Hrubieszow is Dying

|

On the Brink of Annihilation

|

|

|

[Columns 597-598]

Hrubieszow is Dying |

|

|

| Jews from Hrubieszow before the grief–filled death march in December 1939 | ||

On the Brink of Annihilation |

|

|

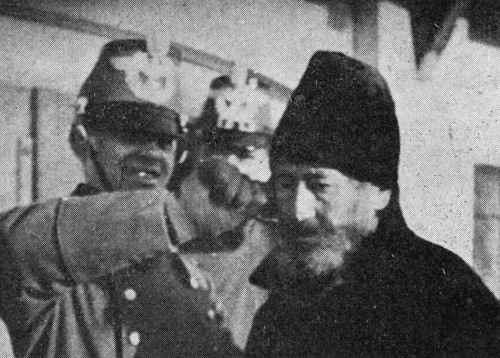

| A Hitlerite murderer cuts off the beard of Yaakov Yehoshua Shteinboim |

[Columns 599-600]

by Avraham Eizen z”l

Translated by Miriam Bulwar David-Hay

For people who did not themselves live through the destruction of the Jewish community of Hrubieszow, it is not possible to give an exact listing with all the details of those shocking events.

Even the testimonies given by people who themselves experienced the tragedy do not, on many occasions, agree on the details. This is simply because the horrifying conditions in those times did not allow for a row of important dates and events to be ground into the memories of the remnants of the slaughter.

This can be said even of such large cities as Warsaw, Vilna[1], [and] Łódź, where the ghettos – because of their relatively longer existence – in part led a registered chronicle of facts and duly took care to hide the materials, and even more so in the smaller cities, like Hrubieszow, where the executioners regularly stood with a knife at the throat [of the Jews] and within a short time completely wiped out the Jewish community.

Setting aside all of the technical and psychological difficulties, it is still possible to set up a prominent picture of the destruction. I wish here in general strokes to reconstruct the destruction of the Hrubieszow community, also supported by several testimonies that have been given, and especially of dates that were handed to me in 1946 by the survivor Mrs. Roza Zilbermintz.

The period before the ghetto

In July 1939, I came from Vilna to Hrubieszow on a vacation. I was there until the outbreak of the German–Polish war in September. Seven days after that, the Germans were approaching close to Hrubieszow. The local Polish evacuation force organized for all those on military duty to leave the city.[2] Together with hundreds of Hrubieszow residents – Jews and Christians – I let myself head towards the east. I went with my group to behind Kovel[3]. There we heard that the Soviets had taken the eastern territories of Poland, among them Hrubieszow. We returned and celebrated with the Jews of Hrubieszow, who were of the belief that they were already free of the Germans.

But the joy did not last long. The information soon spread that the border line of the Soviet eastern zone would be the Bug[4], and that Hrubieszow would go back to the Germans.

The sad news was met by the Jews of Hrubieszow like a thunderclap. Everyone was in extraordinary, depressed agreement – a type of foreboding of the great misfortune that was awaiting them. Hundreds of people – and I among them – set out in the direction of Ustile[5]. I say hundreds of people, because from whoever–it–was I heard that several thousand Jews from Hrubieszow left their homes then. I do not, however, believe in the exactness of that figure. In their entire way of thinking and outlook, our young people felt with their most intimate fibers bound up with the town. They talked themselves into all the possible and impossible miracles [that could occur], so as not to pick up the walking stick.

And what did they not prove to themselves in talking then? That the German would soon suffer a defeat; that he would need the Jewish workhands and would not sew himself in [to a corner] with a quiet, industrious population[6]; that the devil is not as terrible as he is painted to be. The same self–convincing talk of all Jews in occupied Poland who did not want to, or who could not, move from their place.

It is impossible to ease the pain in one's heart when one thinks of the eternal Jewish credulousness that in every era – and even more so in the last catastrophe – cost us days of blood. The Nazi hangmen? Of course. They cruelly poured out our blood. But perhaps no less our own, childish certainty – that frivolous certainty of an old, experienced, and nevertheless inexperienced people[7].

If one should even accept that the figure “several thousand” is correct, the fact remains that masses of Hrubieszow townspeople quite quickly returned back home. They turned back as soon as they received greetings[8], that the Germans were still there, “unfortunately,” just as they had been during the first time[9]. They returned, because in front of their eyes lay their birth town, and it winked at them, towards Ustile, towards Ludmir[10], towards the entire diaspora of Volyn[11]:

– Come back! You are still close to us! For what do you need to torment yourselves in strange lands?

It is possible that if the border line had not been the unfortunate one it was, extended by hand, closer to the Bug, that masses of Hrubieszow Jews would today perhaps be among the living. There would not have been such a strong pull for them – the refugees – to turn back, and those who remained in their homes would not have let themselves rely on “when the time comes” (“When the time comes, God forbid, we will quickly get to the other side of the border”).

The time, unfortunately, nevertheless came – much earlier, and in a different way, than our townspeople had judged. Two and a half months after their entry into the town, the Germans took hundreds of Jews from Chelm, Hrubieszow, and surrounding places, and drove them to the Bug.

We cannot even to this day know exactly the reasons why at that time the Germans chose to unleash their greatest anger on these specific towns in the province of Lublin. In Vilna there was talk that they wanted the border region to be populated as little as possible with any uncertain elements, and to this end they, naturally, thought of the Jews. But the border line stretched along the entire eastern passage up to the Baltic? So why did that sorrowful expulsion fall just on those specific towns in the Lublin province?

|

|

Standing: Chana Sass Seated: Itsik Sass, his mother, and Hersh |

[Columns 603-604]

Perhaps what is correct is a second rumor, that this was an act of revenge and a show of strength on the part of the Germans because of a series of diversions in that territory, for which their suspicions fell first of all on the Jews?

Be that as it may, the fact remains that our places, almost earlier than other Polish districts, endured that first, bestial blow from the Nazi murderers. They ordered the adult male population of Hrubieszow to assemble on the “Vigon[12],” next to the slaughterhouse, where [ostensibly] they would just check their passes. The assembled men were quickly surrounded by soldiers on motorcycles, who robbed them of their passes and declared them to be “stateless” citizens.

Immediately after this, they [the Germans] chased them to the Soviet border. This was a wild, sadistic, and inhuman race. It seems that the Germans at the time planned to send as few Jews as possible to the border, and to drive them there exhausted and in a state in which they were on the verge of death. Those who physically could not keep up with the running were shot along the way. Others drowned when they were ordered to swim across the Bug.

What did the Jews from our region think after their first experience with the Germans? Did they gain an understanding of what was awaiting them from the occupier? Did they draw all the required conclusions?

The structure of the ghetto

The Hrubieszow ghetto found itself in a crowded quarter, in the eastern part of the town, with its border from the Aryan side drawn along the old market, beginning from the corner of Staszica Street and Stary Rynek[13] to the corner of Narutowicza Street and Stary Rynek. In this way the town was divided into two parts: into a Jewish part and into an Aryan part. In the Jewish part, the main streets were: Stary Rynek, Wojtowskwo, Lazienna, Jatkowa, and so on. The Aryan quarter took over the entire western part of the town, the streets: Nowy Rynek[14], Third of May Street, Narutowicza, Lubelska, and so on, and the streets Staszica, Podzamcze, [and] Pilsudskiego on the southern side.

The ghetto found itself in the very poorest and most scantily built up district of the town. When one takes note that in the area of the ghetto, before the war, around a third of the Jewish population – 3,000 people – lived, it comes out anyway that in the time of the ghetto, the district was overpopulated with around 5,000 more Jews. (Before the war, the count of Jewish residents reached a total of 10,000 souls. However, we can assume that up until the beginning of the ghetto period, the count had been reduced by 2,000: those who had fled and those who had perished.)

The 8,000 Jews – pressed together and squeezed together with several families in one dwelling – immediately had to endure persecutions and decrees that were characteristic for the ghettos of that time: yellow patches, a prohibition against visiting in the Aryan district without a permit, and travel allowed only on the main road. The synagogue, the batei midrash[15], and the shtieblech[16] found themselves on the Aryan side. Hrubieszow's Jews therefore had to arrange their houses of prayer in the area of the ghetto.

The social and economic structure in the ghetto was almost the same as in other towns:

The situation of pain and suffering, of daily scoffing [by the Germans] over the tortured body of the Hrubieszow community, lasted until the 31st of May, 1942. On that day, its fate was already sealed.

The liquidation

The stages of the extermination of the Hrubieszow Jewish community present themselves thus:

On the 1st of June, 1942, around 3,400 Jews were taken out of the ghetto and were led to Sobibor, behind Włodawa, where they were murdered in the crematoria there[20].

On the 7th of June, 1942, around 2,000 Jews led out of the ghetto.

On the 21stof November, [1942,] the last group of Jews was sent out of the ghetto.

In the Hrubieszow cemetery they were shot:

On the 1st of May, 1942 – several Jews.

On the 8th of June, 1942 – more than 200 men.

On the 28th of October, 1942 – around 400 men. (The shootings on the holy ground went on routinely, every day, until the 1st of February, 1943.)

From the surrounding towns [Jews] were led to their murders in Sobibor and Majdanek through Hrubieszow:

[Columns 605-606]

The 3rd of June, 1942 – Dubienka.

The 5th of June, 1942 – Belz.

The 9th of June, 1942 – Grabowiec and Uchanie.

Information is lacking about Horodło. But it would seem that the last group of Jews – several thousand – which was sent out of Hrubieszow on the 21st of November also included the Jews from Horodło and the remnants from the surrounding towns. It could also be that the Jews from Horodło were killed next to their town. Therefore they were not mentioned by the eyewitnesses from Hrubieszow.

It should also be mentioned that the date of the final liquidation of the Hrubieszow ghetto (21.11.1942), which was given to me by Mrs. Zilbermintz, does not agree with the date that was given to me by a second source (20.12.1942). The difference is in a month. But Mrs. Zilbermintz also gave me the Jewish date: the 13th day of Cheshvan. We must therefore accept that the 21st of November[21] was the day on which Hrubieszow became Judenrein[22].

But this tabulation also shows us another thing, that the steps to the elimination of the ghettos in Hrubieszow and the district took place in the second half of 1942, that is, at a time when the Germans were at the very highest point of their achievements [in the war]. When we take into account that the liquidations of such ghettos as Warsaw, Vilna, and so on were first carried out in 1943 – when the Hitlerism began rolling downhill – the question then presents itself: Why did the Germans in these towns, like Hrubieszow, hurry so with the elimination? The answer can only be one: workhands.

The death sentence for Jewry in the occupied domains was signed even before the beginning of the Soviet–German war. It was only temporarily laid aside because of a shortage in the labor forces, which the Germans then filled. By that measure, when in this or in that place they stopped needing Jewish workhands, they would step by step liquidate them. This declares itself in the way that, in such towns as Landvarova, Haidotsishok, Radzhishke[23], and so on, they [the Germans] carried out the elimination in the initial months, immediately after the outbreak of the war.

In Hrubieszow and the surrounding area, the Jewish workhands were first replaced by Poles and White Russians[24] in the middle of 1942. That moment decided the fate of the Hrubieszow ghetto.

Were the Jews who were led out of the Hrubieszow ghetto immediately put to death in the extermination camps?

|

|

| Hrubieszow Jews with armbands – did they know what was awaiting them? |

We can assume that, towards the Jews from the Hrubieszow ghetto, the Germans also used the same method that they used in other extermination camps: that is, the selection method of “right or left.” Those who were incapable of labor, elderly, and children were exterminated directly on the spot, while against this they, temporarily, left alone the young, forces capable of work.

It therefore raises the thought that young people from Hrubieszow lived for a time in a given camp and there filled assorted internal jobs. This is especially so when all this was taking place during the “lightning time[25]” by Nazism, when the front was in need of a series of war materials, which the workshops in the camps would fulfill.

With regard to the Hrubieszow Jews who were shot in the cemetery, it should be noted here that in the chronicles of Jewish martyrology in the time of the ghettos there are only a few cases in which, when the German murderers were going to have masses of Jews shot, that they did so as openly as they did in Hrubieszow, with the exception, of course, of the places where uprisings took place – Warsaw, Bialystok, [and] Vilna, where the Germans battled against the rebels in the ghettos.

Apart from Lintop[26] (behind Sventzian[27]), the Otwock region, and several other places, the Germans for the most part carried out their work of murder masked and hidden from people's eyes: behind cities, in forests, camps and crematoria. Here and there they even tried to wipe out the traces of their murders, by taking the bodies out of the mass graves and burning them in firepits. In Hrubieszow, however, they dared to do this in the very town, in front of the eyes of the local Christian inhabitants.

As the numbers show, more than 600 people were shot on the holy soil [of the cemetery] from the 1st of May to the 28th of October, 1942.

We do not know the number of those who were shot on the spot after the liquidation of the ghetto. However, we can estimate that this was a considerable number of Jews, who had hidden themselves away from the departing transports in cellars, burrows, and other accommodations.

Is it possible that the executions in the town were in themselves carried out in the name of terror, so as to frighten and force the Jews to go along on the agreed dates with their transports? Whatever the case may be, the fact remains that in the area of Hrubieszow the Germans very quickly took into account – but did not expect – any abhorrence on the part of the Christians to the public acts of murder.

The Aryan neighbors

Did anyone from our unfortunate townspeople have an attempt made to rescue them from the Aryan side before or during the liquidation of the ghetto? Were such rescue attempts possible? Could one expect help of any kind from the side of the Christian neighbors?

It is easy to imagine that there were probably those broken individuals for whom, because of the inhuman conditions, death was more agreeable than life. But leaving aside the horrible situation, until the liquidation the collective did not lose its belief and hope that a change could take place at any minute: a change on the war front, a revolt in the Wehrmacht against Hitlerism, an intervention from abroad for the benefit of the ghetto Jews. One did not lose hope, because to live even one day under Nazism demanded gigantic powers of superhuman resistance, even more so to live under such domination for a full three years.

The fountains of certainty and patience that in those first days of the war deceived the Hrubieszow Jewish community and did not allow it to pick up the walking stick did not dry up even then, when the horrible reality,

[Columns 607-608]

in all its ugliness, showed itself to the unfortunates. Only in this way can we explain how, after a day of the wildest persecutions and punishments, of physical exhaustion and fear of death, could they lay themselves down to sleep in the ghostly darkness of the ghetto, so that in the morning they could once again arise to a new, prospect–less day! And only in this way does it become conceivable that attempts to save themselves in one way or another were employed only by the young, leaving aside that the entire surrounding area, outside the ghetto, terrified and paralyzed [the Jews] with its bottomless hatred, its coldness, and – in the best case – its indifference. The unfortunate Hrubieszow lay in the very center of a Christian area, which burned with hatred for the Jewish victim no less than the German occupier did. The entire province of Lublin was one of the favorite districts of the unrestrained youth of the N.A.K.[28], whose powerless Polish patriotism expressed itself first of all in suffocating and slaughtering the hunted ghetto Jew who had by a miracle escaped the German axe. The forests behind Lublin, Zamosc, Hrubieszow, [and] Krasnystaw hide within themselves a great many of those bloody mysteries, when escapees from among the ghettos' Jewish young people – prepared to fight and to take revenge for their violated folk – were brutally murdered by those Polish outcasts.

They are silent, those very forests! They do not speak! But the quiet rustling of their shadowy depths sometimes tells of horrible, bestial murders of blameless Jews, no less than do the extinguished chimneys in the crematoria.

And the civilian Christian vicinity? Did it do anything for its unfortunate Jewish neighbors? Help them with something? Hide away those who were seeking protection? Here too, unfortunately, the account for the most part comes out negative, setting aside that the Hrubieszow Poles welcomed the first returning Jew – after the entry of the Soviets – with jubilee, and also setting aside the concealment that a few individuals gave to several Jews. The number of those who were hidden is naught in comparison with the protection that Poles from other places, and even Lithuanians, gave Jews, while thereby placing their own lives at risk. I say “even” because, as is known, Lithuanian special battalions helped the Germans carry out mass executions of Jews. And still, Lithuanian civilians in a series of Lithuanian towns hid and saved unprotected ghetto people. However, that praise cannot be said of the Christian neighbors of the unfortunate Jews of Hrubieszow.

Summer 1946

In the summer of 1946 I drove out from Vilna towards Łódź. I drove down to Hrubieszow and there met around 10 Jews who had survived, most of whom had saved themselves in the Soviet Union. All the Jewish houses were being lived in by Christians. The Jewish stores – taken by Polish merchants. No trace was left of the Jewish Hrubieszow that had once existed, apart from the tombstones, which had been used to pave the sidewalks. In the synagogue street, blind and stiff like a dead person, stood the great synagogue, hardening [like a corpse] in the empty space, with its torn out windows and its walls full of holes. All the batei midrash and Hasidic shtieblech, which had been gathered in a half–circle around the synagogue, had disappeared, together with their prayer–goers. The cemetery had been leveled with the ground. No sign of any tree, or any shrub, that had once shaded the graves.

An old, well–established community, that for hundreds of years, with blood and sweat, helped build a city, was mercilessly wiped out from the world. Even its people from long–deceased generations were not wished well in their eternal rest in the ground.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Leibish Prost, Bat Yam

Translated by Miriam Bulwar David–Hay

Already in the first days after the onslaught by Hitler–Germany, the fate of Poland was sealed. The German air force was the sole sovereign over the Polish sky, and every day bombarded the towns and roads.

Hrubieszow, which shared the fate of other towns in Poland, was bombarded and shot at from the air. The first victims fell: Mottel Shteinboim, or as we called him, Mottel Yaakov Shaya's[1]. He was the first victim, who was shot by a German airplane as he was driving his droshky[2] through the town.

The town was as if it had died out. Fear and deathly terror ruled over the Jewish population. The economy became paralyzed, the businesses were locked up. The tradesmen did not work and a shortage in food was dominant.

On Erev Rosh Hashanah[3] the news spread that the German advance posts were already to be found close to Hrubieszow. German reconnaissance airplanes indeed immediately showed themselves, a terrible panic broke out, and a number of young people decided to flee.

With their rucksacks on their backs, after bidding farewell to their parents, they were away on unfamiliar roads, along which lurked dangers. They traveled only by night, because during the day the German aviation was lurking. It turned out that they did not have far to run, reaching the town of Trisk[4], when it became known that there had already been an agreement signed between the Soviet Union and Germany over the division of Poland[5].

Immediately after the first Soviet military divisions crossed the border and began setting up garrisons in the towns of Polish western Ukraine and Belarus, revolutionary committees spontaneously began to organize themselves, so as to maintain order in the transition period and to prepare the recipients for the Soviet army. In a number of places, the Polish military groups returned to the towns they had left, and there met a bloody reckoning from the members of the revolutionary committees.

In Trisk, where a group of those who had fled Hrubieszow found themselves, a Polish military division met up in a house with the Hrubieszow group, assumed that they were Communists, and immediately stood them against the wall to shoot them. But before that, when they were successful in convincing the Polish officer that they were not locals and that they had fled from Hrubieszow together with the Polish army, they were set free again. On the second day, the Soviet divisions had already entered Trisk and cleaned out the area of Polish military units. The road to Hrubieszow was free, and the escapees returned back to their homes.

On Rosh Hashanah the German motorized divisions entered Hrubieszow.

[Columns 609-610]

A town delegation with the town president at its head met them with bread and salt[6]. Some Jews also went out to greet the Germans with their hands raised[7]. The Germans did not react to the greetings and continued their march. That same day, they managed to shoot Chaim Badachanes's son–in–law, who upon seeing the Germans – out of fear – took off running.

After settling in the town, some of the Germans of Austrian descent soothed the frightened Jews that nothing bad would happen to then. Suffering losses at the Bug, the Germans pulled back to Hrubieszow, bringing with them a great many wounded. At night, with the help of Poles, they tore up Jewish businesses and robbed the merchandise.

On the third day, the Germans left the town, in line with the pact with the Soviet Union, and in their place the Polish military entered the town. The population took them in with joy and made sure that nothing was lacking for them.

A certain Polish major, who could not make peace with the thought that the Polish kingdom no longer existed, decided on his own accord to lead a war against the Soviet military. While collecting together military groups that had found themselves around Hrubieszow, he opened fire on the Soviet divisions. After a battle that lasted an entire night, during which victims fell from both sides, the Soviet divisions took over the town.

The Jewish population breathed freely again. A large number of residents of Hrubieszow took part in the funeral of the Soviet soldiers. At the open grave the fallen were bid farewell, in the name of the working class in Hrubieszow, by Ber Shtern. The speakers expressed the certainty that now Hrubieszow would remain Soviet for eternity. After the funeral, some former political arrestees[8] applied to the Soviet city–commander [to talk] about collaboration. At the meeting, which came together soon afterwards, it was agreed to establish a revolutionary committee to lead [activities] within the city.

As responsible for the militia, it was agreed, [would be] Moshe Korenblit, who had just come from Warsaw. From assorted groupings in society came those who enlisted in the militia: former arrestees, members of the Bund[9] and other parties. Among those enlisting were to be found some undesirable elements, who chose to exploit the chaos of the first days for themselves personally. From among these people were recruited those who amused themselves over the prisoners, Polish soldiers, while taking their personal possessions for themselves, and at the same time as doing these revisions[10], carried out criminal deeds. Until they were caught, and they were thrown out of the militia, they did quite enough to blacken their faces with shame[11].

The militia began its activities with keeping order and security in the town.

Soon, in the first days, they began carrying out revisions of suspicious persons, who were arrested, [namely] Polish police and home–agents. In the course of the arrests, Moshe Korenblit came to a meeting of the revolutionary committee with a list of Christians and Jews who needed to be arrested as opponents, who had been termed this under an instruction from the Soviet military city–commander. But the remaining members of the committee, who distinguished themselves with more reconsideration, held that there were no grounds for arresting the designated people, and that they should not arouse any panic in the town, but the opposite, the population needed to feel secure, and to be persuaded that there was no danger awaiting it from the side of the Soviet power, and the committee succeeded in averting this irresponsible step.

Every day new problems swam up. In this way a confidential message was received that at Yankel Lerech's home there were to be found several Polish nobles from the Hrubieszow area, among them the secretary of the Polish kingdom's president. The fact seemed suspicious, but knowing the situation in the villages, which were inhabited by Ukrainians, no Polish noble could find himself there[12], so it was quite understandable that the nobles would come to their Jewish acquaintances, who did business with them, so as to hide there. But that fact, that among them was such a highly placed personality from the old kingdom, meant that a decision had to be made, as to how this case should be dealt with: Let them go, and it might cause trouble later with the Soviet force. Arrest them, there has to be a reason for that. There was still no order from the Soviet force to arrest all the nobles, and, separately, the Polish population would have taken the arrest of the nobles as a pure Jewish piece of work, for which the Jews of Hrubieszow might later have to pay dearly. It was decided to send two militiamen to identify who these persons were who were being hidden at Yankel Lerech's. Upon coming back, the militiamen confirmed the message that had been received, but on the very same day the nobles left the town, and thereby this unacceptable matter was resolved.

In the interim period, nobles from the Hrubieszow area came [to the town] and asked that there be clarification as to whether the confiscations were an order of the Soviet authorities, or just an act of revenge on the part of the peasants. Who could possibly answer that question? Those were days of chaos and no one knew what was allowed and what was not allowed. But the truth is, that all the confiscations came about by familiar hands. That was the case in the requisitioning of a machine with fine shoe leathers, which two Jews from Lublin had brought to Hrubieszow, and kept at Israel Shiller's. The Soviet force in Hrubieszow took the leathers, and only later, after an intervention by the Soviet procurer, were the rightful owners given back a part of the merchandise. But among the people of Hrubieszow rumors were going around that militiamen, who had taken part in the confiscation, had skimmed the cream off for themselves.

The militia in Hrubieszow, which was one hundred percent Jewish, did not appear in a favorable light in the eyes of the Soviet city–commander, and at his wink Ukrainians started coming forward, some of whom had been political arrestees, with the aim of taking over the leadership of the town into their own hands. A certain Ukrainian, Doruch, was agreed upon as the commander of the militia, in the place of Moshe Korenblit, who became his representative. The new commander began his activities by taking the weapons away from the Jewish activists and by letting them hear that he would now be the master in the town. Wanting everyone to know who he was, he would often parade on a horse through the streets, and thereby drew attention.

Between the Jewish and the Ukrainian members of the revolutionary committee there often occurred misunderstandings. It soon happened that the Soviet commander was allowed to overhear that at work there were comrades who had in the past expressed their doubts about the correctness of Stalin's methods, and the commander quickly found it necessary at a meeting of the committee to come out with sharp words against the Trotskyites and svoloches[13], who had to be rooted out. His words were a reminder that the road to [banishment in] Siberia was open.

The economic division of the revolutionary committee was faced with difficult tasks. First of all, taking care of the provisioning of the city, and not allowing any increase in the prices.

[Columns 611-612]

For that purpose, they had to keep a strict control over the mills, which received an order to sell flour to the bakeries at the old prices. The mill owners adjusted themselves to this order, and in the town there was no shortage of bread.

The same was true with heating. The forest owners sold the wood for the old prices. The businesses had to sell early at the former prices. For the merchants, the order was a heavy sentence, because selling was easy, but buying back was impossible.

Yosef Hecht, in the name of the merchants in Hrubieszow, asked for information about the prospects for private trade. His argument was that today or tomorrow the reserves would run out, and then where would they get other merchandise. They got rid of him with a promise that everything would gradually be regularized.

Every day there would be indictments against the raising of prices. In each case, these were responded to in a sharp way. However, some did exploit the situation that had been created so as to settle scores with their competitors and enemies, and would come forward with denunciations. The denouncers would be treated with mistrust and their indictments would not be taken seriously.

There were also cases when members would abuse the trust that had been placed in them. That was the case with Yoel Kuper, who was sent to the sugar factory to bring sugar for the town, and while doing so he did not behave honestly. The Ukrainians laid that fact out on plates and exploited him as a weapon against the Jewish members.

The decision of the militia commander, Doruch, to arrest Shaul Eizen was also an expression of personal hatred. After Shaul Eizen was arrested by the peasants, who hated him both as a noble[14] and as a Jew, and was freed by the Soviets, Doruch decided to arrest him again with his own hands. He did not succeed in carrying this out, however, because it was conveyed to him through Shmuel Eli Eizen that he should remove himself [from the scene].

The culture division of the revolutionary committee set itself the task of returning studies to the schools. For that purpose a meeting was called together of all the teachers and professors, those to whom had been delegated the task of the teacher in the changed situation, and it was proposed to them that they cooperate with the new power. Separately, an application was made to Professor Shvidzinski, who was known as a liberal, that he should take the initiative upon himself and organize the schooling in Hrubieszow. Shvidzinski declared that in the given situation he was not the suitable person, and asked for a few days to give an answer. The remaining teachers did not take any active part in the meeting. It was decided to call a second meeting, which ultimately did not come together.

The Polish population stood at a distance, and no one worried about their cooperation. The Endekist[15] anti–Semites and agitators hid themselves in their holes, not daring to show themselves in the street. In general, the Poles were beaten and frightened.

In the town ruled an exemplary calm and order, but unfortunately the situation did not last. Like a thunderbolt in the middle of a clear day came the information that the Soviets had to leave Hrubieszow and in their place would come the Germans. This was a heavy blow for the Jewish population in Hrubieszow. A number of wealthy Jews from the town came forward to ask the Soviet authorities whether they would have the possibility to get their property out of the town, and if so under what conditions?

The revolutionary committee recommended that everyone should evacuate the town, and take with them everything they possibly could. Only a limited number decided to take this step. The majority of the Jews with means from Hrubieszow could not decide to leave behind their established holdings. Against this, a large part of the poorer population prepared itself for the evacuation.

The Soviet force began to pull out from the town, while it was still able to do so. At the train station there were always standing prepared wagons on which to load the requisitioned goods. Wanting some of the flour that was to be found in the mills to remain for the town, the revolutionary committee began giving out vouchers in exchange for flour. Whoever applied received a voucher for a small sack of flour. But the mill owners, knowing that the days of the Soviet power in the town were numbered, began to hide the flour. In this way, a large quantity of flour was divided up amongst the population.

All the layers of the Jewish community in the town were worried. Yosef Lederkremer requested that from the Jewish institutions the furniture also be taken, because if it was left behind, this would be interpreted badly by the Poles[16].

A large part of the militia left the district, and there remained only a small number of dedicated members, who with self–sacrifice kept order in the town.

In the last days, there already began to be a shortage of bread in the town. The bakeries stopped baking, and each one took pains to hide his stores of flour for the black days ahead.

In the yard of the militia a kitchen was active and full of the town's inhabitants, while separately the wives of the Polish officials came with small kettles asking for a bit of food. Srul Miller gave to everyone with a generous hand.

The evacuation began. The Soviet force added on means of transport, and each person who wanted to, could have their things taken to Ludmir[17] without any difficulty. In the last days, the large product manufacturers decided to evacuate – Aharon Lerner, Zisha Roitman, Moshe Hoizman, Leibl Orenshtein, and others – upon receiving permission to take their merchandise along, together with a guarantee that it would remain theirs[18]. Their leaving Hrubieszow made an impression and many imitated their example.

The Polish population in Hrubieszow, which had kept itself in the shadows, began to lift its head once again, and even before the Soviets were out of the town, they prepared an armed attack on the militia. An organized band of Poles opened a shooting barrage on the militia from the nearby church square. The small group of militiamen responded with fire. It was fortunate that still functioning was the telephone connection with the Soviet garrison, who were still in their barracks. Within a few minutes, cars with Soviet soldiers drove up and the entire area of the church square was surrounded. A few of the attackers were successfully captured.

The armed attack by the Polish population cast a threat over the Jews of Hrubieszow. It was enough of a warning that they needed to save themselves, because tomorrow would already be too late. However, the vast majority of Hrubieszow residents, pious Jews, turned themselves over to God, and with that certainty remained in the town.

Sukkot 1939[19], the last group of Jewish militiamen, together with the Soviet army, left Hrubieszow. The town was emptied of its young people, and a nightmarish, dark night lowered itself on to the remaining community of Jews in Hrubieszow.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Moshe Moskol, Bnei Brak, and Avraham Tzimmerman, Givatayim

Translated by Miriam Bulwar David–Hay

|

|

|||

The Bug River, 5 kilometers from our city, was the demarcation line between the Germans and the Soviets in the fall of 1939.

Let us recall several figures about our town: 16,000 residents, among them 9,000 Jews; Jewish councilmen, two Jewish aldermen, organizations and institutions, a library named after Y. Ch. Brener[1] with more than 4,000 books in Yiddish, Hebrew and Polish; a library named after Y. L. Peretz[2] with 3,000 books, a public school run by the “Shul–Kult[3].”

After the Soviets departed from Hrubieszow, leaving it for the Germans, away with them went some of the Jewish young people, workers, and also several merchants–manufacturers, to whom the Red Army gave cars for the drive, for the price of a little manufacture [i.e., the goods being transported].

In the transition time, when the Soviets were out and the Germans were about to come in, a self–support system was created of Jews and the best of the Poles.

On the 9th of October, the Germans entered the town. The leader of the militia, the Endek[4] Havlena, immediately removed all the Jews from the militia, with the motive that this was what the Germans had ordered. In fact, at that time the Germans had not ordered him to do anything. The Germans began catching Jews for work, and Poles, the meanest of them, helped them in that industry.

The large synagogue, which had been built in the year 5633[5], was transformed by the Germans into a horse stable. They dragged passing Jews into the synagogue, tore their beards, and beat them up. The Jews wanted only to rescue the Torah scrolls from the batei midrash[6]; the Germans forced them to trample on the Torah scrolls and afterwards to tear them up.

We wanted to regularize the matter of catching people for work, because this paralyzed life entirely. We intervened, and with the help of the mayor, who simply was not a hater of Israel[7], we succeeded in acting, so that the German district administrator would be supplied with several hundred workers each day.

Hundreds of Jews came to Hrubieszow from Łódź and from Warsaw, on their way to the Bug River, so as to cross over to the Soviets. They spoke of how in Hrubieszow things were a Garden of Eden in comparison with what happening in their cities; here in Hrubieszow, one at least received food.

A few weeks later, the Gestapo arrived. The change was immediately felt. They were not satisfied with the number of workers supplied, they also, on top of this, caught more people, and in addition beat them up. They already had a list of the wealthy Jews in the city, went around to their homes, took everything that appealed to them, and often beat up the owners.

After this, a contribution of 120,000 zlotys was imposed on the Jews, and it had to be raised in a very short time, and because they did not manage to put together such a large sum, the Germans as a penalty added a further 80,000 zlotys.

They made some of the Jewish leaders of the town responsible by putting them under house arrest, and first among them, Rabbi Tversky. On the second day the rabbi ran away from the town, hid himself in a village, and on Friday evening, while he was at prayer, non–Jews murdered him.

Jews began to run away towards the borders. Many of them were caught by the Germans and were beaten dreadfully. Sometimes they did let people cross over to the Soviets. After this, the Germans announced that Jews who wanted to go over to the Soviets had to register at the magistracy and for a payment of 5 zlotys they would receive a confirmation.

When all the Jews with confirmations came to the designated place, in the villages of Horodok–Vedenke[8], next to the Bug, the Gestapo encircled them, took away the better things, and whipped them.

On Friday, the 1st of December, 1939, Yosef Sher and David (Shmerl's) Sher went around from house to house, sent by the magistrate, and announced:

– Tomorrow, Shabbat [Saturday, the Sabbath], at 7 in the morning, there will be a registration on the Vigon[9] of all the men aged between 15 and 60 years. Whoever does not come will be severely penalized.

People sought advice, it was not known what this meant, but no terribleness was foreseen. Therefore even those younger than 15 years also ran to that place to see what would happen, perhaps also to register themselves, they would in any case soon also be considered adults …

So they came to the place, and they were overtaken by fear. They saw immediately that already they would not be able to go back, they were encircled by a cordon of S.S. men and Gestapo men. For several hours they stood in the place. Afterwards came the district administrator, the mayor, and the magistrate–secretary, Shumovitch. They placed the Jews in two rows, the district administrator spoke in German, and one of them translated to Polish:

– All who find themselves in this place are subject to a war order. Anyone who tries to run will be shot as a war criminal. Money, documents, and valuables – must be given up. Each one can leave for himself 30 zlotys. For not carrying out the order exactly, one will be shot without a trial!

After this, the S.S. men and the Gestapo men went around with sacks and collected all the valuable things.

Then a list was read out of all those who were supposed to have presented themselves. It emerged that more had presented themselves than were in the list. A selection began. Those who were younger than 15 years and older than 60 were promised that they would soon be freed and would be allowed to go home.

[Columns 615-616]

Meanwhile, the Germans began bringing from all sides captured Jews, ragged and half–dead. We did not know who they were and from where they had come. From a distance, from the town, we could hear the wails of the women and children. It was then that we first began to conceive that something bad could happen here with us.

The district administrator and the S.S. meanwhile were making photographic recordings, so that they would be left with a memento. After this they ordered us to line up two in a row, but for one to keep a distance from the other, and under threat of death we were forbidden from speaking.

Between 11 and 12 noon, the march began. By the side of the marchers the S.S. drove along, and they held machine guns in their hands.

There were marching about 2,000 Jews from Hrubieszow and about 3,000 other Jews. Some of us managed to see glimpses of our wives and children, who would not stay away, despite the threats that they would be shot.

To where were they leading us? Looking away from the threat of death [for speaking], we were made aware by the foreign Jews that they were from Chelm, that the “registration” there had already taken place a day earlier, and that immediately after they were marched out of Chelm, next to the forest, the Gestapo took the leaders of the town out from the rows, led them into the forest, and shot them there. The remaining Jews were brought towards Hrubieszow, were packed into Moshe Vorman's rag warehouses, and were kept under guard there for the entire night. They were watched so that none of them would be able to sneak out and thereby make those in Hrubieszow aware before it was time.

Did we dare to think what would happen to all of us? Where were they taking us?

We had already walked several kilometers and we could still hear the weeping of our wives. As we were later made aware, Efraim Deitch's daughter was shot when from the distance she shouted out:

– Father!

At the village of Holotishenes[10], 4 kilometers past Hrubieszow, we saw (although we dared not look around) how the S.S. were leading Jews from Chelm to the side who could not go on any more. After walking on a little way, we heard shots. The back rows later informed us that they threw the Jews half–alive into a pit. They drove us specially through large areas of mud, in order to wear us out. The exhausted were shot by them.

By Saturday evening we had walked to Kolonia Cichobórz[11]. There they held us until it grew dark. Later they drove us through large muddy areas and waters. From time to time the S.S. threw on projector lights and afterwards the darkness became thicker.

Many fell in the water and mud and could not get out; we heard calls for help and shouts. In the darkness we trod in the mud and tried to avoid the S.S. escorts with their revolvers, but not everyone was successful in this.

After we had crossed the muddy swamps, we received an order to sit ourselves down in the middle of the road and spend the night there.

As we lay there like that, we summed up between us the total of the first victims: the dayan[12], Hershel Blumentzveig, Naftali Shtern with his son, Berish Finkelshtein, Shlomo Berger, Yankel Shofel, Israel Mordechai Tzukerman, Leizer Nissel, Nachum Valdman, Yehoshua Yortzeig, Yissachar and Moishele Kozhuch. We did not know any more names. From among the Chelm Jews, many more were shot, because they were more exhausted.

Rain began dripping and for a whole night we lay there thus, in the mud. At 8 in the morning our death march began once again. Already then we saw puddles of blood from those who had been shot. They also took healthy people out from the rows, ordered them to lie down with their heads down, and shot them. Whoever did not carry out the order immediately, received a beating to the head with a revolver.

In this way they drove us on for the second day, until we came to the village of Dlobitchov[13]. It was around 2 to 3 in the afternoon. There they divided us up into two groups. Then they ordered us to lie on the ground, with our heads down. We were sure that now they would shoot us all. They did indeed fire a few shots, to frighten us, but then they ordered us to pick ourselves up and told us to listen obediently to the order:

– We are being marched to the Russian border. One group through Sokal, and the second through Belz.

We quickly weighed up with which group it would be better and closer to go, and we ran from one group to the other, even though this was forbidden.

It turned out that we were to go in the group that was bound for Sokal. But first, now the horrors began. They drove us through a narrow path along the side of the road, in which water was flowing strongly. Only two people could go in the water–pit.

Thus we went on further, regularly seeing rivulets of blood from those who had been shot. A few lay face up, with their teeth ground together, blood snaking from their mouths. It was shocking to look at. Everyone felt that soon it would be his turn to be shot. As if all this were a joke, we could hear from a distance how some of the peasants were shouting to us:

– So good on you, Jews![14]

Those spurring us on [the Germans] ordered us to speed up our pace, and routinely called out with derision:

– You are tired, come here![15]

In the village of Norina[16] we were driven into a hall, where we stood one crammed against the other. We were guarded by Ukrainian militiamen. Throughout the entire night they fired shots, so as to keep us in fear.

On the third day [of the march], Monday, the S.S. drove us out of the hall, beating us with sticks. Despite this, we felt pleasure in that little bit of fresh air, outside. They ordered us to stand three in a row and gave us water to drink.

Meanwhile the S.S. once again carried out a selection, standing the young people at the front and the older ones behind. And the march began again. We were led along a badly paved [uneven] road. When we stopped, one person was not allowed to hold on to another, and also we were not allowed to lean on any stick.

They immediately ordered us threateningly to hurry up and again the shooting was renewed. We heard how the S.S. men asked each other:

– Comrade, how many have you killed already?

The pace of the journey rose, the fear also. We soon threw off as many clothes as we could, [and] took off our shoes, so that it would be easier to run. Now, at the slightest wobble, one would be shot. Fathers left their shot sons lying on the road, and the reverse; a brother left a shot brother lying there; even crying was not shown.

When the S.S. men took Itchele Levenfus out of the row, in order to shoot him, his son ran alongside and begged the Hitlerites to shoot him instead of his father. They shot both together, the father with the son. After this the S.S. man called over Shmuel Hersh Kupershtok. He began to say, “Hear O Israel!”[17] and in the middle of calling to God – was shot.

Then came the turn of Noach Vertman. He

[Columns 617-618]

immediately put up an active resistance. Managed to give a push and a slap to the S.S. man.

Around 2 in the afternoon we came to the village of Nishmos[18], 5 kilometers from Sokal. We were already a small, exhausted group. They counted us. An S.S. officer came on a horse and took a report of the “work” that had been done and how many were still left. The officer did not like the number of those who were left and ordered:

– Comrades, this is still three Jews too many.

They took out three more Jews, among them Avraham Feler, and shot them.

After this, the officer turned to us and said that from here on no one else would be shot on the way. We would have to cross the Bug, the water there was not deep, and we would have to keep ourselves in order.

But after this it was indeed the same officer who shot again. The last person shot was a 15–year–old boy, a son of Pinchas Toker's, as he ran to catch a piece of bread that the officer threw to him.

They ordered us to sing. Singing we came to the Bug bridge. The officers explained that we were going to cross the border to the Soviets. Once across, we should march with our hands raised and call out regularly:

– Long live Stalin!

The Germans shot in the air and we moved on to the bridge, with our hands raised and with calls of: Long live Stalin! We were twitching with joy – now our journey of suffering and torment would end.

And then there we were, at last, on the other side, with the Soviets. The soldiers looked at us with sorrow, they saw how we were torn, wounded, and exhausted. They presented us with hot boiled water[19]. We sat down and they comforted us that we would soon be freed.

From the group that had been sent to Belz, many were shot along the way.

On Monday at 2 in the afternoon we came to the border, on the Soroka River. They held us there until the evening, then ordered us to cross the river. We all entered the water and ran.

The Soviet soldiers began shooting in the air, but we all ran further, not looking back at the shooters. The water already reached our throats and we barely made it over to the other side.

The soldiers on the other side of the river halted us. We stood there, soaked through and trembling. We had to wait for a decision from the Soviet border watch. The cold was bitter. Our bodies became stiff. Meir Vaksman, Yankel Ayl, and others were frozen.

At 2 in the morning the Soviet border watch reported to us that we had to go back. And they led us back to the bridge, to the S.S. men.

The Germans led us into a number of empty houses.

The next day the S.S. men came and ordered us again to cross the water to the Russians. We ran off. A small number submitted themselves and went over to the Soviet side, and some took off for home.

Out of more than 5,000 Jews who set out on the march, 700 to 800 Jews remained alive. More than 4,000 Jews fell on that death march from Chelm and Hrubieszow.

We cannot end the giving of our testimony without a curse on the Nazi murderers and a Kaddish[20] for the fallen martyrs.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Eliezer Aharon Zommer – San José, Costa Rica

Translated by Miriam Bulwar David–Hay

|

My father, who knew how to write his letters from the Torah[1],

In his Polish letter he prayerfully,

My father's last letter was one groaning “oy,”

My dear children,

Read my letter quietly, with common sense,

You are certain to remember our last Torah,

My heart is cut up inside me, worse than with a sword,

Be well, my dear children,

Read my letter quietly and with common sense, |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Hrubieszów, Poland

Hrubieszów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Sep 2022 by LA