|

|

|

[Page 45]

Translated by Ida Selavan–Schwarcz

The ‘Hatikva’, founded by Schmaryahu Imber, the teacher, was the only Jewish society in Jezierna and lasted 40 years – until the outbreak of the Second World War. It had its own little house. People came there to read newspapers, to hear readings, hold discussions, and here, too, was the only Jewish library in town, with books in various languages, not only Yiddish.

For the 25th anniversary of the Jewish National Fund, a ‘Tea–Event’ was prepared by the JNF committee in the Hatikva house, of course. Yitzchak Charap gave a review of the story of the JNF. The program included songs, an orchestra and the main point…the event raised a nice income for the JNF. (Correspondence from S.I. in Haynt, dated 4.1.27

The local community did not have a great role in town affairs. It concerned itself with communal functions, the religious institutions of generations: rabbi, ritual slaughterers, ritual bath, cemetery.

There was also an amateur theatrical circle, which presented a play from time to time, and the receipts went toward ‘a worthwhile goal’. On the twentieth of Tammuz 1934, the anniversary of Theodore Herzl's death, there was a memorial meeting in the morning, a ‘mourning ceremony’ (at which Professor Sassower spoke) and in the evening the drama group performed Gordin's ‘The Unknown’, under the direction of Mrs. Fancia Blaustein. A great success morally, it also brought in a nice revenue as well (‘for societal purposes’, Chwila, Lemberg, 2.8.1924).

Jezierna had only one party, the Zionists – with its various shadings; at least so it appears from the newspaper correspondence from Jezierna. As far back as 1900 a Zionist organization existed there.[1] In 1905 the Jezierna Zionist Organization founded a club ‘Dorshei Zion’, under the chairmanship of Schmaryahu Imber, which joined the Lvov district. The well–known Zionist communal worker Ephraim Wasicz also came from Jezierna.[2]

At the time of the elections to the Zionist Congress in 1933, Jezierna voted for the various lists as follows:

| World General Zionist Organization | 17 |

| Mizrahi and Tzeirei Mizrahi | 17 |

| Labor Eretz Yisrael (United Zionist Socialist Party, Hechalutz, Hashomer Hatzair, Gordonia) | 63 |

| Zionist Revisionist (Jabotinskyites) | 89 |

| Zionist Workers Party ‘Hitachdut’ (opponents of ‘Ichud’ group of Dr. Schwartz) | 12 |

| Total | 275 |

In July 1939, the number of votes was considerably less (List 1 = 16, 2 = 4) according to ‘Haynt’ of 26.7.39. It is possible that this was a printing error, which we cannot correct at present, unless there are Jezierners who remember those times.

In 1934 the local Zionists were busy collecting funds for the pioneers of the General Zionist organization who had settled in Kfar Ussishkin. Participating in this campaign were the head of the community, W. Klinger, Dr. Tenenbaum's wife, R. Shtrick and others.

The local General Zionist pioneers founded a brigade which tried to find work on a farm under the supervision of the most important community leaders in Jezierna, firstly from Mr. Klinger, who was also the manager of the farm, and Mr. Falk.

Before the war Jezierna had a Jewish mayor. In order to prevent this, after the war a Polish government commissioner was appointed, and along with him there was a council, shared according to an understanding among the three ethnic groups in Jezierna: Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians. In 1931 the Jews resigned from the office of mayor and took on the office of vice–mayor. They assumed that an elected mayor would be more interested in the welfare of the town than an appointed official. In the end, the Jews, that is the twelve Jewish representatives out of 48, resigned from the office of vice–mayor for the sake of peace, in favor of the Ukrainians.

But when there was an opening for a treasurer in the municipality, with a salary of 35 zloty a month (!) and the Jews requested that a Jew receive the position, the Poles united with Ukrainians and gave the job to a non–Jew. There was not one Jew among the personnel in the municipality, although the Jews paid the largest proportion of municipal taxes.

The Jews also gave up three classrooms in the former Baron Hirsch school to the government public school, for no remuneration. On the other hand, the Polish Community Center, which gave up a room for that purpose, was paid.

“That is a good lesson for the ‘Moshkes’ (assimilationists)” – with these words M.M. completed his correspondence, published in the Lemberg ‘Chwila’ on 16.3.1932.

Footnotes

Translated by Ida Selavan–Schwarcz

When the first Baron Hirsch schools were founded in Galicia in Bukovina, in the last decades of the 19th century, they were opposed by almost all the sectors of the Jewish population. The wealthy, so–called intelligentsia, insofar as they were assimilated, had no use in particular for a Jewish school; on the contrary, knowledge, culture, were considered 'international' and they were ready to assimilate according to language to the Poles who ruled our region, or to the Germans, who were the crème de la crème and boasted of their capital Vienna, the Kaiser's court, etc.

The Jewish masses were mostly very religious and saw no need to leave the heder, yeshiva or bais midrash [study hall of the synagogue]. They considered the Baron Hirsch School as unfortunately leading to conversion. Of course they did everything in their power to prevent the schools from opening. And when they were nevertheless established, they did not send their children there. On the other hand, the children hated attending the general 'public' school where they had to sit bareheaded and look at the crucifix on the wall. The Baron Hirsch School had difficulties, struggling in Jezierna and other towns (Sasow, Zborow, Zalocse in the nearby area) until it succeeded in making a name for itself and was properly appreciated by the Jews, since it was recognized by the authorities from its founding.

Today, from the vantage point of over half a century, there is no Jewish historian or person involved in cultural activity who does not appreciate the great achievements of the school in all aspects of life. The school not only taught the children according to a set curriculum, it also nurtured and drew the Jewish child nearer to what was then called European culture. It also taught Yiddishkayt [Judaism] in the new nationalistic mode. It showed Jewish society new realms of educational activity such as gymnastics, sport, geography, agriculture and gardening. It also encouraged poor youths, after finishing school, to learn productive trades, so as not to be dependent on the poverty–stricken Jewish society.

The school opened its doors in the school year 1895–1896 with one teacher and 100 pupils who attended irregularly. By the second year, 1896–1897, it had its own building, which cost a not inconsiderable sum for those days: 21,759 Kronen and 65 Groshen.

From the frequency of attendance of the pupils we can see that there were ups and downs. Some pupils left and did not complete their schooling; others came so infrequently that were not classified; some were kept back in the same class for another year, the reasons being the parents' indifference to the school in general, pupils' illness, low social status, etc.

It seems for example that from November 1, 1900 to July 1, 1901, classes began two months late because of an epidemic of pox, so that there were 1,958 days lost; that is, almost 19 late days for each pupil during eight months of study. Also during this period 1,450 days were lost due to illness, that is, 14 days per pupil. Really, a difficult situation

As far as the social status (employment) of the parents of the pupils, they may be divided into the following groups:

| 1. | Officials, teachers, lawyers, doctors | 1 |

| 2. | Manufacturers and independent artisans | 4 |

| 3. | Independent merchants | 36 |

| 4. | Clerks, bookkeepers, workers in factories | 5 |

| 5. | Journeymen | 0 |

| 6. | Day laborers (paid on a daily basis) | 23 |

| 7. | Occasionally employed | 27 |

| 8. | Received charity | 0 | Total | 96 |

A really dreadful picture. More than half of the parents belonged to the lowest social classes (numbers 6 and 7 equal 50% of the 96), had no stable employment, and were even occasionally unemployed (more than < of all parents, 27.5%!) Only five parents belonged to the highest group (numbers 1 and 2) a bit more than 5%. The third group were called independent merchants, but they only had limited merchandise in hole–in–the–wall shops. It is hard to believe that they all actually made a living! This situation, as well as the state of the independent artisans, indicates indirectly the fact that there were no journeymen in the entire town, and only four workers in category four [table shows five]. In other words, the independent artisans (there were no real manufacturers in town) worked by themselves, all alone!

The table shows who sent their children to the Baron Hirsch School. It also shows the economic situation of the Jews in the whole town, since [there were] 106 children in the school, (the table shows only 95 [96], because others who did not attend, were not classified, therefore the school had no data on them, but they certainly did not belong to the upper classes! There was no one in charge of these children, thus they were neglected.), probably out of all the school–aged Jewish children in the shtetl, which numbered about 1195 souls, at that time. Some children did not go to this school but were privately tutored, or went to other schools and belonged to the wealthy families in town. It is certain that the children of the most pious, the religious functionaries, did not attend this school at all; this is true as well for the poorest children, who had to help their parents earn a living, or who went house to house begging. These categories of parents were not represented in the school at all. Thus, the table more or less reflects the economic situation of all the Jews in town.

Another sad note. Among the 95 [96] children there were seven without a father, two without a mother, and one without either parent. There was one child whose father was not concerned at all (he had abandoned the family!) Also a tragic situation – more than 10% were orphans.

This is also reflected in the distribution of material goods to the school–children that year: new winter coats and hats –30 (almost 1/3); shirts –80; summer outfits –56; used winter coats, repaired –48; altogether seventy–eight coats (for 96 children!); underwear –40; shoes –73; (19 new pairs, 54 used, repaired); handkerchiefs –120 (!!) About this last item it should be clarified: giving a cloth for the nose to such children – this was part of their education, to teach proper behavior (not to blow one's nose with one's fingers, as was customary).

The school concerned itself with the pupils' outward appearance, cleanliness, just as it concerned itself, according to the instructions of the trustees of the Baron Hirsch School–to protect the child from negative influences at home and in the street. Therefore, the children were kept in after classes; they were involved in sport, games in the playground and general discussions. There were reading groups, story hours, and even vacation activities when the school was officially closed. There were also trips outside of town, etc.

In the same way the child was protected from foul language. They wanted to teach the child a beautiful language – Polish, and the children were required to speak Polish only, even during recess and in the street.

The children were also fed. During the year 1900 –1901, 70 children received supplementary meals. They received meals during 79 learning–days (79 lunches). This also shows the low economic situation of the parents.

Besides that, 410 books, 100 sets of school supplies, 228 notebooks were provided for the 100 children in the school during that year.

That means that the school not only taught Torah and good habits, but also helped the child, and thus the entire family, with clothing and school supplies, so that the parents would not have to spend money on these items. In addition, it fed the child because he came to school.hungry.

The school's expenses differed from year to year, depending on the number of pupils, the teachers' salaries, which increased according to the number of working–years, etc.

Just as an example, we shall display some numbers so that one can get an idea of how the school budgeted its expenses.

The normal budget of the school was 2,500 –3,000 Kronen per year. Thus the cost for one pupil (in 1900–1901) was 56.61 Kronen.

For clothing, food, and so on, the total was 800 –900 Kronen, for the year; thus the cost for each pupil in that year was 15–16 Kronen. In those days this was a great deal of money.

There were a great many repeaters (33 as opposed to 73 non–repeaters) for irregular attendance, not preparing lessons, etc. The grade results are:

| Class | Very Good |

Good | Pass | Not Pass |

Total |

| 1 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 6 | |

| 2 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 26 (27) |

| 3 | 2 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 26 (29) |

| 4 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 17 (19) |

The remaining 8 students were completely unclassified.

Obviously this is not an overly satisfactory picture. The fact that so many pupils were left back to repeat a year was not due to the stupidity of the pupils, but because they were often absent due to social reasons.

The fact that they did not prepare their lessons was due to the same factors. The children were helping out at home or in the business, or working in a shop, etc.

In addition, the children were also attending classes in a heder or in a bais midrash [Jewish study hall], which their parents considered more important than the ‘shkola’. The child had neither time nor energy to prepare lessons for the ‘shkola’. In general, the attitude towards the ‘shkola’ was negative.

The school was visited annually by representatives of the Austrian school authorities and by the trustees of the Foundation. The results of the visitations were good, as manifest in the reports. This is evidenced in the fact that the school was officially recognized in 1902–1903.

The school was for boys only. But the Foundation was also concerned about education for girls. It opened evening classes (in one year there were 30 girls), but after a few years (in the school–year 1897–1898) the courses were closed because “the pupils did not attend regularly.”

After completing school, some boys whose parents agreed, were apprenticed to artisans. The school management paid for this. The number of pupils who studied a trade was small, three or four a year. There was seldom a larger number. The pupils studied mainly in Jezierna, tailoring, shoe–making, carpentry, turning [working with a lathe], tin–smithery, etc. Some pupils were sent to Zalocse to study trades which were not available in Jezierna. This is stressed in the report of 1898–1899, that seven pupils who had completed the school in Jezierna, were in their second year of studying a trade in Zalocse, paid for by the school.

What the Pupils Learned in the School

Let us consider the subjects and the hours devoted to them, which remained unchanged during the course of all the years of the school's existence:

Religion (except Hebrew), Hebrew, Polish language instruction, reading and writing, German language, arithmetic, geometry, drawing, singing, gymnastics.

The number of hours per week: in first grade – 21; second grade – 23; third grade – 24 and fourth grade – 24. In addition they also studied Ruthenian for two hours a week.

The school, like the other schools of the Baron Hirsch Foundation, ceased functioning with the outbreak of World War One. After the war the foundations funds were lost. Other communal institutions took over the buildings. Some buildings were rented to private individuals and with the passage of time, the fact that these buildings had housed the Baron Hirsch School was forgotten.

In the report of 1900–1901 there are interesting details about the building which the Baron Hirsch Foundation had built for its school. There were five rooms, three for general studies, one for the staff (and for meetings) and one for the lunches which many pupils received there.

In addition there was a four room (!) residence for the school director.

Next to the school was a large courtyard (147.28 square meters) for gymnastic exercises and a playground for the children; a school–garden (350 square meters) where the pupils, under the supervision of the teachers, learned how to work the soil (gardening).

Who Were the Teachers

The first (and only) teacher and also principal, was Akiva Nagelberg, who had graduated from a seminary and had a teaching certificate. He began working on December 31, 1893. The second teacher was Shmaryahu Imber, from October 1, 1896. He taught Hebrew and was an assistant teacher with a monthly salary of 80 Kronen. From November 15, 1897, Anna Osterzetzer worked there. She had graduated from a seminary but was an intern. (She had not yet received her teaching certificate.)

Nagelberg left at the close of the school year 1896–1897 and his place was taken by Yakov Blaustein, who also became the principal. He had graduated from a seminary and had a teaching certificate (license). His annual salary in 1900 was 1,980 Kronen, not a small amount for that time.

There was a provisional assistant teacher for only one year, 1898–1899, who had not yet graduated from a seminary, Yehuda Prezes. Before that he had taught in the Baron Hirsch School in Kolomaya.

Ab Steinbach, seminary graduate, was a provisional teacher from October 1, 1896, receiving a yearly sum of 1,080 Kronen.

Tsippa Baruch, a seminary graduate, worked from November 15, 1900. She taught part time and received 60 Kronen a month. (Later she taught full time)

These four teachers – three for “profane (general) knowledge” subjects, as named in the reports of the Baron Hirsch Schools, and one for Hebrew and religion – worked in Jezierna until the outbreak of World War One in 1914.

As for the ages of the four teachers; in 1900–1901 one was 25 years old; another was 25–30; another was 30–35; and one was 40–50.

Two were ”single” and two were “legally married”. In effect, one teacher worked the first year, two the fourth to fifth year and one the eighth to ninth year.

The outstanding teacher was certainly Shmaryahu Imber, who taught there from 1896–7 until the outbreak of the war. In 1915 he and his family escaped to Vienna, but after the war he came back to Galicia, settled in Cracow, but would visit Jezierna from time to time. He was so connected to the place!

Shmaryahu Imber was born in Zloczow in 1868. He was a younger brother of Naftali Herz Imber (born 1857), the lyricist of ‘Hatikva’. His son was Shmuel Yaakov, a noted poet in Yiddish and Polish, who wrote a doctoral dissertation in English on Oscar Wilde. [Translator's note: The dissertation was written in Polish] In the last years before the outbreak of World War Two, when antisemitism in Poland was growing, Imber (the son) published a periodical in elegant Polish, oko w oko (eye to eye) in which he wrote ironically and sarcastically about those Polish writers who accepted Hitler's teaching.

Some biographies (for example, Lexicon of the New Yiddish Literature, Volume 1, New York: 1936) mention that he was born in Jezierna, but he was actually a child of seven or eight when his family settled in Jezierna, where he spent his childhood–school years.

Shmaryahu Imber was a devoted Zionist who wrote for Hebrew and Yiddish periodicals: “Yiddishn Vokhnblat”; “The Carmel”; “Hamitspeh”; “Hatsefirah”. He was involved in cultural and communal affairs. In Jezierna he founded a Zionist society with discussions and debates, was a delegate to the World Zionist Congress a number of times. From 1887 he taught Hebrew in a school [Safa Berura] supported by a cultural society in Zloczow. In 1888 he founded, in Zloczow, a Zionist society, “Degel Yeshurun” one of the first in Galicia.

In Zloczow in 1901 he published the Hebrew poems of his brother, Naftali Herz.

In 1887 he married Bella Miriam, the daughter of Yaakov Freud. She died in Cracow in 1933 and he left Poland that year and settled in Jerusalem. He re–married to Sarah, daughter of David Efrat, sister of poet Y. Efrat.

In Jezierna, Shmaryahu Imber founded the Zionist society “Hatikva”. In 1927, for the 30th anniversary of the society, he made a special trip to Jezierna from Cracow, in order to participate in the celebration.

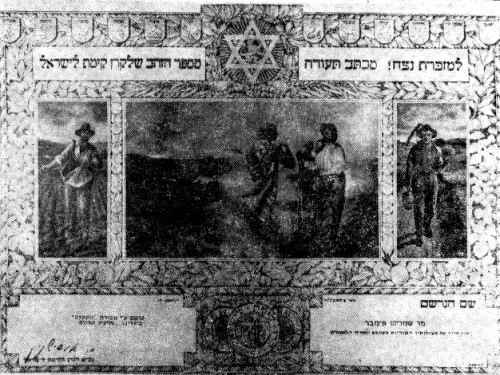

In 1939 his friends in Jezierna had him inscribed in the Golden Book [of the Jewish National Fund].

In the Land [Palestine], he published articles in ‘Davar’, ‘Haboker’ and ran a free–loan fund for new immigrants from Galicia.

He published a volume of his brother's poems with a long introduction about the life of Naftali Herz Imber.

(Note: All the Poems of Naftali Hertz Imber, biography by Shmaryahu Imber, introduction by Dov Sadan. Published by M. Neuman, Tel Aviv: 1950)

Naturally such a teacher, (even though he was not “qualified”, as emphasized in official reports, and therefore received less salary), did not teach the rules of Hebrew grammar in a dry manner. He was the educator of a generation of children and his influence was felt in the entire town until his tragic end.

Note: Biographical Notes:

On July 31, 1902, Shmaryahu Imber published an article in the ‘Lemberger Togblat’ on ‘Hasidim and Melamdim’, [Pious Ones and Teachers of Religion] where he analyzed these two words, what they meant to we Jews in the past and what they meant at present. Once upon a time the word “Hasid” was “a title in its own right”. It had an important meaning, and needed no additional explanation, such as rabbi, etc. At present, “whoever wants to –– considers himself a Hasid –What? – Torah? What? – scholarship? What? – piety? A trip to the Rebbe and you become a holy man!”

“The word “Melamed” has no better fate. It sickens one to see who our teachers are now. Simple ignoramuses, and we let such Jews educate our children. The rabbis, too, who should be concerned with the education of children, do not bother themselves with it. They are only concerned with ritual slaughter, kashrut, and what is forbidden⁄”

The author asserts that there should be a seminary opened for melamdim [Jewish studies teachers] and that the Eighth Zionist Congress, which was due to assemble then, should discuss this problem also.

In the article the author characterizes the conditions of the heders in general and in Jezierna in particular. The rabbis and melamdim have remained unchanged, not altering their approach, their teaching methods, etc. They have not moved forward with the times. These arguments were made by another writer thirty years later, as we shall see.

This article by Shmaryahu Imber expresses the position of a maskil [enlightened person] at that time, as well as the point of view of a teacher in a modern Jewish school, a Baron Hirsch Foundation school.

|

|

|

|

|

Krakow, month of Nissan 1924

My Distinguished Friends ! This week I returned from Vienna and found your postcard, and I was very happy to see that the memory of me has not yet vanished from your midst, and that you continue the work of revival, the revival of our people, our homeland, and our language, for which I have dedicated almost all my life. So please go ahead, my dear sisters and brothers, with your strength and your will, and together with all the faithful sons help build our homeland. In the last few weeks I have received many packages of ‘Ha'aretz’[Israeli newspaper] that for some reasons were delayed along the way, but I have not read them yet. I am sending to you, with Mr. Gottfried, 20 new issues as well as old ones, and I am truly bestowing on you the good fruits of ‘Ha'aretz’. Together with my greetings, also receive my thanks. Be sure that I too have not forgotten and will not forget you. It is indeed a wonder to me that to this day you have not yet implemented your decision of last year regarding the Golden Book ?? !!

With the joy of the holiday and the blessing of revival, |

Translated by Pamela Russ

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the rabbi in Jezierna was Rabbi Asher Zelig Aptowiczer. We find his name among those rabbis who signed the protest (a public protest) of the rabbis, totalling 100 persons, who had assembled in Sadowa Wisznia in the year 1907, at end of August – under the chairmanship of Harav Hagaon [The Gifted Rabbi] Sholom Mordechai Hakohen Schwadron, Chief Justice of the Beis Din [Rabbinic Court] of Berezhany, in order to protest against the rabbis who permitted riding the electric tramways on the Sabbath – “in the carriage that runs on mechanical power (steel tracks and the tramway) ” – as it was expressed in the protest document. We are leaving out the original words and format. See the [newspaper] “Kol Machzikei Hadas” [Voice of Supporters of the Religion] that was published in Lemberg in Hebrew, on September 8, 1907.

The Rabbi was the son–in–law of Rabbi Chaim Leibish, head of the Rabbinic Court of Lopatyn, and was the son of Rabbi Yosef, head of the Rabbinic Court of Schterwicz [Szczurowice].[1]

Besides him, in that same period, there was Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Manson, born in 1843, a grandson of Yisroel Ruzhiner, of blessed memory, and a son–in–law of Rabbi Michel of Azipoli. Reb Levi Yitzchak was the author of a book on the Torah, “Becha Yevoreich Yisroel” [Through You Israel Will Be Blessed]. “He was a man great in Torah,” said the writer of “Sefer Oholei Shem” [Book on the Tents of Shem]. An additional praiser adds: “He distributed a lot of money to support the yeshivas [schools for religious studies] in the above mentioned cities.”[2]

And in truth, in the newspaper “Kol Machzikei Hadas” of December 12, 1905, we found an announcement that Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Manson donated 10 Kronor (Crowns) as Chanuka–gelt [Festival of Lights – gift of money] to the yeshiva in Berezhany, the first modern yeshiva in eastern Galicia.

It seems odd, such a small town and at the same time – for part of the time – two rabbis.

As can be seen from the title page of “Sefer Becha Yevorach Yisroel,”, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Manson was a grandson of The Ruzhiner (Yisroel Friedman), who in the year 1840 moved from Russia to Austria (Galicia), then settled in Sadigora (Bukovina). He was the founder of the dynasties of rabbis that branched out into separate rabbinic courts, such as Vizhnitz, Chortkow, Husiatyn, to mention only the more famous ones.

Manson was a true grandson. In my younger years – I remember – they spoke dismissively about “ordinary” grandchildren, because his mother Gitel was the Ruzhiner's daughter; (his father Yosef was an ordinary pious Jew who knew how to study Jewish texts).

The book consists of 61 pages in two columns – and is a commentary on the Torah. That is just the first section; the second “Zahav Peninim” [“Golden Pearls”], if I am not mistaken – does not appear in the printing.

In the introduction to the book the writer excuses himself, and asks that if the reader finds any printing errors, he is not to blame for them and that “G–d should protect me and give me long days so that I will have the merit to publish the second part.”

The book was compiled by “the young man Mordechai Leiter,” a disciple of the rabbi, who actually lived in the rabbi's house – with the support of the notes that the rabbi wrote in the margins of the books about individual passages in the Torah.

In the epilogue, the writer explains, for the second time, that what he put in the book he had noted for himself while teaching. It is likely that he used the explanatory notes for the lectures that he delivered in the synagogue. He apologizes for “mistaken or incorrect ideas and also for other discussions that are already included in a book.” He asks to be forgiven for this, he did not do this intentionally – but only because “my memory is failing or that I did not see that particular article.” That means – there is no plagiarism.

In a later explanation, he says that during his whole life he suffered from “the pain of raising children” – it would be interesting to find out from the Jezierna Jews who still remember this time, what happened to the rabbi's son.

Did he leave to follow unapproved modern ways?! And aside from that, the rabbi was always sick. These are the external reasons that disturbed the writer during his work. To his critics, perhaps, he responded as follows: “It's easier to be a critic than to be an investigator.” A classic phrase showing that Rabbi Manson was a clever Jew, not in the least bit an old–fashioned fanatic (“khnyok”).

In the epilogue, the writer concludes very nicely: “It is forbidden to enjoy anything in this world without reciting a blessing, so therefore I will say the blessing appropriate to this particular item: Thank you God, for teaching me Your laws.”

Such a Rabbi was certainly the glory of the town!

There are two additional pages to the book with names of the “subscribers,” meaning those Jews who paid for the book even before it was sent to print, and that made it generally possible to publish the book. In those times, this was an accepted means used by writers who did not have their own funds to put out a book and did not have a publisher who would do this at his own expense.

Among the subscribers there are 44 Jezierna families. Understandably, these are the prominent ones of the city, who were not only able to study it, but could also permit themselves to acquire the book. The amount that they paid – is not disclosed. Everyone paid “according to his means.” Among these names we find: The Holy Rabbi, our Teacher Mishal; the son of the holy Admor [master, teacher and rabbi], may he have long life; the large court of the Holy Rabbi, may he have long life; Misters Sholom Charap, Avraham Charap, Nuchem Charap, Zalman Winkler, etc.; names of families that played a role in the lives of the Jews of Jezierna. Besides these subscribers, we find names of people from other places, such as Azipoli (The Gifted Rabbi, our Teacher Yishaje Landau, Chief Justice), Amiszynce, Bodzanow, Brody, Tarnopol, Koprzywnica, Podhajce, and so on.

Footnotes

|

|

|

|

Personalities:

Wasicz, Efraim (Fishel), born in Jezierna in the year 1879, completed middle–school in Zloczow and then university in Lemberg as a lawyer. He was one of the founders of the “Tagblatt.” He actively participated in the Zionist movement (Zeirei Zion) and attended all the Zionist congresses. After the pogrom in Lemberg in 1918, he founded a Jewish military. After that he escaped to Vienna and later he settled in Israel (1919) and worked as a lawyer first in Haifa and then later in Jerusalem. He died in Jerusalem, on the 17th of Shevat, 5705 (1945).(from Pinkus [record book] of Galicia 1945, p.225/6)

Fuchs, Avraham Moshe, born 1890 in Jezierna. As a child from a poor little shtetl and closely tied to the village, he absorbed all the healthy good–naturedness and simplicity of the hard–working Jews with their joys and pains, and had a silent love of nature. At age 16, he came to Lemberg and worked at many types of jobs. Here he became interested in the Workers Movement and with the activities of the Jewish Socialist Democratic Party, (the Galician “Bund”). Later, he came to Tarnopol, and here he became popular. In 1911, he made his debut with sketches and stories in the “Sanok People's Friend,” and then also wrote for the “Tagblatt” and “Yiddishe Arbeiter” [Jewish Workers] in Lemberg. In 1912, he published a collection of stories titled “Einzame” [Loners]. That same year he left for America then returned to Europe in 1914 and settled in Vienna. With time, he became a contributor to a whole array of daily newspapers, journals, and literary collections of narratives, and grew in his belle–lettres skills to artistic perfection. Some of his works have been translated into German. The majority of his narratives are about life in the poorer classes and the underworld. His protagonists are the unfortunates, depressed, blind, insane, prostitutes, murderers and suicidals, and he painted them boldly and colorfully, revealing to the reader with satirical cleverness the most concealed images of human struggles in their frailties and abandonment in life. Human suffering, poverty, depression, bitter confusion, and phenomena of fate were the material for his creations.

(from Pinkus Galicia, 1945, pages 241–242)

Conclusion:

For the historian of an existing settlement, a kibbutz, first there is a past that he endeavors to reconstruct on the basis of documents. Not for nothing have historians been called “prophets of yesterday.” He looks backwards, not like a prophet who sees the future as well as the present (time–warp), which passes ceaselessly into the past. The future is not the subject for the historian; he leaves that for the politicians, the columnist, the writer who has imagination, who sees that which is still hidden from the harsh, scholarly eye. Therefore, history has no beginning – because who can dig until the actual 'beginning'? And it has no end, because who can fathom the final days of a living nation?But in our history of the Jewish community in Jezierna – as in the other cities in those districts – we have come, because of the tremendous tragedy that we lived through during the days of Hitler, to the end of the chapter. The Jewish settlement in Jezierna ceased to exist. Of the Jewish town there remains only a memory of those whose origins are from there, who still carry the memories of the town. The memory of the past remains within the organizations that continue the 'golden chain' of the earlier settlement – in their memories, memorials and Yizkor books.

|

|

Shimon Kritz, Haifa

Translated by Ida Selavan Schwarcz

Years have gone by. There have been many changes in the world: nations have gone under, new ones have appeared, among them our state, the State of Israel. I myself am no longer young as in those times in Jezierna… I have children and grandchildren and they live in big houses and beautiful apartments. But when I remember the small town where I was born, the small house in which we lived, and in general, our way of life in those days, it seems to me that it was all a dream of years gone by…

Streets and Alleys

There is a long avenue on the way from Zborow to Tarnopol, and a long road from the train station to Tarnopol Avenue, and on both sides of the two long avenues, there were streets and alleys with small one–story houses, built of bricks in the front and covered with tin sheeting or roof tiles, with a few having thatched roofs. There were also modern houses with porches, surrounded by 'a living green fence', with benches where the family and invited guests used to sit and breathe in the fresh evening air. Such houses belonged to Dr. Litwak, Dr. Tenenbaum, Mosche Heliczer, Zalman Scharer, Schlomo Glass, and others. There were no houses more than one story high in Jezierna.

Further down from the avenues, in the narrow streets where the gentiles lived, most of the houses were built of clay and straw, with straw roofs. The houses which did not have any porches had small stoops. On Saturday the women and children would sit on the stoop and chat.

On Saturday and Sunday the Ringplatz would be cleaned, and there the children played the age–old games “King, King, send me a servant”, zemne, ball and other games.

There were no paved streets yet in Jezierna in those days. On Zabramski Street, the long avenue and other small streets, where few or no Jews lived, each householder had an ‘abaysczia’ that is – a hut, a barn, stalls for the cows and horses and a small sty for pigs, sometimes also stalls for a goat and chickens. They also had yards.

The Ringplatz was also the marketplace, and all around, in the form of the Hebrew letter het –‘ח’, stood Jewish houses and shops. This was the business center. Jews also lived along the length of the two main avenues. The main avenue, Zborow–Tarnopol, which was called Kaiser Strasse, was well maintained, always repaired with ‘szuter’ [gravel]. Originally the road from the town to the train station had been covered with wooden planks. Pools of water collected under the planks and quite often when a heavy wagon passed by, or even a horse and small wagon, the water would spurt out into the driver's face and drench the horses and passersby…Later this avenue was rebuilt. But the surrounding streets, you must understand, were not paved. In the fall, during the rainy season, or when the snow was melting, they, and even the street to the train station, were often covered with mud. Without high boots no one even had the “right” to walk there. If anyone attempted to walk there, even a little way, with galoshes on his shoes, he would often lose one of his galoshes. Even as late as Shavuot it was still necessary to wear high boots in a few side–streets. In order to cross the street from one side to another, stones were paced to make footpaths. It was almost impossible to go by foot from town to the estate.

The Little River

The river played an important role. In the spring and fall it looked like a great river; the water would overflow the banks and flood the surrounding fields and even reach the avenue. The women, especially the peasants, would do their laundry there, and beat the clothes well with a washing bat on a stone. The farmers would drive their horses and wagons into the river and wash the wagon wheels as well as the horses there. In the evening when the cows came home from pasture, they were also driven into the water, where they were washed and watered.

In the wintertime, when the surface of the river was frozen, the children used to skate on the ice, on one foot or on both. Along the snow–covered banks the boys would build forts or throw snowballs. For pious Jews the river had an additional role: On Rosh Hashana they would gather there for Tashlikh [cleansing of sin ceremony.] Men, women and also children would stand on the banks of the river, say the Tashlikh prayers, empty their pockets, and throw their sins of the whole year into the river, so they could swim away to the sea. “Ve– tashlikh bi–metsulat yam” [“and you will throw them into the depths of the sea” –Micah vii:19]. Before Sukkot [Festival of Booths], they would cut the branches of the willow trees which grew on the riverbanks, bring them home and sort them out; the longer and thicker branches were laid on top of the sukkot (and covered with straw or corn stalks) and the smaller ones were used for hoshanas [salvation prayer] for the Hoshana Rabba Festival.

In the summertime some of the men would go to the river in the early morning to bathe and on hot summer days the children would bathe there.

Water and Lighting

Water was pumped from wells. In the center of town there were wells with pumps and many householders would go out every day with buckets and pump water for their household needs, for drinking and cooking. The richer householders would buy water from male or female water–carriers. There was a water–carrier called “Fat Hersch”– a man with a beard, who would go around every day at dawn, with four buckets, two on a shoulder yoke and two in his hands. So burdened, he would sell water. But he had little income from this because his competitors were gentiles who also carried water but charged less. People were already saying that in the bigger towns there was indoor plumbing and people did not have to carry water… Meanwhile, we stayed with the old ways.

On the other hand, the illumination in town underwent an evolution. There had been times when the streets had not been illuminated at all. There was light only when the moon was shining… Later, some poles were put up in the center of town and kerosene lanterns were hung from the top. This happened during the celebration of Kaiser Franz Joseph's birthday. In autumn and winter time at dusk a policeman would go out with a can of kerosene, pour some into the lanterns, and light them. He was always surrounded by children who would stare at him with great curiosity. Most householders did not leave their homes at night, and those who had to go out carried lanterns. At first the lanterns used candles, but later they used kerosene. The tinsmith made the lanterns and he was always introducing new kinds. If someone brought a new lantern from Tarnopol or Zborow, the tinsmith would copy the newer model. The children even carried lanterns to cheyder.

Even greater progress was made by the introduction of gas–lamps in town. These lamps were also lit every evening by the policeman. When the gaslights were lit for the very first time, half the town, mainly children, came to look at the great wonder of the strong lights. “Oh, how light it is now in our town… the lamps shine like the moon!”…

Thanks to the Jewish mill–owner, Jezierna received electric lights. The town was modernized. The last institutions to use candles were the synagogues and the study halls. Long wax candles were used in the synagogues and regular candles were used in the houses of study.

The Marketplace

I want to devote some time to describing the marketplace. There were actually two marketplaces: one in the center of town, where the peasants brought for sale poultry, grain, greens, fruit, etc. and the second place outside the center, named “tarhawicze”, which concentrated on the sale of horses and cattle. On fair–days both places were full of buyers and sellers, especially in the fall and winter time when the peasants would bring out their wares to the fair.

At the marketplace in the center, there were many wagons loaded with poultry, grain, potatoes and fruit. Peasant women would sit on stools or stones with eggs, butter, cheese and smaller amounts of other products, and the wives of the householders would buy them. There were many retail dealers who would go from wagon to wagon, 'feeling' the bodies of the hens, ducks and geese, and finally buy a rooster. In the winter they would buy geese to fatten up for their shmaltz for Passover, and plums to make jam for the wintertime; because in winter the children's bread had to have something to spread on it – and what tasted better than plum jam?

At the tarhawicze market, as mentioned before, horses and cattle were sold. There one could buy or barter horses, cows, calves, goats, and pigs. There was a separate place for each kind of animal. The horse and cattle dealers did not disturb the pig dealers. Only gentiles dealt with the pigs. Every transaction was completed with a 'handshake' and a drink of maharisz. Land owners, land–leasers and farmers – Jews and gentiles – would buy, sell and barter cattle here. For each kind of animal there were experts who 'advised' the buyers and sellers as middlemen – and earned a living thereby. All kinds of specialists would be there – for cattle, Schewach Braun, Sanie Rosenfeld; for horses – Itsie Fuchs, Motje Fuchs and Leibusch Fuchs.

The butchers would buy all the supplies they would need for a week. There were also exporters of cattle and calves who had their agents in the small towns to buy what they needed. The exporters of eggs also had agents there, who would buy any number of eggs, as many as possible.

The Mischief Makers (or: A Merry Tale)

Five to six weeks before the induction of soldiers, which took place in Zborow, the drafted boys could not sleep. They would wander around all night and sing. They would walk to Zborow, Kozlow, Zalosce and request a glass of whiskey from every householder. This is what they would sing:

“Give us a little glass of whiskey,

We want to drink le–chayim;

Wish us that we should remain Jews

And from the Rebbe's table eat shirayim.”

In more recent times the householders did not provide whiskey as in the past, but God helps, as–it–were, the drunkard and sends him the bitter drop.

And here is what happened. The kloiz [small synagogue] was built by Yehoschua Flamm, a rich man with a lot of property in Danilowicz, but he did not have any children. He had built the kloiz and donated a Torah scroll in his and his wife's names. The gabai [warden] was Yaakov Rosen, a dry–goods merchant, a respectable Jew, active in the congregation, who always had some bottles of 96 proof whiskey hidden in the Holy Ark. Every day after prayers he would give some of the men a ‘le–chayim’ drink.

As we mischief–makers marched into the kloiz after Sabbath, we took out ten bottles of whiskey and replaced them with ten bottles of water… In the morning, when Rosen took out a bottle to drink ‘le–chayim’ he saw that it was water. The founder of the kloiz, Yehoschua Flamm, wanted to inform the police. He suspected the writer of these lines. But some of the sons of kloiz members were also involved so the whole matter was hushed up.

|

|

Related by Zvi Zamora

Translated by Tina Lunson

The Jewish settlement in Jezierna was considered a progressive one, and so it had the nickname “Philistine Jezierna”. I came here as a boy from the village Ostaszowce, 3 kilometers distance from the town. But let us first talk a little about the village.

About 300 families lived in the village Ostaszowce, mostly of the Ruthenian–Ukrainian nationality. Poles lived there too, who in no way differentiated themselves from their Ukrainian neighbors. Among all these there were also 12 Jewish families, scattered around the village; the Jews lived very nicely with their non–Jewish neighbors. The Jews drew their livelihood from working a plot of land and from doing a little trade. There were even some who were in a good economic position – they had bigger plots of land and did more trade.

With such a small number of Jews it was not possible to create independent institutions, neither religious nor cultural – so the Jews belonged to the Jezierna Jewish community and it was from there that they reaped their intellectual and religious gratification. And if one wanted to send a boy to cheder [religious elementary school]– one sent him to Jezierna, where there were teachers of various categories, beginning with elementary teachers who taught the child the alphabet, up to Talmud teachers. A child studied with an elementary teacher until age 5. After that he moved on to a teacher of Chumash and Rashi, and later to a Talmud teacher. In Jezierna there was also a 4–grade Jewish public–school where they employed Jewish teachers – that was the Baron Hirsch School. It should be understood that many other villages in the vicinity with few Jewish families maintained the same contact with Jezierna.

Our family was among the earliest settlers in the village of Ostaszowce. My grandfather and probably my great–grandfather lived there from the beginning of the 19th century. The village Jews had lived peacefully together with the local people for generations. My father was one of the property owning Jews; he had his own field and also worked the priest's fields. He used to rent them from the local Ruthenian priest and every few years he renewed the contract. But as a Jew he was tied and bound to Jezierna. And when I became a bigger boy and the village teacher would no longer suffice, I began to go to study in Jezierna.

I went there each day by foot. In summer the way was very pleasant. I passed through green fields, bejeweled with little red flowers. The birds twittered… Crows flew overhead, making round circles and continually calling “kra–kra!” They made a few circuits in the air and then flew lower towards me. And when they recognized me, they cawed again and reckoned that they would not get any subsistence from this little Hershel… then they lifted off and settled a little further along, where a gentile was plowing the field, and where they pulled worms from the freshly–plowed earth and swallowed them hungrily… There were also green meadows with little streams along my way. Long–legged storks wandered through them, using their long beaks to search out frogs… they were not very agile movers on land. I would run to get closer – but the stork did not think for long before flying away… I was left standing there, looking after him and thinking, “If only I had wings…” I would look around, and it was already late, I should have been in school already, and started walking faster. But then, I might encounter a butterfly and I forgot school once again… And sometimes I would meet up with shepherds along the way. “Where are you going, boy?” they would ask. And I would answer, “What's up with you?”, to which I would receive a few clods of dirt. Sometimes too I went with a horse–and–wagon, ours or a neighbor's – but in winter and autumn I stayed in Jezierna for the whole week; my father would take me home for the Sabbath.

In Jezierna I became familiar with the town. I remember her people from before the turn of the century, when I was just a young schoolboy. My first teacher was Reb Alter, Pinchus–the–ritual–slaughterer's son–in–law. The cheder was in the teacher's home; he ate and slept in the same room. In that crowded place the children sat at a table and studied from a prayer book. We would repeat after the teacher whatever he said. The pupils had respect for the Rebi – that's what we called him – and always obeyed him. For disobedience, the Rebi used several drastic, measures, the mildest of which was powerful.

In cheder several, shall–we–say, special events took place. Besides Channuka with its dreydles [spinning tops], which the Rebi made with poured lead and gave out to the students; Purim with its gragers [noise–makers]; Lag B'Oymer when he led the cheder boys to ‘Mount Sinai’ with little rifles – there frequently took place a 'krishmelaynen' [reciting of the Shema (Hear O Israel) prayer]. It was the custom that when a son was born and the child was a few days old, the father would invite a local teacher to come with his pupils to visit the convalescent mother. The woman, hidden behind a white sheet, together with the household members, awaited the guests. The Rebi and the children came into the room and he immediately began to recite “El Melech Ne'eman” [“God is a faithful King” – the opening line of Shema] –– and the children repeated after him with strong high–pitched voices. The children were honored with candies, the Rebi got a shot of brandy and went merrily home with the children.

I remember my Talmud teacher too, Reb Yakov Biller, of blessed memory, a faithful human being who devoted himself to the children. For a certain time I also studied with Reb Chaim Lachman, who was not really a teacher, but a small merchant of charcoal. But when business was poor, and Reb Chaim was a knowledgeable Jew, he took in a few students and studied with them.

In 1898 I was enrolled in the Baron Hirsch School. There one studied according to the government plan. The language of instruction was Polish, but religion was taught in Hebrew. Some in the orthodox circles had no desire to send their children to that type of Jewish school because of the whiff of apikorsos [heresy] that they smelled from it… We did indeed study bare–headed in that place and the teachers were progressive people. The principal was Blaustein and the teachers were Imber, Feldman, the Misses Faust and Brik. After completing the 4 grades of the school, I of course went back to study in cheders.

The first years of the century. National consciousness began to develop among the Jewish youth and Zionism also arrived in Jezierna… Then a few Jews organized the first Zionist society. We used to meet in the home of Reb Josef Steiger (Yosi –Yizchok's); his low little house stood at

the rear of the market square. There was a newspaper. We read and discussed world events and political Zionism. That was the only place where Jews used to gather, besides the synagogues. That same Yosi –Yizchok's was occupied with other community activities: along with other Jews he organized a gemiles–chesed [free–loan] society. If a poor Jew needed to buy some merchandise for the fair, he could borrow a little money there without interest; thus, he could earn money to buy food for the Sabbath. When Reb Josef passed away, the work was taken up by his son Luzer Steiger, who was murdered with all the Jews in the great Holocaust.

But politics one could hear about in other places, in particular the synagogue study hall. That was the era of the Russo–Japanese War, in 1904. The Jews in the Austrian Empire were then pro–Japanese and against tsarist Russia where antisemitism was rampant. It was that way in Jezierna too. We only debated the outcome of the war, we tossed it around … we followed the battles as though we were generals. Reb Nuchim Schonhaut, Pinchus the–ritual–slaughterer's son, brought home a newspaper especially from Lemberg (one could not get such a thing in Jezierna…) and reading it, saw the whole strategy of the war. He had the map in front of him and he predicted that Japan would win. And when Japan did win – he got the nickname Yapantshik.

In those days there was this story: Scholem Francas, the son of the Rabbi's gabai [beadle], who sat day and night with the Rabbi in the small prayer house and studied, who wore long peyos [sidelocks], a long coat and velvet cap, disappeared one fine morning and showed up in the Austro–Hungarian capital– Vienna. There he put on modern clothing, shaved his beard and sidelocks and was accepted in a high school. He graduated and enrolled in the university and used to come home to his sister – his parents were no longer alive. He had changed so much that people did not recognize him. He later became a mathematics instructor in Tarnopol.

During that time the Jewish youth in Jezierna in general were eager to go to the larger cities. We wanted to be ‘menschen’ [regular human beings]. There began to emerge Jewish officials, Jewish secondary schools, and the youth sought a purpose.

|

|

A. M. Fuchs

Translated by Lily Fox Shine and Cyril Fox, niece and nephew of the author

Donated by David Fielker, for this article which was previously

published in Shemot (JGS of Great Britain), September 1999

My birthplace, the shtetl Jezierna, on the railway line from Lemberg to Tarnopol in Eastern Galicia, belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire under Emperor Franz Joseph. In WWI the Jewish population became dispersed. In 1918-20, when the monarchy collapsed, Jezierna, and indeed Eastern Galicia (including the Western Ukraine), belonged to the Ruthenian Republic. Then, when the Poles won the war against the Ruthenians, Jezierna became part of Poland and the shtetl rebuilt itself. Today [1969] my birthplace belongs to the Soviet West Ukrainian Republic again.

I did not know my paternal grandparents, but I am named Avrom Moshe after my grandfather. I do know that he was a small-time merchant selling produce to the peasants of the surrounding area. He was a Baal Tefilah (lay prayer leader) in the Beth Hamidrash of the main synagogue. My grandmother, Channa, ran a small dairy. My father was known in the shtetl by the nickname Chaim Chanele's Smetankes because of this and because he was very blond- an allusion to the white Smetana which was made in the dairy.

My maternal grandfather was Sholem Fuchs, and my grandmother was Leika (Esther Leah). The family on both sides was related. Grandfather Sholem was a merchant, dealing with the Polish peasants and gentry, and in the summer he rented orchards in the neighbouring villages. Leika also had a bakery in their large house, making challoth [sabbath loaves], rolls, etc. The customers were the people of the shtetl and the country folk. Every Passover eve they baked matzos in the great stove for the entire locality. Shulim and Leika died in Jezierna in 1910.

In my family we were four brothers. I was the oldest, then Shea (Yehoshua), Hersh and Itamar.

In my childhood and youth, I was naturally close to my relations. They still stand before my eyes, all in youthful fellowship, fine people, cut off from life by fire and blood. I come from simple, honest, god-fearing people who were pleasant, good-humoured and friendly, and happy to do good deeds and help others. They all had some type of work in the shtetl – bakers, carpenters, locksmiths, merchants and orchard keepers. Some sold flax or honey or wheat; some had a horse and cart for transport. Summer and winter they scraped a hard-earned living. Only on the Sabbath and on festivals did they rest and have a party. They all suffered from the pain and harshness of their livelihoods.

There were also happy times: joys and pleasures from their children. The boys went to cheder, learning Hebrew, prayers and the Bible, then they learned a trade. The daughters, the young ladies, learned Hebrew and also Hebrew/Yiddish translation, ie tzena-urena [pious texts]. The fathers, with difficulty, paid the teacher. At home the daughters loved to sing Yiddish folk songs. They could speak Ukrainian, Polish and Yiddish. They were raised in the best ways of their parents until they were married. They were brought up to be well-mannered and modest. The mothers were orthodox and scrupulously observed dietary laws, Sabbath and festivals. They prayed with fervour, crying out to God.

Their literature consisted of holy commentaries and stories from the Bible, and later they read Yiddish story books, for example from Sholem Aleichem and Mendele, which they bought in the market place. They enjoyed listening to storytellers, jokers and singers, especially at Purim. Although they were not Chassidim, they would go to the Jezierna Rebbe during the intermediate days of Passover for blessing and advice.

The Jezierna Rebbe, Levi Yitzhak Manisohn from the Rhziner dynasty, was well known in the surrounding towns. He had a large following of Chassidim who used to stay with him. He had a large house with a courtyard and a small school with teachers. In my youth I saw him many times; he was short and slim with a delicate pale face, brown eyes and a short tidy silver beard and short curly sideburns. On the Sabbath and on festivals he dressed in silk striped trousers with a white girdle, white silk shoes and stockings and a large golden fur hat. His weekly attire was a black silk hat, black silk coat with velvet sleeves and black patent small boots. I also heard that the Rebbe had written a small religious treatise, but I personally had another book printed in Hebrew from one of his followers with a foreword from him. In WWI the Rebbe's mansion was destroyed and he and his son Reb Moishele fled to Vienna; the Rebbe died shortly afterwards in 1915 and two years later his son died there.

In the mid-19th century there was also a greatly revered rabbi, Rebbe Shloimele, who grew up in the shtetl. The Emperor Franz Josef ruled at this time and a special stone synagogue was built, which lasted until 1941 when the Nazis destroyed it. The Rebbe was deaf and had poor vision, yet busied himself with teaching and many good deeds to humans and animals. In my youth, I once went with my father to visit ancestral graves and I saw the special private burial memorial to R Shloimele. It was a small room in which stood the memorial stone, old and worn, in the form of two tablets, on which the symbolic Cohanim fingers, thin and worn, were outstretched in blessing. The words were faded away but my memory of this is inerasable.

I remember that years ago in my childhood days misfortune befell our family. My father, a quiet, refined man, was not in the best of health and had no means of livelihood at the time. My mother went for advice to a special rebbe in Tarnopol. This Rebbe Lazar gave her a blessing and good advice which was that my father should become a merchant and rent orchards together with his father-in-law and brothers-in-law and with God's help he would be successful. So it turned out, and my mother used to talk, with tears in her eyes, about the wonderful advice and how our faith had saved us.

So, my family mainly lived on the sale of fruit from the orchards they rented from the Polish gentry, which produced cherries, grapes for wine and later apples, pears and plums. They gathered the fruit, loaded it in boxes and sacks onto wagons and sent it for sale in the Jezierna market. They worked from Shavuoth to Rosh Hashanah and shared the profits. Unripened fruit was stored in straw and sold when fruit became scarce. This was my father's business too; he had his own horse and wagon. They also owned a small spice and condiment shop, but this was destroyed by thieving village lads.

Another group of memories appears before my eyes. My father had a lime pit and a small hut which stood at the edge of my grandfather's garden. In the front it was partitioned with flower boxes, thorny bushes and trees overhanging from the very large garden of the Ruthenian priest. There was a refuse bin and a lime pit in the large cattle, horse and pig market. The general market place, with Jewish wine establishments and shops, was in the centre of the shtetl. Nearby was the old stone synagogue, the Beth Hamidrash, the Rabbi's house and also the Polish and Ruthenian churches with their high bell towers.

The Chassidic Rebbe's courtyard with a large garden was on the side of the stone cobbled Kaiser Strasse. The old stone brandy inn had a wide entrance for the horses and wagons of the Polish gentry who would gather there, perhaps some of the wealthier Jews. The old flour mill with its huge wooden water wheel stood by the side of the stream, a tributary of the wide river with tall willow trees on its banks.

Like all Jewish boys in our town I went through four classes in our state Jewish Baron de Hirsch School. The official language was Polish, but I also went to learn Jewish subjects more intensely at the cheder where the teacher was Reb Lazar Bick. I studied Hebrew and the Bible with Rashi and some Talmud. Later, I educated myself more deeply in Jewish subjects and world culture.

At the age of fourteen I went from my home to Lemberg, then for a while in New York and after that for 24 years in Vienna, ten years in London and a little time in Paris. From 1910 onwards, my main profession was that of a Yiddish writer and journalist, mainly in Vienna and later in London

In Vienna I was conscripted into the Austrian army in various military capacities between 1914 and 1918, going as far as the borders of Austro-Hungary.

After WWI I was able to return to Jezierna. The German troops had fought backwards and forwards against the Russians as far as the Russian border, passing through Lemberg and Jezierna. There was great slaughter of Jews in this area by the Russians, Austrians and Germans. Many of the villages were destroyed. The Jews of Jezierna and the surrounding villages fled over the Carpathian Mountains to Hungary, where there was a camp for Jezierna Jewish refugees. After the War the Jews returned to Jezierna but many of their homes had been robbed, burnt down or destroyed. Their livelihoods were non-existent and hunger and poverty were everywhere.

Now the Ruthenians governed the area, but there was no stability as they were still at war with the Poles in East Galicia. Also in 1919-20 there was war with the new Soviets along the borders of Russia and East Galicia, and Petlyura's Ukrainian soldiers conducted pogroms against the Jewish inhabitants, plundering villages and murdering Jews all along the border towns. In East Galicia the Red Army did help somewhat to protect the Jews as Petlyura's men rampaged through Jezierna. Then came the Polish legions, murdering Jews in Lemberg and other Galician towns. The slaughter also took place in Zlocov. Then East Galicia was occupied by Ruthenian soldiers and cut off from the outside world, without communications or transport.

Very sad news filtered through from this area to Vienna concerning the savagery of Petlyura towards the Jews of Galicia and the Ukraine. I was sent as an accredited correspondent for the Wiener Morning Journal, the Jewish national paper, to investigate and report on the conditions of the Jews of East Galicia and bring back the true facts to Vienna. In 1919 my journey was very difficult; I had to travel for weeks by train via Budapest and Muncacz and through the Carpathian Mountains and by this roundabout way I arrived in Tarnopol.

This large town was half destroyed, the shops were looted and only a handful of Jews were left. Some of the army had returned, and they were wounded and robbed by Petlyura's men who were running the town and had murdered most of its Jews. No train journey was possible for civilians; I travelled on Polish sledges for which I paid exorbitantly. The weather was cold, frosty and at times stormy. At night in the snowy fields there were howling, hungry wolves. With fear and trepidation I went on and whenever I met with Jews in the area the same pitiful story was told – poverty, robbery, pursuit and often murder. The days and nights passed with pain and terror.

The young Jewish soldiers who had returned from the Austrian front were weary and with difficulty they carried on trying to earn some money to help their broken parents.

Naturally I went to Jezierna as quickly as possible to reunite with my parents and family, who had returned from their flight to Hungary. I also went from Tarnopol to the border towns between Russia and Galicia. On this trip I was arrested several times by Petlyura's soldiers but my documents and newspaper credentials from Vienna saved me and some honest Ruthenian officials came to my rescue and freed me from custody. The Jews were not taken to serve in the Ruthenian army and on the whole the Ruthenian government protected the Jews in Eastern Galicia, but over the border the Petlyurian gangster army, who were Ukrainians fighting the Red Army in Kiev and other Ukrainian towns, massacred any Jews they found.

On 29 January 1919 I was in Tarnopol where I received the news, from Austrian soldiers returning from the Russian border, of the terrible pogrom the day before in Proscurów, where Petlyura's men had killed 1,500 Jews in a day when they captured the town from the Reds.

The same hatred existed towards the Jews of Western Galicia by the Polish National Army where there were also pogroms and slaughter. Jews were accused of being leaders of the Communist revolution, especially because of Trotsky, Zimoniev and Kaganovitch, and they also supported the Communist uprising in Hungary where Bela Kun, the leader, was a Jew. In general the expression was “Jewish Bolshevik”. With all these pogroms organised by different armies over the area it is estimated that more than half a million Jews were murdered. Villages became seas of Jewish blood; all were united in their hatred of the Jews. Ovruch, Berdichev, Zhitomir and Proscurów were some of the towns that Petlyura swept through, moving from house to house murdering Jews. In 1919 there were 493 pogroms. I finally returned to Vienna with my report.

In 1923 my father (not so old) had died from all the troubles in Jezierna and my brother Yehoshua took my mother to London, where she died in 1942. Yehoshua also brought my brother Itamar to London from Vienna in 1930. The families of my father's three brothers and two sisters from Jezierna all emigrated to America and England before WWI.

I had settled in Vienna with my wife and daughter and was an established citizen of the new Austrian Republic. However, in 1938 when Hitler marched into Austria I was imprisoned with my family and robbed of my possessions. Many precious manuscripts, stories and articles were destroyed. Then with the help of my brothers and their family in England we were saved*.

Jezierna was occupied by the Soviets from September 1939 until June 1941, but in July they withdrew from Eastern Galicia and the Nazis entered Jezierna and slaughtered most of the Jewish population. My brother Hersh was murdered by the Nazis in Slochev, together with his wife Miriam and all the Jews of the town, in 1941. My mother had three sisters and a brother, all with large families; they virtually all perished under the Nazis and only a very few survived. From my grandparents on my mother's side there was a large family with brothers and sisters in Jezierna, Zborov, Tarnopol, Lemberg and Czernovitz; they also perished in the Holocaust.

We lived in London from 1937 to 1948, survived the Blitz and Hitler's bombs in WWII and made aliyah and settled in Tel Aviv, Israel.

For 25 years AMF was the Vienna correspondent of the New York Jewish Daily Forward. He was also assistant editor of the Jewish Morning Post in Vienna and critic for a monthly journal, as well as contributing to many Jewish papers and books. He published six books of Yiddish stories, many about life in Jezierna. The articles about the pogroms for the Vienna Jewish Daily News were also translated and printed in America, Poland and other countries. Later he wrote stories with themes on the terrible breakdown and impoverished hard life of the Jews of Western Galicia at that time (1919). His books were translated into Hebrew, German, Polish and other languages and he received several literary prizes, including a major award in Israel late in his life.* Primarily it was AMF's American Press Card that saved him from the Nazis in 1938. Return

[Page 88]

I. A. Lisky

|

ּי. א. ליסקי

לערנט זיי ליינען אייך א ליד --

ניט א ליד מיט לידער גלייך --

א ליד געשריבן פון אן ייד --

עס איז דער ציטער אין דעם ליד -

מיט דעם כוח פון זיין לאנד --

דאס ליד געשריבן פון א ייד --

געשריבן האט דער נביא מיט א ברען

עס איז דער ברען, דער כוח פון

פון זיין ליד, דעם ברען און דעם

דורכגעברענט דאס ליד אין זיין געמיט --

(פון "געזאנגען צו מדינת ישראל" |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ozerna, Ukraine

Ozerna, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 3 Apr 2020 by LA