|

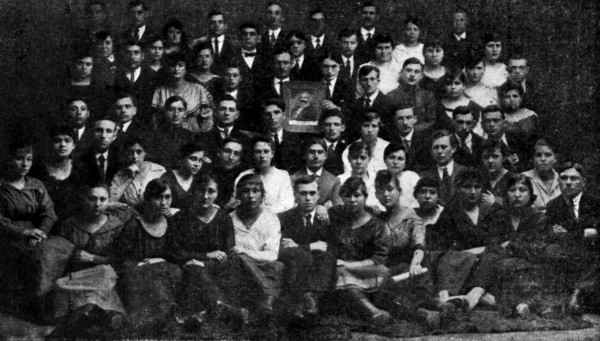

Photographed in the year 1917

|

|

[Page 305]

by Chaim Shpizeisen

The Jewish Socialist Movement in Zamość Up To World War I

An underground Socialist development network was already being run in Zamość in the nineties decade of the prior century. This was carried out by students in our city, who had studied out of the country, and who would come home on vacation from the university cities. They would bring back with them, a variety of illegal propaganda materials from the rising socialist movement in Russia. They printed periodicals and brochures on cigarette paper-thin paper which passed from hand-to-hand. In their intimate conversations, among comrades, they told about the various socialist directions that existed in Russia. However, no visible organization was created.

Also, the works of the classic Yiddish writers began to appear, Peretz, Mendele, Dinensohn, and others, in whose content the young Yiddish reader was able already to find ideas that appealed to them, which the socialist propagandists have spread about.

The writer of these lines, in the years 1900-1901, was able to get access to such literature, that has just been described, from fraternal cups.

My friend Fishl Geliebter ע”ה, supplied me with the illegal propaganda literature.

This was already the time, where developments of organizing activity began, and the foundation for the Bundist movement in Zamość was laid. At that time in Zamość, the construction of a concrete army barracks for the Russian army was completed. Many Jewish craftsmen were involved: carpenters, table makers, artists, metalworkers, locksmiths and others from the surrounding villages, where there already was an organized Jewish labor movement under the leadership of the Bund. With the help of the local Jewish intelligentsia, who were the first in the movement, the workers organized themselves, and established strike-funds.

At the point of the movement stood the comrades: brother Ashkenazi, sister Huberman, Fishl Geliebter, Yerakhmiel Brandwein, and others, who led the work under the banner of the Bund.

The first strike took place in 1903, by the Jewish hat makers.

This writer returned from Minsk in White Russia in the summer of 1905, who began to create the organization of the ‘S.S.’ (Leadership of ‘Zionist-Socialist’ Labor Movement). Until then the Bund was without competition on the Jewish labor street in Zamość.

The work of the ‘S.S.’ consisted of distributing literature, you should understand, primarily illegal: pamphlets, brochures, invitations; leading circles, mass meetings, lectures, and we, like the Bund, had our own ‘exchange.’

In the Jewish labor movement, a period of contentious debate and ideological discussions began, disputes about the programs, and a struggle for influence over the masses. This, however, did not disrupt the many-branched activities of the struggle. Continuous strikes are launched in the various trades of the ranks of Jewish labor. Better working conditions are negotiated; higher wages; a shorter work day; a recognition of the professional organization; consideration for the Jewish worker, youth, and so forth.

In the revolutionary years of 1905, the days of great turmoil come to all of Russia, and to our Zamość, its Jewish workers were not on the sidelines. When the huge demonstrations took place in Russia, after October 17, 1905 we had an analogous demonstration by the Jewish and Polish socialist and revolutionary organizations.

[Page 306]

After the Czarist ‘Freedom-Manifesto,’ when the black wave of police terror began in Russia, it also did not spare our city. Frightened by the revolutionary movement that had grown, the reaction began to ‘constrain,’ the movement. Extraordinary circumstances are proclaimed. There are arrests and terror, and in other places, pogroms.

The balebatim of Zamość utilize the excuse of the uprising, and desire to retract the improvements in working conditions from their workers that had been negotiated. With the consent of the police, they then organize an attack, with truncheons, against the intelligentsia, who had taken part in the organization of the local Jewish labor movement. This was intended to be a provocation, to elicit a street fight from the ranks of the workers, which would have made it easier for the Czarist police to ‘intervene.’

The writer of these lines was among the first who was attacked by this band. When the news of this provocation became known among the workers, they wanted to leave their work, and go out into the streets, but the leadership had immediately oriented itself to the situation, and ordered the workers to restrain themselves and not engage in bloodshed and to engender further provocation.

Afterwards, the attack was brought to the courts, and part of the leaders [of the attack] received up to a month of arrest.

Despite the fact that a number of comrades were compelled to leave the city, because of the increased terror, the work was not disrupted.

The ‘S.S.’ at that time, released its first own published leaflet, a warning to the leadership. The ‘S.S.’ released a second leaflet on the anniversary of the Bloody Sunday of January 9, 1906.The leadership of the ‘S.S.’ were: Chaim Shpizeisen, Iteh Geliebter (daughter of Elkanah Geliebter), and Yaakov Geliebter.

There were strikes and fighting throughout the entire year of 1906. For the tailors and shoemakers by the Bund; For the bakers and brush makers, by the ‘S.S.’

At the end of 1906, arrests were carried out among the leaders of the movement. The Bundist leaders Ashkenazi, Andzheh Huberman, and Yerakhmiel Brandwein were arrested and exiled to Siberia. Fishl Geliebter emigrated to America. From the ‘S.S.’ Shpizeisen and Iteh Geliebter went to Warsaw.

The work, however, did not cease. New activists arose, who took the place of the departed.

A provocation (instigated by Lejzor Moshe-Sarah's, a brother of Esther Moshe-Yekl's wife), cause the committee to be arrested. The collective was arrested and deported from Poland. Among them, Hirsch Fruchtgaten, who later was the leader of the Bund in Chelm, and was killed in the Warsaw Ghetto, and Mendel Epstein, the son of Rabi of the Neustadt, and active member of the Bund, today in America. This work almost came to a halt.

Those who remained, under no circumstances, wanted to give up their activity, sought other means by which to sustain the movement. The existing library, named for Gedaliah Hoffman was already legalized (we will have the opportunity to discuss this library at many other points). However, this did not create satisfaction. The desire was to transform the library into a community library with a reading room. An attempt was made to open a branch of ‘HaZamir.’ This did not succeed. So a division of the literary society was organized, which had its central office in Petersburg. When we finally got legal permission, the central office of the society was closed, and all of its branches.

In the end, the local activists got legal permission to establish a local culture society, with its own governance. The leadership of this society was: Mordechai Bekher, B. Feder, in addition to these who have been mentioned, the following residents signed the charter: Jonathan Eibeschutz, Schneerson, Ashkenazi, Y. Y. Peretz, and others, all prominent people in the city.

[Page 307]

In the year 1911, our comrades Yerakhmiel Brandwein, Chaim Shpizeisen and Herschel Fruchtgarten return from exile, who then take up the work of the society and help to organize it.

In the year 1912, after an extensive amount of effort, the long-dreamed-for local is rented. The library is organized their, which after the death if I. L. Peretz gets the name ‘I. L. Peretz Library.’

This library became the spiritual center of modern Jewish Zamość; [it was] the new Bet HaMedrash for the worldly generation. It transformed the broken labor movement. It was here, that the few who managed to save themselves from prison, Siberia, or dispersion, would gather, and remain true to their ideals.

It is here that all the citizenry would spend time. With all the developments of the world; here in friendship, literally idealistically ‘fought’ with one another, debated, with each person defending his own perception of the truth.

This is the way it existed up to 1914, until the First World War.

The First Great Demonstration in Zamość in the Year 1905

|

|

| A portion of the active people and members of the Trade Unions in Zamość, Photographed in the year 1917 |

It was after October 17, 1905; after the day in which the Czar of All Russias, Nicholas II, granted the people a ‘constitution.’ He promulgated the decree for a ‘People's Duma’ (Parliament). An awesome wave of demonstrations cascaded through the entire huge Russian Empire. The revolutionary camp thought of this as a victory, and wanted, through these demonstrations, to celebrate its triumph. Zamość did not stand apart from the other cities of the land, and also here, there was a demonstration. The demonstration was organized by the Bund and the P. P. S. (the organization of the ‘SS’ did not yet exist).

The writer of these lines was invited by the Bund to participate in a preliminary council, which took place in the old Christian cemetery, which was the place from which in later years, the railroad tracks to Ludomir were put through. At this council, Naphtali Margalit, Salek Asch, Moshe Epstein, the brother and sister Dzhuba, and others, participated. It was decided that the demonstration would be held on the coming Friday. The gathering place was set near the river (Tashlikh), behind the engineering-garden.

Friday morning, the workers gathered at the appointed spot, Jews and Poles. At 10 o'clock, the train of people moved out, with banners and song, over the entire Lubliner Gasse. Schlossgasse, up to the church, and up to the Sztaszitza Gasse. Along the way, S. Ashkenazi, Arnold Ehrenreich, Moshe Goldstein and a number of Poles spoke. When the train came to the row of the covered sidewalks (Potchinehs), behind Klossowsky's Pharmacy, it ran into a wall of military forces with their guns drawn and raised. Salek then stuck out his breast and said: ‘Shoot!’

The crowd dispersed. S. Ashkenazi and a number of others were detained, but were released that same day.

Moshe Goldstein, who while marching past the gymnasium, knocked the hat off the head of a gymnasium teacher, was several days later arrested by the gendarmerie, and was immediately sent to Siberia. However, while en route, the amnesty proclamation of the Czar, issued at that time, reached him, and he returned immediately.

Bund and Trade Union Movement in Zamość between the Two World Wars (1914 - 1939)

|

|

| A group of activists at the ‘Y. Sh. O.’ Peretz-Library and Bund, in Zamość |

|

|

| Committee of ‘Zukunft,’ the Bundist-Youth Organization in Zamość for 1939 |

In the last years of the First World War political-revolutionary activity, which had been well branched out by the time of the first revolution in Russia (1905 and later), had already been choked off. The entire activity of the democratic

[Page 308]

-progressive community work was directed out of the library, where those who had been drawn into the prior revolutionary movement had concentrated themselves.

It was first in the years 1916-1917, during the Austrian occupation, that signs of a renewed political activity became visible; professional worker organizations began to be created, each according to their own trade, and afterwards, a council was created of the trade unions, however, no obvious political activity was carried on, even though the prior active members of the Bund, and other organizations, stood at the head of this group.

It was only at the time that Poland became independent, that a lively political activity began, and a strengthening of the professional organizations. Frequent debates, formal sit-down evenings, theater presentations, and other cultural undertakings, then come out on the surface of political Jewish organizations, such as Bund and ‘Tze'irei Tzion,’ and others.

Those who revived the Bundist movement in Zamość were the comrades Itzik Goldstein (today in Russia), Yerakhmiel Brandwein ( killed by the Nazis in the Minevich Ghetto), Mikh'cheh Levin (today in New York), Salek Leviv ( killed in Russia during the civil war after the revolution), Chaim Shtikh, Mordechai Zwillich, Abish Shpizeisen ( all 3 killed by the Hitler-bandits), Itcheh-Leib Herring, Shia Bin (both in New York), Mendel Sznur, and others.

Under the influence of the Bolshevist Revolution in Russia, the Russian Bund created an entity that drew it to Bolshevism, the ‘Combund.’ These sentiments also carried over into Poland, where in the ranks of the Bund, such an entity was created, which formed itself as a ‘Combund,’ and afterwards went into the Communist Party.

A process of this kind also took place in Zamość. A group of workers, which came out of the local Bund organization had previously created a ‘Combund,’ and later, they became the ones who founded the Communist organization in Zamość.

As the Bolshevist army drew near to Zamość in the year 1920, the so-called ‘Red Revolution’ took place by us. A great number of the Jewish elements who were radical sympathizers were drawn into it. After the ‘revolution’ failed, a whole array of Bundists were compelled to leave Zamość – some to Russia, some to America.

The Bund suffers greatly from this splitting up and from the mood of the times. It is primarily weakened in the professional [sic: trade] movement. The older workers, formerly under the influence of the Bund, now become ‘independent;’ the economic crisis forces them to ‘be for themselves,’ – they abandon the professional organizations. The activity of the Bund in the professional organization diminishes. The communists obtain influence in a whole array of professional trade unions. In the course of a few years up to 1923, the influence of the Bund in most unions is entirely eliminated. The leadership, in particular, is in the hands of younger people, radicalized, after the victory of the Bolshevist Revolution in Russia.

In the year 1923, after overcoming the internal ‘Combundist’ schism, a renewal of Bundist activity begins. Under the influence of the comrade, Hella Ashkenazi, Moshe Mittelpunkt, Mordechai Zwillich, Rachel Korngold, and the writer of these lines, the Bund organization is built up again. Once again, the Bund makes an effort to become active in the trade union movement.

There were no great successes to talk about during the first years. The principal focus of the Bund is placed on Cultural-Social activities. Under the influence of the Bund, the local branch of the Jewish School Organization is established, which founds and directs the Zamość I. L. Peretz School for a number of years; the Peretz Library is passed from ‘hand-to-hand,’ but is found mostly under the direction of Bundists and their sympathizers; a Drama Circle is created, which is greatly beloved in the city, which helps out its affiliated organizations; with the initiative of the Bund, a commerce-based union is established, the transport workers union, the baker's union, and the socialist hand workers' union. The baker's union and the socialist hand workers' union which plays a very prominent role in native life, election campaigns to the municipal council, and the community, where the sympathies for the Bund grow from one election to the next.

[Page 309]

A Bundist-youth organization, ‘Zukunft,’ is established, whose leadership is: Herschel Orenstein, Gershon-Henoch Cooper, Yaakov Mandelbaum. There are frequent debates with guests brought in from out of town.

Concerning the sympathies of the Jewish population of Zamość on the eve of the Holocaust, the results of the city council elections of 1939 are characteristic.

Of the 24 councilmen in the city council, at this occasion, 6 Jews were allowed to serve, thanks to the specific ‘election-demography,’ that had been agreed to, where the Jewish regions received fewer representatives, and an array of villages were incorporated into the city… before this, Jews had between 12-13 representatives in the city council.

The elected Jewish councilmen were all from the socialist camp.

For this election, the Bund agreed to a bloc with the Jewish ‘left.’ This was at the time that the Comintern had abandoned the Polish Communist Party, and the members then grouped themselves into an ‘opposition,’ in the professional unions. A bloc from the Bund professional unions went to this election. Of the 5 elected, 3 were Bundists and 2 from the trade unions.

The sixth elected councilman was from the right-wing Poalei-Tzion.

|

|

| This picture is from the visit of I. L. Peretz in Zamość, which is described here. In front of the ‘Polish House.’ |

It was October 1913, this period of time was referred to as ‘Prizivzeit,’ when the draft-eligible young people would be called for conscription at the military commission. Peretz came for a visit to his mother, Riveleh, in Zamość.

Thursday evening we, the library-activists, become aware that Peretz has arrived. Immediately, our comrade Yerakhmiel Brandwein, whom Peretz already knows from a prior visit, is delegated to discover whether our guest would not be opposed to giving us a lecture. I. L. Peretz agrees to this immediately on the spot.

Not being mindful that all we had was a short Friday in which to formally arrange the lecture, we exert ourselves to make this happen. Ignacy Margolis, the important city citizen exerts himself in the ‘Recruitment-Hall,’ and approached the ‘Powiat-Nachalnik,’ asking him to make an exception and to permit the lecture to take place. The latter gives his permission.

It is Friday – how does one inform the public? However, in the course of numbered hours, the printer Szper gets the placards ready, and they are posted all over the city immediately.

Saturday, during the day, the ‘Oazow’ cinema is packed with people; young and old have come to listen, among the public were many Hasidic boys and young people. I. L. Peretz then related a number of his folk tales, which had not yet been published. You can appreciate this was done with suitable introductions and special insights, as he could masterfully do. The audience was inspired.

In the evening, Saturday at night, a Melave-Malkeh took place at the house of Dr. Y. Geliebter – a singular honor for the guest. This was organized in partnership with the library activists, and the owner of the house. We enjoyed each other's company until late at night. For the most part, this was the evening of final goodbyes with I. L. Peretz, whom they did not see again.

The next day, Sunday morning, before departure, a large crowned gathered at the ‘Polish House,’ here the young gymnasium student Stash Huberman photographed I. L. Peretz with those who came to see him off. Also, this photograph is one of the last documents of Peretz's final visit to his home town.

[Page 310]

The I. L. Peretz Library in Zamość

|

|

before it was destroyed by a police pogrom From right to left, standing are: A. Miller, Ph. Topf, Sh. Goldstein, Y. Schiff, Y. Gartenkraut, A. Richtman; Sitting: Y. Brandwein, Y. M. Topf, A. Neimark, L. Finkman |

I have already mentioned how the I. L. Peretz Library came to be, and became the gathering point for those who got their education and in its day were active in the labor movement. But it is necessary to tell more extensively about this beloved institution, so that this will stand as a memory forever.

These following lines of mine, are being written years later, in the destroyed German city of Stettin, now a part of Poland. I am not yet ‘unpacked,’ and stand yet again to continue my journey. I am writing from memory, and therefore it is possible that I may omit something, or switch dates.[1]

As is known, Zamość was renown in the wider world for its scholars and learned people, but it was also known for its large and unusual collections of sforim[2] and books, which Zamość possessed – both owned by the community and held privately.

The collection of sforim of the great Bet HaMedrash in the Altstadt was an object of awe in the rabbinical world. It used to be told that Rabbis from faraway places would submit questions to Zamość, as to whether it is possible that a certain book might not be found there, or some other responsa, which they needed in order to resolve certain issues.

Apart from the large collection of sforim, the community of Maskilim, enlightened and free-thinking, for who the sforim of the Bet HaMedrash were not satisfying enough, also had a place. [It was a place] where they could obtain that which they deemed missing, and which they desired. – By David Shifman, who was the proprietor of a book business, it was possible to find the type of books that the ‘Germans’ were looking for. Incidentally, this Shifman was the correspondent of ‘HaMelitz,’ where in Number 21 of ‘HaMelitz,’ in the year 1878, he published a rather extensive correspondence from Zamość under the title, ‘A Tale of Zamość.’

A second place for someone with books was at [the house of] Goddel Melamed; in his residence there was a ‘Polish Minyan.’ This minyan was called this way, because that is where the men in ‘short jackets’ prayed. In the house of the previously mentioned Goddel, there was found a library of Hebrew books and journals (‘HaShakhar,’ ‘HaMelitz,’ and others). The writer of these lines derived much satisfaction from this [collection].

In that time, a follow-on request for a Yiddish book. This follow on request was satisfied at a certain time by Binyami'tcheh Fruchtman, the bookbinder (today in America). It was possible to obtain a book on loan from him for a few groschen.

At the end of the 90s, of the past century, there was a serious, secret little library with the brothers Mordechai and Yetcheh Bekher (Kokeh's). The very first of the Jewish students, sympathetic to the revolution, were the first to make use of this little library.

For a period of time, a tea salon was opened on the third floor of the home of the treasurer, where it was possible to read a Hebrew periodical (there were no Yiddish ones at that time yet), and play chess.

The leader of this was Shmul'keh Grossbaum (a son-in-law to David Voveh), the father of the future Bund activist Dr. Saul Grossbaum. I was also a patron there, and you understand, clandestinely. This little tea salon, which was a sort of ‘club,’ was rumored to have been started by the Zionists, which had at that time, begun to organize themselves.

[Page 311]

In the later years, the entire first decade of the current century [sic: the 20th century], young people were occupied with the ‘revolution,’ – the various movements took up their time and their interest. They lived within these movements, and it is there that they obtained their reading material.

As I previously mentioned, the failed revolution brought about the establishment of our organization, which was called ‘Library Reading-Room.’

This was possible because, the bottom of the charter was signed by 10 of the most prominent intelligent citizens of Zamość: Jonah-Joshua Peretz; Shmuel Ashkenazi; Yehonatan Eibeschutz, and Schneerson (the last two, son-in-laws of Shmuel-Leibusz Levin). The actual establishment of this library took place in 1912.

Zamość was a city with taste. The library needed to be organized so that it would have a following, meaning, that it should satisfy the pampered Zamość [intelligentsia].

The ‘hoi-polloi,’ after a year of effort, worked out the charter, but it was the young people who got on with running the library, carrying out the necessary tasks, being the real force at that time. Among the active people I will recall: B. Feder, M. Bekher, Y. Brandwein, David Cohen, the writer of these lines, and many others.

A location with 4 rooms was rented, which was furnished with new tables, benches and stools. For the reading room, Russian, Polish, Hebrew and Yiddish periodicals were written. The library was opened. Everyone could get what they wanted, and the success was literally colossal, exceeding all expectations.

Right from the start the library signed up more than 300 members. The budget was placed on sound footing. The library was open every day from 6 to 9 and until 11 in the reading room. This location became the meeting place of the entire young Jewish enlightened intelligentsia. Here was the place that the increasingly knowledgeable segment of the Jewish working class began to get together, who years before had made the first footsteps in the revolutionary movement.

During the Austrian occupation (1915-1916) the library was moved to the house of Avigdor Inlander in the center of the city.

I cannot tell about the occupation period, up to the year 1922, because I was away from Zamość.

In the year 1922, in the time of the revolutionary upswing, the Jewish working class utilized the library as a meeting place. This did not please the Polish authorities of that time. In the year 1923, was closed down by the authorities, as well as the right of appeal.

The books and the inventory were turned over to the control of a selection liquidation commission, which consisted of the following people: Y. Brandwein, Ch. Shtikh, David Cohen, Eliyahu Richtman, Ch. Shpizeisen, and others.

The liquidation commission immediately began to search for a way out, trying to get the library re-opened. Because the prior library leadership, that functioned under the old charter, could not submit an appeal, a fresh charter was submitted, with new signers of older ‘loyal’ citizens. The charter contained an array of constraints, which the authorities demanded, for example, a member had to be at least 24 years old.

After a year of tribulation, and large expenses, the authorities still did not want to approve the charter. No form of intervention helped.

The ‘liquidation commission’ faced a critical situation. It had to pay the landlord of the premises for the closed library – and there was no income.

[Page 312]

When all attempts to legalize the library on the basis of a local charter produced no result, other means were sought. The liquidation commission decided to legalize the library as a branch of a central institution, which could, following its charters, open a library in the province.

The writer of these lines then traveled to Warsaw to find such a ‘central organization.’ The ‘Culture-League’ Society in ‘Tz. Sh. O.’ did not have a point in their charter that would enable them to open a library in the province. The society for ‘Evening Courses for Workers,’ however, did have a right to do this, but it opened its branches in those locations where it had its adherents (the ‘Society Evening Courses’ was under the influence of the Poalei-Tzion – leftists), and it was these adherents who managed the library. This movement did not exist in Zamość.

With a recommendation from the writer, Leo Finkelstein, we approached the ‘League for the Education of the People,’ which stood under the influence of Volkists (Prilutsky's adherents), for this ‘League’ to take over the library and legalize it as its branch. This society, in fact, had the right to open libraries throughout all of Poland.

After a set of formalities, which lasted several months, the library was opened again in January 1926.

Moshe Levin became the Chairman of the society; the librarian accountable to the authorities was B. Feder. The library came to life once again. A radio was installed. The library, once again, became the spiritual center and place of rest for a large part [of the people], especially the youth of the city. The Zamość branch of the leadership of the ‘People's Education League’ was responsible to the authorities, with Moshe Levin at its head. In reality, the library was run by the ‘Yiddish School Organization,’ (‘Y. Sh. O.’). A ‘double set of books,’ was required to satisfy the authorities.

In 1931 (springtime) the authorities closed down the central office of the ‘People's Education League,’ and all of its branches. Our library was also sealed off.

The ‘People's Education League,’ which was the formal organization of the Volkists, was in fact a fiction. The Volkists has adherents in very few Polish cities. Where they had larger groups. But in all of Poland, there was not a Zamość-like instance, where the authorities had prohibited the opening of a library. In this situation, there were an array of cities with Bund organizations, or communist groups, which were not permitted to open libraries. So, the ‘People's Education League’ would be approached, who was sympathetic to helping open its branches, with the calculation that those, in time, would be influenced… however the Volkist movement did not have the manpower or the apparatus to embrace and really control who came into and what transpired in its branches. The police, however, clearly knew that this ‘Central Office,’ was the ‘lightning rod’ for all the libraries that the local authorities did not want to have…

Several months passed before the library was re-opened. It became evident that we were standing before a real catastrophe – there was a substantial deficit and Mr. Inlander threatened eviction…

A difficult struggle began to keep the library.

Some time later, the library is shut yet again. A year goes by until it is opened again. This time, as a branch of the central ‘culture League,’ which was under the influence and direction of the Bund. The new statues of the ‘Culture League’ now did foresee the opening of libraries in the province.

The library, however, was drowned in debt. It was necessary to give up one of the four rooms to the landlord, Inlander; for this reason, the reading room is discontinued.

Once again, the library becomes the great culture-center of our city.

Together with the Jewish community, the Jewish library partakes in the fate of its builders, friends and readers.

[Page 313]

Apart from this Peretz-Library, there were an array of smaller libraries that existed in the city. In the Neustadt, a library and reading room, which went through a series of phases (this is related separately); In the year 1926, the Jewish trade unions also had a library and a reading room; Also, the Poalei-Tzion (Tz. S.) Had a library.

The Creation of the Yiddish-Secular School named for I. L. Peretz, in Zamość

|

|

From right to left: first row standing: Chaim Shtikh, Chaim Shpizeisen, Zalman-Gershon Gewirtzman, Mordechai Zwillich, David Cohen, Moshe Mittelpunkt; Second row sitting: the teacher, Itteh Lazar, Yerakhmiel Brandwein, Gedaliah Jonasgartel, Nekha Rak, Nahum Korngold; Last row, on the ground: Meir Sternfinkel, Rachel'leh Morgentstern |

|

|

In the middle from right to left: the teacher Itteh Lazar, the teacher Pearl Wein, board member Chaim Shpizeisen |

|

|

From right to left, seated: Leadership- committee member Moshe Mittelpunkt; Leadership member Ch. Shpizeisen; Teachers: Malka Haltz, Dina Rubins, Rivkah Profitker; Leadership-member Mordechai Zwillich |

At the time when the workers began to organize themselves in order to improve their economic condition, and at the same time also begin to take an interest in community political questions, they felt the lack of simple, elementary education. They saw, that they lacked a great deal by not being able to write and read, to be able to read a book or a newspaper.

The worker, who for the most part came from the poorest sector of the population, could not reach more than the level of a very basic teacher. He studies in a Heder (and usually this was not of the best sort), from which he took with him the knowledge of a little bit of Hebrew, in order to be able to pray a little form a siddur. Most of them did not know the meaning of the words.

The activists of the labor movement therefore had to approach their constituency not to talk about political, economic, and historical materialism, but one had to begin at the beginning, teaching them to read and write. It became possible for the writer of these lines to be involved in playing the role of a teacher in this respect.

In that stormy revolutionary time, during the revolutionary year of 1905, many cities and towns set up evening courses (mostly in secret) and in part of these places, Yiddish day schools for children. In Ludomir, the writer of these lines took an active part in the opening of a school in the year 1908.

At the time of the First World War, when Poland was liberated from Czarist rule, and later became independent, Jewish kindergartens were established in an array of cities. Later, the central Jewish School Organization, known by the initials ‘Tz.Sh. O.’ was established, which not only organizationally encompassed all secular Jewish school institutions, but also stepped up to unify their curricula and the character of these schools, while also supplying the needed material help for the established schools.

In the year 1924, the poet Melekh Ravitch visited Zamość. Through his initiative a group of ‘friends’ of the secular Jewish schools was founded. This group consisted of the following comrades: Chaim Shtikh, Rachel Korngold, Chaim Shpizeisen, Gedaliah Jonasgartel, David Cohen, and others. The group immediately began to carry out a lively program of activity, recruited friends, orgaized the first lectures by D. Neimark (Aryeh), Sh. Mendelsohn, and several months later, opened a branch of ‘Tz.S.O.’ in Zamość.

[Page 314]

At the first general meeting, the former Secretary-General of ‘Tz. Sh. O.’ comrade Yaakov Patt attended, who on the occasion of that visit, held a lecture on the theme of ‘Behind the Shops of the Last Half Century.’ At this gathering, the first leadership was selected, which consisted of the comrades: Gedaliah Jonasgartel, Chaim Shtikh, Chaim Shpizeisen, Moshe Mittelpunkt, Yerakhmiel Brandwein, Rachel Korngold, Nekha Rak, Zalman-Gershon Gewirtzman, and David Cohen. The leadership took to the work with great energy, and after a rather short time, the number of members had reached 200, who pays regular membership dues.

The leadership organized a drama circle under the direction of comrade Ben-Zion Zeidner. The drama circle performed many plays (this is separately described). Also, frequent debates were organized, and lectures with speakers from the outside, especially from the membership of the Jewish Literary Society in Warsaw. Apart from the spiritual enjoyment, these undertakings also generated a significant income.

At a conference of an array of ‘Tz. Sh. O.’ branches in Warsaw in the year 1926, it was decided that for the new school year, a school should be opened in an array of cities, among them, also Zamość.

We began to implement this recommendation. From an array of local undertakings, especially from the drama circle, and also in the local towns, a fund was created in order to be able to open a school.

But it was not so easy for us to find a location of the school. Apart from the fact that there was always a shortage of housing in Zamość, the city was also divided into three parts – Altstadt, Neustadt and ‘Browar.’ A location was needed that would at the very least lie between the two most important parts of Zamość – the city [sic: Altstadt] and the Neustadt, where most of the Jewish population lived. It was not possible to obtain such a location. A location suitable for a school was first available in ‘Browar,’ in the smallest section of Zamość.

This school location was entirely inaccessible for the children of the Neustadt, which because of their circumstance, and following common sense, should have been the beneficiaries of the Yiddish-secular school. It was also a little too far for the children of the Altstadt. Despite this, apart from being used by the ‘Browar’ children, the school was filled with the children of the city, and a few from the Neustadt. It is understood that the school progressed because of the commitment of parents to make use of it, and an ideological relationship to it.

The school developed quite well, and became beloved among the working-class Jewish people. In each successive year, a new, higher class, was opened.

The school brought a new form of Jewish life into the city. There were many presentations by the children, elections by the children, and festivals and parent assemblies.

For this entire time, the leadership thought of, and did not abandon the plan to open a second school, also in the Neustadt, which for the Yiddish-secular school was the right reservoir of students and, indeed, the appropriate social climate for such a school.

It was first in the year 1930, after much effort and struggle with the Neustadt authority, which resisted greatly, that such a school was opened in the Neustadt.

Let us here recall the exceptional fact, that no Jewish homeowner who had a suitable dwelling wanted to rent his premises for use by the people's school. Only one owner, a Jew, who had already rented the location, under the pressure from the religious-fanatic element of the Neustadt, retracted his deal. In the end, it was necessary to rent space form a Christian….

To our great disappointment, this important institution only survived for 6 years, and was forced to close for lack of financial resources.

[Page 315]

The city council, which at that time had a socialist majority, had approved subsidies, later stopped paying the subsidies. The central organization cut down on its help, and the aid from America came less frequently. All our alarm ‘SOS’ calls did not help… at the end of the year 1931, both schools closed with a large deficit.

Let us here recall those people, who assisted in the hard work of building and sustaining this important institution. Apart from the previously mentioned comrades, there were: Meir Sternfinkel (later the Bund councilman in the city council); Mordechai Zwillich, Nahum Korngold, Yasheh Mendelsohn, Mendel Blumenthal (teacher in the Yiddish-Polish gymnasium) and Tzesha Weiss. All of them are victims of Hitlerism.

Over the years, the following teachers worked in the schools:

The school year 1925-26 – Sonia Gershuni and Moshe Alman (today in Glasgow, Scotland, U.K.);

The school year 1926-27 – Itteh Lazar, Pearl Wein;

The school year 1927-28 – Dina Rubins, Rivkah Profitker, Malka Haltz;

The school year 1928-29 – D. Rubins, R. Profitker, and Esther Mendelsohn;

The school year 1929-30 – R. Profitker, E. Mendelsohn, and Reuven Tzipkin;

The school year 1930-31 – Zissel Fufiska, Brumberg and Shapiro.

It is possible that I have omitted someone from the leadership or from among the teachers.

There was an evening school as part of the school for a number of years, where courses were given for working people. These courses were given by the teachers Itteh Lazar, Dina Rubins, and the leadership members Ch. Shpizeisen and Y. Brandwein.

Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zamość, Poland

Zamość, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 11 Apr 2023 by JH