[Page 2]

Chapter 1

Forward

When Bene Károly, the President of the Organization of the Beautification

of Dunaújváros, requested to compile about this subject, I didn't know

what I was getting into perhaps I had bitten off more then I could

chew.

How did we survive the Second WW? Those of Pentele that where

in prison, a picture album of Pentele: to compile the first 3 volumes was

just a question of time and patience: there were a lot of sources. But

on this (the Jewish Community) I had almost nothing. There were no residents

that survived, in the place of the synagogue (opposite Szórád school) stands

the house of Perjési.

But the village's past cannot be pictured accurately without them. They

lived amoung us, mostly merchantsorartisans.

First I took some volumes from the library, then I got the key to the

cemetery from members of the town beautification organization, and lots

of pictures of the monuments. (Those were taken by Hajdu György).

P. Fekete István helped with his advise and pictures of the Synagogue

on Dohány St. in Budapest. Czékliné (Manci) my older cousin gave me family

pictures that were taken at the end of the 30's.

Dr. Kucserka Vilma, my former classmate Tóth Józsefné, and Markovics

Ili, who visited the Holyland, all lent me their own books and pictures.

I thank them.The most difficult part is getting from 0 to 1. The rest

is easier.

This undertaking is a subjective history and a documentation of the

era, their past lives with us together. Can we ignore them?

Those who resided or grew up here have better knowledge of the history

of the place and on what the town was built. My intention had been that

when we go and read(in the big Cemetery) the names of those that were deported

we should not see only the letters, but the human lives behind them: feeling,

working, loving families, the names of honest Hungarian Jews. We,

the residents of Pentele, have known and honored them well,

but for those who have just recently come these are only names……

To this day I miss not knowing anyone from the list of names on the

monument that commerates WWI (done by Bory Jenő in 1926) that stands before

Szórád School. I was born after the war, but if there had been someone

who could have written biographies about them, at least we would have had

some memory of them.

My aim was not to be totally complete, that couldn't be possible. I

have no scientific pretense, that is the job of the historians. In my modest

way I tried to remember those that had lived among us for generations.

[Page 4]

Chapter 2

Horváth Katalin (Garbacz Istvánné)

At the end of the forty's I was working as a room maid at the Frankl's

mansion. The 12 built rooms were kept clean by two maids. The

owner's title was honorable sir, his name Frankl Zsigmond. They owed

1,200 cadastral acres (1 cadastral acre=1.4 English acres) near Nagyvenyim

, it was named Szedres Estate. They supplied work for approxiamately 30

families , themaids took care of the animals ( horses,cows, and pigs etc……..).

A gardener, an estate administrator, a carriege driver,dressed

in fine style ( he drove the owner in a fine elegant 2 wheeled carriege),

a cartwright and a black smith alsoworked.His son László and wife Szávics

Margit lived in the mansion. They were childless.

To go back to the parents: there was a cook, a butler that also served.

We honored them very much. As was the custom of thetime we kissed the hand

of the honorable lady ( Sarolta ) every morning.

We loved them truthfully because they treated their servants fairly

( with humanity, for example when the holidays were

approaching , we always received gifts).

There were very few places that one could encounter what we had there:

if we finished our work before noon we were allowed to dress up and spend

the rest of day as we wished. ( Hardly ever did we get any other

chores).

The mansion was built near the Hundred Foot Bridge on the hill opposite

the house of Molnár János from Pentele. A one storybuilding fenced together

with a yard and park. The building was a long yellow rectangle. ( Today

there is no hill and no building).

The rooms:bedroom , salon, dining room , office ( this was a study ),

library,guest rooms; pantry, kitchen, bathroom and a

staircase that led to the cellar. Here I used to clean the mud off

László' shoes , he would wear clean slippers to enter his

parents rooms.

The cellar was huge, built with brick arches, were the wine was kept

in barrels.

From here one could go to the large laundry room where a hired

laundress would do her heavy work. From time to time we also helped: putting

the dish towels on the side of the wooden tub and scubbing them with a

hard brush in luke-warm water. Going out from there we arrived at the house

of the carriege-driver.

The floors were small wooden parquet. We polished them with wax brushes

that we put on our feet.

The salon, where the guests were received , was my favorite: red

velvet upholstery on the furniture. The walls had a patterned wallpaper,

on the walls were paintings, on the floor a huge Persian rug.

In the dining room there was a grand buffet filled with valuable porcelain:

sets of dishes. In the middle was a enormous table. The wood parquet was

allways shining.

From the dining room you could reach the bedroom. The rooms connected

from one another. Along the rooms there was a corridor.

In the spring of 1944 the Germans took occupation of most of the house

and the dining room. The owners would peep from the bedroom to watch the

soldiers recreation. When the soldiers became aware of this they put the

buffet up against the door.It was so heavy that it cut through the beautiful

parquet floor.

My parents began to worry and approximately after 1 ˝ yrs of service

told me to return home.

When I told this to the family of Frankl Zsigmond I could see how it

distressed them.

One day the honorable sir called me to his room.

- Kati, I extremely beg of you. Don't leave us here , your fathers works

for us, we love you all.

-I am sorry, I can't do it.- I answered with a hurting heart - I would

like to stay longer very much, but fate has intervened.

I saw their distress and this made me very sad.

Soon after this they gathered the Jews: packed them, 56 persons, into

Brucks' mill ,on the present Baracsi St..

Their son Laszló survived. He was rescued by Horváth László from Pentele.

We met , unexpectedly , after a long time at the bus station in 1950.

I recognized him. He was surprised and very glad. We talked a bit. I was

very glad that at least he was still alive. I was very sorry for his parents.

When I think about them my heart aches for them.

Recalling their religious beliefs: the whole family converted to Catholicism

long ago, they had a permanent place in the church where they went regularly.

[Page 5]

Chapter 3

Horváth László

Horváth László, a pure true born of "Pöntöle"* . Before the war

he used to harvest and drive a tractor at the Dóra estate in Pálhalma.

It was from there that he was conscripted in the army in 1941.

He was at the front , and was shot in one of the attacks. How or what

he does not remember, only that he woke up in a

hospital. He was wounded in the head and his jaw was broken on both

sides.

"Thanks" to this he was sent back to Hungary to recuperate. He thought

that his army days were over, but things did not turn out this way. He

was put in a special unit that was made up of all the left overs. It was

thanks to this that he met many Jews, those that as yet had not been sent

to the death camps.

Among them was also Frankl Lázsló a landsman from Pentele.

As a soldier he was allowed to move about freely, and had the opportunity

to get a - - - Wallenberg protection paper

Slusszpassz - for him (László) and his friends.

Frankl – thanks to Uncle Laci – survived the war.

- I didn't think about it then, that I am doing a heroic deed. I felt

it was unjust how they treated the Jews. On the contrary. Even after the

war I did not talk about it to anybody. But the people of Pöntöle knew

very well for what should Frankl Laci thank me.

Both were home, but the war was not over. In Pentele the Russians

and the Germans exchanged- hands. At the end, when the Germans entered,

Frankl turned to "Uncle Laci" in desperation: There is a need for

a paper.

And "Uncle Laci" succeeded. A paper stamped with the official mark,

probably in the shape of a horse, from the headquarters in Budapest. Naturally

there were people who did not look at this deed favorably.

-This was not the reason why I did this, but Frankl was not ungrateful.

He gave me a wagonfull of wheat, and a wagonfull of corn as a gift. When

my father asked the government for a parcel of land and received 5 hold,

he said : Here is a tractor. Plow with it. He had a gold signet ring. He

said that when he dies this would be mine. He lived for more than 40 yrs

thank God. When he died his son called me: come for the ring you have deserve

it.

Nagy Lászlo , Horváth László and Harmat Frigyes received

, for their part as National Freedom fighters, memorial

certificates, at the 50 yr anniversary of the end of WWII and the victory

over Fascism. (A HÍRLAP: 1995. V. 9.)

*This is a dialect that was brought over from other parts of Hungary

to Pentele.

1. Raoul Wallenberg, Swedish diplomate that rescued thousands

of Jews from Budapest.

(Dunaújvárosi Hírlap 1996. X. 1.)

[Page 7]

Chapter 4

Tóth Mária (Czékliné)

Translated by Peter Gergay

Donated by Robert Gati

Introduction

|

|

|

|

| Eva eight yrs

|

|

Goldenberg Lajos |

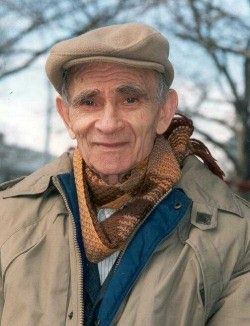

My father, Louis Gati (Goldenberg) was a holocaust survivor. And like

so many of those who endured one of history's darkest chapters, his life

story is filled with amazing tales. But because of the deep scars caused

by his tragic losses and suffering, my father was never able to share much

of his past with me, his only son. Weeding through my dad's personal papers

after his death in May 1997, I came upon a virtual treasure trove of documents,

photographs and other artifacts chronicling his life and times before,

during and after the war. I've become fascinated with these links to the

past and have come to see them as the pages of a personal history that

needs to be compiled, composed and shared. This is not only a story

worthy of being told... but also a testament to my father's enduring spirit

and a record of my family's personal history for future generations.

When the Nazis occupied Hungary in 1944, my father was taken from his

home in the middle of the night and placed in a forced labor camp. Returning

home to his village of Dunapentele after the war, Lajos Goldenberg (his

Hungarian name) learned that his wife Manci and their eight year old daughter

Eva were removed, presumably to a concentration camp.

For more than two years, Lajos waited for his wife and daughter in Dunapentele,

hoping against the odds that they survived the Nazi death machine and would

return home and resume their lives together. They did not survive,

and in 1950 Lajos finally moved on and resettled in New York City where

he met my mother Irene Fried and started a new family and a new life.

When my dear mom passed away in September 1996, my father left his New

York home and came to live with my wife and two young daughters in

Massachusetts for what turned out to be the final months of his life. But

by the time Louis took up residence in our spare bedroom, the loss of my

mother had left him shell-shocked. He had survived the death of a second

wife and once again believed his home had been taken from him. The past

had become a jumble of events, people and places.

But during this dark period came a ray of light: A woman I had never

met nor even knew existed wrote to me to explain that a memorial book had

been compiled by a local school teacher as a memorial to the Jews of Dunapentele.

Ilonkay Józsefné (who I would later come to know as Edit) wrote to

me that within the pages of this memorial, my father and his family were

remembered and spoken of fondly by many of the current residents of Dunapentele

(now known as Dunaújváros).

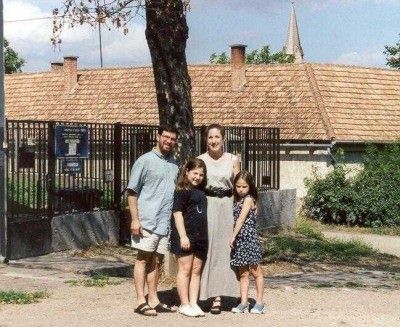

My family and I traveled to Dunaújváros in the summer of 1998.We met

Edit and her family and she introduced me to some of the participants as

well as the teacher who compiled the memorial book. It was truly an incredible

experience which I am currently in the process of documenting in the form

of a film.

|

|

|

Gati family - Dunapentele, 1998

|

These oral histories and recollections are translated within this web

site and stand as a testament to a distant time in another world that only

exists in memories, photographs and now in memorials such as this one.

Please feel free to comment or contact me regarding this memorial book.

Robert S. Gati

Melrose, Massachusetts USA

Lajos Goldenberg: lived on Tót Street (now it is called Petőfi Street)

across from the Post Office). He was an electrician; he had apprentices

(for instance, Feri Potornai, Pista Garbacz). He was humane. At the time

of corn snapping he always permitted his apprentices to go and work on

his father-in-law's rented land in Alájáró (toward Baracs). He once persuaded

my father to buy a woman's bicycle for me, so that I would not have to

walk so much to the vineyards in the Danube fields (the southern part of

Kozider).

His wife was Manci. She was a beautiful and industrious young woman.

For instance, by herself, she lime-washed their kitchen. Their only daughter

was Eva, a curly-haired, blond and blue-eyed child. She was a good student;

at home her mother had her compete with her schoolmate friends: to see

who could write nicer, read and recite poetry better. We loved them and

appreciated them. From them, we got the same feelings back.

The father of Lajos became a cantor and a Shakter (a sort of a butcher).

He was a highly- respected person in their congregation. As a little girl,

I took milk to them daily. When a High Holiday was celebrated by them,

the cantor's wife milked the cow herself for their dishes (kosher food).

I liked this holiday, because I got a lot of unleavened bread from them

(this was Matzos a big, round wafer-like, crunchy food item).

Once when I was 8 year old I went to get the geese. (At that time, in

the 1930's in the Fall it was the custom in Pentele to drive the geese

- 1 gander and 4-5 hens - to the place where the school was located through

the Main (Fő) Street and then they walked on their own through the "Régi

posta (Old post office) Street (now Tisza Street) to graze and bathe in

the banks of the Danube. This went on until the river water did not freeze.

In the evenings, we would await them at the school house.) One Saturday,

the old cantor invited me to the synagogue (across from the school house).

He led me in, holding my hands and asked me to blow out the candles because

their religion forbade them to do that. I remember leaving the synagogue

in total darkness, but with complete confidence in him. Since I saw this

kind-hearted man every day, I regarded his action as very matter-of-fact.

He cautioned me not to be afraid and I was not.

I still think of them with love and respect. There were few days in

my life so sad when they were made to walk to the station. We fought our

tears all day.

[Page 8]

Chapter 5

Garbacz István

I was an apprentice in 1940 with Lajos Goldenberg, master electrician.

It was at that time that I got to know his family better, which comprised

of him, his young, industrious wife and his 4 year old daughter, Évike.

They lived in a longish house situated parallel to and at the beginning

of Tot Street, across from the Post Office. Their building also housed

the shop (Erzsébet Ániszfeld, who deals in small industrial crafts, now

resides there.)

I regarded my master as a very nice person and I appreciated his technical

know-how, as well as valued his devotion and pride in the precise details

of his work. At that time in Dunapentele, it was only he who was on his

own as an independent electrician.

They also raised pigs; on the sizeable lands owned by his father-in-law

corn was grown. They, themselves, did not eat pork; the animals were raised

to be sold.

Since they were religious people, they regularly attended the synagogue

(across from the school). Poultry could only be eaten by them if it was

first killed and prepared by a shakter. There were always smoked goose

thighs hanging in the pantry (just like smoked ham with the Catholics).

In 1944, by which time I was already working with them as a journeyman,

my boss was taken away for forced labor.

The family remained alone. At that time my father was a town policeman

and he warned them of the dangers awaiting them. We packed a lot of valuable

belongings together for them (service parts, bicycles, electrical motors,

etc.) and we hid those at our family residence on Venyimi Street. When

later the Russian soldiers discovered these under a tent cover, they immediately

seized two bicycles for themselves. My father resisted them and he almost

got shot in the head for his trouble. Unfortunately, they took the bicycles

with them. (In fact, they looted them.)

With Ferenc Potornai, (who used to be an apprentice there before me),

we decided to pay a visit to our one-time boss in the forced labor camp

of Csepel in October '44. We were soldiers. After discussing the matter

with Feri, we agreed to help him escape with us. It was our intention to

take him to Nagyvenyim, where he was not known and since we had many good

acquaintances living there, we could have hidden him in that place. At

the 103 Air Defense Battery where I served, the battery clerk was Pista

Ihos, a resident of Dunapentele. He gave me a paper which authorized us

to accompany this man and allowed him to move about freely under our supervision.

At that time Jews had to wear a yellow star. We made him take it off as

soon as we were on our way with him.

At the agreed time, we took him to Kelenföld railway station, so that

we could continue our journey by train to (Nagy)venyim.

To our surprise, at the gate of the railroad station we ran into the

policeman Géza Ragacs, who was also born in Dunapentele and knew all three

of us very well.Fortunately, he spared us any trouble by motioning with

his head to proceed. He moved away from the gate area; he saw no "suspicious"

characters. (At that time, one risked one's life by trying to save or hide

somebody.)

Suddenly, we heard the sound of sirens, signaling an air raid. Everybody

had to leave the railroad station. We went to a nearby air raid shelter.

The bombing started and we knew that no trains will leave that day. Our

boss asked that we take him back to Csepel. To our deep regret, our plan

fell through.

We accompanied him back with an aching heart and we said good bye to

each other.

I returned on October 10, 1945 from a prisoner of war camp. It was then

that we met again, he came to visit us and said that he returned to a great

pain: he could not find his family anywhere and would never see them again.

It was then that we returned the hidden items to him. However, he no

longer worked in his profession, I rented his shop and he got in the business

of hauling goods. He was also learning English. He sold everything in 1948

(whatever little remained for him) and emigrated to America. I never saw

him again.

I can only think of him and his family with a good heart, with appreciation

and with genuine sorrow. They deserved a better fate; they never caused

harm to anybody. Our relatives and acquaintances felt the same way as I

did. The town became poorer without them.

The trade-union used to have its meetings in the Jantsky restaurant.

They also contributed to the cultural life, for example Szekulesz Doli

organized an amateur performance I remember: Mágnás Miska.

[Page 9]

Chapter 6

Orbán Mariska (Pukli Györgyné)

The way of life and customs of the Jews of Pentele

I could have been hardly 8 years old when we moved to (which was then called)

Tót Street. Miklós Sziklai, grocer, lived across from us; we used to go

shopping to his place.

Next to him was the home of Lajos Goldenberg, electrician, his wife

and their daughter, Évike. Her mother always called me to come over to

play. When I got older, this Aunt Manci asked me to help with the housework

because I was told that I am industrious and honest. During school vacations,

I used to spend the entire summer with them and I had an opportunity to

observe many of their customs.

The Jewish religion regards Saturday as the holy day. On Fridays there

was baking and cooking all day and in the evenings, when the sun went down,

the candles were lit, which was followed by the holiday dinner. They did

not work the next day; they went to pray in the synagogue. On such days

they did not light any fires, turn on any electricity, did not eat fruit

which was initially torn off and they did not mix dishes which were for

meat or milk.

They ate poultry and even that had to be killed by the shakter, the

cantor. The poultry could only be cleaned of its feathers drily and after

a special opening, certain parts of the poultry had to be salted, rinsed

in a particular way and had to be kept in water for a while. They could

cook wonderful dishes.

A favorite dish of theirs was the Sólet and they were very fond of bórhesz

which was a large twisted poppy roll. It was kneaded in water so that it

could be served with fatty, meaty dishes, as well. As far as the sólet

was concerned it was a remarkably fine dish. I took it to the baker every

Friday because it was baked in an oven and I used to bring it home on Saturdays.

It was an indispensable dish of the Saturday meal.

Their Easter holidays also required extensive preparations. At such

times they used the Easter dishes which were kept in the attic. No bread

was eaten; only unleavened bread, in other words, matzoh.

They were religious people; they observed the rules.

In the Fall, there were other High Holidays. They celebrated the New

Year and afterwards came the Great Fast when they did not eat anything.

At such times they were in the synagogue all day and they could only resume

eating at sunset and light a candle. Between classes in school, I used

to run over to light their fires and turn on their electricity, which they

could not do on holidays.

One day in 1944, I was not allowed to go to them. As a child, I was

very upset; I could not conceive what possible reason would keep me from

them. Then they were taken to the steam mill area. I went to see them,

they came to the fence but, of course, they would not let me in. Évike

cried and begged me (she was 8 years old at the time) that I should go

in, but it was in vain; it was not possible. I asked Aunt Manci how she

was. She answered: we had been sentenced to death. After that, I never

saw them again.

Perhaps I could write more, but after 52 years, it is not easy to recall

old matters.

I loved them and I learned a lot from them: respect, humaneness, humility.

These characterized all of them.

[Page 11]

Chapter 7

Babanits Irén(Oroszné)

Oroszné (Tót st. today Petőfi st.)

In the spring and summer of 1944: every Jew was herded by the

- ironcross - to the ghetto in spite of their being normal,

working, religious and honest people, that did no harm to anyone. They

confiscated all their personal resources and real estate. They older

ones were herded into carts, the small children and the rest went by foot

on our street to the station, on route to their deaths.

From the whole village there were people who were sorry for them .-My

younger sister's classmate was Goldenberg Éva: blond, blue eyed, an only

child, talented and exquisite, protected by her parents.- Uncle and

Aunt Sziklai, at whose general store we shopped: was a modest couple. They

also gave credit with a good heart. They educated their 2 sons. To our

regret Sándor and Gyuri were taken to a labor camp from where they never

returned. – Their father hanged himself in the attic, but he was cut off

from the rope. – On our st. there lived two older sisters: Regina and Rebeka

. They were religious. When we went to school on Saturday they called us

in to light the wood in the fireplace, because they were not allowed to

do it their holiday. – The cantor's family, his beautiful wife and the

four children. When they put up their succah in their yard, we were enchanted

by it. – Deutsch Panni from the Lengyel Lane: During the Russian occupation

of their kicthen , they used the feather bed from her fine dowry for placing

their bleedy wounded. – The Lax family : Dentist, young wife, a small boy.

In the cultural life of the community they had an active part.

MÁGNÁS MISKA

Operetta in 3 acts

Written by:Bakonyi Károly

Composed by: Szirmai Albert

Director: Szekulesz Adolf

Piano Accompaniment: Dr.Lax Jenőné

Violin Accompaniment : Dr. Lax Jenő , Arató Ede,

Dr. Nagy Zoltán

Their names are preseverd on the plack in the big cemetery . We remember

them with devotion.

I always have my coffee in a small, almost transparent Zsolnay porcelain

cup – decorated with flowers together with a saucer – There are many kinds

of cups but this one I like the best. It is part of a set, a tea

cup, one flour jar that is decorated with butterflies and an ashtray. Relics.

When the more well to Jews learned what was awaiting them, during the

night they threw some of their valuables in the Danube. Who ever sensed

it later took out these dishes or what ever he found. I received these

from an acquaitance and for half a century " they remember" and remind.

Recently a peddler wanted to buy these for 5,000 Forints. They are not

for sale! – I said . Then he doubled the offer. Even if you offer 100,000

Forints for them they are not for sale!- I answered. Then he gave up. My

memories are not for sale.

(Part of Vol I)

[Page 12]

Chapter 8

Dóra Piroska (Pintér

Vilmosné)

I heard from my grandmother that Gőzmalom ( steam mill ) St. ( now Baracsi

St.) was named after the working steam mill in Dunapentele.It was owned

by Bruck Ernö and his wife.

My grandmother owned fields and after the harvest they took the grain

to the mill for grinding. Probably it was this connection that brought

them together, they used to chat frequently between themselves. From her

stories we knew that the Brucks were tidy, deligent and educated people.

One summer, before noon, my grandmother came with a huge loaded basket

from Faragó's store, when in front of the mill she met Bruck Ernőné. She

put down her heavy basket on the ground, and they started a friendly chat.

While talking Bruckné invited my grandmother to her house. The apartment

was furnished like a royal residence with nice shiny parquets,furniture,

hand-worked lace covers, porcelian, those she liked them very much. At

that time rooms like these showed prosperity. In most of the country

houses floors were made of earth. In one of the rooms, a black

piano was seen.

My grandmother went to the piano, and with one finger touched one of

the keys. Bruckné noticed that her guest liked music. She sat down at the

piano and started to play a Hungarian melody. Many beautiful songs were

heard that made my grandmother happy. After that they used to chat about

money, politics, house keeping and economics.

But then came 1944. They were deported together with other Jewish families.

They enclosed them for a time in the silo beside the steam mill, armed

guards watched them night and day. Afterward they were put in wagons and

were sent, poor souls, to the death camps. I only understood from whispers

and half words ( the children were not supposed to know ) that there were

also some very good people, that smuggled to them all types of foods.

I knew that grandmother was one of them. She brought them fresh milk. But

this could only be done secretly, because for this deed one could go to

jail or a get much heavier penelty.

In 1980 I was at the death camp Birkenau where I saw a huge black plack,

with white letters, on it were the names of those Jews that were dragged

and murdered from Hungary. Their names : Bruck Ernö and Bruck Ernőné, were

also seen .

My heart shrunk because they were residents of Pentele like myself,

and will never return to our small community.

After the war the house stood abandoned, with no owner. In the garden

the weeds grew high. The shiny parquets were gone, someone had torn them

out. The doors, the windows disappeared. On nights, when the moon shines,

when the shadows of the trees and bushes are long on the walls of the abandoned

house, the silence is disturbed only by the shriek of little owls. Such

is the house were the master and master's wife will never return.

This happened only becauses they were "others": Jews. Because of this

man to man is wolf .

In the big Cemetery, their names are also written on the marble plaque

where it stands. We hold their memory in grace.

(Taken from Vol I )

[Page 13]

Chapter 9

Nyuli Istvánné (Bölcskei

Juci)

When I heard that the Jews were taken to Bruck's mill, right away I

packed a basket with basic foodstuffs. I had just cooked and broiled

goose meat………in our home at the end of Tót St. Guards stood at the

entrance and they didn't allow me to deliver the food. The

guards were my acquaintances and I succeeded in putting them in their place.

In the end , after great difficulties, I achieved handing in what I had

brought. At the same time I burst into tears seeing their doomed

fate,why... they were just like me and others, the same people of

Pentele.

[Page 14]

Chapter 10

P. Fekete István

The Jews represented a special layer in the community – they had a different

kind of view point on life and of the world, - (because of their being

separate) . On the basic issues they did not intergrate. They married between

themselves.

I loved Uncle Deutch Lajos, the tailor, who gave me a beautiful "boy-coat".

Actually we bought it from him.

(in Hungarian Uncle is an endearment for older people that were like

a real Uncle).

I saw in him a friendly person. Sometimes there was an apprentice working

for him, Hingyi Miska.

I had a special compassion – have it today also – toward a Jewish peddler

named Feith, who had about 8 children and used to walk through the waste

lands with his thin wooden casket. He sold to the farm laborers's wives

lace, draw-strings for their husbands' pants, hair pins, "cream of milk"

lotion and other needy trifles. I can imagine what bitter hardships

he lived by, in the muddy, snowy waste roads, all alone dragging and pulling

his bad bicycle.

The leather tanner, Uncle Deutsch , offered a leather covering for canoes

made from the acid tree.

I remember, before the main film at the movies shown in Jantsky retaurant,

hearing the advertising:

Every civilian and officer knows,

That the best brand of flour is Brucks.

Who ever has anything to do with pigs,

Should use the Brucks' Bran Brand.

Bruck's mill Dunapentele

(beginning of the 40's)

Chapter 11

Memories of the Past

On our street Magyar 55 – today number 29 – lived Dr. Lax Jenő, a dentist

and his wife Kánitz Lili.

They had a charming black haired little boy, Jancsika. He

resembled his parents very much. The dentist's family, were kind people.

They often called me to play with Jancsika because he was an only child

and was lonesome.

There was a long wide mezzanine, running the lenth of the house, it

still exists, but the new owner glassed it in. In good times they used

to have their meals in the mezzanine. They allways offered me delicacies.

Mrs Lili had a piano, she used to play beautifully. I used to hear the

couple singing along with the sound of the panio, but what they were singing

I don't recall anymore. Mrs Lili taught me to play a children's song on

the piano, Boci,boci tarka ( like Freres Jacque).

Dr.Uncle was also very kind and loved children. Because he was a dentist

I was also treated by him, he made fillings in my teeth, and extracted

the bad one( milk-tooth).

On Magyar st. was a big shop. It was torn down. In its place was built

a many storied building. On the ground floor there were many shops (Iron

goods, meat, etc) and above apartments. The building belonged

to Kánitz Mór and his son, they managed the shops. Kánitz Lili became the

dentist's wife.

On the big Jewish Holidays, when I went to the store I saw that Mrs.

Kánitz (Náni) sitting at the edge of the counter, on her head

was a lace kercheif, which even covered her face. In front of her a candle

was burning. My mother said, that today is a Jewish holiday and that she

is praying.

Twice a week the village market was held in front of this building.

At this time there was allways a lot of traffic in the shop.

I don't recall the sad deportation, only what I heard from the grown-ups.

As a small girl I didn't pay any attention to what was happening.

Since then I think of them often with a sad heart.

-o-

In the 30's, my father bought an cast iron bathtub (which is still in

use today) and a small painted iron bed (play pen) at an auction that was

held in the long Jewish House(today Simai house) which was opposite today's

club house. My grandchildren still enjoy it. Both are impossible

to deteriorate. Beside the house a playground can be seen, in the

past a Jewish family used to live there in Erdős house . It was torn down.

[Page 15]

Chapter 12

In the Synagogue

The merchant Farkas Sámuel had one daughter Olga, another Ida, and a

third Ella.

We used to live opposite them on Magyar St and a good friendly relationship

developed between the families, hence I was invited to the eldest's wedding.

I wasn't invited to the ceremony but out of curiosity I did look at it.

It occured at the beginning of the 30's: the bride wore a long white

silk dress, down to the ground, and the groom a dark suit. In the the afternoon

at the synagogues , a rabbi from an other town held the ceremony. The men

wore hats on their heads and were downstairs while the women were upstairs

in the gallery ( that encircled the synagogue).

I don't recall the ceremony in detail because I was a young girl, only

that the groom broke the glass from which they had previously drunk.

The joyfull wedding party was held at the bride's home.

-o-

In the 60's we made an excursion to Szeged. In one of the synagogues

we saw Torah Scrolls. My husband wanted to touch one of them, but

he was not not allowed to, and they explained to him that the meaning of

the scrolls is similar to the holy sacrements for catholics. On a marble

plack, on the wall outside, the names of those that were dragged and murdered

could be read.

Hundreds of martyrs.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dunapentele, Hungary

Dunapentele, Hungary

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Carol Monosson Edan

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Aug 2005 by LA