Jewish Resistance in the Baltic States 1941-1945.

Lecture delivered by Professor Dov Levin of the Hebrew University

to YIVO,

New York City, October 23, 2001

See also The complete bibliography of the Works of Professor Dov Levin, 1945-2000

Project Coordinator

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

I remember it as if it had happened this very day. When I was seventeen years old, I was ordered to take my turn at forced labor, like the other adults. It was a cold, snowy day - thirty degrees below zero. I was taken to the airport of Kovno , together with thousands of Jews from the Kovno ghetto , and we were forced to dig drainage ditches under the supervision of German foremen. They were especially abusive to the elderly and the weak, and none of us even dared to protest. At that time, I remembered the hundreds and thousands of young, strong Jews, who were outstanding athletes for Maccabi [ Jewish Sports Organization] and other organizations in various sports, including fencing and boxing. A few of them were even champions of Lithuania.

In my bitterness, I thought then, "Where are now all those athletes and other Macho types who could help physically to rescue the beleaguered Jews from their attackers?"

It seems that a part of the answer to this odd question I received when I was subsequently accepted, with the utmost secrecy, into the fighting underground in the ghetto, -- and particularly -- when I was allowed to join the partisans in the forests near Vilna . However, it was only through years of research that I became aware of the full significance and magnitude of the resistance. I am honored now to present you with the main findings of this research.

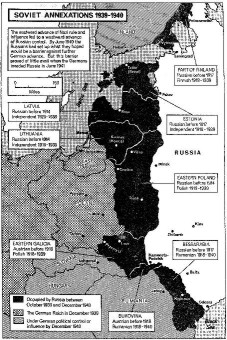

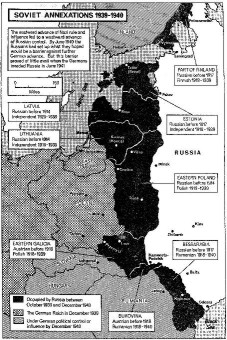

As you understand - my frame of reference will be the three Baltic countries .

In the largest of these countries, Lithuania -- there were 250,000 Jews at the beginning of the Nazi occupation in June 1941, (about 10 percent of the country's population. There were also 95,000 Jews in Latvia (4 percent of the population) and 4,500 - in Estonia (a half percent of the population), for a total of 350,000 in the Baltic states.

The long established "Litvak " Jewish community that spoke juicy Yiddish, had spiritual value's rooted in Hebrew-Yiddish culture, and, for the most part, lived midst a rich and long-standing tradition on the religious, secular, and national levels.

Even when political and economic factors in the inter war period caused a steady deterioration in the majority peoples' attitude toward the Jews, and even though the Jews' autonomous rights were severely reduced, the Jews still had a lengthy series of cultural and national achievements and assets. I refer, among other things, to a grand and comprehensive education system, from kindergarten to teachers' colleges, in Hebrew and Yiddish (with government support!) and, of course, famous cultural institutions. In Lithuania , the Jews had, for example, the yeshivas of Slobodka Kelm, Ponivezh and Telzh and also the YIVO Institute - in Vilna . In Estonia -- the University of Tartu had a Chair of Jewish studies. In Riga , Latvia , the Jews had a world-class Jewish theater and a special marine school for training sailors. Therefore, it is no wonder that even though less than two percent of world Jewry before the Holocaust lived in the Baltic countries, this community was many times more important in terms of its impact and uniqueness. It was for good reason that Jews called Lithuania the Eretz-Yisrael of the Diaspora and the Vilna community -- Yerushalayim d'Litta ( T he Jerusalem of Lithuania ).

When most difficult times suddenly came, these values undoubtedly helped to consolidate the spirit of resistance to the national repression that occurred under Soviet Rule at the -- beginning of World War II, in 1940 - 1941 .

In the main, however, it helped strengthen the Jews in the face of the Nazis' campaign of physical annihilation in 1941 - 1945 . Notably, much of the anti-Nazi resistance took shape on the basis of underground organizations that Zionist and Bundist groups created during the period of Soviet repression.

An important example was the debut of the underground Hebrew journal Nitsots (Spark) at Hanukkah 1940. This publication also continued to appear regularly during the Nazi occupation -- in the ghetto and even in the Dachau concentration camp , until the Americans liberated the camp.

There was three important aspects on the spiritual, value, and cultural levels. However, in this lecture I will concentrate mainly on the level of active armed resistance and hope to explain to what extent this phenomenon was unique in the Baltic countries as opposed to other locations in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe .

The Holocaust in the Baltic countries began immediately after German forces stunned these countries with a surprise invasion on June 22, 1941 , as part of "Operation Barbarossa" . This is especially true in the case of Lithuania , which shared a border with Germany. In the border towns, SS men and Lithuanians attacked Jews on the very first day of the invasion. What is more, in at least forty localities around the country, armed Lithuanians (who called themselves " partisans" ) began to murder, rape, and loot their Jewish neighbors even before the Germans arrived. In any case, Lithuania was the first Baltic country -- indeed, the first country in Europe -- in which the Jewish community was targeted, as far back as June 1941, for the first steps toward implementing the " Final Solution to the Jewish Problem", spearheaded by the infamous Einsatzgruppen . For geographic and strategic reasons, it took Germany only four to five days to occupy Lithuania . In more distant Latvia , the conquest took seven to eight days, and in Estonia , the northernmost of the Baltic countries, it took almost two months.

These differing periods of time had several clear implications for the Jews' ability to play a meaningful role in resistance.

Sixty percent of Estonian Jews, 15 percent of Latvian Jews, and 8 percent of Lithuanian Jews -- some 30,000 men and women in all -- managed to escape into the Soviet interior in this manner (amidst heavy bombardments and attacks by the Germans and their local accomplices).

Notably, the act of escape was not only an example of activism par excellence! Eventually, it also allowed many of Jews to enlist for systematic warfare in regular armies!

8,000

of them intended to enlist for active combat with the Baltic national

divisions and other units in the Red Army. In the

16

th

Lithuanian Rifle Division

alone, nearly

5,000

Jewish soldiers and officers saw action during the war. Since most of them

joined infantry units, they had frequent opportunities to directly confront

German soldiers, whom they considered personal and national enemies. In these

engagements,

2,000

Jews were killed and many were wounded. Jewish fighters were awarded medals

and decorations for their outstanding service at the front and in the enemy's

rear.

Much the same happened in the

Latvian divisions

, in which

3,000

Jews fought, and the

Estonian divisions

, in which

300

Jews saw action. Additional Baltic Jews fought in other Red Army units and in

the Polish army.

If one includes these, the number of Jewish soldiers who found ways to opposed

the Nazis and their allies in active warfare climbs to

10,000

.

Thousands of relatives of soldiers and other Jews found themselves in the

Soviet Union

, either as deportees to

Siberia

as "enemies of the people" or as refugees ("evacuees") on

the kolkhozes and in villages and towns of

central Asia

. Some of them suffered severely and a few even died of starvation, cold, type

and subhuman living conditions. However, most of them survived and joined the

war effort.

Immeasurably worse-horrible, - was the fate of more than a quarter million Jews who remained in the Baltic countries , under Nazi occupation. Most did not survive until the end of the war. Some 94 percent of them perished in various and sundry ways, the highest proportion throughout Europe.

Unlike other Nazi-occupied countries, where most Jewish citizens were put to death in gas chambers, a large majority of Jews in the Baltic countries were slaughtered brutally with firearms and other weapons by their Lithuanian, Latvian , and Estonian neighbors (sometimes under German supervision).

In a brief period of time - from June to December 1941 - those remaining -- about 45,000 -- were temporarily interned in the ghettos of Vilna, Kovno, Shavli , and Sventsyan -- in Lithuania and in Riga, Dvinsk , and Libau -- in Latvia. Estonia , where there were few survivors, was declared Judenrein free of Jews.

Even after the mass murders -- mass deportations and executions of groups and individuals continued intermittently in the ghettos. In these actions, sophisticated deceptions were used to take the victims by surprise. Also, the distressed Jews were informed that if they dared to resist, their families and neighbors would be first in line for execution.

Even so, in dozens of known cases, if not more, Jews responded by protesting and resisting in various ways. Consciously or unconsciously, these reactions were attempts to oppose the murder, the starvation, and the oppression. Many of these acts were impressive some were even effective. They ranged from a Jew dying in the bloodbath in the Kovno suburb of Slobodka who dipped his finger in his flowing blood and wrote " Yidn , nekommeh " ("Jews vengeance!") in blood on the wall, to the Jews who, on the very lip of the death pits, tore their money to shreds instead of surrendering it to the Germans.

Children in the Kovno ghetto , whose friends had been murdered by Lithuanians, wrote in Lithuanian a bitter parody of the national anthem "Lithuania, Our Homeland":

Lithuania, Our Blood-Land

May you be accursed for centuries

Let your blood flow

Like the blood of Jewish children". (and so on)

Of course people gathered to sing this song, although only indoors and in subdued voices.

What is more, even during the first wave of riots and mass murders, Jews in several remarkable cases resisted their attackers physically. It seems that the use of force was usually limited to clearly hopeless situations -- --that is, when the Jewish principle of mutual responsibility no longer applied.

In Latvia, too, there were also many acts of individual resistance:

There were also spontaneous mass uprisings, some of which are recorded only in German sources.

These facts are confirmed in German documents and were also mentioned in a popular song that circulated in the Vilna ghetto at the time.

These are only a few of hundreds of similar acts. They indicate that most such cases were the spontaneous responses of individuals or, at the most, of very small groups, to a specific horror or outrage.

In late December 1941, when the situation stabilized -- it also became possible to plan the nature of the response and to devise methods of organization to put plan into practice. In the main, there was a change from sporadic actions to systematic actions and reprisals -- to organized struggle that varied in accordance with the local situation and the way the future was viewed.

The direction of this trend in resistance was reflected clearly in a famous public event in the Vilna ghetto late 1941 -- the public reading of Abba Kovner's manifesto:

Hitler plans to kill all the Jews in Europe." The Jews of Lithuania are the first in line" [So] let us not go like sheep to the slaughter . We may be weak and defenseless, but the only possible answer to the enemy is resistance !

Today we know that this was the first time that Jews viewed the mass killings by the Einsatzgruppen and local murderers as part of a master plan for the destruction of all of European Jewry. It was also the first time that Jews were urged to mount an organized fighting resistance. In any case, 45,000 Baltic Jews survived the mass slaughters in 1941 , and about 1,500 of them, men and women (most of them in their teens), joined anti-Nazi underground organizations in the ghettos and labor camps. The main purpose of these organizations was armed struggle, that is, an uprising in the ghetto or a armed break-out from the walled ghetto for the purpose of engaging in partisan operations on the outside. In some instances, especially in the Vilna ghetto , these two goals were combined, the uprising being followed by an organized escape from the ghetto. Although there was no uprising in the Kovno ghetto , Jews who fled from there to the forests engage in combat with German forces and local collaborators. Some Jews who fled to the partisans from the Riga ghetto -- did much the same. Due to misfortunes, such as ambushes arrests, and betrayals by local inhabitants that occurred on the way to the forests, a large percentage of the escapees perished before reaching the forests.

Nevertheless, some 1,800 Jews escaped from ghettos and labor camps in the Baltic countries , either at the initiative on with the help of underground organizations, or as individuals or in groups of families. Most of them were taken in by units of the Soviet Lithuanian partisan movement, Soviet Latvian and Belorussian units, and in so called " Jewish family camps ."

Although these numbers are impressive in themselves, they also underscore a significant tragedy in regard to the very possibility of armed resistance by Baltic Jews. After all, while more than a quarter million of Baltic Jews were being massacred in 1941, an anti-Nazi partisan movement worthy of the name did not yet exist !

By the time this movement began to develop in both quantitatively and qualitatively, no more than 45,000 Jews remained, and they were interned temporary in ghettos and labor camps.

Nevertheless, some surviving Jews apparently made impressive and effective use of even this belated opportunity. Study of the records of partisan activity in Lithuania shows that the majority of Jewish fighters in the ranks of the Lithuanian partisan belonged to units that had distinguished combat records.

No less important at that time, amidst of the ongoing fighting, Jewish partisans were sometimes able to settle scores with murderers of Jews, both German and local. In several cases, Jewish partisans initiated special revenge operations against identified murderers. It should also be noted, in regard to Jews who were still alive, Jewish fighters in the Vilna Partizan units disobeyed orders to stop bringing Jewish survivors from the ghettos and villages to the forest.

Many young Jews who had an opportunity to join the partisans, turned it down on moral grounds. Some, for instance, were reluctant to abandon elderly parents to their fate. This situation was described by twenty-year-old Abba Weinstein , (now Ambassador Dr. Abba Gefen ) who for three years headed a group of fighting Jewish survivors in the forests of southern Lithuania, with a rusted handgun as his only weapon. On May 31, 1944, Weinstein recorded in his diary:

"I went to see Alphonse Rushkovsky , who was active with the anti-German partisans. He said that we should start joining the partisans and should not wait. I said that this was easy for my brother Josef for Shmulik and me". We could join the partisans. But what about the others, who are not able to do so?

He answered, "Let them stay here and look out for themselves!"

He is incapable of understanding us. We are important for them as partisans, but we see things through Jewish eyes. Every Jew is important to me"

For various reasons not all members of underground organizations felt they could avail themselves at the chance to join the partisans as they wished. However after being captured, some of them carried on clandestine resistance activities even in the Dachau concentration camp in Germany. There, as I noted before, they continued to publish until liberation (!) the only permanent Hebrew-language journal under Nazi rule.

This amazing fact is only one of a considerable number of uniqueness acts that Baltic Jews performed in their resistance and active warfare - in addition to Abba Kovner's " Sheep to the Slaughter " manifesto, the first of its kind in all of Europe. Here are other examples:

This is the place to note that the Jewish soldiers in the 16th Lithuanian Infantry Division of the Red Army comprised the largest ethnic group in the division. They were so prevalent that in some formations the commanders gave orders in Yiddish and an impressive Jewish atmosphere was maintained during different opportunities. It is no wonder that even in the midst of combat one could hear such Yiddish battle- -cries: " Brider, far unzere tates un mames " (Brethren, for our fathers and our mothers!).

Some may ask, to what extent the resistance and combat activity, (of whatever kind), affected the rescue of any portion of this Jewish community, whose fate seemed to be sealed back in the autumn of 1941". There is no unequivocal answer.

Against those who claim that at least 1,600 persons survived the Holocaust by joining the fighting organizations, one can counter, that thousands of Jews in fact perished as a direct result of their membership in these organizations. In the Jewish community of Olkienik , for example, only 4 percent of the dozens of Jews, who joined the partisans' ranks survived. On the other hand, a relatively large proportion of Jews (some 12 percent) survived in the Shavli ghetto , where the resistance movement was the least developed.

Nevertheless, statistics alone do not entirely answer the question we have posed. Let us bear in mind that self-defense, resistance, and struggle were natural human reactions to the Nazis' attempt to annihilate the Jews, just as they are when Israel is under attack and in the case of America today.

However, several incidents, including the example of the Vilna ghetto , where the " battle of the barricades " in September 1943 had meager results, suggest that the urge to fight and resist then was more emotional than logical. However it can still be maintained that the preferred course of action was the honorable one, even when it did not lead to the rescue of large numbers of Jews.

I would like to conclude my lecture with a statement made by Dr. Elhanan Elkes , chairman of the " Council of Elders " in the Kovno ghetto :

This is the honorable road that we should choose. I will bear all the responsibility -- it is for the good of the remnant of Lithuanian Jewry and the Jewish people as a whole. Every opportunity to resist should be exploited, especially when it is a question of honorable combat!.

This shows why the historical importance of Dr. Elkes' words, spoken in defense of extending help to the underground in Kovno ghetto , will always outlive all other considerations. Finally I wish to say that I identify personally with what he said there, in the ghetto.

I received support for this at the time from a unique message from a schoolmate who had been interned at the Stutthof concentration camp with my mother of blessed memory, shortly before her bitter end on November 25, 1944 . By then, my mother learned that I had joined (Barukh Ha-Shem) the partisans in the forests. This knowledge gave her much happiness -- and eased her suffering in her final days...

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 19 Dec 2011 by LA