|

|

|

[Page 231]

by Yitzhak Sperling

Translated by Allen Flusberg

Death came abruptly. The tragic fate of my dear cousin Tzvi was sealed in only a few terrible seconds.

We have been orphaned—both the immediate family and the extended one. A devoted wife and good, precious children have been left behind…

It would never have occurred to me that in these difficult times that I am experiencing I would have to eulogize you, my dear relative. I have never called you Tzvi. This is the name that he picked up here. His real name was Tzadok. By this name I saw him frequently within our extended family.

He was born in the town of Dobrzyn. He was a member of an affluent family that owned a fur store and a workshop. It was a privileged, respected family, the most illustrious of the town. His father was one of the community leaders who for a while even served as mayor. Who was there who did not know or know of the family of Avraham Tzudkovich, this proud and active Jew?

It was in this atmosphere that the three brothers and two sisters were educated. All of them studied, acquiring knowledge in other cities. One of the brothers was an enthusiastic Zionist. Tzvi's oldest brother spent two years in the Land [of Israel] in the 1920s. But because he had trouble adjusting he returned to his town.

Tzadok was the youngest of the brothers. Already as a child he aspired to study in order to accomplish something, and in fact he did. He was integrated into all areas of life; he learned and read a great deal, especially Yiddish literature. In spite of the prosperousness of his home, his views were leftist. He was considered a Communist, or, as they called them where we lived, “Stalin–Communist”.

In the years before the war we would freely come and go into his home, and we would often discuss the course of the Jewish youth. Although he did not share our views, he always expressed a deep appreciation for Hashomer Hatzair[2] and for its educational values.

And in this manner he led his life in prosperity in our town. Until the year 1939 came, the year in which the Second World War broke out. That year anti–Semitism rose up in the towns of Poland. The Jewish population suffered greatly.

Once the war broke out all communications between us were severed. And then, at the end of 1943, as we were overcome with anxiety because of the Holocaust that had descended upon our people, my cousin Tzadok appeared in my kibbutz[3]. Looking at him was like seeing the mournful Jewish people and my extended family. The vast majority of our relatives and friends were already no longer alive.

Tzvi had a unique talent to recount and then tirelessly tell again of devastation and hardships: the expulsion of the Jews of our town, the looting and the humiliation. He pointed out all the details, like an artist who can make you envision living images: he was rescued from the Holocaust and wandered from one land to another, getting as far as distant Siberia. He was a political prisoner. When he was informed of the possibility of fighting against the Germans, he felt he should volunteer in the Polish army, under the command of General Anders, and in this manner he reached the Land [of Israel][4]. Here he came to the conclusion that after the crematoria and gas chambers we could no longer permit ourselves to graze in strangers' pastures. He decided to leave the Polish army, and he joined us. He changed his name to “Tzvi” and quickly integrated into kibbutz life.

Once he had established his family he moved to Kibbutz Dan[5], but after a short time he came back to us.

Since his return he was an industrious, active and conscientious member. He struck roots not only at work but also in various tasks assigned to him by the kibbutz.

He was a quiet individual who was well liked, cultural and refined: someone with values. He will be remembered as one of the best and most dedicated members that we have ever had.

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 232]

by Chava[2]

Translated by Allen Flusberg

Suddenly, on a clear summer day, on the morning of a bright day full of joy, I have been struck by a hammer blow: for me the heavens have darkened. The sun has just risen, but it is already dark: gloom, darkness in everything. Gloom in my heart.

…Is it really true? ...Has your voice actually been stilled, Abba[3], and will I never hear it again? Suddenly we will no longer see you among us, so cheerful, so kind and so devoted?...

Dear, beloved Abba: Is what the comrades[4] and Mother are saying true, that I will never see you again? Is it correct, that you have left us this way, without a single parting word, without saying goodbye?

Many times you and I have parted from each other, but this is a different kind of parting; this is a very long separation, an eternal parting…and so it is the cruelest one of all.

Ah…cruel fate. You have left me orphaned of a father, and I had no inkling, you gave me no advance warning.

“Abba”: this word will accompany me for the rest of my life.

You never permitted me to call you by your name, “Tzvi”.[5] You wanted to feel there was someone who called you “Abba”…

…For a long time you wandered among various peoples; you felt in the flesh what not many have felt or will ever feel. To us, you children, you recounted what had happened to you through rose-colored glasses, but I, Abba, saw and felt what these tales reflected. I looked into your glistening eyes that had seen so much, had observed so much.

And yet you came to the Land [of Israel], you found a wife, and then, and only then (when you were no longer young), you began to establish your home, your family, which was your only solace after all you had lost in the war.

…You, Abba, you had gone and left everything behind, but not of your only volition, Abba. You were not one who disliked life. Just the opposite, you have always loved whatever life you had. You loved work and you carried it out with modesty and devotion. You loved the people around you; you never aspired to greatness…you did what you were supposed to do discreetly, quietly, but with great reliability and dedication.

You left everything behind. Even so, nothing has changed, nothing has happened. Life goes on as usual, just as it was…

But I—I do not believe it. I look again and again; perhaps I will see some tiny change—it does not make sense that everything remains as it was…but Abba, you did leave everything as it was, you did not shake anything up, nor did you wreck anything. It is only our hearts that you have racked and broken. Our spirits are low, torn to pieces. A vacuum has been created in my heart, a giant rip…

Is it possible, conceivable that the right to say “Abba” once more in my lifetime has been taken away…Can this be?

Can anyone believe that my right to be in your company again, even only one more time, has been taken away, the right to get even a single fatherly kiss from you?

Will I not sit with you again in the twilight of evening, listening to the stories that you knew how to tell so well, that you loved to tell?...

I am proud of you that you were a good father to me: a concerned, devoted and loyal father. You were ready to give anything up as long as you knew that you were doing it for the sake of your children:

“What care I for silver and goldYes, Abba, this is what you were like, and as such you will remain in my memory all my life.What care I for precious objects and pearls

If I am far from my children?”

I am different from others, dissimilar from all my friends. They have parents, the most precious thing that a person can have. I am not like them: I have been destined to continue on with only “half”. Can a person walk on only one leg? Can he brace himself with only one of his arms?...

…I still do not believe it. Every day I still expect you at the time of day when you usually return from work. I see your figure before me, coming back from work, exhausted and tired (but even when you are tired you are not irritable).

So I can almost hear your cordial “hello”. I want to reply, “Hello, Abba”; but all at once all my illusions are shattered.

You do not come. I wait for you until evening. The sun has just set in the west. Darkness covers the face of the Earth, but still you do not come…and you—so people are saying—will never come again…

Should I trust what they say, my father? Are they right?...

No, no, no, I cry out inside, within myself: I do not want to believe it. But reality reveals all and forces me to stand before it, face to face.

How can I, when it is so cruel?

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 234]

by Yehuda Rosenwaks

Translated by Allen Flusberg

My sister-in-law, Chana Rosenwaks (née Bern) of blessed memory, was the granddaughter of R.[2] Avraham Neiszt, and was greatly influenced by his personality. Since she was orphaned from her father at a tender age, she spent much time at the house of her grandfather, the father of her mother Rivka. Her grandfather was a multifaceted personality who was well known not only for his wealth, but also for his Torah erudition; he was also enlightened and an enthusiastic Zionist.

Her mother, who was a magnanimous and pleasant woman, devoted to her home and children with all her heart, also greatly influenced the molding of Chana's personality. Her very close relationship with her mother and grandfather strengthened in her the sense of family bonds, a deep and fine sentiment that never left her.

When she married my brother Yitzhak of blessed memory, she quickly got close to our family, and she became like one of us, influencing us young children with her love and gaiety.

She was aware of everything going on around her, and once she sensed the continuous growth of anti-Semitism, she spurred my brother to leave everything behind and go on Aliya to the Land of Israel. It actually did not take much of a struggle to convince him. He too was fed up with the Poles and all that was theirs, especially after having tasted anti-Semitism during his service as a soldier among the Poles[3]. So he arose and came up to the Land, with Chana's encouragement. After several months she joined him, together with their four-year-old son.

Although conditions in the Land were difficult then, Chana was happy, and she did not cease rousing family members in Dobrzyn to follow in her footsteps. Her letters had the intended effect: my two sisters, my older brother's daughter and I—and also her sisters and her brother—all of us came on Aliya to the Land of Israel, and as a result we were rescued from the bitter fate of all those who had remained behind in Europe.

Throughout the years she remained a faithful source of support to my brother Yitzhak, inspiring all in her household with her personality. When my brother retired I encouraged him to come and settle in Kibbutz Dovrat[4] so as to remain near his daughter and grandchildren.

And even here, in kibbutz society, she quickly found her niche as a pleasant, cultured and industrious woman. Members of the kibbutz and the children, many of whom were wearing sweaters that she had made by hand, bonded with her in friendship and love.

Chana and Yitzhak passed away in the kibbutz and were buried there. May the clumps of earth of the Dovrat farmstead remain a pleasant resting place for them.

Translator's Footnotes

[Pages 235-237]

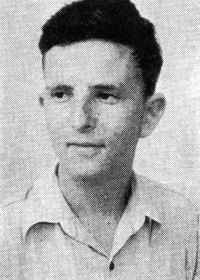

Born 17 September 1940

Died 29 October 1963[1]

by Eliyahu

Translated by Allen Flusberg

An Elegy for My Brother

The days pass, yet it seems as if the tragedy took place just yesterday.

We have been left in a state of complete confusion over the emptiness, and we ask: is it possible to speak of you in past tense: can I say of you that I had a brother, but no longer have him?

Seemingly these are ordinary days; all goes on just as in the past. Yet you are missing in all of it. In all moments of life, it is as if someone is shouting: how is it you are not with us?

At the time that I write these lines, at the time that I try to find words to express myself, your radiant image stands before me; and as I look upon it, a smile rises up on my lips, unintentionally. It is so pleasant to go back to those years, those happy years of childhood: walking at your side, my hand held in yours, as I gaze on you with a thrill in my eyes. And there are too many memories to count; they rise up in me and then sink back into the recesses of the past.

You were an incomparably devoted and kind brother to me.

I remember the days when our mother was ill, when our father was not at home. You knew exceptionally well how to fill in what was missing. You were a sort of inexhaustible source of stories, legends and magical entertainment, with which you knew how to enchant the heart of a little boy.

As the years passed I was always wondering: from where did you draw the strength to take it all? How did you overcome your physical limitations and yet were still able to lend a helping hand? And this is what you were like until your very last day: always struggling, always striving to be like everyone else, and never giving up.

You did not ever experience a moment of boredom. With unending devotion you invested all your strength in your work, and no one could stand in your way. We saw the expression of satisfaction on your face. We saw how anxious you were to do manual labor, and we did not have the heart to tell you to stop.

When you were late coming home and we were worried, we stood at the window, watching for your approaching figure. Suddenly we saw you on the tractor, with a line of wagons behind you, as you brought in the fruit of your labor. I saw our mother's eyes radiating, and a feeling of pride swept through all of us.

It seems to me that you never experienced more happiness among us than those last few years brought you. You reached the goal you were striving for: you were just like everyone else. And therefore you marched unafraid toward that large building, from which you never returned.

We became very close during your last days. I would walk over to you and suddenly feel a strong desire to grasp you with both hands. However, I saw the look of confidence and calm that was spread across your face, and so I held back.

I will never forget the day we parted. I accompanied you part of the way. A warm handshake; and my extensive gaze followed your figure as it moved into the distance, my heart fluttering and my entire body trembling. In spite of the fear and concern, we were full of hope and faith. When I got the news that the surgery had been successful, I wanted to shout for joy. I felt a feeling of release after so long a period of nerve-racking tension. However those hours of gladness did not last very long. Like thunder the news came that your heart had stopped beating and you had lost your life. With that our happiness was lost, and we were left immersed in depression and enveloped in darkness.

Dear Yehuda! As we carried you to your grave, we were steeped in bitter pain yet determined to continue struggling and to remain faithful to your memory.

Your bright gaze stays with me whichever way I turn. The kibbutz that you loved so much followed everything that happened to you and now grieves for your loss.

May we maintain the strength to continue on, with only memories in our hearts.

Goodbye my brother, goodbye for all eternity.

|

|

| Yehuda Sperling |

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 237]

by his father, Yitzhak

Translated by Allen Flusberg

For evermore: two ordinary, simple, words, embodying within them eternity—life and death. This eternity created an abyss out of a beautiful, young and pure life, that of a blossoming youngster, whose plans for life were aborted, with cruel suddenness, at a time when the future had begun to embroider his heart's mysteries together…The thread of his life ended! The heart! Alas for the heart! It betrayed him, not holding up against the chisel of life—and it was cut down.

Is any consolation possible? No, forever no! The heart does not believe, nor can the hand write about this bitter truth.

Several times I began to write and to immortalize your name, our dear, beloved son. Is such a thing possible? Our home is filled with mourning and sorrow. We are still living with you, and we always will, as if you are still walking around among us, thinking with us. Is this at all possible? A young lad, sparkling with young life? To write about, to immortalize forevermore! A good-natured, gentle and pure son.

Many days have passed, long, restless nights, even months have passed—and it is true that you are not among us. I must overcome, grow strong, and bring back memories, chapters of your beautiful, peaceful but short life.

*

The end of the year 1940, the Second World War. Haifa is being bombarded by the Italians. Rommel is at the gates of the western desert. The German war machine is aiming to approach us. The kibbutz[3] is considering an evacuation. We have to evacuate the female kibbutz members to the agricultural settlements of the Valley[4]. The time came…and you were born, in Afula[5]. From your very first moment you were afflicted with a heart defect. Your development was difficult and slow, causing us worry and anxiety. Your build was weak, somewhat sickly, but your head of hair was blond, amazingly beautiful, filled with curls. A face that expressed gentle feelings: smiling, with good eyes, as if you already understood then what you were up against. You caught all the childhood ailments. Slowly you created a path unique to you among the children who were close to you. They showed you affection and love every step of the way. You grew up—and the defect with you.

And your mother! She gave you everything, all of her life! She ran back and forth from one doctor to the next, from one expert to another. Is it even possible to express what your mother gave you during the first half of your life? But when you reached the age of 12, your mother collapsed on that wintry evening when you had fallen off your bicycle and injured your lip…

*

You studied in grade school and high school, and you acquired knowledge. You knew what had happened at home and you were a great help. You had a great power of understanding, and a profound heartfelt desire to help others. You loved the kibbutz and all that was in it. You loved music. When you listened to concerts, your face took on a serious look that was particularly beautiful, expressing sublime feelings.

You grew up, and the defect with you. You went to register for military service; and when you returned home, with tears in your eyes, I understood our tragedy…You are not fit for the military. How and when will it be possible to build a life in the future? There ensued a long silence between the two of us. I encouraged you! Our mutual tears sealed a chapter in our lives…

Every year you went for an examination to get a diagnosis—until you reached the age of 23. Only twenty-three years and no more!

*

You were an unusually responsible individual. You fulfilled the Ten Commandments of Hashomer Hatzair[6], especially that of “Achiezer and Achisamach”[7]. You could not conceive how it might be possible not to help others. You liked to work, even the hardest work. You were among the first to go wherever you were needed.

I remember how when you were eight years old, you were walking on the lawn, crying bitterly. “What happened, my dear child?” I asked you, and the answer was: “The children's farm hens have run away, and I haven't got anyone who can help me.” I lifted you up onto my shoulders. The two of us took care of this and your beautiful face showed great happiness.

And you continued on from there: in the library, in the institute, the administrative office, in caring for the kibbutz archives, in the orchard sector that you got very involved in, with a special love.

You read and became well educated; you had a thirst for knowledge, in spite of your limitations. You communicated with children from abroad. You won many prizes, excelling in various crossword puzzles; you completed studies in accounting, which you did not like. Courageously you carried the burden of labor.

*

You had a good, healthy sense of humor. Your comments were witty and poignant. In spite of your great fatigue, you had a fresh spirit. You were a modest person, satisfied with even a little, and you stuck to tasks. You participated vigorously in the life of the youth unit of the kibbutz. You responded willingly to every kibbutz member. At a young age you were a public figure who maintained contact with the entire kibbutz. You got involved with all your heart in the orchard sector, and you became the one who was responsible for it. You willingly burdened your weak shoulders with tasks, and you held your own.

I recall our conversations, at home, on this subject. With great respect you spoke of the relationship to work and to that of the orchard sector in particular. You were full of excitement and energy. You loved your family—you brought it much respect. You repaid your mother with a love that was accompanied by twice as much concern and worry—and so also to other members of the family. You were shy and timid, but the look in your eye always reflected a sense of calm and great responsiveness. This is what you were like, our dear son.

*

Your last weeks with us were a special chapter in our lives together. When we were informed that there was no way to avoid this fateful step, we were struck with great anxiety. Yet we knew of no alternative, and with a heavy heart we decided on the fateful step.

We were very tense the entire time. Just two weeks earlier we had mourned our dear cousin Tzvi[8], of blessed memory. I said then: I am going through crazy times…as our son walked around in the hospital, waiting for what fate has in store.

*

We will never forget your last days in the hospital. You did not surrender. Your face was fresh, calm and smiling. You sang beautiful melodies, one after another. When we walked together, I did not have the courage to talk about what was about to happen, except on the last evening. You insisted that I be strong, that everything would be all right. You ate your last meal peacefully and quietly. And early the next morning I stood next to your white bed. I caressed you…you were already asleep. I came along with you to the surgery room, our hearts full of anxiety, anxiety…

On your deathbed, moaning deeply, you asked: How is it going? And who could imagine that your hours were numbered and that these were your last moments. The entire kibbutz, all of them were anxious for you. Members rushed to donate blood to save you. You greeted them with a smile befitting your nature and you good spirit. What affection the people in the hospital, who got to know you, showed. Many people conversed with me, praising your character. Nothing helped; nothing, our dear one!

When, the next morning, weary and frightened, I came to you again, to see you, to hug you—my eyes grew dark…They held me up…Yehuda is no longer with us! Not anymore!

*

From the wall your beautiful picture gazes upon us. Memories encompass us—memories of our lives together in our good, warm home.

We have been left without you…

We have been left mourning and bereft. You have been interred in the ground of our agricultural community, the place where you had hoped to build your future. Clumps of earth cover you. Your spirit lives on among us, and will continue to always!

May your memory be a blessing, our dear son.

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 240]

by Avraham Dor (Dobroszklanka)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

We were childhood friends. We studied together under Manus[2], who taught the smallest children, and later under R.[3] Nisan Melamed[4]. We lived not far from one another, and we met almost every morning on our way to the cheder[5]. Since school studies continued until evening, we spent our time together until the day ended.

Once we grew up, the bond between us grew stronger, since we were both members of the “Hakoach” Sports Club[6], and we would meet almost every day for football [soccer] practice on the sports field.

We excelled in the sport, and we were both on the first team. We appeared together in competitions in Dobrzyn as well as in inter-town matches.

He was a good, loyal friend, a good-natured person. How sorry we were when he left our town to go to the United States at the request of his oldest brother, Yechiel. But this was an unfortunate journey: because of a technical flaw in his immigration papers, he was sent back to Poland by the American authorities. How disappointed and depressed he was when he returned, how hurt and embarrassed.

After the branch of “Hechalutz”[7] was set up in our town and several entry visas (certificates) for immigration to Palestine were allocated to us, Nisan and I were among the first to receive certificates. I came on Aliya at the beginning of 1925, and Nisan arrived a short time later. Again we would meet, although now only on rare occasions, since we lived in different cities: he in Haifa and I in Tel Aviv. But when he occasionally came to Tel Aviv to take care of various things he used to come over to see me.

After establishment of the State we managed to meet more often. During these meetings we would usually reminisce about our youth. Just a week before he passed away I met him in his home on the occasion of publication of the Yizkor Book, a project we had worked on.

How shocked I was to hear from a relative of his, Asher Graner, about his death. A feeling of melancholy descended on me while his casket was being borne during his funeral, as I realized that with his end another of the good people of Dobrzyn had left us.

May his memory be preserved in our hearts forever!

|

|

| Nisan Fogel, of blessed memory[8] |

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 241]

by Bilhah Fogel

Translated by Allen Flusberg

He was born in 1903, in the town of Dobrzyn, Poland. In his youth he joined the Hashomer Hatzair[2] movement, and he immigrated to the Land of Israel in 1925. Like many other chalutzim[3], he suffered for the first few years, being unemployed. His family urged him to return home, but he would not agree to it. On the contrary: he did as much as he could to overcome the difficulties.

His good temperament did not leave him even in difficult times, nor did he lose hope. As a result his friends liked him and were bound to him. He was dedicated to his friends and worried about them quite a bit, particularly when one of them was in distress.

As soon as he came to the Land he joined the ranks of the Hagana[4], and he was active in it until the day he died, volunteering for every settlement and defense activity. He was among those who were engaged in “occupation jobs”[5] in Akko [Acre] and other places; and even later, when his lot improved and he was one of the regular workers of Solel-Boneh[6], he was among those workers who would go out to work in dangerous places.

With the outbreak of the Second World War he was sent to work in Safed, to construct the police building in Canaan[7]. He brought his family with him to Safed so that they would be nearby. When he was asked to go to work in Abadan, Persia [Iran][8], far from home, he did not hesitate very long, understanding that it was an hour of need; and he was one of the first to take the assignment on.

He did not tend to complain; always content, he filled our home with his cheerfulness and warmth. Indeed, he was dedicated to his family. He passed on to his children the values of the pioneer movement; and in actuality his children followed this path and established their homes in kibbutzim[9].

Nisan Fogel was fortunate enough to see the establishment of the State, something he had dreamed about so much.

One day, after he returned home, he felt unwell, and he expired. He died an easy death, only 49 years old.

May his memory be blessed!

Translator's Footnotes

[Pages 242-243]

by Avraham Dor (Dobroszklanka)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

I knew the family of Hirsh Isaac of Dobrzyn; and I got to know their son, Katriel, when I went out to his flower farm in the outskirts of the city of Kutno[2], for a year of field work.

How glad I was when, on one of his visits to Dobrzyn, at the end of 1922, he agreed to take me on in his farm as a student specialist. I had just completed my studies in a horticultural school that was in Tsenstichov[3], and I was seeking to utilize my education in a practical manner. Once he agreed I went out to the farm and began working.

Here I had an opportunity to appreciate several of Katriel's characteristics: his diligence, organizational capacity, wisdom and love for his work. At dawn he used to go out to the fields, to keep track of the growth of the plants and trees whose planting and growth duration he recorded very carefully. He would check the trees after they had been grafted, the roses as they grew and flowered, and most of all the vegetables: cucumbers and onions—produce that he sent to the central market in Lodz three times a week.

He was always trying to extend his knowledge of his profession. For this purpose he stayed in contact with the school that he had studied in, and with managers of the large flower gardens of Europe.

He became famous in the entire vicinity as one of the great experts in growing roses. Grafting was his strong point, and indeed he sometimes succeeded in obtaining new varieties that were not yet known.

He never tired. He labored from dawn to dusk, doing his work happily without losing interest. He was severe with anyone who was negligent on his job, demanding from each worker that he do the best he could.

The years of World War II, which he spent in exile in Russia, left its marks on him. They could be seen in his tired face and the melancholy in his glances. Having lost his wife and children in the ghastly Holocaust, he married again, seeking to reconstruct his life and start life over.

He immigrated to the Land of Israel and went back to his previous line of work on a farm and nursery in Ganei-Yehuda[4]. With his great diligence he succeeded in establishing here, as well, flower nurseries and magnificent fruit trees, serving as an example for his neighbors. It appeared that he had found himself again; he was active in his profession and was joyfully spending time with the son born to him.

Yet he was completely worn out after the horrors of the war and his years of suffering in the Russian Steppes. His heart failed him and gave out. Now the flowers and plants that he loved so much decorate his grave; with their blaze of colors they shelter the man who dedicated the best years of his life to them.

Translator's Footnotes

[Pages 243-245]

by Avraham Dor (Dobroszklanka)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

One of the modest, shy people, who devotedly, very quietly do what they are supposed to, without trying to earn any laurels: this is what Mordechai Goldberg, of blessed memory, was like. I knew him from childhood—his family and him. He was always a devoted, loyal friend who was willing, with all his soul and all his might, to help anyone.

Their house was located in the market square of the town; I went over there often, for we had become very close friends, heart and soul. And also for a while we were in school together, taught by the same melamed[2], R. Mendel Holtz.

When I was about to go away to study gardening in the school in Tsenstichov[3], he divulged to me that he, too, wanted to go there. At his request I approached his mother, who made all the decisions at home, to try to get her to send him with me; but for various reasons she wished to put the matter off. Unfortunately for him, and also for me, no opportunity for him to leave for studies ever came up again.

When I returned from my studies in Tsenstichov, we renewed our friendship and worked together in the town branch of the organization “Hechalutz”[4]; we also became members of the sports club “Hakoach”[5]. We met often, since we played on the same team and spent time together in various events.

We were active together a great deal in the “Hechalutz” movement, taking part in organizing various parties and performances that served as an important source of revenue. I remember Purim and Chanukah balls that we held in Golub, parties that drew large crowds. We transferred a major part of the revenues to the “Hechalutz” Center in Warsaw.

He played an active role in all these activities, performing his duties punctually and with dedication. For a while he served as treasurer of the “Hechalutz” movement, and on many occasions he would cover a shortfall by lending his own money to the cashbox.

We planned our aliyah to the Land [of Israel] together, hoping to get immigration visas (certificates). And indeed, when the two of us were among the first to obtain them, our joy knew no bound. For various reasons we did not immigrate together, but when he did come, following in my footsteps several months after I had gone, we began meeting and hanging around together, just like in the old days.

At the end of a day's work, in the evenings, he used to come over to my room, and together we would go out to take a walk along the Tel Aviv shoreline, or, as was customary back then, in the square next to Mitbach Hapoalim[6] on Allenby Street, where we would meet up with some people we knew and with immigrants who had just arrived.

After some time had passed, he got a position as a laborer to put up telephone lines, and he moved to Haifa for his work. Our paths separated, but we continued to meet from time to time. These were happy meetings in which we used to bring up memories of our childhood.

In the beginning of the 1930s he got married and also had a son, Noah. But a short time later he became ill, and his condition continued to worsen. He travelled to Heliopolis in Egypt for medical therapy, but did not find a cure there, either. Shortly after coming back to the Land he became ill again. He was brought to the hospital in Afula, where he passed away.

His untimely death was a hard blow to all the friends that he had been devoted to, heart and soul.

May his memory be a blessing!

|

|

|

| Mordechai Goldberg, of blessed memory[7] |

Translator's Footnotes

[Pages 245-246]

by his daughter, Leah

Translated by Allen Flusberg

When I recall my father as he was in those days when we were still living in the town of Dobrzyn, the image of our home immediately comes back to me: a home that was filled with a Zionist atmosphere and with activism for the Land of Israel. And above all else I remember my father's many activities, his tireless work to instill the Zionist idea in the hearts of the townspeople. Nor was it all preaching: he took his entire family with him and immigrated to the Land in the year 1933 as many of his friends looked on, shaking their heads and viewing this act of his as extremely impetuous.

More than anything he was aware of the suffering of other people and was ready to help them with all his might. In the early 1930s, when we were living in Bydgoszcz[2], his devoted himself entirely to taking care of Jewish soldiers who were serving in the Polish army and whose regiments were stationed in our town. He worked hard organizing a communal “seder”[3] for all the Jewish soldiers who were going to remain on their base during the days of Passover. He refused to disperse them among Jewish families as holiday guests, so as not to give them the sense of being charity cases…The communal “seder”, to which he devoted so much effort, was one of the most beautiful events in our town. And in addition we adopted two or three soldiers; they became close to us and used to stay over when they had leave.

When we arrived in the Land we went through the pains of adjustment that were the lot of many other new immigrants. Nevertheless, even here he attempted to live up to, in practice, the same ideas that he had always championed: He took his family, with all his many children, and settled in a completely desolate area, where he tried to establish an agricultural farm and to live by the toil of his own hands. Since he had neither experience nor knowledge of agriculture, this move of his had aspects of both pioneering and audacity.

He raised his children in a Jewish-Zionist atmosphere that has influenced their paths more than just a little. He lived to see grandchildren who continued to follow the very ideas that he had bequeathed to his children: whether in cities or in settlements, in education or in security. To his very last day he remained bound to his farmland.

May his memory be a blessing!

Translator's Footnotes

[Pages 246-248]

by Ben-Tziyon Epstein (of Dovrat)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

I knew Yitzhak from the time he came to the meshek[3] of Dovrat[4], since he got here only a short time before I did.

In 1954, when he had reached the age of sixty-five, Yitzhak and his wife Chana decided to leave Jerusalem and come to the Dovrat meshek. They wanted to be close to their children in the twilight of their lives, so that they could enjoy being near their children and grandchildren and have a warm relationship with them. And indeed their children knew well how to fulfil the commandment of honoring their father and mother.

Yitzhak and Chana had no trouble getting involved in kibbutz life and adopting a lifestyle that was completely different from that of the city. They struck roots in their new home very quickly, without any trouble. On the contrary, they very rapidly sensed the pulse of life in their new society, adapting and becoming part of it.

Certainly what helped them along was their Zionist education, which had brought them to the Land [of Israel] when they were still young, in the year 1920. They also knew how to guide their children toward pioneering undertakings, starting from a young age. And indeed to this very day their son and daughter are among those who have fulfilled the kibbutz ideal.

What I saw of Yitzhak in the meshek was his great diligence in work, his enthusiasm and persistence. Every day he sorted the mail and hurried to bring it to the post office in Afula; in addition he would take upon himself setting various matters in order for the meshek. And when he returned from the city he would fully immerse himself in the completion of work-related errands that had accumulated.

He was aware of everything that was happening in the meshek and participated in addressing all its problems. At the same time he did not sever his previous ties, and he very capably continued to nurture his connections with friends and family members in the Land and in the Diaspora.

With his great energy he succeeded, after the State was established and after the siege of Jerusalem was lifted, in setting up a charity and free-loan fund for people who hailed from his town. The fund developed well and it served, and continues to serve, as a great help to those who are in need of it, mainly new immigrants and survivors of the Holocaust. This project filled his heart with joy, and he told me about it with great pride.

He was among the active and energetic pioneers from the period of the beginning of the New Yishuv[5] in the Land, and he made many friends over a period of many decades, years of labor and participation in the Hagana. He loved to tell all about the days of the Hagana[6] in Jerusalem, in which he had been quite active during the 1920s and 1930s.

While he was living in the meshek he had to undergo surgery, and in spite of much suffering he continued his regular work, sitting at his work desk in the administrative office every morning, during the sweltering days of summer and the harsh days of winter. Nevertheless he was never in a bad mood; on the contrary, he greeted the early-rising kibbutz members with a cheerful good-morning. For this reason the kibbutz members liked him very much and appreciated him.

His life with his wife Chana could serve as a model for happy family life; his son and daughter appreciated him and reciprocated love to him. Often they would gather in his room during the evening, together with the grandchildren, giving him great pleasure.

Nor did Chana sit idle. She knitted for the children and the kibbutz members. During the sweltering days of summer she sat in the shade of the trees, working on her craft, her face radiant as she conversed with anyone that happened by, young and old, members of the meshek.

She very much liked to read books written in Yiddish. Many times she liked to talk about the books she had read, and in these conversations she demonstrated a deep understanding. She had found these books in the libraries of members of the meshek, who greatly valued the interest she showed in the writers and their works.

To this very day people mention Savta[7] Chana with great esteem. And is it any wonder? Many of the children and members of the meshek are still wearing the warm sweaters, her glorious handiwork.

Yitzhak and Chana struck roots in the meshek, and it seemed as if they had been among its founders. Their fluency in the Hebrew language, their positive attitude in every matter, their awareness of all that was going on, provided them with a special status as members' parents who had successfully been integrated into kibbutz life.

Yitzhak and Chana were laid to rest in the cemetery of the Dovrat meshek. Their memory remains engraved in the hearts of their children, friends and relatives in the Land and the Diaspora.

May their memory be a blessing!

Translator's Footnotes

[Pages 248-249]

by Avraham Dor (Dobroszklanka)

Translated by Allen Flusberg

I knew Avraham Rosen when I was still a youngster in Dobrzyn. And around the time I was about to leave for the Land of Israel I saw him together with other children, exuberant, completely carefree. And then I met him again in the mid-1930s, this time in the Land, when he was a new immigrant looking for a job.

It was not easy in those days to find work, and it was only after much effort that he was able to get a job involving hard manual labor. Yet very soon he adapted to the situation in the Land of Israel of those days, striking roots and trying to make an independent living for himself.

And indeed, as time passed, he got himself onto the “main highway”: his economic situation improved; he set himself up and was able to establish a nice home, filled with cheerfulness and innocence. Although it appeared that this man had achieved peace and prosperity, it was not meant to be.

His faithful wife, a devoted mother, came down with a malignant disease, and the doctors were unable to save her. He walked around sorrowfully as his wife's life faded away before his very eyes. I met him then, and although he did not recount his troubles to me, I was able to see the depth of his misery in his sunken eyes, his gloomy face. His wife was forty-eight when she died.

How morose it was in his house when I came to visit, during the “Shiva”[2], to comfort him while he was in mourning. Already then he confided in me about a weakness that he was experiencing and pains that he was feeling every now and then. Some time afterwards, I found out the bitter truth from one of his friends. I visited him again shortly before he passed away, when his illness had already almost completely consumed him…In torment and anguish he closed his eyes for all eternity.

How great was the grief over the untimely deaths of these lovely and pleasant individuals, an inseparable couple. The children were left orphaned; and even his friends, those who hailed from his town, felt an overwhelming sense of bereavement, as if they, too, had been orphaned.

Avraham was gone forever—a son and grandson of noble-minded parents and a grandfather—a member of an extensive family that had been the pride of the town.

Woe for the loss!

Translator's Footnotes

[Pages 249-252]

Translated by Allen Flusberg

The son of Menahem Ben-Tziyon and Feige Mindel, he was born on 11 Nisan 5680 (March 30, 1920) in the town of Dobrzyn, Poland. His parents were veteran Zionists. His father was active in the “Poalei-Tziyon” movement[3].

When he was 11 months old his parents immigrated to the United States. The family settled in Brooklyn, where he grew up and completed high school. Educated in the spirit of Zionism, he was proud of his Jewishness and glad of the atmosphere of freedom in the country that he lived in. For him Chaim Weitzmann[4] and Abraham Lincoln served as representatives of twin ideologies.

When the Second World War broke out, he was a student at a college in central New York. Immediately he left his studies to volunteer in the US Air Force. After graduating from a 9-month course with honors, he was appointed navigator with the rank of second lieutenant. Sent overseas, he joined the Allied Air Force in the Mediterranean region. He was based in Italy, where he met soldiers of the Jewish Brigade, became good friends with them, and decided to go on Aliya to the Land of Israel when the time was ripe.

He was a bombardier, and during his 13th action, over the oil fields of Romania, his plane went down and he was taken prisoner. He spent 13 months in a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany, near Dachau, until May 1945, when the camp was liberated by Allied forces. While he was still a prisoner an Air Force medal had been awarded to him and delivered to his father.

When he returned to his university studies he registered in the department of mechanical engineering, intending to graduate in a profession that would be suitable for a future position in the Land of Israel. He studied for two-and-a-half years. He had only one month of studies to go to receive his degree in engineering, but he chose to put it off in order not to delay, even for a single day, volunteering in the Israeli Air Force during the War of Independence.

During his years of university study he was active in “Bnei Brith” (the Hillel Institute) and in “Habonim”[5]. He excelled in several sports, and he was awarded a prize as the best, most skillful boxer in the student class of 1947-48. He liked art, participating especially in painting; his paintings of scenery, in particular, drew much attention. He also excelled in singing and in meditation.

He served in the Israeli Air Force for only a short time. He died a hero near Hulda[6] on May 30, 1948 and was buried in Hulda on June 1, 1948.

Cornell University of New York posthumously awarded him a degree in mechanical engineering.

By an Israel Defense Forces Chief-of-Staff Order of the Day, dated September 29 1949, he was posthumously promoted to Flight Commander.

|

|

| Rosenbaum, Moshe Aharon[7] |

|

|

| Family of Avraham Yaakov Rosenwaks[8] |

|

|

| Chaim Rosenwaks and his wife[9] |

|

|

| Yaakov Dratwa[10] |

|

|

| Chana Dratwa[11] |

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Golub-Dobrzyń, Poland

Golub-Dobrzyń, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 3 Oct 2017 by LA