In memory of Michael

(Buchach, Ukraine)

49°05'/ 25°24'

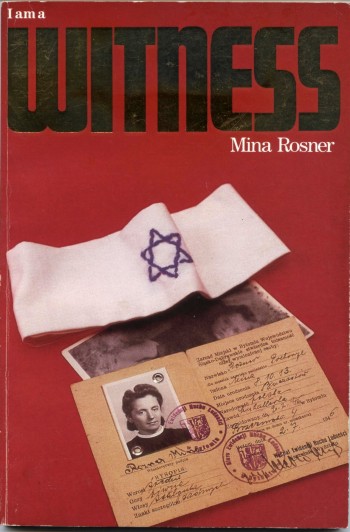

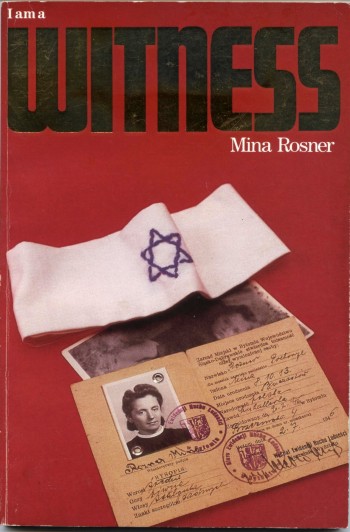

by Mina Rosner

Our sincere appreciation to Avrum and Cecil Rosner for presenting

their late mother's memoir for inclusion in the JewishGen Yizkor Book web site.

|

In the space of three years, every member of my immediate family was wiped out by the forces of Adolf Hitler and his collaborators. My aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters, even my parents, were dragged from their homes and hiding places, bludgeoned, shot, or gassed, then dumped into unmarked graves. No headstones mark the spots where they rest. All that remains of their lives are some crumbling photos and the memories that survived along with me. More than a generation has passed since the end of the Second World War. Today young people must rely on books and films if they hope to understand that period. To many, the war is only an historical event that came and went. The media are even fond of publicizing debates between historians and those who deny that the holocaust ever took place. For me, however, the events of that terrible time are indelibly burned into my memory and consciousness. Recently I returned to my home village of Buczacz with my youngest son. The mayor welcomed me and escorted me on a tour of the town. As we walked up the slope to where my parents had lived, the curious town residents peered out of their windows. The younger ones must have been perplexed by it all, but I think the older ones knew well what I was feeling. The home my parents lived in is gone, so is the store that Michael, my husband, and I ran for so short a time. One of our stops on the return visit was Fedor Hill, the town' s main Christian cemetery, where so many of my people had been taken and shot. Even today, it' s not uncommon for grave diggers to uncover unidentified human remains whenever they prepare a new burial spot. It is a constant reminder of the atrocities of the war. In sharp contrast to the neatly arranged rows of graves on Fedor Hill are the abandoned tombstones in the derelict Jewish cemetery across town. It was difficult for me to control my emotions as I walked alongside the graves of my friends and relatives after an absence of so many years. Some parts of the cemetery are now converted to a garbage dump, while others are completely covered over by trees and weeds. I noticed evidence of human remains everywhere. Human bones were strewn about above ground. Some graves were actually open. This is where my parents met their fate, but there are no markers signifying the spot. A marker erected in memory of the victims of the war was destroyed long ago by anti-Semites. We found the tombstone of my grandmother, Golde Schwebel, who died in 1926. Two graves over we had buried Uncle Karl, and right next to him was the unmarked grave of my son, Isaac. I stood there for a long time. Nearly fifty years after burying my first son here, I was in the same place again, with my youngest son. Hitler did not succeed in killing me, but his handiwork still causes pain for me and millions of others. As we walked on I saw a group of elderly women tending a field, and I couldn' t help wondering, was it one of those women who handed my family over to the Nazis? This thought had been in the back of my mind since I had returned to Buczacz. The people who watched us on the streets, the ones who looked at us through their window shutters, what did they do during the Nazi occupation? Were some of the collaborators who helped to kill my family still walking the streets of Buczacz? Every town and village had collaborators. I felt sure some of them were there still. There were some special places I wanted to visit. One was the monument in honour of the Warsaw Ghetto heroes. Michael and I had visited the huge granite structure before we came to Canada, and now I wanted to go there one last time with my son. It was overcast and raining lightly when we arrived at Anielewicz and Zamenhof Streets in Warsaw, the site of the monument. This is where the first fusillade was fired on April 19, 1943, signalling the start of forty-two days of heroic resistance against the Nazis by the ghetto fighters. Hitler had imported tons of black granite from Sweden to erect a victory monument amidst the rubble of Warsaw. But the Nazis never got the chance to celebrate such a victory. Instead, the granite was used to build the imposing monument which paid tribute to the men and women who took up arms against their oppressors. As I placed a bouquet of flowers at the foot of the monument, an elderly man passed by and spoke to us in Yiddish. His name was Rubin Moscovitch, one of the few surviving Jews in Warsaw. Originally from Lodz, he told us he had lived in Warsaw when the Nazis invaded. His entire family had been wiped out, but he survived by hiding in the woods. He told us the story of the ghetto, and pointed out the spot where resistance leader Mordechai Anielewicz committed suicide in his bunker headquarters rather than surrender to the Nazis. He warned of the dangerous political situation that was now developing in Poland and Eastern Europe, where scapegoats were being sought for the difficult conditions people were having to endure. Poland, he said, was beginning to see a new phenomenon — anti-Semitism without Jews. As I looked at his pale and gaunt figure, with the towering granite structure serving as a backdrop, I thought about the variety of heroes the war had produced. There were the visionary men and women who foresaw the danger of fascism and fought against it relentlessly, not just during the war but before and afterwards as well. There were the brave individuals in every region who emerged as the leaders of the resistance, struggling to make life as difficult as possible for the Nazis at every turn. There were the ordinary people who had no desire other than to live normal lives, and who picked up arms to defend their families. And there were those who had no guns, but whose hatred of Nazism and spirit of defiance were no less real. They struck a blow against fascism by surviving. They continue that struggle now by speaking out against oppression. Another name for those heroes is “ witness,” people who speak the truth. As I looked at Rubin Moscovitch' s face I saw just such a witness. Perhaps he looked back at mine and saw another. Although the events I recount in this book took place half a century ago, I feel compelled to speak about them now because of some recent occurrences. Increasingly, acts of intolerance and prejudice are brought to my attention. These have stirred an urgent desire in me to try to make people understand the consequences of hate. I have no desire to see the events I experienced in the past be repeated to destroy the lives of my children and grandchildren. If we aren' t prepared to learn the lessons of history — to combat racism, fascism, and all forms of discrimination — there is no guarantee that another holocaust will not occur. For Nazism was not the product of a handful of madmen who came to power accidentally. It was a conscious and deliberate policy instituted by those who sought to manipulate and control. As long as we live in a world where the exploitation of others is allowed to happen, people will be persecuted because of religious beliefs, skin colour, or race. Examples of this kind of persecution exist today, and I am saddened by them. The Nazi holocaust touched me directly. I know that such inhuman atrocities can happen. Somehow I lived through that time. But it must never happen again, If my story encourages people to speak out against injustice wherever it occurs, I will be content. This is my small contribution to life — and liberty. |

| Mina Rosner z”l |

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Buchach, at Kehilalinks

Buchach, at Kehilalinks

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 15 Nov 2020 by LA