|

|

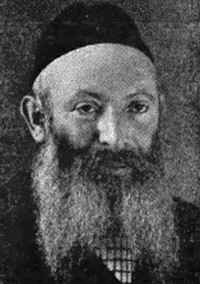

Shochat and Cantor

his wife

|

|

[Page 132]

by Reuven Yamnick

Translated by Marshall Grant

© by Roberta Paula Books

Dedicated to the beloved memory of my dear parents, brothers and sisters who were murdered by the Nazis and their associates during the Holocaust.

My father, Shmuel Halevi, shohat (ritual slaughterer) and cantor, of blessed memory.

My mother, Sarah Rachel Albert, of blessed memory.

My brother, Yaakov Yitzhak, his wife, Leah, and his family, of blessed memory.

My brother, Shalom, his wife, Malka, and his family, of blessed memory.

My sister, Chaya Devora, her husband, Yisrael Mandlboim, and her family, of blessed memory.

My sister, Royza Leah, of blessed memory.

My father, Rabbi Shmuel Yamnik, of blessed memory, was a shohat (ritual slaughterer and examiner) and cantor in our town of Przedecz for more than 40 years. He lived his life with holy adherence to Derech Eretz (treating others with respect) and Torah, as said by Rabbi Eleazar Ben Azaria, “If there is no Torah, there is no Derech Eretz, and if there is no Derech Eretz, there can be no Torah, because it is Derech Eretz that supports the Torah, it completes it”. This is the way he educated his children, to love the Torah, to love the People of Israel, to love the land of Israel, and to be civil and courteous to his fellowman.

My father was born in Rawa Mazowiecka to his father, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, the shohat and cantor in this city, and to his mother Beyla, on the 23rd of Elul, 5632 (September 26, 1872). He was named Shmuel on Sunday, on Rosh Hashanna 5633, when the maftir of Shmuel the Prophet was read (this I heard from my late father).

My mother was born in the city of Grodzisk, near Warsaw, to her father, Rabbi Yehuda Albert, and her mother, Rivka, in 5642 (1882). My father, as a young yeshiva student, was accepted to the position of shohat and cantor in our city of Przedecz in 5650 – 1900, by Rabbi Moshe Chaim Blum, who later became the rabbi of Zamość, near Lublin. My father later became the shohat under Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel and Rabbi David Goldschlak, the latter would become the rabbi of Sierpc. My father continued working with Rabbi Yosef Alexander Zemelman, the last rabbi of the town during the Second World War, who fell fighting the Nazis in the Warsaw Ghetto.

My late father was studious, devout, modest, humble and good–hearted; he was hospitable and loyally served the community of Przedecz. He enjoyed the fruits of his labors, loved Israel and was a follower of Amishnov Hassidism. He frequently visited the Great Rabbis (Admorim) Rabbi Yaakov David and Rabbi Yosef. He studied with Rabbi Yaakov David, who was the last Admor in Amishnov, and before that the rabbi of Żyrardów, near Amishnov, and in the city of Grabów near Kolo (not far from Przedecz). I remember when the Admor, Rabbi Yosef, visited his son, Rabbi Yaakov David in Grabów. On a Friday in the 1930s, my father decided to travel to Grabów for Shabbat and welcome the Rabbi. He leased a wagon and we left. For some reason we traveled on a dirt road;

[Page 133]

it was very muddy (it was right after the Passover holiday), and the horse could barely pull the wagon. We were concerned that we could desecrate the Sabbath. After a tumultuous journey, we were able to reach Grabów in time, and even managed to dip in the mikveh (ritual bath). Later, when my father met the great rabbi, he said, “Shmuel, I knew you would come – and I even asked here, has Shmuel the Shochat from Przedecz arrived yet?” And that is how we leisurely spent the Shabbat with Rabbi Yosef. My father was a friendly and pleasant person. During World War I, a large number of Jewish refugees arrived in our city after their escape from Lodz. They were escaping the hunger that prevailed at that time in the larger cities, and many found refuge in our city. Everyone did the best they could to help refugees and their families and provide shelter in their homes. My father was no different; he gave one of the two rooms we used for bedrooms to a refugee named Fried, a cobbler

|

|

|||

Shochat and Cantor |

his wife |

by trade. Despite the apartment's congestion from the many small children in the family, he was very satisfied that he could help a Jewish refugee recover financially by sharing the apartment and enable him to go out and work to earn a living for his family. They owned a hand–operated mill for grinding flour. He also sporadically worked as a cobbler and he was able to somehow survive. After the war, when the refugees returned to Lodz, we visited this family several times – they lived at 12 Wolborska Street. There were times when poor Jews came to raise money to go to Israel, and my father would accompany them to wealthy Jewish homes to help them with the fundraising. Among them was a young Jewish man from the city of Złoczów whose business had burned down and was requesting to come to Israel, and who was eventually successful in doing so. This man was

[Page 134]

well known in our city, and I often saw him leading prayer sessions as the cantor, chanting the first Selichot prayers. His business would often take him to our city, and he was pleasant to listen to. After he decided to move to Israel, he came to our city to collect money for his journey, and my father helped him as best he could. After the war, when I came to Israel as an illegal immigrant, I met this pleasant man and he shared many good memories of my father: his character and his hospitality. In our city, my father served as the ritual slaughterer and examiner, the mohel, cantor and Torah reader in the synagogue every day of the year. He would sound the shofar on Rosh Hashana and lead the High Holiday prayer sessions. On Yom Kippur, he would lead the Kol Nidrei and musaf prayers, and if the rabbi was unavailable, also the closing prayers. His voice was strong and pleasant, and he made sure his voice would also be heard in the women's section. After being accepted to be the ritual slaughterer and examiner in our city, he served together with the old cantor, Rabbi Shabtai Kotak, who was then the cantor and shohat. When Rabbi Shabtai passed away, my father worked by himself for a long period of time until a replacement was found. Graberman was from the German city of Fürth and a good cantor, but he never imagined remaining in Przedecz. He expressed many times that this was only a transition point for him. And sure enough, after a short time, he moved to Szydłowiec as their cantor and ritual slaughterer and examiner. That again left my father alone in his position until the community was wiped out by the hateful Nazis. When he worked alone, he worked very hard, for many hours a day and without any time restrictions, from early morning until late at night. At sunrise, he was already on his way to the slaughterhouse – to slaughter the cows, and then the chickens. There were no limits to how long he would work, just morning to night, and he always fulfilled his position with loyalty, without complaints or grievances. This is because he knew that the holy work needed by the city rested on his shoulders as there was no one else to help him. For many years the city did not have a designated slaughterhouse for cows and chickens and each local butcher had their own in their yards. We had a small slaughterhouse for chickens in our yard. And just several years before the outbreak of the Second World War, a large and official slaughterhouse was opened by the local Polish Authorities in the yard of Rabbi Haim Zomer. This was very advanced for those days, with more conveniences for the butcher and slaughterer. There were also better sanitation conditions with constant supervision by a Polish veterinarian. There were specific hours in the morning allocated for the slaughter of cows and specific hours for chickens. When the chicken slaughterhouse was in our yard, it was very popular, especially when the women would buy chickens in the market and immediately come over to slaughter them. It was the same on Wednesdays and Thursdays before Shabbat or during the week before a holiday. The yard was full of women and children who brought their chickens for slaughter, and there were even times people had to stand in a long line. In the week before Yom Kippur, during the 10 days of repentance, the demand was even bigger because each person brought kapparot (traditional atonement ritual in which a chicken is ritually used and then slaughtered) and each brought several chickens for food. During these times the slaughtering work would continue until late in the evening. The night before the day Yom Kippur eve began, my father walked with the shammesh (synagogue caretaker), Reb Itche Kovalsky, to homes who adhered to the tradition of waving a chickens above the heads of the home's residents in the morning before the holy day. And so, my father was busy all night with the slaughter of kapparot until the sun rose in the morning before Yom Kippur eve and he would return home tired and exhausted. However, there was still a busy day ahead. There was no more slaughtering work, but he had to prepare for the holy day and lead the prayers in the large synagogue, on the morning before Yom Kippur eve began. He went

[Page 135]

to the synagogue for morning prayers, and after eating and resting shortly, he went to the mikvah and prepared for his day of holy undertakings. In the afternoon, he went to synagogue for afternoon prayers, and after the pre–fast meal, he blessed the children and went to the synagogue to lead the Kol Nidre prayers. The next day, on Yom Kippur, he prayed the morning and musaf (additional) prayers with the choir, composed of the Vishinsky brothers, Herschel, Zelig, Simcha, all led by their older brother Reuven. All had sung in the past with the old cantor, Rabbi Shabtai Kotek. My brother, Yehoshua, and myself were helped by him (I don't understand this – how were they helped by him? Is this what you meant?) during the high–holiday prayers.

My late father was an enthusiastic Zionist. At that time, this was courageous and risky for a devout Jew, especially a religious representative such as the shochat, but he was unwavering in his desire to move to Israel. However, he never realized his dream and sent my brother Yehoshua to a Hapoel Mizrakhi kibbutz to be trained, as was done in those times. After several years of training, he received his certification and moved to Israel in 1935. His education for the love of Zionism was provided by my father. In his youth, in the house of his aging father, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, he joined the Agudat HaElef Group that purchased land in Israel in the village of Ein Zeitim near Tzfat, with the hope of immigrating with his family and settling in Israel. However, the Group lost much of its capital in unsuccessful investments carried out in connection with the estate. It disbanded, and only three hundred people continued with this task, my father among them. It eventually completely disbanded, and all the efforts and funds he invested were lost; all that remained were the documents and receipts he held for the payments made, but he was never able to move to Israel.

During Nazi control, kosher slaughtering was completely forbidden, and anyone caught carrying out this practice would be put to death. My father endangered his life more than once by secretly going to Jewish homes with a knife under his arm to quietly slaughter the hidden chickens and provide them with kosher meat. This continued until the curtain fell on the Jews of Przedecz, and together with the entire community he had served for more than forty years, he was sacrificed, along with my mother. All the Jewish men, women and children, were destroyed and burned in the Chelmno death camp. We will always remember our loved ones, their lives and their deaths. May God revenge their pure and holy souls; may their memories be blessed and their souls bound in the bundle of life.

And now a few words about my late brothers and sisters.

My brother, Yaakov, lived in Lublin, near Włocławek. His trade was hat–making and he owned a store where he sold head coverings and brimmed hats. His wife, Leah, was a housewife, and they had two children, a daughter, Rozsha, and a son, Yehuda, the infant. He was respected in the city, a member of the community's administrative committee, devoutly religious, and his opinions were respected. When the Nazis entered Lublin, they began harassing the Jews just as they did everywhere else, and then the shipments to the death camps began. He escaped with his family to Węgrów, where my sister lived, and from there they went to the Warsaw Ghetto. They suffered all the hunger and pain afflicted the Ghetto. We do not know if he had been sent to Treblinka or died in the Warsaw Ghetto during the uprising. May God revenge his soul.

My brother Shalom lived in Lodz, at 5 Dravanbaska Street, with his wife, Michela, and their four sons. He owned a grocery store and was sent by the Nazis to Poznan, where he suffered from hunger, violence, and forced labor in stone quarries and road–masonry work. He died there, in the camp in Poznan. His wife was sent in a shipment to the death camp, his children were

[Page 136]

sent to a children's institution in Lodz for several months. After its destruction by the Nazis, the institution's children were sent to the death camp. May God revenge their souls.

My sister, Chaya Devora Mandlboim, lived in Węgrów, with her husband, Yisrael, and their only son, Reuven, where they owned a sewing shop. When the ghetto was razed by the Nazis, they were sent to Międzyrzec and from there to the Treblinka death camp. May God revenge their souls.

My sister, Royza Leah (Rozsha), died before the war on the 7th of Adar, 5697 (February 18, 1937). May her memory be blessed, and her soul bound in the bundle of life.

|

|

| Royza Leah (Rozsha) Yamnik |

by Yitzhak Levin

Translated by Marshall Grant

© by Roberta Paula Books

Fate dropped us into the city of Bielawa. This was a city in the Republic of Bashkortostan, and served as its capital. In June 1942, we were expelled from Chelyabinsk, where we were classified as “unwanted” because of our Polish descent. We were declared as “dangerous to the regime” and forced to leave the city within eight days due to the transfer of ministries from Moscow to Chelyabinsk. Despite the fact that the city had two high schools and was close to the Aksakavah train station, its streets were not paved and there were no sidewalks, no sewage system, no electricity and water was pumped from a spring inside the city.

Most of the homes had one story, and the city in general looked very neglected. To rent an apartment was almost impossible. It cost quite a lot to find small living quarters with a family, and this was beyond our means. We had no choice but to enter a kolkhoz (collective farm) bearing the name Nadezhda Krupskaya, named after Lenin's wife. The kolkhoz was eight kilometers from the city, and that is where we worked for housing and a bit of food.

In August 1942, I was conscripted into the Red Army, which enabled my wife to find work in the city's only factory. She rented a small place with a family whose husband had been sent to serve on the front. The entire home was one room without any services or furniture. My wife had to sleep on the floor on a straw mattress. Rain dripped through the roof, and the entire structure would sway in stormy weather.

My wife was pregnant then. On February 17, 1943 our daughter was born and I received notice from my wife through a letter she had written me. They called her Izza. On her birth certificate, which had two languages, Russian and Bashkir (a Turkic language), it was written that Izza Izakobanna was born on February 17, 1943, the daughter of Yitzhak Shulimovitch Levin and Dvora Izralubanna from the Taub family.

After her maternity leave came to an end, my wife returned to her usual job, working 12 hours a day. During the work day, the baby was in a baby house, Yasla in Russian, and there they were obligated to feed our daughter, provide medical and general care, and a mattress and blanket for the baby. My wife was forced to buy these things from her own money. The institution held her ration card. Twice a day, my wife went to the Yasla to breastfeed the baby, but a woman who labors physically 12 hours a day and who does not always eat properly is unable to nurse, so she had no choice but to buy milk and other necessities in the free market as a supplement to baby food, all from her very limited wages.

So why was the baby losing weight?

The institution received enough food, but the baby's appearance deteriorated from day to day. She was so weak she often caught cold. Her system lost its power to resist. And the caretakers, they prospered, and so did their families – much of the baby food also made its way to the open market. The authorities never discovered a thing. Was the reason that the baby food had been stolen in such a successful manner that the method was never revealed? Or were they not interested in uncovering such a cruel, criminal act. The fact is, the baby house received the food and the babies went hungry.

[Page 138]

In August 1943 our daughter passed away, and I never met her. She died in the hospital.

In the last week before her death, my wife sat next to her bed day and night. There were no means to save her life, not even medicine was given to her – it was sent to the wounded soldiers. Then, my wife, while sitting next to the baby's bed, fell asleep from exhaustion and when she awoke, Izzika, was no longer alive. My wife bought a coffin for her, and brought her to the cemetery by herself. She was so exhausted she was unable to dig a grave for her daughter, and she had no money to pay for someone else to do it. The cemetery is located in a hilly and rocky area. She found an unused area, put her daughter in the coffin and covered the grave with broken rocks and clay. The rocks and clay were so sparse, there wasn't enough to properly mark the location as a burial site.

Those reading about this true event should think for a moment and enter the heart of the mother and the hearts of many other mothers who experienced a similar fate…

[Page 138]

by Yitzkhak Levin Israel

Translated by Roberta Paula Books

© by Roberta Paula Books

The last time I saw her was August 1939, one month before the beginning of the end. I don't know when she was murdered. I only know she is gone.

When she was six, her parents registered her in the private Hebrew school in the town where she was born, Kolo.

The same year that she began learning, it could even have been on the first day, the calamity flared up that destroyed people, especially Jews.

Perhaps you, Lushia, can answer the question of why they did this.

Permit me dear child, my beloved only sister's daughter, to use the name your parents called you by at home, which I know you can't use. I don't even know where your grave is, or your little body. No, I cannot think about it. However, you do not leave my thoughts. Your mother was called Frayde Libe. Her maiden name was Levin. Your father was Yekhiel Meir Hayman. They worked hard their entire lives. I am convinced that in their lives, which were cut off so early, they never wronged anyone. They were members of the General Zionists. They got a blue and white little dress ready for you to wear to school. With your light blond braids with blue ribbons, you loved to jump rope, like most other children. When your little feet jumped, your white braids decorated with roses also jumped. Today is the first day of Passover 1973. Do you know, Lushia,

[Page 139]

how long it has been since I have seen you like this? Already thirty four years. You would be turning forty. You, my child, have been gone thirty four years …

Thousands of people, smart, educated, with eminent names and fancy titles, and scholars, have written hundreds, thousands, maybe millions of books about the war. They have searched and are still searching for reasons to explain the mass murder. There have already been thousands of trials against these murderers. Thousands of these murderers have been punished with arrest and sentences ranging from one year to life,

|

|

| After much effort I received a photograph of my extended family. In the photo from right to left are my uncle (my father's brother) Moishe Levin, his daughter Leah, his son Sender who in 1939 left for the occupied territories of Soviet Russia. |

but after a short time, they were quietly released. I continue to ask how the entire world remained silent and allowed you, dear child, to be murdered. Was the whole force of the world in agreement with this terrifying murder? Was the whole world weaker than one country, Germany, which had about 60 million citizens? Answer me, leaders of all countries. I have the full right to pose this question.

[Page 140]

In 1943, he was seriously injured while serving in the Red Army. Today he lives in Russia. A sick man, an invalid. Standing beside Sender is my aunt Yetta. Seated on the table are Khanele and Abbale. The pious Jew sitting on the left is Aunt Yetta's father. He died before the war broke out. He was lucky. However, the Nazis desecrated his grave.

My father was a pious Jew. He sold kitchen utensils. He would travel to fairs with his wife. They slept together in the same bed only one night a week, the Friday of the Sabbath, as well as on the nights of holidays. He was not a wealthy man.

When the murderers entered Kolo, they divided the Jews into three groups. One group was sent to Izbica in Lublin province. Among those sent were my sister and her family, my uncle Moishe Levin and his family, and that is all.

Little girl, Lushia, how much suffering did you endure?

Lushia, what was your fate?

Lushia, where is your grave?

by Y.L.L Shlomi

Translated by Roberta Paula Books

© by Roberta Paula Books

I'm telling you. What luck, you hear. What luck that, in the diaspora, there were two days of compulsory rest. Of course, first of all was Shabbes, the Sabbath. And Sunday was Sunday. On Shabbes, our mothers actually rested. Friday? No. Fridays, the work was doubled. A half a day for a whole day's work, if not more. However, Sundays, beginning on Motzi Shabbes (Saturday night, after the Sabbath has ended), they did the household work for the entire week. Washing, drying, ironing, mending, darning and embroidering in a great variety of color work. Naturally, our mothers had to work with our fathers for their means of support. They had to go to the market. They also went to the hamlets with their husbands to acquire various goods from the farmers and then return and sell the goods to the large merchants. They would leave late Sunday night, or early Monday morning when it was still dark. They carried two baskets in each hand and a pack on their backs. They bought chickens, geese, ducks, eggs, butter and leather hides, as well as other hamlet products. Some hamlet merchants owned a horse and wagon. Sometimes they would buy a calf. Among those on foot was the

[Page 141]

Bialaglovsky family. But when you asked about the Bialaglovskys, nobody knew who you were talking about. However, everyone knew them as lame Khaye and blind Yosef. I would like to tell you about them.

In our town, everyone had a nickname, including them. During the last years before the war, they lived with Aron Tarantsik in a place in one room on Warsaw Street (a nice name). They changed apartments often because they didn't have money to pay the rent.

Except for adversity, they possessed nothing. Grown children don't count. They had three surviving children. Their oldest son, Gutman, was an apprentice tailor. He caught a cold walking in the rain to Izbica one night to find work. His illness grew worse, and he developed tuberculosis. He died when he was nineteen years old. Their daughter, Yokheved, was now the eldest at home. She left to work for a family as a maid. The youngest son, Lipman, sold newspapers. There was another small boy at home.

From all good fortune, except suffering, they had nothing.

From Monday to Thursday, this husband and wife would walk through the hamlets every day in order to earn what was barely a living wage.

Fridays, Khaye would prepare for the Sabbath, and Yosef would go out on the road.

Ay, ay! He would often sigh. At least on Friday he could rest his ears a bit. She has such a gift of gab that she talks twenty-four hours straight. Yes, my Khaye, we should live so long, loves to talk. And even if I don't know what she is talking about, I have to listen until my head explodes. Yosef was blind in one eye. The eye was obscured with some blue, some white, intertwined with red veins. It did not look very appealing. I don't remember which eye it was, left or right. I could have been the right. Yes, the right eye.

A tall Jew, with broad shoulders, thin, with a heavy, lurching gait, he walked through the streets and lanes in worn out shoes. In summer through the dust, and on rainy days through the mud. Beside him dragged Khaye the lame one. She had a peculiar gait. On one foot, she was of normal height, on the other, like a twelve-year old child. She did not sway from side to side nor did she lead with one foot. She was just little, and then big.

When did this happen to his eye? It was not from a beating. He may have been born that way. We also don't know when Khaye

[Page 142]

began to limp. I believe they were both like this at their wedding. However, before that, she could talk, rapidly and at great length, without stopping. If they gave a talking competition in Pshaytch (in Polish, Przedecz), she would surely win first prize. She was never lacking in something to say. She was the newspaper for the whole town. She was never short of topics or, by no means, words. She knew everyone and everything from every which way.

They never complained about their fate; whatever G-d gives is positive. The youngest son began to walk with his parents. Everyone worked daily from quite early in the morning until very late at night. He, a blind man, and she, lame. The daughter, away working as a maid. Lipman was no longer selling newspapers; he was now working for a hat maker. They each had grey, dusty faces, exhausted, never fulfilled. They accepted their fate with a sort of religious resignation, with devotion to the one that chose them.

Despite the fact that they had little time to sit on school or kheder benches, it must be said, with no opportunity or possibility to study, they were able to read Yiddish and Polish, and they loved to read.

Their difficult life, their pure, difficult life, was cut off in the gas chambers. Do not forget about them.

by Yitzkhak Levin

Translated by Roberta Paula Books

© by Roberta Paula Books

Oisada, according to nomenclature, is a place too small to be a city and too big to be a village. The town of Drobin, in the Plotzk region, was such a place. Not grown and at the same time overgrown. We lived there from the beginning of 1937. The centre was the marketplace. That is where the church and town hall were. All around the four cornered plaza were homes with businesses, plastered with stones. Sherptser Street, where the rabbi lived, was paved, as well as Plotzker and Ratzoynzer Streets. The other three or four streets were sandy in the summer and very muddy in the fall. Beside the church, there was a square they called a park, with benches where couple could sit unnoticed. The synagogue was on

[Page 143]

|

|

| Mrs. Royza Taub Padro, of blessed memory, and her daughter Dvora, the wife of Yitzkhak Levin, who lives in Israel |

Zalisher Street. The bottom part was built of brick, the top part was wood. There were two libraries, one on the Jewish Street and one behind the headquarters of the fire fighters. There were few readers. There were no theater performances, movies, or public readings, at least in the years I lived there. Buses passed through two – three times a day.

We lived there from the beginning of 1937. The few weeks before the war broke out, we were nervous and life was intense. There were open meetings and gatherings every day, often two or three times a day. This depended on the mood of an important man or woman. The same sentences were repeated “Strongly connected is ready”. Not a button from a soldier's uniform. France is with us. The first

[Page 144]

time they gathered, people shouted and sang with them. The last days before the war broke out, people just shook their heads. On August 31st , the police and municipal leaders disappeared. The citizens organized self defense only at night. On the 1st and 2nd of September, the town was bombed a few times. Civilians were killed, children. Individuals and groups of Polish soldiers appeared to be without leadership and without weapons, nothing except for small guns, and those who were last to be mobilized didn't even have that. Another group of soldiers stopped in the forest before our town on the way to Plotzk. They were bombed, and they were all killed. Among them were eight Jewish soldiers who were in the Polish army, mobilized shortly before the war and returning one at a time. However the pious, learned Jew Yeruzlimsky did not return. He fell. The soldiers told about the bitter battles near Kutno, Gostynin and other places. They all repeated the same word, “treason”. They sold us out.

Many took their families to neighboring villages. Others hid in cellars. It became very quiet. The Nazi army was coming through on its way to Warsaw. Soldiers grabbed people for work, mainly Jews. They arrested the rabbi and the priest. The teachers from the school were forced to clean the streets. Those arrested were freed, but then forced to clean the streets as well. They didn't permit us to gather in the House of Prayer. Jews gathered to pray in private homes.

They transformed the synagogue into a hospital for wounded Polish soldiers. They placed horses in the church. Warsaw fell. Among the lightly wounded was someone from Ukraine. He knew the language of the occupiers. Every day, he reported the conversations of the Polish soldiers to the Germans. The commandant of the hospital … I heard one of these reports when I was brought to work at the hospital. They took the sick ones away somewhere. They took over the hospital with the help of Jewish forced laborers. The building materials of the appropriated synagogue were distributed among the Christian population.

Together with the help of the Polish population, especially the wife of the local chimney sweep, they robbed Jewish business and private homes. The first victims were the clothing store owned by the Naymark family and the food wholesaler Finklshteyn. Things worsened for the Jews day by day. It is hard to be seen on the street. Big and small non–Jews pointed fingers and yelled “Jew”. The Germans beat and swore with the most horrible dirty words. We must remove our hats for every German soldier.

[Page 145]

They tore off someone's ear. Another's beard was torn off with his skin. Every new day was worse than the previous day. New edicts every day. On the eve of Yom Kippur 1939, we saw three people walking in green civilian suits with Tyrolian hats on their heads. With piercing eyes, they examined everything. The next morning, Yom Kippur, the rabbi and his assistant went from house to house telling everyone to come to the marketplace. When everyone was gathered, these three men stood by a table covered with white paper. On the paper were a razor and scissors. After a speech and some yelling, we all learned that we were not human, we were a type of animal, parasites etc…

Then they called on a Jewish barber to cut off our beards, but only one side, as you would cut a four cornered paper from one corner to the other. The faces of the shaved Jews looked distorted. Some Christian women looked out their windows and cried, but most of them laughed. When the cutting was over, they made us do drills, run, fall, roll on the stones and jump like frogs. Among us there were older people like the old ritual slaughterer, the old Warshavsky, a Jew of around 80, the tubercular sick tailor Fedru). This lasted for four hours. Two days later, they gathered all the men between the ages of 15 and 45, Jews and Christians, and locked us up in the church. We remained locked up there for two full days. Once a day, they permitted relatives to bring us food and allowed us to go out and relieve ourselves. But once a day is not enough. The first ones to dirty the place were not Jews. On the second night of our confinement, they ordered that all residents were to remain in their homes the following morning. The windows must be totally covered and anyone who looks out will be shot. The next morning, they actually took everyone in covered trucks to a field near the town of Sherptz (Sierpc in Polish), approximately 26 kilometers from Drobin. There, they made us sit with our hands on our necks. All around us were shiny machine guns manned by soldiers of the Wehrmacht. After sitting for two hours, they took us to a factory building called “Sherptzianka”. The first three days, we received only water to drink. On the fourth day, Jews from Sherptz (Sierpc in Polish) brought us baskets of bread. In order to get permission

[Page 146]

to bring us food, they told us they had to pay two silver coins, each worth 10 zlotys. It is hard to forget the good deeds that people did, but it is even harder to forget those who wanted to transform us into animals.

Many among us, Christians and Jews, became very nervous due to hunger, their eyes bulged and their faces filled with blood. Many wailed like children. When a middle aged soldier took away the baskets of bread from the Jewish women, he brought them to the large factory, where we were 2,000 men squeezed together. Slowly, with a pocket knife, he cut the bread and threw it to us. Forgive me readers, but I cannot find an appropriate way to express what took place. Many of us fell upon the bread, tumbling over each other. A pile of people rolled on the floor, tearing at one another and biting. This was, after all, the third day of hunger. The Jewish women brought a lot of bread, but the German with his helper beside the machine gun loved to watch us fall upon and fight each other.

Among others who did not want to provide any pleasure to the Germans were me and my two brothers. Due to fear from all the noise, we hid behind a wall. Everyone received bread. When he saw not everyone was prepared to fight, he gave everyone a piece in their hand.

Later on, they gave us food cooked in the military kitchen made with produce brought by Jewish women. Many of us were beaten. When you grab your food and don't eat in a normal way, many became ill and could not sit in a position that the cultured guards demanded. Therefore they were beaten.

Now tell me, who is the animal?

Once every two days, they took us like sheep to a field to empty ourselves of natural needs. We were surrounded by armed soldiers. Besides guns, they had cameras and filmed the entire procedure.

After two weeks, a German in an Air Force uniform came to give a speech. He spoke in a mixture of Polish and German and told us they wanted to take us to work in Germany, but since our friends the English and French were bombing the trains

[Page 147]

they regretted to have to send us home. The next morning, a pastor came who spoke Polish. He handed each of us a document with our name on it. A few men remained, and I do not know their fate. They were Polish soldiers who had been captured by the Germans. Among them was a Jewish boy from Lubin in the Voltslavek (Wloclawek in Polish) region, and the guard from the township of Drubin, because the Germans had found a broken gun behind the roof of his house.

It was raining. We three brothers with documents in our pockets headed home on foot. No one said a word during the twenty-six-kilometer walk. We were deep in thought, each in his own thoughts, but similar as if we talked about them out loud. What's doing with our sister in Kolo? How are they living there under these circumstances? Our mother and youngest sister? Our experiences in the temporary camp told us a lot. The “Brown Book”, published a few years previously, was familiar to us. We already knew about Dachau and other educational institutions in fascist Germany. Many Jews who had been chased into Poland told us, but we could not foresee everything. The most important was the collaboration with Russia, and how the western countries wanted to rid Europe of communism.

We arrived home with a confirmed plan. Our older brother Gavriel left for Warsaw. He believed that in a big city it would be easier to get lost in the crowd. A few days later, my other brother left for Warsaw with a Soviet destination. I remained with my mother and sister Esther. I received work replacing glass in the church. All the panes had been broken during the bombing. I worked for a month, and when I finished the church was active again. They prayed to God and quietly sang. When the priest paid me the 220 zlotys he owed me, he told me I should take the opportunity and go to Russia because here there will be no life for Jews. That is what I did.

I went with my wife, mother and sister. Also travelling with us were Rivka Rizuv, Pikhas Zayde and Leybush Petrikoz. All three were born in Drobin. We arrived in Bialystok without much difficulty. It was noisy with a lot of red flags. Business went from hand to hand. There were no pogroms and no one grabbed you for forced labor. But there was much hatred among the local Christians and Jews toward us. Not everyone, but many. There was a shortage

[Page 148]

of work, a shortage of food. There was no money. The black market ate up everything. We found our brother Moishe. He was recruited to work and left with our mother not knowing where. We were not familiar with the geography of Russia. It was enough that they told us we would receive a place to live, work and food. At that time many were being recruited and returning from various places in Russia. They told of a difficult life and even more difficult climate. Ignoring this, in mid December we were recruited for work. On January 17, 1940 we arrived in the city of Tzielavinsk, on the border between Europe and Asia. We worked in construction. It was freezing cold and we worked outside without appropriate clothing. But the worst was the shortage of food. We stood in line half the night for bread.

During February and March, many Poles passed through Tzielavinsk. They had escaped from Magnitugursk where they worked at digging stones. Like birds, they were attracted to warmer places and easier conditions. A young man from Drobin with the family name Prost told me that my brother Moishe and my mother were living in Magnitugursk. I wrote to them and they came to me without a permit. However, my brother did not want to remain in Russia. “I never imagined how life would be in a socialist order”, he said. On May 9th 1940 they left. I did not go because I did not have the money for a train ticket. I will not recount here my later experiences, perhaps later. After a while I established correspondence with my brother in Warsaw, with my sister Frayde Libe and her husband Yekhiel Meir Hayman and their daughter Lusha (Hinda) and my sister Sheyne Feyge who I lived with. I knew they were sent form Kolo to Izbitsa past Viepshem. I received letters from them until the war broke out in 1941.

In 1944, when we entered liberated Lublin, I saw Majdanek. Someone who had been recently mobilized told me no Jews from Izbitza had survived. I could not believe it, even though I was sure he was telling the truth.

By the end of January 1945, my military unit was in Warsaw. We were delegated to clean the Belvedere area of mines. I went to Praga, 4 Targuva Street where my brother Gavriel had lived before the ghetto. A female guard met me at the gate. She saw that I was a Jew. Who are you looking for? She asked. The Tsaytunger family, my aunt and my brother Levin I responded with a happy smile. They all left long ago to Treblinka.

[Page 149]

What kind of place is that? I asked. That is a death camp, she responded. That is where they finished off so many.

Two years later, when my wounds healed, I was released from the military hospital, but this is not important. A month later, my wife returned from the Soviet Union. I learned that a large portion of Jews from Drobin, including the mother of my wife Royza Taub –Fedru and her seven year old son Moisheleh were sent to Piatrekov Tribunalsky ghetto, where they died from a Typhus epidemic.

We remained in Bidgashtsh. I looked in many places for Jews. I was in Drobin. We decided that after the war we would write to a Christian in town who would provide us with addresses of those who survived. He told me that just before the war broke out in 1941, he received a letter from my youngest sister in Bialystok. She told him that she and my brother Moishe were living and working there together with our mother, and things are going very well. He burned the letter and did not respond. A few years later I went a few times but did not receive any news.

I searched with the help of newspapers, radio, visited many places, asked hundreds of people. I looked at the faces of people passing in the street, stopping strangers and pored over lists of survivors.

I'm still searching…

by Moshe Belevsky

Translated by Marshall Grant

© by Roberta Paula Books

My father, Mendel Wolf Belevsky, the owner of a bakery, was born in the city of Przedecz on January 18, 1882, to his father, Avraham Simcha, and his mother, Frieda Rachel (Brostovesky). My late father was active in the local community, a member of the bank's management committee, and for years he was the gabbai (synagogue caretaker) and member of the Chevrei Kadisha (ritual undertakers). He also served 15 years, until we left Przedecz in the spring of 1939, as the gabbai of the yeshiva, together with his friend Itsha Weidon. The worked closely together in managing the Bikur Holim Group and he was a Mizrahi activist and an enthusiastic supporter of Tzi'rei Mizrachi v'HaShomer HaDati (the Young Mizrahi and Religious Guard) branch in our city. The children, especially the boys, received a religious education that emphasized the love for the people and land of Israel. This is how he worked, significantly contributing to the yeshiva led by Rabbi Zemelman, who was one of my teachers. My father was a supporter of the Rabbi from Skierniewice and travelled to visit him at least once a year.

[Page 150]

Dealing with public issues was considered by my father to be very important, and this heavily influenced my mother, Frieda Rachel.

In addition to the bakery managed by my grandfather, my grandmother had an additional profession as a midwife, as it was defined in those times. Everything she earned from midwifery for wealthy families she gave to the infant's mothers who had little. Even if she was not paid, she gave from her own pocket. When not working as a midwife, she took the time to prepare jams, sweets and beverages, and would take them to the newborns' mothers who could not afford it.

My grandfather once turned to her and said: Rachael, what are you doing? If you continue with your generosity, we will, God forbid, after the age of 120, leave this world without even having enough for burial shrouds and we will have to enter the true world in garments that we don't even own. The next day, my grandmother went out with the bakery's daily earnings, and bought white cloth. She worked days and night and sewed a burial shroud for herself and my grandfather. When she finished, she turned to my grandfather and said: My dear husband, we now have shrouds for ourselves, and now, can I continue with my “big–heartedness”, as you call it? You must know, you are my partner in heaven. My grandfather remained silent, which fully expressed his consent to their partnership. They lived long and meaningful lives.

|

|

Standing: Brayna, the daughter of blessed memory; Moshe, the son, and his wife, Liba, who live in Israel Parents are sitting: the late Mendel Wolf and his wife, Hanna Sarah; between them, their son Chaim, who lives in Israel Sitting below: the late Baltzia and Label |

[Page 151]

My father had two brothers, the elder was Lipman Belevsky, and the younger Pinchas Aharon Belevsky, both of whom moved to live in Sompolno with their families in 1928. They were active in the community until its annihilation by the Nazis.

The three brothers, together with a large part of their families, died in the Holocaust. I moved to Israel in 1933, my brother Yosef Chaim, who survived the Holocaust in work camps, arrived later. The members of my family, my father, Mendel Wolf; my mother, Hannah Sarah; my sisters Brayna and Baltzia, who were active in Beitar; and my brother Label, may god revenge them, all perished.

From my Uncle Lipman Belevsky and his large family, from his married sons and daughters, only two grandchildren survived the Holocaust. They both live in the United States.

My uncle, Pinchas Aharon, his wife (my aunt) Zipora, and their married daughter Frieda Rachel, the namesake of my grandmother, with her husband, and two sons, Moshe and Dov, all were murdered in the Holocaust. Their son Avraham Simcha survived the camps during the war and has lived in Israel since 1949.

My mother of beloved memory, Hannah Sarah, from the Komiskovsky family in Sompolno, was the only sister to six brothers. She worked hard to provide us, the children, a religious education. She had a noble soul and was known for her deeply religious beliefs and hospitality. She paid especially close attention to settlement efforts in Israel. Every Friday, prior to lighting the candles, she put her donation in the collection box of Rabbi Meir, who was known to have had experienced a religious revelation, and then she put her coins in the blue JNF box.

All six of her brothers were known as gifted Torah scholars in the 1930s: Noah the eldest, Mendel, Meir from Sompolno; Yehuda Leib, Avraham from in Slupca; Bezalel who lived in Babiak. Most of the children were married. There is no way I can describe in words the personality of each one of them, but I can say: Torah, education and Derech Eretz (treating people equally) were equal in value. They were established financially, they gave their children the best education, all were enthusiastic Hasidim who followed Rabbi Skierniewice and often travelled to spend time with him.

In the 1930s, there were attempts to organize and buy a shared property in Israel for the entire family, with the goal of eventually moving to Israel. Some of them already had children in Israel. Immigration to Israel began in 1923 and continued until the riots of 1936. These bloody clashes shattered dream of my large family. Then the war broke out and the Nazi henchmen destroyed everything in their path. My six uncles and aunts, and most of their sons, daughters and grandchildren, perished in the Holocaust.

May these lines bear witness to their blessed memory. May God revenge their lives.

A small part of the extended family survived the Holocaust in the camps and reached Israel shortly after it was established.

by Moshe Mokotov

Translated by Marshall Grant

© by Roberta Paula Books

Despite the fact that the author of these lines is a son and a brother of a family that has been sentenced half to death, and half to life, I will objectively discuss the members of my family who were murdered.

Those who knew my father, Yitzhak Mokotov, would identify and agree with me that he was a dear person, from every aspect. He was one of the city's providers. The city's less fortunate were always welcomed, and they always found someone to whom they could voice their problems. As a child, I never understood why they visited so frequently. My father fulfilled the mitzvah of welcoming a bride with loyalty and happiness, and no less than a dozen couples were married in our city, with my father taking care of all the wedding arrangements. Here is where I need to add that my mother

|

|

| Yitzhak Mokotov and his daughter, Bronka |

enthusiastically supported him and his selfless efforts. She was the one who prepared the list of what was needed for the wedding. I still remember something my father would say to my mother, “What happened, Ruzsha, you have no list for me?”. That was what he would ask her.

The readers of this book will surely remember the horses we owned and a servant named Banashek, who would take care of them.

[Page 153]

This man, Banashek, would fill the storerooms in our yard with coal and peat. Wood was gathered by the guard living on the property, a tall and simple non–Jew named Piatcak. I was told this man “inherited” our apartment and began living there after Przedecz became “Judenrein”… When winter approached, my mother would prepare a list of the needy, which grew from year to year, and give it to my father. Together with Banashek, my father would make sure that the homes of needy Jews would have wood for heating. It took about a week to complete this act of generosity. Banashek then would fill the storeroom with an assortment of essential items needed for the harsh Polish winter. For months I waited with excitement for the coal to arrive. As a child, these were “holidays” for me, even though I would come home dirty, and more than once I was lectured and reprimanded by the heavy hand of my father.

My father's business relations and attitude towards the Christians gave him a reputation in the city and its surroundings, and more than once, these relationships contributed to various issues related to the city's Jewish citizens. He was always welcome in Magistrat. I remember once that my father did not hesitate to call the city's mayor (Bormisht) Novkovsky to come over at night when the city's stamp was required for a certain document. My mother was not only a housewife, she had her own “private matters”. She was one of the founders of the city's library and managed it for many years. Another board member – Mr. Yaakov Topolesky, is certainly remembered by this book's readers when he participated in a memorial evening for the holy souls of our city, in the hall for Polish emigres in Tel Aviv. There isn't anyone in our city who doesn't remember the dear Itche Wayden, or the blond Itche as he was also known. He was not well known because he was a tailor for women. I believe his reputation was based on his service as the gabbai of Bikur Holim in our city. My mother worked together with this Itche, and she donated much of her time to this institution that was nothing but primitive, but it was critical to our needy city. Mr. Itche often visited our home for business not related to tailoring. When Purim approached, as was his habit, he arrived to present his original plan to my mother for donations. Two young men would wear identical costumes and visit Jewish homes, with bells in their hands, and request donations for charity. The people made these donations without saying a word, and were then issued receipts. I don't think any of the city's survivors have ever forgotten this scene. The sound of the bells from a distance told us children that the goodhearted young men in costumes had arrived, and it made us get up and leave the Shulchan ha'aruch prepared for the Purim meal. It was the height of the evening for all the city's children.

The Purim meal always makes me sentimental. It was on this evening, right before the meal, that my sister, Baronka, was born. Everyone knew this sweet girl with pigtails. When we came to Israel in 1935, she became just like all the other girls her age, a “sabra”. She was cute and well–behaved, quiet and serious for her age, and carefully chose her friends. On Rehov Shlomo Hamelch in Tel Aviv, there is a national religious school and it still exists today, but unfortunately only the school still remains and each time I pass it, I look with grief and sadness at this building, which provided me with some of the best times of my life. The school's principal at that time was Mr. Yehiel Shtrauch from Włocławek. He was also the principal when I studied at the Hebrew gymnasium there. Many people knew this wonderful girl Baronka,

[Page 154]

and I was told she grew into a tall young girl, who was exceptionally beautiful. This was after my family returned to Przedecz to liquidate the last of their possessions. I was also told that Rabbi Zemelman, who gave Tanach classes in Przedecz's only school, would often use her as an example before his students.

I have a family member who emigrated to Melbourne, Australia. She told me that when Baronka was with the rest of her family in the Warsaw Ghetto, she had a chance to save her life. A Christian, who knew my younger sister, asked and even begged her to leave the ghetto and come over to the Aryan side. Her response was: I will leave my father? And she perished with her mother… Yes, I have reasons to be sorry; and how!

Most of our belongings were distributed among non–Jews whom my father had worked with. In order to finally liquidate his business, my family returned to Poland. I remained here supporting my father's efforts to keep his English [visa] valid. It took my father more time than he planned to liquidate his business. In order that the visa would remain valid, and at the recommendation of the Consulate General, my mother arrived there by herself. This was two weeks

|

|

| Bluma Zukerman (Mokotov), her husband Hanik, and their daughter Galila |

before the war broke out. Shaul Makovitsky also travelled with her. Both arrived at the Tel Aviv port due to the riots of 1936–1939 (which is the reason the Tel Aviv port was opened). Friday, September 1st, 1939, was a black day for the Jewish people: Poland's Jews, three and a half million strong, its beautiful sons and its magnificent Judaism were destroyed in this war. In the beginning it was terrifying, and the level of concern rose every day. We did as best we could to prevent our family from becoming separated, but it seemed the distance worsened daily. The Italian consulate was in Yaffa, and every Shabbat I would travel there to give the Consulate General letters and documents that would be sent to my father

[Page 155]

|

|

| Red Cross form that was received in Israel from my father Itzhak Mokotov |

[Page 156]

|

[Page 157]

to help him leave Poland. This all was sent through the consulate's “diplomatic post”, and from my father's response that I received (via Romania), we understood the documents had reached him. Again, there was a glimmer of hope that motivated us to double and triple our rescue efforts. And then, the last of our hopes were dashed. Italy declared war on England. The last bridge, over which the two families separated by the war were to be reunited, had collapsed!!

And then, everything that happened, happened to everyone….

There is a woman living in Jerusalem named Chava Appel–Rozneka. She met Meila Orbach–Brand, also from Jerusalem, as a young girl. Both women told us that my father, together with Meila's brother, Haim Aharon, leased an airplane when the war broke out in an attempt to leave Poland. Who knows if this is accurate or not, and in fact, what importance does it hold now?

I cannot complete the testimony of my family without mentioning my eldest sister – Blumka. She was four years older than I. When she completed the local school, she left Przedecz for Warsaw, where she studied in a girls' school named after Pearla Lovinska. My parents decided to nurture her musical talents. Even while in grade school, she was given violin lessons by a musical artist who, if I am not mistaken, lived near the “old market.”

|

|

| Bluma Mokotov and her daughter, Galila Tel Aviv, 1936 |

[Page 158]

We called him Langa, and I can see my sister and the violin in her hands, but I am not sure which is larger – she or the violin. It appears that her talent was significant, and she continued to take music lessons with the church's official pipe organist (Organista). Over time, my father managed to bring a piano home, which, of course, caused a stir in Przedecz. And from then on, music could be heard in our home. Four hands were also heard when the Organista would visit and play music with my sister. I would like to note one small event that typically characterized my sister Blumka. One night, we were disturbed in the middle of the night by quiet notes from the piano. We were scared, and then surprised when we saw Blumka in the living room, sitting at the piano with a candle next to her. She was playing a selection pianissimo over and over so she would remember it by heart. My sister returned from Warsaw and travelled to Wloclawek for a short time to study accounting. This education contributed to her efforts to assist my father manage the books of the business operated by him and my Uncle, Neta Wasserzog. She was one of the many enthusiastic supporters of Zeev Jabotinsky. It is interesting that such a small city, such as Przedecz, could be so vibrant with politics and political parties. I think the large number of its political parties encouraged her to find ways to immigrate to Palestine. I was told that more than once she was seen in a crowd, with a sign in her hand near “the Club” or library when a guest speaker would appear. The evenings were usually exciting … there was no lack of people with opposing opinions, and heated engagements were a sure thing. Her intention of immigrating to Palestine introduced her to a young man from Warsaw, Nehamia Zukerman. They eventually married and immediately went to Palestine. Their daughter, Galila, was born after their arrival.

In addition to my father and sister of blessed memory, I would like to add several more members of my close family who are an inseparable part of this story. My grandfather, Binyamin, and his wife, Golda. I was just a child, no more than five or six years old, I remember very large straw baskets in their home. These baskets were to be used to pack their possessions, and they were planning to immigrate to Palestine. They were among the first Mizrahi activists at that time. We were all devastated when he became ill and passed away in a Kolo hospital at the age of 56. The fate of my family could have been different if my grandfather had not left us at such a young age. My grandmother moved into our home and for the rest of her life my father treated her fairly and with respect. For all intents and purposes, she managed the household.

The beginning of the end started at the church and ended in Chelmno… My aunt, Chava Rauch, my mother's sister, and her two children, Moniak and Marissa, together with her husband Mordchai. Their end was the same for everyone. My uncle, Yaakov Wolf Rozen, and his wife, Rayzel, and their three daughters, left Przedecz for Lodz. There, it appears, they met their horrible fate. My uncle, Avraham Rozen, died an “honorable” death. He was fortunate in that he was taken by the Angel of Death. He was buried in Kłodawa in an unmarked grave.

May this testimony, which I dedicate to my beloved family, respectable people who always tried to help others, serve as a memorial for their memory.

May the memories of all the victims from our small city, and those of all Jews who were murdered, be blessed.

With great love, the son–brother,

Moniak

by Leah Zemelman Pnini, Jerusalem

Translated by Marshall Grant

© by Roberta Paula Books

Through the wall of forgetfulness that is closing in on me, and through a veil of serenity I did not want – in the dead of night I hear my brother's cry – a terrible cry, “You have sentenced us to destruction!” So, with great respect, I sit to provide testimony. Listen and read, my Jewish friends in Israel and the Diaspora, and those children of families, of thousands of families, naïve and honest, who were murdered, and their blood cries to us, “Live on our holy country as a free nation, a nation that never knew the Diaspora, and the nation of murderers will be forever vanquished.”

My family was normal and simple: four brothers, four sisters, an honest mother and my father, the rabbi.

My father was born in Drobin, where his father, my grandfather, served as rabbi.

He was appointed as the rabbi of Przedecz at a very young age. The city's younger members went riding on horseback to receive the rabbi at the city's entrance. He was slim, accompanied by a woman who was almost a little girl herself, and in her arms, my sister, Esther, who was eight months old. This is how the people of Przedecz, with singing and dancing, welcomed their rabbi as they paraded through the city's streets leading to the synagogue. It was there he spoke to both the Jews and Poles, as one, and his soul felt connected to Przedecz.

My father received many offers to serve as a rabbi in a larger city, such as Siedlce and Nasielsk. Nasielsk was my mother's birthplace, but my father, as I mentioned before, felt connected to Przedecz, and cutting those ties was impossible. I heard much from my father about how his emotion needs were never fully fulfilled, but despite these feelings, it was not enough to make him leave the city he felt so affiliated to. He would serve as the city's rabbi until the Nazi soldiers began destroying and killing the Jews, when he escaped to the Warsaw Ghetto. The community in Przedecz had about 250 households, most of them craftsmen such as tailors, cobblers, hat makers and leather workers. There were also small businessmen and even a few who were larger.

From the aspect of development, our city certainly lagged. It was only in 1928 that electricity finally arrived to the city. A radio was a luxury that only a few families were able to enjoy.

I remember as a young girl waking up in the dark to the sound of the merchants loading their goods on a horse–pulled wagon before departing, going from city to city, selling their wares in a market for their livelihood. The city's residents were not rich, but they earned their living honestly.

I took an active part in the daily life of our city, for example: one night the shochat (ritual slaughterer and examiner), Shmuel Yamnik, entered our home. By the way he was a distant relative of our family. He arrived with the butcher, Michael Hersch Noimark. He was poor and miserable and cared for by a larger family. He made his living by going from village to village buying calves for slaughter, and then sell the meat to the population. This man was very concerned, because the question surrounded the issue of whether the calf was kosher. My father didn't sleep the entire night. I heard him pacing in his library, trying to find a way to not to make the calf unkosher. For the butcher, it was a question of life and death. When I woke up in the morning, I could tell by my father's smile that the calf was saved. And that is how my father lived in the community, he felt their suffering and their joy, until the disgraceful Germans came.

[Page 160]

The Arrival of the Germans to Our City:

I will never forget the day the Germans took my father, and here I want to answer those who claim that the soldiers did not take part in the annihilation of our people. By the way, in our city, there were almost no Nazis, everything was carried out by the soldiers. On Rosh Hashanna (the New Year), most of the community was gathered in the main synagogue, and the others in smaller synagogues and yeshivas. In the middle of the prayer service, it was Yom Kippur, the Germans entered the synagogue. I stood and watched my father with admiration, wrapped in a kittle (white prayer robes), his face covered with a tallit (prayer shawl), completely focused in prayer. The Germans took him outside and shaved him. I ran after him. They gave him a wheelbarrow so he could clean the street. Many city residents tried to take the wheelbarrow away from him, but the Germans kept them away with the butts of their rifles. I moved closer, despite the beatings I took, and he looked me in the eye. I have never seen such extreme pain in his eyes. He was paler than usual, his face was white where he had had his beard since his childhood. It was as if he was naked, I saw his distress and there will never be forgiveness for his shame. Again and again, I tried to reach him, until I understood, despite my young age, that my father wanted to be alone, and he was ashamed at his nakedness. Before the war began, my father would write in the Moment and Togblat newspapers under the pseudonym, Yossela. And even then, with an almost prophet–like vision, warned what was about to take place.

Additional Text

Two years after the Germans established themselves and wreaked havoc in the city, a German resident came and notified my father they were planning to arrest him, so he had no choice but to leave his home and the city he loved so much and escape. He suffered terribly as he went from village to village on his way to Warsaw. Here, with a weapon in his hand, a weapon as his shield, a weapon of fiery belief, a weapon to attack, a weapon made from molten lead, he fought for the honor of his family and his people, and he will always be in my heart.

My father, the rabbi, fell in battle on the fourth day of the uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto, may God revenge them. His heroic death in his fight against the Germans is described in The Warsaw Ghetto Diaries, by Hillel Seidman. My mother, brothers and sisters tried to escape and save themselves. The children were young, aged 3 to 12; six people in all. My sister and I were taken to the camp.

I will never forget the day I came home from the Lojewo camp (Lavoye in Yiddish) on a furlough. My brother, who was three years old at the time, told me the dreadful news: “there was a death camp named Chelmno and they wanted to take us there, everyone, but I wouldn't let them kill me – I will escape, I want to live.” This is what a three–year–old boy told me. I stood silent and held him as he calmed down. He was the one who told me about Chelmno for the first time. You didn't run away, my dear brother, and there you were led, and it was there you were burned. According to rumors that reached me, my brother tried to run away, but the Polish henchmen caught him and handed him back to the Nazis. They took everyone else, and we remained alone, just my sister Esther and myself.

There are no flowers on my brother's grave, as there is no grave. Only one eternal question remains: why did they do this to us?

And let everyone come and demand justice for their childhood and teenage years that were abruptly taken from them, and for their adulthood, into which they will never grow and mature.

And let my brother Yehoshua come. He was eleven years old at the time. He had a promising future; they said he was a genius due to my grandfather. He would often stare at me with his wide gray eyes. And let Yoel, the redhead, come, and let

[Page 161]

Nehemia, the hero of the house come, the healthy and smiling child; and let Uda (אודה) come, she was so beautiful, and I remember how I brought her to the camp to save her. The little girl wandered around among us and we missed home. She would eventually return, only to depart on a route in which there was no return. And let Chuma come and demand her childhood, she was just six years old and such an angel.

And let Yankale come, my youngest brother, three or four years old, a master chess player. I remember the Commissar would come to play chess with him, and we would sit in the house shaking with fear that something bad would happen to the boy. My younger six brothers and sisters, all pure souls, were taken, never to return. Along with my dear mother. And a day will come when I will feel I must tell the story of my city and I will return to tell it, and everyone will come and appeal to me, “Don't forget me”, and I will return and fight the fight for their lives. I want to put this in writing, how you were so beautiful and so humble, and how I loved you so much. But I know this can never be done, because I loved you too much, all of you – every street and every person in the city, the old, the young, the infants.

Itche the Blond was quiet man; he was not well educated and not very wealthy. He was a tailor for women's attire. I had a feeling that Jews of this kind disappeared a long time ago. Each one of us has the duty to remember them and include them in the history of the Jewish people, because these figures have disappeared and are no more. And here he stands before you – a woman's tailor, husband to a paralyzed wife, never giving up and never letting his pain show. He never had children, and every day he sewed and in the dark of night helped others. He was the gabbai (caretaker) of the yeshiva, of bikur cholim, and also for a charity and book repair foundation. He did not make speeches; they were strange to him. He was a man of action. He collected money and distributed it to the needy, modestly and secretly in order not to embarrass them. He was economically responsible and lived within his means. I remember how, on Purim, he would send two of the older boys dressed as clowns to collect money as donations. No one dared to reveal their true identity and the city's residents contributed and gave money to the best of their abilities because they knew what it was for and where it was going.

I can still hear the bells' ringing going from house to house and Itche waiting for them. I was a young girl of ten, sitting at a sewing machine, waiting with him in the hope of being sent on a delivery. In the meantime, until the boys returned, he would sit and entertain me with wonderful stories told by the great rebbes (Admors) from Skierniewice and Kotzk, and the hours happily passed. Itche would tell exciting stories by candlelight until the boys returned with the donations. Itche would count the money and send them on their way. He would divide the proceeds into piles and then run to distribute it. It was explicitly forbidden to wait until the next day to enact the mitzvah – tomorrow would be another day. He was a well–known and humble person, a product of those times, and who knows if we will witness anyone similar in our generation who is able to continue his efforts.

There is much more to be said about my late father, about the significant role he played in the city's daily life and about his heroics in battle.

The heavens to which he prayed are witness; G–d in heaven, in whom he believed, is witness; as in the soil and land he worked so hard for in peaceful times, only to be halted during the war. And here is a young daughter commemorating her father, the rabbi, with eternal admiration. The respect and love transcend words.

Let history commemorate and remember, and let it tell the story of my father's righteous and pure life; and we will continue, and we will be satisfied, and we will live with what you have built.

by Fishel Goldman

Translated from the Hebrew by Marshall Grant

© Roberta Paula Books

The members of our family included my father, Yehiel Goldman, my mother, Sarah Lantzitzki, two brothers and two sisters.

When the war broke out in September 1939, my brother Michael Hirsch was conscripted into the Polish military and was taken prisoner under unbearable conditions. According to the testimony of Abba Buks, who was also a prisoner, but escaped, the Germans began to eradicate prisoner of war camps around the end of March 1940 by shooting the inmates. The camps were located near the city of Bielsk Podlaski. When the Jews of the city heard that the Germans were murdering Jewish inmates, they tried to pay a ransom for their rescue, but to no avail.

On April 28, 1940, we received a letter from the Bielsk Podlaski community saying that my brother, after being killed by the Germans, had been brought to a Jewish cemetery for burial.

Those in the prison camp remembered two more residents of our city, the brothers Hanan and Monish, the sons of Lev Klodawski, and they too were murdered. According to Abba Buks, who was together with them, they stood embracing each other as they were killed by the Germans. According to Buks, the soldiers were from our city, and before they carried out their task they suggested (to Abba Buks) that they run and save themselves and said, “you have a family, run away!”

And thus began the problems in our city, like every other city in the vicinity. Jewish families were thrown out of their homes and sent to a Jewish ghetto, with just a few of their household belongings, in the vicinity of “the old market”. Even before this expulsion, the ghetto was already suffering from overcrowded housing.

After being expelled from their homes, those exiled were also disconnected from their means to make a living and had to make do in any way possible, selling household items for example, the few that remained after being transferred to the ghetto.

Some of the younger men, and a few of the older ones, were already in labor camps. Those remaining in the city, me among them, were made to work at various tasks of forced labor. The supervisors were “our friends from yesterday” and would often use whips to urge us on in our work, men and women as one.

In August 1941, I was sent with a group of young men and women to a labor camp. After two days of travel in cars intended for cattle, we arrived in Tuczno, a camp near Inowrocław. My two sisters were there. We worked for three months in a sugar factory under the supervision of Polish policemen. We worked hard, but the conditions were relatively bearable.

From Tuczno we were transferred to a camp named Yanikovo, and our situation became worse. The camp's main cook behaved cruelly towards the inmates, and every day he would murder 5-6 of them. Twice a week, we would be called out in the middle of the night to be counted. The snow was a half-meter high, and we were made to stand half an hour, sometimes an hour, without moving. Of course, the next day some of the prisoners were sick, which is when the killer again used his gun. He would say this is not a hospital, it is a labor camp. The inmates who were able to go to work were beaten until they were bleeding. Some of them escaped, but were caught and brought back - to be hanged, an act carried out in public. All the inmates were made to wake up in the middle of the night, stand

[Page 163]

and witness the execution. One of those hanged, before the noose was tied around his neck, shouted out loud, “Let freedom live!” The Polish murderer approached him with an axe and split his head open. You wanted freedom, Jew, well now you have it.

After the war, I was the sole witness in the Polish court where the murderer was tried. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. The judge told me that if there had been one more witness the murderer would have been sentenced to death.

My sisters were in the Leawa labor camp. They advised me to escape from the Yakshitz labor camp, where I was now held, and I went to them. The camp commander concealed me for two weeks until the searches for me stopped. I would then go to work regularly with all the inmates, and in May 1942 we received shocking news, the destruction of Przedecz's Jewish community and the destruction of all the Jewish residents by poisoned gas in the Chelmo death camp, among them my father Yehiel Yosef Goldman, my mother, Sarah and my sister Yatka, who had been previously released from the camp and sent home. My G-d avenge them.

In October 1943, I was sent to Auschwitz, where I received number 144324. Accounts of the horrors of the Auschwitz death camp could fill a book – the torture, degradation, cruel beatings, marching to work escorted by bloodthirsty dogs and … the orchestra. I was in Commando 101 and lived in Block 27. In January 1945, four days before the liberation of Auschwitz, the Germans moved us to the Gliwice camp. On the way, along the Czech border, the Christian population threw us loaves of bread. After four days of travel in which no food was distributed, I took a chance, as others did, and jumped from the slow-moving train to catch a loaf of bread, however the Germans shot at us with their machine guns. I was slightly injured in my forehead, and I was unable to enjoy the bread. We continued the journey to Gliwice. We stayed for 12 hours. The more the Russians advanced, the Germans pushed us forward, Oranienburg, Flossenbürg, and others.

by Y. L. L.

Translated by Roberta Paula Books

© by Roberta Paula Books

You live in a town, and it seems as though you know all of the people: all the people, all the stones, every tree, every building, everything. Not on purpose, you observe your neighbors from near and far, at weddings, funerals, circumcisions, Bar Mitzvahs, on holidays and on the Sabbath, on a regular work day. You have compassion for the sick, the old, the poor, and those who don't know what to do with themselves. You know everyone's nature and cries, sadness, joys and laughter. You have no doubt that in the simplest person, exhausted from hard work and poverty, lies the highest level of humanity, heroism, intelligence. The highest level of true humanity.