|

|

|

[Pages 86-87][1]

|

By Menakhem son of Shimon Katz

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

The economic situation of Brzezany's Jews was hard for all generations and at all times. While a slight improvement occurred at the end of the 19th century, it benefited only a few people. For most Jews, the phrase “By the sweat on your face, you shall eat your bread” [Genesis 3:1] would apply. The truth is that there were some wealthy people, and there was a middle class, but the masses struggled, worked, and toiled to earn their bread.

Brzezany and its surroundings had no natural resources, industries, or mines. There were a handful of wealthy people, such as owners of estates, lumber dealers, processors of flour mills, bank owners, and distinguished owners of houses. These people were also the guides, direction indicators for community affairs' handling, and deciders in public affairs. In his story, “Hakhnasat Kalah” Bridal Canopy,”] Sh. Y. Agnon describes one of our city's wealthy and prominent families, the Rappaports. Many stories were told about that family.

I also have such a story, and it goes as follows: “The family had several daughters. The first married a great scholar from Russia from the famous Brotzky family. A short while after the wedding, he was stricken with depression, which lingered for the rest of his life. When his second daughter reached marriage age, the father set out again on a wagon to Russia to bring a groom for his second daughter. Families from the city and its surroundings were not wealthy or distinguished enough for him. On the way, the wagon owner's whip broke. When they reached a forest, the waggoner got off and entered the woods to find another whip. He stayed there a long time, and when he returned, he held a crooked whip. The wealthy man asked him angrily: ‘For such a crooked whip,

|

|

[Page 89]

|

|

you had to enter so deep into the forest? Couldn't find such a whip close to the road?’ Using the words of the wealthy man, the waggoner replied rudely: ‘And for such a crazy “getsle” ([or urchin, meaning] the wealthy man's first son-in-law), you had to travel so far to Russia? Couldn't you find such ‘a bargain’ by us?’ “You are right,” said the wealthy man. “The ‘Finger of G-d’ is showing me the way. That was a hint from the heavens,” he said, turning around.

As a portion of the overall Jewish population in the city, the wealthy constituted just a small percentage. After them, in second place was the middle class. It consisted of lawyers, physicians, Jewish government officials (such as judges, schoolteachers, bankers, and railroad officials), and some established merchants. Although the number of middle-class people was also small, it was bigger than the upper class and not less important. They carried the burden. They were the majority of the leaders and public affairs activists. They were also our representatives with the authorities and the speakers on behalf of the community. Most of these people did their work dedicatedly, for the sake of it, voluntarily. They also headed welfare institutions. They were accompanied by poor-class craftsmen or just kind-hearted people willing to help others. The latter worked modestly, devotedly, and gently, and they volunteered to help anonymously. The third class consisted of most of the craftsmen (a small portion was in a better situation), small merchants, workshop apprentices, store helpers, household workers (most of whom were women), all sorts of peddlers, market stall owners, wagon owners, porters, and other people who made a living doing any casual work. Most of the latter walked around in the market, bought produce (such as flax, poultry, eggs, butter, and cheese) from poor and small farmers, and sold the produce to merchants with a meager profit of a few pennies.

Craftsmen, like everybody in their class, worked hard. They started the workday at sunrise and worked all day without a break until sunset. That is if they had work, which was not always available. Most of the craftsmen in our city were Jewish: tinsmiths, glazers, carpenters, bakers, shoemakers, painters, and more. During those days, they had already organized in “Yad Kharutzion” [literally “dedicated hand,” the name of the Jewish craftsmen guild].

A dedicated corner in the market square was allocated for the waggoners and porters. They were the pugilists, the defenders at times of need, and the frontline in any assault or riot in the Jewish streets. Most of them married among themselves and were all relatives or blood relatives. During idle times, they sat down or stood around the wagons and talked to each other. They told each other about their life and consulted about things that bothered them.

One small story typifies those people. Among the waggoners, there was a Jew by the name of “Yukl.” His nickname was “Firer” (the transporter [in Yiddish]) because his work was to transport garbage from the yards. He was a simple man with a short stature and a long and narrow beard who dreamt about being rich all his life. He always bought lotto tickets and one time he won. All of his three numbers matched, and he won a large sum. When people heard in the morning about it, big excitement enveloped the city: “Did you hear? R' Yukl is a rich man! He won the lotto.” They were still talking when he appeared. The waggoners took him aside, sat him down on a wagon, gathered around him, and called him in a chorus: “Tell us! How did it happen?” He settled himself on his seat “feeling like a wise rich man who knows how to play the game,” took a deep breath, coughed, and began to tell: “It was a wintery Friday night, after dinner. I laid down to rest a bit after a week of hard work. I fell asleep, or perhaps I had not slept yet, and my aunt Yenta, may she rest in peace, appeared in front of me and approached me. I saw her as if she was alive, like in the old days when I brought her some food my mother had prepared.

[Page 90]

And she told me: ‘Here are three kreuzers [Austrian pennies]. Go and buy yourself seven sandwiches.’ I woke up and immediately understood the meaning of my dream. She brought me my salvation. “But Uncle Yukl” one waggoner from among the young ones interrupted impatiently, not wanting to wait for the end of the story, “In your dream, your aunt gave you only two numbers, three and seven. Where did you take the third number 22 from?” Uncle Yukl responded: “What is the problem? Three I had, seven I had, three times seven is twenty-two!”

‘How is that?’ interrupted that waggoner again, ‘Three times seven is twenty-one, not twenty-two.’ ‘Wh---------at?’ said Uncle Yukl And after thinking about this for a few minutes, he continued, ‘It is possible that in arithmetic, you are right, but in life, with such wise calculations, you will never win.’

All the people in that class worked hard but still needed support, once and a while, in the form of a loan or financial assistance.

Quite a substantial portion were the poor people who had no income. Their entire livelihood was dependent on public support and welfare. Their situation was not easy, despite what was provided to them. Their state was expressed in a phrase of the “Birkat HaMazon” [Grace after meals]: “Lord our Gâ€'d, please do not make us dependent upon the gifts of mortal men nor upon their loans. “The poverty in those days was indescribable. The poor were hungry for a slice of bread. Some among the poor were ashamed to ask for a handout and were dying from hunger.

Therefore, it is easy to understand the reason for the massive Jewish emigration in the late 19th century and early 20th century when the gates were opened to the bigger world, to a country where all people are made equal, there is bread for everyone, work for all, labor shortage situation. That country was vast and rich and provided opportunities to earn one's living with dignity. Multitudes left to find their fortune in distant America, but even there, these people did not have easy lives. In the beginning, singles went, and later the heads of families. The wives and the children stayed behind to allow the fathers to work peacefully and earn enough money to bring their families to America.

|

|

[Page 91]

That emigration wave brought with it many tragedies. Some of the husbands who had emigrated disappeared. It is unknown until today what happened to them. They may have died (from an illness or hard work) or perhaps remarried without divorcing their first wives. It was difficult to know the truth during those days. They left a wife with all her children, who remained “Agunah” [a Jewish woman who cannot remarry according to Jewish religious law], destitute, with no means to make a living, and hopeless. During those days, there was no government welfare program, and the government did not aid their poor people. Without the mutual aid offered by the community, the Jewish poor could not have survived. Charitable Jews established welfare institutions. Compassionate people helped - one person brought bread, another – medication for the sick, and yet another – shoes or a dress to cover one's body. Thanks to that assistance and despite the harsh conditions, the children grew up, learned what they learned, and achieved whatever they achieved. They did not die from hunger and did not fall into bad ways.

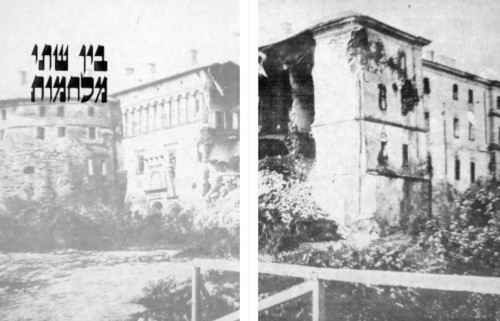

The various wars that took place in the years 1914 – 1920 had a severe ill effect on the Jews of our town. Most men between the ages of 18 – 55 served in the army. A substantial portion of the Jews left the city and escaped westward. During the war years, the sources of livelihood were completely ruined. Most of the houses were burnt or destroyed by shells. The city served as a front for a whole year and transferred from hand to hand several times during the six years of war. The surrounding area's peasants took advantage of the opportunity every time the regime changed and looted and robbed Jewish properties. Jews who still had real estate sold it to survive, but the money they had received lost its value overnight.

When the wars ended, the city Jews tried to rehabilitate their lives. They tried to return to economic and spiritual equilibrium or even improve the situation to achieve organized lives. However, they were disappointed quickly and concluded that the opposite was true. There was no future for Jews and no hope for changing their situation. I will briefly describe the economic state of most Jewish families in our city.

[Page 92]

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

Merchants who returned home rebuilt their stores, each according to their ability. The young soldiers and the youth who grew up during the war and had no opportunity to acquire a trade now turned their attention to business. The number of merchants grew more than this economy could support. That resulted in vigorous competition. As if that was not enough, a new competitor rose, stronger and more dangerous, since the regime was on its side, and so was the law (or more accurately – distortion of the law, to take this essential occupation from the hands of the Jews). The competitors were the Poles and the Ukrainians, who introduced the elements of using physical force and propaganda, made available to them by the government, into the competition game. The introduction of these elements bore fruits. Some Jewish merchants liquidated their businesses and made Aliyah to Eretz Israel (Grabski's Aliyah)[2]). Unfortunately, not all those people succeeded (for known reasons, [a severe economic crisis in Eretz Israel]) and returned disgruntled and broken.

Under these conditions, trade became more complicated and less possible from one day to another. Under the initiatives of two merchants, a Pole called Shlosrek [?], and a Jew named Ya'akov Miteleman, the merchants organized themselves in a merchants' union. A gathering of merchants took place in our city on May 5th, 1922, where a committee of eleven members was elected. A union court and audit committee were also established. They decided to call for a gathering every two years to hold new elections. A year later, the union joined the Polish Guild of Eastern Poland.

The following people were elected to the first city committee:

Yaakov Mitelman – Chairman

Wagshal Hersh – his deputy

Goldman Barukh – second deputy

Baran Mauritzi – secretary

Tzukerkandel – his deputy

Taler Yehoshua – treasurer

Reikhbakh Leib

Horovitz Shlomo

Rot Eliyahu-David

Fuks Meir

Roza Yeshayahu

Besides the objective under which the organization was founded, it had its own fund for short-term loans, tax consulting services, and consulting services for business accounting.

Upon the entrance of the Soviets, the trade was eliminated entirely and was never renewed.

[Page 93]

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

Only a few Jews served in government positions, most of whom remained from the days of the Austrian regime.

Two Jewish judges served in the court: Tadnier and Hornik.

Three teachers taught at the high school: Dr. Shekhter, Horovitz, and Shleikher.

Two physicians: Dr. Pomerantz (who served as a municipal physician and at a clinic) and Dr. Bakhman (a military physician – not in Brzezani).

All these people (except Dr. Bakhman) were active in the city's public life.

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

During and right after the First World War, Dr. Felk was the only Jewish physician in the city. He remained active until the end of his life. Dedicated and responsible, he was very popular within the Jewish community. A few more Jewish physicians were added in the years between the two World Wars: Dr. Shomer, a beloved and respected physician by all people in the city. He was a Zionist and public activist who dedicated time from his free time to improving the lives of the Jews in the city. He treated poor patients for free. Dr. Pomerantz, who held government positions, practiced very little in a private clinic. He was the chairman of the Jewish drama club in the city. Dr. Kornberg stayed in Brzezany only a short time and then moved to another city.

A few more physicians became active during 1930 – 1940: Dr. Arye Feld, an alum of “HaShomer HaTzair” and an activist from his youth until his last day. Dedicated and skilled, he was the only radiologist in the entire area. Dr. Vagshall (Shaklai) – very active in Jewish life in the city. Some other physicians graduated abroad and did not have a permit to work in Poland. They began practicing as physicians only during the Russian conquest: Arye Falic, Lileh, Hibler, Landau, Dr. Moshe Frid, Yosef Meiblum, and Riner Khaim. They all left our city at the end of their studies. Meser and Veinshtein immigrated to South America before the War. Rozen, Vinter, and Likhtman studied abroad but have not graduated as of yet. Shekhter did not return to the city either when he completed his studies.

Two dentists worked in the city: Doctors Diness and Vondermeir and a few dental technicians. They all had a license to operate a private clinic, earned their living honorably, and their situation was good. I also have to mention here Dr. Lebel, a children's physician. He was very active in the life of the Jews in the city.

Most of the physicians were also active during the Nazi regime until the elimination of the ghetto. Dr. Shomer and Dr. Arye Falik served in the Soviet military and survived the War. Dr. Vagshall survived the Holocaust.

[Page 94]

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

According to the law in those years (after the First World War), pharmacology required an academic degree. The law demanded three years of studies in a university and working in the profession for one year. In pharmacology, like in medicine, “Numerus clausus” was imposed, so only a few were admitted. Our youth, who aspired to study for that profession without any limitation, went to study abroad. The degrees of these graduates were not recognized in Poland, and they could not secure work. They were allowed to work in their profession only during the days of the Soviet regime. Even those who graduated and secured a license could not find work. The Polish authorities avoided giving Jews permits for new pharmacies. Most of the pharmacies owned by the Jews remained from the days of the Austrian rule. That was just one of the economic obstacles enacted by the Poles against the Jews.

Brzezany had three pharmacies, two of which were owned by Jews. The first one was Pohoriles's, and the other was Goldman's. Two additional pharmacists, Magisters Orenshtein and Laufgang, had licenses.

Those who completed their studies abroad and did not receive a work license were: Glazer, Kh. Khaigenbuam, Noishiler, Tonis, Rubinshtein, Shvartz, and Oberlender. Some left Poland before the War to look for work overseas.

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

Many lawyers made a living in our city due to the large number of court cases in the only district court in the area. At the end of the 19th century, twelve of fourteen lawyers were Jewish. They made a good living before the First World War, and most were involved in public affairs. After the War, their number grew and reached forty (besides the Polish and Ukrainian Lawyers). That resulted in stiff competition, and some lawyers, particularly some of the young ones, had to work hard for their income.

That growth happened because, unlike other professions, there were no limitations on admitting Jewish students to the university in that profession. Everybody who completed their studies received a license without any difficulty. I will mention only some of them who remained in my memory: Ravitz, Nagler, Oberlender, Goldshlag, Landsberg, Milkh, Glazer, Vilner, Klarer, Finkelshtein, Grossman, Reikh, Lopater, Fridman, Reizman, Baigel, Riger, Noiman, Bleiberg, David, Salomon, Glikshtern, Nussbaum, Laber, Trauner, Binder, Erikh, and others.

Some of the lawyers, natives of Brzezany, who moved to other cities were: Freier, Leib Glazer, Brunek Fridman, Lifshitz, and others.

Many lawyers were prominent in their profession and were also dedicatedly involved in public affairs. They were very active and unforgettable.

Some lawyers were registered in the Golden Book of the KKL-JNF by the city Jews for their loyal and dedicated activism and work.

Most of them perished in the Holocaust.

[Page 95]

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

Only a few of our youths studied engineering since they knew they could not secure government or municipal positions. There were, however, a handful of Jewish engineers: Pinion Frid studied abroad and did not find work in his profession. He made Aliyah and worked as an engineer in the Haifa municipality. Merkur also graduated but could not secure a job until the Second World War. Landesberg converted to Christianity and was accepted for a government position. Noishiler, the youngest one, completed his studies with the outbreak of the Second World War.

|

|

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

The situation of the craftsmen did not improve after the First World War, and in many cases, it even worsened. Those who managed to learn a profession did not find work since the experienced craftsmen hardly made a living. There was no future in our city for the working youths. They joined youth movements hoping to make Aliyah to Eretz Israel. However, unfortunately, the Aliyah was very limited in those days, and people had to wait a few years for an entrance permit. Those who made Aliyah were saved from the claws of the Nazis. I will never forget the youth we lost, filled with energy, goodwill, and creativity, who did not live to see their aspiration fulfilled. Only a few found refuge in South America.

Translator's notes:

By Dr. Eliezer Shaklai

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

On the eve of the outbreak of WW II

During the period between the two World Wars, the economic situation of the Jews deteriorated. The Poles, and by us in Eastern Galitsia, also the Ukrainians, were determined to rob the Jews of their economic basis and the sources of their livelihood. They implemented their wish.

The Polish government supported them by enacting various laws the Jews could not withstand. On one side, it imposed high unjustifiable, and unreasonable taxes that brought the Jews into bankruptcy, and on the other side did not allow the Jews to advance in the free professions (Numerus Clausus, Numerus Nullus). With some laws, the Polish government aimed at angering the Jews and taking revenge on them (for example, the elongated debate about ritual slaughtering). Under that environment of competition and warfare against the Jews, for the sake of it or not, the hatred by the non-Jewish population against the Jews strengthened, and the atmosphere became electrified more and more.

One tiny spark could have caused an enormous fire. Indeed, even before the war, there were some attacks, and several Jewish families were murdered.

The situation of the Jews in our province was extremely harsh. Most of the population was Ukrainian. The villagers (farmers) were Ukrainians, and a substantial portion of the city intelligentsia was also Ukrainians. The Polish government tried to “remedy” the situation by bringing Polish farmers from Mazovsha [Mazovian?] province – radical nationalists and antisemites who tried to suppress the national awakening of the Ukrainians that increased day by day. As a result of the external influence (Germany) and the internal influence (the radical Ukrainian intelligentsia), the interaction between the Poles and the Ukrainians escalated into fistfights, bloodshed, arsons, and murders. However, the real victims and the scapegoats in these battles were the Jews. They suffered beatings from both sides. Both the Poles and the Ukrainians used any opportunity to hurt the Jews first. Many Jewish families were harmed in property and lives. The political situation in the world should be added to the economic and social background of our city's Jews. The war atmosphere was felt in Poland as early as 1933 – since Hitler rose to power.

We all remember well Nuremberg's laws, the robbing of Jewish properties, Crystal Night, the expulsion of Jews from Germany and Austria, the closure of the borders for Jewish refugees, and the Evian Conference and its resolutions. All of that before the outbreak of the Second World War.

The beginning of the War

The war atmosphere was felt in our city a long time before the outbreak of the war, created by the many refugees who were expelled from Germany to Poland. The Germans sent them out beyond the border because they were former subjects of Germany. There were refugees from Austria and Germany in our city too. We knew the war would eventually come, but when it did happen, it hit us hard and caused a real shock. We were not prepared for it, neither physically nor mentally.

[Page 97]

Though we heard on the radio and read in the newspapers about the approaching war, people lived their daily lives as if the news was not their concern. We were dreaming when the first siren woke us up. The choking atmosphere of war intensified. As early as the first day of the war, we realized how much we were unprepared. We were gripped by panic, and the enemy made use of it. Our people tried to enlist, but it was too late because the military warehouses had no uniforms, guns, or supplies.

“Go and stay home,” they responded when we came to enlist. The confusion and lack of order increased by the hour. A siren could be heard every few minutes. We were taught that people should advise others about the approach of enemy planes by ringing bells, whistling, and yelling. The noise was so loud that people got confused and did not know what to do. The noise from sirens rose to the heavens, and people ran around without knowing where and why. Fortunately, during that period, we did not suffer from bombing, and there were no casualties.

The evacuation eastward, on loaded trucks and wagons, began as early as the first days of the war. High-level officials and military officers escaped after a few days in the direction of the Russian-Romanian border. As usual in these cases, the roads were clogged by people and vehicles, which resulted in many accidents. In addition, the bombing by the German air force caused many casualties. Many wounded people were left on the roads, and some reached our city. We assisted them as much as we could. We worked day and night without feeling tired. Everyone wanted to ease the situation somewhat, help, and participate in the campaign, although we knew that all was lost.

We also saw a lack of order in the supply of food. In our area, food was always in abundance. Our region was first in the export of butter, cheeses, eggs, and grains. But everything disappeared in the early days of the war. The was no bread, cheese, or eggs. A barter market commenced, and money lost its value.

Britain announced joining the war against Germany two days after its outbreak. A day later, we heard, on the radio, about France's decision to join the war against Germany. However, it was too late for us, the Jews. That could not have helped us at all.

It is hard to describe the days of the wars - the retreat, panic, fear, sirens, lack of order, and most of all - hopelessness. There was nothing we could do. Along with the rest of the Polish army, part of our youth who served in the military became prisoners of war either by the Germans or the Russians. Some of our citizens managed to escape to the Romanian border. Two buses filled with men from our city went out eastward. Among the escapees were Dr. Vilner, Dr. Risman, and Judge Yosef Noiman, may he live long. Some of the escapees returned from the middle of the road. Some became captives of the Russians, and only a small portion managed to cross the border to Romania and save themselves.

On Sunday morning, 17 September 1939, we heard on the radio that the Soviets crossed the Polish border. The news was passed around very quickly. In the beginning, we did not believe it but the rumor was confirmed at noon. Salvation would come from the East. We saw it as an opening for a rescue. The Soviet tanks entered our city on Wednesday, 20 September 1939, at 11 AM. They came from the direction of Adamovka. They did not stop and continued on their way toward Rohatyn. A few Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish residents gathered at the city hall to welcome the guests and greet them, but the Russians did not stop, even for a minute, and continued on their way without paying any attention to the delegation.

[Page 98]

The first impression of the Soviet army invoked dismay – poverty was projected from their faces and uniforms. Since we did not know at the time that the entrance of the Soviet military would be temporary and that calamity would befall our city and our people, we felt relieved. We were sure that the big disaster was averted; we were saved from the Nazi regime.

The Soviet Rule

The army and the communist officials arrived after the first tanks passed. A revolution occurred in our lives overnight. A silent revolution, with no bloodshed, but a 180-degree change of direction nevertheless. It was like a fulfillment of the [Talmudic] phrase: “…upper ones down and lower ones up.” They first released political prisoners from jail. They used these people to establish their regime. They also used them to execute all sorts of illegal tasks. They extracted from these prisoners all the information they needed – data about every person, who could be relied on, and who should be eliminated? The Soviets temporarily divided the positions among the local communists – some high-level authority positions, such as the mayor, and some low-level ones. The local communists recommended to the Soviets local unaffiliated people who could be trusted.

The local communists, who did not know the Soviet laws, did all the work of the Soviets: allocated grants, imposed taxes and customs on many merchants, confiscated a portion of their properties, and plundered their houses and furniture. Later on, Russian officials came and got rid of the local communists, took their positions, and slowly introduced the actual Soviet regime. In the first few days, people thought to return to the routine life of the time before the war; the shopkeepers opened the shops, and artisans returned to work, each in his own profession, but the true reality became known quickly.

The Russians were good customers. They quickly bought everything there was to buy. The money lost its value; new merchandise was not available. The stores emptied and closed within a few days. It was difficult to find bread, let alone butter, eggs, and meat. The farmers did not sell vegetables for money. The farmer felt that he would not profit since the authorities demanded he hand over part of his produce, and all this as a down payment. Since the demanding people were the local communists, most of whom were Jewish, the hatred toward local Jewish communists became a grudge and animosity toward all Jews.

The face of the city changed within a short time. The trade ceased, and the shops closed. The framers hardly paid a visit to the city. The search for a day's work, scarcity, and depression prevailed. In the meantime, the population continued to grow by the day - through the flow of refugees from Western Poland who managed to cross the border.

Russian officials and their families came from the East. Thousands of people came from neighboring cities like Zolochiv and Ternopil. They left their cities for fear or because they were forbidden to reside there. Some had the means to make a living, but others arrived penniless.

[Page 99]

The city population of thirteen thousand grew to thirty-five thousand people with about twelve thousand Jews (compared to three thousand local Jews). The main problem for the Jewish refugees was lodging. Some converted shops into apartments, others found a shelter at the large synagogue, and most resided with the non-Jewish population in the city suburbs after paying a fortune. Many fell sick due to the crowded conditions. They were not helped by the authorities. The local Jews made every effort to assist them, but because of the extreme poverty, their assistance was like a drop in the sea. A second problem faced by the Jewish refugees was getting food. As aforementioned, shops were closed, the farmers avoided selling their produce, and the prices soared. The locals blamed the refugees for that, and from their side, the refugees blamed the locals for being evil.

A committee to assist the refugees was established in secret because the Soviets forbade the existence of such associations, even for charitable purposes. Toward the end of the summer, my late father and two more Jews went on a secret mission to other cities to collect money for the refugees. Some donations were substantial, but [as the phrase in the Talmud says] “the handful does not satisfy the lion.”

Over time, some refugees returned to the German side, but most of them found their place and livelihood in the city. Some others were taken out of their homes (among those who registered to return to Germany) and transported to Siberia along with some locals (Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews).

In 1939, elections were held in Eastern Galitsia. That was a referendum to determine the future of that region. One or two representatives from every city were elected to a conference that gathered in the city of Lviv. It was decided in that conference to ask “Batyushka” [Father] Stalin to accept the region under his patronage. They thanked Stalin for “freeing” them from Polish enslavement on that occasion.

That winter, they notified us of Stalin's agreement to have us join the big Soviet family. A command was then issued that every person should secure an identification certificate as a Soviet citizen. Whoever did not want such a certificate had to fill out a detailed form where they wanted to move to and indicate their local address. The Soviets sent to Siberia those who registered as refugees who wished to return westward, along with some of the people whose passport was stamped with a “paragraph” or clause (explanation below). However, an identification certificate only did not prevent a city resident from being moved to another location. Everybody had to work and try to find a permanent job, otherwise, the Soviets could have sent a person to work somewhere else (e.g. the coal mines in the Donbas region).

The Jewish population in the city was divided into several categories: 1) People who had free professions, such as lawyers, judges, teachers, and physicians. 2) Craftsmen such as shoemakers, locksmiths, carpenters, glazers, and painters. 3) Most people were merchants, business owners, peddlers, or people without any profession. The letters and some of those with free professions were forced to change their occupation and look for other work, sometimes physical. However, a radical change occurred for everybody. Physicians, pharmacists, teachers, and engineers became government employees who were not allowed to work privately. Craftsmen were organized in cooperatives. These cooperatives had a manager, accountant, secretary, and domestic workers. The lawyers joined a cooperative under a decree from above, where only a limited number of lawyers were accepted. Every accepted lawyer had to secure an agreement with the Communist Party. Most of the intelligentsia occupied positions as accountants, secretaries, or work organizers.

[Page 100]

Although there were plenty of places for work, many people remained unemployed. Some of the merchants tried to create jobs – they founded, with their own money, small factories, in the form of cooperatives so that they could claim they had permanent jobs.

Every person had to carry an identification document containing details about the residence and work. Some had a “paragraph” or a marking on the ID, indicating that the person had a flaw or stain in his past or present. The ID was valid for a period of up to five years. People with a “paragraph” mentioned on their ID received their ID once a year or sometimes once a month. After the stated time limit, the person had to renew the certificate. Every person had a personal card at the NKVD [Soviet secret police]. The card contained details about the exact address, biography, biography of the parents and grandparents, and the family. When needed (nobody knew when that would happen and why), the card would be pulled out, and the individual would be invited to the NKVD, always after midnight, where he would be reminded of the "sins” of his youth (such as being a Zionist).

I am not able to describe in detail life under Soviet rule. I will only provide a short description of life during that period.

Life under Soviet rule was not easy. There were people who, by a command, had to appear once every week or two, after midnight, under a false name, to the NKVD to provide a detailed report about what they saw and heard at their residence or work from friends and acquaintances. Every place of work had several such people (snitches) that nobody knew about them. The supervisor had to carefully watch and tell his superiors about any deviation by any worker. The ultimate superiors were the “Politruk” [political ideology officer] nominated by the [Communist] party's secretary, Prokoror [prosecutor], or an NKVD official. Every place of work had a Politruk attached to it who was tasked with conducting ideology discussions, teaching the constitution and Stalin and Lenin's writings, and most importantly, investigating the attitude and loyalty of every worker, particularly of the management, to the new regime.

A “Red Corner” was allocated at every place of work – a “holy” place where the pictures of the “Big Four” - Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin - hung. A worker assembly gathered every week in every place of work to discuss work affairs, improvements, and praises or condemnations of workers. Workers had to arrive to work promptly on time. Lateness of three to five minutes or more resulted in an official condemnation at the worker assembly. After the third incident, the worker would be handed over to the court, facing a punishment of three to six months of forced labor and a deduction of 35% from the salary. A tardiness of twenty minutes or more was handed over to the court on the first offense. If a worker was late while serving the prior sentence, he would be sentenced to five to ten years in jail and deportation to Siberia.

The work itself was not that hard, but the responsibility was not only your own work but the work of others. You would be at fault if you knew about a “condemning” detail and did not timely report to the supervisor, Prokoror, or NKVD. Under that atmosphere, people began to suspect and fear others. You never knew to whom you were talking, although you have known that person for a long time. Even if you were a friend of a specific individual until the war began, you did not know the nature of that person after the war. We got used to this life slowly and with difficulties. Social and cultural life ceased to exist. People met only at work or in gatherings under a cloud of suspicion and doubt. The synagogues were full of refugees, and public praying was done in secret,

[Page 101]

in private locations. Schools for children up to the age of 12 were opened for the entire population free of tuition. Initially, there was also a school where the teaching language was Yiddish, but it closed after the first academic year.

The library closed, and our books disappeared. It was forbidden to borrow books, and so were other areas of our cultural life. Nothing remained from the drama club or soccer team, let alone the activity of the youth movement. Our life became similar to life in Russia. People were forbidden to think since thinking was done for them by their superiors and people in the “high places.” Everything was done on command, according to a preplanned program, prepared and written in advance. An individual was just a tiny screw in a big machine. One should not have stood in the middle to think or ask. We learned to shut up.

The ruling language was Russian, and the secondary language was Ukrainian. Medical services were free for the entire population. There was one large polyclinic [providing general and specialist services] for the whole city and its surrounding. The hospital served everybody free of charge.

We were associated with the Ternopil District, and the district received instructions from Kyiv. Several physicians and nurses arrived from Russia, but there was a shortage of nurses nevertheless. We conducted courses for practical nurses at the hospital. Some practical nurses survived WW II since they enlisted in the Red Army at the beginning of the war (some reside today in Israel).

The court was at the hands of the Soviets, while the NKVD was in charge of security, and we all were under the supervision and management of the party headed by the first and second secretaries. Our communists could not join the party since the Soviets did not trust them, and to join, one had to be a “candidate” for five years. Some local communists were jailed immediately upon the arrival of the Soviet communists because their friends in the movement snitched on them that they were Trotskyists. We have not heard about or seen them since. Among the arrested people was one of our unaffiliated people, Dr. Pomerantz, but he was released after three months in jail.

As aforementioned, the economic situation was terrible. The salary was small, hardly sufficient to buy bread with some tiny extra. However, finding bread was difficult. Sometimes the Soviets handed out sugar or another staple in the stores. The Soviets were against lines since a line meant “a shortage”, and those existed only in the capitalist countries. The truth should be told that the Soviet regime wanted to prevent the formation of lines so that people would not waste their precious time. So, they would suddenly announce that a specific product is available in the stores. The result was an onslaught on the stores, and the inventory was gone within several minutes. There was not much of it in the store. Most of what had been supplied was hidden away and was later sold on the black market.

The artisans in their cooperatives worked mainly on repairs. There were almost no new works due to the shortage of raw materials. Some craftsmen had plenty of work – such as carpenters. There was sufficient wood in the warehouses and they worked for the government to make furniture for schools and offices. We had forests in our area, but it was almost impossible to find wood for heating. The farmers did not want to work in the forest, and when they agreed, it was under pressure and threats. However, there was nothing to transport the wood from the forest to the city. Everything was run by the government, and in the summer, special offices were established to handle the wood supply, but it would usually not arrive on time. There was no cash in circulation. All payments were made through checks from the state bank. The government owned the pharmacies, and medicines were provided for free. However, it was almost impossible to get them due to shortages. We had to order needed medical instruments for the polyclinic and hospitals but we never managed to buy the necessary equipment before the end of the year (because it was not available at the warehouse). Since we had to spend the money allocated in the budget for instruments before the end of the year,

[Page 102]

we bought what was available rather than what was needed.

Men between the ages of 18 and 50 were recruited. A substantial portion of our youth enlisted in the army (regular army) before the war and others during the first few days of the war. Some fell in battle, and some became prisoners of war. Only a relatively small portion survived.

In the winter of 1939, war broke out between Russia and Finland. That war lasted several months. Except for the gatherings, where the workers “demanded” that the government (on command from above) win over Finland, that war did not affect us. Nevertheless, we felt that something was wrong. We felt the tension and lack of trust between the Soviets and Germans. In the winter, a population exchange occurred between the Germans who resided in Soviet regions and the Soviets who lived in German areas. The Soviets got the people out of their homes during the most severe cold spell and transferred them beyond the border.

Formal holidays were celebrated twice a year – on the 1st of May and the 7th of November 7th – Revolution Day. The latter lasted three days: holiday's eve, the holiday itself, and the next day. During those days, candies and drinks were sold not far from the center of the celebration.

Under that atmosphere and regime, we spent a winter, summer, and additional winter. We got used to that life as though we were born with them – a life of fear and anxiety. The fear and danger increased with the type of job. The more important the position was, the more dangerous it was, and when something happened to you, you had neither a friend nor an ally. The opposite was true. Everybody distanced themselves from you to show the authorities that they did not have any association with you. One of the NKVD officials advised me, once after I had treated him - “If you don't want any trouble, don't tell anybody, including your wife. You must remain silent.” Nevertheless, nobody knew if anybody wanted to take revenge and snitch on him.

On the 1st of May, a military parade took place as part of the holiday celebration. News that was heard on the radio was passed by word of mouth. It was reported that four German divisions entered Finland. We knew then that a war with Germany was unavoidable, that it was approaching, and we did not have the means to defend against it or to escape. We could not even store food for a time of need. We knew that we would be annihilated if the war was to break out. We did not believe that Russia could withstand a war.

And the war broke out! It erupted more forcefully, speedily, and cruelly than we anticipated. That time too, the war broke out suddenly. On the night of 22nd of June 1941, at 2:30 in the morning, German planes began bombing cities and airports and caused enormous destruction. It was the night between Saturday and Sunday. We heard what happened on the radio early in the morning. The initial news was disappointing. Despair and panic broke out as forcefully or greater than the first time.

Our city suffered mentally as well as losses of life and property. Part of our youth enlisted in the Soviet army before the Germans conquered the city. Part of the Jewish population who were publicly active during the Soviet regime escaped on foot, trains, or wagons eastward to Russia. The majority stayed behind. The Germans advanced on all fronts. The retreat of the Soviets was more organized, with no yelling. The Soviets had a place to escape to.

Two airplanes approached on the 28th of June around 4:30 and 5:00 pm, lowered down, and encircled the city twice. We didn't think that they came to bomb the city. Before we had the chance to realize it, the planes dropped some regular and incendiary bombs.

[Page 103]

The first bombing demolished the Polish Workers' House. The rest of the bombs hit the Jewish quarter, the houses were decimated on Zbozuva Street, and there were many victims. Fires broke out in several other locations in the city. That was the first bombing attack, and it caused panic. People became confused and ran in the streets in different directions without order or plan. Only a few – mostly families of the victims, began to clear the ruins and search for survivors.

My parents' home was among the demolished houses. We succeeded in pulling out eight survivors in a few minutes. The hour was close to eight o'clock in the evening. The Soviet army demanded that we leave the place and enter our homes by imposing a curfew from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. We returned to the rescue work only at 5 a.m. After a substantial effort, we pulled out the bodies of my family members with other bodies. We covered them with sheets and brought them to the cemetery.

We dug the graves with our own hands and brought them to a Jewish burial. German planes circled above the entire time and dropped bombs on the Jewish quarter. There was a short break toward the evening but the airplanes returned and continued to bomb more forcibly and vigorously, particularly the Jewish quarter, two hours later. People ran out to the fields surrounding the city. They suffered some hits, although nobody was killed there. There was total destruction in the city.

The Soviets left on the 30th of June, and a day later, on Tuesday, the 1st of July, the Germans entered our city. At first - motorcycles, then tanks. Our city was conquered without any resistance except for a short battle that commenced near the dam, where several Germans were killed.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Berezhany, Ukraine

Berezhany, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 15 Oct 2023 by JH