|

[Page 38]

In the village of Zofiovka there was a young couple. They fled as I did from the Germans to Ukraine and settled in the small town. In 1941, the Germans conquered the town and around a year later, they began to dig pits and execute the Jewish population by shooting. The young couple sat and waited, they waited for their day. There was no longer anywhere to escape, there was not enough courage to enter the forest and look for partisans. He was a young handsome man, and she was a young pretty woman. They spoke fluent Polish and broken Yiddish. They lived in a small room. On the table they had a Primus stove and a pot where they cooked a few potatoes three times a day. Two wooden stools stood there, and in the corner a metal bed with a small red cloth pillow with the feathers coming out and two old blankets on it, and books in all the corners, on the table, on the bed, books were everywhere -textbooks. They were both teachers: He was a language teacher, and she was a math teacher. During the Soviet regime, they kept on teaching and adapted themselves. They waited for the war to end, for the Germans to leave Poland when they would return to their home. But the Germans advanced and did not retreat.

I would visit them every day. His name was Mietek and hers was Manya. Both of them were tall, with pale faces, light hair and long noses. They looked like brother and sister. They would tell me about their wonderful youth in Warsaw in high school, at the university, with their rich parents in beautiful rooms full of light. When they would remember their first meeting, they would both fall silent. In the last days before the massacre in the town, I would find them in bed, whole days in bed. He would only get out to prepare something to eat. They were not embarrassed in front of me, and they would embrace each other as if they had just fallen in love now, as if they felt that the end was nearing and so they took advantage of every one of life's moment. She would often say to me: Sankeh, everyone is going to die soon, and you are still so young, you have not even tasted a woman, and you have not felt what love is.” She embraced me with her warm long arms, as though she wanted to grant me a little of her love. In the room, you could feel love mixed with the odor of death, love and death woven together. After that day I did not go there again. I ran away from the odor of love and death and tried to struggle for life.

The little children are waiting, dirty, unwashed, hungry, latching their big eyes onto Daddy and Mommy, not understanding what is happening. There, not far from here, Jews are digging pits for Daddy and Mommy, for the children, and a few Germans are standing with their rifles and shouting, “Shnel, shnel!” (Faster, faster!) This must be finished by two in the afternoon because tomorrow in the morning not even one Jew should be left in the town. Prepare stairs to enter the pit, so it will be possible to lie down one on top of another, according to all the rules of German order.

The room was a mess. Some of the partisans packed their bundles and prepared to go home. The doctor released them, and they were dismissed from the hospital. I said goodbye to them and had tears in my eyes.

“Sankeh, have you gone out of your mind? You stay in bed all day and sleep, and you are not going to the doctor. You did not wash today, you did not eat. What is going on with you? Three years we waited to come to the Great Land. I was already in partisan headquarters today. I received clothing, new American clothes, a few hundred ruble in cash. Now I am going to the offices of the Communist party. They granted me a medal of honor for my fighting, and tomorrow I am going home. Come with me. Doesn't this interest you at all?”

“No, Sashka, I am staying like this on my mattress as long as they let me. I am still not sure, still not sure who I am, where I am, and what is going on with me. Peace be with you and go home.”

Sashka kissed me: “Sankeh, hang in there. Things will be good.” In the evening I lay down covered up over my head with a blanket. I pretended I was sleeping, and I heard the others talking about partisan medals and prizes. They were a little under the influence. They probably drank after they received the medals, and now they sank into a deep sleep.

I could not sleep and turned from side to side. It was quiet in the hospital. We only heard the nurses' footsteps running on the stairs to the rooms of the badly wounded to turn lights on and off. I said to myself, “Sashka will already be home tomorrow. He'll be with his family.” Both those concepts, “home” and “family,” were so strange and faraway for me, as though they belonged to another part of the world. I began to be annoyed by my own behavior. I decided to go to the doctor tomorrow, and now I wanted to sleep. But Good God! Suddenly I heard shots, Tra-ta-ta-ta... too, boom, dzeez... I lifted my head. “Perhaps I am not sane,” I said to myself. But I saw lights, harsh lights outside, and I heard explosions. I jumped off my mattress; I crawled into my pants and ran out onto the porch. Good God! What was I seeing? Real daylight. Thousands of spotlights lit up the skies, the lights moved here and there until I became dizzy. We heard shots, cannons all over the city. The bombs fell in the area of the railroad station. Those were the last German attacks before the retreat. The attack lasted an hour and a half. No panic broke out; everyone slept quietly. I returned to my bed but was hungry and could not fall asleep, so I got up again. I secretly snuck through all the mattresses and field beds and entered the darkness of the kitchen. I found bread and a piece of meat from cans and ate it all with great appetite. I went out to the porch and looked at the city of Kiev. There was calm, as though there had never been German planes here.

That night there was calm in the small Jewish ghetto in the little town of Wo³yñ, but no one slept in the houses after the shot was heard. Only one shot, which echoed throughout the entire village. It happened at eight in the evening. Walking in the street was forbidden. Only two German gendarmes lived in the town and controlled all the Jews. They were Kaiser and Gruber. Kaiser was around 35 years old, medium height, upright. His gait was strong and sure. He saw himself as a son of the master race and saw the others around him as slaves. Gruber was tall and very fat, quiet and moderate. Both of them were always drunk. They loved vodka with honey, which the Jews would give them. To the aid of the two Germans came the Ukrainian police who had served previously in the Soviet regime.

The house where we lived had three rooms. In the first room our family lived: Papa, my brother Chaim, my sister Chava. Also Heniek, my brother's brother-in-law from Warsaw, and I. In the second room a family from Lutsk lived. The Germans exiled the father of the family to work, and he did not return. The mother and three daughters and a son remained. In the third room the family who owned the apartment lived. They made a living from a plot of land where corn was planted and from a few dairy cows.

During the night every room was full of folding beds. On the evening when the shot was heard, we went to bed earlier than any other time. Everyone understood that the last hope of work for the Germans vanished with that shot, which was a sign that there was no longer any need for us and that we would be exterminated together with the other towns in the area. But everyone was silent, lying on their beds in silence. It was dark in the house, but a bright moonlit night and stars could be seen through the slits of the shutters. Who did it? Who was shot? Why smack in the center of the town so everyone would hear? Did he remain where he fell or did they take him away? And what will happen tomorrow morning? And perhaps they have already surrounded all of us? Why were we tempted to believe it would go on endlessly until we would be liberated? Thoughts ran through all our minds unceasingly, but no one said a word. We were lying down awake. Who could sleep?

We heard my brother Chaim's voice. He began to say something. It was like a weight lifted from our hearts because we all waited for someone to say something. “Now, children, I can tell you the whole truth.” Everyone listened tensely.

“He was a nice Jew, good and upright, and also an observant Jew. You should know that I myself heard him pray. He was full of Torah and even knew the Gemara by heart. Indeed Klinger, Dr. Klinger, you too are no longer here. If they murdered you in such a cruel way in the center of town, it means they decided to wipe us all out.”

Among all the refugees who ran away to areas that had been conquered by the Soviets to escape the German murderers, there was a man from Kalish. He settled in a small town, or perhaps a large village, and worked as a local school teacher. He adjusted to the new conditions and lived. Whoever adjusted himself during the time of Soviet rule could get along not badly, and so it was with him. He knew a few languages. He also learned Russian within a short time. He would eat in a restaurant without being choosy, he studied on his own and taught the children of the peasants. He was tall, elegant, and successful in all circles. He was pleased with his work and he waited for the war to end, when the Germans would withdraw and the game would end. But fate wanted something else. The Russians fled immediately and the Germans arrived quickly.

When the Germans came, no more Jewish teachers were needed in Ukrainian villages. All Jews were concentrated in the towns. It was forbidden for Jews to travel on trains, and they were forbidden to move from city to city. The teacher Klinger decided not to go into the Jewish ghetto like all the others, so that he could work on behalf of the Germans and wait until he would be exterminated as a decorated Jew. He felt that with his talents he would still be able to fill an important position in the German government and assist the Jewish population at the same time. Klinger presented himself before the Lutsk area Gebietskommissar [T.N. Area Commissioner of the Third Reich for the Occupied Eastern territories] as an ethnic German. He was tall, light-haired, with an upturned nose, and with fluent German flowing from his mouth. Klinger ignored the fact that at a distance of forty kilometers from Lutsk he was working as a Jew under the Soviet regime. Not much time went by, and we saw a German citizen in the town who went around with the two gendarmes to visit the local tannery plants. Klinger's name changed to Dr. Klinger.

He was the mayor, he controlled the place. He brought raw materials to the factories, received their processed leather and brought it to the Gebietskommissar. The situation in the town improved from day to day. The people worked and lived, peasants came from the surrounding villages, and we led a normal life. Dr. Klinger lived with a rich Jewish family, and he would receive the Germans who came from the big cities there. The Gebietskommissar himself would often visit him there accompanied by high-ranking Gestapo clerks. They placed their orders for processed leather for the German army there and for leather products, such as bags and shoes. In our house we made bags for the Germans. They visited us frequently and even drank vodka. Klinger would come with them to visit us, as he would do in other workshops. When the Ukrainian police took Jews for work, they would go to Dr. Klinger and request that he supply them with Jews. He would send them away saying that the town is under German rule and all the people were already employed. At that time they took thousands of Jews from all the nearby towns for work, from which they never came back again. At that time the Gestapo and Ukrainian police controlled the other towns, and they tortured people daily in the streets, looted their homes, set their stores on fire, while here the Jews led a normal life under the leadership of Dr. Klinger.

My brother Chaim was Dr. Klinger's assistant. He liked him because he was an honest, diligent and courageous person. Klinger would take him along to the Gebietskommissar in Lutsk to deliver merchandise and take new orders.

The year of 1941 went by peacefully in the town. The Jews there said that while the house is burning the clock keeps ticking. In the surrounding towns everything was burning, and here life went on normally. Jews came here from other ghettos, and many people did not believe their stories about the shooting of innocent people. When a Jew came bleeding, worn out, in tatters, and said he had escaped from an open pit, they did not believe him.

This went on until the spring of 1942. For some reason the spring brought evil winds to the town. It seemed Klinger was no longer able to withstand the pressures of the German regime. Foreign Germans appeared with Ukrainian policemen and began to take Jews away to work. The “Judenrat” had to supply people who had no professions. Sixty Jews went every day, but they would return after a few days. Afterward, they confiscated the beasts, the cows, and the goats. They demanded gold, clothes, furs, and other valuables.

One day Chaim returned with Dr. Klinger from Lutsk late at night. When we asked him what was going on, he said the situation was not good. He was sure the situation was serious and that it was necessary to think quickly about what to do. Papa got out of bed and sat with him. At home a small kerosene lamp burned, and a shadow appeared on the wall. We all lay awake in our beds and heard what Chaim told Papa,

“Klinger did not say a word all day. He just sat lost in thought, and from time to time recited Psalms and Kol Nidre. When we went out early in the morning, all the way he hummed 'Damn them...'. When we got there, we ate breakfast, gave them the merchandise, and afterward Dr. Klinger was called to the Gebietskommissar. I heard terrible shouting from there, shouting from the Germans. I did not hear Klinger's voice. Perhaps they hit him. He came out exhausted, and his face was pale. He did not receive new raw materials. He did not say a word, and I did not ask. I am sure now they have already taken him. Who knows if they let him go to sleep at home.”?

Papa sent us out late at night to see if Klinger was home. We went out. It was a foggy night. We slipped away alongside the houses until we arrived at a window of his house. There was light inside, and he sat alone at his table. Papa said he was sure Klinger would run away tonight. But he did not run away. Dr. Klinger did not leave the town. Klinger still wanted to save the town with all his might, but he was not the same Klinger.

We felt the earth burning under our feet. The Jews began to sell everything they could and to hoard gold. Klinger began to drink and was often drunk. He would send the Ukrainian Police out of his house shouting, “I am a German. In my town you will not rob or snatch Jews away to work!” As it was discovered later, a Ukrainian identified him and informed the German regime. At first the Germans did not believe it. They liked him a lot because of his diligence and devoted work on their behalf, and they did not notice that a few thousand Jews who were so beneficial were alive, for there would always be time to exterminate them later. Even if some kind of suspicion lingered in their hearts about Dr. Klinger's ancestry, they did not delve into that so deeply. But this became known to the Ukrainian Police and put pressure on the Gestapo. “Say you are a Jew and you defend Jews. Tell the truth and we will let you live, otherwise we will shoot you like a dog!” Two Gestapo people stood over him holding pistols. Dr. Klinger was quiet, but pale, and he said, “Gentlemen, I am a German. If I die or if you shoot me, I am still a German. I bring more benefit to the German regime than the accursed Ukrainians who served the Soviet regime and now serve the German regime. When we leave they will go back to serving the Soviets. The only thing they know is how to hit Jews, steal their property, and take it for themselves.”

The Gebietskommissar did not want to kill him even if he was a Jew. The Gestapo people hesitated about what to do with him, and they went back to the town. Dr. Klinger hated the Ukrainians because they served the Germans and helped them massacre the Jews. And thus the struggle between the Ukrainian Police and Dr. Klinger went on. The Germans watched the game from the sidelines.

Edward was a Pole, a policeman during the Soviet time, a policeman during the German time, and a policeman with the Ukrainians. He was from a poor Polish village in the Ukrainian swamps. He was jealous of the Jews because of their high standard of living. He was a sworn anti-Semite and served all the regimes that tortured Jews. It annoyed him that Dr. Klinger watched over the town so that no evil would befall the Jews. It pained him and the entire the Ukrainian regime that everywhere else they were doing whatever they wanted to the Jews, while the Jews here lived peacefully. Nevertheless, he decided to live in peace with Dr. Klinger, and up to now there had been no troubles in the town. No one understood what this meant. They came to his house, drank with him and spent time with him. The drinking binges multiplied. The Jews earned money. The golden calf turned the heads of the Jews, and they did not see what was happening to Dr. Klinger. They urged him to buy gold for himself and to let them, the craftsmen, sell their merchandise on the side.

Things got to the point where they attached gold Russian coins onto Dr. Klinger's coats instead of buttons. Dr. Klinger no longer controlled himself. From so much drinking he did not see what was happening around him, and he did not understand what the Ukrainians were preparing for him. They would invite him to a nearby town, set up drinking parties with women. He did not guard his tongue there in languages they did not understand. They did not murder him because they were afraid of the Germans and not yet certain about his ancestry. And finally, they decided to know the truth. On one of those nights Ukrainian policemen came and invited Dr. Klinger to go with them to a party. There were policemen from the whole area. Klinger got dressed and went with them. When he arrived there, he saw the heads of the murderous Ukrainian Police. He was received with great honor. The tables were set with drinks: vodka, samogon [T.N. moonshine], and all kinds of meat. They drank to the German victory, to the death of the Germans, the “Yids.” When they saw that Klinger was already drunk, they sat a young woman down next to him. She hugged him and at the same time gave him drinks until Klinger did not know what was happening to him. He still believed he could save the Jewish town. He had done and was ready to do everything to save the few thousand Jews of this small far-flung town in the Ukrainian swamps. He thought he would fool the Germans by going out with the Ukrainians and doing everything so the town could stay alive until the Germans retreated. Is there any greater heroism than that? So he must have thought. While they were cruelly slaughtering the entire Jewish people, there could still be found someone who wanted to rescue a few thousand Jews from destruction. No, he would drink without stopping. He would show them he is not a Jew. He will spend time with their shiksa and triumph over all of them.

They dragged him to another room... and in a minute Klinger was standing in the middle of the big room. They were all sitting down, their faces flushed, drunk, gobbling their food, laughing and spewing out wild shouts: “Jew, Yid...”

Klinger tried to close his pants, but he was dizzy. He fell down on the floor, hit his head with his hands, and cried, “Good God!” he bawled. Everything was turning round and round, as if he were traveling through dizziness, and all those wild people were going round about him at a rapidly increasing speed. And then he saw his wife and two children: a six-year-old boy wearing a white shirt and blue pants with a round face and nicely combed hair, and an eight-year-old girl, tall and pretty like her mother. He was turning around with them and held the children close to his heart. He grasped the hands of his wife to help him hold on to the children, because the dizziness was getting worse. When he woke up, he was lying down, covered up with his coat.

Chaim was the only one in the town who told him to flee to Warsaw, but he did not want to. He believed he would triumph over the Ukrainian murderers and save the town. When a shot was heard in town that night, it was no surprise to Chaim because he knew everything.

On my third day in the hospital I was overcome with nervousness. Sashka was no longer there. Marusia said those who had not yet gone to the doctor must go today for a checkup. After breakfast I went to the room where I was told to go. After all the tests they told me my lungs were punctured but were healing. I should rest and eat good food.

All the partisans received clothes from American packages. They said the Joint sent clothes for the Jews, but the regime used them as they pleased. On the fourth day I went to the partisan headquarters. I entered the office where they distributed clothes. When it was my turn the officer said to me:

“What, a Jew also needs clothes?”

“Comrade Officer, why are you sitting in an office? Fighters like you are needed at the front!” He stared at me. He never imagined he would hear words of such chutzpah. He wrote down for me: two pairs of cloth underwear with laces, a pair of shoes, a pair of pants and a coat. Except for the underwear with laces, everything was from the American packages. I also received a few hundred rubles, and the next day I went out to the bazaar. They told me there was a big market here by the name of “Yevryeĭskie Bazaar” (Jewish Market). I decided to see the market and not only because of its name. I went through Khreshchatyk [T.N. the main shopping street of Kiev] and Lenin Street to the Besarabsky Market. On the way there, I was surrounded by people who asked me what I wanted to sell or buy. For some reason I did not like having American products in a socialist country, and I immediately got rid of them. They grabbed them from my hands and gave me any price I asked. Later I found out I really gave them away for nothing. I already had enough money and began to walk in the streets of Kiev. I wandered on the streets for many hours, looking at people, men coming and going from work, women and children, soldiers and officers. For the most part there were wounded soldiers with amputated legs or arms who dragged themselves along with the help of canes.

When I got tired of the hospital breakfast, the preserved American meat every day, I would go out in the street early. The air was chilly but fresh. I walked to a small bazaar and suddenly I saw tables covered with white cloths. On the side there were big pots where potatoes were cooking on the fire. People stood with plates in their hands and ate piping hot potatoes. Their pleasant aroma penetrated my nostrils and I approached the table. When I took a plate and spoon from the table and held it out to the Ukrainian gentile woman, I glanced at her and saw she was healthy and refreshed, her face ruddy. As always, I remembered our Jewish women, exhausted, beaten, helpless, their honor desecrated, who went with their children in their arms to the pits... at that moment I heard from the side: “The Jews did not fight, the Jews are sons of bitches.” I looked around and saw two wounded officers leaning on canes, eating potatoes and spewing fire and brimstone on the Jews. The Jews did not fight, they abandoned the front, profiteering Jews, Jews ran away to Tashkent. Poisonous Hitler-like hate was surging up within them. I froze in place with the first spoon of food in my mouth. The potatoes were hot, fresh, and delicious, but they stuck in my throat when I heard these things.

Again I looked around. I was the only Jew, and they were talking about me. Who are they? Ukrainians and Russians who grew up under the socialist Soviet regime, who wave the flag of equality and freedom, paradise for all, for the workers of all the countries. I wanted to restrain myself but could not. Three years I fought and shed my blood for my freedom, so why should I be silent now? No, dear woman. I glared in their murderous eyes and said: “How are you not ashamed to speak this way? Come with me to the hospital and see how a Jew is lying in every third bed. The biggest medals of honor were given to the Jews!” They did not answer, but the Ukrainian gentile who sold potatoes so freely and thrust the rubles in the deep pocket of her apron cried out, “Clearly they are right. The Yids fled to Tashkent. Now they are coming back with big suitcases and want their apartments returned to them.

I understood that she lives in a Jewish apartment, which she probably has to return and this pains her. “It is a pity they did not kill them all,” she said and took out the newspaper Pravda (truth), tore off a piece of paper, poured tobacco into it, and inhaled the cigarette smoke in enjoyment.

This reminded me of my first day in Kiev. I told Sashka that I wanted to buy a newspaper. It had been three years since I read a paper. He said, “Here, Sankeh, forget the Russian newspapers. You know what they say: there are two papers. The name of one is Pravda (truth) and the other is Izvestia (news). So they say that in Pravda there is no izvestia, and in Isvestia there is no pravda. When I saw what she was doing with the paper, I slowly began to understand the false hopes of the most tortured workers in the world.

In the afternoon I walked on the streets again until I arrived at the railroad station. It was full of soldiers, but there were also farmers and peasants with sacks of food. Two policemen from the NKVD, the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, walked around in the station hall and demanded certificates from the civilian residents. When one of the people did not have the correct document, they would take him to the police. I saw a few people sleeping on the floor. The policemen kicked them with their boots, and those people woke up and presented their papers.

I asked what is going on here, what do they want from these people. They explained that everyone must work, and it is forbidden to travel from city to city without a special paper called Komandirovka (travel order), which is a permit given when people are sent by a factory or the government. They explained that you can receive a paper like that, you just have to figure it out. So I wondered why they needed to lie.

I returned to the hospital. It was dark there. When I came into the entrance hall a surprise was waiting for me. I noticed a young Jew who stood in the corner and talked with three young women. I began to walk towards them immediately but changed my mind and walked towards my room. While walking I could not restrain myself, and I turned my head to see the people standing there. They were also looking at me and our eyes met. They were the first Jews I encountered after my time with the partisans. I felt I had found a treasure, and it was a shame for me to touch it immediately, in case I might lose it. I went into my room and remained standing. What did I do, why didn't I immediately approach them? I had the feeling I might know him, perhaps he is one of our partisans. Where did I see him and who are the young women? Are they Jewish? They did not look like Ukrainians.

The room was big and totally covered by mattresses on the floor, but only six partisans were sleeping in it. Why were the severely wounded lying in the military hospitals on the ground, while here we were living as though in the Garden of Eden? The Russians know how to show partisans respect. Perhaps thanks to the work of the partisans behind the front waging battle with the Germans, the army can advance.

I was lying down in my clothes on the mattress. It seemed like I had already been here a long time. In fact it was only my fourth day here, and I was so bored. Good God, how much I had dreamed of being free, walking around without a rifle, wandering freely in the streets, sleeping to my heart's content. Where are our partisans now? They probably already left the village and are marching in the distant swamps of White Russia or waging battles with the Germans. Perhaps they are lying on one of the rails waiting for a train full of German soldiers to come so they can blow it up? Who knows who will fall at the time of the withdrawal? More than one of them will be wondering about Sankeh being here in the Great Land. Maybe I will go down again. Are they still waiting or have they already gone? The hour is nine, and I did not eat. I have so much money. Why not go to a restaurant? It is interesting to see what a restaurant looks like here. I did not feel it when I took the coat. I ran down the stairs and the young man approached me. “You are a Jew, aren't you?” Yes I am a Jew,” I said. “Even if I do not remember that, they remind me when I come and go. You are a partisan, and I am sure I saw you somewhere.”

“Yes, I am from Podorov's division,” he said.

“And I am from Kovpak's division. We went by once and met you. Afterward we parted a few days later. Have you been here for some time?”

“Yes, I was severely wounded. I was lying in a cast for two months.”

He told me that some of my partisans had also been here but they had already left. There was one of them called Grisha.

“What! Grisha, indeed. We were together with the Jewish partisans. Where did he go? Home? What does it mean home, where there is a dog house?”

“I do not know, but he traveled west.”

“Who are the girls?”

“Those are young Jewish girls from Kiev. They visit me every day at the hospital.”

“Are there Jews here who are alive?”

“A few families remained here and hid, and there are some who have returned from the heart of Russia. Very few Jews. The Germans murdered all the Jews here. The girls tell how their Ukrainian neighbors showed the Germans where Jews lived. Indeed the same Gentiles are everywhere. And what did you think? Here they even surpass the people of the west in their anti-Semitism.?”

“So then, what did Communism bring about

“Do not ask questions. You will still know a lot. What are you doing now?”

“I want to eat.”

“Ask Marusia. She will give you something to eat.”

“No, I want to eat in a restaurant. I have so much money, and I want to get rid of it. My pockets are simply weighing me down.”

“From what I see, you are still confused. You have still not started to live normally.”

“No, not so fast...”

It was the end of April 1944. The snow had already disappeared, and we could feel the spring spirit. On the streets few people were visible, people from the police and the NKVD. The buses were almost entirely without people. I heard people speaking Russian and also Ukrainian. The Russian language was closer to me. When I heard people speaking Ukrainian, I would remember the policemen in the ghettos and the shooting by the pits. That language reeked of pogroms, slaughter, and Jewish blood.

“Tomorrow I will introduce you to the Jewish girls and bring you into a Jewish family. It is very interesting to get to know their way of life. The men are not here. They are either at the front or they were murdered by the Germans.

The restaurant was full of small tables. Four people sat around each table, soldiers or officers. Partisans could be immediately identified by their clothes. Most of them wore medallions and medals of honor on their chests. Very few civilians were seen, and even less women. On the tables were thick glasses of beer, slices of bread, preserved meat or cooked potatoes. Some of them ate soup in plates. When we sat down I noticed that there were very few healthy soldiers. Many of them had canes with them. They drank beer and talked a lot, stories from the front, from the battles.? “You know,” I said to my friend, “we are already together almost an hour but I do not know your name. I am Sankeh.”

“I am Boris. My correct name you will know when we go home. Boris is my name among the partisans.

We ate soup and warmed up a little. Boris brought vodka and small plates with potatoes and a few slices of meat. We filled the glasses halfway up. We raised our glasses: “To the motherland, to Stalin!” And we laughed, because this is how we were used to drinking with the Russians. For the second glass we no longer had any reservations and we made toasts for ourselves: “Death to the Germans and to all the anti-Semites, to meet again in Palestine!” For the third glass we kissed each other and tears flowed from our eyes. Both of us leaned our heads on our hands and it was as though we were talking to ourselves: “Who remains from us? All were slaughtered. Why didn't they all go to the partisans to fight?”

“You know, Boris, I want a little more vodka. How much does it cost? Take all the money. Do you remember how the gentiles would inform on Jews for a bottle of vodka?”

“Yes, I remember. L'chayim! To life!”

“No, not l'chayim. What kind of l'chayim? Do you think we are sitting with the family at the Shabbos table? Revenge, Boris, revenge! Not to life, only revenge!” My head was spinning. Life and revenge.? “You know Boris, those who took revenge are not with us. The best are no longer here. We are alive because we did not take enough revenge, because we wanted to stay alive, and for that we have a debt to those who fell. We are deceiving ourselves that we are doing good for others and showing courage by staying alive. It is only fear and egoism.”

Suddenly noise was heard in the other hall. Someone turned over a table, glasses and bottles fell on the ground, and shouts and curses were heard in Russian. We were sure two drunks were quarreling, but suddenly there was silence. Everyone was sitting in their places. Only one of them, a partisan, stood up, waving two canes, his hair wild, his face flushed with drink, shouting, “I want them to give me back my leg. I do not want all these medals!” He tore off his medals and threw them on the floor. “This is scrap metal. Why did I fight? Why did all those sitting in offices not fight?”

Everyone was sitting seriously, sadly, staring at the partisan. He burst out crying and shouted, “Mama, Klarinka!” and all kinds of other names. It took a long time for him to calm down, and a policeman took him out of the restaurant.

Boris thrust a roll of rubles back in my pockets. “Today, Sankeh, you are with me. You will still have a chance to spend money in Kiev. I am only staying here two weeks,” and he disappeared. He returned in a few minutes with a bottle of vodka. “You know Sankeh, the Russians drink a lot of vodka to forget their sad, gray lives. “ We drank again and ate potatoes and meat, and the more we drank, the closer we became, and we also embellished how we saw what we been through over the last five years: the Germans, the Gestapo, the brown shirts, the gray uniforms, the Germans shouting at the top of their voices and whispering and giving murderous blows during work. Pits, pits, shooting into the pits, covered pits. Silence, no more crying. Forests, forests, endless forests. Partisans, Russians, Ukrainians, Poles. Hatred, attacks, battles, explosions, escapes with our last bit of strength. You need to know how to run away, otherwise you are lost. To wait for a train until it blows up. Who knows these moments, when your hair turns white in a minute...

Boris says: “Tomorrow I will bring you to the 'Gastronome.' There you can get the finest drinks and foods. High-ranking officers come there because the workers cannot afford it. The prices are very high. I will introduce you to the girls. You still need to stay here for some time so you will have people to go out with. What are you thinking about, Sankeh?”

“I am thinking why destiny separated me from my brother Henrik.”

“What do you think? That only you had a brother and a family? All of us had this, and destiny separated us.”

”No, Boris, everyone wanted to live, and everyone struggled to stay alive, but Henrik did not struggle to stay alive. He lived to take revenge. When all the Jews were sleeping quietly in that small town, dealing with bargaining and commerce to make money, they deluded themselves that money would save them. Henrik did not sleep... he did not sleep at night. 'Children,' he would say, 'you must not sleep. The Germans are tricking you. They are preparing pits for us while we sleep. They are murdering Jews in all the towns. We must not sit and wait for death. We have to get weapons and go to the forest.' They made fun of him. They would say, 'We are working for the Germans and they need our work, so they will let us live.' Others said, 'What can be done against such a German power? Whatever happens to all the Jews, will also happen to us. With the help of God we will wear them out.' “

Boris remained silent and I went on, “A comfortable life and attachment to the family brought about the annihilation of the people. The Jews did not understand how someone could sleep under the open skies, live in the forest, live without money or other valuable things. Henrik understood that, even though he had not been brought up that way. He saw the Jews slaughtered like sheep without returning even one shot. After that night when he argued that we must not sleep, he got up in the morning and disappeared for a few days. When they asked him at home where he was going, he did not say anything. He would come back tired, dirty. He would wash up, change his clothes, taste something, fiddle with something up in the attic, and disappear again. We were working then for the Germans, and they would often come to our house, sit around, and drink vodka and honey. Papa would ask them if something was going to happen in the town. The good, tall “Yekke” [TN: stereotypical nickname for a German Jew] would wipe his mouth after eating and say, 'No, no harm will come here.' And Papa would relax and say that with the help of God we would wear them out. The Germans would notice that Henrik was not at work, but they did not ask about that, and we did not understand why they did not ask. But they were already preparing the massacre, and that is why they were no longer interested in 'the work of the Jews.' ”

Henrik's activity aroused pride and suspicions within me. I snuck up once to the attic and saw an entire workshop there. There were pistols, complete and taken apart, and a person was sitting there deep in his work, filing, polishing, cleaning, assembling. When I entered he was not startled because he was working legally. I saw the man for the first time. I closed the opening again and went down from the attic. The next day Henrik came to me and asked me to prepare a leather belt for him. I did not ask anything. I understood what he meant. In the meantime, Henrik had more foresight than all the others, so he wandered entire nights in the villages, knocking at the houses of gentiles he knew and looking for a person to sell him a used pistol, any old weapons, even rusty ones incapable of shooting but that would look like weapons. It could also be a sawed-off shotgun. In exchange, he paid in gold, dollars, leather, fabrics and watches. All the peasants had weapons. When the Soviets withdrew, many Russian soldiers threw away their weapons, exchanged their uniforms for civilian clothes, and the Ukrainian and Polish peasants took advantage of the situation and hid the weapons. They buried them in the cow sheds. It was not easy to persuade the peasants to sell weapons, and if one of them sold something, it would be a defective weapon for which the peasant was asking gold, leather and other valuable objects.

Henrik already belonged to a small organized group then, but he did not talk. His silence revealed and told us more than his words. I sensed his looks and understood his thoughts. He saw the game was coming to an end, the days were numbered. Why didn't we go with the Russians when they withdrew? Why were we not now in the safest place in the forest? Why were we silent and waiting to die? Why were we going like sheep to the slaughter?

I remember the evening when our sister Chava prepared supper but the food stuck in our throats. That day something happened. One of the people of the Ukrainian Police was at our place and he said to Papa that in the next few days all the Jews would be murdered and also the women and the children. In our house we believed this might happen. Papa said God could help at the last minute. My sister Chava was as silent as a dove, quiet and doing her work. She prepared food for everyone and worked devotedly. Poor Chava ran the household after Mama's death. Chaim bit his lips and stared at all of us with his watery white eyes that expressed revenge. If he could have, he would have carried out, “Let me die with the Philistines.” [TN: Judges 16:30: Samson said, “Let me die with the Philistines!” Then he pushed with all his might, and down came the temple on the rulers and all the people in it. Thus he killed many more when he died than while he lived.] I was quiet, I saw the tragic day coming, but I asked for help with Papa's hope on the one hand, and I waited for Henrik's actions on the other.

It was tragic to meet Heniek's looks, my brother-in-law's brother, a teacher in Warsaw, who was staying with us at that time. In his quiet glances and silent face I saw the whole Jewish tragedy. He would talk to himself in a whisper: “Why didn't I escape with the Russians. Why did I stay here?”

“Boris,” I called suddenly, “Have you ever seen living dead people? I saw living dead. They walk around freely, breathe, eat, drink, sleep, and nevertheless they are dead.

“Sankeh, I know the whole story. I, too, was lying here during the first days in the hospital and lived anew the whole tragedy in my bed. You come now from the forest and see a city full of people living freely, and that awakes the tragedy within you all over again. Fate wanted you to stay alive, and that means you and I are the continuation of our families who were murdered and also the continuation of the Jewish people. The restaurant where we are now is a chapter in the tragedy that the German murderers wrought. Everyone is sitting here and drinking to drive the tragedy away with the help of alcohol. “Boris filled the glasses again. “Sankeh, let us drink to staying alive.” We turned the glasses over and emptied them.

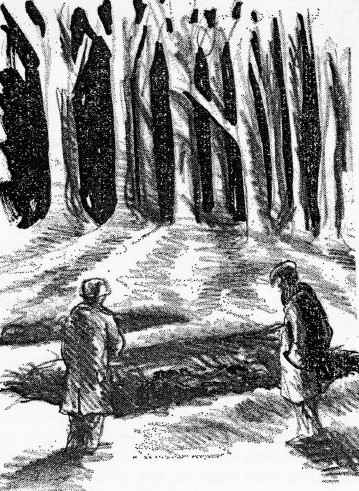

“Boris, did you ever see pits? My head was spinning around a bit from the alcohol. I did not see the restaurant, the tables, the soldiers, the partisans. I saw two big pits. “Sometimes they dig pits to build houses or for other reasons. Workers dig pits and sing while working. But I saw other pits. Two big pits, five meters wide, ten meters long, and three meters deep.”

“They drank rum, German rum. There were two German Gestapo officers and the third one was an engineer. Do you see my hand? These hands dug pits. I must tell you that the first two pits were made according to a plan. A German engineer with a measuring stick in his hand stood there and calmly measured, as though he was carrying out a plan to build a house. With him were two Gestapo people holding pistols. After he measured the exact length and width, he marked straight lines with astounding precision. We were sixty Jews surrounded by Ukrainian and Lithuanian police. They were armed with rifles. The Jews were divided into two groups. Thirty Jews dug one pit, and around each group the policemen stood with their rifles like a wall. Whoever did not work quickly enough and wanted to rest a little was hit by the rifle butt accompanied by a shout: 'Work quickly, otherwise you will be first in the pit.' The sun was sinking, we were standing on an island of a pine forest. The air was fresh.

The digging was carried out with no difficulty, the earth was sandy. Sometimes it was impossible to imagine that we were digging pits for our sisters, our brothers, our children. It was impossible to believe that this was reality.

I stole a glance at my father. He was pale. His beard was thinner than ever. His black eyes, full of fear, looked at the sky. Every time he raised the shovel with dirt, he looked for God, the God of the Jews who created the world and human beings, who helped him in times of sorrow, in whom he believed so much that He could come to help at the last minute. I looked at my father and I remembered how he would run every morning to the Beit Midrash with the tallit and the tefillin in the winter, in the fiercest cold and the strongest winds. And now he was asking Him, he was putting Him to the test. When I saw my father's cry for help, something in me broke and I swore in my heart: 'Good God, if I stay alive, I will take vengeance on the murderers.'

After a few hours two pits were ready, two light-colored sandy pits. The earth was disquieting. It gave them a fresh smell mixed with the smell of the forest and the singing of the birds. Now the pits were waiting for the victims. We were set up in groups of four and we marched, strongly surrounded, in another direction towards the nearby town, so we could not tell anyone what we had prepared. On the way back I marched alongside my brother Henrik and another young man, and we wove fantasies, what we would do now if we had rifles in our hands. We decided not to go to our deaths, but to get weapons and take revenge.”

Boris sat, his head leaning on his arms and both of us looked in each other's eyes. Perhaps he was not listening, and perhaps he listened and saw what I had gone through in the same mirror.

Suddenly he asked, “Sankeh, why don't you say something about the partisans. Did you at least take revenge?”

“I think we did not fight as Jews against the Germans when were in the movement of the Russian partisans. We helped the Russians drive out the conqueror from the land of Russia, to liberate the Russians, the Ukrainians and the Polish people. The Germans did not conquer our country, we have no country and no land. The Germans destroyed all of us, even our children and our mothers. That does not mean that we avenged those who were screaming before going into the pit: “Avenge, avenge!”

“No, Sankeh, also the fact that we lay down face to face across from the Germans and shot at them, blew up their trains, and that we are sitting here now in a restaurant as free people and can remember all of this, even this is big revenge, that Hitler did not succeed in destroying the entire Jewish people. Tomorrow I am going to the partisan headquarters where I will receive money. If you want, you can go with me, we may meet partisans we know there.

“Alright, I will go with you. It is sad to stay alone in the hospital.”

On the way back to the hospital we amused ourselves by imagining who from our families we might meet when we would be liberated and return to our former homes. But do we even have a home at all?”

“You know, Boris, I swore in the partisan movement I would stay with the first Jewish girl I would meet, if there is still any Jewish girl left in the world.” He smiled and looked at me out of the corner of his eye, as though he was thinking the same thing.

|

|

On the fourth night in the hospital I dropped onto the mattress in my clothes and fell asleep covered up over my head. This was the first time I fell into a deep sleep.

Towards morning I woke up in a cold sweat. I dreamt terrible dreams. I saw once again the Jews of the town going with their bundles to the town square. They are carrying suitcases and big packages on their shoulders. Here goes an old, sick woman, alone with a big pillow under her arm and a bundle wrapped in a sheet on her back. She is pushed from every side and falls. A German pounces on her, pulls out his pistol and shoots her. Her blood flows on the road, the feathers are flying about in every direction, the noise grows louder, the Ukrainian Police push the people with their rifle butts. The people throw away their packages so it will be easier for them to run to the square. I see a young woman running into one of the houses. She probably wants to hide. A Jewish policeman chases her and drags her out by force. I cannot stop myself, and I pounce on him shouting, “What do you want from her. Let her save her life. How are you not ashamed? You are a Jew. Remember, you will pay for this dearly!”

“I am responsible that no Jew remains at home in this neighborhood,” he tells me, and drags her to the square.

We already knew they would divide the population into two parts. Those who work for the Germans will move to another town, and those who do not will remain. This is a sign they will be killed first. At the same time, all the young women join the young men. When the young woman sees I am arguing with the policeman because of her, she asks, “Perhaps I can be your wife? I so want to live. Help me.” Next to me is my father, my brother, my sister, and now she joined our family. The Jewish police did not believe they would shoot people and throw them into the pits. They believed what the Germans said, they are taking them to work. The “Judenrat,” which headed the Jewish community, was convinced that everyone was going to work and so it gave assistance to the Germans. Its people went first. A few thousand Jews stood a few hours on foot. Not one Jew remained at home. Those who remained were shot to death by the Ukrainian Police which went from house to house and searched, blowing up walls, opening cellars, shooting or dragging people to the town square. The sick and elderly were shot in their beds.

We stood from eight in the morning until two in the afternoon, men, women, and children. They are surrounded by policemen and Germans who were brought especially for this purpose. Suddenly I saw the Ukrainian Savchenko. He is marching arm in arm with Rachel. His face is red, he is well dressed, self-confident, in his Jewish clothes. She is white as chalk, exhausted, downcast. He is leading her by force. She is walking indifferently. She does not care where she is going. He crosses the wall of Germans and Ukrainian murderers with her, arrives at the first row of Jews, pushes her into them, turns back, puts his hands in the pockets of the leather jacket and disappears with strong steps. The sacrifice stood silent, as though it did not care whether it was going, standing, sitting or lying down.

I saw all of that, the struggle between the young Jewish woman and the Ukrainian, as though it were a dream. I saw Rachel's opposition, how he tortures her, urges her to stay alive. He will save her, if she only devotes herself to him. She did not want him and she did not want to live. But he, the Ukrainian, wanted to take everything from her. He wanted to desecrate her honor and then turn her over to the murderers.

I knew Rachel during the time of the Soviet regime. They were two sisters and a mother, who made a living from a small grocery store. Rachel was the younger sister, an upright and pretty girl, with smooth black hair that curled up at the ends. She had a lively white face and a short upturned nose. When she smiled, there would be dimples in her soft cheeks. Her chin also turned up a bit. She always smiled. She had quick and pretty legs. She always wore shoes with high heels. In the afternoon hours in the summer when the young people took walks, she wore a black jumper made of alpaca and a white blouse that gave her grace and glory.

The tragedy began when the Germans began to take people away to work. During the time of the Soviets, Savchenko was in the “Comsommol,” a Communist youth group. He was also a teacher and a good Communist. When the Soviets withdrew, Savchenko did not flee together with the party. He stayed with the Germans and immediately became a leader among the Ukrainian nationalists. He was appointed manager of the local dairy that produced butter and cheese for the Germans. The Jews were forbidden to leave the town. The food situation grew increasingly worse. They confiscated everything from the Jews: their cows, goats, and roosters. Farmers stopped coming, and the Jews would sneak into the village, exchange clothes for food, risking death or beatings by Ukrainians or Poles. In the dairy, the water that flowed from the cheese and other dairy products was left over. Jews would go there and ask for a little of that water to cook with flour.

Among all the girls who went there to buy was also Rachel. Every time she would enter, Savchenko would gaze at her and swallow her up with his eyes. Sometimes he would give her an excessive amount and refuse to take money. She did not want this, but the hunger at home was fierce and in the end she accepted it. One day he invited her to his office, talked with her softly, told her he hates the Germans, loves the Jews, and wants to help her. The eighteen-year-old girl saw him as an angel from heaven and stayed with him after work. The situation became more and more serious. There was already talk that they would kill all the Jews. Savchenko would tell her, “Rochele, you are Jewish, but I love you. I am a Communist. Stay with me because in a few days they will murder all the Jews in town. You will stay alive, and you will marry me.”

“No, Savchenko, I want to go with my mother, with my sister, with all the Jews. Wherever they go, I will go too. I do not want to stay by myself.”

He hugged her, held her close to him. She wanted to escape from him, but he held her by force, kissed her, bit her. His hair was wild. “Such a foolish girl you are. Why are you afraid? I want to save you. I love you.” Rochele escaped from his embrace and ran to her house. It was already dark. They were not allowed to walk in the street, but she went home to her mother without any watery leftovers. Her mother understood something had happened to the girl. She caressed her smooth beautiful black hair gently and cried. Their tears intermixed. “My daughter, this is our luck; this is the Jewish destiny.”

The next day Savchenko came to Rachel's house and said that tonight the town would be surrounded and all the Jews would be murdered, but Rachel did not want to hear what he was saying. He began to threaten that if she did not go with him, he would hand her over to the Germans. He turned to her mother: “I want to save your daughter. I love her. Tomorrow they will shoot you to death. They are already preparing pits for the whole town. I know everything. Tell her to go with me and she will stay alive.”

Her sister heard everything. She sat on the bed, pale, her hair uncombed and wild. Suddenly she got up and shouted, “No, Savchenko, my sister is Jewish, like me, daughter of my mother, and she is going with us. What happens to us will also happen to her and to all the Jews!” Savchenko spat. “Lousy Jews!” He slammed the door and went out. It was already noon. The mother cooked a few unpeeled potatoes and the two girls ate. “Girls, our days are numbered,” the mother said. She wound an old scarf on her head and took the prayer book into her hand to recite Psalms. “If your father were alive, perhaps we would have been able to save ourselves, like other families who are hiding with Gentiles or go out to the forest.” Suddenly the prayer book slid out of her hand. She went to Rachel and said, “Rochele my daughter, perhaps it has been decreed that you will live. Perhaps God wants to give you your life as a gift, so that at least there will remain some trace of the family. Go to Savchenko. He will save you. You will stay alive. After the hell, you will be able to go to Palestine where we have family. “No,” her sister cried and wept. But she did notice that her mother took the coat and took out a dress and underwear from the wardrobe, put all that in an old bag that the children used to use for schoolbooks and notebooks, and handed it all to Rachel. Tears flowed like bountiful rain from the eyes of the mother and daughter. Rachel held her sister and mother close to her heart and then went out of the house. Before she opened the door, she turned back to look at the room where she grew up. A young woman eighteen years old, beautiful, upright, refined, and now her mother is sending her to Savchenko, the Ukrainian murderer, so she can travel to Palestine so some trace of the family will remain.

Savchenko was not yet in his office that afternoon. He was busy. He was one of the Ukrainian nationalist activists. He did not wear a uniform, not during the Soviet time and not even during the time of the Germans. He knew the regime might change, and he did all the despicable jobs in civilian clothes. No one knew anything about his work. That afternoon he had to participate in a meeting with the German gendarmes and the officers of the Ukrainian police. Savchenko ate his lunch quickly: vodka, potatoes with borscht, and a piece of pork that Katya prepared for him. He polished his boots, put on his riding pants, and his leather coat, while he sang a Ukrainian song from the Soviet times, softly. He lived alone in a room with Riva who cooked for him and washed his underwear.

Katya asked him, “Savchenko sir, what holiday is today, why are you in such an excellent mood?

“My dove,” he said to her “because we won. Tomorrow we will be rid of all the Yids. You can take for yourself everything you want- the best boots, dresses, coats, and a house full of furniture.”

“Oh, Savchenko, I will take Motke's house. They are rich. Are you promising me?”

“Yes, I will give you everything, but now let me go.” He gave her a light pinch and went. He said in his heart, “If only Rachel the little Jewess were mine now. She is so pretty and refined, while Katya is fat and dirty.” He went out whistling to himself.

The Germans' table was long with big bottles of vodka. The air was stuffy from cigar smoke and the smell of alcohol. German hats were arranged in a row on the buffet. One hat belonged to the head of the staff, and another to the area officer of the Gestapo. Both of them came especially to direct the extermination campaign. The third hat belonged to the gendarme Kaiser, and the fourth to the gendarme Gruber, the local gendarmes. In the middle was a big table with six chairs. The chairs were upholstered in green velvet. The table was dark brown with carved edges.

At the head of the table sat the head of the staff in a brown uniform. He was tall and upright. His face was serious without a smile. Across from him sat the commander of the Gestapo, a thickset man, who had a wrinkled face with a deep scar on the left side. He wore a blue uniform. He looked like a murderer who had just now come out of prison.

To the right of the head of the staff the two gendarmes sat, Kaiser with the serious face and the elderly Gruber, who was over the age of fifty and was bald. He was drunk and sad. In a little while, it would be a year that he had been living here with the Jews, receiving a lot of money and gifts, and now all this was coming to an absolute end. For some reason he does not understand the policy of the “Fuhrer.” Across from them the two Ukrainian officers sat, one with the name Friedrich, who was a policeman during the time of the Poles, a person of the N.K.V.D during the time of the Soviets, and a police officer during the time of the Germans. He said his father was a Pole, his mother a Ukrainian, but his grandfather was from German ancestry, that is he is Volksdeutsche and is entitled to serve every regime. He knew all the Jews, he knew about their children's children and their connections. He knew who was poor and who was rich, and he knew who to extort with demands, who to take away to work, and who to leave alone. Next to him sat Panchenko, a typical Ukrainian, wearing a Cossack hat and a green uniform. This is how he assumed the Ukrainian army would look when the Jews were exterminated and the Germans gave the country to the Ukrainian nationalists. Thirst for blood was revealed in his eyes. He was restless and kept touching his pistol where it pressed against him while he sat there on the Jewish velvet chair. He hates the Soviets, the Jews, and the Germans too, but the Germans are his friends and help him liberate the country from the Communists and the Yids. He was annoyed that he did not understand German and he had to ask the dirty Pole to explain what the Germans were saying to him. When Ukraine would be liberated, he would also exterminate that Friedrich, because he was half-Polish, but now he is beneficial to him. For some reason he knows all the languages, he even knows Yiddish. A few days before the extermination this Friedrich passed in front of a Jewish house and saw children destroying the fence to gather wood for the stove, and he said, “No, children, you are not allowed to do that. You will need it in the winter so snow does not get in.” When the Jews heard this, they believed they would still be alive in the winter.

When Savchenko opened the door, he immediately saw the four hats on the Jewish buffet. All the way there, he thought about Rachel, and he could not get her out of his mind. Tomorrow they would shoot her to death, and he wants her at any price. That little Jewess, he cannot live without her. He wants to make a plan tonight, how to take her out of the house. He was so deep in thought, he almost said “Zdravstvujte” (Hello in Russian), the Soviet greeting, but when he saw the hats, he came back to reality. On the wall hung a portrait of Hitler, which reminded him to say “Heil Hitler. At that moment, he heard the head of staff ask Friedrich if the swine already found a place to prepare the pits. He meant the Ukrainian police. Panchenko did not understand who he meant, but Savchenko got it immediately, and that annoyed him. The thought went through his mind that the Soviets would still come and see who the real swine were. The Ukrainians had a mix of hatred, loathing, and a desire for revenge against the Soviets, the Jews, and the Germans, too.

Panchenko said that tomorrow at 2:00, two big pits would be ready. They would be sufficient for all the Jews in the town. Now the head of the staff read the entire agenda from a paper:

“Tonight five hundred Ukrainian and Lithuanian policemen will come and surround the town from all sides. Panchenko is responsible that not even one Jew escapes, otherwise they will shoot the swine. They will surround the Jews while they sleep at night, unaware of it. Tomorrow at 7:00 in the morning, the 'Judenrat' must call all the Jews to the town square to receive work cards. When they are all in the square, people with professions, those who work for the Germans, will be separated and led to another town. Then the town will be under closure. No one can go out and no one can come in. From among those with professions, the swine will take sixty Jews to dig pits. This must not become known in the town. After the pits are prepared, all those with professions will be brought home, and all the other Jews will remain in the square for the entire night, without food, without sleep. They need to grow tired so they cannot show any opposition.” (Savchenko envisioned Rochele sitting all night, her eyes weepy. She is so pretty, beautiful, and I did not get her.) “The day after tomorrow at 6:00 in the morning, the Gestapo will arrive with transport vehicles to take the Jews from the square to the pit. Hans, the Gestapo commander, is responsible for that. Hans raised his hand: 'Heil, heil, this will be OK.' The swine are forbidden to rob. Everything belongs to the German regime. Whatever remains later, the swine can take. Yes, the Jews must take off their clothes themselves and go into the pit naked.”

The Gestapo commander rose to his feet and said, “This will be carried out one hundred percent on behalf of the Fuhrer.” Then Friedrich and the lieutenants and the Ukrainian swine stood up. “Now you can drink and gobble up your food, and the swine must bring women.” “Yes,” said Friedrich. “You will receive this, you are my guests. I will take care of it!”

When Savchenko approached his house, the light was already dim. When he approached the garden and wanted to open the latch, he heard a voice: “Savchenko, Savchenko, Savchenko.” He immediately understood this was Rachel, but where did her voice come from? Was this an illusion? No! This was not an illusion. Here Rachel is approaching. She is walking close to the fence, like a shadow. Savchenko is a little perplexed, but he understands. Rachel is coming to save herself at his house. The little Jewess wants to live and so she is coming to him. He stands cold-hearted and waits. She is approaching. “Mother,” she whispered, “sent me to you. She wants me to stay alive, and so I came.”

“Yes, I see that you came, because you want to live, Rochke,” he shouted. “If I did not love you, I would throw you now to the dogs.” (And in his heart, he thought, if I did not want to possess you.) And perhaps he did love her, despite everything, for indeed otherwise he would not think about her so much. He grabbed her arm. “Come, Rochke.” He put her into a small room. “Listen, Rochke, if I keep you at home, Katya will talk about it, and then the Germans will kill me together with the Jews. Sit here. In a little while I will bring food and straw.”

Rochele groped in the darkness and found a place to sit. She was terribly cold. She shivered from chills of cold and fear. She cried, “Mama, why did you send me? I want to die together with you and my sister. Mama, I am cold. Mama, save me.” She arose from her place, groped her way to the door, opened it slowly and wanted to go back home. At that moment she was pushed back by a sheaf of straw, and she fell on the dirty ground. She did not shout. Savchenko understood that she wanted to flee. “Foolish girl, why do you want to run away? Sleep here, no one will cause you any harm.” He lit a light and offered her the straw, and spread a country sheet over it. “Why are you crying, Rochke? Lie down and rest. You are tired. In a little while I will bring you food.”

Rochele lay down on the straw he offered. She covered herself up with the coat her mother had given her. But Savchenko did not let her rest. He brought piping hot milk and potatoes. Rachel ate and thought, if only she could bring warm milk and potatoes to her mother and sister now. And perhaps she could bring her mother and sister to Savchenko, and all three of them would stay alive Why, he was a good man, he is treating her as a father would. Perhaps God would help Mama and she too would be entitled to go to Palestine, as she wanted. Thus Rachel warmed up on her bed in the small dark room on the pile of straw and quickly fell asleep.

At the same time, Savchenko sat at home and looked at Katya through the tobacco smoke while she washed the supper dishes. Who knows if she understood something when she took a cup of milk and slice of bread out of the house without any explanation? He looked at her red nose and thick lips. Why were the Yid girls so pretty and refined? Perhaps that is why they kill them, from jealously, because they are pretty and educated? Our people are boorish peasants and do not understand what is going on in the world. That is why they let them live. Everyone exploits them, the Russians, the Yids. They take money from them for nothing, and now the Germans are exploiting them. We help them wipe out the Jews, later we will work for them, and they will be the master race.

He arose from his place, took a bottle of vodka and two glasses from the cupboard, and put them on the table. He threw his cigarette on the floor and ground it out with his foot. He poured vodka into the glasses half full. “Katya, come here.”

Katya sat down next to him, wiped her hand on her apron. “Why are you so cheerful Savchenko?”

“Tomorrow we will kill all the Jews.”

“Also the Jewish women?” Katya asked.

He blushed a little. “Yes, Katya, the Jewish women too. Even their children.”

“And your Jews, too, Savchenko?...”

“Katya, let us drink and do not ask. I am a Ukrainian and will never betray the Ukrainian people.” The two of them emptied their glasses.

Katya again poured the glasses half full. “Savchenko, come let us drink. To the death of the Yids, and the Russians, and even the Germans, and also to your Jewish woman.”

He did not answer. When they finished the bottle, Katya pulled him to the bed. His head was going around. Germans with their hats on the buffet, Hitler's picture on the wall, Rachel's house with her mother and sister. Savchenko woke up towards morning. He heard the noise of cars. He got out of bed. It was 5:00 in the morning. “Katya is not there. Why did she get him drunk, the fat pig, and take him to bed? I will murder her. Now she is already running to steal from the Jews. She has no time to wait until they are exterminated.”

Through the window, he sees many cars full of policemen and Germans. “Good God, what will I do with Rochke?” He got dressed quickly, lit a lamp, and went to the small room. He opened the door quietly. Rochele was sitting up. She heard the noise of the cars and understood that this was the end of the town. She intended to run to her mother. When she saw that someone was walking, she covered herself up quickly and pretended to be asleep.

Savchenko put the light aside and approached the pile of straw where Rachel was lying covered by a coat, as though she was sleeping and did not feel anything. However, inside she was shaking like a fish that had just been pulled out of the water. Savchenko began to remove the coat and looked at her beautiful, bright, pure face. He caressed her black hair. “Rochke, get up, come home with me.” He began to bring his face close to hers. She felt the smell of alcohol and wanted to get up, but he fell on her with all his strength and began to kiss her lips. She struggled with him, kicked her legs, caught his head with her soft arms and pushed him off her with her last ounce of strength. She managed to get up. She looked for her bundle and wanted to get up, but he lunged for the door and pretended he did not mean to harm her. “Rochke, you have gone out of your mind. I do not want to cause you any harm. I just love you. I would like to save you. You heard the cars moving. Today not even one Jew will remain in the town.”

“Why did you come now to the little room, Savchenko? You can sleep in the house and I can sleep here.”

“I want to take you home, so you will warm up a little. Katya has gone.

“No, I do not want to be in the house. Leave me here. Otherwise I will go to Mama.”

“No, you cannot stay here in the little room now because they will see you. No one will come to my house.”

Rochele was afraid to go to his house. Savchenko was getting impatient. He was holding her by force and pushed her down to the straw. Another struggle began. “Yes, I am going with you,” shouted Rachel. “I am going. Leave me alone.”

Savchenko felt that every time he touched it drove him crazy. He could no longer restrain himself. Again he looked at her, compared her with the fat Katya. He gently caressed her hair, took her arm and brought her to the door. He put out the light and brought her to his house. She was shaking from fear and cold. Her knees were trembling. He felt she was weak and said to himself, “Now Rochke will be mine, especially if fat Katya does not come.” When they entered the house, she felt the odor of vodka and tobacco. She sat near the oven and stared at the window. Dawn had already broken. Savchenko studied her glances. He felt he had lost the battle. Dawn was rising and he could not keep the little Jewess for long. He locked the door, threw off his coat, and approached Rochke. He hugged her, kissed her, and began to tear her vest off. She pushed him off again. “Let me go to my mother!”

“No, I will save you so you can stay alive.”

“I do not want to live. Let me go!” He tore her vest off. She stayed in her panties. He saw her white soft arms and bare neck.

“Rochke, go to sleep, I will not do anything to you.”

“No, I will not sleep here. I am going to Mama.” She grabbed her coat. He grabbed the coat from her hands and tore off her skirt. She felt weak and collapsed. He again caressed her hair and begged her to go to the bed. He was covered with sweat. His face was red. He was longing for her delicate enchanting body. He wants to save her. He wants her to be his. His strength waned, and she struggled with him. He drags her to the bed. Dawn already rose. He no longer controls himself and does not know what is happening to him. He lies on her and pushes against her with all his strength. She pulls his hair and kicks. “Savchenko, let me rest. I will stay with you as long as you want. Mama, mama, save me! I want to die together with you!”

At that moment, a knock on the door was heard. Savchenko jumped up from the bed, went to the living room and saw Katya dragging two big sacks and a suitcase. She saw the door was locked and walked with the bundles to the small room. Rochele got off the bed, grabbed her coat, and ran to the door. But she could not move the heavy bolt from the door. Savchenko saw he lost the battle, put on his hat and leather jacket, and opened the door.

Her mother and sister stood in line with all the Jews ready to go to the unknown.

They were sure Rochele had saved herself and would get to Palestine. When they saw Savchenko put Rochele into the line, her mother thought, “No trace of the family will remain.”

“Yes, Mama, I am here, and I will go together with you. I came back, the same Rochele I was...” and again they all cried together: “That is our fate, my child...”

I saw all this. At night, half asleep, I relived Rochele's tragedy.

The fifth day at the hospital.

I woke up late. When I opened my eyes I did not know exactly where I was.

The square full of Jews and the dream about Rachel were going around in my head, but the noise in the room reminded me where I was. I looked at the new faces that filled the room. Suddenly I felt a kick. “Sankeh? What? Are you alive? How are you? Have you already recovered?”

I saw a new group of partisans. Apparently, they came in the middle of the night.

Here was Mietek standing before me. We found him once in the forest with his sister. He participated in a battle, was wounded, and was now in the hospital in Kiev. He sat down next to me and told me about the recent battles with the Germans. There were many slain and wounded. I asked about friends from my group.

He was wounded in the leg and asked me about my lungs. Marusia approached us and smiled at the partisans. “Now,” she called, “go to wash up and eat breakfast!” Mietek told me: “I think Marusia is Jewish.”

This is what we want to believe. Whenever we see a young, charming, serious girl, we immediately think she is Jewish. “So,” I say, “ask her.”

“As for me,” he says, “she can also be Ukrainian. It is enough for me that she looks Jewish.”

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Through Forests and Pathways

Through Forests and Pathways

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Oct 2013 by LA