|

|

|

[Page 214]

by Micia Jedwab–Katsir

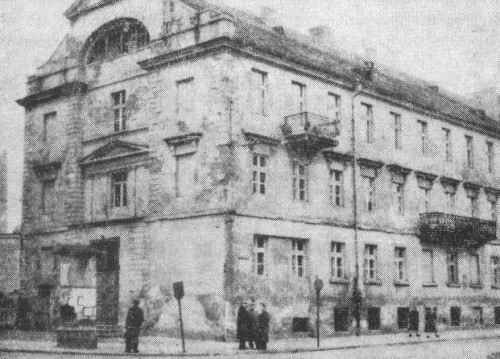

For many years the main and side entrances to the gymnasium were in the gloomy tunnel–like gateway. Wooden steps led to the two upper floors. Most of the class rooms faced onto Kilinski Street. The scenes in the courtyard were more interesting. The courtyard was large, paved and surrounded by tall buildings. We spent the breaks in the open air. On market days part of the courtyard was full of peasant carts. The unharnessed horses cheerfully chewed their hay and oats. The scent of the hay told us about the clear air of the fields in the distant villages.

The first floor was arranged like a proper school: Class rooms, a hall for the breaks between lessons, the teachers' room, and the principal's room which we used to pass almost on tiptoe. At one end of the corridor on the second floor were classrooms, while there were private apartments at the other. The poor tenants always grumbled and rebuked us about our bad behaviour. They could not understand how studying youth could yell and sing during the breaks. But in its final years, the gymnasium bought up all those dwellings.

The Jewish gymnasium at Kalish was the property of the Jewish Society for Secondary Schools which were headed by Dr. Braude. The language of instruction was Polish. We usually began the school year with prayers at the synagogue in Krotka Street. Two–by–two we used to march there through Babina Street at the beginning and end of the school year and also on

|

|

[Page 215]

Polish national holidays. On those occasions we marched through the main streets and aroused the admiration of the Poles.

The School Committee was largely Zionist and tat set a stamp on the education. The matriculation examinations were usually conducted in a very solemn atmosphere but that was not the case with the Hebrew examination which was characterized by a cheerful national spirit.

The head was Mr. Helling whose principles determined the school spirit. Most of the teachers came from Galicia, which was the cultural centre of Poland in those days. Each one is worthy of mention, but I shall restrict myself to Mr. Zimmer, the youngest of the teachers and the one closest to us in spirit. He left his post at the gymnasium and proceeded to Eretz Israel and that strengthened the spiritual ties between us.

My own teacher was Mr. Bakalar, an excellent pedagogue and the one–time secretary of Bialik who imbued us with a love of Zionism and Hebrew literature. Thanks to him we came to love Bialik and Tschernichovsky. On his initiative, we wrote a letter to Bialik and received a reply which was framed and graced our hall. Bakalar led us into the world of ideals when he told us about his Zionist activities in Pinsk where he was born.

They used to set out in boats on the river Pripet and there they organized their Zionist activities which were prohibited by the authorities. He was proud of each one of us that went up to Eretz Israel as a Halutz or a student. It may be largely thanks to him that all the surviving members of his class have gathered together in Israel although the war scattered us in many countries.

I cannot mention all those who fell but must speak of Judith Lefkovitz or ‘Drina’ as we called her. Her father was the gymnasium dentist and an active member of the committee; a Zionist from Lithuania who gave his daughter a Zionist education as well. Drina was a thorough–going idealist. She completed her studies at the Warsaw Institute for Jewish Studies and also completed her studies at the university. She then returned to Kalish in order to teach at the gymnasium from which she kept in touch with those of us who had already gone to Eretz Israel. She fell as a heroine when she slapped the face of a Nazi while defending her Jewish self–respect and became a symbol of the young Jews educated in the national spirit at our gymnasium.

by W.K.

The first group of Jewish actors who came to town in 1908 was “Landsman's Troupe”. Those were the years of the reaction which followed the 1905 Revolution and the presentation of Yiddish dramas on stage was forbidden. Permission to appear was achieved thanks to bribery. The advertisements announced that this was a German–Jewish theatrical troupe. But sometimes the Governor himself came to the theatre and found that what was being spoken on stage was not German at all. When that happened, no excuses helped and the audience had to disperse.

[Page 216]

|

|

Under the German occupation, Yiddish performances were allowed and Jewish actors used to appear in town. After the liberation of Poland, the well–known and popular Leizer Levin, who was generally known as ‘Geler’ or ‘Ginger Levin’, engaged in the theatre as his hobby. He continued to be active in this field until the outbreak of World War II and used to bring us excellent theatrical groups such as ‘Vikt’ and ‘Young Theatre’ as well as well–known actors.

The first group of amateurs was founded in 1912 by the actor Rakow who also served as its producer. In 1915 a Dramatic Circle was established by Ephraim Zimmer, Moshe Jedwab, Zalman Gottfreund and Jacob Reich who presented Gordin's ‘Brothers Luria’. In 1917, Mondze Klechewsky and Ginger Levin revived the circle as part of the Turn Verein activities. They presented King Lear, the Brothers Luria, Shulamit, etc. and had a least thirteen amateur members who were later joined by three younger people.

Following the expansion of Jewish communal life in the Polish Republic, dramatic circles were founded by all the parties and in the schools for further study associated with the Arbeiter Heim. Peretz Hirshbein, the dramatist, visited Kalish in 1920 when three Dramatic Circles presented his plays.

The Poalei Zion Amateur Group was managed by W. Jacobovitz and D. Neugarten and had a least ten acting members. The plays presented included: Bimko's Thieves, The Broken Hearts, Hertzele the Aristocrat, Shlomke the Charlatan and The Slaughter by Gordin. The Bund Circle was managed by Stark and Matuszak.

In 1925 the ‘Sambation’ and ‘Azazel’ Little Theatres were very successful in Poland and the establishment of a Little Theatre of the kind in Kalish was proposed. The organizers were Tenzer, Leszczinsky and Sieradzki. By agreement with Jacobovitz and Neugarten of the Poalei Zion Amateur Group, it was decided to ask the poet Moshe Broderson to undertake the artistic

[Page 217]

direction of the new Theatre, Broderson came to Kalish, met the amateur actors and accepted the post offered. Jacobovitz, Neugarten and Kaplan were to be the stage–managers.

This was the start of the ‘Comet Amateur Little Theatre’. The first programme was given the familiar Kalish phrase: “Wos well ich hoben darfun?” (What's in it for me?) as a title. The text was by S. Rubin and the music by the conductor Krotianski while part of the material was written by Moshe Broderson.

The performances were very successful and were repeated eight times in all. Broderson was enthusiastic about the execution. The second programme was entitled: ‘Lomir sich iberbeten’ (Let's make it up) and the third: ‘Hallo Charleston’. Texts were provided by Broderson, Rubin and Kaplan. The “Comet” also went on tour and was very successful in Poznan, Turek, Kolo, Sieradz, Zdunska–Wola and Wielun.

Actors of the “Comet” troupe were: W. Jacobitz, Z. Neugarten, W. Shlomowitz, H. Englander, H. Jachimowitz, H. Rosenzweig, L. Rabinowitz, Nissenbaum, W. Lubelski, A. Leder, Helfott, Beckermeister, Tondowska, Scher, Berkowitz, etc. But in spite of the material and moral success, the receipts were not enough to cover the outlay on orchestra, conductor, costumes, scenery, etc. The troupe broke up in 1928. Some of the members left town; several of the women started raising families, etc. But Kalish folk will continue to remember their “Comet”.

by S.R.

S.R. describes the changes within the centuries–old community of Kalish which led the younger generation to find their way to various youth movements including Hehalutz immediately before World War I and during the two decades that followed. Aliya to Eretz Israel began to be thought of in 1924 when many young people registered to proceed to the homeland on foot. However, a major crisis came about in 1926 and 1927, and many of those who had gone to Eretz Israel came back bitterly distressed and disappointed. Yet, those were the years which marked the beginnings of Hehalutz, whose members started off by studying Hebrew and singing Hebrew songs. Apart from Hashomer Hatzair, this was the only Youth Movement in the city which called for actual Aliya under all conditions.

The new group had no club of their own but met every evening in the Municipal Park. At one time they also used to gather at the Poalei Zion Club and later in the Hashomer Hatzair quarters; but the meetings in the park, held in all weathers, remain unforgettable.

When the late Daniel Levy joined, the Kalish Hehalutz was transformed from a sentimental group of youngsters into a serious body aiming at and preparing for Aliya, going through the full channels of Hachshara. Hehalutz never became a mass movement in Kalish but it exerted considerable social and public influence. It provided the channel through which many young people from Kalish and elsewhere proceeded to Eretz Israel and became part and parcel of the new life there.

[Page 218]

|

|

| Key to Numbers:

1. Bus Station Changes in street names:

First of May Square – The New Market. Nowotki Street – Nadwodna Street. |

[Page 219]

by Baruch Tall

Before me lies the map of the City of Kalish. At first sight, it is a simple plan: dust a few lines criss–crossing one another, other lines that are more or less parallel with circles and segments of circles here and there. Only the townsfolk will know how to decipher this map and breathe the spirit of life into it.

In the centre of the city stands the New Town Hall which was erected on the ruins of the building that the Germans destroyed in 1914. From the early hours of the morning the building is thronged with citizens and residents who come to find a birth certificate, pay taxes or hunt up an address.

In the corridors can be seen Jews in their traditional dress holding round little ‘Jewish hats’ in their hands waiting for some spokesman or counsellor who can help them reduce the burden of taxes.

The clock in the Municipal Tower strikes the hours according to which those shops in the Town Hall Square, which is called the Old Market, are open or closed. On festival days and national holidays crowds gather here, a military band plays and speeches are delivered from the balcony of the Town Hall.

Three lively streets have their beginnings at the Town Hall Square. The first is Wroclawska or Breslau Street. After its first half it is known as Gornoslonska Street. Here the handsomest shops in the city can be found – banks and an iron bridge over the Prosna. Halfway along is the starting point of the Josephine Boulevard and at the cross roads on the corner is the Exchange. There you see merchants and middle–men buying and selling goods, foreign currency and land. The great majority are Jews. The corner is like a beehive, people seem to be milling around aimlessly but in actual fact, many make a living here.

On the Sabbath, the whole appearance of the street changes. Most of the shops are closed and locked while the Exchange also seems to have vanished.

This street leads to the Railway Station. There are few buses and poor roads. The railway line is the main link between Kalish and other cities.

A single bus–line leads from the Old Market to the Railway Station, but few people make use of this means of transport. Most of the residents go to the station in a carriage or a ‘risorka’ (a horse vehicle taking passengers at a fixed rate along a fixed route). Most of the carters are Jews and the central station for the risorkas is in the ‘Ross–Mark’ or Horse Market.

The second street, starting from the square is Zlota or Gold Street which continues as Nowa or New Street as far as the Maikow Fields. This is the spinal cord of the Jewish Quarter.

In this street lies the Great Synagogue with the House of Study behind

[Page 220]

it. All the shops belong to Jews. During the six week–days, the streets are thronged with merchants, customers and simple idlers standing at the street corners discussing ways and means of making a living and politics and whispering the latest news to one another…Here there really is a small–scale ‘Jewish Commonwealth’ living, breathing and working according to the rules it has set itself.

On Sabbaths, festivals and other regular seasons, the street is quiet. Early in the morning the householders can be seen wearing their prayer–shawls under their coats as they proceed with measured paces to the synagogue or to one of the many shtieblech to be found in the district.

In the afternoon, lads and lasses wearing Sabbath or festival garb come out to stroll or meet, attend a lecture or a discussion at the Hashomer Hatzair Club in Ciasna Street or the Left Poalei Zion Hall across the road. The residents know one another, rejoice in one another's joys and share in their sorrows. A wedding in the street makes the neighbours happy while a funeral, far be it from us, grieves them one and all.

To be sure, Jews live in all parts of the city but this street, together with Babina, Ciasna and Chopin streets which cross it and are inhabited by Jews (the only Poles being the janitors) are the heart of Jewish Kalish.

The third street is Kanonicka Street where most of the inhabitants are also Jews. Halfway along it is an aged building that looks as if it is about to tumble down. It contains the offices of the Kehilla or organized Jewish Community. Next to it is the Mikveh or Ritual Bath Building.

The Church of Holy Mikolai somewhat disturbs the harmony here. It is not the habit of the Jews to walk along the pavement next to the church.

Kanonicka Street leads to the New Market at the centre of which is the Fire Brigade Building. The bells ring. There is a fire in town. From every side, large and small, old and young come dashing. “Es brennt!” (fire! Fire!). Voluntary Fire brigade members arrive, harness horses to the engines – there is ample commotion. It has happened more than once that by the time the Brigade arrives the fire has burnt itself out and nothing but charred and smoking walls are left.

The New Market is the place at which hundreds of Jewish peddlers make their living. They bring their goods by hand–cart early on Tuesday and Friday mornings and arrange their stands in level lines along the centre of the Market Place.

Peasants from the surrounding villages fetch their produce: butter, cheese, eggs and chickens. Jewish housewives go about between the stands poking at chickens, bargaining and buying what they need for the Sabbath. The peasants put the money in their hip–pockets and disperse among the stalls. From the Jewish peddlers and hawkers they buy clothes, shoes, caps and kitchen utensils. The ‘mutual trading’ goes on until noon. On Fridays in the winter, the Jewish peddlers do their best to clear their stalls early and hurry home for fear of profaning the Sabbath.

Between the Babina and Nadwodna Streets there once flowed slowly a

[Page 221]

a branch of the Prosna which crossed the Nowa and Zlota Streets passed along Kanonicka Street and reached the Municipal Park. After the Nazi exiled the Jews of Kalish, they blocked this branch and paved its banks with gravestones from the Jewish cemetery.

The ‘Jewish’ section of the river has vanished from the map. Together with it, as though symbolically, the termination of the Community of thirty thousand Jews has come to termination. Jews that have lived in this part of Kalish for so many generations.

People who have visited the city during recent years relate that it stands as before. Poles have taken possession of the Jewish homes. Only buildings where the plaster is falling from the walls still stand as memorials for a vibrant Jewish community that has been exterminated.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kalisz, Poland

Kalisz, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 15 June 2016 by JH