[Page 225]

Chapter Seven – The Social Institutions

[Page 226]

[Section TOC - see main page]

[Page 227]

Linat Tzedek and Bikur Holim

by Yehudah Szaya

Translated by Sara Mages

The Linat Tzedek [“Lodging of Righteousness”] society operated in our

city for many years and its goal was to provide medical help of all kinds to

the city's poor. Indeed, there was the Kupat Holim [“Patient Fund”],

but it only took care of organized laborers and only a few Jews were among

them. Many Jewish families from the lower classes were deprived of any medical

help. Therefore, Linat Tzedek tried to fill this gap for those families. My

father, the late Yitzhak Szaya, was one of the activists on the committee of

this society and I had the opportunity to closely follow its operations.

The activity of Linat Tzedek branched out in several directions: A) if

necessary, doctors were sent to the patients' homes; B) “notes” were

handed out for a doctor's home visit; C) money or “notes” were given

to obtain medicines at pharmacies; D) medical equipment such as rubber water

bottles, thermometers, bedpans etc., was distributed on loan; E) night shifts

were set for seriously ill patients; F) patients' visiting times were

established, in other words: members of Linat Tzedek and Bikur Holim [Visiting

the Sick] visited the patients' homes for encouragement, treatment and

clarification of questions related to the illness and the family's financial

situation.

There were several ways to finance the society's activities such as: A)

fundraising in synagogues during the aliyah [being call up] to the Torah on the

Sabbath and holidays; B) acquiring regular donors with a monthly payment; C)

organizing special fundraising campaigns during family celebrations,

engagements, weddings, bar mitzvah celebrations, etc.; D) handling the

acquisition of regular or one-time donations from landsleit [people from the

same town] organizations or individuals abroad.

Young people joined Linat Tzedek several years before the Second World War.

They mainly devoted themselves to the “Glass of Milk” project for the

children of the poor in educational institutions. Thanks to the young people,

the financial situation of the society was somewhat alleviated. The society was

always in a deficit and its activists “wracked their brains” on how

to cover it [the deficit] and meet current needs. Among the society's most

prominent activists in the last period were Avraham Yakov Tiberg, Leizer

Rojanski, Eliezer Kaplan and Yitzhak Szaya.

The number of members of Bikur Holim society was quite noticeable. They

maintained their own committee house (at the Zylberszac's yard in the Market

Square area). They gathered there on days off from school and on the High

Holidays to hear “sermons” on current affairs from the society's

rabbi, the late Reb Yakov-Dovid. On weekdays, many society members came to hear

a chapter of Mishniyot [Oral Torah] from the society's rabbi and on the

Sabbath, between Minchah [afternoon service] and Maariv [evening service], a

“sermon” on the weekly Torah portion. Among the activists of Bikur

Holim in the last period were Michal Melamed, Moshe Fiszhof and Y. Markowicz.

The latter, who was a milk distributor by profession (he lived on Przedborska

Street), died of typhus, which he contracted from one of the townspeople while

fulfilling a duty for Bikur Holim.

*

In 1938, the Linat Tzedek society managed to raise an amount of about two

thousand zlotes, which was considered a great achievement in those days. This

was made possible thanks to a substantial donation received that year from the

“Relief” of the landsleit [people from the same town] in New York

(the chairman at that time was Shlomo Epsztajn and the secretary was Leon

Ejlenberg) and from the benefactor Sol Greenberg, also from New York. Sol

Greenberg was one of the regular donors to Linat Tzedek. In addition to his

personal donations, which he sent from time to time for the needs of the city's

charitable institutions, he also encouraged the “Relief” and the

society of former residents of Radomsk in America to support these

institutions. In the aforementioned year (1938), Sol Greenberg personally

donated and transferred to Radomsk $265. From that, $50 was given to Linat

Tzedek, $30 to “House of Bread,” $60 for meat to the poor, $25 for

poor women who had given birth and $100 to Kupat Gemilut Hasadim [“Charity

Fund”].

On 1 November 1938, a festive meeting of the Linat Tzedek society was held in

Radomsk. It was dedicated to summarizing its successful activities in the past

year and outlining its future course of action. In addition, the role of Sol

Greenberg of New York in this activity was also noted (at that time it was

thirty-five years since his immigration to America, and in this regard Linat

Tzedek decided to hang his picture in the society's club).

The extended committee of Linat Tzedek at that time consisted of the following:

Eliezer Kaplan (chairman) and Moshe Berger (deputy chairman); Michal Grycer,

Yitzhak-Hirsh Gliksman, Yitzhak Szaya, Yakov Bugajski, Zukan Szrajber, Chaim

Lustiger, Berl Cukerman, Zalman Zilberszac, Shimeon Gonszerowicz, Yodel (Yehuda

Ber) Davidowicz, Ahron-Wolf Szwarc, Zelig Cymberknopf, Elihu Grundman, Leibish

Zilberszac, Yehoshua Landau, Abraham Zarnowiecki, Yakov Chanitski,

Mordechai-Dovid Waldfogel, Shlomo Sobol, and Abraham Kamelgarn (secretary).

At the aforementioned meeting it was decided: A) to appoint Sol Greenberg as

the first honorary member of the Linat Tzedek society and to record the event

in the society's registry; B) to complete the Torah scroll writing project that

Linat Tzedek began before the First World War and had finished the fourteenth

sheet; C) to establish a permanent clinic near Linat Tzedek.

Linat Tzedek activists worked diligently to implement the decisions made, but

before a year had passed, times had changed, the plan had been shelved and it

would never be implemented…

|

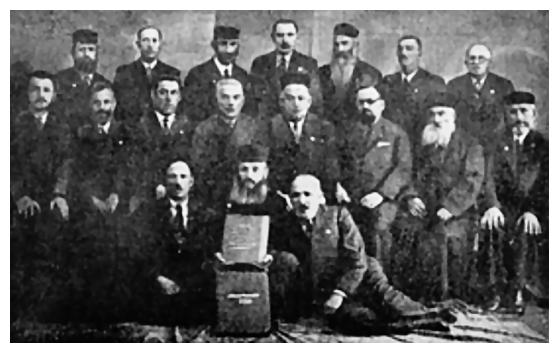

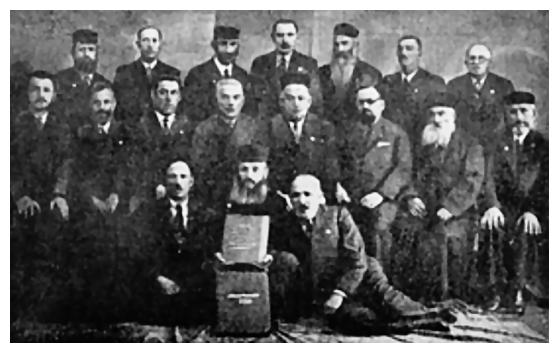

| Linat Tzedek committee

On top (from the right):

A. H. Gliksman, Shimeon Gonszerowicz, Chaim Lustiger, Yodel Davidowicz,

Zalman Zylberszac, Yehoshua Landau, Yakov Chenczinski.

Row 2: Y. Zarnowiecki, Zelig Cymberknopf, Moshe Berger, Leizer Rozanksi, E.

Kaplan,

L. Wlaszczawski,

Zukan Szrajber, A. Kamelgarn,

Seated: Berel Cukerman, Yitzhak Szaya, Mordechai Waldfogel

|

[Page 228]

Chevra Kadisha and Its Activists

by Yehiel Weintraub and Yosef Carmeli (Kamelgarn)

Translated by Sara Mages

A. Chesed Shel Emet[1]

Already in 5585 (1825), the Jews of Radomsk led their deceased for burial in a

neighboring town of Silmiershitz, but several years later a plot of land for a

cemetery was purchased within the city limits. The first sources regarding the

existence of Chevra Kadisha[2]

in Radomsk lead us to the year 5600 (1840). Among the first gabbaim of this

society were: Reb[3]

Meir Tyll, Reb Leizer Tentzer and others. The latter was a hotel owner, an

important Vurka Hasid, a respected man and a public activist. With the

establishment of the Zionist movement, Reb Leizer became a Zionist and

suffered because of his Zionism from the Hasidim. Being of strong character he left the

shtiebel[4] and didn't

return. However, sometime later, after the Hasidim came to appease him, he

returned to pray with them.

Chevra Kadisha had a decent income and was considered one of the most important

societies in the city. On 7 Adar, the day of the passing of Moshe Rabeinu, the members

of Chevra Kadisha used to fast and say Slichot[5].

At the end of the fasting they held an elaborate meal, during which they elected the first

gabbai[6].

The position was usually given to honest and prominent activists, who

knew how to manage the association affairs firmly and without discrimination.

They took a lot of money from the rich so that they could bury the poor for

free and grant them Chesed Shel Emet. The members of Chevra Kadisha stood the

test in their sacred work, especially in times of plague or war. The society

members risked their lives to bring those who died of contagious diseases to a

Jewish grave. They roamed the battlefields, examined the dead, removed the Jews

from among them, and buried them in accordance with Jewish customs.

Apart from the two aforementioned gabbaim were also the following activists:

Yakov Fridman-Kolton, Mendel Fajerman, Moshe Felman, Wolf Birnzweig, Mordechai

Gliksman, Shabtai Fajerman, Meir-Aharon Rudnicki, Pinchas Tzipler, Shmuel

Goldberg, Berel Kamelgran, Itche Tyll and others.

by Yehiel Weintraub

B. Gabbaim and those who serve in holiness

Reb Meir Tyll

One of the first gabbaim was Reb Meir Tyll (1840-1880). From his wife, Leah

Tyl, who lived long after her husband's death, I've heard a lot about his

activities.

At the age of twenty, Reb Meir devoted himself to social assistance activities.

He was the “address” for first aid, benevolence and Chesed Shel Emet.

He had a good heart and noble qualities, and in his role as the gabbai of

Chevra Kadisha he neglected his businesses.

Reb Meir Tyll was also the gabbai of Bikur Cholim[7]

society. He contracted typhus from a patient he visited and died of this disease in the prime of his

life. He was about forty years old when he died and left behind five young

children. After his death, Reb Moshe Fishhoff continued the role of gabbai of

Bikur Cholim, while Reb Mordechai Gliksman, known as Mordechai Skalka, was

elected gabbai of Chevra Kadisha. After him, R' Zev Wolf Birncwajg, who

established a special house of worship for Chevra Kadisha in the vestibule of

Beit HaMidrash, served in the position of gabbai.

Reb Kapel Shamash

The driving force in Chevra Kadisha before the First World War was Reb Kapel Shamash. He kept the

keys of the Ohel[8]

in which the Admorim of Radomsk: the authors of Tiferet Shlomo, Chesed LeAvraham, and

Knesset Yehezkel were buried. Every Rosh-Chodesh [“Head of the Month”] and the anniversary

of the death of aforementioned tzadikim[9],

Reb Kapel left his house with the keys in his hands to open the Ohel for the many worshipers

who came to pray at the graves of the tzadikim.

Also in the middle of the year Reb Kapel was asked to opened the Ohel in order

to pray for the well-being of a mortally ill patient. It was customary to

measure the Ohel with white cloth and distribute the measured cloth to the poor

– a remedy for complete healing.

Reb Kapel Shamash was an enthusiastic Zionist and fearlessly supported Zionism.

He bought the Shekel[10],

signed on shares of the “Jewish Colonial Trust,” and preached the idea of

Zionism to the Hasidim.

Reb Yakov-Yehoshua Zeligson

Reb Yakov-Yehoshua Zeligson was elected gabbai (1910) after the passing of Reb

Wolf Birnzweig. He was a Gerer Hasid, full of energy and good virtues. He

managed to reorganize and expand the framework of the operations of Chevra

Kadisha. He gathered the city's wealthy and distinguished to a meeting and

demanded that they contribute funds for the expending and strengthening of the

society. He also introduced “honorary memberships” in the society,

that is, members who were not actually involved in burying the dead, but only

paid membership fees (the “honorary members” were registered in the

society's register). Among the “honorary members” were: Daniel

Rozenboim, Shabtai Fajerman, Mordechai Goldberg, Itche Grunis, Yakov Fajerman,

Moshe Hampel, Moshe Fishoff, Nechemya Zandberg, Leizer Dunski, and Shlomo

Krakovski.

The active members of Chevra Kadisha at that period were: Dov Zionetz, Shmuel

Goldberg, Simcha Yeshaya, Meir Oberzanek, may he live long Aharon Oberzanek,

Pinchas Cipler, Berel Kanlgern, may he live long Moshe Binyamin Lihman,

Meir-Aharon Rudnicki, Kapel Schneider, Avraham Kamelgarn, and Avraham

Gerszonowicz.

One of the main activities of RebYakov-Yehoshua was the purchase of additional

land for the cemetery, and the erection of a protective fence (made of concrete

and bricks) around it. He also built a house at the entrance to the cemetery

which included: an apartment for a watchman, service rooms for those engaged in

burials, a purification room, a room for the study of Mishnayot and more.

Chevra Kadisha also provided extensive social assistance to the poor and needy,

despite the fact that it covered all the expenses for the burial of the poor

from its budget. Reb Yakov-Yehoshua also moved the house of worship to the city

center, to the home of Reb Nechemia Zendberg (I've heard that the house of

worship was registered as a donation for Chevra Kadisha). During the holidays

the “honorary members,” who contributed to the benefit of the

society, were invited to Chevra Kadisha's house of worship. HaRav Shlomo

Grossman was the society's regular reader of the Torah.

There was a custom in Chevra Kadisha to gather at the gabbai's house on Simchat

Torah and spend time there eating and drinking. Indeed, “drinking” in

Chevra Kadisha was not uncommon all year round. They drank and had fun together

on 7 Adar, Simchat Torah, Shavuot and Purim.

Reb Moshe-Itche the watchman

When the house was built at the entrance to the cemetery, they searched for a

candidate for the position of a watchman. It wasn't easy to find a suitable man

who would agree to live alone, about four kilometers outside the city. After

much searching, Reb Moshe-Itche appeared and offered his services as a

watchman. However, the gabbai demanded that he first marry a wife. Only after

the watchman found a spouse, he settled in his new place of

[Page 229]

residence. He received an apartment with all the amenities and a fixed monthly

salary. In the city they were pleased with this double “transaction”:

Reb Moshe-Itche's marriage and constant guarding of the cemetery.

During the First World War (1914-1917)

In the early years of the First World War, the hands of Chevra Kadisha were

full of work. Chevra Kadisha cared for Jewish soldiers who were brought dead

and wounded from the front. It was also necessary to patrol the surroundings of

Radomsk and to treat dead who were previously infected with infectious diseases.

In 1917, a typhus epidemic broke out in the city, and in the course of several

weeks there were about seventy deaths. The members of Chevra Kadisha, and Reb

Yakov-Yehoshua Zeligson as their leader, took care of the sick and the dead

with total devotion. On the eve of Rosh-Chodesh Nisan, all the members of

Chevra Kadisha left for the cemetery headed by HaRav Rabbi Yeshaya'le, son of

Rabbi Avraham-Moshe of Rozprza. After reciting Tehillim and a prayer to end the

epidemic, Rabbi Yeshaya'le spoke with emotional words and concluded with the

following: “All the Jews will mourn the fire, and I am willing to put out

the fire myself.” Two days later Rabbi Yeshaya'le suddenly passed away,

and the whole city wept bitterly because he was burned during the days of the

plague- fire, that he wanted to extinguish with all his soul and the fervor of

his faith…

by Yosef Carmeli (Kamelgarn)

Translator's Footnotes

-

Chesed Shel Emet (lit. “true loving kindness”) refers to acts of

kindness performed for the deceased, considered the purest form of altruism in

Judaism because the recipient cannot possibly repay the gesture.

Return

-

Chevra Kadisha (lit. “Holy Society”) is a Jewish volunteer

organization providing dignified end-of-life care, preparing the deceased for

burial according to Jewish law, and offering community support, and overseeing

proper burial customs. Return

-

Reb is a traditional Jewish title or form of address, corresponding to Sir, for

a man who is not a rabbi. Return

-

A shtiebel (lit. “little house” or “little room”) is a

place used for communal Jewish prayer.

Return

-

Slichot services are communal prayers for Divine forgiveness, said during the

High Holiday season and on Jewish fast days.

Return

-

Gabbai (pl. gabbaim) is a person who assists in the running of synagogue

services, or manage the financial affairs of an institution, such as collection

of contributions and keeping financial records.

Return

-

Bikur Cholim (lit. “Visiting the sick”) refers to the mitzvah of

visiting and extending aid to the sick.

Return

-

Ohel (lit. “Tent”) is a structure built around a Jewish grave as a

sign of prominence of the deceased.

Return

-

Tzadik (pl. tzadikim) a title given to people considered righteous, such as

biblical figures and later spiritual masters such as Hassidic rabbis.

Return

-

The Zionist shekel was a symbolic membership fee used by the World Zionist

Organization from 1898 to fund Zionist activities and grant voting rights for

Zionist Congresses. Return

The Jewish “Kehile”

by D. K-R

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

In the history of the Jews in Poland, an advanced self-managing committee

already existed as early as the 16th century – the Council

of the Four Lands (from 1580 until 1764, when the Polish Sejm

dissolved the institution). Later there was a Kehile in each Jewish

settlement, large or small, representing it both internally and externally.

The Kehile consisted of the Rabbi, shoykhetim, shamosim

and other clergy; it cared for the prayer house, the cemetery, the mikvah

and a Talmud-Torah where the children received an elementary religious

education. Worldly education was not then an issue.

In 1834 when the Tiferes Shlomoh was received as Rabbi, it was

necessary to have someone representing the Kehile in Radomsk sign

the rabbinic contract with its conditions of 15 Polish gilden

a week in wages and the like. Years later, the wealthy men Berish Ferszter,

Leizer Rickterman, Rajchman, Abraham Bem, Zylberszac and others who partly

lived in “Bugai” or in nearby Plawno demonstrated their interest in

the community needs of the Kehile. When the Tiferes Shlomoh

died, 29 Adar 5626 – 16 March 1866, the Radomsker cemetery was already in

existence.

Dovid Bugajski was synagogue warden when the city Shul was built in the

last decade of the 19th century and the foundation stones were laid

by Ferszter and Banker.

On the threshold of the 20th century, Reb Yosef Szac was the head

synagogue warden, Warszajnlech was the head of the yeshiva and his son

Asher was the secretary. The office of the Kehile then was in the market,

in Aba Szwarc's house and was not in a room in the Shul,

Reb Yosef Szac davened in shul together with the common people.

His place was near the Rabbi.

The representatives of the Kehile, though they were small in number, were

elected, even during the Czarist regime. Only the Jews who paid the Jewish community

tax, the special Kehile tax, had voting rights. However, there were very few of

these in Radomsk.

Later Leizer Tencer, Fishel Donski and others were elected to the Kehile.

During the First World War Fishel Donski led the Jewish Kehile. The

activities actually were not very numerous. They were limited to the

distribution of help to the needy Jews, such as potatoes, beans, salt and

sometimes sugar and the like. The means for acquisition of the products were

received from the donations of the well-to-do Jews and from the general city

help committee.

In the years after the First World War, when Poland received its independence,

a decree from Pilsudski was published in 1919 delineating the democratically

elected Jewish kehilus.

The democratically elected Jewish Kehile in Radomsk consisted of a

council with 12 members. The council elected a managing committee that

administered Kehile activities.

Women did not have any elective rights to the Kehile agencies.

The activities were limited only to religious needs – although according

to the decree, the Kehile also had the right to open schools, carry out

limited cultural activities, support emigration and so on. The communal and

party representatives in the Kehile agencies made an effort to expand

the activities on a wider communal basis that did not always succeed because

of both external disturbances and, even more, because of internal struggles

for party hegemony.

At the time between the World Wars, the following people were representatives

from political parties, economic organizations, Hasidic shtiblek

and so on: Haim Gelbard, Sh, Najkron, A.M. Waksman, A. Grosman, Sh. Krakowski,

Yosel Berger, Y. Fajtlowicz, B. Gonszerowicz, Fajerman, Wolf Frenk, Y.H. Tiger,

Yakov Gerichter, M. Wolkowicz, M. Kaplan, Wolf Szpira, M.A. Rajcher, Zuken

Szrajber, Abraham-Bunim Aizen, Fishel Pariz, Engineer Poliwoda, Ahron Gliksman,

H.L. Zajdman and others.

[Page 230]

2 community budgets for the years 1926 and 1927, which lie before us,

characterize the activity of the Kehile in Radomsk.

In the budget for the year 1927 we read:

Expenses:

- For the Rabbinate – rabbi, 2 rabbis [who decide religious questions],

shamos for the rabbi; total – 14,650 zl.

- Synagogue – Hazan , assistant, shamosim, bel-kura

(Torah reader), watchman, renovations, lighting, sewage, ethrogim and

other economic expenses; total – 7,150 zl.

- Office – salaries for 3 clerks, office heating, lighting, writing materials

and service; total – 7,870 zl.

- Salary for shoykhetim; total – 24,700 zl.

- Cemetery – gravediggers, tailors, watchman, shrouds for the poor and other

expenses; total –3,850 zl.

- Retirement – the widow of the Hazan – 750 zl .

- Subsidies: support fund – 6,000 zl.; teacher and students –

1,000 zl.; subsidies for the Talmud-Torah – 1,500 zl.;

registration fees for poor students in gimnazie – 600 zl.; Association

to Support Poor Pregnant Women – 30 zl.; children's home –

400 zl.; assistants to the academicians – 100 zl.; Keren Hasud

(Palestine Foundation Fund) – 100 zl.; purchase of sforim – 150

zl .; Lubliner Yeshiva – 200 zl.; Volumes of Talmud–100 zl.;

Yeshiva fund – 150 zl.; medical help – 1000 zl.; total

– 11,650 zl.

- Unexpected expenses – 2,100 zl.; total expenses – 72,720 zl.

Income:

Slaughterhouse – 53,404 zl.; Shul – 674 zl.; Cemetery – 4,000

zl.; Jewish communal tax – 14,642 zl.; total – 72,720zl.

|

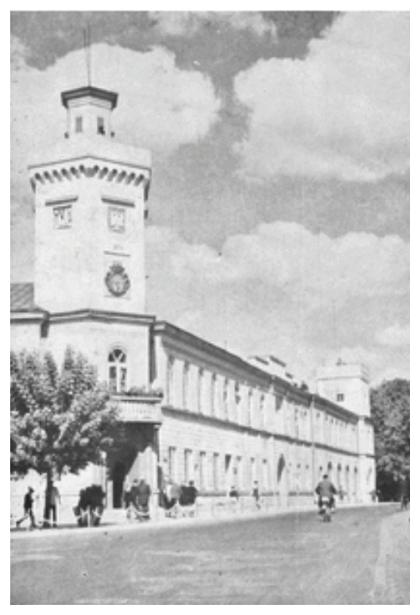

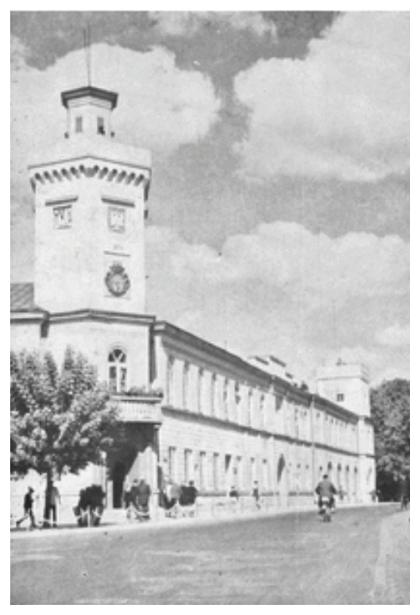

| The “Kehile” building |

The subsidy items, which make up about 15% of the budget, were however not

real, because in addition to the fact that the supervisory regime struck off some

items and there was a shortage of money, which is a chronic illness, many items

went unpaid.

The budget for the year 1927:

Expenses: Rabbinate – 15,250 zl.; Shul – 7,350

zl.; Office – 8,070 zl.; Slaughterhouse – 24,648 zl.;

Cemetery – 3,650 zl.; Subsidies and Retirement – 15,700 zl.;

Miscellaneous Expenses – 4,900 zl.; total – 79,568 zl.

Income: Shul – 744 zl.; Slaughterhouse – 49,697 zl.;

Cemetery – 4,000 zl.; mikvah – 960 zl.; Jewish communal

tax – 19,937 zl.; Earnings from matzoh flour – 4,200zl.;

total – 79,568 zl.

The Radomsker Zeitung of 16.1.1927 (January 16, 1927) notes about the customary

budget, “This budget was accepted by the Kehile council with the agreement

of 6 synagogue wardens, even though there was no quorum for all three readings.”

In subsequent years, the Kehile activity in Radomsk could not be separated

from the party of “blind believers” and the politics of the houses

of study. Besides, there were wardens found in the Kehile with a different

outlook on communal life. However, they were disrupted by the parties, such as

Agudah, Hasidic shtiblek and even individual Hasidim, who with the

help of the Polish regime, forced the transformation of the democratically elected

kehile again into a “warden-shtibl” that did not respect

the Jewish representatives.

In the R. Zeitung of 20.1.28 (January 20, 1928) we read, “Last week

the sick fund sold the furniture and the like from the meeting hall at a public

auction.”

The opposition – that is, all the elements that wanted to create from the

communal authority a Jewish representational organ that would deal with the

cultural and economic needs as well as the other problems of the Jewish

community – faced stormy meetings with passionate debates and nothing

could be accomplished.

The Zionist representatives were unsuccessful in having the Kehile

seriously deal with the Eretz-Yisroel problem, nor with the problems

of the state of the Radomsker Jews, both economically and culturally.

Almost all of the Kehile activity was concentrated around the

shoykhetim and the like.

The poverty of the Jewish population grew considerably. This forced the

community workers to distribute over 500 measures of coal and almost 2,500

kilos of matzoh on Passover.

Later Kehile budgets did not change, but again moved in the circle

of the Rabbinate: shoykhetim and the cemetery. This all had a negative

effect on the interest of the Radomsker Jewish population in the council. A reduced

Jewish communal tax flowed in, which had an effect on the payment of the

salaries of the rabbinate and the clerks, not to mention on the subsidies

approved by the regime.

[Page 231]

In the Radomsker Zeitung of 9.9.27 (September 9, 1927) we read:

“…then what did the council do for us during the time of its

existence? Its 'history' shows very clearly and distinctly that it did

not have greater scope than caring for the rabbinate, shoykhetim

and the like. For what use is the whole paraphernalia and hurly-burly? [What

has the council done for the city] when even today the council could not find

2,000 zl. with which to fix the roof of the Shul, through which

water pours and destroys the artistically painted ceiling—an

irreplaceable loss. Not to mention the building proper, which from

the outside already looks like a ruin.”

And further: “Therefore the Jewish population lost interest in our

'sovereign Jewish state' and thought it no more than a burden on their

shoulders.”

And so things went until 29.3.31 (September 29, 1931) when new elections were

held for the Jewish Kehile in Radomsk.

The Radomsker Zeitung of 29.5.31 (May 29, 1931) presents the

following list of the voting lists and their total mandates

(Translator's note: number of representatives elected):

| 1. |

Right “Poalei Zion” |

136 |

votes |

- 2 mandates |

| 2. |

Lodzer “shtibl” |

131 |

votes |

- 2 mandates |

| 3. |

Zionist block |

102 |

votes |

- 1 mandate |

| 4. |

Retailers |

242 |

votes |

- 4 mandates |

| 5. |

Artisans |

96 |

votes |

- 1 mandate |

| 6. |

Tomaszower “shtibl” |

67 |

votes |

- 1 mandate |

| 7. |

“Khevra Kadishe” |

38 |

votes |

- 0 |

| 8. |

“Agudah” |

166 |

votes |

- 3 mandates |

| 9. |

Aleksander “shtibl” |

73 |

votes |

- 1 mandate |

| 10. |

Butchers |

75 |

votes |

- 1 mandate |

| 11. |

Grosman's list |

73 |

votes |

- 1 mandate |

| 12. |

Left “Poalei Zion” |

59 |

votes |

- 0 |

And the newspaper notes: “From the above-mentioned list one can make the

following conclusions. The list of the Right P.Z. scored a victory.

The Zionist block, which was united with the Tomaszower shtibl,

can be considered satisfied because many Zionist voted for other lists such

as the economic and others. An unforeseen victory was scored by list 4 of the

retailers.”

The [membership] of the Kehileconsisted of the following persons:

Zuken Szrajber, Wolf Szpira, H.L. Zajdman, Kh, Jakubowicz, A.M. Waksman,

M. Berger, Y.Kh. Zinger, Sh.L. Witenberg, B. Gonszerowicz, M. Poliwoda,

Yakov Ofman, Yitzhak Szpira, Krakowski, Y.Kh. Tiger, Kotlewski, Yosef

Berger and Abraham Grosman.

In the above-mentioned newspaper of 17.7.31 (July 17, 1931) we read the

following appeal of the majority of the elected councilmen:

“On the 29thof May you gave a worthy answer to

those in the Kehile who bartered and forestalled for 7 years.

Thanks to your clear understanding and orientation, you elected people to the

Kehile from various directions and ideas, from all classes of the

population united in one goal, to cure and make healthy the economy of the

Kehile.

|

The delegation of the Jewish “Kehile”

(with the rabbi in front) during the general city celebration on the day of the Polish

national holiday of the 3rd of May.

From the right: H.L. Zajdman, Yosef Berger, Noakh Zoberman, Moishe Berger

(Kehile chairman), Rabbi Mendel Frenkel, Abraham Grosman, Y.D. Fajtlowicz, Yakov Ofman.

|

In this newly created situation, with the purest and most honorable

intentions, we are ready to offer our energy and effort and to fulfill the duty

which your 1,200 votes have imposed on us.”

The Agudah representatives, who had at their disposal the famous

Paragraph 20, according to which one could strike from the voting list

every Jew who is – according to their understanding – not

religious enough, could not withstand the strong anti-Agudah

pressure of the voters. A block of nationalist elements was created,

supported by representatives of the Jewish economic institutions.

The Radomsker Jewish community – simultaneously with all of Polish Jewry

– at that time, lived through one of the most difficult economic and

political times. The anti-Jewish politics of the Sanacja government

brought about an even more severe pauperization of the Jewish economic

undertakings due to the boycotts and the like. Alas, during its term in office

the Jewish Kehile did not stand on the appropriate level. Internal

party quarrels and the politics in the Houses of Study made it impossible

to raise the prestige of the Kehile. Very often various complainants

were brought before the regime and this led to new elections in 1936 that

did not really better the situation in the Kehile. Small changes were

made in the lists. Abraham-Bunim Aizen and others were elected from Right

Poalei-Zion.

Wanting to truly reflect the last years of the Radomsker Jewish community, we

have lingered on the communal atmosphere in our duly democratically elected

Kehile.

[Page 232]

In the General City Managing Committee

by D. R.

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

With the rise of independent Poland, in 1918, the idea of democratic municipal

elections matured. True, in 1914/16 in the time of the First World War during

the German occupation, voting to the city councils according to the system of

“political subdivisions” took place in the larger cities such as

Warsaw, Lodz, Częstochowa and others. Each layer of the population voted in

separate political subdivisions and the citizens in the last [or lowest]

subdivision did not have voting rights. However, in the Austrian General

Government, to which Radomsk belonged, no city council elections took place.

The mayor of the city was a nominee of the Czarist regime until the First World

War and of the Austrian managing committee during the First World War. The city

managing committee consisted of the mayor, and some citizens nominated as his

advisory council. Until the outbreak of the First World War, Mr. Gabrial

Goldberg sat on the council [as the Jewish representative]. He was called the

“Tzolnek” (corrupted from the Polish word “członek”

or councilman).

In general, at that time the activity of the city managing committee did not

have the form of today. No one thought about beautifying the city and no one

had the right. This was taken care of by the governor; it remained for city

hall only to collect taxes, to be represented at celebrations, which were

scheduled by the Russian regime. At the times of the “galuwkes

” (Translator's note: the birthday of the Czar or his family members), the

mayor put on his ceremonial Napoleonic hat with the two extensions in the front

and behind, bordered with golden ribbons and came to the school where the

children were assembled from the Folkes- School in rooms. The hazan

made the “Hanoten Yeshua” for the Czar and his family (Translator's

note: prayer for the Russian Czar found in old siddurs printed in Russia)

and the Imperial hymn, “ Khrani Tzarya Bozhe ” was sung.

In the city hall budgets of the time an entry appeared for “synagogue

surveillance.” The city hall, for example, sold the “pews” in

the Shul at an open auction, carried out by special clerks, and collected the money.

[The clerk] would also receive remittances of the accounts for kerosene,

candles and brooms from the Shul. Later, Mr. Avram'che Minski

sat in the city hall as an unpaid clerk who knew his way around the

books as well as the entire city hall and the mayor combined. This is

how, more or less, the city managing committee of Radomsk appeared

until 1919 when Pilsudski, as head of Poland, issued his famous decree

about democratic elections to the Polish municipal managing committees.

The Jewish population was presented with a new problem when an election was

scheduled to the first city council in Radomsk. True, in the prior years, the

communal and party life of the Jewish population was significantly developed,

particularly among the Jewish workers' parties. Then the campaigns needed to be

very intensive in order to make clear to the Jewish population the significance

of the elections for the local self-managing committees. Despite certain

unfavorable paragraphs in the election ordinances, the Jewish population

succeeded in receiving its appropriate representation in the first elected city

council in Radomsk.

|

| The building of the city managing committee (City Hall) |

The struggle between the right and left powers among the non-Jewish population

was also very bitter. The city council elections had to reflect the general

political situation, which then hold sway in Poland. The P.P.S. (Polish

Socialist Worker's Party), thanks to its energetic young professional

Mr. Lenk, and with the help of Jewish votes, received a majority in the first

city council.

Then a problem arose: who should be the first mayor in the democratically

elected city managing committee? The only candidate of the P.P.S.

was the young Starostecki, a son of a peasant, who on the way to becoming a

priest, became a member of the P.P.S.

[Page 233]

However, when the office was proposed to him, he declared that in his

opinion, the mayor of the city needs to be a patrician “ mit a beikhl

” (with a belly) and not him, still a young man.[a] In the end he undertook

the office and was elected as the first mayor of the democratically elected

city managing committee in Radomsk.

The Jewish population had also received 1 representative in city hall (lawnik

– alderman). However, this did not impede the rightist Polish elements,

with the Endekes (National Democratic Party) at the head, from carrying

out their anti-Semitic activities and anti-Jewish course. Also, one cannot ascribe

any recognition of Jewish needs and desires to the P.P.S.

In general, the political situation in Poland was far from stabilized.

Immediately after the War, Poland again became entangled in a war with the

young Soviet regime. The internal political quarrels for hegemony over Polish

life were then clearly reflected in the local political life of the city

managing committee.

In the coming elections to the city council, the general picture was very

different. The rightist elements won among the Polish population and their

leader, Mr. Szwadowski, was elected as mayor. Self-evidently, the activity of

the city managing committee at that time was very adversarial vis-à-vis

the Jewish population.

A very characteristic fact of that time is worth recording:

Leizer Gliksman, a volunteer in Pilsudski's Legion, noticed that Pilsudski's

picture hangs in the city hall without a [covering] glass. His application to

the Endekes lawnik that he should receive permission to put a glass

on the portrait at his own expense was sent to the mayor. The latter

declared to him, “Pilsudski is a mutineer; you can throw his

picture in the garbage.” When Mr. Lent related this fact at a mass

meeting of Polish labor, they began chanting, “Hang City Hall!”

In 1926 the May coup d'etat by Pilsudski changed the political

situation in Poland, so that in 1927 elections were held again for the city

council, for the first time in June, which were immediately annulled and

for the second time in December.

7 Jewish councilmen were elected in June out of the total number of 24 and, in

December, Yakov-Shmuel Haze, Yeshayah Rozenblat, M. Poliwoda, Dr. Glikman,

Ruwin Najkron, Dovid Sobal, Dovid Bugajski and Yitzhak Szpira. The Bund

lacked a few votes to win a seat and the block of the right Poalei-Zion

and the artisans lacked several votes for a second candidate.[b] (The right

P.Z. remained without a seat.)

According to the party list the elected city council presented this picture:

P.P.S. – 9 seats; Endekes – Civil Jewish Block

– 4; Impartial Jews – 2; Left P.Z. – 2.

After very long negotiations, the candidate of the P.P.S., Dr. Fejdak, was

elected as mayor, Mr. Kazielo as vice mayor (also P.P.S. lawnik) and Mr.

Cigonkewicz and Mr. Haze of the left Poalei-Zion (the 4 people constituted

the municipal authorities). It is interesting to add that the Mr. Najkron, who ran

on the list of the rightist Polish councilmen as lawnik, had questioned the

election of Mr. Haze as lawnik and reported the matter to the higher power,

which in a later term confirmed Mr. Haze as lawnik (this means the members

of the city managing committee).

Unzer Zeitung of 23.3.1928 (March 3, 1928) relates an interesting “language

struggle” among 2 Jewish councilmen – the lawnik Haze and

Councilman Najkron:

“When Mr. Haze read aloud his political declaration in the name of left

P.Z. and demanded among other things – the right for Yiddish in the municipal

offices, and the like, and after that began reading the same declaration in

Yiddish, the rightist Polish councilmen made a great racket. The chairman

stopped the reader with the observation, “Although each nation has the

right to use its language among itself, Polish is the official language in the

city council.”

Later we read in the Zeitung:

“Councilman Najkron engaged in polemics with Mr. Haze that the question of

the 'mother tongue' Yiddish has so far not been taken care of because a large

part of the Jewish population believe that Hebrew is the mother tongue.”

Despite the leftist majority in the city managing committee, the struggle for

Jewish representation was not a small one. Disregarding all of the promises

about subsidizing the Jewish institutions through the city managing committee,

certain arguments on principle were taken advantage of using the name

Talmud-Torah and the like, with which the leftists could not agree.

|

Summer colony of Jewish children

supported by city hall (1930), the Jewish

lawnik Yakov-Shmuel Haze is standing in the center |

[Page 234]

Sometimes there was success through a joint struggle of all Jewish councilmen, to

achieve small subsidies for Jewish educational and cultural purposes such as for

active institutions. However the supervising regime over the city almost always

turned down or decreased these subsidies.

According to the above-mentioned newspaper, the struggle between the leftist

and rightist Jewish councilmen did not create respect for them among the Jewish

population. Protest meetings even occurred against those Jewish councilmen. We

record this only in order to show the “ardor” of the Jewish

councilmen in defending the rightist or leftist “principles” of their

block partners.

The Radomsker Zeitung of 8.3.29 (March 8, 1929) brings the following

statistical numbers of Jewish subsidies: Talmud-Torah – 1,500

zl.; Interest-free loan fund – 1,000 zl.; Beis-Yakov

school – 250 zl.; Children's Home – 2,000 zl.;

Association for aid for child birth – 1,500 zl.; Histadrut

Library – 300 zl.; Artisan's Library – 650 zl.;

Sholem-Alechim Library – 300 zl.; Library for the evening

courses – 650 zl.; YIVO in Vilna – 350 zl.;

and assistants for the academicians – 250 zl. Total – 7,750

zl. (from a general budget of 768,417 zl.)

Alas, the above-mentioned subsidies were decreased by 3,000 zl. by

Sejm circles. The above-mentioned newspaper presents the speeches

about the matter by Mr. Najkron and Mr. Haze. Mr. Najkron shows that, “The budget is

actually only a party budget. 85% of the three hundred thousand zl. that

the City Hall receives from taxes are from Jews. And yet, the Jewish population

receives only groshns (pennies) for their institutions.”

|

The Jewish Committee that

carried on general money collections for strengthening

of Polish military aircraft before the World War (1939) |

Mr. Haze, in his budget speech, indicates the great injustices that the city

managing committee committed in relation to the Jewish population, “All

talk of equivalence, but in reality it seems very tragic. Of the total of 90

lists in the city managing committee, only 4 are Jewish, including in the

account the Jewish teachers who work for pennies. We had counted on our

Christian Socialist comrades to understand us. We are until now

disappointed.”

The speaker argues with those who say that, “The Jewish workers are not

accustomed to working.” He says, “In many nations such as France and

others, Jewish workers work in coal mines and the like and if this is not

enough, go to Palestine and you will be persuaded as to how Jewish workers

work.”

He requests that only the wealthy should pay taxes and the poor should be freed

completely from paying taxes.

In 1930 Dr. Fejdek was appointed as mayor of Radomsk. Elections to the

Radomsker City Council were supposed to be held again on the 1st

of March, 1931. The Polish population belonged to 2 blocks, P.P.S and

all of the rightist Polish parties, such as N.D. (Endekes), K.D.

(Christian Democrats) and even the B.B. (This is the party of the regime

since Pilsudski's coup d'etat in May 1926). The opposition among the

Jewish population was splintering. Mr. Haze moved from the left P.Z.

to the Bund and headed their list and so on and so one. However, at

the last minute the elections were cancelled and a government commissar

was chosen – Mr. Siman, the leader of the local B.B.

This meant that the city managing committee was led according to the general

policies in the country, in the anti-Semitic direction of Skladkowski's “

Owszem” (“Of course” – Translator's note: This is understood to

have indicated approval for economic discrimination against Jews), the super

anti-Semitic OZN (United National Camp) and the like. So, for

example, we read in the Radomsker Zeitung, “As it should not

be, if by intention or by chance, the status quo of the Russian times is now

put back in place. In the local city hall, except for Mr. Abraham'che Minski,

there are no longer any Jewish clerks working there. The new management

has removed Mr. Horowicz from his spot.

Until now we have dwelled upon only the Jewish situation in Radomsk in

connection with the local municipal regime. For the of city Radomsk, without

doubt, the last mentioned city managing committee since Polish independence of

1918 was a great boon. The city took on a different appearance. Many gardens

and park were added. The network of schools was widened; the same with living

quarters and the like. Alas, the Jewish population benefited very little from

all of this. Just the opposite, no one in power, not in Poland in general, and

not in Radomsk in particular, took care of the needs of the Jewish population.

And not least, the last people in power, as we recorded above. In the time

before the outbreak of the Second World War, in the time of the Beck-Hitler

agreement, they literally drooled with enthusiasm from the accomplishments of

the anti-Jewish realm of their German partners. The ruling Sanacje regime tried

in all ways possible in its anti-Semitism to surpass even the sworn

Endekes and the most brutal “narodowces (nationalists).”

In turn there was an increase in the anti-Semitic tendencies and anti-Jewish

policies in economic realms.

[Page 235]

The boycotts, pickets and [actions against] the market stall keepers even

led to pogroms in Jewish cities. This did not deter the policies of Ridz-Szmigli,

Skladkowski and Colonel Kac. Not only did they revel in the police commissioner's anti-

Shikhita (ritual slaughtering) statutes, but openly preached that anti-Jewish

regulations must be introduced in Poland.

All of this, on the eve of the Second World War, darkened life.

Original Footnotes

- Related by someone who took part in the delegation. Return

- Although in June the Right P.Z. itself elected a councilman. Return

The “Khevra-Kadishe” and Its Workers

by Y. Lachman and Y. Rudnicki

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

a. “Khesed shel Emes”

(Trans. Note: society that buried the deceased poor)

The Khevra-Kadishe was always one of the most necessary [organizations]

for the Jews, if not the most important institution in the Kehile.

This society was the first that arose in every Jewish settlement, at the very

start of its development, often even before there was a cemetery in the area.

Later, when it was necessary to take the remains for burial in a nearby

shtetl, several Jews were always found who knew the “laws of

purification” and gave the corpse its “rights” on the spot

and then took it to the nearest settlement for burial.

In general, the Pinkes (book of records) of the Khevra-Kadishe

with its entries and regulations was always important material for historians,

to learn the history and way of life of the Jewish kehilus. The Radomsker

Khevra-Kadishe, of course, had its Pinkes and traditions. Alas, the

Pinkes disappeared, together with the Khevra-Kadishe

and with the whole Jewish settlement. We bring, therefore, only a few memories

that we have gathered together about this society in the last era.

The Khevra-Kadishe in Radomsk consisted of three groups of members:

those who prepared the dead for burial, tailors and honorary members. The

foundation and mainstay of the society were those who prepared the dead

for burial. On them lay the duty of ritual purification and all of the work that

had a connection with the funeral and burial. It was necessary to always have a

Ben-Torah (Jewish scholar) among the group, knowledgeable in all of the religious laws

and customs that needed to be observed – from the agony of death to the

covering of the grave. Therefore, he also had to know the prayers said for the

dead and every custom that had taken root in each particular city. Besides

this, among this group there also had to be people with physical strength

because the work was hard.

The largest number of those who prepared the dead for burial were simple

middle-class Jews, mostly craftsmen who did the work of the

Khevra-Kadishe as a mitzvah, often literally with self

sacrifice. The work was especially not easy when one had to carry

out the ritual purification in the cemetery, in the ritual-cleansing house.

In general, the purification was carried out in the home and to the honor

of the deceased. Only in the case of a corpse that had to be buried

at the cost of the Kehile or when a Jewish stranger accidentally

died in Radomsk, was the ritual purification carried out in the cemetery.

There was a ritual-cleansing house, but the instruments and the other things

needed had to be brought each time from the city. Those doing the ritual

cleansing had themselves to bring them and carry them several kilometers

on foot.

The ritual cleansers were always ready to fulfill the duty, which they had

undertaken. They would leave their work and livelihoods each time without

complaints to carry out the mitzvah. More than once they came

several kilometers to the cemetery on foot during a heavy frost and worked

physically hard there. Frequently it was necessary to use axes to soften

the ground in order to bury the deceased. Often the diggers had to be

replaced. The digging of the grave lasted many times until late in the

night. In such a case, the outsiders, in general, would leave because the

frost burned. However, the family of the deceased and almost all of the

Khevra-Kadishe members would always remain on the spot because

one could not permit the burial to be delayed and the “covering

of the grave” to be carried out without a minyon.

In the last era, the matter of burial in the large cities was modernized

through the introduction of special instruments and the hiring of people for

the ritual purification. [In the large cities] there was not strong insistence

upon [carrying out of] all of the customs, mainly for the uncelebrated Jews. In

Radomsk, however, every case of death was a city occurrence because one knew

every person and as a matter of course, the matter of the accompaniment of the

deceased to the burial took on a familiar character. There could not be any

talk about giving up or making things easier in matters that were connected to

respect for the dead.

The second group in the Khevra-Kadishe was the tailors, who sewed the

shrouds for the deceased. They, too, did not take payment for their work. The

tailors were also those who at the conclusion of sewing the shrouds took

part in the ritual purification and in the burial.

[Page 236]

Among the ritual cleansers and tailors of the Khevra-Kadishe in the

era from the First to the Second World War were the following: Yakov-Yeshoshua

Zeligman, Yehezkiel Shoykhet, Yitzhak Bendlemakher [ribbon maker], Henik Wajs

(Henik-Fishel Kotzker), Moishe-Benimin Lachman, Yakov-Dovid Fajtlowicz,

Shmuel Zajnwel (fisherman), Abraham Lederman (the lame Yekel's son-in-law),

Yisroel Waldfogel, (Yisroel, Kohan Godl [high priest]), Y. Brener,

Abraham Gerszonowicz, Meir Beker (the father of Leibel Gerszonowicz,

the head of the yeshiva, Keter-Torah [a Yeshiva] in Częstochowa),

Dovid Zajanc, Yitzhak Ofman (butcher), Shlomoh Cwyling (glazier), Feiwel

Farzenczszewski (tailor), Szaja Kamelgarn (tailor), Meir-Ahron Rudnicki

(tailor), Pinkhas Cypler (tailor), Haim-Yekel Goldner (tailor), Mordekhai

Gliksman (Skalke*), Shmuel Goldberg (tailor), Kopel Szneider

(grave digger) Yekel “Ranic” (tailor), Hersh-Leib

“Teper” (tailor), Yosef “attendant” and others.

(*Translator's note: Skalka is a Polish word meaning flint;

the pronunciation in Yiddish is skalke. There is no indication

why Mordekhai Gliksman had this nickname.)

The honorary members were not called for any “unskilled labor.” They

themselves reported only in exceptional cases, for a distinguished deceased. In

the last years registered in the Pinkes as respected Khevra-Kadishe

members were the Radomsker Rebbe Reb Yisroel-Pinkhas Hakohan, Reb Yisroelke

Zelwer, moreinu vtzadik (revered teacher), Reb Ithamar Rabinowicz,

Shmuel-Meir Fajerman, Daniel Rozenbaum, Yakov Rozenbaun, Shabsi

Fajerman and others.

The Radomsker Khevre-Kadishe showed great self-sacrifice, valor

and great devotion during the time of the First World War, when the great

battle in the fields between Brzeznica and Radomsk ended. Groups of

Khevre-Kadishe members would set out in peasant wagons, in the dark of night, and, on the

fields sown with slain bodies, search for fallen Jewish soldiers, in order to

give them a Jewish burial in the Radomsker cemetery. The work was done without

the knowledge of the regime, sometimes under a hail of bullets. Many such

graves were on the Radomsker cemetery, covered with simple stones, as a sign

that here lies buried a Jewish soldier. On some of the graves was the

inscription: “Here is buried a soldier whose name is unknown,”

sometimes with the inscription, officer or non-commissioned officer, if that

could be clarified during the burial.

A second chapter of the devotion of the Khevre-Kadishe in Radomsk

was written in the first years of the First World War, when typhus

raged in the Radomsker area, as in all of Poland at that, consuming hundreds of

victims from the Jewish population. At that time the number of funerals in the

city reached ten in one day. Ignoring the danger of themselves becoming

infected with the terrible illness, the Khevre-Kadishe members

stood the whole day, many times until late in the night and worked

with the ritual cleansing at the burial of the dead. On a yom-tov

when others sat at the table with their families and partook of the joy of a

holiday festival, the members of the Khevre-Kadishe were called

away from their families more than once for the purification and

burial of deceased Jews.

Alas, several people did not always properly appreciate the difficult and

important work of the Khevre-Kadishe. There were always jokes

in the city about the “great feast” that the Khevre-Kadishe

would celebrate on the 7th day of Adar and over the “drink

of whiskey” that they sometimes took.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the gabai of the Khevre-Kadishe

was Reb Zev-Wolf Birencwajg, not a Hasid. After him, the gabai was Reb

Moishe Pelman, a Hasid and a learned man, who was very respected in the

city who managed the Radomsker cemetery with great judgment. After him, the

gabai was Reb Yakov-Yehoshua Zilegson, a Hasidic businesslike Jew.

During his time, the Khevre-Kadishe was strongly disciplined.

He had a strong hand and was fastidious about every

trifle. He also firmly led in regard to the burial ground and a grave for a

corpse was given according to his discretion, without consultation with anyone.

He, therefore, more than once, brought down wrath on himself on the part of

relatives of the deceased. However, he did not consult anyone and had no fear.

The regime over the “Kingdom of Death” of Reb Yakov-Yehoshua ended at

the moment when the Kehile took jurisdiction over the cemetery. From then

on the matter of cemetery plots and money was taken care of by the Kehile.

The gabai and the Khevre-Kadishe no longer decided the prices of

the graves and to whom to give an honored place on the cemetery. The

Khevre-Kadishe thus lost the absolute rule over the deceased and was

only a functional institution for the Kehile managing committee. Despite this, the

Khevre-Kadishe members carried out their duty perfectly, voluntarily and only as a

mitzvah, although their power was broken. From time to time various frictions would

break out among them and the Kehile managing committee. It even led to a

strike, but this was a strike with small demands. It concerned the several percent, which the

Khevre-Kadishe would receive for a rich man's funeral, for their receipts or because the

leaders of the community were snubbed by the Khevre-Kadishe. These strikes

were always quickly ended and the Khevre-Kadishe members again

were occupied with accompanying the deceased to their eternal rest.

The Khevre-Kadishe also had a prayer house. In the early years the members

davened in an anteroom of the Kehile's Beis-Midrash. Later they moved to their own

shtibl, which was located in Nekhemya Zandberg's house (on Reymonta Street, number 8).

b. Matter of Ritual Cleansing and Burial

The majority of members of the Khevre-Kadishe were tailors,

both for men and women (shrouds had to be sewn for women, too).

There were groups of members from the strata of the so-called fine Jews,

Hasidic businessmen. However, the majority of members of the

Khevre-Kadishe, those who carried out the holy work with

the corpse – those who prepared the dead for burial –

were craftsmen and simple businessmen. Honorary members were

the Rabbi of Radomsk, rich Jews and scholars. However they very

seldom took part in the practical work of ritual cleansing. When the deceased

had actually belonged to the Kehile, it was necessary to deal

with the opinion of the Khevre-Kadishe when, after one hundred

and twenty years, it was necessary to come to them. Working for the

Khevre-Kadishe was voluntary. The craftsmen who themselves

were not wealthy people would always put away their work and

willingly go to their holy work with the deceased. Even when this was on a

yom-tov (the funerals took place on the second day of a

yom-tov). The management, the direction lay in the hands of the chairman, the

gabai. What I remember is from 1900; the gabai was Reb

Mendel Fajerman.

[Page 237]

His members were: Mordekhai Gliksman (Mordekhai Skalke),

Meir-Ahron Rudnicki, Haim Yakov Wasele, Yosef Sapkower, Abraham Leizer

Kamelgarn, Shmuel Goldberg, Pinkhas Cypler and others. As soon as a Jew died,

the Khevre-Kadishe was called to take the deceased off of the bed and to lay a few pieces of

straw under him. Later they carried out the ritual purification and burial in

the indicated spot. Naturally, when it was someone rich or an eminent

businessman they received a better grave nearer to the graves of the rabbis.

When a pious Jew died or even an eminent businessman, the honorary members of

the Khevre-Kadishe came to the ritual purification. Or when a Rabbi died, then those who prepared

the body for burial were, naturally, eminent Rabbis. However, the local

Khevre-Kadishe was always included, so that G-d forbid, they were not humiliated.

The only reward for the Khevre-Kadishe members was that they had their own shtibl

in which to daven and for time to time they made a kiddush after the davening,

mainly on Simkhas-Torah. Then one keg of beer went after another, it should be understood with

chickpeas and herring. Right after the davening and after the circling with the Torah

in celebration of the completion of the yearly reading of the Torah, a real L'chaim

was made, followed by honey cake and the receiving of a Havdole candle braided in

several colors, which was used for the conclusion of Shabbos. Then in an exalted mood, the

gabai would be chosen for the next year.

As a rule, the gabai would determine the price of the cemetery lot, or when a rich man died, several

businessmen would come together with the synagogue warden, Mr. Yosef Szac, or

with Dovid Bugajski, and determine the price. How the deceased led his life was

taken into consideration, if he had given tzadekah and the like. There

was a case when a corpse lay for several days because the

children were stubborn and did not want to give the sum that commission had

determined. However, they paid and the burial was carried out. It was also the

custom in Radomsk to make 7 circles with the deceased around the open grave.

This was carried out by the member of the Khevra-Kadishe. Many times

they would also, right after the burial, make a L'chaim

with 95 proof whiskey in order to “come back to themselves,” as it

would be explained.

Many of the tailors who sewed the shrouds for the dead made witty comments

about the deceased being an “obnoxious customer,” but that this time

there would be no complaints. Everything fit in the best order.

There was also a special woman's section in the Khevra-Kadishe,

which did the holy work when a woman died. The women members for the

Khevra-Kadishe, just like the men, were very respected women

in the city and devotedly fulfilled their mission.

My father Meir-Ahron Rudnicki, of blessed memory, carried out the holy work as

an active member of the Khevra-Kadishe for scores of years, until the

Hitlerist assassins annihilated it along with along with all of the Radomsker Jews.

| Yehezkiel Rudnicki (New York) |

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Radomsko, Poland

Radomsko, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Max Heffler and Osnat Ramaty

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Jan 2026 by OR