|

|

|

[Page 631]

By T. Brustyn-Bernstein

|

|

The following work consists essentially of excerpts from the work of T. Brustyn - Bernstein, which appeared in Folio Number 1-2 of the third volume (January-June 1950) of the ‘Pages for History’ which was produced in Warsaw (as a quarterly periodical of the Jewish Historical Institute in Poland).

The work of T. Brustyn-Bernstein is divided into two parts:

1. The Lublin City area; 2. Biala-Podolsk area; 3. Bilgoraj area; 4. Chelm area; 5. Hrubieszow area; 6. Janow-Lubelsk area; 7. Krasnystaw area; 8. Lublin area; 9. Fulow area; 10. Radzyn area.

We convey the second chapter in its entirety.

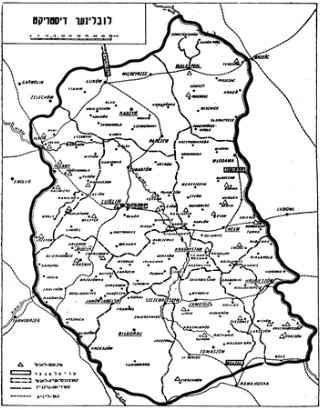

We also insert a map of the Lublin District with the Nazi torture and extermination camps that were located in that area, such as: work camps; death camps; concentration camps. Bitter fate decreed, that on the territory of this area, were, apart from tens of Nazi ‘institutions,’ three of the most horrible Hitlerist death camps: Majdanek, Sobibor and Belzec. The last, and most gruesome of all, was indeed in the vicinity of Zamość.

In bringing the excerpts from the work of T. Brustyn-Bernstein, we omit all of the sources and footnotes; all comments and references to sources.

In thinking about the problem of the expulsion of the Jewish population in the Lublin District, in the time of the Hitlerist occupation, it is necessary to show the relationship between the movement created by this forced emigration, and the Hitlerist plans to wipe out the Jewish population. By acquainting ourselves with these plans, will enable us to understand the reasons for the Hitlerist ‘evacuations’ – and the ‘evacuation aktionen.’ Without exhausting this theme, we will further we will further direct the reader's attention to the plan of the Lublin Jewish host, to the plan to transfer all of the Jews to Madagascar, and similarly to the plan of the so-called ‘evacuation,’ of the Jews to the East.

During the period of The Second World War, 6 million Jews were murdered in Europe, of which 4 million were killed in death camps.[1]

In his speech that Hitler gave in January 1939, he pronounced upon the extermination of Jews. With the practical realization of ‘The Solution to the Jewish Question,’ Reichsmarschall Goering promoted Reinhard Heydrich, on

[Page 632]

January 27, 1939 to be chief of the ‘Reichssicherheitsdienst-Hauptamt.[2]’ A central emigration authority for Jews was established under Heydrich's leadership, which was to intensify and accelerate the emigration of Jews from the Reich, Austria and the Protectorate. At that time, systematic pursuit of the Jewish populace was already being instituted, including confiscation of assets, arrests and being re-settled in concentration camps.

After the outbreak of the war with Poland, the Jewish Problem was put down sharply on the current agenda. Even before the war operations were ended in Poland, Heydrich, on September 21, 1939, sent out identical instructions on how to handle the Jewish population, to all the chiefs of the Einsatzgruppen of the Sicherheitsdienst Polizei in the occupied territories. Through them, a boundary is created between the ‘end state’ and the general themes, which have to be realized in order to reach the final goal.

Heydrich's instructions recommend to concentrate the Jewish population in cities that lie along communication links; these instructions formulate the missions of the Judenrats, the goals of the economic-politics opposite the Jewish population, and touch on the question of driving the Jewish population, in these territories, which had become integrated into the Reich, to the margin.

The outbreak of the war had simultaneously precipitated a strong migration-movement in Polish territories. Even before the end of the September campaign, while war operations were still going on, a mighty wave of refugees goes, especially from Western Poland to the East, to seek a place of refuge in the larger cities, especially Warsaw.

As a result of this, specific transformations took place in the territorial distribution of Jews. After the end of military operations (end of September), until December 1939, there was again an outflow of the Jewish population from the territories to the areas that were occupied by the Red Army, and in other countries. A large portion remained in their new places, resigning themselves to not returning to their homes.

In connection to the plan to set the Jews to the side in the German ‘lebensraum,’ the Hitlerist authority decided to create an ‘Evacuation Area’ in the General Government District of the Lublin province, which it designated as a ‘Reservation’ for Jews. It was intended to take in Jews from Europe, as well as Polish areas, which had been united with the Reich.

In October 1939, the Jewish community of Vienna received an order to present 1000 Jews for the ‘Reservation.’ By October 20, 1939 the first transport with Viennese Jews had already left in the direction of the General Government District. During October, 1,672 Viennese Jews arrived in the General Government District. In the final months of 1939, a couple of thousand Jews were deported from Czechoslovakia, a certain part of them had hoped to be able to cross the border into the Soviet Union and hoped thereby to save themselves. On the strength of Hitler's order of October 30, 1939, a wave of Jewish refugees streamed into the General Government District from the incorporated Polish territories. Those driven out of Kalisz, Kwil, Lodz, Suwalki, Serock, Naszelsk, and from other cities of Western and Northern Poland, spread out in almost all of the cities and towns in the General Government District.

Over 1,000 Jews from Sczuczin were brought into the Lublin vicinity in February 1940. In the process, a large number of victims fell.

The broadly-based deportation into the General Government District was only now supposed to start. Namely, the arrival of 400,00 Jews was foreseen, starting on May 1, 1940. After the incidents with the first of the transports, the difficulties of dividing up the mass of humanity not only in the Lublin vicinity were very great, but also throughout the entire General Government District.

The Governor of the General District, Frank, began to make efforts with the decision making elements in the direction of abandoning this plan. Simultaneously, the debate over Jewish issues in the division, ‘Internal management, population oversight, and direction,’ in the General Government District, having information about the projected deportations of foreign Jews into the General Government District, distributed, on April 6, 1940, a questionnaire to all the District

[Page 633]

Governors, in order to be able to orient itself regarding the options, and to find a suitable parcel for the Jewish ‘Evacuation-Area.’ The Governors were required to reply to the following questions:

Paying no heed to the preparations, the projected mass deportations didn't come to pass. On March 23, 1940, Goering issued an order to stop the anticipated evacuation of the populace. On the strength of available source material, it is hard to pinpoint precisely if this came about because of the pressure applied by Frank. It also appears there is the possibility, that in connection with the planned German expansion into Western Europe (Norway, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg) in April, May 1940, and with the preparations for the French campaign, it was held that it was not timely to absorb the transport [demand] occasioned by the Jewish deportations.

In the elapsed time of the French campaign, which began on May 10, and ended shortly thereafter, in the months of July-August of the year, the Hitlerists engaged themselves with the ‘concept’ of ‘solving’ the Jewish Question through the forced emigration of European Jewry to colonies occupied by colored races…

… Regarding plans to deport the Jews to the French island of Madagascar, which France would cede to Germany as part of a peace agreement, is also discussed in the correspondence of the Hitlerist diplomats. As late as August 1940, such a ‘solution’ to the Jewish Question remained under consideration in these circles.

At this point, it is difficult to establish if the abandonment of this plan about Madagascar was really decided on by Himmler as a result of his realization. It is possible that this was a convenient screen for complete extermination of the Jews at that time, when it was not yet possible to carry out the deportation plan simultaneously. One thing can be definitely established: The technical preparations for deporting the Jews to Madagascar had not yet even been started. It was the opposite – at the end of the summer of 1940, the name of Madagascar is no longer mentioned entirely. Rather quickly, Frank made peace with the idea that the foreign Jews were going to be deported to the General Government District. The order to evacuate the Jews to the East was issued in the early fall of 1940, in the time when the date for the invasion of the Soviet Union had already been set…

…On July 31, 1941, Goering tasked Heydrich with the mission to make all of the organization and financial preparations for the ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question,’ in those territories under German control in Europe. Simultaneously, Heydrich received an order that, in a short time, [he was] to send Goering an exact plan about the organizational, materiel and practical measures which are necessary for the desired ‘solution,’ of the Jewish problem. In other words – Heydrich received the task to work out a plan to construct the processes for the mass murder of human beings, as well as those for the deportation of the Jews from a variety of lands into those places.

Hitlerism approached the realization of its ultimate goal, to eradicate the Jews of Europe. The Governor of the General District, Frank, at a government meeting on September 9, 1941, informed the participants as follows, regarding Jewish issues:

‘The Jews must disappear! They must remove themselves from this place. I have engaged in undertakings to drive them out to the East. In January, a conference on this matter will take place in Berlin, to which we will send the government secretary Beuhler. The conference is supposed to take place at the Reichssicherheits-Hauptamt sponsored by SS Obergruppenfuhrer Heydrich. In any event,

[Page 634]

a great displacement of Jews is going to take place. But what is to happen to the Jews? Do you think, they will be settled in the lands of the east, or in the Reichskommisariat (Ukraine) in the ‘Evacuation-villages?’ In Berlin we were told: Why are all of these excuses being made? We can't do anything with them in the Eastern territories, and in the Reichskommisariat, liquidate them yourselves.’

Frank expresses himself here frequently: The two and a half million Jews have to be liquidated. He is only interested in the techniques of extermination. And here are his additional thoughts:

‘We cannot shoot them all, we cannot poison them all, but we will have to adopt such methods, whatever they may be, that will lead to their extermination.’

These mass methods are today generally known, these are the gas chambers and crematoria.

For Jews in the ‘Wartheland[3]’ whom they decided not to bring to the General Government District, but exterminate on the spot, a camp was built in Chelmno, near Kolo which began to function on December 8, 1941. In this extermination camp, the larger majority of the Jewish population in this [sic: Kolo] province met their death, as well as 20,000 Jews from Prague, Vienna, Berlin, Köln, and other German cities, who, in the period from October 17 to November 4, underwent ‘evacuation’ [in which people were sent] to Lodz.[4]

The conference in the Reichssicherheitedienst-Hauptamt, promised in September 1941, took place in January 1942, and had as its objective to coordination of all resources, which were needed to prepare the extermination of European Jews in the death camps.[5]

Heydrich acquainted the attendees with the numerical status of the Jews in all European countries, not excluding England and Switzerland. According to his data, Europe had 11 million Jews…

…At the end of October 1941, the construction of the first extermination camp in the General Government District began at Belzec, and it was completed at the end of February 1942. It began to operate in the middle of March. Initially Jews from the Lublin District were sent to Belzec, later on, especially from the two southern districts: Krakow and Galicia. In May, the extermination camp at Sobibor began to operate, and in July – in Treblinka.

[Page 635]

In March 1942, transports with foreign Jews began to arrive. They were distributed to places along the Deblin [sic: Deblin]-Rejowiec [Fabryczny]-Belzyce rail line.

The German administration in the Lublin District, in accord with the Full authority of the SS and leaders of the police, firmly established that to the extent that Jews were to be ‘evacuated in’ from foreign locations, a like amount of local Jews will be ‘evacuated out.’ The organs of the police recommended sites for such ‘abusing out,’ first of all the element that was incapable of doing work. In the General Government District, the extermination aktion against the Jewish population began in March 1942, and by November the majority of the Jews that were displaced in this manner, were already murdered…

Expulsion and Extermination of the Settlements in the Lublin District In the Form of Numbers and Data

The Hitlerist occupation washed all the Jewish settlements of Poland off the surface of the land.

In the annals of the research about Jews under the Hitlerist occupation, the Jewish Historical Institute approached the task of working out the problem of the extermination of Polish Jews in the hundreds of cities and towns, in a systematic manner in the form of tables.

In connection with this, it was necessary, first of all, to establish with certainty, the condition of the Jewish population in each settlement that was ultimately destroyed.

Seeing that the population in all of the settlements underwent significant change in comparison to the pre-war figures, it is necessary to take figures into consideration from both periods. The difference in the figures of the Jewish population of both periods in the different settlements is a result not only of the wanderings of the period during war operations, or mass flight to the Soviet Union, sporadic ‘aktionen’ and high death rates, but especially because of the ‘outward expulsions’ or expulsions into locations, of the Jewish populace, which the occupying Hitlerist forces carried out with force. In specific locations, a concentration of the Jewish population took place, and in others –the opposite – the Jews were gradually, or entirely deported to other places.

In this so-to-speak chaos there was, however, a planned process: all the forced emigration-movements, that means – expulsions of the Jewish populace during the time of the occupation, were aligned in accordance with the concepts of the so-called ‘solution,’ of the Jewish Problem, and were, generally speaking, a realization of the related themes of one process of the ‘Final Solution,’ meaning the physical extermination of the Jewish population. Accordingly, it was deemed necessary to confirm the table of the related rubrics, which contain the given methods of the ‘forced expulsions’ and ‘forced concentrations,’ which took place as a frequent prelude to the extermination process.

However, it is not always possible to depend on the available sources to quantitatively apprehend the given expulsion movements, and part of the time, one can only estimate the number of people that were forced to change their place of domicile to date, and there are times when one must simply resign one's self from the possibility of providing concrete figures. Also, because of a lack of sources, we have to resign ourselves from providing even estimates relative to the extermination aktionen.

Seeing that the local police and administrative organs took part in the extermination of the Jews, it appeared to be necessary to include in the tables the participation of the occupied administrative agents in district. In each district, there were allocated principal leadership positions, which represent more-or-less our locations, but in general, a ‘circle’ was greater than a ‘location.’

The Lublin District, divided into ten ‘kreis-hauptmanschaften’ encompassed 14 ‘Powiats’ of the former Lublin ‘Voievode.’ The remaining 4 Powiats of the Lublin Voievode were integrated into the Warsaw District.

[Page 636]

The following Powiats became part of the Lublin District: Biala-Podlaska, Bilgoraj, Chelm, Hrubieszow, Janow, Krasnystaw, Lublin, the larger part of the Lukow powiat, Pulawy, Radzyn, Tomaszow, Wlodawa, as well as a small number of settlements from the former Lemberg Voievode: Lubachow (Ciechanow settlement), Nisko (Ulanov settlement), Rawa-Ruska (Belzec settlement), Sokol (Belz settlement) and Tarnobrzeg.

Moving now to refer to the introductions to the various representations in our tables, we will stress that for the first two representations we especially took materials from the two act-complexes – ‘Joint’ and ‘Jewish Social Independent Relief Organization’ (Y. S. O.) In the Lublin District, there were a hundred and several Jewish settlements to be found, who, during the time of the occupation, had contacts with the ‘Joint’ and the central [office] of the ‘Jewish Social Independent Relief Organization.’ in Krakow.

In order to place the statistics from before the year 1939 on a solid foundation, we made use of the monthly compilations of the central [office] of the ‘Jewish Social Independent Relief Organization’ in Krakow. These compilations were assembled from printed formulas, which addressed in the first point, a question about the number of Jews before the war. We have, in part, aligned these numbers with the statistical submissions, which the municipal leadership offices sent into the Institute in the years 1948-1949.

The number of the Jewish population changes in the separate settlements from month to month. At the beginning of 1940, during the first wave of refugees that cascaded over the General Government District, the ‘Joint’ made efforts to gather together materials about the number of refugees from every individual location. However, no precise replies came back to the ‘Joint’ from the various Judenrats, in response to their inquiries, seeing that the mass of refugees found itself in an very fluid situation, that is, in a condition of being constantly on the move, and in general, a large number of them missed out entirely on being registered, not wanting to be counted among those who receive aid. The reason for this ricocheting from place to place is clarified in a ‘Joint’ report in the following manner: ‘The refugees, being compressed in some location or another, in an impoverished and destroyed shtetl, without any prospects to order themselves there, often wander off to neighboring towns, where they hope to find some small possibility to sustain their existence.’

In the middle of February 1941, the order of the Lublin Governor Zerner went into force about limiting the rights of domicile of the Jewish populace, which expressed itself in the prohibition to leave whatever was their current residence.

The possibilities for a legal move were taken to a minimum. In the referenced period, there were between 250,000 and 300,000 Jews living in the Lublin District.

At the end of March, or the beginning of April 1940, the Advisor to the Head of the Lublin District of the ‘Jewish Social Independent Relief Organization,’ Dr. Alten, sent a special questionnaire to all the divisions of the Jewish Social Independent Relief Organization, on behalf of the Organization for Social assistance. The statistical material so assembled enables us to set with some certainty the number of Jews in the separate ‘Kreis-Hauptmanschaften,’ as well as in the locations. Underneath, we bring a list of the number of Jews, in the ‘Kreis-Hauptmanschaften’ from the Lublin District in the years 1941, 1942, on the basis of Alten's inquiry from March, April 1941, as well as from the material from the Y.S.O. on July 1, 1942.

But first we will note that the differences in the figures of the Jewish population in the ‘Kreis-Hauptmanschaften’ Lublin, Pulawy, and Radzyn consist not only of the ‘evacuations both in and out,’ but also because of changes to the boundaries between these areas. In August 1941, a portion of the Radzyn was integrated into the ‘Kreis-Hauptmanschaften’ of Lublin and Pulawy. That is, the former region of Lubartow with the cities of Lubartow, Firlei, Kamienka, and Ostrow was detached from the Radzyn ‘Kreis-Hauptmanschaft’ and united with the ‘Kreis-Hauptmanschaft’ of the Lublin-Land. By contrast, the village areas of Wielki, Mikhov, and Lisowiki, were integrated into the Pulawy Kreis.

These totaled figures that are presented have to be considered to be lower that reality, since in the material from Alten's questionnaire there are figures missing for specific cities, for example: Cuzmir, Konskowola, Baranow. Apart from this,

[Page 637]

it appears that the Jewish populace was scattered in the villages and therefore there was no contact kept with the Y. S. O. and therefore not captured in this questionnaire.

Looking through the representations of the count of the Jewish population in the separate locations and aligning the pre-war figures with the numbers from the time of the occupation, in a part of the places we will take note a catastrophic drop in the population count in the time of the occupation. In other places, a contrast mostly – an increase. A drop in the population occurred in those places which were bombed and destroyed during the September campaign of 1939 (for example, Frampol, Bilgoraj, Krasnobrod, and others).

In general, the number of the Jewish population grew in a meaningful amount in almost all settlements, disregarding the fact that thousands of Jews in the fall of 1939 abandoned their homes and saved themselves [by going ]into areas which were liberated by the Soviet Union. In part of the towns, the number of refugees and exiles exceeded the count of the local residents (in Turobin, for example, from 1,400 – a growth of 3,300, Belzec – from 2,200 to 4,854).

| Kreis-Hauptmanschaft | Population in March, April 1941 | Population on July 1, 1942 |

| Biala-Podlaska | (12,132 Natives + 5,542 Refugees) 17,674 | (almost 5,000 Refugees) 14,500 |

| Bilgoraj | (3,069 + 9,181) 12,250 | 13,500 |

| Chelm | (3,669 + 24,528) 28,197 | (3,437) 20,955 |

| Hrubieszow | (1,279 + 8,514) 9,793 | 4,650 |

| Janow-Lubelsk | (4,713 + 13,368) 18,081 | (1,735) 17,243 |

| Krasnystaw | (5,187 + 11,399) 16,586 | (3,569) 8,435 |

| Lublin | (3,866 + 13,356) 17,222 | (10,500) 23,800 |

| Lublin (City) | (6,000 + 39,000) 45,000 | In Majdan Tatarski 4,000 |

| Pulawy (Kreis) | (5,213 + 15,388) 20,601 | 26,000 |

| Radzyn | (12,998 + 34,988) 47,986 | (14,431) 42,239 |

| Zamość | (3,700 + 11,512) 15,221 | (3,500) 9,000 |

| Total | (55,245 + 193,366) 248,611 | 184,322 |

It is necessary to remark that not every rise or fall in the population count can be explained by the entries in the table, since not all the movements of the Jewish population in the District can be established on the basis of the available sources. Apart from this, the impact of deaths, shootings and deportation to labor camps, changes in domicile (illegal, or for other reasons) etc. have not been taken into account.

Looking through Table X, we observe an expulsion of the Jews from Lubartow and Radzyn in the last months of 1939. Later, the implementation of the order concerning the expulsion was annulled and part of the populace returned home.

Pulawy was the first city in the Lublin District, from which the Jews were driven out into a variety of towns, as early as December 1939. No Jewish laborers were even left behind to work at cleaning out the city. First later, when the press of the lack of a labor force was felt, several tens of Jews were brought to Pulawy, for whom a camp was built on the spot.

[Page 638]

The expulsion of the Jews from Lublin, and a couple of the larger cities, was carried out from February - May 1941, at the time that German forces were being concentrated in Lublin for the attack on the Soviet Union.

In February 1941, part of the Jews from Krasnik, which was overflowing with German military forces, were driven out to Radomysl, Tzhidnik and Koszyn. Over 10,000 Jews from Lublin were, in the months of April-May 1941, were tossed into the cities and towns of the District, the rest were closed off in a ghetto. The places, into which the Jewish populace was driven, were agreed to by the administrative organs, in concert with the military authorities.

In April, 800 Jews were driven from Bilgoraj to Goraj, and over 600 from Zamość to Komarow and Krasnobrod, and in May there took place an expulsion of over 1,000 Jews from Krasnystaw into a variety of locales of the area.

Analyzing the representations of the ‘evacuations in,’ it is possible to establish with confidence three waves of ‘evacuations in,’ that took place from outside the General Government Province, which stands in relation to the so-called ‘solution’ of the Jewish Question on a European scale. The first wave falls out on the last months of 1939 and the first months of 1940, that means, in the period, when the concept was adopted of creating a Jewish ‘reservation,’ in the Lublin District. In that period, the Jews of Serock, Suwalk, Nowy Dwor, Kalisz, Lodz, Szeradz, Zgerz, Kolo, Konin were driven in, and an array from other cities, that had been absorbed into the German Reich. In February 1940, the transport arrived from Szczecin. It has not been possible to establish, based on the sources, where the Jews who arrived from Vienna at the end of 1939, settled down.

The second wave of ‘evacuations in’ falls at the end of 1940 until March 1941, that is, in the period when the decision had already been taken to send the European Jews to the East.

In December 1940, part of the Jews from Mlawa (the Ciechanow Kreis) and its environs were driven out, into the General Province. Initially, they were held for a couple of weeks in a camp in Zaludowo. They cam in a frightening condition, without baggage, and without the means to sustain themselves. They were thrown into Biala-Podlaska, Wisznica (In the Biala Area), in Kamienka (Lublin), Mikhov (Pulawy), Cziemierniki and Lukow (Radzyn). A small number of the Jews of Mlawa were settled in Sosnivka near Parczew, in January 1941.

In March 1941, a transport arrived with 1,100 who had been driven out of the Kanin area (Warthegau), a portion were let off at the train station in Izbica, and the rest at the station in Jozefów near Bilgoraj. Seeing that the Jewish communities in those places were in no position to share in the fate of the uprooted ones, the latter sought a place of refuge in the villages in the entire Kreis. In the months of February-March 1941, 5,000 Jews were evacuated from Vienna, who were divided up among the communities of Modliborzyce, Finiz (Janow Area), in Opole (Pulawy). Close to 200 Viennese Jews (over 100 from Opole) got the chance to illegally return to Vienna, but they were looked for there, and arrested. At that time, they declared that they would rather sit in the Viennese jail rather that go back to the General Government Province, but the ‘Zentralstelle fur Auswanderung’ in Vienna send them back to the General Government Province anyway.

In December 1940, a transport of 5,000 Jews arrived from Krakow, and additional transports from Krakow arrived in the months of March and November 1941, in connection with the aktion to ‘Clean Out the Jews’ from Krakow.

The third wave of ‘evacuations in,’ brought the Jews from Mielec, in March 1942, and between March and June 1942, tens of thousands Slovakian, Czech, German and Austrian Jews.

The preparations to marginalize the 4,500 Jews from Mielec and its environs began in January 1942, the aktion took place on the 9th of March, [and] on the 11th and 15th of March two transports left Mielec. Young, able-bodied men who could work were separated from their families, and sent to work.

The first transport was tossed into the ghettoes of Miedzyrzec, Wlodawa, Sosnivka, and into the abandoned houses of Ciechanow. The second transport was divided into three parts in Zamość, one was sent off to the Hrubieszow area (Belz, Dubienka), the second was let off at the station in Susiec, from where it arrived quickly at Belzec – to death.

[Page 639]

In March 1942, together with the administrative apparatus, the Hitlerist police authorities undertook to research places where it would be possible to accommodate 60,000 Jews from outside the country. The intent was to select locations that lay along the rail lines from Deblin to Trawniki, and Deblin - Rejowiec - Belzec. It is difficult to specify exactly how many Jews from outside the country came into the Lublin District. Part of the transports were sent directly to the extermination camps of Sobibor, Belzec, or to the concentration camp at Majdanek.

According to the calculation of the ‘Reichsicherheits-Hauptmacht’ who in January 1942 planned the extermination of 11 million European Jews, there were in Germany 131,800, in Austria 43,700, in the Czech Protectorate 74,000, in Slovakia 88,000. The sum total for these previously mentioned four countries came to 340,000 Jews.

In the spring of 1942, these Jews from outside countries were deported and distributed to locations that lay close to rail lines that lead to the extermination camps of Belzec and Sobibor. In Piaski, a large concentration point was created for the Jews of the Reich. In March 1942, the Jews from foreign transports were debarked in Izbica, Krasniczyn, Gorzkow (in the Krasnystaw area), in April – in Izbica and Krasniczyn, as well as Rejowiec, Siedliska, Wlodawa, Ostrow, Piaski; In May – in Rejowiec, Chelm, Krasnystaw, Ostrow, Belzec, Deblin, Konska Wola, Opole, Ryki, Lukow, Miedzyrzec, Zamość, and Komarow, and in June – in Konska Wola. Most of the time, when the foreign transports would arrive in the Lublin area, an ‘abusing out’ would take place from the local ghettoes.

On March 16, 1942, Hofle[6], the representative of ‘Operation Reinhard’ presented the status for Jewish issues in the section ‘Population Indicators and Management Issues,’ from the Lublin District, that he is in a position to accept 4-5 transports a day of 1,000 people apiece at the Belzec station, cynically assuring that ‘these Jews will never again get through the [camp] boundary back into the General Province.’

On the morrow, March 17, the Hitlerist executioners began their murdering work, in the General-Government District, of ‘abusing out’ the Jews of Lublin to Belzec. This aktion lasted for the entire month, and in the end, a couple of thousand Jews, who remained alive, were transferred to a ghetto in Majdan-Tatarski, near Lublin. At the end of March all the Jews were ‘evacuated out’ of Cuzmir near the Vistula, and only a small camp remained for the Jewish laborers who worked in a stone quarry.

In March, 3,400 Jews were ‘evacuated out’ of Piaski, to which, at the beginning of April, 4,200 Jews were brought in from the Reich and its Protectorate. In the same month, a second ‘abusing out’ took place. Simultaneously, close to 1,000 Jews were ‘evacuated in’ from the Protectorate. This same thing was repeated in Izbica: in March 2,200 Jews were ‘evacuated out’ and in their place, two transports were brought from the Protectorate; in April the second ‘abusing out’ took place, after which three transports from the Reich arrived in Izbica, one transport from Vienna, all together – nearly 7,000 Jews.

[Page 640]

The aktionen to ‘evacuate out’ took place in the Lublin District without interruption until November 1942. The gas chambers of Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, digested fresh victims continuously.

From the 6th to the 12th of May, 16,822 Jews from the Pulawy area alone were exterminated. Along with the ‘abusing out,’ aktionen would take place, that means that the sick and the old, who did not have the strength to make the trip, were shot on the spot, as well as those who were dragged out of hiding places. There were instances, when instead of being sent to the death camp, the liquidation was carried out on the spot through mass shootings. In Jozefów, for example, in July 1942, 1,500 Jews were shot outside the city, in Lomazy (The Biala-Podlaska area) all the local Jews, in the amount of 1,700 souls, were murdered in the forest near the city, in August 1942

The concentration of Jews in ghettoes, who lived in the village settlements would take place shortly before an ‘abusing out’ aktion in those ghettoes.

It was in this fashion, for example, that the Jews of Biala-Podlaska were permitted to remain in their place only until the end of September 1942, after which date, everyone had to be transferred to Miedzyrzec. Starting from the beginning of October, daily transports would leave Miedzyrzec for the extermination camps. In that same month, the Jewish population from the surrounding settlements was concentrated in the cities of Lubartow, Lukow, Wlodawa, Krasnik, Zazolkiew, almost directly before the ‘abusing out’ in those very cities.

The extermination aktion in the month of October was carried out very intensively. At the beginning of November, the last of the Jewish settlements in the Lublin District were wiped out.

In between, however, a police order was published on October 28, 1942, signed by the senior SS and Police leader in the General Government Province, Krüger, ‘Concerning the Creation of Jewish Residential Districts in the Areas of Warsaw and Lublin.’ The order included a list of the cities and areas of the Lublin District where such Jewish districts were being created, such as: Lukow, Parczew, Miedzyrzec, Wlodawa, Konska Wola, Piaski, Zazolkiew, and Izbica.

In the second paragraph of the order, the date is specified – November 30, 1942 – until which time, all the Jews in the Warsaw and Lublin areas must select a place to live, in the Jewish districts. The order did not apply to those Jews engaged in wartime or ammunition industries, who were located in closed camps. Violation of this order was seen to be punishable by death. Also, punishment by death was the threat that appeared to be the case for those who would deliberately shelter a Jew outside the ghetto.

This order, which was manifestly seen to create the illusion of security, simply served as a net to trapped the dispersed stragglers among the Jews, who had managed to save themselves from the slaughter. The ‘lifetime’ of these ‘Jewish Districts’ was a very short one. It is worth emphasizing that from these eight cities, which were enumerated in the order of October 28, 1942, three cities: Parczew, Konska Wola, and Zazolkiew were already Judenrein by December 1, 1942. In October and the beginning of November, these ghettoes were entirely brought to extinction. On December 1, 1942, there still existed five ghettoes in the Lublin District (Piaski, Wlodawa, Izbica, Lukow, Miedzyrzec), they were largely liquidated in 1943, that is, –In February or March, the ghetto at Piaski; in April-May – all the others. In May 1942, almost all of the Jews were ‘evacuated out’ of Miedzyrzec and the ghetto officially ceased to exist. The last aktion in Miedzyrzec took place in July 1943.

The Jewish labor force that remained alive in the camps that were populous, and work places, were employed in improvement works in the land areas and in the peat bogs, Jewish craftsmen – in factories, who produced the necessities for the Reichswehr. The ghetto of Miedzyrzec, where there were factories with 900 qualified brush makers, the German manager of these brush factories demanded that a guard of firemen be placed during the time of the action, to protect his Jewish workers…

However, these Jewish workplaces and Jewish work camps, with few exceptions, were liquidated in the year 1943. The liquidation of the Jewish labor forces came about in the following order: the Jewish workers at the workplaces in Chelm

[Page 641]

were shot on March 31, 1943, at the end of April, the work camps in Leczna and Wlodawa were disbanded, from Rejowiec, part of the workers were sent to Majdanek. The camp residents in

| Number: 7 | Location: | Zamość | |

| Pre-War | 1941 | 1942 | |

| Number of Jews: | 12,000 | 7,500 | 7,500 |

| (2,500 local, 5,000 outsiders) | (4,056 - sp. Footnote) | ||

| Transfers: | 1941 | ||

| 400 - To Komarow | |||

| 248 - To Krasnobrod (People evacuated in from Wloclawek and Lodz) | |||

| Evacuated In | 1939 | 1941 | 1942 |

| 175 from Kolo, from Wloclawek | 78 from Czestochowa | 2,100 from the Reich Protectorate | |

| 1942 | 1943 | ||

| Evacuated out and Exterminated | 3,000 to Belzec | Beginning of 1943 to the Camp in Majdanek | |

| To Belzec | |||

| 500-600 to Belzec | |||

| Close to 400 to Belzec | |||

| Close to 400 to Izbica |

Belzec were sent to Budzyn (Majdanek-Filia) in May, from one camp in Deblin, everyone was sent to Poniatowo, in July the residual stragglers from the Jewish work forces were transferred from Rejowiec to Majdanek. 200 people, employed in Hrubieszow in the sorting of effects of Jewish origin, were in July or September 1943, sent off to Budzyn.

In the first days of November 1943, an enormous slaughter took place in Majdanek, of over 18,000 Jews, among them, the Jewish workers from two Lublin camps at Lipovo-Gasse and also on the airfield (Plaga and Leszkewicz), and at the same time, the Jews in the camps of Poniatowo and Trawniki were murdered.

Up to July 22, 1944, that means up to the day of the liberation of the Lublin District from German occupation, there were, in sum total, two Jewish work camps active in Deblin and Krasnik. At the last minute. The management of the camp sought to evacuate part of the camp inmates to the west.

Translator's footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zamość, Poland

Zamość, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 14 Mar 2024 by JH