|

may his memory be a blessing

Personalities

and Folksy Characters

|

may his memory be a blessing

|

|

[Columns 373-374]

may his memory be a blessing |

Personalities |

|

may his memory be a blessing |

[Columns 375-376]

by Yakov Shatzki, may his memory be a blessing

Translated by Mira Rivka Blum

|

From 1815–30 in Poland it was difficult to find a Jew who was more popular than Avrom Yakov Stern. His name came up often in both the German and the Polish press during that time. His aura carried with it a whiff of spice and the exotic. This quaint and religious Jew had an imposing presence with his fluency in several languages and his far–from–average knowledge of math and sciences. People would gawk upon seeing this Polish Jew, a mathematician and a polyglot, who was at the same time a paradigm of producing a harmonious relationship between Judaism and the non–Jewish world.

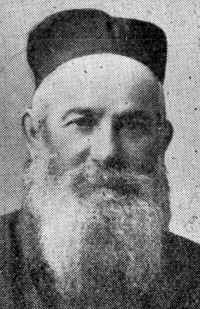

Of small stature with the face of a true patriarch, Rembrandt would have painted him with bright, cheerful eyes, a neat and tidy appearance with a long beard – Avrom Yakov Stern would attract the artists' gaze from the painting–worthy characteristics of his face alone.

In 1825 he was painted by Antoni Blank, one of the best Polish painters of portraits. In 1840 he was drawn by the artist Oleshchienski. An anonymous Polish painter immortalized Stern in a composition, where he stands with a yarmulke on his head and gives a fervent lecture at the meeting of the “Warsaw Society of Friends of Science.” The photo from the November Uprising (1930) was widely circulated in France and often reproduced. It functioned as a kind of propaganda to prove how good it was for the Jews in the short–lived but autonomous Congress Poland.

In 1835 a biographical album of famous Jews was published in Germany. Among the pictures in the book one could find a photo of Avrom Yakov Stern. The historian Jost wrote about it in a letter to Yakov Tugendhold, his helper at the Office of Censorship in Warsaw: “With great pleasure I became acquainted with the output of the mind of the famous Mr. Stern in the book, Die Berühmte Israeliten (The Famous Jews). This Mr. Stern has a brilliant mind – unless he's a complete toad, he has probably had a great deal of luck with women.”

In 1855, the great graphic artist, Jan Pivarski, made an engraving using Blank's portrait and added a short biography on the front of the picture. That picture was very popular in Poland and was hung on the walls of many Jewish and Polish homes.

As mentioned earlier, much was written about Avrom Stern during his lifetime. The appearance of an autodidact who doesn't just go away to join the “non–Jews”, though he could have, was impressive. Stern, who did not just assimilate into the wider world as was the case with Salomon Maimon and the Maskilim of his generation, a religious Jew fluent in several languages, who stayed a Jew through and through, in his dress and on his face, this great scholar – must have stirred up a mixture of astonishment and amazement. In Warsaw people used to tell all kinds of stories about him. This particular mathematician was prominent in political affairs and a legend in his own lifetime. We used to tell a story about how the Grand Duke Konstantin, the Governor General of Poland, was traveling in his coach and saw Stern from afar. He asks the driver to stop, calls out to him, and asks him to sing “Ma Yafit.”[1] The proud Stern replies to him in French, that he won't do it. Then the Russian Governor General then recalls that the last time he was in Warsaw, this was the little Jew from the Polish academy. So of course he doesn't need to sing for him.

In the dusk of his life, Stern used to tell his later son–in–law, the “Litvak,” Hayyim Selig Slonimski (1810–1904) certain episodes of his past. When he was in Germany (in 1813), in order to demonstrate the calculator that he invented, people looked at him like he was some kind of mysterious creature.

“I was with them,” Stern spoke about the German intellectual elite, “they wear short pants with socks, whereas I hid my socks under my pants, because they say that outside of Israel you shouldn't dress like that. They looked at me as if I were a wild creature – something not of this world! I want to explain to them my ideas on calculating, but they can't hear me, because they're just staring at me. Are my beard and sidelocks more important than multiplication? Is my yarmulke more important than my method for quick calculation?

Stern's Biography

Avrom Yakov Ben Chanoch Chenech Stern was born in 1768 in a small town, Hruibeshow, in the area of Lublin, not far from Zamość. Regarding his family and the years before he came to Warsaw, very little is known. Supposedly his parents were very poor. The son studied watch–making in Zamość. He studied for many years at the House of Learning. During his studies he made a name for himself as a prodigy. The surrounding Polish noblemen were amazed by his French and Polish. He also knew German, as his preparation of official documents can attest, but that fact did not even seem to be a noteworthy observation. Stern said that when there was a war between Poland and Austria in 1809, he was active on the Polish side for his proficiency in the “two languages”: the former (Austrian) and that of the new government. It is unfortunate that he does not elaborate on his precise role – it's quite possible that he was a translator. The property around the town of Hruibeshow came to be used by the famous Polish statesman, the Priest Stanislaw Staszic (1755–1826). The priest became very interested in the Jewish scholar and watch–maker, and while Stern was showing him the roughly–sketched designs of his calculating machine, Staszic sent him on his own dime to Warsaw with all the necessary recommendations, so that he could complete his training in mechanical engineering. That same year, Staszic made it possible for Stern to make a demonstration of his calculating machine for a meeting of the Mathematics section of the “Warsaw Society of Friends of Science.” The demonstration caused quite a sensation. The society published a communiqué in German. The Polish press wrote a great deal about the “Kaftan Jew,”[2]

[Columns 379-380]

the country bumpkin that speaks and writes in perfect Polish and who sent in among his papers in Polish a popular explanation of his complicated calculating machine. The reports from the Polish press, as well as that of the German communiqué, were both printed in the same German publication. Stern was invited to demonstrate his findings for the Scientific Body of the Exterior. He visited Brody and Lviv, where the Maskilim prepared a warm welcome for him. From Galicia, Stern departed for Germany. No one is quite sure of his exact route. It seems certain that he visited Halle and Furth. Unfortunately we have not been able to find many details regarding this noteworthy trip. Stern himself years later shared some of the details with his son–in–law, Hayyim–Selig Slonimski. It was difficult to discern the sensationalist elements of his accomplishment from the main points of interest. This “wild creature” apparently left a lasting impression on non–Jews, even though the German Maskilim also extolled his praises. Stern was also in Furth, in order to see the local Yeshiva which had made a name for itself. Years later in collaboration with a Rabbinical School in Warsaw, he recalled his visit to that Yeshiva and used it as an exemplary model. Undoubtedly Stern would have met the head of the Yeshiva, the very old A. Yolid Poilin, who since 1789 was the rabbi of the old and well–known community. Both of them had a lot in common, they both struggled with the politics of the “enlightened” Jews. Stern once said that during his trip, he was advised to stay abroad. Yet he didn't take their advice. They promised him gifts and a significantly improving living situation if he were to stay. However he did not want to leave his “homeland”, as he referred to it. His sense of attachment to his place of origin was strongly developed. This pious Jew would take advantage of every possible opportunity to talk about Poland, which he described as “my homeland.” In this respect, however, he was not the first. Even the enlightened Jews made similar statements. It was common enough to recall the case of his fellow resident of Hrubieszow, Dr. Yakov, or Jacque Kalmanson (died in 1811), who declared himself a Polish citizen. He made this declaration however in French, because he did not know any Polish. Stern was the first religious Jew who openly declared Poland was his “homeland.”

Heavy Spirits

With such feelings, Stern came home. His protector and financier, the priest Staszic, welcomed him as a Jew which made a good name for Polish science while abroad. Stern was able to meet the powerful senator, Nowosilcow, who loved to bestow favors, even to those who didn't deserve them. He took it upon himself to introduce Stern, the “Jewish mechanic,” to Alexander I. That was in 1815. He was so impressed by the “Jewish curiosity” that spoke French, that he ordered Stern be paid a yearly salary of 200 Talarn (1,200 Polish Gilden).

That stipend alone was not enough for Stern to make a living. His wife, Sheindel, was the daughter of a wealthy scholar from Opoch, named Lipshitz, and as such, she probably could not forget those “good years” in her father's affluent household. They had five children together. Stern didn't have any other source of income except for the occasional private lessons, mostly for non–Jews, whom he taught math and astronomy. The subsidy that he received ended up going entirely towards the materials he needed to continue his findings, among which was included a faster plowing machine, which received keen interest from the Polish agricultural sector.

In 1817, Stern visited the city of Vilnius at the same time that Alexander I was also there. Thanks to the nobleman, Adam Czartoryski, the curator of the Lithuanian Region of Education, Stern was introduced once again before Alexander I. The czar listened to Stern's concerns and ordered that his salary be raised. When he came to collect his payment, not even Novosiltsov could help him. At that point Stern began to be overcome by difficult moods that even he couldn't fully grasp. His Polish and Hasidic friends did not want to help, largely because the hated Novoslitsov was involved. Staszic, the conservative, anti-Semitic publicist, nevertheless continued supporting his protege. True, in 1816 he wrote that we need to settle Polish Jewish in Crimea or Bessarabia in order to “rescue” the Polish peasants from the Jewish innkeepers and the Polish merchants and tradesmen from “terrible competition.” He also thought that he could designate a few of those Jews who weren't harmful. Stern as such was considered one of those “useful Jews.” In him he saw first and foremost a Jew that could help in the development of the Polish technical sciences. As a priest, Staszic had more respect for a religious Jew than from the other enlightened Jews, many of whom he knew personally quite well. Stern was for Staszic, the Physiocrat, an important person because of his plans for a new plowing machine. In 1817, five years after the first report, Stern completed another project for a new calculating machine. As chairman of the Polish Society of Science, Stasciz set a date when Stern was supposed to give a report. A few of the members however were not happy about it, and thus requested that Stasciz remove his name from the list of speakers. They failed to include Stern among the official members of the organization in one of their resolutions. As a result, a group of liberal members wrote a letter of protest against their anti-Semitic colleagues. One of them, Count Alexander Hodkevich, a renowned chemist, wrote about the matter to the secretary of the society, Stanislaw Czaranocski: “The decision (not to admit Stern) will only show that we have no integrity and that we are ruled by deeply rooted prejudices. Regarding prejudices, I want to say that clothes aren't what make a man – on the contrary. Above all, educated people should distance themselves from that which is politically fashionable, and moreover not do that which is not decided on by group consensus. We should not be interested in Stern's position regarding Jews, rather we should follow what our own ordinances dictate, that is to say, spreading light among the people and bringing together all educated people in a common body without discriminating based on faith.”

Staszic took it upon himself to break the opposition, which was not really against Stern himself, but mostly against his Jewish clothing. Finally he made his presentation. According to the accepted levels of membership, Stern was accepted initially in 1818 as a member without rights, in 1821 as a member with passive rights, and in 1830 he achieved full, active rights.

[Columns 381-382]

“In Warsaw, there was a light emanating from Stern's halo.”[3] Wrote a Polish contemporary in bold letters.

He becomes a member of the Bureau of Censorship for Jewish books and is considered the representative expert on all Jewish matters.

His role in censorship was more of a decorative one. Novosiltzov considered him to be more an expert on Jewish books than on censorship. In reality, Stern had a cultural organization that the radical non–religious Jews did not like. He was mild on academic and Maskilim texts but carefully strained (reviewed) Hasidic texts. Later he became so permissive, that the members of the government began to think that Stern himself was harmful because he was “sympathetic” to the “dark and fanatical Jews.” He managed to avoid the publishing of a Bible that was made via missionary efforts and aimed at Polish Jews. Stern wrote that since Jews have their own Bible, missionaries don't have to worry about the Jews.

Stern became the representative face of the Jewish community, without which there wouldn't have been any cultural celebrations in Warsaw.

In 1829 in Warsaw, we laid the cornerstone of a monument for Nicolaus Copernicus. Avrom Yakov Stern was also among the guests who were invited to inaugurate the celebratory act. At this particular moment, he signed his name using Hebrew letters. He explained that his intention was that if the act should ever be dug up, then at that moment one would see that Poles had been liberal and tolerant to Jews, as evidenced by the fact that they had invited a Jew to take part in a national Polish holiday.

Stern Unmasks Plagiarism

The national concept repeats itself throughout Sterns writings. He was concerned primarily with issues relating to territory – and not with ethno–national interests. Stern considered himself a Polish Jew and thought that everything related to Poland should interest a Jew who is born in that land. Quite quickly, Stern received an offer to formulate this idea in a more demonstrative manner. In 1819, Warsaw University invited the Italian priest Luigi Chiarini (1789–1832) as a professor of Hebrew. Chiarini was a bitter anti-Semite, who even believed in blood libel. He was also elected president of the censorship committee for Hebrew books, and as such Stern had to work with him.

In 1829, Chiarni published a Polish translation of his Latin–Hebrew language dictionary. It was a terrible job – plagiarized from several other lexicographers. Among the educated Poles, there were not that many Hebraists at the time. One of them was the young Joachim Lelewel, who turned to Stern with the request that he share his opinion on the worth of that Italian's compilation.

Stern however was unable to openly take any steps against his “boss.” Instead he hid himself via a pen–name, “a lover of literature.” The handwritten expert opinion became a small book of 116 pages, where Stern demonstrated how Chiarni's dictionary was plagiarized, and in addition, that there were 900 errors in it.

The social position that Stern took in his introduction (“Our dear literature”) and the impressive summary of Chiarni's ignorance made a strong impression in Warsaw. The Warsaw Professor who was brought all the way up from Italy was demonstrably unmasked, and not from a secular Jew, but from a pious one. The liberal, educated Poles gave strong words of praise to Stern's publication. They especially liked the Polish explanations in the introduction, which seemed more in the style of a non–religious Jew. Lelewel wrote to Stern regarding his critical review, that Chiarini's “general compilation brought shame upon our generation.” Chiarni subsequently published an open letter asking that the author reveal his name. Stern did as he requested. Then Chiarni summoned Stern to a “literary duel”, that is, a public debate, which Stern accepted. However, when the location of the debate was set, Chiarini failed to show up. This raised the value of Stern's stock. In the circles of the Polish scholars, people began to think of Stern as the emancipator of Polish scientific honor.

In the meantime the November uprising broke out. The revolutionary Parliament abolished the Censorship Office and Stern was left without an income. A few good friends helped him out. Although Stern himself did not get involved in political matters, his two sons both served in the city's national guard. Regarding his character, his assistant, Yakov Tugenhold remarked that he did not go with the flow.

After the uprising, the Office of Censorship was eventually reopened, and Stern was able to work again. Old friends, especially the Polish astronomers and mathematicians of Warsaw, secretly supported him. In 1837, Stern received 1000 Gilden, which the Polish physicist Antoni Magier left for him in his will.

In 1836, Hayyim Selig Slonimski came to Warsaw, having recently gotten a divorce from his wife. Slonimski became a regular presence in Stern's household. Stern brought him together with the most important Polish astronomers and even helped Slonimski publish his “Toldot Hashamayim” (Warsaw, 1838) and wrote an introduction in Polish to the book.

Stern however was also envious of the young Slonimski and did not want to share with him his findings. In the beginning of 1842, Slonimski married Stern's youngest daughter, Sarah (1824–1897), and when Stern died that same year on the 3rd of February, Slonimski inherited his father–in–law's inventions. A Warsaw–based Mathematician and explorer, Avrom Stapel (1810–1880), later modified and reconstructed Stern's machines in his own name.

After his death, the government gave Stern's widow a yearly pension of 240 rubles. Their children had already been all married off. One son, Yitzchak, was a German teacher at a Gymnasium in the provinces.

The press wrote a great deal about Stern. Years later, his name was brought to life during the emigration to France. On the eve of the 1863 uprising, his life history was a symbol of “Polish–Jewish brotherhood,” and his spirit was invoked to highlight that partnership. The romantic biography was sensationalized by journalists, who were unable to bring forth any new details from his life story.

[Columns 383-384]

Stern's Cultural Ideology

The idea of state intervention in Jewish educational matters came from Stern's patron, the priest, Stanislaw Staszic. He convinced the Minister of Education, Count Stanislaw Potanski, to take an interest in creating Polish schools for Jewish children. The main goal was to create a public school for Jewish religious mentors, a kind of rabbinical school, that would become the foundation of a new Jewish cultural organization. Polish patriotism demanded that for that particular experiment, no foreign “experts” should be invited to participate in its formation.

As fate would have it, the responsibility of serving as the “historical emissary” for this project fell on Avrom Yakov Stern's shoulders. The selection process ranged from typical to sympathetic. The state officials wanted the younger Jew of the Maskilim, Yakov Tugendhold, to be more to their liking, since he represented that “progressive” ideology. That would have pleased a man such as Pototzki. But Stern was the ideal model of a Polish Jew, with an awareness of Polish geography, and a member of the Polish Scientific Academy, a Jew who followed all 613 commandments, who speaks Polish like a native, who gets along with state officials – who could have possibly been a better candidate?

Stern as such wanted to prepare a memorandum regarding the planned Rabbinical School. Without even seeking his prior consent, Stern was appointed as the director of the not–yet–existing institution.

The whole matter did not sit right with Stern. However he was requested to comply by two noblemen, plus his own patron Staszic and the Education Minister Pototzki. He accepted their proposal and sent out the memorandum. Unbeknownst to Stern, the government had already worked out their own project, and if Stern's project happened to align with theirs, then that would have been a great victory for the state. But Stern's plan was entirely different. He simply proposed the founding of a reformed Yeshiva, probably along the lines of what he had seen in Furth. His project was not accepted, but he was nevertheless appointed as director in 1826. This was even the year that Staszic died, after which Stern no longer had such an influential supporter.

The fact that in 1818 Stern had given his approval for an elementary school for Jewish children did not mean that he would give in to the creation of a state–run rabbinical school. He only accepted that school in extenuating circumstances, especially in Warsaw, where it could be considered as a path to continue on from secondary education. He made one condition: that these schools would not include any study of Jewish texts. Properly speaking, Stern stood out from other religious non–Hassidic Jews, who would not want to hear about such a school at all. In 1820 he even managed to systematically obtain a subsidy for the schools from the income of the kosher meat taxes.

But the approval for the general schools for Jewish children as a continuation to secondary school religious training was still miles away from becoming a rabbinical school. To trust the state with the formation of rabbis seemed like a pretty dangerous proposition, even when the teachers would be religious and learned Jews. Stern wasn't only wanted as the director of the institution, but also in order to teach Gemara[4]. As a temporary deputy for the committee on the “Council of Elementary Schools of the Faith of Moses,” he firmly stressed that we can't consider these schools as a substitute for a general Jewish education. He thought that Polish Jews do not need a rabbinical school, because no community is going to accept a rabbi that didn't learn in a Yeshiva and did not get their ordination from those rabbis who are authoritative in the eyes of Jews.

The government however could not distance themselves from someone who was such a symbolic figure as Avrom Stern, and as such they didn't even make an effort to find someone else as director. Meir Horowitz, a religious Jew and great scholar, was appointed as a teacher of Talmud and Assistant Director of the Rabbinical School. In practice the Rabbinical School was run by a steward, the leader of the radical Maskilim Jews, Anthony Eisenbaum (1791–1852). Stern was not a fan of Eisenbaum. During the year of 1822, Eisenbaum planned to distribute a Hebrew–Polish weekly paper, and he invited Stern to oversee the Hebrew section. Stern considered Eisenbaum as a man without scruples, and as such did not want to be a part of such a partnership. But Eisenbaum knew that Stern was more respectable than him, at least as an ideological symbol. He thought, however, that even the symbolic respectability that Stern could offer had its limitations.

Stern himself did not fully grasp that his respectability in Polish society and among the Polonized Jewish youth was first and foremost based on his seniority and life experience, because he would have a hard time impressing a scholar in a land famous for its Jewish learning. The situation was highly unusual. Stern wasn't at all involved in the Rabbinical School, but when someone came for advice in its formation, the inquiries were always directed toward him. As the Chairman of the Office of Censorship, and a known expert in Jewish affairs, and as a member of the state Jewish Committee, Stern had the moral sanction of Jews and Poles. There was a desire to show the outside world that when it comes to internal matters of the Rabbinical School, one shouldn't ask Tugenhold or Eisenbaum, but rather Stern, since the “Polish mathematician in a yarmulke” was the exclusive expert. This was an obvious political tactic that the naive Stern just didn't get.

Years before the Polish Uprising of 1830, there was a political trend that was starkly anti–liberal. Liberalism in general, and particularly pedagogical rationalism, was seen as one of the greatest dangers facing the country. Along with the growth of the political backlash, Stern's social capital grew, and not as a result of the current political climate, but as a result of the pedagogical situation. Stern really liked the writings of the far–from–friendly publications, which wrote that a “Jew with a beard is much better loved than a Jewish priest.”

In 1821 the former radical, Ksaveri Klemens Shaniavski (1764–1843) was voted as the Director of Censorship and Public Education. Shaniavski wanted to strengthen the Catholic component of Polish education. Shaniavski in any case defended traditional Jewish schooling, though he himself was far from being a philosemite.

The educational philosophy of Shaniavski and Stern merged in their modern approaches. Stern thought that education is good for exceptional people. Knowing the official language is simply a practical matter, and in any case should be limited to individuals or groups that need it for professional purposes. Shaniavski, the Catholic version of Stern, seconded Stern, the Jewish Shaniavski. After the uprising, Stern wrote

[Columns 385-386]

in a memorandum in which he stated that the Jewish youth who participated in the uprising against the “legal authority”, were mostly students from the Rabbinical school. We can't prove that there wasn't a single student from a Yeshiva that wasn't involved in the conspiracy.

Stern's legitimization of authority made him out of touch from the youth, who like Anthony Eisenbaum, saw him as a kind of Polish–Jewish symbol. After the uprising, government officials began planning to reform the rabbinical school with a more conservative bent. No significant changes were made during Stern's tenure in connection with the rabbinical school. In a memorandum taken on the 14th of August 1833, Stern clarified that it is ideal for rabbis to know the official language of the land, but they did not need a rabbinical school to accomplish that goal.

That which is learned in the rabbinical school, wrote Stern with irony, is good for someone who wants to become a writer of literature. The students of the rabbinical school became riled up by the uprising not as a result of learning a page from the Talmud, but because they learned about the history of Rome, which is full of revolutions. Of course, he is in favor of a rabbinical school with a broad curriculum of rabbinical studies, with a bit of secular learning, such as Polish, German, and math. But for such a rabbinical school, we're in need of a different teacher, even for the non–Jewish studies. If the state is unable or unwilling to complete the task, then it would be preferably simply to convert the rabbinical school into a pedagogical preparatory school, under the condition that Jewish studies not be taught there.

Stern, however, was not among the stringently orthodox of his time period. He had to make certain concessions, small ones, modest and quiet, for the sake of practical necessity. For most of the Orthodox Jews however he was considered too much of a “heretic.” In his heart, Stern was half–Maskilim, if only from a logical point of view, whereas, as a wider movement, it frightened him. His weakness for the ideas of the Maskilim was expressed in his bad poetry, spontaneous odes, rhyming introductions and seals of approval, tombstone engravings, charades and riddles – in a word, the well–known rhyming acrobatics that was characteristic of the Maskilim followers in Poland. He even used to read the hackneyed fruits of his muse in the literary “salons” of Warsaw's Maskilim. In the palace of Hebrew poetry, Stern was no “star”, even though that was his pen name. Among the scholarly Maskilim, he had a lot of friends. During his tenure at the Office of Censorship, he gave his approval quite liberally to works by Maskilim, even though he was very strict with Hasidic books. Stern also had a high opinion of the “Science of Judaism.”[5] In 1820, an anonymous Polish historian turned to Jewish studies in Poland and helped gather material regarding the country's Jewish past. Stern called upon himself to continue this work. In 1823, he published a Polish translation of Nathan Hanover's Yeven Mezulah.[6] The same translation was later employed by the historian Joachim Lelewel, with whom Stern was closely acquainted.

This translation here – explains Stern in his introduction – is my debt to the “homeland's historical sciences,” just as the critical review of Chiarini's failed dictionary played tribute to “national” culture.

In this particular point, Stern stood out as different from his peers. There were greater scholars in Poland than Stern, but a religious Jew who knows several world languages and can also write in them – other than him, there wasn't anyone else in Poland who fit that description. The Maskilim Jews knew a lot less than Stern about the current trends in Jewish Studies. His approach to secular matters was purely utilitarian, and for that reason he found favor in the eyes of religious Jews. Along with the Maskilim, he found the studies of the secular world to be useful, but on an individual basis. However unlike the Maskilim, he did not compromise so easily with non–Jews on Jewish matters.

When Ephraim Finer (1800–1880), also a Polish Jew, came in 1836 to Warsaw in search of financial assistance for his planned German translation of the Talmud, Stern befriended him. In 1837, when negotiations were being made by the Office of Censorship to give a sum of money for publications, Stern supported the idea of translating classical religious Hebrew works into Polish. But these were constructive projects. He also, however, fought against Mendelson's Bible with commentary as a textbook in the Elementary School for Jewish children.

In time, Stern became a stumbling block for the Maskilim, although he did win over a number of Misnagdim,[7] and with them he became acquainted with the right wing of the Polish Haskala.

Stern's activity in the Office of Censorship did not find favor in the eyes of the great nobleman Konstantine, who had enjoyed stopping him in the middle of the street to have a chat in French. He sharply criticized the “wild Jew” who allowed the publication of “works of fantasy by sinister rabbis.” In time, Stern's censorship activity existed more or less solely on paper. The true censors were simply not supposed to be “bandits,” whereas the jovial Stern would ask as a favor that a particular book be allowed through, especially when one of his rhyming introductions was a part of it. It even came to pass that if a book happened to have a few empty pages, that the author or publisher would commission Stern to publish a few of his poems there. However when a Hasidic work showed up, then Stern took it upon himself to be the Jewish “bandit.”

As a member of the Jewish Committee and as a censor, Stern fought against German printing production. A reformist school of thought permeated the studies of Jewish religion and offended the religious Misnagdim. He also fought against local authors who attempted to Christianize the Jewish religion. In other cases, he was more of a progressive, like most Misnagdim in Poland. When it appeared that in 1841, German–Jewish journals would be allowed to enter Poland, Stern proposed, together with Yakov Tugenhold, a plan to publish such a journal in Polish. The Office of Censorship did not agree with the plan.

In his heart, Stern was a Misnagid with literary tendencies that were stronger than his political–ideological ones. Politically he was an anachronism, a typical product of an antiquated Poland. He had his nobleman sponsor, Stasciz. The noblemen were always correct, and so of course he took their side. Stasciz was really an anti–Semite, but not regarding “his Jews”, and Stern was one of them. He wasn't a “true philosopher”, as the Jew Holenderski wrote about him. Even when specifically asked by important scholars of the time, he didn't adhere to any particular school of thought, even though his son–in–law Hayyim Selig Slonimski wrote that he loves the philosophy of mathematics.

Politically, Stern was naive and primitive. He was no guiding force, and did not even pretend to label himself as such. In the various commissions for Jewish affairs, where he was invited to participate, his role was more decorative than practical. He hardly spoke up, but at the same time, people were enchanted by his Polish speeches.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Shmuel Yosef Fin

Translated by Yael Chaver

Rabbi Avraham Ya'akov, the son of Rabbi Khanokh Henikh Shtern, was born in Hrubieszow, Poland, in 1768. While still a child, he was remarkably gifted, especially in mathematics. However, his impoverished father could not afford to educate him and ensure his future, and the boy learned mathematics on his own as well as he could. He learned watch making as a profession.

When he grew up, he became renowned in his small town, and came to the attention of the great and wealthy master Staszic, who had then purchased the town of Hrubieszow as his own estate. Once Staszic came to know Avraham the Jew, he became fond of him and sent him to Warsaw for an education; he also supplied room and board.

Shtern was successful in learning all the areas of mathematics and mechanics, as well as Polish, German, and Latin. He mastered these languages, and spoke the local language as well as the learned local scribes and experts did. His sharp mind enabled him to invent various machines. One of the most famous of these was the topographical wagon, which logged distances in numbers, and also produced a map of the area. The greatest of all his inventions was the calculating machine, which could calculate addition, subtraction, division, and multiplication, in whole numbers and in fractions.

The incentive for this invention was as follows: the official in change of the treasury, in Vienna, checked his records and found that the deposits were several millions short. He committed suicide, for fear that he would be accused of concealing the amount. When the records were examined after his death, it became clear that there was no shortfall; there was only an arithmetical error.

This sad information saddened Shtern, who then decided to develop a calculating machine that would produce precise numbers, and avoid all chance of error. He spent eight years working on this machine, at a cost of ten thousand rubles, until he succeeded. He completed his work in 1815 and presented it to Staszic. The latter was amazed at Shtern's talent, his incisive mind and perseverance, and could hardly believe his eyes and ears.

Once he had heard the explanations of the machine's capacities, he decided to suggest that his favorite, Avraham, be elected to the official Warsaw Society of the Friends of Science. This proposal was accepted, and Shtern entered the Society's hall with his calculating machine and displayed it to the greatest ministers, princes, nobles, and scientists of the time. He explained the machine's construction and calculation abilities, using a rolling handle and internal wheels. The onlookers were amazed; they applauded and cheered loudly. From then on, the great men of Poland and the scholars of Warsaw visited him in his poor home, and enjoyed his company and conversation on matters of learning and science.

Shtern did not exploit his fame and new friends to improve his material conditions, but continued to work at his trade. Neither did he change his clothing, shave his large beard that covered over his body, or change his way of life to impress his rich guests. He was happy with his meager livelihood and did not seek ways to improve his finances. He never told his influential admirers that he barely made a living, and they continued to love and admire him.

Prince Czartoryski, who was famous for his mathematical expertise, admired him and invited him to stay in his palace. His Jewish cook was ordered to cook kosher food for the guest, who was known as an observant Jew. Shtern stayed in the palace for three months, and was treated as a friend and brother. In 1817, when Prince Radziwill was visited by the Emperor Tsar Alexander I, he ordered Shtern to be brought to the palace. His Majesty, who was famous for his mathematical expertise, conversed with Shtern for more than two hours. At the close of their conversation, His Majesty asked, “What else are you thinking of inventing?” When Shtern replied, “I am too weary to think,” the Tsar put a hand on his shoulder and said, “Stop worrying. I will take care of you.” And His Majesty promised to provide Shtern with an annual gift of 330 rubles, throughout his lifetime, and kept this promise.

Avraham applied the high honors bestowed upon him not for his own benefit but for the benefit of his brethren, and conveyed their needs to the highest officials and nobles. Thanks to his efforts, Tsar Alexander allowed the Jews to avoid conscription into the army by paying a ransom. When Tsar Alexander was in Warsaw in 1818, Shtern suggested that a rabbinical school be opened in that city, and preparatory rabbinical schools be opened throughout Poland. In 1825, when the government created a ministerial committee for writing new schoolbooks, he established a committee of Jewish notables, which he headed. The program he proposed was accepted and implemented. He was also appointed to supervise improvements to the schools; and appointed director of the rabbinical school. Shtern, however, refused to accept the position; he did agree to supervise the school, and became the official censor of Jewish books.

From that time on, his financial situation improved, and he did not need to work as hard. He left no property, except for many books and manuscripts (in addition to his scientific expertise, he was a Talmudic scholar and wrote elaborate Hebrew poems). He published the booklet Rina U-Tefila, containing the joy expressed by Polish Jews on the occasion of Tsar Nikolai I's coronation in the royal capital of Warsaw.[1]

He also gave an endorsement, in the form of a poem, of the book Toldot HaShamayim by Khayim Zelig Slonimski (whose daughter he later married).

He died in Warsaw in 1842, at age 73. His gravestone bears an accurate account of his personality and work.

Keneset Yisra'el, Warsaw, 1847.

[The following text is in a frame, as memorial text.]

Avraham Ya'akov Shtern (son of Khanokh Shtern) (1768-1842), was a native of Hrubieszow; he was self-educated, a mathematician, and inventor of a calculating machine; a member of the Society of the Friends of Science in Warsaw, and director of the Rabbinical School.

Translator's Footnote:

by S. Z. Ya'avetz

(may his memory be for a blessing)

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

|

| Rabbi Yisra'el Isser Ya'avetz (may his memory be for a blessing) |

My father was born in Grodno, to his father Yosef Me'ir Ya'avetz (may his memory be for a blessing) and his mother Sarah Hadassah nee Epshteyn (peace be upon her). Her father, Rabbi Meshullam Zalman Epshteyn Halevi (may his memory be for a blessing) was an important figure in Grodno, and a great scholar. His father-in-law, Me'ir Epshteyn (may his memory be for a blessing) was a wealthy Grodno resident.

My father's father, Yosef Me'ir Ya'avetz (may his memory be for a blessing) was a great scholar. He did not want to be a rabbi, and chose to become a preacher on matters of morals in Warsaw. Most of his time was spent translating the following into Yiddish: the Mishna, Ein Ya'akov, Midrash Rabba, Rashi's commentaries, Khok Le-Yisra'el, and other books.[1]

Yosef Me'ir was the son of Shmuel Yitzkhak Ya'avetz, a major figure and one of the wealthiest persons in Vilnius. His scholarship was described by his father, the great Rabbi Moshe Ze'ev Ya'avetz (may his righteous memory be for a blessing), the head of the Bialystok Rabbinical court, who mentions him in the introduction to his book Agudat Ezov. Shmuel Yitzkhak Ya'avetz knew French well, an unusual accomplishment for observant Jews of the time. In his book, Mar'ot Ha-Tsov'ot, he details his lineage back to Rabbi Loew of Prague.[2]

History of My Father

My father grew up in the home of his grandfather, Meshullam Zalman Epshteyn. When still a child, he began studying in the Study House, without the guidance of a teacher. At the age of thirteen, he studied with Rabbi Nakhum the Righteous for six months. That was the last time that he was taught by another person. Thanks to his gifts, he was at home in the pages of the Talmud and the abundant commentaries, and became a prolific religious scholar.

Following his marriage, he lived at his in-laws for eight years. His father-in-law placed a three-room apartment at his disposal, and he continued to expand his Talmudic knowledge. My mother (peace be upon her) was an observant Jewish woman, gentle, kind, and generous. She loved my father and helped him to devote his time exclusively to studying.

In 1888, my father was ordained as rabbi by the great Rabbi Yisra'el Isser Shapira, head of the rabbinical court in Miedzyrzecz, and the great Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitshik, head of the rabbinical court of Brest-Litovsk. He moved to Kovna[3], where he was ordained by the great rabbi Yitzkhak Elkhanan Spektor, head of the local rabbinical court. Ordination by the greatest rabbis of Russia influenced him to devote his life to the rabbinate.

His first position was in Piszcz.[4] After about five years, he decided to move to Kowel, and seek a rabbinical position in a large city. His father-in-law, Ya'akov Aharon Antin, also returned to Kowel, to continue his work on the railroad stations of the Tambov-Saratov line; he became very wealthy as a result of this position. When my father came to Kowel, his father-in-law was busy constructing the buildings of the liquor monopoly of Volhynia. He expected to gain riches from this business as well. The mood was elevated. My father and his family received a four-room apartment on the second floor of one of the structures in the courtyard. My parents (peace be upon them) had two children, me and my younger brother Shmuel Yitzkhak. We ate with the family of my grandfather, Ya'akov Aharon, in his home. My grandfather was then about 76, and was very impressive. His height and upright carriage, handsome features, flowing white beard, and penetrating look spoke of his patriarchal position, and induced respect. He was a Chabad Hasid, and my father was a Misnaged, yet this did not cause any friction between them.[5] My grandfather was proud of my father's learning.

My father was not an active opponent of Hasidism. He was disinterested in it and did not attack it. He found it meaningless; its language was halting, and its Rebbes uninspiring.[6] He was not enthusiastic about customs such as saying the Shema prayer at unsuitable times, drinking in the synagogue, storytelling, dancing, Rebbes who were paid for their prayers, charms, amulets, miracles, and meager study of the Talmud. He rejoiced in the great scholars, Jews who studied the Talmud and whose way of life followed the Shulchan Arukh.[7] They were the example that he followed.

My father was a man of truth. His words came from the heart; he was also a man of peace, and avoided arguments about Hasidism. He did not want to join this debate, yet did not conceal his opinions. He did not regard Hasidism as the only way to strengthen Judaism. In his thought, he compared the Hasidic Rebbes to the great scholars, the popular Rebbes to the great scholarly rabbis, and the distance between Hasidic Rebbes and their adherents to the approachability of the rabbis.

His Rabbinate in Hrubieszow

In 1897, he was appointed rabbi in Hrubieszow, where the Jewish population numbered 8,000. He was paid by the government. His responsibilities included managing the registries of marriages, births, and deaths, as well as holding marriage ceremonies. The government set a small tax on unreported income, which the rabbi was allowed to accept. He renounced unofficial income; furthermore, he declined all gifts from property owners, for Hanukkah, Purim, and other holidays. On the contrary - he would contribute to others; he gave charity openly as well as anonymously to every beggar.

He handled matters of rabbinic law together with the two religious judges of the community. In arbitrations, he joined the arbitrators as a third person. If the parties agreed, he would be sole arbitrator. He would decide on complex matters of rabbinical law, and all were pleased. Everyone knew him as a man of truth, free of favoritism, and his decisions were accepted with reverence.

He devoted himself to the needs of the community, but found it difficult to issue commands. He had no means of enforcement, and had to use moral influence. For this purpose, he would convene meetings and ask for the help of the community.

Once, the butchers decided to raise the price of meat. This created a burden on the community, especially on the poor members. My father then convened a large assembly, at which all decided to stop eating meat as long as the price increase continued. All the synagogues announced a ban on consuming meat. Dishes used for meat during the ban would be declared non-kosher and should be destroyed. This ban continued for six weeks. In some cases, those who purchased meat had to destroy their dishes. However, at the end of that period the butchers repented, came to the rabbi and begged him to rescind his decree, promising not to make any group decisions. The rabbi's step was bold, as it might have been construed as a defiance of the government law against Jewish religious prohibitions. However, public resentment of the butchers was so great that the government ignored the matter. This made an impression on the non-Jewish population as well. They became aware of the moral power of the Jewish community. The matter was of religious and national importance.

Hrubieszow was a conservative town. Travel to neighboring towns had not changed in centuries. There were no paved roads or railroads in the entire area. The closest railroad station was fifty kilometers from town; even the paved road to the station was thirteen kilometers away. The soil of the town

[Columns 391-392]

and the surrounding area was black and suitable for planting and raising every type of crop. But the slightest rain shower would turn it into mud, causing the wagon wheels to sink in. In the fall, the thirteen-kilometer trip might take four hours or more. The horses wallowed in mud above their knees. There were no nearby stones for road repair, and tree branches would be placed crosswise on the road; however, this solution was short-lived. As the rain continued, these branches would also sink into the mud, and the road became completely blurred. People's lives had been virtually unchanged for centuries. Even when Russia was in the midst of revolution, Hrubieszow was not affected. The new intensive Zionist activity that agitated to attend the annual Zionist congress hardly changed ordinary life. The government prohibition against forming societies went unchallenged,

There was a four-year elementary school in town, but only one Jewish family sent its children there. Jews were accepted into the Russian high school according to the law: ten percent of the students.[8] In Hrubieszow, these ten percent consisted of Jewish children from other towns. The local children studied in cheders, like their ancestors.[9] They learned to read and write Yiddish, and learned the local language from teachers whose own knowledge was poor; they were incapable of teaching anything besides writing an address in Russian and a letter in Yiddish. One teacher began a school for Russian language, mathematics, and Yiddish. The students arrived at different times, and studied individually. The teacher would occasionally walk around, look at their notebooks, and make corrections. Then several names would be called out; those students went to another room, where the teacher's son was the teacher. Students would take turns reading short chapters from a Russian book, and would be graded. Afterwards, they all returned to the large room and stood in a row before the teachers. The student with the highest grade would address the teacher as follows:

“Sir, we were tested in Russian. My mark was A. Student ‘b’s grade is B. Student ‘c’s grade is C”, and so on. The two hours in this school were over. Those who were late also stayed for two hours. They learned very little in this school.

The Houses of Prayer

The large, square synagogue was built of bricks, freestanding, and conspicuous in its height. All the women of the town prayed in the five women's sections in the synagogue, as the small synagogues had no women's sections. My father prayed in the synagogue on Saturdays, holiday, and the High Holidays. Twice a year - on the Saturdays before Yom Kippur and Passover - my father preached in the synagogue. The King's birthday and Coronation day were celebrated in the synagogue, and my father, as rabbi, was always present. During the Russo-Japanese war, all the Jewish residents were called to make a community prayer for a Russian victory. After Psalms were recited, my father spoke in Yiddish and later in Russian, for the benefit of the military officers.

The synagogue was not old. People were talking about its construction when my father was first appointed, as if they had witnessed it; and some of them may have indeed remembered the process. They recounted that, following the Jewish proverb, “Do not demolish a synagogue before a new one has been constructed,” they began building the new synagogue and demolished the old one only when the new construction was completed.[10] None of the workers wanted to begin the demolition. The Rebbe of Turisk then promised a heavenly reward to the one who began the demolition. A worker immediately climbed up onto the roof and began dismantling it.

The synagogue of the Belz Hasids was across the street, to the north of the Great Synagogue, and the House of Study was nearby. The Russian army controlled this building arbitrarily for many years, and used it as an armory. When the barracks was constructed outside the town and the army moved in, the House of Study was set free and restored to Jewish ownership.

My Father Hosts the Hasidic Rebbe

Many of the Hasids in Hrubieszow followed Rebbes who were alive, whereas others followed deceased Rebbes. The former would regularly travel to stay with their Rebbe, and the latter would continue their adherence to the deceased leader. Some Rebbes did not live in Russia. The Hasids would invite the Rebbe to Hrubieszow for one or two Shabbat occasions. My father was a Misnaged. He was not interested in learning from these Rebbes, who were all inferior to him in learning. He complained that the term Hasid was used loosely, and not everyone was worthy of it.[11] Yet when a Rebbe came to town, and his followers asked my father to host him, he agreed. This was after the death of my mother (may she rest in peace). My father lived in a spacious apartment with his two sons (my brother and me); he kept one room for us, and put the other rooms at the disposal of the Rebbe.

The Rebbe stayed in town for eight days, during which Hasids from the town and the entire vicinity came and went. While the Rebbe received notes with prayers of petition, asking for his blessing, his attendants were busy writing notes, selling bottles of oil, pretzels, and the like.[12] Once the Rebbe had pronounced a prayer over any of these objects, they could function as amulets and medicines. Other attendants stood at the door and maintained order.

The Decree Prohibiting the Shtrayml[13]

The Jews of Russian-controlled Poland were forbidden to wear the shtrayml. The Hasids, who wore the shtrayml on Shabbat, concealed it under their clothes and wore it once they were inside the synagogue. The process was reversed on their way home. Wearing the shtrayml outdoors could incur punishment. On weekdays, they wore a hat that resembled the hats worn by Russian soldiers; however, the Jewish hats were made of silk or velvet.

Most Jews could not tolerate this prohibition, and the shtrayml gradually disappeared until the rabbis were the only ones wearing it. They consistently wore shtraymls on Shabbat, even outdoors. My father did the same. Though he respected the laws of the state, he did not obey the decrees that limited Jewish life, and wore silk clothes and a shtrayml on Shabbat. The shtrayml now served the Russian authorities as a means of blackmail. A regular policeman who caught a Jew wearing a shtrayml could be bought off with a few pennies, but if it was a higher ranking official, the bribe was larger.

One Shabbat, on his way to prayers wearing silk clothing and a shtrayml, representatives of the provincial office confronted my father, ordering him to accompany them to their offices. He obeyed, and found out that he had been detained for violating the law on shtraymls and a silk sash. He was allowed to return to the synagogue.

My Father was Interested in Construction

My father bought a house in Hrubieszow, with a yard and a garden with some structures. As he was interested in construction, he always found a reason to add another building. The ovens were built by an old Jew, who was rumored to have served in the army of Nikolai I. He was very poor, and had trouble making a living. My father did not haggle with him, and paid him whatever he demanded.

The house had an attic, which could be accessed from the house through a narrow corridor. My father engaged a master carpenter to build the stairs, which spiraled around a central pole. It was complicated work, that required drafting and calculations. This carpenter was gifted. He was constantly busy trying to invent a wagon that would haul one hundred bricks without a horse. I do not know what came of this idea.

The house stood on a small hill, with a fence below. An old wooden cross, which was disintegrating, stood on the other side of the fence. Fairly close by, there was a house owned by a Christian. When my father's workers dug

[Columns 393-394]

the soil on my father's land, they dumped it over the fence until they eventually covered the foot of the cross. The Christian neighbor, who was displeased with my father's project, made a great fuss, as if the cross were being desecrated. The matter was brought before the authorities. As it happened, the workers were Christian, the neighbor and the cross were Catholic, and the authorities were Eastern Orthodox. The matter went no further, and there were no repercussions.

The New Torah Scroll

My father (may his memory be for a blessing) knew Russian, in addition to his proficiency in Talmudic material. He subscribed to Russian newspapers, and read the works of the great Russian writers. However, this did not prevent him from devoting most of his time to traditional Jewish scholarship; he preferred it to all the riches of the world. His esteem and admiration for the scholars of the Talmud were boundless.

It goes without saying that my father's behavior followed the Shulchan Arukh in every detail. In his conversation, negotiations, community prayer, personal prayer, eating and drinking, and every move, he obeyed the Shulchan Arukh simply, with no hairsplitting or elaborations, as though it was second nature to him. In the same manner, he commissioned a scribe to write him a personal Torah scroll, as our sages expounded on the biblical verse “Now write down this song.”[14]

The scribe spent almost a year writing this Torah scroll. It gave my father great spiritual pleasure. The completed scroll was magnificent; the parchment was beautiful, and the penmanship exquisite. Aryeh HaSofer was an expert at this sacred work. When the writing commenced, my father traced the first word in ink, and no one was permitted to write in the scroll after its completion. My father also wrote in the last word, Yisra'el, which happened to echo his own first name. If I remember correctly, he did not allow women to sew the parchment strips together. The scroll was taken to the synagogue under a chuppah.[15] The ceremony was followed by a festive meal for some local guests.

My father kept the Torah scroll at home, in the room that served as the office of his rabbinical court. The room was used for Shabbat prayers as well, and my father prayed there on Friday nights. On Shabbat morning he would always go to the synagogue. Most of the congregants in the group he joined were unmarried, and this group was known as the “unmarried man's minyan.” It was unusual in that the Haftorah was chanted to a melody-a custom habitual in Lithuania and Belarus, but not in Poland.

During World War I, my father contracted typhus, which left him with permanent after effects, causing diseases and ruining his health irreparably.

When Hrubieszow was taken by the forces of Austro-Hungary, the population was heavily taxed. My father was then summoned to the town commander, who threatened him with a handgun. I do not know whether this threat was in connection with the tax (I heard only rumors), but can imagine the terror that my father suffered - this righteous, pure, and sensitive man, who had never touched a weapon, never bothered a fly, and never caused pain to any person, even through words. Now he was confronted by a crude, filthy person who cared nothing for human life.

His physical weakness was long lasting. His material circumstances also declined: as his money had been invested in government bonds, and it had lost its value. He therefore had to sell the house that he had built, and move into three small rooms with his wife and five small children. His salary also declined, due to the falling rate of exchange. Yet he never ceased studying, and found comfort in religious learning.

When independent Poland was constituted once again, following World War I, news came of persecutions of the Jews everywhere; these pained him greatly, as he loved every person. When the war ended, he tried to travel to Kiev, where his wife's valuable jewels were kept in a bank; but the bank had been robbed by the armies.

Despite his dwindling strength, he continued to serve as Rabbi for six years after the war. When his condition deteriorated, he begged the doctors to keep him alive, but they could not help him. He died on February 16, 1925, at age 65. His gifts and knowledge were buried with him.

Translator's Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Hrubieszów, Poland

Hrubieszów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 Sep 2022 by LA