|

|

|

[Page 232]

By Menakhem Katz

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

The Beit HaMidrash, named after Rabbi Yudel, was located on the northern edge of the Jewish neighborhood on the crossroad of the roads from Ternopil and Lviv. Rabbi Yudel was a Tzadik who resided in the city. He died in 5568 (1808). The Yahrzeit [anniversary of passing] was observed annually by visiting the grave and a having Mitzvah meal.

According to the literature, there was no other house of prayer like it in the city. There were two types of synagogues in some Eastern European cities and towns: the first was called a synagogue, and the second was utilized not only for praying but also for public and private studying of the Torah. The latter was called “Beit Midrash.” The “Beit HaMidrash” named after Rabbi Yudel had other roles. Before we review them, I will describe the building's physical structure.

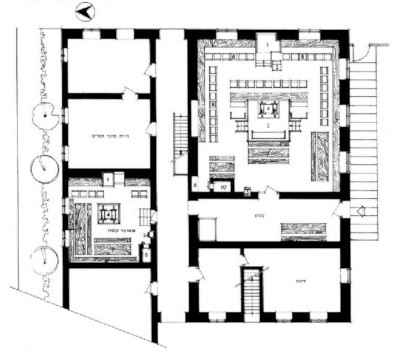

The main building of the “Beit HaMidrash” stood on the corner of the Tarnopolska and Lvovska streets on a spacious plot, surrounded by some auxiliary structures. The Beit HaMidrash was a square building like many other houses of prayer built in Poland in the 18th and 18th centuries. Unlike other synagogues with all sorts of arches, the ceiling of Rabbi Yudel's synagogue was flat and supported by wooden beams, as customary in other buildings in the city. The roof was covered with wooden shingles, replaced with a tin roof in the late years. The ceiling was made of plaster and decorated with spectacular pictures of the Four Beasts [from Prophet Daniel's vision of the four beasts].

When you entered the hall, opposite a simple and long wooden table, your eyes would meet a metal grate made by a tinsmith and decorated with heavy brass balls, which together formed the railing of the Bimah (raised stage - “Belemer” as the people in Yiddish called it). Above the Bimah's rail and through the thicket of rods and the hanging lamp chains, your eyes were attracted to the central part of the prayer hall – the eastern wall and the Holy Ark in its center. The Holy Ark, made of carved wood, was crafted by a Jewish artisan.

In 1936, the ceiling was replaced due to the risk of collapse. The decorations on the new ceiling were four plaster reliefs in the shape of a Star of David cast in the corners and a single Star of David relief in the center. Balls made of plaster were placed on the four sides of the ceiling between the Star of David's reliefs. A glass ball hanging from each of these balls contained an electrical lamp. Multi-branched copper menorahs on chains descended from the center of the Star of David reliefs. The menorahs were donated by the generous worshipper, Khaim Perlmutter. A thorough renovation was also performed in the same year. The floor and the windows were replaced, and many renovation projects were performed under the supervision of the Gabbai, Yitzkhak (Itzi), son of Menakhem David.

The building of the Beit HaMidrash, whose exterior was monolithic with a four-slope roof, was a collection of rooms with various purposes. The prayer hall, which measured a square of nine meters on each side, occupied most of the area. The Bimah was positioned in the middle. Attached to the western side of the prayer hall was a long entrance hallway, two and a half meters wide. The main entrance to it was on its southern side. On the opposite northern side of the hallway, an additional door led to a dim, long, narrow corridor, which connected a whole row of auxiliary rooms.

A wide double door led from the center of the entrance hallway to the prayer hall. On its northern edge, close to the exit door, stood a cabinet for Torah books Psulim [non-Kosher, invalid]. Above it was a Gnizah cabinet [for temporary storage of books designated for a burial].

[Page 233]

The Holy Ark was situated on the eastern wall. A canopy with a pseudo-classic frieze above two small columns formed an open space above the ceiling of the Holy Ark. Above the frieze were two lions' figures with the Two Tablets of the Covenant. Behind them, on the two sides, were two large birds. The whole complex seemed to be made as a single piece – an engraved wooden structure whose spaces and protrusions, arranged in a rich configuration, complement its artistic appearance. Integrated into the holy Ark were the lights, shadows, and colors – red, green, blue, and gold - in a harmony that conveyed splendor.

|

|

[Page 234]

The artisan who created the Holy Ark was R' Meir-Hersh Shapira Z”L, a pious and learned man, the Mohel of the town. I recall the admiration for that artisan I heard from my grandmother, who loved decorative objects. He created this masterpiece with his knives and rich imagination. Delicate leaves on thin copper wires, interwoven among pears, apples, and other fruits, rose and climbed on the side of the Ark. In the center of the Ark were two narrow doors made of delicate lace craft, with a small half-circle roof above to shield them.

Indeed. The Holy Ark was beautiful – a pure Jewish work of art. Reverence befell anybody who stood before it.

Two big windows topped by round arches were on the two sides of the Holy Ark. They cast an abundance of eastern light onto the prayer hall. Adjoining them was a half-circle hatch above the Holy Ark and a row of windows on the southern wall. There was no lack of light in the Beit HaMidrash, even on days without sun since its windows faced the south with a spacious entrance yard behind them.

Three stone stairs led to the Bimah, where a wide table stood on the east and a heavy oak bench on the west. On the left side of the table was a tall chair for the person overseeing the Torah reading – R' Mikhael Redlikh Z”L.

Rows of “Shtanders” (prayer stands) were available for all seats, which encircled the Bimah from three sides. Long tables made of simple wood stood behind them. Close to the entrance, within an indentation, stood a cooper sink and a tap, and close to it, a towel hung on a roller.

An old clock, the eternal light, and a book cabinet were placed above the fireplace.

From the prayer hall through the entrance hall and into the dim corridor were two treacherous stairs that were obstructive to any stranger who did not know about them. A clay floor in the corridor led to a room of prayer, which was used as a “Kheder” called “Potiker Kloiz” for teaching little children.

Attached to the Potiker Kloiz on its east side was a two-room apartment for the “Sofer St'm” [scribe], and on the west side three additional rooms, the apartment of my rabbi-teacher and Kheder Melmamed, R' Getzeleh Halperin and behind it, the apartment of the Gabbai [Torah reading administrator], R' Yosef Shtreizand. Behind the entrance hall were two additional rooms, and in the middle, a staircase leading to the outside and the women's section on the upper floor.

The women's section spread over the lower rooms. There were rows of benches with backs there and “Shtanders” (prayer stands), as in the men's section.

In addition to the main building, the “Beit HaMidrash” owned a spacious structure with a separate interior yard, which was leased to R' Yosef Shtreizand. With the entrance of the Nazi oppressor, R' Shimshon Fogelman buried in this structure in a deep pit (according to him), all the “Klei HaKodesh” [ritual objects] of the Beit HaMidrash.

In the yard, which was agriculturally cultivated, a row of ornamental trees shaded a row of sitting benches. A kiosk, which people in the town called “de ginishe budkeh” (the green kiosk) stood in the yard. The Beit HaMidrash also benefited from the lease it received from the renters of the auxiliary buildings.

|

|

[Page 235]

Characters

The lifestyle of the Beit HaMidrash was reflected in its people. I cannot describe the entire crowd of homeowners, estimated to have been more than one hundred families, who were permanent members of the Beit HaMidrash and constituted most of the audience during the holidays. However, I will expand here on those whose personalities, roles, or appearance made their mark and shaped the character of the Beit HaMidrash.

First, I would mention some dignitaries:

Rabbi Moshe, the city rabbinical judge, possessed general education and inexhaustible knowledge of the Torah. For many years, Rabbi Moshe made a living from his real-estate business since he did not want to depend on public money. He also used to teach adults and the youth for free. His short stature, white beard, and slow and calculated moves invoked respect and appreciation from anybody he met, beginning with the children of the Kheder and ending with the community elders.

Behind him [in the hall of prayer], we should mention R' Efraim Zalman Margaliot, the grandson of the Rabbi from Brody and the author of the book “Yad Efreim” [The Hand of Efraim]. He was a Talmid Khakham [literally “a student of sages,” an honorific for somebody who is versed in Jewish Torah, literature, and law], a pious and modest man. A separate article in the book [see page 204] is dedicated to him.

Near him sat R' Yosef Shaul Weichert, also a “Talmid Khakaham,” one of few in town. He was very clever and had a majestic appearance. He served as a deciding arbitrator in feuds and negotiations.

We should also mention the Gabbais, such as R' David-Meir Freier, a wealthy merchant with a majestic appearance, who was one of the Enlighted, but he also attended the Beit HaMidrash diligently. His golden glasses, calculated moves, and self-confidence did not prevent him from being a public servant and influential and respected Gabbai.

His neighbor on the east side seat was R' Shimshon Fogelman – the mighty synagogue administrator. He served as such for many years. He was a pious Jew who, in addition to his work, dedicated most of his free, and not so free, time to public activism as a Gabbai, initiator of charity events, and an enthusiastic Zionist. He was the one that enabled Zionist activities at the Beit HaMidrash. We should give him credit for all the gatherings, Zionist speeches, fundraising for the KKL-JNF, Keren HaYesod [United Israel Appeal], and other Zionist causes.

And who can forget the sturdy figure of R' Yosef Shtreizand? His nickname was Yosi Stoller (carpenter in Yiddish), according to his profession. He was a homeowner, a diligent Gabbai, a gatekeeper, and an administrator. He was a man of many actions when it came to charity organizations and served as the chairman of “Khevre Kadisha” [burial society]. His firm stance, energy, and public activism earned him respect as a man of action. He was imbued with the Zionist spirit and made Aliyah to Eretz Israel. He settled in Kfar Saba and continued to be one of the activists for the working religious public.

Every figure with its own characteristics – the dignified homeowners, people with a unique nickname, or others with a regular surname, from the simple people to the local or passer-by poor people - everyone was accommodated at the Beit Hamidrash.

In the corner, between the eternal light and the fireplace – was something that looked like a pile of tattered clothing or perhaps a folded blanket forgotten between the benches. That was the impression of anybody who was not a member of the Beit HaMidrash. However, that impression would evoke a smile

[Page 237]

on the face of every child and adult. For them, it was clear that the neglected pile was the sleeping figure of the hunchbacked scribe. The poor Sofer St”m, whose stature was not much taller than the prayer stand. The scribe was sitting there days and, nights, during the hot summer days, and the long winter nights, writing Mezuzas and Tefillin. The bench at the fireplace was his place of work. He sat there, worked, managed his business, and conducted whispered negotiations with his few clients who stopped there from time to time. This colorful figure had no home and no friends. The wooden bench, holy books, and the happenings at Beit HaMidrash were his only world.

Life in Beit HaMidrash

As aforementioned, in addition to the prayers, the roles of the Beit Hamidrash were many. First, I would like to mention that Beit Hamidrash was open day and night. Its gates were almost always open.

Before sunrise, on a bright sunny day, or during a snowstorm, one could observe the short and brisk steps of R' Gedalia Rozentzweig, the caretaker, hurrying to his place of work. He quickly reaches out with his hand over the upper door lintel, searching for the key in its hiding place, known to all the regular members. The key was always in its place. He takes the key down and puts it into the keyhole. However, before twisting it to unlock the door, he tries to see if the door has already been opened. Rare were the cases in which R' Gedalia had to unlock the door with the key. There was always somebody who came before him.

Who were the early risers? They were homeowners in a hurry to leave the city on their business with the sunset, people who studied the Torah and Mishnah, passers-by, those who carried packages from other towns, those who needed to say “Kadish” or on a Yahrzeit in a hurry for the first Minyan and just wondering poor, and “ragtag's and bobtails” who were always familiar with the customs at the Beit HaMidrash.

One scene of many that took place every day – before dawn, not quite a night anymore, but still not a day, within a bluish dim, penetrating through the windows, your eyes adapt to the grayish light, seeded by some lonely golden dots of candles here and there. Every candle has a figure close to it of a Jew covered with the Talit, whispering his prayers quickly. Another figure moves quickly, rolling up a sleeve and tying the Tefillin stripes on his arm. Somebody moves the prayer stand and takes out the Klei HaKodesh. In another corner, people whisper to each other. These are the poor who spent the whole night near the cooling fireplace. Everything moves slowly and mysteriously. Before the arrival of R' Gedalia, no palpable activity occurred in Beit HaMidrash. When his diminutive figure appears at the door, it is as if a spirit of new daily life blows through everything. He makes his first steps

[Page 237]

toward the Bimah's table and takes out a handful of candles locked in the cabinet below. The candles are quickly distributed among the people at the synagogue, and they are lit one after the other. He does not begin his daily work alone. His helpers are many, some willing and some are not, since they all need his favors, a poor person, or a dignified homeowner. One person needs another candle, the other an accommodation license, and the third one forgot the key to his “Shtander” and is asking to lend him Tefillin. As he is hard of hearing, R' Gedalia divides the tasks without using many words. The fireplace and candles are lit, the sink is filled with water, the floor is swept, and the Beit HaMidrash is ready to receive its members.

|

With the arrival of the tenth person, they don't wait for another since the time is precious for the early risers. “Begin,” hints one initiative person who is in a hurry. “Wait,” answers his neighbor, “It is still dark outside.” A hot debate arises occasionally, whether it is permissible to begin the morning prayer or they should wait a short while. The minutes pass quickly, and the Ba'al Tfila [the prayer leader] approaches the lighted stand and begins. Almost immediately, the phrases start to flow from the prayer stand. From time to time, additional people who come “late,” join the first Minyan.

After the end of the prayer, everyone is joyful, particularly the poor. Almost every morning, there is at least one homeowner who needs to fulfill the commandment of a “Yahrtzeit.” A mandatory custom is that the mourner sponsors a “Tikkun” [literally ‘rectification,’ breakfast after the morning prayer. Mourner are generous or not, but all dispense a small cup of wine among the attendees. Depending on the mourner's financial situation, cookies, beigels, or dry pastries are also provided. Standing, while folding the Tallit, the praying people grab a sip and light bite, and each hurry up on their way. For the poor people, that is the day's first meal, and they are waiting for it, impatiently. They take as much as possible. R' Gedalia makes sure that the food is distributed equitably. That is why his standing among the poor people is so strong. During the economic crisis, R' Shimshon Fogelman established a custom, in which the mourners donate money instead of “Tikkun's” food. With that money, bread was bought and distributed to the needy according to a list prepared by the Gabbais.

One Minyan after the other is held without a break throughout the morning. The “Ba'al Tfila” changes for each Minyan. Often, the number of Minyans reaches ten in one morning. The last Minyan concludes around 11 A.M.

Saturday afternoon – the prayer hall is full. A diversified crowd from all classes of the city population. The Bimah is surrounded by youths, and behind them, the homeowners, Hassidim, and Zionists of all shades of Hasidism and Zionism. At the center of the Bimah stands Rabbi Shores[?] – a professional preacher and a follower of “Agudat Israel” [the Haredi Jewish party]. Moral aphorisms with a political background spill from his mouth like blazing flames. The exuberant sermon fascinates the listeners – his supporters and the Zionist rivals. However, he peppers his remarks with incitement against Zionism, Aliyah, and the modern education of the youth.

At that point, after captivating the audience with words of Torah, admonition, and persuasion, the first statement of hatred against Zionism is heard, and the listening barrier is breached. A young and tall youth, Moshe Bergman, the leader of the Zionist youth movement in the city, vigorously utters the first dissent.

That call, presented as a question, forces the preacher to respond or embarrasses him, and he stops his enthusiastic speech. Questions and answers float in the air, and the voices of opponents and allies are heard. A debate between the speaker and the crowd ensues. Beit HaMidrash becomes a definite political stage that does not require the involvement of organizers. The questions and interjection calls are spontaneous,

[Page 238]

from the bottom of the hearts of the Zionist youths, fighting for the right to be Zionist among their people with all its shades of religious and secular views. That was a relevant debate between the young generation and the establishment consisting of homeowners, pious Hassidim, and just regular Jews. That was the atmosphere in the afternoon on Sabbath or a weekday (usually Sunday). That was just another folk episode at the Beit HaMidrash when the Zionists fought for free Aliyah from inside of the nation and those layers who became an inhibiting factor and a stumbling block to the Zionist effort.

Skipping over gatherings, religious-political speeches, state or community election gatherings, comedy shows, or simply small talks, I reach a story about a slightly strange night gathering. The space of the prayer hall was lit only by a few candles. A group of young men, before the age of enlistment, gathers and conduct their discussion in a whisper. They talk about this and that, just debating, exchanging political views, interjecting jokes, gossiping about the relations between a certain man and a woman, and so on. The discussion stops, and another figure joins them. A couple of young men leave the synagogue, just to return to it a short while later. Who are these young men who patiently spend the hours of the night with talks, torturing themselves not to sleep? People call them the “tortured.” They deplete their strength by not eating or sleeping to lose weight below the minimum acceptable to the Austrian or Polish militaries.

Two figures whispering a secret to each other. One of them is a passer-by – a professional beggar who talks about his adventures and achievements to his friend who is also a professional beggar. These people meet occasionally throughout the state, and Yudel's Beit HaMidrash is one of their regular stops. That is where the beggars meet and renew acquaintances, a tradition practiced for generations.

During the late period, a rule was introduced that forbade the Jews from begging. Instead, the community provided a uniform allowance and lodging to all foreign beggars to prevent them from going around in the streets. The bench by the fireplace served as a temporary stop for those who intended to stay in the city temporarily.

That corner was also where news was being told.

|

[Page 239]

What could you hear at that corner? You would learn about the movement of ‘ragtag and bobtails’ throughout the entire state and about the large amount of money collected by professional beggars. You could also hear who among the beggars owns a house in one town or another, and who is a dignified homeowner in his far-flung town at the edge of Poland, spending only the summer to beg for money as a profitable “profession.” You could learn what preachers plan to come to town soon and even what has occurred in the synagogues at the sermons. You will hear about quarrels between rabbis at the courts of the Admo”rs, exaggerated stories, miracles performed by rabbis for their followers, and famous matchmakings between dignities and rabbis. News was told there, not only about the happenings within the Haredi world but also about the international prices of currencies in which the bench-sitters were experts. You would also listen to political debates on a reasonable level since knowledgeable and clever people are occasionally sucked into that debate corner. In summary – the table at the fireplace served as an updated means of communication those days.

A woman's plea

It was a bright summer morning. The prayer hall was awash with sunlight when two Minyans were immersed in a late morning prayer. I stood, along with the rest of the worshippers, not far from the Holy Ark with the calm of a youngster without worries, I delved into the holiness of the prayer. Suddenly, without seeing how and where from, a woman wrapped in black burst into the hall with her hands lifted, covered herself with her black transparent scarf, and like floating in the air, stretched out in front of the Holy Ark.

“Is it a ghost or a dream I am dreaming? A woman in black in the men's section during the morning prayer? . Impossible! Nevertheless, my eyes do not mislead me.” Only a few seconds of passing thoughts behind me, and the figure removes the Holy Ark's “Parokhet” [curtain] and opens the doors. Her knees drop to the floor, she stretches her arms toward the open Ark, and a scream of terror emanates from her throat: “Shema Israel…My G-d, my G-d, help me, what was my sin before you? Please do not take my son from me - he is so young.” And again: “Shema Israel…” combined with a scream, sob, and a cry of pain, echoing among the walls of the synagogue.

That episode lasted only a few seconds. After the first scream, and after the shocked and astonished crowd grasped what had just happened, two men hurried to the Holy Ark, lifted the woman, and locked the doors. She was the wife of Abba, the ritual slaughter, and it was not easy to lift her from the front of the Holy Ark. Words of persuasion and pleading were leveled at her to leave the place. Dignitaries intervened, but the woman persisted – and continued to extend her plea through pain and sorrow.

Long times passed before the worshippers convinced the sorrowful woman to leave the praying hall. The impression that episode left upon the small praying crowd and the echoes of the event continued to reverberate for a long time.

That scene of breaching the customs by a Jewish woman, the pious wife of the ritual slaughterer, symbolizes boundless fate in a divine force whose sanctuary and manifestation was the Holy Ark and the approach to it was through the open doors of the Ark.

All of that occurred at the Beit HaMidrash, named after Rabbi Yudel, which served its worshippers for various purposes in the social and spiritual life of the town.

[Page 240]

The evening before Yom Kippur

The “Days of Awe” is an expression conveyed as a concept during the rest of the year. You express that concept as part of volubility and move on. During the month of Elul, it is not an expression or concept. During that month the Days of Awe become a symbol, divine words, which exert superhuman fear in you. They become days of preparation, days of asking for forgiveness and repentance, pray, and fear the day of atonement, the holy and divine day. Thoughts about that holy day would not leave you alone during the entire period approaching the critical prayers on Yom Kippur. The closer the big day, your pleas and prayers deepened. Prayers, asking for forgiveness, repentance, ritual immersion, confession and repentance, cleanliness of the body and soul - all of these are the preparations for that day.

The evening before one specific Yom Kippur at the Beit HaMidrash, one of many in generations, was etched in my memory.

The prayer hall at Beit HaMidrash is clean, its walls are gleaming from the whitewashing, and the copper objects shine, reflecting the sun rays that penetrate the space, inducing shining spots to dance on the white background of the walls like stars. It is late afternoon, and the entrance hall gates are wide open. The long table is covered with white paper and all sorts of boxes and bowls are on it. There is a note on each one of them, stating who would be benefiting from your donation. Tens of boxes for the fund of Rabbi Meir Ba'al HaNes. There are also boxes for the KKL-JNF, and the elderly shelter in town – all arranged in a row waiting for their donors.

The homeowners are flocking to the bowls. It is a custom to donate to charity and pay off debts at dusk between Minkha [afternoon prayer] and Kol Nidrei [a prayer recited before the evening prayer of Yom Kippur Eve.]. The worshippers are coming at a slow flow starting in the afternoon hours, walking along the length of the table, each man, and his donation. The metal coins strike the metal, and the return tone symbolizes the gratitude of the institution. The Gabbai sits at the head of the table and collects the year's debt payments from everybody. The long list of debts, oaths, obligations, and donations is getting smaller and smaller. That is the time for paying off the debts, and the Jewish hearts are open to charity since the time is running out, and it is going to be too late in a few hours. And thus, without any words of solicitation, the boxes are being filled with donations.

When you pass from the entrance hall into the praying hall – a holy spirit grips you. This is not the Beit HaMidrash of the regular days. These are not the same walls, not the same Klei HaKodesh, and not even the same people. These are different people – the Jews of the Yom Kippur's Eve. They look different from their daily looks. Every figure and every shadow, familiar to you from the other days of the year – they are different on the evening of this holiday. People are different in their looks, behavior, cleanliness, and exultance before the big prayer.

And here is a picture, one of the few that may still be seen in a secluded alley in Mea-Shearim [old Jerusalem Haredi neighborhood] or Hasidic Williamsburg [in Brooklyn, New York]. The bent figure of R' Mikhael Redlikh, a very old G-d fearing man whom young and old paid respect to unreservedly, rose from his seat on the east, and with prudent steps approached the Bimah. The wise man was frail, as the years weighed heavily on him. However, when he approached the Bimah steps, he was suddenly granted youthful strength and with swift steps, he climbed onto the Bimah. Hinting with his arm, he called R' Gedalia, the caretaker. Without saying a word, R' Gedalia unrolled a small carpet on the Bimah's floor. With a slow bending motion, R' Michael got down on his knees

[Page 241]

and slowly tilted his body forward until the palms of his hands touched the carpet. The old man's slender body knelt on all fours, and his back arched upwards. With a quick hand, R' Gedalia pulled out a braided whip with long stripes and brought it down on the old man's back at a steady pace[1]. Raise and lower – raise and lower – the whip hit the back of R' Mikhael. Every hit yielded a dull echo. Occasionally, between one lash to another, you could hear R' Mikhael whisper: “Harder! Harder!” and R' Gedalia slightly increased the swing of the whip only to retreat again in his following lash. The caretaker whipped forty lashes on the back of the old man.

The custom of flogging was over and done with. R' Mikhael rose on his feet, and his face brightened since his last preparation for Yom Kippur's Kol Nidrei prayer concluded. He was ready to worship his G-d on the Day of the Atonement.

A few other community elders passed under R' Gedalia's whip. And when the time for the “Se'uda Mafseket” [the last meal before Yom Kippur's fast] approached, the Beit HaMidrash emptied out. Only a few hundred Yahrzeit candles remained. They were made in white or dark shades of yellow colors and in shape, starting from a small tin box to sophisticated raided wax candles. They all made golden lights dance and in the silence of their dance, waited for the crowd of Kol Nidrei prayers.

|

Translator's Note:

by Menakhem son of Shimon Katz

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

A school stood close to the Great Synagogue. It was a structure made of dirt that contained two rooms. A Jewish Melamed or teacher lived in one of the rooms. The second room was like a synagogue. It means that it had the Holy Ark and a fireplace made of burnt bricks and covered with green enamel.

That is the description of Beit HaMidrash from the documents of the Roman-Catholic community in Brzezany from 1939. That meager structure was rebuilt from stone. That was the source of its name – “The ‘Built’ Beit HaMidrash.”

That is also how I remember that unique architectural asset, a remnant of the 17th century, a member of the family of Galitsia's synagogues relying on four supporting pillars. It was built from plastered sandstone, which could only be seen on the rim and the doors' lintels.

Beit HaMidrash stood in the southeastern corner of the synagogue plaza, like kissing the northeastern corner of the Great Synagogue, leaving only a narrow pass between them.

The structure was square with nine “fields” of cross-like domes, the center one of which was supported by four heavy support pillars. Four arches connected the pillars, and eight additional arches connected the corners of the domes to the outside walls. The four support pillars, together with the twelve arches, formed a massive structure that provided the inner space of the building with a character of strength, evoking a feeling of security. It seems that this constructive aspect was not the only consideration that drove the builder (probably Jewish, as there were such builders in town at that time) to choose this design with four support pillars since our area did not have good building stones, but the Brzezany area was rich in forests, so it was much more logical to cover the hall space with a wooden ceiling. It seems that the emotional consideration of providing the worshippers with a sense of security was a considerable factor in the design of that Beit HaMidrash.

[Pages 243]

|

|

|

|

|

|

of the “Built” Beit Hamidrash |

On the side of the main entrance, another door led to a steep staircase rising up to the women's section, which occupied the area above the entrance hall on the second floor. The southern side of the women's section was open to the main hall, and only a short heavy metal railing made by a tinsmith separated the section and the main hall. The heavy construction of the domes was topped by a flat ceiling, and above it was a tin roof laid on top of a wooden grille as customary in other structures in the city. Based on the construction of the arches, it is logical to assume the tin roof was added only recently and that originally, the synagogue could have served as a fort with a tall railing on the roof, as customary in the other fort-like synagogue in eastern Poland.

Stone staircases between the support pillars led onto the Bimah from its southern and northern sides. The Torah reading table stood on the Bimah. It was surrounded by an iron railing – the work of an artistic tinsmith. Muli-branched copper menorahs hung on an iron chain descended from the center of each dome. The large number of the menorahs was more than enough to light up the prayer hall. However, when gas-lighting became available in the city, the “Built” Beit HaMidrash became the only synagogue lit by gas.

Most worshippers at the ‘Built’ Beit HaMidrash were middle-class and wealthy homeowners. Despite its name, people prayed in it only on Shabbat and holidays.

The gabbais of the Beit HaMidrash included Ya'akov Bauer, Mendel Fridman, Ya'akov Katz, Ya'akov Kaner, Ya'akov Shtern, and Eizner.

The building, except the furnishings, was preserved through the Soviet and Nazi conquest periods. When I left Brzezany, it served as a wheat warehouse for the Soviet supply authorities.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Berezhany, Ukraine

Berezhany, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 26 Nov 2023 by JH