|

|

[Page 3]

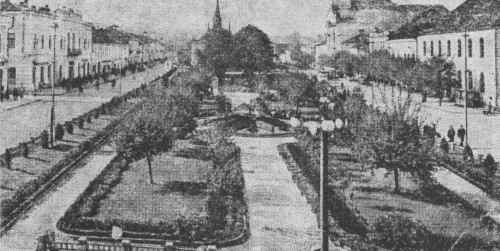

(Sighetu Marmaţiei, Romania)

47°56' 23°53'

Hungarian: Máramaros-szighet

Romanian: Sighetu Marmaţiei

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Edited by Yocheved Klausner

|

|

Sziget (in Romanian: Sighetul Marmatiei, in Hungarian: Sziget Máramaros: in Hebrew sources: Siget, Sigut, Sigit, Sihet).

Sziget, the capital of the region, is located on the confluence of the Tisza and Iza rivers, in a hilly area surrounded by high mountains. Until the Second World War and for a few years thereafter, it was the seat of the offices of the regional and provincial government. The city is quite ancient. Already in the year 1352, it was recognized as a crown city by the Hungarian King Louis the Great (Nagy Lajos).

The primary business and manufacturing enterprises were as follows: large sawmills that processed the wood that arrived on barges, a furniture factory, a brick kiln, a salt mill, iron foundries, mechanical enterprises, an oven factory, and an iron rolling enterprise. It was one of the prime centers for the forestry industry. It was also a center for the sale of salt from the mines of the region. Several banks and financial institutions served the economic enterprises of the city.

In 1850, the city only had 6,336 residents. In 1881 – 10,852, in 1910 – 21,370, and in 1920 it had 23,691 residents (4,964 Romanians, 6,552 Hungarians, 149 Germans, 1,000 Ruthenians and others, 11,026 Jews.)

| Year | Number | % of Jews |

| 1746 | 49 | |

| 1785 | 142 | |

| 1830 | 431 | |

| 1869 | 2,325 | |

| 1880 | 3,653 | 26.3 |

| 1890 | 4,960 | 30.0 |

| 1900 | 6,375 | 36.5 |

| 1910 | 7,981 | 37.4 |

| 1920 | 11,026 | 46.5 |

| 1930 | 11,075 | 40.0 |

| 1941 | 10,144 | 29.1 |

Table of Contents

The Beginning of the Jewish Settlement

The Beginning of the Jewish Settlement Torah Life A. Rabbis B. Rabbinical Judges and Preachers C. Hassidim and Admorim D. Authors Who Did Not Serve as Rabbis E. Scholars Mentioned in Responsa Books

According to tradition, Jews lived in Sziget already from

[Page 4]

1640. A few years later, more Jews came from Poland and Ukraine refugees of the pogroms of 1648/1649[[1]]. The first document that we know about that mentions Jews is from 1690, in which the residents of the region of Máramaros demand the expulsion of Jews “who cause many troubles” to the population. In 1691, the residents of Máramaros discuss once again the expulsion of Jews. The Jews were not expelled, but were greatly restricted in business. In 1718, the governor of the region forbade the Jews, under the threat of expulsion, to distill liquor. The ban was repeated in the year 1726, but they were permitted to lease the collecting of taxes and the sale of liquor in taverns on the condition that the fees not exceed one florin per person. The Jews of Sziget were also permitted to lend money to farmers for interest of 6%.

From their side, the Jews of Sziget always fought to improve their economic situation and judicial status. In 1750, an official complaint was submitted to the Hungarian government regarding their bitter lot. In it, they complain that the residents attack them, pillage them, and even threaten their lives. Among other things, the Jews complained about the ban on distillation of liquor issued by the regional government – upon which their prime source of livelihood was based. They complained that there was insufficient wheat in the area. If this were indeed true, they were prepared to bring it from other provinces of Hungary where it was found in greater abundance. The Jews claimed that they paid the many taxes and fees imposed upon them with exactitude and requested the protection of the central government against their neighbors.

Business connections between the Jews of Sziget and the Jews of Poland and Galicia were quite vibrant and well developed. A document from 1705 mentions a Jew from Poland (“a Jew of Count Potocki”) who expresses his willingness to supply steel for the manufacture of weapons for the Hungarian army if provided with the appropriate permit. In 1708, the regional government recommends sending a Jew from Sziget to Poland to purchase 300 pairs of a unique type of boot, for the local shoemakers cannot make that type. In 1728, two Jews from Poland were robbed on the border with Máramaros, at a pass through the Carpathians. From the list of pillaged goods, we can learn something about the variety and nature of the business dealings: 1,300 sheepskins, 20 wolf hides, 20 marten hides, 15 pounds of silk, 15 pounds of cotton, 20 cubits of cloth, 23 varieties of fabric, haberdashery and incense. The two Jews labored for two years through various guarantors until the Transylvanian principality commanded the authorities to pay damages to the victims.

In the year 1762, the regional governor sent the Jewish tailor Yoel to the city of Hotin in Bessarabia on a security mission. He was to investigate the movements of the army on the borders of the country. His findings were written in the “Jewish language” (that is Hebrew or Yiddish) and translated into Hungarian. This and other such facts tell us that, despite the oppression that the Jews of Sziget faced, faith was placed in them and their abilities were utilized for the benefit of the country.

The first Jews of Sziget included some who adhered to Sabbatean[[2]] ideas. Later, some Jews of the city joined the cult of Jacob Frank. The “Red Letter” written by Jacob Frank to a Jew by the name of “Moshe Siheter” (that is, from Sziget) is preserved. In 1767, three Jews of Sziget who adhered to the Frankist movement, including Moshe the son of Yisrael Srulovitch (apparently the aforementioned Moshe Siheter) asked the local priest to bring them into the Catholic faith. There is a tradition among the Jews of Sziget that all three of them recanted and that some honorable people of the city are among their descendents.

In the census of 1830, the heads of the families in Sziget were listed as follows (number of people of the family in parentheses):[[3]]

Chaim Lazer Sabo (6), Yoel Leib (8), David Lachs (3), Izak Lefler (4), Yirmiyahu Kopel (4), Leib Solomon (4), Michel Sabo (2), Aharon Gumbekata (6), Yosef Szamok (4), Tilda Kaufman (7), Atvash Solomon (5), Berku Solomon (5), Lazer Braunstein (5), Elias Berkovitch (2), A. Spritzer (4), Shmuel Sabo (2), Chana Ferber (3), Shlomo Berkovitch (3), Efraim Stein (2), Zelig Steingisser (4), Meir Steiner (4), Ilana Berkovitch (3), Yaakov Fish (5), Aizik Kahana (6), Mendel Wieder (4), Lazer Shimanovitch (4), Yosef Weiner (3), Leib Soponias (3), Avraham Wallerstein (5), Aizik Lempert (5), widow of Aharon Kahana (5), Matias Lempert (9), Meir Hersch (6), Meir Ilesh (5), Lorbert Farkas (3), Chaim Green (3), Meir Gersh (8), Shmuel Katz (3), Leib Szamok (4), Yoel Szamok (7), Leib Katz, Yankel Traub (7), Nachman Kahana (6), Shmuel Kahana (7), Leib Nadler (7), Juda Mihaly (6), Avraham Springer (6), David Nadler (8), Itzik Perl (6), Hilda Kaufman (5), Leib Vilkuni Sabo (8), Avraham Yechezkel (4), Avraham Davidovitch (5), Avigdor (2), Hersch Kahana (4), Hersch Kopler (2), Aizik Solomon (4), Aizik Tabak (4), Leib Marko (4), Hersch Stein (4), Juda David (3), Yosef Meir (3), David Rubin (4), Anshel Weider (4), Marku Katz, Motzen Farkash (4), Reuven Berkovitch (7), Leib Aizik (6), Avraham Adler (9), Yoel Davidovitch (10), Leib Kalman (5), Avraham Yosef Malik (4), Aizik Markovitch (7), Moshe Leib (6), Leib Yosef Branisz (3), the younger Yankel Hoch (6), Shimon Dik (4), Solomon Davidovitch (2), Meir Benedik (2), Hirsch Eilovitch (3).

Torah LifeSziget was a city of scholars, scribes, learned people and Hassidim. This was not the situation at the beginning of the community, when the Jewish community was small, numbering only a few dozen souls. In the early era, it did not have Torah scholars and learners. The city was cut off from Jewish centers and sources of Torah study. As the Jewish community grew in population, it also grew in Torah study and the proper fulfillment of commandments. Torah knowledge grew in stages, and the Jews of the city began to concern themselves with educating their children in the ways of Torah in the cheders that were established in all parts of the city. In particular after the penetration of Hassidism, its doctrine, way of life, and customs to the city and region during the second and third generations of Hassidism, the study of Torah also strengthened in wider and wider circles, as will subsequently be explained.

[Page 5]

The majority of the rabbis of Sziget had national renown as Torah greats, heads of large Yeshivas and Admorim (Hassidic leaders).

The first rabbi of Sziget was Rabbi Tzvi the son of Rabbi Moshe Avraham, who arrived in the city around the year 5519 (1759). He fought strongly against the Sabbatean and Frankist influences in the city. This matter caused him many tribulations, and was the cause of a blood libel against him in particular and the Jewish community in general. For an unknown reason (some say because of a plague) he left the rabbinate of Radwil in Poland and accepted the yoke of the rabbinate of Sziget, which was a small community in those days. In a census from the year 5530 (1770), his name was enumerated in the list of residents as the name Hirsch Abramovitch. He died on Elul 2, 5531 (1771). The unusual inscription on his gravestone (“The rabbi, the renown leader [!][[4]], the head of the rabbinical court and ordained rabbinical judge, Rabbi Tzvi the son of Moshe Avraham of blessed memory”), which does not befit a rabbi proves that in all of Sziget, there was nobody capable of formulating a gravestone inscription in the customary and appropriate fashion.

The rabbinate of Sziget remained vacant for approximately 30 years, even though a rabbinical guide served there (see the following). In the view of Reb Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, the historian of the Jewish community of the city and its rabbis, “the rabbis refused to accept the rabbinical position in Sziget because they did not find the aroma of Torah there”. In the year 5562 (1802), the next rabbi of Sziget was chosen, the Gaon Rabbi Yehuda the son of Rabbi Yosef HaKohen Heller. It is almost certain that his composition Kuntres Hasfeikot that was appended to the well-known book Ketzot Hachoshen which was written by his brother Rabbi Aryeh Leib HaKohen and was published 14 years earlier (Lvov 5548) – came to the attention of the parnassim [community leaders] of the city and was a decisive factor in choosing him as the rabbi. In the meantime, there was already a circle of scholars in the city who were able to hold in esteem a rabbi on account of his expertise in Torah and his conduct in the fear of Heaven.

Rabbi Yehuda Heller was born in Kalusz in Galicia. At first he earned his livelihood in business, and later he ran a tavern in a town near Kalusz. He moved to Lvov after suffering an economic setback. There, he taught Torah to capable and eminent youths. He met the author of the Pri Megadim in Lvov, who was teaching there as well, and he became friendly with him. In Lvov, he supervised the publication of the Ketzot Hachoshen. Before Sziget, Rabbi Yehuda Heller served as the rabbinical judge in Munkacz and the rabbi of Seles. His name became known throughout the country immediately upon his arrival in Sziget. In the year 5565 (1805), after the death of Rabbi Paysh Vina, he was offered the rabbinical seat in Grosswardein (Oradea), but he refused. The Chatam Sofer also held him in esteem. When a crisis in the rabbinate broke out in the city of Carlsburg and the province of Transylvania, the Chatam Sofer recommended that the rabbi be examined by “my close friend, the renowned rabbi and Gaon Rabbi Yehuda Kahana the head of the rabbinical court of the Máramaros region.” Rabbi Yehuda Kahana Heller died on the 27th of Nissan 5579 (1819). He left behind seven sons and a daughter, from which the renowned Kahana family of Sziget and other areas spread out – including rabbis, scholars and wealthy householders. Some of them will be discussed later.

Rabbi Yehuda HaKohen Heller left behind several works, including a large book on the Bible that Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald looked into in the year 5668 (1908), but remained in manuscript form and was apparently lost. The Kuntres Hasfeikot book that is printed along with the Ketzot Hachoshen was published only once, by one of his grandsons Rabbi Shmuel Zeinwil Kahana of Munkacs, 5550 (1790).

Many years after his death, his book Trumat Hakri on the Choshen Mishpat section of the Tur and Code of Jewish Law was published by his son's son-in-law the Gaon Rabbi Yehuda Modron of Sziget (see about him later), who added many glosses and novel interpretations to it, Petersburg 5618 (1858). These two books, Kuntres Hasfeikot and Trumat Hakri, were republished by photocopy in one volume in New York, 5736 (1976). Trumat Hakri alone was republished by photocopy several times (5715 / 1955, 5726 / 1966, 5730 / 1970).

When Rabbi Yehuda Heller was selected as the rabbi of Sziget, he was not chosen by unanimous opinion. The leaders of the community of Sziget, headed by the parnas Reb Moshe Gitzim, (the son-in-law of the first rabbi Rabbi Tzvi), indeed sided with Rabbi Yehuda Heller. However, the leaders of the Jews of the region, – for the rabbis of Sziget served as the rabbis of the entire region of Máramaros – headed by the Stern family who were extremely wealthy Hassidim, men of deeds who lived in several villages of the region, preferred their relative Rabbi Menachem the son of Reb Shmuel Stern, who was at the time a rabbinical judge in Kalusz under the rabbinate of the author of Chavat Daat. Each side was persistent. One side traveled to Seles to bring Rabbi Yehuda Heller, while the opposing side went to Kalusz to bring Rabbi Menachem Stern. When the two rabbis met face to face in Sziget, they reached a compromise. Rabbi Menachem Stern gave in and agreed to serve as the head of the rabbinical court of Rabbi Yehuda Heller.

After the death of Rabbi Yehuda HaKohen Heller in the year 5579 (1819), Rabbi Menachem Stern was chosen to replace him. He was the first rabbi that was born in Máramaros. His father Reb Shmuel the son of Reb Mordechai Stern lived in the village Dragomireşti (see entry) where Rabbi Menachem was born in the year 5519 (1759). He studied Torah in several places in Galicia, particularly in the city of Manasterz under Rabbi Yaakov of Lissa the author of Chavat Daat. Rabbi Menachem Stern also attached himself to Hassidim, and was the student of Rabbi Moshe Leib of Sassov and the Maggid of Koznice. In the latter thirty years, he followed Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kosow the author of Ahavat Shalom.

Rabbi Menachem Stern established new orders in the region of Máramaros. As the Jewish population began to grow in the villages of Máramaros, he made sure that there would be a spiritual leader in every large Jewish community. He set up rabbis in the two largest communities, Borsa and Viseu (see entries). He set up shochtim and melamdim in the smaller villages, and he established their regulations. He organized minyans (prayer quorums), and if there was not a minyan, he grouped together neighboring villages into a joint minyan. He measured the Sabbath boundary, and demarcated the boundaries of the eruv between villages[[5]]. He organized Torah classes that were spiced with Hassidic doctrine and sayings. He also promoted peace between man and his fellow, and man and his wife. He began to lay the foundations for communal life in the towns of Máramaros immediately after his acceptance as the head of the rabbinical court in 5562, for according to the agreement between Rabbi Yehuda Heller and him, Rabbi Menachem Stern was responsible for overseeing the region, even though the rabbi of the city also served as rabbi of the region. He increased his activities when he was appointed rabbi of the community. At the end of his days, when he saw blessing in the fruits of his labors, he bade farewell with the following words, “Máramaros is my garden, and I planted it.” Rabbi Menachem Stern died on the 9th of Adar, 5594 (1834).

Rabbi Menachem Stern left behind many works. According to the testimony of his son-in-law, “he left behind a large composition on several laws of the four sections of the Code of Jewish Law, and on the laws of interest in particular. There is a large volume approximately forty sheets in length explaining the Gemara and Halachic decisions.” Reb Yekutiel

[Page 6]

Yechiel Greenwald saw “a large work on Psalms and a treasury of questions and responsa that he answered to those who asked him, and that the great ones of Israel answered to his questions. I saw with my own eyes responsa from the Gaon Rabbi Yehuda Orenstein the author of Yeshuot Yaakov, and others.” However, these compositions were not published. After his death, his son-in-law and successor published a large composition on Torah in three volumes:

[[6]] The Derech Emuna book on all of the Torah portions. [Book of Genesis] Chernovitz, 5616 (1856). [4], 52 [1] pages.

The Derech Emuna book… [Book of Exodus] Chernovitz, 5617 (1857). [1], 50 pages.

The Derech Emuna book… Leviticus, Numbers, [Deuteronomy]. Chernovitz, 5620 (1860). 124 pages.

Responsa to him

Responsa of Mare Yechezkel, section 102, The Rabbi and famous Gaon. A long and esteemed genealogy. Torah interpretations and discussions.

Shaarei Chaim page 34, folio b. I asked the great and famous rabbi, the Rabbi and Gaon Menachem Mendel the rabbi of Sziget and Máramaros region, may he live.

Responsa Yeshuot Yaakov on Even Haezer, section 12. To the community of Sziget in the country of Hungary; to the Rabbi and Gaon Menachem Mendel the aforementioned head of the rabbinical court. The responsa deals with the question of an aguna[[7]] whose husband was found murdered on the road. His head was cut off, and his body was identified by the clothes and various marks on the body.

After the death of Rabbi Menachem Stern, once again opinions were divided with regard to the selection of a rabbi of the city. The Hassidim of Kosow desired his son-in-law Rabbi Yosef Stern. However, the Kahana family wanted Rabbi Elazar Nisan Teitelbaum the son of the well-known Tzadik Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum of Ujhelyy. One of the members of the Kahana family, the wealthy man Reb Kalman Kahana, who was at the time a young man being supported at the table of his father-in-law Reb Pinchas Samater in Ujhely and was a frequenter of the house of Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum, was the vital force in the selection of Rabbi Elazar Nisan. A delegation from Sziget consisting of Reb Moshe Katz and Reb Manish Polak, was sent to Ujhely to negotiate with the father of the candidate and with the candidate himself. Reb Moshe Teitelbaum gave the delegation a letter addressed to the community leaders of Sziget: “Given that I hear that you are seeking a rabbi and teacher for your community, I hereby inform you that my only son is fitting for that position, and he is great like one of the greats in his sharpness, expertise, piousness and holiness. Even though a father does not testify about his son, I am exposing a little and hiding a lot. You will not be embarrassed by him in this world, and not shamed by him in the world to come.” Only 82 people signed the rabbinical contract. His salary was set at 300 guilder per year. His father the author of Yismach Moshe accompanied him, so that he would be welcomed by thousands of Jews in all the stops along their route to Sziget. Rabbi Yosef Stern accepted the decision and agreed to serve as head of the rabbinical court under the rabbi.

However, the match between Rabbi Elazar Nisan Teitelbaum and the Jews of Sziget did not work out well. He decided to leave a mere five months after his arrival in Sziget. Apparently, the opposing faction, which included the majority of the community and especially those of the towns of the region, did not make peace with his appointment. They embittered the life of the rabbi in a variety of ways: they spread rumors and slander about him that he was appointed by a minority in opposition of the majority. Members of the Kahana family prevented him from leaving the city. They urged him to hold his anger with promises that he would be able to continue on in peace. However, a new dispute broke out not long thereafter, this time with the council of Reb Moshe the shochet of Kretshinov, who was banned by the rabbi with the accusation that he did not check for the signs of a kosher animal after the slaughter[[8]]. This shochet was a Hassid of Kosow. In the wake of this, he left Sziget in the year 5600 (1840) and returned to Ujhely. A short time thereafter he was appointed as the rabbi of Drohobycz in Galicia, where he died on the eve of Yom Kippur 5615 (1854).

Rabbi Elazar Nisan Teitelbaum was born in Szienjawa, Galicia in the year 5546 (1786). He found the rabbinate distasteful, and was apparently pushed into it by family pressure. He was very diligent in his studies, and he conducted himself with asceticism and separation from the vanities of this world. He sat in his room the entire day studying Torah, enwrapped in his tallit and wearing his tefillin. He did not become involved in communal affairs and recoiled from contact with the masses for fear of being taken away from Torah. He did not write down his Chidushim [interpretations] since they were etched in his fantastic memory. He remembered everything that he studied, and the only reason to write down words of Torah was because of the likelihood of forgetfulness. Two of his responsa were published in his father's book Heshiv Moshe and in the responsa book Aryeh Devei Ilay of his brother-in-law Rabbi Aryeh Leibish Lifschitz.

Responsa to him

Responsa Imrei Eish on Yoreh Deah section 2”: The great rabbi and luminary who speaks righteousness, an expert in the breadth and depth of Torah, who acquired wisdom and knowledge, “That which took place in one village (Kretshinov) where there was Reb Moshe the shochet… who let an improperly slaughtered animal slip by him for he slaughtered and did not examine the signs… He fired this shochet…He certainly acted in accordance with the Torah.”

With regard to this matter, two letters were published by Reb Yechezkel Panet, the author of Mareh Yechezkel at the beginning of the Responsa book Derech Yivchar of his son Rabbi Chaim Betzalel Panet. He also justified the verdict of Rabbi Elazar Nisan and expressed his dismay that the disputants do not accept his verdict, and continue to eat of the meat slaughtered by the shochet. His second letter was directed to the Jews of Kretshinov. He warned them “to refrain from eating the despicable meat… and it is strange in my site that there are those who do not pay attention to the gaon and head of the rabbinical court, may he live, with matters that go against his honor.” The responsa in Baalei Eish and the letter of the author of Mare Yechezkel were published without dates, but we can surmise that these were written a short time before he left Sziget.

His fortune was not favorable in Drohobycz as well. There too, he was the target of the anger of one of the city notables, and this time as well, regarding the matter of shochtim. In the Ramatz book of responsa by Rabbi Meir Tzvi Witmeir the head of the rabbinical court of Sambor, Yoreh Deah sections 3-4 from the year 5611 (1851), it is stated: “with respect to the dispute in your area about the complaints against shochtim in your community… as was written by Rabbi Avli may he live Rb [Rosenberg?] to ban their slaughter, and the rabbi and Gaon Rabbi Elazar Nisan wrote to permit it without any dispute or recourse. Disgrace and fury should be poured onto the opposing side, as if they know without doubt that his intentions were not for the sake of Heaven.”

Rabbi Moshe Stern was chosen as the head of the rabbinical court of Sziget and the region after the departure of Rabbi Elazar Nisan Teitelbaum from the city. Rabbi Yosef the son of Rabbi Yitzchak Stern was born in the year 5563 (1803) in the town of Strîmtura (see the entry on it). His father was the aforementioned Rabbi Mordechai Stern. He was educated in the home of the Tzadik Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kosow, the author of Ahavat Shalom. He studied together with his son and heir Rabbi Chaim the author of Torat Chaim. After he married the daughter of his cousin Rabbi Menachem Stern, he was supported at his table.

[Page 7]

Just as Rabbi Elazar Nisan Stern suffered trials and tribulations at the hands of the Hassidim of Kosow, Rabbi Yosef Stern suffered bitterness from the opposite side. They hatched plans to lessen his honor and embitter his life. Their primary claim was that he was not a great scholar, and his expertise in rabbinical leadership was not sufficient for the needs of a city such as Sziget; even though, according to Naftali the son of Menachem, “he boasted that he studied the Yoreh Deah section of the Code of Jewish Law 140 times, and the other sections of the Code of Jewish Law 111 times.” The Gaon Rabbi Yehuda Modron entered him into a dispute on a Halachic matter: a woman from Sziget salted her meat by accident with halon powder. When the question was asked to Rabbi Yosef Stern, he answered, after consulting with professional chemists, that the action of this powder is similar to salt, and therefore it was permissible to eat the meat after washing and re-salting it. Rabbi Yehuda Modron disputed this decision. In his opinion, the powder blocked the escape paths of the blood, so re-salting would not be effective. He alarmed the great ones of Israel with this, and most of them agreed with him. This matter broke his spirit. According to tradition from his grandchildren, Rabbi Yosef Stern was by nature a modest man who was pleasant with his fellow. He died on Shushan Purim 5618 (1858) at the age of 55. Apparently, Rabbi Yosef Stern did not publish his commentaries. He brought the book Derech Emuna of his son-in-law to print, and wrote an introduction to it.

Responsa to him

In the responsa of Avnei Tzedek (of Rabbi M. Panet), section 58-59 from the year 5610 (1810). Two responsa deal with the release of an aguna from Borsa whose husband was murdered by gentiles in the next village of Luduş.

The responsa of Maharia”z Enzil section 43 from 5610: regarding a get (bill of divorce) that was brought to Sziget, and several lacunae were found in its authorization. Section 44 of that year: regarding the meat that was salted with halon: “He decided properly to permit everything post factum.” Section 49 from the year 5611: regarding a large inheritance in the city of Josani. Section 50: about the same matter the question of Rabbi Yosef Stern in full. Section 64 in the year 5611: regarding the aguna mentioned in the responsa Avnei Tzedek. Section 71 from 5615: “regarding those who mislead our Jewish brethren to permit bread made of corn flour on Passover.”

Responsa Tosafot Reem Yoreh Deah section 11: regarding wolves that entered a sheep pen. One lamb was found killed and two wounded. Since the honorable rabbi found it forbidden, those who permit it are not acting properly. Even Haezer section 4 from the year 5600 (1840): regarding the permission of 100 rabbis (a form of marriage annulment) for a man whose wife fled after she had been suspected of promiscuity “and I agree with the honorable rabbi to permit him to marry a different woman, for there is a matter of a mitzvah here. We must also be careful lest he become involved with a bad group.” There at the end of the responsum: regarding judges who were ignoramuses in one of the towns of Máramaros: “it is appropriate to fine those who were involved in this, so that all the people shall see and take heed.” Choshen Mishpat section 31 (his name is confused: Yosef Leib may he live the head of the rabbinical court and rabbinical leader of Sziget in the land of Hagar.): regarding a contract that was partially remembered, and it said among everything else: “except that it is a decree of the king that Jews cannot purchase a home from a gentile except through a pledge, and the gentile can redeem it at will.”

Responsa Yad Eliezer section 74 from the year 5610: regarding meat that was salted with halon. “from the content of his letter, it is clear that he is capable in dialectics and halacha… who is his equivalent as a teacher in his community, and who can raise his head in his community to dispute the rabbi in what he has taught with wisdom?”

Chidushim of Anshei Shem section 60: regarding the writing of the name Chananya in gittin (divorce documents). “He ordered that it be written with a he at the end, and they disputed him… it is kosher post facto, and those that dispute are casting aspersions on the get.”

Respnosa Tuv Taam Vadaat first edition section 111: once again on the matter of meat that was salted with halon. “Behold my friend is immersed in the matter, and it should not be said… he did not decide properly on this, and the good G-d shall forgive him.” For the rest of the responsa on this matter, see later in the section on Rabbi Yehuda Modron. Responsa Chesed LeAvraham Yoreh Deah section 32. Even Haezer section 8 from the year 5617 (1857).

On the 18th of Tammuz 5618 (1857), the Gaon and Tzadik Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum the son of Elazar Nisan came to Sziget. From then, the rabbinate of Sziget did not depart from the Teitelbaum family for 86 years, until the Holocaust. Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda was born in Ujhely in 5568 (1808). He was educated and raised in the home of his grandfather Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum in Ujhely. He married the daughter of Rabbi Moshe David Ashkenazi, at first the rabbi of Tolcsva and at the end of his days the rabbi of Tzfat, the author of the books Toldot Adam and Beer Sheva. He was chosen as the rabbi of Stropkow already during his grandfather's lifetime (5593 / 1833). After the death of his grandfather in 5601 (1841), he was chosen to take his place in Ujhely. Four conditions were made with him to appease the non-Hassidim in the community of Ujhely: a) that he would not conduct the Musaf services[[9]]; b) that he would not issue amulets, whether for free or for payment; c) that he would not accept petitions; d) that he would not insult the members of his community in his sermons. Since according to these groups, he did not live up to these conditions, they petitioned to the civic government, and he was expelled on the Eve of Rosh Hashanah 5607 (1846). The community of Gorlice in Galicia hurried to invite him to be their rabbi. He was grateful to them for his entire life, “for they invited me in at the time of my difficulty”. In the year 5555 (1855), he was chosen to take the place of his father in Drohobycz, but he did not hasten to leave Gorlice, for “the city of Gorlice was jealous of Drohobycz, and added to his salary”. The community of Drohobycz sent “three carriages hitched with horses in accordance with their honor and his honor, with two learned men… and the men with the wagons returned empty handed.” In the meantime, another faction arose in Drohobycz who chose Rabbi Eliahu Horoshovski whose father had also served there (before Rabbi Elazar Nisan). Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum arrived in Drohobycz on the eve of Sukkot 5516 (1856), after his mother had died there on the 3rd of Tishrei. Then his friends and followers asked him to accept the rabbinate. The two factions reached a compromise that they would accept two rabbis. Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda arrived to occupy the rabbinical seat of Drohobycz on the week of the Torah portion of Chukat, 5616. We must add that friendship prevailed between the two rabbis of Drohobycz.

Apparently, Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda desired to return to the land of his birth and rearing, and therefore, he attempted to attain the rabbinical seat of Sziget. When he heard of the death of Rabbi Yosef Stern, he settled in the vacation and spa town of Breb near Sziget – apparently upon the invitation of his friends and admirers in Sziget from the era of his father. When the wealthy scholar Rabbi Shmuel Zeinwil Kahana, the author of Kuntres Hasfeikot and the father-in-law of Rabbi Yehuda Modron, died in Sziget, he was called to eulogize him. The eulogy left a deep impression upon the audience. This was the first step to his acceptance as a rabbi by the decisive majority of the residents of the city.

It is worthwhile to study how it came to pass that in Sziget, where the Kosow Hassidim had always ruled, Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum, who was not raised in this style of Hassidism, was accepted. It appears that several causes converged to enable this choice: a) we must remember that at this time, Kosow Hassidism was not a united group. For in the year 5514 (1854) Rabbi Chaim of Kosow died and his Hassidic legacy was divided between his two sons, Rabbi Yaakov Shimshon who took his place in Kosow itself, and Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vishnitz, from whom the Vishnitz dynasty stemmed.

[Page 8]

The Kosow Hassidim in Sziget were also divided, and tensions naturally arose from the division; b) the talents and spiritual abilities of Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda as a respected Gaon and a wonderful preacher who wins the hearts of his audience. There is no doubt that his name was known since he had occupied the rabbinic seat in three cities for the previous 25 years; c) one of the first action of Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda was a visit to the court of Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vishnitz when he visited Dragomireşti. During this visit he won his trust, and this probably neutralized the opposition of many of the Hassidim of Kosow-Vishnitz. During his Torah lectures, he would often mention rabbi Yisrael of Rizhin, the father-in-law of Rabbi Menachem Mendel. Some of these even made it into his books (see for example Yitav Panim, the article Avnei Zikaron). He would also mention Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kosow (such as in Yitav Lev, portion of Lech Lecha). These would bring close the hearts of the Hassidim of Kosow-Vishnitz.

The longer that Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum lived in Sziget, the more supporters, Hassidim and adherents he acquired. He was among the greatest of rabbis of his generation in his greatness in Torah. He was an Admor to his growing number of Hassidim. His Torah, prayers, and especially his sermons that were in the style of his illustrious grandfather the author of Yismach Moshe, enchanted his listeners. Above all was his large Yeshiva, which was unique in its kind. This was the first Hassidic Yeshiva in all of Hungary, which taught Hassidism in addition to Talmud and legal decisions. Without doubt, the Yitav Leiv Yeshiva of Sziget, whose students came not only from Sziget and Máramaros but also from the entire expanse of Hungary, won over many souls to enhance the name of its founder and to disseminate Hassidic ways and lifestyle throughout Hungary in general, and in Sziget and Máramaros in particular.

|

|

Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum died on the 6th of Elul 5643 (1883). He was eulogized appropriately in many communities. Some of these eulogies have been published, such as: Likutei Chaver Ben Chaim by Rabbi Chizkia Feivel Plaut section 6, Munkacz 1884, page 88; Mateh Naftali and Likutei Beit Efraim by Rabbi Naftali Sofer Munkacz 5647 / 1887 sermon 5; Evel Kaved by H”V”D [?], Czernowitz 5644 page 9; Ayeh Sofer by Rabbi Mordechai Rubenstein, Krakow, 5644, page 29; Kuntrus Tzlaot Habayit appended to the Beit Yitzchak Responsa of Rabbi Yitzchak Shmelkes, Even Haezer Volume 2, sermon 6; Imrei Shevach of Rabbi Shmuel Glaz HaKohen, Zalishchyky, 5654, page 7; Mincha Belula Bashemen by Rabbi Shlomo Miller, Budapest 5688, section 2, pages 27-32.

His first literary endeavor was the publication of the books of his grandfather, Yismach Moshe on the Torah and the Heshiv Moshe Responsa, in which some of his own responsa were also published. He published two books in his lifetime. He hid his name in the first book. The following is the text of the preface:

The Book Yitav Leiv on the Five Books of the Torah with which G-d graced his servant because He loved his fathers and chose in his progeny that followed him. He concealed himself, downtrodden and embarrassed. He hid his face in his cloak and exposed the study. This is his name forever… Sections 1-5, Sziget 5635 (1875). [3]: 141, [2]: 91, [1], 55; [1], 90; [1], 70; [1] page.[[10]]

Published by photocopy Brooklyn, 5728 (1968).

The Book Yitav Leiv on the festivals. Section 1, Lemberg 5642, [2] 163 pages; section 2, Munkacz 5643, [1] 160, [1] page.

Additional publication, Chust 5672, (two sections in one volume). Published by photocopy, Brooklyn, 5723. Published by photocopy in part (Sukkot only), New York, 5708 (1948).

After he died, the following were published:

Responsa of Avnei Tzedek, volumes 1 and 2, Lemberg 5645-5646. [4] 90; [3], 81-154 pages.

On the section Orach Chaim {of the Code of Jewish Law}, 112 sections. Yoreh Deah, 159 sections. Even Haezer 61 sections. Choshen Mishpat 20 sections. At the end of the even Haezer sections there is novellae on Tractate Kiddushin, chapter 1.

322 responsa were written to 156 people (several responsa were written to the same person, and on some responsa, the name of the person was removed). The names of the questioners provide a reliable survey of the tenure of the author in the communities of Hungary, Galicia and Máramaros. 42 questioners resided in Hungary, 12 in Galicia, Bukovina and Romania, 20 in Transylvania, and 18 in the Máramaros region.

Published by photocopy, New York, 5728 (1968).

The book Rav Tuv on the Torah, Lemberg 5649, [1], 183 pages.

Published by photocopy in Brooklyn, 5733 (1973).

Responsa to him:

Responsa Divrei Chaim volume 1, Even Haezer section 10, from the year 5610 (1850). From the famous rabbi and gaon, the head of the rabbinical court of Gorlice, on the topic of the permission of 100 rabbis {to annul a marriage) in a case where a man's wife left him on account of famine. Volume 2 Orach Chaim section 3 from the great rabbi and gaon may he live, the head of the rabbinical court of Sziget, regarding the laws of tefillin. Even Haezer section 54 from the famous and pious rabbi and gaon, the splendor of his era, the head of the rabbinical court of Sziget, regarding the permission of an aguna whose husband was found dead in one of the villages of Máramaros.

The responsa of Maharam Shik Orach Chaim section 104 from the year 5633 (1873). The great rabbi and gaon, the holy candle, etc. “With respect to a man who had horses and wagons, and regularly ran the route from the train station to the city… and he wished to do so on the Sabbath as well by selling his horses.” There, section 213, from the year 5639 (1879) regarding the known dispute in Beregszász about the rabbinical judge who was accepted there without the approval of Rabbi Avraham Yehuda HaKohen Schwartz, the author of Kol Aryeh.

[Page 9]

Responsa Shaarei Tzedek Orach Chaim section 26: interpretations and dialectics; Ibid. Yoreh Deah section 31 from the year 5631: regarding a shochet who suffers from epilepsy. Responsa Avnei Tzedek section 69 from the year 5638: Regarding an aguna from the city of Gerla (Samosz-Ovivor)

Responsa Beit Shearim Yoreh Deah section 193 from the year 5639: “Behold, the people of my city are building my house… and in the middle, I recalled the will of Rabbi Yehuda Hechasid who forbade the dismantling of an oven, and I commanded the work to stop… I said I would inquire from a holy mouth whether there is an acceptable manner of permitting this.” The responsa of Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda is published there: “There is no concern here at all, only that no stone from the oven be left in the place of the oven. The ground under the oven should also be removed a handbreadth of more… Thus did they do in my prayer house… For thus did I learn from the holy Gaon Rabbi Shalom of Belz.”

Responsa Chatan Sofer section 61 from the year 5642: Regarding a man from Szatmar whose wife took an oath before his death that she would not marry, and now she cannot abide by her oath. “The holy gaon should express his opinion as to whether I the young one can open with permissiveness, and whether the holy gaon would agree.”

Responsa Nachala LeYisrael section 1 from the year 5635. Interpretations and discussions: Section 35 from the year 5629: Regarding the ritual fitness of a mikva in Niżniów (Galicia): Section 50 from 5635. Words of strife and who was excommunicated for his disgrace. (The words are cryptic, and what is meant is not explained. Apparently the matter took place in Galicia.)

Responsa of Hada”r volume 2, section 45: Regarding a Torah scroll that the Tzadik Rabbi Yitzchak Aizik of Kalib wrote for himself in cursive writing. “And I set my heart to expound and to investigate what mitzva was involved in this and what reason there was for this.” (The responsum was also published in the Responsa Avnei Tzedek on Yoreh Deah section 108.)

Responsa Shoel Umeishiv first edition, volume 2, section 19 from the year 5616. Regarding the rabbinate of Reite”v in Drohobycz.

The selection of Rabbi Chanina Yomtov Lipa Teitelbaum to replace his father the Yitav Leiv in Sziget was apparently natural and self-understood without any tension. He was born on the first day of Shavuot 5596 (1836) in Stropkow. In his first marriage, he was the son-in-law of the Tzadik Rabbi Menashe the son of Rabbi Asher Yeshaya of Ropszyce. However, he had no children from this union, and in the year 5637 (1877) he received permission to divorce his wife. A year and a half previously, the couple signed an agreement between themselves before and at the behest of Rabbi Chaim Halberstam. However, she returned to her parents' home and did not wish to receive a Get. After the permission of a hundred rabbis (marriage annulment) (see further on in the responsa that were written by the judge Rabbi Chaim Aryeh Kahana), he married the daughter of his uncle Rabbi Yoel Ashkenazi, the head of the rabbinical court of Zolochow. Together, they had sons and daughters. He studied Torah from his father, and cleaved to the author of the Divrei Chaim of Tsanz, to whom he traveled several times a year. In the year 5624 (1864), he was chosen as the rabbi of ţeţche. As has been stated, after the death of his father, he was chosen to take his place in Sziget. He was famous as a gaon in Torah and a leader of stature.

Rabbi Ch. Y. L. Teitelbaum expanded his Torah activities in Sziget in all areas. Many benches were added to his Yeshiva. His activities as an Admor similarly grew. Many Hassidim, headed by rabbis of the country (even of the Ashkenazic stream) started to follow him. His influence was similarly great in communal affairs. He was one of the chief spokesman and one of the fighters for the Hassidic camp within the organization of Orthodox communities. In the year 5658 (1898), when Rabbi Aryeh Leib Lifschitz the rabbi of Santov and a vehement opponent of Hassidism was elected as the president of the Orthodox office in Budapest, Rabbi Ch. Y. L. Teitelbaum summoned the Hassidic rabbis to a meeting in the town of Makafalva. Approximately 50 rabbis participated in this meeting, and as a result of it, a vice president who was acceptable to the Hassidic camp was selected. One of the terrible events of the annals of Sziget Jewry took place during his time – a schism in the community about which we will speak later.

Rabbi Chanina Yomtov Lipa Teitelbaum died on the 29th of Shvat 5664 (1904). A eulogy to him is published in the book Arugat Habosem on the Torah (Chust 5673), Torah portion of Tetzaveh, sermon for the 7th of Adar.

Another article was written about him:

The book Kedushat Yomtov on the Torah and the festivals. Sziget 5665 [2], 137, page 64.

Published by photocopy : New York 5707 (1947).

Responsa to him:

The responsa book Avnei Tzedek of his father, Orach Chaim section 56, 100. Even Haezer section 29. Responsa Mei Beer section 38 from the year 5647 (1887): Regarding words of controversy that arose among some people in the holy camp, and they wanted to break off into a separate community.”

Responsa Birchat Chaim section 116: Regarding the aforementioned matter. (He was answered by Rabbi Nathan Sega”l Goldberg, the head of the rabbinical court of Limanow.)

Responsa Zichron Yehuda volume 1 section 203 from the year 5646; volume 2 sections 46, 145.

Responsa Beit Shearim Yoreh Deah section 390 from the year 5637 from ţeţche.

|

|

After the death of the author of Kedushat Yomtov, of course his eldest son Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum was selected to take his place. He was born in ţeţche in the year 5640 (1880) He married the daughter of Rabbi Shalom Eliezer Halberstam of Ratzfert (Ujfeherto) the youngest son of the author of the Divrei Chaim. He studied Torah in the house of his father and traveled to the Tzadikim of the generation, especially to the children of the Rebbe of Tzanz Rabbi Yechezkel Shraga of Sienjawa, his uncle Rabbi Baruch of Gorlice, and Rabbi Yehoshua Rokach the Rebbe of Belz. In addition to his greatness in Torah and fear of heaven, he was known as a particularly wise man with deep intelligence. Within a short period of time, he took the place of his father as a leader of the Hassidic movement, a person of great influence in communal life, and one of the influencers of Orthodox Jewish life in Hungary. The net of Rabbi Chaim Tzvi was spread throughout almost all of the Orthodox communities of Hungary. He was alert to all that was transpiring in the communities. His opinion had great weight, and at times the was the deciding force in the selection of rabbis and the appointment of judges and shochtim in many communities, especially in those places where there were Hassidim of

[Page 10]

Sziget. The Yeshiva was run in the style that was set by his grandfather the Yitav Leiv and his father the Kedushat Yomtov. He had a fabulous memory. One of his students, Rabbi Avraham Chaim Hershkovitch testified that he heard his Rebbe state that he does not know what forgetfulness is, for he never forgot anything of his learning. Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum did not live long. He died suddenly on the 6th of Shvat 5686 (1926) in the city of Kleinwörden when he was only 46. His death caused great mourning. His coffin was brought to Sziget and he was buried in the canopy of his fathers. The greatest Hungarian rabbis of the era came to eulogize him.

Despite his short life, he left behind many compositions of deep scope. The following were published:

The book Atzei Chaim on the Torah in two volumes, volume one on lore, and volume two on exegesis. Sziget, 5687 (1927). [2] 126 [1] 50 pages. Published by photocopy in Brooklyn, 5716 (1956), with a few addenda.

The book Atzei Chaim on the festivals. Sziget 5694 (1934) [2], 158 pages.

The responsa book Atzei Chaim on the 4 sections of the Code of Jewish Law, Sziget 5699 (1939). [3], 136 pages.

The 67 questions in the Atzei Chaim responsa are divided as follows: 31 from Transylvania and Máramaros, 27 from other locations, 9 from unidentified locations. It is worthwhile to note that a significant majority (43) of the questions were from rabbis and rabbinical judges.

The book Atzei Chaim Volume 2 on the laws of Mikva. Sziget, 5699. 31 pages.

The book Atzei Chaim on tractate Gittin. Sziget 5700 (1940). [3] 52 pages.

In the preface to this book, he states that he “wrote other works that are still in manuscript form”. Apparently, they were lost in the Holocaust.

Responsa to him:

Responsa book Zichron Yehuda volume 1 section 194 from the year 5674 (1914). Regarding spirits on Passover… Forbidding new spirits that were made with proper supervision from leavening out of concern lest they become mixed with other spirits… In any case, one must consult about this matter.” Ibid. section 207 without a date, however from the content it can be deduced to be from the time of the First World War: “The world is screaming and asking why the rabbis are silent and not banding together to offer advice from their souls… so that all of the evil decrees against us will be annulled… enemies, plague, sword, hunger, and captivity… and above all the great spiritual danger that is hovering over the world… and I state before the rabbi and gaon may he live that his honor should pardon me a thousands times, that he should write to the delegation and agree to decree a one day fast… to prove the keeping of the Sabbath to them… and the raising of children in the study of Torah, and a warning to preserve the law of Moses and Judaism. The delegation will send the letters throughout the country.”

Responsa Bnei Shemaya section 66. This responsum was also written during the war years. “Regarding the tribulations and afflictions of the times, the income of the community has dwindled significantly.”

Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum left behind young orphans when he died. The eldest Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum was only 14 years old. Nevertheless, the communal leadership regarded him as the rabbi of Sziget. In order that he be fitting for that position, Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Gross, the rabbi of Berbeşti and also a grandchild of the Yitav Leiv was called to Sziget. The rabbi of Berbeşti was appointed as the rabbinical judge of Sziget and asked to teach the young rabbi and train him for the rabbinate. His first wife was the daughter of his uncle Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum, at the time the rabbi of Kruly. His wife died a short time after their wedding. He later married the daughter of his cousin Rabbi Zusha Halberstam of Ratzfert (the daughter of Rabbi Shalom Eliezer). With the passage of time, the young man proved that his selection was appropriate. Through his diligence in Torah, he became proficient in Talmud and Halachic decisors. He issued decisions and conducted the Yeshiva as one of the veteran rabbis. He conducted the Admorship with confidence and esteem. He displayed great self-sacrifice during the years of the Holocaust with regard to rescuing Holocaust survivors in Poland. (See later in the chapter on the Holocaust). Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum perished in Auschwitz on the 25th of Iyar 5704 (1944).

His writings were lost in the Holocaust. Few remnants remain, which are published at the end of the Atzei Chaim book on the Torah that was published by photocopy in New York in 5716. Two responsa about his chidushim in Halacha and explanation of Talmudic discussions were published in the book Mekadshei Hashem, volume 1, section 73; volume 2, section 22.

|

|

of holy blessed memory |

The Admor of Szatmar for approximately 70 years, Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum, was a native of Sziget. He excelled in his sharpness from his early youth, and it was evident that he was destined for greatness. After the death of his father the author of the Kedushat Yomtov, Hassidim and students attached themselves to him when he was a very young man. His first rabbinate was in the town of Orşova, but he lived in the city of Szatmar (Satu Mare) for most of the time, where his Hassidim built a large Beit Midrash for him. He was chosen as the rabbi of Kruly in 5686 (1926). His brother the author of Atzei Chaim died that year, and he became leader of the community from that time. His Hassidim and followers continued to grow and reached 2,000, especially after he was appointed as the rabbi of Szatmar. His influence was similarly great in the communal life of Transylvania, and he was one of the leaders of organized Orthodoxy in the country. He settled in Jerusalem after the war. He moved his court to Brooklyn after a few years. Later, he was chosen as the rabbi of the Eda Hacharedit in Jerusalem. He was one of the leaders of Orthodox Judaism, with myriads following the word of his mouth. Even though not all of them followed his style, and there were differences of opinion between him and the rest of the rabbis of Israel, they all admitted that he was a holy and sublime person. He struggled valiantly against Zionism, and wrote books against Zionism and the State of Israel. He was the only one who wrote books of this type. In Vayoel Moshe he explains his opinion against the founding of the State of Israel. Following the

[Page 11]

Six Day War, he published his book “Al Hageula VeAl Hatemura” (On the Redemption and on the Change) with the intention of weakening the deep influence that was created in the world as a result of the great victory of the State of Israel against the Arab countries. He did this out of fear that the victory would strengthen the tendency to Zionism. He established Torah institutions and Yeshivas in the United States and Israel, which educate thousands of students. He died on the 26th of Av, 5679 (1979) at the age of 93. After his death, the mantle of leadership returned to its original source. Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum, the son of the author of Atzei Chaim of Sziget was chosen to replace him.

|

|

of holy blessed memory |

[Page 11]

B. Rabbinical Judges and Preachers

One of the first rabbinical judges in Sziget was Rabbi Chaim Meir the son of Reb Aharon HaKohen Traub. He was born in Dilyatyn, Galicia around the year 5520 (1760). He married the daughter of the wealthy man Rabbi Mordechai Stern of Sălişte. Through the influence of his father-in-law, he was accepted as a rabbi in Sziget in the year 5554 (1794) for the salary of 100 guilder per year. His wife died in the year 5560 (1800), and he returned to his birthplace. He returned to Sziget after several years. Apparently, he did not serve in any official role, even though he certainly acted as a Posek [rabbinic decider, adjudicator] to those who turned to him. (The text on his gravestone is as follows: “The eminent Torah scholar, an old man sated with days, who was constantly involved in Torah”, and does not mention that he served as a judge.) He died on the 13th of Kislev, 5602 (1841).

Rabbi Yosef Mordechai Kahana the son of Rabbi Yehuda HaKohen Heller. His father, the author of Kuntres Hasfeikot, wished to bestow upon him the rabbinate of Sziget as an inheritance, but he did not accept it. Unlike his father who did not identify with Hassidism, Rabbi Yosef Mordechai Kahana was an enthusiastic Hassid of Kosow who cleaved to his Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel the author of Ahavat Shalom. When he felt that his end was near, he traveled to Kosow and lived in the home of Rabbi Chaim the author of Torat Chaim. He died there on the 2nd of Adar 5594 (1834).

Another son of the author of Kuntres Hasfeikot, Rabbi Nachman Kahana, also served as a judge in Sziget. We know no additional information about him, nor the date of his death.

Rabbi Chaim Zeev Auerbach was a rabbinical teacher in Sziget. The sole source for this is the responsum Maamar Mordechai section 28 from the year 5612 (1872): “The eminent, sharp and brilliant rabbi… a teachers of the ways of the Torah, Rabbi Chaim Zeev Auerbach, may he live, of the community of Sziget Máramaros in the country of Hagar [Hungary]. The question dealt with the following: “Several times the issue came before him regarding the matter of sour dough and dough from which challa had not been taken that became mixed with dough from which challa had been taken[[11]].” We have no other details about him.

Rabbi Tzvi Aryeh the son of Reb Eliezer (family name Lachs?) was a judge and shochet in Sziget. He died on 22 Cheshvan 5621 (1860) when he was only 46. His son-in-law Rabbi Yitzchak Aharon Schwartz, the head of the shochtim in Sziget, published his book: Imrei Bina on the Song of Songs, Sziget 5657 (1897), 105 pages. The work is in homiletic and Kabalistic style.

Rabbi Chaim Shmuel the son of Rabbi Yosef Stern attempted to distance himself from the rabbinate because he shied away from all controversy, especially in light of what had happened to his father who suffered anguish and tribulation from controversy throughout his entire life. Later he answered the request of his friends the Hassidim of Kosow, and accepted a position as rabbinical judge in Sziget. He was born in the year 5580 (1820). His house served as a kloiz [synagogue, prayer house] for the Hassidim of Kosow. He died in the year 5653 (1893).

The most fruitful author in Sziget was the judge, and later head of the rabbinical court, Rabbi Shlomo Leib the son of Reb Pesach Tzvi Tabak. He father was a simple, God fearing Jew. He was born in the year 5692 (1832). He left the city at a young age to go to a place of Torah. He studied with the Yitav Leiv in Gorlice, Rabbi Avraham Yehuda HaKohen Schwartz the author of Kol Aryeh. He studied in the Yeshiva of Rabbi Yehuda Modron when he returned to Sziget. His first wife was the daughter of Reb Mordechai Yisrael the wealthy man of Kriva, who was known as Moti Kriver. She died on 29 Kislev, 5635 (1875). His second wife was the daughter of the aforementioned judge Rabbi Tzvi Aryehh. In the year 5618 (1858), when his rabbi the Yitav Leiv came to Sziget, he appointed him as a rabbinical judge. He was one of the geonim [great scholars] of the country, and authored books on a variety of topics. His renown extended beyond the country. The Gaon of Chrozan wrote in his approbation “I already have heard the depth of his greatness, diligence and fear of Heaven”. In the book Erech Shai on Choshen Mishpat, he wrote in his approbation, “In our generation, we have seen very few such wonderful compositions as this… and not many are as intelligent as he”. Reb Shlomo Leib Tabak died on 11 Tevet 5668 (1908). His Responsa books are in the brief style of the earlier rabbis, and they serve as a firm foundation for rabbinic decisions on monetary matters in particular.

Some of his books published during his life:

Erech Shai on Choshen Mishpat, Sziget 5652 (1892). [1] 165 [8] pages.

Erech Shai on Yoreh Deah, Sziget 5657 (1897). [2] 109 [1] pages.

The Responsa book Temurat Shai on the four sections of the Code of Jewish Law, Sziget 5665, 2, 224 pages.

[Page 12]

The names of the questioners were omitted, and the dates that the responses were written are removed.

All of his books that were published in his lifetime state in their prefaces: “Published through efforts of my dear son, the scholar and renowned wealthy man Shalom, may he live, who lives in Slasovia.

The following were published after his death:

Erech Shai on Orach Chaim, Sziget 5669 (1909). [2] 162 pages.

Erech Shai on Even Haezer Volumes 1 and 2. Sziget 5669. 179; 108 pages.

Erech Shai on Chidushim (new interpretations) of the Talmud. Sziget 5670 (1910). 108 pages.

The Responsa Teshurat Shai second edition, on the four sections of the Code of Jewish Law. Sziget 5670. 102 pages.

Erech Shai on the Torah. Volume 1. Bereshit and Shemot. Sziget 5672. 122 pages. Volume 2 on Vayikra, Bamidbar, Devarim. Seini, 5688 (1928). [2], 167 [2] pages.

Erech Shai on the Prophets, Ketuvim (Hagiographa) and the Five Scrolls (Megillot). Seini 5692 (1932). [2], 69, [1] pages.

All the books of Rabbi Sh. Y. Tabak were published again in photocopy.

Four of his responsa were published in the Responsa of Tiferet Adam, first edition. Sections 25, 71, 72, 75.

Lastly, his descendents published two volumes of Erech Shai, chidushim (new commentaries) on the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, a collection from his many books. Responsa Erech Shai on the four sections of the Code of Jewish Law, edited and compiled by his grandson Rabbi David the son of Matityahu Appel.

Another descendent of the author of Kuntres Hasfeikot was the renowned judge Rabbi Chaim Aryeh the son of Rabbi Yechiel Tzvi Kahana the son of Rabbi Yosef Mordechai the author of Kuntres Hasfeikot. He married the daughter of Rabbi Tzvi the head of the rabbinical court of Dilyatin in Galicia. His name became known in halachic circles with the publication of his book Divrei Geonim, and wrote a very useful anthology of the laws of Choshen Mishpat organized alphabetically. He used books which were very rare and which could almost not be found in our regions, most of them from the sages of Spain and the east. After the publication of his book, he was appointed as the judge in Sziget by Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum. He was faithful to him throughout his life. When Rabbi Ch. Y. L. Teitelbaum required the permission of 100 rabbis in the year 5637 (1887) to marry his second wife, Rabbi Chaim Aryeh Kahana was asked by the author of the Yitav Leiv to take care of the matter (see later in the list of responsa to him). However, after the death of the Yitav Leiv, he had a dispute with his son the Kedushat Yomtov regarding the rabbinate of Spinka. The Jews of that region seceded from the region of Sziget and accepted Rabbi Nachman Kahana the son of Rabbi Chaim Aryeh as the rabbi of their community. At the time of the great dispute and the secession of the Sephardim, he took the side of those that seceded, as did most of the members of the Kahana family. From that time, his soul had no peace. By nature, he was modest and retiring, as he testified about himself, “I am very discrete, and it is not my way to seek greatness, for I recognize the lowliness of my worth.” He never ate from meat slaughtered by the Sephardic shochet. Rabbi Chaim Aryeh Kahana died on 9 Shvat (according to Rabbi Y. Y. Greenwald, but on 29 Shvat according to N. Ben Menachem) 5677 (1917).

His book was published during his lifetime in three editions:

The Book Divrei Geonim. Ungvar 5630 (1870), 134 pages.

Second edition with many honorable additions that add to the main theme. Sziget 5661 (1901). [4]. 210 pages.

Third edition with few additions. Sziget 5671 (1911)

Published by photocopy: Brooklyn (5729? – 1969?), Jerusalem 5730 – 1970).

Responsa to him:

Responsa Beit Shlomo (his brother-in-law) on Yoreh Deah, volume 2, section 11 from the year 5630 (1870): Regarding a contract of business dealings; Choshen Mishpat section 87 from the year 5629: “I put my eyes upon the sections in his composition [Divrei Geonim] and I saw that he did well in collecting several necessary laws from the responsa of the Sephardic scholars which are not found at all, and I myself have never seen before.”

Responsa Tuv Taam Vadaat third edition, volume 1, section 175. “Even though I did not know him before, his words of Torah come to practical application.” A responsum in the matter of milk and meat. Ibid. volume 2, section 25. Regarding the laws of Passover.

Responsa Beit Yitzchak Yoreh Deah volume 2 section 64 form the year 5636 (1876): “Regarding a certain scholar who was living with his wife… if he can be allowed to divorce her against her will, or… with the permission of 100 rabbis…”; ibid. section 72 from the year 5644 (1884): “Regarding a rabbi who occupied the rabbinical seat for many years, and many towns were under his jurisdiction…the rabbi passed away and left a son who took his place, and the people of one town accepted their own rabbi, claiming that the town was two parsaot [2 parasangs = about 8 miles] away from the city… the son of the rabbi should have no complaint against them”; ibid. section 73 from the year 5649, “In one community, the head of the community refused to pay the appropriate salary to the rabbi, claiming that the money was not available, if the rabbi can detain the slaughtered meat of the shochet and prohibit it if the money cannot be found.” After discussion back and forth he concludes: “It is obvious that the rabbi can fire him and prohibit meat slaughtered by him… provided he acts with the agreement of the local court of law, so that no malicious rumors start about the rabbi.” Despite the fact that in the three responsa of the Beit Yitzchak, the names of the people and places were omitted, there is no doubt that the first question deals with the divorce of Rabbi Ch. Y. L. Teitelbaum, the second deals with the Rabbi Nachman Kahana (the son of the questioner) accepting the rabbinate of Spinka, and the third deals with detaining the salary of Rabbi Nachman in Spinka [See the following questions and responsa that contain clearer hints about these three issues].

Responsa Kol Aryeh section 65 from the year 5637 (1877): “I was afraid to express my opinion on such a great matter [here the entire matter is discussed at length without specifying any names]… but I cannot refuse on account of the honor of the Gaon and Tzadik of Sziget, may he live long…Nevertheless, the permission of 100 rabbis is certainly required for I saw the response of the rabbi and Gaon from Harmilov may he live, in which he sees it as an easy matter to divorce her against her will.”

Responsa Dvar Moshe 3rd edition, section 28: “I asked him… along with a letter from the honorable rabbi and Gaon Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum may he live… regarding a certain rabbi who married the daughter of the rabbi from a certain town, and they were together for 23 years… and he wished to fulfil the commandment of being fruitful and multiplying… he also set before me that which the great Gaon Rabbi Moshe Shick, the head of the rabbinical court of Chust, said regarding this.” In his conclusion, he requires the permission of 100 rabbis.

Responsa Mahar”ia HaLevi volume 1, section 66 from the year 5637 (1877): “Regarding a certain great rabbi who married the daughter of great people, and they lived together for 23 years and did not merit to have surviving offspring… and both of them traveled to the holy Gaon of Tzanz who commanded that they wait another year and a half, and wrote an agreement between them… in front of two witnesses… in the month of Tevet 5638 (1878), the end of the time set by the Gaon of Tzanz, the husband wished to issue a Get to her… and she did not want to accept it, so she went away from her husband and went to her family… I also agree with the words of M”akhat to permit him to marry after the permission of 100 rabbis is issued as per tradition.”

Responsa Sheelat Shalom second edition section 63: “Once again regarding a great rabbi from a certain city, “As opposed to the preceding rabbis, Rabbi Shalom Taubish opposes the permission of 100 rabbis; ibid. section 276. “Regarding a rabbi who dwelt in one city for many years as the rabbi, and many towns were subordinate to him which agreed to pay him a set amount every year… now the rabbi has died and left a son to fill his place…and the people of one town hired a rabbi to teach and judge them, claiming that their town is approximately 2 parasangs distant from the city, and it is difficult to send someone into the city to ask their questions… the matter is obvious to me that the son of the rabbi does not have the power…”

Responsa Harei Besamim second edition section 240 from the year 5649 (1889):

[Page 13]

“regarding a rabbi whose salary has not been paid for several months… if the shochet does not support the words of the rabbi in this matter…he can prohibit his slaughtered meat.”

Responsa Chaim Shel Shalom volume 1 section 54: “Regarding the son of the rabbi may he live in the community of Spinka who was accepted by the residents of that town for some years, and they raised him up and made him their rabbi for a set weekly salary… and now some weeks have passed from when they called an assembly and were not able to pay him his salary upon which he depends…”

Responsa Shaarei Binyamin section 33: “The son of the rabbi may he live receives his salary from the communal budget… and now they have stopped paying him, and he asked the shochet to no longer slaughter without his permission unless they pay him his salary.”

Responsa Maharsham volume 7 section 178 from the year 5661 (1901): “Regarding someone who had purchased a garden with many trees ten years ago, and now they have stopped producing fruit, is he allowed to cut them down?”

Rabbi Meir David Tabak the son of Rabbi Shlomo Yehuda the author of Erech Shai served as a judge in Karachinov for decades. After the death of his father, he was chosen to take his place as the head of the rabbinical court of Sziget. He was also a known scholar in the city and area. Memory of him has diminished since he never published his books. He died on 2 Nissan 5696 (1936) at the age of about 90.

Two responsa to him were published in Responsa books, both from the era of Karachinov.

The son-in-law of the author of the Erech Shai, Rabbi Shlomo Dov Heller, was appointed as a judge in Sziget during the life of his father-in-law (and later the head of the rabbinical court). According to a notice in the Orthodox newspaper in Budapest “Algemeine Yiddishe Zeitung” (1900, issue 8), Rabbi Sh. D. Heller was appointed as judge and director of the metrical (list of births and deaths) in the year 5660 (1900). It seems that aside from his greatness in Torah, he also had some secular knowledge. He probably attained his knowledge in autodidactic manner, for the Hungarian government would not have agreed to give over the management of the Jewish population registry to someone without minimal education. During his 44 years of service, Rabbi Sh. D. Heller stood out as one of the great scholars of the country. He was especially strong in Choshen Mishpat[[12]]. He was called to mediate and sit at the head of the courts throughout the country when disputes and arguments broke out between communities or individuals. However, no printed works from him remain. He perished in Auschwitz on 25 Iyar 5704 (1944).

A responsum from him is published in the book Chemdat Shaul section 62 from the year 5693 (1933) that was written to his son-in-law Rabbi Amram Rosenberg the head of the rabbinical court of Ratzfert.

Responsa to him:

Responsa Atzei Chaim on Orach Chaim section 17: “I saw his letter in which he disputed at length about matters of an electric light bulb on the Sabbath. Disputations from a friend are acceptable to me. However, I said something and I stand by it, for I believed that I was right.”

Responsa Mahara”sh Engel volume 5 section 76 from the year 5684 (1924): regarding the changing of the name in a Get (bill of divorce); ibid. volume 8 section 3 from the year 5683 (1923) regarding an aguna whose husband fell during First World War.

It is mentioned above that the author of Atzei Chaim, rabbi of Berbeşti Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Gross, was invited to Sziget and appointed as a judge. Already during the years of his youth he performed the rabbinical roles. First and foremost, he directed the Yeshiva. He organized it with new foundations after it disbanded with the death of the rabbi. He instituted something new that did not exist in any Yeshiva in the country: he set up a weaving facility next to the Yeshiva so that the students could acquire a trade with which to earn a livelihood. Later, a similar Yeshiva was founded in the town of Iclod near Klausenburg (Cluj), where furniture making was taught. Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Gross also perished in the Holocaust.

Several responsa were written to him, but all were from the period that he lived in Berbeşti.

Rabbi Yosef Bek was another judge who died during the Holocaust. He was the son-in-law of Rabbi Meir David Tabak.

Rabbi Yosef Shmuel Halevi Berger also lived in Sziget between the two world wars. He was known as the Magid Mesharim and disseminator of Torah. Four responsa were written to him by Rabbi Alter Shaul Pfeffer of Biskov, who is a rabbi in New York.

Responsa Avnei Zikaron volume 1 section 77 from the year 5681 (1921); chidushim (new interpretations) on the Torah and questions and answers explaining various Talmudic discussions; volume 2 section 41 from the year 5684 (1924) and section 42 that deal with the practical laws of Nidda (menstrual separation); ibid. section 43: after novel ideas on the Torah it is stated, “Here I find place to thank him… since he opened the mysteries of the Torah in the Avnei Zikaron responsa that were published in Macha”k, and in some places he added corrections with his great intellect. I come here to discuss the precious words.”

The rabbi and preacher of the Talmud Torah Synagogue in Sziget was Rabbi Yaakov the son of Rabbi Naftali Greenwald (the father of the historian Reb Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald), the prime and beloved student of the author of the Arugat Habosem. He sold books to earn a livelihood. He died on 15 Shvat 5688 (1928).

He published one work:

The Chelek Yaakov book on Pirke Avot (Chapters of the Fathers), and at the end of the book it includes the booklet Al Techetu Layeled (Don't sin against the child) dealing with the education of children, and the booklet Shoneh Halachot. Seini 5683 (1923) [4] 68 pages.

Responsa to him:

Responsa Pnei Meivin on Yoreh Deah section 11: “About what I attained through what was written on my work on Orach Chaim…”

Responsa Zichron Yehuda volume 1, section 135: Chidushim (new interpretations) on Torah. Volume 2 sections 151 and 152. Chidushim on Torah. “I am embarrassed that I did not respond until this time… and now… his son our student comes here… Rabbi Avigdor may he live. Therefore I hasten to answer immediately.”

Responsa Atzei Chaim on Choshen Mishpat section 9: “A Torah scholar and eminent Hassid”. Regarding someone who encroaches on the livelihood of his fellow and a pauper looking for crumbs. Responsa Afarkasta Deanya section 9: “My friend the rabbi and Gaon, pious and upright, faithful to his G-d.” Chidushim on the Torah.

Responsa Ginzei Yosef section 117: “The great rabbi, renowned and praiseworthy”. Responsa on the Torah.

When Rabbi Yaakov Greenwald died, his son Rabbi Avigdor Greenwald took his place both as a preacher and as a book merchant. He was also a gifted preacher from whose mouth dropped pearls. He was graced with pedagogical talents, and even wrote a book on that subject. He perished in Auschwitz with the martyrs of Sziget on 25 Iyar 5704 (1944).

His works:

The Keter Torah book on the 613 commandments of the Torah and 7 rabbinical commandments… At the beginning of them, I copied the words of the Chinuch[[13]]. I added a bit of my own personal commentary. Warsaw 5693 (1933). 26, 87, 185 pages. The book is in Yiddish, and the 613 commandments are in Hebrew.

Published by photocopy: New York 5720 (1962), Jerusalem 5733 (1973).

Responsa to him:

Responsa Pri Sadeh volume 2, section 116 from the year 5668 (1908): “Regarding the issue that there are people who divine with witchcraft by means of the asker placing lead or wax in a pot or pan on the fire. A form in the shape of a human rises from the wax from whom he asks about the future, or if something is permitted in a certain manner.

[Page 14]

Responsa Vayitzbor Yosef section 83 from the year 5693 (1933): Chidushim [new interpretations] on the Torah and discussions.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel the son of Yosef Shlomo Eckstein. He was born in the year 5644 (1884) in Sziget, where he served as a preacher. Later he served in the town of Krosno in the region of Silaj. His father was Rabbi Yitzchak Izak the son of Rabbi Elimelech Eckstein the head of the rabbinical court of Dukla, Galicia. Rabbi Elimelech Eckstein was the son of the sister of Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech Shapiro of Dinow the author of Bnei Yissachar. Rabbi M. M. Eckstein was the student of the author of the Arugat Habosem. He immigrated to the United States after the First World War and served as a rabbi in Cleveland and New York. He was an avid book collector. He published two small works, one in Sziget, and one when he was living in the United States. He died there.

Sefer Yetzira. Includes all places in the Talmud, the early rabbis and the later rabbis where the topic of creating through the Book of Creation (Sefer Yetzira) is mentioned, and to determine if the stories of the wonders of the Maharal were true. This was attributed to Rabbi Yitzchak Katz. Sziget 5670 (1910). 15, [1] pages. Against Rabbi Yehuda Yudel Rosenberg and his book on the wonders of the Maharal.

Kuntres Bechi Tamrurim (the booklet on bitter weeping)… The lamentation about which I discussed… On 11 Iyar 5686 (1926), here in the synagogue Eitz Chaim, Men of Hungary in the city of New York… on the passing of the rabbi… Rabbi Hillel HaKohen who is known as Dr. Klein of holy blessed memory. Torna Slovakia 5689 (1929). Only 50 copies printed.

On page 15: “I cannot refrain here from mentioning the death of the righteous Gaon Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum of holy blessed memory, the head of the rabbinical court of Sziget in the new state of Romania. I was one of his friends who frequented his home. Even here in the United States I received letters from him filled with friendship and love. He died suddenly at the age of 46…”

A responsum to him in the Avnei Zikaron Responsa volume 2, section 47 from the year 5689 (1929) when he was living in the United States.