[Page 51]

Teachers and Students

[Page 67]

(I have learned) from all my teachers…

by Mordechai Rishpi (Feierman)

Translated by Sara Mages

I remember the first day in which I began to learn and I was four and a half then. It was in the morning of a cloudy autumn day when I and my best friend, Avraham'ele the carpenter's son, played outside with nuts. We liked the game of nuts, played it at every opportunity and it was difficult to pull me away from it. My mother used to say in those days: “Motele' is even willing to sleep in a hole! ”…

Suddenly, that very morning, in the midst of a thrilling game a big and burly young man approached me. He grabbed my arm in his clumsy hand and said: “come, today you're starting to go to the “cheder”! ” The surprising announcement, the ending the game and the painful grip of my arm – annoyed me to tears. I stood and didn't move from my place. The young man, who was a “balfer” (rabbi's helper), showed clear signs of impatience and was ready to load me on his shoulder against my will. Fortunately, my mother appeared at the doorway to the sound of my screams:

– “Motele', you're almost five years old and your time has come to go to the “cheder”with all the boys your age! And do you know? Our uncle, Rabbi Yasel, agreed to take you to his “cheder” despite your young age.”

The truth must be told: my mother's announcement that my “rabbi” would be no other than my uncle, Rabbi Yasel, didn't please me because he was known as an old man who got angry easily, and when he was angry he forgot the whole world. I don't remember a single case in which he used the whip that hung to glory on the wall next to his seat. However, when he announced that “in a little while he was going bother the “kantshtik” [whip],” the “criminal” stopped breathing and his heartbeat rapidly increased…

Already on the first day of my arrival to the “cheder,” when I answered something to the question of my neighbor to the bench, the “rabbi” pointed to the whip as he continued to sway back and forth with the boys. I understood the hint and joined the crowd of little boys who read aloud from “Chumash Vayikra” – “Echad Mikra V'echad – Targum” [once the scripture and once the translation].To this day I can't understand why the Book of Leviticus, which contains no stories or interesting events like the Book of Genesis, was chose to serve as an alphabetical index for the school children.

Eventually, I became part of the class and since I can't remember if I ever received the exclusive treatment of the “balfer” – it may be assumed that I belonged to the group of “logs,” that is to say – those that it was impossible to insert something from the small letters to their “thick heads” even if you broke sticks and straps on them.

Another sign that I was okay: Every Sabbath, after the afternoon nap, uncle Yasel (actually, he was my father's uncle) – my “rabbi” and his wife aunt Rivka – came to us to taste my mother's magnificent “kugel.” After they enjoyed the “kugel” and drank tea with jam (my brother and I ran like “gazelles” and brought a kettle of boiling water from Susie “the owner of the samovar”).

[Page 68]

Then, the “rabbi,” uncle Yasel, turned to me in a special melody: “Yaaleh V'Yavo” the groom Rabbi Motele' and read a chapter from the weekly Torah portion.

Father rested his head on his arm to hear how his “jewel” was progressing. Mother stood on the side with her hands folded and listened intently – in case, God forbid, there would be a glitch. When everything went well, mother gave my brother and me a handful of nuts and we left to play in the hole. The rabbi and his wife – uncle Yasel and aunt Rivka – stayed to listen and give mutual compliments and at the same time participate in the “Havdalah” blessing and eat “Shalosh Seudot” of Motzei Shabbat.

These visits of the “rabbi” and his wife repeated themselves – according to the same plan – for a large number of Saturdays until they stopped at once a result of an incident in which I played an important role. As stated above, the “rabbi” didn't use the whip that hung on display on the wall – “as a lesson for all to see”… Only when a row broke out between two students and matters came to blows, the “rabbi” said casually: “apparently you are very interested that I'll invite the pretty “kantshtik” to settle the quarrel between you two!” Miraculously, the arguments stopped immediately.

It happened, more than once, that the “rabbi,” “bothered” the whip from its place, put it next to him on the table and invite the criminals for an interview. The boy arrived to the “rabbi's” table frightened and waited for his verdict. The “rabbi,” filled his nostrils with “tobacco” (a sign that he was in a good mood), and ordered the boy to kiss the strap as a gratitude that it didn't not “scratch” his back…The student had to make his way to his place the same way he arrived to the “rabbi's” table, and woe to the boy whose face expressed joy that he was saved from the strap's punishment. Then, he had to “taste” one of the punishments which were at the disposal of the “rabbi” who provided them quite generously.

“Standing in the corner”– was the lightest punishment for a boy who didn't pay attention to the lesson and wasn't able to point to the location of the reading. “Kneeling”– was a punishment for a boy who raised his hand on his friend. Usually, the “rabbi,” ruled to both sides together, an equal dose of punishment, “so, God forbid, one of them wouldn't be shortchanged”… So it happened, more than once, that the four corners of the room were occupied by boys who were crouching on their knees. A boy, who was late to class or didn't return on time from a break, received a more serious punishment. In the small shed, where the “rabbi's” wife kept the chickens for the Sabbath, stood a box full of corn kernels. One of the boys was sent to bring several handfuls of kernels in a box. He scattered the kernels on the floor, “padding” for the boy who had to kneel on his knees. If the tardiness was repeated several times, the boy received a punishment that was accompanied by a special ceremony. The “rabbi” ordered to mount the boy on a rake which was brought from his wife's kitchen. His pants were pulled down, the tail of his shirt was rolled up and his head was covered. Each of the students approached, in turn, and lashed the boy's buttocks with wet branches.

One morning my mother woke me up and warned me not to be late for the “cheder” because she had to go somewhere. I promised and fell asleep. I arrived to the “cheder” very late. When I peeked through the keyhole and saw the ceremony that was prepared for me, I retreated my steps, ran home and told my mother that I wouldn't continue to study with this “rabbi.” All of my mother's pleas and my father's threats didn't help – I stood on my opinion: I wouldn't go back to this “cheder”!

[Page 69]

Also the pleas of aunt Rivka, the “rabbi's” wife, didn't help to soften my stubbornness. We liked the rabbi's wife because from time to time she “smuggled” sweets to the boys in the classroom. On Saturday afternoon I left the house long before the “rabbi” and his wife came for their regular visit.

Eventually other boys joined my strike. Several parents, who didn't accept the method of teaching and the penalties in the “cheder,” tried to convince others to accept their proposal to bring a modern teacher who will teach in a “Cheder metukan” [reformed Cheder]. The teacher was Avraham Kotik, a pleasant young man who won our hearts in the first lesson with the song that he had taught us and the textbook that was filled with stories and pictures. This teacher emphasized the form of writing and for many hours we practiced beautiful writing in a special notebook. We liked the teacher Kotik and really regretted that he was forced to return to his family after one academic season.

The only teacher who left his impression on me and many of the town's children was, without a doubt – Nachman Polischuk. A short time after his arrival to Capresti Polischuk managed to establish a status of respect and appreciation among acquaintances and parents, and the most important thing – the admiration of his students. Not everyone was awarded to be accepted to Polischuk's “Cheder Metukan.” The parents were blessed with the fact that their children were given to the experienced hands of a superior teacher. Indeed, he was strict, both in the classroom and outside it, but this unique quality added a lot to his prestige. The children appreciated his patience to explain, again and again, a question that not everyone understood. He also instituted an equal law and treatment for all without favoritism to the sons of the rich (contrary to custom).

Polischuk instilled in his students an attitude of affection and zeal to the Hebrew language. Several years later, as a result of the solid foundation that we obtained in Polischuk's lessons, we imposed the Hebrew language among the members of “Pirchai Zion” [Flowers of Zion]. I remember that he taught us: chapters from the Bible, literature, grammar and mostly – dictation and essays. His dictations were assembled from a collection of sayings which contained words that were similar in their pronunciation.

In regards to essays – Polischuk suggested topics to choose from but left the possibility of writing an essay to the imagination of each student. I remember that one of my essays was examined by Polischuk and by a teacher who was staying with him. When I got the essay back I found written in red ink: “After reviewing your essay we both agree to give you the grade “HLL” ” (Polischuk's grads were from A to H).

It should be noted that I received a special attention from this teacher because of my interest in the foundations of our language and its grammar. I was able to visit him whenever I wanted and was allowed to browse through voluminous dictionaries. The atmosphere of the Hebrew language prevailed in his home and his children, Ruchama and Amram, spoke Hebrew from a very young age.

It's not clear to me if Polischuk was in Capresti during the existence of “Tarbut” school or if he already moved to the town of Sokyriany. I think that he taught there before he came to our town. From photographs, which are brought in this book, it turns out that several of his former students had their pictures taken with him during his visit to Capresti after many years of absence. Individuals, who were active in the town's Zionist movement, also had their picture taken with him at that time.

[Page 70]

To the image of the teacher

Nachman Polischuk (N. Palti)

by Z. Igeret

Translated by Sara Mages

The man grew in the garden of Hebrew culture like a magnificent shady tree. He was self–taught and no one looked after him. He grew underneath it and produced excellent results. He had great knowledge in the sea of ancient Hebrew literature and in the treasures of modern literature.

After a hard day's work in several educational institutions and private lessons, as was customary by Jewish teachers in the Diaspora, he found his rest in the shade of his large and valuable library. He purchased a lot of books during his short life and slept in their bosom. Each time you turned to his country house, which stood at the edge of town and was surrounded by a large garden, you found him bent over his books, and when you entered he greeted you with a linguistic innovation. The margins of his books, which were covered with witty and bright comments, testified to his deep reading. They were lost together with the books that were destroyed. What a pity that this treasure of comments wasn't published.

The man died in his sleep when he was about forty years old. He returned from work strong and happy, lay down to rest for a moment, and never got up. He passed away quietly with a pleasant smile hovering on his lips. The man was collected before the evil came upon the community of Capresti and his family.

This “hall” was visited by famous Jewish theater troupes like: Moshe Lipman and Heni Litton, Boris Thomashefsky, Solo Prizant with Gizi Haydn, Sidi Tulll and more. It should be noted, that not all of them were lucky. Some of them were stuck in the town's swamps for the winter,

|

|

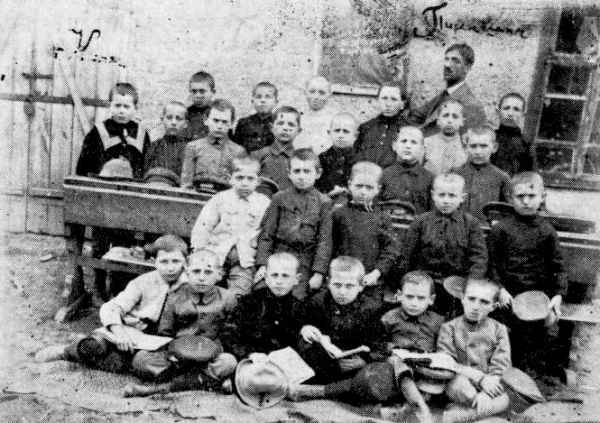

The teacher, Nachman Polischuk, with his students (“Cheder metukan”)

Front row: Yasel Schichverger, Buma Yozis, Yosel Birshteyn, Yisrael (Izrail) Yanovich, Eliezer Seleshtshan.

Second row: Arye (Leib) Mer, Shmuel Mer, Chain Vaykman, Shuka Ayvcher.

Third row: Eli Torban, Aharun Mer, Herzl Haysiner, Leib Froymchuk, Eliezer (Leizer) Yozis, Moshe Broytman, Mordechai (Motel) Fayerman.

Fourth row: Yakov Skeldman (Shomroni), Hershel Mateevich,, Itzel Hersonsky, Velvel Kharkaver, Hershel Feinbaum.

Last row: The teacher Nachman Polischuk (Palti) |

[Page 71]

In the Heder by the Melamed of Little Children

by Boria Yanowitz

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

It is not easy to remember, in all details, the day 65 years ago, when my mother took me for the first time to the Cheder, to the melamed – the Torah teacher of little children. The memories from that time are pale and weak; everything is remembered as through a dream.

The images from the old times were refreshed in my memory by my cousin Motl Turban, the Cãpreºti pharmacist. His parents were among the founders of Cãpreºti and he was born there in 1882. At the outbreak of World War II, Motl and his two sons were cruelly killed by the German-Romanian murderers; his wife Duma also perished at that time.

In 1932, at the celebration of Motl's 50th birthday, he related many details about our cheder and our shtetl in the 80s of the 19th century.

Our cheder, at that time, looked exactly as described by the Yiddish poet Mark Warshavski in his well-known folk-song “In the Cheder:”

Oyfn pripetchik brent a fayerl,

Un in shtub iz heys,

Un der rebe mit di kleyne kinderlekh,

Lernt alef-beys.

[On the hearth, a fire burns,

And in the house it is warm.

And the rabbi is teaching little children,

The alphabet.]

This was how Jewish children learned for years and years, in a small, crowded room, at the home of the melamed, who was poor, the fee that he received from the parents being barely enough for water and porridge… The room we called cheder, the poor teacher Rabbi and his wife Rebbetzin.

The Rebbetzin, with her own many children, would sit in the little kitchen and cook cornmeal porridge, potatoes or mamaliga. The cheder children would often play on the earthen floor, and make little holes and little “hills”. Every Friday, the Rebbetzin would fill the holes with clay, so that the floor would look smooth and clean for the Sabbath. But on Sunday, when the pupils returned to the cheder, everything turned back to the way it was before.

Outside the cheder was a small courtyard, where the children could run around, play, yell and often have fights, until the words were heard “the rabbi is coming” – then everything became calm and quiet, as if nothing had happened…

Two long and narrow tables stood in the room, on both sides of the tables were long benches, and this “furniture” filled the little room, so that there was barely room to move. At the head of

[Page 72]

one of the tables the rabbi sat; at the head of the other – the belfer [the rabbi's helper or assistant]. The many children who came to the cheder were of the ages from 3 to 5, and divided into groups (classes or “grades”]. The youngest group learned the Hebrew alphabet, the second learned to combine the Hebrew letters with the Hebrew “points” [vowels] the third to read words and the highest group to “finish the line” [that is, to read an entire passage] and also Torah and prayers.

The parents registered the children to the cheder only for six months at a time – one semester, which was called zman [lit. “time”]. One zman was from after Passover to two weeks before Rosh Hashana [the New Year Holiday] and the second zman from after the Sukkot Holiday to two weeks before Passover. Tuition was paid monthly. Although some parents could not afford to pay, the children were not sent home, in order to avoid the transgression of bitul tora [neglect of Torah study].

When the child was three or three-and-a-half years old, his father would wrap him in a talit [prayer-shawl] and carry him to the cheder, to start learning Torah. The first day, the rabbi showed him a little board with all the letters of the Hebrew alphabet on it. The letters were big, and six of them [shin, dalet, yod, alef, mem, tav] – the letters of the Name of God and the letters that spelled out the word “truth” – were spread with honey, a hint that the Torah is sweet as honey. The new pupil would repeat after the rabbi the names of the six letters. The father, standing behind him, would toss over him candies and coins, saying: “Little son of mine, this is thrown to you by a good angel in Heaven.” The other children in the cheder would also receive sweets: There was great joy with the occasion of a child beginning to go to the cheder.

In the wintertime, a time of mud and snow, the belfer would carry two or even three children to the cheder; in addition, the mothers would hang on his shoulders little bags with food, for the children's meals during the day.

The rabbi, with a pointer in his hand and a kantchik (a short stick with long leather straps on its end) on the table (for the unruly and ill-behaved) would repeat, with each child separately, the letters of the alphabet, printed in large font on the first page of the prayer book [siddur]. At the end of the first semester the pupil was able to read the entire alphabet.

During the second semester the pupil learned how to combine the letters (consonants) with the vowels, through questions and answers, and repetitions by the group – all in a special rhythmic sing-song, which helped memorize.

The third semester the children combined letters to form words; by the end of this semester the pupils knew how “to draw to the end of the line” – to read the entire line, as mentioned before.

[Page 73]

The fourth semester was devoted to learning chumash [the Pentateuch – the Five Books of Moses] and praying from the prayer book. They began with the first parasha or sedra [weekly portion] of the third book, Leviticus. To honor the occasion, on Shabat afternoon a special party was organized at the parents' home, inviting family, guests, the rabbi and the child's friends. The “Chumash-boy” (or “Chatan-Torah” – lit. “the bridegroom of the Torah) stood on a chair; in front of him, an older boy asked him questions and received answers according to the following model:

“What do you learn, little boy?“

“I began learning chumash.”

“What does chumash mean?”

“Chumash means “five.”

“What “five”? Perhaps five bagel for a Kopeck?”

“No, these are the five books of the Holy Torah.”

“What are the names of the five books?”

“Bereshit, Shemot, Vayikra, Bamidbar, Devarim.”

“Which of the books do you learn now?”

“I learn Chumash Vayikra.”

“What does it mean, Vayikra?”

“Vayikra means “He called.”

“Who called? The Shames [synagogue attendant] called the Jews to the synagogue?”

“No, God called our teacher Moses and gave him the commandments of the Torah.”

This conversation was enjoyed by all present, and was followed by stormy applause. The children received honey-cake, candy and sweet drinks. The adults sat around the table and ate the “third meal” of the Sabbath; they ate cholent and kugel and drank brandy “lechayim” – a toast in honor of the child, wishing him to become a great Torah scholar in the future.

Besides the chumash the children learned also the prayer Mode Ani, and the “Four Questions” of the Passover Seder. On Fridays they learned to recite the Sabbath Kiddush [blessing over the wine]. This was about all the children learned with the “young children melamed” in the cheder. But as a matter of fact, the first foundation of the Jewish education was laid between those walls.

For various economic and social reasons, a large number of the Jewish children had to be content with what they managed to learn from this melamed.

[Page 74]

My teachers in Căpreşti

by Leah Kolker (Faliks)

Translated by Sara Mages

I've learned from all my teachers, but I've learned more from my parents: from my father, Zalman Faliks, who was a scholar, I inherited the desire to know like him – I also loved to study.

I had many teachers. I took advantage of each opportunity given to me, and every teacher contributed his contribution to what I know today. I remember all my teachers, but I'll never forget my first three teachers in Căpreşti, and I'll write at length about them.

When I was five, according to my father's opinion, I was old enough to start school. At that time three teachers: Lioba Rozmer, Eliezer Cesis and Noah Sofer (the slaughterer's son) got organized and opened kind of a private school. Lioba Rozmer taught Russian, Cesis taught the Hebrew language and the Bible, and Noah Sofer – arithmetic.

Out of the three teachers the teacher, Cesis, excelled the most in his pedagogical skills. If today many of Cesis' students are fluent in the Hebrew language, it's only thanks to this teacher.

When my family moved to Odessa I met Cesis there. At that time he studied in Rabnizki's Teachers Seminary. Cesis also continued to teach me in Odessa and prepared me for the entrance exams to the Hebrew Gymnasium. Cesis returned home when Romania took over Bessarabia. When my family returned from Odessa I found Cesis as a teacher at the Hebrew Gymnasium in Belz where I studied.

Cesis immigrated to Israel at the end of the 1930s. When I immigrated, I found Cesis as a school principal in Tiv'on and we renewed our friendship. This relationship lasted to his last day. He passed away fifteen years ago.

I haven't met Lioba Rozmer and Noah Sofer again. I clearly remember Lioba as a wise, vigorous and witty woman. She always smiled and inspired her students.

If any of my teachers is still alive, I wish him a long life to 120, and if not, may their memory be blessed for eternity.

A Gymnasium [High–School] for sale

by Leib Kuperstein

Translated by Sara Mages

On the fate of “Tarbut” Hebrew Gymnasium, which existed in Căpreşti for only one year (1919), we find in Marculesti Yizkor Book (page 216), in the article written by Leib Koperstain.

– – – The movement for the establishment of Hebrew Gymnasiums encompassed all Bessarabia, and among others also in the communities: Bălţi, Soroca, Căpreşti and Teleneşti. It's also possible to say, that the movement for the establishment of secondary schools preceded the establishment of primary schools.

– – – Indeed, a Hebrew Gymnasium was established in nearby Căpreşti by a group of local Zionists. The principle – one Polinkovskiy – brought all the equipment to the place. Furniture were arranged, special school benches (“Parti” in Russian), blackboards, library, maps, globes, and even physics and chemistry instruments. But soon they realized that the investment was in vain because there was insufficient response from the parents, or not enough resources or organizational skills. Either way, with all the meticulous organization the same Polinkovskiy was helpless. Then he discovered that the group, which was organized in Marculesti, jumped at the bargain. The rumor knew to tell in town, that the group purchased the gymnasium with its inventory, and especially – the government official license for the legal existence of the school. Thereby, it was told at that time, they outsmarted the authorities.

[Page 75]

Since the meaning of the purchase was the transfer of the school from place to place – from Căpreşti to Marculesti – they didn't need a special license. The enthusiastic shoppers, the representatives of the committee, packed all the items and brought them in wagons to the town. – – – Indeed, the name Căpreşti was used to obtain a license for the establishment of the gymnasium in Marculesti.

Exiles to a place of study

by Mordechai Rishpi (Feierman)

Translated by Sara Mages

A. Adventure in the mud

When “Tarbut” Gymnasium closed in Căpreşti the “friendship has come to its end” – children were sent to study in schools in other cities by various considerations: one of them was the fact that the children were able to stay with relatives. After all, we're talking about children aged 10–11.

So, since one of my father's relatives lived in Soroca, it was decided that I would travel to study in this city. The nature of the school was decided by my hosts only after my arrival to the city, a few days before the beginning of the school year.

It was the day after Rosh Hashanah. At an early hour in the morning a cart drawn by two horses stopped by our house. Two girls were already sitting in the cart (I think that one of them came from the Slashtesen family). They were wrapped in big coats and their faces were covered with scarves. Among the boys were – Moshe Hoichman and Aharon Kaiserman. One was equipped with a big triangle and a T–square, and the second held a violin case in his arms.

Meanwhile, the sky darkened and rain, which became stronger as we progressed, began to fall. We sat without uttering a word, curled up in our coats and watched the carter's back with sadness. He whipped his horses constantly, but it didn't help because black mud stuck to the wheels and the cart moved slowly despite the carter's shouts and curses.

Up the mountain, close to Soroca, we got off the cart to lighten the load and to “give a hand.” Finally, we reached the top of the mountain and from there we saw lights twinkling through the thick fog which covered the Dniester River and its surroundings.

– “Thank God, we're getting close to the city of Soroca” – said the carter. We climbed on the wagon full of joy, and I already imagined my entry to a warm house full of lights where I would be able to eat and curl up in bed after we traveled a distance of 50km in eight long hours.

Suddenly, it's not known how, when the carter wanted to turn to the side to avoid a collision with a carriage drawn by three horses, our wagon overturned and we fell into thin paste of mud.

We remained lying in the mud, unable to move, until the carter – the only one who managed to get out of the cart on time – reached out to each of us. He helped us get up and led us to a higher place, far away from the swamp.

It's unknown from where two guys carrying lanterns suddenly appeared. They offered their help and invited us to come with them to their friends' house. While walking, each of us remembered his belongings: one was looking for his violin, the second for his drafting board, and the others for their suitcases. Everything will be fine! We guarantee it! – said the men who looked to us at that time like angels from heaven. However, when we entered a large empty room, we learned that we fell into a trap. The men emptied our pockets, took our watches, suitcases and coats.

[Page 76]

For the sake of truth, they helped to raise the cart, lent a hand to get us on the cart, ordered the carter to get out of town, and if he will tell something – alas to his life…

When we arrived to the hotel we looked at each other and burst out laughing. The hotel employees, who heard our laughter, gathered around us and joined the laughter. In the following years, when we, the participants of this journey met, we described the ridiculous appearance of each of us. On Purim, when we tried to disguise ourselves, we weren't able to equally divide our faces half black and half – white…

B. Adventure in the snow

One of the problems that troubled the students from Căpreşti, who studied in the big city far away from home, was, without a doubt, the problem: how to travel home for the Christmas holiday without losing days in search of means of transportation? To travel by train – was unthinkable, because one day of snow was enough to stop the movement of trains in Romania, and be stuck halfway in an unheated car – seemed like a “pleasure” that didn't rejoice the heart…

So, what should we do to get home quickly? We, the Carpestians who studied in Kishinev, went in pairs, every day after school, to the hotels and hostels where the merchants from Căpreşti used to stay. Usually, every business owner who sold his goods or purchased merchandise – used to stay at the same hotel. But, go guess: who will come in the week that we need a ride home?

This year, after we've learned from the experience of the previous year when we burst into tears when we learned that a carter left for Căpreşti with a completely empty cart fifteen minutes before we got to the hostel, we adopted a new method. We wrote our parents and asked them to arrange the matter in town. And indeed, we received a message that we should be ready with our belongings on a certain day so, Berl “Zitzer” (a nickname for a trader who sells his goods in the market), wouldn't have to wait. Berl sold fruit, vegetables and also fish for the Sabbath. Berl transported his fish – live in the summer and frozen in the winter – in his “Pogron” (a cart with low sides and high wheels – intended for the transport of cargo). Under the agreement with him, the back of the “Pogron” will be loaded with frozen fish and the front will be available for the transport of the students.

Since the three of us, my sister Bety, brother Yisrael and I were fifty percent of the passengers, Berl came to our residence and we showed him the way to the others. Snow began to fall before we left the city, and what's worse – a priest crossed the street. “When a pries passes in front of you – claims Berl – it's a bad sign – to all opinions.” Even though Berl hurried and threw a straw in the direction of the priest – a talisman to annul the decree – he felt that the day “wouldn't work for him.׆

Half an hour later we realized that Berl's feeling didn't mislead him. The cart's front axle suddenly broke on the road to Orhei. In an instant we managed to see how the front wheel kept rolling forward, and at the same moment, we were thrown into a deep pile of snow along the road. Berl stands, checks the cart which tends to its side, makes sure that the fish didn't scatter and scratching his head. “Tough luck, I had a feeling that something would happen today.” Lucky, no one was hurt. A disaster could have happened if the cart overturned on the road. On the Sabbath it would be necessary to bless “Birkat HaGomel.”

[Page 77]

In any case, it was necessary to arrange things. Since I was the oldest child he helped me to arrange the younger travelers in the most convenient way. We arranged the crates in the shape of the Hebrew letter “Chiet,” and the blankets, which were sent by the parents, served as cover and protection from the cold wind. Berl untied one of his horses, gave me instructions on how to guard the property and the children, and rode to nearby Orhei to bring a cart to transfer the passengers to their destination. It was especially important for him that the load of fish will reach the town in time for market day. “The housewives have been waiting impatiently to buy fish for the Sabbath”…

The truth to be told: my situation wasn't to be envied… In order to keep an eye on the cart and the children at the same time I had to stand on the road where a cold wind, which pinched the nose and cheeks, blew from all sides. From time to time I sank inside the deep pile of snow on the roadside, but the cries of one child or another that he was cold – took me out of my temporary hiding place. In the afternoon a sled appeared with two Jews from one of the nearby villages. They agreed to take my sister and the other girl with them so they wouldn't freeze from the cold. Out of joy that the girls will be taken to a safe place, I forgot to ask the men for their names and to where they were taking the girls. When I remembered my mistake, the sled was already far away.

A short time later two other children were taken to a nearby village, and shortly after my brother Yisrael also left. I stayed to keep an eye on the property. Berl returned in the evening with a carter who had a similar “Pogron.” They tied the two “Pogrons” together and supported the side with the missing wheel with a pole. I helped to load the crates and the blankets and the “rebellious” wheel was also loaded.

We arrived to Yoel Mezinzeren's inn in a heavy snow storm. Even Berl and his friend, both very experienced carters, lost their way. We managed to arrive to the inn only after they let the horses to lead us by their senses. The snow storm increased every hour that passed and from time to time there was a knock on the door. Those were passersby who lost their way and reached the inn half frozen, tired and hungry. The owner of the inn received them graciously: helped them to take off their coats that were laden with snow, and added firewood to the two ovens. “If the merchants and the carters, who travel on this road frequently, weren't able to find the way – it means that hell has taken over the world.”

– “Reb Yoel – said one of the merchants – if I was saved from certain death – let's celebrate lavishly. I donate half a bucket of the best sunflower oil.”

– “And I – said the second – I donate a crate full of fish, and if it's not enough – I'll add more and more.” The third jumped immediately and brought a small barrel of “Extra” wine, and the fourth – brought a sausage “from the land of sausages.” Reb Yoel, his wife and daughter rolled up their sleeves and also the guests also didn't sit idle. A short time later there was a proper meal to which I was also invited.

The feast lasted until late at night, until everyone fell asleep. The next morning the storm subsided, the guests scattered and everyone traveled to his destination.

[Page 78]

As we got closer our town I saw from afar our white mare as it was getting closer to us. My father and uncle who, “didn't get a wink of sleep all night from worry,” sat in our sled. Immediately after the cessation of the snowstorm, they went out to look for the missing children. The joy of the meeting was mixed with sadness and surprise that I didn't know to where my brothers, sister and the rest of the children were taken. Fortunately, we didn't travel far. In the first crossroads we met the carts that returned the lost children.

Interestingly, years after this event, each time we met Berl Zitze he told hair–raising stories about what had happened to us on that journey: how we were saved from a band of wolves, deep hole and evil spirits. What saved us was the talisman that we received from the rabbi, Rabbi Moshe–Dovid'l, may the memory of the righteous be of a blessing.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Căpreşti, Moldova

Căpreşti, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 24 Oct 2015 by MGH