|

|

|

[Page 309]

by Mordechai Ciechanower, Ramat-Gan

Translated by Dr. Joseph Schuldenrein

The day the war broke out–September 1, 1939–intense anticipation spread across the local population, as our town was at the German-Polish border. That same day we took off from our homes, places we had lived in for years, abandoning familiar surroundings and fleeing to safety in unfamiliar towns and villages; as far away from the burning wreckage as possible. But it was near impossible to escape from the stealthy German enemy–the planes–which began bombarding the area from the outset of the invasion. They targeted towns as well as defenseless fleeing citizens; there were corpses strewn in fields and everywhere.

Beginning on Day 1 escapees and refugees streamed out of their homes from all over, Pruzhnitz and the surrounding villages, and not just Jews. A number of folks remained in Makow, while some kept moving further east and south. That said, many of the local Makower Jews remained in town. Those who stayed took in the refugees willingly and provided them with lodging in their homes. Based on experiences during the First World War, the Makower Jews believed that their town would be safer than others. That is what they felt initially, lacking any notion on what the next day might bring. No one had any idea of the speed of the German onslaught, the suddenness of it all. Schools shut down immediately, people were out of work, folks wandered the streets as in a daze, transfixed to the German news updates blaring across the radio waves. No one could imagine that the Germans would murder defenseless and unarmed citizens in plain sight. Then there were those who felt that the Polish army would turn back the assault. Beginning on Day 1 stores were closed up and the loss of food supplies and inventory was felt directly. Merchants began hiding their products for fear of break-ins and looting. The Makower Rebbe, Rabbi Eidelberg, left town that Friday for Warsaw. The roads both in and out of Makow were sealed off immediately. A general sense of panic overwhelmed the populace. And it wasn't only the Jews who stole away from town, but also Christians who loaded up their meager belongings on wagons, and in some cases packed in their animals as well.

[Page 310]

But most of the refugees poured out on foot. Small contingents also departed by buses, making their way through the clogged crowds; everyone doing whatever they could, to distance themselves from the front. Those running away included rich and poor, healthy and infirm, young and old, families as well as individuals. Nevertheless a large group--perhaps the majority–remained in Makow. The rich and the middle class appeared to rely on their capital as well as faith and God. And the poor felt “What can they possibly take from me? Surely they will supply us with food, at least.” The fear, however, was pervasive. By nightfall no one had the courage to venture out in the street. That first Friday night and Shabbos there were only isolated minyans in the synagogues. Subsequently, minyans were held solely in private homes.

The Polish Army in Retreat

The radio broadcasts formally announced the German bombardments across Poland. Warsaw was hit as well. The news from the front was equally dire. By Monday, the fourth day of the invasion, we knew that the Polish military was already in retreat. On Tuesday morning there was a deafening explosion. We assumed that Makow was in the throes of the bombing offensive. As we were running away we knew what was going on; that the Poles blew up the bridge over the River Oziscz. In addition to the military, the Town Council elders, the mayor, and various police divisions took flight as well. The town fell into complete chaos. The sounds and screams of panic were everywhere. And the Germans kept streaming in. Most locals took to locking themselves into their homes; no one dared as much as to poke his nose out the door. At most we peered through open windows to get an idea of what was about to unfold. It was Tuesday, September 5, between 11 am and noon, that the initial vanguard of the German army formally entered Makow. They drove in on motorcycles and armed vehicles mounted with machine guns; the soldiers were heavily equipped with hand grenades. They yelled out “Have no fear, nothing will happen. There is nothing to worry about”. The onlooking residents along Pruzhnitz Street bore witness to the scene, as they peered through the cracks and shattered window glass facing the boulevard.

That same evening, September 5, a German car drove down the street and proclaimed through a loudspeaker, in Polish and in German, that “the German army has occupied Makow and will continue to advance”. And further, they continued, under penalty of death, the residents were ordered to surrender their guns and small arms by 6 pm that same day. They were put under a strict curfew at that hour as well.

[Page 311]

All the while the drone of motorcycles echoed through the streets of town uninterrupted. No one slept that night and well into the next morning. By sunrise those walking outside were confronted with signs bearing the Nazi swastika on both sides of the street. They contained instructions on how residents were to behave going forward (surrendering arms, etc.). That same day Jews entered town from Krasnosheltz and surrounding villages, reporting on horrific acts of violence perpetrated by the Germans upon local Jews as they began round-ups for work details. They caught me and 10 of my friends the next day and drove us to Ruzhan, 20 km from Makow. When we got there, we were instructed to unload blocks of coal from a set of small wagons and to load them up onto other vehicles. No one at home had any idea as to what happened to me. We were forced to work until midnight and were then driven back to Makow.

On September 7 the placards on the streets announced that the Jews no longer had any rights, they were forbidden to walk on the sidewalks, just on the streets, and not in groups, only separately. We were to take off our hats when encountering German soldiers, etc. It became clear that here and there Jews would be randomly seized and beaten for no reason, if only because they were walking in the streets. That said, in the beginning there were no horrific or mass acts of violence. It got to the point where merchants and store owners gradually began to re-open their stores and shops.

Several days later vehicles passed through the main streets announcing via loudspeakers that all Jews between the ages of 14 and 65 were to gather in the market square. Once they assembled, the new German mayor made the following announcement: “You no longer have any rights. From this day on you are subject to German authorities. You have an opportunity to depart now to the Russian zone and you can make arrangement to leave in that direction. The border is open and the Russians will take care of you.” Immediately thereafter several groups of Jews were given limited supplies and crossed the street. Those who opted out began walking in the direction of the Soviet border. There were those who made it there safely. Others encountered bands of thugs and were robbed but they pushed forward. The first stop along the way was the town of Lomzhe.

Those Jews who remained in Makow and had been taken in by Gentile families were ordered to abandon their houses, businesses and workshops and were displaced to the Jewish section.

[Page 312]

The Germans Begin Their Dirty Work

The Germans established an Agency for Jewish Affairs (precursor to the “Judenrat”) that was under Jewish management. Management was responsible for attending to displaced Jews and reported directly to the German authorities. There was a steady flow of Jews returning to Makow from the Russian front. There were also refugees who poured in from surrounding towns and villages. There were those who returned to quarters now occupied by the Germans and they had to be resettled. No one knew the revamped layout, which areas were “good”, which were “bad”, nor could former residents navigate for appropriate places to stay. Many wandered aimlessly through the streets, assuming they would eventually find some kind of shelter. But the Germans overran most of the city and the ominous sight of soldiers in every corner of the city made the situation worse.

In the meantime, the border between Russia and occupied Poland was hermetically sealed. The contact between those on the Russian side and the sectors under German control was completely broken off. The Jews felt surrounded by dangerous enemies on all sides without the possibility of moving safely in any direction. And then the Germans exposed their true character: kidnapping citizens for work details, beating, and muggings the local Jews, forcing them into near bondage at the Walter Kaiser company that built concrete pavements and roads. Former merchants, intellectuals, grandfathers, and children were forced into the lowliest and dirtiest forms of labor. After work they were subject to merciless beatings. That was the grim state of Jewish life in town.

In time the situation deteriorated from bad to worse. The Germans took to enforcing more sadistic and humiliating tasks. On Yom Kippur 1939, the German gendarmes removed Torah scrolls from synagogues, tore them to pieces, spread them out in the street, stomped on them, and continued to rip them to shreds. It's impossible to describe the pain and humiliation that the Jews felt watching this violation of holy objects as these events transpired. The new Beis-Midrash was completely destroyed. The Germans transformed the place to a stall for horses. At the same time the old Beis-Midrash was turned into a shelter for homeless refugees.

In November, 1939 a band of German soldiers captured a young Jewish girl and violated her. She was subsequently found collapsed and unconscious. The local Jewish pharmacist, well-known in town, recounted that he went to attend to her and gave her a prescription. The young lady took the medicine but later died. The Germans found out about the incident.

[Page 313]

They went to the pharmacist's house, seized him and his wife and tried them (in a makeshift court). They were later released thanks to the intervention of the head Polish pharmacist, Mr. Pizarski.

Fayvel Koval

There was a fellow named Fayvel Koval who lived in the village of Chociwel with his wife and two daughters. He had a Christian partner with whom he jointly owned a mill in the village of Dobzhankov. On 21 October he drove towards the Russian border and attempted to cross it. However, the German forces stopped him and ordered him to turn back.

In February 1940 the German gendarmes suddenly surrounded our house and inquired as to the whereabouts of Fayvel Koval and his wife from Chociwel.

Initially the Germans approached the Jewish Agency Command (Judenrat) in order to get the address of Fayvel Koval. At the time a senior head of the Jewish Agency Command was one Avraham-Michoel Adler also from Chociwel. He was also a refugee. As soon as the inquiry was made, Adler dispatched a messenger to our place to warn the Kovals that they were being pursued and that they should take off immediately. They did that. Shortly thereafter the Gendarmes burst into our house and started beating us mercilessly pressing us to divulge the Kovals' hide out. We didn't give it up. The Germans then took away the two Koval daughters, aged 18 and 20. Additionally, the Germans demanded a sizeable “contribution” from the Jewish Command. They warned that for each day that the Kovals failed to appear in front of the German authorities the Jewish Agency would be compelled to provide an increasingly higher “contribution”. The two daughters were in lock-up for two weeks. They were eventually released but were subject to constant surveillance. A month later the Germans threatened to hold the leaders of the Jewish Agency (Judenrat) hostage. But shortly thereafter the Germans located Koval and his wife in Chiechanow and placed them under arrest in the town of Wlozelavek. The daughters had an opportunity to glimpse at their parents through cracks in crates that impeded direct observation. The senior Kovals eventually disappeared. Apparently they had been murdered by the Germans. No one had any idea why the Kovals were so ardently pursued by the German authorities. However, it was known that Mr. Koval was well-connected in East Prussia. It was assumed that he was targeted by the Germans because of his valuable holdings in that area.

[Page 314]

The First Labor Camp

It was late 1940, or perhaps early in 1941 when the Germans began to dispatch young men to the first labor camp in the town of Gansevoh. Around 300 of us were loaded onto vehicles for the initial transport. As I said, this was the very first group of young men that was designated for displacement from Makow. They set us up in an abandoned schoolhouse and, consistent with Nazi protocols, they stuffed us in there well beyond the capacity of the building. The routine was stressful; up before dawn, roll-call, and off to work detail. The work itself involved digging up stones in the fields, and breaking them up for pavements and pathways. It was grueling labor. With minimal rations, the Polish guards pushed us mercilessly, prodding and beating us with wooden clubs, slugging us at will, and pushing us to the limit of endurance. We grew increasingly desperate. Most felt that this is where and how we would meet our end. Men would collapse and faint on the spot. This scenario played out for six months, until June, 1941.

One of the earliest victims in Makow was a Jew from Pultusk by the name of Velvel Skurka. He was sent to the work camp at Nova Wiej along with another group of prisoners. One of the camp guards, a “Volks-Deutsch” (Ethnic German), beat him so mercilessly that he was completely spent. The poor fellow screamed and pleaded “I beg you, please spare me, I'm a father of three young children”, but the brute beat him to death.

There was a Jew from Warsaw in the camp, his name was Mayorek I believe, who composed a song dedicated to the memory of Velvel Skurka. While I don't remember all the words to the song, two stanzas remain fixed in my memory:

In Nova Wiej, Nova Wiej,

That horrific camp,

A voice still echoes

From the deepest bowels.

It weeps, it shrieks,

Grief blows in the wind,

Velvel Skurka is beaten again,

The clock strikes 3, three more blows,

Velvel Skurka is the guard's victim yet again,

And he begs and pleads,

“Spare me, my life,

I have three little kids

And they need to be fed”

[Page 315]

Over time the local Jews were dispatched to labor camps in neighboring villages and towns occupied by the Germans. I was able to maintain contact with Makow. When one of our people fell sick we found ways to send him back to Makow for treatments.

However, as the occupation endured, conditions in Makow grew increasingly more difficult and dire. The local bath-house was turned into a jail, and many of the locals (Jews) were locked up and beaten randomly.

By June, 1941 entire families had vacated Makow, dispatched to work details in the town of Tchervonka. The young Poles were transferred to work assignments in Germany.

Wanted: Farm workers for Germany

One day while on a break from stone-splitting, the gendarmes encircled us and and gave the prisoners the once over, eye-balling each and every one of us. No one had any idea of what precipitated this sudden inspection. But everyone was scared: how was this inspection going to end? We all wondered.

The gendarmes finally selected two of us: Henech Lassek and me. They ordered us to leave the group and follow them directly. They led us to the command-center where we encountered several dozen horse-drawn wagons. The wagons were filled with groups of Poles (Gentiles) with their belongings; they were to be dispatched as farm workers to Germany. It turned out that two wealthy Poles had succeeded in buying their way out of this assignment and appropriate substitutes were needed directly. Apparently both Lassek and me conformed most closely to a “Gentile profile” so we were selected. When the wagons arrived in Makow, we were immediately recognized by several (Jewish) passersby. Not knowing what was going on, they immediately ran to Jewish Council headquarters (Judenrat) as well as to our homes to inform the locals that we were sighted in town.

The gendarmes took us to a makeshift hut which they had converted to a temporary jail. We stayed there for two days. The Council had us released and we were subsequently sent to Biedzitzeh, which turned out to be the harshest and most dangerous labor camp in the area.

[Page 316]

The Ghetto is Built

By Yom Kippur day, September, 1941, the Makow Ghetto was completed (the Judenraat had already been established by July, 1941). The Germans had already rounded up the Jews, settled them within the Ghetto confines, and had issued the yellow Star of David ID patch. The ghetto perimeters had been cordoned off: the southern border was the market; on the east, Grabova street; the northern edge was the Old Cemetery; and on the west Pruzhnetz Street. They packed in 2-3 families per room, which is to say that the entire Jewish population of 5000 was crammed into a space that amounted to no more than 20% of the area of Makow proper.

They clustered all the Jews in the ghetto, local residents and refugees, as well as stragglers who made their way to town from elsewhere. The ghetto was demarcated by barbed wire. Broken windows and boarded up openings over long stretches also marked the ghetto boundaries. The enclosed area was further offset by high walls ringed with barbed wire. The Germans issued a proclamation that any Jew found without the Yellow Patch (which had to be fastened and displayed on the front and shoulders of each Jew's garment) was to be shot. The economic situation in the Ghetto was dire. Bread rations were meager. We were able to make some adjustments, figuring out ways to smuggle in Kosher meat. However, the filth and sanitary conditions were deplorable to the point that there were frequent epidemics. By March of 1942 a severe epidemic of stomach-typhus broke out. Dozens of people died, a situation exacerbated by severe shortages of medicine and the absence of medical care. Once the epidemic became uncontrollable the Germans began to fear that the maladies would expand beyond the Ghetto walls. At one point they brought in a Jewish doctor from Warsaw along with his wife and child. The Germans issued an order that all men and women shave their heads. At the same time food was in short supply. People stood in lines for endless hours–officially from 3 pm to 8 am–with cups and containers to obtain their meager rations. It was not uncommon for people to wait in line overnight only to find that the rations had run out and that there was nothing left. The gates of the city were at southern margin of the ghetto, offset by the market on Rivneh Street. The gates were routinely patrolled and guarded by two Jewish policemen, but the German Commandant of Makow, Steinmetz, came by for spot inspections. He would appear without warning, escorted by two German gendarmes and the Jewish police. Often he would randomly stop Jews and beat them, eliciting perpetual fear and terror whenever he showed up.

[Page 317]

|

|

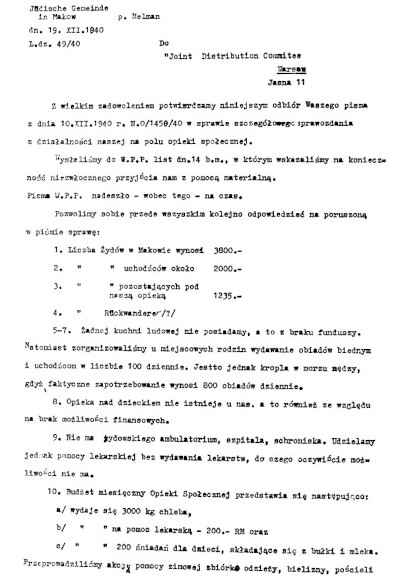

| Polish document: Jewish community of Makow (19.12.1940) to the Joint Distribution Committee, Warsaw 1940 |

[Page 318]

|

|

| Polish document (second page) signed by B. Ryzyka, A. Adler, Berenbaum, A. Faskowicz |

[Page 319]

Sadistic Entertainment

In May of 1942 100 young men were transported out of the Ghetto and taken to Ruzhan, about 20 kilometers away. About the same number were sent off to Karnievoh. The work camps there were among the cruelest and most debilitating. In Ruzhan the laborers were housed in what is best described as a fortress; they slaved away from dusk to dusk, and their labors were rewarded with beatings by wooden clubs and whips. The Germans did everything in their power to break the Jews' spirits, and to humiliate them to a state of despair. On Sundays the Commandant from Ruzhan camp would invite “guests” to celebrate these acts of hooliganism. They orchestrated “shows” for the honored “guests”. The camp Commandant would chase us down, and beat us as we ran while the guests clearly took pleasure in witnessing these spectacles. Every Sunday they selected 5 inmates from the worker details and they meted out 30 lashes on their bare bodies. The victims shrieked and screamed in pain as the Germans were overcome with perverse glee. We longed to get back to the Makow Ghetto, even though we knew that the epidemics were spreading and people were dropping dead from hunger there.

In Karnievoh, a village 8 kilometers from Makow, 30 young men were working in a field under the supervision of a German Commandant. Early one morning the Commandant suddenly appeared on horseback, stiff whip in hand, and began mercilessly flogging random laborers as he rode. And as this was going on the laborers continued to work.

Back in Makow social and community life had effectively ceased. An atmosphere of helplessness pervaded the town. No one thought about the Torah or anything when there was no flour, people were starving, running around in fear, and the spectre of imminent demise was persistent. Nevertheless, a group of 20 young and pious young men found shelter in an attic and managed to go on with Torah study.

The First Uprising

The following incident occurred in June, 1942:

There were three Jews from Pultusk, the first was named Skop, the second Rubin (I don't remember the third's name). They made it out of the Ghetto and wandered about the poor neighboring towns to procure food. Along the way they encountered a German officer approaching them on horseback. They immediately sensed an imminent confrontation with a probable negative outcome. They realized that it was useless to take off and instead chose to stop short ahead of the officer. Aware of both the futility of the situation as well as the immediate vulnerability of the soldier, they felt they had the upper hand and decided to take him on. They diverted the soldier and his horse to a side alley and threw him off his mount in front of the horse. He ended up lifeless, on the roadway.

[Page 320]

Just as the three felt that they were free and sufficiently removed from the scene of the incident, two soldiers mounted on horseback pulled up. The three Jews, sensing calamity, took off on foot as fast as they could. The soldiers drew their revolvers and began shooting in the direction of the escapees. Two of the guys fell dead immediately, but the third–Skop– survived but took a bullet in the neck. With his remaining strength he turned back and disappeared into the Makow Ghetto. Somehow he managed to find the local doctor who helped nurse him back to health.

The two gendarmes who had shot the two escapees dead hastened to report the incident to the Ghetto commissar. The commissar took off to the doctor's house to inquire whether he had just treated someone who had been recently wounded by gunfire. The doctor realized that he could not sidestep the incident. He confirmed that he had, indeed, attended to the wounds of a Ghetto resident and that his duty as a doctor mandated that he provide medical assistance.

Once the Germans extracted additional details on the incident they surrounded Skop's house and forced him out. Skop made an attempt to burst through the cordoned off area. His attempt was unsuccessful. The Germans seized him and drove him to a Christian cemetery in the nearby town of Shelkoveh where they shot him dead.

After Skop's death the Makower Jewish population assumed that the case was closed and resolved. As it turned out, the blood-thirsty German thugs continued in pursuit of additional victims. Several days later the Ghetto Commisar, accompanied by an SS detail, moved into the Makow Ghetto again. He brought with him a list of old, weak, and disabled Jews who had been excused from work details for health reasons. According to “orders” all names on the list were scheduled to appear. Once the first 20 names were announced the Commissar stated that no more individuals were needed. Subsequently the Commissar noted that those 20 were to be hanged in punishment for the gendarme that died in the ambush outside the Ghetto walls.

The 20 were locked in a cell at the Jewish Council headquarters. They remained under 24-hour watch by the Jewish police.

[Page 321]

In the meantime a stage was being outfitted, across from the Jewish Council building, as a gallows for the 20 selected Jews. They had a clear view of the construction activity from their holding cell, fully aware of the fate awaiting them outside. They were in a holding pattern for four months as the gallows were being built. On a bright September day, a large vehicle with a mounted loudspeaker drove through the ghetto announcing that all Ghetto residents–men, women, and children–were to appear at the plaza near the synagogue to witness the public hanging of the 20 Jews. The announcement specified that no children were to be left behind in their homes. Anyone who did not appear in the “Execution Plaza” would be shot on sight.

The Public Execution of the 20

The entire Ghetto was surrounded by German soldiers and gendarmes armed with automatic weapons. When the “Execution Plaza” had filled up with spectators a second announcement warned that no one was to speak and that any signs of disturbance would be met by a mass shooting. That morning the Jewish police were instructed on the procedures for making and fastening the nooses around the victims' necks and how to kick out the stools from under the victims' feet. Amongst the 20 sentenced for hanging were the two sons of Moishe Gogol, the brother of one of the Jewish policemen. The depressed and defeated crowd gazed at the scene, fighting back tears–in silence. The condemned 20, hands bound, were marched to the gallows.

|

|

| Corpses of the 21 murdered |

This tragic event broke the spirit of townsfolk. It was September, 1942.

In early October 1942 the German police arrested the Jewish doctor (who had assisted Skop) and marched him directly to the gallows at “Execution Plaza”, where the original hangings had taken place. The Germans issued the following accusation: “When Skop came to you to attend to his wounds, you did not inform the authorities, and on that basis you are sentenced to hang.”

On the day the hanging occurred, the doctor's wife went berserk. Subsequently she met her end in Auschwitz together with many more Makower Jews.

Later in October word got out that there would be an imminent evacuation. People would be moved out en masse but no one knew where or when. Folks wandered the Ghetto streets aimlessly, like the living dead, not knowing what was about to happen. The Judenrat itself had the feel of helplessness and despair, a holdover from the public execution of the 20 that only grew deeper as the days passed.

On November 1 the tragic news broke that the Makow Ghetto would be liquidated. Rumors began floating, about places like Auschwitz and Treblinka but no one really knew what any of that meant. Two days later it came out that older folks would be executed and that the younger people would be dispatched to work camps in Germany. But the details were not known at the time. Just rumors.

“Black Sabbath”

On November 5, an edict came down that the Jews from the surrounding towns like Ruzhan, Karnievoh, Nove Wiecz, Thchervanka, Bieddzhitza, and others would evacuate the labor-camps and return to the Ghetto. They came back that same day. On the one hand the news was joyous since families would be reunited and there would be no more indentured servitude in the labor camps. On the other hand there was a suspicion, bordering on fear, that the Jewish population would be re-interred in the Ghetto. Before evacuating the Germans allowed us to take not only the daily rations but also any bread that we may have otherwise stored. This gesture was also a source of suspicion.

We were escorted and marched back to the Ghetto by the German Commandant along with Polish guards. As we approached the Ghetto check-point we noticed that the entire place was surrounded by the German gendarmes.

[Page 323]

When we mentioned this to the locals they didn't believe us, since the gendarmes were apparently stationed exclusively outside the Ghetto walls; ironically we were the ones who brought the sad news for the residents on the inside.

When we got in we were met by sobbing relatives who told us that they (the Germans) were making preparations to take us to an unknown location.

I recall that it was a brisk fall day, a heavy rain came down, and the sky was overcast; the dreary weather was a reflection of our situation. Young people gathered in groups to discuss coping strategies and even potential escape plans. We were clearly locked into a dreadful and hostile situation. We found out that the local Poles, in the cities and towns, were warned by the German authorities that, going forward, if they were to hide or shelter Jews they would be hanged.

The day became known as “the Black Sabbath”, November 14, 1942.

That same day there was a selection. The Chief Ghetto Commandant, Steinmetz, along with several SS men, were stationed opposite the “Judenrat” building on the corner of the “Zhiloni Rinek”, the Market Square. Steinmetz ordered the Jews to appear directly in front of him. The Germans had prepared and handed him two separate lists. No one had any clue as to what these lists meant. The only thing we knew is that we needed to appear young and healthy. Those 16 years old and beyond were registered per family names. Those under 16 went with their parents. There were those who grouped themselves together on the spot “as families” in order to look young, fit, and presentable. The feeling was that these groups would be selected for the “young and fit list”, assuming the lists segregated the living from the dead. The registration/selection procedure took place all of Saturday and well into the night. When the process ended we all returned to our homes, not knowing what fate awaited us. People consoled themselves by saying “I'm pretty sure I looked healthy enough to be among the living…as for the others, heaven only knows!”

The next morning the official order came down to prepare for the evacuation. All money, gold items, and valuables were to be surrendered to the authorities. Most other items could accompany the individuals to the destination. The situation was such that folks hid, tore up, and even buried their cash and personal valuables. It was a scene that approximated absolute chaos.

[Page 324]

The Evacuation

The official edict came out on Monday morning, November 16, 1942. It stated that on Wednesday, November 18, at 6 AM the gate at the Pruzhnitz Road would be opened. Wagons would be there ready to transport the Jews to the town of Mlawa. Practically no one slept over the course of the next two nights, except for some individuals who managed to sneak out of the Ghetto.

Late Tuesday night, November 17, and into the next morning folks were busy packing their belongings. No one really knew what to take, some buried their valuables, others destroyed them completely.

By 5 AM residents had already abandoning their homes and began marching toward the gate at the Pruzhnitz road, which had basically been forced open by the Germans. We were informed that if anyone remained in a dwelling after 6 am they would be shot directly. Obviously, there were those too sick and disabled to leave; they stayed back, as there would be no one left to care for them. Rumors circulated that they were eventually killed off.

At the Pruzhnitz Road gate, the German gendarmes announced again that all cash, gold, and valuables were to be surrendered. On-site counters were set up for that purpose. The wagons were loaded up, two families to each horse-drawn wagon. The wagons themselves had been mobilized from Makow and the surrounding region. In all there were 5,150 people that made the trip including Makowers and Jews from the countryside and villages. The Germans packed the folks onto the wagons as quickly as possible, armed with clubs and prods. The wagons took off as soon as they were full. The people were so despondent and forlorn that there was not even a hint of resistance. Anywhere. Up until the last wagon took off isolated individuals, especially those who could not walk, were dragged out of their homes. That task was undertaken by the Jewish Police. And so the town of Makow became “Judenrein”, (Free of Jews). The entire Jewish population of the Ghetto, in excess of 5000 souls, was led out on their final journey.

The trip lasted the entire day and well into the night. It was around 7-8 PM, when the Ghetto evacuees arrived in Mlawa (about 50 km from Makow). The Mlawa Ghetto was empty, as the evacuation of that town had occurred several days earlier. The only Jews in Mlawa were holdovers from the Judenraat, the Jewish police, and their families. They served as the intake officials and designated temporary residence, one family per room, within the former Ghetto area.

[Page 325]

When we arrived we saw that the last (Jewish) residents had hurriedly abandoned their homes; we saw that household items remained in place, as they were left. There was uneaten foot on the tables, unmade beds and the like. When asked what happened to the Mlawa Jews, the Judenrat and police responded that they had no idea. One fellow retorted simply “Nothing good, that's for certain.”

We stayed in Mlawa several days. At night we would occasionally hear painful screams. We looked out the windows to see where they noise was coming from, as no one dared to venture outside. We witnessed the German gendarmes and the Jewish Police dragging individuals out of their homes. By morning the majority of the older remaining residents had been removed. From my quarters, I peered into an adjacent house and saw a couple bidding their last goodbyes to their three children, not knowing where they were going to end up. They put on their coats, held back tears, and then went off. The children effectively became orphans then and there. By the morning after, the Mlawa Ghetto was deserted. Word was that thousands had been transported to Treblinka.

Folks were led out and marched away as if to a funeral service. By then it was obvious that the Jews were heading towards their final resting places.

The Road to the Extermination Camp

This was the situation that the Makower Jews found themselves in. We remained in the Mlawa Ghetto for the next few days, until December 8, when the order was issued that the remaining residents, numbering around 4000, were to show up at the local mill site. The first transport included 1000 people. The second transport was scheduled to be dispatched on December, 10, this time numbering 2300. The third and final transport contained the last 700 individuals. The second transport also took in the Judenraat members and the Mlawa Jewish police. Once we saw that the officials were being transported it became clear that the entire town would be evacuated. The third transport of 700 included workers and skilled professionals that served the Germans in maintenance and technical capacities; they were moved out at the very last minute. The transports were organized by family, with each unit taking its possessions to the central dispatch quarters at the mill. People waited there through the night until 5 AM when the German gendarmes arrived and ordered that everyone assemble at the Central Ghetto Plaza to be dispatched to their destinations. At the Plaza we were instructed to break out in rows, 5 persons per row. Then it was announced that we were to march to the railway station from where we would be transported by train to specific labor camps.

[Page 326]

The Germans again ordered that we empty out our money, gold and valuables immediately. They laid out deposit boxes for these items. They followed up by saying “Where you are going there will be no need for any of these items.” I noticed that very few individuals offered up these items this time around. Next we were chained together, 5 people per row, and forced to run at a steady pace the entire 1.5 km distance to the train station. I supported my mother on one side, my father on the other, and my two sisters were alongside them as we made our way. We got to the ramp where there were “passenger” and freight cars. We were stuffed into these cars, prodded along by Germans with clubs who liberally beat us and ordered us to speed up the pace. People hustled to position themselves into the “passenger” cars since these had benches and space to breathe. In contrast, the freight cars were simply stuffed with as many people as possible and there was no room to move. Folks were simply piled one atop or adjacent to another like piles of firewood.

Those poor souls who did not have the strength to walk were simply dragged and pushed into the cars. When they were packed to bursting the Germans locked and sealed the doors from the outside. The cars began to move. At that point people started to wail and scream in desperation, cursing, and yelling, and then pushing and shoving and gasping for air. It was nearly impossible to breathe.

This was the situation for about three days. Through the windows we could see that we were passing through Warsaw. We stopped in Czestochowa for about a half hour. A Jewish workman, with a Magen Dovid (Star of David) around his wrist managed to bring us a cask of water. The train went past the city of Radom and approached Bieletz. It was around 6 PM on December 12 when we arrived in Birkenau. It was there that the German gendarmes transferred us directly to the SS authorities. They swung open the doors of the cars. They moved us out quickly, clubbing us indiscriminately, accompanied by dogs. These murderers yelled at us and beat us down to move quickly and evacuate the cars. As I descended from the “passenger cars” which I (fortunately) occupied with my family I saw how they beat those who vacated the freight cars. As the train doors flew open the scene was like a boiling pot with vapors and smoke streaming out. People were freed up after having been crushed and cramped from three days. It was like a block that decompressed and separated out; and then there were those who were dead and fainted lying still and trampled in the rush…. Despite that the SS men went about their business clubbing people and beating them as they made their way out, apparently relishing the scene that unfolded in front of them.

[Page 327]

The Selections

The dead, frail, and sick were grouped together, loaded onto freight trucks and driven away. The living remained on the ramps and platforms, beaten, screaming, and subject to selections. An SS officer stood by and pointed with his finger, to the right or to the left, determining who was to live and who was to die. Fathers were torn away from their children, wives from husbands, as separations were the objective. The same fate awaited my family. My father and I went off to one side, and my mother and her two sisters to the other. I saw them drag the women away. I cast a glance towards my mother and offered her a piece of bread. I told her, “We are men, after all, we will figure out a way to get by. But what about you?” An SS man beat me across the hand with a club, knocking the piece of bread to the ground. I retreated. Later my mother picked up the bread and ran towards me and my father, saying, “It's clear to us where we will wind up. Please take the bread. We won't need it anymore.” And those were the last words I heard my mother utter. I stared as her image faded farther and farther into the distance. I stood there frozen and holding back tears and emotions, as if my heart was being ripped out from my insides, disappearing, forever gone.

Out of the 2300 Jews from the second transport, the largest of the three, 524 men were removed. The rest–dead, sick, frail, wounded, as well as women and children and the old–they were directed to the other side by the SS officer on site. We saw the freight trucks heading towards us with steps leading up to the hold. They told the men to climb on. We saw the trucks driving up, one after the other. The men who could not make it on to the trucks were shot on the spot, their bodies loaded on to the trucks with the women and children. They told my group of five to climb into a truck. And the SS men drove us directly to the camp. And in the distance we saw the electrified barbed wire strung between the posts bordering the camp. It was still, quiet, like a cemetery. The hairs on my head stood up from fear. They drove us straight into the camp (it was 1 km distant from the train station). They jammed all 524 of us into a single barracks. They brought in a load of striped clothes. A manager along with an SS man greeted us with the following words: “You are now in the death camp known as Birkenau. You will work very long hours and have little to eat. And you will behave yourselves. You will be here three or four months, and if you can't hold up you will die.

[Page 328]

Should you have any money, gold, dollars, and any other valuables you shall surrender them directly. And now I should inform you not to inquire about your families because you will never see them again.”

Later that day the assistant to the manager gave out the assignments for the camp and work details. He said:

“No one can leave the barracks. That is where you sleep. Anyone who has to “attend to his (personal) needs” will go to one of two places in the barracks and will not come in contact with anyone else in the barracks or the second camp until the next morning.”

Those terrifying words, spoken in such basic and simple terms, allowed us to recognize exactly where we were and what to expect from this horrific place. We also learned precisely what fate awaited our families. We felt that sooner or later the same end game was in the cards for us.

Working in the Shadow of the Crematoria

The next morning we were assigned to another barracks. We were escorted by two block-captains and an SS man. They told us to strip down naked and leave everything in place. They shaved us clean of all head and body hair. Then they instructed us to rub some sort of fluid across our bodies that burned our flesh like fire. Next we took cold showers. Then they issued us the striped clothing–outerwear, long johns, and the striped pants, a jacket, a skull-cap of sorts, a pair of socks and wooden shoes. We were not permitted to measure the clothes for size, just to take whatever was issued. Eventually it got confusing as to who owned what. As for our previous belongings, we had no idea what happened to them. They remained where we left them.

The 524 members of our transport were then sub-divided into groups. One group was transferred to Buna and the A.G. Farben factory. The second, directly to Auschwitz. The third group was further sub-divided into two. One segment stayed in Birkenau and the second was led away by the “Sonderkommando”.

The camp was hemmed in by electrified barbed wire. There were guard posts every 10 meters. Alongside the barbed wire there were wide channels infilled with water, on the inside, where there was yet another barbed-wire barrier. The SS guards had a barracks at the camp gates and entryway.

[Page 329]

Birkenau occupied a setting that was underlain by a dense, clay-rich soil. Whoever stood on the surface after a strong rain felt as if he was sinking in mud. When you tried to extract your foot from the mud, the second foot got stuck behind you. Our food rations were as follows: bitter coffee in the morning, a liter of soup by mid-day, an occasional piece of meat, and for dinner a 250-gram ration of bread with a few grams of margarine.

Inmates awoke at 5 AM since roll-call was at 5:30 and the protocol lasted for an hour. During the count we stood out front for the duration in the cold and rain. Next the block commander along with SS men undertook yet another count-off. Once the counts were completed they divided us into work details and we headed out of the camp to our work stations. An orchestra was set up at the camp gates and played marching music. As we marched out each kapo reported the number of inmates in his group to the SS officers stationed at the gate. We shared the roadway with the truck transports that streamed in and out of the camp on their way to the crematoria. We were forced to stop in place intermittently to yield to the trucks bearing the bodies for the crematoria. The crematoria were outside the camp gates; it was an empty plaza manned by SS guards who oversaw the traffic and the workings of the operation.

Our work consisted of building barracks, digging holes and drainage basins, dragging stones, and moving heavy boulders from one location to another. The inmates worked in order to clear space for additional barracks to house future inmates or even themselves as the camp expanded. All of this work was under the direct supervision of the SS. The combination of minimal food rations, back-breaking work, and the stifling air replete with the stench of death, made it clear that we were not long for this world. My Makower brethren began to drop like flies–the victims of hunger, cold, and disease. My father and I were dispatched to Buna, a camp 10 km from Birkenau. The work there was even more oppressive. In addition to harder labor and reduced rations, we were mercilessly beaten and abused over the course of the work day. We were out in the cold barefoot and almost naked and my father got frostbite in his fingers and toes. He was taken to the infirmary. After that I turned completely despondent. I grew so weary that I could barely stand up. One day as I was walking towards the infirmary ital I caught a glimpse of my father. I approached him and passed him a piece of bread.

Sometime later there was a selection. I was led off to the crematorium. I was in a group with corpses, cripples, and sick inmates and they stuffed all of us together in vehicles headed to Birkenau.

[Page 330]

When we approached the camp the SS officer told the driver to “bypass the crematorium because a new transport has just arrived. Proceed directly through the camp gates” (this was in April, 1943). So we were back in Birkenau. Those who could walk exited the vehicle. They were told to line up in groups of 5. But I could no longer stand on my feet. By that point I had grown so indifferent and apathetic that I felt I could not get to the crematorium fast enough.

An Encounter with Hometown Friends

As we were lined up together, we noticed the inmates wandering about the work-camp grounds. One fellow approached our group, looked at us intently up and down, and then approached me directly and asked: “You wouldn't by chance go by the name Motl Tchikhanover, would you?” To which I responded in the affirmative. Since I had not seen the fellow in over five months, I did not recognize him. It was Noah Vitzoker. He was holding a tin of soup, and turned to me saying “Motl, I can't eat any more of this, I have dysentery, so please take this soup and finish it. Perhaps this bit of sustenance will save you.”

I took the soup from him, finished it, and licked the sides of the tin and felt somewhat revived. I could stand on my own two feet again. Noah Vitzoker stared at me with his sunken eyes and told me that there were still some surviving Makower Jews in the camp. Perhaps I would run into them and he would certainly spread the word that I was alive.

Immediately thereafter another Makower Jew approached me. He was holding almost an entire loaf of bread and said to me: “Here, take a chunk of this bread”. It was Dovid Wolfovitch. “Eat”, he said. I ate it lustily, tearing up as I consumed it. With each bite, I wept more, but this was the recipe for my body to revive and gain strength. I got the feeling that these two Makower Jews were my guardian angels and that God dispatched them my way to avoid death by starvation.

We stood around the cleared plaza several hours until an SS man ordered us to return to the barracks. And I met yet another Makower there–Hershl Karlinski, who was known as “the butler”. He offered up some more food saying

[Page 331]

“Here's hoping that you have the strength to survive because you are young and I will take it upon myself to help you in any way I can”. He went on to inform me that my mother's brother (uncle), Itcheh Segal, had been alive and well until a week ago, but then he suddenly passed.

Mass Transports

In April, 1943 mass transports from Greece began arriving. Two rabbis from Salonika were ushered into the camp in one of the groups. While they were deliberately segregated from us we were able to communicate with them through windows in the barracks. They were apparently forced to write back to Greece saying that while they were, in fact, stationed in a work camp, there was no shortage of food and drink and that they were treated quite well. Thanks, in part to these letters, the Greek Jews felt there was no need to oppose or organize against the transports. In reality, the Greek inmates suffered the worst treatments in the camps because the language barrier pre-empted communication with the Germans. They were given orders and specific tasks to fill and they did not know what was being asked of them. The Germans simply thought that the Greeks were resisting and were unusually non-compliant. And for that reason, they were beaten senseless, killed and sent directly to the crematoria.

It was around May of 1943 that transports began to arrive from Warsaw, shortly after the Ghetto uprising there. The recent arrivals mentioned that with their evacuation, Congress-Poland (the provincial population and administrative center) could now be declared “Judenrein” (or free of Jews). They also reported that Warsaw's “Umshlag Plaza”), or central dispatch center, was now the site of dozens of daily transports to Treblinka and Majdanek. During the months of June and July other towns and cities that transitioned to “Judenrein” included Bendin, Sosnowiec, and their surrounding metropolitan areas. The lone surviving ghetto was that of Lodz. All the while transports continued to arrive from places like Belgium, Holland, France, Latvia and Estonia. In general, families were slated for extermination, while the healthy males were selected out and brought into the work camps.

Henech Gromb

There was an incident involving a fellow named Henech Gromb. One clear day he simply disappeared. He succeeded in escaping from the camp along with his brother and three Soviet prisoners. Hundreds of SS men along with dogs and kapos were dispatched to hunt them down. In retribution, the SS forced the camp prisoners to stand in place without a break, while the search was in progress. In two or three days the escapees were caught and we witnessed their entry back to the camp. They barely resembled human beings: beaten to a pulp and bloodied beyond recognition.

[Page 332]

Henech Gromb himself took the blame for his younger brother, anticipating his fate (the brother was only 17 years old). About a week later Henech and the three Russians were brought out in front of all the camp prisoners. The four were led to a public space to be hanged. The younger Gromb remained in a holding cell and while he witnessed the tortuous and humiliating scene, he survived the war (he is currently living in Australia).

In December 1943 a transport from Therezenstadt arrived and the Jewish families were led directly to the camp. An SS man was brought in to serve as the block-officer for the latest arrivals. Amongst the newcomers he recognized a young woman with whom he was friendly during his school-days. One fine day he entered the camp decked out in his finest SS uniform, approached her and they ran off together. The authorities were alerted to the incident and pursued them but the two were never found.

The Endless Flare of the Crematoria

Over the course of a month there was a massive transport from Theresienstadt–men, women, and children. They were all exterminated. The barracks that housed them lay empty.

There was a barracks, near ours in Birkenau, that was populated by Gypsies. It was surrounded by electrified barbed wire. The Gypsy barracks included entire families. They appeared to have better food and were able to purchase foodstuffs somehow. The Gypsies remained in the camp for several months until one night several thousand families were led out of the 30 or so barracks that they had occupied; then they were exterminated. We saw endless clouds of smoke emanating from the four chimneys of the crematoria, that stood a half kilometer from the Birkenau camp. The crematoria ran all night, non-stop.

It was February and March, 1944 when the mass extermination of the Hungarian Jews took place. Transports came in daily and often the victims were marched directly to the gas-chambers. The crematoria ran in waves, but incessantly. The two facilities (gas chambers and crematoria) were adjacent to each other.

A camp known as “T” (letter “Tzaddik” in Yiddish/Hebrew) housed the Hungarian Jewish women and it was close to our camp. Every day when we took off for work we saw the women head out to their assignments as well. They wore pants and since their heads were shaven it was difficult to determine if they were men or women.

Block 7 (known as “the Seventh”), an infirmary, was subject to visits by the SS every second or third day. They would inspect the sick and remove the most dire cases directly to the crematoria.

[Page 333]

I myself suffered a bout of malaria. For three weeks I ran a high fever, afraid that I would be spotted and taken to Block 7, where the inevitable fate would be a trip to the crematorium.

The Lodz (Poland) Ghetto was liquidated in June, 1944. The last transport from that city arrived in our camp immediately thereafter.

The Rebellion

Birkenau had a Sonderkommando unit. The most able bodied, young men from Makow were forced into this unit and their assignment was to perform and maintain the incinerators in the crematoria after corpses were transferred there from the gas-chambers. After a 6 month term these commandos (consisting of 200 individuals per crematorium) were re-assigned to another camp where they were summarily executed to guarantee that there be no living witnesses to the horrific crimes that had been committed.

In July or August of 1944 word got out that the entire Sonderkommando unit was slated to be transferred to another camp (and to be exterminated).

At the same time the Sonderkommando personnel began to plot a rebellion in the death-camp. They decided that in the long run it was better to die with dignity–to quote the Bible “Better that my soul expire along with the Phillistines”.

Preparations for the sabotage was hatched secretly over time. It was devised in conjunction with members of the Resistance outside the camp. Co-ordination was implemented through civilians who worked inside the camp but lived on the outside. And they were well paid for their efforts. There was a young woman who was actually caught by the Germans smuggling out gunpowder from the ammunition factory. The powder ended up in our hands and we buried it beneath the block floor, where Tuvia Sehgal worked. Separate groups were able to bring in powder and other materials to build improvised explosive devices. When the time to strike came, each group was notified by a designated group leader. The specific hour for the rebellion was finalized once each group had made its way into the camp. A signal was given to begin the operation. As it turned out when “zero hour” approached the organizers called a last-minute halt to the operation. Tuvia Sehgal and some of the others in the Makower group did not receive the last minute cease and desist warning and they began the operations on their end. A huge explosion went off. One of the crematoria was blown up. Members of the Sonderkommando began to take off in several directions.

[Page 334]

One of the Makower group, Hershel Kurnik, ran right into the arms of an SS officer, grabbed his weapon and began firing randomly as he sprinted out of the camp. Tuvia Sehgal did the same as did Leibel Katz, Vladek Frenkel, Yisroel Lefkovitch, Moishe Fuchs, and other Makowers in the group. They assaulted the SS men directly. Several were killed in place while others were wounded. The uprising was ultimately deemed a failure. Viewed in context however, and given that millions were murdered in the long run, it was the Makower group that initiated one of the more memorable revolts against the German enemy.

The Germans issued an alarm once they realized what had happened. All inmates were instructed to stay in place and not move, under penalty of death. The SS men themselves began to panic and some took flight. For a brief period it seemed that the situation could spiral out of control. But the matters began to stabilize shortly after the initial shock. Within minutes hundreds of heavily armed SS appeared with dogs and surrounded the crematoria complex. All inmates, including the Sonderkommando and others were rounded up and driven. back to the barracks. The SS burst into the crematoria and opened fire on the Sonderkommando. Many were shot dead on the spot and those who had taken off were eventually hunted down and killed. Some escapees who had survived the shootings were brought back to the camp. The German high command issued an order to redistribute the inmates in the barracks, to minimize the possibility of a follow-up rebellion amongst the survivors. Of those who had escaped and re-captured none ultimately survived.

By September, 1944 evacuations of the Auschwitz-Birkeanau complex had begun. Outgoing transports were unscheduled and seemingly unplanned since the Russians had begun to close in. I was on one of the transports together with my compatriots, Shloime Reitchik from Makow and Yakov Frost from Pultusk. We were packed into freight cars, together with 30 or 40 inmates. The SS, armed with machine guns, were stationed in the last car of the train. No one had any idea as to where the train was going. When the train departed, around noon (September, 1944), one of the inmates approached me and said “We should be arriving in Radom, around 8 PM this evening. At that point we will assault the SS escort, grab their weapons and kill them.

[Page 335]

This action will occur simultaneously in each car. At that point we will all disperse and take off to the surrounding woods and countryside.”

Word of the planned action was apparently co-ordinated and spread across all the cars in the train. Each and every one of us was understandably apprehensive about the planned action. On the one hand, we considered that here it was, the end of 1944, we had already made it through Birkenau for two years, and just maybe liberation was a possibility. On the other hand we considered that perhaps this action itself was our best chance of actually surviving.

The Women End up in the Crematoria

The arrival time at Radom was overestimated and the train got in at around 7 PM. We had already decided which inmates would attack the SS men. But 30 minutes before “Zero Hour” the same fellow who informed me of the plan told me that the action was scuttled and that everyone should be informed immediately since we had just learned that our final destination had changed to the camp at Stuthoff. We got to Stuthoff (near Danzig) at 3 AM. We were there for about two weeks, during which time a major transport of women arrived. Peering through the barbed wires we saw that these women were marched directly to the extermination complex. It was October 1944. We saw that the doors to the gas-chambers had been locked and apparently the gassing was about to start, when an order was issued to cease the procedure and to march the women back to the camp. The doors to the gas chambers were opened and everyone was let out. At that point the SS men informed us directly that there would be no more executions by gassing. Subsequently, cremation became the disposal method for the dead, the shot, and the expired.

The Russians were closing in quickly and the Germans decided to evacuate Stuthoff as well. I together with my friends, Shloime Reitchik and Yakov Frost, were on a transport to Tubingen, close to the French border. We were taken to an airplane hangar. We joined another 500 or so individuals and were informed that this would be our accommodation while we worked in the new camp. We were led to our work stations by members of the German “Luftwaffe” (Air-force). Our work consisted of digging up huge unexploded bombs (ordnances) of American, British, and Russian origin. We loaded them onto freight trucks and they were driven away. We remained in Tubingen through December, 1944 and were transferred to a camp called Dortmeringen (near Stuttgart, Germany). There we were under Ukrainian supervision. The camp also had a significant contingent of Gypsies.

[Page 336]

While the food rations here were minimal, the work was relatively easy. As February drew to a close we were transferred to Bergen-Belsen. Our shoes had fallen apart by that time and we used rags to cover our feet. They loaded us up on freight cars for the trip. Many inmates simply expired on the trip out (my friends Shloime Reitchik and Yakov Frost stayed behind in Dortmeringen). We were assigned barracks in Bergen-Belsen. We were not assigned work details but there were no food rations either. Many more individuals expired that first night. Those who passed were removed from the barracks the next morning. We packed ourselves tightly in the barracks to keep warm. One night I literally slept on top of one of the prisoners just to keep from freezing. The next morning I realized that he was dead. They led away corpses in a procession of large-wheeled wagons, almost non-stop, directly to the crematoria.

We remained in Bergen-Belsen until April 15, 1945, the day that we were liberated by the British army.

Since my first day in captivity at Birkenau I formed a friendship with a fellow from Novidvor, near Baranovitch. His name was Leibl Chayat and he was 20 years old at the time. In Bergen-Belsen he approached me one day and said “Motl, help me, I have come down with dysentery.”

I responded “Look at me. I am practically dead myself. What can I do to help you?”

Leibl responded “There is a Norwegian doctor in this camp. He has a medicine that is effective for treating dysentery but he will only accept gold in payment. Listen to me Motl, we are on the verge of being liberated. Please help me.”

Now the camp was littered with corpses, in the back areas, that had not yet been removed or incinerated in the crematoria. I thought to myself: “I can survey the camp, search the corpses and perhaps I can come up with some gold. I could barely work my way through the mass of bodies, but I managed to extract some gold fillings from the teeth of victims. Whatever I got I took with me and ran straightaway to the Norwegian camp doctor. I pleaded with him to have mercy on my friend and to accept the gold that I had recovered. The doctor gave me the medicine. I took it and ran back to Leibl Chayat and gave it to him. He passed the next morning. I was completely shattered. It was a feeling of complete helplessness, followed by apathy and despair.

[Page 337]

I was 21 years old when we were liberated and weighed 30 kilos (66 pounds). I was told by an English doctor that were it not for liberation on that day (April 15, 1945) and had I not been treated immediately, I would have survived another two days at best. On Liberation Day we were completely dazed, forlorn, and hopeless. We could not even process what liberation meant.

On that same day, the SS men ran out of the camp. They passed on “authority” to the inmates.

The Liberation

Inside the camp we had been guarded by Hungarian soldiers, formerly partnered with the Germans. The British took over and kept watch on all four sides. They cut the barbed wire and burst through the camp in tanks. We hadn't eaten a thing in over two days.

The British brought in help and supplies directly. They drove across the camp-grounds in vehicles with loudspeakers announcing in seven languages “The Germans have lost the war. We are liberating you. Going forward you will receive everything you need. Please stay where you are.”

And the British kept their word. The next morning hundreds of Red Cross doctors entered the camp. Every survivor underwent an immediate medical examination. I was taken directly to hospital. I was there for 10 days and when I was sufficiently recovered I got up, left the hospital and began my search for family. My feeling was that maybe, just maybe, I might find someone that survived.

The number of dead, immediately after Liberation, was enormous. People even dropped dead during the act of eating. The British used bulldozers to empty the road and pathways of corpses. They attended to the sick who could not move, and fed the survivors as called for by their medical conditions. Life at Bergen-Belsen began to approximate a new “Normal” as a rehabilitation setting.

Over the course of my searches and wandering after leaving the camp I ended up in Munich (Germany). Once there I made inquiries as to where the Jews lived. I was directed to Don-Pedro Square. Once there I found out that many Jews were housed on the second floor of a building there and I encountered a young man from Czestochowa. He delivered the good news that my father was alive and living in Feldafing (DP camp). That next morning at 6 AM I hopped on the first train heading there.

[Page 338]

I was ecstatic that my father had survived and that I was indeed, not the lone survivor in this world and that I was on the verge of reuniting with my father. I was also hopeful that there might be other family members who made it through the war.

In the train car I met yet another Makower, Yitchak Itzkovitch, and he requested that I allow him to deliver the news that I survived to my father directly and in advance. When we arrived in Feldafing he ran to my father and informed him. Subsequently I got to my father's place and he recognized me immediately. We embraced and wept long and hard. And then I asked him: “What about mother and her sisters?” There was a long, protracted pause. I looked in my father's eyes and saw only tears, endless tears streaming down his face.

Ultimately, I made my way to Israel, under the auspices of the Jewish Brigade. I was active in the War of Independence, fighting for the establishment of our newly declared State.

by Shloime Raytchik / Natanya

Translated by Janie Respitz

When the war broke out in 1939 we left Makow and wandered until we arrived in Vengrov[Wegrow]. We had just managed to cross the Vishkov Bridge when the Germans began to bomb and destroy.

I escaped with my parents, sister and brother. There were already many refugees in Vengrov. It was difficult to get settled. We remained there until the Germans occupied Poland. Then we returned to Makow where we met the Germans. They had already taken over our house. It was the only house in town connected to the municipal sewer, there was a bathtub and other comforts. Clearly, the Germans took it right away. The house had two floors. They allowed us to live on the second floor. However it did not take long until the Germans removed us from there.

We moved to another apartment and tried to once again earn a living from the leather factory which we ran. Since the Germans had not yet taken it away form us, we removed the leather at night and finished the work at home in an attempt to make a living.

[Page 339]

|

|

| A Commemorative Gathering for the Martyrs, 1946 |

After a short time we received a list from city hall and the Gestapo with my father's name on it. My father hid and on that same night escaped to Russia. Other Jews whose names appeared on that list also escaped and they were not caught. One of the municipal employees, a Pole by the name of Piontek had warned us that they were coming for my father and that he should escape quickly.

10 Lashes for Gold and Jewelry

Knowing the Germans would steal everything we decided to hide gold, jewelry and other valuables. We dug a deep hole at night and placed everything there. Our neighbour, a Pole by the name of Pigelsky, who worked in our leather factory, apparently saw us digging at night. In the morning he came to us and demanded half of our possessions. If not, he threatened to inform the Germans. We did not believe that this Pole who had worked for us for years and received an honourable salary, would denounce us to the Gestapo.

[Page 340]

Therefore we did not hand over what he demanded, what we had worked for our whole lives. Pigelsky went to gendarmerie and informed them. A gang of Germans soon came to us and told us to dig up the gold and jewelry and I had to carry the tin box with our treasures to the command centre. When I handed everything over, as a thank you, I received 10 lashes from a braided whip.

Together with my mother, brother and sister, I remained in Makow. Just like all the other Jews they captured me and sent me to work. The work was not far from Makow. I worked there for three weeks and then returned to town.

While still in Makow we received a letter from relatives saying they were going to Trieste and from there to the Land of Israel. They said we should come and take some of their possessions they were leaving behind and perhaps we too will have the opportunity to emigrate.

My parents sent me to our relatives in Warsaw. I crossed the border illegally as a gentile. I arrived in Warsaw however the plan to travel to the Land of Israel came to nought as the road to Trieste was blocked and my relatives remained in Warsaw.

In Warsaw

At the beginning of 1940 there was not yet a ghetto in Warsaw. Since we owned a few buildings, I went to collect rent rom the neighbours. They informed me they were already paying rent to the German trustee.

While in Warsaw I made use of my time and went to a trade school to learn to be an electrician. There were many candidates but I passed the exam and was accepted. At the same time they began to build the walls of the ghetto. My father bribed a Polish guard at the gate and he allowed me to leave the ghetto. I arrived at the Danzig train station, took the train to Ciechanow, and from there travelled by wagon to Makow.

By this time Makow had changed completely. You did not see any Jews on the street. Jews had to walk on the left side of the highway and not on the sidewalks.

[Page 341]

This left a horrible impression on me. I felt dejected.

My uncle Raytchik and his partners Likhtenshteyn and Hertzberg had a mill. One of their employees, a Pole, later became the manager. His brother lived in our house and brought us flour, butter and other products, of course for an obscene amount of money. All the Jews were registered in the work bureau and had to work. My mother arranged for me to work for a German who came from Konigsberg and built a new house in Makow. I worked there installing the electricity. I had permission to come and go but since the house was outside the ghetto I had to stop working there and return to the ghetto.

As I mentioned, I had permission to leave the ghetto. This provided me the opportunity to get some food for me and my family.

I believe in was the eve of Yom Kippur when they locked the ghetto, you could not go in or out. The Germans announced we were to be evacuated. They no longer took anyone to work and the ghetto was hermetically sealed. The exits were guarded by Jewish police and the Germans.

Selection in Birkenau

The wagons arrived in November 1942. The Jews were ordered to climb in. They were pushed with sticks and were beaten mercilessly if they did not climb fast enough. They took us to Mlave where we remained for about three weeks. Then they took us to the train. I climbed aboard with my mother, sister and brother. They chased us into the train cars while beating our heads and faces and shoved us in. One of those helping to shove us into the train cars was the commander of the Jewish police in Mlave. When all the Jews were loaded in, the Germans shoved him in as well. He shouted to them: “You are throwing me in? I helped you with your work. I am the commander of the Jewish police in Mlave. We worked together”. They answered him in German: “Dirty Jew, get in there with the rest!”

[Page 342]

The night of December 12th 1942 we arrived at the ramp in Birkenau. The S.S man standing beside us gave an order: “Women and children to one side and all men over the age of 18, to the other side”.

Standing there I had the opportunity to speak to a German. He said to me: “you will be going to a work camp. You will be able to see your parents on Saturdays and holidays”.

They made us put down our bundles and line up. I saw how the German officer carried out the selection: to the right, the healthy, to the left the old and weak men. They sent me to the left. Since I saw the healthy men on the right, I ran, in the darkness and stood among those on the right. I went to the camp with them. This was the last time I saw my mother, my younger brother and older sister.

Hunger, Torture and Death

They took us to the bath, made us undress, took away our good shoes and clothes and gave us camp clothes: a shirt, a jacket, pants and a camp cap. We saw the Germans looking for good shoes.

|

|

| Beside the Old House of Study on the road to the cemetery |

[Page 343]

In the meantime I tore my bootleg so they would not take my boots away. There were French Jews working in the bath. One of them, Maurice, told me that among us there was someone who did really bad things and had been chief of the Jewish police in Mlave. Maurice beat him and warned him not to behave as he had in Mlave. We entered a half round fenced in barrack, 10 men to a bunk. The block elders were Jews. We were ordered to write letters to our old addresses and say we were healthy, feeling good and working. The police commander came into our Block. He was handed over to the Block leader. He received a beating every day and three days later he was suffocated.

Every morning, when it was still dark they woke us for roll call. We stood from 5 until 7 in the freezing cold and waited to be counted. Then we received some water – breakfast – in deep red bowls. I worked carrying bricks to build a building which turned out to be the crematorium. Anyone who ran away from work was liquidated. From hundreds, only dozens remained. People were broken and none other than the weak held out, in comparison to the heroes who fell like flies.

I decided to continue working as along as I could stand on my feet. I hoped that eventually I would be saved. In the evening after night roll call they distributed food: a quarter of a bread and a bit of soup which you could only receive with a beating so I never took any.

A Freezing Cold Bath, Naked

When I became sick with dysentery and had to use the toilet they did not let me go because anyone who was seen outside was shot. The Block elder said to me: “You are lucky, you are young, and that's why I'm not going to kill you”.

For six months I did not change my clothes and did not wash. My skin was covered with wounds. A while later they called all the young men, lined us up in a row for the commandant to do a selection. Together with others I was sent to Auschwitz, to Block 7/A. First I was quarantined, then they took us to the bath.

[Page 344]

We washed and were given striped clothes. It was the first time in 6 months I washed with warm water and changed from dirty to clean clothes. I went to a fenced in school where they taught us to build houses. The Block elder was a German sadist. Every night he would kill a few inmates. He was obsessed with cleanliness and said he would not tolerate anyone being dirty.

They made us wash completely naked, with cold water in frost and snow. He stood on the steps and watched. If one of the inmates did not wash and was not wet, he shot him. He would take men up to the attic, pour cold water on them and kept them there until they froze to death. He enjoyed giving beatings. If you shouted, you received 20 lashes. If you were quiet and withstood the pain you only received three lashes.

I was in Auschwitz for half a year and did not go through a selection. After we completed the building course they took us back to Birkenau, to a new place where they had built the men's camp in Block 21. I was sent to a building crew. I went out to work every day. I was an older inmate, I had many acquaintanceships, even in the “Sonderkommando”. (Prisoner work units).

There were many Jews from Makow in the “Sonderkommando”. They helped me a lot. We received from them gold teeth and gold dollars which we took with us to work and bought bread, cigarettes and alcohol. There were regular selections. I was lucky and was saved. I worked the entire time. We built a potato market and had friends in the “Canada Crew”. Boys from Makow whose work was, commanded by the Germans, to take away people's belongings when they arrived in a transport, brought us clothes, shoes and most important, food. Soon after we arrived we knew that women and children were immediately burned in pits since the crematoria had not yet been built as opposed to the gas chamber which already existed. They gassed the people then burned them in the pits. Often, when walking by we saw how they burned the people. Day and night we saw and smelled the smoke. The whole camp was black from smoke. If someone escaped we would have to stand for twenty four hours outside in the cold, without food or drink.

[Page 345]

When there was fog they would not take us to work out of fear that someone would escape. They guarded us with big wild dogs.

Early in the morning we would leave for work outside the camp, built the potato market and other buildings outside the camp and returned at night.

The Last Selection