|

|

|

The Years of the Town's Decline

On Saturday, the first of April 1933, Kibart Jews who went to Eydtkuhnen as usual, were surprised to see a uniformed S.A. man in front of each Jewish shop, who prevented them from entering. This was the beginning of the end of German Jews, and for that matter, of East European Jewry too, but on that day people did not as yet imagine to what this would lead and how it would end.

During the following years traffic through this border passage decreased gradually, because most of the Kibart's Jews abstained from going to Eydtkuhnen, very few would cross the border. At the railway station the traffic also decreased a lot, only groups of “Khalutzim” would pass the station from time to time on their way to Eretz–Israel. In the luxurious rooms of the station, once upon a time designated for the Tsars family, the Magistrate's Court was now housed and the only persons frequenting these rooms were those who came to be judged or just curious onlookers.

In the long building near the border where there were at one time 15 shops, only two were left, of all the others only the signs remained. A few carts would pass the border during the day, carrying some goods for processing by those few “Expediters” still in Kibart.

Those merchants whose business was not based on the population of Eydtkuhnen or on smuggling, continued as usual. The same was true of the factories and workshops who produced for the local market.

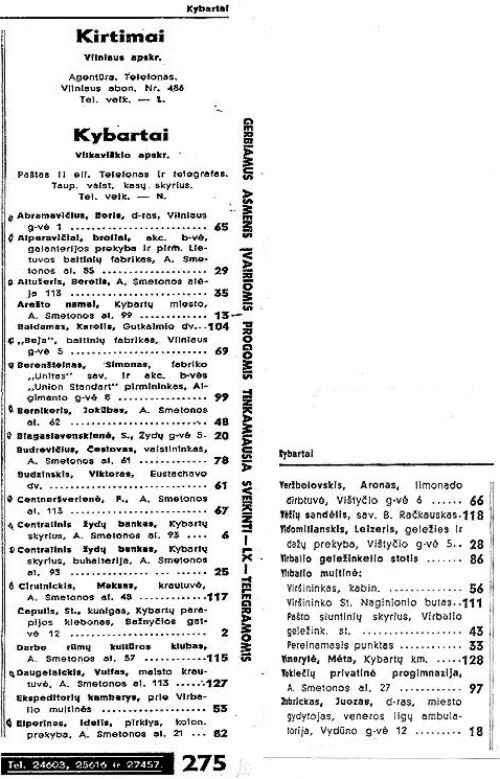

According to the official 1940 telephone book there were 123 phone subscribers in Kibart, of whom about 36 belonged to state institutions such as the police, border police, customs, courts etc. Of the other 87 subscribers 51 (59%) belonged to Jewish owners of the large shops, the manufacturers and the expediters (see tables 19 and 19a below).

[Page 204]

|

[Page 205]

|

In those years the influence of the Lithuanian Merchants Association (Verslas), who propagated the boycott of Jewish shops and to buy only “Lithuanian” (Lithuania for Lithuanians) increased. Slowly but surely this propaganda gained popularity among wider circles and Jewish shops were avoided. As a result not only did many Jewish families leave the town and to look for a livelihood elsewhere, but many young people did so too, in order to find work in Kovno.

[Page 206]

In 1937 or 1938 the well known “story” of the geese occurred and this is the time to relate it:

Lithuania's main export items were agricultural products, most of them to Germany, one of the major items being live geese. At the beginning of winter, the exporters would bring the geese to a lot in the railway station. The quacking of the geese was heard day and night during a month or so. The geese or a part of them were transferred across the border by foot and a white throng of geese could be seen flowing along the main street to the border. When Hitler's rule in Germany had become a fact, he demanded that Memel (Klaipeda) and its districts return to German sovereignty. By way of pressure he cancelled the commercial treaty with Lithuania, as a result of which all the geese assigned for export were left without buyers. To solve the problem, the Lithuanian government ordered that all its clerks receive part of their salary in geese. The amount of geese for every clerk was calculated according to his salary. Thus the price of geese greatly decreased and many people enjoyed roast geese and geese schmaltz.

In order to illustrate the image and decline of the town mention is made here of several excerpts from an article written by the writer David Umru which was published in the Yiddish newspaper “Folksblat” in July 1939: “Eydtkuhnen made a living from Kibart and Kibart from Eydtkuhnen.” Today both towns have declined in comparison to their living standards in recent times. Kibart is different from all other Lithuanian towns. Not only the grandiose railway station but also the other buildings look similar to a large city. The columns of trees along the sidewalks, the lawns and also the behavior of its people are not provincial. Kibart is imbued with western culture. Even the door frames of the shops are a copy of German examples...

Now there is a struggle with the so–called “German disease.” Girls, who not long ago only knew German, opened their mouths and began to speak a fluent Yiddish. Library workers used the opportunity and started to mobilize new subscribers, and if you paid the Lit, so why not to take a book? Then having taken a book, you read a little and even started to feel the taste of it.

The public institutions in Kibart are successful. The activities of the “OZE” and “ORT” organizations are not comparable to that of any other town in Lithuania. Ten youngsters were sent to the “ORT” vocational schools in Kovno financed by the community. Preventive medicine of “OZE” is also on a high level. The only association which is lacking is one which would cause cultural activity to advance to a proper level.

Once there were factories in Kibart. Today there are no factories left, only poverty. About ten men are still “Couriers” who travel to Kovno every day, taking some smuggled goods with them to sell there in order to add some income to their poor livelihood. But in the street poverty is almost unnoticeable. It is well hidden as is appropriate for a town with an “outward shine”.

[Page 207]

In spite of the fact that the situation was deteriorating all the time, it is worthwhile mentioning the help Kibart's Jews gave to refugees from the Suvalk region at the end of 1939.

According to the Ribbentrop–Molotov treaty the Russians occupied the Suvalk region, but after surveying the exact borders according to which Poland was carved up between Russia and Germany, the Suvalk region fell into German hands. The retreating Russians allowed anyone who so wanted to join them and to move into the territory occupied by them, and indeed many young people left this area together with the Russians. The Germans then expelled from their houses those Jews who remained in Suvalk and its vicinity, their property was robbed, after which they were led to the Lithuanian border, where they were left in great poverty. The Lithuanians did not allow them to enter Lithuania and the Germans did not allow them to go back. Thus they stayed there in this swampy area in cold and rain for several weeks, until Jewish youngsters from border villages in Lithuania smuggled them into Lithuania by different routes, with much risk to themselves. Altogether about 2,400 refugees were passed through or infiltrated by themselves, and were then dispersed in the Vilkavishk and Mariampol districts. In Kibart alone 125 refugees were accommodated, among them several tens of “Khalutsim”, who got the warm and devoted treatment for which Kibart's Jews were famous.

Under Soviet Rule

In June 1940 Lithuania was annexed by the Soviet Union and became a Soviet Republic. The president of the Lithuanian state Smetona together with many of his friends, escaped to Germany via Kibart.

A border guard unit of the Red Army arrived in Kibart and was put up in the buildings of the railway workers at the corner of Vishtinetz (Vistycio) street. Russian soldiers stormed the shops, buying everything they saw. Goods lying in the storerooms without use were brought into the shops and sold for good money.

At the end of July the banks were nationalized and deposits frozen. At first one was allowed to draw 1,000 Ruble per month per family, later this sum were gradually reduced to 250 Ruble. Then those industries for which the following criteria applied were nationalized, i.e. “ a factory which employs more than 20 workers or a factory where a minimum of 10 workers are employed, which uses mechanical power and whose products are important for some other factory.”

In Kibart most of the Jewish factories were nationalized, commissars installed and appointed as their directors. These were communists who had been freed from jails or those who had been active in the communist underground, among them several local Jews. At the beginning of August commissars were appointed to such shops as Shadkhanovitz, Seinensky and others, whose annual turnover was more than 150,000 Lit.

[Page 208]

The owners of the factories and shops became clerks and salesmen in their own enterprises, being responsible to the commissars who kept the keys of the enterprises and kept hold of the cash.

Since they had no managing experience, they were helped by the former owners during the year of Soviet rule before the war.

Russian single officers and officers' families of the border guard were accommodated in private flats in the nicer buildings, where mostly Jewish families were living.

The supply of goods diminished and as a result prices gradually rose. The middle class, mostly Jewish, was badly hurt and its living standard decreased gradually, also wage earners hardly made a living.

During the school year of 1940/41 the Hebrew school became a Jewish school, with Yiddish as the teaching language. Its headmaster A.Varshavsky was dismissed and sent to Kupishok as a teacher, and the school was now directed by teachers Sheine Halperin and Mordehai Lurie. The Zionist Youth Organizations were dispersed and the Comsomol – the Communist Youth Organization – started to mobilize new members. (see Kibart Jewish Kindergarten on the occasion of Chanukah celebration in 1940 in photograph below).

Some “Shaulists” – a nationalist Lithuanian organization of ex– army soldiers – and among them some Zionist activists, were arrested, as were some Jewish traders in foreign currency and also people who had been slandered for different wrong doings.

A tense and fearful atmosphere prevailed and people were afraid of what the morrow would bring. Add to that the rumors, which were spread deliberately, that after the division of Poland between Russia and Germany in accordance with the Ribbentrop–Molotov treaty, Lithuania too would be divided, with Kibart and its environs being annexed by Germany.

According to this treaty all Germans without any exception, who until then lived in Lithuania, were repatriated, and since many Germans lived in Kibart and its surroundings their departure added to the tense atmosphere.

In the middle of June 1941, the authorities started to send families of owners of the nationalized factories, shops and houses, also those suspected of Zionist activity, to exile deep in the USSR. Only a few hours notice was given, during which those doomed to exile had to pack their belongings which were limited in quantity, and were then taken to the freight wagons.

From Kibart Hayim Miltz with his wife and daughter, Michael Shadkhanovitz, his wife and son, Yisrael Rakhlin, his wife, his mother and his little son and daughter, Berniker and his wife and two sons, were exiled.

Broadcasts from the B.B.C. in London about the “Eastern Front” and news about the concentration of the German army along the borders of the USSR, did not have a strong enough impact among Kibart's Jews to make them take their belongings and escape away from the German border as far as possible.

[Page 209]

One could possible explain this state of mind by the tense atmosphere and the uncertainty which paralyzed any ability to decide. In addition there was the strong belief in the might of the Red Army which propaganda had managed to be implanted in the minds of most Jews.

|

|

|

|

Kibart Jewish Kindergarten–Khanukah 1940 The third from left in the first line above– Shne'ur Rakhlin |

[Page 210]

German Occupation and Destruction of the Jewish Community

On June 22, 1941, between 4 and 5 o'clock in the morning, the German army entered Kibart without any real resistance. Only a group of soldiers from the Russian Border Guard fortified themselves in the cellar of the mayor's building and fought to the last man.

The Germans freed all prisoners from jail, among them those accused of resistance to Soviet rule. They immediately started to organize local groups in order to take revenge on the communists and the Jews and also to help the Germans impose order and rehabilitate civilian life. The head of the Lithuanian activists who put themselves under German control was the Doctor Zubrickas, who had arrived in Kibart in 1933, had been active in the Lithuanian nationalist organizations, as a result of which the Soviets had imprisoned him.

During the first days of occupation the German army ruled and did not take any measures against Jews. There were even cases of German authorities helping Jews to get back some property previously robbed by Lithuanians, with Jewish girls serving as interpreters in Eydtkuhnen.

But after several days the Civil Administration was established and one of its first orders was to limit the rights of the Jews. The spokesman of the municipality passed through the streets and with the help of a bell assembled the crowd to read them this order:

According to this method, which was, as became clear later on, identical everywhere, all the intelligentsia were detained first and transferred to the Gestapo in Eydtkuhnen. It became known, that when the lawyer Jehoshua

[Page 211]

Lurie was detained and transferred to Eydtkuhnen, his wife with their little blond daughter came to the commander of the S.S. and asked him to release her father. He was freed indeed but only for a short time, because a few days later he was murdered together with all the Jewish men of Kibart.

Kibart was situated in a strip 25 km wide from the border with Germany, where Stahlecker had ordered the Gestapo of Tilzit to exterminate all Jews. The head of the Gestapo in Tilzit, Hans Joachim Boehme, contacted the Gestapo and the Border Guard in Eydtkuhnen in order to determine the date and all other details for the murder of the men in Kibart. The execution of this murder was to be an example for the Gestapo man from Eydtkuhnen, Tietz, who was in charge there and who was nominated to execute such murders in the future. (Tietz committed suicide later). The Lithuanian police too was informed about the date of the “operation”. Their part was to detain the men, to assemble them and to act as guards, conveyors and executors.

At the beginning of July all Jewish men and youngsters above 16 were taken from their homes and concentrated in a barn in the farm of Baldamas in the village Gudkaimis, about 6 km north of Kibart. There they were ill treated, left without food and water for several days and forced to dig holes in the nearby sand quarry of Peskines.

During the night of Sunday, July 6, 1941, all were shot at the edge of the holes they had dug for themselves, after having been forced to hand over all their belongings and to take off their upper clothing. 185 Jews and 15 Lithuanians, activists under previous Soviet rule, were shot that night. A monument in memory of the victims was erected at the mass graves several years ago. (see picture).

Apparently the only Jew who was in that barn and heard everything, was Benjamin Jasven, the owner of a sewing workshop of men's shirts in Kibart named “BeJa”. He managed to hide and 12 days later arrived in the Kovno Ghetto. He managed to survive the 3 years of German rule in Kovno and after the liquidation of the Ghetto he was sent to the concentration camp of Dachau. After he survived Dachau he delivered his testimony to “The Committee for investigation of the crimes of the Nazis and their Lithuanian helpers” in 1947 in Munich.

The head of the Lithuanian gang who took part in the murder was the above mentioned Doctor Zubrickas. Other murderers were the Border Guard policeman Betinas, the policeman Zaganevicius, a German repatriate who returned to Lithuania named Lozovsky, the chief of the police Vailokaitis, the student Budrevicius – the son of the former mayor who was exiled to Siberia, the head of the agricultural society Orintas, and others.

After murdering the men and the youngsters, all women as well as the old and the children were concentrated in the red brick houses which had been emptied from Soviet soldiers. There they stayed for about a month and then all were transported, almost without any belongings, to the Ghetto in Virbalis.

[Page 212]

The Ghetto in Virbalis was established in the almost empty streets where the repatriated Germans had lived before. The head of the Ghetto was the only dentist in town, Mrs. Sheine Pauzisky, who used to mix with those Lithuanians who were also her patients and had good connections in the state and municipal institutions.

A special shop was opened in the Ghetto for the supply of food. The shopkeeper was a Lithuanian, an honest man, who took care to supply the required quantities of food to the Ghetto inhabitants.

All young women and children aged 12–16 would go to various types of work in the town and the vicinity. A quasi employment bureau was established in the Ghetto where unemployed people would come to look for work and also peasants from the vicinity who would select women and youngsters for work. Among the employers there were evil and cruel people who treated the women and children very badly, but there were also brave people who maintained relations with the Jews. There were even some who hid 10 Jewish women when the murders began, but of the few women only Bela Mirbukh and her mother from Virbalis survived after hiding for 3 years at the farm of a Lithuanian teacher near the town where Bela worked as an agricultural worker. Bela Rosenberg too, the young daughter of farm owners near the town, survived after being hidden somewhere in the vicinity.

After a short time, one night at the end of July or at the beginning of August, all old women, the sick and all those who were unemployed were taken from the Ghetto and conveyed to the anti–tank trenches, about 2 km north of the town, which the Russians had dug along the German border, where they were shot and buried.

After this “action” the authorities promised that nothing bad would happen to the Jews anymore and according to German methods of deception, the women were told that also their husbands were working in all sorts of jobs nearby. During this time, Lithuanians acquaintances and strangers would come and tell the women that they had seen their men and that they had asked for money, valuables or clothing, which the women would willingly hand over to them. These false requests increased from day to day and the women started to believe, wrongly of course, that maybe there was hope for them to see their beloved ones soon and even to join them. They believed what they wanted to believe and closed their ears to information about murder and extermination, which other women who worked outside told them.

Among the Lithuanian population there were rumors that the end of the rest of the Jews was near, but none came to warn them of this danger. The women lived with the illusion that they would join their husbands soon, baked, cooked and packed parcels. Then came the terrible day, Thursday September 11, 1941, the nineteenth of Elul 5701, when the Lithuanians arrived at night with carts, took all the women and children out to the anti–tank trenches and murdered them there in cold blood.

This was the tragic end of the Jewish Community of Kibart.

[Page 213]

In May 1987 the monument in memory of the communities of Kibart (Kibartai), Virbaln (Virbalis) and Pilvishok (Pilvishkis) was unveiled at the cemetery in Holon. Zisl Kovensky, David Shadkhanovitz, Frida Shtern–Rokhman and Berta Seinensky–Sheines initiated and completed this important project on behalf of the former Kibart Community.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The inscription says: |

[Page 214]

Written by Peretz Kliatchko, a native of Kibart

I lived in Kovno after the war and visited Kibart from time to time. I would walk along the streets and alleys and try to imagine the beloved pleasant town in which I had spent my happy childhood. I would stop beside houses and backyards and try to remember the names of the families who had lived in these houses. No Jews lived in Kibart after the war and of those who had lived there when the war began nobody had survived and I did not expect to meet any. I did not even meet Lithuanian acquaintances, because the battle front ended near Vilkavishk and the Germans evacuated the entire population from the front zone, including Kibart, to Germany. Exhausted and battered I would return to Kovno.

In 1960 my friend Dov Shtern, who was born in Kibart, and I went to Kibart in order to look for the mass graves. We knew that the men had been murdered in the sand quarries (Peskines) and so we went there. In nearby single houses nobody knew, or did not want to know, the exact site of the mass graves. The answers we usually received were that these people had been living there only since the war and therefore had no local knowledge, but we were under the impression that they were lying. Then we met a middle aged Lithuanian who asked us what we were looking for, and after we told him he said that he too was looking for the graves of the 15 Lithuanians, communists and activists of the trade unions from Kibart and vicinity, who were murdered together with the 185 Jewish men. He joined us and then he asked the questions. One woman pointed in the right direction saying that it was easy to locate the graves, because the grass on them was much greener than in the fields nearby. We found the place easily; it was not fenced, there were no signs, and cows were grazing in this field. With the exception of the different shades of the color of the grass, it looked like any other field. We stayed there, bowed down, and departed with much pain in our hearts.

Returning to Kovno I wrote a sharp letter of protest to the local authorities, demanding the repair of this terrible injustice. A year later, when we, Dov Shtern and myself, visited this place again we found it fenced off with barbed wire and in the middle there was a wooden sign with an inscription. Cows did not graze there any more.

At the end of the sixties I received information that a trial was to be held in Kovno of one of the criminals who had participated in the mass murder of Kibart's Jews. The trial was to be held in the upper Lithuanian court, in camera. The accused was a Lithuanian, the son of a former estate owner, who had hidden all the years until caught recently, but I have unfortunately forgotten his name. It turned out that another murderer, the former policeman Betinas, who had been sentenced to 25 years in prison, had been freed. According to the agreement between Chancellor Adenauer and Secretary Khrushchev all German prisoners, and some Lithuanians too, who did not take an active part in the murder of Soviet citizens, were freed from prisons and camps. Thus, many murderers, against whom there was no legal evidence

[Page 215]

available that they had actually shot innocent people, were freed. The Lithuanian murderer, who had been in hiding all these years, secretly met with that freed prisoner and concluded that he too was exempt from punishment, but this did not happen. He was detained, investigated, the mass graves were opened up and as a result a charge sheet was prepared and he had to stand trial.

After great efforts I managed to get an entrance permit to the court room. On arrival in court on the day of the trial, I met many old women in the corridor, apparently the wives or relatives of the 15 murdered Lithuanians. As is well known, there were no Jewish witnesses left.

Two soldiers, who took turns every hour, brought the accused into the hall, a tall blond man in his fifties, with fluttering eyes. The court consisted of three judges, a prosecutor and a defender. The prosecutor was a young man with red eyes and a plaster on his nose, apparently the result of a nightly spree. People looked at me in surprise, since apparently my appearance caused some confusion, but nobody asked me anything, because they understood that I had not entered under false pretenses. The judges, the prosecutor and the defense were all Lithuanians, only the soldiers were Russians and they did not understand anything about the trial, because it was conducted entirely in Lithuanian.

After the procedural part, the charge sheet was read, which said that the accused had volunteered to join a group of Lithuanian nationalists who detained all Jewish men in Kibart as well as 15 Lithuanian communists, brought them to a barn near the “Peskines” where they were tortured for a few days, left without any food or drink, and then were shot group by group. I remember that the murderer was asked how it happened that a young person was found amongst the skeletons, because only males above 16 years old were supposed to be killed. He told the court that the 14 year old daughter of the grocery owner Halperin arrived at the barn and did not want to be separated from her father even after she was threatened that she would be killed too, and so she was shot together with all the others. A stethoscope and a pouch embossed with the symbol of the Red Cross was found in the opened graves, “it belonged to the medic Sher” the murderer explained. He gave the court more details, which I have already forgotten.

The women witnesses told the court that the accused, together with several other evildoers, appeared on one night knocking loudly on doors and windows, and after shouting “where are the Bolsheviks?” forced the men to dress quickly, not allowing them to take anything with them. They were seated in carts and taken to the barn, where during the few days that they were kept there, the women were not allowed to approach or to bring them any food. One day a lot of shots were heard from there, during which all the approaches to this place were blocked, and when the women arrived on the next day they found an empty barn and covered graves. They also heard that the clothes of the victims, which they had been forced to remove before being shot, were divided up among the murderers.

[Page 216]

The accused claimed that he did not detain people and did not shoot, but that he, armed with a rifle, only transported them in groups to the holes. But the witnesses insisted that he arrested their husbands and one of them even said that his voice still rang in her ears and would never stop. The accused, when replying to the witness, maintained that his voice had changed during the years and she, as a devoted catholic, would surely have to give account of her testimony before a heavenly court and should therefore rethink her testimony. The woman crossed herself trembling and declared fearfully that maybe she was mistaken.

The prosecutor demanded maximum punishment, whereas the defense asked for an acquittal, because the accused had already suffered enough by hiding all these years, there being no proof that he himself had shot people and there was an amnesty for collaboration with the Germans. The speeches of the prosecution and the defence were monotonous as if this were a routine case, instead of being the trial of a murderer of 200 innocent people.

The trial ended with the verdict that the accused was guilty of murder, but taking into consideration that there was no proof that he himself had shot people and that there were no witnesses to this effect, he was sentenced to seven years in prison.

I looked at the murderer's face when sentence was pronounced and saw fear in his eyes on the verdict of guilty of murder, but when he heard the punishment was only seven years in prison his face lit up and he was satisfied. The sentence was final, with no possibility of appeal.

I left the hall confused and hurt, and for several days I could not find peace of mind nor was I able to sleep. Once again I was overcome by all the tragedy of Kibart and could not free myself from these feelings for a long time.

The Testimony of a Murderer

Vincas Gilinskas was born in 1914 to a wealthy farming family, and attended school for seven grades. In the summer of 1941 he served in the Kybartai police and was one of the participants in the murder of Jews in July 1941, for which he was sentenced. The following is his testimony.

(L.Y.A. (Special Lithuanian Archives) F.K–1. B. 191. P. 69–73)

The Kibart police force consisted of only eight policemen, among them 3 high school students.

In the beginning of July 1941, the chief of police Staugaitis ordered his men to prepare to collect the Jews quickly and bring them to the yard of the police station. The commanders of this action were four uniformed Germans, who spoke Lithuanian well.

When the first group of Jewish men were brought to the pit, one of the high school students shouted “Men, lets try!” Gilinskas did not raise his hand – he did not feel comfortable about it – after all, this was his first time. Nevertheless, getting up courage, he shot two people in the first group. When the

[Page 217]

second group was forced into the pit, there was a commotion: “ I recognized the Jew Milts, who fell at the feet of policeman Vailiukaitis, asking for mercy. I started to shake and kept away from the pit, giving my rifle back to the German, explaining that I have ‘some personal needs…’. I refused to take part in the shooting”. But after the executions, Gilinskas participated in covering people still living with earth.

Later Gilinskas got to know the real number of victims: “ In the chief's office, I accidentally saw a list of the Jewish men with their surnames, and the last number was 116”. There were only Jewish surnames on this list, although Lithuanians, Soviet activists, were also shot at this time.

In the autumn of 1941, women and children were murdered. In accordance with the chief's order, Kibart policemen rounded up about 250 women and children, which was not difficult as they all lived in one quarter of the town and the men had already been shot. Vilkovishk police chief Paukstaitis and his men arrived to help. The women and children were transferred to Virbaln on trucks. Gilinskas continues: “When Kibart and Virbaln women who knew each other met, terrible cries, shouts and groans were heard. As a result I became very uneasy, withdrew my hand and went out to town, saying that I had not slept all night and needed to eat. As I left, people had as yet not been shot, but I knew that they were destined to be murdered”. After some time Gilinskas returned to the murder site. He was drunk. Somebody gave him a rifle and he shot several times. “I did not know if I had convinced myself or whether somebody was pushing me, but I shot. After that I got two days detention, because of drinking during working time “. After the action the shooters ridiculed Gilinskas for breaking his vow, in addition to which he was transported half alive on a cart lying on bloody garments, and finally he even got some clothes. “Breaking his vow” meant that after the murder of the men in Kibart, Gilinskas had vowed not to shoot people anymore. It is a pity he did not fulfill his vow.

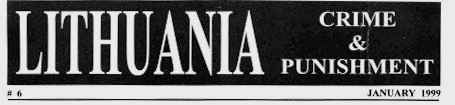

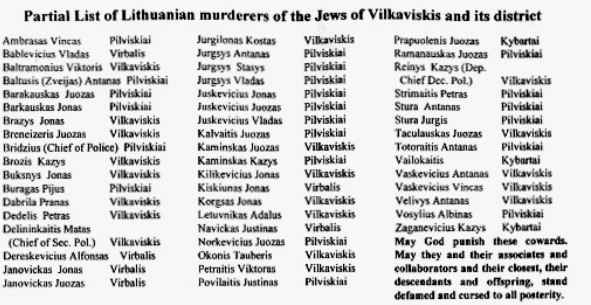

For a partial list of the Lithuanian murderers of Vilkavishk district see Appendix 2.

Written by David Shadkhanovitz, a native of Kibart

In June 1965, after returning from exile in Russia, I visited Kibart and Virbalis. I wanted to visit the graves of Kibart's martyrs who were murdered by the Nazis and their Lithuanian helpers. With great emotion and a trembling heart I went out in the direction of the Pieskines, where the first 200 victims were murdered. On my way there I tried to ascertain from local inhabitants where the exact place was, but all of them evaded answering, saying that they had been living there only for a short while. A Lithuanian woman from whom I bought flowers, agreed to point out the place of the murder. I found the place in accordance with her description, which was about 2.0–2.5 km eastwards from the railway station along a dust road. I found the graves surrounded by a wooden fence and a sign written in Lithuanian: “Passerby, stop and bow your

[Page 218]

head for the victims of fascist terror. In this place 200 Soviet citizens are buried, who were shot by German fascists”. I placed the flowers there, and with a bowed head said “Kadish”.

I returned to Kibart and from there I went to Virbalis in order to visit the graves of the remainder of the Kibart and Virbalis Jews. I knew that these were in the Vigaines, a field about 1.5 km from the town. I remembered this place still from the time of my studies in the Hebrew High School in Virbalis when we went to play soccer and other games. I saw 12 holes /graves, but no fence and no sign could be seen, with cows and horses grazing on the graves. I cried bitterly seeing this terrible sight and recorded it in a photo. I was shocked because of the inhuman attitude of the local authorities who did not care about minimum conditions for remembering the victims. I made my way to the Virbalis local council which was situated in a former Jewish house in the main street, where the only clerk there, a girl, informed me that this issue of commemoration was under the authority of the town mayor, who resided in Kibart. I returned to Kibart, found the office of the mayor and put my case to a clerk, since the mayor himself was not present. He told me that they were aware of the situation, that a monument would be set up soon, and that the area of the graves would be fenced off. Returning to Vilna with a broken heart I sent a letter to the town mayor in Kibart on the same issue, and after some time I received an answer assuring me that a decision had been made to set up a monument that year (1966) and to erect a fence around this place. Three years passed, during which I did not visit the graves again. A week before our Aliyah to Israel (1969), together with my wife and my two daughters, I visited the graves at the “Vigaines” in Virbalis. I brought my young daughters there in order to show them what the Nazi murderers had done to our nation and to our family.

|

|

| The mass graves near Kibart |

[Page 219]

|

|

|

with the inscriptions in Yiddish and Lithuanian: “In this place were murdered by the Nazis and their local helpers the Jews of Kibart–children, women, men and a group of Lithuanians were shot.” |

|

|

| Monument on the mass graves near Virbalis |

[Page 220]

The monument established in 1991 on the mass graves near Virbaln where Kibart women and children were murdered.

The inscriptions in Lithuanian and Yiddish on the tables says: “Here was spilled the blood of about 10,000 Jews (Men, Women and Children), Lithuanians, War Prisoners of different nationalities, who were cruelly murdered by the Nazi murderers and their helpers in July and August 1941”

|

|

| (Among the victims there were the author's mother, sister Tekhiyah, aunt Sarah and girl cousin Tsiporah Leibovitz.) |

|

On that visit we found the place fenced off with a chain and there stood a concrete monument more than two meters high. The inscriptions on it, in Lithuanian and Russian, said that in this place Soviet citizens were murdered in 1941 by the Nazi fascists. There was no mention of the fact that at least some of those Soviet citizens were Jews and that their only crime was their Judaism. I found an empty barrel nearby onto which I climbed, and with my small pocket knife I engraved a Magen–David on all four sides of the top of the monument. I heard later from friends who visited the place where Maginei–David could still be seen and were not blurred. I suppose that no one visits this place anymore, and therefore there is no one who could rub out my engraving. (In the 1990s another monument with another inscription was erected as you can see in the photos from there.)

During those two visits to Kibart I was curious to see how the town, where I had spent a happy childhood, would look after the 23 and 27 years that I had not been there and what changes the events of the war had made. I did not expect to meet acquaintances, not Lithuanians and surely no Jews. I only

[Page 221]

wanted to see the streets and the buildings, each of them a reminder of something my past.

I arrived in Kibart by bus from Virbalis. The entrance to the town along the main street had not changed much. The “Torklerina” stood as before, with a few small changes and the sawmill, which once belonged to Shemesh, continues to work as before. Opposite there stood the former German school and I had no idea which institution was using the building now. Vishtinetz (Vistytis) street was partly ruined and the small houses looked as though they had sunk into the earth. From there on, in the direction of the border, the ruins started. The whole quarter, beginning from our house (Shadkhanovitz), Miltz, Budrevicius, the shop of Rosin and Katsizne and further along in the street of the synagogue the house of Pliskin, the synagogue itself, the house of Veitz, the bathhouse, all were destroyed, with cattle grazing where the buildings had formally been.

In 1969, on my last visit to Kibart, I noticed that on the plot where our house had stood, a large building, designed to be a restaurant, was under construction.

The red brick houses of the railway workers were intact, without any damage, as was the building of the fire brigade, and also the Pravoslav and Catholic churches, which stood there as before.

The grandiose railway station had been razed to the ground, there was nothing left, and in its place a small building had been erected, for selling tickets. The station sign read “Kibartai,” not “Virbalis” as for the last 100 years. The “Railway Garden” was ruined too and only some remnants of the bowling alley and a pile of stones where the raised balcony for the orchestra used to be, reminded one of past beauty.

The public park in the main street was not damaged. The houses of the local police and the government bank were ruined, but new similar buildings were being built. Seinensky's house and other buildings towards the border were not damaged, except for some small buildings in the yards which had been burnt. The long Torkler house near the border was undamaged, Lithuanian families lived in the former Jewish shops and in the former custom's building near the border. The wooden bridge over the Liepona stream had apparently been burnt down and a new concrete bridge had been built in its place. Eydtkuhnen was totally destroyed except for the railway station and a few buildings where the shops of Rubinshtein and Zilberman used to be. There was no civilian population in Eydtkuhnen and those few existing houses were defined as a military zone.

To tell the truth I felt some satisfaction that our house and those of the neighbors had been destroyed, but I also felt sorry that many Jewish houses still stood intact, their owners and their tenants having been buried in mass graves, with Lithuanians living in them instead.

[Page 222]

|

|

|

The building of the old government elementary school in Smetonos Aleja opposite the houses of Shadkhanovitz and Miltz. (Picture taken by Vytautas Mickevicius March 2003) |

Grocery shops: Khanes A., Khashman, Epshtein J., Feferman, Fainzilber Sh., Grinshtein, Halperin, Katz E., Katsizne, Kliatchko A., Levin M., Margolis, Maroz Sh., Rotshtein, Shtern A., Shtrasberg, Taburisky, Veitz A., Zilberman A.

Textile shops: Blogoslavensky, Blokh, Ginsburg, Levit, Miltz Sh.

Paper and Stationary shops: Leibovitz M., Rosin Y.L.

Haberdashery: Apriyasky A., Ginsburg, Shadkhanovitz M.

Shoes: Helershtein, Seinensky H.

Tools and Steel Products: Benyakonsky D., Vidomliansky E.

Bakeries: Frenkel, Landsberg, Sakharovitz, Yasovsky J.

Electric Appliances and Bicycles: Khashman Y.

Couriers: Aronovsky, Khashman A., Golding, Kanopke, Levinsky, Mandelblat A., Shtern A.

[Page 223]

Exporters: Kovensky, Rakhlin, Rezvin J., Rosenberg

Butchers: Blumberg Z., Fleisher J.

Barbershops: Bernshtein J., Khlamnovitz

Utensils: Miltz H.

Photo shop: Khlamnovitz

Cobblers: Borokhovitz R., Gordon, Levin B., Zakharik

Taverns and Restaurants: Kisetz A., Miltz J., Tomer, Voltchansky

Customs Clerks: Frenkel, Goldberg, Gershonovitz, Gutgold, Prensky, Rachkovsky, Sokolsky, Shereshevsky T.

Hotel: Papir

Watchmaker: Epshtein

Factory Owners: Alperovitz, Aizenshtat, Berniker, Bernshtein Sh., Itskovitz, Frenkel, Frishman J., Gamzu D., Gans, Gefen, Kanievsky, Kushnerzitzky, Rubin, Shemesh, Verzhbolovsky A.,Yasven B., Yurzditzky, Zilberman.

Doctors: Abramovitz, Mariampolsky (couple), Sher A., (medic)

Dentists: Kleinshtein, Pauzisky

Teachers: Halperin Sh, Leibovitz M., Lurie M., Matis Sh.

Lawyers: Bartenshtein, Lurie J.

Pharmacy: Gershater A., Tilzer

Clerks and Bookkeepers: Blumberg, Davidson, Rabinovitz M., Shlomovitz, Trumpiansky, Volovitzky Sh.

Coachmen: Mogiluker, Yofe, Yurkansky.

Shoemakers: Tsibulsky J., Vilensky

Tailor: Abramson

Others: Altshuler, Artchik (the “shamash” in the small Synagogue), Baron (taxi owner), Bromberg, Berezin, Borovik, Khosn, Dalon, Dembo, Davisky, Etelzon, Frenkel T., Feldshtein, Froman, Gruzinsky, Klotnitzky, Kuritzky, Leikin, Landau, Melamed, Moshe–Leib (the “shamash” of the Great Synagogue), Muzikant, Naihertzig, Pliskin, Pilovnik, Rog, Rakhmil, Rakovsky, Segal, Sheinzon (cantor and “shokhet”), Shatenshtein, Shimberg, Staravolsky, Slavotzky Batia, Tsikhak, Tsentnershver, Vrublevsky M., Yomtov, Zilbersky.

Almost all of these families were murdered by the Nazis and their Lithuanian helpers.

Let this List be a Memorial to the Kibart Jewish Community.

[Page 224]

Ozerov (Landsberg) Rachel, Ozerov Esther,

Apriyasky Aryeh (Peru), Apriyasky (Valdshtein) Rachel,

Borovik Mosheh,

Bartenshtein Joseph,

Borokhovitz Mordehai (USA), Borokhovitz (Yaron) Judith,

Berniker, Blumberg (Segal) Zina,

Khashman (Taub) Ayah,

Khashman (Gordon) Tovah,

Davidson Michael (USA),

Fainzilber Yitzhak,

Froman (Kagan) Yafah,

Frenkel Shemuel,

Goldberg Rita,

Ginsburg (Fin) Frida,

Kovensky Zisl, Kovensky Jakov, Kovensky (Priman) Shoshanah,

Kliatchko Perl, Kliatchko Miriam, Kliatchko Peretz, Kliatchko Eli (Germany),

Kaplan Yehudah,

Mogiluker (Gotlib) Shoshanah,

Manheim (Langevitz) Sarah,

Rosin Joseph,

Seinensky (Sheines) Berta,

Shadkhanovitz David,

Sheinzon Dov (USA),

Shtern (Kagan) Malkah, Shtern (Rochman) Frida, Shtern Dov,

Taburisky (Borokhovitz) (USA),

Tilzer Frida (USA),

Varshavsky (Bar–Shavit) Aryeh,

Vidomliansky (Shakham) Shalom,

Vizhansky Max, Yasovsky Hana,

Yasovsky Pesia,

Yasven (Veintraub) Roza,

Yofe Gershon, Yofe Yerakhmiel,

[Page 225]

After about fifty years it was difficult to recall all the names of Kibart Jews. No doubt that there are errors and oversights in these lists. The little information which it was possible for us to collect, we gathered with all our heart.

Unhappily many of these persons are not with us anymore.

|

|

|

From left: Shemuel Panush, Bela Mirbukh– Upnitsky ,Zisl Kovensky, Josef Rosin, Frida Shtern–Rokhman,–––––, Berta Senensky– Shilansky, David Shadkhanovitz |

[Page 226]

Bibliography:

The Archives of the Jewish Community Committee in Kibart– “YIVO” New–York Files 943–965.

The Archives of Yad Vashem– Jerusalem.

The Jewish Encyclopedia (Russian). St. Petersburg 1908–1913.

Akhsanyah shel Torah (Report of the Hebrew High School in Virbaln 5679–5681), (Hebrew) Berlin Virbaln 1921.

Kibart – Shie Tevik (Tuviyah Shereshevsky), the daily newspaper “Folksblat” (Yiddish) Kovno, November 1935.

The daily newspaper “Dos Vort” (Yiddish), Kovno,11.11.1934; 17.12.1934.

The daily newspaper “Di Yiddishe Shtime” (Yiddish), Kovno.20.1.1924.

The socioeconomic situation of the Jews in Soviet Lithuania, 1940–1941–Dr. Dov Levin.

From the Province – David Umru, “Folksblat” (Yiddish) Kovno, 25.7.1939.

The daily newspaper “Di Yiddishe Shtime” (Yiddish), Kovno.20.1.1924.

The socioeconomic situation of the Jews in Soviet Lithuania, 1940–1941–Dr. Dov Levin.

[Page 227]

Persian Famine Donation List from Kybartai 1872

Surname Given Name Comments BAMASH Yakov BERKOWITZ Dov BLUMGARD Shalom from Virbalis EITZELEWITZ Yitzchok Leib from Oshmyany (Ashmine) ETILZOHN Calev ETILZOHN Meir FLIGELTANG Yehoshua FOKSMAN Shmuel FRANK Yechiel FREINKEL Tzvi FRIEDBERG Avraham FRIEDBERG Dov bridegroom FRIEDBERG Menachem Aharon FRISHMAN Kopil FRISHMAN Mordechai GOLDBERG Ari Leib 2nd donation GOLDBERG Avraham Yitzchok GRODZENSKI Ari GRODZENSKI Gebrider GULUS Michel GULUS Tzvi LEWINSHTEIN Ari Leib MANESHEWITZ Mordechai Zelig MARKOWITZ Pesach MOREDECHOWITZ Note PORTAGEZ Aharon ben Yitzchok PORTAGEZ Yitzchok father of Aharon SEGELOWITZ Moshe SENIER Eli SHIDARSKI Tzvi SHLAMSKI Dovid WOLFE Yakov Leib WOLFE Yitzchok Eli WOLTZANSKI Mordechai YERKOWITZ Eliezer ZLATOWSKI Yitzchok

[Page 228]

A partial list of murderers from Vilkaviskis district

Periodical emphasizing the problems involved in the relations with the Lithuanian people and government

Published under the auspices of the association of the Lithuanian Jews in Israel 1, King David Blvd. Tel–Aviv, 64953, Israel

Photographs of headstones at Kibart Jewish cemetery taken by Samuel Rachlin and Nancy Lefkowitz, can be viewed on the World Wide Web (WWW):

https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/kibart/cemetery.html and https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/kibart/cem2.html respectively.

[Page 229]

Two particular letters among many others from people connected with Kibart

who found “ The Kibart Yizkor Book” on the Internet.

Subject: Kibart Page

From: SamRach@aol.comDear Mr.Rosin,

I have read the material on your Kibart site with great interest and noticed that my father's name appears in the pages as one of the Kibart natives. I would like to be on your mailing list and receive whatever relevant material you and other Kibartniks may be in the possession of.

My father, Israel Rachlin, the son of Shneur and Sara Rachlin, was born in Kibart in 1906. As your paper correctly states, he was born into a family of horse exporters, a business that he took over upon his graduation from the University of Leipzig in 1932. He managed the business until the Soviet occupation in 1940. The whole family, my father, my Danish–born mother, grandmother and my two older siblings, were arrested on June 14, 1941 and deported a few days later to Siberia together with the thousands of others thereby escaping the fate of most of the other Kibart Jews who perished in the Holocaust including my father's relatives. My parents passed away recently, my father in October 1998, and my mother just about three months later, in February 1999. They left behind 4 volumes of memoirs, the last appeared on the day my father died, all published in Danish by two leading Danish Publishers. The first volume, 16 Years in Siberia, has also been published in English by the University of Alabama Press. All four volumes have descriptions of life in Kibart, a place my father loved and told about all his life. After the fall of the Soviet Union, my father actually established contact with the city authorities in Kibart and corresponded with the mayor. He also received confirmation that the family house was still standing, and he also received a picture of the house.(I have the exact address in some of the papers my father left behind.) I plan to go to Lithuania this spring or summer to visit the place where my father was born. My grandfather, Shne'ur Rachlin and his brother Eliya, are buried in the Jewish cemetery, but I suspect that nothing is left of that cemetery. In any case, I am planning to go back and see what is left.

Last summer, I revisited my own birthplace in Yakutia [Siberia] and retraced part of the route of my parents' deportation. I went down the Lena river from Yakutsk to Bykov Mys at the Arctic Ocean, where my parents and siblings spent one year. I produced a 90 minutes long TV documentary about this trip and the family history, and it just aired in Denmark 10 days ago. I hope it will eventually be aired in Israel, too.

Just briefly about myself: I am a journalist, working as a foreign correspondent for Danish TV in Moscow and living in Washington DC with my family. This was all for now. I hope you will put me on your list and keep me posted about Kibart matters – as you understand I am an interested Kibartnik descendant. Sincerely yours, Samuel Rachlin

[Page 230]

PS. The English version of my parents' memoirs is “Sixteen Years in Siberia” Memoirs of Rachel and Israel Rachlin”, published by the University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa and London. 1988. Library of Congress Cataloging–in Publication Data 1. Rachlin, Rachel 1908– 2. Rachlin, Israel 1906 – 3.Jews–Soviet Union–Siberia–Biography DS135.R95A15813 1988 947'.004924022 86–25096 ISBN 0–8173–0357X.The name of my recent documentary on Danish TV was “The Journey Back to Siberia”. It aired in Denmark on January 18 and 19, 2000.

Kaunas, 17th of October 2002

Dear Mr.Rosin

Thank you very much for answering my letter.

My previous letter was short – to know you are OK, and to know what language can be used. I am very happy now – that is true…So, for the first – a bit about myself. I was born in March of 1945, in Kybartai (to be true – in a military hospital located in Eitkunai, because there was no hospital in Kybartai at that moment).

I can tell that I was born in Eydtkuhnen, East Prussia – for a joy… I was living in Kybartai till 1962 – when I graduated from Kybartai school (the building

of ex–Mittelschule). We lived in Torkleryne, Kestucio str., house of Adomaitis (next to Koltunovas, faced to Grubert's house).

My father Vaclovas was working at the railway station and my mother was keeping around the house at that time.

I graduated from Kaunas Polytechnic institute in 1968 as radio engineer, and was working in a semi–military research institute as designer of radio measurement equipment for 18 years, later – in a cardio–neurologic clinic with medical electronics and computers, now more than 10 years I am working as a computer application manager in a Kaunas heating and power plant.

I am married, have 5 children and 7 grandchildren.

My childhood and youth spent in Kybartai could be very happy – may be this is a reason of my love to this town. I see sunny green banks of summer's Sirvinta in my night dreams, my ears are wet when I leave Kybartai after a short visit.

I feel being in exile, a special kind of exile – it isn't forced exile, it isn't physical (I can return to Kybartai for a while at any moment – if I wish), but it is a spiritual exile – it is so hard to live in a city which is foreign to me, and to know I never will live in my lovely town of youth…

I am trying to find and save into computer databases all possible information about Kybartai. What I am searching for most and what I have – next time. I am not a historian or writer, I am only a simple engineer, so there is a rising question: what I'm going to do with all this information? I don't know…

I am still working man, I have many duties, many interesting occupations. I don't know how long God will keep me here, in this world…

[Page 231]

The easiest task – to place on a web pages as much info as possible – for a wide access for all people wishing to use it, and I am going to do this.I'd like to write what I think about you and your work “The Book of Remembrance of the Jewish Community of Kibart.” I can't remember when I connected to Internet and made my first search on word “Kybartai” (it was a long time ago – I'd found only 16 matching documents then), but I do remember that feeling of shock what I experienced, when I'd found your work…

I laid off away all my works to be done on that day (I had an access to Internet only at my work place then), and was reading, reading…

After a reading I was thinking a long long time…

About these young people whose faces I'd saw, about these what aren't (don't exist anymore), about these who are, but will never return…

About that part of Kybartai resident's what we had lost – forever. Lost them, their children and grandchildren. About that, what we lost with never having them living with us.

I had a great desire to write a letter of gratitude to you at the same second when I had finished the reading, but I am writing only now. May be, after the three years had gone…

I wasn't going to write about that material what you collected and published – it goes without saying.

I was going to write only about that, what I'd read “between lines” – it appeared to me that you love that tiny bit of land called “Kybartai”, and that it is dear to you no less than it is dear to me…

That we are very similar in this. It was very important to me…

The Lithuanian–Jewish relations after the Holocaust tragedy aren't such as they were before, alas…

Your book excels in tolerance and objectivity, it doesn't bitter old wounds, and after reading of it remains only favor and sympathy to people what could be alive and could live with us – if terrible human mistakes wouldn't be done…

I had printed your book and can show it at any time to anybody and anywhere without doubts and fear. I lay stress once more – your book is most tolerant of all I had seen.

Thank you very very much!

Sincerely,

Vytautas Mickevicius

[Page 232]

List of readable headstones at Kibart Jewish cemetery, 2001

Most of the photos were taken by Nancy Lefkowitz, several by Samuel Rakhlin (S.R.)[Page 233]

See: https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/kibart/cemetery.html https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/kibart/cem2.html

- Bromberg

- Blogaslovensky Hayah–Rachel bat Eliezer (S.R.)

- Filipovsky Rachel–Leah bat Avraham–Mordehai

- Freidberg Ya'akov ben Azriel–Zelig

- Frenkel Zelde bat Hayim–Yosef

- Goldberg Rivkah bat Yosef–Tsevi

- Grabovsky Avraham–Aharon ben Mosheh

- Hanas Hanah bat Tsevi

- Leibovitz Ya'akov ben Meir (The authors grandfather)

- Rakhlin Eliyahu ben Yehudah (new erected)

- Rakhlin Shne'ur–Zalman ben Eliyahu (new erected)

- Shtrasberger Hayah–Liba bat Azriel haLevi Luria (S.R.)

- Shwartz Hayah–Sarah bat Yehudah–Leib haLevi (S.R.)

- Shwartz Eliyahu ben Hayim–Aizik (S.R.)

- Volfovitz Pesakh ben Mordehai

- Yasven Hayah bat Eliezer

- YomTov Ya'akov ben Yosef

- Yoselevitz Mordehai ben Hayim

- Zlosotsky (?) Ya'akov ben Yitshak

|

|

|||

|

The tomb and tombstone of Ya'akov Leibovitz (the author's grandfather) at the Jewish cemetery in Kibart (Photo taken by the author in 1933) |

||||

|

|

|

Condition of same tombstone in 2001 (Photo by Nancy Lefkowitz) |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of the translation.The reader may wish to refer to the original material for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Preserving Our Litvak Heritage

Preserving Our Litvak Heritage

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 08 Dec 2018 by JH