|

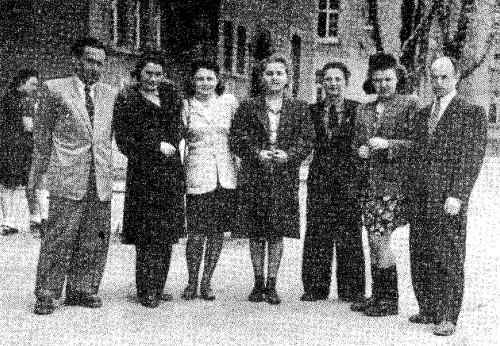

Shmuel Jarniewsky, A. Borodetsky, M. Loshowitz, S. Borodetsky, Kozlowsky, R. Borodetsky, Y. Wallstein

|

|

[Page 39]

by Yerachmiel Moorstein

At the beginning of the twentieth century, during the period of my childhood, Jews lived in significant numbers and made their living in the towns and environs around the city of Zelva. I was born at the edge of the Medukhova Forest, which was widespread, in a village home that was sunk into the earth on one side up to the windows, which was probably occupied for many generations before me. One of the wings, was occupied by my grandfather, Zvi Moorstein who was still alive, and born in 1850, along with my grandmother, Batia. From his lips, I heard many stories about his grandfather from the days of Napoleon....

We were the only Jewish family in a village of about fifty in the area, most of whom were of the Russian Orthodox faith, and the rest Polish Catholic. They were certainly not distinguished by their affection for Jews, but conducted themselves with dignity towards us, because all our menfolk were healthy, vigorous and strong. My uncle, Abraham, even was awarded a pocket watch from Czar Nicholas [II] as a prize for being a cavalry officer when he served in the army in the artillery. In addition to this, my mother was recognized as a “practical nurse,” and would attend to sick people in her spare time. She could apply cups [bahnkess] skillfully, and in her bag, she had all manner of pills and medications... the farmers used to come to the house to solicit advice and direction from my mother, even with help in corresponding with the government. The connections with these self-same farmers existed for generations, and even in bad times, the lives of the Jews were protected.

Everyone spoke the local language - Byelorussian (White Russian). It was natural wherever possible, that we, the children, tried to speak their language, and to play with the village children, but not all of them, and not always, did they permit this, and the central reason was - we belonged to the people that had crucified Jesus...

In the First World War, the farmers hid their cattle in a corral in the forest out of fear that the soldiers would confiscate them. There were Jews who objected to taking our cattle into their corral, and because of this, we built a separate corral entirely. Large numbers of hungry soldiers passed through the area, who foraged for any sustenance they could find, and one day they came upon the tracks of the cattle, and emptied out the gentiles' corral, but they did not touch the Jewish corral. The gentile elders took this as a sign of divine retribution...

When the Russian army began to retreat, with the Germans at their heels, pandemonium broke out, and the farmers fled into the heart of Russia, and only stragglers remained behind.

The nearest Jewish family lived in a village that was about three kilometers distant from us. On [Jewish] holidays, other “neighbors” like us would go to this town, understandably on foot, in order to fulfill the obligation for community worship. I was very lucky to make part of this trip riding on my father's shoulders, and to meet with other Jewish children like me who spoke Yiddish. This was a very moving experience for all of us. I still remember one of them, Ezekiel Kaplan was his name, who emigrated with his parents to Argentina, and after several years had gone by, he wrote to me that he had become involved with newspaper publishing.

I can still hear the bright and soulful chanting of my grandfather who lead the prayers, which plucked at the heartstrings of these isolated Jewish people, who lived in the midst of this gentile populace, in an era as turbulent as the creation itself, in the midst of a brutal war that consumed victims without

[Page 40]

number.

My father, Isaac Jacob (Yitzhak Yaakov) Moorstein, like his forbears, made a living from lumber. He was expert in recognizing all different kinds of trees, and those not fit to be sold for export, he would keep to build houses for the farmers, and he divided up his trade among the Jewish merchants who used to visit our home, and even spend the night with us. When they were in our area, I came to appreciate that we were not isolated, and that there were other Jews in Russia, and in other lands as well. How I would yearn to speak with these Jews to see and learn how they lived!

My mother was the daughter of Rabbi Leib Ber Vand, who was the author of about fifteen books of scholarship and tradition, and lived in Piesk, about forty kilometers from our village. She was a genuine helpmeet. She fulfilled her role as the woman of the house, the educator of her children, whom she bore every other year, with great skill and dedication. She raised us in a comprehensive Jewish spirit, and assured the fulfillment of the commandments of the Torah, and during the long winter evenings, we would sit around her and listen intently to heartfelt telling of stories about the Jews and to beautiful songs that she knew to sing in her sweet and pleasant voice.

My parents kindled in me the desire to learn. When I finally reached the tender age to start Heder with the Melamed Shlomo, I already knew how to read, and even to say my prayers. Together with my sisters, Yaffa, Zipporah and Esther, we lived with a family of our relatives in Zelva which was about seven kilometers from us. I was very lonesome for our home. On Sabbath Eve, right after school, we would set out on the dusty road to home, and after a couple of hours, we reached our warm little nest, tired, but I had found my lost treasure...

The term of study of the Heder was counted between the High Holidays to Passover, and was called the Period [literally: the Time]. World War I broke out during my very first school Period, and life was derailed. The orderly learning in the Heder, where I excelled in writing and reading, came to a halt, and I returned home to the village.

This war, which during four years claimed 20 million victims, and visited us with destruction and suffering, and brought us horrible brutality, also brought soldiers to our home, among them Jews, who served in the Russian army, and after the German occupation, their soldiers, who served in the German and Austrian armies. We even had a Jew from the Turkish army, Turkey being a member of the alliance... together with these came hordes of refugees, who were uprooted and left homeless. All of these found warmth and aid from us to the extent we could offer it, seeing as we also suffered from great want at the time. There were educated people among these, who gave of themselves and helped advance us with our education. This channel brought us books, which I read with great speed. In particular, the book Avahat Tzion, by Avraham Mapu made an impression on me, and its heroes, Amnon and Tamar... in Zion, the land of our forefathers! Among the refugees was a relative, Leib Lansky, who was brilliant, and he taught me Torah in generous measure. In normal times, he was a teacher at the Jewish Gymnasium in Volkovysk.

The Russians retreated, and the Germans reached their rear echelons in Russian territory. In Zelva, one of the refugees was an ardent promoter of Hebrew language, and opened a public school after obtaining his citizenship. Only six children were enrolled, and I was one of them. The teacher, who was an idealist, sunk a great deal of effort into us, and succeeded in inculcating the Hebrew language into us, and even got us ahead in our studies. Sadly, he left us after only one Period. The parents of the students, most of them poor, and blessed with many children, could not provide him with

[Page 41]

adequate sustenance.

The Germans concerned themselves with implanting the German language, and had brought from their country, two Jewish women teachers, and in this manner, they also enlisted as a teacher, the young Dr. Jacob Sedletzky, a native of the area, and the only specialist. Students were enrolled, and for the first time, even girls were enrolled, and the school was opened, but not for long. The Germans began to falter. The cold in the Russian heartland, and the irregularity of supplies put pressure on their center. Poles began to organize brigades that planned to take control that was slipping from the hands of the Germans, and again chaos reigned. Partisans organized themselves into brigades, and they would attack and plunder what little was left.

My father, of blessed memory, was one of the many millions of victims claimed during those four years of war. My mother was left a widow with five children, the oldest of which was a thirteen year-old girl, without any sources of livelihood or sustenance. The isolation and fear of remaining in the village among the gentiles impelled us to uproot ourselves and leave, after hundreds of years, and certainly forever, the house that I lived in until I reached Bar Mitzvah age. No more to have the surroundings of nature, the green fields bounded by the wide forest, enveloped in mystery which stirred both curiosity and thought... there is a heart tug and an longing, even after seventy years of my life... we moved to the nearby town, Zelva, which was an administrative hub that had a population of about two thousand, among which there were several hundred Christians. We lived in a small, low house on a narrow street, full of mud during winter season, and in the summer - clouds of dust from the passing of cattle herds to and from the meadow... but at least we were living amongst Jews! The Jews here conducted a full community life. In the Schule Hauf was the center of the synagogues, and I found much substance and interest there. In the Bet Hamidrash of the synagogues, two prayer minyans were conducted each morning. Between Mincha and Maariv, we also heard a lesson in Mishna from one of the scholars. I would attend worship with regularity, and resolved not to miss any prayers. I was observant of all commandments whether they be light or onerous. I found friends here that matched my temperament, and no longer felt isolated, yet still, I was an orphan... there is no one to watch over you, no one to be concerned about your welfare, here you are leading a very insecure existence... my mother wanted to see a change in me to become the man of the house, and on the night of the Seder, it was my role to act as head of the family. But the repast was meager, and damp with tears, as I conducted the ritual as it says in the Haggadah, in accordance with tradition, but it enervated us. We struggled mightily not to have to accept the public charity available through Maot Hittin, and we prevailed. To my mother and dear sisters I was a symbol of hope, that someday in the future I would become famous!!! I genuinely wanted to help them already, but really, how?...In Zelva there were three Heders for pupils, and there they learned Torah, reading, writing and arithmetic. But what after that?

And there were Yeshivah students who came from faraway places to study in the Bet Hamidrash, and also local youths, who obtained learning from self-teaching with the use of books. I, and several other pupils, used to get an “hour” from one of these young men, generally twice a week, in order to accelerate our learning, but even the very meager cost of these lessons was a heavy burden for me...

This was a very difficult period. The Jews, especially the merchants, became progressively impoverished. Without a place to learn, and with no gainful employment, the youth of the town became idle. The outgrowth of this distressed situation was the establishment of branches of organizations, mostly Zionist, but also the Bund and communists. There were young men who were

[Page 42]

drawn to communist ideology, and gave their ideals substance by going over to the Soviet Union.

Despite all the tribulations of the time, our home was a happy home, full of things to do. From our house, one always could hear the sound of music, song and dancing. I learned to play the violin. All my sisters had beautiful voices. Faigel was a beautiful girl, and she helped my mother with the housework. Esther was a seamstress, a soulful singer, dancer and actress. Batia was also a seamstress, and could express herself beautifully in Hebrew. Sarah completed the syllabus of study at the Tarbut school, and studied further for six years at the Tarbut in Vilna, and graduated with excellence, after which she became the principal of a school in Slonim.

Feverishly, I threw myself into studies and Zionist organizations. I acquired knowledge from independent book study, and also learned bookkeeping, and continued to play the violin. The land of Israel - Palestine then appeared very distant indeed, but the yearning to reach and live there implanted in us an agenda for the future...

Together with several companions, we created out of nothing - a library, and in the library we had a catalogue of thousands of volumes. We organized the books in which were laid the foundations for the Tarbut Hebrew School. The school was not established in time for my sister Zipporah and I to take advantage of it, but the rest of my sisters were educated there.

And so, I grew up, I worked in a sawmill in Slonim for three years, and after that in Pinsk for four years as the director of a Jewish agricultural cooperative founded by the J.K.A. and ORT, and I even participated as a representative of my country to Warsaw under the authority of Singlovisk in 1933.

In the Pinsk [Memorial] Book, volume II p. 576, some of my writing can be found about the cooperative.

After a year, I married Hannah Dolinko. Her parents perished in the Holocaust. Their daughter Liza, may she rest in peace, passed away in the Holy Land. Her sons, Shalom and Daniel, and her daughter, Bruriah, live in our land. The rest of this family emigrated, among them the Meltzer family, and they live in the United States. They are committed Zionists, and make substantial contributions to finance all manner of needs in our land.

We went to the Holy Land in 1935. We reached the port of Jaffa in Palestine-Israel at sunset, and were welcomed in Hebrew, and I felt that I had finally reached the homeland that I longed for, and there was no one more fortunate than I !!!

The British still ruled the land, and the Arabs were beginning to organize themselves to oppose our immigration. Bloody clashes broke out, and the Arabs used their arms to attack Jewish settlements, and the British constabulary didn't restrain them, but the Haganah stood in the breach and gave back a good account of itself. We had dead and wounded, among them myself. I was taken to the Hadassah Hospital, where I was kept for about two months, but I left there healthy and in one piece. From that time on, I participated in different capacities in the many wars of Israel. Even to this day, I am active in the central committee of the Haganah veterans in the Dan branch.

As a Zionist from early childhood, I am fortunate in having done my part in the realization of Zionist goals, and in the establishment of the Land of Israel from the time of my arrival, even before my Jubilee year which draws near. I discharged all my obligations to my beloved homeland under difficult

[Page 43]

circumstances, several times at great risk to life and limb, and here I am, exultant and proud at having attained this !!! The eternity of Israel is no lie !!!

In the Encyclopedia of the Pioneers of the Settlements and its Builders, by David Tadhar, in volume XIX, page 5674, there is a summary of my work.

I brought a blessed family into the world. After our arrival, we had a daughter, Nitzah. Two years later - Aviah. When the terrifying news reached us that our loved ones were annihilated and destroyed by the Nazis and their accomplices, and that no trace remained of the families that were related to us in Zelva, and that only I and Hannah, and my sister Batia remained who could preserve, carry on and fill out the family to help populate the nation, the responsible reply was:

We had a son, Jacob, and after him a daughter, Dorit.

Nitzah and [her husband] Ernest-Raphael are both outstanding physicians, and they have a daughter Ruth and two sons, Yair and Joab.

Aviah has a daughter named Ephrat.

Jacob and Nitzah have a son named Itai, and a daughter named Adinah.

Dorit and Ilan have the daughters, Inbal and Reut, and a son, Ohad.

My sister, who is the widow of Meir Feinstein, who was killed on the Jerusalem road in 1948, has a daughter, Shafrirah, and with her husband, Yitzhak Fuchs, has two daughters, Liat and Shiri. The children of my sister's late daughter Sarah, of blessed memory, are Orit, Michal and Paz. Their father is David Hirschman.

I am one of the last ones, who lived during the period of the Holocaust, a witness to the uprooting and annihilation of all the beloved people of the community of Zelva, and among them, my mother, Shifra, my sister Sarah Moorstein, my sister Feigel and her husband Moshe Gerber, their son, Yitzhak and their daughter Jaffa, my sister Esther, her husband Joseph Freidin, their son Yitzhak and their daughter Atarah, my aunt Freidel and Leib Bereshkovsky, their son, Shmuel Zalman and his wife Liza from the Gelman family, and their three children, Jacob and his wife Resha and their three children, Yitzhak and his wife Rachel from the Becker family and their three children, Abraham and his wife Rasha of the Slutsky family, Lieber, Moshe and Zevulun, and also the daughter, Sarah, married to Leib Vishnivitzky and their four children. My aunt Leah and her husband Zvi Selman and their children: Zalman, Yitzhak, Benjamin, Leib and Batia.

Joseph ben David and Bashka Moorstein (their children live with us in Israel - Sarah and Nurit, Joseph and Dorit), their son David, and their daughters, Havivah and Esther, and also our relatives in related branches of the family. All were vigorous, intelligent people, and an asset to their people. I am discharging some form of universal obligation by having their names permanently inscribed in this Memorial Book, along with the brutal events that cut them off from us, so that succeeding generations will remember them and will never forget, and will continue with the preservation and strengthening of our people and nationhood!!!

My uncle, Eliezer Moorstein, was active in the revolt against the Czar in 1905. He was released from prison, an act facilitated by a bribe provided by my father Jacob, and whisked out of the country to the United States. He was followed, after a few years, by his brother Chaim, and after him, Abraham, after having served in the Czar's army, which earned him the watch as a prize for his distinguished role as a cavalry officer in the artillery. They reached the well-endowed land of freedom, America,

[Page 44]

and they were a mainstay to their aging father and to the remainder of their family during World War I with their support, sending necessities (and who didn't?...), packages and dollars at a time when even they didn't have very much...

I also am obligated to record the efforts exerted by Zelva natives whose commitment to the Jewish people manifested itself in all sorts of ways. In the August 1971 edition of Ma'arachot, the publication of a book, entitled, “The Pledge” (Ha-Ne'Emanim) was publicized, in English and in Hebrew translation, and it was dedicated to my uncle, Eliezer. The book was written by the author Leonard Salter, my nephew, and according to the table of contents, it contains a unique chapter that only at the last brought to light an important fact: the activity of in the United States regarding the [Israeli] War of Independence and its conduct.

This may have been the first time since the Bar Kochba rebellion that the Jewish people were called upon to help their brethren not only with philanthropy, but with the provision of armaments: rifles, cannon, boats and planes.

The Jews of America were unfazed by either danger or difficulty when it came to helping Israel in its momentous hour of need, and it was a “finest hour” for many of them as well.

During the War of Independence, when we were in dire need of arms beside Sten guns and the Davidka, my uncle Eliezer, this outstanding Jew, endangered himself personally, in addition to the substantial funds he provided, and provided us with very valuable resources. The leaders of the Haganah, among them Golda Meir and Yigal Allon, used to come to his home, which served as a critical staging point for shipment from his warehouses in the port of San Diego in California.

My uncle Eliezer's children are:

A daughter, Beattie and her husband Leonard Salter, both writers.

Their daughters Lucy and Amy.

A son, Richard, may he rest in peace, who was an economist and a presidential advisor in the United States, and a granddaughter, Karen.

My uncle Chaim's children are:

A daughter, Frances, and her husband, David Zwanziger, their daughter, Eve.

A son, Daniel, a physicist, who spent a year at the Weizmann Institute.

A daughter, Rena, and her husband, Sy Goldsmith, their son Gary, a physician.

My uncle Abraham's children are:

Benjamin, a psychiatrist, his sons in academia: Bruce, Mark and Ronnie.

Harry is an accountant, his wife is Sylvia, their children, Deborah and Barton.

Here, therefore are these good Jewish people, who were compelled to flee the land where their fathers and forefathers lived for many generations before them, who left and regrouped themselves in America, a land that took them in, and gave them the opportunity to develop themselves in many fields of endeavor. This took place before Our Land was in any condition to attract them. They were

[Page 45]

a mainstay to the Jews who stayed behind in Europe, the inheritors of suffering after the Wars. Their help manifested itself in many different ways. I can still remember the communal kitchens that were opened in 1917 that infused life into otherwise dried out bones...

As of today, their children continue their posture, with all respect, to be committed with all their means in supporting and strengthening the development of our country!!!

by Joseph Slutsky, Melbourne, Australia

(Original translation from Yiddish to Hebrew by Y. Moorstein)

This was my village, full of life, in which I spent my youth, and now it no longer exists. Zelva was well-known in the entire area, and it stood out for its love of Israel and yearnings for messianic redemption. It bubbled with vitality, and was full of romantic beauty, having on one side the Zelvianka river, in whose cool waters we would bathe in the summertime, and on whose ice we would skate in the winter, and on the Sabbath and festivals, couples and the rest of the townsfolk would stroll along the Haufgasse.

Zelva did not produce academically trained people because of the economic circumstances which prevented the young people from continuing with studies and the acquisition of advanced learning, but this same youth excelled in self-learning, the proof of which - in Zelva there were two Hebrew schools: Tarbut, and Tachkemoni. Zelva youth read a great deal, and participated in all aspects of Jewish life.

The village was Zionist. There were organizations, branches, a drama club, there were debates held on political and cultural subjects, in which the better speakers and lecturers from Warsaw and the area would come and address filled halls.

I was active in the Revisionist organization. I remember the visit of Dr. Lipman from the central office in Warsaw. After his lecture, in the middle of my ride with him to the train station in the wagon of Velveleh Tatkeh's, he said to me that of all the towns and villages in the area, Zelva was truly one of a kind. He then turned his attention to the remarks of the wagon driver who expressed the following thought: “Everyone wants to elevate and improve mankind. It would be better if they improved the quality of these roads, so it would be easier for my horses to pull the wagon.” Dr. Lipman said at that point that he would adopt the very practical notion of this otherwise simple, uneducated man.

During the famous market fairs, pickpockets would come even from as far away as Warsaw. In 1939, about two months before the Great Deluge... I left the village, and I remember Hitler's (may his name be erased) historic speech on Czechoslovakia. I met up with Leib Spector, of blessed memory, whom I thought to be an intelligent Jewish man. He told me that in his opinion there would be no war, and if there was a war, that even Hitler couldn't overpower three and a half million Jews. To our great pain and sorrow, he was proved wrong.

Only one Jew sounded an alarm: [Vladimir] Ze'ev Jabotinsky. To me, he continues to be a guiding

|

|

|

A Group of Holocaust Survivors at their First Meeting Shmuel Jarniewsky, A. Borodetsky, M. Loshowitz, S. Borodetsky, Kozlowsky, R. Borodetsky, Y. Wallstein |

[Page 46]

light even in ordinary matters of living.

After the war, when it became clear that the Jews of Poland were exterminated, I tried to bring several families that remained in Russia to Australia: Spector, Hertz [Herzel] Borodetzky, and Anka Borodetzky.

by Yerachmiel Moorstein

The desire to learn and acquire knowledge gave no rest, but how was one to accomplish this? The First World War is at its height, and the educational “institutions” of the town are continuing to dispense learning, but at a sparing rate. Some heders for pupils are opening up, but they are just for the first 2-3 years of instruction. In order to progress, it was necessary to travel to a place of learning. The county seat was about 20 kilometers away, and there was a Talmud Torah there, an educational establishment, in the absence of a Yeshivah, where learning was dispensed, and where the Talmud was taught to students who showed ability to progress. My parents decided that this was the proper place for their only son.

And that is how I reached the city of Volkovysk, in my eyes as one young and untried, sent to my relatives, who lived in a stone house, whose walls were thick and sunk into the ground up to the windows, and where drops of moisture dripped like sweat from the ceiling, and it is late in the fall, and the rain outside penetrates to the bone.

The father of the house, a good-hearted Jewish man, was a whitewasher by occupation, and from this time until Purim - he was idle. He tried to make me as comfortable as possible while I lived with them, and he prepared some fresh straw for me on a bench and sofa, the only one not occupied in the house, and over this they spread a large flaxen spread; a coverlet, thin from great use, which served as my blanket, and on top of that, my outer clothing, and under all of this, I didn't fall asleep very easily...

The woman of the house, who was our family relative, the mother of five children, the oldest of which was bar-mitzvah age, tried to help me, but with what?

This family had great difficulty in providing clothing and cover for its own children, and the same for the meager food they had, thus my own sustenance depended on the “days,” that were promised to me by donating families, who were also related, that invited me to come and dine each day at a different household which offered such a donation [this practice was known as essen teg in Yiddish, literally translated as “eating days” -JSB]

After I became resigned to my fate, I was very depressed, frightened by each leaf that blew at me, lacking security, and with very few kopecks in my pocket. I went to bed. The night was very long, until I would get up in the morning, and go to the home that had committed to feed me breakfast that day, and also lunch.

[Page 47]

Feeling insecure and sad, I would wend my way to find my appointed place, and when I would see it in the narrow lane, by weak light according to the description that I had, I would knock softly on the door, and a boy would open it, and indicate that I should sit next to another boy, who had already arrived and sat at the table.

The boys who were inured to this way of life were spiritually strong, because they were Yeshivah boys. They had finished the Talmud Torah, and because of houses like these, they were continuing with their studies independently, and felt adequately unburdened.

After several routine questions, such as my name, where I came from, my relationship to this family, which I could only explain with great difficulty, they started to cough, and urged me to join in. I started to, but quietly, and they yelled at me, “louder!” The purpose of the coughing was to waken the woman of the house. As it turned out, this donor had left to go to the bakery, and when she came back and opened the door, I quietly stole out and headed for the Bet Hamidrash, my study place.

Sad, hungry, and feeling scrawny, I started to study after a silent morning prayer. I had to absorb the first lesson, but understandably with great difficulty.

I didn't recognize a single other student there. There were those among them who were abusive to me, because they were bigger than I was, and one of them even said: “what's a pipsqueak like this doing in our class?” I choked back tears in my throat, and at our first recess I went out to the Schulhauf to find something to eat, and in one of the corners I found a woman sitting cross-legged, having a heavy metal pot under which were hot coals, and next to her another pot that was well covered, and she sold a sort of baked item, made from spelt wheat, not of the best kind, fried in oil, and crescent-shaped, weighing about what you would anticipate. I took the coin requested from my pocket to pay for one, I ate it and ... I was satisfied. For a long time after this “meal,” I drank only water, but I remembered the taste for many days...

News and stories started to reach us of further stirrings that were going on. The Poles were setting up legions for an army of liberation in order to re-establish their national sovereignty.

My mother boarded a wagon used to transport merchandise, and after considerable difficulties, she reached me in order to bring me home. She was positively shaken by my weakened and stunted appearance, and it was probably only her prayers, the prayers of a caring mother, that reached the right place.

And yet, here, the story is before us.

by Yerachmiel Moorstein

(Translated from Yiddish)

Before the Holocaust, several Jewish newspapers were published in Warsaw. In one of them, Heint [Today], a column appeared called News from Zelva.

On one Sabbath, in connection with Mizrachi matters, Mr. Rabinowitz, an official of the central Mizrachi office, visited us (as was described in the reports) for the purpose of organizing a Mizrachi branch in Zelva.

In front of a gathering at the Bet Hamidrash, the guest outlined the goals of the Mizrachi organization.

The work of this organization, to involve the participation of religious Jews in the building of the land of Israel, was received graciously even by those who were not Mizrachi sympathizers, but it appeared that the speaker had other intentions. In his lecture, he accused the other schools of educating their pupils for ... conversion from their faith, and he argued that their students were simply ignorant. This irresponsible representation of their character stirred up a lot of bitterness among those involved with the Tarbut school, who then decided to oppose this association [with Mizrachi], because instead of coming to praise, he had come to severely criticize.

A special event was precipitated by the visit of Eliezer Futritzky[1] who visited us from Jerusalem, and who took the lead in directing a Hebrew play put on by HaShomer HaTza'ir. Until that time, Hebrew plays were only put on by children. This time, the young people prepared the historical drama based on the life of the Hasmonean prince, Eliezer ben Yehuda.

Mr. Eliezer Futritzky has served in this capacity in Jerusalem for the prior two years with great success, according to the review of this production that had appeared in the newspaper Doar HaYom, vol. 75, 30 December 1927. This was the source of the considerable interest in this play in Zelva.

[Also], The drama club of Poalei Zion put on the play, Der Groiser Moment, under the direction of Y. Zalman. Proceeds were used for the benefit of the fire department of Zelva.

Tuvia Vishnivisky, Esther Moorstein and Yedidia Shveysky gave outstanding performances in this play.

The Tarbut Library, which did not grow because of lack of consensus among the school leadership, received a great boost from the appointment of Mr. Garbovnick, a teacher at the Tarbut school, as Librarian, and thanks to his efforts, the library was re-established and came to contain about 1000 volumes in Yiddish and Hebrew.

by Yerachmiel Moorstein

Feiga was the sole heir of the store, since she was an only daughter. From early childhood on, she participated in the sale of kerchiefs to the farm wives, and she succeeded in this, gaining control over her business, getting ahead in business, and she did very well, and most of the kerchief inventory on the store shelves was her property, free of debt or any other encumbrances.

In time, Feiga grew older, and she was left without anyone to help her or to give her support. Well-meaning people seeking to do good, reached into the woodwork, and married her off to a Yeshivah student, Yankel Velfer, who for years had spent his life in the Bet Hamidrash. His calling was the study of the Torah. He was thoroughly grounded in the Shas [the Six Orders of the Talmud] and all its related commentaries. He paid no attention to practical worldly matters. His central concern was to observe the 613 commandments, the casual ones with as much zealousness as the serious ones, and to arrive at a world that was all good, he was a pure soul... short and thin. The charitable women who looked after his diet apparently didn't overfeed him...

Even after their marriage, Feiga ran the kerchief store without his help. The year-round conduct of business in Zelva permitted Yankel to continue to remain in the Bet Hamidrash, and to delve further into scholarship and Talmud, to pray, and between Mincha and Maariv to give a lesson in Ein Yaakov to a coterie of listeners. But when it came time for the fairs, and business activity rose considerably, then Yankel had to stop his study of Torah, and he was compelled to help Feiga with selling kerchiefs. When it came to prices and colors, he was totally lost, and he only spoke a few words of the local language, and when a farmer's wife would ask him for a green kerchief, he would give her a red one, and if she stood her ground and demanded a green one, he would answer her in the language of the Gemara with its accompanying intonation, Mai Nafka Minah? or as if to say:” what's the difference? this is a kerchief and this too is a kerchief..”.

Translator's footnote:

by Yerachmiel Moorstein

There was a cantor in the town and for the High Holidays, he also formed a choir despite the fact that aliyah claimed one of the grown up singers, but the appearance of the cantor before a full house was generally reserved for the Great Synagogue, since it had the greatest seating capacity and because the acoustics were best there. Accordingly, there was little air left to breathe, because on all the holidays, the place would get so filled up that there was no room left.

In addition to the cantor, there were several Jews who were capable of leading prayers as a Baal Tefilah, and to convey the sentiments of the congregation to the Almighty. The most venerable and popular of these was Yershel Boyarsky (the investigator), whose deep and pleasant voice would tug at the heartstrings of the worshippers. To hear him pour his feelings into prayers such as Unsaneh Tokef on Rosh Hashanah, or P'tach Sha'arei Shamayim during the Ne'ilah service on Yom Kippur, all the Jews would stream to the Da'atz Bet Hamidrash, where he served as cantor, and in a wondrous silence would listen attentively to his prayers - his entreaties to the Creator of the Universe.

Yershel served as a cantor only for holidays, since he spent most of his time as an overseer in the

[Page 50]

forests, being an expert in wood and lumber, and there were many times when he didn't have the opportunity to be home. But there were slack seasons when he was not working, and probably because he was not earning a living, he made an impression on the Heavenly Dweller with his voice, and on the praying congregation, especially the women, would gather to hear his clear and pure prayer, greeting it with sighing and tears.

by Yerachmiel Moorstein

It is difficult to conceive that the Jewish people could have survived in every nook and cranny of the world, facing all the tribulations that they did, if it weren't for the volunteers among them, who dedicated themselves to helping those who were in need. There wasn't a corner of Jewish life in which these people didn't appear and perform their service.

Among these, I raise the memory of one of the role models of charitable work in our town Zelva, Laskeh Freidin, of blessed memory, called by her grandchildren in Israel Bubbeh Laskeh.

In our country, we have socialist foundations, with welfare offices, headed by a minister with a staff that administers a large budget, and oversees all the requirements of the needy for support and assistance. Thousands of social workers work in these foundations, managers of special offices, and departments, who disburse lots of funds to the applicants, and occasionally, it comes to light that the recipient of the funds has no business being there... and so starts the conversation of where is the boundary between someone with means, and someone without means. Today, we have a concept called the “poverty line.” Someone who is guaranteed food and clothing is not below that line, but not every recipient of these funds appears to be satisfied with this. According to his reasoning, he is “entitled” to more, and he will sometimes demand this quite vehemently...

In Zelva, bread never got thrown into the garbage... if it was even available on the table in the house. Only the well-to-do in town baked challah for the Sabbath.

Among our obligation to those who come after us, is to describe how life was conducted in our communities, despite the lack of wealth, overburdened with population, and blessed with an abundance of children, without a ministry of welfare and support, and without a single salaried social worker.

Zelva is counted among such towns. It is understood that here too, there were paupers. Most preferred to go hungry rather than accept charity, but there were difficult days for those starving for a piece of bread, and it was these that the Bubbeh Laskeh looked after as a volunteer (social worker), and did all the functions of these many “foundations”.

In the First World War, when the Germans ruled for about four years, a typhus epidemic broke out, which caused many deaths, and not all the soldiers returned from the battlefield either, leaving widows burdened with the care of orphans. The blessed efforts of Laskeh eased and helped the suffering of the needy a great deal. Despite her advanced age, she would take to her feet in all sorts of weather, visiting the houses of the well-to-do, who would fill her sacks with all sorts of life's necessities, which she would then distribute to those who were in need.

As to her own modest needs, these were provided for by her son, Yitzhak [Itchkeh] Freidin, who with his blessed family made aliyah to the Holy Land, and he passed away here.

|

|

|

A group of youths A few managed... to make “aliya”... |

by Eliezer Futritzky (Ritz)

[8 March 1926]

In another two days, I am leaving the town of my birth...

In another 48 hours I will no longer see my mother and the beloved members of my family, I will not see the tombstones of my father, brother and grandfather[1]...in another 48 hours I will no longer see the ambience in which I was educated, in which I was raised, and where I lived for twenty-eight years...

All, all these, with whom I lived with for twenty-eight years, in another twenty-four hours it will be as if they never existed...

Even though I don't fear the moment, I nonetheless feel a weight on my heart, and in addition, the question weighs on me, how will I take leave of my frail mother, how will those moments pass... that is what I fear.

Even thought the house is ever so dear to me, I cannot allow myself to be found within it, I will not be able to bear my mother's damp eyes... I will not be able to sleep in my own bed, when my elderly grandmother will rise from her bed to sit in front of me and cry. I want to be able to scrutinize her face with care, so I will not forget her...

I want to run away, to run away from all of them and not to see a single one of them, not to speak, but rather to wander the backstreets of the town, to run to those places where my feet walked, to kiss the dust of the ground, to leave them, for these are the places where I spent the days of my youth.

How will I be able to take leave of you, from all of you whom I love and hold so dear, how will I be able to exchange you, my town and all who are dear to me, for the staff of the wanderer!?

But from the depths of my soul, a voice bursts out of me like a clap of thunder:

“Eliezer, Eliezer, how can you think such thoughts!? You are travelling to the Land of Israel!!! In just a little while, you will arrive in the land of your origins! Look, here you have nothing that belongs to you. Everything - everything - belongs to them, THEM..”.

Slowly, slowly the weight passes...

Nonetheless, how strange it is: for over two years, I dedicated myself body and soul to the Zionist ideal, I spent days and nights in the offices of the Zionist Histadrut, the Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael, and the Keren HaYesod, and here, when the hour finally arrives, and I, myself, am ready to go to the Holy Land that I aspired to, there is the pressure of such a weight on my heart!? Despite this...

[Page 53]

I was invited to a going-away party by my friends tonight at eight, and again a weight begins to press on my heart. Will this be the last evening in which I will find myself in intimate contact with my friends? How will I feel?

In the company of my close friend Moshe'l, I came at eight o'clock to the place the party was being held (at the home of Yarnivsky). Everyone was seated around the table. It looks like they were all waiting for me to arrive. My heart is beating furiously. Is this the last time? But there is no time to think, and they start the festivities.

At the party are my girl friends: Tzipah, Batia, Dina'tcheh and Leah, and my boy friends: Moshe'l, Moshe Mordechai, Shmuel, Zelig, Lipik from Volkovysk, and Yerachmiel.

I felt great at the party, you might even say, terrific, I practically didn't feel that the entire to-do was in honor of me. If it weren't for the occasional congratulations and best wishes that were offered to me, I would have thought that I was at a going-away party for one of my other friends...

But before the party was over, I no longer had any doubts, and I felt only too well, that it was me who was going to depart, and I am going to be separated from all my dear ones. I felt that I was the one who was leaving, and they are staying behind. They will go on with their lives, in the same surroundings, and I am taking up the walking stick of the wanderer in my hand, and I begin to wander in the outside world, so different from the world in which they live. They will continue their lives in the same phase that we all lived in, and I am passing into a completely different phase, and in my soul, a sort of feeling of jealousy towards them stirs.

They will yet continue to live at home with their parents, enjoying their beds that their mothers prepared for them, and I, the youngest among them, will be lonely, forsaken, without a relative and without someone to rescue me. Far, far from my family will I go...

And once again that inner voice thunders at me:

“Eliezer, Eliezer, you are travelling to the Land of Israel!”

That voice truly takes care of everything, but yet...

I part from my friends in high spirits, and accompanied by my friend Moshe'l, I return to my home. We enter the yard of the house. It is silent, all are asleep, the lights are out... and it appears to me that I am surrounded by everything in my neighborhood: the houses, the yard, the trees - everything, everything is whispering, talking about me and my forthcoming trip. It appears to me that each and every thing says to me:

“Take our last blessings. For you see us now for the last time! For you see, we are parting now! We are parting, and who knows, perhaps for ever and ever. Take our last blessings. Look! Look again! Don't forget our shapes and what we looked like!..”.

And it appears to me that even the moon in the heavens speaks to me and whispers: “Oh, you poor wretch, you poor wretch! It is still night, and you will be here for only one more night!”

And my heart contracts from so much pain.

[Page 54]

At the sound of my knock, my mother comes down, opens the door and lights a candle. I try very hard not to look at her face, which conveys such a deep sadness, but is this not my mother, my dear mother, who worked so hard on my behalf. My mother, who suffered so much from me until she managed to raise me, and I want to run to her, to fall into her embrace, to hug and kiss her, saying: “Oh, my mother, my mother!”

I lift my eyes and I see my mother standing on the threshold of the bedroom door, her head bowed low and crying, and when she spied me looking at her, she heaved a deep sigh and went to sleep. Understandably, she didn't sleep, and neither did I.

All the images pass before my eyes, to irritate me they stand before me and do not move from their place. I try to force them away, I try to fall asleep, but to no avail. Only with the coming of daybreak do I fall fitfully asleep...

9 March 1926

When I awoke it was late already, and the clock rang at nine. I dressed hurriedly, and went outside. Under no circumstances can I stand to stay in the house despite the fact that it is so dear to me...

Where to go - I don't really know, I walk slowly at the side of the street, and I think. The people coming and going look and stare at me, but I, I do not want to look at anyone...

Two friends interrupt my thoughts. Two friends from the Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael came up to me and advised me that in the evening at eight thirty, the Zionist Histadrut, and its affiliate organizations, were throwing a going-away party in my honor. All the members of the various organizations in which I was active were to participate in the party. I thanked them, and parted from them.

I rushed to the Beit Am, where the offices of the Zionist Histadrut and its affiliates were located. Even if I had only one day left in Zelva, I still had work to do in the offices of the Zionist Histadrut. It is difficult, very difficult to leave them behind. For about two years now, I have spent my time, all my days here, in these offices. I got up and worked here days and nights while my friends spent their time at leisure. I would be separated from them, stuck in between the damp walls of the Beit Am doing my “international work” there. At times, when I was in a bad mood, it was this work that diverted my mind from all cares. And when questions of “purpose” would start boring into my mind, I would always go running to the office, and there I would forget everything.

Today I am finishing the completion of the minutes of the international affiliates for which I served as the head secretary, and I am preparing to turn them over to other secretaries.

This is a gloomy day for me, because it is oh, so difficult for me to depart. I have but one comfort in my heart: I am leaving all this for a different work: the building of the Holy Land. It is practically waiting for me. My goal is the Land of Israel, and in that I take comfort...

At ten in the morning, I turned over in the presence of the director of the Zionist Histadrut, comrade Chaim Yitzhak Lev, the minutes of the Zionist organization to the new secretary, comrade Aharon Rotni.

At eleven in the morning, I turned over, in the presence of the director of the Keren Kayemet

[Page 55]

L'Yisrael, comrade Z. Helman, the minutes and principal files and all the material to the newly elected secretary, comrade Shmuel Yarnivsky.

At noon, I turned over the minutes of the Keren HaYesod to the honorary secretary, comrade Rosenbloom.

At four in the afternoon, I turned over, in the presence of the director of the Eretz Yisrael office, comrade Rosenbloom, the minutes of the office of the Eretz Yisrael organization, to the newly elected secretary, comrade Nahum (Nathan) Helman.

In this fashion, I turned over all the minutes, and I returned home like it was after a funeral...

9 March 1926 Evening

The last evening and night of my presence in Zelva have arrived.

The sun has gone down behind the mountains, and the night is drawing near. Hundreds, hundreds of questions, for which there are no answers, begin to gnaw at my mind. The sadness, worry, and fear, spread their control over my heart, and as much as I try to shake them off, I do not succeed...

Master of the Universe! Is this real, or just a dream?!

Is it true that this evening is my last evening in Zelva? Is tomorrow's evening already part of a set different from the ones in which I had spent my first twenty-eight years?! Does tomorrow's evening belong to a new period in my life?... “Oh, you moon in the sky - stop! Don't you dare to distance yourself from me! Don't pass by so swiftly! This night, it is incumbent upon me to speak and whisper about great and wonderful things... oh, evening, evening, if you could only extend for twenty-four hours... forty-eight... more... and more... how fortunate I would be!”

I won't be able to completely drink in my surroundings, I won't be able to finish my conversations, the evening will pass, day will come, and at ten o'clock at night, I will leave my home town, leave my mother and the members of my family, my surroundings, my friends, and alone and forsaken... lonely...with the wanderer's staff in my hand...

And suddenly a voice is heard:

“Eliezer! Eliezer! No! No! No! You won't be wretched and forsaken! You won't be abandoned! There is no one forsaken in the land of Israel! In the settlements and kibbutzim in Israel there is no sadness!!! You will be happy, joyous and radiant, but only in the Land of Israel! You will work at your work, and you will speak your language, you will sing your songs, you will dance your dances, but only in the Land of Israel, and only for the Land of Israel.”

Here I was daydreaming... about life in the Holy Land.

The clock rang eight... and I recalled that I had to go to the party. I put on my overcoat and I go out. It is dark outside. The sound of the raindrops stopped my daydreaming. Here I am, walking along slowly, lost deep in my thoughts, without sensing that I had reached the auditorium. I can't go in...

[Page 56]

the sound of song comes at me from the auditorium, but I can't go in. They have come together, singing and happy... but it is I who is to depart... and they... will remain. Tomorrow, they will escort me to the train, they will go back to town together, and even then they will sing as well... and I? - I will sit in a corner in one of the train cars, and I will dream...

“Eliezer! Eliezer! They are jealous of you, because you are the fortunate one, that it fell to you, that it was your lot to make aliyah to the Land of Israel. They envy you, that it fell to you to be among the fortunate ones, to work here on behalf of the Land of Israel, and to work in the land of Israel... all those who have gathered here wait with great impatience for the hour to come when they will also be able to make aliyah. In the hour when you take leave of the bitter Diaspora to go to the Land of your Fulfillment, they have to stay behind in the Diaspora, and in that hour do you envy them? - why, and what for? Why did you work so hard and dedicate yourself all your life, and why were you drawn to the Zionist ideal? Why did you work so hard for the benefit of all the Zionist foundations? Did you not yearn every day, and each minute for this hour to arrive?”

I breathed deeply, and felt lighter, the heaviness on my heart went away... I entered the auditorium to loud cries of “Hurrah!”- Here is the Guest of Honor!!!

The preparations for opening the celebration were complete. We were waiting only for the arrival of the director of the local Tarbut branch, comrade Rosenbloom. After a few minutes, he arrived.

Participating in the celebration were:

Representing

Zionist Histadrut The Director, Chaim Yitzhak Lev, and the Treasurer, Aharon Rotni. Keren HaYesod The Honorary Secretary, Chaim Rosenbloom. Keren Kayemet The Executive Committee: the Director, Nahum [Nathan] Helman, the Assistant Director, Shammai Kaplan, and the Treasurer, Shimshon Levine. Charity box distribution: The appointee, Mordechai Perlmutter, the Secretary, Moshe Rafilovitz, and the chapter membership: Moshe Slutsky, Yerachmiel Moorstein, Shmuel Yarnivsky, Rachel Buchhalter, Itkeh Schriftiger, and Esther Shtureikovitz. Eretz Yisrael Office Comrade Jacob Rotni. Tarbut Chapter The Director, Chaim Rosenbloom. The Teachers Association of the Tarbut School Shmuel Freidin, Shabtai Ratner, and Akiva Shveysky.

[Page 57]

Tarbut Library Comrade Elchanan Potztiveh. HeHalutz Ezekiel Halpern.

And in a similar fashion, my brother Mordechai [Max] was invited.

The party opened with the singing of Hatikvah. As master of ceremonies for the party, they had selected the Director of the Tarbut branch and the Eretz Yisrael Office, Chaim Rosenbloom. Director Rosenbloom suggests that the opening remarks be given by Shmuel Freidin from the Teacher's Association of the local school, I being among the first of those educated at the local Hebrew school to make aliyah to the Land of Israel. All those seated agree with the suggestion of the Director, and my favorite [Hebrew] teacher, Shmuel Freidin accepts this first undertaking. He dwells especially on the needs of young Jewish people in general, and on the needs of school graduates in particular, that youth which stands at the crossroads, seeking the right way to go. Shall the youth turn to Zionism as a solution to the question? And afterwards, he speaks about me, and he holds up as an example my participation in the youth groups and my dedication to the Zionist movement. Among his other remarks, he says:

“I feel myself to be among the fortunate, when I see the labors of the teacher have born fruit, and the first of the educated ones is making aliyah. Futritzky! Don't forget the words of your teacher, and don't stray from the path that you have hewn for yourself. Your teacher's blessing to you is: may all your wishes come true! Go on and succeed!”

Mr. Freidin's speech made a strong impression on all the participants.

Director Rosenbloom spoke in great detail about youth and its relationship to Zionism and to the Land of Israel, stopping to describe my own work for the Zionist foundations, my dedicated efforts on behalf of the Histadrut and HaShomer HaTza'ir, in which I served as the head of the chapter and head of the section. With best wishes for a successful aliyah, and for the realization of my desires, and with the greeting, Hazak Ve'Ematz!, he finished his speech, which lasted about an hour. After Comrade Rosenbloom, the Director of the Zionist Histadrut, Ch. Y. Lev spoke, and the Treasurer, Aharon Rotni. [Jacob] Rotni spoke on behalf of the Land of Israel office, for Tarbut, Elchanan Potztiveh, and on behalf of HeHalutz, Ezekiel Halpern, among his other remarks, said:

“Even though our comrade, Futritzky, stands here on the right, I hope that in the Land of Israel we will find him in the ranks of the Labor Histadrut.”

Moshe Rafilovitz offers a blessing on behalf of all the comrades and youth. And similarly, all the attendees are quick to chime in with similar blessings for me on my aliyah to the Holy Land. At the end, the Director of the Keren Kayemet L'Yisrael, Nahum Helman spoke. And he especially spends a good part of his time describing my work on behalf of the Keren Kayemet. And in this vein, he adds:

“Futritzky was not satisfied with working only for Keren Kayemet, but also took an active role in our other international and cultural branches of endeavor, such as the Zionist Histadrut, the Office of the Land of Israel, HaShomer HaTza'ir, Tarbut, and others of this kind...

[Page 58]

and he finished as follows:

” Our dear comrade, Futritzky!I haven't come at this time to thank you for all your work, because you did what was incumbent on a young Jewish man with a cosmopolitan outlook to do, but I do approach you on behalf of the local committee of Keren Kayemet, and convey to you our most heartfelt recognition for the international efforts you have made, and for all your great dedication on behalf of Keren Kayemet in particular, and as a recognition of your work, the committee, at our last meeting on 3 June 1927, has decided to present you with an award of excellence as a memento”.

This memento was a silver medal in the form of a Star of David, which on one side bore the inscription: “A memento from the Keren Kayemet Committee of Zelva,” and on the other side, “To E[liezer] Futritzky.” And in a like manner, he reads from a proclamation from the local committee, permitting me to display the medal, and a proclamation from the central committee of Poland, and also conveys thanks to me for my active participation as a member of the drama society of the local committee. He then gives me the proclamation, that was received from the central committee, that cites the fact that I had served as secretary, and asks all the international foundations in the Holy Land to offer me any assistance that is necessary. As all the attendees rise in their places, the Director of the Keren Kayemet, Nahum Helman, pins the medal to my coat.

The Director of the Zionist Histadrut, comrade Lev, reads the contents of the proclamation that was received from the central office of the Zionist Histadrut of Poland, as evidence that I had served as secretary of all the international foundations, and asks all of the Zionist Histadrut organizations to help me in connection with my settling and getting organized in the Holy Land.

Director Rosenbloom reads the contents of the proclamation received from the central office of the Keren HaYesod of Poland. They also read the contents of the proclamations received from the local Office of the Land of Israel, and the Tarbut branch, and place them in my hand.

At four o'clock in the morning, to the strains of Tehezaknah, and the Hatikvah, the celebration comes to an end. We left in high spirits, buoyed by the impact of the marvelous celebration.

My friend, Moshe'l accompanies me. He will spend the night at my home. How I feel the strong bond that exists between us at this moment. Just as I don't want to visualize the moment of parting from the members of my family, so I don't want to bring to mind the moment of parting from Moshe'l. It is difficult to take leave of all my friends, because we were all together like one body. But, there is a big difference between the rest of them and my dear Moshe'l. Moshe'l and I were as if we were one soul. His thoughts were my thoughts, mine - his, my secrets were his, and his - mine. Any little thing that was on one of our minds was immediately communicated to the other. It is difficult, oh, so difficult to take leave of a person who was a friend of this sort to me for 16-17 years, because we were already playing together when we were both two years old... but how much has happened during our lives since... it is equally hard for him to take leave of me - and he is spending this last night of mine in Zelva, sleeping over at my house. Moshe'l! Moshe'l! Will I ever - or will you ever - again find another friend of this caliber as we were to one another? Moshe'l! I swear before you, my dear and

[Page 59]

beloved friend, that we are only parted in body, but my soul...neither oceans nor days can remove my affection for you. Even from across the ocean I will remain dedicated and bound to you.

And let not my other friends feel that I am indifferent to them. It is equally difficult for me to take leave of you, but even you will have to agree, that there is a sort of difference between Moshe'l and yourselves... the bond of affection between my dear Moshe'l and myself stems from childhood days, when we still used to hit and cuff one another.

Here I am lying on my bed and thinking: I'm resting on my bed, in my mother's home, I see my house, I see my brothers, and sister, and the members of my family, my aged grandmother, and everything that is dear to me, and tomorrow, tomorrow morning, I will not see, either my home, the members of my family, my friends, and all who are near and dear to my heart. Mountains and valleys, fields and vineyards will separate us. I will have to be satisfied with just the pictures that I am holding in my hands.

Tomorrow, and the day after, if I'll want to see my home town, I will have to lie down on my bed, close my eyes and conjure up the image of the town in which I was born, Zelva!! Oh, Zelva, my Zelva!! And it was with these thoughts on my mind that I fell asleep...

I awoke at dawn. I remove the blanket from me, and I see that my mother is standing with a candle in her hand, and she is crying, crying, and tears are falling from her eyes, tears... and her tears - are falling on my heart...

My poor mother was up at dawn to bake me biscuits, presumably as food for the journey... and in the meantime, in going from the bedroom to the kitchen, she had paused by my bedside, and stood at my bedside and wept. When she saw that she had awakened me, she left me, because she didn't want to upset me. Ah, but my mother, my dear mother!

And the hour inevitably came. It isn't possible for a young man of eighteen to sit in his parent's home and to eat their food indefinitely as if it were charity. This is simply not possible. This time had to come, sooner or later, and the hour came to part. I covered myself with my blanket, and oh, so quietly, I wept over the fate of my poor mother... and I fell asleep...

10 March 1926

Tonight, I leave my home town of Zelva... all the members of my family are milling around the house lost in thought... what a condition there is today in our home! I am proceeding to collect parting best wishes from my near ones, friends and acquaintances.

Obtaining these good wishes was difficult for me, because who here did I not know? Isn't this a relative, that one a neighbor, the next one an acquaintance, this one went to school with me, that one I had a conversation with once, and in addition to all of this, in connection with Keren Kayemet, and Keren HaYesod, hadn't I visited nearly the entire population of the town? All day, I went from house to house...

At three o'clock, accompanied by my friend, Mordechai, I went to Rabbi Damta. I spent about two

[Page 60]

hours there, and we spoke of many matters, and after obtaining his blessing, a rabbinical blessing, he escorted me to the door, and we parted.

I came to see Moshe'l's father who was sick. I offered him my blessing that he should recover from his malady, and return to full strength. He thanked me, and burst out crying just like a little child. Needless to say, I burst out crying as well, and so did Moshe'l, his mother and sister. Everyone who was in the house wept, they wept like little children. Nevertheless, there was no choice. I left. Moshe'l and I, exiting his house and crying. We walk over to a side street so no one can tell that we are crying. We stood there for about 15 minutes and wept. Do you know what it is for friends to cry like this together?...

I remembered that I hadn't yet taken leave of my teacher, the principal of the Tarbut School, comrade, Motlovisky. I went to his room, but didn't find him there. He was observing the mourning period - his mother had passed away... I went to approach him in the synagogue, and I found him leaning over a book... I feel the tears rolling down my face, why? - I'm standing before my beloved teacher. Is he not one of those who instilled in me the very yearnings that I am about to go and fulfill... is this not the very synagogue in which my forefathers, my father, grandfather, the rabbis and gaonim, of blessed memory, spent most of their lives? This is where they gave thanks to the Lord for what ever good fortune came their way, or, heaven forbid, prayed in the event of misfortune. This is where they poured out the bitterness in their hearts... what a sanctified emotion seized me in those few minutes...

I took my leave of the Director of the local Tarbut chapter, comrade Rosenbloom. He was unable to see me off at the train that evening because he was not well.

And in this manner, I took leave of all my dear ones, my acquaintances and my friends...

I enter my house. My mother is sitting next to the table and crying... my old grandmother is sitting in the corner and weeping... I feel that any minute I will no longer be able to control myself, but I overcome the feeling. My mother gives me lunch - the last lunch I will receive from my mother's hands, but to my great disappointment, I take no satisfaction in eating it. I have no appetite at this time.

Again, I am hanging around outside and in the street, but I can't find any peace. I go into the garden, and stand on a little mound and watch the sun set. For the last time I see the sun set in my house... in my town... and it seems like the sun is taking its time in setting, because it too wants to keep me in good spirits...

And that is the way I stood for about a half hour, until the sun had completely set behind the mountains. I went back into the house. Inside the house they had already put up lights. The neighbors and relatives were beginning to gather in the house. The house gets fuller by the minute. All around, the women sit and chat with one another.

- what are they doing here? - why did they come? - to see me expire?...

I can't think in such surroundings. I want to be alone. I go into the bedroom, I think, and I feel that my heart is just filling up with explosive, and that any minute, it will burst, explode and spread all over. I regain control using all my will power.

[Page 61]

My friends come into the room and interrupt my thinking. Suddenly, my friend Bathsheba Bashkin from Dereczin comes into the house. She is a very close friend of mine. About two, or two and a half years ago, I met her when she visited Zelva. She is a young, beautiful and well-developed young lady. From the first time I met her, I was attracted to her. I would visit her home town of Dereczin frequently. Although I had many reasons to visit there, I visited for only one reason, Bathsheba...I love her...but it was a platonic relationship, two friends, and she has come to bid me farewell, and her arrival gladdened me considerably. We hugged and kissed each other.

Everyone goes out to the second room. I am left with my brother, Yitzhak [Izz]. We are talking to one another, when suddenly, he bursts out crying: “you are going away, leaving us, yes. How fortunate are you to be released from our abandoned and unfortunate household, but what will I do, I, what will I do?” I feel his pain, but it is not within my ability to comfort him, for I also desperately need comfort...

The clock strikes nine...

A carriage pulls up to the side of the house. They have come to take my belongings. My brother, Yitzhak, takes the bundles and suitcases, and rides to the train station to arrange the loading.

The first step has begun...

As they take the bundles and suitcases out of the house, my mother bursts out crying, and then my sister after her.

-My God! What will happen in another half hour?

The clock strikes ten...

The members of the Keren Kayemet committee come into the house, the Director, Helman, my beloved teacher, and family member, comrade Freidin, Potztiveh, their groups, and others...

I put on my overcoat. There is keening in the house. I brace myself. I begin to take leave of those in the house. I go around and around, and take leave of each one, I take leave of all the members of my family, my relatives, from my frail grandmother, who no longer has the strength to even cry, I take leave of them all.

An the minute that I feared finally arrives. My mother falls on my breast, hugs me and bursts into a bitter cry:

With this, I could no longer control myself, and I, too, burst out crying:

“Mameleh, don't worry! I am going to our Holy Land, to the Land of Israel. Only a short time will pass, and we will be together again”.

[Page 62]

We stood this way for about five minutes. My friends are urging me to hurry, and if not, I'll miss the train. We hugged each other again and in the company of my friends, Moshe'l and Mottel, I leave the house in which I was born, where I was raised and where I was educated. There are hundreds of people waiting by the side of the house. I go out of the yard, and everyone starts to walk. Suddenly, I hear the voice of my poor mother:

“Eliezer, Eliezer, my dear son! Please, come back just once more.”.

My heart melted. I turn back, and she hugs me yet again, and weeps with bitter tears... And again we stand for about five minutes, and everyone else is waiting. I think I also heard a silent weeping coming from the crowd.

I took leave of my poor, dear mother with a broken heart. Just now am I beginning to feel and understand what a mother is all about...

We, the young, do not know how to show our parents proper respect, at the time when we are under their care...

I walk ever so slowly, and I still can hear my beloved mother's groans. My heart shrinks from all the pain, and yet with a few more steps, my mother's voice becomes muted.

I turn to the edge of town, towards the side of my house, and look at it for the last time. I wanted to go back to the house, and to see my mother again, but I was concerned for my mother's health...

- Goodbye dear mother, goodbye friends, and acquaintances, goodbye, goodbye to all of you! I walk ahead, and I see before me how my mother is sitting at the side of the table and cries, and my heart, my heart is constricted with pain... and that is how we reached the half-way point.

And suddenly a voice wells up inside of me:

“Eliezer, Eliezer! You are going to the Land of Israel!”

-and everything changed...

In my imagination, I already see all of the Land of Israel, her blue skies, and all that is marvelous there... and I am making a transition from the present world to a world that is completely different...

With this thought in mind, I enter the railroad station. The station is full of people, who went ahead of us, there are acquaintances, and people who simply wanted to accompany us. After all, I am travelling to the Land of Israel... I find myself in high spirits. My friends did not imagine that I would be in this kind of mood at this time. Nobody believes that I am the one who is making the trip...

Another young man and young woman are travelling with us, but everything is centered on me...

Travelling with us is the Director of the Keren Kayemet of Dereczin, comrade Mollor, and his family.

The clock strikes eleven...

In the distance, the whistle of the locomotive is heard, as it draws near. I take leave of my friends and acquaintances, and now comes the third step... I take leave of my sister Rivkah... and again there is much crying and groaning. I am no longer crying. I am in a completely different frame of mind. I

[Page 63]

am going to the Land of Israel.

The train arrives, and they put my belongings onto the train car. My brother Mordechai [Max] will accompany me as far as Warsaw. Everything had been organized as it was supposed to be, and I went up on the first step of the train car to offer my best wishes to all those who came to see me off:

“Honored attendees, and friends!It is most unpleasant for me to take leave of the members of my family, my relatives, and the community in which I have spent eighteen years, but the idea is, that I am going to our Land, the Land of my wishes, the Land of Israel - this is my comfort. Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye, my dear and beloved ones. I hope to see you all once again in our Land, the Land of Israel that is being built! Goodbye to you Zelva!!!”

A clarion of “Hurrahs” burst from the hundreds of mouths of those that were gathered.

The train conductor closes the door and forces me to go inside the car. I open the window. The entire gathering is singing Hatikvah and Tehezaknah. In my heart I feel myself standing and growing strong, that I will not burst out crying. My sister Rivkah is standing opposite me and is crying. I gird myself... I stand as if frozen.

Suddenly there is a long whistle. The wheels begin to turn. Slowly at first, and then faster, shouts of “hurrah,” “Hazak VeEmatz,” “Next Year in Jerusalem,” burst from the lips of the onlookers, and for the last time, I look back into the faces of the people who guided me for eighteen years. The shouting and the noise still ring in my ears, and suddenly, it all changes, everything is transformed, and it is over.

Goodbye, Goodbye, Goodbye to You Zelva, and its Residents ! ! !

I sit down in one of the corners of the train car, and my brother, Mordechai sits opposite me. Both of us are lost in thought. Is my brother so deep into his thoughts about me? Most certainly.

A picture passes before my eyes:

A month ago, two months ago, three months ago, five months ago, we used to escort the Olim [pilgrims to the Holy Land] to the train station. On the way to the station , we would sing and dance. How great was the happiness!! And afterwards, in the station itself, came the parting... and here, the train comes. The singing of Hatikvah, and Tehezaknah, the train disappears, and we, with song on our lips, quietly, and still dancing, would return to our homes. How marvelous were our spirits at that high point...

And here, right now, I am sitting in a corner, entirely sunken in thought, and they - they are going home, singing and making merry, and their spirits are soaring...

Suddenly we hear a whistle... our train has reached Volkovysk, where my friends, Rosa Kabintovsky, Zina Levine, Gutka Lev, Merozinick, and another one whose name I've forgotten, and my friend Joseph Lipik were waiting for me. Again the whistle... we parted.

At each station, Halutzim were added to our ranks, and with them our spirits rose hour by hour. At

[Page 64]

each station we were greeted by a large crowd. Waiting by the side of the station were parents and relatives, that had come to escort their near and dear ones, and again there was song and dance... the atmosphere became more and more pleasant, but with the coming of the dawn, a sort of sadness settled on the faces of each person, a hidden sadness...

11 March 1926

We reached Warsaw at 7:30AM. We debarked at the Vilna Station as the city was beginning to rise from sleep. All the electric buses were full of people on their way to their places of work. On the streets, workers of every description were rushing to their jobs, carrying the tools of their trade. Automobiles were going to and fro. In a corner, a policeman was standing and rubbing his hands together. Little boys, selling newspapers, ran alongside the electric buses yelling “Heint, Moment, Courier Farang, Courier Krarbonie, Rabotnik”. Across from the station is a row of shoe shine boys. Warsaw is humming.

We got on the number 6 electric bus which goes to the Ogrudoba area. We are spending the night at the home of my brother's sister-in-law, Batia. She had already gotten up to go to work, and she handed us the Heint, which I started to read, and suddenly I saw my name in large letters: Eliezer Futritzky. It contained best wishes in the following language: [From the Yiddish]

“On the occasion of his departing journey, our best wishes to our co-worker in all the Zionist foundations and institutions, Eliezer Futritzky who is going to the Land of Israel, we offer him our wishes for good health and we wish him good fortune in our old-but-new home.His friends at the Zionist Histadrut, Keren Kayemet, Keren HaYesod, Palestina, and Tarbut Library.

Zelva, Vesten March 1926”.

Naturally, I was very happy to see this notice of best wishes. I took one copy of it and put it between the pages of one of my books in order to preserve it.

That same day, accompanied by my brother, I went to the central Eretz Yisrael office at Marzhinaska 10. I was examined by the physicians at the office, Dr. Fackar, and Dr. Lansky. I took care of all the issues regarding the Eretz Yisrael office. Thanks to my efforts, I was excused from paying the immigration tax of the government of the Holy Land, in the amount of between 7 - 9 dollars. That same day, I finished all my tasks, and I was ready to leave Warsaw, but we had to wait for a special train that was not leaving Warsaw until Sunday, March 14.

12 March 1926

We visited the home of Mr. Chaikin, the editor of the newspaper, Heint. My brother's brother-in-law was also invited to their home for lunch.

During the day, we walked the city streets, and visited many interesting places. That evening, we wanted to go see a performance of HaBimah, from Moscow that was touring Warsaw at the time, but to our great disappointment, we were late for the performance. Instead, we went to the Jewish

[Page 65]

art theater, Azel, at Danaga 50. The theater was very small. Only a couple of hundred people could fit in it. The subject of the performance was wonderful: On Israeli Dance, and the monologue was delivered by Gudik Parsheh Beigel.

13 March 1926

We visited the brother-in-law and sister-in-law of my brother, Mintz, and his wife, Masha, the sister of my sisters-in-law, Rivkah and Zipporah in Prague.

14 March 1926