|

|

|

[Page 171]

by Michael Tcherkis

Translated by Pamela Russ

Once there was, and still is, the town of Briceni, but of today's Briceni there's nothing to talk about: “Al tistakel be'kankan”– is the Talmudic expression – “elo ba'meh se'yesh bo.” Do not look at the bottle, but look at what's going on inside. Today's Briceni does not own any Bricenis, and without them, it is not Briceni.

With this memorial of Briceni from the past, I dedicate my memories as a monument and tombstone for the brothers and sisters, friends and relatives, friends and acquaintances, that the Nazi enemies – may their names be erased – tortured and wiped out without mercy. May their (the victims') memories be blessed forever.

In the center of the Khotyn circle – between the Prut and Dniester rivers that bordered Romania and Russia, surrounded by forests, flowing rivers, gardens and meadows, and neighboring villages populated with Wallachs and Ruthenes (we called them goyim [non–Jews]), there was my little town of Briceni.

I don't know whether anyone has written about it or praised it, or how her establishment was described, but in at least several geography books Briceni is associated with the Lopatnik River that snaked alongside her. It is possible that the elders of the town knew the town from her start, or knew her builders and founders. Unfortunately, they no longer are among the living and there's no one to ask.

My memories go up to about 25 years, from my early childhood until my departure – not many changes took place in Briceni's external appearance. A house appeared here and there, or they fixed up the face of the house, many times out of need to prevent a collapse, or even after a fire. In general, the city remained the same for as long as I can remember back, and even today I remember her with great reverence, and long for the youthful, golden years.

[Page 174]

Briceni was open to the winds on all four sides, and three bridges connected her to near and far surroundings.

The Rymkowicz bridge, which years ago was used as a passageway to get to the train station, a distance of about 20 kilometers, goes through the towns of Rymkowicz, Iwoskewicz, and Romankowicz. Only later did they make the station closer, and the train was only about two hours from Briceni. The groups of wagon drivers traveled these highways with equipped carriages that used three or four harnessed horses, and took seven or eight passengers and their baggage. I can still hear the sounds of the bells in the summer nights that announced the arrival of guest and the departures of loved ones. Many times these bells were used to indicate time. The road wound around fields and forests. In summertime, the horses raised a heavy dust, in the winter they would get mired in the deep muds. For years this highway connected us to these cities – Kishinev, Odessa, Mahilev, and Kamenetz–Podolsk in the times of Czarist Russia (until 1916–1917), and with Czernowicz, Bucharest, and Jassy, in the times when Romania ruled.

On the south side – was the Lipcani bridge, which tied us to Lipcan, Nowoselicz. During the wartime of 1914–17, they paved a road that tied us via automobile traffic with Czernowicz. From that side the road also went to the Sankauzer mill and to the whisky factory that was located at the source point of the Dadeles River. Opposite that, was a forested mountain with a beautiful panorama of the valley (gorke) that snaked around the base of the river. Here, romantic couples would lose themselves, and there the Romanian powers would celebrate the national Romanian holiday – May 10.

On the eastern side – the Yedinets bridge, that led to the city of the same name and also to Sekurian and to the cemetery. There were Jewish wagon drivers whose route was especially to these two cities: Mordechai Kandri, to Jedenecz, and to Sekurian was the well–known joker wagon driver who became beloved for his clever words, jokes, and moving stories. When he would leave Briceni, he would turn his seat around to face his passengers, leaving the horses to clatter independently, and with a joyful conversation about politics, community issues, events and curiosities, with cleverness and wit, he would occupy the passengers so that they would not even be aware of the passing time.

In the earlier years, the merchants would travel this road to get the train to ...

[Page 175]

… Oknice, and there was a real danger on this road because there were highway robbers here. By setting up the station in Waskocz, the road was used only for the two neighboring cities and for the cemetery.

Behind the Yedinets bridge, flowed the river that brought water to the Dadeles River, and the entire year, it flowed quietly and calmly. But in spring, after the frequent and strong rains and the winter thaw, the water would be turbulent. The little river overflowed and became a brazen flow that raised itself above the shores, endangering the nearby houses that were at a significant height over the shores, and much damage was done.

On the west side – there were two entry points to the city: from the district town of Khotyn and the surrounding villages, and it was also for strolling in the surrounding woods.

This side of the city was higher up and the angle was sharp, and it ran the entire length of the main street, until Uzh to the Yedinets bridge.

The finest houses stood on these streets, exclusively on the upper part. Here they built high walls that were appropriate for even a large city. There was also the post office from which the name of the street was taken, “Potchtowa.” The Romanians named this street after King Ferdinand, the father of King Carl, but the residents knew this street by no name other than “Potchtowa Street.” The western half of this street was used for the Shabbos evening stroll. At that time the street was filled with well–dressed youths and grownups, crowded in such a way that it was difficult to pass through. The non–Jews would stroll in this area on Sundays, on the other sidewalk.

The three main streets – Potchtowa, Rymkowicz, and Bucovina – were finished on both sides with stone sidewalks. I remember in the years of the First World War, the streets were partially finished with wooden sidewalks, and some without sidewalks. Slowly, they laid down slabs of stone for sidewalks. In the eastern part, that goes to the Yedinets bridge, the wooden planks on the footpaths remained – for many years.

The road was paved with limestone, but the heavy wagons would grind them and make ditches into which they would sink with the winter rains as the ditches filled with mud. From time to time, they would fix the road, but they never completely got rid of the ditches, and they became a part of the Briceni “panorama.”

[Page 176]

I remember a time when the entire length of the street was filled with wood chips, painted black and white to prevent the wagons from going onto the sidewalks. But with time, these disappeared almost completely, except near the large pharmacy of the Fineberg family, where they remained for a long time and “Boris” fussed with them, fixed them, and painted them.

Most of the other streets were without sidewalks, or had loosely placed boards about 40 centimetres wide (Balnicne Street, Berl–Yosef Itzik's, and the streets of Khotyn).

In the summertime, they would sweep the dusty streets and fill all the various ditches with the dirt or remove it from the city. On rainy days, the riding would bring in mud, especially on the busy days (every Tuesday). At the beginning of spring, the government required that the mud be collected and removed far from the center of the settlement. This speeded up the drying process.

We were blessed with three meadows, each overgrown with grass all summer. These were used for grazing for the flocks and for strolling during the Shabbos afternoon hours. On the other side of the river and on the shores of the Dadeles' wide, glassy waters, stretched the meadow bridge. This was the largest one and occupied a large area, between the waters and the mountains on the eastern side of the city. Also, the mountains were covered with nature's greenery. In addition to that, the residents used this “Potchtowa” mountain that boasted its natural appearance, with its fine, fresh air, and children would love to come there and play and roll down the mountain. During the winter, the children would snatch a fun slide down the mountain with sleds and ice skates. Some called these meadow villages the mountain meadow.

On these hills, it was mostly the local flocks that grazed, cows and calves, goats, and horses. The Dadeles River contributed greatly to socializing, by attracting swimmers during the summer days. About this river it was said that every summer it needed a “sacrifice” especially during the “Nine Days.” [1] Truthfully, there were many drownings in this river, and even many young and good swimmers drowned there.

The river was tricky because in the area of the whisky factory, the river was barred by a pond that regulated its flow. A landowner rented this area to a group of Jewish fishermen that prepared carp every Shabbos and Yom Tov for the Jewish residents.

[Page 177]

The next in size was the “fire” meadow, because the community fire station was located in the southern corner. In my childhood, the wheat fields grew on it, and separated it with a trench (ditch) raised on one side. Once the city's building area was extended (the so–called “New Plan”), the fields moved far, far back, almost invisible to the eye. On Shabbos and Yom Tov crowds of strolling people would pass through here. Not far from here was also an area for an animal park. With time, that too was moved to the western side.

The third – the “church” meadow, surrounded by the church with non–Jewish houses and fences and a non–Jewish cemetery, and cut across by paths that was bordered by a long row of tall acacia trees. In the middle of this row was a well. The area was really unfriendly. There were few strolling people here, but the area wasn't abandoned completely. Here, people came to cool down their bodies and absorb the fresh, pure air into their young, Jewish lungs.

Briceni was blessed with two hospitals: the government hospital and the Jewish hospital. The government institution was first supported by the Russians and then after 1918 by the Romanian government. The buildings, tall and strongly constructed, white from limestone, were all surrounded by tall, green trees and flowers. The inner setup: a corridor system, wide rooms painted white, and large windows through which a lot of air and light streamed. It all made a very positive impression, a calm environment and a reverence for the institution. Dr. Tunik attended exceptionally well to the sick. In our town we considered him to be an excellent doctor and someone who demonstrated a refined approach to everyone – both Jewish and non–Jewish. In general, there was the spirit of the Christian influence in each corner of the hospital, even with the staff, but even so, there was no bad behavior towards the Jews.

The Jewish hospital was found on the north side, in the Jewish section of the settlement. The Jewish community supported it and sometimes from monies that were received for the cause by Briceni residents and foreigners. The majority of those who came here were the sick who didn't want to go to the non–Jewish hospital because of the issue of kosher food. Also, there were good doctors here: Hokhman, Schwartzman, Shur, Glayzer, Trachtenbroit, Grupenmakher, and so on.

Nearby was the hospital park where the sick were able to…

[Page 178]

… rest in the shade of the dense trees. From time to time, the hospital found itself in economic hardships that resulted in a decrease of medical help, or a reduction in the number of beds. Around 1923, 1924, a committee from the community, with the support of the Jewish community, opened the park to the entire settlement, and set it up for strolling, events, etc.

The volunteer firemen brigade was one of the most important institutions. This also evolved in all kinds of stages, according to her organizers who stood by her direction and according to the doers that were at her helm.

I remember well the years 1912–1922, how the youth of that time registered en masse in the rows of firemen, and how this changed so that in a short time they upgraded their status. They instituted a uniform, ordered shiny, mesh helmets, axes and hammers, got several new fire extinguishers, ladders, water tanks, etc. An instructor did field exercises with them, did practice and theory of fire extinguishing with them. They also tried to get a music section, and it was festive! That was life!

The large bell that was located on the roof of the pharmacy building was transported to the fire station (later this bell was hung on a tall pole in the center of town). At the head of command was Yekhiel Segal who served the institution with great devotion for many years. He was very active, and instituted several demonstrated marches and exercises. The institution was pulsing with life, and attracted the interest of the city and of the youth.

Also his son Moishe, when he grew up, helped him very much. Even in later years, they both remained loyal to the institution, when it became weakened, abandoned, and forgotten.

In the years 1924–26, in the yard – the fenced in area around the fire station – they built up a large promenade area (park) and planted trees, flowers and greenery, put in benches, shaded corners, and special gardens.

When a fire broke out, the bell would announce it with a metal clang, and help would come immediately. Danger would always hang over their heads because the roofs were all made of wood, shingles, or straw. The fire bell often accompanied the church bells and the firemen …

[Page 179]

… were assisted by the water conduits, along with the residents, and they controlled the destructions of the fires and saved possessions from the flames.

The Dadales River was not the only place that one could bathe in running water. The small river Palatnik, that snaked around the east side of the settlement, at the foot of the mountains on the road to Yedinets and Sekurian, had its source far, far away, and it nourished itself with well water at the foot of the mountains. Its snaking was capricious and zigzag. Not far from the city, the water flowed on a hard bath of rocks full of ditches that created bathtubs of sorts. In the hot summer afternoons, youth of both genders came here, people of middle age, and also elderly men and women. Every type had his or her own spot, and that's how one refreshed one's body – scrubbed and creamed oneself in the flowing waters with great pleasure.

The majority of the streets were straight, more or less planned, even in the smaller streets and in the alleys. True, some of the streets stretched very far, like a long shir hamalos (prayer before grace after meals), but in general it had the planning of a big city, according to the setup, and was divided into four sections. If only they could find the planning engineers, and especially some local money sources, Briceni could have evolved into a modern, well–run, and comfortably built city.

The houses were built without any particular system or any particular style. With time, the straw roofs that I remembered here and there disappeared, and in their place came shingles, or painted tin roofs. Only the non–Jewish houses in the far corners were still covered with straw.

Most of the houses were one level, with an angled roof and a gutter for the rain water. That's how the houses were built, without having to work with special engineers and without special plans. You called a neighbor or an acquaintance who was generally familiar with building issues, discussed things with him, ordered builders and materials, and in a short time the house just sprouted up.

The rooms were built from fresh, sun–dried lime or earthen bricks, or from a molded grating through which twigs were braided, and fresh earth was tossed over this, or damp lime mixed with manure that was kneaded in the middle of the street with bare feet or with the help of a horse. Only the more fortunate were …

[Page 180]

|

|

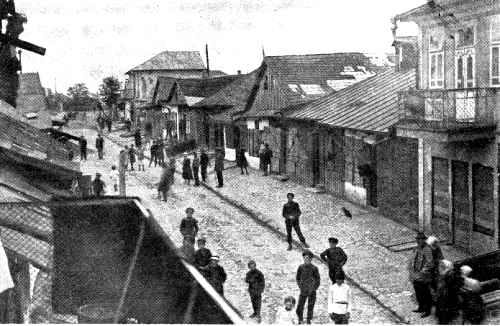

| Ramakowicz Street |

… able to build their houses from baked bricks, that made the building more expensive. That's why only certain individuals could do this. From inside and from outside they put a layer of plaster or smooth coating on the wall, and then whitewashed it.

In order to have a fine appearance, some of the homes were built higher up with steps in the front and with a balcony; that's how these houses stood side by side, beautifully polished, while nearby, on both sides or directly across, were small and low, old little houses that had lost their initial facade long ago. Directly in the actual noisy center of town, where the majority of stores were located (on part of the main street and Bukowina and Ramakowicz streets) barracks made of wooden boards were still standing, seeming that the wind could easily knock them over… actually, many of them were destroyed by fire, and because of that many two–story houses were built nearby, beautifully constructed, painted, and with iron balconies and sliding windows. In this part of the city, the houses stood tightly together, one near the other, without any …

[Page 181]

… space between them, scores of houses under one roof. Air, sunshine, and light came in through individual “sky windows” (skylights).

Just about each house had a cellar which one could climb down into from stairs on the street, going through two swinging gates onto a set of stairs or a ladder. The cellar was dug out deep in the ground, and because of that it maintained a cool temperature and was somewhat damp. As a result, the cellar kept the food products (greens, fish, meat, dairy, etc.) fresh. In some places they had “ice cellars” (lyodovnyes) which held huge blocks of ice in winter – blocks that were broken off from the ice in the river. In the cellar, they were covered with fresh straw and with an additional rooftop–like thick layer of straw. The ice maintained itself like this until late in the summer and then it was distributed to various institutions: hospitals, soda factories, etc.

On both sides of the sidewalk, there were tall poles every 100 meters – holding the telephone and telegraph wires. The main telephone station was in the post–office building. From there …

|

|

| The main street in the center of town, Pochtowa Street (Post Office Street) |

[Page 182] … the telephone and telegraph wires were carried to the neighboring cities and towns. There was no thought of these types of luxuries in private homes. Only later, did two partners – Ben–Zion Kaufman and Yosef Kaufman – bring in telephones. The Jews really had what to laugh over and joke about on their account.

Around 1922, poles appeared that were strong and tall, with black feet, and from which they began to draw thick, copper wires. The secret was quickly revealed – they were going to establish an electricity center in town.

And in fact, very soon the streets were lit up with electric lights, and the kerosene lamps disappeared entirely. That's also how they lit up several display windows that advertised beautiful wares; this civilizing process brought us – a movie house. The center was built in the well–known Babanczyk court by someone named Frymczis who was from Mohilew–Podolsk. For a few years, some of the kerosene lamps burned along with the electric lamps, but slowly the electric wires spread also to the side streets, and modernization was felt in all corners.

But a water line did not yet make its way into the houses.

The water sources were the wells, strewn in different parts of the city, and from them, in a very primitive manner, people drew their water. Other than for minimal needs, the team of water–carriers provided the town with fresh well water drawn from the Izwor River and transported in barrels on two–wheeled, horse–drawn wagons. For individual use, there were these wooden buckets, and the water carriers were paid by the week or by the month. Aside from this, sometimes one had to buy extra water, according to the needs of the household.

At this time, I would like to describe how we dug up a spring. This was the type of work the Jews did not do, even though the contractor could have been a Jew. This job required a strong body, strong back, developed muscles, in order to dig in the heavy or wet lime pools that were later dredged in large buckets from the hole, and poured out around the hole that was to be the well. The depth of the well was made according to the how deep the water sources were. At times, the depth could have reached scores of meters, and sometimes even deeper than three consecutive digits.

[Page 183]

The drainage of the excess household water was of little interest to those who were not affected by it. In order to get rid of the unnecessary water on an ordinary Monday or Wednesday – they poured out the water quite simply and regularly on the street, and the sun and the wind dried it up. On rainy days or in winter time it was generally not a problem: The loads of water or snow all got carried out to the sea.

Because the population was urbanized, they rarely busied themselves with greenery, flowers, trees, or other gardening. The greenery “moved away” from the business neighborhood, and even from the quieter sections of the city, and seldom did a tree or a bush adorn the appearance of a building there; at most, the tree grew by itself, just as God created it … straight or crooked, no on touched it and no one bothered it. There were few trees or flowers, also no planning or knowledge of [how to make it work], other than in a few courts (in the old hall, by Hersh Bedrik, etc.).

From my childhood years, I remember that near Khaim Zuker's house there was a three cornered area that was enclosed by a wooden, green fence. The area itself was green with grass and trees, and in the middle there was a sort of monument with a shield which had an inscription on it in Russian.

In a few side streets in the second row, streets such as on Hospital or Khotin streets, the appearance was better. Here, several houses had trees, bushes, flowers and greens, and even a few fruit trees. Opposite that, in the non–Jewish part of the town, it was full of orchards and gardens, and in the summer time this area provided summer houses for the Jewish population.

Every Tuesday, there was a market day (large crowd); aside from the non–Jewish holidays and Sundays, when the farmers were free of work in the fields and gardens, they would come into the city with their products (greens, eggs, milk, animals, chickens, etc.) to sell them and for the money they made they would buy their necessities.

They came in masses with wagons (and almost each non–Jew had his own set “parking” place), they unhitched their horses, and set them with their heads towards the wagons where they could eat the straw and hay. The farmers, with their wives and children, would bring along their products, and after selling all their wares, would go into a restaurant. There they would drink up a large part of the monies they just earned.

On these market days, the streets were overflowing with wagons and animals, and the farmers in their village dress, would circulate…

[Page 184]

… in the Jewish stores, buy and lease much, bargain and argue, and stubbornly stick to their few kopecks, clap hand to hand, and slowly let go of three kopecks after three kopecks, until they purchased that which they had chosen. In that way, many times did they measure themselves, examine themselves in the portable mirrors, turn themselves around and around, and ask everyone their opinion of the clothing they were wearing, the hat, shoes, or other such things.

Not few arguments, not a little shouting, and many times no little fighting, came about on these days, particularly when the villagers drank a little too much whiskey and argued among themselves in the middle of the restaurant, or just teased a Jew and poured their non–Jewish temper all over him.

Aside from the crowd in the city, which brought liveliness and energy into our lives, outside of the city there was an animal market. Before, the market was in the area of the firemen's field, but with time, this area became too narrow and too close to the residential area, so it was moved to the west side of town, on the road to the Rososhan forest (this was the road that went to the district town – Khotin).

What a noise there was! Human voices, cows and horses, birds and sheep – everything mixed together, making a great tumult. In one corner, they tested the horses, how they walked and how they ran; over there they felt the geese and chickens; there they fixed the wagon wheels; bargained over the prices with voices over voices until they came to an understanding, and after doing this business, both sides understandably concluded the deal in the restaurant with a le'chaim.

Did they need special stores to sell vegetables, fruit, fish, etc.? Briceni could have shown that on wooden boards, haphazardly banged together and that stand on two primitive feet, one could sell all these products and materials just as well as in the most orderly, beautiful stores. The women farmers also didn't need these stores. They spread their materials directly on the ground, not even spreading a cloth underneath, and sat at the edge of the sidewalk and sold everything in mass or in quantities.

On the stands, the least one could put out was a set of scales to weigh the material and give the right measurement…

Those who sat at these stands did not have a good name. They were considered shameful and scandalous people, and those from whom one had to protect himself as if from fire… if you quarreled with them while discussing prices, or touched the product…

[Page 185]

… you could not get out of it. You were forced to buy. And if you tried to get away, and to buy a chair by a neighboring stand, they would drown you from head to toe with all kinds of insults, arguments, and simple humiliations, unless they really didn't have what you wanted.

At a certain distance, there were a few stalls of which one wall or two were covered with shutters or sacks. One drawback for our fellow Jews was that the neighboring stalls were of pigs, and their smells carried very far.

These stalls were built at the edge of the “targowycza,” and there they separated the main road practically into two streets. What is the “targowycza”? [Was something like a food court.] Here there were restaurants next to restaurants, and each one, during the time of the market, was filled with village people. The traffic was enormous: Here were the stalls with fancy goods and cheap things, such as combs, mirrors, hairpins and rings, sewing instruments, beads, all kinds of ornaments, cheap toys, bracelets, chains, and important things such as holy items – that is, crosses and statues.

On one side there was a row of wooden barracks – little stores carrying the basic necessities: salt, dried fish, paint, and parts for harnesses, rope and sacks, wax and all sorts of black paint, tar for the wheels, tobacco and matches, soap, and work tools: scythes, pitchforks, sickles, sharp stones, etc., all basic necessities for the farmer.

In the southeast section, often a carousel was set up – or acrobatic performances, and nearby, were candy stalls. In the other areas, the targowycza stood empty and waited for the exciting market days.

A market day brought in life, and to life, energy and enthusiasm for the entire week, or at least until the next market day.

The grain stores were mainly concentrated in the area of the Yedinets bridge and in a few years' time, they moved to the other side of the bridge, on the road to Sekurian. From there, the grain merchants sent wagons with grains and grains for oil to the oil factories. There were transports across the border and much of this was sent to Israel.

There was a special place that the Jewish community designated for the butchers to sell kosher meat from a kosher slaughter: beef, and lamb and fowl, that means meat from chickens, geese, ducks, and turkeys were bought alive by each homemaker from the farmer women and they bought coals from the shokhet. After that…

[Page 186]

…. they bought a ticket for the slaughtering. The monies went to the taxes that supported the shokhtim.

The butcher shops stood in two rows facing each other, built from wooden boards, painted black, and they stood high up so that you had to climb up some stairs. In the area under these constructs there were groups of dogs that would tear at each other over a bone and make a terrible commotion with their barking. Beef was brought from the city's slaughter house. Lambs and goats were slaughtered in the side courts of the neighboring houses.

There were several families that were meat merchants – butchers for generations. To slaughter birds, each shokhet had his own slaughter house. The shokhtim that I remember: Yekhiel the shokhet (the big one) from Khotin Street; Yekhiel the small one on Berl Yosef Yitzkhok's street; Shmuel, near the Galanzka small synagogue; Leibish, opposite Yossi Pinje (Silber); Itzy, on Rimakowicz.

As far back as I can remember, the government institutions stood in the southeast corner of the food court. The building, though it was not exceptional, not tall, no special fixtures, still evoked from me, as for other Jewish children, a real fear.

Here there were laws passed – civil laws, criminal laws, and many times we would follow the policemen who were dragging a thief – who was under armed guard – to court in chains or to be locked away for a long time. From time to time they would bring thieves or murderers in a procession. These thieves were on the road to spend the night. Here there was always a police guard, a short man in the gendarme unit, may we never need him. Years later, they began to build a new prison on Lipkan Street, opposite the gymnasium. In the time of the Czarist regime, the policeman was the almighty power, and the police sergeant was the supervisor of the town and all the surrounding villages.

The police officer was second to the king, and he used his power to its fullest. His superior was the county representative, but he was far away, in the city district. For us, however, the police sergeant along with the bailiff went deep into our bones.

There were two entertainment halls: the old hall (on Khotin Street), and Matje Kremer's hall. Later on, the Horowicz brothers built a third hall. The old hall was in a …

[Page 187]

… large courtyard with fruit trees that were low, and the approach to these halls was not easy. The windows – narrow, were directly under the ceiling, so that it was difficult for any light to get in.

The stage was a dark one, although it was large enough; the furniture – simple, long benches, were hard and uncomfortable.

The public was not satisfied with this old fashioned setup, and the owner himself was a difficult man. It was hard to come to an agreement with him. So, with time, the hall remained empty.

Therefore, however, Kremer's hall stood on the main street – directly in the center. The decorations here were purposeful, with a gallery, benches in the first five rows, the hall lit with lux lights [kerosene under pressure], and later with electric lighting, separate dressing rooms for men and women, exit doors in four different directions; the properties more or less comfortable. The proprietor and his daughters were refined, quiet, and calm people.

Here they would celebrate weddings and organize cultural, sport, and literary evenings; Theater performances about lovers, or new artwork, literary contests, festivities, political rallies, Zionist undertakings, and gatherings from all sorts of institutions.

With the establishment of the third hall, that was much bigger and was also sitting on the main street, it became easier to organize the culture and social life in the city.

Announcements were made with posters, playbills, and shouting in the streets. Who doesn't remember the crier Yitzkhok Lecz, with his voice ringing even in winter through the double windows. There were other criers that made announcements, but the humorous announcements and the voice of Yitzkhok Lecz outdid all the others.

The gates of Zion opened in the “Shaarei Zion,” the institution of the Zionists in Briceni. It was called a shul, but it was primarily the center for the Zionists. Prayers were held there on Shabbos and Yom Tov. Around 1924, they went into their own building, the Shaarei Zion, a fine, two–story building which also housed the new school, the Talmud Torah, and later it also became the location for the sports group, the Macabees, and other Zionist institutions. Because of this, they prayed in one of the halls, Kremer's, then they bought a house on Hospital Street and ordered furniture – benches and tables – that also served to as study tables…

[Page 188]

… for the students, and was dyed dark brown. For a long time, clothing would stick to the benches and the tables. In the entranceway, there were two small rooms for the shamash (beadle), Yekhezkel, and later for Avrohom–Leib.

For many years, Yitzkhok Feiteles lead the prayers with his beautiful, musical voice and beautiful style of prayers. More Zionists began to visit the Shaarei Zion on Shabbos where some modern traditions were instituted, such as dividing up those who would be called up to the Torah according to an alphabetic list, without arguments, without competition for any part of the ceremony (without arguing for a shlishi or a maftir). There was no “eastern wall” (which every shul has), in general, no seats were sold; and every congregant could sit wherever he wished or where there was an empty place. The service was quiet and calm, discrete, without any extra adornments. Being called up to the Torah – was according to an invitation that the congregants received from the gabbai, before the beginning of the services, according to a pre–established order. None of these privileges were sold to the congregants [“farkoifen aliyas”], except in special situations.

Around 1925, the new Shaarei Zion was completed, with two large rooms on the second floor for the Talmud Torah. The prayer hall was planned with space, galleries, and began to serve for Zionist activities in town and for activities for the Zionist businessmen.

Very soon, the socialist Zionist institutions gathered here, also the youth organizations, Keren Kayemet, and Keren Hayesod for activities, and other similar institutions as well.

I don't know whether anyone is in the circumstance to remember all these details, large and small, or if anyone has the talent or opportunity to give all this over exactly as it was, and how he understood it several decades ago, and if he can build all this anew in its original form.

In these lines, I wanted to share the period of 1910–1926 with my landsleit (people from my town). With him, my landsman, I have bonded together many of my personal experiences from the time that I first began to understand and think earnestly of the times after my childhood years, from my youth until the time that I left my place of birth, when I went to search for Torah and for a skill, in order to prepare for life in Israel – according to my own aspirations and upbringing in my parents' home.

Translator's Footnote

[Page 189]

by Shlomo Lerner

Translated by Pamela Russ

Before I give over my memories, it is worth noting that in October 1906, we – that is, our family – left Briceni, Bessarabia, and immigrated to Argentina where we arrived on December 8. This is so that my memories can reflect a distant period of my adolescence and youthful years.

Of all the surrounding cities, such as Yedinets, Lipkan, Sekurian, and even Khotin, the central city was Briceni that was the most developed. Its center was a fruitful area of grains, more than anything, good wheat, barley, corn, semolina, groats, and so on. Around Briceni, Jews were also occupied with planting, tobacco farms, fruit orchards, etc. Briceni had around it a large area of 19 villages, mainly from the Wallach area, that gave a bountiful livelihood to the city residents. Other than grain merchants, there were also many estate lessees; that means, well–to–do Jews that held leases of princely estates. Usually, with this type of goings on, there was a wonderful, prominent commerce.

Briceni had a two–class Russian government school, two private Russian elementary schools, run by certified Jewish teachers….

|

|

| Shloime Lerner (son of Moishe–Shloime Simkha) Argentina |

[Page 190]

… J. Khantses and Zusia Lerner), many private teachers, many religious schools, among which were a great number of modern, enlightened ones, where they learned – other than Talmud and commentaries (Gemara und Tosefos) also Prophets and Hebrew grammar, which for the other cities was still forbidden and considered non–kosher studies (treif–posul).

Briceni had two large libraries: one a Hebrew one from the group of proponents of the Enlightenment, under the supervision of the famous Maskil (follower of the Enlightenment movement), Avremele Kleinman, and another Russian school, under the supervision of Fraulein Katya Ginsberg, a well–known social democrat. There was a Zemski hospital and a Jewish hospital with 12–15 beds; there were a few community charity funds, supported by the Jewish community organizations. So, Briceni was a city and a mother in the nation of Jews.

Briceni had a youth that studied “in classes,” joyfully took exams outside of classrooms and traveled in the big cities such as Kamenetz–Podolk, Odessa, and even Kiev, taking exams in 4, 6, or even 8 grades in the gymnasium. Briceni did not have any very wealthy people or magnates, other than the old Moishe Bershtayn who was the owner of three estates, two mills, one factory and a refining factory for whisky, and his son–in–law, Hershel Steinberg, that had a banking business. Other well–to–do families, such as the Zilbers, who were occupied with the forest business; and the Broides, the sons of Yosef Yitzkhok, and the son and grandchildren of the old man Bershtayn were occupied with estates; and the children of Duvid Leib were in charge of taxes.

There was no industry in the town, except for the few community industries such as: candle making, cotton making, oil manufacturers, tanners, furriers who would prepare the fur hats and the skins for the village residents, and shoemakers that would have workbenches for working with boots and heavy shoes. But these places did not carry the name of a factory, a manufacturer, or an industry.

Briceni Jews were always on the move – like mercury – as grain merchants, skin merchants, and depositors (transporters) of shipments of eggs and fruit. Because of the proximity of the Romanian and Austrian borders, large transports were sent to the other side of the border. Understandably, there were small merchants and large customers, wholesale merchants; all kinds of brokers for the grain, hides, fruit, and even for maids and servants. Each group had its own section: around the Yedinets, Lipkan, and Romikowicz bridges – grain merchants and their stores; a tailor's street, a furrier's street, and so on.

Every section had its own small shul – a tailor's, a furrier's, a water porter's. In the middle of the center of the city, on Tarhowicz, were …

[Page 191]

… the big shuls. The big shul – a tall, large building, built deep in the ground, so that the prayer “I call to God from the depths” would be true. Opposite is the old kloiz (small shul where like–minded or people of the same profession prayed). On the right side of the big shul – the Bais Medrash; and opposite the Bais Medrash, the Selesh kloiz; up to Khotin Street is the Satanow kloiz; up to the Bershtayns is the Galanski kloiz; the Berl–Yoisef–Yitzkhok kloiz and someone else from the Jewish hospital another large kloiz, that I've already forgotten after whom this was named. There were a total of 14 shuls in Briceni. Each one had his own prayer leader, but in the big shul, the city cantor led the prayers – Moishe Akhler – a heavyset, large Jew, who once had a bass voice, was a real connoisseur of music, and who led a choir. I remember this Reb Moishe Akhler all my years (because of his respect for food).

This is a general picture of my city of birth, Briceni. There I was born, grew up, and raised my children, spent adolescence and boyhood years, but with what did Briceni stand out? With the development and spread of political Zionism. In Briceni, there was already for a long time a group of old Chovevei Zion (Zionism lovers), with which my father, Reb Moishe Lerner, son of Shmuel Shloime Simkha, was not very impressed.

My father was a Jew and a scholar, and was enlightened. In his younger years, he prepared to become a Rav, he swam in the ocean of Talmud, was sharp with the commentaries, Yoreh Deah (from the Talmud), Yad Hakhazaka (a scholarly text written by Maimonides), he studied a lot, immersed himself in complex religious texts, knew by heart almost the entire Guide for the Perplexed (written by Maimonides), Moireh Nevukhei Hazman le–Rav Nakhman Hakohen Krakhmal, the Kuzari, and other texts of the Enlightenment. Understandably, he was now not able to become a Rav… The three Rabbis – Reb Yidele, Reb Hershele, and Reb Daniel, were careful not to decide on a law using my father's instructions. I don't remember ever that the Hatzefira (a Hebrew journal) was not in our home, aside from other Hebrew papers, such as Hamelitz, Hazman, and other monthly publications such as Hashluakh, Hador, and so on. So, I remember that our home was a gathering for smart people. I remember Friday nights in the winter: It's warm in the house. It's alive. On the Shabbos table, between the lit candles, was a lamp with enough oil that it remain lit until late in the night. My father's relatives gather here, and my father, may his memory be blessed, graciously offers to read them an article he wrote and sometimes with an important article in the paper Hasheluakh, Al Parshas Drokhim, and so on. And I…am… “misavek be'ofor ragleihem shel talmidei khakhamim” (stick to the dust of the great scholars).

With the uprising of political Zionism, my father, of blessed memory, did not rest and gave himself over, heart and soul, to this great, bright, holy ideal. I remember: Right after the first [Zionist Organization] congress in Basel, in the fall, my father, of blessed memory, took me with him to …

[Page 192]

… their first meeting that was held at Shloime Berish's house, were the Agudat Hazionit (the Zionist Group) was established. From that time on, there was a lot of activity in our home that served as the center for all the other surrounding towns.

The Agudah did not miss one yom tov or national holiday for the opportunity to hold speeches about Zionism. I remember that one Shavuos my father, of blessed memory, went to the old kloiz and gave a speech that he named after a verse in the Shavuos prayer, [1] and on Pesach (Passover) he gave the speech called “Four Cups in a Drama,” and that's how each yom tov had its theme. And my father had a public reputation – not to sin by saying this … my father, they knew in town that if Moishe Lerner would be speaking in such and such a shul, all the important men from all corners of the town would come to hear him.

Other than my father, of blessed memory, there were others who gave these speeches: Rav Yehuda Bershewski (the Rabbi from Kazjon), Avremele Kleinman, and the fiery Zionist and heartwarming speaker Moishele Rosenblat – he was truly devoted, heart and soul, to the Zionist ideal, also very knowledgeable in Torah studies and Hebrew grammar, had a golden Hebrew speech, a writer and poet, for whom there was nothing too difficult to do for the Zionist cause. The Zionists gave a lot of grief to the old–fashioned Jews, khasidim, and various Rabbis, such as the Sadigurer, Sotanower, Boyaner, Zinkower, and so on. Day and night, there were scuffles and disagreements with them.

I remember: One Shabbos during the day, in the Seleztcher kloiz, a fiery khasid, a fanatic, verbally attacked my father, of blessed memory: “You atheist! You sinner that brings shame on the Jews!” etc. On our way home, it turned out that we took the same route back. The khasid was walking ahead, and we followed behind. I was very angry and called out to my father, of blessed memory: “I'm going to take a rock and throw it at his head!” “No, no!” said my father. “You're not allowed to do that. That Jew is a fanatic and means what he says seriously. He believes that he is sanctifying the Holy Name….” My father, of blessed memory, had tolerance….

When the Zionists in the nearby towns wanted to arouse the people, they would depend on my father, of blessed memory, and we would send him a wagon so that he should come for Shabbos, and for them, these Zionists, it was a great yom tov (holiday).

In the year 1902, the All–Russian Zionist Conference took place in Minsk (albeit this was the first and last conference because after that Zionism became forbidden). My father, of blessed memory, and Avremele Kleinman were the delegates then and my father, of blessed memory, became acquainted with the big names of Russian Zionism.

[Page 193]

In particular, he befriended Rav Frishman (the then Markolesht Rav and the future head of the religious people, Rav Yehuda Leib Maymon), with whom he later corresponded and brought to Briceni for Sukos. Rav Frishman stayed at the home of Aba'leh Broide in his garden house.

Years passed. The revolution in Russia became sharper, and the counter–revolution, stronger… The Black Hundred [2] worked on all fronts. The Kishinev pogrom foreshadowed new persecutions for Jews… I remember the Shavuos after the Kishinev pogrom. The Zionist Agudah set up speakers in all the kloizes, inciting everyone to organize themselves independently (each one for himself). The older Zionists went to the bigger shuls and we, the youth, were sent to the workers' kloizes. I went to the cap makers' kloiz and my father, may he rest in peace, spoke in Berl Yosef Itzik's kloiz (across from that was our home). But in Briceni there was no pogrom; the city was well prepared.

In October 1905, I was standing in front of the draft board. When I was coming back, we found the decree of October 17, proclaiming the “constitution.” All the great things were outlined in the constitution: deputy and senate chambers, religious freedom, general elections, and other wonderful things, but at the end there was an important P.S.: The Czar maintains the right to discharge the chambers if they don't please him. As our Leizer Abales said: Forget the “kontzeputzia,” constitution, with all its thievery…

And so it started. It didn't take long, and soon the Czar assigned a dictator – General Trepov, who chose three words from the freedom proclamation: “Do not be stingy with bullets.” And the first to demonstrate the talents of autocracy were … the pogroms against the Jews. My father, may he rest in peace, took these very much to heart. He felt that the revolution was just beginning and for us Jews, no good things would come of it. And we had to emigrate, but to where? The immigration to Palestine was locked up. And besides, what was there in Palestine at that time? A few settlements that could hardly stay afloat.

It is noteworthy to stop for a bit at the pre–revolutionary and revolutionary period. In the time of the Russo–Japanese war, there was a great movement for freedom. The autocratic rule eased its grip up a little…

[Page 194]

… The government cabinets were changed frequently, and a freer spirit spread across the Great Russian Empire. The number of newspapers increased daily, and one could hear some “free” words. I remember that I worked for a daily newspaper in Petersburg – by the name of Kopeka, and it was the first paper that printed sharp words. One fine day, after the slaughter at Tsushima, where a Russian flotilla suffered a terrible loss, the Kopeka published a sharp article, framed in black, saying farewell (kaddish de'rabonon) to the Czarist autocracy. Understandably, the paper was soon shut down. But in less than a week, I began work with another paper under a different name, that was even sharper.

When the first duma (council assemblies formed by the Czar) was dissolved and 185 deputies packed themselves off to Finland, Wiborg, and they put out a circular, plain and simple, that no one should pay taxes or go up to the army, and people should boycott the government…. I received a hectographic copy (early type of photocopy) of this circular and collected my fellow workers somewhere on the cap–making street, and read and explained the content of this pamphlet.

One Friday afternoon, Pinyele Kreindel comes to us. He is a grain merchant at the Yedinets bridge, and asks my mother, of blessed memory, about me. As it happens, soon I arrived home. I ask: “What's wrong, Reb Pinye?” And he tells me this story: In a line of prisoners, there was a young Jewish boy, a distant relative, the son of a shokhet. This son left to go learn in a Lithuanian yeshiva, and what happened there, Heaven protect us, is that he went off the straight path and became a tzitzilist (a Zionist who remained somewhat religious). As he [the boy] was going back into town via the Lipcani bridge, and knowing that this man was his relative, the boy threw a note that the children of Herzi the lawyer picked up and gave to Pinyele. So now, Pinyele came to me that I should do something for this boy. He had already seen the boy, as he was locked up in jail, in the bailiff's territory. The boy is very distraught, naked and barefoot, exhausted from long months in prison and long marches in prison lines. He, Pinyele, had already visited him, because the guard was an old friend of his and someone with whom he had even shared a few grivenes (well browned roasted bits of goose or chicken skin).

“Good, Reb Pinye,” I say to him. “Don't worry. Anything that you need for him, just come to me. But be careful, very careful. This smells from treason (rebellion).”

“What do you think, Shloimele, that I'm a fool? You can rely on me,” says Pinyele. And soon, a few rubles were raised. My father, of blessed memory, did not rest. My mother, of blessed memory, already got Pinyele some …

[Page 195]

… warm underwear, a warm fur hat that I wasn't wearing anymore, a coat, and so on. The whole town was in an uproar.

One day, I come home and find my former teacher Yoisef Hanzis is secretly talking to my father, and I hear my father, of blessed memory, saying: “I don't know how I would be able to live through such a thing if, Heaven forbid, such a thing were to happen to my Shloimele.” And we saved him (the boy in prison)! When they were taking him to Khotin to prison, two riders broke into the line of prisoners and freed him…

Once, I come home very late at night, after 12, and find my father awake. Why aren't you sleeping at this hour, I ask him. It's nothing, he says. But my mother already told me the next day that my father can't fall asleep when I'm not in the house…. And again, one Shabbos evening, I come home and… my father is lying in bed. Not usual for him. He would always go daven the minkha prayers. Surprised, I ask him what happened. He says it's nothing, but something isn't right. Now my mother gives me a wink and calls me over, and tells me with tears in her eyes, that my father went to bed as usual. Suddenly, he jumped out of his sleep and fell out of his bed…. She immediately went to call Dr. Hokhman, who was both a doctor and personal friend of my father, and Dr. Hokhman diagnosed the following: nerves. He said, “Reb Moishe, you're taking too much to heart. You have to leave this land that is filled with blood….”

All these events took a great toll on my father's health and so we decided to emigrate. But this is easier said than done. All this while, the political situation became worse. A flood of pogroms wiped out many Jewish settlements. Briceni was set up to take care of itself. All winter, scores of youth did not get undressed, and as mentioned, there were no pogroms in Briceni.

In our family, the question about emigration was always there. The first question was to where. We had a lot of relatives in North America, but we already knew too many “wonderful” things about North America and her sweat shops. Other than that, having been inundated for many years with the propaganda of Nakhum Sokolow and the newspaper Hatzefira, and my father was drawn more to working with the land… In Argentina there was already an established Baron de Hirsch colony. We would now be going to immigrate to a free land, in the free republic, and we were to become land workers.

The makeup of our family is designed perfectly for this task: my father just over 40, me just barely 20, two sisters and two other boys of fifteen and six. So, just as we would come to …

[Page 196]

… Argentina and end up in a Jewish settlement, they would quickly grab us up and give us a colony that is a hut. My father began to become busy with emigrating. He registered with the immigration bureau ICA (Jewish Colonization Association) in Peterburg, received an answer with precise details, applied for a governor's pass to be able to leave legally so as not to have to go through punishment even after death for having smuggled across the border; he registered with the immigration bureau in Odessa, where the secretary then was Zalman Itzis, a person of similar mindset. Other than that, we had to sell the house, selling the household that was so for many long years, and generally, prepare for the trip.

Everything went slowly, and we were ready sometime in the summer. But the closer it came to leaving, the harder it became to separate from family members, friends, and good friends, and everyone else, and with friends in general. My father, of blessed memory, had raised an entire generation – not only of elders in shul, but also of enlightened youth … hard to tear yourself away from your roots. The entire town was buzzing. We decided to leave just after Sukos. From Rosh Hashana onwards, the house didn't rest. All day long, until late into the night, people came to say goodbye. We were simply exhausted from receiving everyone and from no sleep. The Zionists organized a farewell dinner. The best and most beautiful elements of the town were there at this banquet. Understandably, there was no shortage of speeches and public singing. It was decided at the banquet to take a photograph of all those who had been present, and on the next day, all the friends gathered together, friends and relatives, at Sholom Bartfeld's garden house where the photograph was taken. In order to have this photograph as a memento, in the name of all the friends, Avremel Goldgal inscribed the following: Dear brother, We are far from you in place, but we are not far from you in spirit; our souls will cling to you. And this picture will be a memory forever for you, our brother, the spirit of our nostrils [breath of our souls]. Mr. Moishe, Bar Yosef Lerner. And I promise that you will see in this picture that we love you very dearly. With this I give you, from your brother, memories for your name, forever. Briceni, 27 Tishrei, 5667 (1907), to be precise.

Sixteen couples escorted us to the train station Romankowizi on October 3, from where we left from Odessa and from there on the 13th of the same month, left by ship to Argentina.

Translator's Footnotes

[Page 197]

by Shlomo Serebrenik, Rio de Janiero

Translated by Pamela Russ

Thanks to its central location, Britshan always had a high social, economic, and cultural standing in the area, regardless of the fact that other towns were located on the shore of a large river (Dniester or Prut), or near a train station. One could even claim that sooner or later Britshan would steal away from the city of Khotin the privilege of being a central town.

There are no precise documents that describe the formation and establishment of the city of Britshan, several hundred years ago. But you can deduce that the need for a resting point in the traffic between the Dniester and the Prut in all the various directions led to the set up and development of an important population center in the intersection point where Britshan is located.

What is relevant to the actual position of the city, is to notice that it fulfilled the minimum of city construction requirements: the proximity of running water, which in this case is a fundamental specification; the existence of an almost flat shore with an unlimited possibility for expansion; good topographical features – not completely flat, but also not hilly – and that means, easier transportation and no danger of stagnant water and floods.

With regards to the actual structure of the city of Britshan, one can say that it really doesn't fall under any of the classical schemas: not the “right–edged,” not the “ring” schema, and not even the “star” schema, although there is something from each of these to use, especially from the star schema.

The pattern of the streets is not simply irregular, but the opposite, there is a real system. For all, there are two main streets that cut into a rectangle and which are the shoulders of the city: from east to west – Pocztowa Street, and from north to south –– Rymkiewiczer–Bad [Bath] Street. These two streets cut through the entire city, divide it into four parts, and continue outside of the city to the roads that lead to the surrounding towns and to the outside world: Pocztowa–Yedinets Street goes to Yedinets and Sekuryani in one direction, and to Khotin in the second; and Rymkiewiczer–Bad Street goes to Woskowycz (train station) in one direction, and to Lipkany in the other. The cross–point of these …

[Page 198]

… two main streets is the economic and traffic center of the town, the pulse of the settlement.

Parallel to these two main streets, there are large back streets that ease up the traffic when it is tight on the main streets. These are Khotin and Kowalisa Streets, parallel to Pocztowa Street; and the Hospital Street and Lipkaner, parallel to Rymkowiecz.

There are specific cross streets missing, but in a small town they are not so necessary, and aside from that, there are the large places (“pozharno”[fire department] and “torhowycze” [open market]) that enable free diagonal traffic.

What is relevant about the shape of the streets, is that you have to assert that it is good, and corresponds to its topographic characteristics: The streets are not long, they are flat, and they are not snaking, only slightly curved. Thanks to this, and thanks to the gentle hills of some of the places, the horizons are bordered and the appearance esthetically appealing.

The ethnic zoning is distinct: the Jewish population in the center and the Christian (Russian) on the periphery, where the neighborhood spreads out. One needs to notice that the division is not symmetrical: The neighborhoods are not uniform, in size and in importance, and there are absolutely no neighborhoods in one quarter of the periphery (Quarter 1). Of the remaining three, the 4th quarter boasts the largest and most important neighborhood.

Although there is no real “professional” [systematized] zoning, it is still noticeable with clear lines and with a certain logical reasoning: The general main commerce – in the central parts of Pocztowa and Rimkowieczer–Bad Streets, so around “Perekrest” (“the intersection”)[ Perechrescie]; the grain trade – at the beginning of Pocztowa Street, near the Yedinetse bridge; overnights [with stables] and inns – around the torhowycze [open market place], right side; taverns – near the torhowycze, on the left side; craftsmen – in the secondary back streets, specifically in the second quarter.

One can see that these neighborhoods are not part of the economic life of the town.

The public institutions and places – administrative, religious, cultural, and social – are well divided up, with the objective of efficiently servicing each area of the city, and also the various social classes and ethnic groups of the population

This affirms that the official government institutions, as well as the pure Christians are concentrated in the main neighborhood of the fourth quarter. These …

[Page 199]

… are the hospital (Balnicza), the prison (Chad Gadya), two classic schools (Uczilyscza), the gymnasium, the church, and the non–Jewish cemetery; the rest of the official institutions that are connected to commerce and especially to the wider population, are found in the Jewish pale: postal service, telephone station, “wolost” [administrative division] (for taxes and justice).

The purely Jews institutions (Houses of Study, hospitals, schools, theater), are located mainly in the center of the town, but also in several more distant points from the Jewish district.

There are four open places, well spread out: two market places “Pozharno” [“fire department”] and Quarter 1 and “torhowycza” [“open trade,” i.e., bargain center] in Quarter 3; and two promenades (the fire department meadow in Quarter 1 and the church meadow in Quarter 4); other than that, there is a large open area on the right side of the river, already outside of the city – this is the bridge meadow – that serves mainly the population from the closer edge of the city.

The cemetery is another situation: outside of the city, on the other side of the river, on the highest tip of the mountain, a city of the dead that rules topographically over the city of the living. Thanks to the elevation of that setting, you can see the cemetery from all different corners of the city, and it is particularly imposing in the evening hours before sunset, when the sun's rays from the west create fiery reflections on the black granite tombstones and mausoleums in the east.

There are no memorials. Only a small historical monument (“pomiatnik”) at the beginning of Pocztowa Street, where the beginnings of the city likely were, and from which with time, it spread in the general westerly direction.

[Page 199]

by Yakov Amitzur–Steinhaus

Translated by Pamela Russ

Donated by Roberta Jaffer

What was the social condition of the Briceni Jews like?

Not having any statistical numbers, it remains only for us to rely on the power of deduction. But, I think it will be very close to the truth. Also, we will deduce that about 40% of Briceni Jews worked in trade, approximately a third were manual workers, and the rest were all kinds of middlemen [jobbers], independent professionals, religious workers (rabbis, ritual slaughterers, teachers, beadles,

[Page 200]

trustees, and others), ordinary Jews without a defined means or source of livelihood, and some who had absolutely no livelihood at all.

Briceni was effectively a city of means. Correctly speaking, this appears to be exaggerated, and if it were possible to research this, it would look very different. But in proportion or relation to other similar places, the situation for the Briceni Jews was quite fine.

Briceni bordered about 20 large and rich villages, from which it drew its main earnings. The local farmers used to bring all the products of their fields and gardens into the city: wheat, corn, barley, various fruit, and all kinds of greens. Besides that, they brought poultry and eggs and also livestock to sell: cows, sheep, horses, pigs, and so on. Also, the wives of the farmers would bring their homemade handiwork that they appeared to have worked on during the long, cold nights of the winter – such as towels, rugs, heavy linen, and so on. They sold these to the city residents, both to merchants and to others for their personal needs, and then with that money, they went to the shopkeepers and craftsmen in town to buy everything that they needed: foodstuff, clothing, shoes, hats (fur caps), all kinds of dishes and work tools, and more and more. They also used to bring all kinds of things for repair. The economic standing of the city Jews, therefore, was closely tied and completely dependent upon this setup in which the local village farmers were involved, and their social structure was also affected by this.

A special class of Jews was formed – the so–called grain merchants, whose business it was to buy grain from the farmers. The majority of these Jews were small merchants, restricted by their financial means, who on that same day, or the following day, had already sold the grain they purchased to the larger merchants, comforting themselves with minimal profits. Only a very few of them could allow themselves to keep the grain in storage and wait for better prices. Their homes stood at the very edge of the city – the majority, by the Jednicze bridge, where they set up storage for the grain, each one near his own house. No one waited for the farmer to come to him. Each merchant would go to the other side of the bridge and meet them [the buyers] and quietly pray to himself that he merit being the first to catch the non–Jew and sell a little grain. When a farmer's wagon appeared in the distance, tens of Jews would quickly go over to him. Each merchant would pull over the buyer towards him, each one offering a better price, so long as he could sell him some grain. One speaks to the farmer, the other holds on to the horse, and …

[Page 201]

doesn't let the farmer leave, and another is already sitting in the wagon and urging on the horses so that they should leave… Fourteen Jews are fighting over one non–Jew, and everyone is promising him the sun and the moon, and the non–Jew stands there confused and does not know what to do…

The competition was great and from year to year it only increased. They put up warehouses on the other side of the bridge, and each year, [added more] farther down. They began to buy up grain in early spring and gave the farmers notice about [buying] the upcoming crop. Understandably, there were growers who knew how to use this opportunity well: They took advances from one and also from another, and when the time came, they sold the grain to a third, and so, sue me … In this way, lots of Jewish money was lost, but what can you do – you have to do whatever you can do, and that's life…

We also had a large number of bigger merchants who, with the help of the middleman, used to buy up all the grain and also buy the crop off the local landowners in the surrounding villages. They would send the grain by wagonload in part to the internal provinces and in part export it out of the country, to Germany and Austria.

Similarly, there was the egg and poultry business, which not many people had as their trade. Here too there were middlemen who bought for the bigger merchants, only with the difference that the latter were not local, and the purchased poultry and eggs would be sent out that very day to Novoselitsa, the bordering city of Austria.

A small number of Jews did business in livestock selling, especially with oxen. Aside from knowing the business and being experienced, they needed greater sums of monies in this business, both in cash and credit, because of the large investments, and because of the required perseverance [time needed to bring their products to market]. Therefore, the risks were great, but the profits of the business were, as described, outstanding, because these merchants were always wealthy. This business was also set primarily for export to Austria and Germany, but also the internal Russian market bought a fair number of oxen as work animals and also for meat.

A large volume of business was with sheepskin, which they used for fur hats [kutchmes] and coats. Long before spring, the sheepskin merchants, among whom were also wealthy artisans, furriers, and fur hat makers, went out into the near and far villages and bought from the landowners and rich farmers, who owned large flocks of sheep, all the lambs that would later be ….

[Page 202]

born – and when the time came, they took the lambs from them. The butchers bought the meat, and the simple skins in large number went to internal needs, while the better ones were exported out of the country. The trade grew significantly after the First World War in the time of the Rumanian occupation, and included many tens of Jews who made large profits.

One of the main sources of income was small shops, which were mostly set out for the farmer customers. Every Tuesday, which was market day, and on Christian holidays, the stores were overfilled with customers, farmers, and farmers' wives who went from store to store, and after much haggling and hand–shaking, they bought everything they needed, from big to small, food stuffs, all kinds of materials, ready–made clothing (cheaper clothing), footwear, fur hats, haberdashery, all kinds of pots and pans, agricultural and other work tools, and more and more. The wine sellers and eateries also earned well on that day. But it was a short season – in autumn and in the winter months. The rest of the months' sales were very poor, the stores were almost empty, and the storekeepers would sit in front of the doors and look out for customers.

A large number of the craftsmen also worked for the needs of the poor farmers. True, there were a few tailors who sewed for the residents as per their orders (these Jews did not purchase ready–made clothing); the larger number, however, sewed finished and cheaper clothing (“tandaitenikes” [thrift shop]), that were mainly set out in the stores. But there were also tailors who set out their wares in stalls on market day and would sell them themselves, and sometimes even in their own homes. Just as many other store owners, they would go out to the neighboring villages with their merchandise. Before World War One, some would go with their wares to the Podolske towns on the other side of the Dniester River. And not only the tailors – the same was done by the furriers, hat makers (fur hats), shoemakers, and other craftsmen. This was a combination of working and trading.

The line between work and trade was blurred also by other craftsmen who would produce necessary items and sell them as well, such as: carpenters, tinsmiths, cart/wheel makers, blacksmiths, coppersmiths, and others. Other than these, understandably, there were many other workers who earned their living from the city's

[Page 203]

Jewish population, such as butchers, watchmakers, musicians, wagon drivers, porters, dyers, and others.

A small number of Jews worked in agriculture (“pozesies”; [estate lessees]). They leased land from landowners in many regions, and the farmers in the neighboring areas worked the land. The lessees would earn a nice living and lived by all standards, very comfortably. After World War One, during the Rumanian occupation, when the Czarist law that forbade Jews from buying land was abolished, some lessees and others bought their own land.

There was one known family in Briceni – Moshe Berstajn and his son – who, during the regime received special rights to settle in his own land. This was one of the richest families in Bessarabia and they owned large areas of land and their own estate, the village Sienkiewicz, with a distillery and a large mill. Yosef Babanczyk, another wealthy Briceni Jew, built another large mill in the village Czepielewicz. The two mills were among the largest in Bessarabia and delivered flour not only to Briceni and the surrounding areas, but also to many other cities in Bessarabia and Ukraine.

It is understood that the social situation was not equal for everyone, and various social classes evolved. Among the merchants and storekeepers were those who ran bigger businesses and had a more expansive life. In contrast to that, there were a large number of those who lived all their years in great need and deprivation, their minds were dried out with worries, and they would always be rushing to “catch” a gemilas chesed [charitable free loan] or a loan on interest in order to prepare for the upcoming market day.

The same was true for the craftsmen: There were those who successfully worked their way up and reached a fine status. They enlarged their workshops, they were able to buy up the necessary materials on time and as much as they wanted, and always had what to sell. The larger number, however, inevitably and with bloodied sweat, worked for a small piece of bread and got it with great hardship. And many of them remained in poverty their entire lives and could not feed their families.

There were also some Jews who they themselves did not know how they lived. They had no vocation at all and no specific business, and their earnings were just by chance – from whatever. They lived from “maybe”: maybe there would be a middleman possibility, or a partnership; maybe he'll be able to get a bargain; maybe he'll be able to

[Page 204]

stand in as a partner in someone's business and something will fall his way… The Jews lived with an outlook towards miracles. But as is known, there are no miracles every day. Therefore, many of them relied on support from near and distant relatives, and some even relied on the community. And of course, there were the professional beggars.

So it's not really any surprise that many had to leave their homes to search for their fortune in faraway places, in Brazil or in America. First, it was only young men who left – if only because their deprivation chased them, or because they were sick of the emptiness and struggle, not having any hope to organize anything for themselves. Some left their homes to avoid military service of “panyen,” serving the Russians. Others, tried to outmaneuver the law and committed [a small crime] against the government (maybe that's why they used to say: “…ran off to America”)…

Some time passed and letters from the young men would arrive, saying that “…we're making a living,” and that America is generally a golden land [“goldene medina”], and you can achieve great wealth; there is gold in the streets – just go and shovel it up… From the pictures they sent, you could see that the boys did really look very fine and happy, and they are dressed well. Later, checks and dollars began to arrive from there, and quietly people began to think of leaving. And if the time came that the son sent ship–cards [travel tickets] for the family, people were very envious of them, even though the families did not speak openly about them.

In general, they would be very secretive about leaving for America, and all preparations were done discreetly, as much as possible. Why? Probably for two reasons: First, everyone feared angry tongues – they would cross the borders illegally, and therefore, it's better that fewer people know about this, since everyone has their weakness! And second, it didn't look right for the regular city people to emigrate. So they always made a show [pretense] and covered up the real reason. – As they say, “Pinch the cheek so the color should stay”[1] – and here they really have to emigrate.

The beginning of the emigration was really small in numbers, and only with time did the numbers increase and then evolve into a larger flow. Complete families picked themselves up and moved to America. For some, business worsened, or right from the beginning it was no good; for others, the daughters grew up and the families could not prepare a dowry or support; some were fed up with sitting idly and waiting for better times – so all he had left was

[Page 205]

one way out, to immigrate to America … Before World War One and a few years afterwards the immigration was to America (the U.S.) and less so, to Brazil.

Later, when America greatly curtailed the influx of immigrants, and with the influence of the strengthened Zionist call, the Aliyah [immigration to the Land of Israel] numbers increased, especially among the young.

From time to time, there would be difficult years – because of lack of rain, the fields did not produce crops, and the farmers did not have anything to sell or have anything with which to buy. Another time, there was inordinate abundance – but the prices fell greatly, and there was no market. Then there was a winter that was too cold, and then – a summer that was too wet… Sometimes, distant events somewhere outside of the country also affected the market. The merchants would call this a “crisis.” These types of “crises” would happen too often and last for too long. Then the economic situation in the town would become weak, and the ripples of this would last a long time.

After Rumania's occupation of Bessarabia, the economic situation in Briceni, and in all of Bessarabia, worsened tremendously.

Bessarabia is, as known, an agricultural area, and its products, other than being exported outside the country, would also be sold within the Russian provinces. In one motion, Bessarabia was torn away from its position and became a part of Rumania, which is also a rich agricultural country. This alone was enough for the economic stability to become weakened. For that reason, Rumania established a policy of oppression against the entire Bessarabia population, and particularly against the Jews. It absolutely did not consider the economic needs of Bessarabia and did not give them even the minutest consideration. The results of this were quickly noticeable, even for us. A slow but incessant process of economic decline began, as well as a general impoverishment, of which only few were spared. From year to year, the earnings dropped. The number of non–earners grew, and the needs grew, especially among the poor classes.

It came to the point where new charity organizations had to be set up in order to somewhat ease the needs. They established the “Bikur Cholim” [“taking care of the sick” organization]

[Page 206]