|

|

|

|

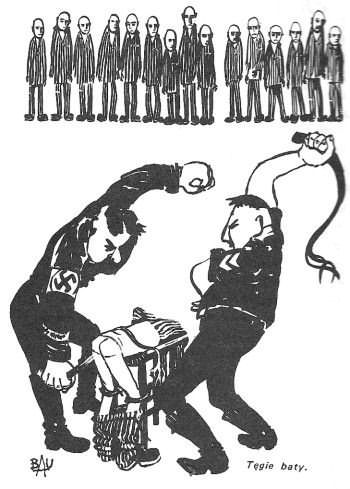

| SS guards whipping prisoner |

It is thus that Julius Madritsch opens his volume of memoirs, People in Distress. Madritsch was born on August 4, 1906, in Vienna, the center of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy of Franz-Joseph.[1]

A pacifist by nature, Madritsch was drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1940, but did his utmost to be discharged. Madritsch was against the Nazi racial policies which he had witnessed in the streets of Vienna. He saw his opportunity to escape the Wehrmacht when his organizational talents were recognized. He was invited by the war recruiting board to move to the Generalgovernment and become a purchasing agent for the Wehrmacht. He was subsequently appointed a Trust Administrator of two textile plants in Krakow.[2]

One of Madritsch's eager and ardent accomplices was Raimund Titsch, who was to become the lynch pin between many of the anti-Nazi conspirators in Krakow. The travelling manager for Madritsch, he visited Bochnia and Tarnow to ensure that their Jewish workers were cared for. He kept diaries and took photographs of the Nazi oppression, which were important evidence after the war.[3]

New edicts were being announced with monotonous regularity. Jews were only allowed to work in armament industries, and even this was to be short term. The Jews were to be replaced by Aryan workers shortly thereafter. It was this edict that brought together Schindler and Madritsch at a conference with the Judenrat labor office to discuss the implications.[4]

Unknown to both Madritsch and Schindler, another conference had taken place. This conference lasted only 90 minutes, but it was 90 minutes that sealed the fate of European Jewry. Reinhardt Heydrich, chief of the Gestapo, invited 15 high German officials representing various government departments to meet for lunch in a pleasant lakeside suburb of Berlin. What was to become known as the Wannsee Conference took place on January 20, 1942. Its purpose was to cordinate various problems related to the final solution of the Jewish question. Dr. Hans Frank had sent two representatives to the conference: Under-Secretary Dr. Bühler and Commanding Officer of the Security Police, SS -Standartenführer Dr Karl Schöngarth.[5]

By 1942, the drain on German manpower became so acute and the need for armaments so great that second thoughts had to be given to the wholesale slaughter of the Jews which was taking place. In February, Himmler presented to Hitler and to the newly appointed minister for armaments and munitions, Albert Speer, a proposal which would enable him to build armaments plants inside the concentration camps and put able-bodied inmates to work on armaments production. Propaganda Minister Goebbels recorded in his diary for March 27, 1942:

“The Jews in the Generalgovernment are now being evacuated eastward. The procedure is a pretty barbaric one as not much will remain of the Jews. On the whole it can be said that about 60% of them will have to be liquidated whereas only about 40% can be used for forced labour.”[6]

A new department was created, the Wirtschafts und Verwaltungshauptamt (Economic and Administrative Main Office), WVHA, to deal with economic problems of the Reich.[7] At the same time all the camp commanders were told that this employment must be in the true meaning of the word “exhaustive,” in order to obtain the greatest measure of performance.[8]

Himmler had an obsession about being fiddled with by his SS camp commanders. In response to a memorandum from General von Ginant, dated October 9, 1942, he points out in paragraph one: “I have issued instructions, however, that ruthless steps be taken against all those who consider they should oppose this move in the alleged interest of armament needs, but who in reality only seek to support the Jews and their own businesses.”

From around the beginning of 1942, the demand for manpower from any source was now over-whelming; No German company had to be coerced into taking labor. On the contrary, the firms had to use their influence and persuasion to get all the help possible. The private companies poured millions of marks into the coffers of the SS for the privilege of using camp prisoners. An elaborate accounting system was set up to be sure that the companies paid the SS for every hour of skilled or unskilled labor and that deductions for the food provided by the companies did not exceed the maximum allowed. The inmates, of course, received nothing. They remained under the control of the SS but under the immediate supervision of the companies that used them. The companies were required to see to it that adequate security arrangements, such as auxiliary guards and barbed wire enclosures, eliminated all possibility of escape. These new regulations, of course, were mainly directed at the Farbens, Krupps, and Siemens, etc. The likes of the Schindlers and Madritschs were insignificant by comparison but no less supervised by the SS

The effects of what had been decided at Wannsee were soon being felt in the Krakow Ghetto. The OD was being re-shaped, re-equipped with new style uniforms, and strengthened with collaborating Jews of the ghetto. One appointment was that of Simha Spira. He had been a glazier before the war, but was now the head of the Jewish police. Spira, a much despised individual, seemed to relish his close association with the Nazis. Spira took his orders not from the Judenrat but from Untersturmfuhrer Brand and the Gestapo.[9] Spira even organized his own political section, which was used with devastating effect to the advantage of the SS.[10]

|

|

| Jewish Police in the Krakow Ghetto 1942 |

In June and October 1942, the Nazis carried out the partial liquidation of the ghetto, which cannot be passed over without some detailed comment. During the last days of May 1942, the Ghetto was surrounded and sealed at night by a strong cordon of Sonderdienst (Special Police). The Gestapo and officials of the labor officer met in the building of the ZSS (Jewish Social Self-Help). A “selection” began. The Jews lined up, and a decision was made rapidly on who was to go and who was to remain in the Ghetto. Within two days the “selection” had been completed.

On the morning of June 2, 1942, the deportations started. From then on, a familiar scene in the ghetto was the sight of the Jewish policemen, led by SS stormtroopers, bringing the Jews from their homes to the gathering point in the Optima yard, and from there to the freight train station at Prokocim. The first to be expelled were the old people, women, and young children. Most of them were sent to Belzec and gassed, but hundreds were murdered on the way.[11]

The Germans were not satisfied with the number deported. They calculated that many who did not have stamps on their passes did not report. During the night of June 3-4, 1942, the Gestapo, and OD men made surprise raids into the ghetto: they inspected papers, stopped and searched in the streets, and entered hospitals, apartments, and houses. This time, several thousand Jews were marched to the Plac Zgody. The roundup was brutal and many of the Jews – the old, sick, and the children – were shot in the streets. This scene is vividly portrayed in the Spielberg film and the recollections of Tadeusz Pankiewicz.

The President of the Judenrat, Dr. Arter Ahron Rosenzweig, was summoned to Plac Zgody, where the SS dismissed him from his position. Rosenzweig and his family were immediately deported to Belzec. They did not survive.[12]

From his Pharmacy in Plac Zgody, Tadeusz Pankiewicz watched the partial liquidation of the ghetto. He gives an eye witness account of events on the evening of June 4, 1942:-

“By the following morning, seven thousand had been assembled. There they were kept throughout the hot summer morning, then driven to the railway station, and sent off to an unknown destination. The round-up was repeated the following day, the 6th June. The scorching sun was merciless; the heat makes for unbearable thirst, dries out the throats. The crowd was standing and sitting; all waiting, frozen with fright and uncertainty. Armed Germans arrived, shooting at random into the crowd. The deportees were driven out of the square, amid constant screaming of the Germans, mercilessly beating, kicking and shooting.”[13]

The Ghetto now had a new commissioner appointed by the Germans: David Gutter. Gutter was formerly a traveling salesman who sold magazines, but now he was the “supreme” in the Ghetto and behaved like a megalomaniac in the execution of his duties on behalf of the Germans. Gutter created a web of Jewish spies and informants within the ghetto.[14]

Both Schindler and Madritsch had met with the Judenrat in the Ghetto to discuss ways of relieving the employment situation. One of the solutions, thought up by Madritsch, was to employ more Jews per sewing machine, and to open up a further factory in the towns of Bochnia and Tarnow, thus giving hope to a further 2,000 Jews under the cover of essential armaments contracts. His first priority was to change the status of his factories to armaments factories, and thus receive the protection, like Schindler, of the Armament Inspectorate. The Madritsch enterprises in Krakow-Podgorze had a capacity of 300 sewing machines and about 800 workers, most of whom were Jews. His companies in Bochnia and Tarnow had a similar capacity. In Krakow, two shifts of Jewish workers marched daily from the ghetto to their workplace in the Madritsch and Schindler factories. For the time being, if the Jews held their work cards, they were safe.[15]

|

|

| Cyla Bau, wife of Josef: “passport to life” |

Shortly after the June deportations, a Kinderheim (children's home) was opened by order of the Germans. At the opening ceremonies, Gutter and Spira were present. It was quite an occasion: new lies, new swindles, again designed to discourage vigilance. Parents going to work could bring their children, up to the age of 14. Cared for by experienced personnel, the children would be busy with all kinds of tasks, such as sealing envelopes and weaving baskets. The Kinderheim was filled every day with scores of children who entered willingly and innocently. Just imagine that all this was done just for the few weeks before the pre-set date for the murder of all the children who attended the Kinderheim.[16]

According to Itzhak Stern, the killing of the children in the Kinderheim was the crucial incident that unsettled Schindler's mind. Schindler changed overnight and was never the same man again.[17]

At Emalia, production was continuing, but elsewhere in Krakow there was turmoil and panic. The seizure of Jews on the streets continued, and transports were leaving daily for the death camp Belzec. Mrs. Edith Kerner, who worked in the offices of Emalia, was beside herself, having seen 14 Emalia workers seized by the SS in the street and arbitrarily added to an annihilation transport leaving the ghetto for Prokocim railway station. Among those seized was Abraham Bankier, Schindler's trusted factory manager.[18] Spielberg gets this all wrong because he shows Stern as the person taken off the transport. I was disappointed with Spielberg's portrayal of this occurrence, as there are relatives of Abraham Bankier still living who must have been aghast at this inaccuracy. For me, the Spielberg film lost much historical accuracy, as a result.

Mrs. Kerner tried to contact Schindler at all his known haunts. After some hours, she managed to speak to him. Schindler drove directly to the railway station. He patrolled the platform, shouting for Bankier. The wagons had been in the sidings all day, the occupants sealed in with no food or water. The SS officer in charge relented under pressure from Schindler and released Bankier and the other workers from the transport with a receipt for their bodies. The Emalia workers had simply forgotten to go to the Jewish labor office to obtain their new blue work permits. Three of the 14 were Szulim Lesser (68938), Jerzy Reich (69010), and Bankier (69268).[19] In the three stages of the first June deportations from the Ghetto, 7,000 people were expelled. It was learned later that all the transports were routed to the extermination camp at Belzec. There were no survivors.[20]

To combat further seizures of this nature, both Schindler and Madritsch made use of their contacts with the SS, the Jewish labor office, and the ghetto police. Repeatedly, when receiving information that a roundup and transport were about to take place , they kept their workers at the factory, under some obscure pretext, so as not to expose them to the SS action squads.[21]

On October 28,1942, another 5,000 Jews were expelled from the ghetto, leaving 14,000 inside. In December 1942, the Germans ordered the ghetto to be divided up into two parts: Ghetto 1 for the working Jews and Ghetto 2 for the unemployed. At the same time, scores of Jewish settlements near Krakow were wiped out, and refugees who succeeded in escaping to Krakow enlarged the population of the ghetto. Also arriving daily were the labor units that were to work on the extension of Plaszow 1 labor camp.[22] The Bejski family, three boys and parents, were all transported to Belzec. By a quirk of fate, the Nazis wanted urgent labor for the building at Plaszow. The Bejski brothers were taken to Plaszow; but their parents were gassed in Belzec. The brothers – Moszek (69387) (the Judge), Urysz (69384), and Izrael (69385) – survived with Schindler. One lady who did not survive was Fransica Dortheimer, the mother of Viktor Dortheimer. To escape the turmoil in the city, Mrs. Dortheimer moved to the small town of Skawina thirty miles from Krakow. Fransica did not escape: In August 1942, a deportation train coming from Zakopane stopped at Skawina to pick up the Jews (including Fransica) who had been rounded up the previous night. The transport continued on via Krakow, Tarnow, and Bochnia to Belzec. There were no survivors.

|

|

|||

| Fransica and Viktor Dortheimer 1940 | ||||

The Armaments Inspectorate visited the Emalia factory and told Schindler that he was to switch production from enamelware to armaments. The alternative was closure. The factory was re-tooled to manufacture shell casings for bazookas.

Footnotes

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Schindler - Stepping-stone to Life

Schindler - Stepping-stone to Life

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 15 Aug 2007 by LA