|

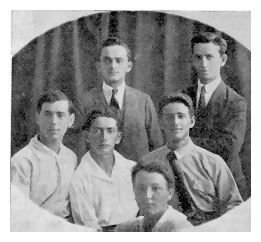

Standing from the right: Oppenheim, Zelinger, Feldberg, Majtlis, Wajnsztok

|

D.L.

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Będzin lay not far from the two borders: the Russian-German and the Russian-Austrian. Thanks to this, the city always was a place where the largest number of those had been persecuted politically by the Tsarist government found a temporary place of refuge and a point through which they would smuggle themselves across the border, some to Vienna, some to Switzerland. There were professional smugglers who earned their livelihood from [the smuggling]; there also was a group of Poalei-Zion[1] comrades, who also “specialized” in smuggling socialist activists across the border.

Leib Trotsky[2], who escaped from Russia, spent some time in jail in Będzin until he crossed the border. In 1905 Yosef Szprincak was in Będzin, where he also spent time in the municipal jail, on his way to Eretz-Yisroel. Ber Borochov and his wife, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Meir Jarblum, the wife of Yitzhak Tabenkin, [Yosef] Chazanowicz, [Yakov] Zerubavel, [Dovid] Bolch-Blumenfeld and a whole series of activists from various socialist groupings crossed the border in the years 1905-1907.

Shlomo Zemach, in his book Bereshit[3], describes how he crossed the border on his way to Eretz-Yisroel in 1904. After the First World War, right after the Balfour Declaration, when the great Zionist revival movement began, Będzin also was the base for dozens of groups of halutzim [pioneers] from Russia and Poland, who were taken care of by us in the city with food, clothing and documents and were sent on their way across the border to Vienna and Trieste.

It is no wonder that Będzin pioneers took part in the all of aliyahs[4]. A group of 10 young Bedziner went in the Second Aliyah in 1905-1907. This was Eliezer Hampel, Arya Szwicer, Moshe Sztajnfeld-Szaham, Yosef Kaluczinski-Ariali, the brothers, Dov and Shlomo Sznajderman, the sisters, Sora and Malka Hampel, and the sisters, Sora and Chana Sznajderman.

It is particularly worthwhile to remember the two groups of Będzin young men that left for Eretz-Yisroel in 1918 – and historically the date marks the start of the Third Aliyah with six Bedziners who arrived in Jaffa on the 12th of December 1918. The first group consisted of Yisroel Oppenheim, Sender Lubling, Yakov Lasker, Yitzhak Handlsman, Kuba Czmigrad, and Dovid Majtlis. The brothers, Moshe and Yakov Rotenberg, the painter Avraham Goldberg, Mordekhai Winer, Hershl Tenenbaum, Yosef Zabuski, Shmuel

|

|

Standing from the right: Oppenheim, Zelinger, Feldberg, Majtlis, Wajnsztok |

The first group left on a lengthy road – Lemberg, Odessa, Turkey, Beirut, Jaffa; on the other hand, the second group went through Vienna-Trieste. It turned out that the longer road was the shorter one and the six halutzim succeeded despite difficult pitfalls, the great chaos that existed then in Poland [and arrived] in the land [Eretz-Yisroel] first. There was heroism among the six young men, who left without documents between two fires, the Polish and the Ukrainian military, and went to great lengths by all means to go further and further on the designated road, not stopping because of the great danger of being arrested or of falling from Polish or Ukrainian bullets. They succeeded after 43 days in arriving in Eretz-Yisroel. All were children of well-to-do parents, had left firmly established homes against the wishes of their parents and were driven by the pioneer spirit of wanting to build the country.

We provide here the impressions of those taking part in the 3rd Aliyah: Yisroel Oppenheim, Shmuel Liwer, in Yiddish, and Yakov Lasker in Hebrew.

Translator's footnotes:

Yisroel Openhajm

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

On a rainy day, the 31st of October 1918, seven halutzim[1] in Będzin left on the road to Eretz-Yisroel, walking 25 kilometers to the Austrian border. There with the help of smugglers to whom we each paid up to 70 krone, we crossed the border on a military train. Thus we arrived in Trzebinia where we had to wait an entire night to be able to travel further to Lemberg.

We had to leave the train, which did not go further, in Przemysl because the Ukrainians had occupied a part of Lemberg County. In Przemysl we saw the Polish legionnaires were confiscating the weapons and even the clothing from the retreating Austrian military. Since there was no possibility of going further and not knowing what to do in a strange city, we turned to the Rabbi, Reb Gdalye Szmelkes, a fervent Zionist. The rabbi, hearing about our destination, welcomed us warmly and immediately sent for the esteemed Zionist middle class in the city, who invited us to their homes for Shabbos [Sabbath]. In the morning, Shabbos, we decided to go further in order to reach our destination despite the fact that there was gunfire all night in the city.

At the train station we found a military train that was supposed to leave for Lemberg and, as it was full of people, we hopped onto the roof without much thought, traveling this way for a while. Gunfire broke out between the Ukrainian and Polish military. Many traveling on the roof fell as a result of Ukrainian bullets. People jumped from the moving train. We also prepared to jump, but as the train had increased its speed, we remained in place. Thus we traveled slowly to the Zimnavoda station, before Lemberg. Despite what we had been told, that street fighting was happening in Lemberg, we decided to go further on foot. Thus we slowly arrived in the city, where there raged terrible chaos. We moved to the wall in the darkness under unending gunfire. We often were stopped by patrols: once it was Poles whom we told we are Poles; once it was Ukrainians whom we told we are Jews. Finally, we were stopped at the Ukrainian military post and we were brought to their commander, where we were searched to see if we had any weapons, and, in addition, taking our second pair of shoes. When they found our Zionist identification cards, we told them that our goal was [to reach] Eretz-Yisroel. Then they apologized, took us to the Jewish part of the city and gave us into the hands of the Jewish self defense [organization].

We were welcomed [warmly] there and received food immediately and we also were provided with places to sleep.

In the morning, the 11th of March, we went to Yad Khorutsim[2] where the Jewish militia was located. A Jewish officer accompanied us to the editor of the Lemberger Togenblat[3] to whom we had a letter of recommendation from Dr. Bikels (now in Israel). Hearing our request, the editor gave us a letter to the Ukrainian commandant, who told us to wait a few days because the train to Odessa had stopped. After three days in Lemberg we decided to go further. We turned to the Zionist organization and asked for a recommendation. They asked us to wait until the situation became clear. We had to turn back several times because of the unceasing gunfire in the city. As we could not really move freely in the city with our documents, two of our comrades joined the Jewish militia where they received weapons and then we were again able to lobby the Ukrainian military regime so that we could leave Lemberg.

Birncwajg's mother arrived in time to keep him from going further and tried to influence us to relinquish our “crazy” plan to now travel to none other than Eretz-Yisroel.

We learned from Mrs. Birncwajg (now in Israel) that the letter we had left with our comrades for our parents before our departure and which we asked them not to deliver for five days until we were far from home, immediately had been given to our parents. Thus, Mrs. Birncwajg succeeded in reaching us to “save” her son, who later finally emigrated to Eretz-Yisroel, and, a short time later, his entire family.

Despite our difficult situation we did not let ourselves be influenced and continued on our way.

On Monday the 11th of November, we again turned to the Ukrainian regime with a letter of recommendation from the Jewish militia and asked for travel-passports to Odessa. We decided that we would travel even if we did not receive the passports. But this time we were successful: we received the blessed permission, but there was no train to Lemberg. What could we do? On the 13th of January we left for Lemberg on foot. We walked 60 kilometers[4] to Glinowa. There we hired a peasant for a payment of 100 krone, who took us to Krasna, from where we succeeded in going to Pidvolochys'k by train; there we again had to leave the train because it did not go any further.

Meanwhile, we saw a military train arriving. We did not think for long and managed to board it.

Thus we slowly reached Volochys'k. We thought we would immediately be able

[Page 122]

to travel to Odessa. There we were told that the train to Odessa would depart from Zhmerynka and we left for Zhmerynka in a fully packed train wagon. The trip that normally would last an hour took an entire day and therefore we were very hungry.

New trouble began in Zhmerynka: it was impossible to receive train tickets. We only received one train ticket for first class. Not having any way out, we decided to travel as “contraband.” We paid the train conductor 50 rubles per person and he made sure that the train would stop in Odessa. There was such jostling upon entering the train that we lost each other. Arriving in Odessa we all again met up with each other. And it turned out that Handelsman had remained in Zhmerynka.

On the same day, the 17th of November, we turned to Menakhem Mendl Usiszkin, who told us that at that time he saw no possibility of traveling to Eretz-Yisroel. In the morning we went to the Palestine office, but there, too, they gave us no hope. We turned to Bialik who gave us two letters: to Usiszkin and to Tzeirei-Zion[5], but these letters of recommendation did not bring us closer to the train.

Meanwhile we had no money. In Odessa we met a group of nine immigrants [to Eretz-Yisroel] who were supposed to travel on the next ship. They brought us to the Ukrainian chief, who signed our passports with permission to travel further. Then we found a freight ship in the port and after much effort and negotiations with the captain, he expressed his readiness to take us along to Turkey.

We said goodbye to Bialik, who greatly helped us in Odessa. We boarded the ship on the 21st of November, which after a few days of traveling brought us to Constantinople.

Yakov Lasker, our “foreign minister,” reported to the Turkish regime with our passports. We declared that our parents were in Eretz-Yisroel and that we had been born in Jaffa. Thus, we received entry to Eretz-Yisroel.

We were in Turkey for 19 days until we succeeded after difficult efforts and trouble to find a spot on a freight ship that brought us to Beirut and then on the 12th of December 1918, we anchored in Jaffa.

Translator's footnotes:

Shmuel Liwer

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

At the same time that the first seven halutzim[1] left Będzin via Lemberg-Odessa: Yisroel Openheim, Yakov Lasker (both in Israel), Kuba Zimigrad, Sender Lubling, Yitzhak Handelsman, Dovid Majtlis (all perished) and Ayshek Birncwajg (Bari) (died in Israel in 1957) at the beginning of November 1918, we eight young men started off via another road to Eretz-Yisroel. The eight were Avraham Goldberg (Tel Aviv), Mordekhai Liwer (Jerusalem), Yehuda Prager (Kiryat Motzkin), Shmuel Liwer (Haifa), the brothers Moshe and Yakov Rotenberg (died in Paris), Shmuel Trapauer and Shlomo Zabatcki. We traveled to Vienna and from there to Trieste. [We were] the first group that arrived in Trieste with the hope of finding a ship to Jaffa.

During the three months we waited in Trieste, a group of 60 halutzim from Będzin, Sosnowiec, Monczew, Lodz, Radom and Piotrkow assembled here.

Our efforts to board a ship did not succeed because of the war between England and Turkey.

[Page 123]

|

|

Standing from right to left: the two Sznajderman brothers

|

Meanwhile, while in Rome we did not want to do anything; we left for Naples. There, too, we found a group of halutzim whom we joined. Meanwhile, in Rome we were recognized by the Italian government as stateless and as such we received support, two lire a day. We lived then in difficult conditions, with dry bread and soup. We had all spent our last pennies that we had brought from home. It should be mentioned here that there was a Christian from Poland in Naples whose name was Palak, and he helped us greatly and found work for several of us.

We were called to the Naples city hall a week before Purim and the mayor told us that we would be leaving for Alexandria in two days.

Two days before Purim, 1919, we boarded the ship, the first ship after the war that took on private passengers.

We were 63 halutzim among an assortment of Italians, English, Arabs, Sudanese and so on. The ship arrived; we danced and sang halutz songs and as soon as the ship left the port, we unfurled a blue and white flag. Our accompaniers and friends, whom we had acquired during that time, seeing the flag, began to shout, “Viva Palestine! Viva Palestine!” However the ship's officer came over to us and said that we must immediately wrap up the flag because no flag but the Italian flag was permitted. We hid the flag with the hope of again unfurling it at the shore of Jaffa.

There was an elevated mood on the ship. The halutzim did not stop dancing and singing. Our comrades gave a concert on Purim. The daughter of the captain accompanied our comrade Szpilman from Kielce, who played a cello; later, the captain raised his cup to the health of the Jewish people and Eretz-Yisroel. The next morning a delegation from first class came to us and brought a sum of money that they had collected for us… Naturally, we returned the money.

After eight days we arrived in Alexandria. Waiting for us was a delegation of local Jews who immediately settled us at an Alexandria hotel. There was then in Alexandria a large group of European Jews who received their first greeting from home from us. A short time later, another 42 halutzim arrived from all corners of Poland, so we were 105 men in total. From then on we were called the group of “105,” which, after the first six Będzin halutzim, was the first large organized group that had come to Eretz-Yisroel after the First World War. The Third Aliyah actually began with them.

Because there was unrest in Egypt, the English permitted only a small group to travel. The first group of the “105” was supposed to number 18 men. Everyone wanted to be among the first. And it was decided that those who had left their homes first would also be the first to travel to Eretz-Yisroel.

On the eve of Passover 1919, we, eight from Będzin, were among the 18 who settled on the train to go to Cairo

|

|

First row: Yakov Rotenberg, Mordekhai Winer, Moshe Rotenberg

|

As a comrade of Ahdut haAvoda[3], the party sent me to Kfar Giladi [a kibbutz]. Comrade [Pinkhas] Shneurson from Kfar Giladi came for us with a wagon hitched to mules; we were four men and one woman and we traveled for three days. There was only one shed at Kfar Giladi, divided into two parts – the cattle were in one part and the second part served as an eating room and an office and at night as a bedroom. After I had been in Kfar Giladi for a few months, we succeeded in receiving a few pounds and bought straw mats from the Arabs in Hulata from which we erected a few huts. It then appeared to us that we were living like lords…

When the Arab attacks on Tel Hai began, we, a group of comrades, were sent to Tel Hai to help the comrades there. Thus, Moshe Rotenberg and I with 30 comrades delivered the bloody attack on Tel Hai.

When [Joseph] Trumpeldor was wounded, we made a litter out of blankets and we began to take him to Kfra Giladi, but he died 200 meters before the kibbutz. The same night we returned to Tel Hai, from which we brought out the fallen comrades and, later, the living. We finally withdrew to a hill and two of our comrades set fire to Tel Hai. I will never forget the night when I lay at Shneurson's side; and when Tel Hai began to burn, Shneurson shouted out: “Tel Hai is gone!” – this was the cry of the entire settlement.

Translator's footnotes:

Dovid Abi-Menakhem

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

In general, Będzin was a pioneer in the Jewish neighborhoods in a series of communal areas, so it was natural that if Będzin took part in the Second Aliyah[1] with one of the first groups of halutzim[2] groups, it was six Będzin young men who began the Third Aliyah. To them we need to add the seven from the year 1932. [They were] the only ones in Poland that undertook to travel to Israel in a small car despite the great difficulties connected with such a trip through borders and countries.

The trip by the seven halutzim was one of the most beautiful propaganda trips for Zionism at that time. They were warmly welcomed everywhere they traveled and not only by the Jewish population, but also by athletes from all nations. Perhaps thanks to this, they actually succeeded in achieving their purpose. The trip was not financed by any institution, but by the seven halutzim themselves.

The idea arose with one of the group, who already had been in Israel and because of a conflict with the Arab and English police had to leave the country. This was Dovid Honigman, of blessed memory, who turned to the writer of these lines as managing committee member of the sports-union, Hakoach[3], which made contact with the Makkabi World Union in Poland and asked for their support for the realization of the idea; the Makkabi World Union in Warsaw agreed with the plan in principle with the comment that the trip could be made only with the responsibility being with those taking part.

After a certain time the appropriate candidates were chosen. These were: Dovid Honigman (died in Israel), his brother, Shimeon Honigman, Kalman Honigman, Arya Majtlis, Moshe Galek and two from Sosnowiec, Yehezkiel Sztajnic and Arnold Waksberg (all in Israel). The seven, all dressed uniformly, left for Israel in a “Mercedes” car with a blue and white flag on the 4th of December 1932 from the Będzin Hakoach Square, accompanied by several thousand Jews. They spent the first night in Krakow where they were welcomed warmly by the Zionist organization and the local Jewish sports union; from there, on the second day they traveled to Bielsko-Biala[4], in Mährisch-Ostrau[5] to the Czech border. Here they were met by Max Weber [and] representatives of the Makkabi World Union in Czechoslovakia, who accompanied them to Brin[6], where they slept in a dormitory. They were welcomed enthusiastically everywhere, in Proshnits[7], Wischau[8], Olomouc, where they had their first accident with the car. Traveling up a mountain, suddenly the car began going backwards and was stopped by a tree. If not, they would have rolled down into an abyss of a few hundred meters. Emerging with light wounds. they looked for the village magistrate, who helped them, took them in for the night and gave them food. In the morning, unable to find a garage, they drove the car to a Polish smithy and fixed it themselves – and

[Page 125]

they traveled on to Vienna where they had to remain for 10 days because of visa difficulties. They slept in a dormitory, spending the time with arguments and song. Thanks to the intervention of Dr. Shtriker and Dr. Hurbitz, they succeeded in receiving a visa to Yugoslavia.

They also were happily welcomed by the entire Jewish population in the Yugoslav shtetlekh[9]. They spent the first night of Chanukah in a small town where the entire population, Christians and Jews, happily welcomed them. A banquet with speeches of welcome was arranged for them in another town. In the meantime, they succeeded in founding a Makkabi club in a short time.

They arrived in Zagreb on New Year's night during a heavy rain. Not knowing where to go, a stranger suddenly approached them and asked for whom they were looking. He led them into a hotel, asked that they be given food and in the morning brought them to the Jewish sports club where they learned that this was a Christian who declared that he considered it a necessity that he help all athletes. Later, they were invited by the Jewish millionaire, Shpits, to lunch in his palace. As they were saying goodbye, he asked them to take two revolvers and asked them to give them to the Haganah[10] in Eretz-Yisroel. They could not continue in Danji Miholjac on the road to Belgrade because of the heavy rain. The peasant population helped them go through the difficult and slippery road with love, bringing sand and ash and spreading it on the road. Thus the car traveled on. However, not far from there they had a second accident. With luck it was not far from the castle of the Jewish Baron Shlezinger, who welcomed them with great respect, let them repair their car and thanks to him, who gave them a letter to the English consul in Belgrade, they received an English visa to Israel.

They were welcomed by the Chief Rabbi when they arrived in Belgrade and also by the Polish consul; not able to receive a Turkish visa (because the Turkish consul declared that because of the unrest in Eretz-Yisroel he was afraid for their lives…), they traveled to Greece and from there to Alexandria on a ship, where they were the guests of the Jewish sports club, which housed them in the nicest hotel in the city.

The time the group spent in Alexandria was a time of revival for the Zionist young people – they sang and danced every day until late at night. From there they traveled to Cairo and, again, were welcomed by the entire Jewish population and as the kehile[11] had just opened a new house for Shabbos [Sabbath] visitors, they were the first guests there.

They spent eight days in Cairo and were taken around the country by the Makkabi Union. There were banquets with speeches every night, Zionist songs, gifts. They traveled accompanied by all of the young Jews to Ismailia, across Suez, to El-Arish and from there, on a sandy road, to Eretz-Yisroel. They arrived in Beersheba with a few hardships. They were arrested there by the English police, who found sacks of revolver bullets in their car. They were fined by the court to pay 7,350 pounds. Not having any money, they telephoned Jerusalem; the [Jewish] Agency immediately sent the money and paid the penalty.

They were joyfully welcomed by the Makkabi Club in Jerusalem on the 14th of February 1933. The next morning they traveled to Tel Aviv where they were met on the way there by the Makkabi chairman, Moshe Shaham, our townsman, who led them into Tel Aviv with a great parade.

|

|

Motek Hampel

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

|

Childhood years, beautiful, sweet years,

You remain in my memory forever.

When I think of that time,

I feel regret and sorrow…

(From a folksong)

Half a century ago, my grandfather, Reb Aycek Fridler, may he rest in peace, was an esteemed, honored Jew to whom one listened. Despite the fact that he was a Gerer Hasid, he had a good name in all opposing Hasid circles because of his good attributes.

My grandfather breathed out his soul on a wintery Shabbos [Sabbath] afternoon. The next morning, when the funeral took place, is deeply etched in my memory; the image of how my grandfather lay on the ground, covered with a black cloth, the flickering flames of the dripping candles at his head and the lamenting shouts of his widow and 10 surviving orphans,[1] upset my soul.

My grandfather had a mill that was located over the wooden bridge on the road to Grichow at the Czarna Przemsza River, which flowed into the Vistula. It was not his possession, but belonged to a landowner; he was named Szperling, not the worst of the non-Jews, who leased it to my grandfather and his partner, Reb Henokh Epsztajn, whose gifted and beautiful daughter had great success with the Będzin young men.

As a child I often visited the mill, which was my best pastime because there I had the opportunity to be mischievous without any disruption or be given orders in an area with such spaciousness and size. What was not there? Horses with foals, which I gladly helped harness to the large goods wagon, stables with piles of hay, storehouses piled high with sacks of flour, elevators and ladders on which I climbed and fell from more than once and severely hurt myself, but meanwhile my heart mostly grew with pleasure and joy.

I was a boy of five or six when I studied in Reb Nakhum Katshka's kheder [religious primary school] (his nickname [duck] was because of his rasping voice); a tall Jew, thin, with a pointy small white beard, who never let go of the whip in his hand. Alas, the students tormented him with all sorts of ingenious ideas, but when we fell into his hands, he properly took his revenge on us.

One day Reb Nakhum poured his entire anger on my small head, being full of reproaches of me because I did not grasp the alef-beis mit pintlekh [the Hebrew alphabet with the vowel sounds] and I was completely innocent. Without delay, during that very “term,” my father brought me to Reb Yehosha Razenker's kheder, across from our building on Ĺwiętojańska Street.

Reb Yehosha was not just anybody, one of the advanced teachers and a Zionist-Mizrakhi [religious Zionist]. All his life he was restrained and his black beard was well looked after and combed. Walking in the street with his cane he held his head high to appear dignified in the eyes of the respectable people. The sons of the rich men and middleclass Jews studied with him. I remember only a few kheder friends: Marek Szajn, Elimelekh Diament, Dovid Feldbaum (these three are in Israel), Zalmen Sztrachlic (in America), Mendl Malerman (London), Kopl Hercberg (Paris), the Rebiszewski brothers, Yitzhak Feldbaum, the Lewkowicz brothers, Moshe'l Prawer, Leml Ratner, Yoal Szicer, Dovid'tshe Khaper, may their memories be blessed, and others.

My melamed [teacher], Reb Yehoshua, also was a good bale-tefilah [the cantor or man who prays for the congregation at the lectern] at the shtibl [small one-room synagogue] (in Shlomo Szajn's house) where Kurland had an iron business at the old market, which later was moved to the residence of Brukhia Majtlis, a distinguished resident of the city, in Chaiml Liwer's house at Salachowska Street, known as the “Katowicer Shtibl.” When Reb Chaim Szajn built his house, in 1924, on Malachowska Street, he provided a special room for this minyon [prayer group] that was then named for him and for his brother, Itshl Szajn, who were beloved for their communal work and philanthropy in the city, along with their dear wives, Hana'la and the much revered Tsesha, one of the rare female activists in the city. The well-known bale-tefilah who also participated in the minyon as cantor

[Page 127]

Yehezkiel Fridman, Avraham'le Rechnic and Gershon Rechnic, who was seen as a very active city communal worker.

When Reb Yehoshua stood before the pulpit on the Days of Awe and sang the prayers so heartfeltly, supported by his son, Moshe'l (in Israel), all of the worshippers were pleased and everyone was moved [by his praying].

In my kheder, which was a kheder metukan [modern religious primary school], we also studied secular subjects. Yehoshua Rapaport, the long-time, well- known pedagogue, taught us Russian and Polish. The rebbe's son taught us arithmetic and calligraphy. The rebbe himself [taught us] Jewish subjects and Yiddish, the teacher Janowski – Hebrew. The knowledge we acquired as children at that time I remember to this day and will never forget it.

Yes, I still remember that a large picture of Tsar Nikolai the Second hung on the eastern wall of the kheder. When the inspector from the high school officials came to visit, the rebbe was very afraid, quickly putting on his Shabbos [Sabbath] kapote [long coat worn by pious men], submissively removed his Jewish hat, and we, the children, stood singing and by heart the Russian hymn, Bozhe, Tsarya Khrani [God Save the Tsar], which we did not understand.

We studied impatiently in kheder the entire day until the evening hours, but with a midday meal pause. Even on Shabbos we went to kheder to learn Pirkei Avot [Ethics of the Fathers] and Borkhi Nafshi [Bless My Soul] Psalm 104. We were freed when it was almost dark, when the city lamplighters, who turned on the gaslights, appeared in the streets and children shuffled around, accompanying his every movement, shouting “there you go” and “hurrah.”

Often, we sneaked out of the kheder, played “tag,” “blind man's bluff,” “hide and seek” or ran after the city crazy people, who were calm by nature: “Mendele Mishebeyrekh,” [Mishebeyrekh – prayer for person called to the Torah], Anshel Dreykop [schemer, wheeler-dealer], who went back and forth, barely placing one foot and then the “popular” crazy Sura who once threw a stone at my head…

The best day in kheder was Friday when we only studied until noon. We repeated the weekly Torah portion and discussed the weekly Torah portion and then the rebbe would read stories from the legends that were very pleasing and we would not tire of hearing more and more because God's miracles during the Exodus from Egypt, the wonderful history of the selling of Joseph or the stories of the calamities and misfortunes that would occur at the end of days in the time of Moshiakh [redeemer] on the nations of Gog and Magog because of the persecutions and oppressions they had caused the Chosen People, had such an intense effect on us…

I was a God-fearing, pious boy and observed all of the commandments and laws. I did not eat and did not drink if I had not previously said haMotzi [blessing over bread] and Shehakol [blessing for other foods]. Before going to sleep, I did not forget to read the Krias Shema [prayer said before going to sleep]. In the morning, I poured the negl-vaser [washed hands upon awakening] and recited Modeh Ani [prayer recited in bed upon awakening] – all of this thanks to my kheder education, where I heard terrifying stories about non-observing Jews who, God help us, burned and roasted in gehenim [hell].

On summer evenings, when the sun bent to the west and the skies were lit with red clouds, I knew that the wicked were being burned with whole casks of tar…

I would pray Minkhah and Maariv [afternoon and evening prayers] at the house of prayer, where Reb Feywel Rapaport (the brine maker) at the herring shop at the old market would pull my ear and pinch me on the cheek, so that I would answer the prayer leader with an “amen” after each “Blessed is He and blessed is His name.” Satisfied with my behavior, he assured me [of a place] in the World to Come [i.e. heaven]; he took out his tobacco box and honored me with a pinch of snuff between my fingers and drawing in the strong aroma I sneezed so strongly that it seemed to echo throughout the entire house of prayer.

During the summer months we went home from kheder earlier, not staying late, in order to be able to make use of the happy, sunny and, for us, carefree days. In my free hours I went to my grandfather's mill, swam in the river, climbed and rolled on the sacks of flour.

The water in Przemsza [River] was not rough, although it also demanded and lay in wait for its victims. It did happen that, God forbid, a misfortune occurred and someone drowned, which brought dread to the entire area and parents warned their children not to dare to swim anymore. One had to be as strong as iron to endure such bitter temptation, because the yetzer hara [evil inclination] is present among the sinful in God's world…

The water of the Będzin River also served for washing laundry and even for drinking. We did not know about distilled water then because it was in the later years that running water was installed in the majority of houses. Chaim Dovid Grosman was one the first artisans in this area [plumbing], then Chaim Dovid Rudzin and Moshe'l Krzanowski.

The city had several wells, from which water carriers pulled and pumped and drew the pails of water on their hips, carrying it to houses for a few groshn. I remember two of them, Mendl vaser-treger [water carrier] and Berl Beser the liferant [contractor] in our house. An old, broken Jew, who heavily toiled, girded his loins to earn money for his two orphans [in Yiddish, a child who has had one parent die is an orphan], until he fell under the burden of the yoke. He had saved [money] from the little that he earned so that his son could study in Yavne gymnazie [religious Zionist secondary school]. The latter later worked as a bookkeeper at Kurland's business.

As we are talking about the development of our city, we need to remember that Będzin progressed greatly during the last years of the war and had far-reaching expectations. Because of the law of “Urbanism” (beautifying the Polish cities) Będzin was transformed into a great beauty… Old buildings and fences were demolished and new many-storied houses were built in their place, built exclusively by Jews according to the latest styles of architecture.

[Page 128]

A modern train station and postal institution were built; the spread of an electrical network was proposed. The old and new markets (where the municipal fair gathered) grew into squares. The horse cabs and horses, which had always served as an internal means of mass communication were abolished and their place was inherited by the tramway, a rarity in the province, with the exception of Zagłębie.

Magnificent Jewish social and cultural institutions also arrived, for example, the maternity hospital at the linas-khoylim [society to help the sick], the co-educational gymnazie [secondary school] named for Shimeon Firstenberg and his wife (previously Yavne [religious Zionist school organization]), the orphans' house, Sierociniec [orphanage] (built by the well-known donor Yakov Gutman).

Let us return to the theme. The majority bathed under the mountain where the Przemsza [River] snakes among fragrant fields, green with flowers and meadows overgrown with daisies, far from a human settlement. Here one could always encounter the popular Marian Stanek with his large dog, a liberal Christian who had friendships with Jews. He was one of those friends of Jews who were so rare.

We swam in the so-called bedlekh [small baths] at the swimming baths for a payment, but this was worthwhile because we were safer from an attack by the gentile boys who had terrorized Jews more than once while they swam under the mountain where they also “went boating” and in the winter skated on the frozen water.

I remember an episode that occurred with a boy at the Talmud Torah kheder [primary school for poor boys], who skated on the river and fell into the water where it had suddenly melted. Ayszyk Birncwajg (Iser Bari, died in Israel), one of the most capable young people at that time and one of the first halutzim [pioneers] of the third aliyah [immigration to Eretz-Yisroel], seeing this, jumped into the cold water and pulled him out, but the boy already was dead.

As an industrial city, Będzin did not possess any beautiful natural scenery, appropriate rest places, parks and gardens. The fenced in Góra Zamkowa [Castle Hill], where the ruins of an old Polish castle remain to the present, served as an amusement spot for couples in love and for romantic meetings. When such a couple was discovered amusing themselves privately, it was proclaimed immediately in the synagogue and in the house of prayer that such “reckless” [young couples] would be banished, God save us, and they will not come to the gathering of the community of Israel…

Incidentally, the oldest Jewish cemetery from 150 years ago was located near the Góra Zamkowa; the headstones were half sunken, but with difficulty their inscriptions could still be read. It is superfluous to say that no trace remains of the cemeteries (and of others) because they were destroyed by the German hangmen.

The “railroad tracks” where the train goes through and the open górkę [hill] were besieged by the poorer residents who came to grab a little fresh air during the hot summer months. In contrast, the wealthier Jews traveled to their dachas [summer houses] in Żarek, Olkusz and the Slowkower forests and, during the later years, the Beskid Mountains, to Rajcza and Szczyrk.

Będzin was lacking in forests. It was forbidden, particularly for Jews, to enter Brzozowica forest, or the “Zielano,” several kilometers outside the city. Whoever wanted to go on a majówke [picnic] to the forest first had to secure a recommendation from the leśna [forest guard) – and permission rarely was obtained…

Our river did not have a beach. Men swam, stark naked, on one side of the shore and women on the other shore, in petticoats and nightshirts. It happened more than once that some sort of joker who wanted to play a practical joke for spite, would rush through on the babskie [old wives] side… When he was noticed, such a commotion arose from the surprised girls as if, God forbid, they had been attacked…

At that time, there was great shame; they were ashamed not only of a little décolletage, but there even was shame in [wearing] a dress with short sleeves. If such a [thing] befell a woman she was considered, God preserve us, a “debauched woman.”

I bathed with pleasure in the river near my grandfather's mill because there I was safe in case of an emergency. Once it happened – I do not remember exactly how this occurred – that one of my friends, not giving it much thought, pushed me so that I fell in the water. I did not know how to swim and I began to drown. The millworkers ran when they heard the shouts from those around me and a gentile jumped into the water, grabbed me by my hair and pulled me out. almost dead; I was laid on the ground, they turned me over with my back up and they began to bang me on my head and lungs so the water would come out of me… Reviving a bit and feeling my breath again, I was carried, shaking and twisted from the cold, to a neighbor's house.

The feldsher [barber-surgeon] Braun, who was known by the name Motl Feldsher, and who knew well the trade of leeches, placing glass cups and prescribing cod liver oil for every stomach pain, immediately was summoned. Those were the best remedies against all kinds of diseases then. He had a good reputation as a good doctor, no less than the Będzin Jewish doctors before the First World War, Wasercwajg and Wajnciher.

They summoned the feldsher, who always was in a good humor; he examined me, checked my pulse, placed his ear on my heart with his prickly yellow beard, tapped my ankles, turned my elbows and seeing my grimaces and gestures, stated that I was alive… He smiled as if wanting to calm my crying mother, saying that if I had emerged undamaged and had overcome such an extraordinary misfortune, it was destined from God that I would live to 120.

[Page 129]

Let also be remembered here to their credit the feldshers Hartman and “Abele Feldsher” who also practiced then. During the later years, Herman Szer came to Będzin. He was a good Jew and a follower of the Enlightenment who was accepted by the Jewish masses as a good feldsher, because of his competence and expertise. He also wrote for the Będzin newspaper. There also was a gentile feldsher, Krzimowski, a friend of the Jews, a man with progressive views. He did not take any money from the poor sick and even gave them medicine without cost.

He was beloved by every part of the population because of his tolerance in relation to everyone, even in relation to the “free ones” [non-pious] who began to dress in the “German” way: with three-quarter length coasts, with cuffs on their shirts, with shirt collars and “ties.” The outward garb was not the most important thing to him; since he was influenced by everyone's heart and good deeds, in general he was a great meykl [one who favors a lenient interpretation of law] and not fussy in interpreting religious laws and always tried to refrain from extreme bans so as not to make things difficult for the population, which we also learn from his books and essays.

From a letter written by Reb Graubart, of blessed memory, to a close friend we learn that before the First World War, when machine-made matzos for Passover were almost a rarity in Poland (except in Krakow and Galicia, which belonged to Austria), he gave his agreement and rabbinical authorization for the machine-made matzos. Under pressure from religious radical spheres and Hasidim in Będzin, who believed that matzo production by machines and not kneaded by hand and not baked in ovens under the special supervision of mashgikhim [“supervisor” of kosher food preparation] are not kosher, the rabbi, despite his capacity and authority, was forced, so as not to aggravate his relationships, to relinquish his dispensation and banned the machine matzos, which had a great effect on his health.

He had to endure such aggrieved and unpleasant tensions about the authorization, but he had to endure it all with [communal harmony] to avoid bad blood.

I heard many episodes about Rabbi Graubart, of blessed memory, which were told in the city [and] revealed his wisdom and understanding of the simple Jews. Here is one story:

A poor Jewish woman saved several dozen kopekes and bought a chicken on a weekday at the order of a royfe [a traditional healer] (a pleasure that she could only permit herself in honor of a holiday) for her weak and sick husband to help him maintain his strength with a little soup and a piece of white meat. When she made the chicken kosher, she noticed that the gall bladder had vanished… She cried out because she knew the religious law that a chicken without a gall bladder is treif [unkosher].

She ran trembling to the rabbi to ask him a question. The rabbi, seeing the troubled and terrified Jewish woman, had compassion for her. “Perhaps you thought that the chicken had no gall bladder?” Try to lick the chicken; if it tastes bitter, it is a sign that chicken has a gall bladder. God forbid, if it is not bitter – it really is treif…”

The Jewish woman, who was confident in her claim, became doubtful and desperately murmured: What will I do now, dear Rabbi? Oh, how bitter it is for me!...

Grasping the word, “bitter,” the rabbi immediately ruled: The chicken is kosher!...

As a boy I used to visit her residence as a messenger for my father twice a year – on Purim and on Chanukah – and I brought her Shalakh Manos [gifts of food exchanged on Purim] and Chanukah gifts. Each time she thanked me nicely, smiled kind-heartedly, asked about family matters and was eager to know how I was studying in kheder [religious primary school]. At saying goodbye, she gently patted me and blessed me that my parents should have much joy from me and that I should be a devoted and honest Jew.

Her majestic appearance, her pale face in which the Divine Presence rested, the sparkling bonnet adorned with imitation pearls and diamonds, her motherly behavior with everyone – all of this captured my young soul. Her image stands before me as if I were seeing her yesterday for the first time, although over 40 years have passed since then.

A story was told in Będzin, which I heard from my mother, may her memory be blessed, and this was the plot:

A Jewish woman from our city would walk around among the Jewish housewives gathering their geese and ducks, taking them to the shoykhet [ritual slaughterer]. Then she plucked their feathers and cleaned them. This occupation was not easy, but a person will do what they have to do for income.

Her husband, burdened with half a dozen small children, was unable to bring home a miserable income, so his wife was his helpmate. Both toiled and were not satisfied with only a piece of bread and a warm meal of potatoes and pearl barley because where could they find money for jackets and shoes for the children and for tuition for the teacher, for a vow and for charity and a guest on Shabbos [Sabbath], not by bread alone does a man live.

Thus, they both barely extracted a weak livelihood and they would have lived out their lives this way, when the devil convinced our woman with the force of impurity that

[Page 130]

she should kill the poultry herself, saving the slaughtering payment to the shoykhet.

She could not vanquish the Satin; she let herself be persuaded by the evil inclination and slaughtered the poultry herself and caused cautious, pious women to yield to temptation, God help us.

However, it was not a secret for long. One day someone learned of the deed and the information immediately spread through the city, which became very alarmed and terrified of a punishment from the Creator of the World.

There was a commotion, shouting and [something] not to be imagined, not a trifle: such a sin had been committed that cannot be thought of since Adam, the time of the first man's… And they ran to the rabbi

|

|

and asked for his advice, how to atone for the sin they had done unintentionally… However, the Jewish woman [who had slaughtered the poultry] denied everything and did not feel any guilt because she always was watchful of her God-fearing Jewish soul…

When the Jewish woman came to the rabbi, he was busy with a Talmud lesson with his students during which he never welcomed Jews with “questions” and did not rule on religious laws. The rebbitzen welcomed her and warmly as usual with everyone, asked her to sit and to wait patiently until the rabbi was free from his lesson.

The talkative Jewish woman could not sit quietly, stared at the rebbitzen with wide eyes. She tried to defend herself with all kinds of holy oaths, burned with a kind of sharp tongue and shouted curses at those who created such a libel against here; it never was and never existed.

The rebbitzen patiently listened to her speak and finally said:

“Well, if you yourself slaughtered the geese, ducks and chickens, it truly is a half sin. However, much greater is the sin that you slaughtered the poultry with a dairy knife…”Hearing such argumentation, this Jewish woman jumped up as if burned by a frying pan of cooking oil and exclaimed: “May I and my children live, dear Rebbitzen, I always used a meat knife…”

We kheder-yinglekh [religious primary school boys] could not comprehend the reasons for unease and sadness that held sway over everyone. On the contrary, it was a happy time because we were freed from the burden of studying, a miracle that happened very rarely…

I remember the withdrawal of the Russian military from the city. There was chaos. Government offices, granaries, barracks were attacked, grabbing everything that they found. I ran around with the neighborhood boys through the streets, up to the train station where the ticket office was thrown open and train tickets lay around. I filled my pockets and ran home joyfully, naively believing that I now possessed a treasure because I could travel around the entire world with the kolej [train] free.

My parents then lived in a three-story house in an alley, which numbered six houses on both sides of the sidewalk. The owner of our house was a gentile who always would reproach us, that we Jews were guilty of the death of the Christian Messiah. When the Germans entered the city, we went up to the attic and from there we watched through binoculars (lorgnette) Czeladzka Mountain, which was besieged by the military, marching to Upper Silesia I remember the advance guards who rode on horses with long steel lances decorated with national pennants, asking: “Are there still Cossacks and Russians here?” – After the advance guards came the cavalry, artillery, entire regiments of foot soldiers and innumerable wagons covered with tarps because automobiles were a rarity then and horses were of great importance.

The Jewish population was divided into two camps: one supported the German Kaiser Wilhelm and the other side were for Fonya [(Russia).

During those years, if someone in Będzin needed a good doctor, it was necessary to travel to Prussia, to Breslau, which was famous for the “Jewish Hospital.” I also was healed in Katowice because in our area up to Krakow, which belonged to Kire [Franz Jozef I – Emperor of Austria] (Austria), there were no specialists available for ear, nose and throat illnesses. The son of my uncle, Reb Yankel Fridler, may his memory be blessed, from

[Page 131]

Modrzejów (he was a dear Jew, truly a tzadek [righteous man] with his entire body) led us across the border without a passport because they were acquainted with the guard.

In order to avoid disorder in the city, a militia was created of Christian and Jews. I was strongly impressed by my uncle, Shaul Fridler, of blessed memory (the former owner of the Nowoszczi cinema), who was a policeman and wore a band on his arm, a whistle hung from his neck and a whip was in his hand. In my eyes he looked like a hero…

The commissariat of the militia was located in our street, in the house of Reb Itsik Hersh Majtlis, the first bank owner in Będzin, who later sold it to the famous iron merchant, Hershke Merin – where the Society to Help the Sick was located until it moved to its own building.

Because of a sacristy of apartments for high military officers, a room was requisitioned from every family with a large residence in order to quarter the high-ranking military men. An officer of Jewish background resided with us, whose long, sparkling sword, bigger than I was, I loved to play with. I was note harmed by doing this. On the contrary – it was very beneficial, because he provided provisions, under the pretext that there was a shortage of food products that were distributed through [ration] cards.

To coordinate the proper distribution of the means of life a central municipal provisions committee arose, which consisted exclusively of Christians. The Jewish population had to stand for hours in rows at the Jewish committee at the slaughter house to receive the distributed provisions.

It was impossible to eat the dark rye bread because it was baked with maize, of the worst, flour residue mixed with straw and all sorts of leftovers. Yes, there was a black market, where one could get everything, many good things, but one needed to be as rich as Korach in order to pay the rising prices. Butter, eggs, milk, meat and vegetables were very expensive. The newly rich non-Jews ate as they wished, but the broad-based strata of the people really did not have enough to eat. The results of malnourishment were not slow in coming. Infectious diseases and plagues broke out and raged. The entire house was isolated when a stomach or fleck typhus moved through a family: the dangerously ill patient was taken to a special hospital outside the city where the conditions and nursing were completely insufficient so that this really brought a deadly fear. The apartments in the house were disinfected with carbolic acid. The residents and everything in the house were taken to a disinfection site where they were thoroughly washed in very warm water, their hair was shaved and their clothing was steamed in a special steam boiler.

Trading on the black market was forbidden by the municipal regime, which issued a slogan, Walka z lichwą (fight against usury). Whoever violated this prohibition and was caught at the transgression was placed on trial and was punished.

It also was difficult with clothing and footwear. Most of the children walked around barefoot or wore bast shoes, a sort of sandal made of wood with a strap. The clothing was sewn with bad cloth, even with sacks.

I still remember from wartime that the German soldiers went from house to house and requisitioned brass items such as doorknobs, mortars for coffee, kitchen utensils, chandeliers, candelabras and, in general, every item made of brass, which was melted for ammunition.

It is interesting that despite the depression because of the events of the war, the young found employment in various unions that were founded then and had a strong ascent: HaShomer [Guards], HaKoakh [Strength] and Evria [Hebrew]. Even the political unions, which were legalized, carried on intensive work.

Rozenkwit, Zylberberg, Janowski and Khurgel, the Hebrew teachers, created a dramatic circle in which I was included; I remember only a few [members]: Yehosha Wigadzki, now in Poland, poet in the Polish language, his brother Leibek Wigadzki (his fate unknown; while still young, he left for Russia and has been silent since then), Shlamek Erlich (graduated from the Haifa Technion; returned to Będzin; perished there), Abramek Erlich (also a graduate of the Haifa Technion, city-engineer in Haifa), Yakov Winer, who excelled with his beautiful singing (perished with his entire family).

Our performances were given in Karsa hall and had great success. The repertoire consisted of Chana and her Seven Sons (as Chana – the then well-known leader of the girls' groups at HaShomer, the dear and beloved Ester Lasker), a Purim play, Sholem Aleichem's one act things, Yitzhak Katsenelson's children's plays and others.

Once a story spread that one of we “actors” had gotten “stage fright” – and that which he had to play later he said earlier, before its time, and confounded one thing with another… The prompter, excited, tried to remind him of the role in such a high voice that he was even heard in the gallery [balcony]. The audience did not understand our strange and unpleasant situation, so that we came out unharmed and consequently were rewarded with strong applause…

Thus the years pass. The war comes to an end. The English and the French victories on all fronts are obvious. Hungry and shabby German-Hungarian-Austrian soldiers drag themselves through the streets of the city. The square of the new market, where we would sell kitchen utensils, household items and furniture each week, was besieged by wounded soldiers wrapped in bandages. Jews – children of the merciful – offered them something to eat, in order to maintain their souls and a tepele [cup] of tea ([using] our specific Jewish lefele [spoon],

[Page 132]

shisele [bowl], with a weak lamed with which Sholem Aleichem, the writer, delighted in when he was in Będzin).[2]

The German capitulators gave in and withdrew. The Poles celebrated; their opportunity had now come to free themselves from foreign domination. They attacked the withdrawing German soldiers, disarming them without any interference. At the entrance gate of our house, I saw a Pole tear off a uniform and shoes from a soldier, leaving him in only his underpants.

We, Jews, hoped that with the rise of a liberated, independent Poland, our lives would take their course with the new. However, the opposite happened. Recruits and Hallertichikes (Polish soldiers named after General [Józef] Haller) attacked the Jews, beat them and cut their beards. Suffering Jews appeared in the streets with handkerchiefs bound around their shorn faces. We had barely seen the recruits marching when a panic arose. The shops were boarded up and we hid. The only ones who were not afraid were the bakhmanes (freight porters) who never refused [the offer of] whiskey and, therefore, were not tipsy or drunk. It often came to bloody fighting between the reckless young gentiles who wound up injured and with broken bones from the porters' clenched fists. We still remember the story of Yisroelke Ferszternfeld (Pipek – belly button), who wounded a young gentile in the head and actually was imprisoned in jail because of this for almost a year.

In the 1930s, when the anti-Semitism raged anew in Poland and after the pogroms in Przytyk, Czestochowa and Brisk, the porters, who had already been organized into a professional union at the Poalei-Zion [Marxist Zionists], created a self-defense organization in Będzin in case of trouble.

Będzin remained a fortunate exception to the rule. And with luck, no serious anti-Jewish unrest ever took place against us, as for example in Kielce, the residence of the województwa [provincial area administered by a governor], because we were the majority in the city and the Christian workers, who belonged to the socialist movement were for tolerance and worker solidarity for all the ethnic groups.

Let us remember here for the good, the simple, common Jews, who toiled so hard to receive their daily subsistence, showing that Jewish life and property was not ownerless and to defend our honor; Avrahamle Bachman, with a red nose from 96 proof whisky and his son, the Bambilaks, the Pipkes, the Shniebes and the employed workers in my father's sugar and grocery business, the brothers Volvele and Ribele Zawada (both in Israel) and others.

I cannot end my memories of my youth without writing a few words about the scout organization, HaShomer, and the sports organization, HaKoakh, to which I belonged for a certain time.

I was then 13 years old. No special ceremony was made then when one became a Bar-Mitzvah. On a regular Monday or Thursday, one was called up to the Torah, recited the blessing, drank a L'Chaim [toast to life] and [received] the blessing from his father on the son's Bar-Mitzvah… I received a nickel watch from my father, planted a tree in Eretz-Yisroel through Keren Kayemet [Jewish National Fund] – and that was all. My tefillin [phylacteries] from then, actually an antique, with time were inherited from me by my son…

The HaShomer consisted principally of school boys. It was during the last days [before the Second World War] that the ordinary people and those who wore long coats [the religious young people] joined. I prided myself with appearing in the street in the scouting uniform with a “button” (mayflower) that only qualified scouts could wear pinned to the chest. We, scouts, were obliged to do everything according to the 10 commandments of the “credo” and only good deeds. When, for example, a fire, God forbid, happened in the city or its surroundings, we had to be the first on the spot of the misfortune to help the firemen put out the fire and to rescue [people].

The firemen were located on Zawale Street near the wide Buekh (water) and consisted of Christians and of several Jews: the dentist Zelig Felznsztajn, Hendler, Flesner, Yitzhak Muszinski (in Israel), Motek Winer, who tragically perished in a sewer system pit, trying to save a Jewish boy who drowned there, and Wraclowski (known by the name “Jajka” – now in America.)

When a fire broke out, and this happened very frequently, the bells were rung that were located at the corners of the streets. The firemen immediately came together, they requisitioned horses and they harnessed the firemen's wagons – pumped the water by hand and put out the blazing fire. In the later years, the city furnished them a modern firefighting machine; it was called “Jajka” and it drew the water itself with a diesel motor and had a boiler reservoir of several thousand liters [1,000 liters equal a little more than 264 gallons].

The head of my kvutsa [unit] was Woidislawski (in Israel). The meeting hall was in Zmigrod's large building, then in Brader's house at Manjewer Street. A large photograph of Baden-Powell, the founder of world-wide scouting, hung on the main wall of the meeting hall, painted by Altusz Winer (now in America). Mostly, we came together in winter-time, at the Malabandz meadows, studied Zionism and scouting education, read and spent time peacefully.

To my kvutsa (unit) belonged: Yankel Frajberger, Moshe Herszfinkle (both in Israel), Yosef Szpira (died in Israel), Shlamek Rembiszewski (died in Israel during a work accident on a tractor), Anshel Wajcenberg, Ahron Openhajm, Moshe Kawalski, Henokh Arner, Adash Wajnberg, Kuba Korenfeld and others who are no longer here.

One by one, HaShomer dissolved, and then the HaShomer HaTzair [Socialist-Zionist secular youth organization] was founded, but this is a chapter itself.

The Będzin HaKoakh also was very popular and it

[Page 133]

seems to me that there was no young person, with the exception of the pious circle, who was not a member of the sport union, whose slogan was: “A healthy soul in a healthy body!” The HaKoakh was nationally disposed [Zionist] and throughout its long existence it endured declines and immigration to Eretz-Yisroel. Non-Zionist elements tried to expand their influence on it, but it remained true to the blue-white flag [the Zionist flag that is now the flag of Israel].

My teachers were Sztajnberg (perished) and friend Yankel Zoyberman (Tel-Aviv), both exceptional athletes, who always showed great mastery at gymnastic competitions and tournaments.

Do not have resentment, dear reader, that I have written at length. I have informed and reminded the reader of Pinkas Będzin [Będzin Yizkor Book] about our past, events and memories of Będzin ways. In the future, when those of us who remember this and speak of it will be no more, because there are very few survivors of those who were exterminated, and of destroyed and eternally orphaned Jewish Będzin where we spent our childhoods and youth.

Translator's footnotes:

by Abram Gold

Translated by Rita Ratson

Donated by Erin Einhorn

Over 50 years ago, the population of Będzin was almost entirely Jewish. The

city was laid out from the water mill to the “peasant gate” on

Kollataja Street that led to Dabrowa. If it weren't for the church on the hill

in the old market place, and the ruins of the royal castle of Kazimierz the

Great – one would be able to say, that in those years that Będzin was a

purely Jewish city. It was not easy to make a living. One did everything to

earn a precious piece of bread and because of this, there was no shortage of

teachers in the city, who made an effort to get as many children as possible of

businessmen who barely managed to keep their head above water into their

“cheders”. Every four-year-old boy studied with a teacher (someone

who taught the youngest children); where they learned the “aleph-bet”

and Hebrew, and then later they attended “cheder”, where they learned

Pentateuch [traditional Yiddish version of the Torah] and Talmud. The

aspiration of every father and mother was for his or her child up to be a

rabbi's assistant, a wise person or a cantor if he had a good voice. Parents

purchased less food in order to collect the money necessary to give their

children a proper education.

The “cheder” teachers were known in the city by their nicknames. My teacher was called Kalman “Katlass”, another: Nuchem “duck”, a third one Lajbisz “with a broad beard”. What did the “cheder” look like at that time? The entrance was straight in from the street into the house. A barrel of water stood on one side that Ephraim the water carrier had brought from the pump in the old market. From time to time the “Rebbetzin” [Rabbi's wife] sent the pupils out to bring back a pail of water. We happily carried out the Rebbetzin's wishes – we also rocked the baby, shopped for her food in various stores, and other errands – anything apart from having to sit at the Rebbe's table in fear. At the door stood a pail of dirty water, which we called the “slop pail”. Then there was an iron oven and a long table with two large benches where we, the “Gentile boys” (as we were called by the Rebbe) used to sit and study. The next room served as a room for the members of the teacher's household. The teacher used to have a “helper”, a strong young man, who used to go round and pick up the children every morning. He used to pick them up, a few children at a time, on his shoulders, in his arms and by the hand.

The teacher and his assistant taught the pupils the “aleph-bet” from a prayer book, while holding a wooden pointer and yelling loudly in our ears, demanding that we remember the letter and when our poor frightened soul did not allow us to remember the “aleph-bet”, the child received a real beating; and so many marks were left on the children. After about two years, when we completed the Torah in Hebrew, we progressed to the “cheder”, where we learned Chumash (Pentateuch – traditional Yiddish version of the Torah) and the first part of the Talmud. Despite this, the teachers did not earn enough to make a living and so their wives had to do whatever they could to help earn more money. They sold baked foods and so forth. During the intermediate days of Passover and Sukkoth, the class lessons ended and the teachers went from house to house to find new pupils. We did not learn worldly subjects in the “cheder”, apart from Russian, which was ordered by the Czarist government. Every child had to learn, by heart, the Czar's oath. On every Russian national holiday or birthday of one of the Czar's court, we went to the school and said prayers in honor of the Czar (for his good health) and for his friends and court.

When we were older, we stopped listening to the Rebbe, we went on to “yeshiva” or traveled on our own to learn in the Bet Hamidrash. Children from more worldly homes and families were able to continue to study in Wroncberg's synagogue, which at the time had already become a reformed school, made up of three classes in which they learned all sorts of subjects. This particular school was one of the best. Students from the whole region came to study there; if their parents were capable of paying the tuition for them. Hebrew was studied in Ashkenazi, the bible and the director, Mr. Wroncberg, taught grammar. He was a good Hebrew teacher and Talmudist. There was a different teacher for German and Russian; a private teacher taught Polish, because the Russian government forbade it. The teacher for Russian was a Gentile. Later on a relative of Wroncberg from Warsaw arrived. This teacher, Jehoszua Rapaport, taught thousands of students in Będzin up until the Holocaust period.

Also Szlomo Sabatke, born in Slomnik, one of Wroncberg's mentors, was an excellent teacher and extraordinary Hebraist. He began working independently some years later and opened a school of his own with great success.

In the school we were educated to have a national spirit; we learned about the origins of our holidays, not only the religious ones, but also the national ones. There also was a teacher, Iszajahu Jakob, who spoke Hebrew very well. He ran his school in the art house in the new market. His wife had a boarding school for Jewish children from Lithuania and Russia who used to study at the Russian school of Będzin, “Komerceskioje Ucilisze” [commercial junior high school] in Rubin Street in Nunberg's house.

In 1905, a Polish marketing school was founded, in which a small group of students from very worldly circles, studied. They had to go to school on Shabbat, as well. There was a school in Jechiel Wajner's house where Jewish students studied to be writers. They studied in the Russian language. They wrote petitions to the government. Girls from the level of society studied additional subjects and also a little “Yiddishkeit” in the two public schools belonging to Szmul Judl Rozenes in Zukerman's house and in Majer Lemel Sendiszew (died in Israel) and Blimele Sendiszew's house. When two Polish high schools for girls were established, managed by two women (Kszimowska and Ceplinska), both teachers gave up the schools and became storekeepers.

M. L. Sendiszew immigrated later on to Erez Israel together with his family. His son, Moszele, fell during the incidents of 1936-1939.

Girls from wealthier homes continued to study with Mrs. Mandelkorn. In Będzin

there were quite a few young men from Russia, who studied in our city because

of the many restrictions in their native towns. There, young men suffered a

great deal because of their ethnic background. They gave lessons in private

homes to the families' children. They wore special school uniforms with brass

buttons and special caps, because in the religious circles they were regarded

as Gentiles. They were welcomed by the enlightened families, who were seeking

worldly education and to become acquainted with foreign languages. Yiddish was

regarded as non-kosher. The language embarrassed secular people, not aware of

the fact that the greater portion of the city's population spoke Yiddish though

reading a Yiddish book was forbidden. Those who read a Yiddish book were

regarded as a “model to be emulated”. It took a long time till it was

accepted that Yiddish was a language and it worked against the assimilation

process.

[Page 134]

Yehiel Kaminski (Paris)

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish workers in our city did not have any special achievements and gains to record in the communal area. The Jewish worker intelligentsia were members of the Polish Social Democratic Party, which had a wide field of work [to do] among the Polish workers. They could speak to the Jewish workers in the Yiddish language, but the Jewish worker intelligentsia was influenced by Russian culture; [it] was detached from Yiddish and because of this could not maintain contact with the Yiddish-speaking worker.

The situation for the Jewish workers was very difficult. They worked 14 hours a day and even more and the pay was negligible: 30 rubles with food for an entire “term,” namely six months. That is how it was in the tailoring trade, but it was not better for other trades. Because of these difficult working conditions, it was easy for the Jewish worker parties, the Bund and Poalei-Tzion [Workers of Zion – Marxist-Zionist], to carry on widespread propaganda among the workers for improving their economic condition. The Bund, which arose in 1903 (and at that time was called Akhdus Yungen [Young Unity]), was the first one to penetrate the Jewish working classes.

Gaitermakers, shoemakers as well as maidservants were organized. The first strike took place in 1905 and involved all of the mentioned workers. The chief demand was: a 12-hour work day… Secret meetings took place wherever they could, even in the Gerer shtibl [Hasidic prayer house]. When the police learned about it through a denunciation about such a meeting in the Gerer shtibl, the meeting was attacked and shooting began. A great turmoil arose; the group dispersed. They jumped over fences, greatly hurt themselves and several were shot. This did not deter the workers from again assembling at conspiratorial meetings in the house of prayer and in the Talmud-Torah [free religious primary school for poor boys], which evoked little suspicion. When the police

[Page 135]

caught someone, they were arrested and received physical punishment, namely, lashes…

In 1906, the Bund decided to celebrate the 1st of May and it did not have a flag. What was to be done? Three comrades went into a large business owned by Chavale's daughter Faygele at the old market, laid a revolver on the table and demanded red cloth for a flag. The argument [made by the] revolver actually succeeded and they received cloth, which was enough for several flags… This was also how they acted at a strike.

There was a policeman named Jakubik who threw terror into all workers because of his cruelty and sadism when one fell into his hands. Out of the suspicion that all young men were socialists, he attacked Jews in the street and ordered them to show their arbe kanfes [four cornered, fringed garment worn by Orthodox Jewish men]… For whoever was not wearing tsitsis [fringes on an arbe-kanfes], it was a sign that he was a revolutionary and he received lashes. This evildoer, Jakubik, received the appropriate punishment: on a Shabbos [Sabbath] an attack was carried out against him and he was murdered in a bomb explosion. The Cossacks threw themselves at quiet, passing citizens who were hurrying home, shot into windows and several Jews perished in the shooting.

In the course of time, the Jewish worker trades developed very strongly. There were tailoring workshops that employed as many as five workers and more. The situation for other trades – confectionary, quilters, bakeries, shoemaking shops improved. Thanks to the workers being organized. The only “men of illustrious birth” who did not want to mix with the “common people” were the sellers in businesses, who were called subyektn [subjects]. A small number of them were organized by Poalei-Zion and others had no interest in organizing.

It lasted this way until the outbreak of the First World War, which led to a crisis in all trades as there was no work. Poverty was very great. A Jewish food committee arose, led by the local elite. The committee organized inexpensive kitchens.

In the summer of 1915, several members of the Polish Socialist Party (left wing) – Walter Szalc, Hafs, Samek Wajnciher (the brother of the Sejm [parliament] deputy, Dr. Salomon Wajnciher), Y. Kozlowski and Mrs. Bela Sukenik – called together several workers from the tailoring trade – Fishel, Yehiel Lander and the brothers, Moshe and Wolf and Yehiel Kaminski, in order to create a group that would lead the intellectual work. A program was developed of reports and lectures that were held in Polish, which we barely knew. We also learned the Polish language. The teacher was Mrs. Bela Sukenik.

In time our group expanded. New people joined and we thought about our own meeting place. A “tea hall” actually was created. The opening took place with great “pomp.” The managing committee worked out a plan of cultural work and it also was decided to give bread and tea without cost to each member of the “tea hall.”

The poverty was great and our financial means were small. We turned to the Jewish food committee and asked for a subsidy in order to expand our work and to expand our free distribution of lunch to our comrades. Our request was refused, which made our aid work difficult. We continued the work based on the means that were at our disposal until on a beautiful, clear day the “tea hall” was destroyed by the German regime because we were teaching the Polish language – but the cultural work continued in the group.

In March 1916 the Bundist activist, Maurycy Orzech, a co-worker of the Lebnsfragn [vital questions], came from Warsaw and gave a lecture to the group about the Jewish worker's movement. A heated discussion took place after the presentation, during which Kozlowski gave a speech that did not find favor among we Jewish workers, feeling that we had nothing in common with the assimilated circles.

Comrade Kon came again to us a month later and it was decided at a meeting with him to found the Bund in Bedzin, which had not existed for a time in our city. Simultaneously, with the help of Friend Berkowicz from Sosnowiec and Brukner from Dombrowa [D¹browa Górnicza], the Bundist organizations were founded in the two ZagŁębie cities.

In the same year, elections took place for the Bedzin city council, where the Bund elected as councilman Comrade Pesakhzon, and then the “groser klub” [large club] opened, which carried out cultural activities.

The Bund founded professional unions for tailors, shoemakers and bakers. The Poalei-Zion again [founded] porters and sellers unions. The Bund carried out cultural work and invited esteemed lecturers from Warsaw.

The Russian Revolution brought a great awakening in the Jewish worker's street. Large demonstrations of all workers organizations took place, in which the Bund and Poalei-Zion were strongly represented. The Polish workers had sent out the slogan of worker and soldiers councils and the Jewish political workers unions were called upon to send their delegations. There were three delegates from Poalei-Zion and two from the Bund – Henrik Fajerman and the writer of these lines.

When Pilsudski drove out the worker and soldier councils (1918) and the people were arrested, a large number of them left the country and immigrated and I with them.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bedzin, Poland

Bedzin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 20 Nov 2020 by LA