|

|

|

[Column 19]

Jezierzany: Segments of History and Geography

by Dr. R. Ben–Shem

Translated by Meir Bulman

The town was located in the Podolia region, a land blessed with fertile ground. It was near the Ukrainian fertile lands on one side, surrounded by hills and steep Carpathian mountains on the other side. It was close to the Nizlava [? ניצלבה] River. Our town, Ozeryan, (Jezierzany in German and Polish; Ozeryany in Russian and Ukrainian) was located near two relatively large ponds and small mud–ponds. A secondary descriptor was added to the name as a topographical marked, Jezierzany– Pylatkivtsi[1] [? פילטקוביץ] or Jezierzany near Chortkov. Jezierzany was surrounded by villages, the most notable among them Lanowce[2], Pylatkivtsi V'Zhlinice [? וז'יליניז], Zlisia [? זליסיה ], and Bilzia [? וילץ]. Larger neighboring towns are Korolówka, Borszczów (the district capital), Probizhna, and Tovste, which all contributed to Jezierzany's economy with their fairs.

We cannot affirm the date our town was founded in general or as a Jewish community. We are certain that Jezierzany has a rich history, as the history of Podolia is rich and ancient.

According to archeological excavations in the area, we know that by the 5th century B.C., the Greeks found residents with light hair and blue eyes. Later, the Romans controlled the region as well. Thousands of Roman coins from the periods of Trajan and Hadrian indicate a large trade in the area. Christian writer Tertullian notes a few nations (the Sarmatians, Skitinas[?], and Dacians) who resided in the area. It is plausible that in the days of the Second Temple, Jews traded

[Column 20]

in the extended area from Southern Europe to Volhynia and Podolia[3] and after the destruction of the temple may have even settled there.

All those nations left their marks on those countries. Several towns still carry the names of the first Celtic settlers, e.g. Delatyn, Rohatyn, and Sniatyn. Several bodies of water in the region also end with “tyn.”

Victors and losers passed through this historical kaleidoscope. Many nations fought, wandered, settled, intervened, and assimilated her. Various ethnic groups that came later inherited the previous residents' land (be it through victory and expulsion or by assimilation). After the Celtics, Greeks, Romans, and Germans (who wandered from west to east[4]) came various Mongols, Tatars, Khazars, Turks, and Rusyns, followed by Russians and Poles. Eventually, the Western empires also left their marks on Podolia. Podolia passed from one state to another and was divided at times. Although Podolia was a single region, some parts of it remained in the hands of one state and the other parts in another state. In 1772, Podolia was divided into two parts: the North–West controlled by Austria and the South–East controlled by Russia.

It can be accepted [assumed] that what transpired in Podolia did not skip over Jezierzany. Although Jezierzany was not situated on a central crossroads, it was close to the crossroads

[Column 21]

that lead from Ukraine, Volhynia, and Southern Europe towards Western Europe and the north.

While wandering and battling, the first tribes visited the area and maybe even settled in it. In the 13th century, during the Mongolian invasion through Southern Europe to the west, the Tatars erected their tents there and left behind a permanent residence[5].

The geographical and topographical composition of Jezierzany and its surroundings was typical of Podolia: curved plains, hills, average mountains, lake lands, ponds, thick forests, small mud huts, and agricultural fields. A very rich land, Podolia has large swaths of agricultural fields stretching across vast distances. I recall the green fields and golden shade of wheat crops alternating with the silver of other grains, the barley color. The Polish roads, (wobbly and treacherous), swamp lands, high snow in the winter. The land of predictable rain and the comfortable, bright, warm sun of the continental climate.

The town, like its neighboring towns, was built in the typical Polish–Ukrainian fashion. A large, square–shaped marketplace was located at the center, decorated by Jewish homes; an exception was the non–kosher butcher shop in the later days. At the center of the marketplace, the water well proudly served, a well from which Jews drew water either on their own or aided by water–drawers, life–nourishing water being drawn from the depths of the ground to their buckets and homes.

|

|

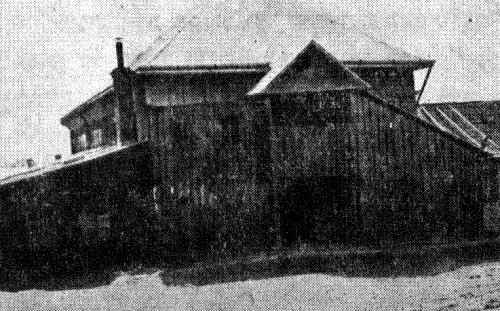

| The Great Ancient Synagogue (exterior) |

[Column 22]

At the edges of the market, the roads in all directions intersected. The road from Chortkov arrived and continued to Borszczów, the district capital. That intersecting road at the marketplace led to the road to Pylatkivtsi; beyond Pylatkivtsi, the road ran to neighboring Constancia.

Like all rivers running to the sea, so, too, all roads and alleyways led to the market. Behind the first row of Jewish stores, which served as a sort of curtain, were the stores that sold pork. A narrow lot separated the stores from the supposedly glorious city hall which was topped by a tower. To the left, along the street leading to Pylatkivtsi, was the real Jewish street, Holy Street[6]. That street included the wooden synagogue, wondrously carved by an artist. Diagonally to the right was the study hall, which was lower [?in height] than the synagogue but large, and near it there were other synagogues. As in many other towns in Poland and Ukraine, the marketplace served as a gathering place, social club, source of income, and walkway. The weekly fairs took place there and the police declared ordinances, laws, and decrees by city hall. The large streetlights were lit there. The corner merchants sat there with their goods for sale.

|

|

| The Great Ancient Synagogue (interior) |

We do not know the origins of Jewish Jezierzany. Perhaps the Jewish presence there was ancient,

[Column 23]

as in nearby towns, where Jews had resided since the days of yore.

The activity of Jews as tradespeople and connectors between east and west is quite ancient. The influence of the Khazar Khaganate[7] strengthened the Jewish element in southeast Europe, including Podolia. By the 10th century, rich Jewish men lived in Poland which indicates an influential, large Jewish community. As Poland formed, Podolia was a part of Poland.

|

|

|||||

| Tombstones in the New Cemetery (Chaim Zeidman's parents' tombstones) |

||||||

Therefore, it can be assumed that in the 13th century,[8] soon after the founding of the town, Jewish merchants visited, later settled in the town and were joined by other settlers. Nothing survived from the ledgers of the ancient community but the legacy established [proved?] that the history of the Jews in our town was rich and varied.

The first Jewish institutions, the synagogue and the cemetery, were constructed by the end of the Middle Ages[9].

[Column 24]

Each generation passed down [shared the information] that the Great Synagogue was ancient and that all the fires that had burned in our town (they burned very frequently and devoured wooden buildings like cattle devoured hay) skipped over the synagogue and it was unharmed. It is also known that the synagogue was reconstructed after the town and its Jewish population were decimated (likely in the 1648 uprising). The cemeteries also show signs of being ancient, although their ages were not tested scientifically. The age of the old cemetery is in line with the age of the Great Synagogue and the established Jewish community in the town (the end of the Middle Ages, 14th–15th centuries).

Great rabbis' tombs were in both cemeteries. Rabbi Velveli, a descendent of the Baal Shem Tov, is buried in the old cemetery. Rabbi Yeshayahu HaLevi Heller, a descendant of the Tosafot Yom Tov[10] is buried in the new cemetery. Candles always burned at both gravesites. More candles were lit when more visitors attended in the months from Av to Tishrei or on days of communal trouble.

The town was part of the Polish king's estate. The king paved a road from Jezierzany to the Pokucie [Pokkutya?] region. In 1756, Jezierzany was transferred to Vazlav Zhbuski, [?] a royal military leader. Starting in 1717, a group of armed soldiers resided in the local winter camp.

The recent history of our town began in the second half of the 18th century. Many people spoke of Jezierzany because of the Frankist movement and the long time it took to relinquish the cult. However, the veteran residents of Jezierzany were harmed by the reputation Jezierzany had gained.

It is difficult to know whether the messianic Sabbatean[11] movement penetrated Jezierzany. However, Jezierzany's proximity to southeast Europe and Turkish influence likely facilitated the spread of the Sabbatean movement in the town. The term “Sabbatean” was mentioned in hasty anger. The Frankist[12] movement or, more correctly the movement's survivors and fighters, found in Jezierzany a refuge and perhaps a place to prepare for battle. Until the Holocaust, “Frankist” was a harsh insult. The Frankist history helps to piece together a history.

The Frankists escaped from the Buczacz area and retreated to Jezierzany. They likely found a spot rife for activism or they thought they could more easily regroup in a remote place.

[Column 25]

The Frankists' influence on Jezierzany was substantial. They knew how to conquer hearts and settle financially. The Council of Four Lands boycotted the cult and the whole town nearly was harmed. Jezierzany eventually saved the Talmud from a decree of burning.

At that time, a famed advocate of the Podolia region, Rabbi Shimon Herschkowitz, lived in our town. Shimon traveled to Kamianets–Podilskyi to defend the Talmud before the Bishop during the bitter debate with the Frankists, in which he defeated them.

The battle also raged in nearby towns. We know that towards the end of the 18th century, the Frankist movement disbanded. The remnants of the cult were erased from the earth. The Frankist movement was also erased in our town.

Economic conditions enabled the Jews to remain in the town and develop it, thanks to the town's communicative [outgoing?] nature and the neighboring villages. Religious and charitable institutions were opened (sick care, a wedding fund, a burial society, etc.). Institutions first formed in the personal, primitive style customary in Poland and Ukraine and then developed into more organized structures.

The town attracted scholars and rabbis who came from afar to serve as rabbis. The formation of disputes over the rabbinate indicates its importance.

The town's ethnic composition changed several times. The percentage of each ethnicity in the population changed, though not the [overall] population size. The population was comprised of three primary ethnicities: Rusyns (called Ukrainians after their national awakening in the 20th century), Poles, and Jews. The makeup of the population remained similar because of assimilation with the earlier nations in the region. We do not find Germans (traders or settlers) in the Jezierzany area. Also absent were Czechs, Hungarians (who were part of the Austro–Hungarian monarchy) and other ethnicities. There were differences in the balance of power among the ethnicities but they were politically motivated rather than ethnically motivated. There were times when the Rusyns were the governmental element,

[Column 26]

and at times the Poles were the main political and cultural element of the town.

Those nations left their mark on the town. The Poles were Roman Catholics and the Rusyns were Greek Catholics. Poles and Rusyns differed in their customs, language, dress, and culture. They equally hated Jews. The sides were always involved in constant political and cultural disputes, and the Jews sometimes acted as tie–breakers. In a tie breaking scenario, the Jews did not win the sympathy of the winning nation but did incur the hatred of the losing nation. Since the partition of Poland in 1772, Jezierzany, along with Western Galicia and a region of Podolia called Eastern Galicia, were handed over to the Austrian monarchy. Jezierzany was leased to Resvoski Savrin [?]; his son, Leon, sold it to prince Leon Spiha [?].

Vienna established a special position towards Galician Jews. The position included three prongs: 1) Germanization of the general population, aided by Jews, 2) a fiscal goal of increasing the state's revenue by taxing Jews, and 3) an economically utilitarian goal of transferring Jews into branches more productive to the state. Still, Jews lived safely then, without inner turmoil.

The Jewish population grew over time, both in quantity and quality. The number of rich and influential Jews increased[13]. Although there were ups and downs, the town developed and the influence of Jews upon it strengthened.

Starting in 1848, (the revolutionary period), the central government changed its attitude towards Jews. The authorities treated the Jews more liberally, allowing Jews to reach a certain degree of economic emancipation. The ancient foundation of Jewish life and community was affirmed and

[Column 27]

its leaders enjoyed official governmental assistance. Political recruitment of Jews flourished. The three governing factions of the town – the central government (Vienna), Poles, and Rusyns – wanted to strengthen their influence on the town and attempted to influence the Jews to support their platforms and candidates for national and municipal office. The Jews, who still did not wish to form an independent political faction, were pulled in many directions. Thus, Jews were battered by a system of competition and triple hatred.

At the same time, our town participated in the struggle that took place within the Jewish world among Hassidim and their opponents. It is difficult to assess whether in Jezierzany class differences were also the basis of the division between Hassidim and their opponents, where the rich fortified their position in the opponents' camp while the poor found consolation and strength in mystical Hassidic customs and tradition. Our town residents were attentively involved in that process. Later, Jezierzany produced many representatives on both sides who served as guiding lights for many.

Several rabbis came from the distant Nemyriv to Jezierzany to serve as its chief rabbis, including Rabbi Mordechai Zeidman. Following him was the ADMOR[14] Rabbi Velveli, (although he objected to being called ADMOR) whose power and influence were extensive. Rabbi Velvel remained in the memories of many town residents. Later, Rabbi Fishel Arik, who gained fame also beyond the borders of Poland and Galicia, served as rabbi.

Two figures appeared and illuminated the darkness in our town: Moshe Shulbaum and Aaron Blumenfeld[15].

The relations among the Jews and their gentile neighbors worsened. Vienna's policy of Germanization through the Jews increased the gentiles' negative attitudes. Two especially dark days testify to the hatred of gentiles towards their Jewish neighbors and their limitless murderousness.

[Column 28]

The first was Black Sunday in 1902 when the train tracks were constructed. The second was in 1917 as the Russians retreated from the Chortkov region and our town. Ukrainian shkotzim[16] entered our town and murdered men, women, and children.

E.

The Jewish population increased. 2,608 people resided in Jezierzany and an additional 910 people in Jezierzanka[17] village. Usually the population of the town was nearly all Jewish. Jezierzany entered WWI (1914– 1918) as a flourishing town with a stable, if not abundant, economy. The town's communal life was organized, combining tradition on the one hand and enlightenment on the other. Seeds of Zionist awakening grew stronger in the hearts of some. However, WWI wreaked havoc on our town. The region was a battlefield and a base of the Russian advancements and retreats. That brought with them destruction to the Jewish population as Russians came and left.

Jews displaced from nearby towns strengthened the fear and feeling of powerlessness. Only aid and comfort (financial and spiritual) from Russian and American Jews allowed them to hold on and not collapse. As the war ended, the struggle between the Ukrainians and Poles increased, bringing destruction. After the battles ended, the town stabilized slightly but never fully recovered.

The best among the town's youth understood there was no point in remaining in the diaspora, which sparked the strength of the Zionist movements on the one hand and general emigration on the other. By 1914, dozens had immigrated to America but only a few immigrated to Eretz Israel (among them was the pioneer C. Zeidman), and the number increased to hundreds. Ukrainian cooperatives and the banishment of the Jews from employment, encouraged by the Polish authorities (who had ruled since 1920), clearly proved the intentions of our Christian neighbors, what they had done and what they would do.

[Column 29]

Jezierzany was still broken when it was thrust into WWII. It entered the war, was destroyed, and never was rebuilt again.

The Holocaust plagued Jezierzany, too, in its full cruel force. The destruction of Jezierzany added a final page in the black ledger of Polish Jewry which was destroyed, leaving only remnants to wonder, wander, and search for a solution to the fate of the nation that paid a hefty price for living in exile on foreign land.

Bibliography:Matityahu Mizsh [?]

Ledgers of the Council of Four Lands[18]

Yitzhak Schafer

Vienna Governmental Archive

N.M. Gelber

Biblioteca Usulinskice

|

|

| Olim (Avraham and Tzilah Steining) |

Endnotes:

Note: Many definitions are taken from Wikipedia.

[Column 32]

My Memories and My Life Story[1]

by Yehuda Cohen

Translated by Meir Bulman

A.

I was born on Nisan 8, 5621. I am Yehuda ben Chaim Zvi ben Avraham Moshe ben Alexander ben Yosef ben Yehuda ben Yisrael HaCohen. I was born in Jezierzany which is near the Russian border. On my mother's side, I am the great-grandson of Rabbi Mordechai ben Yehuda Dov Zeidman, ABD[2] of Jezierzany, a descendent of the holy Michel of Nemerov. My mother was Devorah bat Moshe ben Mordechai. My father originated 2from the Cohanim who left Moravia for Poland. Some say we are descended from Rabbi Shabbatai HaCohen, author of Siftei Cohen, and some say from Rabbi Naphtali Katz and Rabbi Pinchas Yosef Cohen, whose lineage is traced to the Maharal[3].

The name Jezierzany indicates ponds and indeed, one could find many small ponds. It is situated on a small hill. During my childhood, the town became one big pond full of mud, as there were no paved or dirt roads. I recall that once, as I walked to cheder[4] when I was a skinny, small, weak boy, my path led me to the center of the marketplace where many wagons passed. I was stuck in a bottomless swamp and I almost drowned. I feared for my life, feared that the ground would swallow me whole.

My father educated me according to his ways, meaning that he did not send me, as a toddler, to cheder to learn the aleph bet. Instead, father literally fulfilled the mitzvah of “thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children” and taught me reading. My father was not fond of the practices of the cheders for beginners. He taught me using his preferences. He knew that, like all children, I liked drawings so he used drawings of various animals to teach me the alphabet. He drew a stork for me; it was standing on a tall leg with the letter aleph in its beak. I asked, “What did the stork catch in her beak?” and my father answered, “aleph.” It settled in my memory and the letter aleph stayed with me and I never forgot it. Father also did so [the same] with the rest of the alphabet. Thus, I was literate within a short while. Because he never bought me toys and I had no other way to spend time, the letters which my father taught me occupied my mind all day. I was bored so I constructed and spent all day playing my own game, arranging matches in the shape of the Hebrew alphabet. I did so very artistically and with such great skill that all those who saw me were amazed and praised my talent.

When I reached the age of bible study, my father entrusted my learning to a teacher who came to my town from Bukovina, Berrel Sadigerer [?]. My father sent me to study with Berrel on the condition that no more than six students would join the class. My father took the role of inspector and almost every day came to the cheder to check whether Berrel was keeping his word and was fulfilling his role well so the students will not cease their studies. While at Berrel's cheder, I began learning some Talmud, to which father objected, saying that I was

[Column 33]

too young to study such difficult material. Berrel pleaded with my father to allow me to study Talmud, claiming I had great cognitive ability including a great memory. My father dared not refuse, lest he look like a heretic in the eyes of the teacher.

My first studies in Talmud were, as was tradition in those days, the financial laws in tractate Bava Metzia[5]. I started with the Mishnah portions of 'shnayim ohazin'[two hold] 'hamenicah et hakad'[he who places the jar] and 'hamfkid' [he who deposits]. Then, I progressed to simple Talmudic text with Rashi commentary in whichs, at times, the first passage consists of mid-topical phrases such as “the rabbis said” or “therefore.” Shortly thereafter, I left that cheder for reasons I cannot recall and joined a Talmud teacher, Rabbi Meir from Ternopil. Meir objected to the simple study of Talmud and began teaching me more advanced topics. I vividly recall that when he taught the topic, “and Rabbi Yehoshua admits” which he translated into Yiddish, he formed his hand into a fist with an outpointing thumb, which he rotated clockwise, enthusiastically in a victor's tone. I had to imitate him and use the same melody, although I did not know what Yehoshua disputed which he now concedes, who Rabbi Yehoshua is, or who forced him to concede what he had denied.

On Shabbat, I went to be examined by town scholars. There were two such examiners in my time, Rabbi Berrel and Rabbi Aharon. Berrel was indeed a great scholar but was a tough nut. During the exam he showed me his power of pilpul[6]. Not only did he almost always determine I did not know my studies, he also angrily dismissed me and did not give me Shabbat fruit. Because the choice was mine which rabbi would examine me, I usually chose Rabbi Aharon. Aharon was of a kind and compassionate nature, a childless man who loved children. He never burdened me, only listened silently, calmly, smiling pleasantly. I recited what I had studied and Aharon did not stop me with questions or problems. After the exam, he slid his palm across my cheek and said, “Good boy.” His childless wife, who was also kind and loved children, gave me raisins or cherries after every exam and lovingly kissed my forehead.

My youth generally was sad and empty and I rarely laughed. Still, at times, childhood broke through the dark clouds and I passed hours of casual laughter and play. I especially enjoyed

[Column 34]

days off, Shabbat, and holidays when I was rid of the cheder, days which occupy an important part of my mind to this day.

I had a pleasant singing voice. I was a leader among the singers. Each winter when I left the cheder after nine hours of study, I would hold a lantern, my strong voice (high soprano) piercing ears as I sang the new tune from the last Simchat Torah. One of those typical tunes stayed in my mind to this day and there is no way I can forget it. It is a shame I do not know musical notes to record it here.

When a guest cantor would arrive at the big synagogue, I would leave the kloyz[7] against my father's will, and I struggled through the large crowd that came to listen to the melodic cantillations of the cantor and his choir. It is difficult for me to describe the pleasure I felt when I heard new tunes. I was not aware of the overcrowding and prolonged standing. I frequently acquainted myself with members of the choir, children my age, who taught me pleasant prayer tunes which the audience loved the most. Some prayers from those good old days are still in my head and accompany me as I go to bed and as I awake. The synagogue, with its cantors and singers, was my place of entertainment as a child, a similar role that theater and film play in the lives of today's youth.

Long walks and exercise in nature were also very influential in my childhood. At the bottom of the hill of my town, there was a large lawn called the Tulica[8], open to all town residents. On Shabbat and holidays, it was a resting spot for the horses owned by Jews and their owners also came to relax. From midday to nightfall, men and women came to breathe fresh air and show off their clothes and fancy hats bought at the neighboring Lashkowce at the annual Ivan fair which took place on July 7. My cheder friends and I were among the main attendees and we were never absent from the Tulica. We competed in running and jumping, skipping on rocks and crevices, and various games that only childhood can invent.

[Column 35]

Playtime occupied our free time and renewed our health and the color in our cheeks which were damaged by the poorly ventilated cheder.

Sometimes we were tired of lounging in the limited plain of the Tulica and we journeyed to the neighboring village, Constancia, which was within the religiously permitted Shabbat boundaries. On our journey, we saw fertile fields which Podolia was blessed with. We picked all kinds of flowers and learned the names of each plant. Thus, I developed a love for nature and a desire to work the land, along with great sympathy for land workers. One of my friends at the cheder was Moshe David whose father leased an estate. The large estate and its fields were not far from my home. There were tall haystacks on which I and my cheder friends jumped from the top to the bottom haystack. It was a miracle that we did not break our necks. At the granary, there was a large threshing machine and horses carried the machine in a circle. As the machine turned, we held on to its rods, despite that wild ride being forbidden. Those stolen waters were sweet to us, the more dangerous the activity – the better.

Moshe David's mother supervised us whenever we came to her house or the large garden which stretched between the house and the granary. There I learned to differentiate between sprouting apples and cherries. The lady showed us her strength in working the garden beds. I shortly acquired much knowledge about planting various vegetables, weeding the lettuce and beets, and harvesting Turkish wheat and potatoes. That knowledge instilled in my heart a deep love for farming.

B.

My father was a pupil and friend of Hebrew philologist[9] Moshe Shulbaum[10] and tasted some of the enlightenment that penetrated the darkness of small towns. My father was made uneasy by the ancient form of teaching, which

[Column 36]

stressed Talmud study and treated the bible as secondary. Father battled teachers who taught no bible other than the weekly portion with Rashi. Once a week on Friday morning, he pleaded with teachers to teach more bible and to teach it in its simplest from without additions or excessive commentary. After his words fell on deaf ears, he removed me from the cheder and placed me in the care of a bible teacher, Alter Fishbach of Laskowce (Father of Zusman Fishbach, who is now a Hebrew teacher in Baron Hirsch's school.) Alter fulfilled my father's requests and taught me bible until I acquired broad knowledge and could understand the bible as written and not only from quotes in the Talmud.

I do not exactly recall when I learned foreign literacy, especially German, the need for which was already sensed by many residents as a must-know. I learned foreign literacy in a speedy manner, quite easily and casually. At first I learned from my father and then from the teacher (I think his name was Gina) at the local normal school.

In those days, teacher H. Shmetterling of Chernivtsi arrived in my birth town. He wore modern clothes. He founded a school in our town and I soon enrolled. The school made a profound impact on residents of the town. It was truly tumultuous and divided the town into two camps. One side warmly embraced the teacher and enrolled their sons and daughters in his school. The other camp was staunchly opposed to the teacher and persecuted him, dubbing his efforts “death in the pot of enlightenment,” and concluded by saying “our ancestors did not study German, yet lived long and prospered.”

The opposition leader, known as Reb Velveli, was a descendant of the holy lineage of Rabbi Binyamin Ze'ev Gattessman. He was a town favorite in those days. I had not yet mentioned him in my memories because my father was not among his admirers and I never set foot in Rabbi Velvel's home.

I still recall an event involving Rabbi Velvel. One Shabbat, my father and I prayed at Molly's Kloyz. As the congregation reached the recitation of Shema, Rabbi Velvel entered the synagogue, and ascended

[Column 37]

the pulpit. He slammed his hand on the pulpit and announced, “Silence, people! Although it is not permitted to stop in the middle of the Shema, it shall be done for the sake of a mitzvah. A heretic named Shmetterling has arrived in our town and is encouraging our children to sway from the righteous path and do as the Gentiles do. He teaches them treif[11] forbidden material, God have mercy. I hereby declare that any God-fearing man should not give his son or daughter to that heretic, lest he be punished and meet a bitter end. He who obeys will be blessed, etc.”

Rabbi Velvel's appearance and his proclamation happened so quickly that the audience at the synagogue stood still in shock and awe. They barely noticed Yaakov David HaCohen, who declared loudly, in an angry voice, “Who appointed you God's policeman? We will not obey you and do what we feel is right.” But Rabbi Velvel left the synagogue quickly, as he feared the congregation's reaction. Services were quickly concluded and groups of people stood and discussed the event, its reasons, implications, and heroes.

I studied in Shmetterling's school no more than an hour a day, despite the twinkle of enlightenment, as secular studies were second to Torah studies, which I studied from morning to evening. My father and other residents did not dare interrupt that order.

The time was the 1870s after the Austria-Prussian war and Polish became the dominant language in all government offices. Thus, the need to teach Polish to Jewish children was sensed. Shmetterling, who did not [?] speak only German [? translators note: this is unclear], had to resign his position and a different teacher took his place. The new teacher was Yaakov Reiser, who arrived from western Galicia and was fluent in Polish. I learned Polish literacy with Reiser but not for long. Reiser neglected his work and disparaged the importance of German, which was [not?] the official language [translator's note: the intent is unclear] which he did not know. Additionally, Reiser's students did not absorb the material well and studies were limited to plain writing and did not touch even on grammatical structures. Thus, one by one, his students, including me, left.

[Column 38]

C.

Meanwhile, Hebrew author and philologist, Moshe Shulbaum, a native of my town and my father's friend, founded a school in our town. Moshe fought an existential fight his entire life; at first, his income depended on advocacy but when the government declared it illegal, he realized the risk and took up Torah teaching instead. However, he did not earn much [money from] teaching. As his sons grew up, he desired to convey to them a modern education. Therefore, he travelled to L'viv where he and his friends, members of the group “Hebrew Language Seekers,” published the weekly Ha'et and Kol Ha'et. As it was wartime among Germany and France, there was no lack of writing material and there were readers aplenty. His sons, Reuven and David (who later died at a young age of tuberculosis), enrolled in secondary education. Moshe was content with his lot in L'viv and nearly forgot his poetry although his income was limited in L'viv too. Hebrew journalism was less like a fat milking cow and more like a thin goat which produces little milk with much difficulty.

As the French-German war ended, journalism dwindled, especially Hebrew journalism in Galicia, due to a lack of readership. The Jew is naturally kept busy with his business and considers reading the newspaper as a luxury for the idle. Thus, Shulbaum's newspaper rested in peace. At the advice of my father, Shulbaum returned to his birth town and open a school. Shulbaum's school fulfilled an important role in our town. Only the children of the town's enlightened and Shulbaum's acquaintances were accepted to the school. I was among the first students and was joined by six additional students. Shulbaum taught us a) bible translated into German, b) Hebrew language and grammar, c) German language and grammar, d) geography, and e) mathematics. All those studies were considered secular and so we studied only three hours daily. After morning prayers until midday we studied, while the rest of the day was devoted to Talmud studies at the cheder. Thus, a complete separation was enacted between the secular and Torah studies and they did not touch one another. Shulbaum's teaching left an unforgettable impression on us. I vividly recall

[Column 39]

after his first class I told one of my friends that was the first time in my life that I fully understood the class material. In that one hour I learned so much material, more than from any teacher who preceded him. Although I was mature by the standard of the time, I still laughed and played with my friends, both at the secular school and at the cheder. We played happily and mischievously, and although childhood was confined within the boundaries of constant study, childhood did not forego its right.

The substance of our play was generated by the school or one of the teachers. Shulbaum taught us in a small room with one window, with blinds which served as a barrier at night. When the teacher left the room for a moment, we shut the blinds which quickly darkened the room. In the dark, we were called to mayhem and childish mischief, and childhood relentlessly demonstrated its power. When the teacher opened the blinds, we each sat in our seat in such apathy that the teacher could not know who was more delinquent and who was responsible. The teacher's investigations and demands for the criminal were useless, as no student dared to inform on his friend.

After I acquired knowledge of geography and taught myself to artfully draw maps, I used that knowledge for childhood games. I sketched a map of our school and all the surrounding houses and marked on the map six different ways which led from all over town to the school. My friends and I decided that on each day of the week, we would use one of the paths according to the map, without deviation. Of course, I led the way and my friends followed, seriously and carefully. Because I could only find six paths, we used the same path on the seventh day, but with a change - climbing a rickety ladder which stood by a crumbling building and climbing down the stairway on the other side. That climb up and down was carefully marked on my map which served me like a commander's battle map. When our teacher learned of that,

[Column 40]

he laughed at our childish game yet still scolded us. Of course, we were embarrassed by him and the tradition of geographic circling [exploring] was cancelled.

D.

The secular studies, taught by a skillful teacher such as Shulbaum, captivated me to the point that I began to neglect Torah studies and my attendance at the cheder was for the sake of appearances. I spent my time at the cheder but paid no mind to Talmud lessons. My teachers noticed my neglect and scolded me more than once. Still, they dared not punish me or complain to my father because I was already “grown” (12!) and enjoyed the same rights as grown youths. Those who were grown had the discretion of studying or not, as long as they could repeat the material in an oral exam. I tested well despite neglecting my studies. My teacher was amazed by my talent. I did not listen at all to his lesson and, during class, I played with small sticks with which I constructed small buildings. I paid so much attention to my buildings that Shlomo Meiri, my teacher, called me “the builder.” Yet, when the time came for the examination, my friends did not demonstrate the degree of knowledge that I did. The teacher asked me, wondering, “How did you know? You were building when we learned.” I probably paid more attention while constructing my buildings and absorbed the material.

E.

After I reached Bar Mitzvah age and my reputation in town was that of a quality person, matchmakers began coming to father's home and proposed to him matches for me. Each proposed match brought its own description, like “a great success,” “the gift that keeps giving.” Potential fathers-in-law began arriving from all over the country. Potentials came with examiners to test my knowledge of Tosafot[12] or Mahrshal [?]. Because I favored a simpler method of Talmud study and objected to all the peppering, I did not satisfy the examiners who left, shrugging their shoulders and scowling as if to say, “This boy is not worthy of his reputation and does not know at all how to study.”

As was the tradition in those days, my Bar Mitzvah was celebrated modestly

[Column 41]

and simply. My father approached Rabbi Binyamin Eliezer of Chortkov, who was a great scribe and a God-fearing man, and ordered a pair of tefillin[13] for me. Meanwhile, I studied the laws of tefillin and began strapping tefillin in a small synagogue on 8 Nisan 5634, my thirteenth birthday. My father brought liquor and baked goods for the congregation at the synagogue. After I was summoned for the reading of the Torah on Shabbat, my father made the blessing noting the end of the transference of my sins to him. Thus, I was now Bar Mitzvah, a grown man who is responsible for himself and his brethren.

F.

My father had a first cousin, a native of my town, who was wealthy and leased land at Orekhovets, a village near Tovste. The cousin had four daughters, the oldest of whom was about two and a half years younger than I was, 12 and six months old. I did not know the girl well. I saw her once in my grandfather's home and my father asked me many times after that whether I liked her. His question was quite strange to me. I replied that I had not thoroughly looked at her thoroughly. That was the truth because I had no interest in girls at that point. However, my father kept that on his mind, likely because he was tired of all the “articulated” match proposals and wanted to find my match on his own. One bright summer day, the aforementioned cousin arrived by carriage at my home and was to stay the night. Many relatives and acquaintances arrived for dinner. The cousin, who was a scholar and a pupil of Rabbi Mordechai Zeidman, tested me and asked me to explain to him some commentary on tractate Ktubot[14] and show him my handwriting, which I did. After dinner, I went to bed not knowing that that dinner concerned me and my future. When I awoke in the morning, my father wished me “mazel tov” and notified me that I was engaged to my cousin's oldest daughter, whom I had seen once in my grandfather's home. My expected father-in-law also awoke early to be on his way and, before he departed, gifted me a hundred silver coins and requested that I study well and write him.

So, at fourteen years old, I became a groom in Elul 5634. I now had to care for a bride and a father-in-law,

[Column 42]

and was burdened by correspondence with them. I felt like an adult, obligated in mitzvot, for all intentions. The skies of childhood began to be clouded by seriousness.

G.

Yet, I cannot say that the days of my engagement were sad. My parents had never made big gestures to show their love like other parents, although I was an only child (my parents had two other children who died of diphtheria at a young age); my parents expressed their love for me by constant supervision and demands to eat and drink sufficiently. They also pressured me constantly and demanded that I spend my days and nights on study and worship.

Now, in my new status as an engaged person, the pressures of the cheder were somewhat eased so my general wellbeing improved. I felt satisfied that there was another soul whose fate was linked to mine and that I was no longer alone in this world. I began loving my bride without knowing her. I saw her as a symbol of my success, a person capable of extracting me from the narrow space of my room and my parents' dark home. In the letters I wrote my fiancée I conveyed great love, not thunderously or loudly, but modestly by way of hinting, because the bonds of the cheder still arrested my senses. Shame constrained my expression of love, despite my “maturity” and the feelings that grew stronger within me.

On Purim, my fiancée sent my parents a basket of her creations. She sent various embroidery, wool and silk. I felt extraordinarily happy when she sent her photograph. Often I came home from cheder and studied the photo, secretly so nobody could see me,

My parents and my in-laws felt guilty about bonding two souls in such a strong bond without my fiancée and I being acquainted. So, to atone for their sin, during Sukkot 5634 I was taken to my father-in-law's home “so the children can get to know each other.”

My father-in-law sent a chariot carried by strong horses, in which I [rode along with] the boy tasked with accompanying and serving me, as was tradition, and we traveled to Orekhovets.

[Column 43]

I celebrated the last days of Sukkot in Orekhovets and saw my fiancée sitting at the table at each meal, although I was not brave enough to approach and speak to her. Because the engagement was done in my birth town by handshake and the contract was yet to be written, my father immediately travelled to Orekhovets following the holiday. The contract was written and signed properly with witnesses. After the dish was broken, according to Jewish custom, we returned home. Before my father and I left, he requested that I approach my fiancée and speak to her, as he saw I was very shy. Father gave me some dates and asked me to hand them to my fiancée. As we parted, I said goodbye to my fiancée and told her “live well” and she replied in a whisper, “safe travels.” I kissed my in-laws goodbye.

H.

I was freed from the burden of the cheder as a mature groom. I studied with my (maternal) great-grandfather for some years so I would not be idle all day. I also helped him as he dictated his book Begged Lilvosh [clothes to wear], which was a criticism of Rabbi Feivel of Baradshin [? באראדשין ] and a defense of the author of Le'vushei Srad [formal wear], who was a relative of Rabbi Mordechai's. Rabbi Mordechai was a wonderful teacher, pedagogically talented, who despised convoluted interpretations and only desired to find the simple truth. He was a guide to many but writing was difficult for him, as it is for all scholars. One of his pupils was his right-hand man when he wrote. My father-in-law had also been a pupil of Rabbi Mordechai and his favorite scribe.

I.

During those days, I experienced a difficult and saddening event that was typical of the relations and living conditions those days in Galician towns. One of my relatives in my hometown loaned money with interest to local peasants. Because he never learned how to write in German, he asked me many times to write him loan terms and sign for those who did not know how to sign their own names. My relative likely did not

[Column 44]

treat his clients honestly so one of them initiated criminal proceedings against my relative. The judge investigating at the district court of Borszczów was an infamous anti-Semite, and his custom was to arrest every accused Jew or Jewish witness during proceedings. I was summoned as a witness, as the one who witnessed and signed the loan terms. Therefore, I feared that the judge would place me in jail, which worried me and my relatives and caused many sleepless nights. My relatives and I deliberated and decided that I would travel to my father-in-law, who now lived in Kurniki? near Husiatyn by the Russian border. I was to wait in Kurniki until the storm passed, thus defying the judge who could no longer harm me as I was out of his jurisdiction and [he was forced] to send the documents for my testimony to Husiatyn.

And so I traveled to Kurniki and stayed with my in-laws for about three weeks, and after I testified in front of the judge in Husiatyn, I returned home without issue. While I stayed with my in-laws, I became more closely acquainted with my fiancée. We began conversing—of course not in view of others—and spent time in the fields where we picked flowers, planted flowers and watered them. Those days were among the happiest in my life and I will never forget them.

J.

By 5638 I was no longer an only child, as my patents had another child, my brother David. The boy was born weak and thin and could not be circumcised on his eighth day. My great-grandfather visited David every morning on his way to the synagogue, to see if David could be circumcised. A few weeks later, he decided David should be circumcised and wanted to perform the circumcision himself. My parents objected and said that his hands “were shaking in old age.” My great-grandfather was offended and angrily replied that he was “a bigger expert than the younger men.” My parents paid no mind to my great-grandfather and brought a mohel from Borszczów. The operation was a success and the child healed within a few days. However, at 18 months old, David became ill with whooping cough, to the point that it was predicted that he could not be resuscitated. All the medications he took were useless until Dr. Hirschhorn gave David a few drops of opium. The baby drank and fell into a deep sleep. Sleep strengthened the child and eased the cough until the boy slowly healed.

[Column 45]

K.

I am not ashamed to admit that I awaited my wedding day with baited breath, not because I so desired to unite with my wife but because I wanted to be freed of my parents' home and their constant supervision. Their parenting became a burden to me; whereas in other nations a young man is considered mature at age 24, a Jewish boy, a cheder student of 19, feels like a man in every respect and requires no supervision, rather the opposite. The discipline of his parents' home always burdens him and he desires to leave their purview. My parents also relied on the age prescribed by the sages, “eighteen for the canopy.” Thus, they decided, and both sides agreed, to hold the wedding in Cheshvan 5642. The wedding was celebrated gloriously; many good friends and family members came of our wedding. The dancing of the maidens, the bride uncovering her hair, the canopy, and reception were all fulfilled, as is tradition. After the meal, the crowd danced with the tired bride while I went to sleep on the floor - because there were no beds – in the midst of invitees who did not wish to dance. In the morning I was told that the dancers asked for me and whispered to one another that “the groom is lost.” However, my disappearance did not create a sensation. As morning arrived, the invitees traveled to their destinations. My parents stayed as guests of my in-laws until after Shabbat when they said goodbye. After my parents returned home, my world was comprised of my room and my wife. I was happy in my independence and ceased depending upon the opinions of others. I most enjoyed the separation from the constant study and all that it entailed. Because my wife was a villager and a lover of nature, and I too loved nature very much, I happily drew water from that well of freedom and spent my time strolling in fields with my wife. She picked flowers and herbs, and I demonstrated my knowledge of botany (which I gathered from secular books I had read in cheder) and told her the names of flowers and herbs. Her eyes conveyed astonishment as if to say, “How do you know all that?” I boasted that I, a “city boy,” knew more than villagers about flora.

L.

The honeymoon passed in silence and serenity until the burden of compelled military enlistment began in 5641. My parents, my in-laws, my wife, and I were very much saddened by [the prospect of service in the] military for four years, until 5644. Every spring, I had to leave my home and wife to spend some time in Jezierzany and in the nearby Borszczów, spending night and day to torment my body and soul in order to be saved [escape] from the sword hanging over my head. I escaped the military only after much difficulty and financial loss. That was my first worry in maintaining the family when I began protecting its existence. Thank God, I battled that problem and defeated it. Truthfully, my education at the cheder and my weak body were unfit for learning military maneuvers, going out to battle, and attacking in formation.

M.[15]

My father-in-law supported me for four years. During that time, I assisted my father-in-law with his leasing business and agricultural work. I learned the agricultural business in full detail and trained as much as possible.

After my second daughter, Rachel (sister of Amalia) was born, I decided to invest in agriculture –which I so loved—and lease land of my own for income.

…The first year of our lease, 1889, was a drought year. Rain did not fall all summer until the end of August and the annual yield was saddening. The second year, however, was an abundant year. Not only did we recover our losses, we earned a small sum and had enough to live on. Therefore, in the spring of the second year, (April 8, 1890) my family and I relocated to the village where we leased, Stetseva where I resided for nine years.

N.

Thus, I lived peacefully on my land. I plowed the fields, planted seeds, harvested,

[Column 47]

and my work was blessed. The years were ordinary, neither dry nor rainy.

When I moved to Stetseva, I discarded the long clothes that Polish Jews usually wear and instead dawned short, European clothes. Yet I was honest with God, lived a religious life, and fulfilled the customs with which I was raised and I could not uproot from my heart. On Shabbat and holy days, I prayed at my neighbor's house where he hosted a minyan. I served as the leading reader of the Torah and at times I led prayers. There, my knowledge of the hymns of the synagogue and my strong voice, which had turned from soprano to tenor, were useful. I remembered the tunes I had heard in my youth from the cantors and their assistants and my listeners praised me. I also enjoyed the holy days and the family life which they entitled.

My serenity did not last long and dark clouds gathered in the skies of my success. My wife became ill and all remedies proposed by the doctors could not cure her. At that time, she gave birth to a boy who died when he teethed, which devastated her, so she had to return to her father's home. When I learned that her heart defect [the sadness in her heart?] was healing, and that she missed her daughters and me very much, I brought her back to my home. A year after she returned, she bore me a son on Tamuz 1 5657. I called him Shimon Raphael, for God had heard my prayers and healed my wife.

O.

Shimon Raphael was born with dark skin and was very thin. His mother wanted to breastfeed him but I objected and tasked his breastfeeding to a Rusyn-Ukrainian wet-nurse whom I brought from my birth-town area. The boy developed nicely, his skin whitened and he gained weight and beauty. Yet when he began teething at eight months old, he became ill with the same disease, polio, which had killed his brother. We had already given up on him; one Friday when my wife and I saw that the child was dying, his life candle was flickering, and no hope remained to heal him, we left his side. Crying in despair, we went to stay with a friend because we could not witness the death of the child. Only the wet-nurse and a close neighbor stayed in the house to watch over the child's crib. That night was awful, filled with crying and mourning. Yet God probably showed his mercy and did not wish to rob us of our remaining hope. As the next day dawned,

[Column 48]

on Shabbat day, a messenger came from our house and notified us that the boy was still alive and was showing signs of healing. We quickly returned home and saw that God preformed a great miracle on our son, who returned to life from the edge of the abyss. The boy was ill for a long while following that, but he slowly but surely returned to his former health, even if his facial features were thinned and his former fat never returned.

P.

My father was sick with cancer so I hurried to Jezierzany to the side of his deathbed. My father was lucid to the very last moment. He did not fear death, quite the opposite: he desired death to end his suffering. A few hours before his death, he told me, “I am content that my end is coming.” My father was 59 years old when he died. On his gravestone in the Jezierzany cemetery I ordered the description “Walked an honest path, without convolutedness or stubbornness, was not greedy, did not ask for accolades.” I did not exaggerate my father's qualities by the traits that I listed; honesty, humility, and despising greed were truly a part of him. I cried bitterly for the loss of my father; I felt that I had lost a man who loved me and cared for me more that he cared for himself. I felt orphaned and for the first time in my life felt the gravity and depth of that word.

Q.

I did not earn well from my estate, Glembaka, which I had purchased with savings from a life of hard work, despite having worked it diligently with the sweat of my brow. Yet I was very fond of that estate for I designated it as a site for rest after retirement, and because my whole life I desired land ownership which frees its owner, and a man can do with his land what he wills. Now that I have acquired that land, how can I not like it? Therefore, I did not consider my profits or the interest resulting from my investment in the land, and I focused my time on improving the estate and beautifying it. I spent all my summers there. Every time I built a building or planted a tree, I enjoyed it immensely, for the tree is my tree and the building my building, and no man can remove me from my land. I planted vines and fruit trees, constructed homes for the servants, fenced

[Column 49]

my yard and a installed a gate, dug drains in the fields to avoid flooding and swamps left by the rain. In short, I enjoyed my land until the great European war came in August 1914 and my tranquility was disrupted.

One Saturday night, I was forced to escape after Cossacks stormed the neighboring town of Chortkov. My cousin Esther Rivkah, our sons, and I first escaped to Staniloy? and later, as the enemy approached the gates of that town as well, to Vienna. My escape and all the wandering it entailed requires its own book. Yet

[Column 50]

at this moment, as the war rages, and my only son[16], a 19 year old boy, is forced to serve in the military and the danger of battle looms over his shoulder, I do not have sufficient rest to describe all the adventures of the Viennese exile that I experienced. If God will restore peace, then I will take up the task of describing my escape in detail. On that occasion I will also tell of the results of the destruction of my home and possessions in Glembaka, which I dubbed “the destruction of the Second Temple”.

|

|

| Yehuda Cohen and His Family |

Endnotes:

Note: Many definitions are taken from Wikipedia.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ozeryany, Ukraine

Ozeryany, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Jun 2019 by LA