|

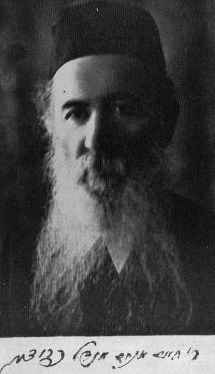

In handwriting, R'Hayim Menahem Medl Fridman

|

|

[Col. 473]

Rabbi Ahron Reuven Tsharni [Charney]

Bayonne, New Jersey

As a resident of Ratsk, I would often visit Suwalk. Whenever I needed some spiritual refreshment I would come to Suwalk.

[Col. 474]

It was a rare privilege to visit the famous scholar, R'Moshe Betsalel Luria; may his memory be blessed, who ordained me. There was a special spiritual flavour in Suwalk; a town full of wise men and scribes. Suwalk was like a mother who nurtured all the little villages in its vicinity.

Whenever there was a difficult litigation about a large sum of money, people would come to the rabbi of Suwalk.

Whenever a famous cantor, like Serota, would come to Suwalk, Jews from the surrounding towns

[Col. 475]

come to Suwalk to hear him sing.

If it was necessary to raise funds for a village institution, the Suwalk preacher, Rabbi Rappaport (now called the Bialystok city preacher: he lives in America) would be invited to speak.

If one wanted to raise a child to be a scholar, he would first be sent to the yeshiva in Suwalk, then to one of the great Lithuanian yeshivot.

Suwalk's merchants were also scholars. I knew one of them very well; that is, R'Hayim Mendl Fridman-scholar, wise man and maskil, communal worker and merchant. I lived in his house as a lodger and “kestkind”[1]

This is how it happened: After I was married in Ratzk, I became the Head of the Suwalk Yeshiva. R'Hayim Mendl Fridman, of blessed memory, invited me to lodge with him and eat my meals at his home.

The months I stayed with the Fridmans are like a radiant beacon in my memory. The home of R'Hayim Mendl Fridman and his worthy wife – the charitable Mere – was rich, not only in material things, but also in Torah, righteousness and enlightment.

On my first visit to his large wholesale food business, I saw how he related to his customers, the retail storekeepers. He wore a sheepskin jacket and a felt hat and looked like an ordinary person. But, when the store emptied out a bit, R'Hayim Mendl slipped into his house, took off his jacket, stood near the tile stove and began to discuss with great perception, the chapters of Gemara that I had lectured on. Then I knew that he was a sagacious scholar.

I could not believe that this was the same storekeeper I had seen one hour before.

Once people came running to tell us that the police had come to arrest the rabbi. His daughter was a Zionist and the

[Col. 476]

police had learned of her activities. The police raided her father's house where they found shekels[2] and other Zionist materials which the rabbi's daughter had hidden there. The police arrested the rabbi.

The punishment for such a crime was three weeks in jail or payment of a fine of one hundred rubbles. The police thought that the rabbi would pay the fine and the matter would end there. They were surprised when the rabbi put on his fur coat and his shtrayml[3] and said to them: “let's go!”

When we came to the street where the rabbi lived, it was packed with people. Many were crying. The rabbi's house was full of leading citizens of the town.

The rabbi stood there in his fur coat with his prayer shawl and phylacteries under his arm, ready to leave.

The householders said: “Rabbi, is it fitting that the rabbi of Suwalk should sit in jail?” He replied: “Well, let Suwalk be ashamed!”

The end was that R'Hayim Mendl and the other householders immediately paid the hundred rubble fine.

R'Hayim Mendl's house was like that of our father Abraham. The table was always set for guests. Every day yeshiva students ate there, urged on by Mrs. Mere Fridman, of blessed memory. No matter how busy she was in the store, when the yeshiva boys came, she would come into the house and encourage them: “Eat children so you'll have strength to study Torah”.

R'Hayim Mendl Fridman and his wife knew that their riches which God had given them, was not for themselves only, but that they had to care for those who had nothing. Suwalk and other such towns, was rich with people like R'Hayim Mendl and Mere. Such Jews were instrumental in the development of many towns and villages in Russia, Poland and Lithuania – full of Torah, wisdom, charity, piety and idealism.

Translator's Footnotes

Eliezer Perlshteyn

During my adolescence, I had a negative attitude towards the “upper crust” of my birthplace, Suwalk. Those rich men, merchants and scholars, of whom one was R'Barukh Roznberg. To me, the world of such men as Mordekhay Altshuler, Barukh Roznberg and Binyamin Mints, was completely foreign.

In those years, I did not even dream that fate would bring me into the company of one of the most important Jews who sat along the East Wall in the synagogue: - R'Barukh Roznberg – and that we would become close friends.

R'Barukh was a man of above-average height. His face was encircled by a round, greying beard, two bright eyes looked out of his thin spectacles. His whole bearing was aristocratic

The first thing that called my attention to R'Barukh was his “quarrel” with rabbi R' David Tevle Katsenelnboygn. On Sabbath and during the week, R'Barukh always came to morning prayers quite some time after they had begun. His place along the East wall was right near the rabbi's. Whenever R'Barukh approached, the rabbi would turn his head away. I could not understand such behaviour by a rabbi of the community towards a Torah scholar. R'Barukh became a mysterious person in my eyes.

R'Barukh's behaviour after prayers were over was also strange in my eyes. During the week, after prayers, member of the congregation would chat about business, the fair, news of the day, etc., while folding up their prayer shawls and putting their phylacteries away. R'Barukh never participated in these discussions but would go home without communicating with anybody. I was certain that this was not haughtiness on his part, because he did not have that smile of disdain that characterizes a haughty person. I doubted whether this man was even capable of smiling.

He was not sociable and he did not get along easily with people. I doubted whether he ever greeted anybody; much less do a favour for anyone.

[Col. 478]

These were my impressions of R'Barukh Roznberg when I was an adolescent.

When my father would mention R'Barukh Yehoshua Shakhna's, which is how R'Barukh Roznberg was known in town, he would always add the phrase: “the great scholar”.

When I grew older and came to pray and study in the Bet Hamidrash, I would hear the people who prayed and studied there also refer to his great scholarship. I did not know how he had earned such a reputation. Just because somebody came and studied Talmud by himself, did not prove that he was a great scholar. There were indeed great scholars in the community whose scholarship was manifested on various occasions. R'Mordekhay Altshuler, for example, was often invited to study with the Hevra Shas. He was also invited to the table opposite of Hevra Ein Yaakov. There was R'Hayim Medl Fridman from the Volozhin Yeshiva. I had seen his name quoted with honorifics in a book of Responsa by the Head of the Volozhin Yeshiva – the late R'Yosef Dov Solveitchik, of blessed memory. There was another Volozhin scholar in Suwalk, R'Shemuel Lizsheviski, (he had tested me before I was accepted into R'Hirsh Slonimer's yeshiva). The brothers, R'Avraham and Eliah Rozntal were famous for their scholarship. R'Avraham studied with the Hevra Shas. And there were others, but R'Barukh was always reserved and withdrawn, never showing his Torah knowledge.

On Passover eve, 1906, I knew that I would be leaving Suwalk forever in a few months. At that time, I began to study at the Bet Hamidrash every day. There, R'Barukh was the only one who came regularly to study Talmud, between noon and two o'clock in the afternoon. His way of studying was different from that of others. Not a word was heard, not even the generally accepted melody of Talmud study, only a monotonous nasal burbling.

Those two hours of his burbling tore at my eardrums and even more, at my nerves.

[Col. 479]

Even though we both studied in the same Bet Midrash, weeks went by when we did not meet. But one day, R'Barukh suddenly appeared at my side. He stood next to my lectern with a broad, hearty smile on his face; a smile such as I had never seen. He sat down and asked me in a fatherly fashion:” would you like to study together with me starting tomorrow?”

This question was so unexpected, I was simply dumb struck. I and R'Barukh! East and West! The great scholar and a poor Yeshiva boy! I finally recovered from the shock and replied: “R'Barukh, it would be a great privilege to be your student, but I am going to be here only for another two months. After that, I am going to America.”

“We can study together until then. You will not be my student but rather a study companion”.[1] He told me which tractate he was studying and with a smiling “Good day', he slowly walked away.

In a very short time I discovered that R'Barukh had earned the appellation: «great scholar» honestly. He was expert and sharp.[2] Even though we studied as companions, I never forgot the gap that existed between us.

One day, he invited me to lunch at his house. For various reasons, I was not eager to go, but it was hard to refuse, so I responded with a reluctant “yes”.

The table was already set when I arrived. It looked like a Sabbath table, lacking only candles and Sabbath loaves. The Roznberg children were already seated: the son, a university student, and the daughter, a dentist with her own office in Suwalk.

The new surroundings, the strange people, the wealth and comfort around me and, perhaps above all, the pretty young woman – all of this prevented me from enjoying the delicious meal. I finally breathed free when I shut the door behind me and hoped there would be no repetition of the event.

[Col. 480]

A few days later, R'Barukh said to me: “Khashele has been complaining that she's lonely. The children are away. Our daughter went to a dentists' conference and our son, to take some examinations. They won't be back until Friday, so she asked me to invite you for lunch for the next few days, until Friday”.

Again, embarrassed, I gave my unwilling assent.

After the meal I began to suspect that the story of their children's absence was not quite true. I quietly investigated the matter that same day, between afternoon and evening prayers. Stationing myself opposite Binyamin Mints' dry-goods shop, where Dr. Roznberg had her office on the second floor, I could see the lights there and Dr. Roznberg herself, drilling a patient's tooth.

It seems that R'Barukh and his wife understood that the reason for my discomfort at my first meal with them was the presence of their children. Therefore, they considered it proper to send their own children away because of me – a poor yeshiva boy. He probably realized that I was on a “Torah path diet; pat be-melah”.[3] so he gave up some of his family comforts in order to help me.

From that time I began to see R'Barukh in a different light.

When the time came to say goodbye to R'Barukh, along with his “for gezunt”[4], he placed a coin in my hand. I opened my first and saw a five rubble gold piece. When I protested that I had enough money to cover my expenses, he replied that he was not giving me the money or even lending it to me, but asking me to be agent and deliver the money to his son in New York. However, if I needed to, I could use the money during the journey. “One can never know what can happen on such a long trip”, he said.

His explanation was very refined. He did not embarrass anyone although; sending the “fiver”, by me was clearly a ruse. I again regretted my previous wrong estimation of R'Barukh Roznberg, whose true personality I learned to know only when he became my friend and teacher.

Only in America did I learn some details about his life, which I consider important to transmit. R'Barukh completed his studies at the Breslau Rabbinical Seminary. He held degrees as a chemist and lawyer. He was ordained by R'Shemuel Mohliver[5] and R'Yitshak Elhanan[6]. His wife was a granddaughter of R'Hayim Volozhiner[7].

Translator's Footnotes

Moshe Shlomi-Fridman, Haifa

My grandfather, R'Rafael Shelomoh Fridman. We mitnagdim do not, of course, have any rebes. We have no tsadikim [righteous men, another name for Hasidic leaders], and we are all a “holy people”. But, my grandfather, that slightly built man who, when he was over ninety, would go to pray three times a day, and on his way, would slip into a ready-to-wear clothing store and pick up a pair of pants or a kapote[1], bill to his son's account, and quietly carry it to the home of a poor man. He was like a saint.

One wintery day, when there was a dreadful frost, we grandchildren saw our grandfather barely moving along, shivering and shaking from the cold. We ran out to help him into his room. He took off his fur coat and…he was in his underwear.

“Grandpa, what happened?” “I'm warmer than “he” is. I have a fur coat, but “he” was so ragged, without even a kapote!”

The “he” was a beggar, a poor man without adequate clothing, and a man of my grandfather's character, could not pass by without giving him the clothing off his back.

Grandfather initiated the construction of the Habra Midrash kloyz, which stood near the bathhouse in the synagogue courtyard. He had a permanent place there. On Yom Kippur, he would pray standing from Kol Nidre;[2] until Yom Kippur was over. We, the young grandchildren, had the obligation of walking from the Bet Hamidrash were our father prayed and taking grandfather home. Notwithstanding his 26 hours of prayer, on his feet, and his advanced age, he would remain to sanctify the moon and even dance when he came to the words: «as I dance….”[3]

My brothers and I shared his room. I still remember how he would get up at night for “tikun hatsot”.[4] and how he cried over the destruction of Jerusalem, as he sat on a little bench and studied the Zohar[5], by light of a little candle.

The little candle, which dripped wax on his prayer book and Zohar, was a spark which shone before us all our lives. The weeping over the destruction and “Rahel mourning her children” brought us or almost all of

[Col. 482]

us, his grandchildren, to live in Erets Yisrael.

He died at the time of the German occupation during the First World War. My mother, Meri Fridman, of blessed memory, went around the ready-to-wear clothing shops, Miravski's, Reygrodski's and asked if her father-in-law had left any debts. Most of the shopkeepers refused payment, saying: “Allow us to participate in the mitzvah[6] of clothing the poor.”

There are very few people left of my grandfather's type.

My father, R'Menahem Mendl Fridman

|

|

| R'Menahem Medl Fridman

In handwriting, R'Hayim Menahem Medl Fridman |

[Col. 483]

He was a member of Hevra Shas. Every evening, he would sit in Bet Hamidrash at the big table and study a leaf of Gemara. Sometimes, he would quote a casuistry of the Volozhin Yeshiva, but mostly, he would study alone.

Once a year, this cold mitnaged would rejoice with everyone. That was on Simhat Torah, at the festive meal.

We would host the meal in our house. All the old Jews would come – the rabbi and the dayanim[7], the cantor and others. The rabbi would give a Torah lecture; others would show their skills in commentary and then drink “Lehayim”. The only two Hassidim in town; R'Hayim leyb Bakhrakh and R'Menahem Mendl, the monument maker, would sing Hasidic melodies and all the mitznagdim would chime in. In the other room, some people would dance in honour of Simhat Torah.

Who would imagine that all of these serious householders, who sat around every evening steeped in earnest study of difficult passages of the Talmud, would suddenly become young children and play, sing and dance?

My father was a warden of the Hevra Kadisha[8]. Hone, the chimney sweeper, who was an old member of the Hevra Mitaskim[9], would come regularly to see if there was a “piece of work.”

Hone always smelled of liquor[10].

Father was also president of the community council.

One winter day, a man came from the New Market and told him that the Russian Orthodox priest, who

live on May Third Street, was very sick and had no firewood in his house.

“A person is born in God's image”, said my father, and ordered a sleigh full of wood to be sent to the priest.

Yom Kippur eve, in my father's house, is engraved in my memory. On that day, proceeding the serious time of soul searching, my father would take out a big pack of papers and begin to reckon, write and count out money. He would call one of his sons over and give him some money to be sent to Erets Yisrael to pay the taxes laid on all properties by the council of Hadera. (For many years, my father owned a parcel of land in Hadera in partnership with Butkovski and Goldenberg).

The account taking and counting of money was all done with feelings of awe. These moments of father's “Erets Yisrael accounts” on Yom Kippur eve, brought us closer to the Land of Israel. When I actually

[Col. 484]

arrived there, I felt at home. When I saw the “diligence”:[11] I remembered the “diligence tax” which my father paid yearly. A watchman carrying a rifle in the colony[12]. We inherited our profound love for Erets Yisrael and our yearning to go there from our father and our grandfather.

She also had a “weakness” for charities. One of these was “hakhasat kalah”:[13]. When a poor girl was preparing for marriage, my mother would not rest until she had led the girl to the canopy. Often, when we children came home from heder or gym, we would not recognize our own home for the hustle and bustle: - strangers coming and going, bringing things; people underfoot – in one word, a great celebration. Mother is marrying off a poor girl.

Scores of women would come to see my mother; taker her aside and speak to her in an undertone. These women were part of a network called: “matan beseter”[14]. They sought and found families in need and whom they supported without anyone's knowledge.

In our family there was a division of labour. Mother kept busy with small shops and markets, while father was involved in wholesale. Yet, mother found time for this highest form of charity. She would disappear from the shop for a few hours and walk around the back streets, searching for and collecting “material” for her “secret” organization.

When they discovered a family in need, they would provide money or goods in the greatest secrecy. Quite often, a porter would be hired to deliver many baskets full of items to a family, and I would accompany him. We would know on the door, hand-over the packages, and leave. My mother admonished us: “No one must know the source of the gift”.

We did not always walk in our parents' path. They were disappointed, but they tried to bring us back to the right way, not with anger but with warm persuasive methods that worked a thousand times better than screaming and yelling.

When I was already a grown youth, I worked in the sawmill with my father's partners: Fridland,

[Col. 485]

Rubinshteyn, Kalietski, Rubintshik and others. My job was to measure the lumber which the gentiles brought in at dawn on their long sleighs. About nine or ten o'clock, I would come home for breakfast, but I would often “forget” my morning prayers.

Once, my mother came and said to me: “do you really think, my child that your father does not see

[Col. 486]

your neglect of prayers? He won't say anything to you, but I have heard him groan with anguish over your bad habits. Do you want to hurt him?”

Her reproach was so gentle, so humane, that I began to be more careful of not worrying my father.

Translator's Footnotes

Eliezer Perlshtyen

R'Mordekhay, the sexton of the Hevra Torah kloyz, was one of the unsung heroes of the world of scholars in Suwalk. His nickname was “Shveblemakher”:[1], because in his youth, at his birthplace Panemun on the Nieman River, he had a match factory. When he came to Suwalk, he brought his little factory along. Because of the danger of fire, his factory was situated far beyond the town's borders; near the road to Augustow. So did the elders of Suwalk relate.

|

|

| Eliezer Perlshteyn |

Mordekkhay the sexton was our neighbour in Leybl Bialostotski's courtyard, on the main highway. He

[Col. 486]

was then an old man, grandfather to half-grown grandchildren.

The actual upkeep of the Hevra Torah kloyz was not done by R'Mordekhay but by his helper – the assistant sexton, R'Shelomoh. He would clean out the candlesticks, put in fresh candles at the pulpit and on the tables where the householders studied, prepare the books for them, and so on. By the way, this was the only kloyz, as far as I can remember, that had an assistant sexton.

In contrast to the method followed by the Hevra Shas in the Bet Hamidrash, where they studied with companions, the members of the Hevra Torah studied individually. Quite often, however, if someone had a problem understanding one of the commentaries, he would come to his neighbour's lectern and discuss it with him. Such a discussion could lead to both “sides” coming to R'Mordekhay, who sat and studied his holy books all day, to lay their arguments before him. At such a time, R'Mordekhay would think a while, stroke his beard, and then quietly and calmly express his opinion. After such a discussion, both men would return to their seats with shining faces.

Since, as a boy, I was quite often present at such scenes, I understood that R'Mordekhay was a greater scholar than these householders, even though he was “only a sexton.”

R'Mordekhay was a small, thin man. A scrawny, not very long beard grew on his longish shrunken face, in harmony with his entire physiognomy.

[Col. 487]

In his dress and in his relationship with people, he was simplicity itself. He behaved as if he had been created to serve others. He never wore a brimmed hat; the outward sign of a Torah scholar, even on Sabbath or on holidays. He always wore a cap with a visor, like an ordinary Jew. The only change in honour of Sabbath and holidays was the he wore a better quality cap.

He had a special way of finding out who was in need of something for the Sabbath or some firewood in frosty weather. He saw to it that help was forthcoming with the least amount of embarrassment. If the person involved was a widow, his wife, Esther Elke, the Suwalk midwife, would take care of matters diplomatically. He would collect the means for these “secret charities” from members of his Hevra.

Once, while visiting a friend, I found R'Mordekhay chatting with a friend's father. When the latter left the room for a moment, R'Mordekhay quietly put some paper money under the tablecloth and calmly left the room.

[Col. 488]

Once a year, R'Mordekhay became a “different” person. That was on the day of Simhat Torah. He was simply unrecognizable then. He would get up on the table, at which he had sat and studied all year, dance and sing with devotion and enthusiasm: “Barukh elokeynu shebranu ikhvodo – ay – ay – ay…”[2], and when he came to the words: “venatan lanu Torat emet”[3], one could almost see his meagre flesh melt in the flame of his great joy at the beloved gift received on Mt.Sinai in ancient times.

R'Mordekhay and his wife and daughter left Suwalk in 1901 and joined their two sons, Efrayim and Yaakov Ish-Kishor[4] in London.

In 1908, R'Mordekhay came to America together with his family. They settled in Newark, New Jersey. In America he continued his study of Torah and doing good deeds until the last day of his life.

Translator's Footnotes

Yehudah Leyb Blekhman, Tel-Aviv

R'Hayim Koyfman was beloved by hundreds of Jews in Suwalk and the environs; merchants, storekeepers, communal works, pious men and also Christians.

R'Hayim became very wealthy as a purveyor of provisions to the Russian army in the province of Suwalk and its capitol.

In 1900, he took on the first great commission for providing for over three thousand construction workers who were employed at the military barracks on Saini and Augustow roads. As time went by, he became the chief purveyor for the entire garrison stationed in Suwalk. For many years, he was chief purveyor

[Col. 488]

for the Polish militia in town. But, with the rise of anti-Semitism in Poland in 1938, a Pole was put in his place.

In 1909, there was almost a famine in Suwalk and the environs. It was so bad that the animals were fed straw from the roofs. There were no potatoes to sow[1], so the governor himself turned to R'Hayim Koyfman for help. During a period of seven or eight weeks, R'Hayim brought in 930 wagonloads of potatoes and other vegetables and thus relieved the food crisis. For this act, the local government gave him an award.

At the time of World War I, R'Hayim had to provide food and products for the Russian soldiers. He arranged for some tens of Jewish soldiers to feed the animals. They ate at his table and he treated them as if

[Col. 489]

they were his own children.

Who does not remember the Hevra Medrash kloyz in the synagogue courtyard near the bathhouse? Before R'Hayim became the warden, it was small, neglected and the walls were blackened. R'Hayim had it built over, enlarged and added a woman's section, and paid over 90% of the cost. They used to say that he donated about 5000 zlotys for this purpose. He hired the director of the Suwalk Tarbuth school; A.Dubrovski, to teach there. He was a good preacher and had a good European education. After his death, he was replaced by a young man, a great Torah scholar, Rabbi Yaakov Skopski from Filipowe, who attracted many listeners. R'Hayim

was a devoted worker for the Bikur Holim ve-Linat haTsedek and gave to it generously.

If a Jew was put into jail, R'Hayim observed the commandment of “redeeming the imprisoned”. Once, six Jews from Grodno were brought to the jail. R'Hayim went to the chief and persuaded him to allow them to come to town during the daytime and return to jail to sleep. They were supposed to be working in town, but they actually

[Col. 490]

spent the day in Shaul Sukhavalski's fruit garden, “working hard” at tasting the variety of delicious fruits.

After the death of H.Gipshteyn, who left young children without any means of sustenance, R'Hayim's wife, Krashl, had pity on them and supported them and gave then an education, just as though they were her own. When the oldest, Yehoshua, (now a rabbi in Israel) complete the Talmud Torah, she sent him in yeshiva to study and supported him there.

In 1935, when the “yeshiva ketanah” was founded in Suwalk, headed by Rabbi Yaskov Skopski', R'Hayim took the yeshiva into the Hevra Medrash kloyz. Many of the yeshiva boys ate at his house.

R'Hayim and his wife Krashl, supported all of the charitable institutions in town, yeshivot and Torah institutions; helped needy individuals, donated large sums to the Erets Yisrael funds such as the Keren Kayemet and the Keren Hayesod.

His wife Krashl, died in Suwalk on the seventh of Tevet [5]698[1938]. R'Hayim participated in the fate of the millions of Jews in Poland. After much suffering, he died in the Slonim ghetto on the 28th of Nisan, [5]701[1941] of hunger. May his memory be for a blessing.

Translator's Footnote

(Memories of a former student of the Suwalk Talmud Torah)

During my entire course of studies in the Talmud Torah, from elementary classes with R'Yisrael Igelski, to the highest class, R'Avraham Shemuel Lizshevski was the head educator.[1]R'Avraham Shemuel was active in other areas as well; He was a member of the Community Council, member of the merchant's society, in the cooperative peoples' bank and on the board of directors of a whole range of religious and social institutions. But for us, the students of the Talmud Torah, he was always our educator and counsellor. He used to come to examine the boys at the end of the year and also lecture on various occasions. The most important householders in town were involved in working for the Talmud Torah, but R'Avraham Shemuel breathed life

[Col. 490]

into it. His special duty was to concern himself with the finances of the Talmud Torah, as well as all aspects of it – how every student behaved and studied. The children were used to seeing him in this light. Once, some of the younger children had difficulties in fasting, on a fast day. They told R'Avraham Shemuel about it. He answered: “Eat like gentiles, but study like Jews”. This response had a great psychological effect on the children and they always remembered it.

R'Avraham Shemuel Lizshevski was once himself a student in the Talmud Torah. His parents were

[Col. 491]

poor, and he had to “eat days” at the homes of various householders in town.

Afterwards, he travelled to Volozhin and studied in the yeshiva. He distinguished himself with his diligence. After his marriage, he kept a grocery store in his home. Even though such a business took one's entire day, his will was so strong that he found time for everything. He worried about the poor and in wintertime, gave them wood and warm clothing.[2] For many years, he served as a warden in the distribution of charity funds from America. In addition to all his studies, he also studied a daily leaf of Gemara in Zilberblat's kloyz. He attracted a large crowd with his unusual way of explaining the subject and he involved his listeners with his special method of studying.

[Col. 492]

The Suwalk rabbi, R'Aharon Baksht, valued his scholarship very highly, and when R'Avraham Shemuel was getting ready to go to America, he said with wonder and sorrow: “Ah! a Shas![3] is leaving us!” He was chosen to participate in a committee, along with R'Naftali Fridlender and R'Shemuel Gutman, to go to Siemiatycze to bring the rabbi of that town to Suwalk as its chief rabbi. Upon their recommendation, the rabbi of Siemiatycze, Rabbi Yosef Yoselevitsh, was chosen for the position.

He did not carry out his plan to go to America. He, and his wife, were fated to perish along with the other Suwalk martyrs in Lukov, where they were deported by the Nazis. May God avenge their blood.

Translator's Footnotes

To “eat days”: boys who did not have money to buy food would be farmed out to various families to eat there on different days of the week. It was quite common to have only five days in the week when one ate. Return

Havah Gladshteyn

His house was open for the poor and the sick. He had consolation and help for everyone.

R'Aharon Seynenski[1] did not rest until the last Jewish soldier in the Suwalk garrison was released and had a place to eat on the holidays.

Poor children in the Talmud Torah had shoes and clothing provided for them by R'Aharon.

[Col. 492]

If a poor Jewish woman came crying that there was a sick person in her family, R'Aharon would give her a note for free medical care and medicine.

One of his chief good deeds was to care for poor brides and widows. He was a “matchmaker” for quite a few poor Jewish girls.

He was a beautiful Jew; one of many such in Suwalk, where are they, where?

Translator's Footnote

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Suwałki, Poland

Suwałki, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 17 Aug 2013 by LA