|

|

|

[Page 366]

by Moshe Gildenman, of blessed memory

Translated by Pamela Russ

Instead of the Germans, the Bolsheviks Came

I will try to give a brief overview of the events of the period from September 17, 1939, to July 2, 1941. That is, until the day when Korets was occupied by the German army.

The war between Germany and Poland, which broke out on September 1, 1939, was already at an end in two weeks. The Hitlerite gangs, already on September 15, were near the River Bug. We were fearfully waiting for them to arrive in the next few days. Great was our surprise and joy when on September 17, the Red Army crossed over the Polish-Soviet border and captured Korets, then marched further west. The Korets Jews gradually got used to the new conditions that were created under the Soviet regime. The businesses, which were declassified under the new order, began to look for new sources of income. Some of the businessmen became officials, or employees in government projects, and the less intelligent and physically strong worked as ordinary workers on constructing the road from Kiev to Lemberg (Lvov), which the Soviet government had begun to build. Instead of private shops, government cooperatives were established, which were mainly run by former merchants. These cooperatives prospered well and they were more and more able to cover the needs of the population. The youth studied in the government public and vocational schools, and life gradually assumed normal forms. No persecutions in the religious area, as they

[Page 367]

had formerly frightened us, since this sort of thing happened in Soviet Russia, but the Korets Jews absolutely did not feel this now. This is how life was until June 22, 1941, when Germany entered the war with Russia. With the same speed with which the German armies conquered Poland, they now occupied one Ukrainian city after another and moved forward. Three days after the outbreak of the war, the Soviet officials in Korets received an order to evacuate. There soon came a panic. The Korets Jews, who were Soviet officials or employees, made arrangements for transport, and left the city together with the government officials. A large number of private Jews hired Christian drivers at great prices, and traveled with them. There were even those who went on foot to Zhvil. But many came back because of the overcrowded trains where they could not get into any of the cars. Some Jews were killed by the bombs which the Germans threw onto the railway station in Zhvil. In this way, up to 1,000 Jews were evacuated, the rest of about 4,000 Jews remained in Korets and waited with fear for the arrival of the German army. On June 29, the sound of artillery could already be heard in Korets. Parts of the Red Army already left Ostrog and Hoszcza and, crossing the Gorin River, hurriedly ran through Korets. By the 30th of June, there were already no signs of the Red Army in Korets, and only a few functionaries of the NKVD [Soviet secret police agency] kept order in the city. On July 1, there was already no governing power in Korets. Ukrainians roamed the streets, with satisfaction on their faces, waiting impatiently for their “liberator” – for Hitler.

In the First Days

July 2, 1941 - In the morning, a few individual mortar shots were heard and soon after a noise of engines and wild screams in the German language. Soon, the first Germans on motorcycles passed through the city, followed by infantry and later artillery. Jews were sitting in the houses behind locked doors and with

[Page 368]

fear, we waited for what was to come next. For three days, no Jew dared to go out into the streets. On July 5, I heard fierce knocking on the door: “Unlock the door, or we will break it down,” shouted an angry voice in the Ukrainian language. When I opened the door, a Ukrainian charged into the apartment accompanied by three Germans. “All the men come with us to work,” the Ukrainian ordered. Until my son and I were ready to go, the Ukrainian tried to open all the cupboards, the drawers of the tables, and whatever he liked, he took. When I asked him if we would be at work for a long time and if we should bring food with us, the Ukrainian answered: “All these years you drank our blood and viciously ate our meat. So now you can be a little hungry.”

We were taken to the “Ziemsko Bolnice” [Ziemun hospital], (near Volost), where we already met tens of other Jews, who were employed to clean the rooms and collect pillows and blankets from the neighboring Jewish houses, because in that hospital they were now arranging it as a military hospital. We worked until late in the evening. Before leaving to go home, the supervisor of the job gave us a note that we worked for the government, and explained to us that bread would only be given to the Jews who would present to the designated bakery a note that he worked for the government.

The normal amount was 250 grams a day for a working person. On the third morning, we heard screams coming from Yisrael Piternik's house, which was located opposite the hospital. And soon, two Germans brought Piternik's son-in-law, Yudke Koloverter (Yudke the goy [Christian]), to the yard of the hospital. They took him to the fence, which bordered between the hospital and the administrative area, gave him a shovel, and forced him to dig a pit. When the pit was finished, one of the Germans read the death sentence of “Jude,” [Jew] Yudke Chaimenis, where he was accused of stealing “military property,” which consisted of two sacks. Yudke's cries did not help, nor proof that he did not steal the sacks,

[Page 369]

but that Germans who were driving by had taken some new sacks from him and left behind these torn ones with swastikas. They shot him and then ordered us to bury him. This was the first beastly act of the Germans that I experienced, and which cast terror onto the Korets residents.

The “Jew Laws”

On July 18, 1945, large billboards were hung across the city, in German and Ukrainian, with the following details:

All of us felt the consequences of these orders. First, now all the Germans were able to recognize a Jewish house because of the Star of David, and were able to do anything he wanted with the residents and any of their possessions. The Ukrainian police, on the basis of the orders, using them as an excuse that they were looking for weapons, robbed the Jews and terrorized them. All the farmers who used to take some produce to the market, knowing that now the Jews had a very short time to do their purchasing, demanded extremely high prices for their merchandise. For a little bit of grain or beans they demanded that they be given a suit or a good dress. I will not forget that moment when, for the first time,

[Page 370]

I went out with the yellow patches. The Ukrainians whom we knew looked at us with make-believe compassion, and those who had more chutzpah, pointed at us with their finger and laughed. The Germans looked at us with superiority and contempt. It was very scary when a German walked behind you. You felt that he would soon take out his gun and would aim directly at the yellow patches on your shoulder. That patch stuck out visibly in a person's eyes, as if on a flag of a person's dark jacket. On the second day after responding to the orders of the local commandant, according to the recommendation of the Ukrainian council vote, a “Judenrat” [“Jewish Council”] was established, made up of the following: the Jewish elder – Moshe Krasnowstovske. Members were: Yosef Komenstein, Aharon Kiferband, Burke Goldberg, Yaakov Bruder, and Korostaszewski. The goal of the Judenrat was to place workers in government offices and to collect all kinds of household things from Jewish homes, clothing and linen, according to the demands of local commandant, district farmers, and Ukrainian police.

The Relations with the Ukrainians

Soon after the Germans took over Korets, a Ukrainian “Regional Committee” was set up. As head of this, there was the former teacher Rostikus. Within a few weeks, he did something wrong, so on the spot they elected the former writer from Wolosty – Flor Krizhanowski, and his son as general secretary. At the same time, they created the Ukrainian police, and all other government institutions. The Ukrainian intelligentsia, which was very active in the years 1918-1919 in the times of Petlura, went underground after the rise of the Polish government, and later, in 1939, when the Red Army took over Ukraine. They established various so-called culture organizations, such as “Prosvita” [enlightenment societies], “Ridnya Khata” [a cultural and educational society], and there they educated the youth in a nationalistic spirit, which was then anti-Semitic, and supported the hope and the dream for an independent Ukraine. Now, when Hitler took over western Ukraine, the Ukrainian traitors: Bandera,

[Page 371]

Melnikov, and others who collaborated with the occupiers, presented Hitler as their liberator, and as the one who would fulfill their dream. The entire intelligentsia was at their disposal. The youth, that was primarily sons of the wealthy farmers, greatly impressed the new government that promised not to create any kolkhozes [collective farms], nor to create Vilna Cossacks,” and permitted robbing and even killing the Jewish population. These circumstances created among the Ukrainians heated members and loyal servants of Hitler. During the first days, they positioned themselves at the head of all administrative offices and institutions. For instance, the medic Davidovitch became the boss of the “workman's bureau.” The second son became the head of the cooperative. Grobowski, son of Michalke Kupyetz, from the new city, became the boss of the police. His helper was Mitke Zaverukhe – a former baker. Valadika Dunayewski became the manager of the hospital. Pietro Korobko – of the Korets farmers, became the representative of the “golowa” [commander of a military unit] from the regional administration. These Ukrainians literally crawled under your skin in order to satisfy their German bosses. They were the directors and inspirators, in leading the Korets Jews through their lives' tragedies. Being absolute anti-communists, they combined the Jew and communist, and helped eradicate these two elements from their roots. For example, on July 20, the Ukrainians informed on the Polak Ostrowski, to the Germans, who was a worker in the sugar factory, and on the Ukrainian Skubik, and on two Jewish girls: Henya Galtzman and Chaike Berenboim, saying that they were communists. The Germans led them out to the Russian cemetery and shot them. About this portion of the story, I will describe more details in later chapters.

[Page 372]

The First Murders

On August 1, 1941, an elegant car came to Meir Gurwitz's house. Two German officers came out of the car, accompanied by a Ukrainian. They went to the dentist, Shlugleit, who lived on the bottom floor. The Germans spent a few minutes in that house, and then they left. When Shlugleit's children came home after they finished work, they found a horrific scene: Their father lay on the ground, a dead man, in a pool of blood, and their mother was sitting on a chair, shot, and the grandmother was laying dead, under the bed. In the middle of the light of day, the murder of three people had taken place.

On August 8, 1941, they brought to the Judenrat [Jewish council] a list of names of 120 Jews who were being called up for work by the military policemen, and who have to be present at 10 in the morning at the house of Babushkevitch, where the police were located. My son and I were on that list. We were already there before 10 o'clock. They wrote down our names, first names, trade, and other details. Only the following eight men were marked as necessary tradesmen: myself as a concrete maker, my son as an electrician (at that time we both worked as repairmen for the post office building); Yosef Wachbroit the shoemaker, (Zagotowszczyk), who made shoes on order of the local commander; Yosef Bartman, a military tailor; Avraham Bardakh (the son of Yitzchak Chaim-Yonah), who baked bread for the military; the brothers Moshe and Hershel Wylienczyk (the Binems), who as carpenters, rebuilt a Ukrainian shul; and the old Sorin, who used to work in a sugar factory. The rest of the 112 Jews were taken by cargo trucks in the direction of Zhvill, and every detail about them has disappeared. After the war, in the year 1945, with the appearance of a farmer, their graves were found in a field near the town of Pulczyn. This farmer had seen how they brought the Jews to the field, how they were forced to dig up a ditch, how they were forced to get into the ditch, and then they were all shot. Among the 112 Jews, were also the members of the Judenrat Burke Goldberg and Ahare'le Kiferband.

[Page 373]

On August 20, on the day of the Christian holiday of preczysta [the birth of Virgin Mary], a large unit of Gestapo men came to Korets, and went into the streets to grab up Jews – only men. These men were loaded onto closed cargo trucks and were taken to Zhitomir where the Ukrainian headman of the regional administration confirmed it. That day, 350 Jews were taken, and as was later revealed, they were shot in the same field as those who were killed on August 8. That same time, the member of the Judenrat, Yosel Kemenshtein, was also killed. Of the three members of the Judenrat who died in the two aktzias, in their place were: Leizer Globerman, Yoel'ik Maliar, and myself.

Contributions and Robbery

On August 25, the regional commissioner of Rowno, Dr. Bayer, came to Korets and demanded twelve “hostages,” among whom I was also one. It was 9 o'clock in the morning. He gave an order that by twelve o'clock they should have ready for him a contribution in the amount of more than 100,000 German Marks, some Persian sofas, silver tableware, and other desirables. If this would not provided by the appointed time, then the twelve hostages would be shot and the rest of the Jews would be locked into a sealed ghetto. According to the conditions of the time, this was an unusually high amount, and yet it was amassed and given over at the designated time, and the hostages were released. Apart from the one-time contribution, not a day passed that the Judenrat did not make any demands on various things that the Germans and the Ukrainian authorities demanded. In particular, the regional agricultural first-lieutenant Penzel made himself famous with this. This German, to whose credit it must be said that he hated the Ukrainians as much as he hated the Jews, and could not get enough of the Jewish loot. Every day he gave orders demanding other things, which he sent to Germany. At the time when the material situation of the Jews was getting worse every day, his demands for these things each time became greater and more expensive.

[Page 374]

|

|

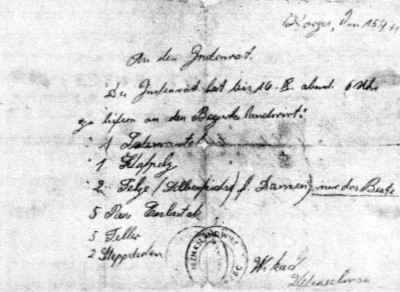

| The order of the agriculture commissioner to the Judenrat for a woman's silver fox coat |

He accompanied every order with threats that he would enact reprisals against the Jews. The regional landowner was the actual owner of the city, and the regional administration and the labor office were subordinate to him. He was able to transfer the Jews to other landowners in the surrounding towns and even hand them over to the Gestapo. These orders created much grief for the Korets Jews.

Once, he ordered from the Judenrat (I am placing here a photocopy of the order): a leather coat, a sheepskin coat, bed linen, and two silver fox skins for ladies. The entire order was put together, but silver fox skins were impossible to get. Not only did the Jews not have such things, but even Christians, from whom the Judenrat wanted to buy, were also unable to provide such things. The regional landowner became very angry at the Judenrat, and locked up me and Moshe Krasnostawski in a cellar, and stated that if the silver fox skins were not there by 10 o'clock the following morning, he would shoot us.

[Page 375]

After much pleading, he was able to be convinced to take ten pairs of chrome leather boots instead of the two silver fox skins.

Every time, either when there was a military unit, or if a German official stopped in Korets to spend the night, the Jews had to provide sheets, pillows, and blankets, which, soon after their departure, were stolen by the Ukrainian policemen, or by the Christian owners of the houses where the Germans slept. Apart from the official requisitions, the passing Germans used to break into the Jewish houses and steal whatever they wanted. A short time before the liquidation of the ghetto, the Germans gave an order to bring to the Judenrat all the brass and copper that the Jews owned. In addition to the brass candelabra, mortars, copper pans, and the menorahs from the shuls, they were forced to tear off even the brass doorknobs and handles from the doors and windows. The Jews gave everything that was demanded, thinking that this way they would placate the murderers and avoid new decrees.

Jews are Working

Every Jew, both men and women, tried to organize for themselves a stable workplace. There were many reasons for this: Firstly, because only on the basis of the labor certificates could one get the 250 grams of bread a day. Later, the ration was reduced to 130 grams. Secondly, every Jew thought that during the destructive aktzia or deportation to work in another city, from which, by the way, no one had ever returned, the employers would protect them. As the course of the subsequent events showed, this notion was completely false. During the first massacre, the employers not only did not protect them, but handed them over into the hands of the murderers. Thirdly, it was much more unsafe to be at home than to be at work, because all day long the Germans of the local command and the Ukrainian police used to snatch up the free Jews for random work, for which they were not sure about their lives.

The Jews worked in the following regular workplaces:

[Page 376]

In the sugar factor, which was partially destroyed during the war, and which the Germans prepared as the sugar company, six to seven hundred Jews worked. Mostly in hard physical work, which the Ukrainians, who had been doing this work for years, now did not want to do it. Every regular Ukrainian worker, who worked in the sugar factory before the occupation, during the transition period, when the Bolsheviks left Korets and the Germans had not yet occupied it, managed to steal large quantities of sugar, which they were now selling for inflated costs in the neighboring towns. This gave them such a large income that they no longer needed the minimal monies that the Germans were paying. On the other hand, the Jews, who were impoverished, needed this salary. Every Jew tried to get a job in the sugar factory for those reasons, also due to the fact that the administration of the factory was mostly made up of Poles, the same ones who were still there when the factory belonged to Count Pototski, who were very humane and kind, and treated the persecuted Jews with great compassion. These Poles, especially the brothers Tarnopolski, Monczinski, and Sultan, worked out with the Ukrainian director Logvinyenka (a Ukrainian from western Galicia, a Hitlerite and great anti-Semite), that instead of the two marks a day the Jews should better be paid with “malias” [lesser prices, insignificant monies] according to the royal price. The Jews used this small amount of change instead of sugar, which they sold to the farmers who used it to make brandy. The Jews worked in brigades under the supervision of a Ukrainian. The work was difficult, because it took place in the street in the fall, often under a downpour of rain. According to the director's order, the Jews were not allowed into the factory building. Regardless of the difficult conditions, the Jews considered it a blessing when they got a permanent job in the sugar factory.

Up to a hundred Jews worked in outlying areas of the “TOT” organization. This was a technical organization, which repaired roads and built various tools from wood for the army.

[Page 377]

The majority of workers there were craftsmen. The treatment there was quite good, and Jews gladly worked there.

At the beginning of spring, the Germans started building a soldier's home (a barrack). For that task, they chose the building of the vintners on the market and thoroughly reworked it. Several hundred Jewish workers, including women and young children, were employed there. The work there was not difficult, and the supervisor was very friendly towards the Jews. There was a German from Alsace-Lorraine by the name of Robert. He trusted some Jews, was an engineer by profession, and was demoted from being an officer to an ordinary soldier for his political beliefs. During the first aktzia, he hid some Jews in his house, and he took many Jews from the place of assembly [scene of the attack] as tradesmen, without whom he could not finish building the barracks. Other than the three above-mentioned stable workplaces, where larger groups of Jews were employed, there was also so-called seasonal work. For example, during harvest time Jews did fieldwork on farms in Golownice and in Pulczyn, and in collective farms in Derazhne. Even though it was difficult to walk five to six kilometers to work and back every day, the worker was allowed to take fruits and vegetables with him, of which there was a shortage.

In August 1941, many Jews were working at the “kabel,” that was the name given to the work of laying an underground cable, which stretched from Hitler's headquarters to the first front line. This was one of the hardest and most unpleasant jobs that I had the chance to do during the entire time of the occupation. The cable stretched along the side of the highway. In the hard city ground, we had to dig a narrow, but very deep pit and lay a cable in the pit. The cable was the thickness of two fists, and we had to tie it like a “string,” as the supervisor demanded. The German supervisors of the work walked around with thick sticks in their hands, and for every “sin,” beat the person with deathly pounding. The most difficult phase of the work was when the canals had already been dug out and we had to start laying down the cable. We stood in the deep,

[Page 378]

uncomfortable pits, and carried the heavy cables on our backs, and the Germans stood up on top and watched very closely to make sure that “the Jews should not cheat.” That means, that everyone should pull properly. When they noticed that someone's back was lower than the cable, they beat him with their sticks. Each day, there were badly wounded people at this job.

I will now describe one incident that I experienced and which showed me how our lives were so wild. While working with the cable, there was a Jew working for me, he was from Kilikiev (10 kilometers from Korets). The Germans did not allow the Jews from one town to go to another town. When a new Jew came, he had to be taken to the local commander. A few Jews from those cities that were located in the former Soviet territory, from where the Germans liquidated the Jews when they took over, tried to save themselves and then came to Korets. For a long time we hid them on the rooftops of the shuls, and in the cellars of destroyed homes. In order to legalize them, we began to take them along with us to work, and as a result of those appearances and permits that they received every day, they were able to receive bread, and with the help of the Judenrat, they were brought to the workman's bureau on the list of names of Jewish workers, and that is how they automatically became Korets residents. The Kilikiev Jew, who worked for me, spent a few weeks hiding in the fields between the corn stalks. He was so exhausted that he could hardly stand on his feet. With the last of his strength, he dragged the cable and I saw that in a few minutes he would fall from weakness, and then the supervisor would kill him. The first one of the Kilikiev Jews, Moshe the blind one (Moshe Mieshok - the painter), was a healthy young man. I talked with Moshe and we decided to make an effort and pull the cable in such a way that the weight that fell on that Jew should be lifted onto us, and that Jew should follow us and pretend to be working. That way, he would rest a little, and get some new energy. That is what we did. But the German supervisor, however, saw all this, that the Jew was not pulling. Then, as a bird of prey, who attacks its victim,

[Page 379]

he ran over to that Jew, and with two fiery smashes on his head with a heavy stick, the Jew fell dead to the ground. The murderer looked at his hand watch and strictly ordered that in one minute we should throw out this Jewish filth from the ditch, and then resume the work. For that entire day, the Jew with the head split open and with the yellow patch on his chest lay on the road on which, all day, without stop, German officers and officials passed through. No one even glanced on the body of the dead Jew, who was lying there with his bloodied face looking upwards. Some even looked with a satisfied glance at the “Jude,” and then merely continued on their way. Later in the evening, when we finished working, we carried him away and buried him in the cemetery. This incident showed us that a Jewish life, just as Jewish possessions, was ownerless, and everyone could do anything to us at all, being totally unpunished.

Every Ukrainian police or official had a young man or a young Jewish girl as a housekeeper, who did the filthiest work, and was the servant. The older Jewish men and women, who were not capable of doing difficult work, but needed to get bread vouchers, were given the job of “cleaning the streets.” You could see them for full days with brooms in hand as they swept the highway from the “cracker factory” to the “single hairs.” For a Christian holiday, they were forced to sweep the non-Jewish streets and then carry out the garbage in sacks to the garbage cans that they had put on the Jewish streets.

Other than the usual humiliations, there were often opportunities for the German rulers and their Ukrainian helpers to perform other sadistic behaviors. Once, a German soldier of the regional command, assembled three elderly Jews with grey beards. These were Nute Marcus, Yeshiye Simcha Tzalyes, and a teacher from behind the mills, Yisrolik, the younger brother of the cabinetmaker. He harnessed these three Jews to a wagon, in which there was also a huge barrel, and he himself got into the wagon as well. He began to beat the Jews with a long stick, and forced them to drag the wagon across the whole city to the river

[Page 380]

in order to get water, to the great pleasure of the passing Germans and Ukrainians.

A group of Jews, under the guard of some Ukrainian policemen, went to work in the field in Pulczyn. They stopped for a few minutes near the regional commanding office, which was in the building of the former post office, and waited for a soldier who was to accompany them to work to protect them from the passing Germans. From the commander's window, one of the officials was looking out and saw a group of Jews, and he was now eager to make some trouble for them. He screamed that the Jews should uncover their heads, because it was forbidden for Jews who were standing near the commander to have their heads covered. The Ukrainian policemen understood these words of the German as a “law,” and from that point on, they forced the Jews to remove their hats when they were near the commander, the field gendarmes, and the home of the regional landowner. Later, they extended this “law” even more so, and forced the Jews to remove their hats when they passed by any German or Ukrainian police. It was particularly uncomfortable and even painful for the Jewish workers to carry out these orders, since they worked in the sugar factory, and in the winter, with the frost and storms, they had to have their heads uncovered when they left work, which was at the edge of the city, and stay that way until they got home, because that road crossed the main street, where you met a German or Ukrainian police every other step of the way.

That's what the life of Korets Jews looked like in the first months of the German occupation. They worked hard, were not properly fed, because with 130 grams of bread a day they could not satisfy the hunger. So, they exchanged clothing with the farmers for a little flour or potatoes. The worst was the suffering of the cold in the winter. The winter of 1941-42 was very hard, snowing without stop, and the cold reached 30 degrees. Then, other than the regular workload, there was now “extra” work of cleaning the snow off the roads and helping to dig out the German transports that were stuck in the snow. At that same time, there was an order that the Jews must give all their fur clothing and even fur collars to the regional landowners, for them to send to the soldiers on the front lines.

[Page 381]

Wearing light clothing and shoes, the Jews had to work on the roads, and when they came home, they entered cold, not warmed houses. The issue of not having wood was the sharpest issue that winter, since not every Jew had a stored supply. Farmers from the surrounding areas would very willingly have brought wood for the Jews, receiving for that either a whole or half golden coin, but they were afraid to do that because the police had requisitioned the wood and those who would bring it would get murderously beaten. When the Jews left their work, they carried some twigs home with themselves, or dried branches which they had collected on the roads on their way home. They heated the homes with household utensils, with furniture, and even boards from the floors. Towards the end of the winter, the situation led to neighbors all gathering together in one house, then demolishing the second house and using that as wood for burning. That's how they lived until the eve of Shavuos 1942.

The Horrific Erev [eve of] Shavuos, Year 5702 (1942)

In the first days of May 1942, rumors spread that the Germans had mobilized farmers from the villages: Kozak, Halyczewka, and Morozovka, and they were ordered to dig up three ditches, 20 meters wide and 3 meters deep. The ditches were dug up in a small forest near the village of Kozak. A terrible fear befell the Korets Jews from this news, because at the same time, the Ukrainians, who were in the government, secretly revealed to the Jews that the Germans were preparing to liquidate the Korets Jews and the ditches were being dug for that reason. The German manager of the workplace, to whom the Jews went with questions about whether these rumors about liquidating the Jews were true, comforted and reassured them that the ditches were being dug to get sand for repaving the roads. The ditches were ready on May 10. Ten days passed, and the Germans did not implement their bestial plan. Everything went in the usual way. The Jews worked as usual, and even somewhat calmed down. They began to prepare for the holiday of Shavuos. Everyone tried to exchange some white flour with the farmers, and arrange with the German work bosses for permission

[Page 382]

not to work on that day. On the night of Wednesday before Thursday May 21, the eve of Shavuos, the city became surrounded by strong units of Ukrainian police. At 4 am, the murderers invaded the Jewish homes, and herded the Jews together: old and young, men and women, and chased them to the regional administration which was on Staromonastirska Street in the house of Dovid Feldman. At 6 am, they ripped open the door of my house, and soon all the rooms were filled with armed Germans and Ukrainian police. “All Jews to the special registration!” This was a stark command, and they immediately surrounded us and led us out of the house.

“Do I have to take my personal identification card?” I asked one of the Ukrainians.

“You just have to take your head,” he answered me, and the rest of them burst out laughing.

On the way, we met other groups of Jews, which the Ukrainians were directing. Some were bloodied. Shots were heard from all sides and terrified screams. When we went past the house of Shmulik Viernik, we found a mass of blood, the murdered daughter of Dr. Shlugleit. Ukrainian men and women were roaming the streets like hungry vultures, most of them from the new city, with sacks in their hands. They followed us with shameless, satisfied looks, and eagerly went into the Jewish homes for looting. When we were taken near the house of Mottel Vichnes, an old female farmer came out of there with a heavy sack on her shoulders, under which she actually collapsed. In the alleyway that led from the monastery Street to Esther Chaya Dovid's street, many women and children were standing, surrounded by policemen, and crying uncontrollably. Near the regional administration, there were many Jews standing there with frightened faces, some only in their underwear, waiting in a row. Among them, there were Gestapo men walking around in their blue uniforms and the policemen in black cloaks with black helmets on their heads. Like wild animals, they threw themselves at the Jews every now and then.

[Page 383]

Periodically, a loud bang was heard, or the sound of a pistol, accompanied by a cry from the wounded victim. From all the surrounding streets, murderers always brought new Jewish families. They took us into the district administration, where they carefully searched and took everything we had with us, even a pencil or a box of matches, and when they took us out of there, they took my wife and my 13-year-old little girl to the women separately, and me and my son to the group of men who were standing near the house of Michel the butcher. Here, groups of 40-50 men were formed and taken away under strong guard by the Germans and Ukrainians in the direction of the old monastery. My son and I were already standing in line and waited for a few dozen more Jews to form a new group. Suddenly, the leader of the work at the “canteen” came to us, the German Robert, whom I mentioned earlier, and began to negotiate with the head of the Gestapo to release his workers. He argued that he would not be able complete the work without them. After a long discussion, he managed to get 20 men, including my son, who worked as an electrician. These Jews were told to sit down on the ground, in the free space between Michel the butcher and Chaim Monaker's houses. Pointing to me, my son begged Robert to free me as well, even though I was working in the sugar factory. The Gestapo foreman thought about this for a long time, and at the end, he allowed me to leave the group, which had already begun to leave. We were ordered to sit on the ground with our feet under us, and sit like that without movement. Gestapo men were standing around us, on guard. In the meantime, some more carpenters were released, as well as other workers who worked in the organization called “TODT” [civil and military engineering organization]. The district commander took out tailors who sewed for the military. Like that, 135 men were released from our group. After that, 65 young, healthy women came to us, whom the Germans left as domestic workers at government institutions. From then on, fewer and fewer Jews were brought to the regional

[Page 384]

administration. At about 12 o'clock, they started to drive away the sick and wounded Jews. Some of them were carried by policemen in their arms and were dragged like sacks to one place opposite the Berezen cloister. I will not forget the picture of when they brought over Eliezer Zafran, who was paralyzed. A policeman dragged him by the feet, and his head hit the stones of street. In addition to Zafran, they also brought Meir Gorban -the broker – and Pesach, the musician's son-in-law. A few days before that, he was run over by a German motorcycle and was laid up with a broken leg. These unfortunates were lying on the ground and were waiting for the car that was supposed to take them to the graves. Finally, a closed red car arrived, the “dashegubke” [gas chamber]. This was a special, hermetically sealed car, which was arranged in such a way that the burned gas from the engine went into the car through a special pipe, and by the time that the car arrived at its destination, those passengers who were inside suffocated. They began to slide the sick ones into the car. At that moment, they brought in Dr. Yanye Hershenhorn, Meir'el the teacher, Buzhe Krantzberg, and Yosel Shicher - the youngest son of Leizer the painter. When the last ones were about to be placed into the “dashegubka,” a delegation of Christian workers from the sugar factory arrived and began to beg the Gestapo commander to release Dr. Hershenhorn. They declared that he was the only good doctor in the city and was the long-time factory doctor, without whom they could not keep going. The supervisor told him to stay temporarily until he would come to an understanding with the director of the factory. At the same time, an official of the regional headquarters was using Shicher, who worked as a painter, and had to finish painting signs for the commandant. Dr. Hershenhorn and Shicher were told to wait. When all the sick were already loaded onto the car, the Germans grabbed up the doctor and Shicher and, ignoring their complaints, pushed them into the car, locked the door, and took them away. We sat motionless and waited. Our destiny had not yet been decided

[Page 385]

and what would happen to the Jews who were taken away was also unknown to us. Suddenly we heard the screams of a woman and an unnatural, insane laughter, and soon we saw that a policeman was taking Laike Shapira, the daughter of Rechel the crazy woman, to the regional administration office. As was known, the family of the dayan Chaim Rav Hertz, was psychologically unwell, and this illness was passed on as inheritance to the generations. In the last few years, Laike was normal. She even married and had a child, but at the time of the aktzia, she had another panic attack. Each time, she tore out of the hands of the policemen, as he murderously beat her after capturing her. Not far from the entrance to the regional administration, there was a telegraph pole. Laike grabbed it with both hands, and began to dance around it. When the policeman who had grabbed her got close to her, she began to scream: “Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler!” and then laughed hysterically. Some Germans came over to the place where Laike was standing and with smiles on their faces they watched this unfortunate person. When she saw the Germans she suddenly stopped laughing and began to sing the “Internazionale” [communist anthem]. One of the Germans grabbed out his pistol and with two shots he ended Laike's suffering. At around two o'clock, a whole transport of farmers' trucks rode past the regional administration, loaded with all kinds of materials, as it appeared to us from a distance. The Germans, who were escorting the transport, ordered that some of the younger Jews from our group were to go and unload the wagons. My son was also among them. From a distance, my son showed me my daughter's small green jacket that she wore when she was taken away with her mother to the women's group. When those who were unloading the wagons described to us the horrific scenes that the farmers, who brought the clothing, witnessed at the execution place, our blood froze in the veins, and only then did we understand the total horror of those events.

[Page 386]

At the Ditches[2]

On the terrible Thursday, Erev Shavuos, at four a.m., the head of the Gestapo, accompanied by a strong detachment of German and Ukrainian police, went to Liesnicz's home in the early hours of the morning and ordered Liesnicz and his wife to butcher more geese and chickens and prepare a delicious lunch for them, because his Germans would be working there all day. He stationed a number of Germans on watch in the small forest around the ditches, and the rest opened bottles of brandy and wine, of which they had brought cases with them. They sat down on the grass and began to eat and drink. At nine o'clock, they brought in the first group of Jews. They were tired from the eight-kilometer walk. Some were severely beaten and bloodied. The Jews were forced to strip completely naked, line up in a row, and were forced by six men at a time to enter through the narrow entrance into one of the ditches. On one side of the pit stood bottles of drinks, foods, and a gun lay right there as well. The German, who was sitting on a stool next to the table, ordered the six Jews to lie face down on the ground. A series of shots was heard, heartrending screams, and the first six victims were dead. Soon, the next six Jews were forced into the ditch. They had to lay out the bodies of the first ones killed, then lie on top them, face down, then wait to be shot as well. The executioner, who was sitting in the ditch, drank a lot, and with great joy between one cup and another, he shot the next six Jews. Around ten o'clock, the first group of women and children were brought, some of them went on foot and some of them went on farmers' wagons. They were forced to undress, with brutal actions and beatings, and with the same method as used with the men, six of them were herded into a second ditch, where a German also was sitting, and he murdered them. Every few minutes, a fresh transport of men, women, and children, was brought over. As a place of hell,

[Page 387]

was how the field near the ditches looked. The German police, and even more so the Ukrainian police, celebrated over the bodies, and beat them mercilessly. For many surrounding kilometers, you could hear the agonizing screams of the women, the cries of the children, and the moans of those not shot in the ditches with the Jews. The mothers held the young children in their arms as they went into the ditches, and were killed together. The murderers were drinking the entire time to maintain their courage, and became wilder and wilder. By around 12 o'clock, there were already hundreds of Korets Jews near the ditches waiting for their turn to be murdered. In order that the Jews not become restless, the Germans ordered them to do the sorting of the clothes that belonged to the murdered Jews. They had to carefully spread out all the clothes in different stacks. Separately, women's clothing, pants, jackets in another pile, and shoes and underclothing also in a separate pile. From two o'clock onwards, there were no longer any new transports, but the murdering of the amassed Jews continued. The cries and screams became more and more silent. The few hundred who were not yet murdered acquired a psychological mindset such that they waited impatiently for their line to be called up. And when the order came that the next set of six Jews should go down into the ditch, instead of just the six going down, tens of others went down too. In the end, the only thing that was heard was the series of automatic bullets and the dying screams of those who were shot. The religious ones recited Psalms, and the mothers tried to calm the children, while silently moaning. By three o'clock, the killing area was empty of Jews, and the murderers were loading up the clothing of those who were murdered, and among themselves, they gloated for each valuable item that they found in the clothing. At exactly four o'clock, an order was issued by the chief of the Gestapo that the aktzia was ended. The Ukrainians shoveled the ditch with a thin layer of earth and then left from there. Two separate ditches were filled to the top. In all, there were 1,600 dead women and children in the ditches. The third ditch was only half filled with the bodies of 600 men, who were murdered within a few hours. There were 2,200 Korets Jews

[Page 388]

killed on May 21, Erev Shavuos. 2,200 innocent people died for the one sin only, that they were Jews.

After the Aktzia

“The aktzia is over! Tomorrow morning all the remaining Jews must be at their work places. Those Jews who were wounded can go back to the ghetto. They are no longer in danger.”

With those words, the chief of the Gestapo went to the “Jewish trade workers” and to the young Jewish women who were sitting on the place near the regional administration, where the selektzia [selection] was done for the aktzia. At exactly four in the afternoon, with the German punctuality, the slaughter ended, as it started exactly at four in the morning. Two thousand two hundred Jews were murdered on that Thursday of Erev Shavuos, May 21, 1942, among them 1,600 women and children. After the announcement of the chief of the Gestapo, we did not move from our places for a long time, as if we did not understand the words of the murderers, whose orders over the last twelve hours were responsible for so many Jewish lives to be ended. I did not see on a single face any expression of relief that we were still alive. Only a solid fear was in the eyes of the few hundred of remaining Jews. I looked at the chief of the Gestapo in the elegant uniform, with the tall, polished boots, on which there were signs of dried blood, and I looked at his face for signs of anger. In his calm voice, in which you felt the neutral tone of a businessman, it was impossible to see that he had just recently experienced and commanded an aktzia, which in one event, took children from their fathers, took parents from children, and wives from husbands. On his full face I saw only a satisfaction and certain fatigue, as after completing a difficult but pleasant job.

“Is that a human being?” I asked myself.

[Page 389]

“If so, I am ashamed of humanity, and regret that I was not born as a different animal.”

Slowly, we got up from our places. We felt a terrible pain in our knees from the ten hours of sitting without moving, with our feet underneath us.

“Jews, come into Rav Leizer's beis medrash. We have to cut kriah [tear a piece of clothing as a sign of mourning] and recite the kaddish.” “But it is Erev Shavuos,” someone remarked. As shadows, we went to the beis medrash that was 100 steps away from the regional administration.

The word “kaddish” pounded on the temple as if with a hammer. That means, already saying kaddish for our dear ones, for the ones who so recently, with a few hours back, were here with us. Saying kaddish for those with whom only a few hours ago you shared pain and joy; and they are already not here, and you will never see them again. It was impossible to think about this. Your mind could not absorb the complete horror of this event.

On the floor of the beis medrash, among the broken book stands, there lay a tattered Torah scroll, and from the Ark with the doors that were wide open, a second Torah scroll showed through, without a mantel [cover], and this, the Ukrainians owned. The Jews threw themselves to the ground to pick up the Torah scroll, then put it onto the table, and with a careful method, began to roll it back up; slowly, with earnest faces, they did this. The rest of the Jews followed each movement with deep interest, with the only concern at that moment that there should not be the slightest crease, heaven forbid, on this holy scroll.

While cutting kriah, you heard heavy sighs and suffocating male cries, which emote much more strongly than the lighter cries of women. They began to daven [pray]. I sat down in a corner and observed the few minyanim [quorums] of Jews. My heart had turned to stone, as a hard coal, and lodged in my throat and choked me, but no tears left my eyes. It was Erev Shavuos, and I was thinking… It was the eve of the holiday when we received the Torah, the eve of that day, when the world, for the first time, in the name of God,

[Page 390]

heard the command: “Thou shalt not kill!” I felt that inside of me was beginning to grow the sense of hatred and loathing towards the entire world, and even towards the small group of Jews who were so immersed in prayer and in their reacting in a strange way to the great wrongdoings that they encountered head on, these Jews who thought that by saying kaddish and tearing kriah they would appease the martyrs and secure that they themselves would remain alive.

Something inside me began to grumble and an inner voice cried out: “This is not the way! It is not with prayer that we have to respond to the rivers of innocent rivers of blood – but with revenge!” When they ended reciting kaddish, I ran over to the podium, gave a vicious bang, and screamed out:

“Hear me out, you unfortunates, you Jews who are delegated to death! An hour ago, when I saw the satisfied look on the face of the chief of the Gesapo, I thought: If that is a human, then I am ashamed to be part of humanity. And now, when I look at you, how you are reacting to this great wrongdoing that the Ukrainians and Germans committed against you, I think: If this is a nation, then I am ashamed of this nation. If these are the great-grandchildren of the Jewish heroes, the Maccabees, then I am ashamed to bear the name of a Jew. It seems that we are all designated for death – some sooner, some later, but I will not go to the slaughter like a lamb!”

“Quiet, a little quieter,” I heard frightened cries.

“I am not afraid of anyone,” I responded, “and I am not afraid of death. But before I will die, I have to choke at least one German with my bare hands, turn one German woman into a widow, and turn one German child into an orphan. And then I will die with calmness. Tamut nafshi im plishtim [“I will die with the Philistines”; Book of Judges; story of a fish sacrificing itself by killing the fish that tries to eat it]!”

In the Ghetto

At four o'clock in the afternoon, the chief of the Gestapo came to us and stated that we were free and could return to

[Page 391]

our homes, and from Sunday morning on, the remaining Jews had to move to the ghetto which would be located on the shul street. He would let us know the exact boundaries after discussions with the Ukrainian authorities. The Jewish homes looked terrible after the aktzia. The doors and windows broken, the furniture shattered, everything of some value was stolen. All day, the farmers of the new city, Pajonc and Zarovye, carried the stolen goods from the Jewish homes. In order to be able to carry out as much as possible, they removed the feathers from the quilts and then filled the bedcovers with Jewish possessions and goods. The Jews did not mourn for their lost possessions that they had acquired through years of sweat and hard work, because every remaining Jew lost many valuable possessions that day, things that could no longer be returned for any amount of money. In each house, there was a father missing, a mother, a child. Many houses were empty because all of the inhabitants had been murdered. Like shadows, a few Jews wandered around the houses and could not compose themselves because of the horrific scenes. On Sunday, we returned to the ghetto. The borders of the ghetto were: In the east, it was on right side of Berezdiv Street, in the west on the left side, it was Ostreh road, where the factory of Sarah the cotton maker was located; in the north, on the small street of Voloch's house, and in the south, the house of the former Talmud Torah and the priest's location. These borders were only official because the few remaining Jews were satisfied only with several houses positioned along the length of the main shul street, on both sides. The Jews pulled together all the horrific experiences that they had lived through on that Thursday of Erev Shavuos, and created one family from all the little pieces of families that were ripped apart. They created, as we sarcastically called it, a “kohlkhoz” [collective farm]. In one house, a few “remains” of families settled: men without wives, wives without husbands, parents without children, and children without parents. In a blink after the terrible experiences, the nightmare of property loss and cruelty disappeared. Everyone happily shared the last bits of food. Especially the miraculously saved children, were generally treated as they were their own property. I and my son settled in the house of Volf the painter (Vasserman). Together with me,

[Page 392]

came Moshe Krasnostawski and his young son (his wife and three children were killed); Yitzchak Feiner and his family, the woman Kolodna and a young girl, a Chana'ke, a girl from Kilikyev, and Chana Turkenycz, the daughter of Hershel the machinist. These last ones managed our home. This is, more or less, how each house looked. In some of the kohlkhozes, there were about 20 men, as for example, in the house of Rochel Guralnik. A few days after the terrible slaughter, some Jews began to appear, those who managed in different ways to save themselves. Some hid in the cemetery between the graves, some in disguised cellars and rooftops, and some in the shelter of the old castle. There were about 800 of these Jews. In the first days of June, the total number of these Jews was up to 1,100. In these first days, with feelings of great loss, these Jews felt an indifference to everything. No one felt like doing anything. Some even sought peace through whisky, which they received from the farmers as they traded in their last bit of clothing. But slowly, life began to take on

|

|

| A sign of the local farmers, determining that the “Jew”

Moshe Gildenman is authorized to destroy Jewish homes and take the materials to Golownice |

[Page 393]

a normal format. Much of that was a result of need and of the authorities who forced the Jews to get back to their old workplaces, yet in opposition to that, they enforced new laws.

On June 10, 1942, the regional landowner approached me and ordered me to put together a team of bricklayers with whom I would build an oxen stall in Golownice. I should get the necessary building materials from the destroyed Jewish homes that are outside the borders of the ghetto. He gave me a paper that showed that I have the right to tear down the houses and take the wooden materials and bricks to Golownice. It is easy to imagine what was in our hearts as we approached the destruction of Jewish homes that were built with much sweat and energy. But with the opportunity, we also gave much aggravation to the Ukrainian bandits, mostly non-Jews from the new city, who, just after the Jews were locked into the ghetto, moved into the Jewish homes and soon felt very much at home there. I began to take apart the houses in the first row, as well as the houses which were also completely destroyed by their owners. When I ended taking apart the house of Sheindel Shayches, which was partially ruined by a bomb, I soon began to break the wall of Sarah Averbach's house, which bordered Sheindel Shayches's house. The few Christian families who lived there went to the police with a complaint about me. But this was pointless, since it was against the order of the regional landowner, and they decided to go to the German authorities. That same day, I was summoned to the consul by the regional landowner. There, I already found the Christians who lived in the house of Sarah Averbuch, and a Ukrainian policeman, as witnesses.

“Why are you destroying a house where Ukrainians live?” the regional landowner strongly asked. “I ordered you to destroy only the Jewish homes!”

“The building that I was taking down was a Jewish one,” I replied calmly. “And these Ukrainians are residents of this new city where they have their own homes. I chose this place to take apart because it is built of strong, well-constructed bricks,

[Page 394]

that are made for building a strong building such as the oxen barn, for which I am responsible.”

My answer satisfied the regional landowner and he chased out the Christians from the consul and then he asked me to show him the work. In a few days' time, in the place where Sarah Averbuch's house stood, there only remained the basics and the crumbled bricks.

The Judenrat, which the local commander had newly appointed, really had nothing to do. The requisitions were limited because once the Ukrainians had robbed the Jewish population, there was already nothing left to take. Placing Jewish workers at random jobs was stopped, because there were no “free” Jews. So, the Judenrat became busy only with [compiling] evidence of the stable workplaces, and prepared the questionnaires for putting forth new “personal identity cards.” That way, the first few months in the ghetto were calm, without considering small incidences that came up now and then. For example, sometimes, a group of drunk Germans would forcefully enter the ghetto and demand money, or Germans who were passing by would beat up some Jews as they were returning from work.

The “Jewish” Spy

In the first days of August 1942, the following unusual event took place, which gave the Jews of Korets much anguish. In the Kodnier house, which lastly belonged to Reuven the baker (Kagan), the Germans set up a camp for Russian war prisoners. The house was surrounded by two rows of barbed wire and was guarded by Germans or by Vlasovites [Russian armed forces], day and night. The director of the camp, although not a terrible German, was completely friendly with Moshe Krasnovstaski, who baked bread for the prisoners.

On August 16 in the morning, the director of the camp came to see Moshe. The director was very angry, and said the following: “Tonight

[Page 395]

the guard of my camp shot a Jew who was approaching the camp apparently with the goal of eliminating the guard and freeing the prisoners. When they told him not to move, he began to flee. The guard shot at him and killed him. Now he is lying on the ground, 30 meters from the camp. This is a very uncomfortable situation and one that can have bad repercussions. From my side, I am telling you that I will not make a big deal out of this, if the Ukrainians do not get involved. In any case, I advise you to get that Jew off the road because if Germans who are passing by will see him, and learn under what circumstances he was shot, all kinds of negative actions can be taken against the Jews in this ghetto.”

Moshe Krasnovstaski and I quickly went to the place where all this happened. Near Kaminer's pharmacy, lying in a puddle of blood, there was a strongly emaciated body, with a yellow, pointy beard on a pale face. He was barefoot, without a cap, in a linen, short shirt thrown over the pants, as the farmers wore. We examined him and figured out that he was Jewish. We called over some other Jews, put the body on a stretcher, and carried him to the cemetery. In the place where the murdered body lay, some women remained to wash the blood off the rocks and to get rid of all traces. We knew that this person was not a spy, as the German had stated. According to our thoughts, this was a Jew from a nearby town, who dressed in farmer's clothing in order not to be noticed as he entered Korets, where there was still a Jewish neighborhood. We gathered a minyan of Jews [ten men] in the cemetery, found an old tallis [prayer shawl] in which to wrap the body, and began to bury the corpse. Suddenly, a strong unit of Ukrainian police arrived in the cemetery, with the well-known Mitke Zavierucha at the head, who stated that he wanted to be present at the burial to make sure that the Jews were not burying anything else with this spy. At the same time, once again they searched the dead body, and looked through his clothes. In one of the pant's pockets, they found three small pieces of wood on which there were Roman numerals written, a piece of a ground-up pencil, and a clean

[Page 396]

piece of paper. Zavierucha thought long about these pieces of wood that looked like a child's toy, then, in a decisive tone, he declared: “This is not simply a toy, this is a secret code that this spy used to communicate with his assistants who, for sure, are living among the Jews in the ghetto, and who would help him liberate the Jews from the camp.” We quickly understood that this horrible anti-Semite was planning a terrible incitement that could come at a great price for us, and we started to plead with him that he not do that. Our pleas had no effect. We buried this unknown Jew, recited the kaddish, and with a heavy anticipation, left the cemetery. Two days later, we found out that the police had sent away those very pieces of wood, which had been found on the dead body of the Jew, to the regional commissioner in Rowno and included a report in which they described the entire incident, and then requested that a commission be sent over to pass judgement on the event. We imagined how the regional commissioner would receive the news of the Jewish spy and what we could expect from the judicial commission. Terror engaged all the Jews in the ghetto, and we waited to receive each hour a new judgement connected to this terrible frame-up that the police had provoked.

On the third day after the above-mentioned incident, an old farmer came to the Judenrat, and said the following: “He is from the village of Dermonka, 20 kilometers from Korets, and his name is Vasil Gosik. A week ago, his son, thirty-something, disappeared from his home, and for more than ten years, he has not been normal. The farmer went to look for him, and the clues led him to Korets. Here he found out that the guard of the camp for Russian war prisoners shot him, and the Jews buried him in a Jewish cemetery. Since his beaten body looked maybe circumcised, they mistook him for a Jew. Now he is asking back for his son.” This made a huge impact on the Jews in the ghetto and it was decided to invite the representatives of the government that they be present during this procedure. In the presence of the commandant of the Ukrainian police and a representative of the local command,

[Page 397]

the grave was opened. When the tallis was removed from the body, the farmer immediately recognized his son, and with tears, the father befell him and began to kiss him. A protocol was put together and everyone present signed. The Korets farmer took his son, and the Korets Jews exhaled freely.

The Summer of the Year 1942

The Jews in the ghetto resumed living a “normal” life. Everyone worked in his regular workplace. The moods improved, because seeing what improvements had happened to the Jewish possessions and goods, no one was stingy nor thought about the distant future. They traded with the farmers, using clothing for flour and other products. From time to time, they even brought over a sheep or calf into the ghetto. Nachum the shochet [ritual slaughterer] did his work and the Jews ate kosher meat. The Jews in the ghetto had already calmed themselves, and began preparing potatoes for the winter and wood for heating. There was even a wedding in the ghetto. Kunitze the tinsmith, who lost his wife and children during the aktzia, married an older, lonely woman. What helped to calm everyone was that in the first row at the wedding they repeated the words of the Germans, that the few remaining Jews, who are useful to the city, would not be eliminated. Second, they started to distribute new passports to all the Jews, starting at age 14. These documents were printed on gray paper with a Star of David on the first flap and identified with a photograph. The handworkers received, other than that, workers' permits that were printed on the same type of paper, and at the top were the words written in thick writing: “Jewish craftsmen.” Another good action for the Jews in the ghetto was the process of distributing these documents. The government required that the worker fill out a large questionnaire, where there were tens of questions to answer, for example: What is the mother's female side of the family, where did you live before the war, what sort of education did you have, which languages do you speak, do you have relatives outside of the country,

[Page 398]

|

|

| A passport that the German authorities gave to the Korets Jews a few weeks before the liquidation of the ghetto |

and so on. This precision and exactness when giving out the new passports left the impression that the few remaining Jews would be treated as stable citizens of the occupied territory, and there is no more danger of being eliminated.

The majority of the Jews thought this. The tale given over by Hertzel Yucht, did not make a difference. He had saved himself from the Rowno ghetto during the liquidation, and he said that in Rowno, the Germans, a full month before the liquidation, also started distributing new passports.

Only a small group of Jews, in which I completely wrapped myself,

[Page 399]

did not allow themselves to be tricked by the Germans, and did not believe that we Jews would be allowed to remain alive. Soon after the first slaughter, we got organized and decided to escape to the partisans in the forest. The fact that our lives were arbitrary is what I saw when the German murdered the Kilikiev Jews. This led to a second incident, which I will describe. This was in January 1942. I, and a few other Jews from the village of Suchowola, returned to Korets. There we worked with building railway lines from Suchowola to Fiszewo, in order to be able to transport wood for the Korets sugar factory. When we were close to the Zherebilov bridge, we heard heart- rending cries of a woman. When we got closer, we saw a horrifying scene. The two Germans who were guarding the bridge, were laughing loudly. One of them was holding a bloodied child of about seven or eight months at the edge of his gun, and was tossing this child back and forth to the other guard. One caught the child on his bayonet, then threw it back to the other. A woman with flying hair ran from one to the other, and begged the thugs to stop, kissed their clothing, until she was depleted, and then passed out on the road. Then one of the murderers shoved his bayonet between her shoulders, pulled it out slowly, and wiped the blood off with the dress of the tragic victim. At that moment, a farmer passed by, and they stopped him and ordered him to remove the “dirt” from the street. The farmer brought the woman and child to Korets, where some recognized her as a Jewish woman from the town of Jaronu near Zhvill. That incident once again determined that we were completely unprotected and that our lives were not only totally dependent on an order from the higher authorities, but even at risk of a “joke” from a passing-by German or policeman. Then, the idea in my head was already ripe that I should leave the ghetto for the forest which I had chosen for the summer. After the first aktzia, as I saw what was going on in one day, when in such a raging manner 2,200 Jews were killed, among them my wife and 13-year-old daughter, I was obsessed with taking revenge. I was sure that sooner or later I too would be killed, but …

[Page 400]

|

|

| A registration card that was given only to the Jewish workers |

my only desire was to kill at least one German with my own hands to account for my wife and child's death. I began to summon Jews for the fight, and for resistance. I created a song that soon became very popular in Korets and in other ghettos, with the following content:

“Days of pain, of suffering, pulling yourself away slowly,

And they change

As shadows in the distance

Nights of waiting, of fear.

And the heart, filled with pain,

Cannot find comfort anywhere.

But one deeply wants to live

And really outlive

From vengeance, the happy hour.

It is not alive, not dead, always with fear and in need,

Is it not more beautiful

[Page 401]

to die as a man

In battle, with a heroic death.

Young and old, come to the forest!

Tear yourselves out of the ghetto!

Ten will fall,

Ten will live.

To fight, all you Jews, forward!”

Not all Jews came forward to go into the forest to the partisans, and not to allow themselves to be slaughtered like sheep, and to carry arms. I want to relate some of the conversations with the Jews of the ghetto, from which you can feel the moods and who will give an answer to the question which was asked of me: “Why have so few Jews chosen the way of fighting?”

When I approached Yitzchak Michelson – the son of Meir Michelson, the owner of the publishing establishment, asking that he come with me into the forest, he replied:

“Leiter, from the publishing establishment, who is a very proper German, told me that in Hitler's program, there is no law about killing all Jews. Only the Jews who are useless get killed. Those who work as engineers or as I work, as a compositor, those he will not kill. And it is understandable, because he does not have any Ukrainians to take our place. And if he kills us, then he would have to replace us with Germans, whom he needs more on the front, and Hitler is no fool, so he will not do that. And secondly, I have no energy now to go into the forest during the winter.”

As a Ukrainian told me, one who worked with Yuzik at the printing station, that when the Gestapo surrounded the printing building on the day of the liquidation, Yuzik and Dovid Gilman (the son of Shloime Kives), hanged himself. For that, he had energy.

On Rosh Hashana of 1942, during the time of davening [prayers], I said to Yukel, the son

[Page 402]

of Nute Markus, that after the holidays I would go into the forest to the partisans, and if he wishes, then he can join me. Yukel laughed, and said:

“Moshe, I thought you were smarter than that. What kind of idea do you have to go into the forest, when the Germans are already in Moscow and will take over the entire world. We will totally exhaust ourselves and then die. The situation in the ghetto has gotten much better. You can exchange a possession with a farmer for some white flour, and I even get fish for Shabbath sometimes. And if it will continue like that, then I will have things to exchange for another five years.”

His five years ended in less than two weeks. When I told Yulik Maliar that my son would be leaving the ghetto in the coming days and I had to stay for another few weeks because I was dealing with a Polak about smuggling arms and then I would also leave and go to the partisans, he began to shake with rage.

“You will make us unfortunates,” he shouted. “If they will find out that you went to join the partisans then, God forbid, they can kill all the Jews in the ghetto. Don't even think of doing this!”

Moshe Krasnostawski, with whom I was living, absolutely refused to go with me into the forest. He said that after losing his wife and three children, his own life had no value, and he would wait in the ghetto for his own ending. My arguments about revenge did not help at all, saying that a few Jews must save themselves so that they could bear witness for our ending. Since we knew about his connection to the head of police, Mitke Zaveruche, I declared to Moshe:

“Are you imagining the pleasures you will give Mitke when he takes you to the grave and shoots you?”

“Stay calm,” Krasnostawski replied. “I will not give him that pleasure, not even one thread of your things or my things that are in the house will get into his hands.”

“What will you do?” I asked, perplexed.

“I have prepared some bottles with benzine, and in the

[Page 403]

last minutes, I will lock the door, ignite the benzine, and then I will burn along with the house.”

“In order to do that, you have to have a lot of energy and a very strong will,” I said. “That is a heroic act. But tell me, what will this give to the Jewish people? I do not agree with you. I do not want to die like that in sanctification of God's name. I want to follow our great Jewish heroes – the old Matisyahu and Yehuda Hamaccabi. I want to die with Shema Yisroel on my lips, but with ammunition in my hands.”

These few examples that I have given, reflect the moods of the greater portion of the residents of the ghetto, and that was the reason that so few Jews saved themselves in the forests in the groups of partisans, where there was the opportunity to take revenge, and if you were going to die, then it would be a heroic death.

The Last Days

Rosh Hashana 1942, the Jews davened [prayed] in the former shoemaker's shul. This was the only remaining intact shul, which, because of its small shape was not changed into a granary by the Germans. The Jews, who had to go to work at the normal time, davened [prayed] later. I will never forget that two-day Rosh Hashana. The entire prayer time was filled with cries of the gathered men and women. All the Jews from the ghetto were in shul, even those who were less believers, prayed with great depth. Everyone felt that the only help they could now expect was from God. The most painful moments were during the times of reciting kaddish [prayer for the dead], which was recited in one voice by all those gathered there, because there was not one person there who had not lost a family member and did not need to recite the kaddish. On the second day after Rosh Hashana, rumors began to spread that the Germans would be planning to eliminate the few Jews who were in the ghettos in Wolhyn. A terrible fear grabbed the Jews in the ghetto when they heard this news. The comforting words of the German and Ukrainian work managers did not help the situation. The terrible event of Erev Shavuos was still too fresh and did not allow for anyone to believe false promises. When these rumors

[Page 404]

spread among the farmers, they began to enter the ghetto and say to their familiar Jews that they would hide them until the danger passes. Many innocent thinking Jews believed these gutsy Ukrainians, and meanwhile gave them their last possessions and then agreed on a time when they would be able to come to them. As it later was revealed, these “good-hearted” people, after they stole all the possessions, never allowed even one Jew on one step of their houses. The chaos grew every day. When they asked the familiar Ukrainians, those who were in the government, whether the rumors of liquidating the ghetto were real, they raised their shoulders and replied:

“Do the Germans reveal their plans to us? Save yourselves, whoever can.”

My son and I, and 16 other Jews, decided to leave the ghetto in the next few days. The delay was getting the arms, which a Polak from the village of Dermanka was supposed to bring over. On Wednesday morning, September 23, two young boys, who, following my orders to keep an eye on the building of Itze Weitman, where the policemen were, told me that some cargo trucks had come with new policemen. A few hours later they told me again that four large units of policemen had left Weitman's house, fully armed, and went in four different directions. I understood that these policemen were positioned so that they could strengthen the guard level of the ghetto and the exit of the city. We could not wait any longer and after a short discussion we decided to leave immediately. Three or four men at different points managed to get out of the ghetto, and arranged to meet at the exit of the city in the house of Vasil Kavaliec, who appeared to be very friendly to the Jews (exiting the ghetto and killing a Ukrainian policeman is described in detail in my book “On the Way to Victory). I left with my son and with my nephew Siomka Geifman through Ostreh Street. Our plan was to get into Shlosspark [palace park], and opposite the church we would cross the river and

[Page 405]

then go through the farmers' fields and get to the exit of the city. I had a gun with five bullets. This was the only weapon that we managed to get. We decided that if we encountered police or Germans, we should not surrender ourselves alive into their hands. In worst case, I had decided that I would first shoot my son and Siomke, and with the last bullet, myself, because we knew, that if they would capture us alive, a terrible death would likely be awaiting us. At about five o'clock, we were in Kovaliek's house, and there we met Avigdor Zoike, Lozik Gershfeld, Hershel Chapes, and Dvoire and Faigy Kaftan (daughters of Berky the porter). By evening, there also came Moshe Milrod, Motel Bazhik, and Shternshish (son-in-law of Malya from the sacks). When it got dark, we left Kovaliek's house and went through the fields in Golownice in the direction of Vodnyk. We moved all night, and at dawn we were already on the other side of the Slucz River in the dense woods near the village of Miszyakov.

Liquidation of the Ghetto

On Friday, 13 Tishrei, year 5703 [September 24, 1942], Erev Sukkos, the doctor, Yakov Wolloch, who treated Russian war prisoners in the camp, came into the camp in the morning, as usual, for a visit. To his great surprise, he did not find the prisoners in the camp. Only those who were sick were around, and the superintendents, who did not welcome him warmly at all, and gave him an earful, told him to leave the camp. This cold welcome unsettled him, and as he was leaving, he asked one of the sick people, whose life was saved by Dr. Wolloch, where were the rest? The sick person told him secretly that the entire camp left to dig ditches for the Jews who were to be executed that day. Dr. Wolloch quickly went to the Judenrat and related this terrible news. Very soon, all the Jews in the ghetto knew about this, and a there was huge chaos. Some of the Jews went to commit suicide. A group of about thirty decided that they would escape from the ghetto, but it was already too late. As if with a steel ring, by Ukrainian police and a Gestapo force,

[Page 406]