|

|

|

[Page 188]

53°10' 72°20'

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

| Grozov – a small town; population 211. The town received “permission” (to exist) in 1693. There were two monasteries, Nikolski and Johann Bogoslavski, 2 Orthodox Churches, one Catholic Church, a Jewish prayer house, one synagogue, 11 shops and one beer factory. |

| From the Brookhouse–Efron Encyclopedia |

| Hrozava. On Saturday, 5 Iyar a fire broke out and burned the entire town, rendering it a heap of ruins. The synagogues and the holy books, except the Torah Scrolls, were burned. Almost all residents remained naked and hungry; we hope that our brothers the Jews will feel pity and help this burned town.

The writer with a broken heart, Eliyahu Yona Kitayewitz. To Rabbi Epstein, address: Hrozava, Minsk District. |

| Hatzefira, 18, 1881. 18 Iyar 5641 |

by S. Alexandroni

The town of my childhood, small as the palm of one's hand, was located on a wide area – on one side mountains and on the other side a swamp. Next to it was a narrow rivulet flowing from the mountain and being swallowed by one of the Niemen tributaries.

The story of the beginnings of the town is not very clear. According to one opinion, a Polish nobleman in the 16th century thought that it was important to establish an urban center for the estate owners and the villagers. He allotted a certain area from his estate Grozobok, divided it into plots, built houses on 4 streets and rented them to Jews, who owned inns and pubs in the villages. They populated the houses with young couples who established families. The town was named Hrozov (Hrozava).

The Jews of the town were called by the name of the village they had come from: the Balawitz people, the Baslutzi people and so on. The last of the Polish rulers in the area was named Lagouda. I remember when he died and was buried on the top of the mountain. After his death the estate became the property of Kriyakov, a high ranking officer.

A few Christian families settled in town as well. A Pravoslav church was built in the Central Square of the town; it had gold plated bell towers and was surrounded by a tall and wide stone fence.

Near the church, a number of shops were built for the Jewish settlers, as well as a Bet Midrash [house of study and prayer] and a “cold synagogue” for the summer. In my childhood days this synagogue did not exist anymore, since it had been burned during one of the fires and was not rebuilt. During the year (summer and winter) the Bet Midrash contained all the Jewish residents of the town. Only during the “Days of Awe” (Rosh Hashana [New–Year] and Yom Kippur [the Day of Atonement]), when the Jews from the nearby villages came with their families to pray, was the synagogue really full. Among the village guests who came to pray on these days, I remember in particular the famous Hirshel Verbiaver (the miracle–worker R'Zvi–Hirsh Wiener), who was remarkable with his tall stature and beautiful looks.

The Jews opened shops where they sold various things; they had a 'market day' every week and several fairs during the year. Commerce bloomed in town. The peasants would sell the produce of their land and buy in the shops their necessary things, according to their needs. Soon many craftsmen also settled in town, and had an honorable sustenance. Most of the craftsmen were Jews, but there were a few Christians as well. The Christians cultivated mostly fruit orchards, for which the type of local soil was favorable. Sometimes the Jews would rent an orchard from the Christian owner and cultivate it.

The town was situated far from important crossroads and from the main roads, and most of the residents had not seen a railroad all their lives. Since Slutsk was also far from a railroad station, big covered wagons would pass through town every Sunday afternoon on the dirt road, on their way from Slutsk to Minsk, carrying produce to the main city of the district. Such wagons would go also from Hrozava to Minsk, carrying goods and passengers. On Fridays they would return from Minsk with passengers and goods needed in town.

Many families in town were called by the names of their first grandmother in the family: they were “the sons of” Riva, Khiyuta or Rusha. These have been, apparently, exceptional women, who had built the town. Rusha (I am one of her descendants) was probably a very courageous woman: all her sons had the fingers of their right hands cut off. The story was that she had done it herself while they were babies, in order to avoid their recruiting to the army, the fate of the poor. The sons of the wealthy and respected Riva and Khiyuta were released from army service by other means – bribes or dividing the family into small units and registering each son as an only child.

[Page 189]

|

|

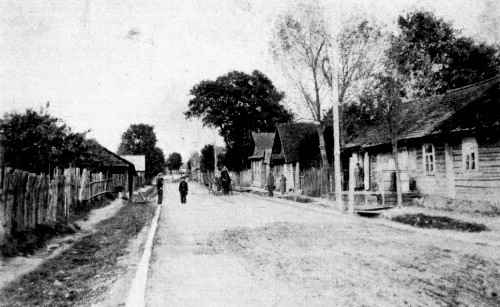

| A street in Hrozava |

By the way: any person whose surname is Grozovski (or Rozovski, for the purpose of camouflaging the name) is probably a descendant of a family from Hrozava.

The first ancestor of the Grozovski family, Feivel Hrozover, was a great scholar, All the Grozovski's and Rozovski's, from the Diaspora and Eretz Israel, stem from him. In my memory, this surname is connected to my first years of secular education. As I was visiting often the home of Fruma Horowitz, sister of the well–known linguist and writer Yehuda Grozovski (Gur), I found there a treasure of “enlightenment” books: a complete series of “Hashakhar” by Smolenskin, poems by Yehuda Leib Gordon and more.

When I was ten years old, I had already completed my studies of the Bible and the Talmud, with the greatest Melamed in town R'Beril Chaim Grozovski, and for the winter I was sent to study in the Slutsk Yeshiva, my sustenance coming from “eating days;” only the autumn vacation I spent in my parents' home in our town. The above–mentioned books – which were hidden from sight and I discovered only with the help of my friend, member of the family – produced the crisis in my spirit. After reading “The Crucible of Affliction” (Robinson Crusoe) and “The Love of Zion” I read all the pamphlets of Hashakhar and Smolenskin's novels, and even the writings of Spinoza. All these books were my companions day and night – at home as well as at the Bet Midrash, on top of the pages of the Talmud…

Livelihoods in Hrozava

Almost every home was a tiny farm. In the courtyard one could see chicken, which, during the cold winter days were walking inside the house and for the night were gathered in a place near the stove. In the summer they were warming the eggs under the bed, to the joy of the children when the little chicks were seen. Most of the chicks were sold, helping the sustenance of the family. There was one cow – part of the milk was used at home and part was made into butter and various cheeses, for sale. Sometimes all the milk was sold and the children drank only leftovers.

In back of the cow shed there was a large vegetable garden, providing for the family potatoes and other vegetables, but mainly cucumbers, which, during the summer market days were sold in masses to the farmers in the neighboring villages. Many of the Jews in town had a cart and horse and were visiting the houses of the peasants in the village and sell them haberdashery, in exchange for much needed food, produce of the village: eggs, chicken, grains, flax seeds etc. All this merchandise was then sold to the wholesale merchants and to the salesmen who went every week to Minsk.

There were many bakers in town. They would bake special cakes and sell them to the people who came to the church on Sundays and Christian Holidays. In their own villages they ate only meager food and white bread was considered Heavenly food.

[Page 190]

The Jewish families would bake regular bread for weekdays and special bread for Shabat and Holidays. The craftsmen in town worked for the villagers, for the townspeople and for the wealthy farmers, and sometimes even for the estate owners.

Among the craftsmen it is worth mentioning Nachum the cobbler, a respected house–owner, whose place in the synagogue was at the honored Eastern wall. Every week he recited the Torah Portion during Shabat Minkha prayer [afternoon prayer] and on Mondays and Thursdays – it was his “right” for many years. He taught his children the profession of shoe making, after they completed their study in the Heder.

R'Shmuel the tailor served as cantor at the Morning Prayer [shaharit] of the High Holidays, Shabat and Holidays. At the time of my childhood, he was no more a tailor; he cultivated a special fruit orchard, but the title “tailor” remained. There were other tailors in town.

The “Sons of Arye” family were builders, butchers and cattle traders. They were strong men; the villagers feared them and did not dare rioting during the market days while drunk. Much was told about that family, but I shall keep the story short.

The wealthy people in town were mostly innkeepers, accommodating the estate–owners who had business in town, like negotiations with forest cutters, tax collectors and the like. The wholesale merchants in grain, flax, leather etc. were different from the others in town: they had large and beautiful houses and large warehouses and barns in their courtyards.

The wealthiest in town were the sons of Riva and Khayuta. The big inn in town belonged to Avreimel Riva's (R'Avraham Vigodski). There was another inn, a smaller one, owned by Ar;e the bartender (Are Khrinover). In his cellar he has many barrels of various wines, and he prepared also raisin wine as well as a drink made of honey and hops. His son was a big man, the fear of the peasants in the neighborhood and a soldier in the Russian Army. His story is told in Yiddish, in one of Zeide's articles.

The wholesale merchants in town were: Mechl Epstein (Mechl Chayute's) named after his mother–in–law; his fortune was estimated at hundreds of thousands of rubles, and even his sons did not know where he kept it.

The same Chayuta had a daughter, a “woman of valor,” who sold textiles. Her husband, R'Pesach Greenwald, who had come from Lithuania, was a great scholar. He was a handsome man, and died young. His picture, which hung on the wall of Mechl Epstein's living room, was painted by his childhood friend Feitel Schwarzbord. As a child of ten he excelled in painting landscapes and portraits; it was said that his mother was the sister of the well–known sculptor Antokolski.

Of the famous merchants in town I shall mention Leibel Shimon's, (Leib Segalowitz, of the Riva sons), who was the competitor of the aforementioned Mechl Epstein.

The town was surrounded on all sides by thick forests that covered large areas; this was the reason why famous forest businessmen, from far and near, resided in town. I remember the Poliak family. They were “enlightened” Jews and did not resemble the regular residents of the town. Forest traders lived in the neighboring villages as well. They were acquainted with the Polish noblemen, who became impoverished due to their wild life and had to sell their forests.

One day, a big argument about money erupted between the Poliak family and a Jew from a neighboring village. I don't remember who was the accuser and who was the accused, but the matter was quite complicated and the sum of money involved was tens of thousands of Rubles. The argument was brought before elected arbiters, religious judges from neighboring villages – Kapoli and Blyakhowitz – presided by the Hrozava Rabbi, R'Shimon Zvi Skokolski. These people were remarkable in their handsome appearance and their beautifully adorned prayer shawls. The children would look at them with respect and admiration. Such people were rarely found in a small village like ours.

When the verdict was issued, a new conflict arose, and R'Shimon Zvi was forced to leave the local Rabbinate.

The gabay of the synagogue, R'Shmarya the judge, was a great scholar, righteous and modest. He did not use his knowledge to make a living; his sustenance came from the labor of his hands, working day and night as a baker. Only during the period that they had no official rabbi, did the townspeople turn to him for advice and guidance, in matters of religious commandments as well as in matters of finance. When he passed away he was given a great honor – his coffin was placed in the synagogue in front of the Holy Ark, he was eulogized and then the entire town went to his funeral and accompanied him to the cemetery.

R'Shmuel Epstein was a son–in–law of the Arkowitz family. I remember him as a very old man, righteous and honest. As a child of 4 or 5 I often went with my grandfather to his house – as they had some business together – and he would hold me on his knees and play with me.

His son–in–law R' R'Shimon Zvi Skokolski was a great scholar and an ordained rabbi. He had a big business and was renting lakes for fishing, but later he became mixed up with unsuccessful business and lost his entire fortune. Anyway the old rabbi intended to leave his business and go to Eretz Israel and suggested that his son–in–law take his place. The “simple folk” in town agreed, since he was a smart and pleasant person and a good preacher, but the scholars, led by R'Pesach Grunwald and the judge R'Shmaryahu opposed this step. If the old rabbi wants to go to Eretz Israel they will not oppose him, but it should be announced that the rabbinic office was free and hold elections, as in other communities. But they did not win the argument. The old rabbi went indeed to Eretz Israel, but for an unknown reason he returned before reaching it and was rabbi of one of the little communities in the neighborhood, and his son–in–law served as the rabbi of the town for a period of about ten years.

The rabbi was loved by all for his wisdom and his pleasant ways, as was fitting a rabbi. Every day after the Morning Prayer [shakharit] he learned Talmud with a group of young recently married men

[Page 191]

who still lived with their in–laws, and he preached in the synagogue for the entire community on the Shabat before the Pesach Holiday [Shabat Hagadol] and the Shabat between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur .

As a result of a new conflict he was forced to leave the town and R'Chaim Fishel Epstein replaced him. R'Chaim Fishel was loved by the people, thanks to his heart–warming sermons, in spite of the opposition of the town's “respected” headed by R'Shemaryahu Shullman and the synagogue gabay, because he had once participated in an important Zionist Congress and in his youth he had published Zionist poems and songs. But the greater public won, after a difficult struggle.

Yet, as time passed, the young rabbi found it necessary to get closer to the wealthy and respected people in town, despite the opinion of the simple people.

And here is another thing that happened… One of the salesmen received from the merchants in town a considerable sum of money for merchandise that he was supposed to bring from Minsk. The money was stolen from his home, and one of the “folkspeople” was the suspect. The rabbi, in order to find out who was the thief, performed a ceremony of “excommunication” [herem]: he assembled the people in the synagogue, lit black candles, blew the shofar and declared the herem. This ceremony angered the people, and the women would later tell that the number of babies who died in infancy rose since then.

And yet another story: On the night of the Simchat Torah Holiday, a conflict occurred in the synagogue concerning who will be honored with the reading of the prayer “Ata Hor'eita”. The conflict ended in blows, broken benches and broken lamps. The prayer stopped, the festivity ended and the children were sad, and the rabbi had to look for a post in another place.

As he finally was accepted as rabbi in a town in Lithuania, he left. During WWI, he was deported with all Lithuanian Jews, reached Slutsk among the other refugees and was helped by R'Alter Maharshak z”l. Later he came to America and served as rabbi in the communities of St. Louis and Chicago, where he died.

The youth in Hrozava

There was a difference between the very talented young people and the “ordinary folk”. These would complete their education in the Heder at the age of Bar Mitzva and continue the occupation of their father: in the shop, in the workshop, with the horses on a wagon and so on, and the more gifted would go to a place where they could continue the Torah study. In most cases it was Slutsk, where several small Yeshivas existed. Some of the students stayed for a while and left as soon as the life of poverty, “eating days” and sleeping on a hard bench began to upset them; then they joined again the way–of–life of the small town.

The most talented went straight to the big Yeshivas, in Mir, Telz, Radin etc. Those who returned to the town worked mostly as apprentices in the workshops, but some, from “the better families,” chose another occupation, which was just then established in town: the easy and clean occupation of scribe [sofer STA”M] – writing Tefilin [phylacteries], mezuzot and Torah Scrolls. Every Jew needed mezuzot and Tefilin; a young man in town was making them and also teaching others. But later, another young man, from Slutsk, who was a certified scribe, married a woman from Hrozava and went to live there. He opened a business and exported his products to America; the scribe products of Hrozava (R'Chaim–Leib the Scribe, R'Hillel Nozik, R'Mordechai Yakov, R'Ben–Zion Shpilkin and others) were famous. The young man mentioned above rented a spacious apartment, placed in it long tables and taught young men how to write Torah Scrolls for export.

Finally these young men became tired of that work, for several reasons, among them the many religious rules and restrictions involved. Winds of change were already in the air; as the population grew and means of sustenance became scarce, the need to emigrate (to America) reached Hrozava as well. Many did, and some became rich there.

The Hrozava girls did not go to the Heder. Some of them learned privately to read the siddur [prayer book] and write in Yiddish. Those who came from poor families usually became cooks or maids in Slutsk and other towns.

In the time of my childhood, there was no doctor or certified pharmacist in town. The sanitary situation was very bad. The only person who knew something about giving medical aid was R'Avraham (Fikos) “the doctor.” He was a handsome man with a white long beard, and was helped by his wife. On the market day, his house was surrounded by villagers in carts and wagons, and he treated them for various ails and pains. He also gave vaccines against smallpox.

The death rate in town was high, in particular from tuberculosis. The doctor himself died of the disease.

The Secular Rule in Town

The only ruler in town was the “Urdanik” – he ruled in particular over the shop owners. If he was good at heart and also received a good bribe, he would inform the shop owners about the arrival in town of the “Revisor,” and they would take off the shelves all the restricted ware for which they had not obtained permission to sell. But if the “urdanik” was strict and the “revisor” came unannounced, their fate was bitter – they received fines and other punishments. I was told that in the days of the revolution in 1905, the urdanik was particularly cruel – his name was Kulak – and he was murdered; the murderer was not found.

The Jews of the town had a form of independent rule: residents elected (by secret elections) R'Chaim Zisel Krigstein as the “community elder” [Staroste].

[Page 192]

Avreim'l the Hasid

The Jews of Slutsk and surroundings were not Hasidim; only one of the Hrozava Jews was known by his loyalty to his ADMOR. Every year, before “The Days of Awe” he would leave his home and family, take his walking stick and walk to his Rabbi, to spend the Holy Days with him and his Hasidim.

The man was a Melamed of little children, loved by all his friends and acquaintances. He had joyful disposition and used to rejoice with the public on the Holiday. He wore his kapota wrong–side–out, held a broomstick in his hand and danced in the streets, children running after him.

His ”occupation” was to strengthen cooking pots with wire; on vacations, when he was not in the Heder, he would visit the villages and perform this task – which added a little to his meager income. He was very poor, but happy, and he brought happiness to his fellows as well.

The old Rabbi R'Shmuelki

He died in Hrozava in 5653 (1893). The same year died also the cantor and ritual slaughterer of the town, R'Naftali Rabinowitz.

I heard a joke about the two people mentioned above:

Once they both traveled on a sleigh from Slutsk to Hrozava. Once as they were on the road, the sleigh turned over and the cantor remained under it, his face down in the snow. The other passengers called for help. The cantor R'Shmuelki, whose wit was famous, silenced them, saying: hush, you know it is forbidden to talk when the cantor is repeating the prayer.”

R'Israel Perlman

In addition to R'Berl Chaim Grozovski, mentioned above, there were several other melamdim in town. Among them I would like to mention the Talmud teacher R'Israel Perlman, from the “Sons of Baruch” family. On Shabat and on the Holidays he would recite in the synagogue the Torah Portion and was one of the leaders of the Community; his opinions on public matters, as the election of a rabbi or slaughterer, were respected by all. When a conflict occurred, his voice resounded and he was listened to.

This was Hrozava in my days, about sixty years ago. The hand of fate, which hit the entire Jewish settlement, did not spare it. At the present, we do not have clear news about it.

One of the immigrants to Israel told us, that in 1946 a young man, who had been in the Soviet Army, visited Hrozava, looked for Jews and found only one Jewish woman, by the name of Wandrof. I think that she was one of the descendants of R'Shmuel the tailor.

May these lines serve as a memory to the Jewish town, the cradle of my childhood, which existed and is no more.

It happened once, that one hot summer day an old man visited our own. He was short, a little fat and good looking, and everyone said: a nice visitor came to town, Reb Nachum from Rozovi, let us go welcome him, and then say “good–bye!” All knew what “let us welcome him” meant. When Reb Nachum from Rozovi married off his youngest daughter and remained a widower at an old age, he agreed to make Aliya to Eretz Israel and die there. And since a man needs sustenance, even when he is old, and is also taking a wife, he needs money – so what would he do? Reb Nachum did what other Jews used to do. He went from town to town, said Hello and then Good–bye. And when one parts from his friends, he would usually receive a gift, mostly some money, especially when it became known that he was going to Eretz Israel. In time, it would become a regular custom, and people would use this method to make some livelihood. A person like that would be honored and invited for breakfast or supper, and when he left he would receive some money and food for the journey. Reb Nachum would promise that he would pray for them on the grave of Rabbi Meir Ba'al Hanes, and send them some of the soil of Eretz Israel.

One day, Reb Nachum went to “say good–bye” to the Jews of Kapoli. During summer nights, the Kapoli people used to eat supper in the moonlight, and when the moon was covered with clouds they ate at the light of a cheap candle. The meal did not take long, and right after the blessing after the food they would recite the prayer of “Shema before sleep” or take a short break and go for a walk under the sky. One summer night of a beautiful full moon, at the home of R'Chaim, the order of things changed: the table was beautifully set and candles were lit, as on a Shabat or Holiday. This change was made in honor of Reb Nachum from Rozovi. R'Chaim had invited him for supper, and they were sitting for a long time and had long discussions about the Western Wall and the Cave of Machpelah, the Mount of Olives, the tomb of our Mother Rachel and other holy graves and buildings in Eretz Israel, and conclude with sweet talks about dates and figs and pomegranates, grapes sand carobs. The people around the table felt as if they were eating all these sweet things and their eyes were shining with pleasure. Rabbi Nachum was a great talker –he talked and talked as if he had just come from those places and had seen everything with his own eyes. All listened with great respect and love, and deep in their hearts envied him for having been privileged to go there. Can one think of Eretz Israel and Jerusalem as simply words? On the surface, it is a land and a city: soil and dirt, stone and clay as in all other places. But it only looks like that – in reality it is something else entirely. And what is that “something else?” Not something that the mouth can describe, it is felt in the heart only. Strangers cannot understand this – only Jews can feel and understand.

From discussions on holy matters the people around the table went on to discuss worldly matters: Rabbi Nachum had traveled in the world and visited many Jewish homes; he would leave accompanied by a blessing and some charity; he heard and learned much in all the places he had visited.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Slutsk, Belarus

Slutsk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 5 Nov 2022 by LA