|

|

|

[Page 151]

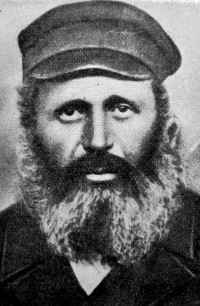

Father

Perhaps fate was kind to my father, Reb Nisl of blessed memory, allowing him to die before the Shoah[428]. He passed away in his illness and was buried in the cemetery in a tiny grave.

In life he was a revered, patriarchal figure. A man who worked hard to support his family of many daughters. But in spite of his worries about earning a living to support his large family he was happy and goodhearted, showing love for others, without sadness or nervousness. Even words of reproach were said with a smile on his face and without raising a hand. One sharp look was sufficient warning not to repeat the incorrect action.

He was a figure of love for his family and was liked by his neighbours and by all those with whom he came into contact – and there were many that he came into contact with. These were: the merchants from whom he purchased; the purchasers to whom he sold; the Jews who came to our house every Sabbath to study a page of Gemara[429], parts of Mishnah[430] and passages for the week and who incidentally shared a drink of Sabbath tea: the Jews who came for Melave Malka[431].

|

|

When the rebbe Reb Elimelekh of Karlin came to the shtetl where else would he stay if not in the house of Reb Nisl? And the congregation of followers accompanying the rebbe filled the house. My father was never a prosperous man. More than once I was amazed by his ability to support his family. In order to feed his large family and entertain the many visitors the outgoings were great and many. But in his words, 'The Lord helps those who help themselves'. The burden of the family was only part of the work placed upon the man in the shtetl. Father, as a devout man, began his day at dawn. Even before Reb Nisl Meirs appeared outside the window with his special tune 'Shteyt oyf [get up] to worship God' Father was by then ready to go to the synagogue with his talis[432] under his arm. A malignant illness cut the cord of his life.

Mother

With the death of Father of blessed memory Mother of blessed memory took upon herself the whole burden of housework and supporting the family. Mother, Liebe Nisl Leas, was a typical Jewish mother. She bore her role and the heavy burden of the family in silence. I wonder how she found the energy, the strength and the peace of mind to feed and clothe her children and at the same time to look after the needs of the poor.

[Page 152]

On Sabbath eve she would remember a certain mother who had not yet come to buy what her family needed for the Sabbath. That meant she was not able to find the money. It then fell to me to be the 'envoy of charity', bringing bread for Sabbath to that family and a cooked meal for another family. She found time to look after the family as well as everyone else.

She was a devout and believing woman. At the same time she was tolerant towards other people's opinions. She listened with great patience to an opinion not accepted in those days.

There were many children in the house. Each of them had a group of friends, boys and girls, all of whom congregated in the house. In spite of the fact that the house was large there was a lot of noise - noise of conversation, laughter and excitement. She had patience for them all. More than once now, when my children bring their friends home and there is a lot of noise and my nerves are on edge, I remember how my mother received all the friends hospitably, giving one a caress, the next a warm word and treating everyone with honour and respect. When I remember that I also regain control. Her behaviour acts as a guiding light.

|

|

You, all of you, my brothers and sisters: Ayzik, Khayke, Susil, Ida, Chana, Masha and Yosef and extended family, your memory will not dim as long as I live.

[Page 153]

|

|

|||

|

|

| Lea'ke Lopatyn-Cohen Kiryat Motzkin |

At first glance a simple Jew, a tradesman in a small shtetl. What is there to boast about in that? But go and look and count how many fine qualities God blessed him with. Throughout his life he was frail, yet the large, heavy sledgehammer danced in his hands, both in the heat of the summer and in the cold of the winter. By day and also on stormy winter evenings the beating of his hammer was heard from afar. He worked all his life, never tiring. He was attached to his work. Even as an old man he did not lay down his sledgehammer. He earned a living for his family in the sweat of his brow. 'God, do not make me dependent on other people's charity' he prayed three times a day. With those blessed hands of his he could make anything. He knew how to make a knife, hoe, sickle, scythe, rake, cart, he could shoe horses, repair hinges of windows and doors. At New Year he even made himself a shofar[433].

|

|

Everything sang in his blackened, cracked hands, covered with hard skin. But his hands were warm, always warm.

After a day's crushing hard labour he would arrive late for Sabbath in the prayer-house where he would study the Torah. For he was not only a man of labour; for him love of the Torah surpassed everything. At home or in the prayer-house he would study Eyn-Yaakov[434], chapters of the Mishnah[435], Gemara[436], Shulkhan Arukh[437], Rashi[438] and so on. The whole Sabbath was dedicated to study. Early in the morning he would go over the Sedra (weekly portion of the Torah). After returning from reading psalms and passages from the Bible and Targum[439] in the synagogue, it was his custom to study Gemara in the afternoon.

In the long, cold nights of Tebeth [Dec./Jan.] and Shevat [Jan./Feb.] in the company of the children and his wife, who was sitting plucking feathers round the stove, he would tell legends from ancient times or about our blessed sages. He quoted their maxims and sayings. Sometimes he would explain a passage from the Bible with great feeling and understanding because he loved the Bible. He was a reverent Jew. He acquired his teaching without any special training; he only studied in the cheyder. The rest he did by himself, for at the age of twelve they took him to work.

My father loved the language of the past. A large part of each of his letters was written in Hebrew. And how he enjoyed and was proud of the letters his sons wrote in Hebrew! He read them several times. He took them to the synagogue, read them out to the town elders. The rov also heard them. My father not only loved the holy language but also dreamed of the Holy Land where his sons were among those making the dream a reality. He, who all his life had been opposed to bringing the coming of the Messiah forward before the due time. In one of his last letters he writes: 'We don't lack anything here. Of course we miss you, but there is no longing

[Page 155]

for the land of exile. The only thing we want is to be with you in our Holy Land. And if God will not grant me many more years I hope to be buried in Eretz Israel'.

And what a warm bond he had with trees and with animals! How did a Jew, a product of this small shtetl, know so much about the grafting of the tree, how to prune it, tend and nurture it? The same care for animals – for a cow, a horse, and even a cat. He would milk the cow with great affection, feed her and stand, looking into her eyes, lead her to the river to drink from the winter waters. He would smooth and caress the back of each of the cows tenderly. He would enjoy looking at a beautiful thoroughbred cow or horse. He would speak about them with great expertise and get enjoyment from them.

There is no describing his deep, silent love for his sons, against whom he never raised his hand, not even his voice. He aspired to raise them for good qualities and good deeds, to diligence, good manners, love of the Torah and love of the people, another characteristic of his.

Respect for and love of the common people were a guiding principle. This led him to share the sorrow of the next man and help wherever he could. He would hurry to 'do good', and not just to a Jew, also to a 'Goy'. He would help a stranger and our neighbours. Even complete strangers were among those who visited our home. They loved and respected him.

He did everything silently and modestly. He was a sociable fellow, a peacemaker, modest, humble and shy. Although his seat in the synagogue was 'in the east'[440] in his life he would be distant from 'people of the east'. He made friends with people, those who knew the Torah, humble and modest like him.

|

|

[Page 156]

My Mother

'A Hebrew woman, who knows anything about your life? You came in darkness and you will go in darkness. Your sorrow and joy, your heartbreak, your yearnings will be born within you, they will end within you.'[441]

It is as if these words were said about you; it is as if the poet had you in mind in his expression 'eternal slavery'.

A hard life, a life of labour and hardship, a life of suffering, sadness and distress was your lot - more than for others. You gave birth to seven sons and brought them up in terrible conditions without any help, without encouragement or solace, without a word of praise.

Then they grew up and scattered in various directions: 'Like birds they flew, my children migrated,' you would often say with tears in your eyes.

You were always busy; you would get up before dawn, you worked, laboured without rest or pause until midnight. And who recognised you as the heroine you were? Who bothered to praise you? It was all taken for granted. For apart from raising children in poverty and deprivation, you cooked and baked, you washed and cleaned, you organised your home, you brought water from afar, you cut wood for heating, you sewed and mended, milked the cows and bred chickens, grew vegetables and went to collect debts. And in the evenings by a small oil-lamp you would linger over Sabbath and darn socks and gloves for your children until sleep fell over you. A mother's profound love, devoted without limit, but without complaint. You made your sacrifices instinctively. You saved from your bread and paid school fees for your children. You removed every obstacle from their paths. Your motto was 'May they have as much as everyone else'. Not once did you sit to eat at the table with everyone else, you never tired, you only knew how to serve other people. Everything of yours was for your family. What was left over for you?

Blessed be your memory.

| Dina Tkach-Ilan Degania Alef |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Vysotsk, Ukraine

Vysotsk, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 29 Apr 2016 by LA