|

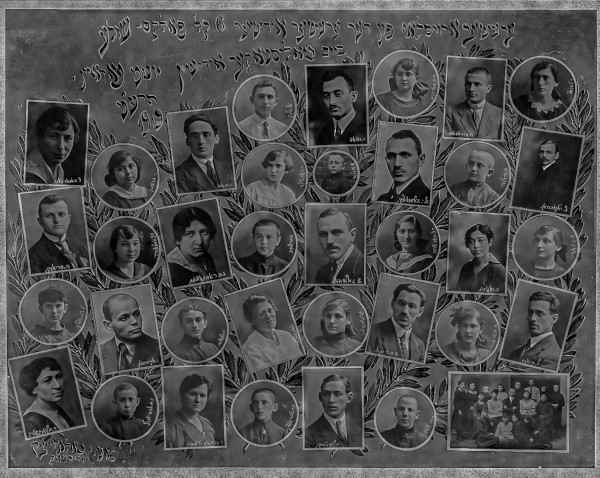

[This photograph was edited by Dr. Tomek Wisniewski, The Place, Bialystok]

|

|

[Page 52]

by M. Sirota

Translated by Beate Schützmann-Krebs

English Proofreading by Dr. Susan Kingsley Pasquariella

We still remember the pious saying well: “Toyre iz di beste skhoyre” [Torah is the best commodity]. Bialystok certainly did not fall behind other Jewish cities in terms of this valuable commodity, and it has always been considered a place of Torah.

Bialystok was rich in bote-medroshim [houses of study]. There was hardly a street without its own study house. There were even alleys, such as the “Green Alley,” where there were three prayer houses: the Old Green Bes-Medresh, the New Bes-Medresh, and the Gmiles-Khsodim Bes-Medresh[3].

In addition to the Great Shul, there were several bote-medroshim and kloyzn [prayer halls] on the shul-hoyf [synagogue courtyard]. Chassidic philosophy was also very widespread in our city. In Bialystok, the Kobriner Rebbe, R' Nochumke, led his Chassidic followers, and later his son-in-law, Rabbi Meir'l.

The Slonimer Chassidim also had a large community, and the Slonimer Rebbe lived in the city for a time. Other Chassidic groups were present as well, including the Gerer, the Kotsker (whose “shtibl” united the Sokolover, Lukover, and Pulaver), the Rodziner, Rodziminer, Karliner, Trikover, and others. There was even a “shtibl” of the Lubavitshers.

All the Jews in the study houses and prayer rooms formed the lifeblood of those who taught and spread the Torah. Most bote-medroshim were constantly filled with Jews immersed in religious books. In the evenings, between afternoon and evening prayers, Jews would sit around a table and study.

Whether within the “Khevra-Shas” [a society dedicated to studying the six sections of the Talmud] or the “Khevra-Mishnayes” [a society dedicated to studying the six Mishnah sections in the Talmud], Jews usually studied the “Khaye-Odem”[4] and “Eyn-Yakev”[5]. Jews with monocles, but also those with good eyesight, were seriously engrossed in their books and devoured every word of the rabbi.

The gilded covers of the volumes of “Shas” [six sections of Mishnah and Talmud], “Mishnayes,” “Rambam” [Maimonides], “Pnei Yehoshua” [Talmudic work of Rabbi Yaakov Yehoshua Falk], “Zohar,” and similar works always shone from the bookshelves and cabinets.

In addition to countless treatises by sages and rabbis with commentaries, there were also books with explanations of the Torah and Talmud, special books with sermons for every holiday and memorial day, and a large number of books with “muser” [Musar, Jewish ethical lore].

The Great Pulkovoyer Bes-Medresh and the Yekhiel-Nekhe's Bes-Medresh had extensive rabbinical literature at their disposal, and the high-class Bulkovshteyn's Bes-Medresh was even more richly stocked with books. There was a special, separate room, a kind of library, where one could look at treatises and even learn a Talmud lesson through repeated recitation without being disturbed.

A small bes-medresh, whose creator and founder was neither a great Jewish scholar nor a particularly pious man, achieved a particularly high level. His name was Meir Fish. This place of prayer was located on the upper floor [of a house] on Rozhanski Lane.

R' Meir Fish, the owner of the house, was known in town as a wealthy and prominent man. He lent money at interest and had a distinguished clientele that included Russian officers, civil servants, and Polish landowners. With customers like these, it was impossible to lose money. Nevertheless, he was stingy with every penny before spending it on himself or his wife.

On Shabbat, they bought the cheapest meat and not-too-expensive fish… According to eyewitnesses, on weekdays the family made do with stale bread, potatoes with their skins on, and a herring. R' Fish didn't spend much on clothing either.

The generous dowry from their wedding was enough for them. They only bought a new item of clothing when the old one was falling apart. He had no worries about raising children because his wife didn't give him any. This may have sealed his behavior.

In fact, R' Meir Fish had “no children and no cattle.” However, he had plenty of poor relatives who often visited him and poured out their bitter hearts to him. To put an end to their constant visits and complaints, he set up a small annual pension for them on the condition that they bother him less.

His only purpose in life was his little bes-medresh. He was meticulous about ensuring prayers were said there daily. In his old age, when he felt that the end was near, he wrote a will allocating a certain sum to his family and to charitable purposes. He also set aside a sum for the maintenance of his bes-medresh, where people were to study day and night and strive to acquire necessary religious books. His last will was fulfilled to its fullest extent.

A rich collection of rabbinical literature was acquired. “Noble youths” who were preparing for the rabbinate, but also ordinary students, spent whole days there immersed in the Gemara[6]. Additionally, “mishmorim” [study groups] were established with Jewish scholars and young men from the yeshivas, and later supplemented with “musernikes” [followers of the moralistic movement]. They chose a night on which to study together.

For many years, I also attended my “mishmor” group every Thursday night. It was the only place where one could study day and night.

To keep the students from falling asleep, each participant was served hot tea and sugar twice a night. The smokers were given a few cigarettes. A “Khevre Shas” [Chevra Shas] also met in Meir Fish's Bes-Medresh.

For the worshippers and students, the besmedresh was also honored by the presence of the Chassidic Kobriner Rebbe, R' Nochumke.

[Page 53]

and after his death by his successor, his son-in-law Rabbi Meir'l Shtsedrovitski. In addition to his position as rabbi, he was crowned with the title “Moyre-hoyroe” [Rabbi and Judge] and became a member of the rabbinate.

A “siyum” [completion] of a Gemara tractate was a bit like a holiday. R' Meir'l would recite the “hadran,”[7] and then everyone would have a drink. A “siyum hashas” [completion of the entire Talmud study] was an even greater celebration. Well-known rabbis from nearby towns came especially to participate in the festivities and recite the “hadrans”[7], and people stood with their mouths agape, greatly enjoying their wit.

Needless to say, in addition to the spiritual aspects, there were also earthly, material things. A fine “lekakh” [honey cake] was prepared, along with “bronfn” [liquor], and everyone everyone took a bite.

The pious city of Bialystok was proud of its magnificent botei medroshim, numerous Hasidic shtiblekh, and minyonim [prayer quorums]. It also boasted its talmetoyre (Talmud Torah, an elementary religious school for the poor) and yeshiva.

At one time, a yeshiva stood somewhere at the edge of the city, near the windmills… The head of the yeshiva was then a well-known Jewish scholar named R' Pinkhes [Pinchas], and R' Zalmen (I seem to recall his name was R' Zalmen Maggid)–served as the mashgiyekh [rabbinic supervisor]. I got to know him after the yeshiva had already ceased to exist.

Anyway, R' Zalmen, a tall man with a pale face and a white, patriarchal beard, continued to weave a thin thread of life from the defunct yeshiva, giving Talmud lessons to dozens of young people from the province for several more years.

His good friend, the “Moyre-hoyroe” [rabbi and judge] R' Henikh, who also impressed with his rabbinical appearance, often came to visit him. He often started a casual conversation with the students because he didn't want to show that he was just checking what they had learned.

With R' Zalmen's death, the wistful Gemara-Nigun[8] of the poor Argentine Bes-Medresh also disappeared. R' Zalmen was the last “Mohican” who let the voice of the Torah be heard in the remotest corner of Bialystok.

Recently, the talmetoyre and the yeshiva in the broad Pyaskes area had already become famous in Bialystok. In a large courtyard, twelve grades (the so-called kitot) for the students of the talmetoyre and four grades for the yeshiva had been set up in spacious rooms in two brick buildings. Each class had 20-30 students.

The first grades [of the talmetoyre] were intended for the “Tinokot shel Beit Raban” [the little children from the teacher's house, the introductory levels], who learned the Yiddish alphabet and the Pentateuch with the commentaries of “Rashi.”

In the eleventh and twelfth grades, the students began studying the Gemara. The final grades were the antechamber to entering the yeshiva.

In these Torah educational institutions, the payment of tuition fees was not mandatory. However, people from the wealthier classes would voluntarily pay a certain amount each month for their children.

While studying at the yeshiva, I often observed the eleventh and twelfth grade classrooms from a distance. The Odelsker, a tall, fat Jew with a reddish-blond beard, ruled the eleventh grade with an iron fist. To put it politely, he looked like a well-fed bal-guf (fatso). It was no picnic for his students. But people said he was a good interpreter.

In the twelfth grade, with Kolner, it was exactly the opposite. The teacher was sickly. He had a lung condition, and he was so emaciated that his life force could barely remain in him. He never scolded his students or said a bad word to them. He was very popular with those subordinate to him. The students tried to make less noise so as not to cause him grief.

Only a relatively insignificant number of students from the higher talmetoyre classes continued their Talmud studies at the yeshiva. This was understandable, as most of the “talmetoyrenikes” were local children from poor backgrounds. Many of them were orphans, and for them, there was no point in continuing to sit at their benches if they couldn't eat their fill. It was more worthwhile for them to learn a trade so they could earn a penny through their own labor.

As soon as they knew a word of Hebrew–regardless of whether they could already read a Gemara text or not–they felt that it was enough, more than enough…

The yeshiva exerted a great attraction on poor children from the provinces. First, they fulfilled the principle of “hevei gola lemakom Torah”[9]. Second, they believed that the Bialystoker Jews would not let them starve, and third, they would simply experience a change of scenery and see a big city…

The boys actually were not wrong. The Jews of Bialystok were happy to provide them with one meal a day in exchange for their studies. Even families who were not particularly wealthy considered it their duty to invite a poor yeshiva student to eat at their table on a certain day of the week.

It was also not difficult for the youngsters from the provinces to find a “corner” where they could sleep. The Jews had compassion and did not let any unfortunate child spend the night outside.

Some of them were so industrious that they found not only a place to sleep, but also an opportunity to earn a few “gildn” [coins of little value]. For instance, owners of leatherwork and fabric stores would allow yeshiva students to sleep in their stores and pay them a few “gildn” each month because doing so kept them safe from robbers. Of course, such places were not warm in the winter, but when you are young, you can tolerate it.

In fact, more than 80 percent of the yeshiva (without exaggeration) consisted of young boys who had come from the provinces and even Warsaw. And just like the students, the teachers also came from other cities.

The teacher of the first grade of the yeshiva was called the “Semyatitsher” [because he came from Siemiatycze]. He spoke in a drawn-out manner, in the Polish style. The teacher of the twelfth grade was a Vashilishker [he came from Vasilishki], not far from Vilna. He spoke with a “sin” [Lithuanian Yiddish dialect].

[Page 54]

The third-grade teacher was the “Orler” [he came from Orla]. The only teacher who was called by his real name was R' Shimen Zelig, the head of the yeshiva and its supervisor. However, he was not from Bialystok either. The importance and prestige of each teacher could be recognized by his clothing.

The “Semyatitsher” from the lowest grade wore a small black cloth hat and a short kapote [caftan].

The “Vashilishker” wore a hard kapelyush [fedora hat], similar to those worn in Vilna, and a robe whose color was difficult to determine.

The “Orler,” who ranked just below the head of the yeshiva, covered his head with a wrinkled and worn rabbinical hat and wore a garment that was half jacket and half caftan…

Understandably, R' Shimen Zelig, the head of the yeshiva, wore a rabbinical hat that radiated purity and cleanliness. His shiny silk robe gleamed. He had a very pleasant appearance with a young, fresh, noble face, dark brown eyes, and a black, beautifully combed beard. He was of medium height and always had a friendly smile. Of course, I am talking about the years when I studied there myself.

He was an excellent lecturer to all; his daily Talmud lesson was clear and easy to understand. Even those with weaker comprehension could understand it. He knew every student in the yeshiva, not just those in his class.

I still clearly remember what happened to me.

I was thirteen years old when I entered the yeshiva and joined Orler's class. My father wanted to make me happy for my bar mitzvah. He took me to Mr. Shtern's hat shop (he later immigrated to the United States) and bought me a black kapelyush [fedora hat], from the “Syeratshek Company” for three rubles and fifty kopecks. I would have preferred a beautiful Jewish hat, but I had to accept the kapelyush with gratitude.

When I first showed up at the yeshiva wearing a kapelyush, there was laughter and ridicule. Children started singing, “Here comes a fool in a kapelyush!” Others felt up my hat and judged it critically. It really upset me.

When I got home, I told my father, “I don't want to wear the kapelyush anymore!”

My father explained that the ridicule stemmed from childish envy. I had no choice but to continue wearing my hat.

One day, when my teacher, the Orler, was absent, some children took advantage of the opportunity and caused a small commotion. Since our classroom was close to the Semyatitsher teacher's classroom, he came in and shouted in his Yiddish-Polish accent. Several naughty boys began to mimic his pronunciation.

He then ran to R' Shimen Zelig, who immediately appeared together with the Semyatitsher to find out what had happened.

The Semyatitsher recounted in a loud voice how he had been insulted. Pointing at me, he said, “The one with the ‘kapelitsh’ incited rebellion.”

And yet I was one of the very few who had stood up for the honor of the Semyatitsher. R' Shimen-Zelig glanced at me and then at my accuser and, after a moment's reflection, said:

“Semyatitsher, you are certainly mistaken… this student is not capable of such despicable behavior… think carefully… you know what it means to spread slander, don't you?”

The Semyatitsher started stuttering and stopped insisting that I had disobeyed the teacher. However, I wanted to take revenge on my kapelyush, and I refused to wear it anymore. So, I wore my winter sheepskin hat all summer long…

R' Shimen used to teach his daily Talmud lesson in the bes medresh, where his class had a designated seating area. On the first Shabbat of every month, the gaboim (Jewish religious functionaries) from the talmetoyre and yeshiva would come, including Moyshe-Mordekhay Monosevitsh, Ayzik Horodishtsh, A. Goldberg, Paylet Mokovski, and others.

Every Shabbat, R' Shimen Zelig would recite chapters from Mesilat Yesharim [a classic work of the Jewish ethical movement Musar] to his students.

There were two interesting characters in R' Shimen Zelig's class. Both were called “Khayim.” One was an exceptionally dedicated and sincerely pious student. He emphasized words during prayer with such religious enthusiasm that he inspired other students to follow his method…

He was a good-natured person whom everyone liked. People always waited until he had finished his Shmone-Esre Prayer [eighteen blessings, recited while standing]. Incidentally, he was the best student during my time there. We didn't just call him “Khayim,” but added a ‘ke’ to make it “Khayimke.” He wasn't particularly astute, but had quite average abilities. But he worked hard–from early in the morning until late at night. He certainly became a religious authority in his community somewhere and was definitely popular there…

The second Khayim was cut from a completely different cloth. He was given a surname at the yeshiva so that people knew which Khayim they were talking about. …He was neither pious nor a dedicated student, but above all, he was not at all scholarly. He just liked to argue sharply and had a particular weakness for speaking in front of an audience.

Often, when the opportunity arose and R' Shimen-Zelig went to breakfast, he would go up to the bimah [podium] and give a speech. Sometimes it had a little flavor, other times it didn't make any sense, like a kind of [comedic] “Purim speech.” But at least it sounded good. I don't know if he later became a preacher somewhere.

For a while, he, Khayim Hurvits, was an employee of “Dos Naye Leben,” where he wrote as a journalist. Later, he emigrated to America, and I never heard from him again.

At the end of each semester, on the eve of Passover and on the eve of the Days of Awe, exams were held for the best students of the Orler and for the students of R' Shimon Zelig.

[Page 55]

The two best students in each class, who had distinguished themselves, received silver watches from the famous company, Shlitl. HaRav Fayans, HaRav R' Yoel, and Goldberg, among others, conducted the exams.

Along with me, Shyele Rapoport also studied with the Orler. He is now the famous essayist and literary critic Yehoshua Rapoport. Even back then, he read more books “outside the Jewish biblical canon” than the Gemara, so he was not among the best. He was the only one who caused the Orler great grief. How was that possible? The young man was of fine descent: the renowned Jewish scholar R' Moyshe Rapoport on his father's side and the prominent “Moyre-hoyroe” (rabbi and judge) R' Yoynosen (Yonathan) on his mother's side. With such a clever mind and great abilities, how could it be that such a boy was not among the best in the class?

So Shyele did not actually become a rabbi. But he still became famous in the Jewish world, no less than a great rabbi.

At the yeshiva, they celebrated only one holiday: Purim. In the evening, the yeshiva students gathered with R' Shimen-Zelig at the head of the group. The Megillah was read, Haman's name was loudly knocked out, and after singing a series of songs appropriate for the occasion, such as “Sheshate Yaakov”[10], “Asher heni'a atzat goyim”[11] and others, everyone enjoyed honey cake and schnapps. We spent the time this way until late in the evening.

A week before Passover and a week before the Days of Awe, the yeshiva was usually deserted by its students. Some traveled to the cities in covered wagons, others took the “kolye” [local train]–they would lie down under the benches. If one of them was caught, nothing bad was done to him, God forbid. The inspector recognized who he was dealing with… Such a person would be taken out at the nearest train station, and that was it!

No one was deterred, and the “freeloader” waited briefly for the next train to arrive and… crawled back under the bench again. They laboriously made their way home this way.

Immediately after the Days of Awe, the bustle of arriving students, both old and new, with their meager luggage, prevailed once again. The new arrivals would seek advice from the “old” students to find opportunities for “esn teg”[12] and places to sleep.

Those with “practical experience” [mentors] helped them with advice and assistance, and everyone was well cared for: no boy had to go hungry and no one had to sleep on the street. There was nothing to complain about; one could rely on our pious providers. They would never abandon a Jewish student!

On this occasion, it is worth dedicating a few sentences to the couple who ran a small booth at the entrance to the talmetoyre and in the courtyard of the yeshiva.

Their goods consisted of cheap sweets such as rock candy, caramel, Penitzer honey cake, kernels, peanuts, cooked peas, and buckwheat pudding. You could have bought the entire little shop for five rubles and still had change left over…

This shows what kind of “wealthy persons” they were.

Despite this, they had compassion for poor orphans and children with physical disabilities who were simply unhappy. They knew all the children well. When child who had been sent away came to “borrow” a piece of honey cake or buckwheat pudding, they did not turn him away, even though they knew in advance that they would not get the penny back. Often, the woman herself would call a poor, depressed boy over and offer him a snack from her little shop.

Years have passed since then, and the talmetoyre and the yeshiva have survived Russian rule, German occupation, and, most recently, the Polish “White Eagle.”

Despite all obstacles, the Torah institutions on the broad Pyaskes remained firmly established. During the last years of Polish rule, the yeshiva continued to expand. According to a Polish government decree, “limed-khuts” [secular subjects] were introduced for a few hours a day so that students could perfect their command of the official language, Polish.

I believe I visited the yeshiva for the last time in 1924 or 1925. I no longer remember which event was celebrated there with the participation of HaRav Meir Rapoport (the Bialystok city maggid who later died in New York) and other city dignitaries.

As was his custom, HaRav Rapoport gave a successful sermon on the occasion of the day. Other Orthodox leaders gave speeches as well, and everyone enjoyed spending several hours together at tables set up in the yeshiva courtyard.

I had the pleasure of speaking with the dear, energetic R' Shimen Zelig, who told me that, due to the expansion of the talmetoyre and the yeshiva, he no longer worked on two “fronts.” He was now only a rabbinical supervisor, which was enough work for him.

I met the new head of the yeshiva, HaRav Yukht. He was a young man full of knowledge and inspiration, and he had a reputation as a genius. When I told him that I had once been a student there, he wouldn't leave me alone. He introduced me to the boys in the higher classes. Some of the boys weren't lazy and “took me to task.” They had just learned the “Massekhet Shabbat” [a Talmud tractate on the rules of Shabbat], which I remembered well. Thanks to that, I emerged from the “Gemara battle” with honor.

Unfortunately, all of these Torah institutions, as well as the entire city of Bialystok and its “beautiful” Jews, were destroyed by the Nazi murderers in every cruel way imaginable.

[Page 56]

|

|

[This photograph was edited by Dr. Tomek Wisniewski, The Place, Bialystok] |

Translator's notes:

by M. Sirota

Translated by Beate Schützmann-Krebs

English Proofreading by Dr. Susan Kingsley Pasquariella

During Tsar Nicholas II's reign, the Jews of Bialystok were indifferent to sports, which were underdeveloped at the time. Young men who participated in athletics were frowned upon. After all, it is expressly written: “HaKol kol Ya'akov ve-haYadayim yedei Esav,” which means: “Jews must let the voice of the Torah be heard, but rough hands are a matter for Esau.”

However, there were young men who were weak in Hebrew, did not study the Khumesh [Pentateuch], and consequently did not understand the deeper meaning of a verse from the Tanakh… Thus, Bialystok was destined to have “athletes” in its ranks. The first of these was H. Osinski, a medium-height brunette with a prominent neck. He was regarded in the city as the second “Samson the Hero.” He could lift barbells weighing 40–50 kilograms with ease, as if they were made of wood rather than iron…

Young boys used to whisper to each other, “That man has a tire on his stomach, which is why he's so strong.” His main passion was fighting with sturdy buddies and even professional athletes.

Thanks to his initiative, a larger group of strong boys formed, all of whom wanted to perfect the rules of boxing and similar sports. He taught them how to compete with experienced athletes and which parts of the body could be injured and which must not be touched. Above all, he emphasized knowing when to throw the right punch and, most importantly, how to protect your head because without it, you are lost.

The group listened attentively to their leader's instructions and adhered to the necessary rules. Although they did not organize any public appearances, they arranged various private athletic competitions.

Osinski often participated in public wrestling matches with professional athletes, occasionally showing how he could put a famous champion on his back. Honestly, it didn't happen often, but he made his opponents feel his strong fists in every fight. He was familiar with all the international champions, who considered him their equal. One could boldly claim that he was the pioneer of Jewish athleticism in Bialystok.

Another Jew with a reputation as an athlete was the blond, rosy-cheeked Motl Ostrinski. He could also lift heavy weights. When he shook hands with a good friend, the friend would actually jump up in pain. But this was a casual matter. His main specialty was fighting fires.

He was an important member of a volunteer fire department called “Pervi Ladotshnik.” Although he did not have a career like his brother Litman, a respected “natshalnik” [boss], he was no less popular in the city than his brother, the commander.

When fighting a fire, he was always in the most dangerous positions, showing dedication and self-sacrifice by rescuing people. He also contributed greatly to preventing the fire from spreading.

It should be noted that, unlike today, firefighting equipment could not be raised to the necessary height, so firefighters often had to climb steep walls because they had no ladders. In such cases, M. Ostrinksi was in the right place at the right time.

He listed a series of awards and medals for his work as his own and secured a place of honor on the volunteer fire department's honor roll. Like his older comrade Osinski, M. Ostrinski had a soft spot for athletics. Whenever international champions toured the circus, the director would ask if any amateurs wanted to compete against one of the champions. M. Ostrinski would immediately register.

I didn't count how many champions he knocked out. But competing against a tough, well-fed champion was heroic in itself.

During his most successful years, he traveled to America but often longed to return home to see his family and his many friends in the fire department. He often came to Bialystok on vacation.

I remember that during one of his last visits, an extraordinary, dramatic incident occurred.

It was a gloomy morning in late summer. I don't remember exactly if it was 1923 or 1924. After several days of incessant rain, the quiet little Biala River suddenly rose and flooded several streets, including Bialostoshaner, Gumyener, Yatke, and others, in just a few hours.

[Page 58]

Nikolayevske Street was an impressive sight. It was flooded on one side up to Mets's pastry shop and on the other side up to Alter Turme [Old Prison] Street. The narrow Nadretshne Street, also known as Sevastopolyer Street, was particularly badly affected and completely submerged in water.

A rescue operation was immediately organized to help people and pets escape their flooded homes, retrieve Jewish belongings from flooded basements, and collect random floating possessions.

Motl Ostrinski proved at that time that he was skilled not only with fire but also with floods. He quickly hammered together a makeshift raft out of wooden boards and used pegs as oars to reach the most dangerous places, where he provided necessary assistance.

Soon after, boats also appeared, and other courageous individuals used them to provide assistance wherever needed. They rescued Jewish property that had floated to the non-Jewish side.

The sun did not come out until evening, when the Biala River gradually receded back into its normal riverbed.

For weeks, Jews talked about this event, which could have ended tragically if not for the rescue operation led by energetic individuals, with M. Ostrinski being the most active participant.

Since then, people no longer looked down on the Biala River. The saying “beware of still waters” revealed its true meaning.

Shelyepski, the “gazetshtshik” (newspaper seller) of Russian newspapers in Bialystok, was considered a hero, as well. Broad-shouldered with light brown hair, he stood next to the “Shisl,” right in the center of the city on the corner of Lipova Street, overlooking Nikolayevske Street.

The hated policeman, V. I. Reshuta, also “resided” there, and Jews trembled in mortal fear of him. At his thunderous “razaydites!” (disperse!), people used to run away headlong as far as they could.

The only Jew Reshuta tolerated was Shelyepski. He was friendly toward him and even offered him a “makhorka” cigarette [ made from coarsely cut tobacco].

Like Reshuta, the “gazetshtshik” had a coarse, deep voice. When he shouted “Rus,” “Retsh,” “Novosti,” “Birzhevye Vyedomosti,” or “Ruskaya Misil” (all of which were St. Petersburg and Moscow newspapers that arrived in Bialystok), his voice echoed all the way to the Gorodski Sod [City Garden].

Reshuta was always afraid that one day his own “Razaydites” would not be heard over Shelyepski's thunderous cries. So he used to ask Shelyepski, “Golubtshik, po tishe” [My dear, be a little quieter!].

I was told that Reshuta once talked to his “neighbor” Shelyepski and tried to persuade him to convert.

”Follow me,” he said. “You look like a real Russian. You sell Russian goods, you eat Russian bread. You're educated and politically correct. You don't even go to the synagogue on Shabbat. What good does it do you to remain a Starozakonik [adherent to the backward law]? If you become one of us, a Pravoslavner [Russian Orthodox Christian], you can have a solid career in the police force. You could even become a Starshi Strazhnik [high-ranking police officer].”

Shelyepski is said to have replied in perfect Russian: “What good does it do to scream your lungs out day in and day out, ‘Razaydites,’ and deal with ‘kramalnikes’ [troublemakers]? Jewish people will not be lost. The caretaker position at the Bagnowka Cemetery is currently vacant, and you could get the job. You would have an income and a secure life!”…

I cannot guarantee the authenticity of the dialogue. I am only passing on what I was told, but the dialogue is characteristic in itself.

Shelyepski did not look Jewish, but he certainly had a Jewish heart. He refused to distribute the anti-Semitic newspaper Novoye Vremye [New Time], even though it had promised him a bonus. He was often a guest at Jewish events in the “Garmonye” hall.

However, he was most attracted to the wrestling matches at the circus, where he was a familiar guest. When an athlete challenged him, he would wrestle with them. Without hesitation, he entered the ring and demonstrated his skillful use of strength. It was rare that an athlete managed to defeat him.

A group of famous international female athletes, led by Ms. Podlubni, who weighed 110 kilograms, came by on their tour once. Among them was Rozenberg, a German woman and champion who was considered one of the weakest.

One evening at a packed circus, Rozenberg turned to the audience and asked if anyone would like to compete against her. If they defeated her, they would receive a prize.

Shelyepski stood up and volunteered. After a fight lasting just under ten minutes, amid the audience's general laughter, Rozenberg threw Shelyepski “on his back.” From then on, Shelyepski avoided competing against female athletes…

[Page 59]

During World War I, when the Russian military withdrew from Bialystok, the “gazetshtshik” Shelyepski disappeared from the scene. He thought he wouldn't have anything left to do there if there were no more Russian newspapers. Come on, he surely wouldn't go to become a mezuzah-and-tefillin scribe…

Now, a few more words about the Bialystok circus. I don't remember exactly when it was built. I only know that it was made of old wood and also served as a theater where well-known Russian and Ukrainian troupes performed. One fine evening, the circus burned down. I no longer remember the date or the cause of the fire.

In addition to the recognized “heroes,” such as the troika of Osinski, Ostrinski, and Shelyepski, Bialystok had quite a few strong and powerful men, or what could be called “gray heroes without epaulettes.” They never competed with athletes, but they did lift heavy loads – not as a sport, but because their jobs required it. They were porters, or as they were called, “pakirer.”

They used their strong, bony hands and shoulders to earn a living. Before the First World War, the lives of Jewish porters were hard and sad. Poverty and deprivation were evident everywhere. A small number of them sought solace in “bitter drops.” The carter Bendet often embodied this when he was found lying in the gutter. “You have to chase away your worries,” he told himself each time. “Because if you don't, you'll burst!”

And so he lay in the gutter until he fell asleep. His colleagues took him home…

In the summer heat and in winter blizzards, snow, and frost, one could see Jewish porters waiting for customers with a rope tied around their waists.

Often, you would meet an elderly porter with a 30–40-kilogram bundle on his shoulder, nearly collapsing under the weight until he delivered it to the right address.

The fate of Jewish porters under the Tsarist regime was dire. Their situation got even worse when Bialystok was occupied by [Emperor] Wilhelm's armies. There was little need for porters at that time, as there was hardly anything to carry. All goods had been confiscated, and the “Commander-in-Chief of the East” possessed everything.

Most of the “pakirer” had no choice but to hire themselves out to the Germans for two Ostmarks per 12-hour workday. For this meager wage, they were forced to load goods and haul wood demanded by the new rulers, who confiscated or stole it. Fortunately, all things must come to an end, including the reign of “Wilhelm's rulers” in Bialystok.

Following the defeat of the “Yekkes,” the situation of Jewish porters improved. A “Union of Transport Workers” was organized, including porters, wagon drivers, and coachmen. Each branch had its own tasks and functions. For instance, wagon and coachmen were not permitted to carry water; that was the porter's responsibility. Great care was taken to ensure that no one encroached on another's area of responsibility.

The “transport workers” had supportive allies on the executive committees of the political workers' parties, particularly the Bund. These guides introduced the transport workers to the principles of socialism and taught them about class struggle and exploitation.

The porters listened to the speeches with great attention and admired the “worker sympathizers” for their knowledge and fluency.

At that time, preparations were being made for the elections of a democratic Jewish community. All political parties tried to win as many votes as possible and did not skimp on agitation…

The “pakirer,” who carried many burdens, were ideal “material” for the most popular workers' party, the Bund. The older people liked a certain speaker's words that “Moyshe-rabeyne” [the biblical Moses] had been a revolutionary and an opponent of capitalists and bloodsuckers. If “Moyshe-rabeyne” himself had preached such speeches, then surely an honest Jew could follow in his footsteps…

As mentioned above, wagon and coachmen were considered “transport workers.” During the Tsarist regime, they enjoyed privileges over porters. They did not have to exert themselves too much because horses did the work for them…

Fate took its revenge on them during the days under the “Yekkes” in World War I because nothing could be confiscated from a porter since he had nothing but poverty… Conversely, the “breadwinners” of the wagon and coachmen could be confiscated–namely, the horses.

Only old and weak animals were left to them.

[Page 60]

Very few of those who kept a “piece of horse” continued to work in their fields. However, most were forced to hire themselves out to work for the Germans. They had to carry heavy loads, such as tracks, by hand.

After the defeat of the “Yekkes” and the establishment of the “Transport Workers” branch, they were reinstated as well. Delegates from the American Joint Distribution Committee and Relief, led by the secretary of the Bialystoker Relief, David Sohn, brought huge sums of money from relatives and seamless assistance.

As a result, some were able to buy horses and carts again, while others bought horses and fine carriages. They returned “up on their horses.”

Unlike the porters, however, the coachmen did not embrace the teachings of socialism.

They did not understand strange words like “class struggle” and “exploitation” at all. In their opinion, a coachman had to fight his customer to earn a few “gildn” from him.

Even more difficult for them to understand was the strange, difficult-to-pronounce word: ekspluatotsye [exploitation]. Someone translated it for them as “squeezing the juice out of a living being.”

Did that also mean that they were exploiting their horses?! If so, that would be the end of the world! They needed to make them understand that, to a coachman, his horse is as valuable as his wife–perhaps even more so. He would never go to eat before his “chestnut brown” had gotten his food. Why were these people making such a fuss with such clumsy words?

Most coachmen weren't interested in social or societal issues. They had to take care of their horses and keep the coaches and sleighs in proper condition. They often had to be washed and cleaned so that they shone.

So, who had time for such matters?

Since they were always out in the fresh air, they had good appetites and believed in the saying, “Akhile iz di beste tefile” [Food is the best prayer].

For one of them, a whole roast goose was not too much. He could also eat gefilte kishke (stuffed intestines) and sip a dozen drinks.

Outsiders who observed this found it quite natural. It was well known that these well-fed, strong fellows, along with the wagon drivers and porters, formed a protective barrier against enemies of the Jewish people. In their district of Khanaykes, with its poor streets, hooligans never attacked Jews. This applied both during the 1906 pogrom and when the “Polyakn” [non-Jewish Poles] recaptured Bialystok in 1920, robbing Jews everywhere or seizing them at their working places.

In this district, they knew it wasn't worth the risk because they could get beaten so badly that they would remember it for the rest of their lives.

During my time working as a journalist in Bialystok, I often rode around the city in a carriage or sleigh to see what was new in town. I knew the wagon drivers had juicy stories to tell and wanted to use them in my newspaper articles. I tried a few times to “squeeze” something out of them.

But they always answered, “It won't work,” or “We don't know anything…”

One of them, a somewhat more enlightened individual, once explained to me “philosophically”: “If my carriage with its rubber wheels could talk, or if my sleigh with its bells could speak a language, they would have a lot to tell you. You would have material for an entire newspaper… But we are just like our horses. We have eyes that see, ears that hear, but we have to keep our mouths shut because of the ticks… that's our professional secret!”---

Throughout the whole year, the coachmen, like their colleagues, the wagon drivers, did not usually think about the “afterlife” and sinned in advance for the “al-khets” [prayers of repentance on Yom Kippur]. After all, HE also gave man an evil inclination, from which he finds it difficult to break free. Well, it's easy to commit a little sin without meaning to; evil swear words and curses slip out of your mouth, and sometimes your blood boils and you end up giving someone a “gift with your hand” [a slap in the face], for which you don't apologize afterwards…

But then, as the Days of Awe approached–for the shofar could already be heard blowing from the shuln and kloyzn–their outer shell fell away, as if they had suddenly sobered up. The heroic men became like lambs, came to the bote-medroshim, and recited the prayers with religious fervor together with their fathers. They also did not fail to throw a leftover kopeck into the collection box of the “Rabbi Meir Baal HaNes [Rabbi Nehorai] Talmud Torah” and others.

The culmination point was the eve of Yom Kippur, when the coachmen went around apologizing, some quietly and others groaning. They asked each other for forgiveness and wished each other that they might experience a [new] year with their wives and children, that the horse might remain healthy, and that there might be enough income…

Translator's notes:

|

by Sheftel Zak

Translated by Beate Schützmann-Krebs

English Proofreading by Dr. Susan Kingsley Pasquariella

Białystok was among the rare provincial towns where a Jewish troupe, during the German occupation in the First World War, could find a brief resting place for several weeks.

But here one had to overcome various difficulties. First, in order to enter the so-called Ober-Ost district, one needed a special permit, which was not as easily obtained as in the Austrian occupation zone. Secondly, there was the problem of securing a theater building.

In the only Palace Theater, which belonged to the Jewish directors German and Gurvitsh, various troupes performed at the time: Russian, Polish, and the German theater for the Eastern Front. In the Palace, there were also various celebrations, gatherings, and concerts. Nevertheless, Jewish actors found ways to manage even these problems, and for weeks they had the opportunity to perform in Białystok.

The economic situation there at that time was very difficult. The Germans requisitioned the large Białystok manufacturing factories, and the workers were exploited in a dreadful manner. In the smaller workshops, raw materials ran out, and they often came to a standstill. The majority of the Jewish population suffered from hunger and hardship.

But Jewish Białystok did not succumb to the pressure of the times, did not fall into apathy, and found a sense of fulfillment in the intensified and active Jewish cultural activity, which was led by the association Jewish Art.

This association had three sections: a dramatic, a musical, and a literary one.

The musical-vocal section also had a choir of 70 people. The conductor was Pesach Kaplan – later the editor and theater critic of the Białystok daily newspaper Unser Leben.

The dramatic section was led by the writer and teacher Yakov Pat. Both sections often organized public performances in the Palace Theater, which regularly drew large audiences.

In the premises of Jewish Art, evening discussions were held on various topics, as well as lectures by local writers – and also guests from Warsaw.

There was also a second active cultural society, Hazamir [the Nightingale], led by L. Treyvish and A. Albek. Hazamir was especially distinguished by its large and excellent orchestra.

This Jewish creative atmosphere created a favorable climate for Yiddish theater, even in those difficult times.

On the horizon of Yiddish theater, the Vilner Troupe appeared – setting out on tour after more than a year of preparatory work in Vilna. Their first guest performances were given by the “Vilner” in Grodno and in Białystok, only later in Warsaw and other cities of Congress Poland.

For over a month, the Kaminska Troupe performed in Białystok with considerable success, and there they gained many new friends and admirers.

A list of the troupes that performed in Białystok during the war years and the transitional period is the best testimony to the importance of the position that Yiddish theater held in this city at the time – despite all kinds of difficulties and obstacles.

Besides the Vilner and the Kaminska Troupe, the following also performed in occupied and later liberated Białystok:

– The Warsaw Yiddish Operetta Troupe, under the direction of Aba Kompanyeyets;

– The Warsaw Theater of Comedies and Farces, directed by David Tselmeyster, featuring the artists: Hershl Yedwab, Ida Ervest, Pesach'ke Burstein, and the dancers Lyola Greshov and Slawinski.

– A [special] attraction were the monologues on current topics, performed by Hershl Yedwab. These monologues, written especially for Yedwab, always hit the mark with precision. Their author was Yosef Shimen Goldshteyn.

– The Warsaw Central Theater, with an operetta repertoire, under the direction of Sh. Landau;

– The First United Operetta Troupe, led by the soubrette Betty Koenig and Adolf Berman.

At the beginning of 1918, the troupe from the Lodzer Grand Theater came to Białystok, under the direction of Julius Adler (a native son of Białystok) and Herman Sieradzki.

The ensemble consisted of a number of well-known actors of that time. The orchestra was conducted by David Beygelman.

They performed in Białystok for an extended period with great success, presenting a varied repertoire: Uriel Acosta by Karl Gutzkow; The Girl Scout by Julius Adler; Alma Vu Voynst Du [ Alma, Where Do You Live?], Yeshive Bokher [The Yeshiva Boy], Talmed-Khokhem [The Jewish Scholar], and Di Royz Fun Stambul [The Rose of Istanbul] by Lea Fall, in Y. Adler's translation.

In February 1919, the German occupation of Białystok came to an end. The city passed into the hands of the Polish authorities.

The first “honeymoon weeks” of Polish rule were accompanied

[Page 62]

by wild antisemitic incitement, physical assaults, and brutal harassment of Jews.

As for performing Yiddish theater – there could be no talk of it.

But as the political and economic situation gradually began to normalize, posters of Yiddish troupes started to appear in the streets – though not a single Yiddish letter could be seen on them. The new authorities had strictly forbidden it.

Only months later was the decree finally lifted.

In the Palace Theater, the Vilner Troupe returned for another guest engagement, this time with a changed lineup. And although public interest in their performances was again considerable, the success was far from what it had been during their first tour.

The Adler–Sieradzki Troupe also returned to Białystok, and their new repertoire once again drew audiences to the theater. They performed Cain by Alexandre Dumas, Shoshana di Tsnue [Shoshana the Virtuos] by Gilbert, Dos Idishe Harts [The Jewish Heart] by Lateiner, and the melodrama that was very popular at the time – Gelt, Libe un Shande [ Money, Love, and Shame].

On Lipowa Street, number 18, in a venue called Lux, a Yiddish miniature theater opened around the same time, featuring actors from Warsaw and Łódź: Shloyme Kutner, Pesach'ke Burstein, Ida Ervest, Kroyze-Miler, and a dance ensemble.

Although the management had promised in its first announcements that “it would take every measure to shape the theater according to the standards of the finest European miniature stages”, the repertoire soon revealed that the promise had been nothing but an empty phrase.

They performed various shund one-acts, most of them written by Kutner himself, and the couplets and songs were of no better quality.

Still, the public came gladly to see the marvelously character actor Shloyme Kutner, and the singing, dancing Pesach'ke Burstein, who quickly became the “lyubimyets publiki” – the darling of the audience.

The miniature theater remained active in Białystok for quite some time.

In the summer of 1919, the renowned actor of the Russian stage, L. Sniegov, made his Yiddish debut in Białystok. His guest performances caused a veritable sensation in the city.

The Białystok daily Dos Naye Lebn [The New Life] valued Sniegov's Yiddish appearances as a major event, writing: “The Vilner have carved a door into Europe for Yiddish theater, and through it have entered artists like L. Sniegov and Naomi.”

The Białystok actors, who frequently performed light-genre productions both in the city and throughout the provinces, organized themselves at that time into a permanent ensemble under the name Artistish Vinkele [Artistic Corner].

Dos Naye Lebn welcomed the initiative of “the more self-aware Białystok actors” – Yehuda Grinhoyz, Lifshits, Hershberg, Meir Schwartz, Sholem Schwartz, Dorina, and others – “to create their own Artistic Corner. Di Puste Kretshme [The Empty Tavern] and A Farvorfn Vinkl [A Remote Corner]– recently performed by our Białystok players – showed clearly how deeply they had been influenced by the more serious Yiddish troupes we had seen here, especially the Vilner.”

In the winter season of 1919, two Yiddish troupes began performing in Białystok. At the Palace Theater, the ensemble Jewish Artistic Drama took the stage, under the direction of A. Azro and L. Sniegov. The company included already well-known actors: Sonya Alomis, Leyzer Zhelaza, Lea Naomi, Orzhevska, and others.

Their repertoire featured: Der Foter [The Father], Di Puste Kretshme [The Empty Tavern], Di Nevole [The Scandal], Mirele Efrat, Di Harbst-Fidlen [The Autumn Fiddles], and Di Teg Fun unzer Leben [The Days of Our Lives].

At the Mozaika Hall, a vaudeville theater performed under the direction of Salomon Kustin, with the actors: Rita Grey, Jaffe, Mania Shein, Regina Boyman, M. Schwartz, and Pesach'ke Burstein.

Their repertoire included: Ven Esn Vayber [When Women Eat], A Man, A Shmate [A Man Like a Rag], Di barimte Komedye [The Famous Comedy], and Mendel Beilis. To the Komedyes un Farsn [Comedies and Farces], a concert of songs and couplets was usually added.

Dos Naye Lebn took a sharp stance against the kind of vaudeville productions “that were thrown together in a day or two.” The newspaper pointed out that “the performances by the Vilner troupe and other leading ensembles had clearly shown that the public yearned for something finer and more beautiful.”

And yet, Białystok also had an audience for the vaudeville theater – proof being that two shows were performed each evening.

This flourishing Yiddish theater scene provoked sorrow and anger among the Polish city authorities, who had only recently come to power. Suddenly, serious obstacles arose in obtaining permission to stage Yiddish theater. Heavy taxes were imposed on theater tickets, and the Polish newspaper Dziennik Białostocki kept up a steady campaign against Yiddish posters.

In the infamously antisemitic Warsaw newspaper Dwa Grosze (“Two Groschen”), a correspondent from Białystok published the following characteristic lines:

“…While Polish society fights with self-sacrifice for its patriotic duties, the Jews indulge imperially in their theaters. On Yiddish posters, there is barely a small portion in Polish – the rest is in jargon, printed in enormous Jewish letters.”

The Jews of Białystok barely endured these vile provocations and denunciations, whose sole motive was envy.

More than ever before, they continued their struggle for political rights, for relief from economic hardship, and for the fulfillment of the cultural needs of the Jewish population.

Yiddish theater posters never disappeared

[Page 63]

from the streets of Białystok. The Yiddish theater – the living Yiddish word – stimulated the broader Jewish public, even in an organized way, to demand that the titles of foreign films be posted in Yiddish as well.

Białystok produced a number of important Yiddish actors, among them: the beloved actor and singer Yehuda Grinhoyz; the renowned and distinguished actor and director of the Habima theater, Yisroel Beker, who also successfully produced several films; the heartfelt singer and actor Yakov Suzanovitsh; the well-known actor-director and long-time leader of his own troupe, Zalmen Koleshnikov; the talented actress Renie Glikman; the celebrated and beloved performers Esther Zevkina and Yisroel Birnboym, who for many years led the Yiddish theater in Paris; the gifted and refined singer and actor Shimen Asovitski; Yitskhok Geltshinski, Nina Sibirtsova, and others.

|

|

[We learn from the “Bialystoker Photo Album,” p. 126, that from right to left, top, are to see: Icht, Kowalewsky, Knishinsky, Gelchinsky (America), L. Gaz, Wilenchik, Shulsinger, Miss Shwetz, Newadowsky, Niedoff (New York), M. Gaz, Katenko, W. Bubrik (Associate Dramatic Director), N. Perelman (Director), Mrs. Silverstein, M. Schwiff (Chairman), Miss Kopelman, I. Fried (Vice-Chairman), Mrs. Abeloff, I. Topitzer (Associate Dramatic Director), M. Berkman (Musical Director), Nina Sibirtzewa (America), M. Goldman (Russia).] |

Toward the end of the 1920s, a small-stage theater emerged in Białystok under the name Gilorina (גילה רינה), which was supported by grassroots social forces.

The initiators and founders of this theater were two young men: Viktor Bubrik and Tepitser. Its financial foundation came primarily from the Białystoker Linas Hatzedek.

The first program consisted of humorous Russian material, translated into Yiddish by writers such as Pesach Kaplan, Mendl Goldman, Shteynsapir, and others.

The musical director was M. Berman, and the [stage] painter was Rozanyetski.

Gilorina performed successfully, and instead of making use of translations, the troupe shifted toward folk repertoire and sketches on current themes.

The actors Yehuda Grinhoyz, Sheftel Zak, and Hersh Floym organized a stable cooperative troupe in Białystok, based in the Palace Theater, and systematically invited guest performers.

For over five years, the troupe performed in Białystok and also served some twenty towns and small cities in the surrounding province.

The first season, 1931–32, was a great success. A Committee of Friends of the Yiddish Theater was formed, headed by editor Pesach Kaplan, engineer Borash [Barash?] – director of the Jewish community – Binyamin Tabatshinski, and others.

B. Tabatshinski, as a long-standing member of the Białystok city council, successfully campaigned for the troupe several subsidies from the magistrate as well as a reduction in municipal taxes.

This significantly strengthened the financial position of the cooperative troupe.

For the second season, the long-time theater activist Yosef Vayshof joined as the administrative director. His wife, the actress Berta Litvina, also joined the troupe.

The system of guest performances, which is generally not particularly healthy for the development of a theater, nevertheless had, in this case, the advantage that the guest actor – depending, of course, on their artistic caliber and popularity – sparked special interest among the public and also helped solve the repertoire question, which is so crucial for a city that isn't too large, where new plays must be offered quite frequently.

Thus, Jewish Białystok at that time truly had the opportunity to see the most distinguished Yiddish artists in a number of interesting and modern productions.

Guest performers included: Ayzik Samberg, Zygmunt Turkov, Ida Kaminska, Yonas Turkov and Diana Blumenfeld, Tsili Adler, Kurt Katsh, Dina Halpern and Sam Bronetski, Moris Lampe and Rose Shoshana, Simkhe Natan, Maurice Schwartz with his troupe, David Zeiderman and Khana Lerner, S. Goldberg, Shloyme Prizament and Gizi Hayden, Vyera Konyevska and Paul Breytman, Regina Zucker and Karl Zimbalist, Jenny Lovitsh and Khayim Levin, Ben-Zion Witler, Jack Rechtzeit, Irving Jacobson, Pesach'ke Burstein, Alexander Granach, Anna and Heymi Yakobovitsh, among others.

The Białystok press and the broader public warmly appreciated the work of the stable ensemble, which provided spiritual enjoyment even to the Jews of the towns and small cities surrounding Białystok.

When Białystok was occupied by the Soviets during the Second World War, an artistic Yiddish state theater was organized in the Palace Theater, which operated on a very high level.

In June 1941, the theater set out on its summer tour, which began in Mohlyev [Mogilev] on the Dnieper River. There, the theater was overtaken by the new war, when Hitler launched his attack on Soviet Russia.

Translator's notes:

by Pinchas Ginzburg

Translated by Beate Schützmann-Krebs

English Proofreading by Dr. Susan Kingsley Pasquariella

In 1918, a group was formed under the name Maccabi[3], training at the premises of Linas Hatzedek. (No official permit had been granted by the Polish authorities.)

Some time later, a split occurred, and a second group– Rekord – was founded, with its premises located on the market square at Kościuszko.

In 1920, by order of the authorities, the activities had to be discontinued. Following this, members Simkhe Levin and Pinchas Ginzburg made efforts to obtain official recognition from the authorities under the name Maccabi.

Between six and eight petitions were submitted, each signed by ten prominent and responsible individuals. Each time, the authorities invalidated one or another signature. When all signatures were finally accepted, the authorities found yet another excuse: they would not permit the name Maccabi.

The final petition was submitted under the name: Jewish Sports Club in Białystok (ISK).

Obtaining official permission took more than two years. In 1921–1922, under the responsibility and guarantee of Yakov Beker (a well-known leather manufacturer) and Shimen Sokolski, a location was rented on Nadretshna Street.

Immediately, sections were organized for gymnastics, football, track and field, and cycling.

A series of public football matches were held with players such as David Plavski, Samulke Halpern, Refelski, David Gotlib, and Misha Vargaftik at the helm. A massive cycling parade – with several hundred cyclists –rode through the city's main streets under the leadership of Leyzer Plavski.

In the year 1922, by order of the authorities, the plan had to be abandoned and the activities discontinued.

Shimen Sokolski then gave up several rooms in his stone building, where the café Lux was located. It was there that members gathered, and all secret discussions were held.

In June 1923, ISK was finally legalized. Yakov Beker became chairman, and Shimen Sokolski vice-chairman.

A plot was immediately rented on Branicki Street, next to Yafe's school. Thanks to the tireless and colossal efforts of a group of active members, an excellent sports ground was created in a short time – for gymnastics, track and field, football, and tennis.

The members Sh. Levin, P. Ginzburg, and also Pesach Pomerants (who had just returned from Kovno), together with Y. Beker and Sh. Sokolski, worked to draw wealthy individuals into the ranks of ISK – such as Novik, Triling, Yanovski, and others – with the aim (or perhaps the dream) of establishing the club on a truly grand scale.

Public performances and appearances were then frequently organized across all areas of sport. Almost the entire Jewish population became deeply interested and was drawn into the club's orbit.

Beyond the administration, a large technical council of 20–30 people was formed. It included the Meler brothers (construction entrepreneurs), the Plavski brothers, the Krinski brothers (paint business), the Freydkin brothers (cloth factory), with Henokh Slon at the helm.

In the early days, the major industrialists often attended the administration's meetings, and even a considerable sum of money was raised. But this did not last long. The prominent figures began to lose interest, stopped attending the meetings, and no longer showed up at the sports ground.

Already at that time, members P. Pomerants and P. Ginzburg were circulating plans to remove the prominent figures and establish a new administration composed of the most active members. Sh. Levin did everything in his power to persuade and influence them not to proceed, hoping the prominent figures would still continue to work and contribute to the club.

In 1924, a major undertaking was carried out: the arrival of the world-famous Viennese Hakoyekh [HaKoakh, The Power]. It is worth noting that by three in the morning, the entire population was already on its feet, streaming toward the train station.

The entire club – with its administration at the forefront, in uniform and bearing the club's flag – marched out from its grounds to greet and welcome the distinguished guests at the station, accompanied by the sounds of orchestral music.

From two in the afternoon until after the match, the city was deserted – not even a single droshke could be found. And in 1925, the Viennese HaKoakh was invited again, this time alongside Brno [Brünn] Maccabi and Palestinian Maccabi.

In 1926, a secret meeting of the club's most active members took place in the apartment of P. Ginzburg. It was decided to call a general assembly, and a list for a new administration was drawn up.

Sh. Sokolski became chairman. ISK once again resumed its work with intensity and displayed vigorous activity.

On the initiative of P. Ginzburg, secretary of the administration and head of the football section, the city's well-known youth football team

[Page 65]

was then brought into the section – under the name of Gershon Lyach, who served as captain. In a short time, thanks to their brilliant play, they pushed out all the older players.

It was an excellent experiment.

In the year 1927, due to the departure of Sh. Sokolski, Avraham Knyazev (administrator of the Jewish hospital) was elected chairman, and Henrikh Zebin, director of the Manufacturers' Association, was elected vice-chairman.

A. Knyazev proved to be the most capable and effective chairman in the entire history of the Jewish sports club.

|

|

In the year 1927, following the departure of Sh. Sokolski, Avraham Knyazev (administrator of the Jewish hospital) was elected chairman, and Henrikh Zebin, director of the Manufacturers' Association, was elected vice-chairman.

A. Knyazev proved to be the most capable and effective chairman in the entire history of the Jewish sports club.

In 1928, the official five-year existence of ISK (1923–1928) and the ten-year anniversary of the Jewish sports movement were celebrated.

A jubilee committee was formed, consisting of: Dr. Reygrodski, editor Pesach Kaplan, Dr. Volf, Dr. Shatski, engineer Mordekhay Zabludovski, engineer Ratski, Vider, and others.

On the eve of Shavuot, a splendid torchlight procession took place, accompanied by orchestral music. Around 500 members and sympathizers took part.

On the first morning of Shavuot, the entire club – section by section – assembled on its grounds in a formation shaped like the Hebrew letter “?” [chet]. At the center stood the jubilee committee and the club's administration. Speeches were delivered, and tokens were distributed to the most active contributors and best athletes.

Members Sh. Levin, P. Pomerants, and P. Ginzburg were the only ones honored with golden tokens.

On both days of Shavuot, competitions were held against Maccabi Grodno – in football and in track and field – at the new municipal stadium in the Zverinyets forest.

Until 1929, ISK had several club premises: within the Merchants' Association, in the stone building of Moyes, at Piser's hall on St. Roch's Street, and elsewhere.

In 1929, ISK had a splendid clubhouse at Gubinski, on the corner of Nay-Velt [New World] Street and Linas Hatzedek Street. The clubhouse was lively and well attended every evening by members and guests. Each night, three to four groups trained – men and women alike.

There was a reading room stocked with Jewish and Polish newspapers from across the country. A chess section was active. Several ping-pong tables brought the club considerable income.

ISK also had its own orchestra, under the direction of its founder, Gershon Lazovski (Lozov).

Between the years 1928 and 1933, ISK displayed its greatest activity. All sections were elevated to the highest level. The club had reached its full splendor and brilliance.

The football section, under the leadership of P. Ginzburg, was extremely popular and renowned throughout Poland, with stars such as Lyakh, Proftiker, Goldfarb, the Fukhatshevski brothers, Fridman, Gold, Faktor, Henokh Yatshmenik, Bulgar, and Berele Zavadski at the forefront.

The section was one of the strongest in the entire eastern region.

The gymnastics section, led by Sh. Levin, stood at a high level and was considered the best in the city. Public gymnastics festivals were organized, and twice the country's finest group – the model team of Warsaw Maccabi – was invited, leaving a powerful impression in Białystok. The track and field section, under the leadership of P. Pomerants; the boxing section, led by the renowned athlete Misha Vargaftik; and the tennis and ping-pong sections – were likewise the strongest and most distinguished in the city.

It is worth mentioning the boxer Kh. Kushner, who was regarded as the best Jewish fighter in all of Poland, and one of the strongest in the entire country.

In 1935, at the Polish championships held in the antisemitic city of Poznań, the judges ruled him into second place. He had earned first place and the title of champion. The entire Polish press shared this opinion.

ISK took great pride in the courageous journey across Europe undertaken by cyclists Zalman Olyanski and Sasha Yutkovski (a dental technician from Krynki). Their bicycle tour – beginning in Poland and continuing through Germany, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, Yugoslavia, Denmark, and other countries – left a powerful impression throughout the country.

The journey lasted six months.

It is worth adding that the bicycles were specially built for them by the well-known Białystoker mechanic and locksmith Meyshke Khemyovitsh, whose workshop was located in the basement on Khaye-Odem [Chaye Adam] Lane – the little alley one used to take on the way to shul [synagogue].

There was also a motorcycling and cycling section,

[Page 66]

under the leadership of the devoted member Nakhman Sukhovolski. Thanks to his effort and energy, the motorcycling and cycling sections became the strongest in our region.

Also in the cultural sphere, ISK stood at a distinguished height. The administration frequently organized member gatherings featuring talks, served tables, lectures, and musical entertainment evenings.

One particularly important and memorable event was the public trial about football, held by ISK in the large hall of Linas Hatzedek. The city's most prominent personalities were drawn in – serving as judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and witnesses both for and against.

The verdict was: Football may indeed be played.

In the year 1933, on the occasion of ISK's tenth anniversary and fifteen years of the Jewish sports movement in Białystok, a grand celebration was once again held – including a torchlight procession, competitions with Vilna Maccabi, and the distribution of diplomas and tokens to the most active contributors and outstanding athletes.

Members Sh. Levin, P. Pomerants, and P. Ginzburg were the only ones decorated with golden medals.

At that time, there were six Jewish sports organizations in Białystok. ISK was the only non-partisan club. Competition among the Jewish clubs had become very intense, and Białystok could no longer sustain them all. The financial situation of the clubs grew more critical by the day. ISK was eventually forced to give up its sports field – a loss that seriously impacted the club's continued activity.

In 1935, representatives of Maccabi approached P. Ginzburg with a proposal to unite under the name ISK Maccabi, with the goal of promoting pure sport, free of party politics.

One of the Maccabi representatives, Tsale Frenkel, seeing no other way forward, persuaded P. Ginzburg – for whom the sports movement was dear and beloved – to reach an understanding with ISK members Isak Levin, engineer R. Ratski, Isak Ribalovski, and Y. Profitker. Several secret meetings were held with members sympathetic to the idea.

At the beginning of 1936, stormy general assemblies shook both ISK and Maccabi, with slogans for unification hurled back and forth. Members Sh. Levin, P. Pomerants, Nakhman Sukhovolski, and others fought like lions against it – but could not prevent it.

The first meeting of the new ISK administration – tasked with negotiating and officially carrying out the unification – took place at the home of P. Ginzburg.

A commission was appointed, consisting of Isak Levin, Yakov Profitker, and Pinkhas Ginzburg, who officially and definitively carried out the historic unification under the name: ISK Maccabi.

Avraham Sakal (the prominent industrialist) was invited to serve as chairman, and the well-known and beloved communal activist from Linas Hatzedek, Zeydl Frid, as vice-chairman.

P. Ginzburg was elected secretary of the administration and head of the most popular and strongest unified football section.

A large venue was rented, and in the years 1936–1937, competitions in football and track and field were organized with participation from all Jewish clubs across Poland. Białystok had never before hosted events of such scale. These competitions became known as the “Little Olympiad.”

The entire population was thrilled, and the event made a colossal impression.

In 1938, the 20th anniversary of the Jewish sports movement in Białystok was celebrated. The festivities were held in grand fashion, with participation from clubs outside the city. A torchlight procession was also held, and diplomas and tokens were distributed.

P. Ginzburg was the only one to be honored with a golden token.

That same year, the Central Polish Football Association in Warsaw, in connection with its own 20th anniversary, distributed sport commendations to the most active contributors in the field of sport. Only two Jews from all of Poland had the honor of receiving such tokens of recognition. P. Ginzburg was one of the two.

In July 1939, I departed for America and had to part from my beloved creation – ISK Maccabi. The administration, my closest comrades and friends, organized a farewell banquet for me and my family. A series of speeches were delivered, and the club's president, Dr. Treyvish, as a token of appreciation for my contributions, presented me with a silver cigarette case – wishing me and my family a happy and prosperous future in our new homeland.

Our friend Isak Ribalovsky – formerly an active member of the ISK club and now general secretary of the Białystoker Center in New York – provides the following interesting facts:

In 1939, when the Soviet army occupied our country and things began to normalize, efforts were made to establish sports clubs along Soviet lines.

Every major enterprise – kombinat or trest (as the large enterprises were then called) – founded sports clubs with names like Dynamo, Spartak, Zhestyanik, Pishtshevik, and others.

These were the standard names of the clubs, used by all sports organizations

[Page 67]

in the Soviet Union. Other names were not permitted.

Our well-known athletes were distributed among all these listed sports clubs, and each person was required to play for the club affiliated with their workplace. Thanks to our excellent athletes, who consistently took first place in all competitions, Białystok ranked first among all Soviet-occupied regions.

This continued until the year 1941, when war broke out with the Germans.

From that day on, our finest and most noble athletes – those who had brought great honor to Jewish sports in Białystok – were killed.

The German murderers seized our athletes even earlier, before the ghetto was established, and almost all of them were either Donershtike [Thursday people] or Shabesdike [Sabbath people][4].

Among them was the well-known figure in Jewish sports, Lyovke Grinberg (a childhood friend of mine), who had represented the Jewish sports clubs in the central Polish associations and had always fought tirelessly for the Jewish sporting cause.

His brother-in-law now lives in Australia: Mr. A. Zbar, who devotes much time and energy to supporting our rescued brothers and sisters from the Nazis.

Thus perished the great and beautiful Jewish sports movement in Białystok.

The Martyred Athletes

In his article on Jewish athletes (Bialystoker Shtime, September 1974), Dr. Shimen [Szymon] Datner listed the following names of martyred athletes, who perished during the final liquidation of the Białystok Ghetto in August 1943. The names are given in alphabetical order:

|

|

Translator's notes:

by Mordechai Pogorelski

Translated by Beate Schützmann-Krebs

English Proofreading by Dr. Susan Kingsley Pasquariella

Memories from childhood remain vividly etched in the mind. I remember how my mother, of blessed memory, once told me – when I was just a little boy – what the Jews of Białystok had lived through in the spring of 1882.

It was during a time when a wave of pogroms swept through many towns and cities deep in Russia – like Kiev, Yekaterinoslav, and others – like a raging fire. The mood among the Jews was deeply anxious. Rumors that the Christians were preparing to carry out a pogrom against Jews in Białystok further weighed down the already heavy spirits.

In the taverns and at the market, peasants and Christian laborers spoke among themselves, saying that the Tsar had issued a decree: “It is permitted to rob Jewish homes and property.”

It happened in the spring of 1882, and my mother told me what she had personally witnessed: Masses of peasants from the surrounding villages made their way into the city – some by wagon, others on foot – carrying sacks under their arms and clubs in their hands, intent on looting Jewish shops. But it did not go well for them!

Word quickly spread throughout the city that the Christians were preparing to carry out a pogrom against the Jews. The Jewish butchers from Yatke Street immediately shut their shops, took their knives and cleavers, and headed for the market.

The drongove carters [named after the broad, flat, horse-drawn wagons used in Białystok to carry loads and people] and the izvoshtshikes [coachmen], who were stationed at the marketplace, also armed themselves with iron bars and sticks to confront the pogromists.

After half a day, drunken peasants began harassing Jews, and groups of hooligans started overturning goods from the market stalls. That was the signal for the butchers and carters.

It didn't take an hour before the market was cleared of peasants.

The butchers set their knives and cleavers in motion, the carters their staves, and the izvoshtshikes unhitched their horses and, riding atop them, drove the peasants out of the market.

The result was that the peasants fled back to their villages – not only with empty sacks, but also cut up by knives and battered by staves and sticks. Thanks to the butchers, carters, and izvoshtshikes, a pogrom was averted in 1882.

On Shabes Nakhamu, 1905, a military pogrom against Jews took place in Białystok.

That Sabbath afternoon, a detachment of soldiers appeared in the marketplace and on Sorazher [Suraska] Street, and began shooting in all directions. The Jewish crowd, out for a stroll, began running into the nearest courtyards.

The soldiers split into groups across the surrounding lanes and fired at random passersby and into Jewish homes.

This continued until late into the night.

The result: on Sunday morning, several dozen wounded lay in the Jewish hospital, and in the hospital courtyard, two rows of dead – victims of soldiers' bullets.

Later, the Jews of Białystok endured yet another great pogrom – the tragically infamous pogrom of 1906, which lasted three terrible days, from May 31st to June 3rd of that year. Once again, much Jewish blood was spilled. Once again, many Jewish lives were lost…

Translator's notes:

by Mani Leyb [Mani Leib]

Translated by Beate Schützmann-Krebs

English Proofreading by Dr. Susan Kingsley Pasquariella

|

–Gedalia, Gedalke, where are you from, That you ring and ring the freedom bell? –I ring with the bell, that freedom may come, And I'm from Bialystok, I tell.

–Gedalia, Gedalke, you heroic youth,

–Gedalia, Gedalke, hero of all,

–Gedalia, Gedalke, and where are you now?

–Gedalia, Gedalke, now rest in your grave, |

by Lawyer Zvi Klementinowski

Translated by Beate Schützmann-Krebs

English Proofreading by Dr. Susan Kingsley Pasquariella

Our esteemed landsman, Zvi (Grisha) Klementinowski, who resides in the State of Israel, where he is a prominent lawyer, is widely known as a Zionist and general Jewish leader among Jews everywhere. He is especially famous among the Jews of Białystok.

One of the tireless leaders of the “Organization of Białystok Emigrés” in the State of Israel, he served as chairman of the last Jewish community in Białystok until the outbreak of the Second World War.

He was also elected as a councilman in the last Białystoker city council, shortly before the war.

When the Soviets occupied Białystok at the outbreak of the war, our friend Klementinowski fled to Lithuania. Later, after various strayings and wanderings, he succeeded in making his way to the Land of Israel in the year 1941.

When Poland assumed control over Białystok after the First World War, the government introduced a law that granted the kehile [Jewish community] religious autonomy. As a result, the kehile became the sole representative body of the Jewish population in Białystok and the surrounding region.