[Columns 51-52]

The Town of Hrubieszow and its Rabbis[1]

by Tzvi Ha–Levi Ish–Hurvitz

Translated by Yael Chaver

Hrubieszow is just a town in Poland, but it is ancient. In about 1640, it was home to a large, very important Jewish community, one of the main communities in the district of Chelm, part of Lesser Poland. Poland was then divided into several provinces: Greater Poland, Lesser Poland, Russia (Raysn) or the Lviv district, Volhynia, and Ukraine.[2] They comprised districts with dominant communities that headed the towns in the district. About 150 years earlier, the three districts of Lublin, Chelm, and Belz became combined, and an official rabbi was appointed. The first known official rabbi was Rabbi Yehuda Aharon, head of the rabbinical court of Chelm. In 1520, King Zygmunt I appointed him tax collector of the Jews in these districts. On July 21, 1522, the same king appointed him rabbi of the three districts (Lublin, Chelm, and Belz). After his death, King Zygmunt I appointed two rabbis for the provinces of Lesser Poland and Raysn (Lviv). These were the Gaon Shalom Shachna, head of the rabbinical court of Lublin, the father–in–law and teacher of Rabbi Moses Isserles and a distinctive student of Rabbi Ya'akov Polak, head of the rabbinical court of Cracow; and Rabbi Moshe Fishels, a physician in Cracow. The merger dissolved after the death of Rabbi Shalom Shachna of Lublin. The Belz and Chelm districts joined and formed a single district. Their rabbi was the Gaon and kabbalist Rabbi Eliyahu, head of the rabbinical court and the son of Rabbi Yehuda Aharon, who also served as rabbi in Chelm and was the first rabbi appointed over the three districts.

Hrubieszow was the largest and most important community of the entire Chelm district, except for the city of Chelm itself, which headed the district. In the 1590s, there were about 200 Jewish families in Hrubieszow. However, in 1648, they were almost all murdered by the forces of the Khmelnitsky gangs (may the names of the wicked rot). When the fighting subsided and the region grew calm, Jews resettled the town. It soon became a large, important community, with numerous residents, rich in scholars and scribes. Its rabbis were learned, eminent, and renowned. As the major community in the Chelm–Belz district, Hrubieszow selected one leader for the State Committee; only four major communities in this district were capable and brave enough to send their leaders and rabbis to the State Committee. These were the major communities of the Chelm and Belz districts: Chelm, Belz, Lubomia, and Hrubieszow. The official leaders of Chelm and Belz districts received 200 złoty and expenses annually. The official rabbis of these four communities received an annual 300–450 złoty; the secretary and scribe – the “trustee of the Jewish community” – received 150 złoty annually. In 1765, there were 1,023 Jews in Hrubieszow; it was the largest Jewish community in the Chelm district, except for Chelm itself, which was home to 1,468 Jews.

In the 1740s, the Hasidic movement – founded by Levi Yitzchok of Berdichev – began to spread to Hrubieszow, which became a center of Hasidism. It was led by the righteous rabbi Yosef, son of the Tzaddik Mordechai Katzenelboigen (known as Rabbi Mordechai of Skhizh) who moved there in the 1790s. The community greatly declined later in both wealth and standing; it became small, and no longer had great–learned rabbis as before. Its rabbis were tzaddiks and mystical scholars.

A Hebrew printing press was established in the early 19th century, which printed many important and expensive books, but it could not survive, due to the impoverishment and decline of the community in appearance, wealth, religious scholarship, and numbers, as it is to this day.

These are the rabbis who served in Hrubieszow from the beginning until recently.[3]

- The gaon of his generation, Rabbi Chaim Chaike Ha–Levi Hurvitz. His father, the gaon and Hasid, Rabbi Shmuel Shvartser (Shachor) Ha–Levi, was the brother–in–law and blood relative of the great gaon Rabbi Yehoshua of Cracow, author of Meginei Shlomo and the Pnei Yehoshua responsa. He may be the person referred to as Shmuel, a Rabbi of the Committee of the Four Lands, who was in Yaroslavl in the summer of 1621, and signed as Aaron “Shmuel, son of Yehoshua Segal Ish–Hurvitz.” We know, from Shmuel's history, that he had three sons. The oldest was Rabbi Aryeh Leib Bosker; the second was the gaon Rabbi Yehoshua Moshe Aharon Ha–Levi Hurvitz, some of whose commentary appeared in the book Ge'on Tzvi (Prague 1737) by his son the gaon, head of the rabbinical court of Zablodowa. “And Joshua died” – this is the gaon Yehoshua Moshe Aharon Ha–Levi on December 7, 1649 in Kuznitz, near Lublin.[4]

The third son of Rabbi Shmuel Shvartser Ha–Levi was the renowned gaon Rabbi Chaim Chaike Ha–Levi, one of the greatest students of the excellent gaon Rabbi Jacob, head of the rabbinical court of Lublin. Within the lifetime of his teacher, Chaim Chaike Ha–Levi was the head of the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow. He had discussions from there with his teacher about the laws of marriage between a Kohen and a woman who may be divorced.[5] His response appeared in Ge'on Tzvi (written by his nephew, Tzvi Hirsh Ha–Levi Hurvitz) and begins with great affection and profuse compliments, as follows: “Peace and love to my beloved great scholar Adino the Etznite, head of a yeshiva and head of a rabbinical court, the great light, greater than our teacher Rabbi Chaim Segal (may God protect and preserve him)[6].” He became renowned throughout the Jewish world as one of the greatest scholars of his generation. In 1665 he was appointed once again as the head of the rabbinical court of Grodno, Lithuania. After about ten years of service, he died there in 1675. His son, the gaon Rabbi Shmuel Ha–Levi, had dialogues with his cousin, Tzvi Ha–Levi. His question was printed in the Geon Tsvi Responsa, and signed “Sunday, 2 December 1670, his cousin Shmuel, the son of his famous uncle the gaon Rabbi Chaim Ha–Levi.”

- The gaon Rabbi Meshullam Feivish, son of Rabbi Menachem Gintzburg Ashkenazi, as head of the rabbinic court of Hrubieszow in the Yaroslavl council, approved, on the 22 day of Elul 1677, the publication of the Bible with German translation (alef–mem–dalet 1677).[7]

- The gaon Ya'akov. His student Menachem Mendl recounts, at the end of his book Tzintzenet Menachem (Berlin 1720), “then my father–in–law, may his righteous memory be for a blessing, sent me to study with Rabbi Ya'akov, who was later head of the Hrubieszow rabbinical court.”

- The gaon Rabbi Avraham Abele of the Zak family. His father, the gaon Bunem, was the son of the gaon Meir, son of Avraham Zak, head of the rabbinic court of Lviv proper. They were called Zak (holy seed), as they traced their lineage to Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (may his memory be for a blessing), whose descendants were martyrs to God in all the persecutions.[8]

- The gaon Rabbi Yitzchak, son of Rabbi Yehuda, who was known as Yitzchak Charif, the brother–in–law of the famous maggid (preacher) Yosef, son of Moshe, the rabbinic judge of Przemyśl.[9] Apparently, the brothers–in–law married the daughters of the chief Rabbi Naftali of Przemyśl. As head of the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow, he approved publication of Chilukei Derabanan (1695). He also published a rabbinic tale in Ktonet Pasim (Lublin, 1685) compiled by his above–mentioned brother–in–law, who writes, “written by my brother–in–law, the great light, Yitzchak (may his light shine), head of the rabbinic court of Hrubieszow.”[10]

- The gaon Rabbi Shmuel Shmelke, son of Rabbi Mordechai Margaliot of Cracow. At the meeting of the rabbis of the Council of the Four Lands of Poland, on October 24,

[Columns 53-54]

1712, in Yaroslavl, he approved publication of the book Berit Shalom on the Torah (Frankfurt–am–Main, 1715), signing “Shmuel, son of Rabbi Mordechai Margaliot head of the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow.” In 1728 he gave his approbation to the book Beit Lechem Yehuda (Zhovkva 1943), signing “Shmuel, son of my father, teacher, and rabbi Mordechai Margaliot, living in Hrubieszow and Moreh Tzedek in Kowel and the district, completed this task in 1735.[11]”

- The gaon Rabbi Aryeh Libesh, son of Rabbi Yitzchak Kantchiger. He came from a family of great rabbis, renowned in the world of Jewish scholarship. His grandfather, the gaon Rabbi Ya'akov, head of the rabbinical court of Skała, was the son of the gaon and hasid Rabbi Zechariah Mendl of Cracow, known as Rabbi Mendl Kloyzner, because he spent his days studying and lived very modestly and austerely, ignoring all worldly temptations.[12] As an old man, he traveled to the land of Israel and was known as a “leader in Jerusalem.” He was greatly venerated and considered an important holy and righteous man, and was thus also termed “the prophet Zechariah.” Rabbi Aryeh Libesh was born in 1698 in Kańczuga, Galicia. Aryeh Libesh was blessed with great talents, a sharp mind, and a passion for learning. He was always abstemious and modest, did not eat meat on weekdays, and immersed himself in cold water daily, even in very cold weather, when he was over 80 years old. He was the bravest of all, having committed to memory the entire Talmud, as well as Rashi's commentary, all the later legal Talmudic scholarship, and the decisions of Mamonides and his students. Other scholars often turned to him for opinions as one who is close to God, and answered everyone in a scholarly and logical manner. He was greatly beloved and a light to the world. The gaon Rabbi Ya'akov Yehoshua, head of the rabbinical court of Frankfurt–am–Main (author of Pnei Yehoshua) considered him “the greatest Talmudic scholar of his generation.” While still a young man, he was appointed head of the rabbinical court in his home town. This was followed by his appointment as the head of the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow. However, his zeal for learning was so great that he retired from the rabbinate and moved to Złoczów to live privately. He continued to teach many, including his sons, grandsons, and great–grandsons, who themselves served as examples to many. In about 1730 he was well established in Złoczów. Though in that year he was offered the position of head of the rabbinical court of Dubnow after the death of the previous rabbi Yehoshua Heshl (who had died in 1729) he refused, so as not to stop studying, and stayed in Złoczów, studying and praying, for the rest of his life. He died, in old age, in 1786. Some of his notes to the Talmud were published as Ateret Zekenim (Lviv 1871).

- The gaon Rabbi Yoel, son of the gaon David Katzenelboigen. His father was head of the rabbinical court of Kiejdany and the district; he died there in about 1756. His grandfather was the renowned gaon Rabbi Yechezkel, head of the rabbinical court of Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbeck; he was the author of Knesset Yechezkel. His wife was Yorit, the daughter of the renowned gaon Chaim Kohen, head of the rabbinical court of Lviv. In his youth, Rabbi Yoel was the head of the rabbinical court of Jarczów, near Lviv. While there, he gave his approbation to the publication of Mishneh Lechem on July 16, 1751; and of Ohel Moshe (Zhovkva, 1754). Two of his responsa appeared in the book by his father–in–law, the gaon Chaim Kohen, in sections 23–24, which he signed on Nov. 27, 1755: “Yoel Katzenelboigen, in Jarczów.” Afterwards, he was re–appointed head of the rabbinical court of Sieniawa, where he gave his approbation to the book Asefat Yehuda (Frankfurt–am–main 176[[13] …]). In his last years he was head of the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow. He died in about 1770. His son Doberish published Mi–Yam Yechezkel (Poryck, 1786), by his grandfather the gaon Rabbi Yechezkel, head of the rabbinical court of Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbeck. His widow married the gaon Rabbi Ze'ev Volf, who followed him as head of the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow. It was Rabbi Ze'ev Volf's second marriage, his first wife having died.

- The gaon Rabbi Ze'ev Volf, gave his approbation on May 27, 1770, to the publication of publication of Shevet Mi–Yisra'el (Zhovkva 1772), and on November 15, 1786 to the publication of Mi–Yam Yechezkel (Poryck 1786). His first wife gave birth to a son named Shaul, who married the daughter of the gaon Yitzchak Ha–Levi Ish Hurvitz, head of the rabbinical court of Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbeck. She gave birth to one son and two daughters. Tovah and died in Brody on April 15, 1796. Her husband died in Brody on November 17, 1806.

- The gaon Moshe Yitzchak, father of Zvi Hirsh Parnas and community leader in Zamość, who joined the other leaders in approving publication of the Talmud in 1752.

- The gaon Chaim Hochgelehrter, the son of an important family, a superior scholar, a descendant of the gaon Meir ben Gedalia of Lublin. He was born in 1769. His father was the gaon Yosef, head of the rabbinical court of Zamość, author of Siftei Chachamim on Maimonides (Lviv 1790–1792), and his mother Tzipora was the daughter of the great gaon Rabbi Ya'akov, head of the rabbinical court of Lublin (who died there on September 3, 1769), the son of the renowned leader, the great Rabbi Avraham, son of Rabbi Chaim of Lublin. Rabbi Avraham, “and Abraham died there, old and having lived his fill of days” died there on 15 Cheshvan.[14] As a young man, not yet 15, Chaim married his cousin Feygele, the daughter of his mother's brother the gaon Rabbi Yitzchak, head of the rabbinical court of Tarnów (the son–in–law of the gaon Moshe Levov, head of the rabbinical court of Moravia). At age 19 he was once again appointed head of the rabbinical court of Ostrowiec, and later the head of the rabbinical court in Hrubieszow. After serving there for a number of years, he returned to his home town of Zamość, where he had a big house and much money. In 1809, during a war with France, when Zamość was besieged, he and his family, including his mother, left the town. His mother lived with him after the death of her husband, author of Mishnat Chachamim (who died in Zamość on April 9, 1807, aged 67). They moved to the nearby town of Grabowiec. However, he died not long afterwards during an epidemic. He and his entire family died within the same month (February 1809); he was less than 40 years of age.

- The gaon Ya'akov, whose son, the gaon Rabbi Baruch (son–in–law of Rabbi Moshl of Lviv) was head of the rabbinical court of Owrimil, and died in Lviv on January 28, 1841.

- The gaon and Hasidic Tzaddik, Rabbi Yosef, son of the renowned Hasidic Rabbi Mordechai of Neszhchiz, born Katzenelboigen. Formerly head of the rabbinical court of Uściług, he moved to Hrubieszow. There, on October 17, 1817, he gave his approbation to the book Meor Einayim (Hrubieszow, 1815).[15] He is described in the approbation as “Rabbi and Tzaddik of Hrubieszow and head of the rabbinical court of Uściług and the district”; he signed as “Yosef, son of the renowned rabbi Ben Ish Chai, head of the rabbinical court of Skhizh and the district (may his holy memory be for a blessing) Katzenelboigen.” He died on September 6, 1830, in Ostroha. He was a Tzaddik to his hasidic followers, and was better versed in Kabbala than in Talmud; therefore, during that time the rabbinical court was led by the rabbinical judges, headed by the gaon Rabbi David, son of Aharon Shalit. A response addressed to him was published in the Responsa Peri Tvu'ah (Nowy Dwór, 1796). He also gave his approbation to many books published there at the time. He died on April 27, 1830. He is mentioned with praise by the great rabbi and scholar, Ze'ev Dov Shiff, in his Minchat Zikaron (Cracow 1894), in his remarks on the Eruvin tractate of the Mishna: ”I remember passing through the important town of Hrubieszow about twenty years ago, when I suggested this to the great rabbi, the famous righteous man whom I appreciated, David Shalit (may he rest in peace), who approved of it strongly. May his merit stand me and my descendants in good stead. He was not named Shalit in vain, because he controlled his temper all his life, until his sun set; as the sages say, “The righteous control their spirit.”[16] That is enough.

- The gaon Yosef Elazar Gelernter, born to his father, the gaon Avraham Ya'akov Gelernter, head of the rabbinical court of Tyszowce (the brother–in–law of the gaon Yitzchak Hoichgelehrnter, head of the rabbinical court of Zamość; both were sons–in–law of the gaon Elazar Segal Landau, head of the rabbinical court of Turobin). In 1812, as a young man, he headed the rabbinical court of Laszczow, and later the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow. He died there in 1864. He was the father–in–law of the renowned gaon Gershon Hanoch Henich Leiner of Radzyń, author of Sidrei Tohorot on the tractates of Kelim and Ohalot.

These were the rabbis of Hrubieszow, from the beginning until recently, and that is enough.

Footnotes:

- Original note: Printed in Ha–Tzofe LeChochmat Yisra'el, Budapest, 1931. Return

- Translator's note: Raysn is known today as Belarus. Return

- Translator's note: This section uses the Jewish calendar, in which letters of the alphabet are used for their numerical values. The Jewish calendar is reckoned from the Creation, based on dates in the Bible. Here and below, I have used the roughly equivalent dates on the Gregorian calendar. This is because the Jewish year typically begins in September and extends to the following September; where only the Jewish year is given, I have chosen to present the Gregorian year covering the larger part of the Jewish year. Where an exact Jewish date appears, I have presented the equivalent Gregorian date.

The descriptions of rabbis are very stylized, highly complimentary and florid, and often incorporate fragments of biblical verses, abbreviations, acronyms, and other shorthand that the contemporary reader would have known. I have translated parts of these, in order to transmit the flavor of this style. Parts that have not been translated are indicated by an ellipsis within square brackets. Return

- Translator's note: The reference to Joshua is a quote from Joshua 24;29. Yehoshua is the phonetic spelling of the biblical name. Return

- Translator's note: A male Kohen (descended from a priestly family) may not marry a divorcee, a prostitute, a convert, or a dishonored woman (Leviticus 21:7.) Return

- Translator's note: Adino the Etznite is one of David's great warriors (II Samuel 23; 8), who is construed in later interpretations as both a great warrior and a great scholar. Return

- Translator's note: I could not identify the acronym alef–mem–dalet. Return

- Translator's note: The surname Zak (an acronym for Zera Kodesh, literally meaning Holy Seed–– a quotation from Isaiah 6:13) implies descent from martyrs. Return

- Translator's note: Charif literally means “spicy hot” and can be used as a complimentary appellation for a superior scholar. Return

- Translator's note: The blessing “may his light shine” is used as a compliment for persons who are living. Return

- Translator's note: Parts of this sentence are obscure; the year mentioned, 1943, is an error (and may refer to 1743). A Moreh Tzedek is an “auxiliary” rabbi authorized to make Halakhic decisions. Return

- Translator's note: The Yiddish kloyz refers to a small synagogue. Return

- Translator's note: The Jewish date given (55250), is a typographic error and most likely refers to 5525, which would be the Gregorian year 1763 or 1764. Return

- Translator's note: The reference to Abraham evokes the biblical description of the patriarch Abraham's death, Genesis 25:8. The Jewish month of Cheshvan approximates October–November. See Note 15. Return

- Translator's note: There is a discrepancy between the dates given. Return

- Translator's note: The Hebrew term shalit means ruler. Here, it is presented as an acronym, which I could not identify. Return

[Columns 55-56]

Notes on the History of Hrubieszow

by Chaim Feifer (Kiryat Gat, Israel)

Translated by Yael Chaver

Hrubieszow, in Lublin Province, was founded in 1400; Jews have lived there since the mid–15th century. At that time, Poland was lagging in commerce and industry, and Jews were desirable as elements to spur the development of the country. Jews had relatives in other cities and countries, with whom they could have commercial ties. As potential aids to economic development, Jews received special commercial rights.

In 1456, King Kazimierz Jagiellończyk gave the Jew Michael of Hrubieszow broad trading privileges with Vienna and other cities. The Jews' main occupation at that time was tax–collecting based on lease contracts.

In 1493, King John Albert awarded additional easing of taxes and exemptions for three years to the Jew Shach–Shachevich of Hrubieszow. In 1564 the Jews of the town received the right to lease the kosher slaughterhouse in H and to sell meat throughout the town.

In 1578, the Jews received significant rights from King Stefan Batory. The most important of these were the right to live on all the streets of the town, and to build a synagogue free of taxes. During that year of Jewish well being, the Jew Avraham of Hrubieszow had the idea of constructing wine distilleries in the town.

In 1578, there were 100,000 Jews in Poland. The number of Jews and Jewish towns increased throughout the 16th century. By mid–century, Poland had the second largest Jewish population in the world, after Turkey. In the mid–17th century (before the pogroms of 1648) Poland's Jewish population exceeded that of Turkey, and the country became the largest Jewish center in the world.

During the second half of the 16th century, Polish Jews began to settle in villages, especially in the southeast – a rarity in earlier times. Migration from the large cities to the smaller towns and the villages, and from western Poland to more easterly areas, was linked with important changes in the economic structure of Jewish society.

In 1765, there were 1,023 Jews in Hrubieszow, 709 in the town and 314 in 51 surrounding villages. Their main occupation was leasing land. The Polish nobles preferred to lease their land to Jews, as profits were better assured.

In 1567, King Zygmunt August permitted the Jewish community of Lublin to open a yeshiva in a special building; four years later, he granted unlimited rights to establish schools and yeshivas everywhere. This resulted in well–organized yeshivas throughout Poland and Lithuania. Each community founded a yeshiva, and paid the head of the yeshiva well, so that he could do his work without worrying about his livelihood. Each community subsidized students, who would be paid a weekly sum so that they could continue their studies.

At that time, the social and economic regime of Poland – as in other countries – awarded the Jews special standing, with internal autonomy, community institutions, and judicial courts. Medium and small communities had 10–20 leaders, who were selected by lots annually, during the Passover week. One of the factors that led to a structured Jewish autonomy was the tax–collection system, which encouraged the Polish government to grant such autonomy to isolated communities.

The Polish government did not only utilize the centralized collection of taxes by the community – which relieved the government of the need to collect tax from each Jew separately –but also sought to be free of the need to negotiate with separate communities. It was in the interests of the royal treasury to assess the taxes in general sums for the provinces that comprised several communities. This created tax districts, whose boundaries were identical with the boundaries of the historical “lands,” such as Greater Poland (identical with Poznań), Lesser Poland (identical with Cracow and Lublin), etc. Separate communities combined as associations within these provinces.

Hrubieszow was one of the important communities in the association known as Belzer Land; its delegates would gather at regular intervals and discuss current issues and tax payments.

The communities, who were guarantors of each other concerning tax payments, would send their delegates to the commissions in order to set the tax for each community. In 1581, a comprehensive poll tax was imposed on the entire Jewish population of Poland and Lithuania; however, from 1590 on it become customary to set separate sums for Jews of Poland and of Lithuania. This was the basis for forming provincial associations, and later two separate associations. In 1623, the associations were given legal status and were termed “Council of the Four Lands.” The Council discussed impositions of tax as well as other issues pertaining to the entire Jewish community. The Council usually assembled at the fair, which was an occasion for settling disputes between rabbis and their communities; it was also a setting for making matches between couples. Hrubieszow was connected with the fair at Lublin, one of the largest.

In the first half of the 17th century, the Hrubieszow community numbered 200 families. The Jewish community suffered about twenty years of pogroms during this period. The pogroms were linked with the Cossack revolt against Polish rule in Ukraine, which erupted in 1648 under the leadership of Bohdan Khmelnitski. Dozens of Jewish communities were destroyed during this murderous time, but the Hrubieszow community persisted and continued to exist afterward.

The Catholic Church had great power at this time, and strong influence over Jewish affairs. In 1678, the Church forced the Jews of Hrubieszow to sign a commitment to pay annual taxes to its institutions. The Hrubieszow community suffered under the increasing tax burden. Further disaster struck in 1736, with the outbreak of a large conflagration. 27 Jewish houses were burned down, leaving dozens of families homeless. The small synagogue and the bathhouse also burned down. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the community's condition deteriorated. Community funds declined. The poll taxes for Jews rose, though their financial capacity did not expand. In 1725, the poll taxes in Hrubieszow amounted to 2, 260 złoty; in 1728, the sum increased to 3,000 złoty.

Conditions eased a bit in the second half of the 18th century, and the conditions of the Jews improved. The poll taxes decreased; in 1758 they were 872 złoty. Although the number of Jews was stable, their better economic situation made the upkeep of rabbis possible, as was the financing of Talmudic studies. At this time, Hasidism spread in Hrubieszow, and contributed to the intellectual development of the town. The cultural–intellectual flourishing of the Hrubieszow Jewish community is linked with the figure of the great mathematician, Avraham Ya'akov Shtern.

The Jewish community of Hrubieszow was decimated during World War II; the survivors were dispersed throughout the world. There are no Jews in Hrubieszow today. A few Jews came through the town after the war, but did not settle there. In 1954, the population of Hrubieszow was 11,300, largely occupied with flour production and straw–woven objects. But there were no Jews in Hrubieszow…

This town, with Jews among its founders, who continued to live there for 480 years despite the crises, contributed to its culture and always constituted at least half its residents – and sometimes the majority – now has no Jews. Jewish Hrubieszow no longer exists. It exists only in the hearts of the Jews who were born there, grew up in its Jewish culture, and passed their idealistic youth there. Today, it is nothing but memories.

But the black soil that produces such rich harvests still gives off fumes redolent of Jewish blood; fumes so poisonous that no Jew will ever dare to breathe there again. Perhaps this is all to the good, so that no Jew will try to ignore the historical lesson.

[Columns 57-58]

The Hebrew Printing Press in Hrubieszow[1]

by Avraham Ya'ari

Translated by Yael Chaver

H. D. Friedberg attempted to describe the history of the Hebrew printing press in the Polish town of Hrubieszow in a chapter of his book Toldot Ha–Defus Ha–Ivri Be–Polaniya.[2][3] I made some additions to his article in my critique of this book.[4] In the meantime, I have been able to acquire previously unknown books from the Hrubieszow printing press for the Jewish National and University Library. As I have become convinced that Friedberg's account is not only lacking but also contains superfluous items, I will now try to summarize all that I currently know about the Hrubieszow printing press. This article will present an entirely different picture of the activities of the Hebrew printing press in this town.

The Hrubieszow Hebrew press was established after the French war (1816), and existed as late as 1823. Thus, it was in operation for eight successive years, and – as far as we know – printed 34 books. The founders of the printing press were Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein, Moshe Tzikor, and Shaul Moshe Goldshtein. The first – and most important – was Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein (who had the capital), from Hrubieszow. The second, Moshe Tzikor, from Laszczow in the same district was an expert printer, who had previously been a printer of Hebrew in Laszczow, together with Yehuda Leib, son of Yitzchak Rabinshtein, in 1815–1816.[5][6] The third, Shaul Moshe Goldshtein, of Hrubieszow, had also worked as a printer in Laszczow in 1816; he printed one book jointly with Yehuda Leib Rabinshtein.[7]

The names of the three partners are sometimes listed in detail on the title pages of the books printed in Hrubieszow.[8] Sometimes only the name of Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein appears, and the others are mentioned only as “his friends.”[9] Sometimes only the first two participants are mentioned, Finkelshtein and Tzikor.[10] In 1819 Goldshtein left the partnership, and his name no longer appears on title pages; Finkelshtein and Tzikor alone are mentioned.[11] Starting in 1821, some books bear the name of Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor.[12] In 1823 another partner joined, Shlomo, son of D. Lev of Laszczow.[13][14]

The names of the town or the printers are omitted from the title pages of several of the books printed in Hrubieszow. This is probably due to censorship, or book tariff payment.[15] Sometimes the printers mentioned their names in some copies but not in others; sometimes they even inserted the name of a different town or stated a different year, to deceive the censor or the tariff–collector.[16]

Some of the master printers came to Hrubieszow from other places, especially from Laszczow (in which two of the printers mentioned above had earlier worked), as well as from Lviv and Zhovkva. Others mastered their craft in Hrubieszow. The workers at the Hrubieszow press were:

- Eliezer Segal, proofreader, 1818.

- Baruch Avraham, son of David, from Hrubieszow, typesetter, 1819.

- Daniel Ze'ev, son of Meir Segal, of Hrubieszow, press operator, 1818.

- The bachelor Chaim, son of Eliezer, of Lviv, typesetter, 1818–1819.

- The bachelor Yitzchak , son of David, of Laszczow, typesetter, 1817.

- Yissachar, son of Refael, of Zhovkva, press operator, 1818.

- Menachem Mendl, son of Baruch, Segal, of Zhovkva, typesetter, 1818,

- The bachelor Pesach Yosef, son of Tzvi Hirsh, of Lenczno, press operator, 1818–1819.

The books printed in Hrubieszow were elegant in appearance, but not of significant content. Most had been printed previously by other presses. These books were in great demand, such as popular Yiddish books,[17] books of ethics and legends,[18] various prayer books,[19] and books of Hasidism and Kabbala.[20]

Almost all the books printed in Hrubieszow contain the particular colophon of that printing press, either on the title page or the obverse, or at the end of the book.[21] Thanks to this feature, books printed in Hrubieszow, in which the name of the town has been omitted, can be easily identified.

Before moving on to the list of books printed in Hrubieszow, I would like to clarify some matters, such as books erroneously listed by Friedberg as having been printed there.

In the section Bet Eked Sefarim, Friedberg writes: Likutei Halachot by Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, Hrubieszow 1809. This not the case. There was no printing press as yet in Hrubieszow in 1809, and Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav's Likutei Halachot was first printed in Zhovkva in 1806–1807.[22]

In his book Toldot Ha–Defus Ha–Ivri Be–Polanya, p. 101, Friedberg lists, among the books from the Hrubieszow press, Yein Ha–Rokeach, 1817. Such a book does not exist. The error is based on the fact that in 1820 the Song of Songs with commentaries by Nachmanides and Eliezer of Worms, titled in other editions Yein Ha–Rekach as well, was printed in Hrubieszow.[23]

Friedberg also includes Pitchei She'arim, Hrubieszow, 1819. He refers to Pitchei She'arim, a commentary on the Bava Metzi'a tractate, by Yissachar, son of Yehuda Leib, as he explains in Bet Eked Sefarim. The first part of this book was printed in Dyhrenfurth in 1819. Part 2, as well as the last three chapters, was printed without mentioning the locality; the title page has “1819.” I do not know why Friedberg thought it was printed in Hrubieszow. Based on the paper and the lettering, it was obviously printed in the second half of the 19th century; in my opinion, it was printed in Breslau or in Koenigsberg in approximately 1860. In any case, it was not printed in Hrubieszow (or Poland–Russia at all), and not in 1819.

Among the books printed in Hrubieszow, Friedberg lists Totz'ot Chaim, 1817. I assume he is referring to a book by this title, which is an abbreviated version of Reshit Chochmah, printed that year without mentioning the locality. The frame around the title page indicates that it was printed in Minkowicz, and it should be added to the list of books printed in Minkowicz.

Finally, one more book that is listed as having been published in Hrubieszow was actually published in Polonne. This is Chavat Da'at by Ya'akov of Lissa.

List of Books Printed in Hrubieszow

1816

- Shir Ha–Shirim (with Yiddish translation), Hrubieszow 1816. (According to Prylucki, Mame–Loshn, Warsaw 1924, p. 81.)[24]

1817

- Heed the book of Orchot Tzaddikim, that you may walk in the path of the righteous. [2.5 lines of Old Yiddish] By permission of the censor. Printed here in Hrubieszow, at the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein… and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor of Laszczow and … Shaul Moshe Goldshtein. 1817. 33 pp. duodecimo, 16x12 cm. Tsena u–Re'ena font.

- Gedulat David u–Malkhut Shaul [Ten lines in Old Yiddish, except the name of the book and the writer]

[Columns 59-60]

[line 4] …the wonderful book Melukhat Shaul (by Yosef Ha–Efrati of Tropplowitz)

Printed here at Hrubieszow in 1817. Tsena u–Re'ena font. (In the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York.)

The original was first printed in Vienna, 1794. The translation was first printed in Lviv, 1801. Translated by Naftali Hirsh, son of David. See my comments on the translation and its various editions in Kiryat Sefer 12, p. 384 ff. Friedberg erroneously writes Gedulat Shaul.

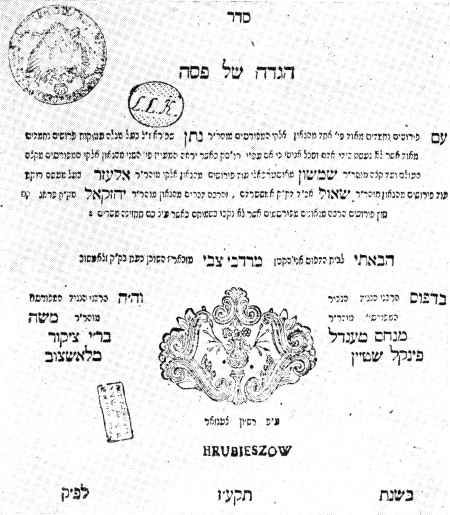

- Haggada Shel Pesach with commentaries[25] … one by the gaon, Rabbi Natan Spira, author of Megaleh Amukot… one by the gaon… Rabbi Shimshon of Ostropol… additional commentaries by the gaon Rabbi Eleazar, author of Ma'aseh Roke'ach, and by the gaon Rabbi Shaul, head of the rabbinical court of Amsterdam, and many additions by the gaon Rabbi Yechezkel of Prague; and many additional commentaries by renowned scholars whose names are not mentioned… Compiled by myself, Mordechai Tzvi of Zaborze, now in Zloczow. Printed by… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and…Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow. Hrubieszow, 1817. Square letters with diacritics and Rashi font.[26] (I saw it in the Schocken archive, Jerusalem).

- Likutei Halachot, known as Lekach Tov… (a study guide to the Talmud). Hrubieszow 1817. (Friedberg, Toldot Ha–Defus Ha–Ivri Be–Polanya, p. 101). There is no doubt that this book was printed in Hrubieszow, as it is mentioned in a later edition of 1825, from a town in Russia: Likutei Halachot, known as Lekach Tov… now reprinted with special features in larger font…and the important addition “earlier printed in Hrubieszow 1817.” (I saw it in the possession of Mikhl Rabinovich, in Jerusalem.) Friedberg only notes the title, Likutei Halachot, and does not mention the nature of the book. On the other hand, he notes in Bet Eked Sefarim: Likutei Halachot by Nachman of Bratslav, Hrubieszow, 1809. This must be an error, as Nachman of Bratslav's Likutei Halachot was first printed in Zhovkva in 1846–1847. (See G, Scholem, Eleh Shemot booklet, no. 21.

- No'am Elimelech, written by the kabbalist and famous devout rabbi, called “a holy man of God, whose learning spreads wide and his studies are his occupation (Elimelech of Lizhensk) on the Pentateuch … and several additional comments on verses, Talmudic sections and interpretations… to teach God's nation the way of God and the proper deeds. So as not to waste blank paper, we have first printed commands of the rabbi. At the end, we printed Ta'mei Mitzvot ve–Sodot by Yosef Gikatilla (may his righteous memory be for a blessing), including the reasons for commandments of tefillin, mezuzah, Shabbat, and sha'atnez. At the printing press in Hrubieszow, by… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and his companions, 1817. (1), 93 pp., 22 x 18 cm, Rashi font.[27] The book's title and the names of the town and the printer are printed in red ink.

- Sefer Hasidim [9.5 lines in Old Yiddish]

Line 10: in Hrubieszow¸ by the printers… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and … Moshe, son of Y. Tsuker and … Shaul Moshe Goldshtein, 1817.[28] 32 pp., quarto, 21x18 cm. (Tsene u–Re'ene font). In some copies, the names of the town and the printers are missing from the title page, and the date is presented differently. This might have been done to conceal the identity of the printers and to confuse the issue of the date.

- Shivchei Ha–Besht … is the deeds and miracles of … Yisra'el Ba'al Shem Tov (may his merit protect us). Let us proclaim the talent of the person who published this… so that future generations may know. Even though the previous printers prohibited other printers from republishing it, we have brought our claims to knowledgeable masters of the Torah and the law, and many permitted it. There is no infringement, danger of trespassing, or prohibition between regions. On the contrary, it is a good deed to enable those who are interested in slaking the people's thirst, and wish to enjoy the sweetness of the deeds of these holy people, because the founders are no more. We therefore decided to print it again, so that the people of today might have the merit of learning about their elders, and may their merit protect us and enable us to regain our strength, amen. (Hrubieszow, printed by Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and his co–workers.) 1817 [1], [31] pp., quarto, 21x18 cm, Rashi font.

The colophon reads: “By the typesetter, who is doing this sacred work faithfully. Yitzchak, son of Dov, of Laszczow, currently working in Hrubieszow.” The book was printed three times earlier in 1815, in Kopys, Berdichev, and Laszczow. (See my article on the printers of Laszczow in Kiryat Sefer, 12, pp. 241–242.)

- Tana De–Vei Eliyahu… has been out of print for 120 years, and is unavailable (there may be some isolated copies) and the printed copies contain endless errors, and lack chapter 4 of part 2; chapter 22 was copied by Rabbi Levi Yitzchak… head of the rabbinical court of Berdichev and Żelichów. By permission of the censor, printed in Hrubieszow by… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor of Laszczow and… Shoel Moshe Goldshtein, 1817. 129 pp., octavo, 18x10 cm. (Square letters and Rashi font).

Contrary to the printers' statement on the title page that the book had been out of print for 120 years, the book had been printed in 1798 in Zhovkva and Minkowitz, in Lviv in 1799, and in Zhovkva in 1808, i.e., four times in the twenty years prior to this edition. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, mentioned as living on the title page, actually died in 1810. However, the printers of Hrubieszow copied all this from the Zhovkva edition of 1798, which was printed during the lifetime of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak. At that time, it had really not been printed for 120 years; the previous edition had appeared in Prague, in 1677.

- Siddur Tefillat Nehora… we include both the Ashkenazic and the Sephardic versions so that all can use it…in Hrubieszow, at the press… of Menachel Mendl Finkelshtein… 1817. (Rivkind, Kiryat Sefer, Vol. 9, p. 526.)

The following appears at the end of Part 1: “This is the first part of Siddur Tefillat Nehora… according to Sephardic custom. Part 2… in Sławuta.” No date. The colophon on p. 2 is the same as that at the end of Part 1. Part 2 was also printed in Hrubieszow.

1818

- Me'or Einayim […] by Rabbi Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl and other Jewish communities, by permission of the censor at Hrubieszow, at the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow and… Shaul Moshe Goldshteyn, in 1818. 126 pp., quarto, 18x21 cm, Rashi font.

At the bottom of p. 126, the colophon as follows: “By the typesetter […]

[Columns 61-62]

Chaim, son of Eliezer, of Lviv, currently in Hrubieszow, and by the press operator doing this sacred work Daniel Ze'ev, son of Meir Segal (may his light shine), of Hrubieszow. The reverse of p. 126 includes the approbation by Rabbi Yosef Katzenelboigen, head of the rabbinical court of Uściług and surroundings.

- Machatzit Ha–Shekel by… Shmuel Ha–Levi Kelin (may his righteous memory be for a blessing) son of Neta Ha–Levi (may his righteous memory be for a blessing)… in 1818 (Part 1), printed by… Yitzchak Shlomo Zalman and his nephew… Shlomo Finkelshtein, by permission of the censor at Hrubieszow, at the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and his companions. 1818. 15 pp., octavo, 22x38 cm. Rashi font.

The book's title, part number, and name of the town are in red ink. The reverse bears the approbations of Rabbi Yosef Katznelboigen and Rabbi David Shalit, Moreh Tzedek of Hrubieszow.[29]

- Kotnot Or, includes and expands on Ein Ya'akov, Part 1 (order Zera'im), with the additions of Kohelet Shlomo. A comprehensive collection of all the legends and midrash texts throughout the six orders of the Mishna… done by… Ya'akov , son of Shlomo, son of Chaviv (may his memory be bound in the bundle of life)… now reprinted… by permission of the censor at Hrubieszow… at the printing press of … Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and … Moshe , son of Y. Tzikor of Laszczow and… Shaul Moshe Goldshtein in 1818. [9] 130 pp., quarto, 16x20 cm. (Square lettering and Rashi font.)

The words “Ein Ya'akov” and “Hrubieszow” on the title page are printed in red ink.

The following approbations are on the reverse page: by Rabbi Yosef Katzenelboigen, head of the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow and Uściług, on October 22, 1817; by Shim'on, head of the rabbinical court of Żelichów, in 1818; by the rabbinical court of Hrubieszow on October 22, 1817. Signed by David Shalit, Aharon Yitzchak Ha–Kohen, Mordechai, son of David, Shalit.

The colophon reads: “I will thank God… the worker at the printing press Yissachar , son of the deceased Refa'el… of Zhovkva, currently in Hrubieszow, by the typesetter… Chaim… son of… Eliezer… of Lviv, currently working in Hrubieszow, by the … typesetter Menachem Mendl, son of the deceased Baruch Segal, of Zhovkva, currently in Hrubieszow.” The colophon is followed by the “List of Errors,” and a statement by the proofreader Eliezer Segal.

- Kotnot Or, includes and expands on Part 2 of Ein Ya'akov (order Mo'ed to tractate Beitza)… (all exactly as in part 1). 246 pp.

In some copies, “Hrubieszow” in red ink is replaced by Mzeritch in black ink, and the title Ein Ya'akov is in black ink (Friedberg).[30]

- Kotnot Or, includes and expands on Part 3 of Ein Ya'akov (order Mo'ed to tractate Hagiga, and orders Zera'im and Mo'ed of the Jerusalem Talmud)… (all exactly as in Part 1, except for the letter bet in “Ya'akov,” in the date, which is not printed in large font.) 216 pp.

The names of the printers are omitted in some copies of this part, and “in Hrubieszow” in red ink is replaced by Mzerish (!) in black ink, and the title Ein Ya'akov is in black ink. There are no other differences in the title page or within the book (Rivkind in Kiryat Sefer, vol. 11, p. 388).

- Kotnot Or, includes and expands on Part 4 of Ein Ya'akov (tractate Shim)… (as in Part 1)… in 1819. 217 pp.

The colophon reads: “by the worker… the typesetter Chaim, son of… Eliezer, of the capital Lviv, currently working in Hrubieszow, and by the worker…on the printing press Pesach Yosef, son of…Tzvi, of łęczna, currently working in Hrubieszow.”

In some copies the words Ein Ya'akov are printed in black rather than red ink, and “in Hrubieszow” in red ink is replaced by Mzeritch in black ink; the Polish name “Hrubieszow” is missing.

There are no other differences in the title page or the book itself; however, the colophon reads differently: “by the worker…on the printing press Pesach Yosef , son of… Tzvi) of łęczna, currently working in Hrubieszow., by the worker… the typesetter Chaim, son of… Eliezer, may God preserve him in life) of the capital Lviv, currently working in Hrubieszow, and by the worker…the typesetter Baruch Avraham, son of…David, may God preserve him in life, of Hrubieszow. ”

- Kotnot Or, includes and expands on Part 5 of Ein Ya'akov (tractates Bava Kama, Bava Metzi'a, Bava Batra)… (as in Part 1)… printed here in Hrubieszow by the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow, in 1822.

- Kotnot Or, includes and expands on Part 6 of Ein Ya'akov (from Sanhedrin on)… Hrubieszow at the printing press… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow. (The numerical value of the Hebrew letters emphasized actually corresponds to 1820, if one of the bet letters is emphasized as in Part 5.) (I did not see this part, but have used the report of Y. Rivkind in Kiryat Sefer 11, p. 388). In some copies, “Hrubieszow” is replaced by Mzeritch (Friedberg).

- Kedushat Levi commentary on the Torah, left to us by Rabbi Levi Yitzchak (may his righteous memory be for a blessing), head of the rabbinical court of Berdichev, Żelichów, and the provinces, on the Torah…first printed in Berdichev by the sons of the author (may his righteous memory be for a blessing), but as the original copies are all gone we have reprinted it with the greatest elegance and beauty, for the community. By permission of the censor at Hrubieszow, at the printing press… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe , son of Y. Tzikor of Laszczow, and… Shaul Moshe Goldshtein, in 1818. (1) 78, 27, 15 pp., quarto, 22x18 cm. Rashi font.

On the reverse of the title page is the approbation of the Hrubieszow rabbinical court, dated February 26, 1818. The signatories are David Shalit, Aharon Yitzchak Ha–Kohen, Natan Aryeh Doyer, and Mordechai, son of David, Shalit.

The colophon is printed at the end of Leviticus: “By the worker, faithful executor of this sacred task, the typesetter Chaim, son of Eliezer (may God preserve him), of Lviv, the capital, currently working in Hrubieszow, and by the worker, faithful executor of this sacred task, the unmarried Pesach Yosef, son of Tzvi Hirsh, of łęczna.

1819

- Levushei Serad, a work comprising three booklets: Booklet 1 explicates rules of the sabbatical year and broken bones in fowl and animals… Booklet 2 explicates rules pertaining to lungs…and Booklet 3 includes a selection of common rules from the section on Yoreh De'ah… written by Rabbi David Shlomo Eibeshitz, formerly head of the rabbinical court of Soroki, now living in the Holy Land… at the press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and…Moshe, son of Y. Tsikor, by permission of the censor at Hrubieszow, printed here at Hrubieszow in 1819. (1) 102 pp., demi–quarto (28x23 cm.) Square and Rashi fonts.

On the reverse of the title page is the approbation by David Shalit of Hrubieszow, of July 25, 1819. (“The booklets have been printed for several years in Russia, but the original printers limited the printing, and received approval for that…however, several eminent rabbis agree that now the rulings of one country are not binding on other countries…”).

The title page and the end of the book bear the decorative element found in most books printed in Hrubieszow. Another, identical edition, based on this one, was later printed, but the names of the printers, the Hebrew and Polish names of the town, the common–era year, and the decorative element, are missing. In their stead, there is a design of two facing crowned lions; however, they retained the detail of the Hrubieszow edition. After meticulous examination, I concluded that this is a different edition, based on the Hrubieszow edition, but omitting the name of the printing press.

[Columns 63-64]

|

|

| Title page of Haggada Shel Pesach, printed at Hrubieszow in 1817 |

- Sefer Ha–Yashar by Rabenu Tam [written by Rabbi Zerachya the Greek]… the proper way of life and ethical teachings… has been printed several times but required updating… God inspired… Yehuda Leib (may his righteous memory be for a blessing) of Hrubieszow to remove the problems and errors… Hrubieszow, by permission of the Hrubieszow censor, at the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe, son of Y. Tsikor, in 1819. [2], 43 pp., octavo, 18x11 cm, Rashi font.

Ein Ya'akov, Part 4, 1819. See No. 16, above.

- Peri Etz Chayim written by… Rabbi Chaim Vital (may his righteous memory be for a blessing in the next world)… as heard from his teacher, the great rabbi Yitzchak Luria Ashkenazi (may his memory be for a blessing in the next world)… as previously printed in Korets and now printed with considerable improvement over the earlier editions… by permission of the censor, in Hrubieszow, at the printing press of Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe, son of Y. Tsikor, 1819. [1] 95 pp. demi–quarto, 35x22 cm. Rashi font. The printing was completed on January 29, 1819.

- Reshit Chochmah Ha–Katzar… Hrubieszow. At the printing press of Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and his co–workers, 1819. (Rivkind, Kiryat Sefer, Vol. 11, p. 388.)

1820

- Sefer Zechira Ve–Inyenei Segula… good talismans and medications and prayers to atone for nocturnal emissions… and removal of all dangers and sorcery… and concerning this world and the next world, and some tales… gathered … by Rabbi Zecharya of Plungé in Žemaitėjė. By permission of the censor. Hrubieszow, at the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshteyn, and… Moshe, son of Y. Tsikor, of Laszczow, in 1820. 48 pp., octavo, 19x12 cm, Rashi font.

- Seder Keri'at Shema with translation into Yiddish. Hrubieszow 1820 (Friedberg, Toldot Ha–Defus Ha–Yehudi Be–Polanya, p. 101).

- Avodat Ha–Kodesh… [by Rabbi Chayim Yosef David Azulai]. Part 1 is titled Moreh Be–Etzba, with the routines of daytime prayers and evening prayers… Part 2 is titled Tziporen Shamir, with some amulets and protective, beneficial spells… Takanot Ot Berit… compiled by… Ya'akov , son of Naftali Hertz of Brody…Hrubieszow. At the printing–press of Menachem Mendl Finkelshteyn and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow. 1820. 40 pp., octavo, Rashi font. I do not currently have the book with me, and have listed it here based on my previous notes.

- Shir Ha–Shirim… with commentaries by Rabbi Eliezer, son of Yehuda, of Worms… and by the gaon Moshe, son of Nachman (may his righteous memory be for a blessing).[31] In addition, there is a commentary and translation… By permission of the censor in Hrubieszow, at the printing press of Menachem Mendl Finkelshteyn and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow, in 1820. (6) 69 pp., octavo, 11x18 cm. Square font with diacritics, and Rashi font.

Friedberg erroneously states, 1817. See also G. Scholem in Kiryat Sefer, Vol. 1, p. 167.

- Tehillim, elegantly printed, cleaned of all defects… with sufficient commentary in abbreviated Yiddish…[32] By permission of the censor in Hrubieszow, at the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshteyn and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow, in 1820. [2] 208 pp., octavo, 11x18 cm. Original and translation are in square font with diacritics. The book's title and printing press location are in red ink.

- Tomer Devora, an important work by the rabbi and kabbalist Moshe Cordovero (may his memory be for a blessing) about the right path for a person to follow, his seclusion, purpose, and self–examination, so that the person may adopt the 150 orders of the ten Sefirot, and the thirteen higher attributes… by permission of the censor in Hrubieszow, at the printing press of Menachem Mendl Finkelshteyn and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow, in 1820. 14 pp., octavo, 11x17 cm. Rashi font.

1821

- Letter containing truths, enabling understanding of fables and elevated language, titled Ayelet Ahavim, as it is a fine instrument for understanding ethics, morals, and questioning… by Shlomo, son of David di Olivera in the month of Iyar, 1657.[33] Printed in Amsterdam in 1665. Its pages were prepared by… Avraham Moshe Beharabani… Shlomo Ha–Levi of Lublin. By permission of the censor in Hrubieszow, at the printing press of… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow, 1821. (4), 20 pp., (1) octavo, 11x18 cm, Rashi font.

- Haggada Shel Pesach with commentaries… one by the gaon Natan Spira (may his memory be for a blessing), author of Megaleh Amukot… another commentary by the gaon Shimson of Ostropol… more commentary by the gaon Elazar, author of Ma'ase Rokeach… by the gaon Rabbi Shaul, head of the rabbinical court of Amsterdam… by the gaon Yechezkel [Landau] of Prague.[34] Additional commentaries by renowned scholars whose names are not given… Compiled by me, Mordechai Tzvi of Zbarazh, currently in Zolochiv. At the printing press of… Menachem Mendl Finkelshtein and… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow. By permission of the censor at Hrubieszow, 1821. 18 pp., quarto, 18x21 cm. Square letters with diacritics and Rashi font.

1822

Ein Ya'akov, parts 5 and 6, 1822. See above, nos. 17–18.

- Tehillim, arranged according to the days of the week and the month, with commentary (Zohar, Rashi, with commentary on words in 78 and 305… collected… and between the psalms… answers… about the foundations… Hrubieszow, 1822. 240 pp., octavo. (Wachshtein, Minchat Shlomo, Part 1, p. 28, no. 138.)[35]

From p. 234 on, prayers and supplications.

1823

- Beit Ya'akov… commentary on Shulchan Aruch, Even Ha–Ezer, and tractate Ketubot… by Ya'akov (may his light continue to shine), head of the rabbinical court and head of the yeshiva of Lissa… may his learned accomplishments stand us in good stead… printed here at Hrubieszow at the printers… Moshe, son of Y. Tzikor, of Laszczow, and… Shlomo, son of David Lev, of Laszczow,

[Columns 65-66]

in 1823. (2). 51, (1), 32 pp., demi–quarto, 21x35 cm (Rashi font).

The page preceding the body of the text bears a poem by the printers, praising the book, written on November 5, 1822. It begins, “He removed the stone over the well of learning, his deeds are beautiful and his roads are open to others.”[36] The location of the press is missing in some copies (Friedberg).

- Sha'arei Teshuva by Rabbi Yonah Girondi, Hrubieszow, 1823. (Friedberg, Historiya shel Ha–Defus Ha–Ivri Be–Polanya, Antwerp 1932, p. 101.

Footnotes:

- Original note: Printed in Kiryat Sefer, Jerusalem, 1943–4, pp. 219–228. Return

- Original note 1: Antwerp 1932, 100–102 Return

- Translator's note: The texts of the original notes are provided in a separate list in col. 66. Return

- Original note 2: Kiryat Sefer, vol. 9, 432–439. Return

- Original note 4: See my article on the history of the Hebrew press in Laszczow (Kiryat Sefer, vol. 12, 238–247) Return

- Translator's note: There is no original note 3. Return

- Original note 5: See my article, no. 7. Return

- Original note 6: See in the list below, nos. 2,7,9, 11, 13–16, 19. Return

- Original note 7: See in the list below, nos. 6, 10, 12. Return

- Original note 8: See in the list below, no. 4. Return

- Original note 9: See in the list below, nos. 17, 18, 20. Return

- Translator's note: The text offers only the first initial of his father's name; the full name cannot be determined. Return

- Original note 10: See in the list below, nos. 30, 33. Return

- Translator's note: See footnote 12. Return

- Original note 11: See in the list below, nos. 3, 8, 32. Return

- Original note 12: See in the list below, notes to nos. 7, 14, 15, 16, 18, 33. Return

- Original note 13: See in the list below, nos. 1–3, 7, 28. Return

- Original note 14: See in the list below, nos. 9, 13–18, 212, 23, 24, 26, 34. Return

- Original note 15: See in the list below, nos. 4, 10, 25, 31, 32. Return

- Original note 16: See in the list below, 6, 8, 11, 19, 22, 27, 29. Return

- Original note 17: See the photograph in Friedberg's book, Table No. 3, no. 3. Return

- Original note 18: Compare in the list below, the comment to no. 5. Return

- Original note 19: Compare in the list below, no. 27. Return

- Translator's note: Ellipses without square brackets are in the original. Return

- Translator's note: Haggada shel Pesach is the Hebrew name of the Passover Haggada. Return

- Translator's note: Square Hebrew letters are a stylized form of the Aramaic alphabet. Diacritics are a mark, point, or sign added or attached to a letter or character to distinguish it from another similar letter, to give it a particular phonetic value. Rashi font is a semi–cursive typeface named for the commentator Rashi, and is usually used for printing commentaries. Return

- Translator's note: I was not able to determine the meaning of the parentheses and square brackets in many of these remarks but are related to specific aspects of the bibliographic descriptions of the printed volumes. Return

- Translator's note: The name that appears here as ‘Tsuker’ was earlier ‘Tsikor’. Return

- Translator's note: A Moreh Tzedek is an “auxiliary” rabbi who is responsible for making halakhic decisions. Return

- Translator's note: As Friedberg implies, Mzeritch is obviously a misrepresentation of Mezritch, the Yiddish name of the town of Międzyrzec. Return

- Translator's note: Moshe, the son of Nachman is better known by the name Nachmanides. Return

- Translator's note: Tehillim is the Hebrew name for Psalms. Return

- Translator's note: The Jewish month of Iyar is typically May–June. Return

- Translator's note: Haggada Shel Pesach is the Hebrew name of the Passover Haggada. Return

- Translator's note: I could not determine the meaning of 78 and 135, indicated by the numerical value of Hebrew letters. Return

- Translator's note: The phrase about removing “the stone over the well of learning” refers to the biblical Jacob (Genesis 29, 10). Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Hrubieszów, Poland

Hrubieszów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 17 Sep 2022 by LA

Hrubieszów, Poland

Hrubieszów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page