|

|

[Page 15]

By Dr. N.M. Gelber

The Beginnings

Kalish, on the River Prosna, has been a city with considerable municipal rights of autonomy ever since the 13th century, by which time the population already consisted of Poles, Jews and Germans from Silesia. It belonged to the Hanseatic League and was made a Free City in the year 1360. Under King Kasimir the Great, in the mid-14th century, it became the second capital of Poland. At the period of the Reformation, it became a Protestant refuge. Early in the 17th century, the first astronomical observatory in Europe was constructed there. Throughout the Middle Ages and after the city, which was strongly fortified and had four gates, suffered the usual vicissitudes of siege, revolt, warfare, pillage, fires, etc.

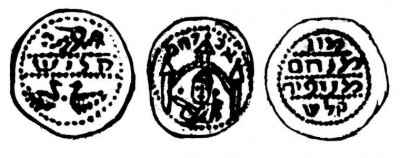

Jews were to be found in Silesia by the middle of the 12th century and had entered Great Poland by the first decades of the 13th century. Several places called Zydowo (Jew-town) are referred to at that time, one being close to Kalish. According to Thadinski, the historian of the city, Jews were already resident in Kalish as early as 1139. By the end of the 12th century, there were Jewish minting specialists in the city as proved by one-sided coins known as “Brakmats” bearing the imprint: “Joseph Kalish” in Hebrew characters. It appears that at this period, Jews were masters of various mints in Germany and in Austria and also supplied the metal for the coins. Jewish minters seem to have been among the first to reach Western Poland and they operated a mint in Kalish for seven years.

The Kalish Privileges

On 10th September, 1264, the Jews of Kalish were granted the “Kalish Privileges”, consisting of 37 articles. Thirteen of these deals with matters of Jewish credit and two with Jewish trade. Under these privileges, the Jews had the status of “servi camerae” (servants of the Treasury or of the local Government authority). For this, they had to pay the local duke certain amounts in return for which he gave them his protection. They were subject to his jurisdiction or that of a special judge appointed by him and known as “Judge of the Jews”. However, they were not under the jurisdiction of the city in which they dwelt. Criminal cases were judged by the duke in person.

Internal Jewish disputes were dealt with in Jewish courts but the Judge of the Jews might intervene at the request of either of the contending parties. The Jewish court was held in the synagogue. Jews might not be brought for trial during their Festivals but otherwise, they had to appear in Court as soon as summoned. Any person who did not appear when summoned for the first or second time had to pay a fine.

[Page 16]

No Jew might be required to take oath on their Torah Scrolls save in major trials for sums exceeding the value of 50 marks of fine silver, or when he was summoned before the duke. In minor trials, he had to take oath in front of the synagogue and at its doors.

If a Christian brought action against a Jew, whether on a criminal or civil charge, he had to bring a Jewish witness as well as a Christian.

Any person injuring a Jew, who was the property of the duke, had to pay a fine to the duke's treasury and damages to the Jew. Any person murdering a Jew was sentenced to death and his property was to be confiscated by the ducal treasury. Similar punishments were provided for wounding a Jewess, destroying a Jewish cemetery or taking a pledge from a Jew by force. Any person throwing stones at a synagogue had to pay the authorities a fine of 2 “stones” of pepper. A person kidnapping a Jewish child by force was judged as a thief.

In accordance with the Bull of Pope Innocent IV, which was published after a blood libel charge at Fulda in Germany in 1253, it was severely prohibited to bring any such charge against any Jews whatsoever within the Duchy, namely that of using human blood, “since all Jews refrain by reason of their faith from consuming blood in any fashion whatsoever”.

If a Jew should be charged with the murder of a Christian child, the matter had to be proved by three Christians and an equal number of Jews. If it should be proved, the Jew would be punished but not by the customary punishment for this crime. If he should prove himself innocent by the said witnesses, then the Christian would not unjustly be sentenced to the punishment which the Jew would otherwise have had to bear because of his malice.

A Christian suspected of murdering a Jew might prove his innocence through trial by combat and the court would appoint the person with whom he would have to do battle.

If the Jews transfer the bodies of the dead after their fashion from one city to another or from one district to another or from one country to another, the tax collectors are not authorized to levy any payment upon them; and if they do so, they will be punished as robbers.

If a Jew is compelled to raise an outcry at night on account of any great urgency and the Christian neighbours do not give him the necessary aid and do not gather at the sound of the outcry, then each Christian neighbour shall pay thirty soldi to the judge or to the local authority.

Thirteen articles deal in detail with interest charged by Jews. If a Christian claimed that he pawned an article with a Jew for an amount less than the latter demanded, the latter had to take oath that he was telling the truth. Christian religious apparel and wet or blood-stained garments might not be accepted as pledges. Jews might accept horses as pledges only openly and by daylight. If a Christian found a stolen horse held by a Jew, the Jew would be deemed innocent if he took oath that the horse had been pledged with him openly and in the daytime; that he had lent money to its owner and had no reason to believe that the horse was stolen.

If a Jew advanced money against land or deeds of outstanding individuals and could prove this by the documents and the seals, the Jew would be

[Page 17]

allocated the land as with any other pledges and he would be protected by the authorities against all duress and compulsion.

Jews transporting wares were not to pay any higher customs duty or octroy than the citizens of the city in which the Jew might be staying at that time. Jews might buy and sell anything, might touch break like Christians and any person restraining them from so doing would be fined. A further clause reads: “Likewise, we desire that no man shall be billeted in the house of a Jew”. This exemption from the duty of billeting was otherwise granted only to the clergy and the nobility and would seem to indicate the special status of the Jews in the eyes of the law.

The Kalish Privileges were afterwards extended to all the Jews in the Duchy of Great Poland. Subsequently, they were confirmed and expanded in the years 1334 and 1364-65 by Kasimir the Great and extended to the whole of Poland. At that time, the document was entrusted to a Kalish Jew named Falk.

Similar privileges it should be noted had already been granted to Jews from the mid-13th century in Austria, Hungary and Bohemia. However, the Polish privileges included certain clauses that were not to be found in the others.

The original text was printed in a collection of laws prepared by Jan Laski, approved by the Polish Seim (Parliament) in Radom and published in 1506. Certain changes for the worse were made and the inclusion of the law was justified by the declaration of the then reigning King Alexander: “We, King Alexander, command that the Privileges be included in the Code of Laws not in order to confirm them afresh but as a precautionary measure to protect the Jews”.

Polish scholars sometimes describe these Privileges as the Magna Charta of Polish Jewry. While considerable attention is paid to Jews as money-lenders (i.e. the bankers of the Middle Ages), they also seem to have played a very significant part as merchants who maintained the flow of goods throughout the country and from one territory to another. The recognition of the Jewish, i.e. Rabbinical Court as the legal authority in internal Jewish affairs and disputes helped to secure the growth of the subsequent internal autonomy of Polish Jewry which has been a decisive factor in shaping the lives of East European Jewry and their descendants.

Early Days

As frequently happens in Jewish history, the presence of Jews is known through some calamity. In this case, it is known that in Kalish they suffered from hunger in 1282 on account of pestilence. The first step taken by the community as such was to establish a cemetery which goes back to the year 1287 and was paid for at the rate of six talents of pepper and two talents of saffron as an annual leasehold rental.

The early Jewish community was set up not in the commercial centre but nearby, apparently on the left bank of the River Prosna. To begin with, Jews were engaged in crafts such as tailoring, butchering, gold and silver working; and there were also those who engaged in agriculture. Following the prohibition of lending money on interest by the Church, an increasing

[Page 18]

number of Jews began to engage in finance so that by the time of Kasimir the Great, Kalish and Posen lying further north were important Jewish banking and credit centres.

However, the Black Death, which spelt calamity throughout Central Europe, had its effect in Poland as well. The coming of the Flagellants spelled the end of the Jewish community. A lament for the massacres that took place records the slaying of Jews in Kalish, Cracow and Glogau. However, the German massacres led in turn to a Jewish migration into Poland. Many settled in Kalish and the Jewish community began to expand once more. There was a period of relative prosperity interrupted by the campaigns of the Hungarian king Ludwig in 1383, while about forty years later, a convocation of the Catholic Church led to the imposition of anti-Jewish regulations including the wearing of the Jewish badge.

From the middle of the 14th century, Jews began to appear more frequently by name, being referred to in various legal records as claiming the payment of debts, most of which are by no means considerable.

Names found in these lists include: Michael, Abraham, Yehudya, David, Daniel, Shabdai (Sabbethai), Aaron, Shlomo and Jonah Michael. Women mentioned include: Zelda, Zemela and Dina. Other names are Jurdan, Kavian and Benish.

By the early 15th century, Kalish Jews were engaging in partnerships in respect of various financial transactions. At this time, Jews are referred to in the courts by the names of Iko(Isaac) and Kossol.

Growth of the Community

A Jewish street existed from the middle of the 14th century. As remained customary for many centuries, this was rather more of a square or quarter built around the synagogue which was burnt in the late 16th century. The Jewish Quarter ran from the centre of the city to the walls. Before the fire of 1537, Jews were permitted to hold six houses of their own; other houses being presumably rented. When the city was rebuilt, the number of Jewish houses was increased to eleven. By an agreement reached in 1540, eleven Jewish families were permitted to deal in certain kinds of goods within the Christian quarter and Jews were permitted to maintain four taverns for spirits.

Some years later, the municipality supplied the Jews with piped water against an annual payment of four florins. By 1553, the community already had nineteen houses apart from communal buildings consisting of the community building and offices, dwellings of the rabbi, shamash (beadle) and communal staff, and the hekdesh (communal lazar-house and hostel), the bath-house and mikveh (ritual bath). As time went on, Christian citizens including aldermen sold their houses to the Jews, particularly if they happened to lie within the Jewish Quarter.

In respect of Polish law, the main purpose of the organized Jewish community was to facilitate the collection of taxes and other charges owing to the Government. Internally speaking, the community or kehilla engaged in the conduct and regulation of religious, economic, social and educational affairs and represented its members vis-à-vis Government and municipal authorities. Until well on in the 16th century, each Jewish community was

[Page 19]

an independent body and there was no territorial organization linking them. From time-to-time, they would associate for some ad hoc purpose which was usually temporary.

In the early days the community was headed by an unspecified number of parnassim (wardens), five, four or three in number. When Kasimir the Great confirmed the Kalish Privileges, the leaders of the Kalish community represented the Jews of Great Poland. Thirty years later, the revised Charter which had been extended to all Polish Jewry was, as already mentioned, entrusted to the Jew Falk of Kalish who, presumably, headed the community at that time. Other known leaders of the community were Daniel who was chosen as arbitrator in disputes and David Ogbut of Cracow who built houses in the early part of the fourteen hundreds.

Under King Wladislaw, Jagiello the Jewish community of Kalish, was subjected to increasing economic pressure. In 1430 the King gave instructions that Palta Joseph and Canaan, Jews of Kalish, should appear before the Royal Court because they had not paid taxes to the Treasury from their profits in financial transactions. They did not appear in Court and a fine of fifteen hundred grzebni was imposed upon them. Instances of this kind alarmed the community and led them to resolve to leave the city. The authorities opposed this and demanded that the wealthy Jews of the community should personally guarantee, on pain of a financial fine of sixty grzebni, that those who departed would not take their property with them until they had settled their debts for taxes. Kavian, apparently as community head, and other wealthy Jews gave security for this as we learn from an existing document. About a generation earlier, a false florin had been found in the possession of the Kalish Jew Mark who was flung into prison.

Kavian, together with Jehuda, Smalko and Jurdan, bailed him out on a guarantee of 100 grzebni. Mark proved that he had never gone abroad and had purchased the bad florin from the Kalish citizen, Kurczak, in the belief that it was good money. Kurczak witnessed that Mark's claim was correct and he was acquitted. A similar incident occurred in 1441 to two Jewesses who were also set free.

The number of Jews in Kalish increased following the expulsion from Prague in 1542 though most of those expelled settled in Lublin and Cracow. Jews from Hungary also settled in the city.

The major expansion of Polish Jewry took place in the 15th and 16th centuries when Kalish residents began to move to new communities which offered better economic opportunities. As already noted, the authorities did their best to prevent any mass withdrawal. In this connection, various wealthy Jews were charged with breaches of the law, particularly in 1448 and escaped imprisonment only by paying large sums as security. At this time, the community as such paid an annual tax of one hundred grzebni to the king's secretary, Canon Martin Swenka who was himself heavily burdened with debt. The tax was paid by the Canon promised the community that he would obtain a royal privilege exempting it from all further taxation for two years together with the assistance of Government officials in collecting debts owed by Christians to the Jews. A special agreement in this connection was signed in 1445. However, it is not known whether the Canon succeeded

[Page 20]

in carrying out his part. In 1453, a joint delegation from seven communities including Kalish endeavoured to obtain a confirmation of their privileges at the royal chancellery. After six years of intercession and considerable financial outlay, a memorandum summarizing all privileges was prepared and was signed by the reigning monarch in respect of the Jews of Great Poland and Small Poland. However, under ecclesiastical pressure, the privileges were withdrawn soon after.

The first named rabbi of the Jews was Michael who is referred to in a document of 1427. Somewhat later, reference is made to the Jewish judge Abraham Kapust of Pesari and the Jewish assessors Michael and Palty. At about the same time, there were three shamashim or beadles of the court and the community, Abraham, Shmuel and Israel by name, whose quarrels brought them before the civil court and are a matter of record.

In 1458, there was a fire in the course of which the Jewish houses were all burnt and their property pillaged. During the same year, they had to pay the rector of the general school, apparently for preventing his older pupils from engaging in anti-Jewish riots of the kind known as “schueler geleif”. Riots broke out in the year 1542 and were participated in not only by the rabble but also by various notables of the city. The rioters burst into the synagogue and profaned the Torah Scrolls. The heads of the Jewish community blamed the Municipal Council. The latter in return prohibited the Jews from appearing in public or even leaving their dwellings from Good Friday to Easter Monday inclusive. At that time, the Government authorities warned the Municipality that they would have to pay a fine of two thousand grzebni if disturbances broke out again. However, there were more riots in 1565 when three Jews were killed. The municipal authorities did not appear in court and the accused were not punished.

Some years earlier, the Jews of Kalish had been accused of stealing the Host from the church and a number were sentenced to death. In 1571, legal steps were taken by the brothers Shmuel and Moshe Mordechovitch and the rabbi against the citizens of Kalish on account of the murder of their brother Elia by a student. The matter was settled in due course by payment of compensation. A few years later, the following brief entry is found in the Pinkas (Record Book) of the Cracow community: “In the Holy Congregation of Kalish, the students destroyed the synagogue and took the Torah Scroll and ripped it apart in the year 5351 (1591).

Sixty years earlier, King Zygmunt had set out to protect the Jews against the charges of using Christian blood for religious purposes and had published a declaration confirming all the long-established privileges of the Jews in the cities of Great Poland including Kalish. Once again, the citizens were prohibited from judging the Jews in their courts.

It should be noted that the beginnings of the 15th century were marked by a struggle on the part of the Polish cities to restrict the long-established Jewish freedom for trade. Indeed, in 1521 a delegation of burghers persuaded the king to cancel all privileges. Sometime later, the merchants of Posen broke the Jewish warehouses open in their town and destroyed the content, being followed by similar measures in various other towns including Kalish. In spite of this, Jewish trade re-established itself and between 1550 and 1570

[Page 21]

Jews conducted the greater part of all commercial transactions with the seaport of Danzig as well as in all parts of Poland.

Thus, in 1580-81, the Jews of Kalish transported close to 4,500 fells and skins of all kinds through the Kalish Customs Station; also 972 stones of wool (more than 80% of the total handled): 30 stones of tallow; 295 stones of wax and 5 stones of pepper.

In 1579 the Jews of the city paid less than 1/5th of all local taxes – 130 zloty. Forty Jews paid nothing on account of their poverty meaning that 30% of the Jewish community were poverty-stricken. At that period, the Jews were required to pay: The Jewish poll-tax; extraordinary taxes and Charges and imposts in money, kind and work.

By the middle of the 17th century, Kalish Jews were regular visitors at the Leipzig and Breslau Fairs. On many occasions two or three were sent as representatives of them all but on other occasions, more than thirty Jews went from Kalish. Towards the end of the century, the participation of over six hundred Jews from Poland is recorded. Of these, more than a hundred came from Kalish. The goods they brought to these fairs included fells, furs, etc. Their purchases included textiles, silks, general merchandize and peddler's goods, metals, ironware and jewellery. Asher Abraham and his sons Amshel and Moshe visited the Leipzig Fair regularly from 1686 until 1736. Others were Hanoch, Jacob, Marcus and Moshe belonging to the Hertz, Marcus, Shmerelovitch and Wolf families. There were others who regularly visited the Breslau Fair. Names mentioned include: Asher, Isaac, Jacob Leibel, Michael, Moshe and Shmuel Abraham in the final decades of the 17th century. Marcus Isaac and his son Isaac Marcus Derar, Jacob Barbar, Koppel Goldschmidt (who belonged to the merchant family of Yuchan Alexander), Jacob Ahs, Jacob Lippman, Aaron, Jacob Lazarus, Samuel Yochan and Abraham and Marcus Kaphan. By the turn of the century, a number of Polish Jews including several from Kalish had settled in Breslau.

Jews engaged in the following crafts: Tailors, bakers, weavers, furriers, cord-makers, gold and silversmiths. In the early 16th century, there was a Jewish painter named Beinish (Byenas). An interesting Order issued by King Zygmunt in 1513 provides that Jewish butchers might sell meat which was not kosher only in their own homes, i.e. to non-Jews.

In the middle of the 17th century, Jews were also harness-makers, saddle-makers, blacksmiths, oven-makers, carpenters, bag-makers, rope-makers, engravers and glaziers. There were severe restrictions on craftsmen who were not members of the local guilds, who might, however, sell their wares at fairs and markets. Any journeyman joining a guild paid one zloty and eighteen groszy. The only guild from which Jews were then excluded was that of the Barber-surgeons but presumably this exclusion did not apply within the Jewish community as such. During all this time, the Christian merchants of Kalish were endeavouring to combat their Jewish fellow-townsmen and competitors in every way possible, including measures that can be classed as anti-Semitic and economic boycott.

Regional Government bodies repeatedly demanded that Jews should not be allowed to farm any excise or customs duties and that they should be required to pay the same war tax as others when there was danger of a Tartar invasion

[Page 22]

into the Ukraine, Wolhynia and Podolia. Christian tax farmers who employed Jewish officials and collectors were liable to fines together with the said Jews. Extortion by false charges was also part of the normal scene. In 1620, the Posen community paid various bribes, etc. in this connection on behalf of the Jews of Kalish who were then undergoing a period of economic distress.

During an epidemic in the year 1623, Kalish Jewry suffered from the incitement of a Polish physician named Sebastian Szleszkowski who declared in a work on the pestilence that it was due to “Divine retribution for the protection and defence which the nobility and the municipalities grant to the Jews”. He claimed that the Jewish physicians were systematically poisoning their Christian patients. In several brochures, he continued his violent attacks on Jewish physicians and on those who consulted them in spite of the prohibitions by the Holy Church. From his writings and that of a predecessor who wrote the first Polish anti-Semitic documents, it would appear that there must have been quite a number of Jewish physicians in Poland at the time; and there must have been a certain amount of social intercourse between the Jewish and Polish communities including eating and drinking together. Szleszkowski's solution for the Jewish problem of his time was to isolate the Jews in special villages where they would be treated in the same way as the serfs of the nobility.

Following a false charge by a converted Jew in 1641, Christians broke into the Kalish Synagogue and ripped two Torah Scrolls apart. However, all such events were minor details compared with their fate during the invasion of Poland by the Swedish forces between 1655 and 1660, in addition to the general sufferings of the population. In the course of hostilities, close to 1800 synagogues were destroyed; Torah Scrolls were ripped to pieces and hundreds of Jews were killed. Forty communities were exterminated in Great Poland alone. In Kalish itself, close to 600 Jewish families were slain according to a Hebrew record of the period entitled: “Tit Hayeven”(The Nether Hell) which enumerates those slain in Polish Jewish communities from the Cossack Massacres of 1648 until the end of the Swedish wars in 1660, and arrives at the figure of 600,000 – a stupendous number for those days. However, survivors and new settlers re-established the community with the financial aid of the Posen community and thanks to loans received from Posen, Lissa and Krotoszin as well as certain clergy, totalling 28,000 zloty.

In 1670, the Jews of Kalish and Posen were required to pay 3,000 zloty on account of the poll-tax for the year 1669. During the same year, a number of Jewish refugees from Vienna settled in the town. Five years later, Kalish was visited by one of those fires which were endemic in Polish cities and their Jewish quarters. At about this time, the burghers took steps to ensure that the Jews should be confined within the area specified in 1540. In 1676, King Jan Sobieski confirmed the old Kalish Privileges.

Autonomous Jewish Life

The Jews, who were under royal protection, were regarded as the King's servants. This meant that in terms of the feudal system, they owed direct allegiance to the king alone. The internal source of Jewish life was Jewish Talmudic law as it had evolved throughout the ages under the guidance of

[Page 23]

the Rabbinical authorities known as the Poskim. The constitutional base of Jewish life was the Kalish Privileges of 1264 which prescribed conditions relating to trade, loans at interest, the functions of Jewish and general courts, oaths and general regulations governing the life of the community. Various details in these Privileges might vary from one community to another. For ordinary purposes, the Jewish community existed on the basis of contract; either with the local Municipal Authorities in the case of Free Cities or else with the local Regional or Central Government Authorities.

The Kahal was equivalent to the Municipality. In Kalish, its affairs were conducted by five Parnassim or wardens who were responsible for income and expenditure. They were elected by the community which also laid down the general lines of administration and exercised administrative, financial, judicial and educational functions besides the conduct of worship and religious affairs. The communal representatives represented the Jews vis-à-vis the authorities and the Kahal was the first and in certain cases the highest legal instance. It was organized in: a) The heads or Parnassim, numbering three to five; b) The Worthies and c) The Congregation or representatives of the community.

After the Parnassim or heads were elected, they took an oath of allegiance to the king and state. Their election required official confirmation. It was the practice for them to hold responsibility each for a month in turn, so that the person responsible in the community at any given time was known as the Parnass Hahodesh. The Worthies, three to five in number, could replace the Parnassim or might sit in judgment with a Jewish judge on behalf of the authorities. The number of members in the Kahal seems to have varied from time to time.

There were also the following committees: 1) Major charity wardens, 3-7 in number; 2) Holders of the accounts; 3) Market wardens to supervise weights and measures, ensure that the streets were kept clean, supervise night watchmen and the kashrut of butter, cheese and wine. (It should be remembered that the latter three food items have to be ritually kosher for observant Jewry to this day). Sub-committees supervised animal slaughter and the sale of meat, the hiring of men-servants and maid-servants, etc. 4) School Wardens; 5) Synagogue Wardens; 6) Wardens collecting donations and contributions to support the inhabitants of the Holy Land; 7) Wardens for Pdyon Shevuyim, the redemption of captives particularly during hostilities, revolts, etc., in the 17th century; 8) Communal Fund Wardens; 9) Assessors for the allocation of communal taxes; 10) Heads of the Artisan Societies, i.e. the Jewish Guilds.

Other committees were set up ad hoc to ensure the observation of sumptuary laws (against excessive display and extravagance in clothing, etc.,) to supervise morals, etc. Lawsuits between Jews were brought before the Dayanim or subordinate Rabbinical judges. There were two or three Batei Din or Rabbinical Courts, each composed of 3-5 Dayanim.

Persons were elected to office for a period of one year. Elections were held in all communities including Kalish on the 3rd day of Passover, i.e. on the first of the intermediate days. Former office holders might be re-elected.

The method of election known in Posen and apparently also used in Kalish

[Page 24]

was as follows: The heads of the community placed 21 names of leading householders in the ballot box and withdrew seven by lot. These were the referees who appointed the new Kahal and also gave them general instructions.

Both religious and civil functionaries were required by the community. The Rabbi headed the communal hierarchy and was not only the leading official but likewise the spiritual authority and supervisor of the religious and general cultural life of his congregation. In the 16th century, the Rabbis were usually members of well-to-do families who were not concerned with salary and were therefore completely independent of the heads and wardens of the congregation. This helped to secure the traditional status of the rabbi in Eastern Europe until the time of the Catastrophe, even though the status in question began to decline in the 17th and 18th centuries. Though the names of the early Kalish rabbis are not known, they are referred to in various sources in terms of very high respect. It is interesting to note that the community never appointed one of its own members to serve as its rabbi.

From the early 17th century on, the known rabbis of the city included quite a number of outstanding figures who played a prominent part both in rabbinical and public affairs and also in the literature of their period. A leading rabbi, born in Kalish, was Jacob ben Joseph Striemer. He was a follower of Sabbethai Zvi until the latter's apostasy when he became violently anti-Sabbatian. Subsequently, he conducted a Talmud Torah (Jewish day school) in Adrianople, Turkey and is recorded as one of the Ashkenazi sages in Jerusalem in the year 1700.

Under Polish law, the rabbi was authorized to issue decisions on all matters brought before him in accordance with the laws of Israel. The only authority to whom he was responsible was the king himself. He signed all the resolutions of the Kahal, conducted the elections and ensured that they were properly carried out. However, he was selected and appointed by the Parnassim and was, therefore, dependent upon them unless he was himself well-to-do.

When elected, the rabbi received a certificate of appointment specifying his rights and duties, the fees he might charge for weddings, wills, issuing legal judgements and also the businesses in which members of his family were allowed to engage. In the 17th and 18th centuries, his salary in communities as large as Kalish varied from 3-10 zloty per week. He was also paid for the two sermons which he traditionally delivered on the Sabbath before Passover and the Sabbath between the New Year and the Day of Atonement.

Mention should also be made of the Head of the Yeshiva or Talmudical Academy who might sometimes compete with the local rabbi in respect of the precedence and authority deriving from his learning. In many cases, the two offices were combined.

Other officials included: the communal scribe or secretary who needed to be able to speak Polish at least. For public affairs, a special Christian official who was sometimes a nobleman assisted him in the Civil Courts and Regional Government offices. There were Shamashim (Beadles or attendants of various kinds) for the synagogue, the cemetery, the tax assessors, the

[Page 25]

Jewish and general court. The Court Shamash developed in due course into the Shtadlan or intermediary with the non-Jewish authorities. The first known in Kalish was Reb Leib Shtadlan who exercised this function for many years at the end of the 17th century, and from 1700-1709 was also Shtadlan in Posen where he received 5 gulden a week for his services.

The community also maintained a physician, apothecary, barber-surgeons, a midwife, watchmen, collectors, messengers and postmen. Charitable activities were extensive including charity for the local poor and wayfarers, support for indigent householders, supervision of young Jewish students and orphans, dowries for brides, medical aid and hospitalisation. Physicians with medical degrees are referred to only in the 18th century but the physician, Moshe ben Benjamin Wolf of Mezeritch, who was in Kalish in the second half of the 18th century, wrote medical works including one containing extensive passages in German.

The expenses of the community included the taxes paid to the Government treasury. The regular taxes required of Jews were:

called Schuelergeleif). Certain sums are clearly recorded as bribes and fines and amercements were paid to occupying forces.

General taxes levied on all town folk (citizens) alike were:

Other sources of income included: Hazaka (occupation rights or permits). These included the right of residence, of possessing a house, plot or dwelling or engaging in trade, handicrafts or selling. One of the purposes of the Hazaka fee was to prevent harmful and unfair competition or price-raising.

Then came payments on weddings, burials, dowries and the grant of certain honorific titles. A property tax was also levied on occasion. If direct taxes were insufficient, taxes were levied on meat, milk, wine, honey and other staple foodstuffs. The community farmed the taxes out and on occasion, an income tax was also levied.

After the vicissitudes of the mid-17th century, however, all these sources proved inadequate and the Kalish community had to borrow loans repeatedly in the early part of the 18th century. Many of these loans were raised from Christians in Breslau.

A Kalish Jew named Gad Uziel is named as one of the first assessors when the forerunner of the Council of the Four Lands was set up for the communities of Great Poland in 1519.

Special courts dealing with disputes in Fairs and Markets were established, and by the early 16th century had led to the establishment of a Jewish High Court for the whole of Poland. This too helped to lead to the establishment of the Vaad Arba Aratzot which comprised Great Poland, Little Poland, Reissen (White Russia) and Lithuania. Kalish played a leading part at this council and on the Council of Great Poland itself. It was the practice of the community to send persons who exercised no other communal functions whatsoever to these Councils. By the middle of the 17th century, Kalish held the hegemony over the Council of Great Poland which met once and sometimes twice a year.

The internal economic functions of the latter can be judged by the fact that in 1684 it passed a Takana (Regulation) against monopolization of Jewish trade and imposed a tax on wool purchases to ensure that there would be no unfair competition between purchasers of wool from the big estate owners and nobles. This Regulation reads as follows:

“No visitor is permitted to purchase any goods in communities other than his own save specifically from Jews; and he is not permitted to stay in them more than three days and no longer. Likewise, those who live outside

[Page 27]

the State have no permission to purchase any goods in the vicinity of any community in accordance with the ancient regulation and Jewish villagers are prohibited from taking them on the waggon and carrying them to make the rounds in the small towns in order to purchase any goods whatsoever; and even if they have already purchased goods from Jews who dwell in the villages, then whenever the members of the community come there, it will be first come first served in respect of those goods”. Similar regulations are repeated in more stringent terms from time-to-time.

The Wardens of the Council of Great Poland from Kalish included: Rabbi Samuel ben Yaakov in the 1670's who was also the Parnass of the Council of the Four Lands. He also took steps to redeem a certain Rabbi Yekutiel Kaufman Katz from captivity. Others were: Reb Yitshak Isaac ben Azriel Zelig, son-in-law of Reb Mendel of Kalish, also known as Reb Isaac Reb Mendel; Shlomo ben Hayyim and Reb Yehuda ben Yosef; Yosef ben Arieh, Yehuda Leib Halevi; Shmuel ben Yonah Katz; Shmuel Feivish ben Yehuda Leib Preger, referred to as a scholar; Joseph Halevi of Kalish; Hirsch ben Asher; Meyer ben Yaakov; Michael Pak, a merchant of Kalish who represented Jewry at the Council of the Four Lands in 1602 and was followed in due course by Rabbi Israel ben Nathan Shapiro; Shmuel ben Yaakov; Yehuda Leib Obornik; Meir ben Dov Joseph; Joseph ben Eliahu Venczinek; Mordechai Joseph; Jacob ben Zelig who was imprisoned together with other delegates on account of claims from Breslau against them and Polish Jewry in general; Leibel Feivish; Yitshak known as Isaac ben Azriel and Joseph ben Arieh Yehuda.

In 1685, the Council of Great Poland borrowed loans from the Order of Jesuits in Posen and also owed considerable sums to the Jesuits in Kalish. They paid an annual interest of 7-10% and in 1964, the Council became bankrupt. Creditors, whose numbers were by no means few, attacked Jews on the roads, seized their goods in the fairs and markets, imprisoned them in fortresses and citadels. King Jan Sobleski appointed special commissioners to investigate the debts and spread the period of their repayment over several years. The total debt was then assessed at 400,000 zloty, to be paid off during the following three years. However, the communities were not in a position to meet these commitments.

The matter was dealt with by the Council of the Four Lands in 1699 but dragged on for years and commitments could not be met in 1713 when Isaac Zelig of Kalish, Warden of the Council, tried to obtain a consolidating loan but was unsuccessful. The creditors then began to demand that the Kalish community should pay the debt but the community declared that it was not in a position to do so. In 1714 the Lissa community took over part of the Kalish debts, including interest of more than 12,000 zloty per year and then became the head community of Great Poland.

The Eighteenth Century

In the course of the war between Sweden and Poland in 1706, Kalish was captured and the greater part of the city burnt down. A contemporary report by the Municipality reads as follows: “In the city of Kalish, all our Jewish houses were completely burnt to ashes together with the Synagogue, except

[Page 28]

for two houses by the wall; all the buildings and the ware. On Sunday evening before the Festival of the Birth of the Holy Virgin, this tremendous fire burst out in the square of Kalish. It spread so far and wide that only the plots were left instead of the houses. In this conflagration, forty-five were burnt as it was impossible to escape from the terrible flames”.

Two years later, an epidemic broke out during Passover on such a scale that the Lissa community prohibited all visits to kalish. The inhabitants fled to the fields and forests. The neighbouring communities came to their aid. It is reported that 450 persons died. The community of Posen was asked to aid and gave 1,000 zloty. In the year 1727, the communities of Posen, Lissa and Krotoszyn made a grant of 28,000 zloty to the impoverished community of Kalish.

The fire of 1706 was followed by fresh conflagrations in 1710, 1712 and 1713, while epidemics spread in 1708 and 1712. At this time, there were about 100 Jews in a total population of 700, the lowest known population in the history of the city.

In 1754, the townsfolk charged the Jews with endangering their lives and existence. Large fines were paid and the Jews escaped from the danger but not details are known.

The first authentic figures on the population date from 1765 when there were 809 Jews and 52 babies aged less than a year. There were 408 men and 401 women. Of these, 197 were married; 175 of the being independent and 22 being sons and sons-in-laws living with parents; 188 unmarried sons; 23 servants, apprentices and orphans. There were 175 married women, 22 married daughters and brides, 18 widows, 15 independent, 3 divorced, 174 unmarried girls, 12 servants and orphans. There were 215 families in all – 190 being independent and 25 living with the parents.

Since Jews used to evade censuses for religious and other reasons, it has been estimated that the total number in Kalish at the time may have been over 1,000.

More than another thousand lived in 8 hamlets and 8 villages in the vicinity, while the total number of Jews in the Kalish Government District was 6,465 in 29 cities which constituted 23 communities. (Certain small congregations came under the authority of the larger neighbouring communities).

Ten years later, there were 670 Jews, not including infants, liable to the poll-tax. It may be assumed that the Jewish population was still at around 900. For the year 1789, we have reliable figures showing that there were at the time 880 Jews, 334 being men, 318 women, 126 boys of whom 75 were more than a year old and 102 girls of whom 53 were more than a year old. It would appear that the entry of poor and sick Jews to the city was prohibited.

When the Prussian authorities conducted a census in 1793, there were 1,706 Jews. Some doubt is cast on the latter figure by a Palish historian who calculates that there must have been a total of 1,300 Jews in 1789. In 1792, another fire burst out and not a single house was left standing in the Jewish Quarter which was a separate part of the city. Special municipal regulations of 1755 required the Jews to keep the Quarter clean and clear gutters and drainpipes on pain of fine and imprisonment.

Throughout the century, the Jewish merchants faced the fierce competition

[Page 29]

of the townsfolk and citizens. The Christian Guilds did their best to reduce the opportunities and possibilities of the Jewish traders in every way possible. Countless municipal regulations attest to this.

Jewish liquor merchants met with serious competition from a group of Greek merchants who settled in Kalish in the middle of the 18th century coming from Macedonia where they had been persecuted by the Turks. In general, Jewish liquor traders had to struggle very severely against the repressive measures of the families of hereditary brewers in the city.

In the course of time Jews also dealt in cattle, horses, oxen, grain and agricultural produce. There was a constant coming and going of agents who visited large estates and villages to purchase these wares and the Christian wholesalers combatted this trade continuously. In the year 1778, for instance, the community spent 6,000 zloty exclusively on trials with the municipal authorities in this connection. Shopkeepers and storekeepers who rented places in the Market Square were subjected to all kinds of restrictions and prohibitions by the municipal authorities and Christian associations in respect of kinds of goods to be sold, weight, prices and hours of sale. They faced constant threats of confiscation and expulsion.

In spite of this, the census of 1765 gives the following figures about the employment of heads of families: Trade 18,-: 13 of whom were merchants; 2 shopkeepers, 2 hawkers and 1 agent; crafts: 79, of which 30 in free professions; and 63 heads of families without any profession.

Of 443 families recorded in 1786, 141 were householders and permanent residents; 99 were not permanent. Forty-two engaged in trade; 50 were agents and 5 had inns. As against 21% of the Jewish population engaged in trade, only 9% of the Poles were so engaged.

In 1789 the figures were as follows: Householders 69, or 153 with wives and children; merchants 70, or 174 with wives and children; craftsmen 100, or 234 with wives and children; innkeepers 4 or 17 with wives and children; shopkeepers 40, or 122 with wives and children; agents 30, or 107 with wives and children; apprentices and assistants 21, or 33 with wives and children. At this time, 43% of Jewish families made their living by trade, liquor and as agents. The corresponding percentage for Christian families was 10%.

The Jews traded in horses, cattle, grain and agricultural produce. In that century, the Jews also engaged in wholesale textile trade having wool woven for them by individual weavers or Polish workshops. They exported to Moravia, Bohemia, Silesia and Saxony. There were some Jews who leased flocks of sheep. Jews opened soap factories.

When the Polish Treasury took over the manufacture of tobacco, a workshop was opened in Kalish and Jews engaged in the sale of the product. Monetary and credit activities were also carried on. Loans were granted to Christian and Greek merchants and others at an annual interest of 7% or more, often against pledges of silver, gold and jewellery. At the same time, Jewish merchants borrowed from wealthy citizens, nobles, etc., including clergymen who charged a high rate of interest. There were constant relations with Silesia, particularly with Breslau where the Jewish merchants of Kalish established a synagogue of their own in 1698, maintaining a trustee and shtadlan to safeguard their

[Page 30]

interest. By the beginning of the 18th century, there were 6 such representatives in Breslau from Poland. In 1722 there were 8 and at one time there were even 12. The Breslau authorities authorized only 3 in 1738.

A report dated 1779 on the Customs offices in the Kalish District and Kalish itself gives an account of the local and other Jewish merchants who returned from Frankfurt. A representative of the Kalish Jews was required to take oath that cattle imported were healthy. Agents made the rounds of the city and environs purchasing clothes, gold, silver and jewels, also agricultural produce, horses, cattle, liquor, etc. The Municipality took special steps to ensure that Jewish shopkeepers would not sell goods on the roads and in the streets. All trade had to be conducted in the market-place.

Jewish craftsmen listed in the 1765 census were: 27 tailors, 2 hat-makers, 16 furriers, 4 embroiderers, 10 cord makers, 2 glaziers, 1 bookbinder, 8 craftsmen of various kinds and 9 butchers. These Jewish craftsmen suffered from the persecution of the various Christian craft guilds which insisted that according to the privileges awarded to them, the Jews were not permitted to engage in various trades, particularly tailoring. In 1713, an agreement was reached between the Tailors' Guild and the Jewish tailors whereby Jewish residents of Kalish might engage in tailoring in return for an annual payment of 14 zloty to the Guild. In 1774, another agreement was reached whereby Shlomo, the Women's Tailor, was the only Jew authorized to engage in this calling against an annual payment of 3 zloty to the Guild. In the earlier part of the 17th century, indeed, the Jewish butchers had been authorized to maintain 12 butcher shops against an annual payment of 300 zloty while the Jewish furriers paid 16 zloty annually to the Furriers Guild.

By the second half of the 18th century, there were also Jewish shoemakers, saddle-makers and button-makers. In 1786 there were 101 Jewish craftsmen in Kalish as against 106 Christians. In 1789 there were 100 Jewish craftsmen with 98 wives, 16 boys and 20 girls or 234 persons in all, constituting 26.6% of the Jewish population. They were organized in societies which had a guild character and charged the same rates as the Christian guilds.

Although there was no Hebrew printing press in Kalish itself, men from Kalish are referred to throughout this period as printers, typesetters, proof-readers and publishers. Thus, in 1589, Abraham ben Yitshak Kera Ashkenazi of Kalish printed books in Salonica and afterwards in Venice and Mantua. In 1690, there was a type-setter in Amsterdam named Leib ben Naphtali Hirsch Fass of Kalish. Others at that time in Berlin were Shneur Zalman ben Yehonatan Katz and Hehoshua ben Avigdor, both from Kalish. The 18th century records Benjamin Sabbethai Bass, a printer; Zvi Hirsch ben Kalonymos in Duehrenfuerth; Kalonymos Baltzabon; Yitshak ben Eliahu in Frankfurt-on-Main; Benjamin ben Yehiel; Ezekiel ben Yaakov; Kalonymos ben Yehuda Leib, typesetter in Salonica and Zvi ben Reb Kalonymos Katz in Frankfurt-on-Main.

Mention should also be made of religious and communal functionaries including: Rabbis and Dayanim, cantors, sextons, slaughterers, beadles, shtadlanim, Torah scribes, barber-surgeons and barbers.

In 1778, a municipal committee for good order was set up. Among other duties, its task was to end the disputes and trials between Jews and townsfolk

[Page 31]

and restore peace between them. The committee achieved this purpose and an agreement was reached and signed between the Jewish community and the municipal authorities. The Jewish committee undertook to pay 1,100 zloty for the billeting of troops, for the water-pipe, the cemetery, synagogue, hospital and butcher shops at a monthly rate of 100 zloty. It was agreed that the billeting tax should cease if the troops left the town and payment would then be made pro rata to the number remaining. However, if so many soldiers arrived that the Christians could not billet them alone; the Jews would also have to do their share.

Jewish merchants might trade in accordance with their ancient privileges but were not permitted to import liquor from Poland or abroad for blending and sale, with the exception of kosher wine for their own requirements. They might sell stock fish and honey. They had to take precautions not to harm Christian merchants. The community might maintain 4 drinking houses for beer and spirits but each might consist only of one room and be in the hands of one keeper. They had to buy their spirits and beer from Kalish citizens on pain of a fine to the municipality. However, in case of a shortage in Kalish, the municipality had to permit purchase elsewhere.

The Jews were guaranteed a fixed price of 6 zloty per barrel of liquor and any attempt by Kalish citizens to raise the price and/or lower the quality, would be punishable by a fine. Jews might not set up beer breweries or distilleries; they might not manufacture spirits in private houses or keep taverns or stables.

The tailoring and butchering agreements already established were confirmed though the annual fee for the butcher shops was raised afterwards to 400 zloty. An agreement of the Butcher's Guild required them to pay a levy of almost 1,100 zloty to the Furrier's Guild as before though there had never been any specific agreement. Two Jews only were permitted to sell salt in two houses of the Jewish Quarter to Jews and Christians alike, provided that weights were accurate and that the price was the same as among the Christian merchants. In return, the community had to pay the Salt-sellers' Guild 2 lbs of wax every three months. If a tannery were set up in Kalish, the Jews would not be permitted to purchase skins and export them from the city Jews were forbidden to import medicines and poisons.

Additional regulations prohibited Jews from abroad and residing temporarily in Kalish from engaging in any trade. No Jewish resident could serve as host to a Jew from abroad without the knowledge of the municipality. The gatekeepers were required to check suspect alien Jews at the gates of the city and bring them to the Mayor or Chief of Police. Jews had to share in the expenses of the water conduit leading to their own well and specially constructed for them. Jews were prohibited forever from purchasing, leasing and requisitioning houses, plots, shops in the centre of the city and all its streets and suburbs which had hitherto been inhabited by Christians, save for those buildings which they already held on some legal basis. A special resolution was adopted regarding Jewish beggars on the assumption that the latter spread contagious diseases and engaged in thievery. The

[Page 32]

committee recommended that they should not be admitted to the city but detained at the gates, given communal charity and sent away. The community could maintain only crippled poor who were resident in their hospital. They Police Chief had to ensure several times a year that the Jews were obeying this resolution, otherwise the communal heads would be fined. Those beggars caught would have to clean the streets for a month and would then be expelled, but not by vehicle.

The Municipality and community were required to completely prohibit the Jews from admitting wayfarers into their homes without municipal permission and without the careful investigation by each one. The Jews were specially enjoined to keep their streets clean and in good repair. They had to maintain fire-extinguishing equipment at their own expense.

The implementation of this agreement was entrusted to the municipal authorities and was thenceforth used systematically in order to restrict the activities of the Jewish community and individuals for a full century to come until the sixties of the following century.

Towards the end of the 18th century, liberal and enlightened circles in Poland discussed the social, economic and political reorganization of their country and devoted much thought to the Jewish question. At the Great and Final Seim of Sovereign Poland (1788-1792) the cities, including Kalish, put forward a plan for setting up special Jewish craft and merchant societies subject to the supervision of the Christian associations. This ran counter to most of the plans which aimed to eliminate Jewish distinctiveness.

Throughout the century, the amount paid in poll-tax varied very considerably. Most of the figures are for the entire Posen-Kalish region and vary from almost 18,000 zloty in 1717 to over 35,000 zloty in 1734. In 1714, the city itself seems to have paid over 7,000 zloty; in 1756 the sum was 1,363; eight years later it was 39 zloty more and in 1790 it was 2,147 zloty. Whether this reflects difficulties in collection or changes in the Jewish population, is no longer clear. In addition, a number of special payments were made to the Municipality for the cemetery and the water conduit in lieu of billeting soldiers, etc. When there were no troops in Kalish, the Municipality used this amount to support the poor, orphans, widows and cripples. Jewish workshops made special payments to the guilds as already reported.

Between the years 1778 and 1792, the community paid a total of over 100,000 zloty for gifts and occasional outlay (presumably bribery and douçeurs) for various high officials and as the cost of legal proceedings. Total debts of the community to nobles, clergymen and the Committee of National Education, as recorded under a law of 1792, amounted to over 306,000 zloty on which an interest of more than 200,000 zloty was owed. Of this total, the Committee had paid almost 23,000 zloty principal and almost 54,000 zloty interest, leaving a debt of over 293,000 zloty in principal and close on 147,000 zloty in interest. Creditors among the clergy included the Jesuits, Franciscans, Bernardines, Lateran Canons, Hospital Canons and the Collegiate in Kalish.

It seems that there must have been repeated disputes between the community heads and the rabbis as can be judged by the fact that many rabbis stayed for only short periods. Between 1714 and 1763, at least five rabbis

[Page 33]

left the city on this account. When the Polish authorities set about liquidating the Jewish regional autonomous institutions in 1764, the representatives of Kalish were appointed liquidators.

In the middle of the century, the Church controlled the country and Kalish together with many other communities and the Jews suffered from anti-Jewish incitement and Blood Libel cases. In 1763, seven Jews, five men and two women, were charged with murdering a Christian girl for ritual purposes. Details of the trial are unknown, but two Jews were sentenced to having their hands and heads cut off! (After conversion, they were merely beheaded). A third Jew was flung into a lime-pit and afterwards beheaded. One Jewess was sentenced to decapitation but after converting, only her hand was cut off. A fourth Jew refused to convert and was strangled, the guards mutilated his corpse dragging it the entire length of the Jewish street to the crossroads where they flung it to the dogs! The sixth and seventh victims, a man and a woman, refused to convert and were sentenced to beheading and the cutting off of their hands. The steps taken by the community are unknown.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the Redlich Family began to emerge and to move towards the prominent part they played in developing local industry during the 19th century. The first special privilege was issued to Samuel Joseph Redlich in 1793, during the final days of independent Poland. King Stanislaw Augustus Poniatowski took him under his special protection and gave him permission to trade and store goods freely. He, his wife and heirs were exempt from all mistreatment and were entitled to display silks, textiles and wool of all kinds during fairs in Kalish and any other city in the region, in shops and any public places. They could sell and exchange goods, brew beer and distil spirits and enjoy all the legal rights and privileges of the citizens of Kalish.

Under Prussia, 1793-1806.

When Poland was partitioned for the second time in 1793, Prussia received the entire Western part of the country including the district in which Kalish lies. The territory contained 1,200,000 inhabitants and was called South Prussia. A treasury official was promptly given the task of ascertaining the rights of all communities and their institutions as well as the incomes of the Jews. In his report, he stated that he found appreciable numbers of Jewish craftsmen such as book-binders, butchers, shopkeepers, gold and silversmiths, tinkers, cord makers, furriers, tailors and mechanics. There were 1159 Jewish merchants and 1739 non-Jewish merchants in the whole of South Prussia who were required to keep accounts.

The King of Prussia visited Kalish in October, 1793 and was received at a league's distance from the town by two groups of young Jews, one in green and the other in red Turkish garb. The heads of the community, led by the Jewish physician, Dr. Mayer and his eight-year-old son, gathered at the Triumphal Arch erected to welcome the monarch. The Jews who rode out to greet him arranged themselves in a circle around the arch, and the physician's son presented a poem which was received with thanks by the king.

[Page 34]

In 1800, there were 16,230 Jews in the department of Kalish. In Kalish itself, the Jews were 41% of the population and were chiefly engaged in commerce, the entire textile trade being in their hands. The weavers complained that the Jews paid them badly and lent them money at high interest. Trade in wool was also in Jewish hands and the weavers complained at the high cost of the raw material. At the same time, the Jews were more than 50% of all craftsmen in the city. They included tailors, shoemakers, bookbinders, glaziers, gold and silversmiths, button makers, furriers, hat makers, cord makers, musicians and weavers. The authorities refer to the high quality of the work done by the Jewish craftsmen and their satisfactory earnings. Dr. Jonah Mayer was the head of the community.

The communal heads at the time included: Yehuda Leib Baruch; Naphtali ben Moshe Shimon; Yehuda Leib Crystal; Jacob Traube, Shimon Levy and Zalman Rosenbloom.

The Prussian Government wished to take steps to bring the Jewish community in line, more or less, with the Western world. A special decree was issued prohibiting marriage without Government permission. The age of the bridegroom was fixed at 25 and he was required to prove that he possessed property worth 3,000 thaler in ready money or property or that he was a craftsman who could make a living for a family. Such wedding licenses were issued only to those who could prove that their parents and grandparents had been regular inhabitants of South Prussia. Bridegroom and bride were required to undertake not to settle in any village or set up a factory. The Jewish communities decided to take joint steps against this measure.

A debate ensued among the higher Prussian officials. A circular was sent to them asking their opinions about the transfer of Jews from villages to cities, even those having the ancient privilege of not permitting Jewish residents; what were the most desirable conditions of their employment; whether they might be allowed to engage in all their crafts or the latter should be restricted; and finally, what the education of the children was to be.

It was generally agreed that Jewish residence should be permitted everywhere in order to promote urban development. Some recommended the transfer of Jews to agriculture. Many wished Jewish craftsmen to be given the same rights as Christians and objected to restrictions on craft occupations and wholesale trade, but wished to leave the monopoly in the hands of Christians and to restrict peddling. The official language of Jewish institutions was to be German which was also to become the language of instruction in their schools.

A Ministerial Memorandum of 1795 sent to the King of Prussia expressed opposition to the marriage restrictions proposed in 1793 and suggested that marriage be permitted without restriction against a registration of fee of 1-5 thalers. Jews should likewise be granted freedom of religion and charged the same tax as Christians, with the exception of a Recruits' Tax. The poll-tax should be replaced by a billeting tax.

These proposals were confirmed and became law in June, 1795. The Prussian Government then planned to introduce a reform in Jewish affairs and

[Page 35]

demanded copies of all documents granting privileges as well as attested information on: Cities where Jews might not settle; the source of privileges and whether they had been abolished expressly or tacitly; the attitudes of the charters given to the guilds regarding Jews and the Jewish privileges regarding Christians and how far the latter were still valid.

A general list of mutual privileges of Jews, Municipalities and Guilds was then drawn up. The Jewish communities including Kalish had already tried to obtain confirmation of their Polish charters but the Government had adopted the political attitude of “restricting the Jews in respect of the former legislation”. They were permitted to renounce their autonomous organization in communities. The latter, it was true, had already begun to decline in the 18th century, with the resultant partial collapse of Jewish autonomy.

While the Jews wished to preserve the legal basis of the communities and hence the legislation from which they derived in order to retain a certain measure of autonomy, the Prussian authorities, in line with the general attitude of Western Europe at the time, wished to eliminate autonomy to adapt Jewish life to that of Jews in Prussia and Silesia and expedite the process of their adaptation and assimilation in German culture. It should be remembered that Prussia had annexed territories containing more than 150,000 Jews. While they were well aware of their economic importance, they wished to adapt them to their own style of life.

In 1797, the General Regulations for the Jews granted rights of domicile in the new areas only to those who had already lived there at the time of the occupation and to professional men. Others were required to leave the territory within a fixed time. The remainder were to be registered and would receive “letters of protection” (Schützbriefe). Taxation was increased. The Polish poll-tax was raised from 3 to 10 zloty and the Jews were required to pay the following:

[Page 36]

depriving the community of what had hitherto been its right. Thus, the Prussians abolished the Jewish community or Kehilla which they regarded as the principal obstacle in carrying out their fiscal and economic policy.

While the Jews were promised improvements as their cultural situation improved in the Polish provinces, prohibitions were there from the beginning. Jew could not engage in interest transactions and all loans had to be arranged in court. Spirits could not be sold to peasants on credit nor could Jews sell them any goods except for agricultural requirements. All peddling was prohibited. The number of merchants was restricted. Crafts were permitted only in the towns and were prohibited in villages. It was hinted that the occupations in which the Jews engaged could not ensure them a living and they were, therefore, to be permitted to engage in agriculture and obtain uncultivated land sufficient for the upkeep of a village family. Anybody undertaking to purchase land on his own account could profit from all advantages, being exempt from taxes for a number of years and could employ Christians for the first three years. Jews were to be encouraged to engage in agriculture, lease estates and breweries and engage in industrial enterprises. The Government would maintain schools where the youngsters would study under Government supervision and in accordance with Government instructions.

These regulations were received with fear and mistrust by the Jews. In Kalish, they meant the destruction of Jewish trade. At the time, almost all the merchants were Jews and many were engaged in crafts as well. The entire retail trade in the surrounding villages was in Jewish hands.

The leaders of the communities and a number of outstanding rabbis held a meeting at the end of August, 1797 to determine the attitude to be adopted towards these regulations. The conference was attended by 31 representatives of communities of whom Yehuda Leib Barash and Moshe Shimon represented Kalish. After careful deliberations, they resolved to request the King to conduct a thorough on -going investigation into the state of the Jews. They wrote as follows:

“Some months ago, there appeared in print a Règlement by our pious Lord and King and Glorious Majesty regarding the special position of Israel under the rule of his Government in the state of South Prussia and New East Prussia, and in each district and region of the said states. Indeed, true utterances cannot be denied for the eyes of the Hebrew have been opened to see therein, with the aid of His Blessed Name, the kind-heartedness of His Excellent Majesty and the ministers. However, in respect of the matter of the residence of the congregation of Israel in the said state since ancient times, and the ways of their livelihood, coming and going, and that, henceforth, matters of conduct are to be innovated in accordance with what is written at certain points in the said Règlement, there may, Heaven forbid, come about a destruction of faith and, Heaven forbid, a deficiency may be brought about in our livelihoods so that the hands may be enfeebled, Heaven forbid.[Page 37]Therefore, the men of the said states have set their hearts to gather together several men from the communities in the districts of the said states to discuss, counsel and seek. His Name aiding, to find an opportunity

whereby to appear before the King and entreat him to grant his grace and give instructions for matters to be investigated by his ministers and counsellors and to inquire thoroughly into the real state of Israel by greater enquiry and investigation as far as possible. We then hope that with His Name's aid, they will extend the wings of their loving kindness and indeed establish the pillars of faith on their firm pedestals…and the sources of livelihood and food will not be dammed up if the desirable approach is followed. To this purpose, we have gathered together and come hither to the Holy Congregation of Kleczow, men from the near and distant cities of the aforesaid states, with adequate power and authorization from the leaders and heads of the congregations, to take wise counsel together regarding the efforts to be made on behalf of Israel with the Name's aid”.The communal representatives were required to select a delegation to proceed to Berlin and act as a Committee of Ways and Means about raising funds for the cost of the journey; to which each community was required to contribute. A levy consisting of a third of the Polish poll-tax was imposed on each individual and the money was to be sent to certain specified trustees. Discussions were suspended as the representatives had to return home without going into full details. The participants agreed to meet at the Fair to be held in Frankfurt-on-the-Oder some months later where they would devote one or two days to this matter and choose representatives. Those present in Frankfurt would constitute a quorum for the purpose, but could co-opt another eleven suitable persons.

A delegation of three proceeded to Berlin in October, 1797 and the following month received a reply from the Government. This was moderate and included a number of ameliorations in favour of the Jews. In the course of time, the higher officials had to come to realize that many of the clauses of their Règlement could not be implemented under the circumstances. They ceased to expel Jews from the villages, permitted them to settle in all towns and join guilds and facilitated the issue of peddling permits, not only for villagers but also for town-dwellers. In 1800, however, only villagers were permitted to be peddlers once again.

In the Department of Kalish there were six Jewish families who engaged in agriculture. Some were subject to the Polish “squires” while the others cultivated their land well and remained in agriculture. However, the small total number of Jewish farmers led to the abolition of all the special benefits on their behalf at the end of 1803. Various restrictions were then introduced into Jewish trade, peddling in villages and the purchase of agricultural produce.

In the cities, the authorities took steps to ensure that the number of Jews should not exceed the number of Christian merchants. They were also ejected from breweries and inns and were no longer permitted to manufacture liquor and spirits, being required to hand their inns over to the Government and Christian nobles. However, by dint of intercession, this order was deferred for five years until 1808. The new restrictions would have had a very severe effect on the existence of the Jews of Kalish.

By 1804, there were 2,111 Jews in Kalish out of a total population of 7,085. Some of the merchants were gradually acquiring real estate and the authorities

[Page 38]

tended to disregard the fact that they were spreading beyond the Jewish Quarter which, in any case, they wished to expand. However, the local citizens registered a complaint with the Prussian King, objecting to the increase of the Jews and their growing connection with the liquor trade. They demanded that the Jews should be restricted to a special quarter once again.

A Counsellor for taxation was given the task of investigating the situation. He decided that the privileges of 1540 were to be retained; that Jews could dwell outside the Jewish Quarter as sub-tenants and, in general, the authorities would continue their policy of trying to ensure that Jews lived under the same conditions as non-Jews. At the same time, dwellings in Christian houses could be rented to Jews only with the special permission of the authorities and the Counsellor assured the citizens that the latter would prevent any change for the worse on either side. All this time, the struggle of Kalish Jewry for the right of making a living and residing in Christian streets continued at the day-to-day level.

Meanwhile, there were political developments elsewhere. In the autumn of 1806, Prussia was defeated at the Battle of Jena and Napoleon began a triumphal Eastern march – the French entering Warsaw at the end of October, 1806. The Jews joined the Poles in welcoming the French forces with food, drink and songs of praise in Kalish and elsewhere.

The Duchy of Poland, 1807-1815

In the summer of 1807, the Treaty of Tilsit, signed by Napoleon I and the Russian Tsar Alexander I, provided for the establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw within the areas occupied by Prussia after the Second and Third Partitions of Poland. The Duchy was divided into six Departments of which Kalish was one. In 1808, there were 2,535 Jews in the city, or 41% of the population. Of the family heads, 161 engaged in commerce; 16 in the sale of liquors and 3 sold salt. Others were wholesalers like Joseph Samuel Redlich already mentioned; Samuel Sachs; Isaiah Mamlok; Philip Sachs and Simeon Peretz. In 1814, Getz Isser Loewe of Hamburg, afterwards known as Gustav Adolph, settled in Kalish and became one of the first local Jewish industrialists. Redlich engaged in extensive transactions in liquor and textiles and also exported grain and cattle.

In 1813, there were changes in the Russian-German frontier. A Customs Station was opened near Kalish and the new Jewish occupation of Customs Agent began. There were 115 family heads who were tailors as well as many under very difficult conditions and the community as such was ore poverty-stricken than ever, although some of the richer Jews did well.

Under the constitution introduced by Napoleon, all citizens were granted equal rights. This included the Jews. However, the officials charged with implementing this constitution did their best to prevent any true equality of rights in practice. In addition, the Jews did not want complete equality. What they desired was religious freedom and the abolition of such disabilities as prohibition of residence in various cities and streets; the prohibition to engage in certain branches of livelihood and the abolition of the special Jewish taxes and levies. Full equality would have imposed the same duties

[Page 39]

upon them as on other citizens such as conscription to the army which would have involved the desecration of the Sabbath, the eating of trefa (ritually unfit) food, shaving of the beard and ear-locks, etc.

The following year, the implementation of the Equal Rights Clause was deferred for a period of 10 years. It was pointed out that the differences which isolated the Jews from the rest of the population prevented them from benefitting from civil liberties and made them unsuitable for military service. At the same time, the authorities began to whittle their civil rights away. They were forbidden to acquire land but merchants were permitted to dwell in the cities, purchase and sell houses and land and leave these to their heirs. Jews could build houses in vacant plots not desired by Christians, provided that the latter agreed to this.

The Polish Minister of Justice masked anti-Jewish principles in a dress of liberalism, claiming that constitutional equality did not of itself transform all residents into citizens with equal rights. The citizen was a man who was faithful to the king and regarded Poland as his homeland. Since the Jews regarded themselves as a separate nation and longed to return to the land of their fathers, they could not be regarded as sons of the homeland.

In the Duchy of Warsaw, the following taxes were levied on the Jews: food tax; kosher meat tax; tolerance tax of 2.5-10 thaler per family according to economic condition; a marriage tax; and all the general economic taxes and levies.

The heaviest burden was the kosher meat tax. It was estimated that the average Jewish family in the Duchy ate 8lbs of meat a week and the tax was 6 groszy/lb; 8 for ducks; 1 for chicken; 8 for goose; 1 zloty for turkey. On an average, every family paid 84 zloty of meat tax per year. When this tax was increased in 1809 from 2,650,000 zloty to almost 3,343,000 zloty, it meant that the 4,346 Jewish families in the department of Kalish (3,309 in the cities and 1,037 in villages) found that they had to pay almost 440,000 zloty/yr.

The kosher meat tax was farmed out at public auction. The farmer was permitted to collect the tax which was fixed by the number of Jewish families. This tax was four times as high as in Austria and the amount fixed by the auction was not collected in any department. The law had provided that if the amount calculated according to the consumption of meat was not reached at the auction, the tax would be imposed on and collected directly from the Jewish population.

This transformed the indirect consumption tax into a direct one. Collection was imposed on the communities and responsibility on their heads. The communities were authorized to impose a ban on those who opposed the tax or refused to pay it. In this way, the Government increased the powers of the community for formal reasons and gave the Parnassim the possibility of misusing those powers. At the same time, this right vis-à-vis the central authorities helped to increase local self-government in some measure. Meetings between sub-prefects and communal representatives to arrange the distribution of the tax among families were transformed in the course of time into Committees which, when necessary, sent delegations to the Central Government in Warsaw or the Grand Duke (the King of Saxony, who resided

[Page 40]

in Dresden), in order to reduce the taxes or diminish the joint responsibility of the Parnassim. However, their efforts proved fruitless. It was then proposed to hold a meeting of Parnassim which would elect a delegation representing the entire Jewish population, as had been done in 1797.

The initiative in this connection was taken by the community of Posen which proposed that the meeting should be deferred for a month as the political situation was unclear and the outcome of the war which was being fought at the time between Austria and the Duchy was not certain. In the end, no conference was held and the distress of the Jews grew worse and worse. The taxes were being collected mercilessly and the economic impoverishment of the masses compelled the Parnassim in Warsaw to take certain steps.