Christian)

2. Bursztain Bluma, age 40

3. Cencel Stanisław, age 45

4. Diament Zalman Mosze, age 45

5. Feder Szalom Dow, age 76

6. Gersz Szyja, age 22

7. Goldberg Mordka, age 30

8. Goldstein Josef, age 30

9. Izrael Abram, age 25

10. Liberman Jakow Chaim, age 30

11. Libhaber Chana, age 52

12. Liuk Hanna, age 50

13. Lipszyc Jehuda, age 18

14. Macieliński Dow, age 25

15. Milczak Abraham, age 19

16. Miller Josef Mordechaj, age 40

17. Rafał Abraham, age 22 |

|

18. Ratyniewicz Szraga, age 32

19. Rozen Jehoszua, age 3

20. Słuszny Nachum, age 18

21. Solarz Meir, age 18

22. Solarz Sara, age 70

23. Stachowski Jehoszua, age 19

24. Stachowski—child

25. Szklarz Dow, age 30

26. Szklarz Berek, age 40

27. Szreder Szmul Berek, age 65

28. Świecący Kamień Hanna, age 18

29. Tajblum Mendel, age 34

30. Tajgenbojm Debora, age 17

31. Winberg Icchak, age 45

32. Winsztain Szajdla, age 34

33. Wolf Meir

34. Zonszein Gabriel, age 20 |

Source: Archiwum Państwowe w Siedlcach, Siedlecki Gubernialny Zarząd Żandarmerii, sig. 158, p. 28; Kaspi, ”History of the Jews in Siedlce,” in Book of Remembrance of the Siedlce Community(Buenos Aires, 1956), pp. 112–113.

APPENDIX 3.

LIST OF THE OLDEST SURNAMES OF JEWISH FAMILIES

IN SIEDLCE FROM THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

[The names are given here in the order in which they appear in the Polish original.—trans.]

Anyż, Altan, Ajzenberg, Aronowicz, Arman, Ajzakowicz, Ajzensztadt, Angelczyk, Akierman, Agresbaum, Amsterdamski,

Baran, Blumsztejm, Berenbaum, Bobek, Blady, Białyłew, Białepole, Bromberg, Brukarz, Brzezina, Białytist, Białobroda, Biały, Bursztyn, Bachrach, Brener, Bronstejn, Boruchowicz, Borensztejn,

Cukiersztejn, Cynamon, Cynowagóra, Celnikier, Cybula, Cerenfeld, Cybulski, Cymbalista, Cymerman, Celnik, Cik, Całkowicz, Cukier, Cukierfeld, Cygielsztejn, Cwangman, Ciszyński, Ciemny, Cacko,

Drewno, Drewniany, Drzewo, Dudaszek, Dobreserce, Dua, Dozorca, Dąb, Dąbrowa, Damski, Dawidowicz, Dajen, Delman, Dolina, Dobryrybak, Dobrowolny, Dobrzyński, Dobrezłoto, Drogikamień, Dystelman, Dziewulski,

Eplewicz, Epelbaum, Edelman, Edelsztejn, Edelbaum, Elfant, Erlich, Esseryk, Elman,

Farbiarz, Fajnholc, Fejganbaum, Fajnsztadt, Fajer, Fajn, Fajwełowicz, Feldman, Felszer, Federman, Frydman, Figowy, Finkelsztejn, Firsztenberg, Fiszman, Fisz, Forman, Fogelfeld, Frajman, Frymerman, Frydrych,

Gałąska, Garncarz, Gaik, Grający, Garbarz, Grynberg, Galicki, Gertner, Głowina, Goldshmidt, Goldman, Goldwirt, Goldsztejn, Goldfeder, Gildblat, Goldfarb, Groch, Grzywacz, Gryner, Grynszpan, Gruszka, Grzebieniarz, Gurfinkiel, Guterman, Gutgold, Gurszmidt,

Handlarz, Herszkowicz, Himelszajn, Husyd, Herszenzon,

Izraelski, Ickowicz, Iserowicz,

Jubiler, Judkowic, Jungerman, Jabłko, Jabłonka, Jabłoń, Jasnagwiazda, Jasnagóra, Jadowski, Jakóbowski, Janklowicz, Jawerbaum, Jerzmowski, Jedwab, Jadło,

Kapłan, Kawe, Karsz, Kamienny, Kapura, Kamiński, Kanarek, Kant, Kafowicz, Kahan, Kania, Kadysz, Kamień, Kawecki, Kapelusznik, Kenigsberg, Kelmanowicz, Kejzman, Kopytowski, Korona, Konewka, Koński, Konopny, Kowal, Kozienicki, Kon, Kogen, Kotuński, Kamar, Kornicki,

Laska, Las, Laufman, Laksfisz, Lewin, Lew, Lewit, Lejbowicz, Lewita, Lebengilk, Liwerant, Lis, Linka, Lipiec, Lipecki, Lichtenberg, Libfrajd, Litmanowicz, Lipszyc, Lubelczyk, Lubelski, Leśniczy, Lonka,

Łęczycki, Ławnicki, Łazowski, Łosicki, Łagowski, Ławecki,

Markusfeld, Makobodski, Mendelson, Mocny, Mrożnicki, Miedziany, Minc, Matysowicz, Mandelbaum, Międzyrzecki, Mąciarz, Młynarz, Murawa, Malin, Moszkowicz, Mandelcwajg, Makówka, Mydlarz, Milgrom, Mączny, Miler, Masło, Marchewka, Mróz, Mosiążnik, Mordski, Miły, Morgenstejn, Majorowicz, Mordowicz, Morgensztern, Mak, Miska, Manna,

Nejman, Niski, Nerkowagóra, Niebieskikamień, Nadworny, Nusbaum, Nauczyciel, Niwka, Niebieskafarba, Nisenholc, Niebieski, Nutkowiec, Nuchymowicz, Niemieckafarba, Norman, Nelkenbaum, Nowack, Niewczyński, Nusynowicz,

Ogórek, Orzeł, Orzechowicz, Ogrodnik, Ospały, Osiński, Orensztejn, Opolski, Ogórkowedrzewo, Orzech, Osina,

Rynecki, Rubinsztejn, Rafał, Rubinkowy, Różowagóra, Rak, Rozenbaum, Ryba, Rybak, Rowek, Rychter, Rajzman, Rozenberg, Różowykwiat, Rydel, Rakowski, Rozenwaser, Robak, Rzetelny, Rozenblit, Rodzącedrzewo, Rogowykamień, Ryza, Rozengarten, Rogowicz, Rossenberg, Rozenfeld, Rozen,

Stołowy, Skórnik, Srebrnykamień, Światły, Silny, Srebrnykąt, Świecącykamień, Srebrnagóra, Suchożebrski, Szklarz, Sokołowski, Sukiennik, Sercha, Segal, Sarisztejn, Srebrnik, Smoła, Słuszny, Salamander, Senderowicz, Skórzecki, Sobol, Szafir, Solarz, Sektor, Szielman, Szmulowicz, Szenkman, Szmuklarz, Szumacher, Szwarc, Szczupak, Szczecina,

Tabak, Tenenbaum, Tabakman, Tykocki, Tejblum, Tejtelblum, Tejwes, Tęcza, Topor, Trzmielina, Towjowicz, Turban, Tajer, Twardagóra,

Ubogi, Uczony, Uberman, Ujrzanowski, Urman, Uczeń, Urwicz, Unger, Urch, Uterhaus,

Wilk, Wysoki, Wyrobnik, Wodnykamień, Wynograd, Wajnsztejn, Wrona, Węgrowski, Wyszkowski, Waksman, Wiernik, Wróbel, Wólfowicz, Wesoły, Włodawski, Woskowy, Wielki, Wolnicki, Winogron, Wajnszelbaum,

Zielonofarba, Złotykamień, Zając, Zonszejn, Złotowaga, Zylbersztejn, Zuck, Zysmanowicz, Zysman, Złotagóra, Zielechowski, Żelaznagóra, Zręczny, Żelazny, Zbuczyński, Żebrak, Zalcman, Zylberman, Zanwelew[i]cz, Złotabroda, Zys, Zylberberg, Zylberfuden, Zebrowicz, Zynger.

Source: Shedletser Wochenblat, no. 19 (1937).

Translator's Note: Among the surnames in this list, there are those that are quite Polish sounding: “Jerzmowski,” “Ciszyński,” “Dziewulski,” “Niewczyński,” “Kawecki,” “Sokołowski,” “Dobrowolny,” and so on. Some clearly have a Jewish reference, many with the “-owicz” suffix that means “son of”: “Ickowicz,” “Izraelski,” “Lewin,” “Dawidowicz,” “Matysowicz,” “Kahan,” “Manna,” “Aronowicz,” “Janklowicz,” and others. Some are adjectives: “Zręczny” [skillful], “Konopny” [hempen], “Blady” [pale], “Drewniany” [wooden], “Ciemny” [dark], “Kamienny” [stone], “Niski” [short], “Uczony” [learned], “Niebieski” [blue], and so forth. Others name professions: “Celnik” [customs official], “Farbiarz” [dyer], “Jubiler” [jeweler], “Kapłan” [priest], “Kapelusznik” [hatter], “Ogrodnik” [gardener], “Handlarz” [merchant], “Nauczyciel” [teacher], and so forth. Still others are the names of fruits, animals, birds, or objects: “Baran” [sheep], “Cacko” [bauble], “Drewno” [wood], “Gałązka” [branch], “Konewka” [watering can], “Lis” [fox], “Smoła” [tar], “Masło” [butter], “Ogórek” [cucumber], “Korona” [crown], “Szczupak” [pike], “Gruszka” [pear], “Wilk” [wolf], “Zając” [hare], “Rak” [crayfish], “Tęcza” [rainbow], “Marchewka” [carrot], and others. Many are compounds: “Białylew” [white lion], “Cynowagóra” [tin mountain], “Jasnagwiazda” [bright star], “Niebieskikamień” [blue stone], “Ogórkowedrzewo” [cucumber tree (!)], “Srebrnykąt” [silver corner], “Złotabroda” [gold beard], “Rodzącedrzewo” [fertile tree], and others. Some of these compounds are clearly direct translations from German (such as “Białepole” = Weissfeld = white field), and some even have both a translated form and a Polonized spelling of the German surname: the German Eisenberg is both Żelaznagóra and Ajzenberg, the German Gutgold is both Dobrezłoto and Gutgold, the German Goldstein is both Złotykamień and Goldsztejn, Rozenberg is both Różowagóra and Rozenberg, and so forth. There are even combinations of Polish and German spellings: “Cukierfeld” = Polish “cukier” [sugar, although phonetically similar to the German Zucker] and German “feld” [field]. The diversity in these surnames gives a vivid picture of the nature of the Jewish community, its background, its professions and trades, its appearance, and in many cases its distinctiveness from or similarity to the surrounding Polish community.

APPENDIX 4.

LIST OF DROSHKY DRIVERS IN THE CITY OF SIEDLCE AS OF 19 OCTOBER 1919

1. Lew Lejbko

2. Pięknedrzewo Moszko

3. Lew Moszko

4. Liberman Berko

5. Kopyść Karol

6. Bursztyn Aron

7. Lew Szapsia

8. Staręga Antoni

9. Szmielina Jankiel

10. Bibersztejn Bjuma |

|

11. Bursztyn Szaja

12. Lewin Gecel

13. Jerzymanowski Icko Abram

14. Sikorski Franciszek

15. Gruszka Herszko

16. Dębowicz Szlama

17. Federman Abram

18. Staręga Jan

19. Bursztyn Moszko

20. Bursztyn Lejbko |

Source: Archiwum Państwowe w Siedlcach, Komenda Powiatowej Policji Państwowej w Siedlcach, sig. 116.

Out of 20 droshky drivers, 16 were Jews. They mostly drove their own vehicles. The surname Szmielina appears in other records as Trzmielina. Worthy of attention is the Polonized entry of the surname Pięknedrzewo [beautiful tree—trans.] and also the entry Dębowicz Szlama—a Polish-sounding surname and a Jewish first name.

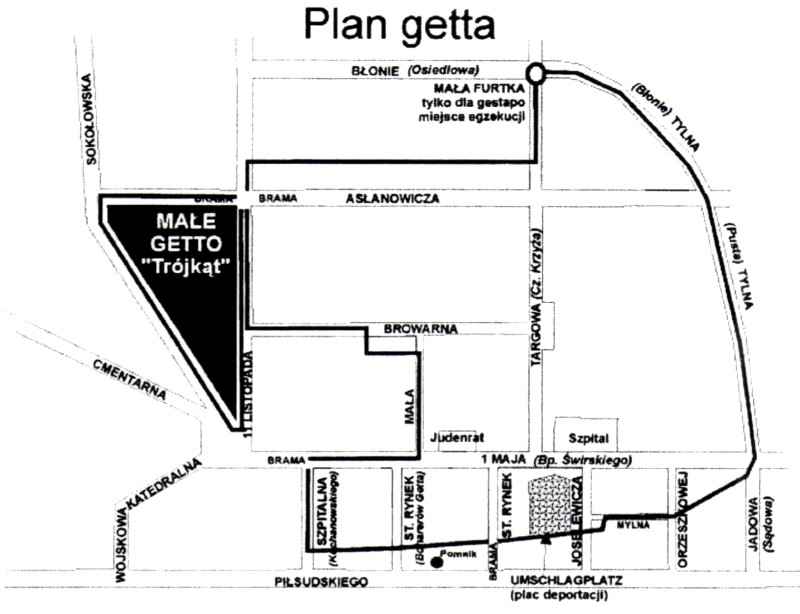

APPENDIX 5.

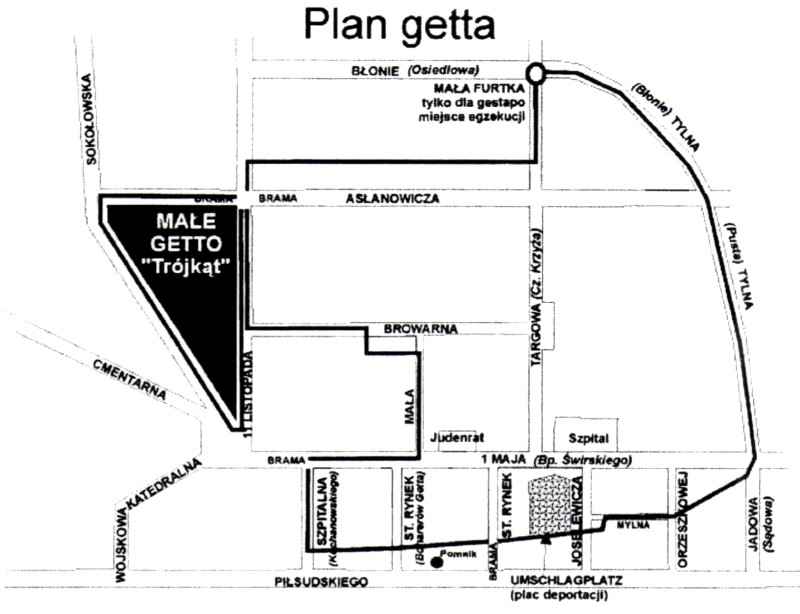

MAP OF THE GHETTO IN SIEDLCE

[The meanings of street names, when not names of people, are given in brackets. Current street names are given in parentheses and italics. Designations that are not street names are given in translation only.—trans.]

- Map of Ghetto

- SOKOŁOWSKA [Sokołów] Street

- BŁONIE [Commons] (Osiedlowa [Housing Development] Street)

- SMALL WICKET, only for Gestapo, place of executions

- TYLNA [Back] Street (Commons)

- GATE

- GATE

- ASłANOWICZ Street

- SMALL GHETTO “Triangle”

- BROWARNA [Brewery] Street

- TARGOWA [Market] Street (Czerwonego Krzyża [Red Cross] Street)

- TYLNA [Back] Street (Pusta [Empty] Street)

- CMENTARNA [Cemetery] Street

- NOVEMBER 11th Street

- MAŁA [Small] Street

- JUDENRAT

- HOSPITAL

- KATEDRALNA [Cathedral] Street

- GATE

- SZPITALNA [Hospital] Street (Kochanowski Street)

- STARY RYNEK [Old Square] (Bohaterów Getta [Heroes of the Ghetto]Street)

- MAY 1st Street (Bishop Świrski Street)

- STARY RYNEK [Old Square]

- JOSELEWICZ Street

- MYLNA [Mistaken] Street

- ORZESZKOWA Street

- JADOWA [Venomous] Street (Sądowa [Court] Street)

- WOJSKOWA [Military] Street

- PIŁSUDSKI Street

- MONUMENT

- GATE

- UMSCHLAGPLATZ (square for deportations)

|

Source: Determinations of the author on the basis of material from Beit Lohamei Hagetaot in Israel.

APPENDIX 6.

TEACHERS OF JEWISH NATIONALITY CONNECTED WITH SIEDLCE

WHO WERE MURDERED OR MISSING DURING WORLD WAR II

- Altman Efroim, teacher at Primary School No. 1 in Siedlce, shot to death in Siedlce ghetto.

- Barg Rachela, teacher at Primary School No. 7 in Siedlce, murdered in Siedlce ghetto.

- Felsenstein Sara, teacher in Łosice, missing in Siedlce ghetto.

- Kafebaum Ita, teacher in Mordy, killed.

- Landau Estera [Rosa], teacher at Primary School No. 7 in Siedlce, murdered in Siedlce ghetto [one the 29 women executed at the cemetery—ed.].

- Neugoldberg Lija, teacher at Primary School No. 5 in Siedlce, murdered in Siedlce ghetto.

- Reichner-Wasserman Estera, teacher at Królowa Jadwiga Secondary and Preparatory High School in Siedlce, died in unknown circumstances.

- Rotbaum Abraham, teacher at B. Prus Secondary and Preparatory High School in Siedlce, died in 1943 in Warsaw ghetto.

- Skorecka-Parnasowa Rojza, teacher in Mordy, murdered in Siedlce ghetto.

- Szaferman Moszek, teacher at Primary School No. 7 in Siedlce, murdered in Siedlce ghetto.

- Szwarc Estera, teacher at Primary School No. 6 in Siedlce, died in Siedlce ghetto.

- Wassercug Abraham, teacher at Primary School No. 6 in Siedlce, murdered in Siedlce ghetto.

Source: Działalność Tajnej Organizacji Nauczycielskiej na terenie obecnego woj. Siedleckiego w latach 1939–1944 (Siedlce, 1992), p. 175. [The plaque in memory of Siedlce teachers who perished during WWII includes many of these names; see http://www.siedlce-zwiedzanie.pl/pomnik012.htm.—ed.]

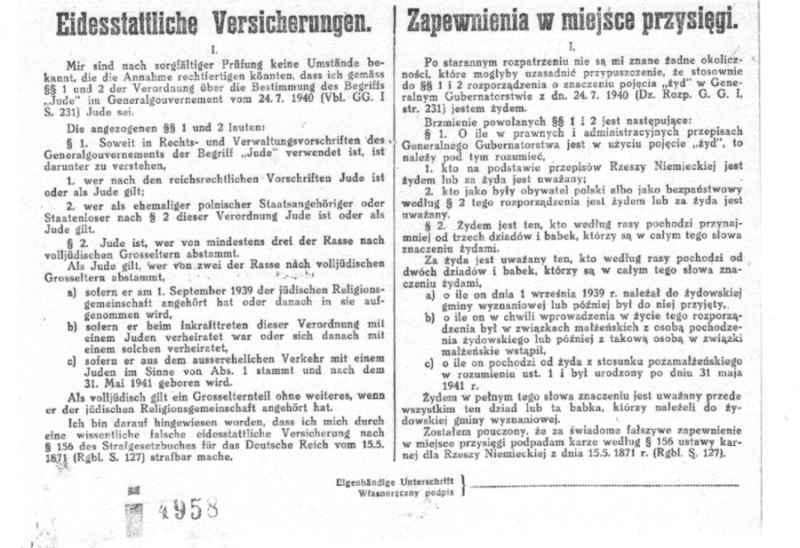

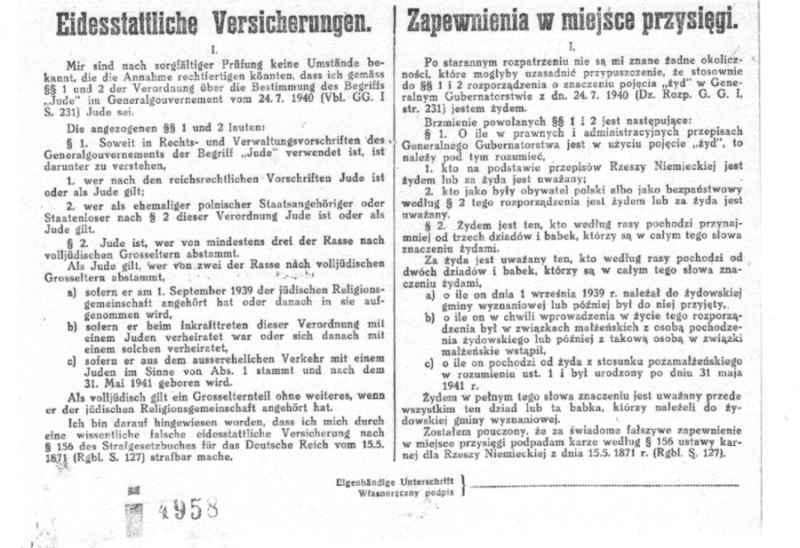

APPENDIX 7.

ASSURANCE IN PLACE OF AN OATH

Document from the time of World War II that one is not a Jew. Whom the German occupiers considered a Jew is clearly stated in the text.

Translation

Assurance in Place of an Oath.

I.

|

After careful examination, I know of no circumstances that would justify the assumption that I am a Jew in accordance with §§ 1 and 2 of the decree on the meaning of the concept “Jew” in the General Government dated 24.7.1940 (Depart. of Decr. of the G. G. I, p. 231).

The content of referenced §§ 1 and 2 is as follows:

§ 1. To the extent that the concept “Jew” is in use in the legal and administrative regulations of the General Government, this should be understood as,

- who is a Jew or is considered a Jew on the basis of the regulations of the German Reich;

2. who as a former Polish citizen or as a stateless person according to § 2 of this regulation is a Jew or is considered a Jew;

§ 2. A Jew is a person who by race is descended from at least three grandfathers and grandmothers who, in the full meaning of this word, are Jews.

A person is considered a Jew who, according to race, is descended from two grandfathers and grandmothers who, in the full meaning of this word, are Jews,

- if he belonged to a Jewish religious community on 1 September 1939 or was later accepted into it,

b. if, from the moment this regulation went into effect, he was joined in marriage to a person of Jewish descent or later became joined in marriage to such a person,

c. if he is descended from a Jew due to an extramarital affair as understood by excerpt 1. and was born after 31 May 1941.

A Jew in the full meaning of this word is considered to be that grandfather or grandmother who belonged to a Jewish religious community.

I have been informed that I am subject to punishment according to § 156 of the criminal statute for the German Reich dated 15.5.1871 (Rgbl. S. 127) for giving a false assurance in place of an oath.

Eigenhändige Unterschrift ______________________________________

Handwritten signature _________________________________________ |

Source: From the author's collection.

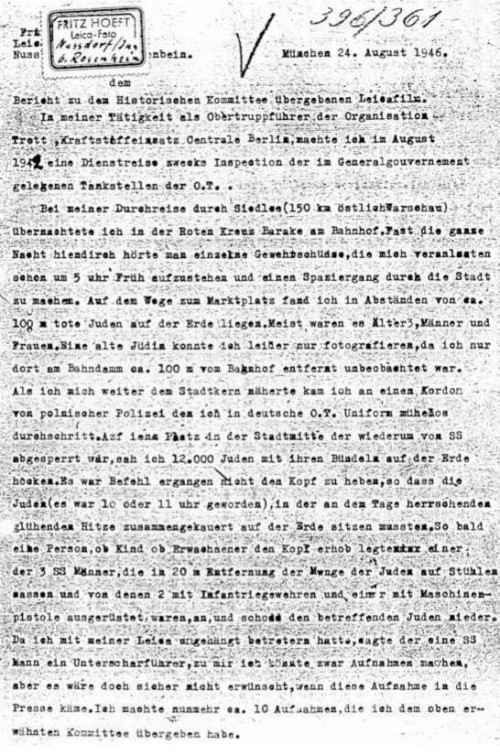

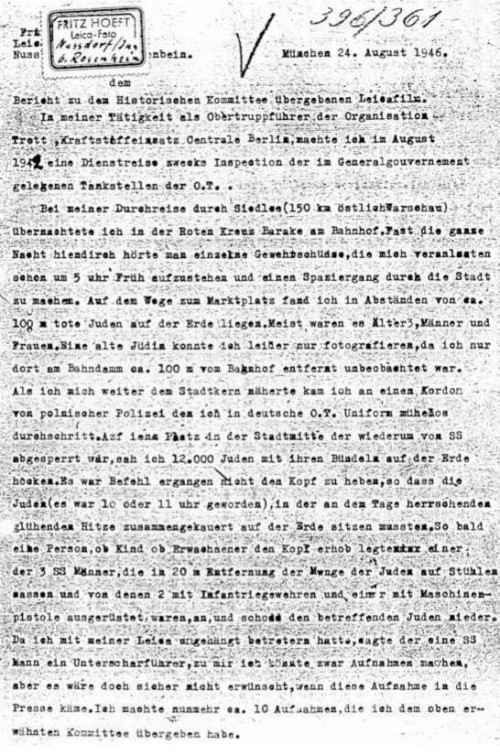

APPENDIX 8.

FRITZ HOEFT'S INFORMATION ON THE SUBJECT OF TAKING

PHOTOGRAPHS DURING THE LIQUIDATION OF THE GHETTO

Source: Yad Vashem archive in Israel.

Translation

Munich, 24 August 1946

Fritz Hoeft

Leica Photo

Nussdorf/Inn

k. Rosenheim

(company stamp)

Information concerning the Leica film handed over to the Historical Committee

In my work as a higher commander of the Trott Organization [reference is to the Todt Organization1—author's note], the Center for the Use of Fuels in Berlin, I was on a business trip in the General Government in August 1942 in order to inspect the gasoline stations located there.

While traveling through Siedlce (150 kilometers east of Warsaw), I put up in the barracks of the Red Cross at the railroad station. Almost all night one could hear individual gun shots, which forced me to rise at 5 in the morning and take a walk through the city. On my way to the market square, I saw dead Jews lying about 100 meters apart. Most often these were elderly men and women. I could photograph only one elderly Jewish woman because I could be undetected on the embankment at a distance of about 100 meters from the station. When I approached the center of the city, I walked past a cordon of Polish police, because, being in the uniform of the German Trott Organization, I could move about without a problem. The square in the center of the city was surrounded by the SS, and I saw 12,000 Jews there who had squatted on the ground with their bundles. A command was given that they may not raise their heads, so they had to sit hunched on the ground in the terrible heat of that day (it was already 10 or 11). If some person, no matter whether a child or an adult, raised his head, then one of the SS men, who were sitting in chairs 20 meters away from the crowd and were armed, two with infantry weapons and one with a machine gun, would shoot at the Jew. Since I had my Leica camera hung over my shoulder, one of the SS men, he could have been a non-commissioned officer, told me that I could take pictures, but that it would not be desirable for them to find their way into the press. I took about 10 pictures, which I handed over to the above-mentioned committee. When after several hours I was walking past the freight station, I saw Jews on one street next to the station as they waited to be loaded. The SS men were running along the rows armed with whips, and they were randomly beating the Jews standing in the heat. I also have several pictures from that spot.

A few days earlier, during my inspection of fuel depots in [the town of] Ujazd next to Tomaszów, I visited the ghetto there. There I even saw a Berlin family of Jews I knew, who were living there in primitive conditions. I also handed over to the committee a few pictures of the Jewish police, starving people, and abandoned children, as well as the process of delousing.

I testify under oath that everything corresponds to the truth and that I have added nothing.

Fritz Hoeft

Nussdorf/Inn

(—) signature |

APPENDIX 9.

INTERVIEW WITH HUBERT PFOCH

Hubert Pfoch, geboren 1920, war während des Krieges Soldat und danach Funktionär der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Österreichs. Nach dem Krieg engagierte er sich sehr für den Wiederaufbau Wiens; zeitweilig war er Präsident des Wiener Landtages.

Herr Pfoch, als junger Soldat der Wehrmacht haben Sie einmal einen Deportationszug gesehen. Was haben Sie da beobachtet?

Ja, ich bin damals mit hundert anderen Soldaten von Wien an die Front nach Rußland abkommandiert worden. Und am 22. und 23. August 1942 bin ich in Siedlce oder Sielce in Polen einem Transport begegnet und habe mit angesehen, wie die deutsche Polizei, SS, aber wie sich später herausgestellt hat, ukrainische Hilfswillige…

In SS-Uniform?

In SS-Uniform… in ganz grausamer Weise Hunderte Juden, die zuerst auf einem Perron saßen, in die Waggons hineingeprügelt haben, mit Schlagen und Stoßen, mit Schießen und Schreien.

Haben Sie auch einen Mordfall erlebt?

Ja. Zuerst habe ich noch probiert, unseren Zugkommandanten zu einer Intervention zu überreden – unter dem Vorwand, wir seien deutsche Soldaten, sogenannte Front, und unsere Kampfmoral würde ja nicht gerade gestärkt, wenn man Zeuge solcher Grausamkeiten würde. Ein SS-Offizier, es war aber ein Deutscher oder ein Österreicher mit einem Wolfshund, hat uns beteuert, wir sollten schauen, daß wir wegkommen, sonst ließe er einen Waggon anhängen und wir könnten uns Treblinka von innen anschauen.

Sie haben doch den Mord an einer Mutter und einem Kind gesehen.

Ja, ich habe mit anschauen müssen, wie ein ukrainischer Hilfswilliger eine junge Frau mit Kind, die sich zu Boden geworfen hat, so gerichtet hat, daß der Kopf des Kindes auf dem Kopf der Mutter lag, und mit einem Schuß beide tötete.

Und er hat gelacht dabei…

Ich habe dann versucht, das zu dokumentieren. Und ich habe ja im Krieg immer auch ein Tagebuch geführt. Das besitze ich noch. Ich habe mir vom Waggon meinen Fotoapparat geholt und habe unter großer Gefahr vier Aufnahmen von diesen Szenen gemacht.

Ich habe sie auch damals dem Staatsanwalt im Prozeß gegen die Lagermannschaft von Treblinka zur Verfügung gestellt, und sie sind 1965 mit als Material, als Zeugenmaterial, verwendet worden.

(Abb. 1) Das ist der Perron des Bahnhofes von Sielce [Siedlce], und hier sind Angehörige von jüdischen Hilfstruppen, die schon mehrmals in diesen Autos gekommen sind, um die Toten abzutransportieren, die in der Nacht von ukrainischen Hilfswilligen erschossen wurden. Sooft einer aufgestanden ist, hat er auf die Gruppe geschossen, und es hat eine große Zahl von Toten gegeben oder Erschöpften, die von diesen Leuten wie Mehlsäcke auf das Auto geworfen worden sind. Bei der Verladeszene habe ich dann dieses Bild fotografiert (Abb. 2), nachdem die Soldaten, die mit mir unterwegs nach Rußland waren, zu dem Transport hingegangen sind. Dort lagen die, die nicht schnell genug gelaufen und von der SS erschossen worden sind. Hier sieht man zwei dieser Toten. Der eine Mann hat einen Gehirnaustritt gehabt und über den ist der Waggon drübergefahren und hat ihm die Hand abgedrückt. Und dann gibt es noch diese schreckliche Szene (Abb. 3), wo die Gruppen für den Transport in den Waggon hineingeprügelt werden, und zwar auch so, daß die Familien zerrissen wurden. Der Vater in einem Waggon, Mutter und Kind woanders, und man sieht ja die Ärmlichkeit dieser Leute, die angeblich aus dem Warschauer Ghetto gekommen sind und nach Treblinka in dieses Vernichtungslager gebracht worden sind, wie ich spater erfahren habe. (Abb. 4) Dieser Soldat, ein Ukrainerder, der dann diese Mordszene mit Frau und Kind gemacht hat – und andere haben mit ihren Gewehrkolben so reingeschlagen, daß die Kolben gebrochen sind und sie nur mehr den Lauf mit dem Schloß in der Hand gehabt haben. Rechts im Bild sieht man noch einige Deutsche, die das mit anschauen, aber natürlich nichts dagegen tun konnten. Ich habe das alles notiert, also zum Zeitpunkt des Geschehens.

Mir war schrecklich übel. Aus dem Lager in Trehlinka, wo wir vorbeigefahren sind, ist ein penetranter Leichengeruch in der Luft gewesen, und ich habe mich bei der ersten Station hingesetzt, und das alles, was ich gesehen habe, aufgeschrieben und dokumentiert, wie ich auch sonst immer wahrend der Kriegsgeschehen liier Eintragungen gemacht habe – wo wir uns aurhalten, wer verwundet, wer gefallen ist. Und ich habe auch politische Kommentare in das Tagebuch mit entsprechender Vorsicht aufgenommen.

Source: Michel Alexandre, Der Judenmord. Deutsche und Österreicher berichten [(Cologne, 1998)], pp. 33–36.

Translation [from the Polish—trans.]

Hubert Pfoch, born in 1920, was a soldier during the war and then an activist of the Social-Democratic Party of Austria. After the war he was very involved in the rebuilding of Vienna; for a time he was also the chairman of the Viennese Landtag [Parliament].

Mr. Pfoch, as a young soldier of the Wehrmacht you saw the deportation train. What exactly did you see?

Yes, at that time I was sent from Vienna to the eastern front. From 22 to 23 August 1942 I encountered in the town of Siedlce or Sielce in Poland a transport and I saw the German police, the SS, or, as it later turned out, Ukrainian helpers . . .

In SS uniforms?

In SS uniforms . . . drive hundreds of Jews, who had been sitting on the platform, into freight cars in a very brutal way, with beating, shooting, and shouting.

Did you witness the killing?

Yes, first I still tried to convince the commander of the transport to intervene. I used the pretext that we are German front-line soldiers, and morale would not be strengthened by being witnesses to such cruelty. The SS officer, he was either a German or an Austrian with a German Shepherd dog, assured us that if we refused to be witnesses to the killing, he would order another car to be attached to the transport, and we would be able to have a view of Treblinka from the inside.

Did you see the killing of a mother and child?

I had to watch as a Ukrainian helper picked up a young woman and child, who had earlier thrown themselves onto the ground, and stood them up in such a way that the child's head was resting on its mother head, and he killed them both with one shot.

And he was laughing . . .

I tried to document all of this. And during the war I also kept a diary, which I still have. I also pulled my camera out of the train car and, being in great danger, took four pictures of those events.

I was also as the disposition of the prosecutor during the trial against the staff of the camp in Treblinka in 1965. My pictures were used as evidentiary material. This is the platform of the train station in the town of Sieice [sic], and here are the members of the Jewish auxiliary units, who often came in these cars to take away the bodies of those who had been shot to death during the night by the Ukrainian helpers. As soon as one of the reclining people rose, the Ukrainians would shoot at the whole group. There were a lot of dead and exhausted people, who were thrown onto trucks like sacks of flour. I photographed a loading scene [see photograph 125—author's note] while the soldiers who were with me going to Russia were walking toward the [military] transport. Lying on the ground were those who couldn't run fast enough and so were shot to death by the SS. Here we see two of those who were killed. You can see the brains leaking out of one of them; moreover, a passing train cut off his hand [see photograph 124—author's note]. Then there is this terrible scene [see photograph 122—author's note] in which we see a group of people being driven into a freight car in such a way that families were separated. The father into one car and the mother and child into another; and we can also see the misery of these people, who were supposedly from the Warsaw ghetto and were taken to the death camp in Treblinka, as I later found out. This soldier [see photograph 123—author's note], a Ukrainian, who was the perpetrator of the killing of the mother and child, and others were hitting so hard with the butts of their rifles that these would crack. On the right we can see several Germans, who see this but of course can do nothing. I noted all this as it happened.

I felt terribly ill. An intense stench of bodies was being exuded from the camp in Treblinka, past which we were riding. I sat down at the first station and wrote down what I had seen. I took quite thorough notes from the time of the war—where we stopped, who was injured, who died. I also wrote down political commentary in my diary, with appropriate caution.

:

APPENDIX 10.

THE ACCOUNT OF SISTER OF THE SACRED HEART BENEDYKTA

(APOLONIA KRET) WRITTEN DOWN BY PIOTR KOMAR

(SKÓRZEC, 02.06.2008)

In looking through the convent chronicle with Sister Benedykta, I found an entry dedicated to Barbara Piechotka. It related that it was a commander of the navy-blue police that asked the Sisters of the Sacred Heart to take into their care one of two girls he found in the woods. The older one was taken by a local farmer's wife to work, while the younger one was to be taken care of by the sisters. As we can conclude from the entry in the chronicle, the girl was about 4 years old, was sick, and was terribly neglected.

Yet Sister Benedykta asserts that it happened differently. In spite of her advanced age (90 years old), she remembers those times fairly well. It was 1944. According to the sister, one of the nuns once went to the local, Skórzec, township offices in order to take care of some clerical matters; as far as she remembers, it was December and there was snow on the ground [an error either in the month or the year, since in December 1944 the Red Army was already in this area—author's note]. While she was in the township offices, a farmer burst in and started to shout that he had been left an orphan who was louse ridden, neglected, and on top of that sick. When she returned to the convent, the sister immediately told this whole incident to the mother superior, who ordered the farmer to be found immediately and the child to be taken from him and brought without delay to the convent. It was painful to look at the child; it had lice everywhere. The sisters cleaned her up and dressed her in new clothes because the others were only worth burning. As the sister says, she swept the lice from her cut hair with a broom since they were scampering away from the flames that were coming out of the oven. Then the sisters rubbed the girl with an ointment for over a dozen days until all the lice were gone.

She was a very nice child who loved to sing love songs and who was in fact about 4 when she was found. During the first stage of her upbringing, no one, not even the mother superior, knew that she was Jewish. Taking into account that at that time, if it had come out, it would have meant death.

Sister Stanisława, along with the local priest, prepared her and her older sister, Jadzia, for First Holy Communion. The sister let the girls know that in order to take First Holy Communion they have to be christened. To which both in unison answered that they were Catholics and both had been christened in Warsaw. It was after the fact that Sister Stanisława went to Warsaw to check if they were indeed telling the truth, and that's when it all came out. These people didn't exist; they had themselves adopted the name Górska, and they had made up the whole story of the christening. They claimed that that's what their parents had taught them. They also said there had been three of them, but they didn't know the fate of their sister; they didn't know who had taken her. They also admitted to the worst for those times: that they were Jewish. Their parents and brother had died during the escape from the Warsaw ghetto. The girls had escaped from the ghetto and walked as far as Czerniejew, from which an unknown man had driven them in his wagon to Skórzec.

Sister Stanisława thought through the whole situation and decided to christen the girls. First she went to the local priest, who along with her had been preparing the girls for First Holy Communion. The priest, outraged by the whole thing, yelled at her that he would not christen the girls. No one at the convent knew about the whole matter yet. After this, the sister, under the pretext that she was taking them to the doctor—claiming that one of the girls has a polyps in her nose—rode with the girls on horseback to the Kotuń priest, who christened them. Considering the times then, he did not write up a certificate of christening for the girls, undoubtedly in fear of punishment, even by death.

Only after the fact did the convent sisters find out about the true ancestry of the girls. This did not, however, change their attitude toward them. They continued their upbringing. The girls were accompanied to and from school, since there was a fear that the Jews would kidnap the girls. After a time, the Jews indeed came for the girls in a horse-drawn droshky, as Sister Benedykta recalls. They said that, through kindness or by force, they would still take the girls. They wanted to pay the mother superior for taking care of them, but she pushed the money aside, stating that it was not for this that she had raised the girls. The year was 1946, but the sister was not entirely sure.

After the girls had been taken, the mother superior could not rest, since she had heard rumors of trade in children. Only when Basia sent a letter from Zabrze that she calmed down and sighed with relief. She wrote in it that all her things were taken when she was leaving for Israel.

Until this day, Basia keeps in touch with the convent, not only by mail but also visiting the convent in person. She visited the convent for the last time in 2002, as the entry of 12.09.2002 in the chronicle testifies. She at that time came to Poland with an attorney, who went with her even to Kotuń in order to find her certificate of christening. However, there was none, since as I already mentioned above, the priest had not issued one out of fear for his own life. She did not hide her disappointment over this fact, since, as she said, a Polish citizenship was important to her, for reasons not further clarified.

Basia more than once invited the sisters to Tel Aviv, where she now lives. Some of them accepted her invitation, and she, of course, covered all the travel costs. She sent packages and Christmas cards. As Sister Benedykta recalls, she even sent 50 dollars several times. The point was not about the money itself, the sister states emotionally, but about the very fact of remembering. Sister Benedykta was awarded a medal. As she says with a smile, “Smashing those lice was worth it.”

Basia's fate after being taken from Skórzec varied. She finished her studies, was a Hebrew language teacher, got married, and changed her real name, Faktor, to Piechotka. Then she was divorced; as she stated, she was too delicate for her husband. Now she is retired. She even wrote several books about her time in Poland. She wrote about her story, representing the Poles in “too rosy a light,” which was the reason the books were not accepted for publication.a She considers the years spent in Skórzec as the happiest in her life.

At this point it is worth mentioning that the headquarters of the Gestapo, where people were tortured and many died, was also located in the convent of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart. The sisters also helped many orphans from the Zamość region.

Editor's Note, Appendix 10

- It is difficult to say with any certainty why Basia's books were not published. Return

APPENDIX 11.

AGNIESZKA BUDNA “JADZIA”

She was born in 1909 or 1916 in Aleksandrów Kujawski, in a Catholic family. She lived in Gdynia until the war. After the occupation of the city by the Germans, she was displaced as a Pole. She spent several weeks in a transition camp in Częstochowa. Then, at the end of September 1939, she ended up in Siedlce via Warsaw with Helena Górska and her two children. The German Labor Office referred her to the Siedlce Criminal Police Department, Kripo, as a cleaning lady. At that time, the department was headed by an officer named Zulauf. The station was still being set up at the time, and the painting and carpentry work was being done by Jewish workers. Budna became acquainted with and befriended them. When the first liquidation of the ghetto took place, that is, 22–24 August 1942, the Germans still left Jewish labor detachments behind. When they started preparations for complete liquidation, Budna, in October 1942, hid six people: Motl Galicki; Lipa Galicki, Motl's teenaged brother, whom she brought from the camp on the so-called Bauzug train; the Halber brothers, Izaak, who escaped from a labor detachment at the airport, and Abraham, employed as a mechanic at Kripo; Melech, who escaped from a transport to Treblinka; and Dawid Grünberg. Budna took up residence with the fugitives in a modest two-room apartment in the garret at 43 May 1st Street (currently Bishop I. Świrski Steet; the building from that time has been partially rebuilt). The apartment contained an alcove used as a storeroom for coal, wood, and potatoes. This space had a double wall, behind which the fugitives could hide when necessary. There was very little space there, and they only went there in the event of a threat; otherwise they spent the whole time in the room. While “Jadzia” was at work, there had to be absolute silence in the room. Love developed between Budna and Motl Galicki. Motl always impatiently awaited “Jadzia's” return, and opened the door for her. A neighbor noticed this, and pointing at “Jadzia” in the market square accused her of hiding a Jew. Budna reacted decisively with a denial. She called her a vicious gossip, explaining that this was not a Jew but her man. In order to remove suspicion from herself, she invited Commander Zulauf and several policemen for dinner the next day. A roast goose and some alcohol created the right atmosphere. The Germans were loud, which all the neighbors noticed. That removed suspicion form “Jadzia,” who bought three rabbits and kept them in the storeroom. Any knocking sounds in the apartment during the tenant's absence could be explained in this way.

And so all lived to see the arrival of the Red Army, after which Agnieszka Budna and Motl Galicki were officially married. In September 1945 they had a daughter whom they named Bela. They left for Munich with her husband's family. They soon returned, however. Motl died in January 1946, and Agnieszka returned to Gdynia. Then she worked in a hat cooperative in Legnica. Here she met Szymon Widerschal, whom she married. Unfortunately, her daughter, Bela, fell under a train and died. This was a horrible event for the mother, who blamed other children for the accident. She left for Israel in 1958 with her husband, and in 1987, at the application of Izaak Halber, she was awarded the title of Righteous among the Nations of the World. Her photograph along with an interview appeared in the prestigious album Rescuers: Portraits of Moral Courage in the Holocaust by Gay Block and Malka Drucker. She died in Israel in 2004.

Source: Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Testimony of Agnieszka Widerschal, sig. 2222/119–/ (03.2555); W. Stefanoff, “Jedna na milion,” in Gazeta Stołeczna, 30.10–01.11.1993; from the recollections of Izaak Halber and his letter to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem dated 10 March 1986, in the author's possession.

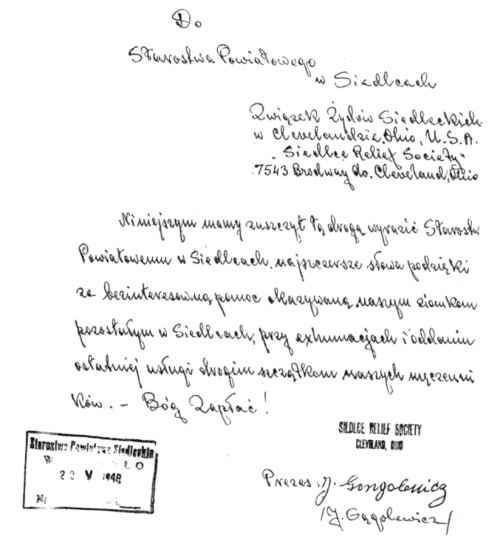

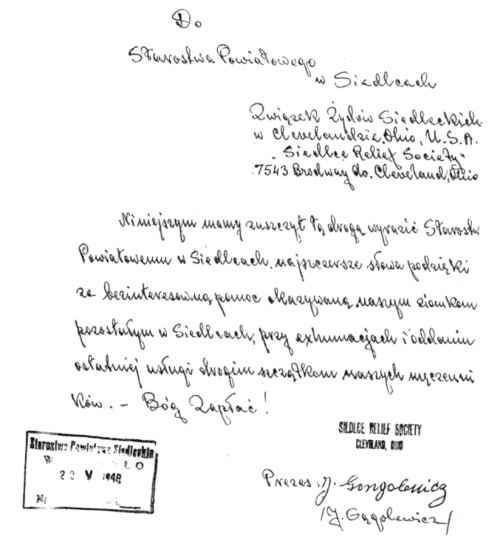

APPENDIX 12.

LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE UNION OF SIEDLCE JEWS

IN THE UNITED STATES TO THE COUNTY ADMINISTRATOR IN SIEDLCE

WITH THANKS FOR HELP DURING THE EXHUMATION OF JEWS

MURDERED BY THE GERMANS DURING WORLD WAR II

Translation

To the County Offices in Siedlce

Union of Siedlce Jews in Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Siedlce Relief Society

7543 Broadway Ave., Cleveland, Ohio |

| We hereby have the honor of expressing our sincerest thanks to the County Offices in Siedlce for the disinterested help offered to our compatriots remaining in Siedlce during the exhumation and provisions of last rites to the dear remains of our martyrs.—God bless you! |

[STAMP]Siedlce Relief Society

Cleveland, Ohio |

[STAMP]Siedlce County Offices

In [ILLEGIBLE]

22 V 1948

No. [ILLEGIBLE] |

[HANDWRITTEN] Chairman J. Gongolewicz

[HANDWRITTEN]/J. Gągolewicz/ |

Source: Archiwum Państwowe w Siedlcach.

APPENDIX 13.

STATEMENT CONCERNING THE POLICY OF LOCAL AUTHORITIES

REGARDING THE PROTECTION OF LANDMARKS AND RESPECT

FOR PLACES OF NATIONAL REMEMBRANCE IN SIEDLCE

Reprehensible events have taken place in Siedlce in recent years regarding the protection of landmarks and places of national remembrance. They have shaken public opinion. They consist of the following:

—the demolition of nineteenth-century buildings and wooden houses in the center of the city;

—the removal of the landmark memorializing the historical place of execution of Poles during World War II as well as the stone and tablet in honor of the Home Army on Piłsudski Street;

—the demolition of the Jewish prayer house on Asłanowicz Street;

—the demolition of the Jewish hospital on Armia Krajowa Street;

—the destruction of the historic nature of Duchess Aleksandra Ogińska's seventeenth-century park;

—the destruction of the historic nature of several Siedlce streets.

In 1995, an opinion titled “Siedlce. A Study in Cultural Significance” was commissioned by the Siedlce City Offices in the matter of preparing detailed plans for the spatial development of Siedlce. On several hundred pages, the authors describe the urban value of historic buildings and present concrete recommendations about putting them under conservation protection. In spite of the opinion of specialists, many buildings and places important for the history of Siedlce are disappearing from the panorama of the city. Local authorities are ignoring the recommendations of experts.

The most disturbing recent example of the destruction of buildings important to the cultural space of the city and arousing protests among sympathizers of Siedlce is this year's demolition of the building of the old Jewish Hospital on Armia Krajowa Street. This building had an over 130-year-long history and was one of the few Jewish structures that survived the Second World War. In the professional literature it was noted as a landmark and as a unique building. It also existed as a landmark in the consciousness of Siedlce natives. As a religious hospital, it was exceptional on a national scale. It was probably the only surviving Jewish hospital in Poland. The property of the hospital was bordered by the old Jewish cemetery, destroyed only during World War II. According to some sources, it also included the hospital property.

In 1906, the hospital was one of the main places in which the tsarist pogrom of the Jews took place. It went down in history as the “great Siedlce pogrom.” People were murdered in the shelled building, in which the wounded were hospitalized. Many were killed on their way to the hospital. The Russian extermination of the Siedlce Jews was reported on in the largest newspapers in Europe and the United States: Time, Die Welt, Arar, Berliner Tageblat, Der Neuer Weg, Forwerts, and many others. The pogrom outraged the opinion of the whole world. Half of the population of Siedlce before the war was of the Jewish faith, and 17,000 Jews were murdered in the city's ghetto during the Nazi occupation. Now the last reminders of them are being liquidated.

Those who have an interest in the history of Siedlce as well as in the development in Poland of research on the history of local societies are outraged by the liquidation of reminders and proof of the 400-year-long presence of Jews in Podlasie. A federative understanding of culture, one of the fundamental characteristics of which is openness, requires us to take care of the history of our society in its multinational dimension. Father J. Bocheński, a Polish-Swiss philosopher, once said about this openness, “The idea of a homogeneous state [. . .] is in direct opposition to the ideology of classical Poland. In Poland, everyone had a place.”

The liquidation of the building of the Jewish Hospital is also the destruction of the legacy of Polish culture, an open and multifaceted culture. Jewish culture is not something that is isolated from and indifferent to our culture but is its historical element that derives from the tolerance that is rooted in our history. Those signed below express their surprise at the transfer to a private investor of the building, reclaimed by the Jewish Council in the 1990s, that was the last of the places of martyrdom of the Jewish nation from the times of the tsarist holocaust preserved in Siedlce.

In light of the above-mentioned facts, those who love Siedlce are expressing their disapprobation of the policy of the local authorities concerning the preservation of landmarks as well as respect for places of martyrdom of the Polish nation leading to a loss of the architectural and historical identity of the city. They are expressing their indignation at the institution responsible for the preservation of the Polish cultural tradition. They are proposing that immediate steps be taken to protect all structures that are unique in Siedlce architecture from liquidation and well as the initiation of procedures for the bestowal of the legal status of landmarks of art to buildings that are important for the architectural tradition and history of Siedlce. They are also proposing that particular protection be given to places of national remembrance. These places are designated by history for all time.

[Following are the signatures of 246 residents of Siedlce—author's note.]

Source: Text of the “Statement” in the author's possession.

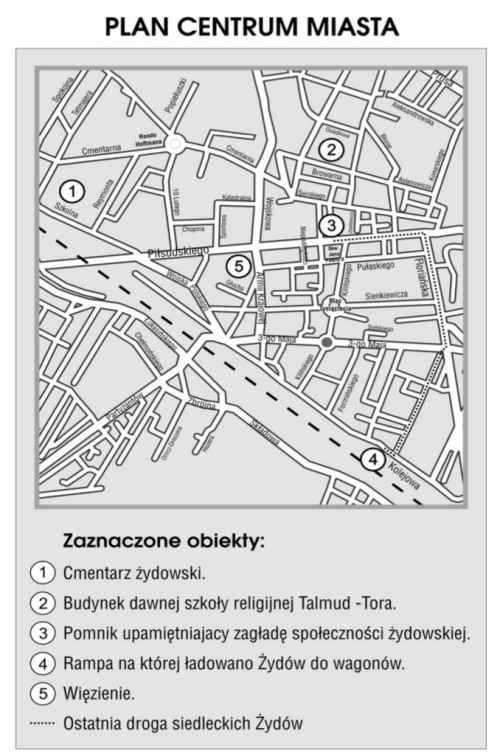

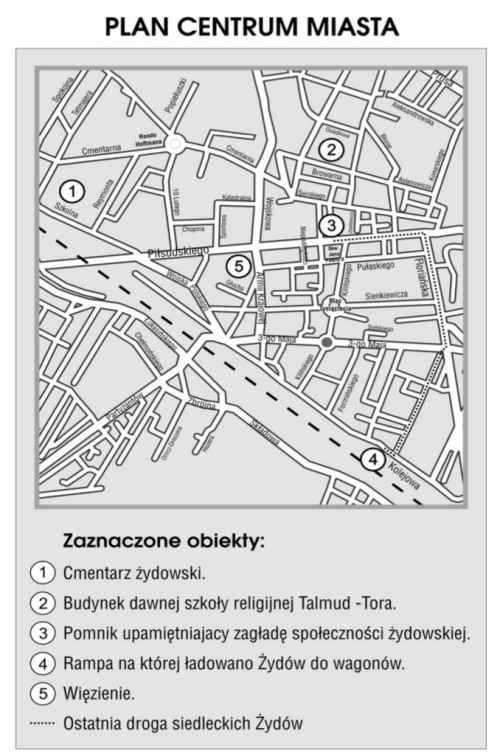

APPENDIX 14.

MAP OF THE CENTER OF THE CITY

| Marked sites:

- Jewish cemetery.

- Building of the former Talmud-Torah religious school.

- Monument memorializing the extermination of the Jewish community.

- Ramp by which Jews were loaded onto freight cars.

- Prison.

—— — — — — The final road of Siedlce Jews

|

Source: Drawn by the author.

APPENDIX 15.

ANNE SAFRAN—“WANDERING AROUND SIEDLCE”

I wander around Siedlce seeking a face I may know.

Here's Jatkowa Street, there Długa . . . But no, you I don't recall!

My grandfather's house destroyed, the deep well boarded up . . .

How everything has been washed away by bloody, cruel years!

In the city park I hear weeping trees.

The stream by the hillside—why's it bubbling so noisily now?

Where are my friends, those who were cheerful and fair?

I feel their shades surrounding me . . .

Siedlce, 1962. |

Source: Fragment from the collection Will to Live (New York, 1968). Translated from Yiddish into Polish by Michael Halber.

APPENDIX 16.

STORIES BY BRACHA KAHAN (BEATRICE STOLOVY)

The Jewish stories written in Yiddish by Bracha Kahan (Stolovy) were translated for the first time into Polish by Maria Halber and edited by Edward Kopówka in consultation with Michael Halber.

Bracha Kahan was born in Siedlce in 1899. Her father, Abraham Hersz Kahan, was a butcher, the co-owner of a butcher shop. Her mother, Rojza née Osina, was occupied with raising five children: Bracha, Chana (Anna), Chaim Lejb, Aaron, and Sara. The family lived at 8 Jatkowa Street.

Bracha's formal education was limited to three grades of the Russian public school, which was free. Her parents were financially unable to provide further education for their daughter, although her mother had ambitions to give her children an education. Bracha received private lessons in Polish and Yiddish. In 1915–1916, she took part in the classes of the drama section of the Yiddishe Kunst club (the so-called Hazomir) and attended classes in Hebrew. She immigrated to America in 1916 with her sister Anna, who was two years younger than she.

After arriving in the United States, Bracha worked hard in New York confectionary workshops, studying the English language at night. Some of the money she earned she sent back to Siedlce to her family, whose financial circumstances were dire. In 1920, her parents and the rest of her siblings immigrated to America. In that same year, Bracha married Izaak Stołowy, who had emigrated from Siedlce to Chicago a few years previously. Two children were born of this union: Alexander and Edith, who later took the name Semiatin.

Bracha Stołowy published poems in the Jewish press in the United States (Der Tog and Forverts). She also published three books in Yiddish: Mayn velt (My world), 1952; Verter un verlekh fun yidishn folklor (Proverbs and sayings from Jewish folklore), 1976; and Fun fargengene teg ( From bygone days), 1978. This last publication contains mostly poems and recollections. Bracha Stołowy died in 1983.

1. “The Wench”

Long, long ago, in my Polish city of Siedlce, where I was born and raised, one often saw people who were not in their right minds running around the streets. At that time these people were not placed in institutions, as they are now. They walked around freely, as long as they did no one any harm. I have not forgotten those characters, which have engraved themselves in my memory, even though I came here as a young girl.2 The demented paupers wandering about the streets were sick, ragged, and hungry. No one took an interest in them. Only the children noticed them, ran after them, taunted them, and teased them. We all know how cruel children can be in relation to handicapped people if the proper attitude toward them is not explained to them. One of these unfortunate figures was “The Wench.” That's what they called her. No one knew her real name. It was said in the city that she had come from afar and from a pious family. She went mad because her parents forced her to marry someone they had sought out themselves and did not allow her to marry her beloved, who was a tailor. Every spring “The Wench” would appear on the streets of the city. She was a tall, slim woman with beautiful eyes. She walked around clad in a black shawl. In her arms she carried a child wrapped in rags. She talked to herself, constantly rocked the child, comforted it, and kissed it constantly. And so she wandered about with the child for days and weeks. And then one day, a terrible scream was heard throughout the city: “Where is my child!” she called in a terrible voice. “Help! Give me back my child!”

No one even looked at her. No one was interested in the woman's fate. Just as before, when she was walking around with the child. Everyone was indifferent to her screams. Only the rascals ran after her and mimicked her.

“You want a child? Here!” they yelled and pelted her with stones and rag balls.3

In the city they said that “The Wench” lived in the ruins outside town in the winter. She was kept by irresponsible youths,4 who took advantage of her in exchange for food. No one in the city wanted to look after her. Everyone said, “Let someone else take care of her.”

And so it was repeated from year to year. Until the following spring. With its arrival, “The Wench” would again appear on the streets with a newborn child wrapped in rags in her arms.

2. “Candies, Chocolates, Jellies”

When I recall the shops in the old days in Siedlce, A. Liessin's peom “Der Kramer” (The shopkeeper)5 immediately comes to mind. In it, the poet so authentically described that life, that hunger, that cold, and those meager earnings. He showed how a poor shopkeeper, waiting hopelessly for a customer to whom he could sell a herring for two kopecks, would become engrossed in the meantime in musings about the Holy Land and the Messiah. This poem reminds me of the story of a little stall belonging to my relative in Siedlce. Her husband was a room painter and a good craftsman. He painted the walls for rich customers, and his favorite theme was beautiful green meadows, trees, and even birds. In spite of his honest labor, he could not earn enough for bread and rent. His wife, our relative, decided to open a stall. She borrowed a few rubles and made a special box with compartments according to her own concept. She put into it candies, chocolates, jellies, and other goodies. She also bought a few seltzer siphons, and she displayed all this, along with a few colorful glasses, in one of the windows of her apartment, which was located facing the street. And so she became a merchant! One day passed, then another, a third, and no one came to make a purchase. The saleswoman was forced to leave her stall to buy some potatoes and kasha herself.

“And what if a customer comes and I'm not here?” she thought. And she had a brilliant idea: “I'll engage my six-year-old sister, who is being raised in my home.”

As she thought, so she did.

“Esther,” she called. “I'm going shopping, and you pay attention to the children and the stall. I'll show you how to open this box if a customer should come. Remember, you must take a kopeck for each piece, a two-kopeck coin for two pieces, and don't forget to close the box right away and put it back in the window.

“Yes,” Esther nodded her pretty little head.

My relative obviously forgot that you don't send the cat for milk. Little Esther could not resist opening the box. At first she only wanted to have a look at all these delicious treats. But she could not resist, took a candy into her hand, and carefully bit off a piece from one side. She also took a chocolate and delicately nibbled on it. She placed the nibbled-on sweets back into the box in such a way that no one would notice. Then my relative came back home, checked that the box was closed, and calmly started to prepare dinner. Little Esther watched the stall every time my relative had to leave the house. And she always nibbled on a piece of the goody. This lasted until a customer came and bought a few candies. When my relative counted out the candies, she noticed a misfortune. All the sweets had been nibbled on at one side. I can imagine what a scolding little Esther got. I well remember the frightened eyes of the six-year-old “big girl” when our relative brought her to my mother for judgment.

“I don't want to see her in my house anymore,” she said. “She has brought misfortune to me. If she had taken a few chocolates, I could understand. But she nibbled off a piece of all the sweets. How can I sell them now?”

My mother gave Esther a proper talking to and my relative a few guldens, and the trial ended there . . .

3. “Great-Grandmother Matl”

My maternal great-grandmother lived to be almost 100. She outlived all her children. I have remembered her as a slim, tall, straight-backed woman dressed in a black silk dress. She wore a bonnet6 on her head that matched her dress and was decorated with silk flowers and velvet bows. She never wore glasses, although her vision was poor in the last years of her life. She often visited her daughter Rojza, my mother, who was brought up in her home until her wedding.7 Grandma Matl, as we all called her, was perfect in everything: dressing, cooking, as well as running a home, which was a rarity in those times, that is, in 1910. She never ate roasted or cooked food prepared by another's hands. She cooked and baked herself until the last days of her life. She did not trust another's hands.8 I remember her cleanly maintained apartment, a living room and kitchen. I was then 9 years old,9 and Mother would send me to her to invite her for the holidays. I would run the two streets to her house, cheerful and glad, for I knew that Grandma would treat me to home-baked cookies.

To this day I remember the impression her little apartment had on me. The first thing that struck you after entering the room was her bed, which shone with cleanliness and whiteness. It was covered by a hand-made bedspread. Two big, down pillows lay on it in embroidered white pillowcases. The table was also set with an embroidered tablecloth. There was always a carafe of wine and challah in the room as well as silver candlesticks with candles ready to light when Shabbat came.

Grandma offered me her cookies, as usual, waited until I ate them, then, elegantly dressed, followed me to our house.

Once my mother sent me to Grandma's to bring her to a Siedlce photographer. She very much wanted to have her picture. I knew that very pious Jews did not allow themselves to be photographed because they considered this a sin: “Man,” they would say, “was created in the image of God.”10

I walked and wondered if Grandma would allow herself to be photographed. When I arrived, I politely asked, “Grandma Matl, do you want to be photographed?”

“Why not?” she answered. “Let all my children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren have my photograph. When they look at my picture, then they will not forget me.”

Mother was already waiting for us at the photographer's studio to bring Grandma Matl inside. Grandma hesitated a moment: “Wait, Rojzele,” she said. “I think my collar is not even. One corner is longer, and the other is shorter,” Grandma said.

“It's even, it's even, everything is fine,” Mother answered.

And the photographer took Grandma's picture.

When I now look at Grandma's picture, I see with surprise that, indeed, one corner of her collar is shorter than the other.

Written May 1977.

[Editor's Note: The photograph described in this story is reproduced as Photograph 52A in the photographs section.]

4. “Skheda”

I spent my childhood years in the skheda.11 That's what my mother and father would call our apartment, which our grandfather, rest his soul, left to his children as an inheritance. This was a small wooden house with four tiny apartments and three little stalls. The seven siblings split this among them after our grandfather's death. Some got apartments, others stalls. When I got older and was 6,12 the skheda got too tight for us because of the arrival of several siblings. These three cramped little rooms became filled with additional beds, little beds, and cradles. My father decided to move to a larger apartment and to rent our part of the skheda. He calculated that, although it will be hard for him to pay rent, at least the family would not suffer by living in such a cramped space.

“We will live like human beings,” he said. “When I get the rent for the skheda, I'll add a few rubles, and we'll manage somehow.”

This idea was a good one, but anxiety crept in at the very beginning. The man who had rented the apartment, a cheder teacher, a poor beggar, did not have the money for the rent in the very first quarter. In those times, rent was paid quarterly, that is, for three months. The tenant came to my father, made excuses, and asked my father to wait a little.

”As soon as I get the tuition money from a few tenement-house owners whose sons I teach, I'll immediately bring it with thanks,” he said.

But he didn't have it to pay in the second quarter either, and he didn't even come to make excuses. My mother started to nag my father, claiming that this so-called teacher would bring us grief. She had hoped that the rent from this apartment would buy new shoes for the children since they were walking around in shoes with torn soles. But my father justified the tenant. “But he's a pauper. As soon as he gets the money, he'll bring it to us. Don't worry, he's a decent Jew. Trust me.”

And that was the first time we children heard our parents arguing. We marveled. What could have happened?

“What is he thinking!” my mother yelled and started to cry. “We have to get the apartment back. My children are dearer to me than this tenant. Let the rich Jews in the city support him. Go to him again and tell him you need the apartment back for yourself and he should just move out.”

My father came to the conclusion that my mother was right, and with a heavy heart he went to his tenant. This was before Sukkot. Cold winds were already blowing, and a light rain was falling. Mother sat and waited for the money that my father was supposed to bring. The thought out loud, “Bruchele needs a new coat because she has started going to school. Chana should get a new dress because she's grown out of the old one. The boys need new shoes and yarmulkes for when they go to the synagogue.”

My father returned. He didn't say anything. He took the Talmud book13 and immersed himself in contemplation. My mother tried to talk to him a few times, but my father didn't listen to her at all and just “mumbled” verses. At a certain point, my mother lost her patience. “You went to take care of something,” she said loudly. “Tell me what you accomplished,” she added.

My father kept rocking back and forth over the book,14 as though he were looking for help there and started talking as if to himself. “He is a pauper, and he's supporting a bunch of hungry children. He even wanted to give me a few rubles,” said my father and became thoughtful for a moment.

“And you gave them back to him?” my mother cut in angrily.

“How could I take them from him after I found out that he had borrowed these few rubles from Szymon to pay back his loan in the grocery store? They wouldn't give him anything more on credit. You should see those hungry children, how they threw themselves at the bread and herring he had brought home! Oh, well,” my father said with tears in his eyes, “I didn't want those children on my conscience. I did not want them to die because of me.”

My mother was moved by what my father had said, and tears glistened in her eyes as well. They didn't talk about this anymore. In the meantime, winter came with its gales and freezes. There was not much joy in our house either. We spent our last saved rubles for the rent. There was no income; there was nothing to buy coal with to heat the apartment. My father and mother walked around the house in their winter coats, and we children lay in our beds covered with our featherbeds and kept warm that way. Suddenly the door opened. The wind blew, and it became even colder in the room. The melamed came in,15 stooped and embarrassed. After looking around the apartment and seeing our situation, he took off his coat and said, “Take this, Mr. Hersz, this is my entire fortune. This is a good fur; my father-in-law gave it to me as a wedding gift. This is what I have left from better times. What can I do when I have nothing to pay with? I am a melamed; many students have left me lately, and new ones aren't coming. You know what? Throw me out into the street with everything I have. Maybe someone will take pity and take me under their roof. I know you are not rich. So what am I to do? My wife even tried her hand at peddling, but instead of making money she put money into the business! It didn't work out. One could just tear oneself to pieces! Take my fur, please,” and he shoved the coat into my father's hands. My father shuddered. “What are you doing, Mr. Dawid. For God's sake. In such freezing weather, how can I let a person out without a coat? Put it on, this second!

He walked the teacher to the door, and said in parting, “Be well, and may God help you!”

5. “A Jewish Home”16

Rajzla sits in a rocking chair, lost in thought and memories. Her whole life swims before her eyes, ever since her Michał went into eternity. She lives in her dreams and memories of the past. She had an intense life. She sees herself in a small town in Poland, where she was born in a very religious home, and she recalls the festive holiday celebration, the table beautifully set by her mother, the Shabbat candles, and she hears her father's prayers. All this has stuck forever in her memory. Then she thinks of daily life in her country [the United States—author's note], she is tormented by loneliness and abandonment, a longing for those close to her. Her face shines as she remembers Michał's proposing to her, but she was still too young, he was older and experienced. They decide to wait until her parents arrive here [the United States—author's note]. The beautiful days have passed. Love, theaters, concerts, operas—she visited them all. Dear children. Much joy. Her husband, Michał, also came from an Orthodox home. But he had long since walked away from that atmosphere. Travel in distant countries and eating in other people's houses moved him away from religion. He was an avid Zionist, and he loved his nation. He worked socially, but he wasn't religious. Religion, he would say, is an impediment in normal life.

What Michał said had an enormous influence on Rajzla. She was very young and slowly succumbed to Michał's influence. After the wedding, everything was kosher in her house at first, but Michał laughed at her. All these rules17 had arisen in bygone, primitive times, even though they were invented by wise people. There were no sanitary conditions in those times. Jews were taught then to wash their hands before eating, to go to the mikveh, to use certain dishes18 according to religion. All that was fine once, but now what do we need these superstitions for when we have hot water and soap? Well, understandably the rabbi didn't agree with him, but Rajzla nodded and worked out her own principles. For example, she bought meat at a kosher store, but she didn't soak and salt it.19 She didn't mix meat and butter, and pork never appeared in the house. Michał also compromised. He pleased his wife, and he also respected her parents. He did not go to the bethel on Shabbat, but he came on holidays. He also went with Rajzla on Yom Kippur after the service to meet her parents by the synagogue to wish them a happy new year. The whole family gathered for the meal on Passover, and sometimes on Saturday evenings or on other holidays. That was the whole of his Jewishness.

Time flew, and children were born. Heated times ensued; Rajzla didn't complain but became active. She worked in Jewish organizations, studied, took classes, and read a lot of books. Often after hard work she would fall asleep with the children out of great fatigue. But she did not give up, thanks to Michał, who never refused to look after the children even though he got up very early for work. They spent Sundays all together. They took the children for a walk in the park; sometimes they went visiting, and sometimes they invited guests to their house. Rajzla grew spiritually and exceeded Michał. She was active in organizations, sent the children to school and to declamatory classes. She herself studied a lot. Bitter years came, unemployment, crisis. Michał lost his job. It seemed that dollars had been saved. You had to eat, and there wasn't even money for the rent. Winter came, shoes needed to be bought for the children, and a doctor needed to be paid for. Michał would become despondent, anxious. But Rajzla kept comforting him. She repaired and remade old things. She borrowed here and there, and life improved again. Through the whole time her house was the most cultured in the whole neighborhood. Time did not stand still. Michał has not been among the living for a long time. He suddenly got a heart attack, and Rajzla had to manage on her own. The children left home, and then she missed Michał all the more. But by the end of the week the house would revive anew with laughter and conversations with the children, who came to visit their mother. The children often brought their guests, Jewish and Polish friends. The young people fell in love, and many of them married; that is when Rajzla noticed the mixed marriages among her children's friends. She became frightened. Her national feeling was revived. What will happen to my children now? This was during the time of Hitler. Her heart bled at what the Germans did to her nation. She saw and felt the indifference of non-Jews, their silence. A Jewish misfortune in a Christian world. She only then realized that she should have brought her children up differently. She wanted to consult Michał, she walked around shaken, and her lips murmured, “Rabunu shel el.”20 She asked God for these children not to walk away from her nation. Her prayer was answered. Was it coincidence that her children married Jews and keep Jewish homes?

6. “Family”21

Around the year 1912, maybe 1913, my father became a subcontractor. He would supply the Russian garrison with food, mainly flour, sugar, fish, meat, and other products. I remember that my father would arrange the fish, ready to eat, in packages. They were seasoned with various seasonings and fried in oil. I still remember the taste of that fish, they were crispy and dry. My father once brought some fish home, because a barrel had broken open during transport and he could no longer sell them. But the main merchandise that my father provided was meat. In those times, one would buy cows directly from farmers and take them to the slaughterhouse. Those huge slaughterhouses in which meat was bought by the pood [a Russian measure of weight equivalent to about 35 pounds—trans.] did not exist yet. A Jewish butcher22 had to buy a cow for his use at a butcher shop or buy kosher meat from my father. That's why my father would have his cows slaughtered at a Jewish slaughterhouse, at a ritual slaughterer's, and asked God that the meat was kosher.23 For only then, when the meat was kosher, could my father exchange it with Jewish butchers. That's when he made money, when the butchers paid more for every kilogram of kosher meat, and my father would use the nonkosher meat for the army. The whole impoverished family benefited from the fact that the meat was kosher. In those days, a dish with a piece of meat was a rarity on the table. When my father happened on several pieces that were deemed kosher, he would bring all the offal home in a sack. The lungs, liver, intestines, heart, feet, and suet were all additional profit for my father. Doing something with them was a task that belonged to my mother, who placed many treasures on the table. She prepared bigger and smaller packages out of them right away.

“Bruchele, take this big package to Chana's. Her poor children will be glad,” she would say, seemingly to herself. “And take this package across the street to Chaja's, she also has a room full of little children. A now you, Chaim, take this package to Leja's, and there's a package for you, Aronek, too. Run across and put this into Rachela's own hands.”

We would already be on our way when we would hear our mother's voice, “And don't dawdle, children, but come right back! I still have packages to be delivered!”

And so my mother sent everyone out until the sack was empty. To this day I remember the children's joy when I would appear on their threshold. I remember the smiles, the clapping of little hands, when they saw me carrying a package. The children knew well that their mother would make tasty dishes from this package that they couldn't afford in those gloomy times. Even a piece of beef lard for frying kasha with sautéed onions made a heavenly dish. The children already knew that for Shabbat their mother would make cholent not with potatoes alone but with lungs, liver, intestines. A finger-licking delight. Oy! Then their mother would work miracles with that package. And I was wished all the best, and the big girl, the one that was ten, thanked me very much. I felt that I was doing something good and bringing joy.

7. “What I Remember”

I remember Siedlce as a clean, beautiful city with paved streets, asphalt sidewalks, boulevards, trees, and a beautiful park, the streets with stores and display windows. But most important were the cultural institutions and schools. The Russian Elementary School, the Russian Seven-Grade Secondary School, the Polish Seven-Grade Secondary Business School. Jews constituted the majority of the population (almost all the Christians lived at the edges of the city), and the educational institutions and cheders surpassed the Christian schools in the variety of subjects taught in Yiddish and Hebrew. Evening classes were held for adults in both languages. Literature lectures were given. The Hazomir Society was very active. It had sessions in singing, as well as literature, and a library. Many talks were given and discussions held, which attracted many university students and secondary-school pupils not only from Siedlce. In those times Jews were subject to a quota.24Pupils from other parts of Russia and Vilnius took advantage of the fact that the Jewish residents of Siedlce and its environs did not fill the quota, and they came to the city to study. This was a great win for the city. The intelligentsia came mostly from Hazomir. A certain number of workers were joined to it, and classes were given so that they would not be exploited by their employers. Poor workers were taught, and special courses were created for them. From among them later came Zionists, socialists, and anarchists. They hid and held discussions secretly, relentlessly, with animated gesturing. Some were for, others against. The Jewish population at that time, during the German occupation in August 1915, numbered about 18,000, that is, about two-thirds of the population of the city.

Siedlce did not have any industry, but it had a pipe factory in which large sewer pipes were produced. I also remember a stamp factory. My husband, who was older than I, taught die engraving in this factory. He helped the revolutionaries when he was a young boy. He provided them with printing dies for their appeals. He was in prison for a while for this reason. Then he fled to Denmark and from there to America.

Shoemakers worked in Siedlce and made footwear that was sent to the depths of Russia. There was a certain group of gaiter makers, tailors, a few brokers who traded with the landowners, and two or three subcontractors (suppliers for the military). The majority were, however, small storeowners with low-priced merchandise. I also remember an iron warehouse, a mill, a hat shop, a photographer's studio, and so forth. There were also a certain number of carpenters, house painters, construction workers, upholsterers. They mostly lived in poverty. An interesting and real Jewish life pulsed in the city.

8. “My Father's Family”25

From my father's side, I don't remember Grandfather Chaim Lejb and Grandmother Necha. But I know that my grandfather was a Talmudist butcher, and my grandmother kept house. She sold poultry and offal, fruit and goats. Sometimes grandfather helped her, but he didn't have a head for it; he only studied his books. They both earned only enough for water and kasha, only enough to maintain body and soul. They had a house full of children, three daughters and three sons. My father, Abram Hersz, called Herszke, was the fourth child. After the first three girls, my father was an unexpected guest. He was tall and had dark-blue eyes, blond hair, and delicate hands with long, slim fingers. He was a warm-hearted person, not only for his loved ones but also for strangers. When something had to be resolved, he decided and stuck with it. It always turned out that he was right. He studied until he was eighteen, but he couldn't look at the poverty in his house and the difficult life of his mother. He decided to act on his own. This was the first decision in his life that he made without the consent of his parents. He rented a large store in the Christian part of Siedlce. There he opened a modern butcher shop with non-kosher meat. He hired a worker who quartered the meat, put it on white paper surrounded by ice, and placed the whole thing into a white glass case. The merchandise prepared in this way awaited customers, who were looking at the clean and neat store with interest. In 1885 it looked not like a butcher shop but like a drugstore. Cleanliness and beauty, on top of a young salesman, drew the gazes of customers. Buyers increased by the day, so my father had to hire another helper. At first my grandfather and grandmother were shocked when they found out what my father had done. To abandon studying the sacred books and become a ritually unclean salesman was something that was revolting. But they slowly became convinced that he had done the right thing. My father was a good son; he gave all his earnings to his mother and studied the Torah and Talmud with my grandfather at night. He closed the shop on Saturdays and went to the synagogue to pray. The business prospered more and more, and the house revived. My grandmother stopped buying and selling, and my grandfather devoted more time to studying the holy books. The children grew like trees. After a time, they started saving. Now my father decided to hire a few workers and open a kosher butcher shop in the Jewish neighborhood. And this kosher butchery was also run in a hygienic way. It made a profit and brought prosperity. My grandfather slowly began to build a house. He finally built a house with four apartments and three shops. Now my father personally worked with several workers in the kosher butchery. Later he started working as a subcontractor, a supplier for the army, and he did only this. That took place when my father met my mother. Now I will describe their meeting.

My mother, the beautiful Rojzele (Róża), as they called her in the city, was being looked after for a few years by her grandmother Matl and grandfather Szamaj [Lubelski] in Stara Wieś outside Siedlce. One day, her grandmother sent Róża, fifteen years old at the time, to the city to buy some meat for the house. She reminded her to buy it at the clean butchery that Herszke had just opened. My mother was a girl of exceptional beauty. When she appeared in the city, all the young boys turned to look at her. She came to the butchery her grandmother had told her about. My father recounted this episode to us children, and my mother always nodded in agreement. When he saw her, my father was so stunned that he injured several fingers while he was cutting the meat. He tried to keep her in the shop as long as possible and asked her about everything. Who she was, where she lived, and so forth. She answered all his questions. She was not shy. He, on the other hand, did not sleep all night after this meeting. On the next day he sent a matchmaker to my great-grandmother. And that's how it happened.

My father married my mother and didn't take a penny as a dowry. A beautiful wedding was arranged, and the young couple decided to live with my father's family. They took over the bedroom, and the whole family ate meals together at one table. This harmony did not last long, and disagreements arose between the mother-in-law and the daughter-in-law. The daughter-in-law wanted more privacy, and the mother-in-law wanted to be the only lady of the house as before. She told her daughter-in-law what to do, where to go, and so on. My father came home once and found the beautiful Róża in tears. He asked his mother what had happened. His mother took him aside and said that her daughter-in-law was bad and that he had “really been taken in,” since she slept too long, didn't help enough around the house, and so on and so forth. My father interrupted her and asked, “Tell me, mother, did you bring a daughter or a maid into your house?”

After these words, she was stunned, and he left the house. He came home earlier than usual the next day and said, “Start packing, Rózia. We're moving out.”

“What are you saying?” his mother asked in surprise.

“I've rented an apartment with everything we need,” he answered with a smile.

“And what will happen to your parents?” she asked, worried.

“I have worked for them long enough. Now they have big, grown-up children. Let them help.”

APPENDIX 17.

IDA JOM-TOW TENENBAUM—THE WORST OF TIMES

Some of the Jews [in Siedlce] were doctors, some were lawyers, and a few had large stores and were well-to-do. The great majority of Jews were poor; they were tailors or shoemakers or had little grocery stores.