|

|

|

[Page 2]

Yaakov Lifshitz z”l

The introductory words to this booklet were written by Yaakov, the man who initiated the idea to publish the booklet, and brought it to fruition. Fortunately, this publication includes the memory of this unbelievably energetic man with a warm heart.

It is difficult to eulogize our chairman; a pioneer, who left a founding family in our town, and followed his sister Chassia as the first pioneer. Here, Like most members of the Third Aliya (immigration), he became a construction worker, a farmer, a security guard, a member and instructor in the Zionist defense system (Hagana), a dedicated worker at the ministry of security, who was from the founders and active members of Kfar Azar .Yaakov was involved in the welfare of the State, he sensed its needs, and above all he was a warm Jew, who loved his people and his land, ready to come to aid the community and every individual.

Yaakov was loved by all. To us, members of the Neishtot community, he was particularly dear. He was the one who kept the spark lit, in memory of our town that was destroyed.

Yaakov welcomed every refugee, upon his arrival in our land, ready to help. He did not need to be asked.

Until his last day, Yaakov remained young at heart, energetic, caring about the welfare of our country, and prepared to help and act on behalf of the individual.

His memory is engraved on our hearts forever.

A Monument to Our Town Neishtot

Dear fellow townsmen:After years of deliberation, we have finally come to the decision to publish memories of our town Neishtot, which was destroyed and ruined by Hitler's armed forces, during the (Shoah) Holocaust that befell European Jewry.

It is our intention to set up a monument in memory of our dear parents, brothers and sisters, who perished in the terrible tragedy that Hitler y”s brought upon our nation.

In these pages we wish to share a small scale of our memories of Neishtot / Tavrig, a small Jewish town. It was built with the typical character of the glamorous Lithuanian towns, of which sons and grandsons would be talking with pride. The place where their fathers and grandfathers were born, and is now gone.

We tried to collect some material from veterans who emerged from the town, and were fortunate to reach Eretz Yisrael in the era of immigrations. We also gathered information from World War II survivors who managed to go to Eretz Yisrael after the Holocaust. We are hereby presenting their notes and words.

We also considered including in these pages “Yizkor”, a memorial list of members of the town who perished in the Holocaust.

Due to time constraint and because of our fear of omitting some names of families that perished we were compelled to postpone the idea.

A considerable number of our fellow townsmen immigrated to Eretz Yisrael before the Holocaust. They immersed themselves in The State and took part in founding it, building and securing it.

When the refugees from our town arrived here, they were well received and were absorbed as brothers. Yitzchak Shavit / Shaveshevitz z”l, from our town, spearheaded a private absorption committee devoted to the newcomers. He helped many survivors, to get settled, find places to live, and find jobs. Yitzchak often used his personal money for this lofty cause. It is a great pity that he didn't live to see the fruit of his labor. He passed away at the prime in his life.

Blessed be his memory.

There is a small committee representing our community, who has undertaken to keep contact with our fellow town's people in Israel and abroad, to participate in their happy occasions and be there for them in time of sorrow.

We go up To Jerusalem every year on Holocaust Day, and commemorate the remembrance of our Kedoshim who perished in the Holocaust, using the chart, in the Holocaust Cellar, where the names are listed.

We have a modest account that was used for immigrants during their first steps into Israel. It also serves as an interest free loan account, for people from our town, in time of need. The money is kept at a bank.

Yaakov Lifshitz

By Rabbi Avraham Akiva Rudner z”l

Neishtot Holy Community

Neishtot / Sugint, was named Neishtot / Tavrig later, in the days of Independent Lithuania. The town was adjacent to the German border. Prior to World War I, there was a close relationship between this town and the German towns such as Memel and Tilsit.

It was very common for Jewish people and Germans to exchange business across the border. The Jewish merchants were dealing with horses, poultry, and agricultural produce, across the border, while importing various industrial products from there.

In our days, post Holocaust, it is difficult to imagine that the Jewish people were in such close contact with members of this murderous nation. It would certainly not enter anyone's mind that these Germans, or their sons, would be amongst the destroyers of the Jewish nation throughout Europe, with the Jews of Neishtot, their friends, included.

In those days, that are now far gone, Jews who crossed the border would adore the German's impressive order and polite manners. It was so superficial. They naively thought that they were sincere.

In fact, they appreciated the big difference between the town within the Russian border, which was muddy and covered with snow throughout most of the year, and the clean, paved, German villages. They saw the contrast between the rights and benefits that Jews enjoyed on the other side of the border, and their own deprivation.

All this however, did not impact their traditional lifestyle and their commitment to Torah and Mitzvot observance. The Jewish people of Neishtot did not lower themselves to the “cultured” non-Jews or to their fellow men across the border.

Although the number of citizens was small, Neishtot was not from the less fortunate of Lithuanians towns. The close proximity to the border was a reason for a relatively affluent population that included well to do businessmen, exporters, and other high class traders. This was noticeable in their dress mode, which was more orderly and clean, in comparison to people of the nearby towns. One would particularly notice it on Shabbat and Chagim (Holidays), when the town people would dress up and adorn themselves in honor of the day. Needless to say, on Shabbat it was calm and quiet in the streets. Only on a rare occasion, a farmer's wagon, accidently there, would be seen.

The city itself was situated in a nice location. It was surrounded by a river and small woods, crowned by a meadow. After their rest on Shabbat and Holiday afternoons, the main street became a promenade. Yeshiva members, laymen and workers, young and old, all alike, came out to stroll in the neighborhood, especially in the warm summer days.

The internal life of this small community was particularly rich. Both spiritual and physical aspects were blended. Throughout the week, when people were busy working to support their large families, they never compromised on their Tefilah (Prayers) at the synagogue and their dedication to Torah study with others, in the evenings.

There were three synagogues in Neishtot: The Klause, where craftsmen, like tailors, hatters and shoemakers, attended services. With the large number of members there, the Klause became the social center. In addition to Services, the Klause served as a place for gatherings. There, they spent the evenings studying “Ain Yaakov”, discussing current matters, and organizing various social services for the community.

The second synagogue was the Bet Midrash. There, the businessmen who were mostly learned men would pray. In fact, there were numerous Minyanim, study groups, sitting in the Bet Midrash /study halls, in the evenings, learning diligently Talmud in depth.

There was a custom in the town that every businessman would take a Yeshiva student for a son ln law. On occasion, they would even invite some men from a distant Yeshiva in order to increase the light of Torah in their homes. The family would pride itself in its number of Torah learners. This was the reason for the many Torah scholars that gave the town its special image.

The relatively comfortable conditions enabled people to offer the son in law Kest, as they called it in those days. It means that the son in law ate at his father in law's table (was supported) for a number of years so that he could dedicate his time to studying Torah. They read and delved into Hebrew and Yiddish newspapers and books.

The third synagogue was the “Shul”. The Shul was mostly open in the summer because it was too cold there in the winter. This synagogue was the place where the Maskilim who were attracted to “Haskalah”, Enlightement, gathered. They were interested in reading books and newspapers in Hebrew and Yiddish.

Despite the differences, everything in the town was run strictly according to the well rooted tradition. Everyone was Mitzvot observant and there were no violations. There was no spirit of zealotry. Every Yeshiva man looked at the newspaper and knew what is happening in the big world and in the Jewish world, though the newspapers arrived late in those days. In addition to Torah study, mentioned above, the assistance and kindness was strongly developed in the community. There was an organization called Linat Tzedek, whose members took care of sick patients and slept at their homes at night. There was also Bikur Cholim, visiting the sick, Gemilut Chassadim and other groups. These organizations assisted anyone who needed help and made sure that there would not be someone needing bread, food, or clothing. Clearly, everyone learned in the Cheder and Talmud Torah. The girls too had a special teacher.

The young men in the community were organized at “Tiferet Bachurim”, a committee set up to ensure that people will study Torah and be involved in community and public affairs at the same time. From the onset of Zionism, everyone was peaceful and calm. There was common respect for all, with no disharmony amongst people.

The rabbinical leadership in Neishtot consisted of famous rabbis whose reputation was widespread among the surrounding towns. This was a community of “Mitnagdim” (non Chassidic Jews), but unlike the common assumption, they were not cold and stiff. Most people were warm hearted, with fine character traits. They knew how to rejoice on happy occasions such as Bar Mitzvah celebrations; weddings, that were celebrated glamorously with song and dance, accompanied by the local orchestra; Brit Milah; or in honor of a Siyum, celebrating a completion of studying a tractate in the Talmud. On Simchat Torah and Purim when the whole town was, naturally, rejoicing as it is said “The Jews were rejoicing together”, one would feel the unity of “All Israel are friends”.

It is noteworthy that throughout all its' years, the town never knew riots or disturbances against the Jewish citizens. They were able to live and develop a community where the light of the Torah was shining. . There were people who were workers and traders. Families from Neishtot branched off to other continents such as America and Africa. The first immigrant to South Africa was Sammy Marks from Neishtot who was the pioneer of Lithuanian Jews' immigration to South Africa. The city atmosphere spread to those who left it too. The people held on to its spirituality and maintained close relationships with their families.

With the outbreak of the World War I, the thriving lifestyle at Neishtot, a city adjacent to the border, came to a halt. The town was hit from the very beginning of the war from the Germans' bombing and burning. Many of the people scattered throughout Russia.

After the war, they tried to rehabilitate the town but it took a new form. The social makeup of a harmonious society, that was the shining character of Neishtot, came apart, and was replaced by rival groups, youth, that distanced themselves from their tradition, and people were leaving town. One may note that many of them were pioneers who were part of the Aliyah Hashlishit, The Third Immigration to Israel. Others followed suit later and today there are many former Neishtot Jews who live in Israel and who helped build it.

Neishtot was erased off the map as a Jewish town along with many towns that were swept away during the Holocaust.

May this booklet be a monument in memory of a holy and distinguished community.

By Chassia Adar Lifshitz, Ein Charod

Our town was in close proximity to the German border, which impacted the economy of the city. The lifestyle was different from other Lithuanian towns. A number of Jewish families relocated to the other side of the border, yet continued to attend holiday services at our synagogues. We had three synagogues: The Shul, a glamorous structure, the Bet Midrash, a large wooden building, and the Klause. The spoken languages were German and Yiddish. Before World War I, when the city was ruled by the Russians, There were two Russian public schools. Most Jewish children did not attend those schools because they would have to attend school on Shabbat. The Jewish boys learned at the “Cheder”, and sons of wealthy families were sent to Yeshivot and gymnasiums (high school) in other cities. The girls studied in Yiddish and German in private schools.

The population was mostly well to do. They conducted business with Germany, exporting agricultural produce and importing produce that they purchased from the farmers in the neighborhood. There were relatively better shops and there was a good business relationship with the close Lithuanian neighborhood. Some of the citizens were craftsmen who struggled to support their families. There were areas where assistance was necessary and committees were set up to come to their assistance. The youth was very dedicated to lend a hand. I personally fulfilled my duty by sleeping at the sick people's homes, part of the Linat Tzedek Committee. Our mothers helped with Matan Baseter, unpublicized charity.

In those days, Matzot were baked in a primitive manner. This kept the youth busy for a lengthy period of time. In order to earn, more people worked to the point of exhaustion. We organized ourselves to replace them during rest time. As in every settlement, there were some large families who were poverty stricken and who were additionally burdened by the city taxes. There were a few individuals who emerged to alleviate this burden. My father, for example, was among those who challenged the city and used his sharp pen in the battle against the leaders. Most of the people in town were Zionists. They bought Shekels and supported AP”K Bank. They were hoping and dreaming of immigrating to Israel when Mashiach comes… That is how their life ran its course.

World War I broke out suddenly. We were shocked. The Germans entered the city without any warning. The Russians disappeared, and the Jewish citizens escaped to neighboring villages. We, the Jewish people, having been accustomed to German intruders, were not surprised. The Germans looted the abandoned property. My father remained in the town to help reduce the damage. He ran from house to house with a hammer and nails, and locked the doors tightly. I recall my father coming to the village to which we had escaped. We wondered why he was limping and he told us how he walked in the street of our town and he saw an open door in one of our people's stores. When our father entered the store he ran into Lupinka, the well-known thief. He injured my father during a physical confrontation.

The German Command replaced the Russian command and restored order. Many of their higher officers dwelled in civilian homes. The relationship with the Jewish population was decent once again.

When the German conquerors took over Lithuania and Poland, they recruited the youth from both countries and used them to benefit their army. They built bridges and paved roads. They transferred youth from Poland to Lithuania in order to prevent a revolt. Many Jewish youngsters were brought to our town where they were enslaved. The adults were placed in the three local shuls and those were fenced with barb wire. The youths were placed in shacks set up for them. That is how two labor camps were established. We called the shacks barracks and the workers zvungst arbeiter (forced laborers).

The following songs remain in my memory from that period. They express the unbearable suffering that the forced laborers were enduring and their longing for freedom.

by Yehuda Adar, husband of Chassia Adar Lifshitz a forced laborer

[Yiddish]

| Don't seek me any longer in the green garden | |

| You will not find me there, my dear | |

| In a barrack fenced by barb wire | |

| There is my place of rest | |

| Don't seek me where there are no servants | |

| You will not find me there, my dear | |

| In the place of slavery, blacksmith work | |

| There is my place of rest | |

| Don't seek me where the violins are playing | |

| You will not find me there, my dear | |

| Where people remain silent when scolded | |

| There is my place of rest | |

| Don't seek me where one hears happy talk | |

| You will not find me there, my dear | |

| Where many people suffer hunger | |

| There is my place of rest | |

| And seek me where hammers bang | |

| Find me there, my dear beloved | |

| Where life clouds in the barracks | |

| There is my place of rest | |

| And if you truly love me | |

| Then wait for me, my dear beloved | |

| Until freedom will finally come | |

| And my place of rest will change. | |

by Yona Akravi / Rabinowitz

[Yiddish]

| There in Neishtot in the barracks |

| Sits the forced worker crying |

| There is nothing like the big calamity |

| And his heart is like stone |

| Dragged away from his home |

| As programmed, brought to Neishtot |

| To break his heart and feelings |

| And his body made into a skeleton. |

| Home, home, my family! How could you |

| Snatch me away from them? |

| When eating, or drinking, I cannot |

| forget you, wherever I stand and wherever I am |

| When will the sun shine for us already? |

| When will we come out of this scheme? |

| When can we see our beloved home again? |

Entering the camps was forbidden, but we were able to see that the conditions were sub human. They were terribly overcrowded, undernourished and in poor sanitary conditions.

We organized aide groups and looked for ways to get the government to give support to the needy. We were only permitted to enter the youngsters' camp. We did our best to bring some warm food to the sick. It was absolutely forbidden to enter the large camp. We were only able to come close to suffering adults in secret. People died from exhaustion or contagious illnesses. It was at that time we knew the Germans; without a declaration 'to destroy a nation', they behaved like killers towards human beings.

In addition to the two camps, Russian captives and some Jewish soldiers were taken to an abandoned Russian army camp. Once again, a committee was designated to send help to the needy. The youngsters in town were always ready to follow orders and take action.

When the war was over, new problems surfaced. News arrived about different newly organized youth movements. The Pioneer Movement was founded and the youth was attracted to join it. At that time family dynamics changed, and there would be rifts between the parents and the younger generation. Sons and daughters left their parents and the town lost its former charm.

Aryeh Zaks, Givat Brenner

In the early nineteen thirties, when the Nazis were rising to power, the Jewish world was fear stricken. Many German Jews immigrated to Israel and transferred some of their property there. This immigration strengthened the building of The State. This change was labeled Prosperity. The British Mandate rule could not ignore this new transition, and was forced to open the gates, which had been closed to the influx of pioneers who had knocked at its doors. The Pioneer (Chalutz) Movement saw new awakening and new training (Hachshara) sights were established throughout all European countries.

Avraham Binyaminovitz set up a Hechalutz / Pioneer branch, in our town. He had trained elsewhere a number of years earlier but found himself in our town when the gates closed. Our own home was in the center of town and it served as a home and a club. Both my brother Avraham Z”L and I, were active with the youth and helped organize them to join the training.

In the nineteen twenties people from the town had already left for Israel, and their courageous endeavor served as model to us.

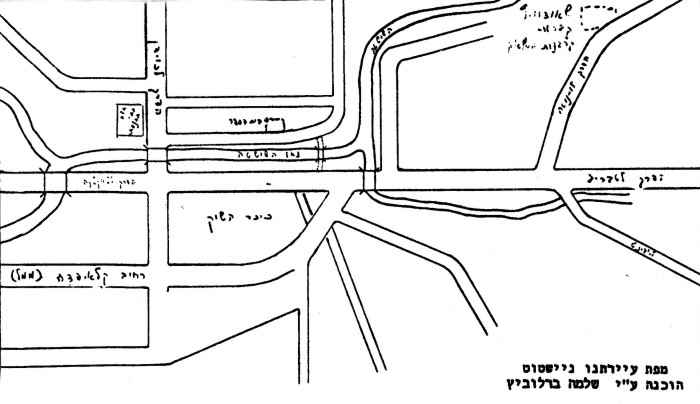

Let us remember the active members of the branch in our town, who did not merit fulfilling their dream and reaching The Land of Israel; Shalom Berlowitz passed away from illness before the Shoah. Many people certainly remember his acting gift, with which he performed from time to time at our town's drama play. The teacher Korbman, was killed in a car accident. Leib Lapin, Sarah Gordon and others, shared the burden and contributed to ongoing activities and ideological developments.

We also set up a branch of Hachalutz Hatzair (The Young Pioneer).Note that our town was predominantly Zionist and met the requirements of the movement. Many people would have surely landed in Israel as the realizers of the pioneer movement. I can remember vividly the day that we left for training in Memel. That day turned into a day of celebration for us. At Hachshara / training, our conditions were poor, with crowded living, shortage of work and pitiful living space. There was a limited number of immigration permits. Preference was given to immigrants from Germany, and it was fair. In spite of it all, there was great enthusiasm and we regarded our departure to Hachshara as one foot in Israel. The road ahead was very long!

With the coming of the Holocaust, terrible news reached us about the murder of our dear ones that were left behind. We stood helpless, unable to come to their rescue. Before my eyes, is a vivid picture of so many of those, with whom I trained at Hachshara and with whom I worked for the Organization. They were killed with other Jews, by the murderous Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators.

May these words of memory serve as a monument to all those who perished in the terrible Holocaust.

Avraham Binyaminovitz, Ra'anana

Remembering the youth organizations of our multi-faceted town, Neishtot, fills my heart with respect and appreciation for the range of activities, that aimed to ignite enthusiasm, in the awakening of the national Zionists, and to inspire our youth. I reminisce about our Friday night gatherings for which we arranged a rich cultural program. Programs such as question and answer nights, on current intellectual topics, would end with group singing, songs of The Land of Israel. I want to point out the commitment and dedication of the members who emptied the charity boxes, the “Blue Box” of the Jewish National Fund.

Youth movements took a very active part in national fundraisers such as The National Fund and The Foundation Fund. Who can forget the fiery dedication of the old Beara-Dov Broda to these fundraisers?! One can say that no one refused to donate to the national fundraisers and every home in our town had the Blue Box. The youth movements were racing to find creative ways to increase contributions. I can clearly remember the project of selling Schach for Succot. All donations went to Israel National Fund. For funds for Keren Hayesod, we mobilized a few laymen, such as Mordechai Blumberg Z”L, the bakery owner. He often left his store in order to be actively involved in this Mitzvah of collecting funds, reasoning that national needs come before his personal needs.

In the year 1931-32, the approach of Nazism became evident. We were close to the German border. At the same time, the local chalutz committee was under pressure to prepare for hachsharah (training) to immigrate to Israel. Unfortunately, Memel, the largest hachsharah (training) center, could not accommodate the many applicants. Our local board was only able to place a few people from Neishtot. These people are in Israel.

We tried to search for training places near Neishtot, but we were not very successful. I must note that although the Nazi threat was in the air, a number of our children did not yield the call to immigrate, for personal reasons or family circumstances.

Binyamin Robinson / Cholon

The community involvement was well established and well rounded. I will enumerate the main functions to the best of my memory.

The Community Committee:

In the beginning of the Twentieth Century, Lithuanian Jewry enjoyed broad autonomy. In Neishtot too, a board was appointed, charged with a vast authority to run the Jewish community's religious affairs, education, culture, social services and more. The committee had legal rights to charge all Jewish citizens taxes, to defray the cost of local needs. The community and committee owned a few thousand acres of farm land, outside the town. The property would be sold to Jews who would wish to purchase it. The rest of the property would be chartered to Jewish citizens.

Autonomy was suspended after a few years. A small committee remained in charge of religious matters and a registration of personal status (birth, marriage…).This responsibility was given to a government appointee. The farm land remained in the community's ownership until the Russian conquest in 1940.

The Folks Bank:

The Folks Bank was built on a cooperative basis, branching off from the National Union. Every corporate member was entitled to a short term payment loan. For most businessmen, especially the small ones, craftsmen, and workers, this was the main source for survival. This bank operated until the takeover by the Soviets.

Educational and Cultural Establishments:

In 1920 Hebrew National elementary school was founded. Most of the children in town attended the school, tuition free, financed by the authorities. A number of students continued their education in a Pro-gymnasium (junior high school) that existed until the middle Thirties.

There was a “Cheder”, but only a small number of students attended it. A small number of youngsters continued their studies in high school in the nearby cities Tauragė, Telšiai, Memel (Klaipėda) and others. Others continued their Torah studies in Yeshivot in Telšiai, Kelmė and Slabodka (Vilijampolė). There was a local library in the elementary school building. Most books were in Yiddish but there were some Hebrew books too. The library was run by active volunteers. Various recreation clubs were available in the town and on occasion some theatre lovers put on drama productions.

Chevrat Gemara, Linat Tzedek, Chevra Kadisha:

As in all towns, these organizations were active in our town. Many members of our generation will surely remember the Siyum, the celebration upon the completion of a Gemara tractate, which took place every few years. I clearly remember one such event, at which the good news arrived that Shalom Schwartzburd was vindicated. The excitement and joy were ecstatic.

Youth Movements:

The most established, large entity was the Maccabi Organization. Almost all young people, of all ages, up to post army service, were members. The football team and its fans were in the center too. Competitions against Maccabi teams of other cities, took place almost every week. On occasion they even competed against German teams from Memel district, and against Lithuanian soldiers. There were other athletic and sport events. Due to shortage of trainers and tax funds, they were not highly successful.

There was also a base of the Mizrachi Pioneers. Members of all groups went for training. Neishtot too had a training group. Participants with certification received documents for immigration to Israel.

Officially, they had Zionists parties such as T.S. , צ.ס. הצה"ר and one could even find a small communist presence. They were most active during elections, at fundraisers for Israel National Fund, Keren Hayesod, and Keren Tel Chai.

Binyamin Robinson / Cholon

Independent Lithuania

In the years that followed the rule of the anti-Semitic Russian Czar, and the harsh German conquest (post World War I) Neishtot Jews sighed a breath of relief on the first few years.

For the first time in history, the Jews enjoyed equal rights and a rich cultural autonomy. An independent board was authorized to oversee the community.

In 1920 a Hebrew National elementary school was founded. The students learned tuition free, and the teachers' pay came from the government budget.

A vibrant active community began to develop. Many organizations and committees were active, from Chevra Kadisha to Zionist youth organizations. The economy improved, especially after the Memel District merged with Lithuania. A National Jewish bank opened, founded on corporate principals. It helped improve the economic conditions of Jewish citizens. Zionism was the dominant philosophy of life. A small number of people, mostly elderly, supported Agudat Israel and was against Zionism. There were a few leftists.

I recall the festive convention when the League of Nations authorized the British Mandate to recognize the Jewish link to Palestine. On that festive occasion, our young men came out riding decorated horses, dressed in blue and white, leading the celebration. No one stayed at home, or did not participate in this joyous demonstration.

There was a good relationship between the many Jewish citizens, and the Germans in the city. On the Maccabi team, there would be one or two Germans. Competitions against German teams, from the Memel surroundings, were held frequently.

In the twenties, they founded a National Lithuanian Pro-Gymnasium, (Junior High School), where many of the National Hebrew Elementary students graduated. In some classes there were as many Jewish students as there were Lithuanians. They had a normal relationship with no particular closeness or animosity.

The economic conditions were fine for most families. They occupied themselves in small businesses. There were shop owners; some were rich, and there were craftsmen. They developed a strong business relationship with Memel.

Neishtot became a center for farm export. They traded horses (a substantial portion of the Lithuanian export), geese, flax, eggs and more. Although the big exporters were not necessarily Jewish, but rather local Germans, many of the Jewish families supported themselves in this business. The geographic closeness to the German border and the close contact with Memel (Lithuanian: Klaipėda) had a large influence on the city. In addition to the economy, Western Civilization and its culture integrated the society without hurting its strong Jewish tradition. This may have been the reason for the unity and harmony within the community and it lasted for generations.

Unlike the neighboring towns, our town looked more advanced and modern.

The Fascists' overtake of Lithuania in 1926 did not impact the Jewish community greatly. Business was as usual. The young people studied, the youth movement activities continued, and the political discussions amongst the Zionist streams grew stronger. It is important to note that even in the days of Arlozorov's murder and the Stavsky court battle, the peak of internal discord within the National Zionist movement, the town debates were more intense, but never crossed the boundaries of a political debate. There was no evidence of personal animosity.

In the early thirties the picture changed. There were two reasons for that; one was the financial crisis that hit the entire West (the Great Depression) and penetrated Lithuania, and the other, the rise of the Nazis in adjacent Germany.

A steep economic decline and low prices of farm produce, hit the farmers hard. Most of them had not established themselves after they received their land, following the agrarian reform. The farmer turned into a poor man overnight. The town people depended on the trade with the farm, and were hit hard. The German border was closed to the Jews at around the same time, which cut another important source of living. The economic conditions became very difficult. It was a severe blow to the maturing youth. They could not manage to settle down and become independent. People began to move to other places. Memel, the closest industrial town business was developing. Many people were attracted there. Others went to the capital Kaunas (Kovno), to Šiauliai and to other destinations.. People looked for ways to cross the ocean, but very few were able to get there, since most countries were closed to immigrants' entry.

The greatest desire was to immigrate to Eretz Yisrael. In the early twenties a few individuals from Neishtot managed to immigrate. Those were the pioneers who had difficulty convincing their parents that they were looking for the right route. Things changed now. Many left to be trained (Hachshara) with the blessing of their families. The British Mandatory strict rules made the journey unpredictable.

Antisemitism grew, the economic conditions got more austere, and the chances for immigration became slimmer. At the end of the thirties, there was a minor pogrom on a market day. There were no casualties but it was not far from that. Jews were beaten, property was damaged and the police struggled to gain control and the military was needed to suppress the violent attack.

In March 1939 Hitler occupied Memel and our town was now less than 2 Km from the German border. Many of those who had gone to work in Memel were now the first refugees. They had nothing to return home for. Unemployed, with no source of income, in dim days, grim conditions, and a dark future, they continued to live and hope.

Then the Russian conquest occurred.

Shoah Drawing Close

Following the Russian conquest, the town was considered part of the border in every aspect. One needed a special permit to enter the town, with many other restrictions. At that time, about 120 Jewish families lived in the town (around 400 people).There were hardly any income sources and the young people, new couples, continued leaving mostly for Šiauliai and Kaunas (Kovno), but to other places, like Jonava, too.

The Germans invaded the city in the early hours of the outbreak of World War II. On early Sunday morning June 22, they completed the invasion of Neishtot. Only one family, Shimon Aharon Berlowitz and his entire family, managed to arrive safely at the USSR. It is worth noting that this family survived the four years of the terrible war and returned. On May 11,1946 the Lithuanian guerrillas dynamited their home. Five family members perished together, with Motele Berlowitz among them. Motele had been a handicapped veteran who headed the local board. Only three family members survived: the father who was away, Shlomo, the son who was injured and later would recover, and a daughter.

Let us return to the beginning of the war. A small Russian border patrol unit was stationed in Neishtot. When the Germans invaded, the Russians killed 12 German soldiers. The Germans blamed the Jews and in retaliation they shot them, arrested many men and locked them up in the Lutheran Church. A local Lutheran minister saved those Jews, when he testified before the invaders that those Jews took no part in the shootings. They were then set free.

Suffering and hardship began in the early days of the conquest. The activists of the local Communist party included Jews and they were all shot. Young girls were arrested and shot. Shortly after, the Jews were transferred from their homes to places resembling ghettos.

They were crowded into alleys near the Jewish school. On the Nineteenth of July, 1941, all men from age 14 and up were arrested.

29 of the young men were sent to a camp near Šilutė (Heidekrug). The rest, together with men from the next town Vainutas, were killed and buried in pits in the ground, which had been dug ahead of time, four kilometers away from Neishtot, near Šiaudvyčiai. The women and children lived for around six more weeks. The Germans enslaved them and forced them into labor such as field work. When the field project was complete, in early September, they too were murdered and buried in the pits near Šiaudvyčiai. Dr. Shaw from Heidekrug, Ðilutė conducted the annihilation of Neishtot Jews. In 1964 he was arrested and judged in West Germany.

Many hardships struck the refugees who were locked up in the local camp. There were Jewish people from various nearby communities. They endured harsh labor, illnesses, and brutal beatings, as was common for the Nazis.

The local camp closed down after approximately two years. The remaining prisoners were transferred to Auschwitz, the well-known torture camp. Very few remained alive; only seven.

It is valuable to tell a short story of one of the survivors:

Raphael Lasky, a son of a large family, was locked up in the local camp together with two of his brothers. When the camp was terminated, they were transferred to Auschwitz. Two brothers were killed within a short time and he remained alone. After the Nazis suppressed the Warsaw ghetto revolt, Raphael was transferred to a new camp and was assigned to clean the ghetto ruins. Hungry, ill with Typhus, with 40c degree temperature, feeble, he was compelled to do a different job. He was expected to die. The revolt of Bor Komorowski broke out. The rebels neutralized the German guards and the prisoners were set free. Our Raphael took part in the battles and after the defeat of the revolt he went down to an underground bunker. For six months, he lived with a few Jews in the bunker under the ruins, until the Warsaw take-over by the Red Cross. He was set free and after the war he returned to our city in the hope to find a survivor. There was no one there to be found. The only one that survived the Nazi hell, his brother Aryeh, died in the battles in the Russian front. A few hours before the explosion at the Berlowitz home (told above) he left his house. That is how he was saved once again.

Raphael immigrated to Israel and we all share the joy that he rebuilt a home.

A small number of survivors from our city lived in Kaunas (Kovno) and Šiauliai when the war broke out. Some of them endured the torture of these ghettos, the labor camps. Others found their way to the Partisans in the Lithuanian forests. (S. Abramowitz was one of the casualties in those battles). A few people reached the USSR. Some were mobilized to fight at the Lithuanian Division, some survived injuries, and others never made it.

Luckily the Lithuanian Division set our town free. One of the first to enter was a member of our own community. He found one of the murderers and killed him. That is how he took revenge on behalf of our beloved ones.

It is important to mention that not one person of the Neishtot community was saved by the local Lithuanians.

After the war, ten families who came from Neishtot returned to Lithuania and settled in Vilnius (Vilna) and Kaunas (Kovno). Most people managed to immigrate to Israel, before the borders were closed to them. They were received warmly, with open arms, by the town people (immigrants from Neishtot).

From the Archives of Lithuanian Jewry

The Germans invaded Neishtot at the early stages of the outbreak of the war. On an early Sunday morning, a few German army units were spotted from the Russian officers' homes. They opened fire against them immediately. The officers' wives shot them with sub machine guns and killed 14 soldiers. The Germans' reaction was to grab a large number of Jews and lock them up in the local German Lutheran church, on the same day. The Germans would not listen to the Jews' pleads of innocence. The Lithuanian Priest however, came to their rescue and testified on their behalf. By Monday morning the Jewish captives were set free.

During the first few weeks of the invasion, the Jewish citizens were assigned to do various jobs; they swept the streets, they fixed the roads and many worked at the German operated bakery.

The supervisors were mostly Lithuanians, and they caused no harm to the workers. Note, that in spite of the vigorous German coaxing, in the early days the Lithuanians hardly changed their attitude towards the Jews.

In the beginning of July all Jewish people in the town were instructed to leave their homes and crowd themselves in a few houses on the Šustis River Street. This was the Neishtot ghetto. It was well known, that the men in the neighboring towns had been taken out to labor camps. The men here were readying themselves to leave, and everyone was packing a bag of clothing to take along. Lo and behold, before long, came the turn of the Neishtot men.

On Shabbat, Twenty Fourth of Tammuz, the Germans blocked the entrance to Jewish workers at the army-base bakery. They had arrived at their regular morning hours, but from there they were taken to the Christian Cemetery. There, they were instructed to dig graves for the fourteen fallen German soldiers who were killed at the entrance to the town on the day of the invasion (up until this time they had been buried in a field corner on the road). When the job was complete and when all the laborers finished sweeping the streets, they were told to return home and be at the Bet Midrash yard at 12:00 noon. All men from age 14 and up were to report on time. After that time, the SS people who had arrived here, under the direction of Dr. Shaw from Heidekrug (Ðilutė), inspected the houses and made sure that no one stayed behind. One German walked through the line in the Bet Midrash yard, sent home any boy that looked too young. Eight men were sent back to be in charge as care takers of the community. Nachman Gold, his son Yisroel, and Betzalel Berlowitz were among them. The rest of the men were taken out at 3:00 in the afternoon. They were told to walk to the barracks in Sugintai, the village, on the way to Vainutas. Old and sick men were brought there on wagons. At the barracks, the Germans separated the old and frail into a special group. They announced that the people in this group will not be taken to labor. The second group of people, over the age of 50, was told that anyone who feels too weak to work hard can join the first group. The men thought that if they were too weak to work they would be sent home. Many people turned to the SS soldiers to complain about their health. The SS “graced” them too, and let them join the weak people. Over 70 people were taken heading to Vainutas. The remainder 27 men were left in the barracks. Towards evening a group of Jews arrived from Vainutas. The men reported that in their own town too, all men had been gathered and on their way, near Šiaudvyčiai, the old and frail were separated from them, while they stayed behind.

That evening, all Jewish men in the barracks were ordered to board the trucks that would take them to the German border. The Jews from Neishtot, who had brought along clothing, requested to pass through Neishtot. Dr. Shaw gave permission on condition that not a word would be spoken during the stop at the town, or when they would meet their families. The car stopped at the center of the town market, and each one of the men went to his home escorted by an SS. They parted from their dear families with tears in utter silence.

The German escorting the young men to Yoselovitz's home demanded that the lady in the house hand him her gold. She answered that all she had was her wedding ring. Enraged at the woman, he threatened to conduct a search, and if he would find gold, all the members of the house would be shot. He also had his eye on a young boy in the house, Mendel Yoselovitz, a thirteen years old boy. The SS ordered to put the young boy on the truck. The mother cried that he had been sent home that morning. “Whatever Dr. Shaw says” answered the German. He took the boy, brought him to the center where Dr. Shaw ordered to place the boy on the truck.

Late that night, the Jews were taken to Heidekrug (Ðilutė), fifteen kilometers from Neishtot. On the following morning, they found out about the tragic fate of the people in the group of the old and frail. Those men, from Neishtot and Vainutas, had been murdered yesterday, near Šiaudvyčiai. The people of Neishtot remember that day as “The Black Shabbos”.

Neishtot men who were brought to Heidekrug (Ðilutė)were now placed in labor camps with a few hundred Jews from nearby shtetls. There, they met a man from their town, Binyamin Lapin, who was caught in a nearby town. There were now 29 men from Neishtot.

There were a number of camps near Neishtot and from Kulėšai you could see the tall buildings of the town. Many supervisors and SS had been personal acquaintances and even friends of the people, in the past. Stonkus, the big chief of the camp, had been an old customer at their shops. Now, of course, they estranged themselves from the Jews and brought more suffering upon them. The conditions in the camps were very bitter. They slaved, they starved, and they were tortured. They were getting weaker every day.

The men from Neishtot would meet people from their Lithuanian neighborhood who would give them some reports on the latest in the ghetto. On occasion, they were able to get notes from their families. Per these messages, the women went to work for the farmers in the fields each morning. The ghetto probably survived till after the potato harvest, in mid-September. Then, one day, the Germans announced that they are transferring everyone in the ghetto to the place where the husbands were working. They advised them to take along as much belongings as they can. On the next day they took them to Šiaudvyčiai and murdered them. It is estimated that they were killed on the fourth of Tishrei, the Twenty Fifth of September. For the survivors of Neishtot this has remained the Memorial Day for those who were murdered.

The Jewish prisoners were kept in Heidekrug camps for over two years. The Germans plotted a number of surprises in which many of them, including Neishtot citizens, were murdered. At the end of July 1943 all Jews were transferred to Auschwitz, Poland. On the day of their arrival, the first of Av, the Germans arranged an operation in which ninety nine people were thrown into the furnace. Many of the victims were from Neishtot.

In October 1943 many Jews, Neishtot people included, were taken out of Auschwitz and transferred to Warsaw. There, they were commanded to clear the ruins of the destroyed ghetto. Their physical state and sanitary conditions were very poor. In the winter, Typhus plagued a huge number of people who were never able to survive. Neishtot men were hit hard too.

With the battle drawing close to Warsaw, in summer 1944 the Germans took the Jews out of the city. They left behind a few hundred men so that they can work them during bombings. Eliezer Gold and another former Neishtot citizen were among the men who remained behind. With the arrival of the Russians, they were liberated. Those who were pulled out of Warsaw were taken to Bavaria, Germany. The people from Neishtot were put to work in Mühldorf, a branch of the large camp in Dachau. Their conditions were desperate.

With the conquest of the US army in Spring 1945, people came out of the Bavaria camps. There were Neishtot survivors. There were only four men who survived; Dov Geller, Ezriel Gluch, Mendel Yoselovitz, and Binyamin Lapin.

Ezriel Glick

I was born in our town Neishtot, in 1924. My parents were Tuvia and Faiga. We were three sisters; Miriam, Ethel, and Aida, and four brothers; Mordechai, Ezriel, and Avraham. I want to recount the experience of the Jewish people of Neishtot during the invasion of Hitler's army into Lithuania. I also want to talk about the few remaining survivors who went through the Shoah. It is their charge to tell the future generations about the bitter days, that destiny appointed to our dear ones, the Jews of Neishtot.

Neishtot was a small town. Around a hundred and fifty Jewish families lived there. Before Hitler's rise to power, Lithuanians and Jews lived there together. They went to the same schools, and one might note, that the Jews who lived there, were well respected. On occasion, one would notice signs of antisemitism, but they were mild.

With the German conquest of the Memel region, (which had belonged to Lithuania), the border was less than two and a half kilometers from Neishtot. News spread from across the border that the condition of the Jewish people in Germany was deteriorating.

With the German occupation of Memel, all Jews of the Memel region left and relocated to Lithuania. Now, the city looked paralyzed. All commerce in the towns around Neishtot had gone through Memel, the city of the main port, the only port in Lithuania.

I personally studied in Kovno, at ORT, the vocational school. On the twentieth of June 1941, I arrived in Neishtot for the summer vacation. I found a very quiet town, with a very tense atmosphere. Everyone was discussing the signs of war. We were receiving news about a huge German military preparing to invade Russia. The Jews sensed a holocaust nearing, but we could not have imagined that it would come to a destruction of all the Jews.

A large number of Neishtot Jews had business relationships with the Germans for many years. They could not believe that this very nation can turn its skin color, and take on the image of a predator.

And this is how it started, on the twenty second of June 1941, at four o'clock in the morning, the war broke out. A small number of families managed to escape, but the majority of Neishtot citizens remained in town.

Within a few minutes German soldiers entered the town. By ten o'clock in the morning they gathered all Neishtot men to the Protestant church of German speaking citizens. We did not know what happened. At around twelve o'clock, a high ranking German officer turned to us in Russian and in German: “Civilians shot German soldiers and some of them died. We had decided to punish you and kill every tenth person. You are however lucky, that we have determined that it was Russian soldiers dressed up as civilians. We are setting you free and advice you to refrain from roaming around in the streets”. I returned home shocked and frightened. Deep mourning had befallen the Jews of Neishtot. My heart told me that disaster is ahead.

Shortly thereafter, new rules against the people of the town:

A few days later, we heard that five of the community girls had been taken by the Germans and their Lithuanian assistants to an undisclosed place. They were never seen again. Among them: Rivka Lesin, Menucha Wolpert. Shaina Glatt-Shorr, Gisa Berlowitz, Chana Schneid and Rachel Lerman, were among the missing girls. Rivka Winick was shot to death too. On the third week, they rounded up all Jews and closed them up in one street which they turned into a Ghetto, with everything that goes with it. It was in the street of the Synagogue and the school.

On Shabbat, the twenty fourth of Tammuz, the nineteenth of July, all Jewish men of Neishtot, from age thirteen and up, were assembled into the synagogue courtyard. From there, they were taken to barracks of the Lithuanian army. The sick and old people were taken on wagons. Around twenty five young men, and I among them, were returned to the town to pick up clothes and see our homes for the last time.

Then, we were taken to Heidekrug, Germany. The rest of the men were taken to Šiaudvyčiai, near Neishtot, where they were shot by the Germans and their Lithuanian aides. The women, children and ten men stayed at home. I remember Yisrael Gold, Betzalel Berlowitz, Yaakov Nudel, Mordechai Blumberg, and Hirsha Grossman.

I arrived at the first camp in Heidekrug. On the following day, we found the clothing of the martyrs. They were undressed before they were shot dead. Many of us recognized the clothing of our dear ones. Then we knew the bitter truth on the fate of the sad Jews of Neishtot. I was sent to a camp in Usėniai, near Katyčiai. In this labor camp we had to do back breaking work, digging canals, water drains, and more. After a few days we recognized one of the Lithuanians who worked with us as a manager. For a fee of gold and silver he agreed to go to Neishtot to find out what happened to the last few people left in the city.

He told us that in August 1941 there were still women, children, and ten men living in Neishtot. A few of us received letters from the women. I received a letter from my mother. She wrote to me that she was the happiest in the world, when she found out that I was alive. She also wrote that they were constantly in fear of what was coming from the German murderers and their Lithuanian helpers.

On the following month, we asked the Lithuanian to go to Neishtot to find out the condition of the last remaining Jews in the ghetto. This time he refused to go and turned down all promises of gold and silver payment.

Gradually, the terrible news, reached us that even the last ones were no longer alive.. Part of us refused to believe the terrible reports that leaked to us occasionally, about the women, children and ten men who had remained in Neishtot, murdered brutally, by the Germans.

We were in the district of Memel until July 1943. We did all types of work, like digging borders, digging up potatoes, and work in fields and on roads. The Germans abused us in various ways. They arranged selections, and tens of Jews from the nearby camps were sent to Neishtot. There, they were tortured and shot to death.

In July 1943, we were sent to the notorious Auschwitz. Most Jews were put into gas chambers. A small number, seventy of us, remained in the camp. In Auschwitz we saw the death factory, the crematoriums, and gas chambers, where the unfortunate European Jews were brought to death.

I worked not far from there, and I was aware of the bitter truth. We sensed that we too would be sent there imminently. I saw the arrival of trains, transporting our poor Jewish brothers arriving each day. They were all sent to Gas chambers.

While at Auschwitz and Birkenau, Jewish people arrived from Sosnowiec and Bendin (Bedzin), Poland. After six weeks in Birkenau, we were sent to Warsaw. There, we were assigned to clean up the ghettos. Before Yom Kippur, a few thousand Jews arrived from Birkenau to the ruins of Warsaw ghetto. The streets were blackened as a result of the wild fires burning there. A deadly silence of pervaded. Some of Neishtot Jews were put into gas chambers. Only ten or fifteen of us made it to Warsaw.

In Warsaw, our job was to blow up homes and clean the ghetto. The Germans moved the bricks and iron to Germany. On occasion, the Germans would catch people that managed to hide in the ruins and holes in the walls. They would kill them all with no mercy. The Germans found in the bunkers merchandise and storages with valuables, clothing, shoes and more. I found some gold in Warsaw ghetto. Thanks to this find, I was able to get food and survive. I was also able to help a few fellow Neishtot people who were with us.

In July 1943, when the Russians were advancing to Warsaw, the Germans decided to take us out of Warsaw. At the end of August of that year, two days before the Polish Warsaw Uprising, they took us out of the Warsaw camp and marched us to Kutno. There were a few thousand of us there. Only two hundred men remained in Warsaw.

At the train station in Kutno, they put us on cattle trains and took us to Dachau. After a few days in Dachau, a group of us, with some Neishtot men, were sent to Mühldorf. We stayed in Mühldorf for the entire winter of 1944. We did all types of work, built underground bunkers, and more. We were also instructed to uproot forests, through night shifts too. The news that leaked from the battle front, planted hope in us, that relief was close and our suffering was about to come to an end. That gave us strength and courage to continue to bear the suffering. We wanted to see the defeat of our torturers and die….

At the end of April 1944, we were once again put on trains and sent to the Alps. They wanted to destroy us till the very last moment, right before their downfall. They even verbalized it:” At five minutes before twelve o'clock, when we will be defeated, we will kill you all”.

We travelled for a few days and nights, aimlessly. The roads were damaged from the allies' daily bombing. At one point, near Mühldorf, a few other fellows and I tried to plan an escape. I was the last one to jump off the train. Before I had a chance to distance myself from the train, the Germans noticed a conspiracy and started shooting in all direction. I took advantage of the darkness and returned to the train, unnoticed. The Germans were looking for other people and when I got on, they heard a slight rustle. Miraculously, the train was just starting to move, and I was saved. On another occasion, we were saved from tragedy, when our train arrived at Poing, Near Munich. There, there was a local German revolt against the Nazis, and the train workers yelled: “Friends, you are free”. This was the result of the collapse of the front. Our guards did not know what to do, so we started jumping off the train and scatter in the direction of the towns and villages. In the meantime the reign of Nazi terror reorganized itself and gained control of Munich. The guards and German soldiers in the region gathered us into train cars once again. They did not leave us alone even under showers of shots. That is how tens of Jews in this transport, were murdered in the final minutes, right before the liberation.

We continued to travel for another few days. Fortunately, the train rails were cracked from allies' bombing. Thankfully, the Germans could not transport us to the mountains to fulfill their wish.

On the thirtieth of April we arrived at Bahnhof Feldafing station, near Lake Starnberg (Starnberger See). We heard echoes of canons from the battle front. The guards were quieter than usual, they shaved, and some of them changed into civilian clothes. At that point we felt that this is the end of the war. We prayed that we should have the strength to witness our enemy collapse. In the morning of the first of May, the unbelievable miracle took place. We jumped off the train cars. There was no guard around. We were FREE.

We heard the rattling of tanks from a distance. Slowly, we walked away from the train, turning to where the sounds came from. We then saw tanks of the American Army. We will never forget that moment!

Soldiers began to throw food, chocolate, and cookies to us. Jewish soldiers jumped off the tanks and kissed us. We rejoiced but wept; we were laughing and crying together. We could not believe it. Were we really liberated?

Within a moment, all seemed forgotten. We are liberated! We are free. Were we really free? Our body was free but our soul will never be free of what we had experienced, having seen the destruction of European Jewry with our parents, dear brothers and sisters, and the Jews of Neishtot, may they rest in peace.

[Yiddish]

Eliahu Feit, Herzlia

Our town was pretty much like any other shtetls in Lithuania, yet it still had its uniqueness among the entire region.

I would like to mention here a few incidents which not everyone is familiar with.

1. As result of the crisis of the nineteen thirties, there was an inflow of poor people going from house to house, from very early hours of the morning until late in the evening, tearing up the place. It was decided to set up a fund, so that when a poor man comes, he will receive 3 Litai, on condition that he will leave and never be seen again. But who wants to undertake such a burden, and deal with broken people? Charity however, is a Mitzvah, so of course Itzik Feit would be the one to undertake such a responsibility. This was not an easy task. A Jewish man would come a few days early, or, on winter days it would be too cold outside, but Reb Yitzchak is a merciful man with a Jewish heart, and he would do anything to help them and earn a Mitzvah.

2. On a nice day, a distant relative from America would send a few hundred dollars, asking to use it for a charitable act, Gmilut Chesed, to help the needy. There were little market venders, butchers, who used to borrow or lend a few Litai until after they would sell their merchandise on Market Day. But there were others who did not have basic living necessities. They came to borrow and left collateral, like a watch or a few rings, bracelets, and more. There were those who could not leave anything. Or, those whose child got engaged, or had another Simcha, and needed the golden items, and borrowed in exchange for silver of copper things. They also started bringing pots and pans… till Pesach….

All in all, Reb Yitchak was the Baal Rachmonus, the merciful man, and nothing was left from the endowment.

The war hit me in Kovno. In the beginning there were many people from Neishtot in the Kovno ghetto. We met often, but slowly they took the city apart until there were only a few of us left.

In the spring of 1943 I was out in a forest with a group of people, going through terrible hardships around the Partisans. There, I was thrilled to meet Shlomo Abramovitz, a friend from my town.

We often met in difficult moments, and shared the hope to remain alive and be able to tell about the big tragedy that befell our Jews, our parents and our families. Unfortunately, it was difficult to stay alive in the Partisan forest.

On a dark day, I received information that my friend, with his nine other Jewish friends, were taken to carry out an operation, and no one returned. When I came out of the forest I looked to find out if any of them survived. Unfortunately, none of those who had been with me in the ghetto, survived.

I lived through difficult times, during my years in Kovno, then Vilna, then the ghetto, partisan life and more. I merited to build a family and I was fortunate to immigrate and live in our Medina,(State). I believe that I overcame so much in the merits of my parents Z”L who were rich in Torah and Tzdakah.

Shlomo Berlowitz, Herzlia

I remember the twenty second of June, 1941. At exactly four o'clock in the morning, we heard the sounds of shots coming from the German border, particularly from the Kulėðai Village.

I was home. I had returned from the teachers' seminary where I was a student, for a week of vacation. On that day I was supposed to return to Tavrig (Tauragė) for two weeks of army training. It was very tense in our town, throughout that whole week. The authorities distanced people and cleared homes near the border.

On, the twenty first of June, a German airplane was seen, flying very low in the sky above Neishtot. All the people that were attending services at the synagogue went out to watch the airplane. They sensed that they were not about to hear good news. Our horses were out in the field at the time. My father was busy transporting rocks, used for security needs, for the Red Army. Every evening, my father sent me out to bring the horses back to the barn. He wanted to make sure that we would be prepared for any possible event. At home too, necessities were being packed, for the possible need to leave the house temporarily. There was fear of what was coming, in the air. Disaster was anticipated.

On Shabbat, the twenty first of June 1941, war was the only talk of the day. Three hundred Soviet border patrol soldiers were found in the barracks. On the week before that, the Soviet army police had carried out an operation which we called “The Big Expulsion”. All activists of the former regime were expelled to Siberia. Fortunately, unlike the case in other towns, they did not touch a single person from Neishtot. I think that it was thanks to the intervention of Mendel Winick, the Communist activist from our town. Deep down in his heart he still had a Jewish soul. In the evening, there was the Red House party. The commander of the Border Patrol, Soviet officers and soldiers, were among the people that attended. I was standing next to my friend Refael Lasky and his brother in law Shmuel Yehuda, when a “Runner” appeared suddenly and all the officers disappeared. We talked among ourselves about the hope that the messenger did not deliver bad news…

I went to sleep at the home of my grandfather Mordechai Yoselovitz (Mutte Daniels). I was asleep when one of the uncles, I think it was Asher (Asher'ke Mattis), woke me up and ordered me to go home because my parents may get worried… Now I heard for the first time, on the London News, that a war was about to break out within a few minutes, between Russia and Germany. I did not pay attention to my uncle's calls and begged him to let me sleep. Within a short time I woke up to the sounds of shots that came from Kulėðai. There was no doubt any more that something had happened at the border. I rushed home frightened; my parents were on the steps looking towards the border. Hurry… Hurry… I rushed the horses on to their wagons… War erupted.

My father refused to believe. Why all of a sudden?

He tried to speculate that they were just training to shoot. I was determined, and convinced my father to saddle the horses. We loaded the emergency boxes and rode off hurriedly. We escaped through the town travelling north in the direction of Kvėdarna. I remember the way the people in town stood there confused, someone was walking with a small suitcase… I can see in front of my eyes Lipa “the Melamed” (teacher), telling us: “go… go quickly and may G-D be with you”.

Shlomo Rabin asked us to take along his mute daughter. (She stayed with my parents until they got to Russia, and there at Yaroslav train station; she got off and never returned). We arrived at my grandfather's house in order to pick them up and take them with us. The house was empty and two guards stood there saying: “They have left”.

We continued traveling. As we passed Šiliškiai village, and here, we saw my grandfather Mordechai with Uncle Asher near the forest. When we inquired about the rest of the family, my grandfather said, frightened, that most of the children remained in the basement. Uncle Hillel went by bicycle to search for them and could not find them. Grandfather decided to go home and find his children.

I can still see in front of me the sight of my grandfather's anguish, turning white within a split second … he kissed us, gave us some money for the way, and walked home.. Where to?

We stood stunned. We had no idea what to decide or what to do. We saw the town people travelling to church. We asked if they knew what had happened. They told us that many Russian soldiers came through, that night, heading to the border. It crossed our minds that the Russian army may have managed to cross the border and possibly reach Tilsit, and we may be judged as defectors… We were desperate, not knowing what to do. There was utter silence around. Suddenly, we saw someone riding his bicycles nearing us. We recognized Leib Lasky. He was yelling to us:” hurry up, the Germans are one kilometer behind me”. There was no choice left. We hopped on to the wagon and continued to run away. We escaped to Russia.

The following are the people of Neishtot who joined the Red Army in the war against the Germans:

Izik Gold z”l was killed in February 1943 by Alexeyevka.Leib Lasky z”l, was killed in the summer of 1943, by Alexeyevka.

Isik Kruger z”l, killed.

Avraham Schneid is in Israel.

Yeshayahu Dubinsky is in Israel.

Yeshayahu Leibovitz is in Israel.

Shlomo Berlovitz is in Israel.

Zalman Traub is in Israel.

Mordechai Berlovitz z”l was killed by rioters in May 1946, in Neishtot.

…. Katz z”l was killed by rioters in Neishtot, in 1945.

Asher Yoselovitz was killed by rioters in Neishtot, in May 194 Binyamin Robinson lives in Israel.

Yisrael Kaganovitz (Ariogala), grandson of Chaim Lifshitz, was seen at the end of the war, in Kovno, Lithuania.

Dov Kalner is in Israel.

In October 1944 the “Lithuanian Division”, in which we served, was nearing Neishtot. I met, nearÐilalė, one of my town's people who served in another unit of that Division. He told me that ever since he heard about the destruction of Neishtot Jews, he vowed to revenge every single rioter that had participated in the killing of Neishtot Jews.

Our unit crossed the town of Vainutas, on our way to Neishtot. When we reached our town, I asked for permission to enter the town. After pleading repeatedly, I was granted permission. I found the city intact, filled with Russian army. It had remained intact because both, the Russian army, and later the German army, left it abruptly, without any battle. But it was horrible to see my home town, void of people... I could not find a living Jewish soul of the town, who could lament for the destruction, murder and annihilation… I met a few Lithuanians from the neighborhood, but when asked about what had happened during our absence, they ran away, fearing that we would take revenge of them. I did not know that our town's person had kept his vow and took revenge on the known murderous rioter, Razutis known for his part in the murder of the precious Neishtot Jews.

I left the town with a heavy heart, shattered soul, and in tears.

Following the German Defeat

In 1945, my parents returned from Russia empty handed and without any means to exist. The terrible war came to an end. I survived a large share of hardships that hit me during my service in the Red Army.

My parents returned via Vilna. We reunited after four years of a cruel separation. We had been separated at the Latvian- Estonia border. The young people were drafted to security jobs, and the older men, with the women of our family, were transported by train to Russia.) After weighing out their options, our parents decided to continue to Neishtot, to try to reestablish ourselves, and then move to a larger city.

Rafael Lasky lived in Neishtot. He had barely managed to return with a few others, after being saved from the awful Holocaust. In November 1945, I too, returned to Neishtot. Uncle Asher returned as well. We all lived in our grandfather Mordechai's house. My mother Necha, my father Shimon Aharon, I, my sisters Yocheved and Chana, Mordechai Berlowitz (handicapped) , and uncle Asher, all lived in the house. Refael Lasky lived separately. Mordechai Berlowitz worked in the City Council, and I worked with the local youth. These were the only jobs that we can get in Neishtot in 1945.

We planned to stay there for a short time and then move to Klaipėda / Memel. We traveled there a few times to find a place to live, but unfortunately it dragged on for a long time.

Many German soldiers that didn't manage to retreat with their units, hid in the surrounding forests. There were also civilians there. They were dedicated to the Germans and took part in the murder and destruction of Jews of Neishtot and nearby towns. Masquerading as Nationalists (Miškiniai), they continued to fight the Russian invader. They were now afraid of confrontation with the ordinary Soviet force, and therefore picked on civilians that had some duty in the Russian rule. This was easier for them and not as risky.

We heard rumors that they wanted to take revenge on us, that was after they had seen that even in spite of their “cleaning up” the city of Jews, Jews returned to live there once again. (Chutzpah. Wasn't it?!). We heard the rumors but could not believe that they would really carry out their plot.

On the eleventh of May 1946, at night, explosives placed in our home, exploded. The losses were terrible. Our mother Necha Berlowitz, my sister Chana Berlowitz, Uncle Asher Yoselowitz and Mordechai Berlowitz were killed. I was seriously injured. Fortunately, sister Yocheved was not injured, and my father was away from home and spared from injury.

Fifteen years later, I had the opportunity to read the killer's court file. There, I found the answer to the question why he murdered the Berlowitz family. His answer was clear cut: “I murdered the Jews so that Neishtot will be clear of them. We could not stand that the Jews wanted to return and root themselves in Neishtot again”.

Earlier, in the winter of 1946, Sarah Lapin, a refugee, had come to us to tell us that it may be possible to leave Russia. She asked that most importantly Mordechai Berlowitz, the handicapped, would go with us. We were apparently not ready psychologically, and we were also afraid that we would not be able to leave successfully. We decided to remain in Neishtot. That was what was meant to be our lot.

Today, the survivors of our family, have reunited and live in the Land of Israel, together with the veterans and the “new”, She'erit Hapleita”, remainder of the survivors [Holocaust Survivors].

Refael Lasky

On the twenty second of June, 1941, World War II broke out. We suddenly ran into German soldiers coming from the nearby border, to invade our city. They surrounded Neishtot from all directions. A number of the citizens tried to escape in the direction of Kvėdarna, but a few kilometers away, the Germans sent them back. I am especially reminded of the Berlowitz family, Lentin, our mother, and Yisrael Kaganovitz. My brother Leib Lasky managed to escape, riding a bicycle. He reached Riga and then Russia. He was drafted to the Russian army, and died in 1943, while serving in the Lithuanian Division.

On that same day, at ten o'clock in the morning, shots were sounded in town. The Germans assaulted the Jewish citizens, cruelly; they arrested everyone and locked them up in the town's German church. After a while, they released the women, but locked up the men, arguing that Jewish men had shot German soldiers. Immediately they transported to Germany Mendel Winick with his son, and Micha Alert who were suspected of Communist involvement. On the following day, the rest of the men were released too, but were not permitted to leave their homes. Within a short time, the men were drafted to a labor camp near the border, where they had to do back breaking work. It was grinding and humiliating.

On the nineteenth of July, 1941, they gathered all men to the shul courtyard and sent us to a camp in the direction of Vainutas. Lithuanians of the Šauliai organization, known to be disgraceful, were appointed to be our guards. Women, children, and ten men were left behind. I recall Hirsha Grossman, Nachman Gold, Hirsh'ke Yoselovitz, Laks Meloglen, Tzil'ke Berlowitz, and Leib'ke Lapin. Twenty nine of us were sent to Heidekrug, a German town across the border, to do oppressive work.

Then, Dr Shaw, a Nazi, came with SS men and began their operation. They shot people randomly, from close up, and killed them brutally.

In Heidekrug, they gave us very difficult and degrading jobs, in order to demean us in the eyes of the local German citizens. I was happy to meet my brothers Berel and Moshe'le there. We had lost contact in the course of the attacks on Jews in our town. In Heidekrug, we found out details about the shocking robbery, theft, and murder of Neishtot Jews, by Germans and their collaborators. The Germans had the priests gather all non-Jews into the churches. Then they heartlessly annihilated the women and children that were left. Tzal'ke Berlovitz, one of the boys, tried to sneak out and escape. The thugs chased him, shot him, and killed him on the spot.

That was the bitter end of our town and its Jewish people of blessed memory.

I, my two brothers, and the other tortured prisoners, continued to work in Heidekrug until the twenty fifth of July, 1943. From there they took us to Auschwitz, the notorious concentration camp. Binyamin Lapin and Mattis Gold were with us, together with another thirty Jews. We were there until Erev Rosh Hashana. From there, we were sent to Warsaw. In Warsaw, they kept us working in the ruins of the Jewish ghetto, cleaning the ruins and clearing them. The Germans transported all valuable materials to Germany.

During that time, the Typhus plague broke out and many died from this terrible illness. Very few of us remained alive; I, Lapin, Gold, Gloch, Yoselovitz, and Ber'ke Glass. We stayed in Warsaw until August 1944. Then they transferred the whole camp to forced labor in Germany. Gold and I were the only ones left, and they continued to have us clean the ruins.

It was at that time that we found out about the rise of a revolt of the Polish citizens around. I and Gold, found an opportunity to join the rebels and we helped them fight. But the Polish men did not have the strength to uphold their battle for a long time, and they were forced to disperse. Then, the Germans ordered everyone to come to register. Whoever would be found unregistered will be shot on the spot. Sixteen of us decide to hide from the Germans, in a bunker, under the ghetto ruins. It was in October 1943. That was where we managed to hide, in great pain and fear of the Germans, until the seventeenth of January 1945.

We scraped together some essentials, with some food, barely enough to sustain us for ten days. The Red Army was stationed in Prague, near Warsaw, at the time, and we thought that we would be liberated soon.

We made all efforts to stay strong, but when we ran out of basic food, we decided that each night four men would leave the bunker to see what is going on in the neighborhood. We discovered that the Germans had looted and collected all valuables and food, and transported everything to Germany. There were a few soldiers left in the city. We had some weapons for self-defense, if needed. We took turns each night, to go to search for some food to keep ourselves alive. That was how we found a well in the yard near the bunker, with polluted water, full of insects. We used a piece of cloth to filter the water, boiled it, and then, somehow, managed to drink it.

That was how we went on living, if you can call it living. We slept during the day, and went out to look for food at night. Our food usually included rice and something baked from flour.