|

|

WSPOMNIENIA I OPOWIADANIA O MIASTECZKU RATNO

Memories and Writings

By

Translated into Hebrew

|

|

|

[Page 11]

Translated by Jerrold Landau

[Page 12]

We are not pretending to research the fundamental history of Ratno from the time of its founding, and it is doubtful if any of our readers would be interested in such research. What interests us and you are the Jews of Ratno, and everything that took place with them in that town. To our sorrow, the sources on this topic are very few, and all we have to rely on is brief articles in various encyclopedias or books that were published in Poland during various times. It seems to us that the most reliable information about the beginnings of Ratno is found in the book by Michael Balinski and Tadeusz Lipinski that was published in Warsaw in 1885. This book tells the following about Ratno:

“Ratno is an open city whose houses are built of wood and are erected between the bogs. A palace surrounded by large bogs is located on a hill near the town, next to the Pripyat River. The Tur River also streams through. Ratno is approximately 20 parasangs (miles) from the city of Chelm and 14 miles from Lubomyl.[1]

In the first half of the 14th century, Ratno and the surrounding region was conquered by the Lithuanian Duke Gediminas. This was after the kingdom of Halycz broke up and the State of Poland was weakened as a result of the wars with the Crusaders. Following this, the area was ruled by the heirs of Duke Gediminas: Liubartas, the Duke of Volhynia, (the Prince from Wladymir) and the ruler of the district of Chelm. After he had overcome the Lithuanians, who were also engaged in battles with the Crusaders, King Kazimierz the Great arranged a peace treaty with the great Lithuanian Duke Algirdas. According to this treaty, the district of Ratno and all of the surrounding land passed to the government of Poland, and thereby the district (Starostowo) of Ratno was formed.

According to the census of 1569, there were 278 houses in Ratno that year. The tax on each house was 3 groszy, plus 6 groszy for the bathhouse. Aside from this, there were 25 empty lots that year, as well as 33 people who lived in rented dwellings and paid a tax of 1 groszy, and 1.5 groszy for the bathhouse. The bath fees were not for the landowner who lived in a palace, but rather served as the salary of the bathhouse overseer Mebolbir, who also received 6 florins from the palace of the landowner. Since the auditors wrote that Mebolbir the overseer only received 4 florins, we have taken the latter to be accurate.

In earlier investigations, it was written that there were 24 pasture meadows and gardens in Ratno, but we only have found 19 of such. The payment for salt was not made despite the fact that no less than 1,000 pounds of salt were produced that year, the price of each being 10 groszy. There are 7 butchers here, each of them paying a tax of 15 groszy.”

[Page 13]

The first mention of Jews in Ratno in the middle of the 15th century can be found in the book “Chadashim Gam Yeshanim” (New as well as Old) by the historian A. A. Harkavy, Section I, page 10. The following is written there:

“The sixth witness (to the expulsion of Lithuania) was the Karaite physician Reb Avraham, the son of Yoshiahu of Truki. In his book of cures that is found here in manuscript (the manuscript in the Spanish Caesar collection of St. Petersburg), the following article is written:

'The expulsion of our ancestors (that is the Karaites) from the land of Lithuania and the Jews (i.e., the rabbinical Jews) who were found in the Kingdom of Lithuania took place in 5255 (1495). The name of the king who expelled them was Alexander. His brother, Olbrecht King of Poland, received them, and they remained there in the city of Ratno until the year 5263 (1503). That year, Olbrecht sent them back after the death of this aforementioned brother.'”

Harkavy adds the following to these words: “There is a degree of uncertainty about these words, for King Olbrecht of Poland died in the year 5266 (1506), and Olbrecht had no dominion over Lithuania. However, the Karaite is correct about the time of the expulsion, which took place between the years 5258 - 5263.”

It is evident from these articles that Ratno served as a place of residence for the Karaites who were expelled from Lithuania for a duration of eight years. There is support for this, because Karaites lived in the city of Luck in Volhynia until the most recent period.

We find information about that era of the early period of Ratno in the annual publication of Volhynia (Roozwik Wolynsus) published in Rowno in 1931, pages 3-4: “The peace treaty between the Lithuanian Duke Liubartas and the Polish King Kazimierz the Great from 1366: According to the treaty, King Kazimierz received Belz, Chelm and Ludmir (Wladymir) and received a row of settlements located on the east of the Turia (Tur) River: Horodlo, Lyubomil, Turisk, Ratno, Kamen, Chachersk, and Oblucyn.”

On page 9, it says: “Zygmunt, the son of Kistut the Duke of Lithuania transferred to Poland, in accordance with the treaty settlements on the border of Volhynia, such as Ratno and others, on October 15, 1432.”

On page 10: “The Lithuanian Duke Sangoshki attempted to take by force the Volhynia cities Ratno and Lubomyl from Poland in the year 1440.”

On page 13: “Again, in the year 1443, the Lithuanians attempted to cut Ratno off from Poland. A similar attempt was made in 1454.”

We find the first exact and trustworthy information about Jews in Ratno in the Lustracja (registry) that was maintained in the Starostowa of Ratno, from 1565:

Among the citizens and householders in Ratno, we also find the following Jews: Shmerker, Shachna, Leibka, Zelig Shmulewicz, Zalman, Yakush, Yidl, Yosef Abramowicz, Mordish, Moshe Aharon Lewkowicz, and Immanuel Lewkowicz. There is also a Jewish synagogue. The Jews pay 3 groszy for every house, and also a bath tax of 3 groszy per house. The Jew Zalman also has a grazing pasture, for which he pays a tax of 3 groszy per year.

[Page 14]

A Jew leases the right to sell liquor, for which he pays 120 zloty per year. The Jews pay to the palace (that is to the landowner / poretz) a royal tax of 15 zloty per year that is called “Sachosz.”

In another source, “Jurajska Encyclopedia,” Dr. Philip Friedman, who was searching for information about Ratno in all sources in response to a request from the editor of the book on Ratno that was published in Yiddish in Argentina, found the following lines:

“Ratno -- a city in the district of Chelm during the time of the Polish Republic. According to the Lustracja of Ratno from the Starostowo in the year 1565 (quoted above), there are 12 Jewish householder in Ratno, as well as a synagogue. In the Hebrew sources, we find a note that the Karaite Jews who were expelled from Lithuania in 1495 settled in Ratno and lived there until it was returned to Lithuania in the year 1503.”

A general census took place in Volhynia 200 years later, in the year 1756. According to that census, we find that there were 210 Jews in Ratno. In the year 1847, the Jewish community of Ratno already numbered 1,065 souls. Fifty years later, in the year 1897, there were 3,098 residents in Ratno (according to the general population), including 2,219 Jews.

In the geographical dictionary that was published in Warsaw in 1888, we find the following definition of Ratno on pages 542-43:

“Ratno -- a town on the Pripyat River, at the place where the Tur River empties into the Pripyat, in the district of Ratno (the third district) in the province of Kowel, in the Horniki government. The town is located a distance of 6.5 verst (a verst is an old Russian unit of distance) from Horniki, 19 verst from Zablotja, 48 verst northwest of Kowel, and 357 verst from Zhitomir, on the old road from Kiev to Brest Litovsk. In 1870, Ratno had 458 houses with 2099 residents, 61% of whom were Jewish. It has three Pravoslavic churches, one Catholic church, one synagogue, 20 stores, and 3 fairs. A police division and court solicitor (Inquirant) are headquartered in Ratno. There is a bridge over the Pripyat River behind the town. The Catholic church was built of stone in the year 1784. However, prior to that time, there was already a monastery that had been erected prior to 1504. Today the Catholic community numbers 351 souls.”

According to the entry in Guttenberg's Encyclopedia, Ratno belonged to Poland from the year 1366, and became a city in 1440. In 1921, the population of Ratno was 2,410, including 1,554 Jews, for a total of 64.5%.

We find a more significant description of Ratno and its residents in the book of Y. T. L. Lubomirski.

The following is a summary of the material in that work that is relevant to Ratno:

“The city of Ratno is situated between rivers that surround it from all sides. The land is marshy to the point that it is sinking due to the weight of the stone houses upon it. The palace in the region of the city was built during the days of King Zygmunt August of Poland. It is situated on an artificial hill. No trace of the palace remained several decades later. Stefan Czarniecki

[Page 15]

(A Polish Hetman, the highest commander of the army during the days of King Jan Kazimerz during the 17th century[2]) issued the command to drive many wooden pillars into the bogs in order to build stone houses upon them. However, already in the 18th century, these stone houses sunk into the bogs, from which old wooden houses stuck out. The water reached the thresholds of the houses. A Jewish beggar stands next to the threshold stretching out his fishing rod... On the other hand, a Christian youth, more brave, rolls up his pant legs, dips his thin legs into the water, and fishes for little fishes with his bare hands in the surrounding water.” It seems that no special attention is given to the city of Ratno in the historical sources. Despite the efforts of Dr. Philip Friedman to collect whatever is possible, it is difficult to form a complete and reliable image of the town from the 15th century until our time due to the scanty bits of information, which at times even contradict each other.

Translator's Footnotes

by Fishel Held

In 1938, a booklet entitled “Memories and Impressions from the City of Ratno” was published in Kowel by the M. Weinberg printers. Its author was Fishel Held of Ratno. In the introduction to this booklet by Aharon Yaakov Ginzburg, it says that Fishel Held was the only person in Ratno who remembers events and people. He wrote his memories in Hebrew and translated them into Yiddish. Here we bring sections from this booklet.

Ratno was founded approximately 500 years ago, during the time of the rule of the Polish dukes of the Sangoszko dynasty. The city is located on fields that today belong to the Russian Church, next to the Vizhovka River. During the war between Poland and Sweden in the years 1706-1707, the city was destroyed and its residents were killed. The survivors who succeeded in escaping returned and rebuilt Ratno. At that time, the old cemetery was built, where all of those killed during the war were buried in a mass grave. A small hill on the eastern side of the old cemetery is the only remnant of this mass grave. The few residents of the old city who survived included Reb Yaakov Ratner, who was known as a Tzadik. Nothing remains in writing about him, and we know only what our parents told us about him. The writer of these lines once saw in “Raskin's Table” one line that said, “Reb Yaakov of Ratno died in Krakow in the year...,” however, I do not recall the year listed as his year of death.

The leaders of the new city included some residents of the old city who remained alive after the aforementioned war, including the honorable and important Reb Chaim Mechenivker and his son Hirsch. Thanks to their efforts and money, the old synagogue was erected at that time, at the same time as the Catholic monastery in 1784, with the assistance and supervision of the regional governor (wojewodzina) Sosnowska, who then ruled over Ratno and its region through the authority of the government of Poland. After her death, she was buried in the bounds of the monastery, as was later on her daughter. Both of their graves can be found to this day in that monastery.

Reb Leib Sarah's,[2] the mystic, sat and learned in the attic of the Beis Midrash for a long time. Reb Chaim Mechenivker and his son were known for their generosity and dedication to communal affairs. As is told, Reb Tzvi (Hirsch), Chaim's son, had seven sons and one daughter, whereas his younger son, Pinchas Pulmer, had seven daughters and one son. The well-known Avrech family later stemmed from them and spread out throughout many cities in Poland and Russia. They were given the family name “Avrech” during the time of the “First Russian Revision” which was a type of census of all the Jews of Russia and Poland, for before

[Page 17]

this “Revision,” all of the Jews were considered to have disappeared. Then it became the fortune of Yossel the son-in-law of Reb Tzvi Mechenivker to be called by the name Avrech, in accordance with the verse “and they called before him Avrech”[3], which referred to the Righteous Joseph. This name then became the family name of his many descendants, including many Hassidic and Misnagdic Jews, rich and poor, maskilim and Torah scholars, as is found in any family.

Members of the aforementioned Mechenivker family brought as a teacher to their children someone who later became known as the “Maggid of Ratno,” Reb Tzvi the son of Reb Dov, who lived in their courtyard in Mechenivka next to the village of Buzaky, 20 kilometers from Ratno. He taught Torah to their children. This teacher was immersed day and night in the service of G-d. The elders of the city tell about a wondrous deed of his that took place during his first years of service. A woman in Mechenivka had difficulty in giving birth. Her situation was very serious and everyone gave up on her life. It was only when this teacher prayed for her with great devotion after immersing in the mikva that she gave birth in peace.

An awesome story is told from the later years of the life of the Maggid of Ratno. It took place in the Beis Midrash on Simchat Torah during the “Atah Hareita” prayer before the Hakafa (Torah circuits). The author does not recall exactly what took place, but this was certainly a wondrous deed, for he became known as a “worker of wonders,” and was given the title “The Maggid of Ratno.”

The Maggid did not have his own Hassidim, as was the custom of Tzadikim, but this writer of these lines heard from an elder Hassid of Kobrin that Rabbi Moshe of Kobrin would often mention the Maggid of Ratno and even bring down things in his name or tell stories about him. Apparently, both of them belonged to the same group, and used to travel together to the holy Rabbi Shlomo of Ludmir. To this day, various customs of the Maggid are followed in Ratno, such as the recitation of “Barchu” at the end of the Sabbath evening service, and other customs that stemmed from the Hassidim of Karlin. It is known that during his youth, the Maggid saw the Baal Shem Tov himself in the city of Brody, but due to the crowds, he only succeeded in seeing his back but not his face.

The Maggid had no sons. He married off his daughters to Ratno householders. To this day, there are Jews of Ratno who boast of being descendants of the Maggid of Ratno, including: Reb Meir Karsh who was known as Reb Meir Birker, Yisrael-Lipa Bergel, David Greenstein, and others.

The Maggid died on the 9th of Nissan 5578 (1818) and is buried in the old cemetery. Masses of people stream to his grave to this day. The graves of honorable Ratno natives, with fine pedigree and character, can be found next to his burial canopy. Many Jews, both men and women, come to visit his grave during the month of Elul, to pray and to place notes of petition.

|

|

|||

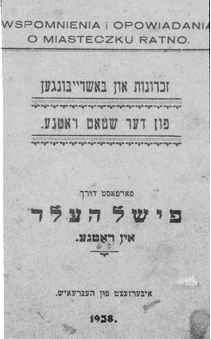

| The cover page of the booklet of Ratno by F. Held | ||||

After the death of the holy Rabbi Yaakov-Aryeh, who was known as the Kabbalistic Rabbi (Harav Hamekubal), Rabbi Yitzchak of Niskiz ascended the rabbinical seat of Ratno. During the time of his rabbinate, no Jew of Ratno attempted to do anything

[Page 18]

without receiving the advice or consent of the rabbi, whether in matters of business, marriage matches, or civic affairs. They regarded him as a “seer” who was able to see distant things, and many wondrous deeds were attributed to him. It came to the point that it was accepted within the community that if anyone was so brazen as to do something against the will of Rabbi of Niskiz, he would not live out his year. Let those who believe -- believe.

It is told that he had a pleasant appearance and he became known throughout the Jewish Diaspora. During his later years, many rabbis and Tzadikim from all over Poland came to him. Ratno was his crowning city. He would live in Ratno for several weeks a year. He had a home in Ratno and his own mikva (ritual bath) in the yard of the Trisk Shtibel. For a long time, people believed that this was the mikva of the holy Rabbi Yaakov of Ratno, and barren women from various places would come to immerse in that mikva. Only later did it become known that this was not the place of the mikva of the Maggid of Ratno, and that the Rabbi of Niskiz authorized it.

The rabbi's last trip to Ratno took place in the year 5623 (1863), five years before his death. It seems that Ratno was very dear to him, and the householders received him with great honor. Among the stories told about him, it was said that householders from Ratno and Kamin-Kashirsk entered his court in Niskiz one Sabbath. Those from Kamin-Kashirsk were brought to a table with wine in bottles, whereas those from Ratno were served wine in clay pitchers. The rabbi said, “The war of Ratno is better to me than the peace of Kamin.” (The joke being that “krieg” in Yiddish means both “war” and “pitcher,” and with the word, “shalom” (peace) he referred to one of the honorable people of Kamin-Kashirsk whose name was Shalom.) Others said that when he was asked from time to time about his dispute with the Maggid of Trisk, he answered that this dispute is an omen for a long life...

The name of the Rabbi of Niskiz is inscribed at the top of the ledger of the Chevra Shas (Talmud Study Organization) of Ratno, for in the year 5609 (1849) peace prevailed between the two organizations that preceded it. This ledger is found in Ratno to this day, and it contains the signature of the Rabbi of Niskiz. In the introduction to the ledger, he wrote in his own handwriting that he is a member of “this and what comes after.”

He died in Niskiz on the 20th of Shvat in the year 5628 (1868) at the age of 75, or some say, at the age of 80. After his death, his book “Toldot Yitzchak” was published. It is a Torah commentary in Kabbalistic style.

On the anniversary of his death, many candles are lit in Ratno and a banquet takes place. Some people own small books of Psalms, which people say, were sold by the Rabbi of Niskiz himself. Such a small book of Psalms are hard to find, and the person who owns it would protect it as the apple of his eye, and would not part with it for all the money in the world.

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ratno, Ukraine

Ratno, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 24 May 2012 by LA