|

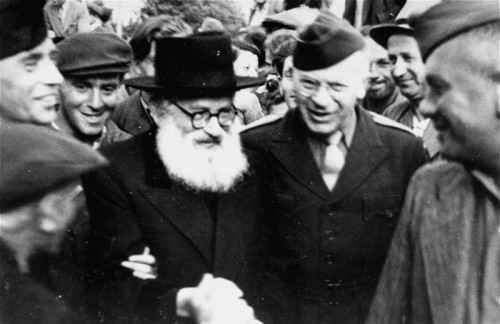

on his right entering the big Jewish D.P. camp Föhrenwald

|

|

Rabbi Herzog Enters Germany

Rabbi Herzog tried to get an entry permit to the British zone of occupied Germany where his son Chaim Herzog was stationed. He also wanted to visit the death camp of Bergen Belsen and bring comfort to the survivors. The British denied both requests. Chaim would have to travel to the American sector in Germany to see his father.

|

|

| Rabbi Herzog (center), and Rabbi Wohlgelernter in uniform) on his right entering the big Jewish D.P. camp Föhrenwald |

The Föhrenwald displaced persons camp was one of the largest Jewish D.P. camps in post–World War II in Europe and the last to close in 1957. It was located in the section now known as Waldram in Bavaria, Germany. The camp facilities were originally built in1939 by IG Farben as housing for its employees at the several munitions factories that it operated in the vicinity. During the war it was used to house slave laborers. In June 1945, the camp was taken over by the American army and converted to a D.P. camp. Thecamp. The initial population consisted of Jews, Yugoslavians, Hungarians and Baltics. On October 3, 1945, General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered that Föhrenwald camp to be converted to a Jewish D.P. camp since conditions at the Feldafing D.P. camp were overcrowded.

From 1946 to 1948, Föhrenwald grew to become the third largest D.P. camp in the American sector of Germany, after Feldafing and Landsberg. By January, 1946, its population had reached 5,600. Föhrenwald operated under the auspices of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). The camp's director was Henry Cohen. Assisting Cohen in the camp's administration and operation was a camp committee whose members were elected from among candidates representing a range of Zionist political parties.

On June 4, 1946, Rabbi Herzog entered the Föhrnwald D.P. camp to spend the Shavuot (Festival of Weeks) holiday there with the Jewish survivors. While in the camp the rabbi attended prayer services and delivered a speech in Yiddish. The rabbi, more in his official role as chief rabbi of Palestine, assured the survivors that the Jewish community of Palestine had not forgotten them, and promised that their liberation was not far off. “Soon you will be living like free men in your own land,” he told them. Rabbi Herzog spent an entire week touring the American zone's Jewish D.P. camps in Germany. Crowds gathered everywhere he went, drinking in his message of hope and redemption. William Leibner attended one of those meetings with his father, Jacob, an active member of the Mizrahi movement. The Leibners were then living in the Pocking D.P. camp, near Passau.

|

|

| Föhrenwald Jewish D.P. camp in the American zone in Germany |

With the end of the war, the Allied armies, which remained in the areas where their battles ended, were surprised to find millions of refugees stranded in Austria and Germany. Among them were the nearly 50,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors still left in the newly liberated labor and concentration camps. While the Allied army command, working with UNRRA, successfully repatriated millions of refugees back to their native lands, most of the Jewish Holocaust survivors, except for those deported by the Nazis from Western Europe, adamantly refused to return to their countries of origins. In addition, large numbers of non–Jewish Poles refused to return home, insisting on remaining in labor camps where they had been liberated. The result was an exorbitant demand for food, clothing and services that caught both UNRRA and the Allied armies by surprise.

Adding to this unexpected burden were the tens of thousands of Jewish refugees pouring across the Czech–German or Czech–Austrian border from Eastern Europe, mainly from Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine and the Baltic areas. UNRRA in Italy, Austria and Germany quickly converted former army bases, labor camps and concentration camps into displaced person (D.P.) refugee camps. The American army was complacent during this emigration as American troops, standing guard on the demarcation lines alongside Soviet troops, offered no resistance when Jewish refugees appeared on the German or Austrian side of the border. According to the author Tad Szulc, it appeared no orders to stop this onrush of refugees from entering Germany and Austria were issued to troops guarding the border.

The British refused to allow Jewish refugees to enter the existing D.P. camps in the British sector of occupied Germany and Austria. This policy was principally aimed at the Jewish refugees who appeared in large numbers. The British quickly learned that the British area was to be avoided since British policy was to escort the Jewish refugees out of their zone and directing them to the American zone. Jewish social service agencies were forbidden to enter the British–controlled zones in Germany and Austria, even to assist the Jewish Holocaust survivors in concentration camps like Bergen Belsen. Arriving in Munich, Rabbi Herzog met Jewish representatives of the various D.P. camps. As was his custom, Rabbi Herzog left these Jewish leaders with the message of hope and confidence and told them that a better future awaited them.

On June 4, 1946, Rabbi Herzog entered the Föhrnwald D.P. camp to spend the Shavuot (Festival of Weeks) holiday there with the Jewish survivors. While in the camp the rabbi attended prayer services and delivered a speech in Yiddish. The rabbi, more in his official role as chief rabbi of Palestine, assured the survivors that the Jewish community of Palestine had not forgotten them, and promised that their liberation was not far off. “Soon you will be living like free men in your own land,” he told them. Rabbi Herzog spent an entire week touring the American zone's Jewish D.P. camps in Germany. Crowds gathered everywhere he went, drinking in his message of hope and redemption. William Leibner attended one of those meetings with his father, Jacob, an active member of the Mizrahi movement. The Leibners were then living in the Pocking D.P. camp, near Passau.

|

|

| Pocking D.P. camp |

The pocking camp also known as Waldstadt was a military airfield 130 Kilometers east of Munich, Germany. During the Nazi regime a side camp of the Flossenberg concentration camp was set up in Pocking. Pocking also had a military airfield that was built between 1937 and 1939 by the Luftwaffe. Although it was an active airfield, it did not see much action during the war. Only during the fall of the Reich in early 1945, did it get active flying units. After World War II, it became the largest DP (“displaced persons") camp in Germany. In 1946, the camp housed 7,645 people, mostly Jews.

As the camp was situated very close to the Austrian border, about half of its inhabitants were smuggled in by the Brichah from Austria. The DPs were housed in a former Luftwaffe camp which comprised of wooden barracks with insufficient heating. The camp was known for its bad sanitation, lack of food and bad living conditions. Despite that, the DPs managed to organize a thriving community life. Pocking had several Talmud Torahs and Yeshivot and maintained a kosher kitchen. There were also two kibbutzim and a kindergarten for 200 children.

Over 300 of Pocking DPs attended one of the twenty–five courses organized by the camp's ORT school, one of the largest ORT schools in Germany. The school was based in an abandoned air force hangar. The subjects taught included nursing, corset making, radio technology, leather work, joinery, electrical engineering, dental technology, weaving, auto mechanics, and dressmaking. In addition to regular classes, the school ran a weaving course addressed especially to the Hasidic population of the camp. There was also a clothing factory employing about sixty people, each of whom was expected to make a suit a day from material supplied by the military. The completed garments were returned to the military for distribution to displaced persons camps. The school employed twenty–seven teachers, both Jewish and German. The director of ORT school in Poking was engineer Jakub Fridland.

Pocking DP camp was closed in February 1949.

Some facts about the Pocking camp

Official Address:

Waldstadt (Pine City)

Leader:

Chaim Goldstein, Moisze Garfinkel

Refugee

Population:

Mostly JewishDate of report 650 January, 1946 2,100 March, 1946 5,119 July, 1946 8,122 October,1946 7,453 July, 1947 5,756 October, 1947 4,312 October, 1948

Refugee camp Opened:

January, 1946

Refugee camp Closed:

1949

Sport– Soccer Clubs:

Hagibor Pocking, Hapoel Pocking

Cultural Institutions:

Kindergarten, elementary school, cinema house and sport clubs.

|

|

| The author of the book attended the Nachman Bialik elementary school in Pocking for a few months and in June was promoted to the next grade. But the family left the camp during the summer with a Brichah transport. |

|

|

| Rabbi Herzog greeted at Neu Freimann D.P. camp |

Jakob Leibner was in charge of the wood supply in Pocking that was used as fuel for cooking and heating. William Leibner recounted how his father bribed one of the UNRRA drivers to take a group of Mizrahi party members to the Neu Freimann D.P. camp near Munich to hear the rabbi speak.

The Neu Freimann D.P. camp in the Munich district was located in the American zone of occupied Germany. The camp was opened as a refugee camp in July, 1946. Initially it had a Jewish and a non–Jewish population consisting mostly of Poles. The two populations did not get along. Most of the non–Jewish population was relocated to another camp and Neu Freimann became a predominantly Jewish D.P. camp. The camp averaged about 2,570 Jews per year during its existence. The camp closed on June 15, 1949.

|

|

| Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of the Allied forces in Europe |

Leibner recalled that the vehicle left Pocking at dawn, traveling several hours until reaching the Neu Freimann camp. When Leibner arrived, the camp was in some turmoil as the residents excitedly awaited the rabbi's talk. Leibner was ushered to a large open area where the rabbi and his entourage were already seated at the podium. Leibner said that the rabbi started to speak in Hebrew but soon realized that with a few exceptions he had lost the audience. He then rapidly switched to Yiddish. He spoke a Heimishe (down–to– earth) Yiddish, and always used the word “unz,” meaning us, as though he were one of the refugees. The rabbi assured the gathering that their sufferings would soon end and “we” would soon abandon the cursed (German) soil where “our” people have suffered so much. Leibner recalled that the rabbi peppered his speech with biblical quotations to assure the gathering that God had not abandoned us. Herzog urged everyone to have hope and faith because “our Geula (redemption) was not far off.” The Leibners were impressed not only with the rabbi's neat appearance, but his ability to speak with such passion and so convincingly. Leibner recalled that when his father piled everyone back in the UNRRA truck, they were all in very high spirits, convinced their worst days were over.

On June 7, 1946 Rabbi Herzog journeyed to Frankfurt am Main where he met with Major General Isaac D. White, Commanding General of the U.S. Constabulary for the European Command, the “super–police” force that controlled the population of the American zone in Germany. General White was no desk–bound bureaucrat. He had been a war hero leading troops in the successful Battle of the Bulge. The two men discussed the Polish Jewish situation. Rabbi Herzog stressed the need to keep the American zone open to all Polish Jewish refugees fleeing for safety. The rabbi had a list of other requests. He asked that the general recognize the legitimacy of the elected Jewish leaders in the camps, that the camp provide kosher food to the refugees and to help to develop religious and social services.

|

|

| General I.D.White |

The general told the rabbi that if it was up to him, he would close the border to all refugees.[1] But, the general pointed out, these were not his decisions but those made in Washington. He told Rabbi Herzog he would forward the requests to the proper authorities.

The general's antipathy was well founded. Following the war, the American Army in Europe found itself responsible for a seemingly ever increasing number of refugees pouring across the borders, almost all of whom wanted to find safety and only the American zone was available; the British had closed the borders to its zone and nobody wanted to go to the Soviet zone. For men like White, the situation was a bureaucratic and logistical nightmare. An ever–increasing demand for blankets, beds, food, sanitary facilities, medical supplies and manpower was stretching resources to the limit. And all of these things cost money.

The refugees had a special hatred for the Germans. Vigilante groups sometimes snuck out of the camp and carried out raids against the surrounding population. Germans coming into the camp to provide services were attacked. American military police had to patrol the camps since a German policeman in uniform might well have started a riot. General White had enough on his hands without having to deal with an endless supply of refugees.

The UNRRA organization, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Jewish Agency of Palestine, the American Vaad Hatztala, the ORT organization and other social and professional Jewish organizations were all involved in helping the camps to exist. The population had serious problems, nobody wanted them and the place where most of them wanted to go, Palestine, was closed to them. Still, the American Army was responsible for these people.

Early on after the war, American troops under the command of General George Patton had deployed along the Czech–German border and forcibly stopped the Jewish refugees from crossing, turning them back to Czechoslovakia, hoping that they would go back to Poland.

|

|

| New York Post Oct 2, 1945 |

When this news reached President Truman, he was furious. President Truman had already signed the Harrison Report in 1945 that called for the decent treatment of Jewish survivors in the D.P. camps in Germany and Austria. Truman was deeply embarrassed by the American army's actions. He placed a call to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, to settle the matter.

The New York newspapers were leaked the stories and headlines blared about the mistreatment of Jewish Shoah survivors by American soldiers

|

New York Post Oct 2, 1945

Patton Turned Back 600 Jews Fleeing Terror in Poland

by Pat FrankPilsen, Czechoslovakia, Oct. 2– At the order of Gen. Patton, 600 Polish Jews who hoped they had reached asylum in the U.S. zone from an anti–Semitic wave of terror sweeping their homeland, were forcibly returned to that country, this correspondent established today.

(A Munich cable on Sept 21 reported that 650 Jews had escaped from Poland had arrived at the Pilsen reception D.P camp. American officials interrogated hem. The refugees claimed that they were German refugees returning to Germany. The officials soon discovered that they were not German refugees but Jewish refugees heading to the American zone. The news was relayed to the military headquarters of the third army headed by General Patton. He ordered that they should be returned to Poland. These Polish Jewish refugees escaped Poland and the anti–Semitic terror in Poland. The refugees described in great detail the anti–Jewish attacks and pogroms directed at the Jewish Shoah survivors.

At least 3,000 Polish Jews have reached the U.S. zone. What happened to the 600 who believed they had found refuge at Camp Karlov in Pilsen, Czecholovakia, the United Nations' displaced persons center here, is another story. The tale is nearly as shocking as what happened to them when they were returned from Nazi concentration camps to their homes in Poland.

Gen. Patton's 22d Corps, stationed in the U.S. zone in Czechoslovakia, violated the oft–repeated policy of Gen. Eisenhower– that United Nations national and persecuted peoples who do not desire to return to their homelands, or whose lives would be endangered in so doing, shall not be returned by force. Furthermore, it is to be noted that Jews alone were singled out for forcible removal.

The Jews began crowding into Camp Karlov around the middle of August. Three trains, each carrying 175, arrived at Pilsen. Others afoot sought refuge here after trudging through the Russian zone in Czechoslovakia. The top authorities of the 22d Corps requested permission to ship these Jews to Germany where special camps for Jews were being erected. But Gen. Patton's headquarters ordered them shipped back to Poland.

It is somewhat complicated to trace the exact responsibility for this order since the DP officers then in charge of Camp Karlov have been redeployed. However the officers now in charge say that Gen. Patton's 3rd Army headquarters ordered the Jews returned because “there wasn't room for any more Jews in Germany, where the camps are already over crowded” and “the trains that brought those Jews entered our zone without proper authority.”

To this correspondent, enlisted men at Camp Karlov described the pitiful scenes that ensued when the 600 Jews were loaded aboard trucks, on Aug, 24, and taken to the Pilsen railroad station. The women among them fought bitterly, screaming and kicking.

“We Had To Use Force”

The military detachment found itself unable to cope with the situation and asked for assistance. The 8th Armored Division sent troops with rifles, machine–guns and armored vehicles. Pvt. Edward Heilbrun, of Chicago, who is Jewish and who helped to load the hapless, protesting Jews aboard the trucks, told me: “My job was sickening. Men threw themselves on their knees in front of me, tore open their shirts, and screamed, ‘Kill me now!’ They would say, ‘You might just as well kill me now. I am dead anyway if I go back to Poland.’ They kept jumping off the trucks. And we had to use force.”

There was more trouble at the railroad station where the troops were forced to jam the 600 Jews aboard a train.

Destination a Mystery

After the train started, the trouble continued, according to witnesses. Men threw themselves from the moving train. Troops fired in the air attempting to frighten them into remaining on the train. Where the train was routed, after leaving the American zone, is still a mystery. One woman who was scheduled to return to Poland did not have to go. She is Luba Zindel of Cracow, and she was having a baby at the hospital here when the train departed. I talked to her at Camp Karlov.

This is her story: With her husband and an earlier child, she had spent three years in the Nazi concentration camp at Lublin. After the Russians captured that city, the family was released. They returned to their home in Krakow on June 20.

On the first Saturday in August, while the family was attending synagogue services, their synagogue was attacked and stormed by uniformed AK or Armija Krajowa troopers.

“They were shouting,” she told me, “that we had committed ritual murders. They began firing at us and beating us up. My husband was sitting beside me. He fell down on his face full of bullets.”

Following the pogrom, the widow packed a few things and contacted the Polish Brichah that directed her to an assembly point. The transport of Jews then headed to Czechoslovakia where they boarded a train that took them to Pilsen. Her transport was one of the three trains of Jews that arrived at Pilsen. Another woman who survived the Shoah, Saba Szkop of Lodz, Poland, told me there had been pogroms in Lodz, Warsaw and Radom, as well as Cracow. She said the ancient anti–Semitism in Poland, encouraged and kept alive by the Nazis, was being inflamed and exploited by the nationalist elements.

After the Pilsen incident, Jewish refugees returned in larger and larger numbers to the American zone. Following that incident, no further attempts were made to forcibly halt Jewish refugees from crossing the border. By the end of 1947, an estimated 250,000 Jewish refugees had streamed into the D.P. camps in Germany, Austria, Italy, France and Belgium[2]. Despite the fact that the Brichah was smuggling Jews into Palestine, and other countries took in some refuges. The D.P. camps were bursting at the seams for the flow of Jewish refugees kept coming and the UNRRA organization had to provide facilities and food.

UNRRA was founded in 1943, and while dominated by the United States, was comprised of 44 member nations. In 1945, UNRRA was incorporated into the United Nations once that organization began. UNRRA was closed down in 1947. While in operation, the purpose of UNRRA was to “plan, co–ordinate, administer or arrange for the administration of measures for the relief of victims of war in any area under the control of the United Nations through the provision of food, fuel, clothing, shelter and other basic necessities, medical and other essential services.”

UNRRA, with headquarters in New York, employed nearly 12,000 people. The United States contributed nearly $3 billion to the fund, with Britain adding $625 million, and Canada $139 million. The rest of the $3.7 billion was made up of funds from contributing nations. Besides distributing food, clothing, medical supplies and farm implements, UNRRA played a major role in helping displaced persons return to their home countries in 1945–1946. The original aim of UNRRA was to provide aid only to nationals who were part of the Allies. But in response to the pleas of Jewish organizations concerned with the fate of German Jewish survivors, “other persons who have been obliged to leave their country or place of origin or former residence or who have been deported there from by action of the enemy because of race, religion or activities in favor of the United Nations” were included.

In Germany, UNRRA was primarily servicing displaced persons, especially the millions of non–Germans brought by the Nazis to Germany and Austria. UNRRA's European Regional Office was in London, but was subject to the authority of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe. The first director of UNRRA was Herbert Lehman, a former governor of New York State, who served from January, 1944 to March, 1946. He was succeeded by Fiorello La Guardia, a former mayor of New York, who served from April to December, 1946. La Guardia's sister Gemma La Guardia Gluck, and other relatives, had been imprisoned in German concentration camps.

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Children Train

Children Train

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 03 Apr 2018 by JH