|

|

|

[Page 237]

by Dov Berish First, Tel Aviv

Translated by Miriam Leberstein

If an accidental guest or big–city traveler happened to wind up in our town he would have noticed only two major streets with a market place between them. A more observant visitor might have also noticed a few military buildings, the symmetrically–built barracks, as well as the river that bordered the town on the right. Nothing else would have struck their eye.

But we townspeople who spent the best years of youth there saw the town in a very different way. So, come along with me, all you dear friends, the few who remain, still wandering, or in your new homes. Come, with the deep love and great yearning that you took with you and let us refresh our memories of our old grey little town which has, for us Jews, disappeared forever. Let us take an imaginary stroll in and around our town.

Once, before the advent of the Nadvishlaner train, which in the last years before the Holocaust would stop off in our town ten times a day, there was the road that connected us to the wide world and especially to the nearby capital city, Warsaw, and reached out to other roads.

When you came out of the sandy lanes of the town onto wide Warszawska / Warshawer Road , lined on both sides with tall chestnut trees, you sensed, along with the small of fresh air, a difference in the construction of this part of town, which was in effect the gateway to the capitol city. Immediately to the right there stretched a long tall fence that enclosed the beautiful fragrant garden belonging to the parish house of the Catholic priest.

Opposite stood two buildings belonging to the half–Polonized German colonist Lentz. In one of them was a tavern run by Abramovitsh, a former worker in the Vinogradov's china factory. There young people who had gone off the righteous path would drop in to play billiards and at the same time eat a bit of pig meat to see if would choke them immediately, or if it was just a sin like all others for which one would be punished after death. The second house was a nice one–story structure built before World War I which during the German occupation housed the town hospital.

When talking about the days of the past, before World War I, when Nikolayka [derogatory nickname for Tsar Nicholas] was still the boss of all Crown Poland, we can't omit the little wagon which held a crippled man, which was a part of the Warshawer Road.

At the very end of the road, near Abramovitsh's tavern, in the shade of a tall spreading chestnut tree there stood, summer and winter, from morning to late evening, a small square wooden wagon, covered with rags in the midst of which sat a lame man, a cripple, with a twisted face and crooked fingers, who begged passers–by for money to buy bread. Who he was, where he came from, the cause of his illness – nobody knew. Every evening you could see an old woman pushing the wagon in the direction of the Piaskes [lit. sands; a poor neighborhood of town].

There is a story connected with this cripple,

[Page 238]

an occurrence worth recalling. By testifying as a witness, he sealed the fate of Dovid shoykhet. Dovid shoykhet was a strong, healthy man, a son of the well known Avigdor Melamed. He was a strict Gerer Hasid and a Koheyn [descendant of the priestly class] to boot. He had a wife and many children and was the chief shoykhet [ritual slaughterer] of Nowy Dwor. Suddenly, rumors arose about his unbecoming behavior, behavior inappropriate even for an ordinary young worker, let alone a shoykhet. They said that this hot blooded man had sinned with a non–Jewish woman. The town was in an uproar. What a thing! Such a fine, upstanding Jew, a shoykhet, a Koheyn, and he goes to a prostitute! Things were in turmoil and the most important witness who saw and heard it personally was in fact the cripple. The Jewish community fired him [Dovid shoykhet] from his position as shoykhet and in the end the shoykhet, in great disgrace, had to go abroad with his entire family.

Now let us continue our stroll along the road. After the two buildings belonging to Lentz, there was a vacant, low–lying area that belonged to the lumber warehouse of Itshe Meyer Hirshbeyn. This area would turn into quite a nice lake when the Narew overflowed its banks in spring.

Further on, on the same side of the road, was a half–story wooden building housing a post office. Jewish mothers would stand there in the morning, their hearts pounding, waiting for the old postman Piotrkovski to see if there was a letter from their children overseas. The Jewish boys would come here in groups to pick up Hatsifirah [“The siren,” a Hebrew newspaper] or even Fraynd [“Friend,” Yiddish newspaper] from far away St. Petersberg and on the way back to town would discuss the latest political news, holding debates and giving new interpretations of an article by Nokhem Sokolov.

Across the way, on the right side of the road, off to the side, in the midst of fragrant acacia trees, stood a small stone house which with its round stone pillars strongly resembled a small abandoned princely palace. In this house far from the Jewish part of town lived and presided the rabbi of Nowy Dwor, Ruven Yehuda Neufeld.

Why hadn't our rabbi settled in the heavily Jewish section of the town near the besmedresh [house of study also used for worship] and the mikve [ritual bath], as is appropriate for a small town rabbi, and was the way in all the other Jewish towns in the Polish countryside? The Nowy Dwor Jews didn't understand it, and would mutter about it, especially late on a cold winter night, when they were returning home after a long rabbinical court session and were worried about encountering a drunken Russian soldier on the deadly quiet road, or even when they simply heard the howling of a vicious dog from the nearby Christian homes.

From today's perspective, with the passage of time and taking into consideration the personality of the rabbi, who became one of the most prominent figures of religious Jewry in Poland, it seems reasonable that he should seek out this quiet spot. This man of aristocratic bearing needed a peaceful place where he could continue his religious studies. The rebitsn [rabbi's wife] also surely played a role in this. She wanted to run her household the way it was done in the house of her rich father, the contractor Reb Moyshe Yekl Blat.

[Page 239]

The rabbi's house actually marked the end of Jewish Nowy Dwor on this side of town. Beyond it, there lived no more Jews. But we want to see all around our town, so we will continue on our walk along the road until its farthest peripheries.

Right after the rabbi's house, on the same side of the road, in a lovely flower garden, stood a one–story house with glassed in, multi–colored verandas. It looked like a summer house built for a visiting big–city nobleman seeking respite in the shade of trees among the flowers after a hard life of carousing. For a certain time after World War I, the rabbi's son, the later well known community activist Nokhem Neufeld and his pretty wife Khanke Zilbertal, lived here.

Right next to the house, in a small garden, stood a tall cross, facing the road as if protecting all who passed with its holiness. Here, we should relate an unusual occurrence involving the cross, which struck fear into the town Jews. This is what happened.

The town's Christians, led by the priest, decided to replace the old cross with a new one. One day the new cross was installed with a great ceremony, attended by many Christian women. In the middle of the cross was a small, shining Jesus which in the sun seemed to be covered in gold. A few days later, some devout Catholics, piously kneeling before the cross, raised their eyes to see that the Jesus had disappeared. There was a great outcry. Such sacrilege! And there were some among the Christians who spread the rumor that this was the work of the Jews, that they had stolen it.

Don't forget that this was a time when Polish anti–Semitism, under the leadership of Roman Dmovski, the inciter of the anti–Jewish boycotts, was poisoning the minds of the Polish masses. So the Jewish community was terrified by the false accusation, and “in the city of Nowy Dwor all was in an uproar.”[1]

But, as it is written [in Psalm 121:4] “The God of Israel does not sleep,” and the police found the culprit within a few days. And who was it? A good Catholic, who was among those responsible for putting up the gilded Jesus. It seems he was sure it was pure gold, and he couldn't resist the temptation. And the Jews rejoiced as they did in the story of Purim when Haman was defeated.

After the cross, there began the so–called industrial section of town. Just after the cross there was a long, grayish fence that concealed Vinogradov's china factory. It was the largest china factory in Poland, and the founder was a Lithuanian Jew, with the Slavic–sounding name Vinogradov. The owner had always lived in Warsaw and for many years the factory did not hire Jewish workers. But in the last few years before world War II, after the owner's son Mikhal had taken over the business, Jewish workers gained access and the factory became an important source of employment for the town's Jews.

This same Mikhal, after surviving the Nazi death campaign, returned to the town and took over the factory again and was

[Page 240]

murdered in his home by a Polish gang.

On the other side of the road was Vakhter's mill. Shloyme Zalmen Vakhter was a former carriage driver in Warsaw who became rich by obtaining a patent for using rubber instead of iron wheels on carriages. After becoming rich, he bought a big house in Warsaw and at the end of the last century he built in Nowy Dwor a modern steam mill with the newest rollers, which he imported from Germany. He himself stayed in Warsaw, where he continued to run a carriage business, although he was no longer a driver, but had a whole group of young drivers who paid him a fee for use of his carriages.

This Reb Shloyme was a nasty person and he drove away all the town Jews who would hang around the mill trying to get a day's work there. Often, the clerk of the mill would come out to see them. He was a sincere, cordial Jew with a beautiful white beard and innocent blue eyes. This was my own father, Reb Yisroel Khaim, may he rest in peace, who was the real boss of the mill and an expert in grains and flour. This refined, scholarly man, an ardent Gerer Hasid, often had to endure crude verbal abuse from the oafish nouveau riche owner.

Although it was situated on the non–Jewish edge of town, and employed no Jews except for the clerk, the mill was a kind of island of Jewish life. All day long, Jews could be seen there. Some came to do business, buying a couple of pud [about 36 pounds] of flour for a good price, or bringing grain to sell or to have milled. Some just came for no special reason, having hitched a ride on a peasant's wagon that was bringing rye or wheat to the mill, trying to get a whiff of what was happening there.

There were also people who would drop in to hear news from the outside world. They would visit with the clerk in his office, drink a couple of glasses of hot tea, take a look at the newspaper, chat a bit about politics. Meanwhile, Reb Yisroel Khaim would engage in a bit of Jewish study, telling a Hasidic tale, sprinkled with a joke here and there. And all of this was done with true Jewish kindness, interspersed with sighs and groans and with a “May God will it,” with great faith that God will help and Jews will be liberated from the Tsar's hands.

But on one day a week the atmosphere of holiness would retreat from the mill. That was the day that Reb Shloymele Zalmen would come down from Warsaw to find out what was doing in “his” mill and settle the accounts for the week with the clerk. On those days the town Jews would stay away, frightened of the nasty, growling rich man from Warsaw.

Just as Reb Shloyme Zalmen's transformation from an ordinary carriage drive to a wealthy man had been unnaturally sudden, so too was his death unnaturally sudden, shocking the Jews who hung about the mill, although of course they had often seen that nothing can counter God's will and that money can't save you from death.

It happened on a summer afternoon, while Reb Shloyme Zalmen was sitting in his wide armchair in his princely home, his own four–story house on Tavarava Street. He suddenly noticed smoke rising from the building

[Page 241]

where his new rubber–wheeled carriages were stored. Panic ensued. A fire! And Reb Shloyme Zalmen, who was an impetuous and foolhardy man, shot up and ran to rescue one of the valuable coaches. The choking smoke hit his face and he fell dead on the spot.

When the sad news reached his clerk Reb Yisroel Khaim First that summer evening, he gave a deep sigh and with tears in his eyes whispered, “Blessed be the true judge” [traditionally said upon hearing of a death]. That was the way of the Jews of those times; they quarreled, suffered insults and curses from someone, but in the final accounting, it was sighs and tears and “Blessed be the true judge.”

The closest neighbor to the mill – as they said, “on the other side of the wall” – was the brewery owned by Old Man Bitner. They were quite close neighbors, but had distinctly different characters. The mill was run in a Jewish manner, always noisy and full of activity, but in the beer factory you felt a German sense of order, a quiet focus, which the non–Jewish owner had brought with him from the Poznan region.

In the mill, the entry gates stood open all day, as if it were a public square. But at Bitner's the gates were always closed, and if you wanted to enter the courtyard you had to pull a long wire that led to a bell located in the watchman's room. The watchman was a tall, fat Christian with a long blond mustache and shifty eyes. By the time he responded to the bell, you could already hear the howling of the four–legged guard, a well–fed bulldog who pulled at his chain with such haughtiness as if he were the most important boss of the brewery.

If a Jew wearing a long caftan appeared at the gate, the dog was beside himself, jumping and pulling at his chain as if he were having a fit. The boss, Old Man Bitner, was just like the watchman and the dog, and so were his dissolute sons, who later followed in his path, doing legitimate and non legitimate business with Jews, and only with Jews, and yet unable to bear to even look at them.

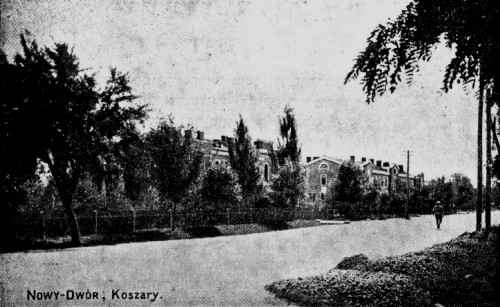

Farther on, along both sides of the road, were the red brick military barracks, which with their impressive appearance and massive construction gave a bit of respectability to our town. As soon as you approached, you could see amid the red brick buildings a building shaped like a half moon, which evoked great curiosity among the passers–by. From time to time, you could seen people pushing out of that building a large round hot–air balloon with a gondola attached, in which sat 3 or 4 observers, and watch as they were lifted slowly into the sky.

This half–moon shaped building housed a military balloon division, which a few years prior to World War I was turned into an airplane division for the Russian army. Our small town folks were by that time already familiar with these clever machines that lift themselves up and fly into the sky.

The road was also the most popular place to take a walk, which our young people liked to do in the evening. Some went as far as

[Page 242]

the mill, some as far as the tollgate at the city limit, and some – couples in love, who were walking on air – went beyond the tollgate, on this broad highway with its zigzagging kilometers, which ended in the noisy commotion of the capital city.

On a summer Saturday afternoon, the road took on a Sabbath appearance. Half the town set off, all dressed up in their finest, for a long stroll to walk off the heavy Sabbath meal. Right after finishing off the rich cholent [traditional Sabbath stew], the parents would fall into a deep sleep, to rest after a week of hard work, or just for the pleasure of it, and the young people would go for a walk. Some would take along book or newspaper to read, others went with the hope of meeting a girl they knew, with whom it wouldn't be appropriate to walk together in public.

After the tollgate they would turn off a bit to the right and enter the nearby woods, which was actually the goal of the stroll. There in the sparse pine woods they would indulge themselves in “what makes the world go round” so as to have a taste of paradise on earth.

There you could also hear heated political discussions about everything in the world. There, years before the Tsar was overthrown, they issued their own death decree for Nikolayke; there it was foretold that the Tsar must go.

Deeper into the woods, you could hear whispered words, such frightening (for that time) words as “strike,” “revolution,” “Bund.” Deeper still, in an even shadier spot, you could see a boy who worked as a servant or shoemaker in Warsaw, and had come home for the Sabbath, taking out a forbidden proclamation, which sought to settle scores with the entire world. As Tevye [character in a story by Sholem Aleichem] says, “He spoke against God and His anointed and about bursting their bonds.”

Such a young man would surround himself with a group and everyone would prick up their ears and devour his every word. What was happening in the workers' exchanges in Warsaw, how Borekh Shulman threw a bomb at the commissar of Police Station #8, and more such terrible stories, that made your hair stand on end.

Other groups, more middle–class young people, would also gather around people with news of the wide world, but their stories had more to do with Jewishness than with the wide world, and one also heard words no less scary at the time, like “shekel,” “Congress,” “Uganda,” and “Dr. Hertzl” [related to the Zionist movement].

Right after the barracks, the rails of the Nadvishlaner train cut across the road. Every couple of hours the train from Warsaw to the Mlave border would roar through, stopping to drop off the few Nowy Dwor passengers at the two train stations on either side of town, Nowy Dwor and Modlin. There, where the road was divided by the shining railroad trains, at the tollgate, stood the carriage driver's house. That was the tell–tale sign that this was the border of the town.

Footnote

[Page 243]

|

|

|

|

by Shmuel Top

Translated by Miriam Leberstein

|

Longing

The blue evening sleeps on the Narev's deep banks.

its youthful pace as joyful as of old

The graying evening dreams on the green banks

My mother's busy in the house; I hear her quiet step, her song.

The evening has captured the red flames of the sun.

My father reads me poems, I swallow up the sound

Blue evening, stars, the sun has hidden itself.

Yizkor melody – there's a longing in your sound |

[Page 245]

|

Midnight. The wind has extinguished the stars. From Pomiechov port the shadows arrive – Jews who were scattered there alive. A cry of terror sounds as if it comes from mouths filled with sand.

In the wind I hear my mother's voice, the sound Nowy Dwor, Summer, 1950 |

|

Dreams

At night my mother comes to me in my dreams.

They form a circle of glowing red ashes.

Stick feet wobble, hands of bone are raised,

At dawn the dusty ash of ghosts

My mother melts away, a smoke of sorrow.

She weeps and my father weeps too, with red tears. Warsaw, November 11, 1947 |

[Page 246]

|

Taking Leave of My Father

That evening, disquiet embraced the darkness.

I came to say a quiet farewell to you.

I breathed in your breath

Your beard caressed my face like a rose.

Like a bird I left your nest. Warsaw, February 18, 1949 |

[Page 246]

|

Visiting the Graves

My lips pressed tight together, I whisper a prayer:

Make of me everyone's orphan,

Teach me a new kaddish |

[Page 247]

|

Let wings carry me to the crematoria of snuffed out lives over the graves of brothers who sleep nearby so that my heart may flutter there, like a sail to catch the raging winds so they don't disperse the ash. Shvidnits, September 1946 |

by Simkhe Pinker

Translated by Miriam Leberstein

There, where the Narew met the Vistula, but never merged with it, keeping its black stripe separate from the foaming whiteness of the Vistula – that is where my memory still goes, recalling summer days and cheerful young people.

In summer, the youth of the town would enjoy themselves on the banks of the Narew, which were abuzz with life: individuals and couples strolling; groups out on a excursion; sports matches; and on the river itself, kayaks and rowboats of the various sports clubs. And masses of people, young and old, kept coming.

Some came to bathe at the end of a hot day, some came to relax on the shore. On Friday and Saturday the shore was filled with Jews. People sat on the grass near Keler's and near Nokhem Neufeld's mill and at Old Man Zilbertal's sawmill, various sports competitions were held on the sandy place between the blocks of wood. And they kept coming…

The Narew flowed to the Vistula, the Vistula was white, and everyone saw the wondrous thing – the black stripe of the Narew's waters never mixed with the whiteness of the Vistula. You could see that black stripe continue for kilometers.

There we spent our youth; there our tears remained.

|

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki, Poland

Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 25 Mar 2015 by LA