|

|

|

[Page 71]

The Partisans

by Moshe Slutsky

Translation from Yiddish into Hebrew by Y. Moorstein

When the War broke out in 1939, I was serving in the 42nd Battalion of the Polish Army in Bialystok. From there, we were taken to Brest, the Germans attacked us, and we retreated to the Kobrin-Kobel road. It was there that we received word that the Red Army was attacking. Our command disbanded, but was able to provide us with documents, and we prepared to head for home.

From the time we reached Zelva, the Germans bombed the city heavily, and the city went up in flames. My family was uprooted and sent to a nearby village, but when it was captured by the Germans, they returned to the city. The Germans appointed “Abba Poupko” as the leader of the community. In July 1941, about twenty Nazi SS officers arrived, and they ordered all adult Jewish men to gather in the center of town, and to line up. In front of them, they raped a young woman, and then gave her 24 lashes. This scene was terrifying, and left a very deep impression. The head of the SS declared that if the Jews followed all the orders of the head of the community, they would not be beaten, and he immediately requested that all the teachers, accountants, rabbis, and anyone with an education step out of line. In answer to the question, “Why?” came the answer, “To do knowledge work.” They were taken to the Bereshko Forest and shot.

The Germans put the Jews to work at all sorts of labor, and in the process shot and killed many of them. On one day, the [German] leader sentenced seven Jews to be hanged. The execution was carried out publicly, in the marketplace, in front of all the residents of the town. Both Jews and non-Jews were ordered to build the gallows. The Germans murdered with “clean hands” according to their view, claiming that they were only hanging lawbreakers... the seven corpses were left hanging for three days.

I worked on breaking up stones for the road, and it was there that we discussed how to organize ourselves and how to obtain ammunition. Among the organizers were: my brother, Katriel, my cousin Nathan Slutsky, my uncle Hannan, Isaac Michal Kabintovsky, Abraham and Dov Loshovitz, Isser Selman (a man from Warsaw), Gorovitz, the three Zlotnitzky brothers, and several refugees from Lodz.

Nathan worked for the Germans as a locksmith, and managed to smuggle away a sub-machine gun with 500 rounds of ammunition. My father brought 3 rifles from the forest. We cleaned them, dug a ditch, and hid them.

On November 2, 1942 in the morning, the SS troops that came from Volkovysk surrounded us, demanded a list of all the Jews, and ordered us to report to the train station. We decided to flee the ghetto, and I was the first to leave the concentration point, and after me, came the rest of the band. In view of the fact that my sister had just undergone surgery, my father stayed behind to look after her. In all, we were ten men.

[Page 72]

As we crossed the Ruzhany road, the Germans strafed us with machine gun fire, and we scattered. In one of the places, I remained with my brother, cousin, and a Jew from Warsaw. We forded the Zelvianka River, and with nightfall, returned to Zelva. In the city, already there was not a Jew to be found. We dug up and found our ammunition, re-crossed the river, entered the forest and began our attempt to contact partisans. On our seventh day in the forest, we saw a wagon approaching us. We took cover by the side of the road, and when the wagon passed us, I ordered the occupants to stop. Four men jumped out of the wagon and identified themselves as partisans. To our surprise and elation, these were four men from Dereczin whom I knew: Gedaliah Basiak, Mishka Ogulnick, Mania Koblinsky, and Israel Koblinsky - all of whom subsequently were killed in combat as a result of sorties they led against the Germans. These were active fighters, in the “Bulak” partisan group from the Shchuchin command on the shores of the Shchara River. On their word, we were accepted by this group, and together we went to work, which turned out to be sabotaging the Warsaw-to-Moscow rail line that passed by Slonim. After implementing this task, the enemy opened fire on us, but we succeeded in reaching our base. The mission was carried out with great expertise.

At this time, there were 38 combatants in the group, all of them Jewish, except for the Head, Shubin. The commander of battalion one was Eliyahu Lifshovitz of Dereczin. Battalion two had Eliyahu Kobinsky from Volkovysk, awarded the Red Star and the Order of Lenin, and the command of the brigade of Chaim Moshe Lifshovitz, who fell in a siege in June 1944. His place was taken by Dr. Atlas from Lodz. This group distinguished itself by being so active, and was well known for its combativeness, and for carrying out exceptionally heroic missions.

That night, the division commander Valentin, and the group head Bulak arrived, and questioned me regarding my motives in coming into the forest, to save myself or to fight. And when I answered that I would not surrender the weapon I had in hand, they gave me a mission to obtain shells for their cannon. Five of us went out: my brother, my cousin Nathan, Mania Koblinsky, Moshe Ogulnick and I. We departed with two wagons - 80km to Zelva. Not far from our house stood a tank, and in it there were approximately one hundred shells. We received an order not to engage the enemy. We crossed the Warsaw-Moscow railroad tracks, and we reached the town of Bereshko, in the Zelva environs. We woke up a farmer, and ordered him to ferry us across the Zelvianka River. We warned him, that if he gave us away, we would shoot him on the spot. When we successfully crossed the river, we began to load the shells onto our wagons, but the noise of the wagon wheels on the thin roadbed, attracted the attention of the German sentries that were nearby, and they opened fire on us. We returned the fire immediately, in order to retire. By morning, we had managed to return as far as the farmer's house, and then to our camp. This was reported by the German command in their dispatches as having “successfully repulsed a partisan attack.” We began our preparations for the winter. To this end, we moved our camp to Volko Volya, a wide stretch of forest on the road to Zhitiel. I led and arranged for the construction of five houses that were 3 x 5 meters in cross section, and also a bakery.

On December 6, 1942 we were visited by the officers of the partisan division. During the somewhat festive reception held in their honor, they conveyed their impressions of the Jewish fighters. At the same time, the Germans opened up a broad general assault on us. We dug in on the banks of the Shchara River, and with every piece of artillery at our disposal we denied the Germans the ability to cross. After three days of fighting, Dr. Atlas from Lodz, who was the battalion head, was killed. He had organized our group, he was the spirit that breathed life into it, and was a model of courage. His motto was: anyone who survives is obligated to take revenge upon the Germans to the utmost of his ability. We could not fulfill his last wish, which was to bury him beside his parents. We buried him with full military honors in our camp in the “Borolum” partisan cemetery.

[Page 73]

In view of the fact that the strength of the German forces stood at forty thousand troops, and pressed us with its full might, we were forced back to the outskirts of Baranovich, where we also were ambushed by known forces. Because of this, we entered the forests around Slonim. In this period, contention broke out among the various partisan groups, particularly among the commanders, and our group suffered losses.

During the siege, the Jews suffered from hunger. Bulak forbade the Jewish officers from looking after the food supply. Despite this, Kobinsky and Lifshovitz sent men to bring food. When Bulak confiscated a Jewish partisan's ammunition, our leadership decided to move to the camp of Orlinsky, and it was at this time that Bulak shot two Jewish woman partisans, Shlovsky and Becker, and evicted several families as well. A similar incident occurred in the Avramov camp. They searched for Kobinsky and Benjamin Dombrowsky, but they succeeded in blending into the Shubin group. We decided to establish a new camp, a complement of five houses, each 5 x 10 meters in cross section, 1.7 meters high, and each window, 0.2 meters in height. Each house had an iron stove, and on the roof - snow for camouflage. In this fashion, we erected a hospital, a kitchen and a bathhouse. Most important of all was security, and in the forest, there were always security patrols.

With the assistance of a treasonous farmer, the Germans mounted an attack on our camp and succeeded in entering the bakery, but the workers, like Malshinsky, and Bela Bernstein, managed to escape, even after the Germans fired at them and wounded them. The partisans returned a furious attack, and the Germans in retreating, left many dead and wounded and they fell back. About thirty families from Dereczin lived in our area. In the tumult of the attack they started to run, and 16 of them were killed.

During the month of February, we derailed eight trains carrying battle ready troops. We were at a strength of 250 men in the attack on the village of Khatzivka, which harbored the “Samokhovsky” force, farmers who fought against the partisans as an auxiliary army to the Germans. We attacked from all sides, and our enemies fell by the sword, and afterwards we took what remained of their guns and ammunition. In the end, we put the village to the torch, and left it in ruins.

In March, Lifshovitz received orders to carry out a mission to destroy a food supply convoy that was being sent to provision the army in Dereczin. The orders were given also not to engage the enemy in battle. When we got to within seeing distance, we realized that we had gotten too far outside of the forest. We fell back to the village of Sluzhy on the banks of the Shchara River. At dawn, the Germans launched a major assault. Our leader Lifshovitz ordered us to cross the river on rafts and to set up defenses. Apart from rifles, we also had two machine guns, and with these, we were able to stall their advance. On the following day, the Germans bombarded us with cannon fire, and we were forced to retreat. From that point on, fighting broke out in the forest, and after suffering losses, the Germans retreated. At the end of the month, the Germans concentrated a large force in the area and besieged us. We began to fall back to the area of Slonim and Baranovich. We set up a camp of ten tents camouflaged with branches. From there, we began operations. We cut telephone lines and blew up a railroad bridge adjacent to Baranovich. We wiped out two companies, one was a supply company, and the other from Vlasov's army. The results: 5 dead, 3 captured, 2 mortars, 10 rifles with ammunition, and a lot of food. In the sector, there were 5 German armies in addition to the Vlasov battalions, but without armor (tanks), it was not possible to attack them frontally. In the village of Tvorog, there was a tank that was left behind by the Red Army. The mechanics of the tank were damaged, but a partisan among us repaired it, and we put it back into service. When we reached the banks of the Shchara River, the Germans attacked us with the help of Ukrainians. We managed to

[Page 74]

ford the river, despite the fact that we were in the heat of battle, and only after several days did we return to camp without casualties, even though we had been given up for lost.

In groups of ten men, among them Lifshovitz, Ogulnick, Basiak, Blizninsky, and I, we went out on missions, and we engineered the blowing up of trains, and of railroad track in several places. We reached the town of Rus, a distance of 50km from our base, in two wagons, and we attacked a cement factory. We eliminated the guards, and herded the workers outside, and put sixteen kilos of dynamite into the factory boiler system, destroying it completely. In this way, we eliminated production capacity equivalent to three trainloads a day.

In the summer of 1943, the Jewish group obtained the mission to destroy the Dereczin city hall, and to obtain supplies. Eighteen of us went out on this mission. After a basic scouting by a former resident of Dereczin, Joseph Blizninsky, fifteen men, supplied with dynamite and instructed in demolition, set up the charge on the best side of the building, and as we fell back, we attacked a supply convoy that was bringing provisions to the police camp at Ruda Jaworska.

From command headquarters, we received notification to carry out a mission: at 9:00AM, a supply convoy consisting of fifteen wagons loaded with foodstuffs and munitions will be on the road passing by the village of Sluzhy. There will be three units participating in the mission, and I was in number 2. Their role was to hide themselves about twenty meters off the road, give the convoy the opportunity to pass them, and to go into action only if the convoy attempted to retreat. Unit 1 was to wait for the convoy on the other side of the road, and Unit 3 was to lead the attack. In accordance with our timetable, we allowed the convoy to pass, and only when they reached the firing range of Unit 3, did that unit open fire, and the convoy escort began to fall back, and it was then that we got them in a withering crossfire, and after us, Unit 1 with fire and shouts of victory.

Results of the battle: 20 dead, 11 captured, all police. We brought all the spoils, food and ammunition to camp, and it consisted of: 5 heavy mortars, 2 light mortars, 15 rifles, 5 mortars, hand grenades, a large supply of bullets, and supplies for a large populace. As we reached our camp in triumph, the base commander greeted us with great pleasure. He immediately sent for 3 wagons from the village of Azyurky, and on them, he loaded 20 of the dead with the following note:

Honored Commissar!

We ask that you forgive the sender's untidy packaging. Next time we'll straighten out the mess!

Our leadership anticipated a sharp reaction by the Germans, and sure enough, the attack wasn't long in coming. At 12 o'clock a large force began a rifle attack on the village of Sluzhy and a part of the forest not far from our camp. They assumed we would return their fire, thereby revealing our positions, but instead, we held our fire, and they stopped their advance about two hundred meters from the village. In that location, a stream meandered by, and over it was a small bridge. We blew it up, and when the Germans began to try and ford the stream, we opened fire on them from all sides, and they started to retreat in panic, leaving behind a tank which we burned, many dead, wounded and prisoners. On our side, Moshe Ogulnick, Levit Maustrov, and Lipman were wounded. The prisoners were brought to camp. Some of them were shot immediately on the spot, and the rest after interrogation. After this incident, the Germans did not move supplies through this territory.

[Page 75]

One of the partisans caught his brother and brother-in-law, and turned them over to the commander, Bulak. They were shot by him for treason and spying.

After one operation, when the Germans sent in a punitive expedition against the village of Sluzhy that consisted of 300 men, our unit of 18 men was sent to meet them (this being an error made by headquarters). Needless to say, we didn't hold our ground for very long, and we beat a hasty retreat, but not before Fanya Lifshovitz from Dereczin was mortally wounded and died. There were 4 fighters from the Lifshovitz family: Eliak, a division commander, Chaim-Yehoshua, Gershon and their sister, Fanya. Fanya and Chaim-Yehoshua were killed in battle, while Gershon was wounded and remained an invalid. Not once did Fanya ever want to stay within the confines of the camp, and like her brothers, participated always in all the fighting. We brought Fanya back to camp, and buried her with full military honors in the presence of all the members of the camp in the partisan cemetery in the forest of Ostrov Borolum. Our unit there was called Победа [Pobeda] meaning, “Victory.”

We moved to a new location that was near the Shchara River, near Chornaya Kolonya. Our mission this time was to repair a tank and use it to attack the Germans in the area. This plan became known to the Germans, and in the month of September 1943, they attacked us with the objective of hitting the tank and destroying it. After the Germans captured the village of Peshchinka and burned it, we retreated and entered the forest. Our command then canceled the above mission, and we began to prepare for winter. We crossed the river and entered the forest of Dobrovshchin. Every unit in one camp set up dwellings and outhouses. My brother and I were the builders. Apart from the quarters for our section, we also built a hospital, bakery, kitchen and bathhouse. After we put up these buildings in the end of December, several additional partisan groups joined us, and they appointed officers to head new units. I was attached to section 172 which consisted of 4 divisions of mine layers and one which was administrative. Our mission was to sabotage the movement of the Germans on the Vilna road between Slonim and Krulevshchina.

In one operation, when we were advised to destroy the Ostrov camp, all three sections participated, 180 men. In the dead of the night we attacked, all the partisans, with unending fire. The Germans had their sleep interrupted, and after we dealt them losses in tens of dead, and many wounded, we took 26 prisoners, a great deal of booty, which included a cannon, 2 heavy mortars with two stands, many rifles, 45,000 rounds of ammunition, food, and a variety of other types of armament. We lost two men. After this attack, the Germans put us under siege, and with the help of Ukrainians and Byelorussians, sealed all the principal roads from the forest to the railroad tracks. They attempted to try and advance on our campsite. We allowed them to close in on us, but as soon as they reached firing range we opened fire on them and inflicted loss of life on them, and they fell back.

During the period when we carried out operations on the Vilna road, our section organized an attack on a supply convoy of 20 wagons loaded with armaments, clothing and food. This convoy was earmarked to supply the needs of the encampment at Krulevshchina, but all of this was captured. A month before the great offensive launched by the Red Army, the Germans made all preparations required in order to attack us and wipe us out. They sealed all the roads with a large army, and covered all the roads leading to the forest with tanks and cannon. Our command decided to move to the Niliebuki forest. On the third day, we reached the road leading to Zelva, and we opened an offensive in order to enable our force to advance. The fighting was extremely brutal. The commander, Avromov, was killed, as were Misha Ogulnick, Tuvia the Fighter, Shlovsky and his sister (another sister was killed by our leader, Bulak), and 4 other combatants. This enabled our force to reach the vicinity of Baranovich. Our crippled section ceased to exist. The survivors broke up into smaller units

[Page 76]

to facilitate logistics. Our new commander was Kanoplov. In the course of a month, we moved from place to place. At the end of June, we re-joined a unit of ours in the Niliebuki forest that had suffered casualties in the heavy fighting it had been obliged to undertake. It was in those battles that Chaim-Yehoshua Lifshovitz and his wife, Galia were killed, as were the commanders Yuvlev, Kostrankov, and Zerbtzov. We began to get ready for more operations.

On July 12 the Red Army reached us. The siege was lifted, and we advanced together with the Red Army. I was attached to the engineering corps, construction battalion 269 near the Svyslutz River, and we fought for over two days. In our advance, we approached the vicinity of Bialystok. There was heavy fighting there, but we carried out all the missions assigned to us. After these battles, the Germans retreated from Bialystok, and fortified themselves in the city of Choroszcz on the Narew River. Our army constructed iron drums within two days, and put boards across them, and our forces advanced on these boards. The Germans took heavy losses, but so did we. In our advance, we reached the city of Choroszcz on October 10, 1944. In the attack on the city of Makov I lost a leg.

Baranovich District July 16, 1944

|

Attached to this is a medical certificate because Moshe lost a leg in battle.

Alta and Ephraim (Foyka) Gelman

Translated by Y. Moorstein

We and our two children were among the few survivors when the Germans entered Poland as far as Bialystok, in accordance with the pact between Stalin and Hitler to partition Poland. Our city, Zelva, was captured by the Russians, and we began life under a Communist regime. The well-to-do, the Borzoi to the Communists, the Borodetzky, and Spector families, Moshe Lantzevitzky, and Wallstein were exiled to Siberia. Whoever couldn't prove that he was a worker, was not considered fit to receive gainful employment. I left to go Bialystok, and there, I received a Soviet visa, and I worked up until the time the Germans invaded Russia in June 1941. When I returned to Zelva, the Germans bombed the city. The houses were burned, and the city was left in ruins, along with eighty dead and wounded.

After several days, the Gestapo men arrived who then ordered all the men to report immediately to their leader. In that same instance, forty members of the town's intelligentsia were taken to the Bereshko Forest and shot to death. In this undertaking, the Germans were assisted by Polish youths who were deputized as police for this purpose. Starvation began to squeeze us. It was impossible to obtain a piece of bread, in view of the fact that everything had been burned and there was nothing to offer the farmers in the way of an exchange of value. When seven butchers were caught on the suspicion of smuggling meat, all the Jews, and the rest of the residents were compelled to watch them hung in the marketplace. After the Succoth holiday, all the Jews were deported, along with those living in the surrounding villages around Volkovysk, with incredible overcrowding, and under inhuman circumstances into colonies, and from there -- to the gas ovens of Treblinka.

We lived in one of the cellars until the Germans came on July 6, 1941. When the Germans arrived, Alta and I packed our belongings, and with our two daughters, headed for Dereczin. There were still houses standing in this city. We lived there for about seven months. When they started to organize a ghetto in that place, we returned to Zelva, but were it not for the fact that we were not registered in the list of Jewish residents, we would have been marked for death. Consequently, we wandered to Volkovysk, and there I was given heavy work building roads. I worked about 14 hours a day. We found a place to live in a house with 5 other families. When they were getting ready to deport the Jews from this place, we managed to sneak out of the city at night. After 10 days of wandering, we crossed the Zelvianka River and reached the forests between Dereczin and Zhitiel. We had several adventures until we met up with a number of partisans, who brought us to the camp of “Bulak”, in which 150 people lived, among them families from Dereczin, the brothers, Moshe and Katriel and their cousin, Nathan Slutsky from Zelva. We were accepted into the camp that operated under martial law, and we lived there for 26 months. Our Jewish brigade undertook sabotage operations such as blowing up trains and railroad tracks in the midst of heavy fighting. In the fighting against the Germans, losses ran about eighty percent among us, over the years. The details about this dreadful fighting, and the revenge we exacted for our dear ones, are covered in Moshe Slutsky's narrative.

In July 14, 1944 we were liberated by the Red Army, and we left... to return home to our city. There, we found only heaps of ruin. From all the houses, schools and the Great Synagogue, all that remained standing was one wall...there was no place to bed down for a night. The gentiles were certainly not happy to see us. They were afraid that we might perhaps recognize the property of Jews in their possession. To our surprise and joy, we found Mordechai (Mottel) Loshovitz in Zelva, who survived by a miracle, and arrived to this shattering sight of Zelva. We did what we could for him. In

[Page 78]

September 1945, we left our town, and reached Salzburg-Linz (Austria) by illegal means. We lived in Austria until 1951. From there, we emigrated to the United States, where we raised our family and lived to see our grandchildren come into the world.

We are extremely fortunate to have survived, but our hearts ache for those victims, who gave their lives in sanctified martyrdom.

by Mordechai Loshovitz

I was drafted into the Polish Army prior to the outbreak of the war in 1939. In the fighting against the Germans at Chorny-Bor, I suddenly heard someone calling me by my name. In an ambulance, lay Shmuel Konkevitz, a friend from home, wounded by a bullet that lodged close to his heart, and no one was attending to him. He begged me to convey news of his condition to his family, and his wife, whom he had just married two months previously, when a heavy bombardment started, and we were separated.

After several days of heavy fighting in the vicinity of Lomza, our camp fell apart, and I found myself a prisoner of war. In the concentration camp for prisoners, which was organized in threes, I saw Isaac Michal Kabintovsky, one of my relatives, in one of the rows. I ran to join him, but received blows to the head from a cudgel, and was forced to return to my place. From that time on, I never saw him again. There were many, many prisoners in the camp. That night, a horse whinnied, and the Germans thought it was the beginning of a prison break, and they opened fire. The screams of the dying and wounded reached the gates of heaven itself. In the morning, the place looked like a slaughterhouse. One of the wounded was Jonah Garzabsky, whom we managed to drag over to us. The Germans transported us to Germany where we were interned at Stalag One which housed about six thousand prisoners. In the camp, I also encountered Leizer, the brother of Jonah. Both of them were ultimately killed in the Holocaust. Shmuel Varinsky, another townsman of mine, was left with me. We lived together for a year and a half. Through the efforts of the Red Cross, I received one letter from home, and a food package.

They planned to transport us to the Bilew Podolski camp that had Ukrainian guards, where living conditions were said to be sheer hell. From what we heard, they used to take the inmates to concentration camps from there. On the way there, I jumped off the train and began to wander, at peril to my life. I changed my clothes so I would look like a gentile, and in this manner, I reached a village near Brest where I was taken on and given work as a carpenter. In the entire area that I wandered through I did not see a single Jew.

In September 1942, they became aware that I was Jewish, and it was then that I fled to the forest and hid. I dug ditches and lived in them. I stole potatoes from the yards of farmers; occasionally I succeeded in trapping a rabbit, and it was only through sheer instinct that I managed to survive.

In the summer of 1944, the Russians broke through. I emerged from hiding on to the road -- to freedom, with the feeling that I had somehow managed to overcome the Germans. With my inner ear, I heard the bells of my home town, Zelva, but my path was laden with pitfalls. After considerable tribulation, I finally did reach Zelva, but to my great sadness, I did not find even a single Jew there; not a single house was left standing. Only one wall of the Great Synagogue still stood in place. The

[Page 79]

cemetery, the roads and streets, were all covered with wild undergrowth.

From one of the houses that had somehow managed to survive in town, a gentile emerged whom I knew, and he invited me into his dwelling. From him, I learned of the terror that befell our loved ones before they were deported to Volkovysk and from there -- to Treblinka. In this gentile's house, I saw candlesticks, tablecloths and bedding...

The entire city was consumed in flames from the very first bombardment. They (The Germans) killed off the intelligentsia immediately, and afterwards, in their madness, they totally cleaned out the Jews from the city. The Germans also hung five Jews, among them, Abba Poupko, the community leader, David Vishnivitzky, and Noznitzky. The only one who survived was Malka Lifshitz, who had taken ill, and was confined to bed. When the Germans found her, they butchered her in an unusually cruel manner. I was the only Jew in Zelva until the return of Shayna Loshovitz, Moshe Slutsky, and Foyka Gelman, the latter being the only one to return with his family, excepting Shayna Loshovitz. Our focus was to reach the Holy Land. I got there in 1945 by illegal means.

by Shmuel Kaninovitz

My life as a youngster was not materially different from that of other young boys my age. I was a member of Hashomer HaTza'ir and participated in a number of Zionist activities.

In February 1938 I was drafted into the Polish army, and in May 1939, my company was assigned to the German frontier. We camped down there, and dug trenches to fortify our positions. On September 3, a dark night, the Germans attacked us with rifles and bayonets, and we returned the fight with vigor. In the battle, I was hit by a dum-dum bullet in the leg, and fell wounded to the ground. Our company dispersed all over the countryside, and I quickly found myself a prisoner in a field hospital in the city of Kutno. We received notification that anyone who wanted to, would receive a discharge that would enable him to go home. I switched plans and reached Zelva at the end of October after considerably dangerous travels. It was there that I learned of our comrades missing in action, Jarnovsky, Loshovitz and Novikovsky.

In May 1939, I was drafted into the Russian Army at Baranovich, and when the enemy began to gain the upper hand in the war between the Russians and the Germans, I was given the opportunity to go home, or to continue with the withdrawal of the Russian forces, and it was in this manner that I reached Smolensk. I was outfitted for battle, and was thrown into brutal fighting. Out of my unit of 25 men, only 2 survived, and 4 were wounded, and I was among them. The conquering Germans finished off their job by massacring anyone they found alive. I lay without moving among the battle casualties, and when one of the Germans stepped on me, he must have decided that it was not worth wasting a bullet on me, and that's how I was saved from a hell that is difficult even to describe. I had been wounded in the arm, and I was taken into a unit that brought me to a military hospital in Novosibirsk. There, I was ordered to set down my memoirs in writing. In those writings, I mentioned that I has served in the Polish army. Because of this, the N.K.V.D. detained me, and accused me of being a German spy. It did me no good to explain that I was Jewish, and that the Germans were exterminating us. My sentence was handed down in a matter of seconds: exile to Siberia for seven years.

[Page 80]

In view of the fact that our food intake was 400 grams of bread a day, I became a mere shadow of my former self. My weight dropped to 42kg, until after two years, I made the acquaintance of a cook who had me assigned as his assistant in the kitchen. From that point on, I no longer suffered hunger. On the contrary, I was in a position to help others. In 1944, I recognized a young Jewish man from Poland who had managed to establish connections in the Holy Land. I remembered my sister's address in Haifa, and I let them know of my existence. They started to send me packages, and made efforts to have me freed from the labor camp in Novosibirsk, but instead of letting me go, I was sent to Kolyma, above the Arctic Circle where the temperature falls to fifty degrees below zero. They gave us the job of mining for gold at a depth of 20 meters below ground, on meager rations and under conditions so difficult that they were unbearable. I managed to hold on until 1947, but at that point I began to fail. My legs wouldn't respond, my eyes closed up, and I lost my ability to see. It was at this time that a rescuing angel appeared to me in the form of a Russian, who found some hot soup that he fed to me. Slowly, but surely, I regained my strength. After this, they assigned me to clean out offices.

The camp commandants, Iosif Bobrov, Kovalevsky, Tchlitzky, and Shaklirsky were Jewish. I told them my story, and how I had gotten there. With their help, and through a long, tortuous journey, I managed to finally reach our own dear, dear Land!!!

by Faygel Gerber

Abstracted from Yiddish by Y. Moorstein

What I experienced during the war was shattering and terrifying, until I was rescued.

My brother, Isaac Nahum, went to Vilna to study at a Yeshivah. Several days before the outbreak of the war, I left to join him at his urging, but when I arrived, I no longer was able to locate him. The Russians had sent him to Siberia. We learned that the Germans had begun a terrifying bombardment of Zelva. Because of this knowledge, I did not return there. I was rounded up with the Jews (of Vilna) and put into a ghetto. Here, the Germans ordered us to line up in rows, and with terrible blows raining down on us, they separated part of us, myself among them, and the remainder were taken outside the city and ordered to dig pits, and over them, thousands of Jews were shot to death. The cries of the victims must surely have reached the ends of the earth.

Left alone, with no means of support, I joined up with a woman, a mother with two children, whose husband had been taken outside the city to be killed. Together, we sought some means to escape, and while we were able to get out and reach the city of Varanova, there too, we found slaughter. Somehow, we managed to flee to the village of Rezin, and you can imagine how happy I was to find my townsman, Joseph Krinsovsky there, who afterwards was killed in the ghetto. We hid on a roof along with several other Jews. After the Germans finished their job of exterminating everyone at hand, they began to look for surviving stragglers. We had a baby with us that burst out crying, and his parents could not make him keep quiet. With my own eyes, I saw his father smother him to death...

In the night, we slipped away from our hideout, and reached a factory building. We stopped to rest a little, and a farmer passed by who took pity on us, and invited us to hide in the yard of his house. He even brought us bread and milk. From here we began to wander. We were warned not to try and

[Page 81]

return to Vilna. Again, we were fortunate with a farmer, certainly one of the righteous people in this world, who dug a pit behind his house and “settled” us in it. Even though he did not have many means, his wife and daughter cared for us and fed us, and when the snows came and covered the pit, the daughter walked through the snow in order to offer us assistance. Sanitary conditions under these circumstances were, needless to say, not very good. My whole body was covered in sores. More than once I prayed for death to finally come and take me. The farmer's family, whose name was Adamovitz, lived very frugally, yet it shared with us whatever it had. You should understand that we still correspond with this family, and from time to time I send them packages.

I traveled to Zelva after we were liberated, and all I found there was destruction and ruins. There were only a few houses left standing in the city...

It is our obligation to do all we can to preserve the sacred memory of our dear ones who perished.

I married Moshe Yarkonsky, he also was a Holocaust survivor, and together we emigrated to the U.S. where we had relatives who lived in New York. We have a son and a daughter.

by Sandor Spector

Translated from Yiddish by Y. Moorstein

In 1930, I opened a warehouse for building supplies in Grokhov Warsaw, in which twenty laborers worked daily, who were members of the Grokhov community. When the war broke out in 1939, I left Warsaw together with the chief accountant, Ze'ev Varnivky, but we got separated along the way, and alone, after great difficulties, I reached Zelva. At the same time, my brothers, Jacob and Shalom, returned from the army, and my parents were very happy. In 1940, my younger brother, Shalom went to Warsaw because he could pass for a gentile by his appearance. After a while, he wrote that I should come. When I got to Warsaw, it was still possible to live there. We were permitted to live among the Christian population provided we tied a blue and white band on our arms.

The Judenrat of the ghetto was held responsible for providing hundreds of laborers every day, and they were given bread for their work. This condition persisted until 1942. At that time orders were received to produce 10,000 people a day and to march them to a field. From there, they were taken to an unknown destination. When the head of the Jewish community, Chernikov, became aware that the Jewish people were being exterminated, he committed suicide. Had he reacted differently, and warned the people, it is possible that many Jews would have survived and joined the partisans and others who were rescued.

My brother, Shalom, couldn't stand the predations of the general populace and he left, going to a small town called Rambrotov, provisioned with silver. We made up to meet in a certain place on the following day, but when I got to the rendezvous point, there was not even a trace of Jews. They had all been transported to Treblinka. I got in touch with several members of the Polish police who were known to me and of good character, and made a request for them to try and get him out of there, but their answer to me was that it was impossible. No one returns from that place. I then went to the trouble of obtaining a hacksaw that could cut steel, having decided, that if I ever got put on such a train, I would be able to cut my way through the train railings and jump off, and that's exactly what eventually happened. When I was loaded into a train car, I immediately began to saw the railings, and

[Page 82]

when the train slowed up after leaving a station, I jumped off. This was at night, and I continued to lie absolutely still. In the morning, a farmer found me, and took me to his home, fed me, and refused to take any payment from me. He pointed out the way to the train station, and that was the way I reached Grokhov. I turned to several people whom I knew, and asked them to take me in, but they were too frightened to do this. I recalled a Polish acquaintance who lived several kilometers from the village, and I went to him. His wife took me in, because, in the meantime, her husband had been sentenced to two years in prison. I offered to pay her a suitable sum of money for her to be able to provide me with sustenance, and she agreed to do this. I remained in hiding with her for about 18 months until the Red Army reached us on August 18. One of the officers was a Jew, and I became friendly with him. He told me that he hadn't encountered a single Jew along the entire way he had come.

My brother, Shalom, who was transported to Treblinka, was put to work there gathering together the valuables taken from those to be executed. All of these valuables were then loaded into train cars destined for Warsaw, and from there to Germany. In one of these round trips, when he was loading all this booty into the train car, he managed to hide himself in the car and didn't return to the camp, and when the train reached Warsaw, he jumped off, and in this manner, he too was saved, and Poles helped him. Yes, there were some like that too...

My parents survived by virtue of being exiled to Siberia during the days when the Communist regime had control in Zelva. My father died in Siberia.

Today we live in Melbourne, Australia.

by Avraham Lapin

In 1945, I left Russia on my way to Poland, in the hopes I would find some members of my family that remained in Poland before the war, but my hope was in vain. I reached Poland by train. We disembarked in the sector of Germany that was ceded to Poland, at the city of Shvednitz. There, we organized ourselves into a group that had the objective of one day emigrating to the Holy Land. In a matter of a few months, I was sent to Lodz, where I participated in training for group leadership, and after I finished the course, I was sent to head a branch of the Irgun in the city of Szczeczin. One day, Zvi Natzar arrived, who was an officer and representative of the Haganah in the Holy Land, and he deputized me along with a number of my colleagues, to organize the infiltration of Jews into the Holy Land by all sorts of illegal means.

At the same time, the number of Jews that were uncovered and identified to the Central Jewish Committee in Poland, established after the liberation, began to grow. In the first count, 80,000 survivors were found out of a population of three and one half million, and it was necessary to evacuate them out of Poland, but first, we had to get them organized.

The emissaries who came from the Holy Land, together with the existing workers on site, established in the German sector ceded to Poland, resettlement camps for adults, young people and children. The camps were built with abandoned German materiel. The Joint Distribution Committee took responsibility for providing food and clothing, While we, the workers and evacuation agents prepared them for the daring evacuation to come.

[Page 83]

As it happened, many Poles concealed Jewish children in monasteries, in villages, and other hiding places, in order that these children be caused to embrace the Christian faith, but we exercised every measure to find these children, and to bring them to the gathering places for Jews, and from there, we took them in trucks out of Poland by illegal means.

The Communist regime viewed our efforts on behalf of the Jews favorably. The regime had its own problems to deal with. It had the problem of trying to reconstitute a ruined nation, to care for the wounded, and repatriate refugees returning from Russia. There were incidents where the Poles attacked our settlements and even killed Jews. The Polish police authority, which included people who were greatly ashamed by these incidents, supplied the people in these settlements, and even gave them arms to defend themselves. The police leadership was not disposed to assuming responsibility for our protection in the face of these bands who preyed on us. With all this, they also never considered the idea of these Jews departing Poland.

The evacuation leadership, consisting of Zvi Natzar and his staff, who were responsible for bringing all the Jews to staging centers, also were responsible for finding the various means by which the people could be taken out. Access through Czechoslovakia was closed off. The Poles prevented any exit, and the Czechs denied entry. We found a gateway into Germany through the city of Szczeczin. The essential means of escape were set up with the help of the Russian Army that occupied Poland. By paying them heavy sums, they evacuated Jews using their train transports, but it became rapidly clear that even after having taken bribes, they were not averse to plundering the Jews, and there were even instances of murder.

The evacuation leadership obtained vehicular transport, and used this to evacuate Jews, but unfortunately, even this means was cut off when the Russian secret police uncovered a large contingent of refugees in the process of being smuggled out. They were exiled to Russia, where they were sentenced to long prison terms. There were many dangers hanging over us, and those whom we asked to provide us with help.

A terrible thing came to light in 1946 in the Polish town of Kleitz where a cluster of 40 Jewish refugees was found in the community house, comprised of old people, women and children. Members of the police arrived there, and demanded that the Jews turn over the arms in their possession that they were using to protect themselves, claiming that this was necessary in the name of security. After several hours, a mob of undisciplined rabble descended on this group of Jews, who were now defenseless, and killed 18 of them with knives, axes and staves, while many others were wounded. On that same day, Antak Zuckerman (may he rest in peace), representative of Polish Jewry, met with Maryan Sapikhalsky, the Polish Defense Minister. Antak described to him the very difficult circumstances confronting the Jews in Poland, after what had happened to them, and after they had managed to survive Hitler's extermination plan.

I was of the impression that the slaughter at Kleitz caused a change in attitude by the Polish regime toward all those engaged in evacuating Jews from Poland. I recall that the Polish-Czech border was opened, and every night we would take 4 or 5 truckloads full of Jews to Czechoslovakia, and from there to Austria. This was a successful period for us.

In 1947, I was taken to Italy (our operations center) along with some other members of the evacuation staff. Our objective was to assemble the Jews of Poland, Rumania, and Czechoslovakia that had been gathered into a variety of camps in Italy, and transport them in sealed freight trucks

[Page 84]

to the ports. There, ships were anchored whose destination was the land of Israel. We worked day and night, Saturdays and holidays. I recall that on more than one occasion, when we were ferrying the refugees out to the ships in small rubber craft, a distance of about 2 kilometers, a sea storm would blow up and the small craft capsized and the Jews raised a terrible clamor of screaming and yelling. The screams frightened us, because we were apprehensive lest our activities be discovered by the Italian authorities, but despite the difficult and dangerous circumstances, we achieved our goals with room to spare.

by Sima Borodetska

I am the daughter of the late Herzl and Rachel Borodetsky of Zelva. My father was the son of Shmuel Borodetsky of Zelva. My mother was the daughter of the last Rabbi of Slonim up to World War II, Rabbi Judah Leib Fein, ז”ל_, who was brutally put to death at the hands of the murderous Germans and their accomplices, may their names be eradicated.

In Zelva, my father owned a sawmill, a grain mill that he inherited from his father, and an electric power plant he built to provide electricity to the town and its environs. We owned a gorgeous villa full of beautiful things. Many people visited us, and who were only too happy to be guests in our home. In the summertime, my mother would send me and my twin sister to the health spa in Bereshko that was near Zelva. Our governess, Zhenya, would accompany us there. We owned 4 villas there, and our relatives also used to come to visit us there. My mother and my oldest brother, Jacob, would travel to a somewhat more distant health spa.

My father had university training. He was a graduate in pharmacy and business administration. My mother had high school education, and had completed a course of study at a Gymnasium. We were three children at home. My oldest brother, Jacob, may he rest in peace, who studied at the Gymnasium in Slonim, my sister, and I who attended a public school in Zelva. My father and mother helped many people. Each one helped in his own special way. My father's employees were fond of him because of his good relationship with them. Our life evolved with good fortune and plenty until the outbreak of the war when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939. The sawmill and the grain mill were burned. Only the electric power plant remained.

In 1940, the Russians occupied Zelva. Many Jewish refugees from the towns captured by the Germans fled to the areas under the control of the Russian Army. In a short time, the Russians detained my father, may he rest in peace, in the city of Kobel. From there, he was sent to a concentration camp far into Siberia, Ost-Okhta, and he died there in January 1942.

Many Jewish refugees also reached Zelva, who settled down in public and private places. Several of these refugee families lived with us as well. After a while, they installed two commissars from Moscow in our home, and armed soldiers guarded them 24 hours a day. After the commissars left, they came to us, and told my parents that they had to prepare to evacuate our home, leaving all its contents behind, at a specific time. We moved, at that time, to live in the home of the Mansky family, and we stayed there up to the day in 1940 when they sent us to Siberia. My mother had a sister in Moscow, who when she found out that we were in Siberia, immediately sent us financial assistance and packages. One day, she personally appeared from Moscow with two suitcases full of all sorts of good things. She also brought two cameras. One had a 5-second shutter speed, and the other a standard

[Page 85]

speed, along with a lot of photographic supplies. My mother learned to take pictures from a small pamphlet that was attached, and she photographed many people at no charge, just to be able to acquire the skill. Afterwards, she worked as a photographer for several months, and my brother assisted her with developing the prints.

After returning to Moscow, my aunt travelled to Slonim with her little daughter Zhenya, to visit her father, the late Rabbi Fein, and her brother whom she hadn't seen in many years. When Hitler invaded Russia in 1941, my aunt did not manage to get out of there in time with her little daughter, and return to Moscow. She was seized in Slonim, together with her daughter, with her mother, the Rebbetzin, and our uncle, as described in the Memorial Book of the Survivors of Slonim.

In Siberia, our mother was very active in her concern for us. She drove herself with all her might, and looked after us in every respect. My brother, Jacob, also helped a lot. There were times that we went hungry, and there were times when we had enough to eat. If we managed to have a pot with a reasonable amount of potatoes, well, then we had something to eat after all.

The cold was unbearable, several tens of degrees below zero. There were gale-like winds that blew through the place, called buranyii [Бураный]. With the onset of such a wind, it would suddenly get dark in the middle of the day, and it wasn't possible to see your the way to get home. A person who was not indoors, and happened to be out of the city, would freeze to death from the cold.

My brother Jacob completed his Gymnasium studies in Siberia, and even my sister and I studied in a regular school. After graduation, my brother worked at appointed job in an office. It was not possible to survive on his salary, because a pail of potatoes alone cost several months worth of his salary. During the war, we also received packages from America, which were sent by my mother's uncle, Rabbi Kosolwitz of New York. We also received packages from Israel occasionally. These packages contained clothing, foodstuffs, vegetables, and other provisions. This was of tremendous help to us.

In 1946, we were given an amnesty, because we, as citizens of Poland, were entitled to return home to Poland. We lived in a commune in the city of Voroltava for several months. Together with the rest of the commune membership, we crossed the border into Czechoslovakia, from there to Vienna in Austria, from Austria to Germany, and from Germany back to Austria. From Austria, we went to Italy over the Alps. We lived in Milan, and after a while, in 1948, we emigrated to Israel from Naples. My mother passed away in Israel a couple of years ago.

As to my brother Jacob, may he rest in peace, there were so many good things about him, you could divide his qualities up among many people. He was handsome, good-hearted, diligent, he was very capable, happy, witty, he stood out in any group, and loved to be helpful with all his might. We were proud of him, and we admired him greatly. He fought against the Germans, and was wounded three times. The last letter we received from my brother Jacob was from Konigsberg, on March 3, 1945. The city had changed hands several times. In his letter, he wrote:

“Mother, I am going into battle. If you receive letters from me, you will know I am still alive”.

Two days later, on March 5, 1945, we received a letter from my brother's friend, who advised us that my brother Jacob had been lightly wounded, even though an army officer wrote to us that he had

[Page 86]

been heavily wounded in battle, and that they had sent him to a hospital in the Konigsberg area. The officer specified the address of the hospital. My mother immediately sent a letter to that very hospital, and they answered us that my brother Jacob never got there at all. He was believed to have disappeared - missing in action.

I am obliged to cite at least one of my brother Jacob's letters, in which he wrote that after one battle with the Germans, he was separated from the Russian soldiers who fought beside him, and he was left alone. As he was searching for the Russian soldiers, he sensed the presence of two German soldiers, hiding at the side of one of the houses in the area. My brother understood, that if he didn't face them and confront them, they would kill him, so he approached them with a show of confidence, and ordered them to get their hands up. The Germans figured that he was apparently not alone, so they complied, and in this manner, he herded them off until he found the Russian soldiers.

by Joseph Kaplan (U.S.A.)

Translated from English by Aharon Freidin

The following is a description of my life from the time I completed my studies at the Herzliya Gymnasium in Volkovysk in 1939 until I came the United States in 1941:

During this period of time, I experienced very great difficulties, as did all the Jews of Poland prior to the onset of the Second World War. I had to struggle with a difficult and terrible future before I could achieve a situation to my liking. To my good fortune, my sister, Lillian, reached America six years before I did, and she was assisted by Mottel Perlmutter, who had reached America in 1929. Both of them looked after obtaining visas for me to enable me to continue my studies in the United States. From September 1, 1939 when I was in Zelva for several months with my father and sister Beileh, I attempted to flee to Vilna, which at that time was in Lithuania. I was hoping to receive the visa there, that had been bought for me. In that city, about 10,000 Jews had gathered from all corners of Poland. At the end of 1939, I succeeded in reaching Vilna together with young Jewish people, and among them was Isaac Gerber. After staying there for several months, and after many efforts on my sister's part, finally, the visa to America arrived. In those days, there were no conventional means to reach America. After further waiting and delay in that place for months, the Russians opened the Trans-Siberian Railroad with which it was possible to reach Japan. In September 1940, I boarded the train in Vilna together with 3 other young Jews who were also leaving Poland, and our objective was to reach The United States. We spent one day in Moscow, and then boarded the Trans-Siberian Railroad. We travelled on the train for seven days to Vladivostok, and after a week's wait, we boarded a Japanese ship and reached Japan. There, we also stayed for a couple of months, and after many additional efforts by my sister to renew and extend my visa, I reached Seattle, Washington in January 1941. From there, I travelled for four days after which, at long last, I reached New York, and that is how my long journey, full of hardship, from Zelva to the U.S. finally ended.

by Yitzhak Shalev

(Does each Nation and Human Being Have a Fate in Life?)

In the summer of 1938, I was on the way from the town of Hurna to Zelva. Because of the deep sand, I walked on foot at the side of the road, with my bicycle at my side. A farmer was walking on the same road. In the course of a conversation we struck up, he told me about a book in his possession that had been passed down in his family from generation to generation. The book was written in the Russian language, and contained prophecies on events to occur in the future. This farmer had predicted the outbreak of the First World War before it happened. On what was to occur in the future, the book said the following: a nation will rise in the West that will assert its dominance over several other nations (“this is undoubtedly Germany”, added the farmer). After this, the nation from the West will attack a nation found in the East, a nation that does not believe in God (безвжный народ [byezbozhnii narod]). The Western force will capture a large part of the territory of the nation to the East. It will capture the entire grain producing land of the Eastern nation (“this is the Ukraine”, said the farmer, by way of clarification). In the end, the nation of the East will assemble a large and overwhelming force of its own, it will throw off the force from the West, and liberate its territory from the hands of the conquerors. The war will be terrifying. Over you, will fly birds of steel, and they will destroy your cities (“so it was written”). One capitol city will be totally destroyed, and the dead will roll in the streets, and there will be no one to bury them (“that, it seems, will be Rome”, said the farmer). It appears that in this instance, the farmer erred. The description was more apt to Warsaw.

It will be the Jews who will suffer the most in this war. Out of 100 Jews, only 11 will survive (“that is what is written”).

“According to all the signs, this war is about to break out,” the farmer said. “I advise you to sell everything you own, and leave Poland. Travel to any and all lands where there is passage, to an ocean or sea that you can reach. But, if you are unable to leave Poland, and the war breaks out, you must travel to the East (На Восток [Na Vostok]), and not to the West. Because, in the book it is written that Jews who flee to the East will not perish from hunger, and will live. The Jew that flees to the West will not return, that is what is written..”.

When I reached Zelva, I went to my aunt. I told her about my encounter with the farmer. She told me that she knew this farmer; that many knew him. His name was Tarlokov, and she knew all of his stories. He argued and advised, in each store and Jewish home that he entered, that everything should be sold, and to leave Poland, because the Jewish people of that land stood on the brink of a great and terrible calamity. My aunt dismissed his warnings sarcastically: A Nayer Novee - behold, a new prophet! Are there now gentiles among the prophets?! And I also relegated the farmer's stories to the category of mystic tales and legends that one hears from time to time and forgets. And after a while, I stopped thinking about the encounter.

In 1941, when the war broke out between Germany and Russia, I was working in the city of Krulevshchina. In accordance with the orders for mobilization, I was to present myself at the office of the commanding officer of the city. At that place, companies of 20 to 30 men were drafted and organized and sent to Slonim. I was in the last company. The commander of the city, who recognized me from my position at the bank, appointed me as head of my company, and gave me the files of the

[Page 88]

draftees. Our objective was to reach Slonim by foot, and present ourselves to the commander of that city. I decided to take my bicycle, and with the consent of the company, it was up to me to reach Slonim before them and to verify what awaited us in that city. On the way, I encountered a senior Soviet official returning from Slonim. He recognized me from my job as well. When I told him where I was heading, he ordered me to turn back, with the draftees, and to advise the commanding officer on his authority to cease sending men to Slonim, because the city had been bombed by the Germans and the commander of the city had abandoned his post. I turned back, and advised the men of the company to do likewise. When I reached the office of the commanding officer I did not even recognize the place. Everything was packed, tied up and packaged for shipment. The officers ran about in great confusion and fright and were in a hurry to leave the city. I reported to the commanding officer of the city, and asked what I was to do. The answer was: “I can give you neither orders nor advice. You must decide what to do yourselves.” I left the files of the draftees on one of the tables, I took out my own file, and left the building.

Chaos reigned in the streets. The Soviet Command ran helter-skelter, and concerned itself with logistics to leave the city. The local population was docile and passive, and waited for events to unfold.

I set my sights on Zelva. Here I was, again a free man, discharged from the Red Army draft. Once again, I will be among friends, dear ones, and relatives. Our home, commandeered by the Russians, would revert to my ownership (I did not work in Krulevshchina out of my good will). The fear of the Germans, I thought, was probably exaggerated. After all, everyone used to tell, in the First World War the Germans got along very well with the Jewish population. In a conversation with my aunt (who was married to David Vishnivisky), she told me once: “If war breaks out, and the Germans come, we have nothing to fear from them. They will probably relate with understanding to all this, that the Russians took over our homes.” I, agreed with her assessment.

After some deliberation, I got on my bicycle in rather good spirits, and headed for Zelva. On the way, I came across a Russian family, with packs on their backs, moving with great haste down the road. In response to my question, “where are you heading?”, a 15 year-old boy, bringing up the rear answered me that they were fleeing to the East, На Восток (Na Vostok).

I stopped cold. I stayed in that spot for a moment. These two words had an electric effect on me. На Восток I said to myself. These are precisely the words that I heard from the farmer three years ago in the summer! This is the war he predicted! All the words of the farmer rushed back into my memory, every word, every sentence rang in my ear, as if I were hearing them right now:

“From every 100 Jews there will remain only 11 living! Whosoever will flee to the East (Na Vostok) will not perish from hunger, but will remain alive. A Jew who will go to the West will not return”.

Everything in me changed. All my thoughts of Zelva, friends, dear ones, relatives, the house I would reclaim, all were erased and disappeared. Every link that tied me, and pulled me to Zelva was broken in an instant: Na Vostok - these two words took complete control of me.

I changed my plan. I rode after the family crossing the road. They explained to me how to reach the main road leading to Minsk, because this was the way East, to the old Soviet border. “See!” said the head of the travelling family, “ The smoke filling the skies to our left is Slonim burning. And to the right,

[Page 89]

Zelva is burning, and the Germans are at our backs. Travel quickly!” I did as he said, and travelled with great speed. In every village that I passed, I sought bread, because I believed every word that farmer had said:

“Whosoever shall flee to the East will not perish from hunger, but will remain alive”.

In one of the villages, I bought a loaf of bread and tied it to the bicycle. Rested and confident, I resumed my journey. Close to one of the towns, I met my friend, Jejna Bublecki. He was heading for Zelva. Quickly, I explained to him that it was critical for him to travel with me to the East. A tragedy would occur in the West. I had even seen Zelva burning in the distance. He was convinced, and we travelled together. After several kilometers, he stopped. “You are travelling much too quickly,” he said, “I haven't the strength to keep up with you.” Again, I tried to convince him. I suggested that he ride first, and I would follow him. He waited a moment, hesitated, and said that he wanted to reach Zelva, and began to weep. And he turned his bicycle around and headed back. I continued along my way and thought: two friends: one to the East, and the other to the West.

The next day, I reached the main road to Minsk. From that moment, I entered a hell on earth. Thousands of people streamed eastward, while low flying German planes sowed death with machine gun fire. I was able to see the laughing faces of the pilots. The way was covered with hundreds of scattered corpses, dead horses still hitched to their wagons, suitcases, bundles, countless possessions abandoned by people, and bicycles.

Old and new automobiles were abandoned at the sides of the road when they ran out of fuel. It is impossible to describe the terrors of that road of blood. In my memory, the image of a young woman is indelibly etched. She was beautiful, and she ran about, clutching her dead baby girl in her arms, killed by a bullet that split open her skull. The child's blood had spurted all over the mother's face, arms and clothing. People that passed by her side said to the mother that her child was dead, and that she should bury the child by the side of the road, and to continue to flee. The mother screamed hysterically: “Leave me alone!! My baby is not dead!! She'll never die!!” And this mother continued to run about aimlessly, with her baby dangling in her arms.

With nightfall, the hell abated somewhat. The planes did not fly night sorties, and the road was rid of its dead and wounded. I continued to flee as fast as possible, because the Germans were right behind us. Desperate people, retreating soldiers, officers who had stripped off their insignias, all these fell upon me and wanted to steal my bicycle. I resisted them with all my strength. I received blows, but I also returned them, and didn't lose my bicycle. Eventually, I used it to reach the city of Smolensk. In Smolensk, I succeeded in getting on a freight train heading into the heart of Russia. I got into the train after stepping over the heads and bodies of people weaker than I. On the train roof, on the stairs, in every corner where it was possible to hold on, people were crammed in. Day and night we rode standing, and we even slept standing. When I used to awaken from such a sleep, I would always ask the same question: “Is the train heading East?” The people around me named me “the youth who always dreams of the East.” In this train, I reached the city of Kazan, and it was there that I spent the entire war.

To this day, I frequently think about my meeting with the farmer, Tarlokov, about his prophecies and their meaning. And always, a single question stirs within me: Is there a fate for each nation, and each human being?

by Yitzhak Shalev

The year was 1946. The freight train in which we were travelling on our way from Russia to Poland entered a side rail and stopped for a full day at the Belzeč train station, not a great distance from the Belzeč Extermination Camp where over one million Jews were killed.

My travelling companion, a young man from Czechoslovakia, proposed that we inspect the camp. The first Pole we encountered, whom we asked the way to the camp, took us for Poles, eagerly explained to us with no trace of emotion, how to get there, and he ended by adding:

“There's nothing to see there. I can tell you how it was, and save you the trip: they killed them -- thousands a day. They arrived here in crowded, overflowing freight trains, and when they opened the cars, many of them were dead already. They stripped them naked, and took them on foot to a field, and there, they lined them up alongside wide, deep trenches, and shot them. They are laid out there, rows and rows, one on top of another. Now, there is nothing to see there. On top there are a few skeletons and rotting corpses. The farmers from the vicinity dug them up out of the ground. They are looking for gold fillings in their teeth”.

When we got close to the place, we saw a circle of women sitting on piles of ashes and digging with metal or wooden eating spoons. “This is the place they burned the clothes of the Jews,” they explained to us. “If you search patiently, you find gold rings here, gold coins, and occasionally diamonds. It's probably not worth your while to rake here, you should go on a little further, over the hill, and turn to the right, and go straight up the road. It will bring you to the field where they killed the Jews. There, it is possible to extract gold teeth from their mouths. There's a lot there. It's just hard to stand the stench there in the field. It's a little difficult to breathe. But for strong young men like yourselves this should not be a problem. You'll also find shovels there to dig with”.

“I suggest to you that you dig a little deeper,” said one young woman, “because the upper levels have already been dug through, and it's difficult to find anything. But deeper, there is still quite a bit of gold. Look! Look how pale these men have become!” said one of them. “Apparently, they're afraid of dead Jews! Go, go! If you put up with a little smell, there is gold!”

With quivering legs, we distanced ourselves from that place behind the hill. “Hey! Boys!” yelled one of the women after us, “Dig deeply, and a lot, so you find a lot of gold, because you owe us a share for the directions you received from us!” And the women burst into a loud laughter, whose echo was heard in the distance.

We approached a narrow road that was bounded on both sides by high barbed wire fences, and the road opened onto a wide sandy field. A fledgling forest grew on three sides of the square perimeter. The open side of the field was where the narrow road we were walking on joined it. From a distance, we could see people digging in the ground. Heavy odors encumbered our progress, and caused us headaches and nausea. We entered the field.

Hundreds of skeletons and rotting corpses of men, women and children were spread all over the field.

[Page 91]

Skeletons of women with hairdos, in which the combs and pins were still in place. Fingers with nails, on which there was still polish. Skeletons and corpses of children, with dolls and toys still clutched in their hands. Heads of young girls with pigtails, with a ribbon tied in the end. Heads, with beards and sidelocks. Tefillin that had been torn and shredded. Tefillin for the head. Tefillin for the arm that were still intact. Tefillin bound around a hand. Pages from a Tehillim, pages from prayer books, stained with dried blood. Skeletons that were still recognizable as bodies, and corpses that were already skeletons.

All my senses were overwhelmed to the point of fainting. My legs, my hands, my body, all seemed to be responding to forces outside of my control, and my thoughts were blacked out. I was struck dumb. My lips seemed to be whispering incoherent phrases. Walking and stumbling, stumbling and walking, we left the field.

We returned to the train. I laid down on the seat. My eyes were riveted on the ceiling. My lips uttered the same sentence, over and over, a hundred times. A thousand times. For an hour, perhaps two hours. They whisper and return to the same sentence:

W H E R E I S G O D ? ? ?

by Yitzhak Shalev

In 1938 I lived in the city of Ivtzvisk for business reasons. In 1939, with the entry of the Soviets into our area, I returned to Zelva. These were the initial months of the establishment of the Soviet regime. The town changed completely, the people changed, the way of life changed and the means of livelihood changed. The man of means and renown tried to hide his worth, because he feared the future. Merchants and storekeepers tried to end their businesses, and turn to labor. Smart looking clothes were hidden away in closets. People dressed in simple clothes that didn't stand out or look unusual in any way. Everything took on a drab appearance: people, as well as the surroundings. In these times, I met a man in the street, who greeted me. His identity was unclear to me. When he inquired as to my doings, he approached me and said: “I am Jacovitzky, the lawyer Jacovitzky.” Before me stood an old man, sloppy in his dress, bent over, with hair that was streaked with white, and with a beard, also streaked in white. He bore no resemblance to the lawyer Jacovitzky that I knew not long ago, who was young, with an athletic build, athletically inclined, and a good dresser. I stood in front of him dumbfounded. After a moment of silence, he asked if I was prepared to escort him home. He had something unique to tell me. When we entered his house, he turned to me and said: “I am about to tell you something terrifying. You are the only one to whom I am revealing this secret. I ask your word of honor that what you hear from my lips will remain between the two of us only.” I promised him this, and here is his tale:

On one of the nights when there was no government in the town, because the Polish authorities had left the town and the Red Army had not yet arrived, some people knocked on my door, representing themselves as officials of the Soviet Regime, and demanded that I open the door. Two men entered the house, both armed, with red armbands on their sleeves. They ordered me to get dressed, and follow after them. When we left the house, they directed me to go to the municipal building, and they followed me with drawn revolvers. In the municipal building, they took me to a room where they told me to sit down and keep quiet. A short while later, the “American” was brought into the room (this was a descriptor used for a rich gentile who had come from America and had bought himself a small piece of property near Zelva. Everyone knew him as the “American”). After him, they brought in two other men who owned property in the area (whose names I don't remember) and finally, they brought in the young Catholic priest from the church on Razboiaishitza Street.

During all this time, we were under the surveillance of three armed men, who did not permit us to talk among ourselves. From the behavior of our guards, and from the fragments of sentences I was able to hear, I gathered that one other individual was still to be brought into the room. After an extended wait, two armed men with red armbands entered the room, and informed the three that they didn't find the Rabbi at home. They organized searches in all synagogues, but he was not to be found there either. After a short conference, they decided to send the two original men back to the Rabbi's house and the remaining ones would begin with us. Up to that moment we had no idea of what awaited us.

The first one was the “American.” He was ordered to get up and go to the exit. Behind him walked two of the guards with drawn revolvers. One was left behind to guard those who were left in the room.

They left the building, went around the structure, and brought the “American” to the wall of the

[Page 93]

building that was about three meters from the window of the room in which we were sitting, and with no delay, proceeded to shoot him. When he fell dead, they picked him up and threw his body into a wagon hitched to a horse that was tied up near the window. All this took place in the full view of the rest of the detainees who were sitting in front of the window.

After him, they took one of the men who owned property in town, and his fate was the same as the “American's,” and then the second man who owned land. When it came to the priest's turn, the dawn started to break. I saw him standing against the wall, crossing himself continuously. He was also shot, and his body thrown into the wagon. I was left for last. I heard the steps of the executioners getting closer to the room. I also heard the wagon moving from its place. The door was opened swiftly, and the two entered the room, and ordered me to get up and leave the place as quickly as possible. They warned me, that if I revealed what had happened during the night, my blood would be on my own head. Apparently, after daybreak, when the residents of the area arose to go to work, they didn't have the nerve to continue with their activities.

After an extended silence, and after gaining control of his emotions, he added:

“Thanks to your Rabbi who was not at home, they lost a lot of time, and were unable to finish their work before dawn, and that is how I survived”.

Several weeks after I had met with Jacovitzky, four corpses were discovered in the earth in the Bereshko Forest. The new regime organized an investigation, and the evidence led to five young gentiles from the village of Borodetz that belonged to the communist underground. They were also regular employees at the factory owned by Borodetzky. The Soviet regime wanted to demonstrate that there is law and justice in the socialist order, and arranged a public trial for them.

I attended several of the sessions at the courthouse. The defendants sat on the bench for the defense, with broad and insolent smiles on their faces. They didn't lie, and didn't admit anything. All the witnesses that appeared for the defense testified to the appointments the defendants had in the underground, and their heroism there. The spectators at the trial had the impression that the court was on the verge of awarding the defendants laurels of honor and heroism. The trial continued with recesses of weeks, from one session to the next. The defendants, meanwhile, went free, and continued to do their normal jobs.

Naturally, the lawyer Jacovitzky kept his secret to himself, and I also kept my word of honor to him. Both of us knew that our testimony would not harm the defendants, but probably would harm us. During the hearings, rumors and stories spread about the night of the murders. It was told, that a short time before the Red Underground reached the Rabbi's house, that Ephraim Moskovsky reached the Rabbi and warned the Rabbi about what was about to happen. He advised the Rabbi to flee his house and find a place to hide, until the threat passed.

When I reached Israel after the war, my townsfolk told me about what they had heard from the mouth of the Rebbetzin Kosovsky. Therefore, it was Ephraim Moskovsky who came to the house of the Rabbi that night and told him what was about to happen, and in this manner, the life of the Rabbi was saved.

|

|

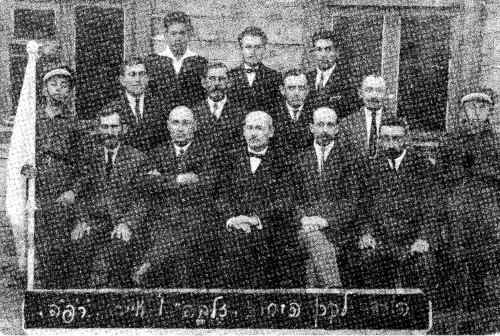

| Vishniatzky, Y. Halpern, Y. Yarmus, Y. Moorstein, N. Gelman, A. Ritz |

|

|

|