|

|

|

[Page 309]

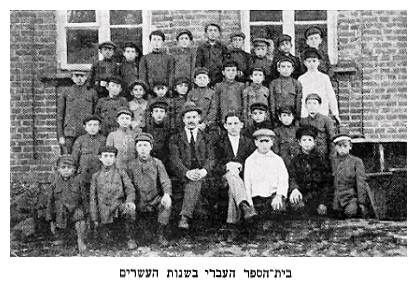

The Tarbut Schools

When Polish rule was established, a law of compulsory education came into effect. School age children were registered. The language of instruction was Polish. A great outcry arose in the village: “Our children are being led to apostasy!” The Zionist circles rose to action. One Motzei Shabbos (Saturday night), when most of the village's Jews were in the synagogue, they convened a general meeting. Aaron Ablov and Yosef Vigdorovich explained to the assembled public that there is no choice but to establish a modern school that would be recognized by the government authorities but in a Jewish spirit. Most of the audience was convinced. On the spot, they chose a committee to organize and activate the decisions made that night to establish a Jewish school that would be recognized by the Polish authorities. The Melamdim and those active in traditional Jewish education vehemently rejected this plan because it ignored the vital importance of religious instruction. However, many activists from both the older and younger generations joined the committee notwithstanding. They included Yitzchak Grezlasky, Berl Paretzky, and others who did succeed in setting up the school. The school's classrooms were in the women's sections of the synagogues. A teacher's union was set up and a principal chosen. The Polish teacher, a woman named Kovalski from Lodz, had a Polish Teacher's Certificate so the license for the school was obtained in her name. She was Jew completely assimilated into Polish society.

|

|

Aaron Ablov taught general history and Hebrew, the language of instruction. Dovid Shklarovsky was the math and geography teacher. The daughter of the Ostryn Rabbi, the teacher Gittel, was the teacher for all the younger classes. Moshe Berzovsky was the music teacher. The town melamdim also were appended to the teaching staff. They taught Tanach (Bible) with the commentary of Rashi. Because of a shortage of qualified teachers, the Headquarters of the Tarbut schools in Vilna could not supply certified teachers at first. They made do with teachers from the local work force. In the school's second year, two registered teachers were sent: Chazan Tzigelinitzky.

[Page 310]

They changed Principals, too. A teacher from Lida named Novoprutzky came to replace the original one. His subjects were Polish and mathematics (An interesting note: The children were taught mathematics in their mother tongue Yiddish while all the rest of the subjects were taught in Hebrew.) From year to year, more certified teachers were added to the staff; and the student body grew. The school was on the rise.

A New Building for the Tarbut School

The classrooms in the women's sections of the synagogues could not hold the student body. A vacant lot was allotted to erect a building for the school. The public was very excited about the idea but the financial resources were limited. Some tens of parents and activists in the field of education volunteered for the new school. They donated days of work, dragged bricks and building materials, and served as assistants to the professional construction workers. Construction continued for years and was finally finished in 1935. The Tarbut School moved to its new wider and more comfortable and appropriate quarters.

Gradually, the local teachers left the school staff. Outside teachers with government certification took their places. Serving alternately in the position of Principal were Chazah, Klecko, Bronstein, Kramer and others. The school reached a high academic level and was acclaimed throughout the vicinity. Many neighboring communities sent their children to learn at the Tarbut School in Ostryn. Under the school's direction, a choir and orchestra, led by the very talented teacher Lazer Kaplinsky, were formed. From period to period, the school's students presented performances before audiences. These performances pleased the public very much and helped to unite them in support of the school. Every Lag B'Omer (33rd day of the counting of the Omer between Passover and Shavuos--a Jewish children's holiday) the traditional trip to the Halovisky Forest took place. The band led the way. The children spent the day playing games and singing and dancing in the heart of nature.

Most of the populace supported the Tarbut School, even the religious because time was invested in religious studies too. Usually the students paid tuition. Only the poorest students were released from the obligation to pay. There was a parent committee responsible for the financial and organizational matters of the school. Among the parents on this committee, a few names stood out. Berl Paretsky was the connection with the headquarters of the Tarbut schools. Yitzkak Grazelsky supervised religious affairs and organized a special minyan for the students, honoring them on the Sabbath and Holidays by calling them up to the Torah and Ezra Meierov, Motke Meierov and Yosef Vigdorovich. Over time, the Tarbut School became the cultural center of the village. The sounds of Hebrew being spoken could be heard in the streets and houses. The Nazi murderers silenced the voice of Hebrew in the village.

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

The sources of livelihood were: trade and crafts. They were the ones who supplied the farmers and farms in the area with their needs: industrial and craft products, agricultural implements, and various services.

There were grocers whose livelihood was abundant and there were those whose livelihood was limited, they barely existed, because their shops were half empty. In the middle of the market, in summer and winter, they market women sat in their stalls which were filled with baskets and crates of vegetables and fruit.

In the scorching heat of summer, the cold of winter, and the dampness of the rainy season, they did not leave their guard,

[Page 311]

their workplace, they expected buyers, because, as usual, the revenue was small, except on market days. In the fall and winter, they would warm their frozen limbs with heaters.

The tiny grocers ran around the market looking for charity or short-term loans, to pay bills that were due, taxes that were overdue, and the danger was great! The government collector would take their assets and sell their meager possessions.

Everyone looked forward to the day in which they obtained revenue, the second day of the week, the market day in the town. On this day, dozens of stalls and booths were set up in the market, hatters, furriers, lathe operators, tanners and bakers offered their produce to customers from the village. On this day, merchants and artisans from nearby towns came to the market and they also offered their wares and produce to customers.

It was an ancient custom. The market was open to all who came to it.

|

|

The artisans and the merchants from Ostryn would move between the surrounding villages with their goods depending on the market day. They would bring to the markets: boots, shoes, hats, leather goods and clothing, sewing accessories, etc. They would wander from market to market to find their meager livelihood.

A number of wholesalers in Ostryn traded in meat, grains, eggs, butter, mushrooms, seeds, linen, pig hair, and animal skins.

The owners of the granaries were well known: Krinsky Chaim, Akiva Borochowitz, and Gedaliah Beno.

On the eve of market day, the wholesalers would distribute cash to the small merchants, so they could buy for them whatever came near as their agents. At the end of the market day, they would settle accounts. And everything was done according to trust. The wholesaler's trust in his small merchant friend was unwavering.

There were grain merchants who would lend directly to farmers for the next harvest, while the grain was still growing in the fields.

Peddlers

Jewish peddlers would wander through villages in their carts, offering their wares to farmers.

[Page 312]

in cash or in exchange. They would sell haberdashery: needles, threads, mirrors, combs, and handkerchiefs to the peasants' women.

In exchange, they would receive: rags, animal skins, mushrooms, eggs, and butter.

Among the vendors were also the “wayfarers”. The “wayfarer” would walk from village to village, with his “shop” loaded on his shoulders. He would also sell haberdashery. The struggle for a livelihood in the face of austerity was difficult and bitter.

Ostryn grocers would purchase their goods in the major cities of Poland, but Ostryn's “capital” was Grodno. Here a resident of Ostryn felt at home. Here they purchased their personal necessities, which were not available in the town, here they examined young virgin girls who were nubile, here they updated in trends and fashion, here they held meetings of brides and grooms, here they spent their free time.

There was a hostel in Grodno, in the courtyard of the shamash on Mishchensky Street. This hostel served as a meeting place for the people of Ostryn. A young man, who was a Torah scholar in Grodno, his family would send him packages here, and he would receive them.

A bride, who was waiting for the tailors in Grodno to finish sewing her wedding dress, stayed here. A “sick”, who came to be cured by the doctors of Grodno, would stay here between his examinations. In short, Grodno was the second home of the residents of Ostryn.

Lumber Trade

Ostryn, as well as the entire surrounding area, was rich in pine forests. For years, Jews made their living in the lumber trade. The Jewish lumber merchants were experts in this.

The wholesalers among them were: Yehoshua Bernstein, Yehoshua Zapolansky, Aharon and Yeshayahu Krinsky. A wholesaler or group of lumber merchants would buy pine forests connected to the land from the “noblemen” in the area. The “nobleman” got his payment and the forest passed into the hands of the Jews. The Jewish merchants were the ones who cut down the trees, sorted them, processed them, and shipped them to wherever they were needed.

The season - in winter, the farmers were free for outdoor work. The roads, the main roads, were snowy and frozen and suitable for transporting the trees in sledges. The processed trees would be sent to the nearby train station, to the surrounding lakes or to the Kotra River, a runnel of the Neman River. When the ice melted, they would sail barges on the Kotra River and the lakes, which flowed into the Neman River, the great river. And from the Neman to the Baltic Sea as far as East Prussia. The livelihood of the experts was abundant. In return for their work, the farmers received “notes”, which were accepted in all the shops and taverns in the town as an agreed and legal means of payment.

There was also a timber trading chamber in Ostryn, a partnership of three famous lumber merchants in Poland: Heller, Klatsky and Margaliot. They were not residents of the town. They lived permanently in large cities. Residents of the town such as Yechiel Bryschansky, Leib Zaltsovsky and Nachman Tverkovsky, forestry experts, were their agents. Sometimes “trustees” would also come from outside to finalize a particular deal. The forest trade was multidimensional, and provided abundant livelihood for all those who were involved in it. It also broadened the horizons of the residents as they came into contact with the people of the wider world.

Water Mills

In the past, flour was ground in water mills, where there was water. There was such a mill in the town, it was the property of the Russian person, who, of course, leased it to the Jew

[Page 313]

who lived nearby and earned his living from it. It was located on Vasilyushk Street and drew water from the Ostrinki stream.

In 1914, when the Russians retreated, they burned down the wooden dam that held the water in the stream for the mill. The mill was completely destroyed and was never rebuilt.

In the village of Luibyski, there were two water mills, which were the property of the “noblemen” Botrila and Liszczyb. Their lessees were: Hirschel of Luibyski and his son Mendel Schwarzberd.

Another mill was in Karpaczoczyzna. Its lessees were: the Sheklarowski brothers. Later on, the Sheklarowski brothers built a steam mill in the town. Its managers were: David Sheklarowski, Yosef Vigdorovich and Chaim Velitzky. Starting in 1935, this mill provided electricity to the town's residents until midnight.

The Polish Dispossession Policy

In the early 1930s, the government intensified its anti-Jewish policy. The heavy taxes dating back to the days of Grabowski and the “Ubshem” policy (Please, Jews! Are you having a hard time in Poland? Go to your Palestine) pressured and destroyed the Jewish merchants and craftsmen.

The anti-Semitic propaganda among the farmers increased. They were incited to boycott the Jews. Neither buy from them nor sell to them.

A group of Polish anti-Semites, led by Sanecki of Kobrovce, initiated the establishment of a Polish cooperative called “The Farmer” near the Jewish shops in the market. The Jewish grocers saw a danger to their livelihood in the existence of the cooperative. It would completely deprive them of their meager livelihood. They tried to prevent the establishment of the cooperative. They turned to the authorities. They filed a lawsuit in court. - They were not responded. One bright day, a group of Jewish women and girls went out to the market to forcibly prevent the construction of a building for the cooperative “The Farmer”.

That same day they were arrested and sent to prison in Lida. Only after much effort they were they released. In the middle of the Jewish commercial center a two-story building appeared, on the first floor - a large store for food supplies, agricultural equipment and a grain barn. On the second floor - a restaurant.

Students incite the farmers

On one market day in 1934, a group of students arrived in Ostryn and began inciting against the Jews. The farmers were enthusiastic and began robbing Jewish stores. (the stores of Ezra Meirov and Gershon Filovsky).

Without delay, a Jewish self-defense was organized. They set fire to the wagons of several farmers. Panic broke out in the market; the horses ran wild from the fear of the fire that broke out and trampled many farmers. The self-defense forces found the inciting students and severely injured them.

The farmers sobered up and returned empty-handed to their villages. A government investigation committee arrived, arrested a number of Jews and took them to Shchuchyn. A few days later they were released.

The Jews' show of strength against the attackers aroused a sense of respect among the farmers, and from that day on, the anti-Semitic riots in Ostryn ceased.

Credit Institutions

At the beginning of the 20th century, a loan and savings fund was founded in Ostryn, which was affiliated with the center in Vilna. The loans were granted with the guarantee of at least two guarantors, without encumbrance

[Page 314]

of assets. The board was elected for one year only. Yeshayahu Krinsky served as treasurer for many years. The work of the administration, including the treasury, was voluntary. With the withdrawal of the Russians, the fund was closed down. During the German occupation there was no savings or loan fund in the town.

When Polish rule was established, a People's Bank was re-established. The foundation capital was provided by the donations of the Ostryn residents who lived in the USA, as well as membership fees from the residents.

The bank operated in the house of Yosha Bar - on Vasilyshuk Street. The management was composed of Avraham Dreznin, Luninsky Yaakov and others. The chairman was Berl Pretzky.

The bookkeepers were Stritzky (Yehiel Brishansky, Yehezkel David Tkhornitzky).

According to the tradition of the loan and savings fund, and the People's Bank also held an annual meeting at which a financial report was presented and a new management was elected for one year only.

Gemilut Hasadim (Charity) Fund

In the attic of Hirschel Tzadok Abelov's house, a “Gemilut Hasadim Fund” was housed.

The managers of the fund were: Ben, the wood turner, and Fibel Yossal Ben Yitzhak, the tailor. This fund gave small loans to the needy who could not use on the People's Bank due to the lack of guarantors, their difficult financial situation and their inability to bear the burden of paying interest.

The loans from the Gemilut Hasadim Fund were given without any interest, and assisted the needy people in their time of need.

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

The battles passed over Ostryn in World War I. The Russian army retreated without a fight and the Germans entered the town. The Russian residents of the town deserted the place with the retreating Russian army. Jews with carts joined the retreat, but did not go far. The advancing German army blocked their way to Russia by the village of Brezice and around Novogrudok. After months of wandering, they returned to the town.

The Germans quickly and thoroughly took over the economic life. Everything was reduced within a legal framework. The population was given rations of bread, potatoes, yellow sugar and saccharine according to cards. Trade was almost at a standstill. The Germans also imposed a quota of milk with a fixed fat content on each and every cow. And woe to the one who added water to the milk.

All the men who were able to work were taken to labor camps, and children were also employed in light work. The work was mainly in the forests: cutting down trees and transporting them to Germany. The Jews were also employed in agricultural work on abandoned farms. Some of the crops were sent to the front, and some were stored in barns. The Russian Orthodox Church was turned into a barn. They imposed labor camps on horses to transport supplies to the front. Cart owners, who did not want to abandon their horses to foreign carters as horses were very important at that time, took the risk and transported the cargo to the front themselves.

Once the Germans recruited fifty young men to dig trenches by the Berezina, at the front. Anxiety accompanied them as they went to the front. After months of hard labor, they returned safely to the town.

[Page 315]

The Trade

Trading has been suspended. All the goods that were in the stores were registered and confiscated. Traffic stopped. To travel from place to place, a license was needed from the authorities. There were Jews who risked their lives and continued to trade secretly because the rations that were distributed by the authorities did not provide the minimum necessary for survival.

A Jewish Mayor

The German headquarters was housed in the spacious house of Hitchhik Dreznin. Almost all the large houses in the town were confiscated by the Germans for their own needs. In the early days of the occupation, the Germans maintained contact with the local Jewish population and appointed as mayor a Jew named Stotsky, a member of the Bond in the past from Ivrea, who had been active in the 1905 revolution.

During the German occupation, the mayor, a former Bond member, would appear in the synagogues and publicly speak about the rich culture and poetry of Germany, he praised the German people, from whom famous people such as Marx and Engels, Goethe, Schiller and Heine, etc., emerged.

Municipal Committee

A municipal committee of local businessmen was established to mediate between the German government, mainly the gendarmerie, and the Jewish population. This committee was headed by: Israel the butcher.

The committee dealt with all matters between the German authorities and the population. Relatively, the situation of the Jews of Ostryn was more comfortable than that of the Jews of the nearby towns. However, a significant part of the population suffered of hunger. They were forced to satisfy their hunger with biscuits that were given to animals.

The chaos of the war left many refugees in Ostryn. A special committee dealt with them.

Epidemics

Due to the poor nutrition, the immunity of the Jewish population was weakened. Following the war, epidemics of typhus, dysentery and Spanish flu broke out. Many died. Fear of epidemics fell upon the Germans and they began to take action. When an illness appeared in a single family, the house was disinfected with carbolic acid. The sick were taken to a quarantine camp.

The Germans also established a school for Jewish children. The language of instruction was German, of course! The principal was Keshchinevski and his wife was a teacher. Learning the German language became “fashionable”. The children of the “houseowners” began to memorize the German language.

In their reminiscences, the town elders would tell of the bitter fate that befell them during the German occupation in World War I: hunger, disease, destitution and more.

Compared to the Nazi hell, those days seem like heaven on earth.

[Page 316]

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

The Russian Revolution in 1917 and the German Revolution in 1918 heralded the end of the war which was soaked with blood and accompanied by suffering and hunger. Although the Germans still ruled Ostryn and its surroundings, it was clearly felt that the end of their rule was coming. Finally, the Germans left the town in 1919. They concentrated in Grodno. The town remained without a rule. In between, gangs of peasants appeared and began raids and robberies. Life became desolate. The Blochowitz gangs were rampant in the vicinity of Ostryn.

Jewish Police During these stormy days, the young people in the town, including discharged soldiers, gathered to consult what to do and decided to establish a Jewish police force in the area. They purchased several rifles and pistols from the retreating Germans.

|

|

The policemen - Ezra Meirov, Issachar Shapira, Shlomo Hirsch Szolkowski and Moshe Efron |

I still remember the scene of those days: a group of young Jews gathered in the market, led by the leader. He pulled out a gun and fired into the air. Everyone followed him in a hail of gunshot, so everyone will know that there is a rule in the town, and whoever violates it will be punished.

The Jewish police headquarters were in the house of Eliezer Pilowski. Rumors were rife that the Blochowitz gangs were preparing to attack the town and rob it. They would gather the children and women, the horses and cattle and smuggle them into the forest at night. Rabbi Tevshonsky led those heading into the forest. During the day, they would return to the town. And so, it went on for days. At night they left to the forest, and in the morning - to the town. In the end, the gangs glossed over Ostryn and the Jews in the town breathed a sigh of relief. [Page 317]

Farmers Are Preparing for Riots

A rumor spread that the surrounding farmers were preparing to invade the town and wreak havoc there. So, the town' s residents invited a group of German soldiers from Grodno to defend the place. When the soldiers arrived, they broke into Ahrchik Krinsky's restaurant and chased all the drunken farmers out. One German stood on the restaurant's veranda and aimed his rifle at the house of Yaakov, the “strosta”. A shot was fired. Screams and cries were heard, and it turned out that Yosef Lunyansky had been killed. The bullet penetrated through the veranda, hit him, and killed him.

The Germans returned to Grodno and the town was once again abandoned.

The Polish Legion

The Poles in the area began organizing a legion. The legionnaires' headquarters was in Shchuchyn. A group of legionnaires arrived in the town. They wanted to confiscate Notka Brill's horse. He resisted. Panic broke out and people began to gather next to his house. Shots were fired and the following were injured: Gedalia Borochowitz and the Polish officer. That evening another group of legionnaires arrived from Shchuchyn to avenge the injury of the Polish officer. They went from house to house and looted property.

In the morning, all the Jews were gathered in the market, they lined them up and sentenced every tenth to die. Seventy Jews were sentenced to death. At the last moment, the Polish nobleman Skabinski arrived in the town, and after much effort, he saved the Jews from death.

As a lesson for all to see, the legionnaires seized a Jew and publicly flogged him in the market. They burned down the house of Notka Brill, the source of the disaster. They arrested other Jews and took them to the headquarters in Shchuchyn.

Polish rule had not yet been established in the area, and the Russo-Polish War broke out.

During the Poles' retreat, three Polish horsemen broke into Rabbi Tevshonsky' s house and demanded money from him, otherwise they would set his house on fire.

The rabbi had no cash. The horsemen gathered bales of straw around the house to set it on fire. A few young men from the Jewish police appeared on the scene, fired into the air, and the “heroic horsemen” fled.

The Soviet Occupation

On their way to storm Warsaw in 1920, the Soviets captured Ostryn. A “Revolutionary Committee” and other Soviet institutions were immediately established. They confiscated the houses of the important houseowners in the town: Avraham Yellin, Eliezer Meir Filovsky, Khitchik Dreznin, and others.

Several young Jews collaborated with the Soviets. There were no property-owning “bourgeois” in Ostryn, but still, the houseowners in the town managed to get a taste of Soviet rule. Their apartments and shops were confiscated. The Soviets ruled Ostryn for four months.

After the defeat by Warsaw in 1920, the Soviets hastily withdrew from Ostryn. Polish rule became stable. Farmers returned to their homes, and life returned to its normal course.

During the Second World War

In 1939, on the eve of Yom Kippur, the Soviet army entered Ostryn. The Poles established a Polish Civil Guard before the retreat.

[Page 318]

The Poles had just left, and a mixed revolutionary youth group, composed of Jewish and Christian youth, attacked the Civil Guard, disarmed it and established a people's police in its place. This group included: Avraham Kazimir, Itchke Kravitz, David Shvedsky, Herzke Velitzky (Simeks), Pavel Makravitz, Pitke Troll, Kolka Slatvinsky and others.

The People's Police seized the post office, the police station, and the congregation, and set up guards in the town.

The leader was Pavel Makravitz and his deputy was Pinka Krinsky.

Meanwhile, a group of Polish soldiers returned to the town, arrested some members of the People's Police and planned to set the entire town on fire. Only rumors of the approach of the Red Army prevented them from carrying out their plan.

On the eve of the entry of the Red Army, the People's Police erected a gate of honor in their honor by the house of Chaya (Urs) Berzovsky. The entering Red Army was welcomed with flags and flowers, bread and salt. A temporary town' s committee was established. It was headed by Boris Gradzichik and its members were Yitzhak Hirsch, Itchke Kravitz, David Shvedsky, Herzke Simeks, Philip Olshko, Avraham Kazimir and Pinka Krinsky.

Local Soviet

Three months later, a local Soviet was elected, and the wheels of power were set in motion. The chairman of the Soviet was a man from the East. Its members were given various positions, and they were considered as the active party in the town. Ostryn was annexed to the Vasilyshuk district.

The small shops were eliminated on their own. The goods were sold and some were hidden. The large shops were nationalized. A cooperative store called “Salfo” was founded, where they sold: food, clothing, appliances, and more. Because of the shortage of various goods, constant lines were formed by the “Salfo” cooperative. A psychosis of hoarding took over the public. Upon learning that something was being sold at the “Salfo”, everyone lined up to buy it. It didn't matter what kind of commodity was being sold.

Workers, artisans, and the working intelligentsia integrated well into the Soviet regime. They were found jobs. Grocers and merchants lived in hardship. They were not cared for. They too went out to do simple physical work such as cutting down trees in the forests and the like.

In February-March 1940, members of the families of the great merchants were deported to Russia - the families of Yudel Rushkin and the forestry expert Nachman Tverkovsky. They were allowed to take all their belongings with them. At the time, this seemed like a disaster, but later it turned out to be for the best.

Education

When the Soviets entered the town, they closed the “Tarbut” school and opened a school in its place, the language of instruction of which was Yiddish. The children and the parents were fed with tales about the “Great Stalin” and composed songs in his honor.

The older youth received stipends from the authorities and continued their studies in large cities: Grodno and others.

The large Beit Midrash was confiscated, and a revolutionary club was housed there. In the small Beit Midrash, prayers continued without restrictions.

Cooperatives of shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, and the like were established. There was no shortage of work. New horizons opened up for the youth: courses, meetings, lectures. The future looked bright.

The attack of Nazi gangs on Soviet Russia put an end to everything.

[Page 319]

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

The town's craftsmen's workshops were located on the streets Vilna, Grodno, Vasilyshok, Tsychbi Street, and in the Alleys neighborhood. With diligence and faith, the craftsmen served the residents of Ostryn, the farmers and noblemen in the area.

Among the craftsmen were experts and “tandetniks”. Some of them had abundant livelihoods. Some of them had meager livelihoods.

Tailors

The famous sewing experts in the town were: Nahum Bernstein and Liba Glambotsky. The privileged houseowners of the town would order their clothes from them. And only from them. Also, the few Polish officials and the noblemen in the area would order clothes only from them. Of course, they were full of work, especially on the eves of the holidays Passover and Rosh Hashanah: the hum of the sewing machine would emanate from these workshops until late at night.

|

|

There were apprentices and trainees in these workshops. The apprentices did all kinds of works, but the trainees would work for years and years in the workshops doing various menial jobs, until they were allowed to work with scissors and iron. They worked and worked until they rose in rank and became apprentices.

The Confection Tailors

The confection tailors did not work according to orders. Instead, they prepared garments, and the poor of the town and the farmer in the surrounding areas bought ready-made clothes from them.

[Page 320]

Some farmers would bring their own fabrics for sewing. These tailors were experts in everything: jackets, vests, trousers, etc.

It goes without saying that the models were not according to the latest Parisian fashion. But these models satisfied the poor of the town and the farmers in the surrounding areas.

Sometimes the farmers would pay the tailors not in cash, but in the fruits of their agricultural produce: potatoes, buckwheat or wheat, or other seasonal products.

The Wayfarers

At the lowest level in this profession were the wayfarers tailors: they would leave the town on Sunday morning to the surrounding villages for the entire week, sometimes accompanied by their sons.

With a stick in their hand and a sewing machine on their back, they would wander in the surrounding villages. The poor farmers provided them with plenty of work: renovating old clothes and making various repairs. As kosher eaters, they would take with them their own utensils and food, so that they could taste hot stews during their stay in the homes of the Gentiles.

On Friday evening they would return to town loaded with agricultural products as a reward for their labor. The tall Israel Berezovsky stood out among the wayfarers. He was a tailor who loved his family and had children to take care of. He devoted his life to the education of his children. All week he was a “torn” from his family as he wandered among the clumsy farmers in order to provide livelihood to his family! But on Shabbat his spirit was alive, he would stay in the Beit Midrash even after prayer and mumble verses from the Psalms. Between Mincha and Ma'ariv he would sit down next to the wise Torah scholars who would compete among themselves in Halakhah issues, absorbing their words with thirst and falling asleep from exhaustion. And so on, week after week.

At dawn on Sunday, he would wander again in the surrounding villages.

Cobblers

Also, among the shoemakers there were experts and menders. They worked until late at night. Farmers who came to the shoemaker's house waited at his house until the repair was completed, as they usually did not have a second pair of shoes.

For some reason, the shoemaking profession was considered inferior. The shoemakers accepted this and they would mock themselves.

A shoemaker asked a Jew:

- Who is more important, the shoemaker or the seamstress?

- The seamstress! said the Jew.

- No! The shoemaker replied. The shoemaker's mercy surpasses that of the seamstress.

- Why?!

- It' s very simple: because seamstresses are dealing with shoemakers and the shoemakers deals with the house owners.

Carpenters

In fact, carpenters in the world are divided into building carpenters and furniture carpenters, which is not the case in the town of Ostryn. The carpenters in Ostryn were experts in both building and furniture. When does a Jew need furniture? Only once in his life, at the time of his wedding. And sometimes not even then. There was not a lot of construction in Ostryn,

[Page 321]

Therefore, they would go out to the surrounding villages and farms. Sometimes they would stay in the village all summer. In the village there was a construction: new houses, barns, cowsheds and stables.

Every wealthy farmer would bring a large chest into his house to store his property, as well as to store the dowry for his daughter, who had reached the age of marriage. The noblemen in the area kept the carpenters very busy. They would always add some kind of building to their farms.

A farmer who invited a carpenter to his home would take him to the village in his cart and return him to his home in the town every Sabbath evening. The profession of carpentry was respected among the farmers in the village, above all other professions.

Among the carpenters there were excellent experts. Real artists!

Itche Libka Kamionski was a real artist carpenter. In his youth he built the Holy Ark and the stage in the Beit Midrash in the town. A magnificent work of art. He would praise himself for this work all his life.

Blacksmiths

At the edges of the town, on street corners, were located the blacksmiths. The roar of the bellows and the sound of the heavy hammers hitting the anvils echoed throughout the area, long lines of farmers would be lined up at the blacksmiths. Before the busy agricultural seasons, each farmer would fix his tools. Here they would make plows and harrows, harness horses, attach iron hoops to a broken-down cart, and so on. Even though the craftsmen were not among the most privileged in the town, the blacksmiths were treated with respect. They felt as if the healthy nucleus of the Jewish race lay among the blacksmiths. The strong men in the town were the blacksmiths.

The Owners of the Carts

In the past, the Jewish “cart owners” were the rulers of the town. They were the only connections between the town and the big, distant world. Until the appearance of the cars in the world.

The owners of the carts were different from each other. Among them were privileged houseowners, with abundant livelihood, who sent their children to study in the big cities, and took “privileged” grooms for their daughters. And there were poor, destitute cart owners, who made their living with a dying horse that could barely carry the creaking cart, and when such a horse died, they needed money to buy a new horse of the same type.

The main occupation was: bringing the goods ordered by the grocers in the town from the wholesalers in Lida or Grodno. On their journey to the cities, they would transport passengers.

There were also cart owners who made a living by transporting passengers to and from the Rozhenka railway station (a distance of 28 km from the town).

On their journey to the cities, they would carry packages for the children of Ostryn who were studying outside the town. The journey was in a caravan. They were protective of their horses, which were their source of livelihood. On their return journey, loaded with goods from the city, they would usually walk next to the cart. In order not to burden the horses, when they traveled up the mountain, the passengers would also get off the cart and push the cart. If a cart sank in the mud of the roads on rainy days - the passengers would help the cart owners to get it out of the mud.

The mail carrier from the train station to the town was Moshe Yaakov Butrimovich. Although other people wanted this position, he would win in all the tenders and continue to transport the mail. Transporting the mail was considered a respectful role - almost as honorable as a government official. He transported in his mail cart to the station and back only important passengers.

[Page 322]

The First Trucks

In 1928, the good life of the cart owners came to an end. The first cars for passengers and freight appeared.

The competition was tough. The wealthy among them abandoned the struggle with the car and became its partners. Only the poor continued the struggle, the results of which were clear in advance. The cars expanded the routes of communication with the wider world. Butchers supplied meat to Warsaw, grain merchants supplied grains to Vilna, seeds and flax to Lida.

In the summer, the cars would deliver agricultural products to the picky summer vacationers in Drohiczyn, a distance of sixty kilometers from Ostryn.

Passenger traffic also increased, a short visit in Vilna or Grodno became a daily matter.

Tanners

At the edge of the town, not far from the Ostrinki stream, were located the workshops of the Pilewski brothers. The tanners worked in dampness and stench. For many weeks they would soak the leathers in special pools filled with water and oak bark, with the addition of acids and other extracts.

After soaking, the peeling process began. With sharp, curved knives, they would peel the hair and the remains of meat that remained stuck to them. Piles and piles of oak bark were piled up by the pools, and the smells of the rotting oak bark and the smells of the leathers would spread a stench throughout the area.

Brick Factory

By the town there was a brick factory owned by Christians. Its lessees and workers were only Jews. The brick factory manufactured bricks for building (mostly for building ovens and stoves, because the houses were mostly wooden buildings) clay pots and jugs.

The customers were Jews from the town and the surrounding farmers. The use of clay vessels was common among both Jews and farmers, unlike today.

Every few years they would lease the brick factory at a tender. The tender was held at the horse market and always on the market day, which was Monday of the week.

Jewish Farmers

The Jewish farmers added a special flavor to our town: the Brill, Michalewitz and Tuff families. These were the remnants of the Jewish agricultural settlement in the area since the days of Alexander I, the Tsar of Russia. Their fields were near the town and mixed with the fields of the “Gentiles”.

During the reigns of Alexander III and Nicholas II, the Tsars of Russia, they used various means of pressure against them in order to disinherit them from their land. However, the Jewish farmers were stubborn. They complied with all the decrees and did not surrender. They continued to cultivate their fields. The farmer Brill had an orchard of prime fruit trees. There were about four hundred trees in it. The YKA company, which fostered Jewish agriculture in the Diaspora, sent him an expert agronomist who instructed him in the care of the fruit trees using modern methods.

Butchers

The town's butchers were relatives. This profession passed from generation to generation. In the butcher shops, parents worked with their sons and their sons-in-law. Their strong wives also did men's work in the butcher shops.

Most of the butchers were honest and respectable people. The Jewish population, as well as the rabbi, had unwavering trust in them although kashrut matters were of high priority.

The source of animals for slaughter was the market. In honor of the holidays, butchers would go to great lengths to find a fine animal for slaughter, so that the Jews would enjoy on holidays. Buying was done at a butcher's shop, and only wealthy families were able to have meat delivered to their homes. When trucks appeared, butchers expanded their businesses and supplied meat to Warsaw, the capital. Wealthy houseowners would buy calves for self-slaughter. They sold the hides to tanneries, and so the cost of the meat was cheap.

The slaughterers lived in prosperity because of the extensive slaughter. They received from the butchers, in addition to the slaughter money, parts of the meat from each slaughtered animal: the entrails, the spleen, and more parts.

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

With the end of World War I, when Polish rule was established, soldiers that were released from German captivity or were in Soviet Russia began to return to the town. The returnees saw the big world, captivity and revolutions, other customs, a different way of life. They absorbed new worldviews and it was difficult for them to readjust to the life of the town. They agitated the public, and with the help of local businessmen, they began social and cultural action in different dimensions than was common at the time.

“Yakufu”

First of all, they started in the work of helping the needy. The Jewish community had been depleted during the war. With the help of “Yakufu” (which also received funds from the Joint), they began helping the needy.

A committee was elected, which dealt with the distribution of food rations, clothing, and the like. A soup kitchen was opened for the distribution of dishes, as well as two grocery stores: for the craftsmen and the houseowners.

Libraries

The first public library was opened with the help of the “Yakufu” at the end of World War I. Many books were brought to Ostryn from the “Yakufu” warehouses in Vilna, most of them were in Yiddish, and some were in Hebrew. The head of the library was Isaac Tuff.

Over time, many books were added to the library. The Classical literature in Yiddish and the literature that was translated from European languages. Books in the social sciences were also added: the writings of Borochov, Zhitlovsky, Medem, and more. The youth were immersed in reading. The library was the only source for acquiring knowledge and broadening horizons.

With the establishment of Polish rule, when life in the town returned to its normal course, the library expanded its purchases. Every new book that appeared, both original and translated, was immediately ordered by the library. The librarian, who also was responsible for the expansion of the library, was Mordechai Leizer Kaplan.

The library was located in Pina Bernstein's house. Three times a week, in the evenings of course,

[Page 324]

|

|

|

|

[Page 325]

they would exchange books. Each reader would pay a deposit and in addition pay a monthly fee. The library was helped by the drama circle, which would dedicate part of its income to the library. The library management would organize literary evenings and lectures on various topics. The library became a spiritual center for the educated youth of the town. The youth in Ostryn read and studied, and were famous in the area as educated and cultured youth.

Dramatic Circle

Dramatic circles existed continuously in Ostryn. The actors and directors were local people. The human composition of the circles would change: if the actress was married - her sister came in her place. If a director left the town, a replacement was immediately found for him, so the dramatic circle never ceased its operation.

The first drama circle was formed at the end of World War I. Its director was Zydka Dreznin. He was the director, the make-up artist and one of the main actors. When possible, he would play several roles in one play. He particularly excelled in comic characters. He was also talented in singing and dancing.

The rehearsals were lengthy. And only after many months of preparation would they present plays. The place for the plays was in the fire department hut.

On the evening of the performance, they would clear the hut of fire equipment, arrange seats for spectators on wooden stumps, or simply standing places by the walls. Later on, they bought the furniture of a cinema in Grodno who went bankrupt. Since then, spectators at the theater in Ostryn would sit like counts and experience the height of comfort and sophistication in the theater! There was no electricity in the town. The theater was lit with flashlights or ordinary lamps.

Every performance of the theater was a major event in the town. All the townspeople would flock to the theater performance. The repertoire in those days was composed of Goldfaden, Peretz Hirschbin, Y. Gordin and others. The “stars” in those days were: David Shklarovsky, Basha Shklarovsky and Tzippa Vigdorovich. In 1922, further progress occurred. The Polish Folk School (Pobshchenka) made its rooms available to the theater.

The shifts have changed. A new generation of “stars” has arisen. The director has also changed, and the teacher, David Shkarovsky, has taken over the management of the drama circle.

This teacher was very active in cultural matters in the town. While he was director, the plays “Miral'e Efrat”, “King Lear” and more were presented. The “stars” were Rokhka Tuff, Masha Luninsky and others. The whisperer was Avremel Efron. And again, there was a change of the “stars”. Yaakov Dreznin, Mifilov, Dina Shkalovsky, Mashka Gershovich, Leib Butrimovich and Pasha Valitsky, stood out in the plays. However, the director, David Shkalovsky, remained and hanged on.

The treasurer of the drama circle for many years was Mordechai Leizer Kaplan.

All the income from the plays was dedicated to institutions. There were institutions whose main budget came from funding from the drama circle. The “stars” were the public's favorites; at the end of a play, they would serve bonbonnieres to the best performers. The youth of the nearby towns were regular visitors to the plays in Ostryn because of the great publicity that the members of the circle received.

The Orchestra

The pride of the fire department in the town was about their orchestration. The members of the orchestra were only Jews. The first conductor of the orchestra was the Russian Orthodox pastor - Kokon. He was a graduate

[Page 326]

|

|

|

|

of the Conservatory of Music and was a gifted musician. He himself played the viola and never missed any opportunity for musical activity. Towards the Days of Awe, he would prepare the Beit Midrash choir for a public performance. Pastor Kokon's love for music was great, but his greatest love was for alcohol. He would often appear drunk. His assistant in the conduction of the orchestra was Shalom Brezovsky - the violin player.

Pastor Kokon and Shalom Brezovsky worked in the orchestra on a voluntary basis. After World War I, Leizer Kaplansky (the son of the Maggid) moved permanently to the town. Leizer was a graduate of the Conservatory in Vilna, played various instruments: piano, violin, bass, clarinet, cornet, and more. The Fire Department paid him a monthly salary - as a conductor. In addition, he was engaged in giving private lessons. He would add his outstanding students to the orchestra.

The main musicians were: L. Kaplansky (the conductor) – clarinet, Yekutiel Slochnik – cornet, Yoshke Traspolsky and Yoel Rubin - bass, Avigdor Vernikov and Leib Butrimovich - alto, Seidel Stanitzky, Yaakov Peretz Petushinsky and Ahrzeik Avroblansky - various instruments. Yodel Mashmovsky - drums, and Barka Vernikov - cymbals.

The orchestra would perform at all the official celebrations in the town, and sometimes at weddings as well. In addition, Leizer Kaplansky organized a string orchestra outside the Fire Department: violins, mandolins and guitars. This orchestra would perform in concerts before the public. During rehearsals, dozens of teenagers would gather behind the windows to listen to the sounds of music emanating from his small house. His talent for music was inherited by his sons. One of his sons studied at the Conservatory in Vilna. His son Motke was a private music teacher. The teenagers in the town, as well as the children of the noblemen in the surrounding areas, received private music lessons from him.

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

Echoes about what was happening in the global Zionist movement also reached Ostryn in various ways.

A newspaper in Hebrew, a partisan pamphlet, a passerby who spent the night in the town spoke with the town' s residents sowed the first seeds of the Zionist idea in the town. And this Zionist idea sprouted and flourished, because the ground was ripe for it. In 1917, after the Balfour Declaration, which inspired new hopes in the Jewish people, the first public Zionist assembly was held in the Great Beit Midrash.

It was a large and spectacular gathering. The main speaker was Chazkel David Tchornitzky. Hearts beat in unison, and they felt that salvation was near. During the German occupation - during World War I - Mr. Leibowitz, the cantor's son-in-law, organized the first Zionist group in the town.

Mr. Leibovitz devoted his free time to this group. He would read to the members of the group from various Zionist pamphlets as well as relevant pieces of literature. The action was managed in Yiddish. Leibovitz himself was a member of the “Tzeirei Zion”, but the group had a generally Zionist character. Later, Leib Leibovitz left the town and the group ceased to exist.

Israel National Fund

After the Balfour Declaration, a committee for the Israel National Fund was established in 1918. It was headed by: Zeidl

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Shchuchyn, Belarus

Shchuchyn, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 05 Nov 2025 by JH