|

|

|

|

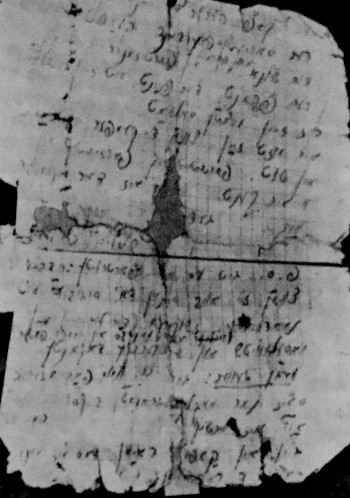

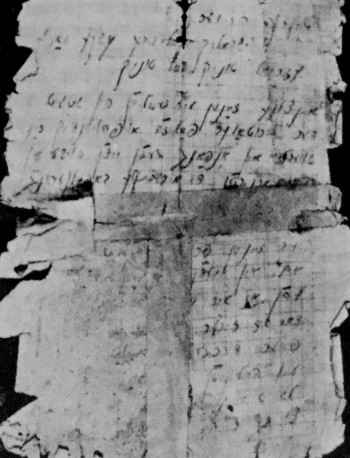

Siyomka Farfel's letter to his friend in the Stolpce ghetto

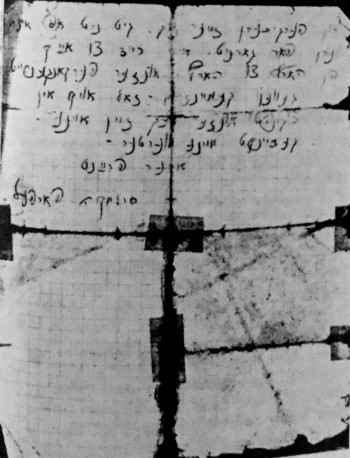

Sholom Cholavsky's letter of to his friend in the Stolpce ghetto

|

|

[Page 140]

Under Seige (cont.) The Forest

Most of the groups and the units that fled from the towns of Nesvizh, Kletzk, Lachovitz, which lay a distance of 10–30 kilometers west of the previous Polish–Soviet border, and from Kopyl, and Timkovici, from the east of it after the wave of destruction that passed over them in July 1942, turned to the forests in the area of Kopyl near the old border. Fate summoned them together. They moved east from the ghettos west of the border. Their senses whispered to them: if there is truth in the vague rumors that circulated in the ghetto about the presence of the partisans in the area, surely they were encamped in the area that was easy for them – across the border to the east. This feeling received the approval of the guidance that isolated farmers sometimes agreed to give. The Jews that escaped from Kopyl wandered less, since the Partisans had reached their town, and individual Jews fled from it in advance to the forest and successfully formed a secret connection to other Jews.

Two groups from the Nesvizh ghetto that revolted emerged in two different directions. My group turned east – to the region of Kopyl, and the Damesek–Alperovich group turned west – to the forests of Mir. The Meirovitz–Geller group (within it also Leah Fish, Rachel Yucha) from Kletzk, and the individuals that remained in Lachovitz with Yosef Peker also turned towards Kopyl. Others arrived in addition to us, among them Simcha Rozin, Michael Fish – both of them from Nesvizh.

In the hour that destruction began in the towns of the area there were already groups of Jews and individuals that wandered around, while seeking a connection to the Partisans.

These days of July were extremely hot; people crawled on the roads exhausted and worn out. On the second day after our flight we – Siyomka Farfel, Shmuel Nisenbaum and I – knocked on the door of a farmer's house in Vinklerovshetzina [abt 53°17.5' N 26°45' E], a village adjacent to Nesvizh. While offering us a little food, he said: “the Jews from Nesvizh revealed their ability. Almost the entire city has been burned by fire. There are 40 killed or wounded German policemen.” His words were almost not perceived by our awareness. Everything that happened to us and that occurred around us in the last days had not yet penetrated our consciousness; we were very dumbfounded and worn out. The berries – almost the only food in the days of wandering with bent backs, caused us dizziness. Crawling or laying down, we moved from berry to berry.

As we approached the edge of the city, farm women who were returning from the fields happened upon our path with sickles in their hands. When they saw us, they burst out in screams and fled for their lives with terrified cries. According to what became clear afterwards, they were afraid lest we abuse them and cut out their tongues (The Germans spread rumors that the escaped Jews were abusing the Gentiles). We became a wonder in our own eyes. We were amazed that it was possible that we were likely to be seen as cruel. On the next day, with dawn, we met a young shepherd. At first she recoiled a little, and afterwards she said what was in her heart: “you will live maybe a week of days, and the Germans will kill you anyhow.”

It is possible that the women farmers and the shepherd were right; our appearance also terrified and aroused fear and helplessness all at once. In the fields and forests, quiet prevailed. It was not soothing, but pressurized, tense, like after a great and terrifying fire.

We heard echoes of gunshots. Gunshots in the middle of 1942. Unlike the gunshots in 1941 between the retreating Red Army and the invader, which aroused illusions that redemption could come near, these gunshots could have one of two meanings: either the murder of Jews, or battles between the Partisans and the Germans. Since in that area there was not even one Jewish settlement, the meaning of the gunshots was clear. Farmers let us know about a battle that occurred a few days before between the Partisans and the Germans near the town of Rayevka [probably Malaya Rayevka, 53°08' N 26°52' E].

Rayevka was a place where the groups of Jews and individuals arrived, without previously knowing the name of the place. Some of them arrived there after two or three days, some after a week, by way of the forests of Yevitsha and Lavy [probably 53°17' N 28°01' E].

Groups of Jews and individuals that emerged from the towns of Nesvizh, Kletzk, and Lachovitz, which were located on the west of the previous Polish–Soviet border, and from the towns of Kopyl and Timkovici, which were located east of it, turned to the block of forests that was in the area of Kopyl. A wave of destruction passed through these areas in July 1942. Fate befell them together. Those that emerged from the “western” ghettos, their senses told them: if there are really Partisans in the area, and if there is truth in the vague rumors that were in the ghetto about their existence, then they are surely encamped in the more comfortable area: east of the border. Farmers that we met would indicate with their hands – go east.

The Jews that emerged from Kopyl wandered less. There were in their towns individual Jews who went out to the forest earlier. The renown of the Partisans and their location certainly reached them. The Meirovitz–Geller group from Kletsk and the Yosef Peker group from Lachovitz – they too turned towards Kopyl. To our group were added Simcha Rozin and Michael Fish, who emerged individually from the Nesvizh ghetto.

Individual Jews wandered in the forests of the area when they were searching for a Partisan “address.”

[Page 141]

The wandering, even though it was not long, was pregnant with dangers. Many were the farmers who spied in the fields and the forests for the price of a handful of salt and a pound of kerosene, and occasionally not for a wage, but out of “enthusiasm.” This danger reduced the number of villages that were liable to the supervision of the Partisans in the Soviet area. In the village of Yevitsha [location unknown] the farmers welcomed the Partisans and also individual groups of Jews. Groups of Jews would enter this village towards evening and would receive a little cooked food and even be supplied with provisions. Rachel Filler, who fled with her son Shraga from Vishkov [location uncertain, possibly Wyszków, Poland] to Timkovici and from there to Kopyl and from Kopyl back to Timkovici related: “after I came out of the bunker in Timkovici with my son, I wandered in the forests and I trembled at the sound of a falling leaf. With me was a bundle of clothing that I saved to sustain myself. Once a farmer burst out across from me from among the bushes. I was horrified. He asked: “Who are you?” Quickly, with the speed of lightening, various thoughts went through my mind. What to tell him? What is less dangerous? Finally I said: “I am crazy!” The farmer said: “If you are testifying in this way about yourself, you are surely not like that. Why don't you go to the Partisans?” I said: “I don't have a rifle.” He said: “I have a rifle, what will you give me for it? What do you have?” I was afraid lest he wanted to rob. But the farmer said that we should wait for him for about ten minutes, and he went. I was afraid that maybe he would bring Germans. I said to the son: “Let's flee!” But on the other hand, I weighed in my heart: How many Germans would he need to kill me? He did not intend this. He could actually have done it by himself, without help. After a few minutes, the famer appeared with an ax in his hand. I started to tremble terribly, my teeth knocking against each other. He opened his mouth and said: “Be quiet!” He went over to a tree and struck it with the ax a few times, and from its hollow trunk he took out a rifle and gave it to me. I did not know how to thank him. In addition to that he equipped us with a little food. In my eyes he seemed like an angel. I gave him a jacket, a few meters of fabric. Thanks to the rifle I was accepted into the Partisans. This rifle was one of the first in the organized unit.”

Similarly, it was also possible to encounter individuals in other places in the same area, in the previous Soviet sector. But there was also danger in this sector. Occasionally, ten good men would not be enough to save you. But one contemptible person was enough to plot against your life.

In Rayevka, a unit of the Russian Partisans was encamped. Part of them were prisoners of war that had fled from the prison camps. The rest of them were local people, and Red Army soldiers, who were not taken captive, but had hidden in the farmers' houses for the winter days, and when spring came they went out, not many of them, with meagre weapons, to the forest.

Over the course of two–three months, the group expanded and increased, and with the arrival of the Jews in July of that year, their numbers reached 70–80 people. This was a small unit, apparently, but the area of its control sprawled over many towns and villages on the way to Minsk in the north, the swamps of Polesia in the south, and the Naliboki forests on the west. Groups of its operation reached distant regions, and in their passing by villages they worked, to the best of their ability, to create the impression of large armed units. These groups became the subject of conversations among the farmers, who would whisper that large Soviet forces were moving in the area. But essentially, the unit stamped its impression in the area of the villages and towns near its base. Within a short time, the Partisans succeeded in making close contact with the population, acquiring a good name, and appearing as an organized and disciplined body, and, most importantly, displaying power. The ambush that the unit made in the second half of the month of July on a German military convoy in the area of Rayevka bequeathed a great victory to the Partisans. This was the greatest contest that defeated the German military garrison in this sector until then. The battled lasted 5–6 hours. More than 35 German soldiers were killed or wounded. The Partisans' losses were minimal, except for a number of wounded. It destroyed the halo that surrounded the German military garrisons in the region. But, not less than this, its influence on the spirit of the population was great. This battle convinced, brought the population close to the fighters of the forest. The Partisans began to appear in daylight in the nearby villages; Lavy, Yevitsha, and Yazvina [possibly Yazviny, 53°24' N 26°55' E]. Indeed, when a Partisan patrol appeared in daylight on the road that crossed the village, on its impressive horses and partially dressed in military uniforms, and a kubanka[1] with a Red star, armed and ready for battle, in the summer months of 1942, the time in which the German army reached its pinnacle in its stand on the approaches of the Caucasus and in the regions of Moscow and Leningrad, indeed, this sight of armed Partisans greatly impressed the farmers. However, the confiscation of food from the farmers at that time did not much cloud the relationship with the population, since the Partisans' confiscation never reached the level of the organized plunder of the German invaders. The farmer was subjected to only these two possibilities. Indeed, the Partisans had the practice of “taking” “live food” – meat – from the farms that were subjected to German supervision, and this alleviated the burden of the “taxes.”

This unit expanded, and over many days branched out and split into a few battle groups: Dunaivitzim, Eremenko, Shtopflov, which in the course of time became brigades. At the head of these units stood the Major–General F. P. Kapusta (his real name was Bozenko, who was at that time a Major), who afterwards was the commander of a great and acclaimed kidnapping.

When we reached the camp, Kapusta received us, accompanied by one of his comrades. He was a man older than 40, tall and powerful. One of his hands was bandaged and placed in a sling that was hung around his neck – he was wounded, as we learned afterwards, in a battle at Rayevka. Also, the not–recent scar below his forehead gave him the appearance of a veteran warrior. His facial expression had the gravity of an officer and the simplicity of a Russian citizen all at once. His face expressed great self–confidence, and his character inspired encouragement in us. We saw in him a man faithful to the path of his life and to his principles. He asked us from which ghettos we had emerged, and why we had tarried in them, and was interested in the number of people who knew how to hold a weapon in their hands. At the end of the conversation he gave us our first task: the acquisition of weapons.

More than 40 people gathered in the forest. The Jewish base was located a distance of a one–kilometer walk from the Partisan base. In general, difficulties were not caused for Jews who reached the forest. Only girls and women whose faces looked Aryan, and because of that were suspected of spying, were interrogated thoroughly, but afterwards they were freed and joined the Jewish camp. In the Jewish camp, most of them were young men. Among them were also young women and a few adults from the area of Kopyl. Viener, a member of the group from Kopyl, who had earned the confidence of the Russian command, was appointed temporarily as the one responsible for the base. At the beginning, a few huts were put up, a temporary kitchen was organized, and the people were invigorated by the large quantities of food, which for many days had not come to their mouths. Despite this, the people walked around withdrawn into themselves, slept most of the day, fighting for sleep or daydreaming. The smell of the ghetto still wafted from their clothing, and the terrors of the escape were still visible in their eyes. The past still weighed on their souls, and the heart had not yet opened to the future.

The thing that began to bring the people closer together was the campfire in the evenings. Who would know how to describe their experiences around the campfire, the horrors that they endured, and the hope that they nurtured in their hearts, but each person found in it what they sought. It revived the people, warmed them, and brought them closer together. With branched “forks,” the young people were seated, bundled and sooty, around the fire. They dried the green tobacco leaves, drying and turning, until the leaf became brown and dry. Afterwards, they crushed handfuls of it between their fingers and they poured the crumbs, which were quite large, into a long piece of paper that was cut from a newspaper, and after rolling and gluing it became the “classic” Partisan cigarette whose length was about three quarters of a pencil, and twice as thick. From it, they would order a “puff,” or 30% or 40%. At the time of this “work,” people exchanged familiar questions, and even if the mentality of a western Jew differed from an eastern Jew, there wasn't a division between them – the shared fate of the Jew was stronger than everything. Their short, quick, conversations – from the new way of life and its problems, tore an opening, although narrow, to emerge from the world of horror from which they fled.

Already in the first days of the gathering, the group of Jews participated in

[Page 142]

“the action.” Without weapons in hand the Jewish youth joined an armed squad of Partisans for a raid on the Sovkhoz[2] farm, which was under the supervision and protection of the Germans, in order to “purify it” of the living inventory and other food necessities. The Jewish youths marched with empty hands, under the cover of the Partisans' weapons, facing the fire of the German patrol. That same night, tens of cows and pigs were brought to the Partisan camp. But the essential function that was placed before the organized unit was the acquisition of arms. With Kapusta's encouragement, a number of groups went out on searches. Kapusta's advice was to turn towards the former Soviet–Polish border, where battles took place between the invader and the Red army. In his opinion, it was possible to find arms there that were abandoned by the retreating army.

And indeed, I, Rozin, Nisenbaum, and a few others went out in the direction of Stolpce, towards Kletzk. Meirovitz went out accompanied by a group. They were equipped with “otrazim” (otraz – a rifle with a partially shortened barrel). My group reached the Haniman sector in the area of the village of Yazviny, but no weapons were found in this entire area. It may be that after the battle it was possible to find Soviet weapons in this area, but the farmers, who knew the forest paths well, collected and hid them when battles took place here. On the way, the group made a connection with one Polish family, the Semkovitz family, who revealed great empathy with the anti–German struggle and welcomed the Jewish Partisans hospitably. Over the course of time this family became a great help to the people of the unit in their connections to the Stolpce ghetto, and the work camp in Sverzhna.

The Meirovitz–Geller group, which reached the area of the town of Kletzk, also returned in the same way it had gone out.

The Partisans were not accustomed to spending much time in one forest, even when the eyes of the enemy were not watching them. From time to time, they moved to another forest in the same area, which was blessed with wonderful pine forests. From Rayevka, the group moved to the Volozhin forest.

The organized Jewish unit expanded a little more. A few individuals, who had wandered on the paths until then, reached it from the forests of the area. Adjacent to it, a distance of a few hundred meters, a Jewish family who had fled from Grozovo “settled”: a blacksmith, his wife, his old mother–in–law, and his three small children. Their family name was Shklor. This was the beginning of the family camp. More than one of the Jewish unit visited the nest of this Jewish family, and managed, with feelings of fear and love, to bring them a little food to sustain them. It seems that the thing that drew the Jewish Partisans, remnants of many families, was to feast their eyes on an intact Jewish family. The smith and the members of his family were Jewish folk, quiet and amiable. Simplicity and good–heartedness permeated them. They accepted fate with submission. Submission that had no despair in it. This lack of despair amazed many. The capacity for adaptation, not found in the conditions of the place and life, was hidden in them. The strange hardships of the forest did not cause them shame, only a constricted internal fear and courage combined with discretion and mature determination. With great spiritual heroism, this family struggled for its existence and succeeded.

Searches for Weapons

At the end of August 1942, the Soviet command appointed Giltzik as commander of the Jewish unit. Giltzik, a Soviet Jew was a Kopyl man, and the Soviet command that fell to his Partisan lot placed greater confidence in a “Mizrachi”[3] man. However, in addition to this, Giltzik was close to the Command Headquarters. He was a scout in a Partisan command that indeed knew the sector excellently. It happened in Kopyl that he served as the director of the cattle division. By virtue of his role he came into contact with the farmers of the area, and knew the area well. He went out to the forest early, but once at night, when he was coming to his house secretly for a visit, Germans and policemen burst in. Giltzik hid, and in his place, they caught his Christian wife and his two children. Despite the tortures that they suffered, the children and their mother did not reveal their father's hiding place. They were shot. Giltzik succeeded in returning to the forest.

Giltzik was a man of the folk, simple, practical, and devoted to his role. He knew the area well. He didn't speak much about general matters or on Jewish issues, but when they detailed the Jewish excess, he responded. He knew how to protect his Jewish honor, if someone offended him. He arrived at the camp armed with a weapon.

His first act was searching for weapons. This was not easy work. The farmers hid most of the weapons for their own purposes, and did not hand them over. Even when they confirmed that so–and–so had a weapon, more than once they needed to use force against him to extract it from them.

One–time information that was of great importance for the Jewish unit reached the headquarters from one of the farmers, that in one of the places in the region of Kopyl, in a communal grave of Red Army soldiers, the soldiers' weapons were also buried. That was how the Germans operated in certain circumstances: in order to express their contempt for the Red Army, they had the practice of burying the soldiers with their weapons. A large communal grave like this one was discovered by a farmer.

That same night we went out, a group of Jewish youths with Giltzik at the head, to the communal grave. We opened it at night and from among the bones of the skeletons we removed weapons that were covered in sticky earth. Deathly trembling and holiness encompassed us during the time of the work.

When we returned to the camp with a wagon loaded down with the cargo, a rustle passed through the camp from one end to the other. While it was still day, rows upon rows of campfires were lit. 35 young men began to attend to the long chunks of earth, a chunk of earth to each person. With knives, with irons, and with stones they scraped off the dirt that was stuck to the iron of the weapons. The earth in whose defense the soldiers from the Red Army fell clung inseparably to their blood and their weapons, until it began to erode the weapons. These clumps of earth became clumps of human–blood–and–weapon, a symbol of the defensive war of a nation. We sensed that there was no weaponry like this to avenge, and we absorbed its spirit; we lived the symbol completely. Indeed, it was fitting for us – and we, for it. We sat in the evening. All that night, the campfires were not extinguished, and the people, sooty from the tongues of flame, engaged in the work, and even the next day they continued their holy work. These were a night and a day when many contributed to the design of the image of the fighter of the Jewish unit.

Most of the weapons – 35 rifles – were regular Russian rifles, and some were semi–automatic (semi–automatic – a cartridge with ten bullets), and one machine gun. After its cleaning, I brought, together with Siyomka Farfel and Shmuel Nissenbaum, a few carpenters' workshops and work tools from the Veleshin [possibly 53°11' N 27°08' E] kolkhoz[4] that was about 3–4 kilometers from the forest, and we began the work of making gunstocks for the rifles.

Within a few days most of the young men were equipped with rifles. The unit was known as an independent Jewish unit named for Zhukov – the rising star at that time of the officers of the Red Army, and was placed under the regional Partisan command of Kopyl, at whose head stood Kapusta (Bozenko). We stood with weapons in hand.

Here a miraculous change took place. Not only defensive and attack tools were placed in your hand, but also tools that changed your view of your surroundings. With this tool, we breathed a new and deep breath. Full of nothing – to absolute rule. It seemed that everything was yours. There was nothing that you couldn't conquer with the power of the weapon. Only yesterday, we wandered in fields and villages, despondent, trembling at every sword thrust and sound, afraid of the eye of the day, but today in our emergence from the forest riding or on foot, with the weapon hanging from our necks, our heads held high, like lords of the land, the field, life. All of us sensed a wonderful growth within us, in the confidence that was poured into us, with a deep, deep breath.

Kapusta's Brigade

But not only because of the arms.

Kapusta's unit grew a great deal, and at the end of the summer of 1942 it split into a few units. Units were organized by Shestopblov, Yerminko, Doniev, and although most of the new people that reached the forest fled from prison camps, among the people of the authority of the units there was a small group of idealist people who molded the spirit of the units, poured into them a combat and social spirit.

[Page 143]

For as much as prisoners of the war were early to join the Partisan unit, so did the Partisans limit absorbing into themselves the corrupt and demoralizing atmosphere of the prisoners. And if in the unit those who joined it found a good and proper spirit, these did not dare to lift their heads and “toe the line.” Within a short time, there arose a Partisan brigade under Kapusta's command, and the Jewish Zhukov unit became one of its units.

This brigade had, largely thanks to the headquarters, great authority in the entire sector, which with the passage of time extended to the other sectors. In these units, you found various personalities that had strength, influence, and battle ability, and the head of all of them was the head of the brigade itself. But above all was lifted the name of the extolled Partisan leader, and his name was Doniev.

He was a Russian of about 30 years old. Blond, average height, dressed in a Russian military suit and round hat, with a very alert face and blazing eyes. He was the most military commander among them all, and was endowed with a special sense of how to influence the population and the many farmers; he knew the soul of the nation. His appearance in the villages accompanied by his entourage was an experience. In battle campaigns, he succeeded in cunningly hiding snares for the Germans by means of small groups of fighters.

He had the practice of surprising. On one of the first days of August 1942, he appeared in the light of day in a church full of worshippers (on the approaches to the town he stationed ambushes for the German forces) and accompanied by his entourage, he went up on the podium and offered an impressive Partisan speech, in the style and spirit of the farmers. The entire village streamed to the church and the “worship” quickly turned into a raging anti–German rally. The matter of his appearance passed from the farmer's market to the surrounding area, and spread throughout the masses like a legend.

I remember, that in a meeting with a group of Jewish Partisans, he spoke about the ability and the many possibilities to strike at the Germans. Out of contempt for German technology, he sought to prove that the Russian person with his rifle and his iron is able with his intelligence and his quickness to break the neck of the German tank crewman. His words were said without passion, briefly but spiritedly, in the Russian style and peppered with folk humor. This was a person who was kneaded with the best of the Russian Partisan tradition, who believed with all his heart that individuals are able to draw the masses after them for a national war against the invader. This was a meeting that sprouted wings for its listeners, for personalities like these influenced the formation of the combat and social atmosphere in the city.

Group by group, the Jewish Partisans began to go out for actions in the area. For reconnaissance actions, for economic actions, and for weapons searches. Slowly, the Jewish Partisans came to know the territory, the movement by day and by night. They learned to “smell” things; the farmer, his cunning, his way of life, and the things that were concealed from view: the enemy in ambush. And this was not an easy thing. Generally, they paid a high “price of learning” for this. And indeed, already in the first weeks of its existence, the unit paid the price. A Jewish group of Partisans went out on an economic action in the direction of Mogilno. On the way, a German ambush attacked them. A strong barrage of gunshots fired on them and the Partisan Plotk was killed by it on the spot. Plotk – from the Nesvizh ghetto, a refugee from Warsaw, an educated man, with the manner of a warrior, who had only just gotten to hold a weapon, was cut down in fulfilling his duty. He was the first victim of the Jewish unit.

The activity of the Jewish unit brought its people close to the local population and made it possible to get to know them. There were those among them who encouraged the Partisans, and those who related to them with hostility.

Those who were hostile to the Soviet regime and to the Partisans knew the secret of silencing, camouflage, and guile. They were more than a few. They were careful, especially when the Partisan authority, already at the end of the summer of 1942, was spread out over the entire region, and the garrison force and the police seemed like besiegers. (In the villages that were more distant from the base, the Partisans appeared on horseback or in a vehicle in the middle of the day.) The anti–Semites remained silent out of fear of the reach of the arm of the Jewish Partisans who on occasion carried out acts of retribution on their own initiative, for informing on or murdering Jews. (Actually, because the base of the Jewish Partisans was far from the towns of their origin, it was not possible at first to carry out acts of retribution in the area of these towns.) However, many among the population saw the Partisans as blood avengers in the full sense of the word. They willingly provided food and thirstily drank up the stories of their deeds, and anything that hinted at the descent of German power, even if on the front almost no turning point appeared, and only in the rear was much movement seen towards a great attack.

In the nights, by the light of burning logs, the eyes of old and young farmers sparkled to hear the words of the Partisans that were said with great self–confidence, and at times exaggerated. Yet the farmers too, more than one of them, would speak their hearts before Partisans.

On one of the nights my group and I were invited to the house of a farmer woman. She was an adult woman; her husband served in the Red Army, and she and her children were left in the house. She honored us with various foods, and her warm and maternal gaze. The time we spent in her house was comfortable for us. When we left, she pressed our hands with strength and with a blessing: “when will we finally be redeemed from the tyrant?” she said. And while her eyes were still sparkling with tears, on the days of the retreat of the Red Army: “On one of the nights I heard a knock on the door. I got up, opened it trembling, and before me stood a man of about 55, dressed in the clothing of peasant shepherds. He was tired, and his spirit was very depressed, and he asked for something to eat. I served him bread, butter, and milk. He ate, and his face expressed deep sorrow. His facial features were not the face of a regular person. He was not like one of “ours.” When he finished the meal, the man thanked me in clear Russian, and requested any kind of shoes. I gave him sandals made of tree bark. When he stood before me, entirely agitated before the parting, I asked him about his identity. In a strangled voice he said: “I am General Kulik. The army is besieged and stricken and I hope to break through the siege.” Tears flowed from his eyes, and I wept bitterly. “Woe, my dear ones! My doves!”

After some time, I visited with a few Belarusian Partisans in one of the distant villages. We entered one of the houses to dine. An old man and woman were in the house. The old woman prepared a warm dish for us and the old man who sat across from us next to the table, looked in the direction of the window and was silent. Not a thought emerged from his mouth. My Belarusian friend tried to get him to speak. He told him about the blows that the Partisans landed on the Germans, but the farmer continued in his silence. The Partisan did not give up and told about the preparations of the Red Army for the attack, on Stalin's last speech. Hearing this name aroused the old man, and in a sharp and stinging tone he commented: “This one who scattered our cannons and our weapons over all the fields of Belorussia?” And fell silent. In these ironic words of his, a heavy flinging of blame was heard, and the saturation of pain against the Russian government, which only in the rear, and even there only rarely, was the farmer able to voice it.

In the hearts of many farmers, strong bitterness welled up about the arrangements of the Soviet government, about the collective farms and the standard of living. They also revealed pleasant faces to the Germans, to share action with them, and to benefit from their new regime. However, after the slaughter of the Jews, the presence of the murdering face of Fascism was revealed also to the residents of the local population. Many began to await the day of liberation from the invader. And slowly, recognition began to grow in them, that more than that, they were a “secondary regime,” indeed that the Germans were interested in destruction and murder as much as was possible. The blows that Kapusta's units were landing on the enemy in the region, and their authority, which continued to grow stronger, helped with the inculcation of this recognition.

In those same days, the brigade camped in units. At the time of passing from forest to forest, the opportunity was given for the meeting of the units. The non–Jewish units bustled and revealed great joy of life. Many and diverse personalities from the different extremities of Russia were gathered within them. These happy and cheerful people played all kinds of musical instruments, especially harmonicas,

[Page 144]

while others went out in dances. In Doniev's unit, there was even a band of wind instruments. The meetings between the units and their people were brief, mostly during meetings of groups from various units on the roads. Occasionally, one would encounter groups of people with a level of idealism, whose main content in life in the forest was the battle with the invader. But in most instances, and increasingly as time passed, these meetings were with prisoners of war who absorbed the Nazi propaganda against Jews and added their own “contribution.” Only the organization and the discipline that prevailed in Kapusta's division constituted a barrier to the “whisperings of their hearts.”

The Jewish unit was transferred to Staritsa Forest, and adapted for itself the “lifestyle” of a Partisan unit. With the passage of time Belarusians from nearby villages and prisoners of war joined it. The number of Jews reached 50–60 people, and the Belarusians numbered 15–20. They, and also the Russians that came to the unit, did not feel themselves “at home.” For others it was different to be soldiers in a Jewish unit, and the matter was even displeasing. A few could not even hide that in their hearts, hatred welled up against Jews. But outwardly, they did not express this. However, more than one of the Jewish fighters sensed and knew that in due time it was likely to burst out and flood the Jews, but the Jews avoided poking the bear and taking him out of the forest.

In Action

Giltzik saw a possibility to carry out a number of actions at greater distances. In the month of October, I went out with a group for an action in the area of Lachovitz. Among its members was also Yaakov Geller, a former merchant in the villages of the regions of Kletzk and Lachovitz, who knew the roads, the farmers, and their property, well. A number of non–Jewish Partisans joined us. On the first night of the trip, the group succeeded in travelling a long way, and penetrated the region of Nesvizh. It attacked a German dairy plant, and destroyed it with devices. Everything that was seen as worth confiscating, was confiscated and loaded onto horse–drawn wagons that were taken from the farm, and at the end of the night, passed to a “jump base” – a small thicket in the same area.

In the afternoon hours, the group moved by way of the forest across Lachovitz and in the evening hours reached the village of Zubelevichi, which is about 3 kilometers from Lachovitz. The wagons were parked in the lanes of the village, and after a few conversations with the village's farmers it became known that a number of Germans were encamped in it. The Partisans began passing the suspected houses and it was revealed that there was a German in one of them. The house was surrounded. With a few people, I burst into the house. In the big room, in which only a few moments before the light had gone out, a German sat next to the table. I yelled “hands up!”[5] The German raised his hands. We took his pistol, his rifle, and all his military and personal equipment. The man sat tranquilly as if he was in his own house, inasmuch as the military garrison was 3 kilometers from him. He began to beg for his life, while pointing to a picture of his wife and children. Because of the great distance and the trouble of the journey, it was impossible to transport him to the camp, and it was necessary to kill him on the spot.

We stood Jewish Partisans, with glowing eyes, gripped with the tension of great emotion. Were it not for what had happened to us, which would forever prevent a feeling of joy, we would surely have named this experience with the name of joy. A first German! It seemed to us that we had achieved all that we were able to ask in those days: German blood – the revenge of Jewish Partisans. A number of bullets from a few barrels pierced his chest. The light was extinguished. We left the house and we travelled in the wagons to the arms of the embracing, protecting forest, as if into the entryway of a house. After a time, we heard in the distance a barrage of gunshots. It seems that the Germans were called to the village. On the next day the group camped in the village of Savichi [there are several places with this name], in the Partisan sector, and with sundown went out in the direction of Kletzk to search for arms. When the group neared the town, many flames were seen in it, as if a great conflagration had taken hold of the area. The farmers who had hidden weapons were very surprised by the visits of the Partisans under the noses of the Germans. They denied at first that they had weapons. However, after they sensed the threats of the Partisans, they agreed to turn them over. That same night, two rifles and ammunition were obtained, and information was acquired about additional hidden arms.

With a feeling of great satisfaction, the group returned to the camp.

In those same days a second group went out, and over it were appointed Shmuel Nissenbaum, Siyomka Farfel, Yosef Langerman, Bezrukov, and others, for a reconnaissance action in the area. In one of the villages, the reverberation of an orchestra was heard. A wedding in the village. To the questions of the Partisans, the farmers answered that police were in the village, but they left! A few Partisans entered a house, and the others surrounded it outside. In searches that they conducted, in a second house, they found rifles and a storehouse of “tens.” After an interrogation of the farmers, one of them admitted that indeed two policemen were hidden here, and he stated their names. After an inspection of the documents, the two policemen were revealed. Immediately a wagon was hitched and the two policemen were laid in it with their hands tied. On the road, one of the policemen attempted to flee, but he was shot by Siyomka Farfel and Shmuel Nisenbaum. The second policeman was brought to the camp. He was turned over to the adult Jews in the camp. They killed him with knives.

The events of the days, the organization of the unit, the frequent actions, meetings with the Partisans, the desire to be freed from the experiences of the previous day, slightly distracted the hearts from the nightmare that weighed. Each person was turned towards their friend. Acquaintance and friendship grew. Young intellectuals became friends with Vastotznik youths. Slowly, a Partisan way of life began to develop. The conversation aroused, the joke elevated, and even song was lifted in the base, especially in the evenings next to the campfire. The song at the campfire was a faithful companion to the forest fighter, especially the song of the Partisan.

I remember – the first twilights of the wonderful Belarusian days of fall. On those same days of evening before the sunset, I used to walk alone to the brigade headquarters to receive the “broadcast news.” A treasure of colors in the trees of the forest and all around living nature, amazingly beautiful and moving. Even though the heart was signed and sealed to the majesty of nature, nevertheless “something” clung in the heart. When I emerged from the headquarters' tent, there still flickered between the branches of the trees the last shining of the ebbing day. Suddenly, there erupted from one of the concealed tents, the pleasant sound of a young woman singing. This was a new Partisan song. I stopped and listened. The song told about the Partisans whose homeland sent them into battle, of the warm parting from wife and home, of the waving of a kerchief at the station, of battles and revenge on a letter to a house full of hope for a meeting after the war, of the tear of the woman that purifies the letter.

I stood stuck to the place; my feet did not listen to me. Can you know what it will mean to the heart of a person who is orphaned and alone to hear a song like this? Over a few days the song reverberated, and people sang it with devotion, as if they were praying a pure prayer. The song found the fullness of its expression in the powerful cantorial voice of Motke Kvadiuk that erupted in the forest. “Lend an ear” companies [in Russian, then translated into Hebrew]! This was the first of the Partisan songs in the forest. The song conquered people's hearts, its originality and passion stood it in good stead over the course of all the periods in the forest.

Within a short time, the people in the forest “became citizens” and quickly adapted for themselves a special way of life for the conditions in the forest. The sufferings of the forest did not burden them, since they knew to appreciate the fullness of the obligation of their Jewish fighting reality. Certainly, the fact that most of the people were young worked well. But also old people who arrived from Kopyl and a few elders integrated well in the economic system of the unit, and were elements who “carried themselves,” and did not constitute a “problem” in “days of peace,” whereas in moments of siege and surprise attack, they were likely to be a problem.

There were also a few children in the unit: Shraga Filler, 10 years old, and Tzila Neimark, 12 years old. They were the friends of all the fighters in the company, and achieved a warm relationship and heartfelt care of the fighters, first and foremost of

[Page 145]

the Jewish girls. They appeared in all of our eyes as the last remnant of the Jewish child. Their childhood disappeared quickly. Shraga Filler became an excellent scout, and Tzila acquired the life wisdom of an adult.

Much importance was attributed to the fact of the unit being Jewish, that Jews were its founders, its fighters, and armed it. It was that which created for its members a feeling of home, and the joining of these Belarusians and non–Jewish prisoners of war, among them a number of officers, did not overshadow this feeling at all, since the Jewish manner of the unit was clear also to these non–Jews. It is worth noting the attitude of respect and appreciation for the founders of the Jewish unit, from the perspective of all those who arrived during the two years of its existence.

Discipline prevailed in the unit, but the relationships and the tapestry of daily life formed the fighters themselves. It is especially appropriate to note the pleasant and friendly relationships among the youth of the unit. Even food did not become a problem. Relative to the conditions in the forest, the food was good, compared with the “nutrition” that they remembered from the ghettos. Bread was given freely, and there was even enough meat and potatoes for everyone. But the regime in the kitchen was generally proper. This institution that was called a kitchen reflected to a great measure the level of the unit. The food was distributed equally to each of them, to soldier and to officer, to the veteran and the recently–arrived. Only the sick merited special, better, nutrition. And if injustice was caused to someone, this was a result of human error, and it did not find its echo among the people in the unit. The Jews from the Soviet region also contributed to the equal distribution of the food and the proper relations of the kitchen, especially the youths among them. Discrimination or injustice, when it appeared, was not tolerated. The opinion of the community did not tolerate this and was obligated to correct it. With the growing of the unit to over 100 people, approximately, it was organized on the Partisan structure. The commanders of the companies were: Bezrukov, Bilosov (Soviets). The commanders of the divisions were: Sholom Cholavsky, Simcha Rozin, Miknovsky, Smukler. Chief of Staff: Berkovitz. Deputy Commander for Economic Affairs: Michael Fish. The Political Commissar:[6] Viener, a party man. Among the offices of the squads were Jews and Russians. In the Scout Division: Mishka Neimark, Chanan Va. Giltzik made many efforts, among them successful ones, for arming those who joined the unit. With this, the relationship of the authority of the brigade to the Jewish unit was not fixed even then. But the man who decided the authority, Kapusta, revealed open affection to the people of the unit and the command, encouraging and assisting its development more than a little.

Ties

In that period, the reserves of the unit were primarily in Belarusians and Russians. From time to time, a solitary Jewish refugee, male or female, reached the unit, after protracted wandering on the roads, or after they had hidden themselves in hideouts in the cities and towns. In that area, there were no longer Jews left, except in Stolpce, the Sverzhna camp, and Baranovitz. Gloomy and vague news arrived about Baranovitz, because it was far off, but it was known that in Stolpce and Sverzhna, Jews still lived. We were convinced that if reliable news reached them from a Jewish source, about the Partisans and the place of their encampment, and especially if they knew about the existence of a Jewish unit, they would not tarry for even a minute. All of this information was absent for the people of the unit, when they were inside the ghettos.

In September 1942 I met together with Siyomka Farfel for a conversation with Viener on the matter of bringing Jews from Stolpce and Sverzhna out to the unit. Viener, whose Judaism was a test of God, was very attentive to every Jewish matter. More than a little, he surely influenced Jewish fate in those days; as a party man, he came into close contact with the command of the Division Headquarters. I placed before him the task of bringing the Jews from the ghetto to the forest as a high purpose of the Jewish Partisans. Viener agreed with our words and considered the relationship of the command to the matter. In this meeting, it was decided that first of all, ties needed to be formed with the Jews of Stolpce by means of dispatching letters to the youth. We assumed that the people of Stolpce would certainly correspond with Sverzhna, which was only 4 kilometers from it. We wrote two letters; I wrote one, and the other – Siyomka Farfel. Siyomka had many acquaintances his age within the youth movement who he met in regional meetings and in meetings of the Young Guard. This was the language of the letters:

“Dear Brothers!Yisraelik… the word of Eshka Maza, Azriel Tunik, we alone were left from cities. The murderous fascism lifted its bloody sword first of all against the Jews… (You need) to be the pioneer of the youth. Be ready in groups, there are two tasks for every person: Revenge and victory! Don't give (abandon) your lives for a price so cheap as those who fell until now. Here I swear you to go on the path that I… (point out) to you: on the path of fighting and honor. Fascism is collapsing and will be defeated by our hands. The Partisan movement is a tremendous power that is growing stronger from day to day. (You) are shut up inside and don't know about it. Don't delay, (lest) you will be late. Let your spirit not fall. Lift your heads. The Soviet Union strikes the enemy on the front. We – the Partisan movement – behind the front. The enemy will be struck to the last of its soldiers. Your obligation is to be among the fighters. Get ready and do it. Of course, carefully, yet with vigor, according to what you alone are able to do.

The only way!

Remember –

Sholom CholavskyP.S. Transmit this to faithful friends among you, if they are alive, Chaim Saragovitz and Novodvorski, Zokovska (the teacher), Yoselevitz (the father of Avner Aminadav and to the rest of the acquaintances).”

On the matter of weapons: We prepared all the weapons that were possible to obtain: grenades, rifles, pistols, bullets, everything is important.

Go the region of Kopyl, our place is there.

Siyomka Farfel's letter:

Dear Lads,Sholom (the intention is to Sholom Cholavsky) writes to you detailing everything. I want to add a number of words. Time will make your situation more serious. We have organized ourselves – as much as possible. Your young lives are precious, and God forbid they should be cut off. Prepare weapons – for that is the essential thing – this will save you and your lives are worthy of even the greatest expenditures. The time is short. Be ready… to us…for the lives of the Partisans. Don't pay attention to the old generation. With your deaths – you will not save them. I speak from experience. Prepare and organize the best of the youth for Partisan lives. Fascism is collapsing. It is expending its last strength. The time of its rule is short. Victory is on our side. Go to those who are helping those who are right and hastening their victory. Don't give up your lives in vain. I speak to you heart to heart.

Our past was shared. Let our future also be one.

Remember my words –

Your friend: Siyomka Farfel

The letters were passed by way of a liaison to the Stolpce ghetto.

Meanwhile, another thing happened in the unit, that awoke them all. Still in the forest of Veleshin, a woman, a Russian, was stopped by the patrol. She said that she wanted to be accepted by a Partisan unit. She was brought, according to the instruction from headquarters, to the headquarters, and there it was decided to accept her to our Jewish unit. She was a woman younger than the age of 30, beautiful, a typical Russian woman, and educated. Her name was Mirusia. Before the war, she served in the army as a military technician. According to her words, she fled from Minsk and succeed in reaching the Partisan sector. She was a very good singer, revealed a social inclination, and was especially inclined to become friends with the Jews. Occasionally she would ride a horse, within the area of the forest, for her enjoyment.

After a short time, the Brigade command sent Mirusia to Minsk,

[Page 146]

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

Siyomka Farfel's letter to his friend in the Stolpce ghetto |

Sholom Cholavsky's letter of to his friend in the Stolpce ghetto |

[Page 147]

after she claimed that she could bring weapons from there. She brought, upon her return to the forest, a machine gun, but the barrel was bent. At headquarters, the suspicion was aroused as to how could she bring a machine gun from such a far distance. They asked her at the headquarters: How did you not notice that the barrel was bent, aren't you a military technician? She answered: I didn't notice, I am ready to go a second time. She requested food for her journey. In exchange – she claimed – she would obtain weapons. When she went out on her way for the second time, a few Partisans from another unit dressed in police clothing and accompanied her on her way. At the edge of the forest the “Police” stopped her and asked her “Who are you? Where are you going?” She answered, “I am going to the next village.” The “Policemen” gave her a few blows. “You are certainly a Partisan.” She sensed the seriousness of the situation and took out of the hem of her garment a hidden certificate sewn in the fold, which testified that she was working in the Gestapo. The “Policemen” ordered her to return to the forest to fulfill her duty. After they freed her, they followed her on the way back to the forest. When she reached headquarters, the marks of the blows were on her face. They asked her: “What happened to you Mirusia?” She burst into tears: “The bandit policemen caught me and beat me.”

That same night she was interrogated. Her screams were heard far away. She told everything about her service in the Gestapo. On the first time that she went to Minsk, she transmitted details about the Partisan force, about weapons and the location of the camp. In short, highest level service to the enemy. The next day, she was brought bandaged to the camp of the Jewish unit. The people passed by her and spit in her face.

I remembered that same day of her arrival in the forest. I reached the patrol in order to transport her to the headquarters. She sat on a fallen tree trunk at a distance of a few meters. At the edge of the forest, a group of Donievite people parted from their friends and from the command personnel. On this group was placed the difficult duty of reaching the passage to the front on foot in order to fulfill important tasks. One after another, fighters from the group that were going got up on a wagon that stood next to the Partisan unit that was remaining, and emotionally gave enthusiastic speeches, imbued with much pathos, and after this hugging and kissing among the fighters. We stood with the people of the patrol and tensely watched the exciting sight. For a minute I glanced at the face of the “visitor” who sat on the fallen trunk. Her face was opaque, without expression. The thing aroused wonder in me. I asked her about her sorrow. She answered that she was tired from the journey.

Now. When she sat bound in the camp, it was clear that with all “her success,” she played her role badly. The same day, an organizer was established for the entire brigade. Shtopblov, standing in for the Brigade Commander, read the letter of guilt. The traitor stood in the middle of the yard. The Brigade Commissar shot one bullet from his pistol into her head. This event was an informative lesson that contributed much to the fighters, to their Partisan maturity.

The People of Stolpce

Individuals continued to come to the forest: Henka and Ninka, Sonya the Minskite, Sonya from Kopyl, solitary Jews that were lost. Most of those who came were not Jewish. On one of the days, the camp received word of the arrival of a Jewish group from Stolpce, that numbered upwards of 20 people.

This was encouraging news. The Jewish family was growing. Jealously, the Jewish fighters up to this point saw the size of the unit and the limited arrival of Jews. The group was made up of young men, with a number of young women among them. In the group were: Yosef Harkavy, Akselrod, Shmuel Leib Oginski, Shlomkeh, Azriel Tunik, Moshele Veinstein, Moshele Esterkind, Kuba Altman, Ozer Maza, Eliyahu Engleman, Chava Tunik, Tzila, Leizer Zaretzky, Eliezer Melamed, Yulik Pinchevsky, Posesorsky, Bernstein, Reich.

They were very excited on their arrival at the camp of a fighting Jewish unit. In conversations with them, the history of the unit was made known to them. Actually, there were two groups included in it – the Harkavy group and the Posesorsky group, who left the ghettos on separate paths, and not even on the same day, and in their search for Partisans they met and arrived together.

The Harkavy group was made up of people from HaShomer Hatzair, amongst them Harkavy himself, a number of people from Betar, and the rest of the members who mostly received their education from Hebrew school and youth movements. Harkavy, after he lost his family in the ghetto, devoted himself entirely to the organization of the underground. His honesty and his conscience acquired a central position for him in the organization. On one of the early fall evenings of 1942, 19 people gathered with Harkavy at the head, and Oginski as the guide. There were 5 rifles in their possession. They slipped away from the ghetto, cut the wire, and went out in the direction of the Kopyl forests.

Posesorsky decided, with the beginning of the second slaughter, to go out with his group to the forest. He worked in the area of the train. He expected the danger of being sent, with the beginning of the slaughter, to work in Germany. In order to foil this plan, he accelerated the exit to the forest.

On the second day of the slaughter, when the approach to the ghetto and the hidden arms in it was blocked, he entered in the noon hour – when the Germans were dining – into the rooms where the Germans worked, took out 4 pistols, dropped them into his pants, and left. The action was done with great haste, in order that the Germans would not notice the absence of the weapons. Another 5 members went out with him, and they turned in the direction of the forest. When the Germans realized what had been done, they sent a small group of Belarusian policemen to pursue the group. One of the members of the group, Feyga, fell killed on the way. The rest headed east. Melamed and Pentzovsky, members of the group that split up at the time of the escape, since they didn't have weapons, returned to Stolpce and went out with Harkavy's group. On the way a bullet from Posesorsky's rifle was discharged and wounded his leg. This fact weighed down the advance to the Partisan sector.

These two groups wandered in the forest until they met by chance in one of the houses. After the exciting meeting, they continued on their way together to the area of Kopyl. When they arrived at Mogilno, they met two Partisans from Kapusta's division. These transported them to Pesochnoe, to the “Partisan regime” in the place. The “Partisan Commandant” listed them, permitted them to eat in the town's houses, but after that he ordered them to turn their weapons over to him, temporarily, until after the meeting with the people of the command. Two partisans were ordered to transport them to the headquarters, but they disappeared on the way. This act of deception caused the people of the group deep disappointment, and injury to the idealistic image of the Partisan that they described to themselves. In addition to their pain came a meeting with two other Partisans, who, instead of transporting them to headquarters, began to ride on the “Jewish horse” and to hurl complaints and reproaches at them: why don't the Jews want to work, but pushed their way into offices, that the Jews are a nation of “pencil pushers”. From their words it was hinted that the punishment that was coming to the Jews from the Germans was justified. In Baranovitz, they claimed, the Jews ate white bread in the ghetto, while the prisoners of war starved, and the Minsk Gestapo sent a Jewish woman spy to the forest, but the Partisans caught her and killed her.

This “welcome” tainted their spirit, which was depressed anyway. Finally, they succeeded in informing Giltzik of their arrival, by means of Russian Partisans. Giltzik arrived and transferred them to the Jewish unit.

It became clear that the weapons thieves were Domenko[7] people. In order to justify this act of theirs, they falsely accused that the men of the group acted without restraint and shot geese. The weapons were returned with Giltzik's intervention, but instead of 3 German pistols, 3 rifles were returned. The Yerminko people were not the only ones who had this practice. Moscow at that time had still not sent weapons and ammunition. The acquisition of weapons was at times enormously difficult. It was easier to carry out “the action” by attacking Jews that went to the forest with weapons, to kill them and appear with the “acquisition” in the unit when fabrications covered their crimes. This is what Partisans from various units did.

[Page 148]

The coming of Jews to the unit was an encouraging, invigorating, fact: more Jewish fighters, more Jews saved! By the campfire, the “kostiur,” the people of the group told stories about the ghetto, the underground, exit and wandering. Most spoke much about the wandering. On their way, there happened to some of them an unusual meeting that left a very strong impression on them: “When we entered the house, the cleanliness that prevailed in it drew our attention. The air was clear, and a pleasantness was felt that was not found in the regular Belarusian house. When we asked for something to drink, the mistress of the house indicated to us a bucket of boiling water. We were invited to dine for the evening meal, the master of the house, the mistress, and their ten–year–old son sat at the table with us. We were amazed and impressed with the nobility that prevailed in this house. There was something different here than everywhere else. They didn't give us a meal to eat that one gives to unfortunate people, who arouse compassion in the hearts of those who see them, rather they treated us in the way of welcoming important guests who cause pleasure and honor to their hosts. When we asked them if they weren't afraid that we were found in their house, the master of the house answered that he was afraid of only God. And he sprinkled words of encouragement on us, that we should not despair. ‘Hitler will not destroy you’ he said, ‘because you are eternal, and Israel is immortal. God is only punishing you for your sins and testing your faithfulness and steadfastness.’ When we asked them if our sins are greater than the sins of the nations, he answered us emphatically: ‘No, your sins are less than theirs. You are God's beloved children, his chosen people, and for that he is punishing you. God chose you in order to purify the world from evil, and to bring redemption to humanity.’ He said all this with innocent simplicity, and with faith so deep that there was no room left for doubt. It was known to us from his mouth that he was a smith, and all his family – were faithful Baptists. At the end of the meal, we moved to the second room. The mistress of the house was busy increasing the light with logs in the stove. And he, the master of the house, read to us from some book on the certification of the people of Israel, on the suffering, with which God tests His people. On the history of his long wandering and on the great mission that was placed on this people in the future as the head of all the nations etc. etc. I did not try to deeply analyze the content of the words. But I listened more to how a pleasant and warm voice was speaking to us, the scattered, the humiliated, with deep faith, with full and convincing seriousness as on a redeemed nation. For on these for whom all was created, the chosen people and the precious ones of God… We sat enchanted and our eyes blazed.

The man who was reading was 30 years old, his eyes – eyes of pale blue, and his face, a combination of noble spirit and rural resilience. When we left the house, it was already the midnight hour. There was not among the three of us even one believer, but we were all agitated, encouraged, and inflamed, and we trudged on our way in the dark night, the fall night, to the great patch of forest on the horizon, which was our home. There we lay down on the wet ground, elbow to elbow.”

I paid attention to the absorption of the new members of the group. In conversations next to the campfire I talked with them at length, individually or in a group. During conversation, the personality of each one of them arose, their origins, their past, their views, and their education. I told them what they were interested to hear, about the history of the unit, about the days of its founding.

With Harkavy, who was revealed before me as a fighting man, conscientious and with vast Jewish roots, and with his friends, there were also brought up, among other things, memories from the distant past, about mutual acquaintances, about the movement before the war, on movement activity in the underground. The land of Israel was integrated into these conversations as a distant background, not real for us, lost – but existing and steady somewhere in the world, as magic, as a legend, illuminating and warming. We saw it as a fortress which this terror could not reach. It was good for us that at least it was found outside the danger zone. How happy was the one of us who had a relative there – a shoot of the trunk of a tree that was cut down, that would continue the thread of life, that would remember and remind.

We could not, by any means whatsoever, accept that it was not possible “in that world” to act on our behalf then, when there were still Jews in the ghettos. Was it possible in this century to close a continent with this kind of blockade without hearing the voice of a slaughtered people? Is it possible that they, “there,” were so powerless?

During conversation, the names of personages and movements from the Jewish and Zionist world were raised. That their response was strange within these forests, and it seemed very far, even for the time. Within conversation, fragments of song and Hebrew and Yiddish poems were sometimes woven together.

In conversations with Posesorsky, I recognized in him a person with a gentle soul, ruled by spirit, and with ability in planning. Even though before the war, he was far from national–Jewish life. He expressed before me the fullness of the national lesson that he learned in these days, and the great similarity of our views. In our speaking about the Jews of the ghettos, he told me of the possibility of reaching the Sverzhna camp. His sister, his brother, and his brother–in–law were in this camp. I encouraged him in this idea. We spoke about how to take action and how to raise the problem before the command. I raised before him the names of contacts, who would be useful on the way, and I kept the matter in my heart. Throughout the whole camp there was hidden combat willingness.

The actions increased and even their dimensions expanded. Sometimes actions also took place in partnership with other units. In October 1942, 30 people from the Jewish unit went out with a group of Doniev's people to destroy the police station in Doktorovitz. Some of the people from Stolpce also participated in this action. At its head stood Doniev. He described the mission in short words. Doktorovitz was the police station that was stuck like a wedge in the Partisan sector. Doniev assembled the fighters near the village and said a few words: “You are becoming soldiers in an action. Pay attention! It is upon you to act as quick as lightening! It is upon you to attack the enemy in a storm and destroy it. One thing I will ask of you: don't get involved with “borochlu” (borochlu: objects, clothing). If you need, I will send you especially for that, but not now….” The division quickly surrounded the village and prepared for the battle, but it suffered a cruel defeat: most of the policemen fled before the battle began. The rest of the policemen were shot, and two were taken prisoner. The station was sent up in flames. After this the fighters prepared to “distribute” the policemen's houses. Clothing, boots, and foodstuffs were taken.

The unit grew. Belarusians began to stream to it, Ukrainian Russians that fled captivity. And the Jews? In those days, Zaretzky went out (the Zaretzky family was very active in the organization of the underground and in acquiring arms in the area of Stolpce), a youth of about 17, from the forest to the Stolpce ghetto, on a mission to bring Jews. He reached the ghetto and met, by chance, with people who were not from the underground, who firmly opposed exiting to the forest. They forbade him from coming in contact with the rest, and took him outside of the ghetto. Next to the wire fence, he was caught by Belarusian policemen and taken out to be killed. A pure innocent on a great mission fell victim. Those that he also intended to save sacrificed him!

The information from the front resembled a tune on a broken record, repeating the same tune every day. And the tune was, approximately: “the enemy stands at the gates of the Caucusus. There is no news from the rest of the fronts. A division of the enemy was destroyed. A number of tanks were destroyed.” Who knows how many years all of this was likely to be continued? It was clear that the Red Army and the invader were intending a tremendous competition at some stage. When would it be? What would be its outcome? If the enemy would cross the Volga and break through to Orel, and from there with two arms advance both north and south, would it reach the Caspian Sea and surround Moscow from the east? In the heart there beat a mighty wish, even a feeling and some certainty that the Russians would finally be victorious. But when would this “finally” be? These questions gnawed and chewed at the heart of the individual fighter, and the Partisan unit was 800 kilometers from the enemy's rear. The end of the war was not visible on the horizon, and in the life of the forest the end lay in wait for the fighter every day.

[Page 149]

On one of the days, I served as officer on duty in the unit. At night, I went out to visit the guards. When I approached the observation post I was not stopped by the guard. I feared in my heart that maybe he fell asleep. When I reached a distance of a few steps, he stopped me. I asked him: “what's with you Chanan, you fell asleep?” Chanan was a young man from Kopyl. Brave, responsible, one of the best scouts in the group. “I didn't fall asleep” he answered a little confused, but I was contemplating.” A conversation developed and he said what he had previously been contemplating while alone: “see, the end of the war is still not seen, maybe it is only now beginning. A tank here, a tank there, the business is only beginning. And we, our lives here are dependent on opposing, every day, every minute. Only a few days ago, I went up against a German ambush with Mishka Neimark, as scouts for the unit. It was only a step between us and death. I don't know how we emerged whole from within this gunfire. How many times can miracles occur? Once, twice, ten…? The bullets also strike people. Finally, it will finish in one of the days or nights. And the end – to fall somewhere alone as a dog in the field or the forest, and no one would even know the place of burial.” He finished his words with trembling that passed through every limb of his body.

This was the essence of his soul's contemplation, but not only his and not only that same night.

The Battles of Staritsa and Lavy

In preparation for winter, energetic preparations began. The elders, the women, and the children were transferred to another camp at a distance of a few kilometers, and only the fighters remained in the camp.

They began to build huts, dug pits for potatoes, grains, and fats. Straw, and hay for the horses and cattle and the like, were properly camouflaged, so that the base would serve as a basis for existence during the approaching winter.

Leading up to the 25th anniversary of the October Revolution, great preparation was felt. Captain Rabuz, Chief of Staff of the battalion, supervised the preparations. The commanders trained the fighters for the march. A stage was set up in a forest clearing, and two bands of the battalion were prepared, brandy and a rich dessert for the feast. With the light of morning on the day of the festival, the Partisans began to prepare themselves in advance of the march. The enthusiastic and quick “October Devout” were early to do the mitzvot, and before “prayer” they were already inebriated, and created an amusing festive atmosphere. But all the joy was stopped in a minute; from the adjacent village a runner arrived, with the information in his mouth: the Germans are coming! Germans by the thousands, flooding the area villages with tanks and cannons. In the blink of an eye, the face of the camp was changed. The battalion with all its units went out to the edges of the forest, which was not too big, on all sides, to guard the roads. The wagons were quickly loaded and were taken out of “our” area of the forest to the large forests and the area of the swamps, which were not a far distance from Staritsa Forest. But in the loaded convoy's emergence to its way, it encountered great German force, which surrounded it with strong fire. Part of it fell into the hands of the Germans, and part was returned to the forest. Moshele Veinstein, who was severely wounded in this action, was brought to the camp.

The Germans intended to surround the forest, and as long as they had not carried out this mission, they attempted to reveal themselves and their firepower.

When the forest was surrounded, in the afternoon, the Germans opened an assault within fierce battles, but they were repelled. In these battles, the enemy felt the Partisans' firepower, but did not yet discover its full power. It seemed that their plan was to open with the full attack in the morning.

The battalion command aimed to prevent the enemy from penetrating into the forest, to hold on until evening, and with darkness to send the scouting units to find a way to retreat from the surrounded forest. The Partisans repelled the enemy attacks, but in particular, overpowered the pressure in Doniev's sector.

With darkness, after frantic activity by the scouts, the fighters were taken down from their posts and were brought into the area of the camp. Carefully and quietly the unit began to move towards a narrow area of boggy swamp, which was not held by the Germans. It was clear that this narrow “no man's land” was also within German firing range. At night, the enemy sees with its ears, and one needs to be on guard for the rustling of leaves or breaking of branches. At first, Bilosov's company went, and after it, Giltzik's company. For the need of camouflage and quiet, the companies had to go deep into the thick forests, which were called the Warobida Forests, and to meet up there at a place that had been set ahead of time. Bilosov,[8] according to what was told by the Jewish Partisans of his company, intentionally wandered far. In these wanderings, which lasted 5-6 days, Bilosov revealed his typical anti-Semitic and “humane” face. The people made their way in the swamps trembling with cold, and hungry, and lacking everything. He did not worry about making the suffering even a little easier for them. Even though in the area there were many potatoes, he did not let them collect them in order to feed the men. He sent non-Jews to accumulate food, and they were concerned first of all for the gentiles that were in the company. For the “transgression” of confiscating clothing of some kind by two Jewish fighters from a farmer's house, he decreed that they be disarmed.

With the arrival of the order for the concentration of the unit in the Lavy Forest, the place where Kapusta's entire battalion was, Bilosov began an escape with surprise walks and devious punishments to repent and to cover up his behavior. The fighters remembered his deeds, and for a long time he was disgraced. In a meeting of the unit, the process of the battle was investigated. It was made clear that the Germans who went out to Staritsa with arrogance returned with angry faces. The entire battalion escaped from the forest and left the Germans after them to fight “bravely” with… the trees. In addition to that, Doniev's unit set up a big ambush for the Germans who went out sure that they would “destroy once and for all” the Partisan affliction and harvest a blessed harvest. In this ambush 5 Partisans also fell, Doniev among them. Doniev's death induce heavy mourning in all the units.

The battalion camped in the Lavy Forest, and the Jewish unit, in considering the women and children, resided in Yevitsha, a village that was in the Lavy Forest. After the “March of the Revolution” in the cold and hunger of the month of November, the Partisans merited a few weeks to reside in the warm houses of the farmers, with enough food, and relief of their tired bones. These were the most comfortable weeks – in the sense of living conditions – in the history of the unit. Over the course of the Partisan's time in the village, they made good connections with the farmers. The farmers only provided the food – the cooking and the seasonings that the housewives added created food that tasted like home cooking, which had already been forgotten long ago. The actions of the unit were limited.

The great and most gladdening news of all the days of the war arrived in Yevitsha: that it was proved in the course of time as a subduing turning point at the front. Indeed, even before the enemy armies were crushed, only the siege was completed and the ring of steel of the Red Army began to be tightened around the defeated and besieged enemy. However, everyone sensed that the great turning point had begun, and that the one carrying it out, who had prepared for it a long time, had succeeded, and from now fate would strike the Germans without mercy.

The good feelings of the Partisans, because of really being “at home” and the warning news that excited all of them, inspired encouragement and confidence in victory in the campaign, and the days of the unit's stay in Yevitsha granted it a feeling of home and joy.

To increase the joy a group of Jews from Baranovitz, about 12 people (among them the three Vaks sisters, and Tunik with his two sons), arrived in Yevitsha, with Vishnir Vallace at their head. They were warmly welcomed in the farmers' houses in which the Jewish fighters were living. Their appearance spread hopes, if only faint ones, about additional Jews who might in the future reach the unit.

On one of the late days of December, the fighters were called: “large armed units of the enemy attacked the battalion on the other side of the village of Lavy.” The battalion quickly got on its feet. The best of the battle regiments was enlisted to land a blow on the enemy that dared to burst into the forest.

With dawn, the time that the enemy forces spread out in the direction of Lavy from the side of the cemetery, in order to attack the Partisan battalion by surprise, there sat

[Page 150]