|

|

|

[Page 74]

The Destruction of the Jewish Community of Rzeszow

by Dr. Asher Aleksander Heller

I completed my medical studies in Vienna. In the year 1930, I settled in Rzeszow where I obtained a post in the Polish Hospital as an ear, nose and throat specialist. When the War broke out in September, 1939, I also undertook to be the Director of the Jewish Hospital which had been set up a few years before the War with the aid of American Jews who came from Rzeszow. At that period, Hitlerite Germany and Poland had established close relations. Anti-Semitism had become widespread among the rulers. Rzeszow was a centre of military industry, and Poles who were brought there from the Posen District were all full of hatred for the Jews. The Jews were afraid to walk or pass through the Polish quarters and kept away from the Krakowska Street.

The Jews hoped that there would not be any war, but I was in despair, together with my friend Dr. Schlager, a highly cultured lawyer in our city and a student of Spinoza. The Poles were afraid of Hitler but were pleased because he was “solving the Jewish Problem”, and they would be finished with the Jews. Jewish intellectual circles played with the hope that it was impossible to imagine that the German rulers would exterminate 3.5million Jews, men, women and children. But when they arrest the wife of Dr. Chmelkes and she had to pay a million zloty as ransom, the indifferent, the well-to-do and the intellectuals began to speak in another fashion. “We are lost”, they all began to say.

Before the Germans entered Rzeszow, they bombed the armament factories. The astounded Poles argued that this must be a mistake! The bombing of the city caused many victims and the Jewish Hospital became full of wounded people. I did not wish to leave my patients, but under the orders from the Polish authorities, I left the city together with Polish physicians and we moved eastward. Everybody was dreadfully afraid. Tens of thousands ran away and filled all the roads. We reached Przemysl and found no Jews there, so we continued to Sambor. There I was awakened in the morning by the terrifying news that the Germans had come.

During the first two days, they left everybody alone. On the third day, they mobilised the Jews to clean the streets. The Rzeszow men asked me to go to the German Commandant and ask permission for the Reisha people to go back to their own city. “Better to clean the streets of Rzeszow than those of Sambor”, they argued. In their own city, they hoped they would be able to arrange matters with the rulers. The Commandant informed that we could return to Rzeszow without any permit, but that we had to go by the main road. I joined the group of Rzeszow men who went back. This was in September, 1939. We reached Przeworsk and there we got waggons to take us the rest of the way. Men belonging to the Todt Engineering and Labour units, ordered us to get out of the waggons; take off our clothes; hand over our razors and shaving blades and money. (They claimed that the Jews had killed a German officer with shaving blades). They shared our money out among Polish workers who were repairing the bridge. When we reached Rzeszow at last, we found the city under German military occupation with Swastika flags flying from all the public buildings. I did not return home but to the “Teppergessel” (Porter's Alley) in order to be in a Jewish Quarter. I let my wife know that I had come and she informed me that I could return to our home where two officers from Vienna had already taken up their quarters.

In the afternoon, I was visited by Gestapo men. I gave them my watch and they went away. German officers preferred to find quarters in the homes of well-to-do Jews, chiefly because they could speak German there. The Gestapo did not bother those families very much. But, a few days later, the

[Page 75]

Germans started to catch Jews for forced labour. In spite of this, the Jews began to go about their business for they hoped that the War would soon be over. There were rumours that British aeroplanes had been seen in the neighbourhood.

At the end of October, 1939, the Germans appointed Dr. Kleinman as Chairman of the Judenrat, and Dr. Benno Kahana as the Vice-Chairman. Dr. Kahana informed that I, together with our locally well-known Dr. Zinemann (the father of the famous Hollywood film producer, Fred Zinemann) must report to the Gestapo office. There we found many Jews already waiting. My turn came and I entered the room of the Kommissar. He ordered me to serve as Chief Physician and Director of Health Affairs to the Jewish Community, while Dr. Zinemann was appointed my assistant. I decided to avoid this and proceed to Przemysl which was in the Russian zone. At home, I said that I was going to Cracow. In the train I saw Tarnow Jews wearing a green Magen David. We left the train before reaching Przemysl and went on by waggon. On the way, we met Jews coming back from there who told us: “Merciful Jews, turn back and don't go on!” But we continued and reached the bridge over the River San, where tens of thousands of Jews and Poles were waiting. The Germans beat them and kicked them and cut Stars of David in the flesh of the Jews with knives. When we were on the bridge, a German officer ordered us to return because the Russians would not agree to accept us. We went back by train without tickets. At Jaroslaw, they began to drive the Jews out of the carriages, but my wife and I were fortunate and we stayed on the train. At the Rzeszow station, the Gestapo detained all the men. But since I was the Chief Physician, we were permitted to leave the station and return home. There we found three Gestapo men who welcomed my wife by yelling: “Judenschwein” and “Jewish sow”. I showed them the railway ticket to German Przemysl and they let us be.

In the morning, we were awaked by the bell ringing at the door. Gestapo men came in and wanted to confiscate the sofas. When I told them that a German officer lived there, they apologized and went away.

The Jewish Hospital of which I was Director, was requisitioned and turned over to the German army. I was required to look after the sanitary and health conditions of 16,000 Jews who were then living in Rzeszow. There was epidemic of dysentery in the town and the Germans accused me of not taking any steps to stop it. When the epidemic died down, they complained that I was hiding the fact. Until 1941, Jews were still admitted to the Polish hospital which was directed by Dr. Hinze, with Dr. Drobniecwicz as his assistant. They were both decent men who accepted Jewish patients without any special payment.

One cold day in December, 1939, thousands of Jews were brought to our town from Kalisch. They had been kidnapped from their homes and brought in their night-shirts and pyjamas. They were given quarters in the Synagogues and the Old barracks.

After the Jewish hospital had been requisitioned, I arranged an out-patient dispensary (ambulatory) in Mateiko Street and made use of the instruments and appliances of the doctors that had run away. When they took the city, the Germans had taken the woman dentist, Dr. Yeshower and the Judge, Dr. Kesler as hostages together with the opera singer, Horner. Afterwards, they released them for a ransom. In December, 1939, I received an order from the S.S. Police Commander in Cracow to examine all the Jews between 16 and 55 and see if they were fit for work. I was so frightened that I was confused and did something childish. I went to the District Officer and asked him innocently what work was meant in the Order? He asked me what I meant. I said I had received an order to check the physical conditions of the Jews, but it was hard for me to do this without x-ray apparatus. He fumed at me: “Do you want me to send your Jewish mob to be inspected in Berlin?” When I asked for permission to send special cases to the Polish hospital, he answered: “I have my responsibility and you have yours, and if I find you have done something wrong, I don't need to tell you how you'll finish up”. And he drove me out of his office.

So, I began to examine the health of the Rzeszow Jews. They were all ordered to register at the Labour Office, men and women alike, and I had to check their physical capacity. In doubtful cases, I asked permission to send them for radiological examination at the Municipal hospital. Usually, I received a negative reply. My companions examined and I signed. I was responsible for all the mistakes.

[Page 76]

|

|

|

| The last journey |

[Page 77]

Every Wednesday I submitted a report to the district officer.

On one occasion, I was away from home for a few days. When I came back, I found an S.S. Officer of the “Death's Head” regiment in my home. I found it proper to go in and tell him that should not make a mistake, that Dr. Alexander Heller was a Jew in spite of his German name. “It's all the fault of the Jewish government in Moscow”, he yelled. I asked him how he could say such a thing when he himself knew that that Polish Jewish refugees were running away from the Russian occupied area and returning to the German zone. And what was the logic in the Russian-German Treaty which meant that a Jewish government in Moscow was making an alliance with Hitler who wanted to exterminate the Jews?

The Germans changed the name of Rzeszow to “Reichshof”. The main Jewish Street had carried the name of King Kazimir since the days of the Austrians when the Polish Municipal Council had given the street the name of the King who had treated the Jews well. Now the Germans called it the Goethe Strasse. When the District Officer was asked whether it was impossible to find some more suitable street for the great German poet, he answered that it was a temporary name and the street would soon become the Ghetto Strasse. That was sarcastic and macabre German humour. He once said, when he felt humorous: “During the Spanish Civil War, two wounded Spaniards lay next to one another in hospital. One of them was a Red and the other was one of Franco's Fascists. The Communist said to the Fascist: “why do we need all this slaughter? We belong to the same race, the same country, why must we have all these thousands of victims and all this suffering and destruction? “You are quite right”, answered the Franco man. “All this calamity has come about because of the Jews”. “How is that?” asked the communist. “There aren't any Jews in Spain!” “That's the whole trouble!” answered the Fascist. “This dreadful mishap has come about among us just because there aren't any Jews here. They are to blame for if there were any Jews in Spain, we would be murdering them instead of you”.

The first expulsion began. In the corridor of my house, I saw a German police sergeant who was weeping and said: “ I have a father and a mother, a wife and children. How can we be so cruel to children The world will be right when they say that the Germans are a barbaric people”. But that was only during the early days.

In 1940, the Jews still lived in their own dwellings and could go on which their regular business. They chiefly suffered from house searches and from being kidnapped for forced labour. In 1941, Jews could still be admitted to the General Hospital.

I was afraid that Gestapo doctors and even Jews might denounce me. Once, ten girl students who were working on the road and were all swollen with sun-stroke, came to me. I gave them a certificate for three days' leave. Then, Pablu, a German from Vienna who was the new mayor, intervened and ordered the Polish physician, Dr. Maurer, to examine them again. Luckily, the Polish doctor confirmed my decision and gave them five days leave instead of the three that I had approved.

At the end of 1940, there was an epidemic of dysentery in town which had many victims. This was before the Ghetto was established. The Jews were afraid to go to the doctor. Dysentery cases were put out of their homes and sent to hospital, and their families also had to leave their dwelling which were disinfected. During the disinfection, all the household belongings were stolen. The Jews still valued their household belongings, because they did not know yet of the final solution that was waiting for them.

It was proposed to set up special huts for the patients in the village suburb of Pobitno. At the meeting which dealt with this proposal, those present included the District Officer, the Chief Army medical officer, the Mayor and I. They all sat around the table but I was not given a chair and had to stand during the meeting.

The proposal to transfer the Jews to Pobitno was made by the Polish Municipal Health Officer, Dr. Niec, a well-known anti-Semite and Nationalist, who changed his attitude for the better when he saw the cruelty of the Germans. I had concealed the epidemic as much as possible because we had no bacteriological institute to examine the cases. This was dangerous because German officers lived in the homes of wealthy Jews. The whole city was in a state of fear. The Jews were steadily maltreated. Day-after-day, they were kidnapped and sent to a labour camp at Postakow. The rich ones paid bribes and ransom money. The forced workers were

[Page 78]

|

|

[Page 79]

compelled to dig pits up to their necks, and German soldiers poured sewage and filth over them.

At the outbreak of the War, many Rzeszow men of military age had fled eastward according to the call of the Polish radio, and had chiefly concentrated at Lwow. When they learnt that the Jews of Rzeszow had not been closed off in a ghetto and were going about their affairs as usual, many began to return to the city, carrying permits which their relatives had sent them after obtaining these from the Gestapo in Rzeszow. The well-known lawyer, Dr. Braunfeld, returned to town with his son-in-law and daughter thanks to a permit of the German General Staff. He was registered at the Judenrat and executed on the same day. The reason was that the permit had not been issued by the Gestapo.

Dr. Elsner, a well-known physician in our town, died in Lwow in 1941. He wanted to come back to Rzeszow but was not permitted to. His daughter was a violin teacher and her husband worked at the “Kaiser Wilhelm Institute”. Both of them were permitted to leave for abroad. The day she left, she found her house full of flowers sent by the parents of her pupils.

The Judenrat was headed by Advocate Kleinman and the members were: Dr. Benno Kahana, Hirschhorn, Spiro, Landau. The Judenrat members collected the fines imposed on the Jews of the town and fixed the shares to be paid by each of the rich Jews. Those who refused were taken into a cellar and beaten until they paid their share.

The Jews were required to pay off all the arrears in rates and taxes which had accumulated during the 20 years of Polish rule, even for people who had gone abroad. The Germans gave the Judenrat four days for collecting the money. When 400 zloty were short, the Commandant ordered two Jewish policemen to arrest four members of the Judenrat who were shot, together with the policemen.

There were also heroes who did not submit. One young member of the Haiblum family to whom the Brick Factory belonged, was in contact with the Polish underground. In spite of the torture to which he was subjected, he gave nothing away to the Gestapo. They broke limb after limb, but he died in silence.

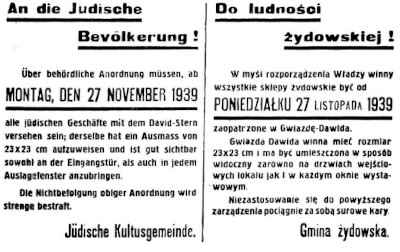

From time-to-time, Orders and Decrees were published against Jews. They were not permitted to walk slowly but had to walk fast. They might not walk in the 3rd of May Street or on Zamkowa (Palace) Street. When I once paused in the street while talking to a medical colleague, I was fined. Jews were not permitted to buy vegetables before 11 a.m.

The human tongue cannot describe the horror, the cunning and deceit, the cruelty and trickery of the Germans. Even before the Ghetto was set up, they proclaimed a curfew for Jews exclusively. No Jew might appear in the street after 7 p.m. Once, in December, 1939, a girl rang the bell at twelve midnight and called me for a confinement. I told her that as a Jew I was not permitted to go out without the permission of the Gestapo. About an hour later, the bell range again. The girl reappeared accompanied by a German Army Major who asked me why I was not coming to the patient. I answered him that there was a prohibition on the part of the Gestapo. “I shall give you a certificate”, answered the officer. He did not know that without the confirmation of the Gestapo, there was no value to any document. I trembled with fear as I went to the patient.

In 1940, every Jew was liable to forced labour. Those who were exempted had to pay the Judenrat in order that someone else might work in their place.

In 1941, it was already known that the Germans intended to put the Jews into a Ghetto which was about to be erected. From February, 1941, German regiments, trains with equipment and ammunition, passed through Rzeszow day and night, moving towards the East. The soldiers had a German marching song which went something like this:

The Jews are running to and fro

And down to the Red Sea they go.

The waves close over their head

The Jews are good and dead.

The world is quiet too,

One, two, three.

The Germans said that they were going to the Balkans. If anybody suggested that they were going to Russia, he was sent to Auschwitz.

On 21st June, 1941, a German Major of the Garrison Forces informed me that war had broken out with Russia. When I said that, with the way things were going and the German successes in the West, there were prospects that they would soon be in Moscow, he answered: “Wir siegen uns zu

[Page 80]

Tode”. (We are winning to death). “You may be a good doctor, but you are a bad strategist”. Meanwhile, the Jews were happy because they believed that Hitler would be too busy to have time to think about them, and meanwhile, he would break his neck.

The Price Inspector used to come and visit me even before the war against Russia began. I was silent while he spoke all the time. He told me that most of his acquaintances in Germany had been Jews. In peacetime, he had been a journalist and he felt ashamed to wear a German uniform. Once, he related, the University had sent him to Italy and Russia in order to study the influence of the Totalitarian system on education. In Russia, he had a conversation with Krupskaya, Lenin's widow. He had asked her about Lenin's relations with Trotsky, and she said that they had been friendly, although their opinions differed on party matters. Once when he came home, he found that his books were in disorder. They arrested him. Later, they put a Swastika on his suit and silenced him.

I remember that on one occasion, the Germans took the Jews out of the synagogue on the Day of Atonement – they were still allowed to pray at the New Year – and compelled them to sing: “What Ridz-Szmigly (the last Polish Chief of Staff) never managed to do, Adolf Hitler has done”. The Poles laughed and were happy at our misery. This was in the 3rd of May Street – the main street. Old German soldiers said to the Poles: “You are fools. You have lost your country and your freedom and now you laugh”. That made the Poles stop.

There were strange relations between the Germans with their various offices and departments. Once the Chief Commander, Field Marshal Von Brauchtisch, came to review the situation. Various representatives were invited to the reception in his honour, but not Dr. Ehaus, the District Officer. On that day, the Jews were not permitted to appear in the streets.

At about the same time, Dr. Ehaus began to demand the erection of the Ghetto, but the Military District Commandant deferred the matter. He lived with a Jewish family in the dwelling of Mrs. Gruenspann, née Schneeweiss, whose husband, a fur merchant, had fled from the city. When the Commandant went on leave, another officer took his place, strict orders arrived from the Government centre in Cracow to establish the Ghetto. The substitute Commandant also tried to defer the matter, but then Dr. Ehaus intervened and demanded that this decent officer should be removed from Rzeszow.

From June 1941, the Jews were ordered to vacate their dwellings for the German officers and move to the special streets of the Ghetto. Fences and walls were erected around the Ghetto and three entrances and gates were set up. One was in Mickjiewicz Street; a second in Galenzowsky Street and the Freedom Square Place Wolnasci; and the third in Kazimierz and Baldachowka Street. The Jews consoled themselves with the hopes that it would be easier for them in the Ghetto; they would be closed away and the Germans would leave them alone.

In December 1941, all the Jews left their dwellings and were shut off in the Ghetto, and at the end of December, 1941, the Ghetto was hermetically sealed. The Jews were ordered to wear a white ribbon on their sleeves. Anybody who left the Ghetto or went out without the ribbon was liable to the death sentence. The Ghetto might be left only on forced labour and only under the guard of Polish and German police and Jewish orderlies. Workshops were opened in the Ghetto for shoemaking, tailoring and upholstery. There were also working paces outside the Ghetto and everyone preferred them, for sometimes it was possible to buy food for the children on the way, such as eggs, cheese, etc. On the way to and from the Ghetto, nobody might leave the ranks. At the entry to the Ghetto, the Germans put up a big notice: Danger! Epidemic! And a picture of a skull. Entry was prohibited to soldiers.

But the Jewish hope of being left alone in the closed Ghetto proved wrong. Day-after-day, the Gestapo officials made their visits. When the Ghetto was established, the Jewish Clinic outside the Ghetto was closed, and the Judenrat was ordered to convert a private house into a hospital. So, we proceeded to the Ghetto area with our walking patients. At that time the District Officer, Dr. Ehaus, became ill and I was suggested to him as an experienced physician. Better die, he answered, “than be cured by a Jew”. To our regret, he became better. From time-to-time, he came to the gate of the Ghetto beside which the Hospital stood in order to check whether anybody was smuggling food. He used to raise the women's skirts and kick them

[Page 81]

|

|

[Page 82]

from behind. On one occasion, he called me and gave me, for the Hospital, the smuggled food he had confiscated from forced workers. There was an interesting incident. The wife of an officer who lived in my apartment slipped in the room and broke her nose. As a Jewish physician, I was not permitted to treat a German. I stopped the haemorrhage and told her that I could only treat her by permission of the District Officer. He refused to give permission and she had to go to the German Hospital in Cracow for treatment.

The congestion in the Ghetto was indescribable. Not every family managed to get a room to itself. They confiscated all the books including the books of the synagogues. The private books of the ordinary Jews and Hebrew scholars were taken to Nurenberg by way of Cracow.

The Jews of the neighbouring little towns were also brought into the Rzeszow Ghetto as well as the Kalish Jews who had been brought to Rzeszow in December, 1939. They were housed in the courtyard (Kloiz) of the Rimanov Hassidim, the Kloiz of Reb Asher Silber, who had been the Chairman of the Community Council. In the Ghetto there was neither a bath house nor soap.

A labour office under the German administration was opened in the Ghetto, and the General Card Index administration of the city transferred the cards of the Jews to the Ghetto. Everybody tried to evade exhausting work, and they all demanded health certificates from me.

One day in spring 1942, the Judenrat was ordered to the District Officer at 6a.m. The Ghetto was in a state of panic. The officer read them a letter by Heinrich Himmler, head of Reich Security, that all the Jews had to hand over their furs and fur collar pieces under pain of death. Even before the members of the Judenrat had returned to the Ghetto, Gestapo agents burst into the Ghetto furrier's place and shot him. They sent the good furs to Cracow and left the ordinary ones in the store where they rotted.

Children who saw the actions of the Gestapo wept. Their fate was a bitter one. They suffered from cold and hunger. They were shot before their mothers' eyes. When three-year-old children saw Gestapo men, they hid away in any hole until the danger passed.

Congestion in the Ghetto grew even worse for the Jews of Lanzut, Tyczyn, Kolbuszow, Glogow, Sokolow, Sendiszow and Czudec were all brought there. They lived three families in a room and I was sure that some pestilence would break out.

On 30th April, 1942, Gestapo men burst into the Ghetto claiming that they were looking for Communists. From the rooms, they chiefly took out observant Jews, took them down into the cellars, beat them to death and maltreated them cruelly. They then ordered the Judenrat to remove the bodies. I found terrible wounds on the corpses. We were stupefied and hopeless. Until then, we had not believed that the Germans were prepared to murder 3.5 million Polish Jews. We had supposed that they were only punishing those who broke their economic regulations. We had not been able to imagine that they just wanted to murder. Afterwards, as I have already mentioned, the Judenrat received orders to collect from Jews all state taxes and municipal rates which had accumulated during the previous 20 years. As they were not able to collect the entire sum, four Judenrat members were shot at once, including the intellectual Froelich who, just before the war, had been invited by Einstein to join him in America.

In July, 1942, Dr. Zinnemann and I were called to Dr. Ehaus, the District Officer and I received order to give him a list of physicians, nurses and midwives. He made a green or a red mark beside each name. In the list was the name of Dr. Schmelkes, an orthopaedist who belonged to a famous rabbinical family. We were afraid of being beaten and were very depressed, but meanwhile, nothing happened.

At the time, about 22,000 Jews lived in the Ghetto, including the residents of the small towns.

A few days later, the Judenrat was suddenly summoned to Dr. Ehaus, including Dr. Zinnemann and myself. We stood in the corridor and he came out to us accompanied by the heads of the Gestapo, the Police (Schupo) and the gendarmerie, and told us that the expulsion of the Jews of the Ghetto would begin the next day. The first to be taken would be those who did not work and needed help. Each one had to take his jewellery with him and food for two days. The Ghetto was divided into sectors and movement from one sector to another was prohibited on pain of death. The Jewish orderlies had to collect those who were to be expelled in the sector between the Baldachowka and Kopernik Street. The next day at 6 a.m. those who

[Page 83]

were to be expelled were already in place. After 6, the Gestapo combed out the sectors, searched through the houses and shot anybody they found there.

Orders had been given before that to return all the labour cards to the Gestapo. Factory workers received a stamp from the Gestapo and were exempt from the first expulsion. They and their families were left behind.

The District Officer issued an order that henceforth, Jewish patients were not to be sent to Hospital after 18hr. The whole building had to be emptied of patients. The next day, two S.S. men came to the hospital where they found a young woman, an American citizen, who suffered from tuberculosis. Her parents were imprisoned. The girl did not understand German and spoke only English. They asked her whether she wanted to join her parents in the prison. There she was shot together with her parents on that very day.

The other patients were ordered to dress within five minutes. One patient was paralysed. I burst out weeping aloud. The other physicians, my comrades, gave poison to their parents in order to spare them the torments of the Gestapo. The patients were placed on lorries and killed in the Glogow forests. As the Ghetto physician, I had to be present at the square to which the victims of the expulsion were brought. The first to be brought were the residents of the Old Age Home. Those who were sentenced to expulsion and brought to the Square had to practice jumping. Then they sat down each on his own bundle. They were not allowed to turn their heads. I saw how terrified they were, tears running from their eyes, and I had to give them first aid.

Some of these expelled were brought into rooms for physical inspection. There, two orderlies were waiting for me and reported that it was impossible to open the room of Dr. Yezhower, the dentist and her sister. A locksmith broke the door open and we found that the two of them had taken poison. Dr. Yezhower was already lifeless but her sister was still breathing. I gave a report to the Chief of Police and asked for permission to treat her and move her to the hospital. “No!” he yelled. “Let her die”. Others who took poison were Joshua Schneeweiss and his wife. He was a citizen of long standing who kept the Municipal Pawnshop.

The bags of the expelled were taken from them and loaded separately on the lorries. Some among us thought that consideration was being shown to their suffering and it was being made easy for them so that they should not have to drag their bags on the road. But the lorries with the bags were not sent off with the expelled people. They were taken to the railway stores.

At 12h noon, the whole convoy set out on foot, accompanied by S.S. units who had been mobilized from the surrounding towns. They went towards the Staroniwa railway station. On the way, an S.S. man beat a woman. Her husband attacked him. In response, the S.S. unit slaughtered about 250 people there. This was just opposite the new Post office. Young German girls worked in this building as clerks. When they saw this dreadful sight, many of them burst into tears and fainted. The girls were immediately returned to Germany.

This expulsion extended to about 4,000 Jews. The Judenrat was ordered to pay the cost of transport of the bags and the people. The Jews did not wish to pay. Then, the Judenrat used a trick. They promised that they would obtain the stamp of the Gestapo on labour cards, and that would exempt them from expulsion. They money was paid but the cards were not stamped and many were lost.

In order to bury the corpses next to the Post office, the Jews were ordered to dig pits in the graveyard and also to clean the dried blood from the pavement with their tongues.

120 persons instead of 40 were placed in each coach of the train. Women and children began to wail for water. Some Polish women brought water but the S.S. men drove them away with stocks. I returned to the Ghetto. It was not clear why they had dragged me along to serve as a doctor, for I was only permitted to fetch some Valerian drops and four bundles of bandages with me.

I remember an incident that was characteristic of the Hitler men. In the Square where the people had been gathered, a woman asked the Police Officer to take pity on her mother and transfer her to the Hospital. She also asked where the people were being taken. The answer was: “To the Kingdom of Heaven”.

The Neumann family were also there. Neumann's wife was a German from Berlin. Neumann approached the Gestapo men and said that his wife

[Page 84]

was an Aryan German. In reply, the Gestapo men beat him furiously and transferred her to the Aryan side. This noble woman returned to the Ghetto in order to suffer with her husband. She used to light candles on the Eve of Sabbath. Her brother was a high S.S. officer in Berlin and her uncle was the head of the Nazi Party's “Winterhilfe”.

Her husband was not expelled but was sent to prison and an order was received to transfer her and her children to the Aryan quarter. Afterwards, her husband was taken back together with her children, and she was ordered to leave Poland. She sent telegrams to her brother and her uncle. They came, grew very excited and yelled, but it did not help.

The members of the Jewish intellectual and University circles, were the first victims of Nazi cruelty. Lawyers were the first to be expelled to the Death camps. They were detained in the Ghetto until December, 1941, and were sent from there to the furnaces. I remember the advocates Dr. Salzmann, Dr. Lecker, Mrs. Duker-Both and Dr. Schlager, a philosopher and student of Spinoza. The old physicians, Dr. Herz, Dr. Kronfeldt and Dr. Zinnemann were sent to the gas chambers at Belzec.

Some of the Polish intellectuals expressed their horror at the German atrocities, but there were also some who rejoiced at heart because Hitler was solving the Jewish problem for them in a way that they themselves could never have done. But they were also afraid that their turn would come after the Jews. Even the Endeks (National Democratic Party members) who were notorious for their anti-Semitism, grew sick of the German rule and awaited a Russian victory. The Jews who survived, were saved chiefly by the Polish poor, and even by underworld families. The priests showed their sympathy to the Jews. The judges grieved for their Jewish friends in their hearts, and the President of the Court told me that he could not sleep at night because he could see the sufferings of the Jews in the Ghetto at all times. The peasants had no pity on us. There were some who took money and jewellery from Jews and afterwards handed them over to the Germans.

Mention should be made of other instances showing the lunatic German race hatred and their divided personalities. This was at the time of the first expulsion. Dr. Ehaus, the District Officer, saw a beautiful blonde Jewish girl in the expulsion square, and gave orders to take her out. He handed her over for anthropological examination in order to receive a certificate that she was of Aryan origin. He had her parents executed and took her into his home as a domestic help. When the German army collapsed, he fled to Vienna and took her with him. When Germany surrendered, Dr. Ehaus committed suicide. The young Jewess returned to Poland and married a Polish Colonel.

At the time of the first expulsion, the Gestapo men came to Mrs. Storch where they found a crippled boy who could not walk. The mother begged them to kill her and not him. They obliged her and then killed her son.

The 250 slain were buried beside the cemetery wall. The Gestapo Commissar came to inspect the spot and saw written on the wall the words: “Al Kiddush Hashem” (by martyrdom). He asked Lustmann of the Hevra Kedisha what was written and he answered that he did not know. The Commissar shot him and pushed his body into the common grave. The 250 martyrs included the Dayan, Reb Joseph Reich, who was known as “Der Roite Yossel” (Ginger Yossel). The inmates of the Old Age House were not taken to the station. They went without their bags, wearing only their prayer shawls and tefillin. They were sent directly to the GLogow Forest and were murdered there.

The S.S. Command was housed in the Zucker building in the Garncarska Street. On the day of the expulsion, one of the S.S. officers signalled that I should go up to his dwelling with him. Then, he beat his hands together and said: “My God, my God, what they are doing”.

The Jewish Hospital was now placed in the courtyard of the Rimanow Hassidim which had been founded by the former community Head, Reb Asher Silber. The resident physician there was Dr. Hauptmann, a Jew from Breslau. At the time of the first expulsion, the patients were loaded on barrows and brought to the concentration square. On the way, they all said their deathbed confession, for they knew that this was their last road.

The Judenrat was in the house of the Schiff brothers who were famous goldsmiths in this part of the world. The Schiff family met their end in Lwow. Singer, the seal-maker(, disguised himself as a Catholic priest in order to escape, but a Gestapo man recognised him, caught him and shot him on the spot.

[Page 85]

The last spark of hope died out in the Ghetto. Even the optimists now said: “We are the living dead”.

On the day of the first expulsion, Dr. Ehaus, the District Officer, left the city for several days. When he returned, he called on Dr. Benno Kahana to write a realistic report of what had happened and point out that it had taken place during his absence. He was a cruel anti-Semite. When he saw Jews wearing arm-bands in the street in 1940, he said: “I must see the city without Jews some time”.

All those expelled were taken to Belzec. In July, there was an interruption in the expulsions. These, the second, third and fourth, were not so bloody as the first expulsion in June, 1942. The Ghetto began to shrink.

The Jews had to vacate their dwellings in the Ghetto, street-after-street. The newly emptied streets were added to the Aryan side and the apartments were handed over to Poles in exchange for their own apartments in Jagello Street which were handed over to the Germans. Then the Ghetto was divided into two parts: one to the right of Baldachowka Street, and the other to the left. This was in the Autumn of 1942. The Eastern Ghetto was under the supervision of the S.S. and its German name was “Juedisches Zwangsarbeitslager” (Jewish Compulsory Labour Camp).

The first director was an S.S. man named Bacher – a cruel and degenerate German. The East Ghetto was organised in the style of a concentration camp, surrounded by barbed wire, and lit up by search lights. The residents had to report for roll call every day. The beds were taken out of the rooms and replaced with wooden shelves. A barrier was put up between the men's camp and the women's camp. The control of the woman's camp was entrusted to women police. In the Rzeszow Ghetto, there were no particular cases of cruelty as there were in the Plaszow Camp, to which the Ghetto residents were afterwards transferred and liquidated. But instead, there were young physical workers who worked overtime in order to earn money to dress those women who were transferred to work from the Auschwitz Camp. Commandant Bacher prohibited the husbands from visiting their wives, and anyone who disobeyed this order was liable to death. Apart from the Eastern Ghetto, there was the West Ghetto which was known as the Schmelz Ghetto and it contained old people, children and those unable to work. This section was surrounded by rows of barbed wire and was under Gestapo supervision. Here too, the Judenrat operated under Dr. Benno Kahana. The families were divided, with the parents in the East Ghetto and the children in the Schmelz Ghetto. The word Schmelz meant melting or smelting, and symbolised extermination.

On 15th August, 1942, there was an order that women with their children had to register at the Labour Office. Then, as well, the Jews interpreted this order optimistically as meaning that women with several children would be free from forced labour. At that time, a division of children began. Women without children, “borrowed” children from those with big families, in the hope of being exempted from forced labour. When the women and children came to report, they were surrounded by an S.S. unit and sent to the Belzec Extermination Camp. Two men were sent with them: one being Dr. Zinnemann, the Assistant Director of the Hospital. I went to Pleiffer, superintendent of the German Labour Office, and asked him not to take my assistant, but he rejected this, claiming that doctors were needed there as well. We did not know where they were being sent but collected money and paid some Poles to find out where the transport was going and to tell us. Some Poles gave us false information, but a pharmacist acquaintance of mine reported that they were being sent to a soap factory where soap was made of Jewish corpses.

I had lived among the Germans for many years; I had studied among them and could not even imagine that they were capable of this. But I was wrong, and remembered the Viennese Jewish writer, Karl Kraus, who once said: “The Germans are not only a nation of thinkers and visionaries but also of judges and hangmen”.[a]

When the men returned to the Ghetto from their work at night and did not find their wives, they began weeping bitterly and despair spread among them. The members of the Judenrat and the Orderlies threatened in the name of the Gestapo, that they would destroy us all if we revolted. The men answered: “We are ready to die”. But finally, they quietened down and the slave life continued

[Page 86]

until November, 1942. This was the silence before a new storm, a new dread. In November, they doubled and strengthened the barbed wire fences.

This was just before the 15th of November, 1942. The Judenrat announced that German war prisoners from the Russian front would pass through Baldachowka Street and we must not talk to them. We could sense that something dreadful was being prepared. The Judenrat issued the Gestapo order that all the residents of the Ghetto had to appear at the roll-call square with their labour cards, and added that there was no reason to fear expulsion because there was no question of expulsion at that moment. When we heard this order on 15th November, we all despaired and did not close our eyes during the entire night. At 6 a.m. we appeared at the square. It was a bitter cold winter day. Snow mixed with rain was falling and we stood in the mud shivering with cold. The wind turned into a gale that shook the barbed-wire fences. The ravens were shrieking on the roofs as though they were an accompaniment to the outcry of our hearts.

My wife and I also appeared at this square. All of a sudden, she said to me that they wanted to take our children away. Gestapo men wearing steel helmets were swarming around us. The Gestapo Officer, Lehman, told Dr. Kahana that the children were to be taken to the kindergarten. We believed this Lehman. The Square was at the gateway of the Ghetto. A long table was placed there and around it sat the Mayor, Gestapo men, Police, an official and clerks. First, they read the names of the husbands who took their children with them thinking they would save them with their labour cards. The first went up to the table. They asked him where he worked and he answered: “I work next to the Eastern railway station”. They permitted him to leave the Square but detained the child. They then asked the woman and she answered: “I work in the Sewing Factory”. They allowed her to leave the Square and detained her child. Many women did not wish to be separated from their children. From me as well, as the head Physician of the Ghetto in the camp who gave them medical assistance, they took my twelve-year-old daughter. They then called my wife and asked her where she worked. She answered that she worked in the kitchens. They brought the child back to the Square. During that moment, her hair had turned white.

My wife collapsed against me and asked me to try to save the girl. I turned to Dr. Ehaus, the District Officer, and said: “This is my only daughter. Please release my daughter, I work as a physician, it will be a recompense for my suffering”. I wept and wailed aloud but this did not help me. I could not save either my daughter or my wife. I lost them before the end of the war. My daughter was one of the last children whose mothers had saved them but hiding them under sacks and in cupboards.

A few hours later, two officers came and asked my daughter's name. People comforted us with the hope that the girl would be returned to us. At that time, we all gathered at the house of Leizer Lev, the dairyman, the father of Irving Low of New Jersey, U.S.A. who is a well-known Communal Worker and philanthropist among the Jews of that State. Through the windows we saw how the children were being loaded onto lorries. Mothers wept and shrieked hysterically. Their outcry went up to the very skies. The Mothers beat their heads against the walls as the German stole their last children before their eyes. We were left without children. All hope had fled from us and we waited for one single redemption – death.

Those who were left continued to work in the laboratories and workshops outside the Ghetto, under German supervision. Bacher, the Commandant of the East Ghetto, was directly under the orders of the S.S. Commandant in Cracow, and not the Reichshof Authorities, and was on bad terms with the local Gestapo. On one occasion, he called his Jewish orderlies and gave them instructions not to admit the Gestapo men. When the latter came to the gate, the guard showed them Bacher's order. The incident closed with the transfer of Bacher who was replaced by Schupke. This man was easier than Bacher, to begin with, for he abolished the punishment of flogging. If a husband visited the other half of the Camp, he did not sentence him to death but fined him and used the money to buy bread for the women in the Schmelz Ghetto. He did not create an atmosphere of fear like the tyrannous Bacher. The head of the Jewish Orderlies was Gorelik, a resident of Lodz who had formerly been a lieutenant in the Polish army. He even suggested to Schupke that when the Russians approached, he would get rid of his German uniform and help him to escape to the forests, and then no harm would befall him. This Gorelik was harsh to

[Page 87]

begin with and afterwards became more decent. He was on friendly terms with Schupke, the Camp Commandant. Schupke sometimes saved Jews, because he had a certain sentiment towards Rzeszow. When he was transferred to the Plaszow Concentration camp, he made things easier for people from Rzeszow, Schupke headed the Rzeszow Camp until its liquidation in January, 1944.

Under Bacher, every Jew together with his clothes was regarded as the property of the S.S. Once, during roll-call, Bacher found a Jew wearing two pairs of trousers. He ordered him to strip and lie down, and ordered two Jewish orderlies to give him twenty blows each on his behind from the right and the left. The orderlies hit gently. He then ordered them to strip as well; and showed them how to thrash. Afterwards, he had them placed in a corridor and shot them.

Once, I was called to Bacher. He complained about a belly-ache. “Is this punishment from heaven for my treatment of the Jews?” he asked. On one occasion he gave orders to transfer my wife to the Schmelz Ghetto. The next day, he had my wife returned to the East Ghetto, and ordered that she was not to work in the kitchen any longer but with me in the Hospital. Bacher ended by dying in a madhouse. After the fall of the Germans, the Poles took Schupke, who replaced him, and executed him in Cracow.

This Schupke once told me that in his time, he had murdered 14 Jews. At the court in Cracow, Lola Weiss, now a resident of Israel, gave evidence that he had also done favours to Jews including her, for he had saved her. But, she confirmed, that she had seen how he had murdered Jews.

I cannot tell or describe everything in its proper order. My memory jumps from here to there, backward and forward. The chain of the narrative is broken. I remember one link and join it to the chain but not always in its place.

To return to Schupke. The Poles told us about the murder of the women in Szebnia. Together with Gorelik, I went to Schupke and asked him whether the rumour was true. “Don't you believe in the nonsense and lies of the Poles”, he said. “I am prepared to go and find out whether the rumour is correct”. He returned and stated like a typical German that the information was wrong. It was not 400 women who had been killed but only 360. The Szebnia Commandant had done it on his own authorities and was responsible. He wanted to send me to the Szebnia Camp together with my wife and daughter to be the physician to the camp and the Ukrainian garrison.

When the Jews of the Ghetto learnt of the slaughter at Szebnia, they began to run away in order not to be sent there. Only 42 men were left out of the 100 in the unit, Schupke was blamed, and in order to save himself, he selected 14 youngsters one day, saying that there was an order to unload coal from the railway trucks. In the afternoon, an order was given to assemble on Parade. Gestapo and Ukrainian police entered at the gateway. Schupke called these youngsters out by name and put them into a room which contained a window facing the Aryan side. The youngsters saw death before their eyes and fled. The Gestapo men entered the room and did not find a single one there. Then Schupke ordered the other lads to strip, killed fourteen of them and sent the rest home.

Only a handful of us were left in the camp. My daughter saw the slain and had an attack of hysteria. After all this, Schupke passed through the rooms. (At the time, the survivors all lived in a single house). He entered my room as well and recognised my daughter. “What are you doing, Gretchen?” he asked her when he saw that she turned her face away from him. The next day, he came to me in the hospital and justified himself, saying: “I had to do that, otherwise the Gestapo would have killed all of them. I'm not the same old Schupke any longer”.

To round off the story of the fourteen young men whom Schupke, the Camp Commandant had put into a room in the Zucker House and who had escaped to the Aryan side through the window. I should add that this happened during September 1943. When Schupke entered the room and did not find even a single one, he came out as though he were crazy, yelling: “I shall destroy you all like dogs”. He ordered us to strip and kneel. Opposite me stood my wife and little daughter who yelled: “Daddy, I shan't give you to them”. I calmed her down. First Schupke called the shoemaker, Milmeister and shot him. Only a few days earlier, the man had made a pair of high boots for Schupke's wife. He then called the shoemaker's son and shouted: “Lie down beside your father!” And he

[Page 88]

killed him as well. In the same way, he killed 14 Jews before our eyes. Afterwards, I learnt that a few of those who had run away remained alive. Others were caught after a comprehensive hunt through the Aryan Quarter. Among those killed was Dr. Tunis, one of the camp physicians. He was killed by a Ukrainian policeman whom he had treated and who had recognised him. Among those who escaped was Dr. Michael Schneeweiss, who is living with us in Tel-Aviv.

Then in the spring time, I went to the Western Ghetto (the Schmelz Ghetto) where I met Dr. Hauptman, the Ghetto doctor. He looked very bad and told me that he was weak with a high temperature. At night, they called me to him and I found that he was dying. He died of typhus, serving his fellow sufferers until the last moment. The epidemic spread through the Western Ghetto and laid may victims low. Relatives were permitted to accompany the dead only as far as the Ghetto gateway. They were not permitted to go on to the graveyard. I was in despair. The residents of the Western Ghetto did not have to work. All that was required of them was street cleaning, and they were under the supervision of the Gestapo. But the Eastern Ghetto was under the command of the S.S. and the Ghetto Commandant received his orders directly from the head of the S.S. Police.

The great responsibility resting on me was more than depressing, and I was afraid that the illness might pass to the Eastern Ghetto as well. So, I applied to the East Ghetto Commandant and suggested that he should prohibit passage from the Western Ghetto to the Eastern, because an epidemic of influenza was spreading in the Western Ghetto – I was afraid to tell him that this was a typhus epidemic.

The old barracks dating back to the Austrian times in Lwow Street, underwent delousing disinfection every fortnight, but apparently without effect, for that was precisely the place where they became infected with lice. The situation in camp was unbearable. Three families lived in a room together and that led to a state of filth.

The old people in the Western Ghetto did not work and knew that they were condemned to death. The people in the Eastern Ghetto worked at various trades. They were proud to be working and hoped that they would be able to go on like that until the end of the war. On their sleeves they wore a band with the letter W for “Wehrmacht” (Defence Forces) or R for “Ruestung” (Armaments). Their parents lived in the West Ghetto. The doctors also became ill except for me and one other who remained in good health. I was afraid of a catastrophe on account of the pestilence. So, I chose ten strong and healthy young men and took specimens of their blood at the Military Laboratory. The result was negative. At last, I also became ill and lay unconscious for several days. At the beginning of the illness, I heard footsteps approaching. This was the East Ghetto Commandant and the Medical Officer of the S.S. “Are you also ill?” asked the Commandant. I swiftly put on my white coat, said that this was the influenza epidemic and showed them the certificate confirming negative findings. The physician believed that this was influenza. But I could not go on with the tests because there was no money.

A few days later, I learnt that the District Officer had informed the Judenrat that the situation in the West Ghetto must be investigated because he had heard that a typhus epidermic had burst out there. People died every day. Luckily for us, he did not come himself but sent the Municipal Physician, a decent and friendly Pole from Posen. He also took three healthy persons, sent their blood for examination and they found to be healthy. This physician received a diamond as a gift from one of the Jews; one of the few jewels he had succeeded in hiding.

The epidemic lasted about two months. When it died down, work continued in the East Ghetto workshops. The upholsterers, the tailors and the locksmiths worked in the Ghetto while groups of youngsters were sent out to work under the supervision of Jewish and Polish police. They went on working between one expulsion and the next, although they were always afraid that the quiet period would be followed by a storm. But, meantime, they wanted to live and the youngsters and orderlies played football, and there were even matches between the East and West Ghettoes.

During those terrible years, a number of Jewish women succeeded in living as “Aryans”. There were cases when Jewish women were caught with Aryan papers on account of denunciation. At the Gestapo offices, they were told that if they admitted that they were Jewesses they would not be shot but would be sent to the Ghetto. And so fresh

[Page 89]

families with their children came to the Ghetto from time-to-time.

I have already related how rumours ran through the Ghetto in July 1943, that they would all soon be sent to the notorious labour camp at Szebnia near Jaslo. In August, the West Ghetto detainees were ordered to parade. The whole camp was surrounded by S.S. units. It should be noted that a parade was held every day together with the roll-call at which the names of all the detainees were called. A daily report on their number was sent to the Chief Command in Cracow. At the time, there were 380 men in the West Ghetto, instead of the 400 who were sent to Auschwitz. The Gestapo then came to the East Ghetto and caught twenty working men in order to round off the number to 400. They were all sent to Auschwitz as required by the Command.

In August, 1943, people in Rzeszow did not know that gas chambers had been built in Auschwitz, but they did know that Auschwitz meant death. Among the 20 youngsters who had been added to the 380 were the bet carpenters. Gorelik, the Ghetto Police Officer went to the S.S. Commandant and complained that the best and most urgently required workers had been taken. “We don't care”, answered the other.

I have already mentioned that the S.S. Camp Commandant whose family I had treated, wanted to send me to Szebnia in order to serve as Camp physician there. My wife was against it. I went to him at 11 p.m. and asked him to leave us with the Orderly and Evacuation Squad. Schupke told me that he would take me in his car. But then the Head Army Medical Officer of the Szebnia Camp came and suggested that I should go with him. “I have a daughter”, I whispered to him so that the Gestapo men would not hear. “I'm only in charge of medical affairs” he answered and permitted me to stay in the East Ghetto together with another 80 people, and the West Ghetto was liquidated.

In Autumn 1943, the last expulsion took place and only 100 young men were left of the Evacuation Squad (Aufraumungs Kolonne). Lotka Goldberg ran away from the Szebnia Camp and returned to the Ghetto. Schupke recognised her (he knew everybody by name) and asked her: “What are you doing here? You deserve an Iron Cross First Class for escaping”. And he permitted her to come back to the Ghetto. Bacher would certainly have killed her. Lotka escaped from the Women's Camp at Szebnia where they killed part of the women including her mother.

The East Ghetto workers now to be sent to residents of Rzeszow, who had numbered 22,000 men and machines were left in the camp. They spoke to the camp Commandant who ordered that the machines and tools should be loaded on the cars and taken to the train with the workers. The despairing men grew calm, believing that they were going to work. The end was that the workers of the East Ghetto were sent to Szebnia and the West Ghetto people to Auschwitz.

The chief grave-digger in the cemetery was named Oiserovitch. He buried all the Gestapo victims in the Jewish cemetery, including Poles killed by the Gestapo. One day, he ran away, saving his two daughters by carrying them off in a death cart. He succeeded in hiding them with Christians. This grave-digger now lives in America and is a wealthy man. He gave evidence in the trial of Mach, the Gestapo Commandant in Rzeszow.

In the Ghetto the words: “Arbeit macht frei” (work brings freedom) hung. The Jews had long ceased to believe this. Each one struggled to remain alive, if only for a few more days.

After purges, evacuations and “actions”, the residents of Rzeszow, who had numbered 22,000 when the Ghetto began, were all crowded in a single building. This was the house of the dairyman, Eliezer Lev. Gorelik, who as in charge of the Jewish orderlies, received a special Argentinian passport from a Gestapo man who had become friendly with his wife. When this became known to the Gestapo, Gorelik and his wife were called to an enquiry. Although they were tortured, they did not give the name of the Gestapo man. After that, they were both shot.

At Lissa-Gora near Rzeszow, there was a labour camp for 500 Jews from all parts of Europe. They worked in an aeroplane engine plant. With the aid of a patient, seven others including my good acquaintance, Eisenberg who now lives in Tel-Aviv, succeeded in transferring to that Camp. Of the rest of the Evacuation Squad who lived in the Lev House, the men were sent to the Arms Factory at Stalowa Wola and the women to the Plaszow Camp, among them, Lola Weiss who now lives in Tel-Aviv.

[Page 90]

Not a single one of the West Ghetto people has remained alive.

By the beginning of January, 1944, not a single Jew was left in Rzeszow. The town was “Judenrein”, as desired by Dr. Ehaus, the District Officer.

The F.M.W. or Flugzeug Motoren Werke (Aircraft Motor Works) was a Jewish labour camp attached to a large labour camp in Plaszow, which in turn was a branch of the ill-famed Oranienburg Central Camp.

The F.M.W. Factory was set up in 1943 and Ghetto Jews were sent there to engage in unskilled work, services, etc. Afterwards, it became a concentration camp. Around the factory a high wall with three iron gates was built. When the factory became a concentration camp; the Jews were housed in wooden huts and worked together with Poles. The 500 Jews included only a few from Rzeszow, maybe about 30 in all, including my wife and daughter and myself. Most of them came from all parts of occupied Europe. The food was bad, but the big halls of the plant gave us shelter against the bitter cold. It was also possible to buy food from peasants. The German head of the factory openly said that the best workers were the Jews. But he was very careful not to say this in the presence of the S.S.

In this camp, I was a physician. The Jews suffered from skin diseases and purulent wounds and sores on account of the lack of food, and I did not have antibiotics at my disposal. It was my duty to report the number of patients every day, but I was afraid to do this for fear that they would have them killed and, did not want them to fall into the hands of the killers.

The orderlies were Jews and were on good terms with the German Director. They asked him to register them all as healthy in the labour cards, and only three or four were registered as ill. The workers included the radio technician Fritz Eisenberg of Bielsko, who now lives in Tel-Aviv. He used to listen to foreign radio stations and gave his friends the news. In this camp, there was a hut for women containing 8 women including my wife, my daughter and Dr. Frederika Herschdorfer, the wife of Dr. David Cohen of Tarnow, one of the founders of Hashomer Hatzair in Vienna. The women engaged in sewing and laundry-work.

In July, 1944, the camp Commander informed me that the Russian Advanced Forces had reached the vicinity of Jaroslaw. Our joy was mingled with fear. I was afraid that the Germans would kill us all before the entry of the Russians, but I was happy that our sufferings would come to an end and Germany would be punished. A few days later, German Sapper officers arrived. One day we, Jewish Orderlies and service men, gathered together and discussed how we could escape. The camp was surrounded by a wall and was guarded by Ukrainian police. It was agreed that the strongest fellows would attack the Ukrainians and disarm them. My opinion was that we all had to try to escape together, for if only part ran away, the Germans would murder the rest. The young fellows promised to take the sick people with them. There were some who opposed escaping for they were sure that the Germans would learn about it and we would then all be finished. They also argued that there were no forests in the neighbourhood and that there was no hinterland to defend them, for the peasants and neighbours could not be trusted. Those who were against flight surrounded the huts and would not permit anybody to escape.

Fritz Eisenberg was the only one with a permit to go to work in the Headquarters. Afterwards, he told us that the roads and streets were full of retreating soldiers. We waited for liberation. Fresh news arrived every day. They said the Germans were burning the archives. We were nervous and worried for we did not know what our end would be. German families were hurrying in alarm to the train. There was a shortage of railway coaches.

One night, a worker came to me saying that he had found the iron gate wide open and that there was a chance to escape. This was at 2 A;M; A few began to run away, but only a handful of them remained alive for the Polish national underground (A.K.) caught them and killed them.

That night the Poles helped Eisenberg and Rosen , who are both in Tel-Aviv, to escape over the wall by a ladder. A young man from Leipzig, the Chief Supervisor of the camp service, reported the escape to the Gestapo Security Police. The camp Commandant appeared within ten minutes, conducted a search and then engaged in a hunt for those who had run away.

That was in July. The fugitives hid in the wheat fields. This time, only 10 people ran away. Most remained because they were afraid of punishment.

[Page 91]

After that, the Ukrainian police force was strengthened but this time they did not revenge themselves on us or punish us. In those days, the wife of a German captain dared to curse the Fuehrer Adolf Hitler for having failed in his war.

Two days after the escape of the ten, the Germans obtained railway carriages and took all of us, about 400 Jews to Plaszow, for we were more important to them than the machinery in the plant. The journey to Plaszow near Cracow, accompanied by Ukrainian police, took two days. S.S. men with dogs waited for us at the station.

There were about 10,000 prisoners at the Plaszow camp which had been built within the area of the Jewish cemetery. At the camp entrance, we were received by the Commandant, a sadistic and murderous young Viennese named Amon Gett who looked like a film star! All of a sudden, I heard a powerful voice: “Dr. Heller! Have you patients, lice, where did you study?” I answered him that I had studied in Vienna.

My companions crowded around me and asked me what he had wanted of me. This young Commandant terrified everybody. He walked around with a small pistol in his hand. If he met a Jew going through the camp, he would shoot him like a bird. When Germany collapsed, he was caught and the Poles in Cracow sentenced him to death by hanging. In the Plaszow camp, there were also Poles. They were caught from time-to-time and sent to imprisonment for a few days or months and then set free. The S.S. orderlies searched through the rooms and were sent to the huts after all our belongings had been taken from us. There was a barrack there containing 200 Jewish women from Hungary who had been brought half-naked from Auschwitz.

In the Plaszow camp there were large workshops and the Jews were in contact with the German Schindler, a fellow-Semite who visited Israel not long ago. The Jews of Cracow worked overtime in order to earn money to clothe the women from Hungary and other urgent needs. At Plaszow I also found Schupke who had been the East Ghetto Commandant in Rzeszow. He treated the Rzeszow survivors with a certain amount of tolerance after having murdered the 14 on account of the escape. Amon Gett, the camp Commandant used the most degenerate and corrupt of the Jews to torment the prisoners. Afterwards, he did everything he could to get rid of these assistants of his by trickery, and hung them. He used to set his dog Rolf on Jews, shouting: “Herr Rolf! At him, bite the dog!” (meaning the Jews). The camp physician was a Jew named Dr. Gross, who was hung together with the camp Commandant, Amon Gett by a Polish Court after the War.

Following our arrival in Plaszow, the labour camp became a concentration camp. There were several children whom the women had succeeded in bringing with, hidden in their bags. Amon Gett ordered that these children should be caught. The women were compelled to appear naked at the roll-call, and afterwards, he sent them to Auschwitz. While the children were being stolen away, he played a German record: “Adieu Mama, wir fahren ins Himmelreich”. (Goodbye mother, we are going to the Kingdom of Heaven).

The Rzeszow people remained in Plaszow for about six weeks, but part of them were sent to Germany after 8 days. In Plaszow, I stopped working as a physician and was engaged in digging. Gross, the camp physician, did not wish to employ me in medical work.

One Saturday, during August, there was a parade in the camp of men and women separately. It was conducted very meticulously. In the distance, I saw my wife, my daughter and Dr. Herschdorfer. All the women were sent to Auschwitz – 120 in each carriage, without water and in stifling heat. The men were left in camp and fresh Jews were brought who had been evacuated from the Arms Factory at Stalowa Wola near Rzeszow. Among them were Dr. Willy Kahana, an advocate from our city and other Rzeszow people.

On the Sunday, the men were paraded again and all of them, accompanied by S.S. men, were sent to the terrible Mauthausen camp in Upper Austria. There were 120 of us in each carriage. The S.S. men inspected our belongings, emptied our pockets and took everything. The situation in the carriage was terrible. There was no air to breathe. Each one tried to make for the space between the carriages and the steps in order to catch a little air. Cries of “Water! Water!” split the air. The guards answered: “If you'll be good children, you'll get water at the next station”.

Every day, they took at least four corpses out of the carriage. When they opened the door

[Page 92]

to take out the bodies, we could breathe a little air. That was how we travelled for four days. There was no lavatory in the carriage. We went towards Mauthausen by way of Auschwitz. Mauthausen had been a Russian prisoner-of-war camp during World War I. On the way to the camp, we passed a stream of water. We flung ourselves down and drank as eagerly as though it were milk. There were about 80,000 prisoners at the Mauthausen camp and the Auschwitz inmates were also brought there after Auschwitz was evacuated.

We were put into a disinfection hut and then passed to a hut capable of holding on 500 men; but 2,000 prisoners were housed there. We lay crowded like herrings in a barrel, heads next to feet. Police came to see whether there was still another crack into which to place one more person. The Rzeszow people arranged themselves together. Among us were Dr. Willy Kahana, Herschdorfer, Feuer and others. Choking airlessness and despair were our portion. At night, we suffered from nightmares. In our sleep, we yelled: “They are shooting us” until we became completely unconscious. Among the prisoners was a one-time German naval officer who had been sent to the camp as a punishment, to serve there as the supervisor of the hut. More than once, he stood up and yelled at us: “you stinking Hebrews, do you believe that even one of you will leave the camp alive? You'll see freedom through the chimney of the crematorium facing your huts, and the same with me!”

The Germans took our clothes and we were naked for a few days. In our clothes we had papers and pictures and everything vanished. Afterwards, we received only shirts. We did not work for several days. Later, an additional inspection was held. They searched between our teeth and also inserted their fingers into the anus. We were brought to an underground structure and believed that they were taking us to the gas chambers. There they shaved us from the soles of the feet to the skull. In the middle of the head, they left a “pathway” as a sign to recognise a prisoner if he escaped. (They called the path: “the lice promenade”) Afterwards, we were taken through the hills to work in caves. Until 1943, this had been a detention place for German prisoners, who died there by the thousand. Their bodies were flung into the abyss. The S.S. murderers called these dead “Parachutists”. A few held out in this harsh toil. One of the Rzeszow men, Herman Goldstein who had a bad heart, went to an S.S. man and complained of pains. The S.S. man ordered him to go to the fence and shot him from behind.

We were allowed to go to the lavatory only between 8 and 9. Water was given only for one hour a day and might only be drunk in the cellar. We were flogged for any dirt. At the gateway of the camp, there was a lovely garden and important detainees were kept in the hut there. Among them were currency counterfeiters for the Germans. Among others were Schuschnigg who had been Prime Minister of Austria, the Hungarian Count Aponyi, etc.

After a few weeks, the Rzeszow group were split up. I was sent to the town of Melk where there was a branch of the Mauthausen camp. There we were engaged in erecting underground structures for factories that were transferred from Russia and France. We met groups of Polish women prisoners who had been brought from Warsaw after the suppression of the Bor-Komorowsky Revolt. They told us that the Germans were still holding out in Warsaw, which depressed us very much.

When we came to the railway station, we found carriages fit for human beings for the first time. There was room for each of us to sit. Another group of Rzeszow men was sent to Gussen where the pharmacist, Herschdorfer died in October, 1944. I worked at Melk from October 1944 until April 1945 building underground stores.

Of the hundreds of people with whom I was in touch, I can remember only five who are still alive. They are: Dr. Willy Kahana, Hermann Feuer, a dental technician named Allowitz and two others, who are all in the United States.

When we learnt that the Russians had reached Vienna, we were afraid that the Germans would shift us westward and some of us would certainly be killed during the evacuation. I was ill at the time. One day, as I was eating the noon meal of potato soup, I heard the order to dress. We were all in shirts and quickly put on the clothes of the dead. Patients who could not leave their beds were put into cars, and we were told that they were

[Page 93]

flung into the River Danube. A roll-call was held and we were ordered to run forward. Those who stumbled and fell were pushed aside and those who succeeded in running were placed in a special hut. The next day we were taken to the River Danube and carried by raft to the town of Linz. There we each received a quarter of a loaf of bread with German margarine, and began a three-day march to Ebensee where there was a branch of the Mauthausen camp. This was April, 1945. We left the blankets on the way because it was hard for us to carry them.

We arrived at the camp which was in a forest. For two days, we did not go out to work because everything was in chaos. On the third day, we were sent to work at the railway station which had been destroyed by English bombers. A sense of vengeance filled our hearts as we looked at the ruins. The work was hard. We were weak and ill, but we were afraid to be sent to the Revier Hospital which was actually an Institute for the extermination of Jews. Members of other nationalities were sent to a different hospital. In spite of this, I asked to be admitted to the Revier Hospital because I was exhausted, beaten and injured. I applied to a doctor, a Jewish prisoner, to admit me. I longed for hospital treatment and I was prepared for any suffering.

During the march to Ebensee, all those who could not march were shot and flung into the river Traun. In Linz, we saw notices on walls: “The war is not finished. Roosevelt the head criminal against the German people is dead”. S.S. men said that the war was only just beginning. The road from Linz was difficult. My legs were injured. I gave my bread to two French prisoners and went on, leaning on their shoulders.

As said, I asked the Jewish doctor to admit me for treatment but he said: “You don't seem to know the meaning of the Revier”. I begged him, “just let me rest for two days”. He brought me to an S.S. man who refused to admit me, in spite of the doctor's recommendation. In the afternoon, I registered again. Another doctor warned me: “Don't you know how people finish up here?” But he brought me to another S.S. man who admitted me.

After a bath, they put me into the Revier Hospital for the Jews. The head of the “Block”was a Viennese criminal, a cruel person who did not permit anybody to speak. Anybody who opened his mouth was shot. They took our shirts away and we sat naked. And there I saw before me a man lying in his shirt who kept staring at me. Suddenly, I heard a whisper: “Are you Doctor Heller, the doctor of Rzeszow?” I was afraid to answer and blinked an affirmative with my eyes. Before me was a Jewish carpenter from Kalish who had been brought to Rzeszow by the Germans. Now he was making the furniture for the home of the “Block” superintendent. This carpenter, named Engel, was really like an angel from heaven to me and delivered me from death. He was a skilled carpenter whom the superintendent like, and he told him that I was a famous physician. One day, while the soup was being distributed, the superintendent raged at me furiously: “Who are you?” Trembling all over, I answered that I was a physician who had studied in Vienna. He ordered me to report to him in half an hour's time. I had no watch so I could not be punctual. Luckily, a young German told me the exact time. I went to the superintendent's room, knocked at the door and told him that I was reporting as ordered. He then told me to take clothes and begin working in the ambulatory department the next day. It was my first day without distress after years of suffering, and it was thanks to the carpenter Engel from Kalish.

This was one day before the arrival of the Advanced American Forces. We received an order to appear at the parade, and the patients were brought on stretchers. We were ordered to enter a tunnel because of the approach of the battle front. From French prisoners, we learnt that the tunnel was mined. They refused to enter it and insisted that they were prepared for losses as was customary in wartime and did not wish to enter the shelter. The members of the German staff discussed the matter and finally decided to do without entry to the tunnel and returned us to the camp and the huts.

The camp burst out rejoicing when a Polish prisoner announced that evening at the top of his voice, that the S.S. men had vanished from the watch towers. Among us were pious Slovakian Jews. When they heard this, they began dancing and songs echoed all through the camp.

[Page 94]

Happy shouts: “The Americans have come”, we heard all night long. I tried to calm them down. I was afraid that the S.S. men would come back and that the report about the Americans was premature. But it was impossible to stop the outburst of joy. Only at 6hr in the morning did the first American tank appear containing 3 soldiers. This was the Sabbath day.

Men danced with joy and kissed one another ardently. They literally bit and pinched one another. The Slovakian Hassidim sang Sabbath hymns and their faces were radiant with joy. They danced as though they were crazy. The S.S. men had vanished including the superintendent of the sector and the doctors who were Slovakian Jews. The Americans asked us to go back to the camp so that they could take films. Among them were Jewish physicians of German origin and Rabbis. They were particularly interested in the Jewish camp which had suffered more than all.

By order of the American staff officer, all the inhabitants of the German city of Ebensee were brought to see with their own eyes what the Germans had done. The inhabitants claimed that they had not known a thing, and the Priest apologised that they did not have the slightest idea of what was happening in the camp. They were ordered to clean the camp down, to wash the Jewish patients and clean the floors. The prisoners and captives took revenge on their foes and tormentors. They caught the S.S. men, the Kapos, the Block superintendents – they killed them and flung them into the furnaces. The Viennese criminal who headed my Block was also punished.