|

|

|

[Page 50]

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

What people called “the first aktion” lasted for four days. Four hopeless days and nights lasted the “liquidation” of an old Jewish community that with hundreds of years of effort and industry had grown to be a city and a mother in Israel; to be one of the most creative communities in Poland with about twenty thousand Jews. There remained in your ruins—aside from the five hundred seven young men whom the executioners had preserved for their liquidation work—yet a thousand living shadows who, during the aktion had hidden in bunkers, caves, covered-up holes and who now converged in the small ghetto. The killers “solemnly” assured them that they would not be harmed.

And this remained: an open cemetery with scattered bodies that lay on all the streets of the liquidated ghetto, in all the courtyards, in the attics and in the garbage heaps.

The old cemetery-Umschlagplatz and the surrounding streets—Stari Rinek, Zhidowska, and First of May—looked horrible.

[Page 51]

Hundreds of dead people, killed by various instruments of death, lay all around—trampled, stiffened bodies soaked in pools of black blood.

Most of the dead had had their clothing, their shoes, and even their underwear ripped off of them. Thus did the hometown robbers worry over them.

During the whole four days of the wild bacchanalia, the murderers did not allow the dead to be cleaned up or buried. As the sun did its work and heated the corpses, the air was filled with a nauseating odor from the unburied bodies.

Only on Wednesday morning were the Jewish police allowed to move the dead.

With the aid of some of the selected Jewish workers from the small ghetto, some people were harnessed to wagons and dragged them through the streets of the liquidated large ghetto, while others threw the bodies into the wagons, like slaughtered calves or pieces of wood, dragged them to the walls of the closed off ghetto, where, on the Aryan side, Christian workers waited. They took the loads of dead to the cemetery and buried them in common graves.

How many Jews were killed in those terrifying four days cannot be accurately determined. At a time when Jewish lives were considered worthless, no one cared to count them systematically. Consequently, the numbers given by surviving witnesses differ and contradict each other.

In those dark, hellish days, the Jewish section of the magistrate's office was led by councilman Gluchowski. As told by Leibl Mandelbaum (one of the chosen 507 who later hid in the woods and the villages), the last report was that the number of murdered Jews on those days was 3,200. According to an eyewitness who then served in the Jewish police and helped to gather the dead, the number was 2,000.

There is also no precise knowledge of the number of Jews who were transported to Treblinka. A number of eyewitnesses say 12,000, others 15,000, and still others, 8,000.

[Page 52]

No one will ever know the bloody statistics. The actual eyewitnesses, the streets of the ghetto and the earth of the old cemetery, which absorbed the spilled blood of that portion f the community, and the accursed field and woods of Treblinka, where the ashes of the cremated martyrs were scattered, are stubbornly silent and say nothing about their tragic secret.

No more the centuries-old community—Siedlce! No longer its twenty thousand Jewish inhabitants!

Now, when we note what we have encountered in the ruins of our destroyed home, we have the tragic total of the remaining statistic: about forty pale shadow-men with deeply burrowed foreheads, dull eyes, and almost all with old, gray heads on their young bodies, men who for years felt like worms under the ground, between life and death; and several score broken migrants, returned from Siberia and the taigas of Kazakhstan, sole survivors of their large families. Altogether—an unhappy small group of lonely orphans, who roam about on the roads and fields, digging and seeking a sign, a bit of ash from their nearest and dearest and from their destroyed homes.

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

A. Stary Rynek

We wander further over the ruins of our destroyed home and find ourselves at Start Rinek.

The street is an old one. One of the first Jewish streets in Siedlce. The name Stary Rynek—Old Market—remains from the time when it, together with the neighboring cemetery, were beyond the city limits and were the site of a market for cows, oxen, sheep, and horses. This was also the source of another name, used by older folk—Konski Rynek (Horse Market).

Although the place has a genuine Polish name, it was a thoroughly Jewish street, like Pinkie. Actually, it was not as wide nor as long as Pienkne. It had fewer inhabitants, did not provide as many

[Page 53]

revolutionary fighters is the days of the czar as Pienkne Street, and also did not have as many Maskilim, community activists, and pure Jewish scholars as Pienkne Street—but it had its own special distinctiveness.

First of all Stary Rynek was proud of its old, distinguished, substantial homeowners, with their long-established grocery, flour, and tobacco businesses, which lined the left side of the street, one after the other—from Warsaw Street too Dluge—and marked the real business center of the city.

On Stary Rynek lived the patriarchal Jews, distinguished, virtuous before God and before people, like the 95-year-old baker and Old Gradzisker Chasid R. Leibl Prives; there R. Chaim Shloymo Yablon and his sons conducted the oldest grocery business in the city; there lived and conducted his many-branched business such an old, established resident as R. Avigdor Ridel with his large family; his son, the most prominent mohel in Siedlce, R. Shimon Ridel, who made his living from the flour business on Stary Rynek, although his major concern was by his hand the Jewish boys of Siedlice became Jews, and to a poor man he would give several rubles after conducting the bris; there, too, lived his learned sons-in-law: R. Nachman Lev, the Tiktiner prodigy, R. Dov Berish Yom-Tov, the distinguished only son of the Szelekover rabbi; R. Eliezer Lippe Yom Tov, who boasted that he was a descendant of the Tosafist Yom-Tov; and R. Yosef Rosenbaum the astute student and scholar of the Ger rabbi. On Stary Rynek lived the respected arbitrator of business affairs, R. Sander Kantor, the Szelekover rabbi R. Yehoshualeh and many other Jews of the city.

Furthermore, Stary Rynek merited having within its borders the great city shul. On the right side of the street, right next to the old cemetery, it stood, a high, proud place, behind a white fence, with fine, twisted iron towers; with its painted image of the Ten Commandments, it reminded passersby that there is a God in the world…

The many businesses that were found on Stary Rynek attracted the smaller merchants of the city. Many small merchants from neighboring shtetls who came there to buy goods, many business agents, travelers, brokers, shady characters, carriage drivers, and porters with their

[Page 54]

horses, wagons, and handcarts, in addition to random Jewish loafers who came to observe how other Jews went about their business—all together carried on, made a racket, and went around, creating the impression that a constant fair was in progress. But when Shabbos arrived, and even more a Yom Tov or a Shabbos of the new moon blessing, when there state chazan led the prayers with his choir and people streamed into the shul from all sections of the city both for prayers and from the love of music, Jews all dressed up in their Shabbos garb, with their solemn Shabbos gait, with their taleisim under their arms, and women all arrayed in silk and velvet, in atlas and Georgette [types of fabric]. Their Shabbos necks were hung with strands of pearls and golden necklaces. With sparkling rings and bracelets on their white Shabbos hands, with their fancy shoes and their prayerbooks, with little silver locks, under their arms. Then the fuss and tumult disappeared completely. The street lost its weekday nature and put on a cloak of Shabbos sanctity, and the whole street appeared to be an antechamber to the shul, a foyer where a great many of those who pray and those who love the music stand because, thanks to the crowd, they could not gain entrance in the shul itself. There, through the wide open doors of the shul they can gather fragments of the chazan's performance, which rings through the outdoors.

For non-Jews, too, Stary Rynek was important because opposite, by the exit to Warsaw Street, was the city hall, so that this spot was the central point of the city. After the death of Josef Pilsudski, when the city wanted to erect a memorial to Poland's hero, people decided that the most appropriate spot for such a memorial was the square of Stary Rynek.

Because of the many wholesale businesses that were in Stary Rynek, the mobs from neighboring towns came with their horses and wagons and set up on the streets in order to buy different products. They unharnessed their put-upon horses and tied them to the heavy wagons, leaving them alone there with a bag of oats as they went away on business for half the day. And when they returned, they lay down

[Page 55]

on the wagons and went to sleep and grubbily snored away as if they were in their own homes…

Across from the businesses dealing in flour, sugar, herring, and rice that were set out on the ground or on the iron barrier that went around Stary Rynek Square, porters with ropes around their hips waited for a job or rested after a hard bit of work. Some ate their lunch from blackened pots that their wives brought and discussed issues, told stories, or exchanged low, porterish jokes, after which loud laughter filled the street.

For years, Jewish droshky drivers had no place to take a rest. in whatever parts of the city and on the streets where they took their droshkies, they had to put up with their Christian rivals and also from the city powers that gave them troubles until they received a set place in Jewish Stary Rynek, where they could stand in a long line of shiny black droshkies on part of the street across from the wholesalers. The harnessed horses, adorned with badges, stood with raised heads and half-sleepy expressions or flicked away flies with their long tails. The owner sat in the droshky dressed in his driver uniform, and just like his horse, was half-asleep on the soft cushion, until a passenger appeared and awakened him. Others sat in a group in one of the droshkies and talked about how difficult it was to earn a zloty since all of the Christian drivers had, under the slogan “Keep to your own,” had inscribed on their hats in red letters on white linen: “Droshky for the baptized,” so that the Jewish droshky drivers who lacked that slogan were boycotted by Christian passengers and went hungry, along with their wives and children and their poor horses…

The broad square, the only square in the Jewish area from Warsaw to Dluge Street , made Stary Rynek an important place. This was a square specially for Jews and Jewish children, who were afraid to venture into the city park lest they get hit in the head with a rock thrown by the wonderful Polish children, or lest a fierce dog rip their clothing.

[Page 56]

Jewish children felt secure there that no goyish stone-thrower would come. They had better places…and the dogs who came into the Jewish butcher shops looking for a bone were quiet and calm. They were happy that no one beat them, and they even liked to be petted by the Jewish children.

The fact is that there were no trees or green things in the square. The tiny bit of grass that began to sprout from the dug up earth was soon trampled by the proud young feet, along with the boards on which had been written, “Keep off the grass.” The yelling of the city garden overseer did not help, even when he chased after the children with his big broom. He soon grew tired, and the children played hopscotch. They scratched boxes on the ground, and they hopped from one to another. Others pretended to ride horses: one would sit on another's back, and he would gallop around; others played at soldier, in two opposing armies. They played at war, but often their play became too real and adults would have to intervene and make peace…

The girls played at “house,” rocking their “babies” in metal or paper cradles, washing clothes and cooking the best meals out of sand for their “babies”…

Many real mothers also came to the square with real strollers, in which real children either lay or sat. They came for a bit of fresh air. They would flirt with a young man whom they had known and while rocking their child, they would gossip with the other mothers…

The square also served as a place to stroll and as a refuge for various categories of Jews from different classes:

One would encounter the most prominent wholesalers, their hands behind them, thinking about their competition with other merchants, about the “refugees,” evil customers, and about the difficult tax situation, all of which made life difficult.

There were also those who constantly stood by the city hall who, when they grew tired of long hours standing in the street, would gather in the square, sit on a bench and listen to a bit of wisdom from the old Stary Rynek buffoon R. Shloyme Nisman.

From the nearby beis-medresh, those who always sat and learned often came to the square for a little

[Page 57]

fresh air and even to learn what was new in the city and what the newspapers were saying about the larger world.

If people had a conflict and wanted a religious court to make a judgment, they would come to the square of Stary Rinek. They would often take a bench across from the shul, a crowd of Jews arguing, yelling, wrangling, and fighting. In the middle of the bench sat R. Shlomo Shmuel Abarbanel representing one side and R. Sender Kantor representing there other. They listened to the flood of words and yells from both sides and had to decide who was right and deliver a judgment in this merchant's court.

And over there, in the shadow of the broad shoulders of Pilsudski's memorial, Jews conducted various transactions. They tested grains or manufacturing samples; they discounted bills and discussed old times.

Parallel to the great wholesalers, thee was also in Stary Rynek a poor, small business:

Such a business had blind Yudel always conducted among everything else in the square. He would fall in among the children, unpack his goods and wait for the children to interrupt their games and gather around him and his great selection: different colored balloons that waited to be released from their sticks so that they could escape to the clouds; mechanical toys that ran by themselves when they were put on the ground; rubber dogs that barked loudly when given a push under the arm and dressed-up dolls whose eyes closed when they were laid down to sleep. He also had an assortment of sweets: chocolates, mixed with almonds, frozen treats, red sugary candies, and many-colored lollipops on sticks. And even though it was not Simchas Torah or Chanukah or Purim, he also had such seasonal articles: Simchas Torah flags, Chanukah dreidels, and Purim graggers. Children bought, and even if one had no money, that was not so terrible. Yudel gave credit and inscribed it in his memory. He knew that tomorrow he would be paid what he was owed.

A constant competitor for Yudel's business was Naomele. She was exactly the opposite of Yudel. Yudel was tall and thin and moved quickly, while Naomele was tiny, Lilliputian, and fat. She moved slowly with tiny steps and she appeared

[Page 58]

like a fat child. You would not have known that she was thirty-something, a poor orphan, whom the community had married off to Arkel—who was also Lilliputian, as fat as she was, and also a poor orphan. She, Naomele, was the breadwinner. She trudged around holding two large bags of merchandise in her hands. In one bag was a variety of cookies, pieces of honey cake, beans, egg bagels, and other sweets. In the second bag was a great deal of writing material: notebooks, pens, pencils, scissors, rubber bands, and other things that children needed

From early in the morning, Naomele would go around with her bags of goods to the schools: the Tarbus School, the Folk School, the Talmud Torah, and in the general schools for Jewish children. These places were her business sites. On days when the schools were closed, Naomele would take her moveable goods to the square of Stary Rynek, where there were so many children.

When she appeared with her two big bags by her sides, she seemed so huge that she looked like a portable pyramid. Because she was small and broad and looked funny, the children surrounded her, as soon as she appeared. They laughed at her and bought her goods.

Naturally, Yudel was not overjoyed that Naomele invaded his territory with her goods in the square of Stary Rynek, where he had long reigned. But he never fought with her. Only, when she appeared, he would gesture with his hand and even more with his blind eyes, that thus became totally white—as if to say, “What should I do with her? She also has to live.” So once in a while, Yudel would also go with his merchandise to the schools that constituted Naomele's area of business.

Another constant business in the square was conducted by Tzlove the cripple. Both of Tzlove's legs were paralyzed, so that she could not walk. She would sit on a little bench, and she could manipulate the bench so that she move all around, wherever she wanted. In her lap she had a tray of shelled peas and beans, half of the tray with big yellow peas and half with big brown beans, covered with

[Page 59]

pepper. In the middle of the tray was a Shabbos glass for kiddish, that helped her earn a living all during the week. She sold cheap—five groschen for a kiddish-glass of peas and beans. As a bonus, she also gave the purchaser a blessing. The essence of the blessing depended on the buyer's age: for a young child she wished that at his bar mitzvah, people would have such good beans and peas; a teenager, boy or girl, she wished that at their wedding people would have such good food; for a mature man or a young wife her blessing was that they should eat such food, God willing, at a bris. For older people she wished grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and so on.

For the whole day Tzlove went around on her little stool with her large tray of merchandise among the people in the square. In the evening, when everyone began to go to the shul for the afternoon and evening prayers, she situated herself right by the doors of the shul with her tray on her knees. The aroma of hot peas and beans mixed with the sharp odor of pepper invaded the noses of the passersby, who had to give in to their inclinations and buy some. Even in the cold of winter, Tzlove would sit there on her stool with her goods. She had near her a pot with hot coals to keep her warm. She would invite her freezing customers to warm themselves, too.

Thanks to the good “geographic situation” of the square, which was right in the center of the Jewish area, among totally Jewish streets, people could feel free whenever they wanted, thanks to its intimacy; thanks to its Jewish heimishkeit, which allowed people to appear in their everyday clothing without putting on anything special. One could even leave by itself, without any special preparations, a sleeping child in a carriage, and go inside to prepare lunch—the squad and the whole of Stary Rynek was the most popular spot in all of Jewish Siedlce for teenagers and for children.

Yes, there was once such a Jewish street—Stary Rynek.

And when the bloody machine devised its devilish plan to assign Siedlce's Jewish community to a living grave—in the ghetto—Stary Rynek was the threshold to that grave.

The exit from Warsaw Street was shut up by a wall of barbed wire. O n the side, between the Pilsudski monument and the community buildings was placed an entrance to this living grave. Over the entrance was a sign inscribed in big, fat letters: “German

[Page 60]

and Polish citizens are forbidden to enter the Jewish quarter because of the raging epidemic.” A policeman was stationed by the entrance to prevent any of the Jews confined in this living grave from going out into the freer world. And no one from outside could enter the confined error and bring help, a little bread or some potatoes.

The second duty of the police at the ghetto gate was early in the morning to open the gate and allow out the enslaved Jews who marched to their daily hard labor, and at night to allow back in the worn out and beleaguered Jews who were returning “home” from their difficult labors.

And the police guard had yet another duty that did not allow him any rest: opening and closing the gate for the black wagon, which, from early morning until late at night, was busy collecting and taking to the cemetery the great number of dead who were served up by the two angels of death in the ghetto—on the one hand by the wild hooligans from the worked up bands of murderers and on the other hand by hunger, crowding, and filth—with the resulting epidemics that such conditions called forth.

By the wall of barbed wire on Stary Rynek, near the ghetto gate, was the favorite spot of the barbaric Germans, who would sit there for entertainment and amusement—this was an everyday occurrence—they would come in groups to the gate like hunters, sit at tables that the Jewish council had been forced to provide, and eat and drink—and fire shots through the holes in the barbed wire at the captive Jews who appeared on the other side. And as the victim shuddered and fell to the cobblestones, wild, loud laughter resounded through the street. They toasted each other and drank in honor of the victory of German arms, which always hit their target.

Soon after, the wagon arrived and took the victims to the cemetery.

By chance it happened that the fire that the vandals had set to burn down the community buildings with the shul and the beis-medresh had spared three buildings that the community had there, near the shul, which had been built for financial reasons: they served as

[Page 61]

butcher shops where people could buy kosher meat. Now those innocent buildings had been converted by the executioners into butcher shops for Jewish lives. They served as the ghetto prison, and woe to him who had the misfortune to go there. The road from there led straight to the cemetery.

Many tragic stories were told about what happened in those three buildings at the time of the ghetto. The tragic chapter “Ghetto-Prison” closed with the confinement there, after the liquidation of the large ghetto, of thirty girls and women, who were tortured for many hours before they were taken to the cemetery and shot. (More will be told about these thirty girls and women in a forthcoming chapter.)

In the early days of the war-bacchanalia, when the city was reduced to nothing by the fire and death from the enemy airplanes, Stary Rynek, like all the other Jewish streets, made its own contribution: a row of houses at the corner of Warsaw Street went up in flames before collapsing, burying a number of their inhabitants.

Later, at the time of the ghetto's liquidation, a group of twenty-some unfortunate Jews in a neighboring street, among the ruins, in a dark cellar, made a subterranean bunker and hid there for a whole year. In the summer of 1943, by accident a car with Germans came upon this bunker. The roof, which was covered with a layer of dirt and grass, broke, and the hidden Jews were discovered.

The unfortunates were shackled in chains and held for several weeks in the cemetery, where they were forced to work at cremating the corpses, which had piled up so much, and to clean up other traces of German crimes and horrors, until they themselves died from the hard work, the hunger, and the torture.

On the dark day of the last judgment of Siedlce's Jews, which the killers called “selection,” when the old cemetery was overflowing and could not contain the whole community, the execution grounds were broadened into neighboring Stary Rynek and its square. The once heimish and beloved earth, like that in the old cemetery, drank in the last tears and the blood of the tortured victims.

[Page 62]

Just as there in the cemetery-Umschlagplatz, so also in the square the curse of the time was afoot: The earth grew rich with the blood of the tortured community, but even after many years without the jumping feet of Jewish children, the earth lies dead, naked, ashamed, with even less greenery than earlier.

Now Stary Rynek is as quiet as a cemetery. There are no more scamps claiming the streets with their childish voices while playing hopscotch in the square or playing horses or playing house.

The old city garden watchman has no one to chase with his big broom, no one to disturb his rest, and he sits there lazily, stretches out his arms, and soaks in the sun's warmth.

There are no more shiny black droshkies with their uniformed owners that used to fill Stary Rynek; there are no more big, heavy wagons with their big, broad wagoners; there are no more porters with their ropes wound around their hips sitting on the iron barricade of the square, none of the merchants, homeowners, negotiators, beis-medresh students, nor the random Jews on the street for whom Stary Rynek was a second home.

The street is as quiet as a cemetery. The few remaining houses are decked in mourning, those that were not destroyed by the enemy's dynamite and fire. Black, damaged, strangely cold, even the little signs by their doors speak of their past glory, as we read: heirs of Ch. Sh. Yablon, Reichenbach, Nissan, Ridel—house number 9. It is like having my legs cut out from under me. I stop automatically. A terrible coldness runs through my bones. I stare through the open window on the second floor, where my wife's parents and family lived.

My heart twists from sorrow at looking into the room that twenty-some years ago filled me with so much love and took me in as one of its own. I became a member of the Yom-Tov family, a transplant in this city. How many beautiful recollections arise in my mind, how many wonderful memories of those times sit in my consciousness, mixing in with the endless sea of horrors, sadness, flooded and drowning by them.

Dragged from that room by the German murderers to prison,

[Page 63]

to the concentration camp, leaving the family behind. For a second I feel an urge, a longing to its familiar walls, its heimish furnishings—but my feet do not move. They stand there as if in concrete. In the struggle of conflicting feelings, between yes and no, no wins, because I did not want to see the place from which my nearest and dearest were led to the sacrifice.

Through the open window I see the same armoire, the same bookcase that stood there before. I see the same lamps, even the same plant pots as before. And when in the window there appear unknown faces with angry eyes that stare with cold strangeness, curious and mocking, my glance and my heart can stand no more and I walk away. No, I run away, away from there.

B. Dluge Street

We find ourselves on the second street of the living ghetto grave—Dluge, which, in 1927, when the socialists had a majority in the city council, was renamed “First of May.”

Both sides of the street, both the east and the west, were inhabited by non-Jews as well. There were also central institutions of great importance, like the Orthodox cathedral on one side and on the other the chief court, the post office building, the women's gymnasium, and others.

But most of the inhabitants were Jews from various groups. Members of the intelligentsia lived there as well as ordinary Jews: major merchants and poor craftsmen, workers and “upper class” Jews, Chassidim, teachers who gave the street its Jewish character and appearance.

In the bloody early days of the war, before the city was taken by the bands of German murderers, when their aircraft had according to their plan “accidentally” covered with fire, explosives, and death the totally Jewish streets of the city—the non-Jewish part of Dluge Street could not be defended separate from the Jewish part, and the greatest part was divided between bare earth and sheer ruins, including the popular “Yisroel-Yechiel's Beis-Medresh” and the so-called “Petersburg” Beis-Medresh.

[Page 64]

The barbed wire of the ghetto fence closed off both ends of the street: on one side, by Kochanowska, it separated the ghetto from the church. On the other side there was a wall of barbed wire by Sandowa-Posta Street, which separated the ghetto from the area of the court.

There were also barbed wire fences at the cross streets: Berko Joselowicz, Mala, and Oszeshkowa, which closed off the road that led from Dluge out to Warsaw Street.

Here and there we come across remnants of that barbed wire that encircled those enclosed in the ghetto. At spots there is a pole sunk deep into the ground. At spots, pieces of wire litter the ground. And the rusty wires stick not only the feet but also the soul and the heart when one remembers the function they fulfilled in the recent past.

Some houses remain standing on Mala and Sandowa Streets. Among them is the Dluge-Warsaw passage courtyard. This courtyard was the window for the living ghetto-grave to the Aryan side: when a neighborly Christian would remember a Jewish neighbor who had done him favors, he could sneak in a bit of bread through that entranceway.

Ghetto business was also conducted in the courtyard: if someone wanted to trade a couple of potatoes for a pillow, a piece of clothing, or a wedding ring—he did it in the courtyard, and there were many on “the other side” who wanted to make such deals.

When the Germans realized that this “illegal activity” was going on, they built in the courtyard a high concrete wall that made further smuggling of such goods impossible and thereby increased the number of deaths from hunger in the ghetto.

The wall also remains as a “memorial of destruction,” and it bears silent witness to the pain, horror, hunger, and death that took place behind it.

And one encounters other remnants from the past that recall what once was. The same butcher shop stands as it once did in the red Rogowin house, hung with different cuts of meat. Across from it

[Page 65]

stands open the same haberdashery building and the same pharmacy with the same large signs and inscriptions as before. Only when one looks more closely, one sees that it is not Yankel Tabakman starting there behind his counter not Moyshe Kruszel in his notions shop and not Yankel Sarnacki in the butcher shop. There are totally new, strange owners who look out, some with open and some with hidden mockery at the sorrowful pair of Jewish passersby.

C. The Jewish Council

Dluge Street “merited” having within it two institutions of central importance in the enclosed ghetto: the Jewish Council and the ghetto hospital.

Like all of Jewish life and all of its institutions, the former Jewish community structure was quickly dismantled when the Germans took the city.

It is understandable that in the flood of utter darkness and terror, of complete confusion that the Germans brought with them, no Jewish institutions could continue their normal work. All of them were abandoned. There were only two undertakings: the Jewish community organization under the new name of “Jewish council” and the hospital.

After an interruption of several weeks in its activities, full of confusion and terror, the community organization was revived by the Germans themselves.

As it soon became apparent, the Germans themselves needed such an organization that indirectly conveyed their thieving and extortionist orders for money and goods, for people to work, and for all their other wild demands.

At the end of October, 1939, the order came out to create a Jewish council of 25 people.

Understandably, as with every order, no one knew how to go about it, but the result of several consultations with community leaders and leaders of the political parties, the following people were decided upon:

Yitzchak-Nachum Weintraub, Dr. Henryk Loebel, Menashe Czarnobrode, Eisenberg[Page 66]

Hersh, Moyshe Rotbeyn, the lawyer Yoysef Landau, Eizik Lipsker, Yoysef Rosenzumen Yehoshua Ackerman, Avraham Altenberg, Yoel Levin, Velvel Barg, Leon Greenberg, Moshe Radzinski, David Altman, Yonasan Eibschutz, Dr. Leon Glazowski, Dr. Belfar, Dr. Shaul Schwartz, Dr. Shlomo Tenenbaum, lawyer Rubinstein, David Liebman, Moshe Greenwald, Avraham Yoysef Kornitzki, Binem Huberman.The list was submitted to the German governing council and was approved.

Later, when 3 members of the Jewish council died from the epidemics that raged in the ghetto—Menashe Czarnobrode, Yoel Levin, and Yonasan Eibschutz—they were replaced by Mendel Goldblatt, Yissachar Yablon, and Berl Czebutski.

The most senior of Siedlce's Jews, the excellent leader R. Yitzchak Nachum Weintraub, was elected unanimously as the honorary chair of the Jewish council, but this had only a decorative and moral significance. This new Jewish organization that was created in such difficult circumstances before the Jews of Siedlce wanted to demonstrate its love and unity with the old, true servants of the community, who, for half a century, had led most of the community and charitable organizations in the city, and especially with the everyday people and served them heart and soul. But actually to lead such a complex organization as the Jewish council, and to be an intercessor between the community and Hitler's rulers was beyond the abilities of an elderly man like R. Yitzchak Weintraub. So as director of the Jewish council, Dr. Henryk Loebel, director of the Jewish hospital, was elected chair. He was known as a man of great energy, of humanistic and Jewish virtues, and of cultural qualifications reflecting all of greater Europe. In the course of his activities for the Jewish council, and also as director of the hospital, he often showed that he was the right man for the job. (You must understand that I mean under those conditions)

Two circumstances dictated that the Jewish council would grow strong and become a dynamic, many-branched organization that would incorporate everything that was relevant to the current life of the suffering community. On the one hand were the wild demands of the Germans, their insatiable appetite for Jewish possessions, for Jewish lives, for laborers; the flood of discriminatory orders that fell unceasingly on Jewish

[Page 67]

heads (all through the offices of the Jewish council). And on the other hand the needs of the oppressed Jews—material, physical, psychological, hygienic, medicinal requirements and all other sorts of sorrows and pains which overflowed upon our unhappy fellow citizens in times of despair and need caused them to seek help from the Jewish council—these two circumstances were the factors behind the Jewish council's growth in stature, with so many divisions and sections and with so many staff members and clerks.

The work of the Jewish council was assigned to the following managers:

General matters—Personnel: Heschel Eisenberg; Finances: Menashe Czarnobrode; Labor: Moyshe Rotbeyn; Social Aid: lawyer Yoysef Landau; Provisions: Avraham Altenberg; Health: Dr. Loebel; Legal Matters: Leon Greenberg.All divisions and sections were subdivided and were swamped with work. The most dynamic and active, however, were the divisions whose duties involved serving the wild German appetites. Among those divisions were the work division, which had to provide people for forced labor, and the finance division, which had to extract money from the worn out people in order to pay the constant extortionate demands and other demands that the Germans placed on the Jewish council. Many activities were incumbent on the divisions that served the internal needs of the people, such as social aid, health, and others.

In addition, there were special divisions that required contact between the Jewish council and the German offices. The long-time secretary of the Jewish community, Herschel Tanenbaum, was named as liaison between the Jewish council and the Gestapo. His duty was: every morning he had to go to the Gestapo and receive their wild, sadistic demands, which the Jewish council had to carry out.

The other community employee, Ezriel Friedman, was named as liaison between the Jewish council and the German labor office and police office. His duty was to send forced laborers to all kinds of hard work that the Germans systematically demanded of the Jewish council.

Several score helpless shadow-men—they are what remains from the great old Jewish community of Siedlce!

[Page 68]

D. Extortion

In October of 1939 on the first day of its renewed activities, the Jewish council received and order from the German common to pay 10,000 zlotys in extortion money that was demanded from the Jewish population. This was only the beginning, because soon after this there arrived at the address of the Jewish council extraordinary demands from extortion money. Thus, a few weeks later, in December of that year, there was a demand for 20,000 zlotys; in November of 1940—100,000 zlotys; in March of 1941—100,000 zlotys, and from January of 1942 until the final destruction of the Jews of Siedlce, the extortion became a regular payment of 100,000 zlotys each month.

In addition to extortions of money, there were daily orders of extortion in, for example, furniture, utensils, linens, clothing, furs, jewelry that the Germans could get from Jews.

In December, 1941, the Germans ordered the Jewish council to deliver all furs and fur-making equipment that belonged to Jews.

The entrapped Jews, who for the most part suffered from hunger and need, having been robbed of the most elementary necessities, lost the power to exist and lived only on what they could sell of their possessions. They had to surrender to the Jewish council everything to satisfy the wild desires for extortion and confiscation.

Thus, for example, the vandals came to the Jewish council at the end of December, 1939, on the morning after they had brewed the shul and the beis-

[Page 69]

medresh and demanded from the council a certification that the shul and the beis-medresh had been burned in unknown circumstances.

On Purim of 1942, the murderers seized and arrested ten Jews and took them to Stak-Lacki (a village near Siedlce) and shot them there on the orders of the head of the district council of Labor Office—on the pretense that they had refused to work.

The Jewish council was forced to issue a statement that the Germans were right and that the death sentence for the ten Jews was correct.

Among many other wild extortionate schemes, particularly characteristic was the Gestapo's order to the Jewish council to prepare and organize with all its facilities (at their own cost, of course), a brothel for the pure-raced Germans, in the house of Hesche Kaplan at 11 Pienkne.

In the summer of 1942, the Germans ordered the Jewish council to present a variety of craftsmen with their tools. The Jewish council made known that these craftsmen were needed. The chosen Jews, with their tools, were sent away somewhere. Later on it was learned that the chosen craftsmen had been transported to an extermination camp.

On August 22, the black Shabbos, when a band of murderers arrived in the city to conduct the slaughter which became known as “the first aktion,” the Gestapo ordered the Jewish council to set out chicken, wine, and pastries for lunch, which the killers devoured at the Umschlagplatz during the selektion.

Later, when the Jewish council had again resumed its activities (in a reduced form) in the small ghetto, it was ordered by the Germans to pay a city fireman for his work in helping to torment the Jews, for spraying them with water, when they were suffering on that Shabbos in the Umschlagplatz.

For the first two months of its existence, the Jewish council was located in the hall of the Jewish community in the kehillah building. At the end of December, 1939, after the vandals burned the shul, the beis-medresh, and the kehillah building, the Jewish council moved to the premises of the library in “Ha-zamir” (61 Pilsudski Street). By that time

[Page 70]

the library had already been vandalized, destroyed, and shut up.

A short time later this locale was taken by the Germans for their own purposes, and they ordered the Jewish council out. The council relocated to Szenkewicza 14. Then later they moved to 34 Pilsudski (Epstein's house) and then again to 14 Pilsudski (Shmerl Greenberg's house).

With the closing of the ghetto, the Jewish council found its resting place in the house of Zelnick's heirs at 36 Dluge. The courtyard there became a vale of tears in the closing ghetto. All of the bitter orders came there, all the bloody decrees and wild demands that the vandals could devise in order to dishonor and steal the lives and possessions of the beleaguered Jews in the ghetto. All of the despairing and broken Jews came there to pour out their troubled hearts to the council members. Some were naive enough to believe that the Jewish council could do something to cut through the evil decrees, and some just wanted to pour out the sorrow and need of their hearts for a few minutes.

The Social Help division of the Jewish council came those who were swollen with hunger. They came seeking a bit of bread and something to allay their hunger.

Every morning hundreds of Jews came to the courtyard of the Jewish council because they had been called up for forced labor for the German killers. In the neighboring cross street from Dluge to Browarna they were arranged in rows, and under the command of the ordnance police, they were led to various places both inside and outside the city for hard labor.

E. The Tragic End of the Jewish Council

On the same day when the large ghetto was liquidated and the Jewish community was forced to the Umschlagplatz, that black Shabbos of August 22, 1942, the Jewish council was also liquidated.

False was that illusion, just as so many illusions were proved false, that many of the Jews in the ghetto had maintained, that belonging to the Jewish council entailed certain privileges,

[Page 71]

that having a document attesting to one's membership on the council would be a treasure in a difficult moment. Many people believed this. They regarded Jewish council members with jealousy, as though their lives were more important, more secure, as if they belonged to an organization that even the Germans needed, so that they would not kill such members. Many would have paid a great deal for such a charm as a Jewish council membership card.

Being a member of the Jewish council also gave the privilege of not having one's goods confiscated day in and day out, of not being extorted. It also provided the possibility of avoiding forced labor.

But when the day came for the final judgment on the whole community, the members of the Jewish council, along with their associates and assistants, even those who had used the opportunity to seek favor with the killers, were just like all the other Jews and suffered the same fate as all their brothers

After the great slaughter of the first aktion, of the twenty-five council members, only five remained, because they had hidden. They were Yitzchak Nachum Weintraub, Moyshe Radzinski, Moyshe Rotbeyn, Heschel Eisenberg, and Dr. Belfour.

Four members—Dr. Loebel, Glazowski, Schwartz, and Tenenbaum—were killed two days later when the hospital where they worked was liquidated.

All the rest, together with the whole community, were forced to the Umschlagplatz and from there, all together, transported to Treblinka.

Along with the Jewish council, almost all of their associates and assistants were liquidated in the first aktion.

Thus was killed Herschel Tanenbaum, the long-serving secretary of the community and latterly the liaison between the council and the Gestapo. Almost everyone envied him because of this unlucky post, with his acquaintance with the higher levels of the killers and murderers as they ordered whatever their wild fantasies devised. He, along with his whole family, was sent to Treblinka.

[Page 72]

The liaison between the Jewish council and the German labor office, Ezriel Friedman, for his “service” in arranging Jews for forced labor, merited a “special handling”: on the day of the selektion, he was allowed to live, along with with his selected assistants, but two days later he was called out of his home at the corner of First of May and Targowa by Gestapo head Duba himself, who, with his own bloody hands, shot him by the wall of his house.

On that day of destruction, August 22, the premises of the Jewish council remained empty and worthless. A band of killers entered and utterly demolished it, stole the funds that were kept there as well as anything valuable. The whole rich archive with all its documents and minutes, which, in clear words and numbers, conveyed the martyrdom and pain of Siedlce's twenty thousand people, they destroyed.

In the time of the ghetto, the Jews lived in a troubled era and came to the Jewish council seeking advice, a word of consolation, and perhaps a bit of protection.

On that tragic Shabbos, on a day of massive slaughter, when all avenues of rescue closed upon our unfortunate fellow citizens, many Jews sought protection from the Jewish council, and when they could not find such help, they took to the cellar and other hiding places in the building. These unfortunates, about thirty of them, were discovered by the German and Ukrainian murderers, dragged into the courtyard, and shot.

Among them were the family of Ephraim Zelnick, Yakov Levin, and other prominent Jews.

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

Opposite the slaughterhouse of the old cemetery-Umschlagplatz, among the other ruins, standing in a little garden, like an old aristocratic woman, behind an iron fence, in the shape of the letter “ches,” are the white building of 26 Dluge Street.

[Page 73]

The buildings have always served humane purposes: for a number of years they housed a Polish Folk School for Jewish children, a so-called “Shabbosvokes,” where Jewish teachers taught Jewish students Polish history and culture.

Before the outbreak of the war, the Red Cross occupied the buildings and conducted its medical and aid activities for the city.

In October of 1941, when the large ghetto was locked up, the Jewish hospital was brought to the buildings, since it had been outside the borders of the ghetto—on Swietojanska Street.

In those dark days, when the Angel of Death had cut down the inhabitants of the ghetto in such large numbers with his associates—various epidemics that had been called forth by crowding, hunger, and need—the hospital was the only oasis in the valley of tears that could help the sufferers even in a small way, giving some of the ill and pained a bit of medicine and food, a roof over their heads and a clean bed—things that for the majority of ghetto dwellers were fantasies that in their “normal” conditions they could not attain.

The director of the hospital was the energetic and totally dedicated Dr. Loebel, who devoted all his strength and industry in organizing the aid work of the hospital. To this end he also used his position as chair of the Jewish council. He had the ability, whether on his own authority—which he

All of the divisions helped, to the extent possible,

[Page 74]

the ill, the suffering, the hungry, the swollen, and all the unfortunates whose number was so great in the ghetto.

And when that “black Shabbos” of August 22 arrived, when at the Umschlagplatz, which was only a few score steps from the hospital, there lay so many Jews who had been beaten and shot—then, too, the forceful Dr. Loebel intervened with the German killers and extracted permission for the hospital to come to the aid of the wounded.

The doctors and the nurses, clad in white hospital garb, carried many beaten and wounded Jews into the hospital and cared for them. The injured were celebrated like little children: their lives were saved. Fabish himself declared that the hospital, with its wounded, should be spared. Those who were shot in the hand or the foot were saved. A small number of healthy people also used this opportunity to be saved from the Umschlagplatz: the nurses threw white hospital garb on some people who then helped gather and carry the wounded, and in this way they managed to get into the hospital or onto the street.

But the joy of the rescued did not last long, for the fists of the murderers also reached them.

How the hospital was liquidated, how there ill, the doctors, the aides, and all the personnel of the Jewish hospital were murdered is told by several survivors of that time, and especially by Mrs. Leonie Halberstam-Greenspan, the only surviving witness of this tragic chapter:

On Shabbos, August 22, the dark day of the great slaughter, there were about a hundred patients in the hospital, men, women, old people and children, among them several ailing Roma who were receiving treatment. In the course of that tragic day, the number was increased by additional ailing people as well as healthy people who had been saved from the Umschlagplatz. For a whole day the hospital personnel, as well as the patients, had the illusion that they were safe. But that same evening, when the small ghetto was created for the working men who had been chosen in the selektion, Fabish ordered the hospital director,

[Page 75]

Dr. Loebel, to leave his residence in the hospital and go to the small ghetto. People saw this as an omen that the hospital would soon be liquidated.

Dr. Loebel proudly responded to the executioner: “I will not abandon the hospital. I will share the fate of my ailing sisters and brothers.”

In this way the hospital continued for two full days between life and death, between on one side beautiful illusions that people talked themselves into, that the murderers would not dare to destroy a healing institution full of sick people, and on the other side the shadow of death that loomed on all sides.

On Monday, August 24, during the day, when the last victims from the Umschlagplatz had been taken to the train ramps, to the Treblinka death train, the hospital was invaded by a band of German and Ukrainian murderers under the leadership of Fabish himself.

It appeared that a glance at so many sick people and at the hospital personnel in their white uniforms confused a little the murderous thoughts of the bloody sadist and he issued contradictory orders, each one countering the one that preceded it.

Thus he ordered that all the sick should go out to the hospital courtyard. Then he countermanded this order: No, all the sick should lie in their beds.

In another order he called on the doctors to go each to his department, to his patients, and in the presence of the doctors he ordered his men to open fire on the patients lying in their beds. The short, staccato firing of handguns accomplished their goal—ending lives.

In the gynecological section there were ten young, nursing babies who had the misfortune of entering this murderous world only days, weeks, or months earlier. Their parents had, with great devotion, managed to get them into the hospital before they themselves were transported to Treblinka or had hidden in an underground bunker, thinking that the hospital was a safe place where the children would be rescued. Among them were the children of Sarah Yom Tov-Halberstam, of Chana Piekorsz, Sabke Benkowicz, Bracha Radashinski-Neuman, and others. Each of these infants received a bullet in the heart.

When they were finished with sick, there came another order:

[Page 76]

“All doctors, aides, nurses, and all other personnel should go out to the courtyard.”

In the courtyard, arrayed in a line against the wall, were Dr. Henech Loebel with his wife and son, Dr. Leon Lazowski, Dr. Shaul Schwartz, Dr. Shlomo Tenenbaum (Dr. Belfour, sensing the end, had escaped from the ghetto some nights earlier, hidden in a village, and later committed suicide), the two beloved older aides Yosef Olaberg and Yakov Tenenbaum the nurses Feige Friedman, Sarah robinowicz, Edushe Alberg, Rivkeh Barg, Epstein from Lodz, the laboratory worker of the hospital Lola Saltzman, the young hospital employees Tzeshe Temkin, Dvorak Goldblatt, Branke Shapirman, and others who worked in the hospital.

Fabish the executioner ordered that the first bullets should go to the “head dog”—as he referred to Dr. Loebel—and he fell first, along with his wife, from the quick shots of a handgun with these words on his lips: “Death to you, murderer. The Jewish and Polish people will outlive you!”

All the doctors, aides, nurses, and other workers fell from the short, staccato shots. Along with them died all who believed that the killers would not attack a hospital full of sick people and who sought protection by hiding there over the previous days, pretending to be ill or to be employees. Among them were Ester Saltzman with her young daughter Rahel, Berl Czarnobrode with his wife, Mrs. Levin-Eisenstadt, Ewo Greenspan, and others.

For a long time these people had lived there as an extended family: the doctors, the aides, the nurses, the employees. They worked together as a fellowship, caring for the unfortunate of the ghetto with love. They left the world in fellowship, all together, clutching each other—they fell wearing their white hospital gowns, as if in shrouds, in a single pile, one body having fallen on another, one body lodged up against a second, and this—among the greenery and the flowers, under the bright, clear, blue sky with the beautiful full beams of a late summer afternoon sun. Those many sunbeams played in and reflected from the dazzling white kittles of the dying heap of people and in the freshly shining blood that streamed from all sides into a pool and turned into a

[Page 77]

river, absorbed by the earth of the hospital courtyard and ran further and more quickly, before it cooled and congealed—to sink deeper into the earth and moisten the roots of the many plants and flowers that decorated the hospital garden.

The lead executioner of this murderous group, Fabish, who himself led the slaughter at the hospital, rejoiced—at the sight of so many dead and so much spilled blood he was like a drunkard. His murderous eyes gleamed. He rubbed his dull face, running with blood and happiness, and nudged his nearest comrade and co-worker, the purely evil wolfhound. He led him to the pool of blood and ordered him, “Drink, comrade, from the dogs's blood.” And that dog drank the fresh, warm blood.

From the open doors and windows of the hospital building, the cries and dying confessions of the patients lying in their beds reached out to the street, strangled cries for help that no one heard. The quick revolver shots cut short their terrible cries and transformed them into the quiet wheezing of a death rattle that was heard under the quiet coughing and terrible calls that emanated from the heap of people who had been shot by the hospital wall, and all combined into a single horrible symphony of death, which became quieter and quieter until it was utterly silent and disappeared into the deaf hole of that accursed summer day.

The Germans' bloody method of murder worked perfectly to destroy the hospital: the shot bodies of the children, of the ill, and of the hospital personnel had cooled off. They had ceased their death convulsions and were quickly thrown into the large wagons, still wearing their hospital garb. The wagons had been prepared earlier and had waited by the ghetto entrance.

The Jewish police were required to carry out this gruesome job of taking the murdered patients from their beds and loading them on the wagons, together with the executed heap of doctors, aides, nurses, and hospital personnel from the courtyard. But not the

[Page 78]

little children. The Germans “played” with them, dragging them by the feet from their beds, several at a time, dragged them with their lolling heads, and threw them on the crowded wagon like slaughtered little dogs. On the open wagon, through the lively streets, they were taken to the cemetery, where graves had already been prepared. They seemed, on the cobblestones of the streets where they were led, to illustrate with their blood, which dripped from the wagons, the story of their murders.

It took a long time for the wind to carry dust and for the rain to wash and for the sun to dry the streams of blood from the cobblestones of Siedlce's streets.

From that slaughter had escaped Lola Saltzman (the daughter of Sholem Saltzman), who worked in the hospital laboratories. She had been shot in the armpit and fallen to the ground, and she was covered by the dead bodies of her mother Esther and her younger sister Rochel, who two days earlier, on that tragic Shabbos, had come to hide with her in the hospital. After the killers left, she crept out from under the pile of corpses and took backroads, through gardens and fences, on all fours, and crept into the small ghetto. After many changes and false starts, she found a hiding place in Opola (a village near Siedlce) with other Jews. Shortly before the liberation, they were denounced and all were killed in their hiding place.

Rusze Landau, the wife of the lawyer Yosef Landau who was rescued on that tragic Shabbos by the hospital personnel, was hidden there as a nurse. Unnoticed by the killers, she made it to the hospital garden. From there, through gardens and fields, she managed to arrive at the small ghetto, where, two days later, along with twenty-eight women, she was shot at the cemetery on Fabish's orders.

Young Vitek Loebel, the son of Dr. Loebel, escaped. In the last minutes before the executions, he managed to run through the hospital garden. He suffered for a long time in different woods and hiding places and finally fell

[Page 79]

Into the hands of the Polish police, who killed him.

The survivor of that horrific slaughter, Mrs. Leonie Greenspan-Halberstam, told us the bloody story. It seemed as though Providence assured that at least one witness would remain of that terrible slaughter who could tell the world how one people—the Germans—had destroyed another people, large and small, from nursing children to the aged with its invalids and those who cared for them—in order to counter the suspicious deniers, who would not believe and who would maintain that the Jews invented horror stories to besmirch an innocent people.

Mrs. Greenspan-Halberstam, on that that tragic Shabbos, was also rescued by the hospital people. Donning a white hospital gown, she acted like a nurse. On Monday, at the time of the slaughter in the hospital, when she, with the others, was taken to the execution wall to be shot, she, unnoticed by the killers, escaped to the hospital garden hid among the tall plants and by back roads managed to get to the small ghetto. She suffered all the levels of Gehenna at that time in underground bunkers on the “Aryan side” and—she gave us all the horrible details of the tragedy at the hospital, which stands to us as a testament for all the martyrs who suffered there, of the idealistic doctors aides, nurses, and other workers who with love and dedication until the last minutes of their lives did the sacred work of helping their unfortunate brothers and sisters in the ghetto and who, at their deaths, called out, “Death to the killers! The Jewish people will outlive you.” The testament of all the tortured patients the broken ones, who were shot in their beds, and death had frozen on their lips their last curse for the murderous world, and the testament of the little babes, the day-old, week-old, month-old tiny ones who, like little angels had committed no sins except that they had the misfortune to be Jews in the bloody era of Hitler and therefore received bullets in their tender, gentle little hearts as they lay in their white cribs with sweet little smiles on their angelic faces, dreamily smiling with their little lips, dreaming that they were sucking at the breasts of their mothers, who had already been

[Page 80]

transported to Treblinka—the testament of all who had been tortured and made to suffer, who had one final bequest: Tell it, tell it, tell it! Remember! Never forget!!!

|

|

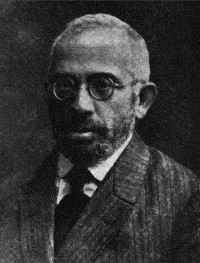

| Asher Urszel |

|

|

| The 80-year-old community and Zionist leader Moyshe Eisenstadt and his wife Itta. They were taken in the first aktion to Treblinka. |

|

||

| People begin taken to the Treblinka death train |

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

The closest house at 24 Dluge Street, which stands surrounded by a little garden, set off from the workaday street, was built by the aristocratic Orszel-Neugoldberg family several decades ago. Through luck, it stands whole today. It stands as it once did in the shadow of its old chestnut trees and dreams of its past glory.

If houses had mouths and could talk, this house would have a lot of interesting stories to tell. It would tell how under its roof dogmatic Jewish traditions and modern European innovations coexisted in peace like old Jewish twins.

On a summer's afternoon, one would often hear through the open windows the haunting Gemara melody coming from that part of the house where old R. Naftali Neugoldberg or R. Asher Orszel would be sitting. And soon the sounds of Tchaikowsky or Mendelssohn being played by the children on the piano would come out of a second window and fill the street.

Old, religious Jews would stand there and listen: some at the first window, some at the second. Whispering quietly, shrugging their shoulders, waving their hands, as if to say, “Such bizarre ways”—and then move on.

And young, up-to-date people would drink in thirstily the beautiful tones of the piano and look jealously at the open window.

From his father, the outstanding, fine Jew R. Itzel, Asher receded a strictly religious education and was a fine student with a sharp mind. At 18, he became the son-in-law of the brave, notable Chasid of the Parisower rebbe, R. Mendel Beyer. Together with his father-in-law, during the first years of his marriage he would travel to the rebbe to celebrate with the Chasidim, but that did not last long: young Orszel soon connected with the

[Page 81]

free Haskalah movement, which in those days was making inroads in the learned Chasidic circles. The rise of political Zionism had an especially strong influence on Orszel. With youthful enthusiasm he threw himself into the movement and remained an active member for the rest of his life.

Orszel threw off the superstitious covering of his former way of life, but he continued to hold by tradition, to learn Gemara and other sacred volumes, and he even enjoyed looking through a Chasidic book, but at the same time he read modern Hebrew and Yiddish books. He cast off his long caftan and the shtreimel and wore European clothing, and instead of going to the rebbe for Chasidic celebrations—he went to Zionist conferences and celebrated Zionism.

Religious Jews used to whisper quietly that Asher Orszel would study a page of Gemara with his head uncovered, just like a Litvak (Heaven forbid)…

In Asher Orszel's study, on his large, oaken bookshelves, his leather-bound Vilna Talmud volumes stood shoulder to shoulder with the new Hebrew Encyclopedia, like brothers and sisters who had grown up together. Next to the old books like The Guide for the Perplexed, The Kuzari, and The Duties of the Heart stood the latest issues of “Ha-Te'kufah” and the most recent publications of Bialik and Tchernikowski's poems; the Kedushat Levi of R. Levi Yizchak of Berdichev stood next to Herzl's Old New Land.

And not only on his bookshelves did the ancient and modern spiritual treasures stand together harmoniously. In his graying head, as well, the old and the new had dwelling rights. One complemented the other. And always, when R. Asher Orszel spoke or explained something, he would throw in a word of Gemara or something from Tanach or a sharp Chasidic story, mixed together with liberal Maskilik ideas.

For explanations, R. Asher Orszel always had time and patience. Even when he was very busy, he would do his work and then explain. At every opportunity, at every event and action—he would tell a story or offer a word that was always right to the point.

If a Jew came into his iron business or into the merchant's bank where he was the director about some business matter—he first

[Page 82]

had to hear a word of Torah from R. Asher Orszel; if a Jew was downcast, had a business entanglement, was involved with the tax office, a conflict over an inheritance, or a question about making a marriage, he would come to R. Asher Orszel to ask advice. And the advice that R. Asher Orsel gave was accompanied by a beautiful proverb, with a verse from Tanach, or an encouraging word (that he had for everyone), and people always left him happier than when they arrived.

He had a wonderful disposition.

For his friendly demeanor toward people he was beloved and praised by everyone—he was called “Zeyde”—“Dziadek” [in Polish]—and the city bestowed on him its highest honor in electing him as a councilman on the city council, chair of the Zionist committee, member of the Tarbus committee, managing member of the “Ezras Y'somim,” “Moshav-Z'keynim,” and what else? There was not a single organization in the city where R. ZAsher Orszel was not among the ten leaders.

At all meetings, gatherings, or random get-togethers that concerned an organization—no matter whether it was about finances, welfare, or cultural-Zionist matters—everywhere Orszel was the central figure, everywhere he had something to say, not as a formal speaker but with a bit of good advice, a word here and there, a story, or a proverb. And when he met with the Zionist, pioneer, or Tarbus young people, he felt right at home—he carried himself not like a man of seventy but like a youngster.

Orszel was beloved and honored also among the Christian population, and many Christians came to him for advice and to hear a story with a proverb or witticism.

It is interesting to characterize R. Asher Omszel by recalling the following fact:

At the city tax office, there was a consulting commission whose members were assigned by different communal organizations. Commissioned by the city council was Orszel. He was chosen unanimously by both Jews and Christians. For his bold and energetic guardianship of the interests of the taxpayers at the commission, Orszel was investigated by the tax officer and the city council was

[Page 83]

ordered to elect a second delegate to replace Councilman Orszel. For a second time the city council unanimously elected him and announced to the tax office that Orszel was their most suitable candidate, and they also made it known that the tax office had to right to question him.

Consequently a quarrel arose between the tax office and the city council, a quarrel that the city council won so that Orszel remained as the representative on the tax commission.

R. Asher Orszel's house served as a salon for the reception of important Zionist leaders. When Yitzchak Greenbaum, Dr. Shiffer, and once Shaul Tchernikowsky came as guests to Siedlce, they were received at R. Asher Orszel's home, where solemn banquets were arranged during which actions were proclaimed for Keren Ha'y'sod, The Jewish National Fund, or for Tarbus. And once when the Grodzisker Rebber came to Siedlce, he was received at the other side of the house, where his brother-in-law, Naftali Neugoldberg, lived, he who had not abandoned the customs of the old way of life (and who used to visit the rebbe).

I saw R. Asher Orszel, z”l, for the last time after the German hordes tore into the city. The cannonade had ceased, and we came out from our hiding places outside of the city to see the damage to our burned up houses. When I asked where he had been and what he had done during the days when the enemy's airplanes had ceaselessly spread death and destruction, R. Asher Orszel answered with a smile: “Since I had never in all my life seen such a spectacle, I stayed outside, near my home, and put on my glasses so I could better see and wonder at the interesting events…”

In October of 1939, in the first weeks of the dark control over the city, a band of Nazis in their trucks went to his iron warehouse and stole everything, then beat him up. But then—and also later—R. Asher Orszel continued to tell his stories, spread Torah with his comments to the Jews who in those difficult days cameo to the “grandfather”, as they had earlier, in his

[Page 84]

business to forget for just a little while the bitter suffering of everyday reality.

R. Asher Orszel also died honorably: when he felt what the German murderers had planned to do the Jews, he did not wait for them to sent him to the gas chambers of Treblinka. He lay down in his bed and died a normal death, mourned by his relatives and friends, of whom he had so many. No one envied him: a successful Jew who was worthy to have such a luxurious death.

Orphaned and alone among the ruins, his little palace stands deep in its garden, holds itself in the shadows of the old chestnut trees, and dreams nostalgically of the old Gemara melody and the newer notes of the piano that have been abandoned and made silent forever. Over the front door, near the street, a sign hands with an inscription from its new heirs: “Evidence Department of the Siedlce Magistrate.”

Further on lies an empty field, exactly as if there had never been any life there. In some spots there still remain parts of the wire fencing—vestiges of those dark, hellish days. And since the earth has not been walked upon by human feet, nature has taken over: the earth is thickly covered with grass and wild plants.

We measure with our feet the lots on which houses stood: Weingarten, Marchbein, Oppenheim, Shmerl Greenberg, . I look for the spot where I lived during the last seven years, where I grew up, which was part of my essential self. Over there was the courtyard on whose right side stood the two-story wing of the large building which contained my family's nest. In the first days of the bloody flood, the enemy's fire and dynamite destroyed it all. Later on the Germans, together with home-grown thieves, hungry for abandoned Jewish property, took whatever was left: goats, stones, metals, and anything else that the fire had spared, so that nothing more was left than a flat little burial mound, overgrown with grass.

Such overgrown burial mounds are found on the whole area, up to the corner of the street, where there is a small shaft that indicates “Yisroel Yechiel's Beis-Medresh,” the immaculate little beis-medresh where

[Page 85]

those who prayed and learned often included such patriarchs and aristocrats as R. Yitzchak Nahum Weintraub, R. Hersh Yosef Czarnobrode, R. Noson Dovid Gliksberg, R. Moyshe Abbe Eisenshtadt, R. Yisroel Rubinstein, R. Yishaiah Rabinowicz, and where Kaddish would be said for deceased relatives by modern Maskilim, enlightened Jews who wanted to hide their attendance at shul, like the leader of the Folks Party in Siedlce. Menashe Czarnobrode and the old, aristocratic Shmerl Greenberg. Of the beis-medresh nothing remains but that little flat space, overgrown with grass.

It makes us feel as if we are in an abandoned cemetery. An almost tangible silence rules there. The only living things we encounter there, in what was once a thickly inhabited Jewish area, are two goats. One eagerly devoured the young springtime grass, while the second lay spread out, warming itself in the sunlight and casting tin its animal way a pair of large, wondering eyes on the peculiar visitors.

I dig a little in the mound on the site of my former home. I seek something that will recall my former warm home, something from among my loved ones' possessions. I find a few scraps of burned and mangled house goods that were worth nothing to the thieves. It seems as if they cry out from their rusty open grave and ask dumbly: “Why embarrass us? Why such an empty end?” And they beg, wordlessly, to be put back, so their shame will be hidden.

Translated by Theodore Steinberg

Further wandering through the ghetto ruins through the former Post Street continues with difficulty. Nothing remains to remind one of the formerly tidy little street with its white houses all built in a similar style. Everything lies broken, crumbled into formless heaps, scattered over the whole breadth of the street, in mounds, in valleys, through which one has to creep and jump until one comes to the other end of the street on Aslanowicza (Prospektowa), Blania, Yatkowa—into the so-called Old City, which was once the center of Jewish poverty.

[Page 86]

There, in the streets of the Old City, lived toiling Jewish laborers, wagon drivers, beggars, itinerant merchants, teachers, and those who lived on the merits of a rich relative in America who would send a few dollars, as well as those who were simply poor, who lived there because their grandfather or their father had left him a little room as an inheritance and who derived a living from a small table of goods in the city bazaar, which he had to carry out early every morning and drag back every evening in a bag on his back, back to his poor little room.

The women of the Old City were active col-workers in their men's businesses and sometimes ran poor little businesses themselves. They had to spend the whole day in the store, in the butcher shop, or by a stand in the bazaar. They left their children alone in God's care to lay in the courtyard with the children of the neighboring butcher who had gone to a nearby village with his partners, who had combined their funds in order collectively to buy a cow. And they, the butchers, had to spend their whole day in their shops and leave their children alone. And as the children played outside on the cobblestones, they hoped that nothing bad would happen to them, God forbid. The streets there—Aslongowicza, Blania, Yatkawa, Browarna—were quiet and still, as quiet and still as their inhabitants. Seldom did a car or a carriage or a wagon pass through, unless—when the wagon driver or the droshky driver who lived there went in or out with his team of horses, at which time he would pay close attention so that he would not hurt any of the children.

When a mother brought out to the street a dish of warm food to feed her playing child, she thought, too, about her neighbor's children, who were on their own, and she gave them the same amount to perk them up. She knew, this ersatz mother, that tomorrow or another day she would have to be away and leave her children alone and another neighbor would feed her children.

Life in these little streets of the Old City passed quietly. The Jews there did not rush about. They moved slowly, at a more leisurely pace than the Jews on Pienkne, Kilinske, Warsaw, or Stary Rynek. Even those who went to work every morning went at a comfortable pace, not running as those others did. It was not because they were lazy or industrious, God forbid. Remember, most of the inhabitants were hardworking people who lived by the sweat of their brows.

[Page 87]

Nor was it that big-city life had not come there to disturb small-town comforts. Because there were more broad open spaces there, people could see more of nature, more of the sky and the ground than in other streets, as well as a bit of greenery, a tree between the small wooden houses—all of this contributed to a quieter and more comfortable way of life for the inhabitants, so that they proceeded in a more leisurely way, like people in a village. Even the four-cornered clocks with their chains and weights the hung on the walls in the small dwellings and were driven by brass pendulums seemed more leisurely, quieter, and peaceful than the modern alarm clocks in the homes on other streets—truly, what was the rush? Everything would work out.

Those who dwelled there were quiet, peaceful folk, unpretentious about living in the city. They led a quiet, peaceful and gray life. Just like the Old City area of Siedlce, so was the lifestyle there old-fashioned, primitive, small town.

At many homes one encountered, behind the doors or windows, a tied-up Jewish animal, a goat, which considered the world while chewing its cud, little more than skin and bones, like its owners. The little milk it provided constituted half of their income. The other half came from teaching, teaching the youngest children, or being a sexton in some shul or beis-medresh, being a broker for apartments, or selling trinkets or shoes or whatever—all those means of earning a living that only Jews have mastered and can live from.

Sometimes there was a little store that resembled the stores that children make when they are playing: a few onions, some carrots, parsley, with a few bags on a shelf—a display of Jewish poverty.

The store was run by the wife of a teacher, a sexton, or a wagon driver with the help of her children. From a man's salary one could go hungry for half a day, so they had to find a second income. One could transform a window on a door into a little money maker [by creating a room to rent]. Raising higher the lower window, one had to bend over to enter, like when one bows during Aleinu in shul, in order not to bang one's head, and thus—a second income.

Others, the more well-off citizens, did a little business: they

[Page 88]

cultivated a few hens, ducks, geese, while others even had a milk cow. From the few pails of milk that one got from the said cow, one could take some outside of the city to a big farmer and make a business from the milk. His wife would take it with a dipper into neighboring houses where the women would eagerly buy it—milk from a local cow…

Others had small gardens where they grew some greens for themselves: onions, carrots, some cucumbers, and some had an apple tree or a pear tree.

In one of the modest houses was a home-factory where children's toys were made. It belonged to the proletarian bourgeois [?] Moyshe Grobia. A soup of young men and women sit on small benches and make the toys. It seems as if children are sitting there playing with their own handiwork. They are happy, the children with their pale cheeks and darting eyes. They know that their boss is a socialist, tending toward communism, and he will not trouble them, so they sing happy songs as they work.