|

|

|

[Page 555]

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

No. 38/12

15-XII-1946

Minutes of the Voivodisher [provincial] Jewish History This relates: - Gitl Libhober, born 11/18, 1897. Possesses middle [school] education. Trade – a dressmaker. Before the war – lived in Chelm at Lwowske Street, no. 4, and she now also lives in Chelm at Pasztowe 39. Recorded by Irene Szajewicz. |

There were 18,000 Jews in the city in 1939 when the Germans entered Chelm. I had a husband and a 15-year old daughter and a son of 17. The Germans immediately began to bully the Jews, grabbed them for work. Mainly they employed the Jews for cleaning the toilets with their bare hands, and after the work they ordered the Jews to beat one another. S.S. members Ralfink, a tall blond, 30-year old man, and Dr. Selch, also of the same age, particularly tortured the Jews. A month after the arrival of the Germans, a Judenrat [Jewish council] was created according to their [German] procedures with the merchant, Frankel, at the head. Members of the Judenrat were: Biderman, Dreszer, Tenenboim, Frajberger.

One day the Judenrat ordered all of the Jewish men from 15 to 60 to assemble at Luczkowski Square where he [Frankel] would speak to them. The Jews gathered. The Wermacht [German armed forces] surrounded them and, pointing their guns at them, ordered that they surrender their money and expensive things. First they took everything from the assembled Jews and then they began to beat them murderously. The worst scoundrel and murderer was the above mentioned Ralfink who directed this aktsia [Nazi military operation usually associated with rounding up and deporting Jews]. The women and children also came from distant streets wanting to hear what the leader of the Judenrat would say. In a moment, Ralfink went over to a Jew named Motl Bakalczyk and asked him to dance. When the women and children seeing it all began to cry, the Germans began to shoot in the air and the assembled men were driven in the direction of Hrubieszow. I was also present for all of this because I did not let my husband and son go out of our house and, therefore, I wanted to know what would happen here. If there would be any bad consequences. The desperate women went to the Judenrat and begged to be told what had happened to their husbands.

Then the women left on the Hrubieszower Road and saw that the road was sown with dead bodies. There were traces of blood and pieces of clothing everywhere. One thousand Jews were killed then on the road to Hrubieszow.

[Page 556]

One of those who successfully escaped told me that the Germans had ordered the Jews to dig holes and then told them to lie in them and other Jews were forced to bury them alive. Eight hundred Jews reached Hrubieszow; from there they forced them to Keldz on the Bug River and told them to go to the other side of the river. Three hundred Jews were successful in reaching the shore of the other side of the river and approximately 100 Jews returned to Chelm in very bad condition. The Germans wanted to arrange such a spectacle with the women, but the Judenrat did not want to summon the women and the Germans gave up on this. Many Jews attempted to escape to the Russian side. The Jews were treated horribly (by the Germans). We received food cards; everyone was forced to work. When it was possible, they ransomed themselves with money. This lasted until 1941. The Judenrat had to fulfill all of the German demands, which was not so easy and, therefore, the Judenrat had to extort everything from the Jews in order to placate the Germans, but the murder of Jews had not yet started.[1]

At the beginning of 1940 we were forced to put white patches with the Mogen Dovid [Star or Shield of David] on our right shoulder… Still in 1940, I reported as a foreman and became a dressmaker for the S.D. (Sicherheits dienst [security service]).

Once, a member of the S.S., Schteinert, a terrible murderer, and his wife approached me and ordered a dress from me. He demanded that the dress be finished the next morning at 11 o'clock. I answered him that it would be finished at 3 o'clock in the afternoon. After long words, they agreed. The dress was sewn by the morning and I, myself, carried it away. Schteinert met me and asked at what time was I supposed to bring the dress. I answered that I clarified this last night that it could be finished at 3 o'clock and it was now just 2:30. Without saying one word, Schteinert began to hit me, so that I fainted. Then he told the Jews who worked for him that I should be carried to the cellar. When I came to, Schteinert's wife was standing near me and asked how I was doing and said that she was delighted with the sewn dress. Agitated, I said: And why did your husband beat me so if this was true? She began to scream that nothing had happened to me and he had beaten me very little and now I should sew three more dresses. When I categorically refused, she threatened that if I did not sew the dresses, she would immediately bring the dogs, which would bite me, and she said that her husband had especially not killed me because

[Page 557]

my work pleased her and as long as she had me sew dresses I would live. Knowing that I had no other option, I agreed to take on the additional work. My husband was the pharmacist for TOZ [Society for the Protection of Health]; my son also worked in the pharmacy. My daughter sewed with me.

In May 1941, a transport of Jews arrived in Chelm from Slovakia. They had a great deal of baggage with them. The things were laid out in the synagogue and then the Germans removed it all. Each Jewish family took several people from the transport. They were at the mercy of the Judenrat because the Germans had stolen everything from them. Jews were not supposed to be taken care of by Aryan doctors or to make use of the pharmacy. Jews organized medical help in their own area. There were also Jewish businesses because the Aryan stores were not supposed to be entered. A Jewish militia was organized.

One day a member of the Gestapo came to me and demanded that I sew a dress for his wife during the course of three days. I did not have the time because I had the work for the shishkes [big shots] from the Gestapo and I could not be even a minute late with their work. The Judenrat gave him another dressmaker. Three days later I was called to the Gestapo by a Jewish militia man. There I found the member of the Gestapo with his wife in a new dress and also the dressmaker who had sewn it. Schlezinger, the member of the S.S., asked me if the dress had been sewn well. Although the dress had been sewn with many defects, I do not want to say this and I gave an evasive answer. Then Schlezinger gave his whip to the dressmaker, ordering her to give me 15 blows.

In Autumn 1941, the Jews had to transfer to a separate quarter. These were the streets: Szkolne, Unjejacka, Pocztowa, Siedlecka and Katowska. Only the Jews who worked in the city could go outside the limit of these streets. Jewish militia men and armed Poles stood guard over the quarter. I lived on the corner of Kopernika and Szkolne Streets. There were two entrances, one for we Jews and a separate one for our “clients” from the Aryan side. Other tradesmen lived in the same place.

The plight of the Jews became more difficult with each day. Spring 1942, the Jews were deported to Wlodawa from the small shtetlekh around Chelm: Dubienka, Wojsławice, Siedliszcze, Sawin and from others. All passed through Chelm. I saw how the Germans bullied them. I saw their terrible need and misfortune. In Chelm, it was said that only the working Jews could remain there.

The first aktsia was in May, 1942. The Jewish militia and the granatowa [granatowa policja – Blue Police, popular name of the police organized by the General Government] went with the S.S. members through the houses and took the old, mainly

[Page 558]

the Slovak Jews. Toymer of the S.D. led the aktsia. The Jews were deported on the train to Wlodawa, but some of them were off-loaded in Sobibor where there was a death camp, but we did not know that then. Letters arrived from Wlodawa to which the deported were sent and we were sure that they would meet the same fate as those from the small shtetlekh. That is, that they would be rounded up and deported, that the majority would be annihilated. Staying alive was more difficult for those who did not have any work to do.

Two months later in July, after the first aktsia, I remember that it was a Friday, the second aktsia broke out. The Germans and the granatowa police exclusively carried it out. The Jews were gathered from their workplaces (from the city hall, from the water facility and from others); they were bound together in groups of 5-6 people and were driven in the direction of Wlodawa. Several escaped in route and the remaining were taken to Sobibor. No one reached Wlodawa. We then first learned that they had perished and we knew that things were bad.

On the 14th of August a Jewish militia member came to me and said that all Jews must go into the ghetto and I, also, could not live in the same house in which I had lived until then. I ran to the S.D., to my “client,” and I asked what had happened. Then I was told that I should hide everyone of mine because those who did not work for the Germans would be deported to Wlodawa. I hid my husband and son with a Ukrainian acquaintance in a bunker. I remained in my apartment with my daughter and with the women workers. The Jewish militia violently removed us from the house and took us to the square on Siedlecka Street. There were many Jews there. My daughter escaped from the square and ran to the S.D. She explained that I had been taken and that all of the clients' goods remained in the house. Meanwhile, terrible things happened on the square. A Jew, who had held a piece of bread in his hand, was brought. The bread was torn from him and the Jew said that “the world is no longer for him.” Then, when the German asked him what his last request was, he answered that he wanted to eat the piece of bread. The Germans gave him the bread and when he placed the bread in his mouth, they shot him. One of the Germans standing on a balcony showed a Jewish child to those gathered beneath and asked if the child pleased them. Then he smashed the small head of the child, banging it into the wall and, tearing the head in half, he threw it on the square. It is difficult to write about the terrible, horrible events that took place then on the square. Several tradesmen, it seems the more praise-worthy, were taken from the square. The S.D., who had been informed by my daughter, came to take me from the square. All

[Page 559]

the Jews who had been brought together, about 3,000, were deported from the square to Sobibor, where there was a death camp. I remained living in my apartment. The Jews who were left after the aktsia remained in the Jewish quarter, went to work and some time passed that seemed quieter to us.

The first day of November 1942, repression began again. It became clear that something would again happen.

Two day later, before the aktsia broke out, I brought work for the S.D., finding S.D. Horn completely drunk. He then told me that only the Jews who were needed tradesmen would remain in Chelm and the rest would be deported. I asked the date; he answered that he did not know exactly.

On the 6th of November, Taymer[2] and the S.S. member, Roshendorf, (the worst hangmen over the Chelm Jews) came to the apartments of tradesmen who needed to remain and marked their doors with chalk as signs that they were to remain with the workers and their families. At the same time, they ordered that the doors be bolted and that no one be allowed in. I did what I was ordered to do.

In half an hour the S.S. came and took me and everyone, except my husband who had hidden the last moment. My protests and all of my talk about the chalk mark on my door did not help me. I was brought

[Page 560]

to the square that was on Kopernika Street. On the way the daughter of S.S. Horn saw me. I called to her; she should tell her father that I had been taken. A member of the S.S., hearing my talk, called out to her: “Do not say anything to your father. All the Jews must die,” and at this, Horn's daughter answered: “All of the Jews can die, but not Mrs. Libhober. She must sew my new dresses.” And she immediately ran away. There were several thousand Jews at the square near the Russian church. The Germans beat them with whips, tortured and bloodied them. The walls of the church were red with blood. Horn came with several S.D. and said to me that I should go with all of mine to the other side where a group of the chosen tradesmen stood. The Jews at the square were ordered to line up in rows of three and they were taken away to Piarske Street. Six thousand Jews were taken then. Many bodies of murdered children and several adults were laid out on the square. The population of Chelm stood on the other side of the church calling out: Good for them; long live Hitler! Wagons immediately came and the bodies were taken. They were thrown in the wagons like sand. The S.S. surrounded our groups of tradesmen and told us to go. On the way we met the other Jews. They were taken in wagons and we to the camp on Kalajover Street. They were taken in the wagons in front of our eyes.

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 559]

by Ester Bas-Meltser

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

…so I am in my birthplace Chelm. This is, alas, a true cemetery. Every stone – a headstone, each house – a witness to the murdered martyrs.

If we could understand the language of the wind that shakes the leaves on the trees in the emptied streets, we would certainly learn about many tragic scenes that were played out when the hangmen drove our parents, sisters and brothers to death.

Everything chokes with the heavy, oppressive picture of the nightmarish day. Our Polish neighbors greet us with an open hate in their eyes. We see, literally, a resentful astonishment when they look at us; from where did we come and how did we survive?

“Yet, a small number of you were saved,” a Polish acquaintance said to me with a tone of suspicion.

Day in, day out, I roam around the emptied

[Page 560]

Jewish streets. Only the strange, unfamiliar eyes of Polish children, who surely are wearing the clothing of those who perished, now look out of the windows from which the faces of Jewish children with dark, sad eyes would look out. I stand on Kopernika; the sun starts to go down. The redness reminds me of the flames of the destroyed Jewish houses.

It looks to me as if the blood of the tortured runs from its rays… I instinctively close my eyes and I think that I hear their voices. It begins to get dark; the moon appears in the sky. Its bleached brightness also frightens me, remembering the bleached out dear faces, the frozen eyes of my husband, Kuba, who fell asleep forever along with the Chelemer Jewish community.

Original Footnote

[Page 561]

by Yoel Ponsczak

Translated by Pamela Russ

An excerpt of a diary – from the archives of the Historical Committee in Warsaw

Number 104/VII

At the end of July 1942, a luxury car with five murderers entered the building of the Judenrat. They approached the chairman and demanded that by 2 pm all the Jews should be assembled in one place, and each person could take 15 kilograms with him. All left to the Ukraine. I quickly left the Judenrat, went home and delivered the “good” news. There was tremendous panic. People began to hide. I and my wife and child went into hiding as well. Our hiding place was one of the best ones in Chelm. It was a room in a German school, by a certain Professor Zeiger. It cost plenty, but it was worthwhile because we were safe there. I, having had a good work card with a green ribbon, could go freely in the streets. Within about one hour, you could not see even one Jew in the streets. At 12 noon, our streets were enclosed. They already did not allow me to leave these streets and I could not come back to my family. The Judenrat signaled to me that I should go somewhere else. But I had nowhere to go. I went into a shoemaker's home, he was one of the “aristocrats.” He worked for the murderers, and we sat there in great fear.

Through the window, we saw how the murderers were chasing all the Jews to one place. At 4 pm, there were already about 2,000 Jews assembled in that place. Frequent shooting could be heard. The city labor officer, along with Inspector Heldhas, were strongly involved in this Aktzia, and a large number of people were released. Three hundred people were taken to Sobibor, mainly the elderly, and 70 men were shot in the city.

These tragic summer days dragged slowly under the heavy load of work. Fall arrived, then cold. Many people were barefoot, naked, and hungry, and that's how we had to work in the muddy swamps. We were resigned to our fate. We felt that the ground was burning under us.

October 26, 1942, there was great pandemonium. All the workers of the factories were detained, and that was the clearest indication that the Aktzia would take place at night. You could not leave the area because of the late hour (Jews could only go out until 7 pm), so my family and I could not hide in our regular place in the above-mentioned school. We waited for the murderers all night, but the night was calm. As soon as it became light, we went to the school. The professor greeted us quite nicely, even though we disturbed his sleep. Within half an hour, there were already about 15 Jewish families in the school. The professor made a small business out of this, and with each Aktzia he raised his price.

[Page 562]

The morning passed calmly. Not one Jew was seen in the streets. On the odd moment, you would see a Jew running in a state of nervousness.

I went to the chairman to find out was going on. He was very agitated and did not hear what I was saying to him. But I did not let up and his reply was a tragic one: “It's bad.” It was already 11 o'clock. I went home to be able to take something for the family. At that very moment, the SS men were guarding those few streets and I could not continue onwards. This time, one of my neighbors created a good hiding place, so I went to hide there and he gladly took me in. It was now 12 o'clock and the murderers searched through all the streets. You could hear the incessant shooting. I was very nervous that I was not with my family.

It was evening, no shooting was heard, patrol cars were heard going through the streets. The region was small and there were more than 20 people there, and it was very wet. Finally, it was day. The murderers stormed through the Jewish streets. The entire time, you heard shots and explosions of grenades. The Aktzia lasted all day. In the evening, there was pounding at the door. We thought it was the patrols, but apparently it was Mr. Mandel from the Judenrat. He gave us gruesome news about the two days of the Aktzia. Eight hundred people died as sacrifices in that place and 3,000 people were evacuated on foot to Wlodowa. The entire time, I was thinking about my family hiding in the school. My daughter came in the evening, and with tears in her eyes she told me that her mother and Dovid'el were taken away. I heard this news as if a hammer had pounded on my head, but I calmed down and decided to save my wife and son at any cost. After leaving a payment, I settled my daughter in the home of a Christian, and I left for the Judenrat. All the members were in the Judenrat. I told them about my tragedy and asked for help, but sadly, they could not help me. They told me that my wife had been evacuated with the entire group of Jews and taken to Wlodowa, and she was together with the child.

The Aktzia was over, but I did not see anyone in the streets, other than the murderers who were wandering around. I decided to go to Wlodowa in order that, maybe, I would be able to save my wife and child. Six kilometers outside of Chelm, in the village of Horodyszcze, the peasants told me that some Jewish women were there who ran away during the night when the peasants were asleep. They told me that among these women

[Page 563]

was a tall brunette holding the hand of a young child. I was certain that this was my wife and my son Dovid'el. Like a wild man, I ran from house to house. The village was big. Finally, I found two Jewish women and a child, of which one was actually my wife and child Dovid'el.

The following morning, my daughter Pelye, whom I had left at the home of a Christian, kissed and hugged and cried with her mother and her darling Dovid'el.

Sadly, this joy did not last long. The murderers did not rest. They were already discussing the next Aktzia. I went to my Professor Zeiger, discussed the price with him, which as usual he raised again, this time more than others, and then we agreed. The week passed in terror. There was a panic, but things calmed down.

November 5, during the day, I was informed that there would be an Aktzia that night. In the evening, I and my family, along with sisters and brothers-in-law and their children, and there were also two Czechoslovakian Jews with us as well, and a certain Shmuel Schwartz and his wife, and we all went to the school. As was done previously, we were given a room, and there were Jews also in the other rooms. It seemed that Zeiger's school was popular in town. All the Jews were my good friends. All night, we went from one room to another, visiting as guest. As day broke, the murderers began to become wild. In the streets and on the smaller roads there was a real slaughter. The shots of the machine guns and the throwing of grenades did not stop. This did not stop all day. Only in the evening

[Page 564]

did it quiet down. In the late night hours, Zeiger visited us, but he became wild. We could not even speak to him. He kept screaming about how bad it was, and then he left.

His cold visit was suspicious for us, but what choice did we have. We held a short discussion with all those present and we decided to leave the school and to hide in the attic. We were now over 100 people. It was daylight. There were also a few Orthodox Jews among us. It was Shabbath. We blessed the new month of Kislev, and in town, it was once again the same as the day before. The shooting and the bombs from the grenades did not stop. Everyone was tense. The children cried, but thankfully, they could not hear this on the street.

At 10 am, the Germans found us in the attic. They took down 55 men. As sheep to the slaughter they took us to a designated place in the center of town. There they beat us mercilessly and then separated the men from the women. Then they chased us in the direction of the train station. We thought that they were taking us to the wagons to go to Sobibor. As we were going, I was holding the hand of my brother-in-law Avrohom Yakov, and we decided to escape. We ran towards a yard, and a friend ran after us. No one shot after us, I think because they did not notice us. Fate wanted that I should not struggle for 22 months, wandering without rest.

[Page 563]

by Manis Zitrin

Recorded by: E. Winik

Translated by Pamela Russ

On the eighth day of the war, the Germans bombed Chelm ferociously. There were many wounded on that day. From the first day on, when the Russian army entered Chelm, a military comprised primarily of Jews, was created immediately. The Poles did not join. In the villages, the militia were the Ukrainians. After eight days, the Russians left the town voluntarily. There was chaos. The Jews were terrified to go into the streets. The Polish good-for-nothings began their looting and even broke down doors of the shops. The local military of the magistrate themselves were looting as well, set fires, and even killed a few Jews.

The Poles began to spread a rumor that they were killing Polish officers and Polish police in the cellars of the prisons. The rumor was spread everywhere.

A great number of civilian Germans came from the villages, and they immediately became militia men. As the German military authorities took over the city, they

[Page 564]

they designated Mr. Kamentz, an owner of a mill and a steel foundry, as mayor.

Very quickly, the Germans snatched up Jews for work, collected all kinds of taxes, and they sold the materials from the Jewish stores for pennies to civilian Germans who ran away from the villages.

In about six weeks, the Gestapo already arrived. The first Judenrat, which was established by the Polish magistrate, was headed by Mr. Meyer Frankel, the son-in-law of Mr. Lederman and a brother-in-law of Itche Meyer Lederman. In essence, the Judenrat was good for the Jews, because they organized Jewish life somewhat. The Germans beat the Jewish Judenrat members for any small thing.

Later, some Ratnikes [name for those in the Judenrat] began to use their situation more for themselves – for their own families and for their material needs, at the cost of others.

In November 1939, the Gestapo demanded its first taxes from the Judenrat, in the sum of 100,000

[Page 565]

zlotys. The Judenrat members went to each house and collected the huge sum, and we paid the tax. A few weeks later, the Gestapo demanded that a few things be put together, primarily winter clothes and electrical items. Once again, we collected as much as possible and delivered everything to the German thugs.

At the end of November 1939, the Gestapo offensively once again demanded another tax, now 1/4 of a million zlotys, which the Jews could in no way produce.

Then came the demand that the Jews, primarily the men, must present themselves … “to work” early in the morning, on Friday, December 1, 1939, on the Rynek place [market square]. The Judenrat went into all the Jewish streets and told the men to present themselves for work, they themselves not even knowing to what type of work. About 2,000 Jews, the aristocrats of the city, gathered at the market square at the designated time. Not one of the Jews had any idea what was prepared for them.

At a set time, the Gestapo commandant arrived, and asked who was a skilled worker. He selected a group of ten men from the crowd. In the blink of an eye, the entire worried mass was surrounded by German Stormtroopers on motorcycles, and all 2,000 Jews were chased into the Hrubieszow forest. For three days, the tragic brothers were chased, beaten, and murdered, and all those others were shot. The road was quickly sown with the dead.

Interesting, that for a short time the Russian border was open, but no one wanted to escape. The Germans spread rumors, false ones, that they were leaving Chelm … This created great confusion in everyone's minds…

On the German holiday, November 9, 1939, the new German mayor, Mr. Haga, who was brought specially from somewhere else to Chelm, delivered a speech, where he publicly announced that he would make the city Judenrein [cleansed of Jews].

After the “march,” the city was as if dead. The Judenrat, whom the Germans considered as hostages, began to “be a little bloated' about themselves, and it began to be a privilege, a merit, to belong to the Judenrat. Anshel Biderman, Bash, and others did not reveal what they knew about the German acts. Frankel was the head of the Judenrat that began to protect their relatives and their own people.

In Chelm, there was no enclosed ghetto, but it was divided into two areas: In the first area there was Poctowa [post-office] street, Sziedlice, Katowska Street, until Motye Levin's house. The second area: Szkolna, around the synagogue, Kwisza, part of Seminarska Street, and Kopernika Street.

The Judenrat organized a merchandise warehouse for the needs of the Gestapo. They would buy the materials in Warsaw. As escorts for the Gestapo, two Jews

[Page 566]

from the Judenrat went to Warsaw to make these purchases. The Jews – in the Jewish area – brought materials with the help of the Christians, sold the materials, and even made some money. Some even brought materials from Russia (before the Russo-German War). There was a lot of smuggling, and the Germans closed their eyes to this. Paper money increased for everyone. There were some Jews who earned a lot of money and lived very comfortably.

The Judenrat created its own post system, offices, and so on. The director held himself to be “great,” a complete “manager,” a “Kaiser,” and the Jews had to remove their hats for him.

The Germans set up Pinkhas Szwartzblat from Libewna as the Jewish commandant. Previously, he was an agent for the Poles.

* * *

The issue of worker's outposts was a real problem. When the Germans had to clean out a house, or sweep out the garbage of a house, the Gestapo immediately called the Judenrat, that they must provide so many and so many workers, presenting the numbers as they demanded, for example: once - ten men; another time 40 men and women, another time even 100 people for work. The Judenrat had to assemble the required numbers of unskilled laborers and skilled workers for the Gestapo. The poor people labored hard and bitterly.

When the Russo-German war broke out, the situation for the Jews worsened daily. In March 1942, there was already a terrible slaughter of Jews in Lublin. Many Czechoslovakian Jews were brought to Chelm and they shared the same fate as the Jews of Chelm.

On Passover 1942, the chairman of the Judenrat gave a speech to the Jews in the yard of the Old Age Home, saying that whoever would not work would certainly die. Every morning the Jewish police chased the Jews to work.

The Germans created a new street that stretched from the Seminary Street to the train station. With their blood and sweat, the Jews paved this new street, where a new prison was also built for prisoners and for Jews.

The Germans twice set fire to the large, old synagogue, that was already 700 years old. The German vandals forced the Jews to remove the stones from the synagogue and clean the place up, make the ground smooth, so that no one would be able to tell that once a synagogue had stood in that place.

The staff officers of the Gestapo needed people, skilled laborers who would work for them, make suits for them, coats, shoes, boots, and so on. And not for the officers only, but also for their loved ones and mistresses. Therefore, they chose people from every vocation, arrested them in the new prison not far from the train station, organized special factories in the prison, and the craftsmen had to work continuously – understandably, unpaid, but only for enough food to sustain

[Page 567]

their lives – and do everything that the Gestapo ordered.

These are the names of the 15 people, craftsmen which the Germans selected for slave labor and who, miraculously, survived in the Chelm prison:

Shloime Brustman – a tailor (today in Israel); Berl Kelberman – a tailor (today in America; Rokhel Kelberman, Berl Kelberman's wife (today in America); Tankhum Nisenboim – a carpenter (today in Brazil); Khaim Sobel – a spats [gaiter] stitcher (today in Israel); Isser Zilber – a tinsmith (today in America); Shloime Bubes – a shoemaker (today in Israel); Hersh Buxenboim – a shoemaker (today in Israel); Bentshe Mitzfliker – a tailor (today in Canada); Gitel Liebhober – a seamstress (today in Poland); Golde Laks – a seamstress; Manis Zitrin – a stitcher (today in Israel); Samuel Liebhober (in Poland); Moishe Najman – a tailor ((in Israel); Yekhiel Szczupak – a cap maker, died after the liberation.

Other than these 15 martyrs, there was also a sixteenth person, Yakel Binsztok, a radio technician. He fled right before the liberation from prison and died during the Polish resistance in Warsaw.

[Page 568]

Thanks to Yakel Binsztok, who fixed the officers' radio apparatuses, he had an opportunity – as he regulated the apparatuses – to often hear news which he gave over to his friends about what was happening on the war front. Also, the doctor of the Gestapo comforted them so that they would not lose strength and hope.

On July 20, 1944, the Germans ceded from Chelm. The Gestapo had received an order from Lublin to burn the prison with all the prisoners inside. But the commandant did not carry out the order, and miraculously, the fifteen Jews survived.

The last three days were the worst, because the Germans were no longer in the city. But the men heard shooting, so they hid in the cellar of the prison and lay there without food or water, without light, and without air to breathe. When they finally decided to crawl out of the cellar, because their lives were no longer manageable, they just happened to crawl out onto the feet of a Russian soldier, a guard, who, miraculously, did not shoot them, but he summoned the higher Russian officers who – after an investigation – gave them food and photographed and filmed them.

[Page 567]

Recorded by: E. Winik

Translated by Pamela Russ

After the liberation of the German tyranny, the few Jews of Chelm decided to remain together. They found a Jewish home and settled in. The house was on Pocztowa Street, number 39. Very quickly, the house was turned into a center for the Jews coming in from the entire area. Of those Jews who were hiding by the Aryans, there were several Jewish daughters: two daughters Baden (they once had a laundromat); a girl Butshe – a daughter of Goldstajn; Avrohom Berland's daughter, Lederman's daughter, and some other women.

At the first meeting, there were already eighteen Jews, Chelmer, and at that time the mayor Mr. Gut, photographed all of them.

The first Jew who returned from Russia was Mr. Bibel. Today he is in Israel.

Life continued under all these conditions and loneliness. They used the women's section of the Beis Medrash [Study Hall] as a place for these newcomers to sleep.

The new Polish government instituted some new actions against those who were active Polish collaborators with the Germans. I, in the name of the Jews, also instituted some actions against those Poles who had taken the property of the Jews in the community. They had taken the seniors' home, the Talmud Torah [school], the cemetery, the baths, and so on.

The Polish village elder recognized a group of Jews as the new Jewish municipality. This Jewish committee was made up of:

[Page 568]

Sh. Brustman, Manis Zitrin, Ponczak, Alegant, Yisroel Kuper, Gedaliah Bakalczuk, lawyer Hersh Derfer, Yosef Rolnik. They organized significant aid work; opened the Batei Medrashim [Study Halls], provided the Jewish soldiers with food, especially for the Jewish holidays, and so on. Later, they already received a subsidy of 10,000 zlotys a month from the Jewish Central Committee in Lodz.

In 1945, when the situation became unsettled in the land, some Poles began to attack the Jews in the streets. They even began shooting at some of the Jews in the town. It was then that the thought came to flee from Poland. I left to Germany at that time, where I remained for some time, and then got to Israel with the illegal Aliyah.

* * **

Twice, the Germans set fire to the synagogue. The first time, the firemen put out the fire, and the second time, when the woman ran out – from Borukh Tzale's yard – and she began to scream and to cry about the fire, and she ran to save a Torah scroll, the German murderers threw her, a living human being, into the flames of the synagogue.

Later, the Jews had to remove the stones from the synagogue, smooth out the place, as if nothing had been there before. In the synagogue, the Jews found the bones of the woman Laks, who had been burned in the fire.

[Page 569]

by H. Akhtman, Canada

Recorded by: E. Winik

Translated by Pamela Russ

The soldiers surrounded the Jews and herded them over to the churchyard. People were coming from all directions. They were herding the rich and the poor, old and young, small and big. You heard bombing. In those places where the Gestapo could not find any Jews, they threw grenades and killed those who were hiding.

It was already nine in the morning. My brother, Moishe, came with a group of people. We asked him for news. He told us that he left the city with another family, but the Ukrainians caught them in the fields. They were forced to undress and then they were searched for money. But when the Ukrainians did not find any, they quickly chased my brother and his group into town and brought them to us in the church.

In this place, there already were Dr. Welberger and his entire family, all the officials of the administration, all the workers of the official German work sites. Everyone was brought here, without differentiation. No longer did they look at the work permits, they were now worthless. If you were Jewish, then the fate was the same – to come to the churchyard, where hundreds of soldiers were standing and filming us.

I looked and waited: Maybe they would bring my parents. But we wished more that they would be killed on the spot. At least they would not have had to see the horrific tragedies that were befalling everyone.

It was already eleven o'clock. They were bringing people without end. Next to me stood my cousin with a smashed up head. He tried to turn away, but a soldier immediately fixed that thought. He did not feel the blood that was running from his head. “It's nothing,” he said. But when they brought the Judenrat at noon, everyone understood that now it was serious, we would all be evacuated. But the soldiers set aside Chairman Frenkel, and near him – the technician Tenenboim, and their families. A new thought arose. Maybe they would not evacuate all the Jews and maybe we would actually be the lucky ones. They also brought Anshel Biderman and they set him near us.

He began to scream and beg Frenkel to save him. But Frenkel did not even look at him. He now had no more energy. The soldiers calmed Biderman by showing him their gun.

Rivers of people were coming and coming, but the Germans remained calm. It was lunchtime. They left behind a small number of soldiers with us and then they left.

My brother Moishe had a small package of food with him, and a bottle of milk. We took nothing with us. He took out small pieces of challah and shared them with us and told us that we should save the bread for a darker time. He believed that even worse times would come.

I was happy with one thing, that I did not see my parents

[Page 570]

I wasn't sure that they were alive, but at least they were not watching this terrible tragedy.

Two pm. All the Gestapo men and their chiefs were present. My heart was beating. Who will have the fate to live and who will have to die? Some faces were pale, tired – some, strained some – indifferent.

The chief and his officers went around and looked at the crowd. Our lives were in their hands, and really only the strongest, healthiest, youngest were selected to remain alive. There was already a small group in the middle of this place, and they now had some hope of remaining alive. The chief saw my husband and called out his name, and he pulled me along. But my hope was very small. The chief looked over all the people, the lucky ones, saw me, and ordered that both of us should go back and be sentenced to death.

We went back. There was tremendous chaos, screams, cries. Nothing helped. One Gestapo man approached the young Levenhertz and ordered him to go to the selected group, but he said that he would only do so if his wife and child came with him. Understandably, the Gestapo man did not take well to this, and Levenhertz remained with his family among the so-called dead. This was the only incident where a man did not want to save himself without his wife. All the men left their wives, children, mothers, fathers, anything so that they would save their lives.

Dr. Wolberger also wanted to rescue himself, so when someone took him out earlier, another person, with one beating, pushed him back into the “dead” rows. In the end he was successful. He and his son were included in the living.

Time passed, and the group of people sent to their death grew, becoming larger. They were still bringing people out from hiding places. I begged my husband to save himself, it would be terrible for both of us to die. But he did not change his mind. We calmed down, were watching the goings on, and at the same time waiting for our death. I didn't know where my brothers were, I was only watching people fighting for their lives. In a minute, a familiar officer passed by my husband and winked at him. I pushed him out of the rows, and I heard only his voice: “Hela, save yourself!” I tried to do that right away, I looked at the officers thinking how could I fool them, how could I sneak into the group of the living. I tried to take just a few steps, but the evil eye already saw my efforts and was now watching me. It was getting dark. The soldiers began to form us into four people per row. I looked around and searched for my relatives. Yes, I found Moishe, my brother, and I asked about my two younger brothers, Yankel and Borukh, and he told me that they were lucky to be among the living.

[Page 571]

It did not take long, and 6,000 Jews, set in rows of four, marched out of the churchyard and went down with the piarske [“clerics”] Szenkowycz and Kolejewa to the ramp. The lines were surrounded by soldiers. The rifles were loaded, ready to shoot, positioned downwards, pointing at us. I went near my brother. I couldn't let go of the thought of fleeing. The words “Hela, save yourself!” did not stop ringing in my ears. I heard them and I had to do something. In front of my eyes, I saw the houses that we passed, and I could see nothing but the angry eyes of the Gestapo men and the points of the rifles. But I did not lose hope.

It became dark. A soldier passed nearby. With my eyes, I tried to plead for mercy, but he moved the edge of the rifle closer to me. And that's how we approached the ramp.

The train was not yet there. The Germans organized us so that we sat down on the ground and waited. Once again, people were trying their wiles. They took out their papers from German places and showed them to the officers, who pretended to read them and then ripped them up. They [the Jews] said that they had been working all the time, they mentioned the names of important German officers, but it made no difference. Children were crying, mothers were crying along with them.

Suddenly, I saw a young, beautiful girl. Her name was Gross. She was speaking to a soldier, and the soldier took her and left with her. We believed that he took her back into the city. She left behind her mother, a cripple, and she was gone.

I walked through the rows [of people]. Morgenstern's wife and two children were sitting quietly. Not far from there was Wolbergerowa and her daughter, and Pesha, who had worked all the time for Dr. Wolberger. Wolberger's wife told me that she was trying to run away. Then Dubkowski's daughter approached me and asked why I was here and why I had not saved myself. I told her that I had my Polish ID card but I wanted to see what would happen to my family, and that is why I was waiting until the last minute. But

|

|

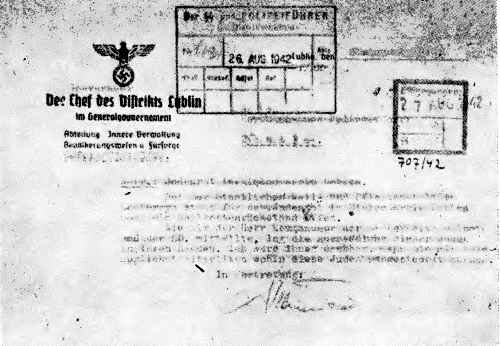

| A document from the Hitler tyranny |

[Page 572]

then after that I would save myself. And in that actual minute an officer passed by, and I asked him where I should go for nature's needs [to relieve myself]. He took me aside, I sat down, and he was holding a loaded gun. In a flash, I grabbed him and said these words:

“You are a human being, you have a heart. I want to live. I am still young. Let me live!”“Run,” he said to me. “But I have to shoot.” At that moment, another officer approached and he asked what I wanted. The first officer said that I wanted to die. He slapped me on my feet, I crouched and crawled back to the group. Now I am resigned, I knew that I had to die. I looked for my brother Moishe, and they were calling for everyone to stand up and get into line.

The train arrived. As before, together we approached the living grave.

At the door of the train, there were soldiers standing on either side with clubs in hand, and whoever approached the door's entrance was beaten by them. When I had already stepped across the entrance, I heard a cry: “Oy!” and my brother was clutching his head. The club had found his head.

The trains were for animals, filthy. In each car, more than 200 people were packed in. There was nowhere to sit. Everyone had to stand. I leaned gently onto my brother.

Soon someone found a match, and then there was some light. I cannot forget the scene of a young girl, maybe 15 years old. She took out a piece of bread, began to eat, and then said: “This is not yet the last time. I have stood before death three times, and I am still alive.” I stared at her and was amazed at her courage to live. My brother also took out some milk and bread and shared them with me. I told him to give some to others as well, and he replied that we had to remember the dark hour [that would be coming]. My brother had a true Jewish heart, never able to decline anything for anyone, so I wondered at his words.

I said to him: “Moishe, it is easier for you to die than for me. You do not have This World, so you will have the Next World,” because he really believed in the Next World. But he answered that he did not know. He broke away from this belief. I asked him what he believes in now, is it better that he jump through the small window and meet his death? But he said that he believed in Sobibor there could be a camp, and maybe he would be selected to go to this camp. With this, I stop talking to him.

There were people standing around us, children were crying. It was dark. We were locked in from outside and the train began to move. We heard voices, and we felt people pushing closer to the window. I asked:

[Page 573]

“What is going on?” They told me that two people jumped out of the window. I now also wanted to try, but the person next to me said I should not go because the officer already noticed and he was holding his gun ready to shoot at anyone who was looking out [of the window].

The train was running at full steam, the clanging of the wheels slowly put everyone to sleep. We were being taken to certain death. I felt nothing, I am indifferent, let's do it as quickly as possible. Once again I heard whispering and there was pushing. I learned that once again someone jumped out. I asked my brother if he also wanted to try, but he declined. I did not answer him, I did not say goodbye, and I stepped right through heads, feet, and bodies, and I was right near the window. The train was running very quickly. I asked myself: How should I jump? I heard a voice saying that I should jump in the same direction as the train was running. I asked for help to push me out and strange hands pushed me to the window. My feet were already hanging out, I am only holding on with my hands on the window, and am hanging on. I was not thinking, only going by instinct. I felt nothing, and only heard voices. I knew nothing, and with one push against the wall of the train, I jumped down.

I don't know how long I lay in a faint. I opened my eyes and began to remember where I was. I saw a figure approaching from a distance. I asked her soon, is it true that we were going to Sobibor? And she replied, yes. They approached the gate of Sobibor, and when the train stopped, she was able to jump off the car [of the train]. She left her mother behind in the train, and her mother threw out a winter scarf after her, so that the girl would not be cold.

I looked around. My bag lay open and my house keys had fallen out. I gathered everything together and, unknowingly, I felt a lot of wetness. I look – a puddle of blood. I move a little, and feel my chin. I put my hand there, and I had a hole under my chin. It seemed that when I jumped out [of the train] I fell face down on a rail and cracked open my chin. I removed my scarf from my throat and tied up my chin so that it did not hang down. Until this very day, I have a scar under my chin that remains from that time.

I do not remember the name of the girl. We both decided to get off the rails and stay there for the night. We both sat down near a bush and we covered ourselves with her mother's scarf. I was shaking, either from the cold or from the loss of blood. I could not stay in one place. We waited that way until dawn and then went wherever our eyes took us. Neither one of us knew the area. Suddenly, we saw a farmer's hut. My friend was very afraid that they would recognize her as a Jew. She did not speak Polish too well. I told her not to speak too much, that I would take care of that. When we entered the house of the non-Jews, they became frightened of us. I

[Page 574]

quickly made up a story for them, that the Germans wanted to take me to Germany for work, but I jumped off the wagon and got hurt. They gave me water to wash myself. I washed out the scarf and then put it back on. My coat was completely bloodied, but I could do nothing about it. I looked into the mirror and saw that my face was totally cut up and swollen. The Christians gave us warm soup and pieces of homemade bread. My friend ate well, but I could not swallow even one spoon.

I wanted to pay these peasants and took out 20 zlotys but they put the money right back into my pocket. They showed us the way to Chelm, so we left the house and went on our way.

We were going and going, and it was already getting lighter. We arrived at a small village near Chelm, I don't remember the name. We wanted to have something to drink or to find a place to stay overnight. But my face, it seems, told the truth. Everyone sent us to the village magistrate for permission to stay in the village and to get something to eat. But after many tries, we resigned ourselves to the situation and went into the forest where we found a deep ditch. We collected many fallen leaves from the ground and lay down to sleep. I was very cold. It was a beautiful day with sunshine, but I could not warm myself. We stayed like that for many hours. Then, in the afternoon, we left to go to Chelm. But just as we started on our way, the farmers, who were just on their way home from the weekend annual market day, warned us that we should not go to Chelm, because terrible things were happening there. They were still hunting for Jews, and when they found the Jews, they were shot on the spot. But it seems that my bloodied coat and wounded face revealed who I was.

But this did not stop us. We had no other way to go. We arrived in Chelm in the evening. When we arrived in Oblonski, a Christian approached us and shouted that the Gestapo was not far from the metalworker's place. We went to medic Prukhnyok's place, with whom we had lived for many years, but his sisters did not want to let me in, even though I asked for medical help.

We continued on Oblonski to Kopernika Street, and were soon near Szenkewicza Street, when a watchman stopped me and learned that I was Jewish. Meanwhile, my friend moved away from me and left without me. But, with all my courage, I reply [to the watchman] that he had no proof that I was Jewish, and on the contrary, I could prove to him that I was Polish. I took out my Polish passport and showed him. He let me go and I ran after my friend. From far I see that he

[Page 575]

was taking her away. At that moment, I was separated from her and never heard from her again. I went back to Kopernika Street, and thought that Liebhober's wife was taken out of the group because she used to sew for the wives of the Gestapo men. I would certainly find her at home, and she lived in Akhtman's hotel. She and both of her children actually did survive, and I saw her in Chelm in 1945. But before I could get there I was stopped by an officer. He looked me over, from head to toe, but he did not arrest me. I calmly went into Liebhober's house, where there was no one to be found. The beds were still made, and everything was still in order… The clock on the wall was still ticking. It was six o'clock in the evening. I removed my bloodied coat, and threw myself onto the bed in my dress and shoes.

Not long after I was lying there, about half hour later, I heard footsteps on the stairs, heavy steps, and of many people. The door of the second room was opened, and two officers with one young non-Jewish woman came in. From their conversation I understood that this non-Jewish woman was looking for clothing that she had left behind to have sewn. I heard how they opened drawers and were looking into the closets. I did not move, and at the same time, I covered myself with a pillow. They came into my room, turned on the light, looked around, and did not see me, even though my feet were actually poking out of the bed. I saw them: two tall military men and a non-Jewish girl. After a few minutes they left the room and locked all the doors. I didn't think about it and soon fell asleep.

When I woke up it was still dark. The clock was no longer ticking. I was not lying there for long when it began to dawn. I was afraid to put on the light and when I was already beginning to be able to recognize objects I got off the bed and looked around the house. I did not find my coat in the same place. Seems like the Germans thought about it and then returned it. I tried the doors, but they were all locked. I did not see any way out. I was in a living grave… I went from one room to the next with the same result. I did not know what to do. I tried again, but all the doors were steeled shut, not able to be opened. Suddenly, I saw another door, it was only chained. I opened it and entered a small room with one broken window and I saw that there was a balcony right at the window. The balcony had steps and they led into the courtyard. I did not think any further, I grabbed a man's black coat and put it on me, leaving my bloodied coat in the house, and crawled through the window. A piece of the pane that I touched, fell off. For a moment, my heart stopped. But I didn't hesitate and climbed through. I was now in the yard and ran through the gate. The watchman just happened to be sweeping the street. I edged my way up to the wall like a shadow and very soon, I was on Kopernika Street. I was finally free!

I ran as fast as I could. My own steps frightened me. I was already

[Page 576]

on Pocztowa Street. I didn't look around. My feet were moving by themselves and my eyes were looking out on their own. I already passed my own house. I had a quick look and no more, and went through the fields to Zolvanez where my shikse [Christian female] that I knew lived, and on the last day she had gotten me a passport. A Jewish girl wearing a scarf ran ahead of me and told me that it would be better for me to go back because the peasants in the village would inform on me. I did not answer her, but continued on my way. I did not know the exact route. Only once did I go with this shikse for a walk and she showed me the way. But at this moment, I felt that I was going by instinct. I could have found the right way even with my eyes covered.

I came to the house in about an hour. I snuck in through the door of the courtyard. No one was in the house except for the shiksa's mother. I asked her where was Zhenni, it was Sunday morning. She had to be home at this early hour. I said that I wanted her to sew something for me. The mother sent her small son to find Zhenni and in a few minutes she came in. She cried when she saw me. She immediately put me to bed in a second room where no one would come in. She gave me water to wash my wounds again, and then she gave me warm milk. After two days of starvation, the warm milk was very delicious. I told her about my tragedy and said that I did not know if my parents were still alive. I had 900 zlotys and gave her 200 for her father and I told her to hide the other 700. I told her about all the things that were hidden in my house, and then asked her to try and get them out.

At night, she put me in the attic with some hay. She organized a place for me to sleep in the hay, and she made a small wall of the hay so that if someone came up they would not see my place under the hay. I stayed in hiding there in the attic until the 17th of November. That means, from Sunday, November 8, until Tuesday the 17th. Zhenni came to me twice in the day, in the morning and at night, and brought me food and told me about any news. She was afraid to come during the day in case neighbors would see her. On Monday night, Zhenni came as usual, and brought me food. She told me that my parents were alive. She had been in my house and had spoken to my parents through the walls and gave me their regards. They were very hungry. I begged her to give them some bread and milk. She agreed. In the morning, when it was still very dark, Zhenni woke me up and gave me her mother's clothing, and like two peasants, we went to town. She told me that she would not even approach my house because just for crossing the border into the ghetto she would be shot. I had a small basket of food with me. The German guard was standing 10 meters from my house. I went in, knocked on the locked door and called out “Mama!” I do not have to write how I felt at that moment. There are no words to describe this. I was not afraid. A quiet voice answered, it was my mother-in-law. “It is Khaya, our

[Page 577]

Khaya…” And then my father's voice: “Give us water!” I left the basket behind and went, in the dark, to try to get a cup of water, but everything was dried out. I went to a neighbor of mine, and I almost fell into the open cellars from which they had dragged out the people who had been hiding there. I did not find any water. I had to go into the yard to the well and collect a bucket of water that I had to carry over. I called “Mama” again and I heard my father say to my mother: “Say something so that she will hear you.” The first words from my mother were to ask if the children were alive. I told her that all her children were free in the Gestapo, and that Moishe, who was already burned alive, was hiding, and that I too was well hidden. We would still have to wait until Sunday the 15th when they would open the ghetto and then we would go back home and all be together again. I left them with that hope and went with Zhenni back into the attic.

And now my mind began to work about how to help my parents. What could I do, how could I save them? Not even one single idea came into my head. I did not sleep, I could not eat. At that moment, even though I was not a believer, that God should shorten their pain with their death. Yes, I asked for my parents' death so that their suffering would stop.

My Zhenni began to complain that she was getting scared. She was not able to get any more bread and no more milk either. I pleaded with her, and she agreed to go one more time, Friday at dawn. I disguised myself again, and brought them [my family] some bread, milk, and borscht [beet juice]. They did not ask any questions, said goodbye quietly, and again I left to my place.

I knew nothing about my husband and two brothers who had not come with me. I had no contact with them. I began to plead with my shikse that she should come with me into town, but once again she was frightened. After much pleasing, her brother promised to come to town with me on Sunday to try to find out where my brothers and husband were.

Sunday morning, I once again disguised myself, and at 10 o'clock, I and the sheygitz [non-Jewish male] went to town to find my dear ones. I came to Lwowska. It was quiet because not many people were in the streets. I went passed my house and just glanced to the right where my parents still lived. I had just come to Pocztowa Street, that once was a lively street filled with children, parents, with great activity and liveliness, now all died out. Not even one soul, not even one step was heard. Broken windows, destroyed benches, tables, seats, dishes in the streets. Thousands of pages from books, thousands of papers flew in the streets. It was terrifying just to look at the street. Everything was dead.

[Page 578]

Not long ago the streets were noisy with thousands of voices, with the center of the ghetto. But today – no sign of life, only the white papers. If the winds could speak, they would tell of the tragedy of Jewish life. With a downcast head, silently, I walked through the Jewish grave of the former life.

We went back in the direction where I hoped to find Jewish life and when I came to the public new school near the train center, there were Jews there, standing with shovels and axes, working. It made a strong impression. These were faces that were already not alive. The faces were still moving, but death was already etched on their faces. With my eyes, I looked for acquaintances. I heard a whisper: “There is your sister.” I looked around, and I still did not see a face that I knew. In a minute, two faces separated themselves from the ditch and looked up at me. I recognized them. They were my two younger brothers, Yankel and Borukh who saved themselves and did not go to Sobibor. A soldier stood at a distance. We turned off the road slightly, and we began to talk. The first thing they said was that our parents were dead. I assured them that our parents were still alive, but that our oldest brother Moishe was dead. We were not able to speak for long, but they told me that my husband was working back at the Gestapo and when he could, he would bring them a piece of bread. My husband was better off then they were. My heart ached looking at my youngest brother, without a coat, frozen solid, brown and blue. But I could not help them. After a few minutes, they left me and went back to work. I never saw them again. In about three days, I learned that they were both shot.

I continued on to the Gestapo, but I did not see my husband. The sheygitz was getting restless and he wanted to go home. He was afraid to go back with me so he sent me through the woods and went home the regular way.

In the shikse's home, it seemed that the parents had discussed me and decided not to allow me to stay any longer. When I came home, they told me that they were frightened to keep me any longer. I had no choice and I promised them that I would leave that week.

Monday night, once again Zhenni, the shikse, came up to me again, and brought me the real news. Her brother was in town on Monday morning, and saw how they had taken out a group of Jews from our house. She told me about certain details, and I was certain they were my parents and my mother-in-law. What I felt then, I cannot describe, but still, I begged her to come with me once more to my parents and see what had happened there.

On Tuesday morning, I changed my clothing, took a small basket of food and went on my way.

It was still dark when I arrived there. As usual, the shikse with me remained on the other side. With an empty head and without any thought

[Page 579]

I entered the house and I will express, in my own words, what I saw.

The door to the hiding place was open. I did not call out “Mother! Father!” any longer. I entered the kitchen. The windows were covered with sacks (seems that my parents believed that they would come out [of hiding] on the 15th of November) but when they came out [of hiding] they were afraid of the light, that they should be seen, so they covered the windows. There was freshly brought in wood in the kitchen, on the table were freshly grated white beets, which they usually fed to animals. Seems that they were hungry, but they would not have the opportunity to eat.

When I left the house, I saw a rubber boot that my father had lost when they

|

|

| Jews doing slave labor under the Nazi government |

led him to his death. I did not cry, I did not speak. A rock was in me when I came back with the basket to the cemetery where the shikse was waiting. To her question of how were things, I responded with nothing. I left the small package in the cemetery and went to look for my husband. Now I no longer had to remain in the city. Nothing was keeping me there.

Calmly, we went into the city. It was still very early, but when we passed the train depot

[Page 580]

the Jewish slaves were already working. I looked around, searched, and did not find my brothers. They likely worked in a different place. My husband was not there either. We went to the Gestapo, into the lion's den. The Gestapo men knew me very well because I had worked there all year, but I was not afraid. We came to the Gestapo gate at 8:30 in the morning and we hoped that if one of the workers would come out then we would ask him to bring out my husband. We waited like that until 12 o'clock, but no one came out. The shikse did not know my husband. I had only a small picture of him. She took the picture and approached the windows of the Gestapo and looked in. Suddenly, she saw a face in the window and she winked at him. He came down. When he heard her out and came down from the Gestapo, she approached him and showed him the picture. She asked him if he knew the person in the picture. That person was my husband, and she told him that I was waiting for him at the gate. They came out together. I saw my husband, but he no longer looked familiar to me. His head was shaven, he was blackened, with scars on his face. I could not believe that in such a short time he could change that much. We did not speak a lot. He had only one request, that I stay with him for just one day. He would sneak me into the cellar and we would be there together. But I declined, I do not know why. Maybe I felt that life was no longer a life, but on the way to Kielce I was sorry that I did not stay with him. I told him about the death of our parents, we squeezed each other's hands tightly, and parted without any hope of ever seeing each other again. I went home to the shikse's house, took along the 700 zlotys with me, and nothing else. At seven in the evening, I left Chelm.

I went to Kielce because my husband had two sisters in Stasow, near Kielce.

* * *

This was one episode of Chelm during the time of the Aktzias [roundups]. How I came to Kielce and how I saved my husband is a different chapter of the unnatural episodes and events.

[Page 581]

by Yoshe Akhtman, Canada

Recorded by: E. Winik

Translated by Pamela Russ

When they separated me from my wife, I remained with another 200 or 300 Jews. As was usual for the Germans, they screamed at us and beat us and set us in rows, and then ordered us to go, without looking around, just to go. The large group went on Pijarska Street, and we, the smaller group, went a little onto Lyubelska Street until Perockjega Street and the train station – past the Jewish cemetery.

It was a labor camp, where they crowded us all in, one on top of the other.

When we organized ourselves a little, and became calmer, night had fallen. We had no light, there was no window. Everyone sat with his own thoughts. Quiet, no one was speaking.

Suddenly, we heard footsteps. Thousands of feet, and a familiar German yell: “You lice! Lice! Get up, you cursed dogs!”

We heard sticks beating heads and people screaming: “Oy!” We began to move. One person wanted to get out, then another, but they did not allow anyone to go out. We were all men, and suddenly a cry is heard, as if everyone had planned this. One cry from all 300 men, but a quiet, choking cry, because everyone was afraid to cry loudly. The Germans hated the cries. In these cries, you could hear complaints to oneself: “Why did I not go with my father or my mother, with my wife, with the children? We know that they will keep us only as long as they need us, and then the same thing will happen to all of us. So why do we have to suffer? Isn't death for all of us better?” The thudding [of feet] became quieter.

In about two hours, when everything calmed down, they began to set us out in three different rooms.

The room I was in once held hay. It was obvious that there was once hay since there were many tiny stones left behind, and we had to lie down on these. We lay one on top of the other. With us here was a Jew and his son from Germany. The small rocks were digging into the Jews. He cried, it was not comfortable for him. There was also a porter from Chelm, I do not remember his name, but he was a strong young man. He was stabbed in the side with a switchblade by a German. It hurt the man terribly. He was not able to lie down. He cried out of pain, but no one could help him.

Suddenly the door opened and the camp elder entered with a question: Whoever was not feeling well or was sick and wanted to go into another room should go with him. Understandably, the German man and his son and the wounded porter left with him. We never saw these people again. They were shot that same night.

On the second day, that was Shabbath, all of us were let out into the yard, each one of us received

[Page 582]

a piece of dry black bread and some bitter coffee. It is noteworthy: We were not guarded by any Germany military but by the Jewish militia. A Jewish police was standing at the gate, and at the fence, the same. This was our entire guard setup because the Germans were sure we would not try to run away because we really had nowhere to go. If a Jew was found in the city then he was shot immediately; if a group was found then they were taken to prison until they became a larger group, when they were taken to the field on the way to the lake, and there was a large dugout ditch. And when a group was brought there, they were spread out with their faces looking down into the ditch, and from behind them the shooting began so that they fell with their faces downwards on the ground. Earth was then shoveled over them from the top.

There were no more Jews from the city coming into our camp. There was nowhere left [in the city] to hide because if you were seen by a Pole he would immediately hand you over to the Germans. There was no food, so that the Jews gave themselves up on their own.

As we went out we were counted and the same when we returned. Once, this happened: On the second day of being in the camp, right in the morning, a shout was heard that everyone should line up. The camp elder (the camp elder was a civilian German from Germany) approached, and called out the name of one of the Jewish militia and then he asked that one of the death cells be opened. There, people who tried to sneak into camp or committed other crimes were kept. From these cells, the people were taken out and shot.

The camp elder demanded that a woman be brought out, and this was the wife of the Jewish militia. He called out

|

|

| The Jews working in the camp. On the sides, you can see the Kapos [a prisoner assigned by the SS to become supervisor and functionary] guarding them. |

[Page 583]

loudly, that the Jewish militia had committed a crime by sneaking his wife into the camp, and now both he and his wife would be shot in our presence so that it would be an intimidation for others, so that they would remember this.

After he shot these two young people, he left and told us that they had to remain lying there in the middle of the place all day and then he told everyone to disband. I passed one of the death chambers and I hear my name being called: “Yoshe! Yoshe! I beg you, give me a piece of bread! I haven't had a piece of bread in my mouth already for three days. I am together with my brothers-in-law.” We summoned a few more people and we made a human wall. The one in the back kept an eye out so that we should not be seen. I looked around carefully and gave the woman my entire loaf of bread. I and my brothers-in-law were placed into one group of workers. We left to work and when we returned the woman was no longer there.

We worked on the road that led to the direction of the large shul [synagogue]. It was very cold. My two brothers-in-law, two young boys, one 15, the other 17 years old, were also working. When they left the house it was still warm so they did not dress themselves warmly. My heart could have exploded as I watched them. The cold shriveled them. Once, something good happened to them: Once, we were there working, and we saw how a group of Jews was being led by young Hitlerists. When they saw us they began to laugh and taunt us. The group of Jews was comprised of 15 people. I remember how one mother was holding her child's hand and was carrying her other child in her arms. Not far from us, all the Jews in the neighborhood had been shot, and these thugs, with smiles, were staring right into our faces, preparing for other victims. They removed the coats from these dead and put them on the living dead.

As we were working on the road, we saw every day how they took wagonloads of dead Jews to the Jewish cemeteries where a large ditch was dug out, and all the bodies were thrown in.

This work was headed by a Gestapo man. That means, that the workers were Jews but his job was to watch whether we Jews would search in the pockets of the dead Jews. That means that all the dead were searched to see whether they were taking money or gold with them.

After working for a week in the camp, they took me back to my old job, where I worked before the camp, in the Gestapo. My job was to polish boots, heat the ovens, and keep the cupboards clean. We were four Jews who did this. Each one had to serve eight men. Some also had to take care of the wives and children. The Gestapo tried to replace me with a Pole, but he did not work like the Jews and everything was very filthy, so they had to ask for me to come back. I now had to do alone what was earlier done by four Jews.

[Page 584]

When I entered the house, I found other Jews there. These were skilled workers. I will try to mention them by name: Chelm carpenters by name: Yosel Milkhman, Aharon Hos and his son, Tantshe Nisenboim and a cabinetmaker from Kalysz. Of those, the only one who survived was Tantshe Nisenboim. One tinsmith – his name is also Blekhermakher [which means 'tinsmith”], he also survived; two painters: Lipa Goldman, and Stolnik. I don't remember his second name; one upholsterer – Yosele Eisen, a brother-in-law of Lipa Goldman.

At this time, I want to describe how Lipa Goldman's brother, Mottel, died. He was a stitcher of gaiters, as I was. He was a major figure in the handworker's union. Everyone remembers him. This is how he died: The entire time, until the final Aktzia, he was working for the German gendarmerie. They detained him during the last Aktzia, not allowing him to go home. Two weeks before the Aktzia, the Germans told him that they would shoot him, but that he could save himself with money. He said that he had no money with him but he had some money hidden at home. The Germans were not lazy, and they went home with him. When he took out the money and gave it over to the Germans, they beat him and shot him on the spot. In the Gestapo, I found a very nasty person who was like that from before the war, and during the time of the war, he also did terrible things. He was one of the worst informers – this was Abish Kershenboim. They used to call him “the yellow Abish.” He had his own shop in the “Rynek” [square]. The Gestapo kept him because they still wanted to found out everything they could about the Jews through him. After two weeks, we noticed that two Gestapo men left with him and came back without him. This was the end of an ugly creation, Abishel Kershenboim. His brother Fishel, deaf, died in the first group along with all the other Jews.

Now my work was four times greater than before, and much more, because after the frost it became warm and it rained. Every day, I saw through the window how they were taking groups of Jews to be shot. The Gestapo men would come back with their boots smeared with blood mixed with mud. Sometimes I had to scratch off the blood with my fingernails, and sometimes I had to clean off the blood from the uniforms. Some had blood on the sleeves, past the elbows. I had to scratch with my nails because the Germans loved cleanliness. I had 28 pairs of boots and I had to polish them from seven to seven thirty and to heat up the offices because the Germans also liked when it was warm. I had to get up before dawn so that I could do all this.

We all slept in the carpenters' warehouse. Once a week we went to wash in the prison that belonged to the Gestapo.

Once, as we entered the prison yard, we saw two familiar Jews, beaten up. Seemed that

[Page 585]

they had just been brought here. One was the “fat band” but he was no longer fat. Everything was hanging from him. The other was the son of Warsaw's cake baker. He was called Bakh. Both were terrified, blackened, half-dead people. We never saw them again. Near the bath where we washed ourselves there was a cell for captured Jews.

Once, when we arrived, we saw this picture: We had to wait for a while. As we were standing there, we heard moaning. We looked through the peep hole, we saw men, women, children, and girls all completely naked, without shirts. Among them we recognized the older daughter of the woman Horowyc who had a perfume store on Lyubelska Street. Later we found out why they were keeping the people there. Because during the time that they were in the room, their belongings were searched for hidden money or gold. When everything was ready, they were chased out and everyone had to quickly dress in their clothes. All this time, they were hit over the heads with clubs, so that there was no time for anyone to find his own clothes. A tall person grabbed short clothing, and a short person grabbed long clothing. Everyone looked ridiculous. Then they were taken across the city, into the field, and shot. All along the way, they were chased and beaten, just as a pig beater would torture the pigs. With an earlier group, I saw how they were taking men,

[Page 586]

women, children, and among them I saw the old man Moishe Tukhman. He, tall and thin, she, short and heavy. He was leading her by her arm. He went straight ahead. But the Germans could not tolerate that a Jew would be walking straight. They began beating his head with clubs, but he did not bend. The Germans became upset and began to beat the wife. The elderly Moishe Tukhman bent over to his wife to protect her, but he did not bend for the German beatings. I never saw them again because they left on the train to Sobibor.