|

|

|

[Page 412]

by Moshe Kezman

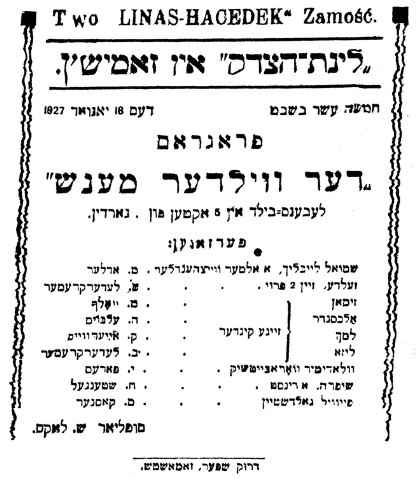

The ‘Linat HaTzedek’

|

|

The objective of ‘Linat HaTzedek’ was: to give help to Jews who were ill, who have to rely on strangers; people would come to spend the night with them (‘Linot’), provide them with financial assistance; medicine free of charge – whether for doctor visits or for prescriptions. An account was opened with the pharmacies, where the prescriptions from the ‘Linat HaTzedek’ were filled for the necessary medications or medical instruments.

At the office of the ‘Linat HaTzedek’ itself, there was a certain inventory of ready-made prescriptions, preparations and instruments, which were distributed to the needy.

There was always someone on duty at the office of the institution, who always dealt with those who would come about issues concerning the sick.

The work of the members was connected to a personal dedication and dangers. It would always transpire that it was necessary to stay up with those who were seriously ill, with sick people that had frightening diseases. There were sick people, who from prolonged illness, were literally rotting away. They had to be washed, and their linens changed…. the members did work that even hired nurses and sanitary workers would decline to do.

Raising money for ‘Linat HaTzedek’ was very difficult. The needed funds were obtained only with the greatest difficulty – by canvassing the houses, to collect monthly donations, collecting at times of celebration and circumcisions, and from time-to-time also at specially prepared events. Also, ‘Purim Money’ was collected for the institution.

I do not remember all of the leadership members, but a few need to have their names made public. The chairman was Berel Essigmakher (or Weinmakher)[1] – in his house in the Ghetto in the Neustadt was the minyan where prayers were said every day. That too, entailed risk to life and limb. Shlomo David Fershtendig, Akiva Eierweiss, Mishe-Yekel Stern, Eliyahu Zwillich.

The institution was very important, and also obtained a subsidy from the Jewish community.

The Yiddish-Polish Gymnasium

On a certain Friday night, a group of Jews were standing around, as was the custom, in the ‘little orchard,’ and among other things, the talk came to the Polish Gymnasium . Part of the parents argues – they would send their children to the Gymnasium, but there was an unofficial ‘Numerus Clausus’ that seemed to prevail there – often nothing is said, that they don't accept Jewish students, but difficulties are created, and that it is not easy to gain entry there.

This issue didn't affect me directly, because both of my sisters and also my daughter were already students in the Polish Gymnasium and one sister was already a student at the Polish [sic: Teacher's] Seminary. However, I felt in all of this, that perhaps something could be done, and I reacted by saying that it would be possible to establish a Yiddish-Polish Gymnasium. There is a location – a building which at one time had been built for the Jewish Hospital and is the property of the community and there does not seem to be any prospect for its use as a hospital.

[Page 413]

Among those who participated in this conversation were also my party friends and good neighbors, Shlomo Fein, and Moshe Genzler. They seized upon the notion, but the question was where would one obtain so large a sum of money, and more to the point, where would one find the qualified people who will dedicate time to this matter, and indeed, the relevant skills, specialties that are required to manage such an institution as a Gymnasium…

So, it gave me the opportunity to say: – Give me only two people who will commit themselves to this, and there will be a Gymnasium for Jewish children. Fein and Genzler presented themselves to me to make the plan into a reality.

That same Saturday, 30 me, well acquainted with one another, got together. Placards could not be prepared or posted on the Sabbath. Nevertheless, those who were interested were brought together. The assembly took place on Saturday, after the noon hour, in the location of the community.

It was decided to call for a second, broader meeting, on a Saturday that was not too far off. Placards were posted in all places where prayer services were held, and on that second Saturday, we had more than 100 parents already, who were interested in such an educational institution.

The legal owners of the building that was meant to be a Jewish hospital were Dr. Yitzhak Geliebter and Ignacy Margolies. Geliebter immediately agreed and also gave a letter to Margolies. In any event, we received the permission to utilize the planned hospital building for a Gymnasium. We had to complete the building. There were only the walls and the roof.

We brought this project before the assembly, and also the permit of the Jewish balebatim that were the legal owners of the building. The job of finishing the building and making it suitable for use as a Gymnasium demanded a large sum of money. On the spot, an assessment was passed for a read sum (minimum 100 zlotys for each person) and everyone had to subscribe by a promissory note. The beginning was initiated with ardent zeal, and took off auspiciously.

We needed ready cash only for the working people. Materials were paid for with promissory notes, and most of the materials were obtained through gift/donations, for the Gymnasium. This is the way we obtained the tiles for the ovens from Dichter in the tile factory (Mendel Eisenstahl worked there as the director); the half doors and the dampers we got from Aharon Feder and Yitzhak Fink; stools we got from Tuvia Fuchs; bookcases in part were obtained from the Zegens, and from Yekel Pflug – everywhere without money. Other small items were donated by other balebatim from Zamość.

With the building completed, came the array of furnishing it with benches, blackboards, cabinets, teaching tools, maps, a variety of instruments, and tools, especially for the cabinets used for natural sciences, physics, chemistry, etc. To do this required someone with expertise, and this raised the question of a director.

I was delegated to go to Warsaw to locate a qualified candidate for a director.

At this time, Bytcheh Pfeffer and Moshe Epstein were co-opted into the board of directors.

From Warsaw, I came with the director, Borenstein. He presented himself to an assembly and was accepted. He declared that, if the required funds were placed at his disposal, it will be possible to open 4 grades for the coming new year. We committed ourselves to do this. Moshe Levin was engaged as a secretary, and two Christian assistants.

The director of the Polish Gymnasium, Lewitsky helped in obtaining the [sic: official] permission, and most importantly, the endorsement of Borenstein as the director. Lewitsky did this quite willingly, both because he was truly a fine man, and also because it got rid of the ‘Jewish Problem,’ for him in his Gymnasium.

The director brought the appropriate personnel from Warsaw. The commission of the school-curatorium certified the personnel, the building and the Gymnasium began to operate.

[Page 414]

Not all the students paid the required tuition fee, a part of the poorer ones paid half, and from others, nothing was taken. We were not sufficiently well acquainted with the issue of putting together a budget, and we quickly fell into a condition of great deficit.

I traveled to Lublin in order to learn about specific details of budgeting for our Gymnasium from the director of the Humanistic Jewish Gymnasium there. A townsman of ours, Yekel Geliebter, worked in the directorate of the Lublin Gymnasium. It was revealed that our teaching staff, with the director at its head, was being significantly overpaid. We wanted to align the pay in Zamość with that in Lublin. That was not so easy to do – it came to a strike by the teaching staff. In the end, there was a rationalization. The salaries were somewhat aligned, and reduced. The material situation then became a little better.

The Gymnasium developed; classes were added, until we had our own graduation. The first examinations were carried out by the director of the Polish Gymnasium, Lewitsky, indeed, in the Polish Gymnasium. The second ‘Matura’ was already administered by ourselves, without outside oversight.

The Gymnasium obtained equivalent standing to the Polish government one. It had a good name with the curatorium.

Suddenly, we were beset with trouble.

Communism was injected into the Humanistic Jewish Gymnasium in Lublin. As it happens, this was due to the children of the rich balebatim, and the way it was cut off was to expel them from the Gymnasium. So they came to Zamość, and brought it with them. This created a tumult, and there was a move to revoke the privileges of the Jewish Gymnasium.

After a great deal of intervention, the privileges were not revoked, but a demand was levied by the curatorium that a Christian would have to be engaged as the curator. It was necessary to comply with this demand.

The situation, however, became worse. The better off stopped sending their children to the Gymnasium – looking for other careers, or sending them to study out of the country. The professions where it was possible to gain entry into universities from the Gymnasium were Philosophy (in order to become a teacher), or law. For most of the parents, this was not something ‘worthwhile’ – they wanted medicine, pharmacy, or technology.

A crisis descended on the Gymnasium.

I came in with a proposal to transform the Gymnasium into a trade school. I demonstrated that in this way, we could get a subsidy from ORT. But at that time, Ignacy Margolies was already in the management, who supported the school, and did not permit any changes.

I then distanced myself from the activities of the Gymnasium.

Of the three founders, Shlomo Fein is in Afula, and Moshe Genzler is already deceased.

The Merchant's Society and Small Business Society

The mission of the Merchant's Society was an understandable one. Its activity was multi-branched. They would settle all matters relating to competition among the merchants; there was a court of peers for settling disputes; there was intervention in the tax department regarding taxes that were too high; lowering of taxes, or breaking it up into smaller rates [of payment]. It also had to carry out a cultural-social activity; a local office needed to be established, where it would be possible to come together after closing the businesses; they would have to travel on specific missions to the district seat (in Lublin) or to Warsaw about a variety of legal issues from the standpoint of the merchants.

[Page 415]

In the management were: Eliyahu Epstein (Chairman); Ben-Zion Lubliner (Vice-Chairman); Mordechai-Joseph Kronfeld, Chaim Brenner, Bytcheh Pfeffer, and me – Secretary Leibl Wechter. Meetings took place every Sunday, and later, every Tuesday.

We had enough difficulties in the work, and also internal organizational problems. It was hard for the Chairman to come to the Society. He was very strongly involved with his own many businesses – in tile making in brick making, or in warehousing. In addition to this, he had a custom that he would be out at 5AM to the market to buy a turkey or a goose – he personally had to make the purchase…. as a result, he would often doze off during meetings, or not have the focus when society issues were brought to him.

True – he would always give the stamp and his signature, often not knowing what it was about; not reading what was contained in the document that he had signed.

This was a defect in our organization – the presiding officer should have been the one to intervene – or there were instances when he did not do this, true, because he was so busy. – I left the leadership.

In the meantime, a small business Society was established. Indeed, this may have been because the small merchant didn't find an appropriate place in the Merchant's Society.

Shlomo-David Fershtendig and Itcheh Manzim (members of the leadership of the society) came to me, asking that I should come and work for them. At that time, the Secretary was Wolf Tuch.

First, I inquired at the Zionist Organization if I had to do this. From there the answer came – on the contrary, it is better for more inside people to take such positions.

So, in accordance with my habit, I applied myself to this work. First set up the local office. The previous local office was on the May 3 street, at Chaim Weintraub's, between his beds… we rented the new location from Bajczman, 2 rooms, renovated, installed furniture and in place of the previous secretary, engaged Hirsch Rosenberg's son, who had an application writing bureau, and his own writing machine [sic: typewriter]. Every day from 6 to nine, he sat in the office, and gave the members the required legal advice without charge, and prepared applications for a minimal cost. Every evening another member of the leadership had to be in the office to attend to the interests presented. If it was necessary to approach an official who was not at his post, then an appointment was set immediately for the next morning.

Later, the Secretary, Rosenberg, traveled to Warsaw to take a course at the central office of the small business society, to complete his understanding in legal matters, regarding statues and taxes and other administrative things to be arranged in the conduct of a small business.

In the course of a short time, the society grew and had 300 members. In that time, the director of the tax office was the Tatar Ashgray, notorious for taking the hide off people when it came to taxes. However, we ingratiated ourselves to him, and our interests received appropriate consideration.

Interventions, lowering or eliminating taxes, allowing them to be paid in instalments; confronting dishonest accusations; a variety of memorials regarding the conditions of the small businessman – the leadership did all of this. We also brought in the legal counsel of the small business society from Warsaw, the lawyer, Elkin, who, under the oversight of the previously mentioned tax official Ashgray, and the President of the finance office in Lublin, held a discourse on the issues about taxation. This had yet a further effect, and we did a great deal to loosen the screws of taxation from off of the impoverished mass of small businesses.

As a result of this work, the poorer and smaller merchants left the Merchant's Society, and joined the Small Business Society.

[Page 416]

Shlomo David Fershtendig and His Wine Cellar

Shlomo David Fershtendig, a son of Nehemiah Fershtendig, a grandson of Hirsch Fershtendig from Turobin, had a reputation that extended far beyond the boundaries of Zamość. It was a truly venerable wine firm, which was well-known throughout all of Poland, both among Jews and Christians.

Shlomo-David Fershtendig transferred his wine cellar from Turobin to Izbica, and later from Izbica to Zamość. According to the historical record of the firm, it was established in the year 1836!

His wine business was located in the house of Berish Luxembourg on Sztaszica 33. The business consisted of an underground wine cellar and open business up above. He serviced the entire area with the most expensive wines, and with a variety of beverages, domestic and imported. Wines for Kiddush and Havdalah, and Passover wines for the four cups. Paying no attention to the fact that he was a Jew, all of the priests, of all persuasions, would buy the wine at Fershtendig's for all of their sacramental rituals.

The cellar was configured with well-made articles for its purposes; it has something medieval about it, mixed with modern accommodations. All manner of barrels and bottles stood there, all covered with a molding… And in the middle… a gypsum figure of old Hirsch Fershtendig, Shlomo-David's grandfather… there were benches of black oak, tables of the same style, and contemporary lanterns, in which a dim electric light shone.

In a certain year, he asked Spiegelglass (the husband of the lady doctor, Dr. Rosenbush), an expert in these matters, who outfitted the cellar appropriately, and according to experts, transformed the cellar in accordance with the designs of the Altstadt in Warsaw.

Shlomo-David Fershtendig's wine cellar was visited by the greatest Polish personalities, who would travel through Zamość, or happen to find themselves in the vicinity. Nobility and military people; politicians or writers; natives and foreigners. They would drop into Zamość and come to Fershtendig's wine cellar, whose reputation was known throughout the entire land, and whose name literally reverberated around the world.

And these curious highly placed visitors wanted only Shlomo-David Fershtendig to attend them…he, in his long black coat, with his splayed out beard, with a yarmulka on his head, lent a further air of other-worldliness to the dim cellar…. in the cellar, there stood a machine on one of the massive oaken tables, where he fried up almonds with salt, which he served to his guests, pouring them glasses from the various vessels, depending on what kind of wine they wanted….

His guests related to him with respect, with a genuine deference to his expertise. There were certain foreigners, who were seeing such a ‘service’ and wine cellar for the very first time.

And he was a Jew with a big heart. A simple Jew, a member of ‘Agudat Israel’ ready to help everyone, whether individuals, or the community at large. His wine cellar indeed brought him to the ‘upper circles,’ and not only once did he serve as an ombudsman for an individual or for many. Not only once, at his own expense, did he travel to Lublin or even to Warsaw in order to mitigate a decree.

His hand and the drawer to his desk were open for help and charity. He would not ask for what or for whom – everyone who extended his hand, that individual has to receive something.

On the Sabbath, he would personally carry food to the Jews who were arrested, and in jail. The prison warden was a real anti-Semite, a certain Renkovic. But he got control of him. It cost him quite a few good bottles of wine…

He had one daughter. At the beginning, Asher Hechtkopf acted as a business manager in his business. When Asher got married, he brought his wife's sister's son from Tarnogrod with him – Berish.

[Page 417]

As a relative, Berish cramped him a bit – can it be, ignoring the business, too many community issues, and the like… but he didn't lose his way. With his skin and life, with his energy and money, served all who needed his help.

His end was the same as that of all our dear ones. He died the death of a martyr.

Berish and his daughter traveled to the Western Ukraine. He was arrested in Lemberg, and we do not know what happened. His daughter seemingly saved herself. After the war, she was seen in Lower Silesia.

The Jewish Gentleman from Ploskia – Ignacy Margolies

Certainly the Margolies family is mentioned in the Pinkas, and among the members of the last generation of this family, Ignacy, the ‘Pole of the Mosaic faith’……

A couple of details about him. I happened to have to business dealings with him, real commerce, as it were.

An incident once took place as follows: There was Jew in our midst who was a wagon driver, by the name of Itcheh'leh Krasnobroder. He was a pauper. His work consisted of conveying the residents of the summer homes, during the summer season, to Krasnobrod; After that, he would bring back mail; he would also transport products to Krasnobrod from Zamość, which those summer residents could not procure locally.

It happened that his horse collapsed. So he pleads with me to discuss with Ignacy, as to whether, as an act of charity, he would give him a charitable donation to purchase a horse.

I wanted to make a stronger case, and together with Pinia Becker (who had an influence with Ignacy) and Jekuthiel Bat, I approached him with the request.

What does he do? – He does not give charitable donations, he says, however, he gave a note to his administrator in Ploskia (this is the very same village that is identified in the work of Bart in our Pinkas, about the first colonization initiatives by Jews in the Zamość district. – Ed.), the Jew with the wide beard, that Itcheh'leh is to come and pick out a horse to his own liking.

He would direct the ‘Avigdoria’ – the Halutz training organization – to take straw and other products, and whatever else they needed.

Whatever he earned from his charitable notes he donated – half for the ‘Gemilut-Khesed,’ treasury and the second half – for the Jewish Gymnasium.

He was the first of the assimilated Jews, who gave 50 dollars for the ‘Keren HaYesod.’ However, he did not want to sign a declaration for ‘Keren HaYesod,’ – it was ‘against his principles’….

Translator's footnote:

Here, we again bring 2 documents which starkly mirror the difficult circumstances in which the poor Jews, in particular, found themselves, and in general, the residents of the Neustadt.

Both letters are from 1926. Both are appeals to landsleit in America.

Document One

With God's help, Wednesday of Parsha Yitro, 5686, Zamość, Neustadt, 3 February 1926.

With respect to the designated leaders, revered and beloved, whose names have gone out to all cities, May the Lord bless you and protect you in your coming and going – all of you, born in our city Zamość Neustadt, and living today in the country of ‘America’ ‘New York,’ ‘Detroit, Mich.’ ‘Brooklyn,’ and the like.

It is on you, the good and straight of heart. On you people, that I call. Listen to us, and the Lord will heed you, before all discourse grows, after his good wishes are invoked, with great love, and eternal love as is decreed.

Dear brethren, as is now known by each and every person, the current circumstances of Jews in Poland in general, this refers to the poverty that has spread to every individual, may the Lord spare us, the darkness that has covered the earth, and every cloud has emptied its storm of water on we Jews in Poland in general and on our city of Zamość, that is to say, the Neustadt in particular.

We have all come to be in the depths of this water, and all the waves pursue us, and our ship is at the edge of, God forbid, going under, may the Lord spare us.

You, our dear brethren with understanding hearts, must know that the current situation with us in Zamość Neustadt, that is, our ability to make a living is hard, somber and bitter. If you, our dear brethren recall, that a few years ago we approached you for support for our poor and sick brethren in Zamość, and you extended your hands and helped us to the extent that you could, we remember this very well. May the Blessed Lord also not forget you for this as well. But you must know, that this was not even a ‘drop in the ocean.’ It is true, that at that time, the situation was not an easy one, during the time of ‘the call to war.’ But then, it was a question of products. It was not so easy to obtain any products, but there was not ‘poverty’ of any sort (the goose feet belong to the writers everywhere) among Jews, meaning that many people had money. Regrettably, and to our great misfortune, the current situation throughout Poland in general, and here in the Neustadt in particular, the poverty had become so great, Lord preserve us, that the fire has surrounded us on all four sides, may the Lord save us, and no one knows who is being consumed, may the Lord save us, meaning – all the people about which we know nothing, and we think that he can sustain himself and be helpful to others, this type of person is now being forced to ask for help, may the Lord save us, is this not then a conflagration?

We must come to you and portray the circumstances of the Neustadt to you.

Up to about a half a year ago, the Jews in the Neustadt were living as usual – there were magnates, middle class people and poor people also. There were not, God forbid, beggars, but rather supported themselves ‘from hand to mouth,’ and craftsmen most certainly, without a doubt, had no need, God forbid, to ask for help from anyone.

[Page 419]

Now, in the last half year, the ‘sun’ has begun to set and the night has spread, and, Lord preserve us, it has become dark. We even thought that this nightfall was not going to last long, and in a short time the ‘sun’ will come out again, and the ‘light’ will return. However, our hope has not been realized up till now. And it has only gotten more difficult, and the longer we waited, the darkness became greater, and the Immortal God has poured out the entirety of his wrath on us, may the Lord preserve us. May the Blessed Lord show compassion to the Jews of Poland in general, and the Jews of the Neustadt in particular.

Dear and understanding brethren, you must know that we approach the writing of this letter, our hands are really trembling, and every limb in our bodies is good and broken. For, after all, how does one go about writing such tidings to ones' brethren – only by knowing very well for a long time, and we hear today, that you extend your hands and you take on providing all the means to help your brethren, whoever it is that stretches out his hands to you. Therefore, we to are compelled to approach you, and pour out our bitter hearts, as one brother tells another.

You should know, that here in the Neustadt, the situation concerning making a living has gotten very bad – and were we willing to portray each and every situation, all the pens and all the ink in the world would not be sufficient. We can only describe in summary form, and you should know that almost all of the merchants have gone under, may the Lord preserve us. Many stores are padlocked, because they have no licenses with which to operate. Many merchants, who dealt in forest products, require support for basic bread, may the Lord preserve us. Almost all of the craftsmen go about idle. All the wagon drivers – nothing to do. All the porters and so forth, go about as if it is a festival holiday in the street.

It is not possible to countenance the cry and alarm. One does not hear more than: ‘Bread,’ ‘Bread,’ and from the other side one hears, wood again. Again, one hears that a physician is needed, and ‘medicine,’ because there are many who are sick, may the Lord preserve us, who are ill because of ‘need’ and ‘cold,’ – ‘Woe to the ears that must hear this.’

It is nothing to describe the current condition by us, may the Lord save us.

Therefore, dear brethren, we have decided that we will appeal to you. From this, we may be able to heal and mitigate our pain. We know only too well that you share in our suffering, and that you feel our suffering quite realistically – despite the fact that the bodies are far from one another, the ‘hearts’ are very near, and are bound to one another with a secure knot, which will never be sundered. And the most powerful waters will be unable to extinguish the love that we have for you, and you for us, that exists for so long. We can say this to you without seeming to ‘flatter,’ because we know and we hear about what you do with each individual person, and especially with us, your own brethren, meaning the ‘paupers of your city.’

Please do not think that we have not already undertaken the most draconian measures to enable us to help our impoverished brethren ourselves. We have gathered with a single heart, and like one person, and we have created a ‘Linat HaTzedek’ for the ill, who are to be supported with physicians, and with medicines, with milk, and so forth. We have also created a ‘Charity Box,’ for supporting poor people with bread and wood, and so forth. We have also strengthened the ‘Talmud Torah’ with great pedagogues, with teachers, and so forth. We are doing very much to the limit of our capacity, but it doesn't help, because while we strengthen ourselves to provide vigorous help, the ‘poverty’ becomes more intense, may God save us. Every day, individuals come to ask for help who up till this time was in a position to help others. Now, they have a need to take.

We cannot write this down, because if your were to know who it was that needed such support, you would be incredulous, because, as we have previously mentioned, this [situation] is like a conflagration, mat God save us – here the fire is on one side, and a minute later, it appears on another side. In particular, at this time – ‘Passover’ is coming, for which we need 10 thousand zlotys, and all at once, and who is to know ‘how the burden of gathering this sum will weigh on us’ – and how will we take counsel, may the Blessed Lord take pity on us.

Therefore, dear brethren, awaken your hearts, and all of you gather, small and large, we mean every single man of you, without exception, all of you together, form a single bloc, and see to it that every single person should not be overlooked

[Page 420]

in giving a donation, each man in accordance with the means with which the Lord has blessed him. And you shall say, let us help our brethren, and let us hear their cry, and send us the money that you will collect immediately – indeed ‘by telegraph’ to the bank's name, ‘HIAS,’ in order that it be able to arrive in time. You can also send to the Rabbi of this place, R' Mordechai Sternfeld, or to Moshe Eliezer Friedling's address, or to any of the names of the undersigned. It will immediately be distributed in the best order. And in consideration for this charity, may you be helped in general and in specific areas, and may you be saved from all manner of ill and tribulation, and you will be thrice recompensed – with your children, and livelihood.

We have come here today to affix our signatures on Wednesday of Parshat Yitro 5686 in Zamość, Neustadt.

These are all the leaders of the commission:

Moshe Reisenfeld

Moshe Eliezer Friedling

Zvi Zwerin (a Polish stamp to the side)

Moshe Freiss

Israel Zucker

Elimelech Schwartz Berg

Jonah Worim

Joseph Kalechstein

Boruch Shuv (A shokhet)

Mattus Mittelman – I support this letter certifying that the help is very necessary.

(The last addendum appears to have been added because the referenced Mittelman had his relatives among the activists in the American Relief-Committee, and his ‘endorsement’ was supposed to have added weight to the appeal – Ed.).

Document Two

To the Zamość Relief-Committee in New York.

Comrades and Friends:

It is not the objective of the progressive proletarian social segment (of our city) to support philanthropic institutions such as the ‘Linat HaTzedek’ in Zamość.

However, here in Zamość, the position of this institution is quite different! According to our perception, and also the elected representatives on the scene in Zamość, Moshe Freilich, and Yaakov Meir Topf, relative to the current crisis situation, it appears as follows:

Only those workers who are employed may benefit from the sick-funds in Zamość, and receive medical help. However, in the time of crisis, when there is no work, the sick-fund cannot be used. If one of the workers, that is unemployed, becomes sick himself, or a member of his family [becomes sick], his first source of medical assistance is the Linat HaTzedek.

We must also reckon with the local manual laborers, who have become impoverished. Were it not for this non-partisan institution, the poor masses of Zamość would suffer a large number of deaths.

The objective of the Linat HaTzedek is that anyone from the Altstadt in Zamość comes for medical help, he is given what is needed until he gets well. In the exceptional circumstances, when it happens that a more senior physician is needed from the outside, it is attended to at the account of the Linat Tzedek. The same also holds if someone must travel with the sick person to obtain a cure – with no distinction made regarding the individual, everyone receives support.

[Page 421]

Despite the fact that we, the undersigned, count ourselves among the progressive socialist segment of the populace, whose objective is not to support any philanthropic institutions, nevertheless, in seeing the frightful circumstances in the Polish Republic in general,. And of the Jewish folk masses in particular, and especially the sick, and taking cognizance of the mostly non-partisan work that the Altstadt Zamość Linat Tzedek conducts, we are in favor of the need to provide support to this institution that supports the needy, in today's moment.

And we request of you as Comrades and Friends, not to evaluate this referenced institution casually, but rather to provide whatever support is possible for you to provide.

We again attest – the Jewish masses of Zamość would pay dearly if this institution did not exist in our midst.

Let us also add that if an institution exists in our midst that does not make any ideological differentiation in performing its activities, but rather, every sick Jewish person in Zamość is provisioned through this institution with medical help, and hundreds of people every year are rescued from danger – literally brought back to life from the brink of death, this is the institution that does it.

If there are funds with you, our comrades and friends, to support a variety of Zamość social institutions, you must place the Altstadt Zamość Linat Tzedek in the row of the first priority, and help us in this work, which saves, that makes the sick healthy again, and brings the dead back to life.

Moshe Freilich – Yaakov Meir Topf

These documents do not demand any commentary. They are documents of the time and they set out an accurate reflection of the condition of the Jewish folk masses that were impoverished by the [economic] crisis.

It is to be understood, that the recommendation of the two, who were from the ‘progressive-socialists’ camp was required, in order to obtain the allegiance to what was going on in the ‘old country.’ Especially since the activists in the American Relief were activists in the socialist, and especially the Bundist movement in Zamość.

by Helena Schaffner

Jewish Zamość no longer exists. It is therefore painful for me to recall my home town. I make an effort to distance myself from the images of old Zamość; even that unique Zamość humor no longer elicits a smile from me, but more readily a grimace of unhappiness.

Fate would have it, that I would meet with a landsfrau in New York, who had left Zamość years ago, and who had hidden away a vision of our home town in its complete freshness. I did not have the heart to disappoint her by portraying to her the picture of post-war Zamość. I therefore exerted myself, in talking to her, to bring out in my memory, only my memory of pre-war Zamość – the Zamość in which each and every resident took so much pride.

The beautiful municipal building in the style of the Italian Renaissance, that was located in the center of the city, with four green squares in front; the houses with their proportional forms, supported from beneath by ‘potchinehs,’ the modest building with its harmonious lines; the academy, the Zamoyski Palace, built in the design of the Vatican; the highly elevated bell-tower; the walls that encircled the city, giving Zamość a romantic beauty and finally – the fields outside the city, and the valleys, that spread themselves far and wide, as far as the eye can see. It is no wonder that the residents of Zamość (Jews comprised the largest majority of the population) were enthusiasts on behalf of the city, spoke with inspiration about its beauty, and called it ‘Little Paris.’

Zamość did not only stand out from the other cities of the Lublin district with its external esthetic appearance, but also with its inner spiritual countenance, Zamość was the cultural center of the entire surroundings.

The residents of Zamość felt a special responsibility already, because of the fact that I. L. Peretz was born, and also was creative in their city. The entire Jewish population of Zamość felt that it was a partner to Yiddish literature. The library named for Peretz contained a treasure of Yiddish and Polish books, which continuously passed from hand to hand. In the long winter nights, the lit windows of the Peretz library, which shone out onto the plaza of the Rathaus, gave testimony that Zamość was not asleep, that it is thinking, is flying and striving. In the summertime, the large balcony of the library was full of young people, who would heatedly discuss and contended over a variety of literary and social problems.

The Yiddish culture and literature were the companion platforms on which all walks of life met: the elements of the middle class, the manual laborers, workers, and student youth. All the political persuasions had their adherents in Zamość: Zionists, S.S., Poalei-Tzion, Left wingers, P. P. S. But the party that was mentioned in the streets of Zamość was the Bund. It united all of the pan-human ideals with efforts for a unique Yiddish culture, which appealed best of all to the Jewish youth of Zamość.

The first revolutionary activity in 1905 engaged a group of Jewish intellectuals in Zamość, under the banner of the Bund. The following belonged to this small leadership group: Naphtali Margolies, who was killed by the Germans in Izbica, during the last war; Yerakhmiel Brandwein, who was also killed at the hands of the German murderers in Vladimir Wolynsk; Fishl Geliebter, who, before the last world war, died in New York. Where he was the photography director of the Arbeiter Ring. Many of them live in a variety of countries of the world. This first group sowed its seeds deeply on the social field in Zamość, so much so, that up to the last minute, the Bund remained the most active dominant party in the city. Up to the outbreak of the Second World War, the Bund had its representatives in the City Council, who with their dedicated work and moral authority exerted a strong influence on the activity of the municipal leadership.

I remind myself of a small but characteristic episode, which took place shortly before the outbreak of the war:

[Page 423]

The Polish leadership could under no circumstances get used to the thought, that the leaders of the Jewish workers have the ‘chutzpah’ to offer an opinion about how municipal affairs should be conducted. Therefore, it used all means to exert itself to compromise the Bundist member of the Magistrate (Lavnik), Yerakhmiel Brandwein, accusing him, as it were, of manipulation of funds. He was arrested, and brought to trial. A council member from the Endekists, incidentally a decent fellow, attended a meeting of the city council, in order to defend the Bundist Lavnik. We have to admit, he said, that if Brandwein were not decent, he would not have taken on the entire city council, and would not have fought so tenaciously. This argument rang a responsive chord in everyone's ears, and was persuasive. Quickly, the libel was revealed, and the court sentenced Brandwein's accusers, a group of reactionary anti-Semitic plotters.

One trait of the people of Zamość was recognized throughout all of Poland, because the guests who would come there for debates and meetings noticed it most of all, took not of it, and remarked about it everywhere they spoke – this trait was: enthusiasm. Not only among the young people, but also among the older generation, one could find enthusiasm at every turn, dreamers of dreams.

I recollect the celebration in Zamość in honor of the tenth anniversary of the University of Jerusalem. Among the speeches, one could hear tones that were characteristic of Jews in general, and especially of Zamość Jews. The speakers underscored that the University of Jerusalem has to be an outpost for human unity, a center for the Jewish spiritual struggle against all of the mean forces of the world. Just as the Jewish prophets were the carriers of pan-human ideals, so must educated Jews be the ones to spread the new general humanistic ideas.

Zamość had ambitions, which were traditional-Jewish and at the same time, pan-human.

The extent to which the Jews of Zamość felt themselves connected to all of the great problems of the world, could be seen in the feverish interest in the Spanish Civil War in the year 1936. They correctly assessed that the Spanish tragedy was merely a prelude to a world tragedy, from which the Jews will be the ones to suffer the most. The Warsaw newspapers were literally gobbled up, as soon as they arrived in the city; every bit of news was discussed in an intense fashion. My father, at that time, was seriously ill. The house was full of people (in Zamość, Bikkur Kholim was thought of very highly), everyone was talking about Spain, and my father also took an active part in the discussions. Somehow, he forgot his intense physical suffering, which did not let up for even a minute. This was first indicated by the doctor (Fishl Geliebter's nephew by his sister), the discussions brought him back to functioning….

It was in this manner that the Jews of Zamość would take up general questions, and in this way they were able to live the same lives as other people. The epitomized the trait, characterized their landsman I. L. Peretz – being a part of the human race, but never ceasing to be a Jew.

by Kalman Engelstein

|

|

The first founder of the reformed Heder in Zamość was Zvi Handelsman, ז”ל.

Mr. Handelsman, the Maskil, enlightened and good-hearted, was the one who made the dissemination of knowledge to the young Jewish generation his life's ideal.

In the year 1903, after the 6th Zionist Congress, which became known for the ‘Uganda’-crisis, the new kind of Yiddish educational institution began to be created – the ‘reformed Heder.’ Handelsman decides to establish such a Heder in Zamość. But how to do this, what sort of a thing is this, how does it get organized?

He travels to Berdichev, where such a ‘reformed Heder’ was already in existence. He stays there with the City's Chief Rabbi, Yaakov Berman. He permits himself to stay there for a space of time, and observes the ways of the new type of institution.

Upon his return, he and his friends: Jonah-Yehoshua Peretz, Chaim Brenner, Zusha Falk, Yaakov Wolfenfeld, Mordechai Brenner, Elyeh Weinrib, and others, take it upon themselves to implement this concept – founding a ‘reformed Heder.’

The first concern was about teachers. Mr. Handelsman learns about a teacher, Sholom Weiner, who lives in Hrubieszow, and wants to work in such an institution. He brings him to Zamość, and has him stay with him for a period of time. He wants to get to know him better, see his deportment, his skills, his nature and his knowledge. Hirsch Handelsman used to say: ‘I must know the wellspring from which the younger generation will imbibe its sustenance very well….’

Sholom Weiner satisfied him, and with a few children, the ‘reformed Heder’ was opened under the name, ‘Kadima.’

An uproar began from the very observant circles – that the Heder ‘Kadima’ is being led by apostates, and the matter went so far, that it reached the Belzer Rebbe. The Rebbe summoned Handelsman to him. He traveled to the Belzer [Rebbe] together with Chaim Brenner. There, the Rebbe spoke with them for a couple of hours. When they returned, the ‘reformed Heder’ again resumed activity.

After this, a new teacher was hired, Anshin, who taught the Russian language.

‘Kadima’ was directed with the best order up to the outbreak of the First World War, 1914. Hirsch Handelsman, an owner of a cut goods store, literally did not miss a single day in visiting the school, especially during examination time.

He was forced to leave Zamość, and went off to Russia. He suffered a great deal, until he died at the age of 57 years, in the year 1921 in Berdichev.

‘Kadima’ was re-established after the end of the First World War. Chaim-Hirsch Geliebter joined as a teacher, who came from the Land of Israel. He began to teach in accordance of the system Ivrit-Be'Ivrit. (Also for girls).

‘Kadima’ was the first school in Poland of its type – a reformed Heder of boys and girls together.

Sholom Weiner also taught Talmud with Rashi and Tosafot commentary in the higher grades. The school had a choir of 30 children.

[Page 425]

The institution was beloved by the city, especially by those segments who wanted to give their children a modern upbringing, that is based on our ancient spiritual treasures.

I remember very well how I. L. Peretz visited the school. Just at that time, we were studying the capture of Jericho. When the recess bell was rung, Peretz remarks to the children – dear children – show me how they captured Jericho. The children went out into the street, and improvised the entire story. They divided among themselves the roles of Joshua Bin Nun, with Priests, Levites, and even a girl, who was made up to be Rahab, who was then ‘saved’ from the captured ‘Jericho,’ which was a gain bin in the yard of the school…

The school grew from year to year, and reached to 7 grades.

Together with our entire community, ‘Kadima’ also came to an end.

By Baruch Sobol

The Dispute between Hasidim and Mitnagdim

Zamość already had a tradition of Haskala, of Enlightenment. Never mind that the city took pride in a large number of great Torah sages, and even the Kabbala, the Hasidic movement was discriminated against there – literally having no welcome entry, and most of all in the stronghold of the balebatim, the scholarly Altstadt.

Zamość was practically the only openly expressed city of Mitnagdim in all of Poland – but especially, it was a sort of ‘anti-Hasidic’ island in the Lublin district, where all the towns and villages were Hasidic, and where one need to search for a Mitnaged with a candle.

Neustadt was an exception – there, among the simple people, the masses, uneducated Jews, Hasidim were found. Yet, these too, were largely those who came in from the surrounding towns.

In the large Bet HaMedrash, called the ‘Loymdisher,’[1] And also in all the small places of worship around the Great Synagogue, the style of prayer was Ashkenazic, God forbid that anyone should dilute the prayers with the Hasidic style of Sephard….

If Hasidim came to pray in the Great Synagogue, then they knew that they must abide by the Ashkenazic ritual. Every change, every attempt to smuggle in something from the Sephardic ritual, was met with a threat of being ejected from the holy place. Even being thrown off the Amud in the middle of the Shemona Esrei.

Up until the First World War, not a single Hasidic Rebbe thought to come to Zamość on a visit to his followers. There was an array of Hasidic shtiblach: Gerrer, Kotzker, Radziner, Trisker, Belzer, Cuzmirer, and the like. The Hasidim would visit their Rebbes when those Rebbes would visit cities in the neighborhood – in Izbica, Turobin, Szczebrzeszyn, Tomaszow and others.

If a Rebbe would slip in, he would stay in the Neustadt.

Ignoring this contention, however, peace and tranquility reigned between the Hasidim and Mitnagdim. Each conducted himself in accordance with his own ritual and way – and it never came to an open dispute. There already was an ideal tradition in Zamość – dating back to the first days of the division between Hasidim and Mitnagdim, which was reflected between Vilna and Karlin. Here, one did not openly interfere with the other. Here, it is necessary to say, that the Hasidim had to put up with great tribulation, because they endured a great deal – their customs, their Rebbes, were not permitted entry into their city. But they did everything they could to prevent the fire of divisiveness from spreading about.

Both Hasidim and Mitnagdim would meet in general community institutions, foremost in the philanthropic ones, and the ones that offered mutual aid.

A greater controversy arose in 1870-1889, which became famous beyond the borders of Zamość. It was a dispute between the Hasidim and the Enlightened people, who mostly came out of the ranks of the Mitnagdim. I. L. Peretz was involved in this controversy.

The role of the Haskala movement in Zamość is known. After communication started to arrive from the outside world about the springtime of the free spirit, groups of enlightened people began to form, early adopters, who began to teach,

[Page 427]

simple, elementary education to the poor, deprived sectors of the Jewish surroundings. – From simple Hebrew the transition was made to Tanakh, Hebrew and Yiddish history.

I. L. Peretz took a very active part in this Enlightenment activity.

He began by learning chapters of the Tanakh together with simple craftsmen or their workers. Every Sabbath Peretz gave lectures to Jews who toiled at hard work for an entire week.

The education committee, however, observed that apart from these attempts to enlighten the older people, that it was necessary to create modern educational institutions – that modern Heders need to be created, where apart from Hebrew and prayers being taught, also Tanakh, Hebrew, Yiddish History, and this accomplished through educated teachers who were pedagogically trained.

It was here that the dispute arose. If it was necessary to translate a portion of the Pentateuch for older people, or a chapter of the Tanakh, that was not considered ‘risky.’ The ‘danger’ that threatened was that young people would be led ‘astray’ from the [proper] path.

This struggle was not initiated by the locally born Hasidim, but rather sons-in-law, who had moved in from elsewhere. They began to incite their in-laws, that Peretz and his crowd were leading the children away from the Jewish way of life, and indeed, also the older people. Fear of conversion, God forbid, became prevalent; it was even rumored that a portion of Peretz's students have already become missionaries… and, please understand, the plagues and severe decrees that would fall on the city were already in sight.

A true martyr's battle ensued – the fire of this controversy spread about.

Gatherings took place in the Hasidic shtiblach, and a decision was taken, that nothing would be done until Rosh Hashana – only at Rosh Hashana time would they show the apostates…. whatever will be shown, was kept secret.

The plan for the Hasidic action manifested itself later, indeed on Rosh Hashana. On that day, all the Hasidic shtiblach remained locked. All the Hasidim came to pray at the Great Synagogue, where the Mitnagdim prayed, and, you understand of course, the ‘apostates’ with I. L. Peretz at their head.

When the Hazzan of the Mitnagdim stood up to the Amud, and began to intone the prayers, a young Hasidic man grew up next to him, in a satin kapote (this by itself was a provocation – a satin kapote!….), with a wide gartel (literally a sacrilege!), and began to pray out loud in the Sephardic style.

The Hazzan begins to intone the first prayer, ‘Mizmor Shir Hanukkat HaBayit LeDavid,’ in the Ashkenazic style. So the young Hasidic fellow shouts out in a louder voice, ‘Hodu LaShem…’ as is the case in the Hasidic Sephardic style.

And this is the way the Kedusha was repeated, and also the Kaddish – the Hazzan is davening according to the Ashkenazic ritual, and the Hasidim butt in with their Sephardic ritual…

A scandal of this magnitude, a sacrilege of this sort could not be hushed up, and the conflagration spread – it bestirred the normally quiet Mitnagdim to abandon their sense of parity; but the Hasidim demanded – that so long as an end is not made to the modern Heders, they will come and pray in the Great Synagogue using the Sephardic ritual….

This first movement by the Hasidim was played by the young men being supported by in-laws while they studied, who came from the outside. The older local Hasidim however, have an array of issues that allied them with the Mitnagdim – first was actually the business angle. They did not have the passion of the young people, and they undertook an initiative to bring an end to this conflict.

[Page 428]

A part of the residents traveled to their Rebbes and explained to them, that there was a real danger if this conflict were to persist, because the Mitnagdim were close to the authorities of the regime, and so a whole slew of trouble can begin with informing, and this can get out of hand.

As it happened, Peretz chose to leave Zamość and move to Warsaw, and the principal reason for the controversy practically was gotten out of the way…

What ensued, is that the old-style Heder remained, but the intelligentsia will establish a modern Heder. Once again, the Rebbes instructed their followers, that from each Hasidic shtibl, two young Hasidic men were to be sent to pray in the Great Synagogue, and that this should be a talisman to assure that they should not stray from the straight and narrow there. The end was, that the young Hasidic people barely paid attention to the danger from the Mitnagdim, since they themselves ‘fell into the trap’….

In any event, the fire from that controversy was extinguished.

White-Blue Charity Boxes and Rabbi Meir Baal-HaNess Boxes

Having gotten rid of one controversy, it was ordained that a new outbreak of hostility would occur. This time over charity boxes….

In 1896, immediately after Herzl's concept of political Zionism arose, a circle was created in Zamość among the youth in the Bet HaMedrash, which began to propagandize the Zionist concept. The older Hovevei-Tzion drew the youth in, and twice a week, debates would take place about issues from the Land of Israel and Zionism.

In 1902, a letter came to Zamość from the ‘Odessa Committee’ whose head was Menachem Mendel Ussishkin[2], in which the Zionist youth of Zamość is tasked to fulfill the challenge that Dr. Herman Shapiro had laid down at the 2nd Zionist Congress – a Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael shall be created. The first task was to distribute the Keren Kayemet ‘pushka’ to each Jewish home.

We handled the question at a special assembly of the youth. We knew the difficulties in such work, and since it was worthwhile to see how this would appear, the lot fell to me and my Bet HaMedrash comrade David Zederbaum ז”ל, that we will be the first to visit houses and see what sort of reaction this will elicit. We knew what to say – with this money, we will buy back our Holy Land from the Arabs, settle Jews there, and so forth.

However, it was very difficult to carry this out. In the more observant, Hasidic houses especially, we were received not only coldly, but indeed in a contentious manner. As it happened, we had to endure a great deal of insults from fanatic elements, who saw in the white-blue box a sacrilege and diminution of contribution to the Rabbi Meir Baal-HaNess ‘pushka’……

It is important to know that the Rabbi Meir Baal Ha-Ness box was one of the most important requisites of piety in the Jewish home, especially in the province of the Jewish housewife – not only before blessing the candles; not only before going to bed; not only on Festivals – always, the Baal HaNess ‘pushka’ was the way to succor, to healing – in the event of misfortune, in the event of illness – always, one would throw a few groschen into it for charity. And here come these

[Page 429]

young people, who are far removed from piety, and are talking something about the Land of Israel….this was looked upon with suspicion, with fear, and indeed with hostility….

The same thing happened on Yom Kippur Eve, when among all of the ‘plates’ an attempt was made to place a plate for the Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael. In the Great Synagogue, in the Bet HaMedrash, in surrounding small synagogues, where there were Mitnagdim, it was not difficult. It was different in the shtiblach of the Hasidim, in those locations, there was not even a discussion.

Indeed, these were controversies – but controversies having to do with matters of heaven, a fight over what was better, what was more appropriate way to serve the people, what sort of way should it choose. The Great Destruction brought an end to all ‘controversies’ – observant and the freethinking were eradicated; the Hasidim and the Mitnagdim ; those who threw they money in the Baal HaNess pushka or the Keren Kayemet pushka. Mercilessly, they were all thrown into the cruel chasm that the Amalek of our generation had prepared for them – the Nazis, may their name and memory be erased.

Translator's footnotes:

By Lejzor Finkman

|

|

|

|

From right to left, above: David Auerbach, Moshe Zimmerman, Moshe Mittelpunkt, Chaya Auerbach, Mikhl Feinbaum, Shoymeh Fang; Sitting: Peretz Greenbaum, Falek Goldhaar, Reizl Spodek, Moshe'leh Glanz, Taibeh Khakhak, Yudel Safian, Pinchas Sorkeleh Hazzan's[1] |

The revolutionary battles of the ‘fifth’ year have long been forgotten; there are almost no traces left of the outbreaks of the Revolution of 1905, which took hold of all Russia and did not spare the Zamość Region, our city foremost of all.

Part of the participants in the movement were disappointed; others were devastated by the failed revolution; many moved to the sidelines because of the powerful terror of the Czarist authorities. Part of the activists were exiled, were incarcerated in prisons. Others went to foreign cities, or fled out of the country.

Superficially, everything seemed to have ‘quieted down,’ – the storekeeper sits in his store, and waits for a buyer; market fair days come as is normal; in the factories they have returned to the ‘good’ times – people worked 14 and 16 hours a day.

However, quietly, the tunes of the recently sung songs were hummed… stanzas of the Bundist ‘Oath,’ were murmured:

‘Brider un Shvester fun Arbeit un Neut…’

Also, Abraham Reisen's [song] was sung:

‘Hulyet, Hulyet Bayzeh Vinten…’

And one dreamed of a better tomorrow.

Those who had the means, emigrated to America, with the hope of being able to ease the want back at home. Jewish houses were emptied, especially among the families of workers and craftsmen.

No community life existed at all by now, not to mention a union movement. A pall fell over everything. The one ‘outlet’ was to meet in the foyer of the synagogue on the Sabbath; there, it was possible to talk through the situation. There, the workers would longingly recall the times, not too long ago, which had passed.

It was not possible to organize a community movement – the required intellectual expertise was not available; also, the Czarist reign of terror was still in force.

In that time – I am speaking of 1912-1913 – there was a library under the name ‘General Community Library and Reading Room.’ The balebatim who oversaw this institution were from the petit bourgeoisie of Zamość, who were from the truly enlightened segment. The working masses did not patronize this facility for two reasons: first because of the long working day, and second – the unfamiliar location.

[Page 431]

This tranquility persisted until the outbreak of the war in the year 1914.

The outbreak of the war struck the poor populace in particular. Because of the general mobilization, work and commerce came to an immediate halt. It was not possible to travel to foreign places to seek work. A few worked at free-lance work. Most wandered about without work.

A month after the outbreak of the war, Zamość was occupied by the Austrian Army. After a ten-day occupation, they abandoned the city, and the Russians returned. A shameful incitement takes place, which ends in a bloodbath. (This is described separately in our Pinkas).

Zamość is occupied by the Germans in the summer of 1915. The heavy yoke of the German occupation is felt immediately. Food and clothing are confiscated. The occupation authorities does not permit any assemblies – more than 3 people together is considered an ‘assembly.’

Several months later, Zamość passes again into the hands of the Austrians, and things ease up a little. Trade begins to function – true, instead of traveling for merchandise to Warsaw or Lodz, the merchants travel to Krakow, Lemberg, and other cities of the former Austria[-Hungary].

Work began for the military; other work also was created; life began to normalize.

In that time, the desire to do something on a community basis was awakened among a segment of the work force that had been previously active in the 1905 movement.

At the initiative of the friends, Yaakov-Meir Topf, Getzel Schwartzberg, and Lejzor Jonasgartel, a conference was called for in the winter of 1916 of workers in a variety of trades, to which 15 men came. I recall a number of them. They are: Yaakov-Meir Topf, Getzel Schwartzberg, Lejzor Jonasgartel, Pinchas Topf, Itcheh-Leib Herring, Lejzor Finkman, Yankel Pearl, Aharon Rochman, Lejzor Deitchgewand, etc.

The conference took place in the bakery of Gedaliah Jonasgartel. After an interval of clarifying the purpose, it was decided to found a ‘Workers' Home,’ where all of the workers of the city and the Neustadt would come together.

The proposal of Yaakov-Meir Topf, to confer with Yerakhmiel Brandwein, a prominent activist from the Bund in the ‘fifth’ year, who had just returned from exile in Siberia.

Because of his weakened health, Yerakhmiel Brandwein was not able to engage in this organizing effort of the workers, and he sent the delegation to Itzik Goldstein and Mikh'cheh Levin – also from among the active workers in the revolutionary period of 1905.

After a number of conferences with the two committed comrades, and with the support of Salek Levin, the first ‘Workers' Home’ was indeed established, which arranged its facilities in comfortable quarters in the Hotel ‘Victoria.’

The workers would come together and discuss various questions and also deal with their economic circumstances.

After 15 days of the existence of the ‘Workers' Home,’ on a Friday night, when there was a large number of workers assembled at the ‘Workers' Home,’ – during a lecture by Itzik Goldstein – 2 policemen and a sergeant arrived, and declared that the ‘Workers' Home’ was closed down, and they closed down the location….once again, we found ourselves out on the street.

Having already attempted to talk together, meet together, the workers began to look after having their meetings in secret. In this regard, the bakery of Yudel Becker was very useful, and the old cemetery.

Real-world questions were dealt with at these meetings. They were led by Itzik Goldstein and Mikhcheh Levin.

[Page 432]

After strenuous efforts, in approaching the authorities, permission was given to again open the ‘Workers' Home’ in a second building.

Our comrade 'Luzer Nirenstein has to be recalled here, a dental technician, who permitted a location for the ‘Workers' Home’ to be arranged in his home. Jewish workers without distinction as to party, would meet there – Bundists, members of Poalei Tzion.

The first General Professional Workers' Society in Zamość was founded in the ‘Workers' Home,’ which was governed by a professional council. There were separate sections for each trade. Which passed a series of salary actions, and the first strike for a 10 hour workday. Until that time, one worked 14-16 hours a day.

In the ‘Workers' Home’ the first culture commission was founded, which encouraged the workers to become members of the municipal library, and also arranged for literary evenings.

It was also the time that the Bundist activities were officially renewed. The local Bundist organization is established under the direction of Mikh'cheh Levin and Itzik Goldstein. A press committee is created, which involved itself in the distribution of the Bundist newspaper, ‘Leben's-Fragen,’ and other brochures. In this work, the member Lejzor Deitchgewand especially distinguished himself.

That is the way it went on until 1918.

Elections arrive for the library, and a number of Bundists are chosen for the leadership, from the professional council. Indeed, it is at that meeting, that it is decided to name the library after I. L. Peretz.[2]

The leadership of the library then consists of the members: Mikh'cheh Levin, Itzik Goldstein, Salek Levin, Lejzor Finkman, Yaakov-Meir Topf and Yerakhmiel Brandwein is appointed as an Honorary Chairman.

It is not only with the number of its books – about 5,000 – that the library was the largest in the area. We had 800 members in the library. Among them were also a number (not a large number) of Poles, because we had the newest publications also from the Polish literature.

The library, together with the professional council, would invite speakers from Warsaw; organize open readings on political and literary themes. In this respect, the library was the only one [to do this] in the city.

In the life of the library itself; discussions would take place in the unions; the first sympathies for communism began to appear. These members, organized themselves as a break-off group, and fought for recognition. Up to that time, which was before the establishment of the ‘Combund,’ all of the unions found themselves under the almost exclusive influence of the Bund.

This time falls precisely in the same time of the consolidation of the professional movement, of fighting out for the recognition of the unions by the balebatim, for better working conditions and higher wages.

One of the resulting actions, about which it is worth pausing, was the strike of the housemaids. Up to that time, they had to work from ‘full day’ to ‘full day.’ Their ‘free’ time consisted of one Sabbath afternoon. Thanks to the strike that took place, they got the right to leave work every evening, and a fixed monthly wage.

At the end of 1918, when the first Polish regime was created under the leadership of Maraczewski (P. P. S.), an array of social reforms were instituted, and the eight-hour workday was decreed.

[Page 433]

The professional council designated a meeting in the municipal Bet HaMedrash, where the eight-hour working day was proclaimed to Zamość, for all the trades.

In those days, the first elections were held for the Zamość city council. A unified bloc of the Bund and the professional council ran in the election. This ballot sent 4 councilmen to the city council.

At the same time, the Bundist Youth Organization, ‘Zukunft’ was founded, which did a great deal for the development of the youth, and drew the young people into the interests that the working people were struggling for. They distributed the periodical of the ‘Zukunft,’ and an array of other offerings by the youth, and brochures. The active members of ‘Zukunft’ in those years included: Israel Garfinkel, David Levinson, Chaya'leh Grei, Yehudit Schatz, Simcha Arbesfeld, Leibel Cooperman, and others.

Many initiatives came out of the Bund organization relative to cultural activities: lectures, concerts, presentations, literary impressions. The income was used to support the institutions. Also the initiative to create a Drama Circle was made at that time.

My recollections end with the year 1923. I then left Zamość.

Translator's footnotes:

By Mottel Steiner (Montreal – Canada)

|

|

This was the time of the First World War – 1915 or 1916.

Zamość was occupied by the Austrian military. As all over, under the German-Austrian occupation, a great famine reigned. Everything was distributed by ration cards. We lived exclusively on potatoes.

It seems to me, that the song: ‘Sontag bulbehs, Montag bulbehs, Dienstag, Mittwoch, bulbehs,’ had its birth at that time. And even the potatoes were not plentiful. People ate the potato peels, raw beets, and a variety of ersatz flours. Cleanliness was not observed, because their was not enough soap. In addition, there were all of the dead, who were not buried in a timely fashion. Many human parts would litter the fields, and nobody paid attention to this.

Many cities and towns had an outbreak of epidemics – it was called the cholera. The epidemic cut down many lives, young and old alike.

I remember how, one time, in the middle of the night, my grandfather knocked on our door, and in one breath, shouted out:

– Come in! Come In! Faster! Your mother (meaning my grandmother, my mother's mother) has passed out….

My parents quickly got up from their beds, grabbed something to put on, and quickly went out to my grandfather's house. In, a child of eight years, dressed myself, and when In entered my grandfather's house, In saw my grandmother was in bed, not speaking, not sighing. M y father rubbed whiskey on her hands, and the feet. My grandfather sat, and recited Psalms, and wept. Several hours later, that means before dawn, my Bubbeh Faygeh died.

A day later, my 7 year-old sister also died, who was wept for vehemently by my mother and father.

In our area, in the Neustadt, they began to say that there is no choice but to arrange a wedding to take place in the cemetery. Older people already indicated with evidence, that here and there, there were such epidemics many years ago, and only the performance of a wedding ceremony at the cemetery caused it to stop.

Women took themselves energetically to the task. An appropriate couple was sought for, that would agree to such a wedding, and a variety of names were mentioned, all of the poor innocents were counted out, until they found….

In the Cuzmirer shtibl there was a deaf Shammes, and nobody knew where he came from; where he was born; how old he was. One thing was known: why he was deaf. He would indicate, by using his hands, that when he was little, he had fallen off a roof.

He was of medium height, with a nice, four-cornered, small blond beard. In the summer and winter, he wore an old, threadbare long coat, but everything [he wore] was clean and in good repair.

We young children, would call him ‘The Deaf Prayer Man.’ He cleaned the shtibl every day until 12 noon. Afterwards, he would go out into the city to collect charitable donations.

Briyeh the Bookbinder was a pauper in seven skirts. He lived off of binding regular books, and prayer books. Occasionally, he would be given a letter-writing book, from which one could learn how to write letters in Yiddish.

Even before the war, he didn't have any living from this, not even enough for bread and water, much less in wartime, when many Heders were closed. Who had the luxury to think about binding books when one was encircled with so many troubles?

[Page 435]

I don't remember exactly how many children he had, In only knew two of them, a boy, Moshe, and a girl, Gittl'leh. She was called Gittel'leh Briyeh's. At that time, she was 18 or 20 years old, but she looked like someone who was thirty years old. She was short, of middling build, and very broad in the beam. She wore those clothes that were handed down to her. Do understand, that in this kind of garb, her appearance was dismal, even though she did not have an unpleasant face. In think now, that if she had lived in better conditions, and she were to have worn more decent clothing, she would have looked quite nice, and maybe even have been a real beauty.

She spoke very slowly, haltingly. When she began to express a thought, it was necessary to wait a bit until she finished it. She would help out in homes with a variety of housework. Washing floors, bringing water from the nearby well, and go on errands.

She never begged for money. When someone wanted to give her something, just to be nice, not for work, she would reply:

– I – don't – want – it.

Why not, Gittel'leh?

I – have – not – yet – earned – it.

When she would come into a house, she would stand continuously at the door, until someone from the household would ay to her:

– What do you want, Gittel'leh?

– Do you need water? In will then bring it for you.

And the Neustadt resolved that Gittel'leh and the Shammes would be the appropriate couple for the purpose at hand.

But it was not all that easy to make this happen. They started to talk to Gittel'leh, and she didn't want to hear of it. In remember one time in an evening, several women came together in my home, who lived as neighbors nearby: Yocheved Rosenzweig, the wife of the Sofer, Faygeh the Dairyman's wife, and the old lady Shokhet's wife – the mother of Hona the Shokhet. They began give Gittel'leh an argument:

– Indeed, to be completely truthful, you are no longer a young girl. You bounce around among all the houses. What is this? Can your poor father support you? And to be completely truthful, what is to become of you? Such a nice young man, quiet, one doesn't hear his rustle….

Gittel'leh stood and took in all the arguments, not uttering a single word. Everyone thought that she was agreeable [to the proposition]. The women got up to leave, signifying that the issue had been resolved. In that process, the old Shokhet's lady remarks:

– Hah, Gittel'leh, we will, if God so wills it, make a wedding.

– In do not want a deaf bridegroom! In want a bridegroom that will be able to speak, just like me…

– Well, here you now have a new tzimmes with stuffing! – the women jumped up as if from hot coals – she is still being proud! The city is undertaking to clothe her, shoe her, provide beds, utensils, everything that a balabusta needs to have, and she stands haughty – needing to talk with him! What will you talk to him about, Gittel'leh? Will you tell him about your father's good fortune? The ships that he has that go about on the seas, will you talk to him about matters of the Torah, words of wisdom? She will talk to him! Even if one lives with a husband who hears, the less one talks to him, the better So much more so with a deaf husband….

[Page 436]

On that evening, we saw that from that match, nothing was going to ensue.

The task of communicating with the bridegroom was assumed by the balebatim of the Cuzmirer shtibl. As was the custom, man to man.

On an evening, after the combined Mincha-Maariv prayers, when the congregation disperses and only a few individuals remain behind, who are studying a chapter of the Mishnah, others a page in the Gemara, and also those, who just enjoy idling the time away, talking politics, or telling stories about righteous Jews, on one such evening, the Shammes was taken over to a side, and, in sign language, they began to talk about the proposed match.

There were already those, who with hand signs, and other means, were able to talk to the deaf person, so that he would be able to understand. When it came time to describe the pleasures of married life, we young children were driven away. From a distance, we could see how the deaf man's eyes began to sparkle. He began to cluck with his tongue, and bray like a young ass. He put his hand in his pocket, and took out a small wallet, tied up with string, and showed that he had a lot of money.

Later on, he began to stick out his hands to the men. This was supposed to mean: – when? When will this be? Here things went easier, even though they had to deal with a deaf person….

The distaff side did not hold up, and Gittel'leh was given better pay for her work, instead of a torn dress with holes and patches, she was given clean and repaired clothing; better shoes, also better food, commensurate with the wartime means. And every day, the women would ask in an aside, as follows:

– Will you marry the deaf man?

Gittel'leh ate the expensive food, and took great amusement from it, and shot a question: – do you need water? Look, the floor looks so dirty. This was meant to be the answer to the question that had been posed.

The matter did not stay still. Women began to plot with one another, and when they would meet, they would talk in whispers. It had the appearance of a new offensive being undertaken, and they don't want the secret to reach the enemy….

As it was related later on, it was the idea of a very clever lady. She said: ‘If we cannot do this by means of an ‘arranged match,’ let it be a ‘love match…’ we must exert every possible means to see that she falls in love with him…. after all, he is a man, a mensch right along with other menschen….So he cannot speak? Love has its own language!…. ’

– Go, deliver some food to the deaf man. The deaf man, poor soul, is ill.

– You'll have to wash the floor in the Shtibl tomorrow, pity, he can't do anything….

In the first days, she was paid extra in food for such a trip. Later on, she no longer demanded it. A little at a time, she got used to him. He would give her money, so that she should go and buy him something. When she brought back the purchased items, he would take the entire package and give it away to her. A little at a time, she began to learn to understand what he wanted, and she also was able to answer him in sign language….

On one morning, she came into our house, because our house was closest. We lived diagonally opposite the shtibl. She asked for a little boiled water. She needs it for the deaf man.

– Really? For the deaf man? – my mother asked her with feigned irony.

– Yes, for the deaf man, – she answered with a smile – he is such a decent deaf man!

[Page 437]

This was meant to convey that he was a decent man.

The good news, you understand, immediately spread all over the Neustadt. It shot through like a lightning bolt. From mouth to mouth, from house to house, and preparations were begun for the wedding.

An assessment was immediately put together for both of them. A table, benches, pots, bowls, glasses, were immediately brought into the home of the deaf man, all don in the blink of an eye, and the date and hour for the wedding was set.

On the day of the wedding, my mother put on her Sabbath dress.

– Mama, why are you putting such a dress on today, today is not Shabbat.

– I'm going to the wedding.

– What kind of wedding?

– Gittl'leh and the Deaf Man!

– In want to come with you.

– No! It is not for children. The wedding canopy is to be erected in the Holy Place!

My mother, along with a number of other neighbors, went off. With my childish mind, In began to think about this thing. In my heart, In took pity on Gittel'leh. It isn't enough that they are giving her a deaf bridegroom, so they couldn't find any better place for the canopy than in the cemetery.