|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Pages 391-393]

(Janovice nad Úhlavou, Czech Republic – 49°21' 13°13')

Compiled by Karel Polák, Bezděkov

Translated from the original Czech by Jan O. Hellmann/DK

Edited in English by Rob Pearman/UK

Assisted by Dan Pearman/UK

The earliest indication of Jews in Janovice is from 1466, the year in which the Jew Baroch arrived, seeking the protection of Oldřich Janovský, the master[1] of Janovice. In the letter of protection dated 16 April of that same year, Oldřich Janovský declares, in line with the-then royal permission, the conditions for the settlement of the Jew Baroch and his household in Janovice. Each year he is to pay to the master two times threescore sous[2]. For this payment the master promises to protect him and his household within a radius of three miles of the township and guarantees that neither he nor the mayor of the settlement[3] nor his servants will force the Jew to loan money or pay any additional taxes. If somebody owes the Jew money and refuses to pay the debt and due interest, he the master or his mayor will force the debtor to pay. After this time, the Jews disappeared from Janovice and are not found there again until the 17th century.

At the end of the 17th century Jews were moving once again into Janovice. This was in the reign of Vilém Albrecht Krakovský from Kolovrat and Týn who protected the Jews. The richest among the first Jews in Janovice was Abraham Löbl. He is often noted in the Klatovy records as a lender. At the meeting of the municipality[4] on 13 January 1724, it was decided that: “As the Jew Abraham Löbl has not yet paid the amounts due for the property entrusted to him from the Fragner bequest[5], he shall be reminded. In the event that he does not fulfill his duties, a letter asking for help shall be sent to the Steward at Týn[6]”. On 15 March 1724 the following was decided at the meeting of the town council: “A reply is to be sent to the letter from Baroness Dejmová concerning Löbl, who is denying everything, and a certain farmer by the name of Kosta shall be called in for interrogation”.[7]

At the meeting of the town council on 16 April 1731, it was decided that: “Based on the report from Dešenice of the Mayor, Mr. Augustin Švarz, concerning the matter of Jan Pechan owing money to the Jew Abraham Löbl from Janovice - the debt being guaranteed by Vilém Bartovic but not having been settled - Jan Pechan and Vilém Bartovic shall deposit the money at the council for further handling. This is the answer to be given to the Mayor of Dešenice”.

In the land register of the manor of Janovice, we find the following Jewish cottages:

On 24 July, Václav Sinterhof sold, with the manorial authority's permission, a cottage to Moises Ezechiel, a Jew in Janovice, for 90 guilders. The sum was paid immediately.

In 1742 the merchant Abraham Löbl bought in Nýrsko the so called “Judenwinkel”[10] house, which later received the house number VII. In 1756, he passed this house down to his son Schmul (Samuel) Abraham Janovický. This was because his second son Meir Abraham bought a house from Khana Oesterreicherová in 1749. This house was later given the number XVIII. These two brothers formed a trading company with the name “Meir and Samuel Janowitzer”. After the death of Meir it was called “The heirs of Samuel and Meir Janowitzer”. This company was short lived because in 1790 Samuel Abraham Janovický had already made a formal contract with his sons Volf and Abraham for a business trading in feathers and wool that was valid for six years – see J. Blue: Der böhmische Bettfedernhandel, Mitteilungen, year 1931, no. 1 and 2[11].

In the land register for the town of Janovice, according to the list of taxpayers for 1790, we find Samuel Abraham in house no. I. His land tax was four sous a year. In house no. II we find Rubín Nathan, whose land tax was one sou. In house no. III we find Isaak Joachim (three sous); in house no. V, the Jewish Community (2 sous); in house no. VI, Jakob Nathan (two sous); and in house no. VII, David Volf (16 sous).

In the Týn Manor in the township of Janovice the Jews had no reason to complain about the manorial authority unlike the situation in other manors. The inhabitants of the township who worked the fields considered a trade or craft as an auxiliary income and therefore did not interfere with the Jews. It was different in Plánice or Kdynì. In 1661 Maximilián Valentin from Martinice instructed the citizens of Plánice not to admit any Jews into the town now or in the future and only to tolerate those living there already. In 1720, Count Jan Filip Stadion expelled all the Jews from the Manor of Kout. However, the Jews defended themselves and refused to move. In connection with this situation, the steward of the Kout Manor suspected the regional steward to be 'smeared with golden cream'[12]. Even so, in 1725 he advised the region to expel all Jews. According to him, 'the peasants would have a much better life without the Jews. As it is now, the women are secretly taking corn from the store and taking it to the Jews in exchange for some piece of lace or a veil which brings profit to the Jews and enables them to swindle'.

In 1784, the merchants of Kdynĕ complained that the Jews Mosaj Isak and Machrl Hahn from Kdynĕ, being under the protection of the manorial authority, peddle a variety of goods without paying respect to Sundays or holy-days. The Steward of Kout threatened the Jews with punishment and the confiscation of goods.

In times of war the Jews had the opportunity to make a profitable business. During the Thirty Years War, they helped both sides – the Empire and the Bohemian Princes. During this war many Jews became rich by supplying the armies and their suppliers, such as Heřman and Jan Èernín. For their services they (the Jews) received privileges. For example, in 1628 and 1648 they received permission to trade with all and any goods in all the markets of the Bohemian crown.

On 16 May 1788, a contract was also concluded at the manor of Týn between its subjects and the Jew Samuel Janovický from Nýrsko concerning the supply of 261 bushels of rye and 659 oats into the governmental stocks at Budĕjovice for 285 guilders and 18 sous. Beside the signature of Samuel Janovický on the contract are the signatures of all the manorial village mayors.

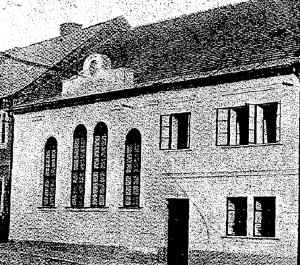

According to the inscription above the entrance, the prayer house in Janovice dates from 1723. The prayer house was built in the baroque style by an unknown master. Judging by the castellated banister in the galleries, it is possible to consider him to be the same master as the one who built the parish house in Janovice.

The prayer house is not large. It is situated just beside the single floor Jewish school, which is separated from the prayer house by a wall and covered by a saddle roof[13]. It seems that the original baroque gables disappeared during a fire. Inside, the prayer house is almost square – each side being 9.5 m long and the walls being 1m thick. Two richly glazed windows face the street on the adjacent and rear sides. The squat vault is flattened by a pendentive[14].

The facade is ornamented with double lesenes[15] between the windows and with capitals at the ends of the building. Above the entrance hall is a gallery for the choir, with three half-arched glazed windows to the prayer hall and with a castellated baroque banister. The gallery is illuminated by a window facing the street above the prayer hall. The corners of the prayer hall are chamfered[16] to improve the stability of the vault.

The Jewish cemetery at Hvízdalka is from the same period as the prayer house. It is possible that there are earlier graves, but at such a time the cemetery was much smaller.

It is interesting to note our observation from the records of the parish of Janovice. In the period 1840-1850, it was recorded that 32 children were born outside of marriage and in just 15 of these cases the name of the father is recorded. Such a large number indicates that – like the Catholics – the Jews were poor.

According to the records, the Jewish community of Janovice comprised in the period 1807-1860 the following villages: Janovice, Bezdĕkov, Týnec, Klenová, Pocínovice, Louèím, Lipkov, Dlažov, Bĕhařov, Miletice, Soustov, Spùle, Slavíkovice, Mlýnec (1860), Maloveska (1844), Zdaslav (1842), Smržovice, and Modlín.

The highest number of Jewish houses is noted in the first half of the 19th century. In 1824, we find house no. XXIX is in the hands of the Jew Isak Steindler.

The abolition of serfdom and of the treadmill was not to the direct advantage of the Jews, but the enlivening of the villages helped them to have a better life, as the inhabitants needed the financial means provided by the Jews. The freedom of 1848[17], even though short lived, was greatly celebrated both in the towns and villages by large festivities, especially by the guardsmen, and money flowed much more easily. It is certain that in these times the business of finance was still in Jewish hands, providing an opportunity to make a good profit.

Nevertheless the crises of the 1870s and 1880s heavily influenced the Jews, especially those among them that were poor. They followed the example of groups of inhabitants and moved to America with their whole families to find fortune and a better life. Also the number of Jewish families in Janovice was shrinking, and around 1891 there were just 11 families totaling 60 persons remaining. The Jews also moved out later, and today there are just three families left: the families of Suchařípa, Feldman and Lederer, the owner of the feather mill.

Today Janovice is under the care of Rabbi E. Klauber from Nýrsko. The income of the reduced community is no longer sufficient to have its own official.

Among the rabbis, the following are noted: 1811-1851, Šimon Levitoch, teacher and record keeper; 1851-1852, Ludvík Pollak; 1854, Leopold Müller; 1857-1867, Jakub Stein (he was also the mohel and record keeper); 1872, Karel Polesí; 1873, Salomon Kulka; and then Dr. Reiser, the father of Dr. Reiser from Klatovy.

Among the teachers, the following are noted: 1807-1810, Samuel Löwy; 1811-1851, Šimon Levitoch; 1834, Rudolf Kahn; 1851-1853, Jakub Töpfer (before that he was the school assistant); 1871-1873, Bernard Klein - teacher and postmaster in Janovice; 1877, Rafael Richnovský; and after them the teachers Weiskopf, Gans and Beck.

Among the mohels, the following are noted: 1842-1845 Wolf Sieber, qualified mohel; 1818-1842, Jonathan Kahn; 1846-1862, Leopold Weis; and 1857-1867, Jakub Stein.

At the census in 1890, some of the Jews pronounced themselves to be of German nationality[18].

|

|

|

||||||||||

Footnotes

Links

Short story and photos from the cemetery. In Czech: http://pamatky.kehilaprag.cz/hledani/janovice-nad-uhlavou

Photos from Jewish Janovice in Czech: http://www.zanikleobce.cz/index.php?obec=6079

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Jews and Jewish Communities of Bohemia in the past & present

Jews and Jewish Communities of Bohemia in the past & present

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 05 Aug 2020 by JH