|

|

|

[Page 54]

by Yosef Nesher (Adler)

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Rabbis, Persons, and Characters

When I was four years old, I entered the cheder of the rebbe Avraham Leib, the teacher of young children, like most of the children of my age. He was short, broad boned, with two koncziks. One had a wooden handle and four thongs, which he used to whip the child's legs under the table. The second konczik was a broad, thick strap made of strong, flexible leather. The rebbe would use it to whip the bare behinds of the child.

Yidel the teacher was the complete opposite of the rebbe Avraham–Leib. He did not maintain a cheder, but rather a school for reading and writing in Yiddish and a bit of Russian for boys and girls together. This was already the roots of a modern cheder, in a large building with rooms filled with light. The children played in the large playroom with joy and pleasure. The student became absorbed willingly and with contentment. Song came to me as naturally as Yiddish and Hebrew in my parents' house. I even merited to be appointed as the assistant of the rebbe Yidel in the study of Hebrew even when I was his student. It is perhaps because of this that my fine dream was to become a Hebrew teacher – a dream that was realized only in a small fashion.

The school of the rebbe Yidel was affiliated with the cheder in which chumash and Rashi, as well as introductory Gemara was taught. Reb Feivish, thin and slightly blind, was my Gemara teacher. It was solely due to his pedagogical abilities that he was able to take control of the wild class, whose entire purpose (according to the rebbe) was to play tricks. Indeed, there was no end to our mischievous plans – the weariness of the rebbe, his physical weakness, and nearsightedness helped us with this. Nevertheless, he served as an example to me regarding how to bear tribulations and pressure – never to complain to the Creator, but rather to bear and make peace with the difficulties with deep faith and acceptance of the decree.

Another wonderful personality of sublime culture and love of one's fellowman was the rebbe Moshe, the son of Kalman Ajzenstat. He had few students, but they were choice students, whose parents were able to appreciate Hebrew culture. He was nicknamed Moshe Kalman's. He brought to life for us the Tanach [Bible], the Megillot, Jewish History, Josephus, the past greatness of Israel, and its status throughout all eras. He instilled in us the desire to study, know, and become educated. He planted within us the sense of honor of being Jewish, and the virtues of honesty and self–respect, which Moshe Kalman's displayed in a wondrous manner.

There was another rebbe in Chorzele – Yechiel, who was old and lame. He taught Gemara and Tosafos

[Page 55]

at a high level. Contrary to the usual custom, students would go to him on Sabbath afternoons to read Pirkei Avot, or to have him read to use the legends and stories of Alfas, or other such things. He taught us to understand the deep, penetrating life wisdom of the authors of Pirkei Avot who set the paths for future generations, defining all their great volume of experience in short, clear, sentences that were straight to the point. Every tittle was a sea of thought and wisdom for grasping life.

I recall another wonderful couple from the period prior to the First World War: Shlomka Tovia's and Rashka. They were childless, but their entire essence was light. He would walk in the street with a good, modest smile on his face. His eyes would light up at the site of any child. He would caress the cheek gently and give the child a candy.

I recall the personality of Shlomo the Shammas. Shlomo, the son of the rabbi, only attained the status of Shammas [beadle], and was considered in town to be an example of “rights from the fathers” that backfired. He had a pleasant appearance. His body was shapely and powerful. His beard flowed over his chest, imparting to him the appearance of a person ideal for a biblical portrait, like Moses who broke the tablets in his great anger. However, Shlomo the shamash was always angry, in complete contrast to Shlomo Tovia's…

Another personality: Yaakov–Pesach. He had a handsome face, a fine body, and was calm on the outside and internally. Nevertheless, he was full of thoughts that were foreign to his surroundings. He was very much into esthetics. His environment did not understand this, and he also did not know about this. He had a vibrant soul, and he loved and understood music. He literally pined for it, and was always humming. Who knows what type of supernal worlds opened before him when he hid and listened to “the immodest voice of women,” when the daughters of the Blind David sang their wonderful songs.

Along with the aforementioned personalities, there were people who grew up and lived in the environment of the town, and added to its color during the course of their lives. There were also personalities who themselves created the communal picture – with their talent, dedication and deep trustworthiness for the good of the community. They could have taken their place and filled roles in large cities as well, but they ended up here, lived here, and fulfilled their duty here.

One of them was Reb Moshe–Aharon Gwyadza, who came to our town as the son–in–law of a wealthy merchant of the town, who worked in exporting fish from Astrakhan, Russia, but to everyone's surprise lived with his family in Chorzele. Moshe–Aharon was enlightened, infused with worldly culture, with a deep love for the culture of his people as well as the members of his people. He gave of his abilities to the entire city, and was a revered leader there.

The second was his friend and comrade, my brother Avraham–Michael. Since he was my brother, I can only describe him as a brother looks upon a dear, beloved brother. I left Chorzele at the beginning of 1919, and from what others told me later, he became even more refined than the image that was stored in my memory. My brother was a noble person, with sublime dedication and a heart full of love for every individual. The powers of tradition and wisdom blended together with him, and he dedicated everything to the welfare of the public.

[Page 56]

Three Occurrences

I recall three special occurrences from my childhood. The first – the appearance of Halley's comet[1], when people were talking about the end of the world, among us as throughout the world. The Jews of Chorzele reacted to the fear of the gentiles with mockery, for did not God promise in the book of Genesis that he would never bring another flood to the world – and the term flood includes all other calamities… Nevertheless, there was an elderly couple in Chorzele (who earned their livelihood in a covert manner: they wandered throughout the earth and collected money in an unknown fashion) whose faith was weak. Therefore, they spent all of their money to purchase all sorts of delicacies, and had a gluttony fest in their home, prior to the destruction of the world… News spread quickly throughout the town, and everyone went to the home of this strange couple, from where drunken voices of laugher and song were emanating.

The second occurrence: Weiser – a student wearing the customary gown (pelerine) that made a great impression in those days. He was summoned to serve as a teacher of the children of one of the wealthy families, and also conducted evening courses in Hebrew and Russian for the youth in general. At first, he earned the type of great admiration that such a personality could be given among the youth of a small town. However, with time, this admiration diminished. Finally, he assimilated among the gentiles of the town, and this aroused a storm against him. He became ill and died while residing in the home of a certain Christian family. The gentiles admitted that he had converted to Christianity prior to his death. The Jews claimed that this was a transgression “for the benefit of the cross and Christian love.” The gentiles of the city conducted his funeral as a sign of the “sacrifice of the apostate.” High level clergy from outside the town and crowds of people from the region participated in the funeral. This was a day of mourning and shame for the Jews. The stores were closed, and the Jewish residents closed themselves into their houses out of a feeling of both fear and anger.

The third event: the aliya to the Land of Israel of three of our townsfolk: Mordechai Ajzenstat of blessed memory, and, may they live, Eliezer Mar–Chaim (lives in Jerusalem), and my brother Simcha Adler (lives in Haifa). This occasion of aliya to the land of Israel became an event that aroused a great deal of discussion, the echoes of which continued when the letters and bottles of Carmel wine for Passover arrived to their families.

During the First World War

I was 12 years old when the First World War broke out. A Russian colonel, who was an officer of the border patrol, appeared in the marketplace in the evening. He summoned the townsfolk to come to assist him in loading up his belongings and government property on the wagons that he had prepared. Early the next morning, my brother Avraham–Michael returned from Warsaw with the intention of crossing the border to Germany to save himself from being drafted into the army for the war that was about to break out. My brother Aharon, a few friends, and I accompanied him to the German border. He entered Germany using the normal border pass that the residents of the border district on both sides possessed.

When the war broke out, a strange, worrisome quiet pervaded in town, for all government authorities disappeared suddenly. The elite “dragons” with their horses disappeared, as did the captains. The orders for meat

[Page 57]

for the battalion ceased along with their disappearance. Customers disappeared from the shops. Opportunities for the tradesmen to work disappeared. Commerce quieted. Unemployment pervaded, and border smuggling ceased. The wealthy people were the first to start wandering, followed by the shopkeepers with their stocks of merchandise. This was followed by a wave of general wandering, all the way to the poor people of the town. Only few remained, stubborn people who did not want to leave their nest. These were lone lads, whose families had left. There were two grandmothers from the wealthy Sirota family, and it seems me also the Mar–Chaim family. My family also remained, for we had nowhere to go. What place in the world could absorb a cantor–shochet without a Jewish community? We fed ourselves from the produce of the field, and the abandoned gardens. We hunted fowl and small cattle who were wandering the streets without owners. In truth, we lived without worry. For us youths, this life was pleasant enough – until we too left the town.

At first, we were a virtually closed area from a military perspective. At times, Russian scouts appeared, and within a few days, German scouts appeared. This repeated itself. However, this tense calm was shaken up when a brigade of about 200 Russian riders appeared one Friday in the marketplace. They performed guard duties along the border road, which ended next to the house of Tanchum Kowel. The Christian cemetery, which was located half way to the border, was at such a height that could see the entire area from there. About 30 Germans moved in their daily fashion toward from the border road to the town, and apparently did not know about the Russians. When the Germans reached the house of Tanchum Kowel, the Russians broke out in calls of “Hurrah” and attacked them with drawn swords. The Germans began to flee to the large field next to Tanchum's house, which bordered the synagogue. They indeed succeeded in this. This battle experience evidently shook up both sides: the Russians left immediately and were not seen again, and the Germans also did not appear for three days. However, for the remaining Jews of the town, this event caused fear and apprehension. The wave of departure increased, to the point where the city was virtually empty.

Rows of Russian pedestrians began to stream en masse toward the German side, and it seemed that they would strangle Germany with their hats. Four Poles (Nijewski, Narski, Sopieski, and Pakorski) passed through our town, followed by cannons with heavy ammunition. Innumerable supply wagons followed them, with many Jews serving as the suppliers. The conquest of the border district of Eastern Prussia was accompanied by the pillage and plunder of the German civilian population. The far–off, faint thunder of the cannons told about what was happening on the front. However, suddenly on Thursday evening, the reverse escape began, and continued throughout Friday. Calm pervaded on Saturday, interrupted from time to time by Cossacks fleeing on their small, nimble horses. Isolated soldiers, tired and desperate, gathered in the marketplace in the afternoon. They were forlorn escapees from a powerful, confident force. This was a sign of the famous victory of Hindenburg in the Masurian Lakes[2].

Following this, there were several more battles between Russian and German units, who engaged with each other within the bounds of the town and the region. The situation became more difficult day by day. We decided to leave

[Page 58]

the town, but only the Polish farmers had wagons, and they did not want to travel. It was decided that I, being 12 years old, would go to the villagers in the region to seek a wagon. I wandered from village to village for several days. The farmers related to me with mercy, fed me from the little bit that they had, and let me sleep in their houses. In the meantime, my family began to worry about me, since they had not heard from me. Then my older brother Aharon went out to search for me. We met under a frightening situation: as he was being held in the hands of two Cossacks, beating him and shouting that he was a German spy. I jumped toward him but was tossed to the side. Suddenly, a Polish shopkeeper from our town appeared. He knew us, and began to intercede in a very serious manner in favor of my brother. This intercession saved his life, but he had to give up his fur coat and all his cash.

Not far from Chorzele, there was a sawmill for trees of the forest, owned by a Jew. It was next to the village of Duczymin. The manager of the sawmill made sure that there was a minyan there for approaching High Holidays and festivals. He invited my father to his home and sent a wagon to fetch him.

On the Threshold of Renewed Life

Whereas 300–400 Jewish families left Chorzele before the First World War, only about 200 families returned to the town after the war. Nevertheless, the youth began to develop cultural and communal activities, to collect books to found a library – of course in secrecy out of fear of the adults. The youth were so enthusiastic that, despite the extreme restrictions, they rented a spacious premises with three rooms and established a library. In essence, this was a cultural center. They gathered there to hear lectures and participate in discussions that broadened their horizons in worldly knowledge. They would hold “Postcard Evenings.” Throughout the week, written questions would be placed anonymously into a chest. A gathering would be held every Saturday night to give the responses. Hebrew courses and even a choir were also organized. The evening gatherings in our cultural center forged the social life and saved the youth from the dangers of boredom and despair that were liable to take hold of the residents in a small, remote town, which had almost been destroyed and was also struggling from an economic perspective.

The Jewish shops once again provided sources of livelihood for the townsfolk, and enabled them to continue their lives of spiritual values, via the reestablishment of the religious, social, benevolent, and charitable institutions. Everyone, from young to old, was involved with these institutions. I remember an unforgettable incident when David Richter and I were serving as night guardians for a sick girl, having been send by the Linat Tzedek Society (we youths were the primary active force in this organization). The sick girl was the granddaughter of the rabbinical teacher of holy blessed memory, and her illness was severe. Her mother, the daughter of the rabbinical teacher, who was tired and without energy, lay down to rest a bit. After about an hour, the woman jumped up from her sleep and shouted out joyously, “The late father of the girl appeared to me in a dream, and told me that the girl will live!” This was indeed a critical night for the girl's illness, and she arose from her bed a few days later.

With time, the number of residents increased, and the owners of the burnt buildings began to rebuild their homes anew,

[Page 59]

larger and nicer than previously. An itinerant dramatic troupe, most of whose members originated from Łódz, all young, pleasant, and talented, appeared in town at that time. From them, we learnt what was possible to do on such a constricted stage as ours. The visiting troupe left Chorzele, but its leader, Ber, remained. He was a man of culture, with a great deal of knowledge. He gave classes in German, and set up a troupe from among the townsfolk, exposing valuable dramatic forces from within ourselves. We put on many performances, all of which breathed a breath of life into the town, even though the Orthodox circles were opposed to this.

Another event broadened the cultural horizons of the town. The Germans drafted workers from the Polish–Russian border, and five young Jewish work foremen arrived in town. All of them came from the area of Baranovici, and had experience in communal service. They would spend their day off, Saturday, in Chorzele. They conducted public debates in parliamentary style in the cultural center, for there were Zionists and Bundists among them. Both sides presented their thoughts in a calm and logical fashion, preserving mutual respect and order. From them, we learned that heartfelt and warm relations can exist even where there are differences of opinion.

At that time, the youth in our town were for the most part non–partisan, and everyone worked together for cultural matters. One day, a youth named Hendler arrived from Maków as a partner in the iron utensil shop of his brother–in–law Naftali Ajzenstat. He approached me, as the Hebrew teacher in the town, and recommended that I found a Zionist organization. Such a thing was liable to endanger the social cohesion of our cultural center, but the idea enchanted me, because the need for Zionist activity had been sensed for some time already. I took my sister Hagar and my brother–in–law Shlomo Herzog, Libe and Sheina Leah Scher, and others into confidence. When we reached 15 individuals, we convened a top–secret meeting in the forest, and this is how the first Zionist organization was founded in Chorzele. The founding of this organization aroused the opposition of several of our members who were already out in the world at large and were numbered among the supporters of the Bund. They claimed that this would create a schism amongst the youth and destroy the existence of the cultural center. This internecine battle grew stronger and led to the rental of a different premises for the Zionist organization. The dispute quieted after some time. Both institutions existed in fine fashion, each functioning within its confines. The Zionists were the active force in the entire town as well as in the cultural center.

The war continued in the battlefields, but Chorzele was quiet. The youths were lacking in activity, so they became active in matters of culture and the organization of the Zionist movement. The connection with the headquarters in Warsaw was strong. Chorzele sent the writer of these lines as a delegate to the regional convention in Mława. Hebrew courses for adults and youth were opened, and a special library for the youth was created. The students of the courses chose a committee to conduct their affairs. I was their counsellor and teacher.

We organized performances, plays, and evenings of culture and song in which the students participated. The organized excursion of the youth on Lag B'Omer had a great impact. We imbued a great deal of energy and effort into preparing for it: the children learned to march in formation, we learned Hebrew and Yiddish songs as well as games. On the morning of Lag B'Omer, all the youth as well as many adults gathered at the Zionist organization building. The parade

[Page 60]

was organized. The counsellors and onlookers surrounded everyone, and we prepared to set out. Several Poles who were unable to make peace with the joy of the Jews came in wagons to break up the rows, but they encountered a strong, unmovable stand. They were force to back off. This event raised our profile amongst both the Jews and the gentiles.

The shops in the town were closed. When the parade set out onto the streets of the town, it was accompanied by young and old, and tears of national pride welled up in the eyes of many. The parade arrived at the Rembelianek Forest in peace, and we spent the entire day singing and playing games.

One winter afternoon, a young Pole arrived in the market and asked about the leadership of the firefighters. He gathered together Jews and gentiles and informed them that the Germans had lost the war, and the Poles have decided to take the government into their hands. An independent Poland was established. The Polish youth immediately began to gather in the streets and take the weapons from the Germans. The Jewish youth understood the danger that was liable to threaten the Jewish population during the inter–government period, when the Polish youth organized themselves within one hour to remove weapons from the Germans (most of whom would have preferred to give the weapons to us rather than to the Poles). In the evening, we organized a self–defense organization to protect us from our new “overseers.” We had weapons and the knowledge of how to use them. The Germans left the city at night, and nothing happened over the following days.

Renewed Poland began its first steps in oppressing its Jewish residents, but there were Polish leaders who understood that they must impose order. They decided to conduct democratic elections for the local government institutions, and a directive came to Chorzele as well to elect the leadership of the town. In the evening, the gentiles entered the town school to elect the leadership, without thinking at all about the Jewish population. However, we organized ourselves and sent 70 youths to the school for the election meeting. Moshe Czwirkowski of blessed memory explained to those present, including agents of the central government, that the Jews of the town demand proportional representation in the leadership of the city and its institutions. At first, the gentiles were astonished about the brazenness of the Jews. Later, a debate ensued, and we stood our ground in an uncompromising fashion regarding our demand. Finally, we attained what we demanded. The gentiles understood that they had no idea about town economics, and hoped that the Jewish minds would organize everything. Indeed, the administrator Avraham–Michael Adler served as the representative of the Jews in the town council until the Second World War, and the Polish mayor did not move to the right or left without his advice.

I left Chorzele in 1919, when the town reached its pinnacle even though the poverty was great. The Jewish community and the youth were active at that time in a full social and cultural life – it was a vibrant life. Today, the town certainly continues to exist, and perhaps even to develop, but its Jews are no longer there. May their souls be bound in the bonds of eternal life.

[Page 61]

With holy trepidation, I present this

Forgive me for the dearth of my ability

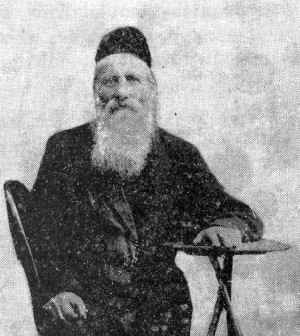

The Prayer Leader

He was tall, broad shouldered, with great strength. He had straight stature – he stood upright in front of everybody, except for his God. His broad beard flowed down, decorating his so good, good face. His large eyes, slightly weary, would peer at you with a strong, penetrating, and understanding gaze, as a smile settles upon his face.

He was the prayer leader, and he lived his calling, both as a position, as well as in all its details.

The shochet [ritual slaughterer]

The shochet's primary responsibility was toward the community of consumers. Kashruth was a cornerstone of the tableau of Jewish eating, and the shochet was willing to make any sacrifice and suffer anything for the maintenance of kashruth. The butcher and his family were living people, and any event of an animal being rendered treifa[3] would cause them a serious loss. If they had the poor luck of having several incidents of treifa happing consecutively, their livelihood was liable to dwindle down to the point of lacking a loaf of bread.

The most difficult situation was a case of uncertainty, when the lungs or liver were presented for inspection at the behest of the city rabbi, the rabbinical teachers, and the shochtim. The butcher would repeatedly blow up the lungs with his mouth, as the inspectors watched the inflated lungs. Fear and trepidation were in the hearts of everyone: the fear of feeding non–kosher meat to Jews on the one hand, and the fear of causing serious damage to a Jewish person on the other hand.

I am sure that the feelings of my father blended with those of all those involved in the judgment, but before my eyes, my father stands with a broken heart, for the animal was rendered a treifa.

The Cantorial Position

It is impossible to describe the connection of our townsfolk to music and song, which was expressed in some many varied ways: in the performance halls, musical productions, radio, and other means.

Our townsfolk lived very centralized lives, albeit also honorable and difficult. One would hear about the world, the world would call to him, and he might even succeed at times to come into contact with it or peek at it. However, these were all small snippets, from which a dream image, with shining light, could be formed. The dismal reality of the Jewish person, who was afflicted with the shame of the exile and lack of power, with extreme lack of horizons, with disgrace, poverty, and lack of options: only one thing remained – the dream. The angel of imagination covered enveloped him with his charm, and he caused him to dream of the Messiah, utopia, and Old New Land[4]. In the interim, however, the heart was overflowing with oppression and disgrace, with no solution. Then there was song, melody, hymn, and prayer, which broadened the heart, relieved the agony, and lifted the spirits on the wings of hope…

[Page 62]

It was the month of Tammuz. The heat caused weariness and dryness. The 17th of that month was a day of fasting and mourning, opening the flask of tears. Then the stream began, the month of Av – the month of destruction and mourning, the nine days of hopeless anticipation, culminating with the commemoration of the destruction on Tisha B'Av. The agony of “How has sat in desolation”[5] was barely assuaged, when the month of Elul had already arrived: a month in which the eyes were afraid and the heart trembled like a fish in the waters… with the accounting of the soul… and the Day of Judgment…

|

|

There was something natural about it as well. The autumn turned things yellow, and evoked sadness. Weariness pervaded, and rain poured down. A grey pall fell upon the world, and the heart contracted and shed tears… it was night. The city was dark. Isolated lights flickered in isolation and loneliness… deepening the darkness… and suddenly – song!… In the home of the cantor, Rabbi Moshe–Shimon, the rehearsals for the High Holy Days had begun!

The cantor sat at the head of the table and smiled. One of his sons, the director, organized the outlines and prepared for his first lesson with the seriousness of a teacher. In the meantime, the singers assuaged their inquisitive tension by singing songs of mutual vexation, which were closed to all the people of earth, and only understandable by people of that class. Then the cantor banged on the table: everyone got quiet and the rehearsal began. Verses of song emanated from the mouth of the conductor. The singers repeated them over again until they merged together into a complete melody. The singers –– experienced and with a quick grasp – caught on and joined in. The townsfolk gathered around the house, eager to listen. They enjoyed the “again,” and “once again,” that helped them grasp the melodies. As befits “experts,”

[Page 63]

the pointers from the cantor and the conductor deepened their understanding and improved the outcome…

All strands of sadness disappeared. Joy fell upon the town.

The Singers

I knew three types of singers from my father's house.

The cantor was the father who worried about everyone, and the home of the cantor was their home. Indeed, the space was tight, but not too cramped for any of them.

The Cantor

When the time came, he approached the prayer podium with fear and trembling, to serve as the messenger of his congregation before the All Powerful. Around him were his choir, and the congregants of the full synagogue – the holy congregation of the City of Chorzele.

He was expert and accustomed to leading prayers. He enunciated each word in accordance with its meaning and its role in the mighty service: the prayer that had had been sung for generations, in accordance with the style and melody that was transmitted from generation to generation. He would instill his own style, in the manner of someone “standing to entreat with prayer and pleas on behalf of the House of Israel,” with his heart moved and his soul infused with fear on account of the gravity of the task imposed upon him. Every word is a world, and every expression is fateful. Every melody was a one–time creation, that would never return. With his great, deep, rich voice (he was a bass baritone, with his voice broad and soft as velvet) he would arouse his congregation to prayer, draw the hearts near, blending with the entreaties of his mission to merit forgiveness and pardon, and a good year from the Father, our Father in Heaven…

The Day of Judgment

The Torah Scrolls from the morning service were placed back in the Holy Ark. There was tension and quiet in the room…

[Page 64]

The cantor stood silently in the center, wearing his white kittel and enwrapped in his tallis, with his eyes closed, stripping himself of the “current reality” and waiting for the wave to come, the wave that would carry his prayers to the Above…

A groan… and silence, as thin as a Heavenly Voice, without words, lifted his melody of supplication throughout the building. It descended, and ascended, reaching all places. The rhythm was repeated, strengthening and weakening… the congregation and its representative entered a sublime state. Their soul opens up like a flower before God… And then, the words flutter up in lamentation and subordination, like a bird with weak wings: “Here I am, poor in worthy deeds”[7], and suddenly, cry of pain, “I am trembling and frightened…”, and then, without energy, “From the fear of He Who is seated upon the praises of Israel”…

The seven–year–old child tucked his head into the door of the lectern – moved, trembling, and frightened. The congregation, imbued with fear, stood enchanted, given over to the mercies of the Lord.

Unetaneh Tokef[8]

Like the flow of a thousand streams, the voices of the worshippers pour out in a unified prayer. The group of frightened children wander about so as to find support in unity. Slowly, everyone quiets down. A groan still comes up from the heart, and stifled weeping can be heard from the women's gallery. This also stopped…

From the depths, the voice sounds out, quietly, stifled in its fear, and in acceptance of Divine justice, “It is true, it is true, that You are the judge, the judge, the judge the judge –– –– –– and the one who proves, the one who knows, and the witness.” Every word is frightening. Every word instills fear. One by one, the recognition of the dangers awaiting man in his sin and judgment are declared, as he stands without protection, without assistance (the Satan accuses, and the sins are the weapons in his accursed mouth…) He calls to God to help him out of despair… withered to the point of the nullification of the soul.

Then, a crack appeared in the iron firmament, and the splendor of heaven penetrated their hearts as an elixir of life with comfort and a promise… The prayers were taking hold in the firmament as talons grasping for salvation, reaching toward the Throne of Glory… Life returned to the soul. There is a solution. There is hope for man. The shout of encouragement broke out from all the worshippers: And repentance, prayer, and charity avert the harsh decree! The prayer leader comforted, graced and aroused his congregation to return in repentance with a full, upright heart, to prayer with all the powers of the soul, to open their hearts to charitable deeds that they would perform, so that they would benefit from His charity. Hope increased, and faith for a good verdict encouraged the hearts of the worshippers, as the choir broke out in, “There is no end to Your days…”

… Astonishment On the Day of Judgment

Our Father in heaven! On one Day of Judgment, the iron of your firmament hardened. Your glory did not shine upon your children. The prayers of Israel were caught up in the taloned fingers of emptiness, and did not reach Your throne. Destruction fell upon your nation, with none surviving.

… And Your rainbow sung out a promise from the cloud, that another flood should not come upon the world for its sin.

Only Your children were wiped out in the flood of blood – their own blood. The pure prayers were like souls wandering and lost

[Page 65]

in perplexity. The astonishment penetrated with thunder, but without a voice: “How could such a thing happen, Master of the Universe?” Father, Daddy, Why?!!!!

My Father

When my father became old, and no longer had the energy to serve as prayer leader, he took a staff in his hands, and went from house to house, knocking on the doors and the hearts of those who still had a loaf of bread in their basket – on behalf of those who had only hunger in their homes.

Silently in the evening, a hesitating hand knocked on my father's door. Faces pale with want and shame appeared at the door, with eyes of despair… but when the person left, his hand was encouraged, and his heart was a bit lighter. The pain was shared by both of them – the communal emissary and the child of his community…

The Prayer

My Father in Heaven! Open my heart, broaden my hand, and those of the generation to follow. And with this, the splendor of the soul of my father and rabbi, Moshe Shimon Adler of blessed memory, the cantor and shochet of the holy community of Chorzele, shall shine in splendor.

Translator's Footnotes

by Aharon–Wolf Nafcha (Kowal)

Translated by Jerrold Landau

In memory of those from Chorzele who have no survivors to remember them.

Remove the shoes from your feet Your muscles will weaken, For the Holocaust that was in your day Upon your motherland And over the destruction of your sanctuaries For the survivors of your nation And over the loss of your parents, And for the peace in your world And over the murder of your children, We will cry out! We will shout! We will scream! And over the uprooting of your daughters We will flash like lightning And over the tearing up of your children Over the image that was erased And over the disgrace of your God And over the house that was broken And over the honor that was melted And over the child that was strangled And over the blood that was spilled That such things shall never happen again.

[Page 66]

And in memory of my revered mother, Miriam–Zelda the daughter of Yisrael–Chaim the Kohen Anish; my sisters; my revered father Tona the son of Aharon–Wolf Kowal of holy blessed memory; of clean hands and pure heart, their soul was never taken with vanity, and they never swore falsely (Psalms 24).

From the Mouth of my Father

“May their eyes be dimmed so they cannot see, and may their loins constantly slip” (Psalms 69:24)

It was in the year 1900. Because of its unique geographical location, the residents of our town, especially the Jews, earned their livelihoods from smuggling. My father, like many others, would transport, with his wagon hitched to horses: a mixture of fruits (from Russia to Germany), and sacks of coal (from Germany to Russia). There were secret crevices in the corners of his wagons in which silver ingots were hidden. From this, our livelihood was bountiful in those days.

One Thursday, when my mother went to purchase fish for the Sabbath, the fisherman said to her that he was prepared to exchange his proceeds from selling fish for six months for one act of smuggling carried out by my father. Since these words were spoken in public, my father decided to go to ask a religious scholar about this – the Rebbe of Novominsk, of holy blessed memory. The Rebbe answered him, “There is no merit from the holy Psalms regarding what you say, that their eyes should be dimmed so they cannot see. For Your nation Israel requires sustenance.” My father returned, encouraged in in faith in the holiness of Psalms and in the wisdom of the Rebbe, and continued on with his livelihood…

One evening, on his way back from Germany with a load of coal in his wagon, the captain in charge of duties stopped him and said, “A complaint has reached us that you are engaged in smuggling. Therefore, we will conduct a search of your wagon.” A group of soldiers was summoned. They took down the sacks of coal, poured out their contents, dismantled the walls of the wagon and threw them to the ground with force, so that they could determine from the echo whether they were hollow. While the soldiers were still searching for smuggled objects, a piece of silver fell out from one of the secret corners. It glittered like stars at night among the piles of coal, as if it was winking and calling out the frightful words, “Here is the stolen object!”

My father was startled, but placed his trust in God and in the promises of the holy Rebbe. He did not stop reciting the verse, “Their eyes should be dimmed so they cannot see.” Suddenly, my father heard the Russian captain saying, “My friends, who hate toil, the lowly libel was false, oh you people without conscience. The libel against this man who works hard to support his family was false.” Turning to the soldiers, he said, “Help the man reassemble his wagon, and load the sacks upon it.” Finally he turned to my father, clasped his hand, and said, “You are free! Please forgive me.”

“Onward horsies… homeward…” my father prodded his horses. Indeed, the words of the Rebbe were fulfilled, “Their eyes were dimmed from seeing.”…

[Page 67]

The Sound of Torah – a Fortress Against Cannon Fire

It was 1915. The world war was at its height. People were traveling by foot and by vehicle on difficult roads. It was a large crowd, especially of our fellow Jews with their young children and belongings, escaping in fear from the victorious armies. The roads of Poland, normally dark, were now lit up by the light of the flames of the burning villages and the thunder of the cannons. My father and his family of seven were among the many wanderers.

This took place in one of the camps of wanderers in the city of Prosienica in the month of Shvat. On an extraordinary Yom Kippur[1], on a wooden floor in an abandoned room in the home of a Jew named Goliborda, I entered the world, in hunger, want, and poverty… When I was 15 days old, my family was forced to continue its wandering toward the capital of Warsaw. When we arrived there one early morning, my father got off the wagon, looked here and there, as if he was asking, “Who knows us? Who do we know?” He turned his eyes heavenward and said, “My God, from where will my salvation come?” The echo responded to him…

Suddenly an angel in the form of a woman passer–by appeared, turned to my father and asked, “Uncle, whom are you looking for?” She approached the wagon, lifted up the tarpaulin, and said, “A curse!” Then, she turned to my father, and added, “Uncle, do not move from here, wait!” After some time, a group of people appeared headed by a nurse in a white cloak, and ordered my father, “Uncle, follow after us.” Our wagon traveled to Gronica Street and stopped in front of a large house. We all got off, with our luggage. This was an institution for the homeless.

The great surprise took place in the afternoon. The director of the institution came to visit, and then, “Who did his eyes see, if not the resident that lives with us at home,” the rabbi of Ciechanów, Rabbi Braunroth of holy blessed memory. The two of them, he and my father, fell upon each other's necks, and wept for a long time.

We remained in that institution for more than a year. My father also found some work for himself during that time. When the news arrived that quiet pervaded on the fronts and it was possible to return home, my father again consulted with the Rebbe of Novominsk of holy blessed memory. The Rebbe's advice was, “Return home in peace, for the sound of Torah once again echoes from its walls.”

Throughout the years, rabbis, great in Torah and in fear of Heaven, lived in our house: Rabbi Koblaski of Włocławek of holy blessed memory, Rabbi Braunroth of Ciechanów of holy blessed memory, Rabbi Rosenstrauch of Olkusz of holy blessed memory, and after him, the holy Rabbi Mordechai–Chaim Sokolower of holy blessed memory – the father of Rabbi Ephraim Sokolower and of Avraham, Moshe, and Malka, who live with us in our country (may they live long). Indeed, when we returned home, we found that our house was still standing amongst the rest of the destroyed houses. (This fact was confirmed to me by the rabbi of Ciechanów, whom I had the honor of meeting in Israel a few years ago.)

[Page 68]

|

|

In later years, when Rabbi M. Ch. Sokolower was forced to leave our house as it was too small for his needs, a serious question arose with the heirs of the house after their father Aharon–Wolf Kowal. They were: my uncle David, my father Tona, and their sister Sara Jochet. The heirs were unsure how to ensure the continuation of the splendid tradition, so that the sound of Torah will not cease from this house, Heaven forbid. They offered the house to the holy Tzadik Rabbi–Yosef Shochet, who was known for his sublime traits as a fearer of Heaven. He lived in our house until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

Our houses of splendor, the synagogue and the Beis Midrash, also remained as fortresses, despite the internal ruin caused by the horses who had been housed there during the First World War. Two holy, pure, working Jews, took upon themselves the burden of the huge job and effort to restore these sanctuaries of ours for prayer and supplication: Matityahu Sokolower, the glassblower (the father of Avraham, Simcha, Tova, Malka, Mirel, and David, all living in Israel), and my revered father Tona Kowal, the smith. Both were “beloved and pleasant in their lives, and were not separated in death”[2]. They both served as faithful trustees for the needs of the community for many years.

The Good in Contrast to the Bad

Our house was situated between two Christian neighbors – Gutart and Chagan. When our town was evacuated at the time of the First World War, the army turned the splendid synagogue into a horse stable. Gutart's oldest son Tadek did not suffice himself with that. He took an axe and burst into our house of glory, breaking everything, not leaving anything untouched. However, when he raised his axe to bang it into the Holy Ark, he missed his mark and the axe hit his foot. As a result of this miracle, he remained lame, and he limped for the rest of his life (“This is the sin and this is the punishment”).

Entirely opposite was the opposition of the daughter of our neighbor Helena Chagan when the gangs of the infamous army of the anti–Semite Haller[3] looted, pillaged, and wreaked havoc in our town. Among their other sadistic acts, the Hallerists enjoyed capturing Jews to cut off their beards. At times, they would even tear off some of the skin of the chin along with the beard and peyos.

One day, several soldiers were running after Rabbi Sokolower of holy blessed memory to cut off

[Page 69]

his “locks of Samson” – his beloved, splendid beard that flowed over his cloak. As they were chasing pursuing him, Helena Chagan ran to greet them with a picture of Jesus in her hands, and burst out before them in hysterical screams, as she stood between them and the rabbi. She said, “I will not let you touch a man of God; go out to fight the wars of our homeland, and not against a defenseless person.” Her screams chased away the gang, and the rabbi was saved from the hooligans. Later that day, the rabbi invited his neighbors, my uncle David and my father, along with the noble Chagan family, and he blessed Helena that she should merit happiness, wealth, contentment, and good health for her humane deed. The Good God apparently heeded the prayer of the righteous man, for Helena received her reward. She married a good, wealthy husband, gave birth to successful children, and remained beloved by her family and anyone who knew her throughout all the years.

Love of the Nation and the Land

Our holy fathers, however, did not only live on miracles. Most of them were people of toil, who were blessed with skilled hands, as they synthesized Torah and labor in their day–to–day life. They also believed that work raises the man and purifies him. To this day, I remember our teacher and rabbi, the holy Moshe Ajzenstat, quiet and modest, who would hum the song that he loved so much, “Labor is our life, save us from every tribulation. Ya–chay–li–li– my toil is for me.” We then sensed his devotion to Hassidism and to his fiery faith. I do not know the extent that he knew the ways of the world, but the ways of the heavens were certainly clear to him through this song… for an eternal flame of the vision of the return to Zion, the vision of the complete redemption, burned in his heart and the hearts of those like him.

|

|

I recall a Saturday night many years ago, when several tens of Jews gathered for the Melave Malka meal in the home of the holy Avraham Szar. This was the farewell party for Reb Meir–Yaakov Weingort and his family before they made aliya to the Land of Israel. I still recall the taste of the grits that we ate, prepared by the mistress of the house, the holy Miriam Szar. However, seven times more sweet to us were the words of Reb Avraham Michel Adler, who said, “My brother Jews, if the joy is so great that we have merited, after many generations, to witness the beginning of the redemption with our own eyes, as our land is redeemed, our sons become builders[4], and the exiles are returning to it; if the joy is great for every pioneer who makes aliya, for every additional chick in our Land – then for us, observant Jews, the joy is doubled and increased. After we were exiled from our Land and our Holy Temple was destroyed,

[Page 70]

the holy Divine presence implanted itself in the hearts of religious Jews who believe with perfect faith that the Holy One Blessed Be He, the Torah, Israel, and the Land of Israel are all one. Our dear friend Meir–Yaakov carries in his heart the Holy One Blessed Be He, the Torah and Israel along to the land of Israel, as he returns the Divine presence to its rightful place.”

I recall the illustrious teacher and educator, the overseer of the Jewish National Fund, the holy Reb Mordechai–Mendel Friedman (the father of Chaya Segal, may she live), and the dedication with which he worked for many years for the sake of the redemption of the land. More than once, on a rainy Sunday when the cold froze the limbs, he stood at the crossroads dressed in a fur coat with a high collar – for what purpose? To collect the pledge from a guest who had an aliya to the Torah on the Shabbat morning in the old Beis Midrash (of Mizrachi), and was leaving town on Sunday morning to take the train to Warsaw. In such cases, he would say, “With one action, the Holy One Blessed Be He allowed me to fulfill two mitzvos – the redemption of the Land, and saving a Jew from the sin of failing to pay his pledge.”

How great a Jewish, popular, optimistic feeling, with heart and soul together, is embedded in the short poem that contains only two words, “Lechayim brothers,” that was sung by Reb Michal Berent the holy butcher, at any opportunity when people were sitting together. (He was the father of Mordechai Berent who lives with us in Israel). How much meaning was embedded in these two words, and how do we remember them today.

Our fathers, mothers, brothers, and sisters, the holy ones of Chorzele, were blessed with love of Israel, Torah, toil, God, and man. How great is our lot in this, how great is our heritage.

May their souls be bound in the bonds of eternal life.

Translator's Footnotes

by Yaakov Frenkel

Translated by Jerrold Landau

For all intents and purposes, Hechalutz was founded in Chorzele in 1929. However, around 1908, one of our townsfolk, Eliezer Mar–Chaim, was among the guards in the Land of Israel, and from then the atmosphere of Chorzele was fully directed toward the land of Israel. I recall that when I was 14 years old, I worked with a group of Jewish youths in straightening the Orzyc River during the time of the German occupation of the First World War. Our friend Yosef Nesher was among the workers, and we both felt at the time that we were preparing ourselves for aliya to the Land of Israel. The songs that we enthusiastically sang at the time were: “In the plow lies blessing and good luck”; “There where the cedar trees grow”; “I am a pioneer, a pioneer from Poland”, and other such songs. Thus, in 1916, when all the routes were closed and the entire world was occupied with bloodshed, we worked, sang, and dreamed

[Page 71]

about the Land of Israel. Indeed, from the end of the war until the Holocaust era, aliya to the Land of Israel from Chorzele never ceased, and the strongest desire that pulsated in the hearts of the youth was – to make aliya to the Land.

The factor that influenced the pioneering spirit of our townsfolk, that is, that led to the organization of a chapter of the Hechalutz Organization, was the riots of 5689 (1929) in the Land[1]. The riots left a deep impression on the town and aroused anger against the gangs of Arab murderers, and especially against the provocative stance of the Mandate government, headed at that time by the Jew, Herbert Samuel. We could not supress this matter, and we gathered in the Tarbut Hall for a protest meeting, with the participation of people from all the Zionist organizations of the town. I expressed the feelings of outrage that pulsated inside me at that time in the following words, which remain with me to this day as a manuscript.

“The human mouth is too weak. The thoughts are too obtuse, the heart is too soft to express even part of the feelings that each of us feels regarding the recent events in the Land of Israel. A gang of wild Arabs, driven by a fanatical dark clique, with the cold, sharp indifference of the Mandate authorities, fell upon the Jewish communities of the Land of Israel like wild beasts. However, the brave ones of Israel, our chalutzim, the most admired of the people of the world, the celebrated ones, those who, with their own sweat, made the soil that was vacant for 2,000 years waiting for the blessed hands fruitful once again, were now ripped away from their peaceful and blessed labor and took up the eternally despised sword. They also demonstrated their wonders. We say here that the forgotten blood of our martyrs in the Land of Israel, together with the solidarity of the entire Jewish people from all corners of the world, will arouse a strong force within us, a strong interest, so that the Land of Israel will certainly become the national home of the Jewish people.” The powerful, very appropriate reaction to these events in the Land was aliya. I recall that two of our friends who were in a hachsharah kibbutz came to Chorzele at that time to prepare to make aliya to the Land. They were Davidson and Lanenter, who had gone to a hachsharah kibbutz even before the official Hechalutz was founded in Chorzele. The influence of the songs that they brought with them, and that were sung in the Tarbut chapter along with all our friends, will never be forgotten from my heart. One of the songs was:

From Klesowa until Shacharia, it is hard for you

I am preparing for aliya, and we laugh at you

Carrying blocks, hacking rocks, oh, it is hard for you

Gnashing our teeth, and we laugh at you.

This song expresses the anger toward the confirmed haters of Zion in Poland, and especially against those

[Page 72]

who were part of the Jewish nationalist movement, so to speak, but were prepared to sacrifice themselves for the Yiddish Language. It was especially during the disturbances of 5689 / 1929 that these haters of Zion found the opportunity to prove that their dark prophecies about Zionism were correct. It is worthwhile to note that well known Yiddish writers in America, including Avraham Reisen, H. Leivick, and Moshe Nadir spoke out against that stance. (The famous, humorous proclamation of Moshe Nadir is known from that time: Specifically if Rome is Rome, Moscow is Moscow, then Jerusalem – is Jerusalem…)[2].

|

|

In addition to the two friends that I mention, the atmosphere of aliya and preparation for aliya prevailed in Chorzele at that time, and encompassed many of the members. Among them was Tova Eichelbaum. It was the custom in Chorzele that when a member was about to make aliya, people would write words of memory in their souvenir albums. One day, my sister Feiga, of blessed memory, surprised me when she brought the album of her friend Tova to ask me for advice as to what to write. I wrote the following words for her:

For health and happiness, be peaceful and joyous

For you are travelling to the land that belongs to us Jews.

The sad events should not impede your work and fortune,

Be cheerful, happy, do not worry, the future will be very good.

For in accomplishing your role in our place that we strive for

It is our greatest hope to be together with you there.

[Page 73]

These words express the general spirit that pervaded amongst the youth of Chorzele during the time of the disturbances of 5689 / 1929 in the Land. At that time, Avraham Bialopolski of blessed memory, from the Jewish National Fund headquarters in Poland, came to Chorzele. His speeches at the Tarbut Chapter and in the synagogue left a deep impression on all strata of the town. Through these speeches, he contributed greatly to the success of the founding of the Hechalutz Chapter in Chorzele.

The work in the Hechalutz Chapter in Chorzele covered many areas: first and foremost, the study of Hebrew, general and Jewish history, the history of the Zionist movement, and the history of the general and Land of Israel Workers movement. There were question and answer evenings for all the residents of the town once a week. In general, there was barely any Zionist event in which Hechalutz and Young Hechalutz (which was founded around the same time) did not participate, and were not involved with. It is interesting to mention the celebration of Nachum Sokolow's 70th birthday, organized in the town with the participation of all the Zionist factions. Among other things, I related at that celebration that when N. Sokolow visited Poland in 1923, a special booklet in his honor, called “Nachum Sokolow” was published. That booklet included the words of Yaakov Fichman, Shalom Asch, Nachman Meisel, and others, as well as the words of our dear fellow townsman, the famous writer Reb Fishel Lachower of blessed memory. In his “Agadat Sokolow” articles, F. L. tells how N. Sokolow was greeted at the border near our town and brought to the house with “the special porch.” It is interesting to note the juxtaposition of the situation, stating that Nachum Sokolow was hosted exactly in the same house in which we were now gathered approximately a decade later to celebrate his 70th birthday in the Tarbut headquarters of the town. In that article, the various legends circulating in our town regarding N. Sokolow are mentioned, and a comparison is made between the legends of Napoleon and the legends of Sokolow, proving the great esteem with which he was held in our town.

|

|

The primary objective of Hechalutz in all its activities was to send as many members as possible to hachsharah kibbutzim to educate them and prepare them for aliya to the Land. There was barely any evening during the week in which we did not gather as the group. In addition to our studies, we dealt with all realistic questions related to the land of Israel. It is worthwhile to mention the 20th of Tammuz, 1931, when the Zionist organization in Chorzele organized an assembly in memory of Herzl. The representatives of all the Zionist organizations of the city participated, including: Reb Avraham–Michael Adler of blessed memory, the head of Mizrachi and the head of the Jewish community of Chorzele.

[Page 74]

He was a man of many activities, in whom issues of the Land of Israel as well as local Jewish communal issues formed a synthesis. His dedication to any person was boundless.

Incidentally, I recall an event of 1920. during the Bolshevik occupation, when soldiers of the Red Arm camped in Chorzele, and it was cut off from the entire region. My father of blessed memory and I walked to Przasnysz, 32 kilometers from our town. As we entered Przasnysz, they arrested us, along with all those who wanted to enter that town that day. They brought us to the local prison. Incidentally, Avraham–Michael of blessed memory, the deputy of the Rabkom, was there that day. (When the Red Army conquered Chorzele, they chose a gentile and a Jew to direct all town matters. They were called Rabkom.) He did not rest until he freed us from prison.

Reb Mordechai–Mendel Friedman, of blessed memory, the sponsor of the Jewish National Fund in Chorzele for many years, also participated in that assembly. He was of fine stature, with a black beard, always combed and neat. His love of the Land of Israel knew no bounds. He would also say, “I am a Hassid of Otwock, and I heed the words of the Rebbe in all matters. However, regarding the Land of Israel, these are my affairs.”

My brother Shepsl of blessed memory also participated in that assembly in his capacity of chairman of the Zionist organization of Chorzele. He was a man of many talents, with clear and pleasant logic, who possessed initiative and clear grasp in all areas, and knew how to easily find a solution to the most complex of issues. It was said of him that the gentiles in the city council (magistrate), where he was the Jewish representative, were full of wonder over his practical suggestions, in which he found a solution to every problem.

Hershel Grynberg, the secretary of the Zionist Council of Chorzele, also participated in that assembly. He was a lad with a great deal of energy and a constant desire to act and do. He was full of life and dedication for matters relating to the Land of Israel.

I too was among those who participated in the assembly as a representative of Hechalutz. I spoke there and concluded my remarks with the following words:

“Fifty years ago, Herzl stated: Zion will be redeemed through labor. I derive from this that labor has caused a holy transformation. Labor in the kibbutzim in the Land of Israel has created a new, pure, fair life (according to the writing from Herzl's pen), which does not allow us to be satisfied only with what they create in the Land of Israel, but also with we build here in avant garde fashion in the pioneering kibbutzim, in the quarries, in the forests, fields, in the sawmills – in which we Chorzelers play no small role. (There were seven comrades from Chorzele on hachsharah at that time.) In the name of everyone I declare that we will not be satisfied if we do not accomplish the colossal work of the 20th century, in accordance with the mottoes of the representatives of the Labour Party in the Shaw Commission (Harry Snell)[3] – the creation of a Jewish national home on firm foundations in the Land of Israel.”

[Page 75]

Following the assembly, we organized an evening dedicated to T. Herzl in the Hechalutz chapter itself. I searched for material that would survey the connection between Herzl and pioneering. However, since I could not find any fitting material, I wrote the following poem myself and gave it over to the group of students to be read. The following is the poem:

|

How rare it is that we have such people as we have here

You have called, encouraged, aroused

And the call that has arrived

The people has straightened up and arisen,

And the best of the liberators |

[Page 76]

|

|

|

|

[Page 77]

|

|

In the Hechalutz chapter, we dealt with questions related to the land of Israel, hachsharah kibbutzim, and aliya, as well as with problems connected to the Hechalutz fund, and Workers of the Land of Israel Fund. We decided to go out to work in order to provide funds for the Hechalutz fund. The girls went out to bake matzos for Passover, and the boys went to chop wood.

We participated in all the activities of the Jewish National Fund, and contributed to general cultural activities. Many people certainly remember the general interest surrounding the cultural evenings that took place on Friday nights. Many would place their notes with questions into the chest during the week, and wait all week for the response. The debates that took place regarding every question on Friday nights were educational–cultural events of great value for the entire town.

There was a hachsharah kibbutz for Poalei Agudas Yisroel in Chorzele, the first and only one in Poland at that time. Before I made aliya to the Land, almost all the members of that kibbutz came to me to bid farewell, either because of my status in Hechalutz or because my father Shmuel, of blessed memory, was the chairman of Agudas Yisroel in Chorzele. From time to time, he also gave lessons in Talmud for the members of that kibbutz. In response to their blessings, I said that despite the differences of opinions between us, they would easily become absorbed in the fields of the Land of Israel. Then, Avraham–Michael of blessed memory, who was among those gathered around, said, “What an ideal I see here. The Hechalutz of Histadrut and the Chalutzim of Poalei Agudas Yisrael are sitting together…”[4]

[Page 78]

|

|

|

|

[Page 79]

Despite the differences of world outlook and Zionist ideology, all the residents of the town lived their lives together, as good Jews very dedicated to issues of the land of Israel and the mutual benefit organizations that existed in Chorzele. This was a variegated, vibrant life, full of the content of a Jewish town. Our hearts can find no comfort over their loss. It there is some sort of comfort, it is only from the fact that a large number of the brothers, sisters, children, and grandchildren of the martyrs of Chorzele merited in participating in the establishment of the State of Israel. Through this activity, the great aspirations of the people of the destroyed town, those dear people whom we never cease to think about until this day, were realized.

As I think about our town as it was during its life, and bring to memory its vibrant personalities and their activities, it is natural that, first and foremost, the sublime image of my revered father, Reb Shmuel Frankel, comes to mind, symbolizing the entire picture for me.

He was called “Shmuel the Rabbi” in town. Why was he called “the Rabbi”? My father was not a rabbi, nor a Rebbe, and did not use his scholarship as a means of earning a livelihood. He was a scholar and a Hassid. I still remember his gold watch with the gold change that he showed us as youngsters and told us that he received it as a prize for his lecture on Tractate Nedarim with the Ran commentary, which he gave by heart on the occasion of his Bar Mitzvah. From that time, throughout his entire life, he never deviated from his study. He would host celebratory feasts annually on the occasion of the completion of study of the entire Talmud. When his sight dimmed, and he could no longer study and review form the source, he would review the Talmud by heart, from his memory alone, as our sages of blessed memory did in the Yeshivas of the Land of Israel and Babylonia, before the oral words of Torah study committed to print.

My father was a Hassid. I will never forget the Hassidic stories that I heard from him, with the enthusiasm and devotion that could only be expressed by a true Hassid. The stories ranged from the early stories of the Baal Shem Tov[5] until the latter stories of Tzadikim and Rebbes – the Gerrer Rebbe who was his Rebbe, the Kocker Rebbe, the Ciecanów Rebbe, and many others. He could tell stories about them all with the same feelings of enthusiasm for truth.

He was a proud Jew, with faith and strength. Once, the Magid of Bialystock (Rappaport), who was famous throughout Poland in those days, came to our town. In Chorzele, it was forbidden to go out on the street after 10:00 pm. due to the proximity with the border. The Magid continued speaking, and the congregation stood around him listening open–mouthed to every word. The hours passed, and nobody sensed it. Suddenly, the police chief appeared along with policemen and began to scatter the gathering. Then my father arose from the congregation, approached the police chief (a tall, broad–shouldered man, with a strong manner of speaking, and who instilled fear in all hearts) and whispered something in his ear… After that, he turned to the crowd and called them to enter the synagogue again and to continue to listen to the words of the Magid.

[Page 80]

My father was a strong, wise scholar. Our house was always filled with people from all strata of the population. Some would come to seek his advice in various areas of life, and in matters of Torah and Jewish law.

This is how I saw my father, and this is how I still see him, hearing his quiet, strong voice, peering into his eyes that sparkled with enthusiasm and Hassidic devotion, hearing his unique melodies that he brought with him from the Rebbe, those melodies that he imparted to us and that penetrated our hearts…

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Chorzele, Poland

Chorzele, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Nov 2017 by JH