|

|

|

[Page 103]

by Sh. Goldman

Translated by Jerrold Landau

We find a brief expression of what was transpiring in the souls of the Ratno youth during the early 1930s, with the background of the boredom and the lack of prospects in the town, in this chapter from the diary of Shmuel Goldman, who is well-known from the Book of Klesowa. We should note that he was a 17-year-old lad at the time he wrote this material in his diary. This was written in February, 1930. The words speak for themselves and require no commentary. Even if we strip away the cloak of rhetoric which was natural for a youth of that era in those towns, we see a realistic picture of the reality. Shmulik Goldman, a 17-year-old lad, expresses his personal revolution. He left his parental home, did not even bid farewell to his father, and set out for a place that to him symbolized the epitome of pioneering that was both harsh and wonderful, which was the motto of Klesowa during that time.

… My town Ratno. Sabbath. Heaviness of the heart, and there is no air to breathe. It is constricted around. I have no more place here. Tomorrow I will be leaving the town to the place to which my heart entices me to go. There I will sense the taste of freedom. There I will not have to lean on the shoulders of Father and Mother. I will be a productive man – a worker – sustaining myself through the toil of my hands. I packed my clothes and other personal effects in a suitcase. On Sunday, I will be traveling from here to Klesowa.

It was Sunday morning. I got up – and I found that sadness pervaded in our house. Father was groaning. Mother was weeping. The hope of Father and Mother was that I would not be able to live on the Kibbutz, for one must work hard there and I am so weak in body. Aside from this, the conditions of life there cannot be compared at all to those which I am accustomed to from home. I would certainly escape from there in a brief period and return here. I parted from my parents. Mother hugged me and embraced me, but Father refused to part from me. It was silent around. There were tears on all faces. There was silent wailing. Everyone was weeping – and me too… Next to the bus there were dozens of people who came to bid me farewell. Their eyes were fixed upon me – some with indifference and some with jealousy.

The bus moved. The trip was quick, and I was already in Sarny. In another half an hour I would be in Klesowa, the place I so desired, the place which led to the rift between me and my parents and made me cause them so much suffering.

I arrived in Klesowa on a rainy day. There was a sharp contrast between nature and my golden dreams… The first person to greet me at the train station was a lad who was not a member of the Kibbutz. I asked him, “How do we get to the Kibbutz?” He looked at me and said, “How nice are your shoes, but in another hour they will no longer be in your possession. In their place you will receive a pair of 'rubbers.' It is also too bad about the nice coat that you are wearing. Arise, lad, and travel immediately back to your home!” “Don't worry,” I answered him, and continued on my way. Then I was met by a lad who had a sort of old hat on his head, torn pants, and “rubbers” on his feet. I asked him the way to the Kibbutz, and he showed me the way there.

I came to the house of the Kibbutz. The windows were broken. There were wooden planks in place of glass window panes. It was filthy and damp. Drops of water dripped from the ceiling incessantly. There were loaves of bread upon the long tables. On one of the walls, there were dusty red bands covering the pictures of Borochov and Trumpeldor. My eyes fixed upon the inscription on one of the pictures, and I stared at it for a long time. Suddenly, one of the girls who worked in the kitchen ran in and asked me, “You are new, from where are you? Perhaps you will eat something?” She ran into the kitchen and returned with a small dish of porridge

[Page 104]

for me.

The girls who worked in the clothing warehouse took my suitcase from me and left in my hands only work clothes. One of them brought me a pair of “rubbers.”

I met a girl whom I knew from our mutual participation in the “Hechalutz Hatzair” (Young Pioneers) counselors' camp. There, her face and white hands were suffused with such delicacy, whereas here, her face exuded somberness and worry… There was only a simple greeting, “So you are here too? All the roads lead to here”…

The next day, I went out to work in the quarry. I dug up rocks to load on the wagons at a quick pace. Someone turned to me and said, “During the first days, until you get used to the work, you should not dig up large rocks. Leave me the heavy ones, and you take the light ones.” At first I was embarrassed, but the pleasant words of the lad were friendly, simple, and convincing.

In the evening, a meeting took place to celebrate the five years of the existence of the kibbutz at that place. More than 200 hearts beat together in the narrow room. It was as if the walls and the ceiling were breathing heavily and sweating. Life was difficult; issues were difficult, but true… One of them said, “We have known failures, but we have overcome them. Through suffering and stubbornness, we will forge here a workshop for Hebrew pioneering.” A second one continued on by telling about “a difficult winter, lack of work, desertion… but we grew and we are now a large group.” Every word that was spoken hit its mark, was etched upon the heart, created enthusiasm, and demanded. Will I also be able to persevere as they did? All the strands of my soul whisper, “Yes!” After the meeting, there was dancing until midnight.

We set out for work early in the morning. Despite the pains of acclimatizing, I entered into my work, which became natural for me.

|

|

[Page 105-alt]

by Devora and Yehudit, Mesilot

Translated by Jerrold Landau

We both joined the Hashomer Hatzair movement when we were about ten years old. This was at the time when organized activities began among the youth of Ratno. The Hashomer Hatzair in Ratno excelled in its dynamic activities over and above all the other chapters in the Wolhyn district. We now realize that this accomplishment was only due to the leadership of the chapter head Moshe Droog. He succeeded in organizing the activities of the chapter in such a manner that we would be able to continue the appropriate activities even when he was absent from the chapter. Indeed, Moshe Droog was forced to remain in Kovel throughout most of the days of the week since he was studying in the gymnasium there. Only now can we begin to appropriately appreciate his unique way of action, for, as we know, many youth movement chapters in Wolhyn weakened greatly or even disbanded when the chapter head left or made aliya. Such a thing did not take place in Ratno. The chapter occupied all of our free time. The Hebrew language was used primarily in the chapter, but there were also echoes of Yiddish. The students of Noach Kotzker and the excellent teacher Brodsky had no difficulty with their free expressions of Hebrew; however, there were also those in the chapter who did not study in the Hebrew school or who stopped their studies too soon.

Our household quickly made peace with our membership in the movement, even though this membership meant parting from the home, i.e. our aliya. The Zionistic pioneering spirit that had brought us to the youth movements, primarily Hashomer Hatzair and Hechalutz, slowly penetrated many of the Jewish homes in the town. As we got older and entered the older levels of the movement, aliya to the Land was no longer considered something unusual, as it was when the first ones, Mordechai Weinstock and Stern, made aliya. Life in the town was supported upon nothingness. The youth saw no chance that the dark skies would brighten. The clouds

[Page 106-alt]

over our heads in the town did not clear, and there was no chance that they would clear. We bound ourselves firmly with the Land of Israel, and the realities there interested us much more than the realities in Poland.

We joined the nucleus of the Tel Chai Kibbutz that was organized in Wolhyn. We went to Hachsharah, and made aliya to the Land. After some time, our Tel Chaim Kibbutz merged with the Mesilot Kibbutz of the Beit Shean Valley. We are located there to this day.

There is no doubt that Hashomer Hatzair in Ratno was the prime factor that forged the spirits of the hundreds of youth who passed through this chapter. It strengthened their spirits, placed challenges before them, and taught them how to deal with the many difficulties and stumbling blocks in their path. This was perhaps true with every chapter of Hashomer Hatzair, but it seems to us that this was proved most clearly with the Ratno chapter. There was something unique about this chapter, and only someone who has passed through all the educational chapters and groups in this chapter can understand the essence and reasons for this uniqueness.

[Page 105]

by Zeev Grabov

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The impetus to found the chapter came from Amalia Droog. She was a student of the Hebrew Gymnasium in Kovel and belonged to the “Galei Aviv” brigade of the Hashomer Hatzair Chapter in that city. When Amalia came to Ratno for summer vacation, she advised her brother Moshe to establish a chapter of Hashomer Hatzair in Ratno. Moshe agreed, and was assisted in his first steps by Motka (Mordechai) Melamed of the Kovel chapter. This took place in the summer of 1928.

The first members of the movement were the grade six students of the Tarbut school, including Zelda Feintuch, Dvora and Chaya Grabov, Yehudit Sandiuk, Chaya Weintraub, Pnina Ternblit, Feiga Marin, Berl Honyk, Zelig Bander, Chaim Ides, Moshe-Chaim Fuchs, Simcha Leker, Eliahu Feintuch, Yosef Steinberg, and others. Most of these youths left the chapter after a brief period. Only Chaim Ides, Berl Honyk, and Moshe Chaim Fuchs remained.

Connections were quickly forged with the central leadership in Warsaw as well as the leadership of the Wolhyn District in Rowno. Sections, brigades and groups began to form, in accordance with the organizational structure of the movement of that time. The living force behind the chapter was Moshe Droog. The leadership of the chapter included: Zelda Feintuch, Chaim Ides, Berl Honyk, Moshe-Chaim Fuchs, Chaya Grabov, Henia Karsh, and others. The chapter grew for a period of two to three years, and it already had four groups of “Kfirim” (ages 10-12), two groups of young scouts (Tzofim), two groups of older scouts, and a group of graduates who formed the kernel of the chapter. Every group had a counselor. The activities and programs were conducted in accordance with the plans received from Warsaw and Rowno, and were carried out primarily through the counselors themselves.

The “maon” (as the location of the chapter was called) was located first in the house of Shefe Langer, then in the house of Chmiler, and then in the house of Zelda-Leah's, until finally it settled in a spacious hall that was designated for that purpose as a meeting hall, replete with a stage for performances and public gatherings. This house belonged to Itzel Baal-Chotem (literally With the Nose) and was a beehive of activity on all the days of the week. It was decorated with all types of drawings and insignias, the work of Goldale Droog. Every group had its own corner in the hall, and set activity days. The counselors of the “Kfirim” came from the “Hatzofim” group, and the counselors of “Hatzofim” came from the graduates. The names of the “Kfirim” groups were “Zrizim”, “Zivoniot”, “Charutzim”, and “Dganiot”. The names of the “Hatzofim” groups were: “Snuniot”, “Yarden”, “Nesher”, and the like. Each group had its own flag that bore the insignia of the group. The groups formed the brigades, which also had their own flags. In one word – the organization was exemplary. The group often had visits from the central

[Page 106]

and district leadership. These visits inspired a renewed wave of pleasant activities, with new songs with which the group became familiar. They also firmed up the connection between the chapter in Ratno and the entire movement. For the most part, the visitors would be hosted in the homes of Chaya and Devora Grabov or Moshe Droog. A wall newspaper, in which many members of the chapter participated, appeared monthly. Many Zionist activists would come to look at it and enjoy the fine Hebrew of the articles of the Ratno youth, who gave expression to their thoughts and aspirations in this publication.

An important event in the life of the chapter was the public examination that was organized by the “Kfirim” with the participation of the parents and teachers. People would only be accepted into the movement after they passed this test. Then, the head of the chapter would give them the blue band and affix the “colors” to their shoulder, and they would be considered “Shomrim” in all respects. This was an impressive event, and served as a topic of discussion for the members of the chapter, the students of Tarbut, and in the homes of the members.

After the ceremony, the inductees would repeat the ten commandments of Hashomer, They would be especially careful with the “Shomer word.” The meaning of the “Shomer word” was truth and firmness, and woe unto anyone's use of the Shomer honor word for a matter of falsehood…

|

|

With the crystallization of the ideological path that began in the Hashomer Hatzair movement, a deeper delving into the education activities began to take place. This was helped significantly by the publications of the movement: “Hamitzpeh” – the publication of the Hatzofim, and “Hashomer Hatzair” – the publication of the graduates. Tens of copies of these two publications were distributed in Ratno, not only among the members of the movement. During the early 1930s, the personal soul

[Page 107]

was already accentuated. That means: going out to Hachsharah and aliya to the Land. Although the Socialist idea was the founding idea of the movement, scouting as not pushed aside, for the Ratno chapter nurtured it from its inception.

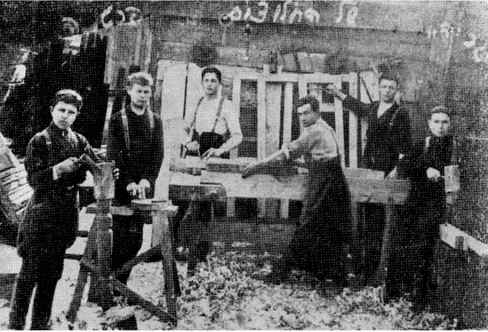

{Summer Moshava of Hashomer Hatzair in the village of Vydranitsa.}

The following fact testifies to the level of success of the chapter in scouting and parades: In 1935, the Hashomer Hatzair chapter organized a festive parade to celebrate Lag Baomer. The Jews of Ratno, and not only Jews, watched the parade that brought joy to their hearts, for we rehearsed it properly and were attentive to each and every detail. The next day, I met Aharon-Shia Konishter, Moshe's father, who transmitted the following announcement to us: “The chief of police asked me to transmit the request to you and Golda Droog that the Hashomer Hatzair chapter appear in the parade in honor of the Polish Independence Day on May 3, which will take place in a few days.” He repeated himself and stressed that we were to appear in the same fashion as we did on Lag Baomer, “with full arms”, meaning with full splendor and glory, for

[Page 108]

the “who's who” of the district of Ratno would be present, and the police chief desires that the parade leave a deep impression. To add strength to the request, Konishter added that the chief felt the need to point out that if we do not appear in the parade – we will have nothing more to do in Ratno.

Things moved along, and nobody imagined that we would respond anything, but positively, to the police chief. We appeared appropriately, and I recall that Golda Droog even recited a poem in Polish, which also left a deep impression. In return for our participation in this parade of the Third of May, we were later able to carry on our activities in the chapter without any government interference.

Literary judgments were often organized in the chapter on various topics, such as: Shakespeare's Shylock, Bialik's “Lion without a Body”, Shabtai Tzvi, and others. These “judgments” attracted large audiences, and those who participated in them in an objective manner prepared seriously for their appearance as witnesses of either the prosecution or defense.

There was great preparation in the chapter in 1933 in anticipation of the celebration of five years of its existence. The movement in general spoke about intensification, enrolling new members, deepening the educational activities, etc. The Ratno chapter took part appropriately in all of this. Within a few months, the girls wove the flag of the chapter with colorful threads. A splendid parade through the streets of the city took place to dedicate the flag. The play of Yitzchak Lamdan, “Massada”, was performed at the party celebrating five years of the existence of the chapter. A great deal of preparation took place for this play. The chapter was decorated with many mottoes and symbols, and this was the first time that the electric lighting operated. The hall was filled to the brim with adults and youth who purchased tickets for this festive occasion. The celebration was opened by a choir conducted by Meir Rider, singing the song Lehava, Alay Lehava” (A Flame, A Flame is Upon Me). This was followed by an athletic display in the form of a pyramid. The conductor of all of this was Moshe Droog. At the end of the celebration, the members of the leadership of the chapter as well as those graduates who excelled in their activities were granted the “Third Level”, as a sign of “be strong and powerful.” Those who received this symbol affixed it permanently on their Hashomer shirt and were very proud of it.

|

|

The chapter also utilized outside people for its educational activities. For example, Mordechai Janower, a member of “Young Hechalutz”, would give lessons in Hebrew literature; the teacher Kotzker would lecture on various topics; Avraham Grabov, a member of “Young Hechalutz”, would lead various discussions with the graduates of the movement whenever he would be in Ratno. During the long vacation, Amalia Droog would give lessons on the knowledge of the Land.

A leadership change took place in the chapter starting from the years 1933-1934. Moshe Droog began to prepare for aliya, and he transferred the leadership of the chapter to Chaim Ides. After he went on hachshara, Zelda Feintuch became the head of the chapter. The next one, after Zelda went on hachshara, was Moshe Konishter. When he too went on hachshara along with all the members of the “Nesher” group, the leadership of the chapter was given over to Goldale Droog and the writer of these lines.

[Page 109]

The new leadership of the chapter was not shy about its advancement. Serious activity took place in all areas. It is especially worthwhile to make note of the Chanukah and Purim parties that were conducted with great fanfare. The meetings of the chapter served as a forum for an accounting of the activities for the funds, including the fund for the workers of the Land of Israel (Kapa”i); for noting the names of the groups that excelled; and for laying the plans for future activities. Chaim Ides served as the librarian of the Y. Ch. Brener Library. The librarians and their advisors regarding the purchase of books held an annual meeting in the home of the teacher Kotzker. They would update the catalog of the library and identify those books that were “forbidden” to those of a young age.

The chapter fulfilled a special role in its activity on behalf of the Jewish National Fund. Among other things, the income from the selling of bottles and various rags in the summer, horseradish harvested from the frozen ground for Passover, work in the baking of matzos, chopping trees in the winter, and other such activities of this sort was donated to this fund. A portion of the funds was donated to the Hashomer Fund and to purchase sports equipment for the chapter.

During the 1931-1932 school year, new teachers were hired for the school, including the teacher Rozen, who was a member of Beitar. It is obvious that the Hashomer Hatzair chapter was a thorn in his eyes, and it was difficult for him to witness its constant growth. He used all sorts of means to turn the students toward Beitar. Despite his great success in teaching Polish literature in the upper grades, he did not succeed in transferring students from Hashomer Hatzair to Beitar. After some time, young teachers who were graduates of the Tarbut Seminary in Vilna, were hired as teachers. Some of them had been members of Hashomer Hatzair. Of course, we found common ground with them, and they participated with us in everything related to the activities of the chapter. The teacher Shlomo Karlin, young, handsome, and musically inclined, is to be especially noted. He organized a mandolin band in the school, and also helped establish a unique band whose instruments were bottles filled with water in varying amounts. After Amalia Droog returned to Ratno as a graduate of the teachers' seminary and began teaching in the school, additional growth of the chapter began, and the Hashomer education deepened. This continued until the Soviet invasion of the city.

|

|

The Summer Moshava

As is known, these Moshavas (summer settlements or camps) were the daily bread of the Hashomer members. The primary leadership of the movement, as well as the leadership of the Wolhyn region, organized many summer Moshavas, both central and in outlying areas. However, the members of the Ratno chapter were unable to participate in these Moshavas, for the cost was beyond the means of the parents, most of whom were lacking in means and to whom such an expense seemed superfluous. The leadership of the Ratno chapter decided to organize a local summer Moshava. The plans and preparations for this began after Passover. One of the activities designated to provide means for the summer Moshava was the collection of sugar. Every member of the chapter was required to bring

[Page 110]

one cube of sugar when he came to the chapter. Thus, 2-3 kilograms of sugar were collected each month. We would sell the sugar at a low price to one of the shopkeepers who was numbered among our friends. The income would be divided into two: one half would be dedicated to the fund for the Moshava, and the other half would be kept for an emergency. What type of emergency? It means that, if heaven forbid, a danger existed of losing the flag of the Jewish National Fund, which the movement had received since it dedicated most of its income for that fund. Throughout three months, we collected sufficient money to rent a barn and a house next to the village of Vydranitsa, a distance of approximately 7 kilometers from Ratno, where we intended to conduct the Moshava.

However, sugar itself was insufficient. When the time came to go out to the Moshava, we began to collect “other vegetables”[1]: potatoes, cucumbers, groats, noodles, and other such provisions which were to serve as our daily fare in our summer Moshava. The campers were expected to bring eating utensils, pots for cooking, firewood, and the like. Many of them had to bring these from their own homes.

Two or three days before we went out to the Moshava, a group of older people went there to prepare the area, and especially to dig tables from the sandy soil, in accordance with all the scouting principles of Boyden-Paul upon which we depended.

The Moshava itself lasted for two weeks. We slept on straw and hay in the barn. The flag of the chapter fluttered high, and an honor guard stood next to it day and night. Attempts were made to steal the flag, but they failed, for the eyes of the scouts were alert, and the members of the guard fulfilled their role faithfully. Aside from various study sessions, the summer Moshava made trips in the region to acquaint themselves from close up with the landscape, the plants, etc. At the end of the Moshava, we arranged a large parade with torches through the streets of the town.

The Hechalutz Hatzair organization also learned from our attempts, and they too arranged a Moshava in that same village, not far from the Hashomer Hatzair camp. It is fitting to note that friendly relations generally pervaded between them and us. I recall only one case of a battle between us. This took place when it became clear that Hechalutz Hatzair was about to receive the guardianship of the flag of the Jewish National Fund, as it succeeded in bringing in a larger sum that year than did the Hashomer Hatzair chapter. Everything was arranged for the flag to be given over to them. However, when the deputy, Mr. Asher Leker, and the secretary, Mr. Kamper, were making the final preparations, Berl Honyk, who was responsible for Jewish National Fund activities in our chapter, suddenly appeared. He brought with him two young scouts with a large sum of money that had been collected from the sale of sugar, and gave it over to the fund. Thereby, he tipped the scales and averted the danger that the flag would not be left to us. The movement breathed a sign of relief…

The Final Years

After the graduates of the “Nesher” group went out to Hachshara in the Shomria farm in Czestochowa, the leadership of the chapter was transferred to a younger group, as had been said.

[Page 111]

|

|

|

|

|

|

From that time, the central kernel was the “Tel Chai” brigade, and Goldale Droog demonstrated that she could be depended upon as she held the scepter of the head of the chapter appropriately. Moshe Ponetz, from among the graduates, helped her and me significantly with the organizational and educational activities. In 1938, 20 of the graduates went out to hachshara in Rowno. They returned to Ratno with aliya permits, but the gates of the land were virtually closed and certificates were not available. This situation caused a negative feeling among the graduates, which got worse as the economic situation in the town became more serious. Signs of the worsening depression could be seen everywhere. The Tarbut School was also struggling hard for its existence. The chapter was a sort of drop of comfort in the increasing sea of tribulations. At that time, the activities of the choir were renewed under the conductorship of Aharon Roizman, who replaced Meir Rider after he transferred to Beitar. Performances were put on, the income of which was dedicated to the purchase of books for the library, which already had more than 1,000 books from the choicest of literature.

[Page 112]

The final performance put on by the chapter was “The Yeshiva Student”. It enjoyed success.

When the Soviets invaded Western Ukraine in September 1939, a dark, heavy cloud descended over all the activities of the Zionist institutions and organizations. All of the movements which served as the “Additional Soul” of the Jewish community of Ratno were forced to liquidate their activities. Thus came the end of the spirit of Jewry during the Soviet era even before the Jews themselves were physically liquidated by the Nazis.

|

|

Translator's Footnote

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ratno, Ukraine

Ratno, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 5 Jul 2015 by LA