|

|

|

[Page 5]

by Yerachmiel Moorstein

Zelva is a town in the Grodno Province, Byelorussia, in the U.S.S.R. By the end of the 15th Century, Jews were already living there, who from the standpoint of community organization, belonged to the community of Grodno. By the year 1600, Jews were already established in the town. Many Jews visited the town, among them, Rabbis and Elders of the community from Lithuania. In 1766 after the establishment of the Four-Lands Commission (“Vaad Arba Ha-aratzot”) a community was established that had to pay taxes to the commission, and 522 Jews paid this tax at that time.

In 1781, at one of the major fairs, the rabbis and leaders of the four communities gathered in Zelva. They were from the towns of: Brisk, Grodno, Pinsk, and Pluytsk. This meeting which took the place of a commission for the country of Lithuania, among other things, declared war on Hasidism. In the discussion, that included the Rabbi of Brisk, Abraham Katzenellenbogen, and the righteous teacher, Mr. Zelig, who brought a letter from Rabbi Elijah, the Vilna Gaon, the following resolution was adopted:

Signed by the community leadership at the great Zelva fair on the 3rd day of Elul 5541.”

In 1796, again during the days of the great Zelva fair, this terrible excommunication was reaffirmed. To the best of our present knowledge, this interdiction was fully observed in Zelva, and no Hasidim were known to have settled there. At the time, this part of the world belonged to Poland.

In 1793, Russia penetrated this area. At that time there were 846 tax paying Jews in the town. The Jewish population grew, so that by 1897 they numbered 1844 people, and comprised 66% of the town population. After the First World War, Poland was established again, and in 1921, the Jewish population of Zelva was 1319, representing 64% of the town population. Below is a table from the year 1897 that sets out the Jewish population in comparison to overall the total for towns in the Volkovysk valley, city and region:

| City | Total Population |

Jewish Population |

| Svislutz | 3099 | 2086 |

| Zelva | 2803 | 1844 |

| Piesk | 2396 | 1615 |

| Prozova | 2082 | 931 |

| Yaluvka | 1311 | 743 |

| Liskova | 876 | 658 |

| Izbalin | 963 | 454 |

| Amstibuba | 1228 | 389 |

| Novidbor | 1481 | 183 |

| Zalvian | 600 | 81 |

|

|

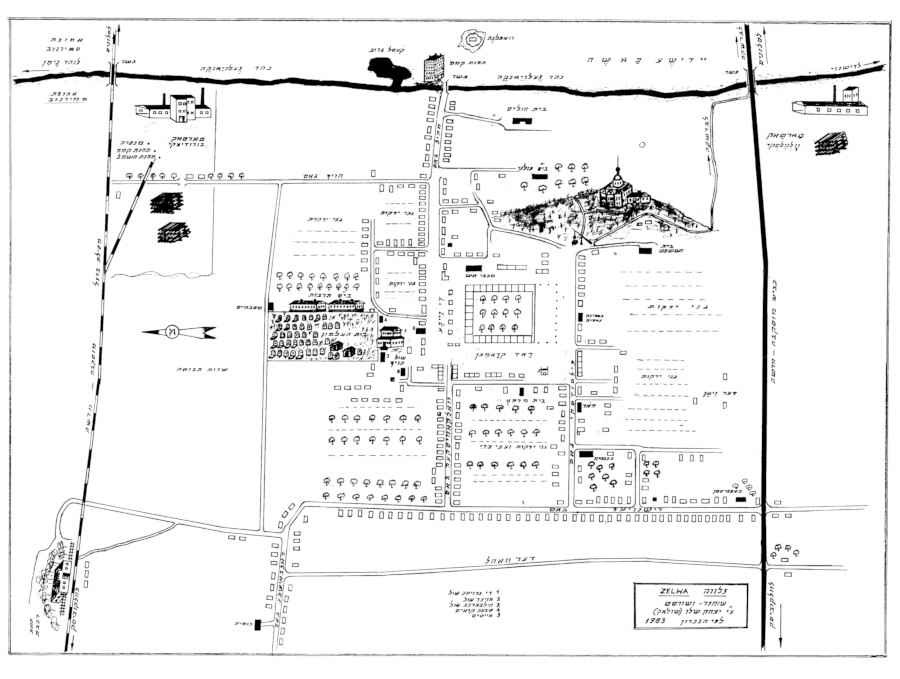

| A map drawn from memory by Yitzhak Shulyak |

[Page 6]

The demographic overview shows that from 1847 to 1897, the population of Jews in Zelva grew by about 1000, proving that this 50-year period was a period of growth, aided in part by the creation of the Warsaw - Moscow railroad line, on which Zelva was one of the stops.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, the persecution of Jews by the Russian government increased, and in particular, as a result of the failed uprising of 1905, in which Jews from Zelva also participated. Some were imprisoned, and those that had the financial means, fled the country. Many emigrated, in particular to the United States. There, they encountered the difficulties of absorption into American life, but they believed in the ultimate improvement of their lives, and strived to bring their families to them, and not to return to Russia.

The Bialystok pogrom of 1906, abetted by the authorities, caused much Jewish blood to be spilled. The concomitant deterioration in the economic and social conditions, accelerated the rate of emigration. That is why the Jewish population in 1921 stood at only 1319, despite the high birth rate among Jews, where it was typical to find between 6 and 8 children in a household.

Three of my father's brothers, one of them a revolutionary that escaped from exile, and also one of my mother's brothers, fled during this era. Their descendants are found today among the greater Jewish population of the world.

Zelva is found on the road from Warsaw to Moscow, on the banks of the Zelvianka River that empties into the Neman River. It is a town in the Volkovysk valley, with a railroad line, and a station approximately 20km from the larger city. A principal highway went past the town on its other side. Surrounding the town were tens of hamlets, populated by Russian Slavic peasantry with a Polish minority. In a few of these, Jewish families lived for many generations, some as estate managers for the local nobility. Jews also found sustenance by working in the large forests of the area. Because of its strategic location, this area did not escape the wars that took place in the area, nor the other upheavals of the time, whose mark was seldom low-key or light-handed.

During the First World War, as the German army began to move forward and captured several fortified areas held by Russian troops, panic set in among the Russian peasant population along with a desire to cross into the heartland of Russia. Many refugees remained behind without anything, or those who abandoned their possessions. A similar fate befell countless Jews who dwelt along the extensive boundary between Russia and Germany. The Germans forced them to leave their homes, and that is how many came to our area and in the course of fleeing, came to settle in Zelva. In short order, the Jews of the town gathered their persecuted brethren, and offered them a variety of assistance. When the Germans captured the town of Zelva, the ties to the surrounding towns and cities were cut, and with no sources of sustenance, economic and commercial activity came to a standstill, and the Jews began to suffer from hunger and deprivation. Under these trying circumstances, disease became rampant, and intestinal typhus claimed victims without number. The epidemic raged unchecked by any form of medical care, and only the medical corps of the German army was able to arrest the disease and its death toll. Those who survived continued to suffer.

[Page 7]

The German Occupation

The Germans occupied these territories for about three years. They attempted to enforce law and order, and set up a commission, headed by a German-speaking Jew. A school was opened. The Jews began to feel an easing of their condition with reconstruction, and a return to a normal routine. However, it became rapidly clear that the Germans were exploiting the commission for their own purposes. They employed forced labor in the forests, and confiscated whatever the local citizenry had. In this way, the general want and absence of food intensified, and hunger reigned. These were years of want and suffering.

The First World War that claimed many millions of lives and brought loss and destruction, aroused more and more resentment and opposition in the armed forces. In 1917 after the Bolshevik Revolution, the killing of the Czar and his family, and the initial formation of the Kerensky government, unrest spread also to the German army. The fronts began to crumble, and the German soldiers unused to the intense Russian winter, with erratic supplies, began to desert the front and return to Germany with the Bolsheviks at their heels. In the town, a communist government was set up, including some townsfolk, but it didn't last long. At the same time, the Poles organized themselves into combat legions, and a new war was underway. Between wars, when no formal government was in place, various factions ruled according to their own means, generally terrorizing the populace, pillaging, plundering and stealing from whomever was around.

The Gabbaim of the Beth Hamidrash were also the community leaders. The most honored position was occupied by the Rabbi of the town. He maintained the town records. He recorded all the births, arranged wedding ceremonies, made rulings by clarification (Jews did not utilize secular courts), dealt with questions of kashruth, in particular in slaughterhouses, and also dealt with liberating Jews. The Rabbi lived in a house adjacent to the synagogue, and his modest income was supplemented by the sale of miscellaneous religious articles in addition to the above services.

The second individual, without whom it would not have been possible to maintain a community life, was the Cantor. He generally served as both a Mohel and a ritual slaughterer which provided him with his livelihood. For the High Holydays, he would generally organize a choir that assisted him with services. There was, to be sure, a Hevrah Kadisha, or burial society, that dealt with the ritual of funerals and burial. It was a volunteer organization. Relatives of the deceased were assessed according to their means to cover funeral expenses, and the digging of graves, in particular in winter, when the ground was frozen.

As to community matters, such as care for widows and orphans -- whose numbers increased after the war -- there were ombudsmen. Women of charitable disposition would make collections from townspeople for this purpose, each according to their ability. Laskeh Freidin, the grandmother of one of our Israeli families stood out as one of the exceptional ombudsmen of this nature.

For Passover, the community organized a Maot Hittim campaign for the needy. Before the High Holydays, bowls were set out in the synagogue for contributions to a variety of causes, the larger portion being for the Holy Land. In one corner, there was an alms box for anonymous gifts, which

[Page 8]

always used to fill up. The donors rarely cared for recognition...

There were also special collections taken up, for example, if a wagon driver lost his horse. A special collection would be taken up to buy him a new horse, so he could continue to earn even that meager livelihood.

The synagogues were always full of volunteers who carried out the duties of leading prayers, reading the Torah, and blowing the Shofar on the New Year. The cantor never had a difficult time obtaining recruits for a choir, which always practiced for several weeks before the holidays. In addition, the young people would make collections for Keren HaYesod and Keren Kayemet by going house to house, and even the needy always made an effort to help fill up the box.

The Shulhauf as a Spiritual Center

The synagogue, or Shul square was the heart of hearts of the town. It was here that all the buildings of the community were centered. The single synagogue of the town was built of bricks and stone. This most beautiful of buildings was tall, as were the windows that were cut from stained glass. The ark was the handiwork of an artisan who, according to oral tradition handed down for many generations, dedicated decades of his life to its completion. He slept in the entrance, and the righteous women of the community looked after his modest needs. By hand, he created and connected by primitive means (before electricity was discovered) an absolutely miraculous piece of artistry: when the ark was opened, one of the figures of a Lion of Judah would present a Torah scroll grasped in its paws, and above the open door of the ark, winged figures would flap their wings, accompanied by the sound of cymbals and drums. A picture of this holy ark has been preserved, and may be found on page 65 of the Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume IV. Legend has it that the honor of opening the ark was accorded to a distinguished visitor, who upon being confronted by the image of the lion holding the scroll, expired dead on the spot. From that time on, the mechanism that moved the lion was disabled, leaving the lion immobilized within the ark.

Every community affair, even family matters, coursed through the Shulhauf. A town Jew lived his entire life here, from cradle to grave. As he was born, his arrival would be announced in the synagogue. Here is where he would have his Bar Mitzvah. And as a groom, led to the bridal canopy up the main street, additions to his family, with the local youth, and with the fire department orchestra, that was established in later years. A bridal canopy was erected in the center of the Shulhauf, and all the participants -- and who was not a participant -- brought happiness, joy, and hearty good wishes to the new couple. And it was the same, God forbid, when a member of the community was taken from us. It was rarely necessary to publicize such news, because it traveled immediately from one end of the town to the other. The entire town shared in the grief of the bereaved family, and stood ready to offer support in whatever form was required. When the deceased was taken to the final resting place, all the stores in the town were closed up. The remains of the deceased were brought to the side of the synagogue where he was accustomed to pray, and the Rabbi or the Dayan would eulogize him with feeling, and the women would openly weep for him, and the entire square took on an air of great sadness.

During the month of Elul, the square was full of people, when everyone, including children, would come for Selichot prayers late at night with lanterns in their hands. During the High Holydays, during recesses from prayer, the square would fill with Jews wrapped in their prayer shawls. These were

[Page 9]

especially observant, and would wear their prayer shawls to and from home, not relying on the Eruv to permit them to carry the article back and forth...

In the religious schools, there were always nameless yeshiva students, whose needs were cared for by charitable women. It was a given to hear the sing-song of learning pouring out of the school, as well as loud, argumentative reasoning being exchanged between Talmud students. Among the young yeshiva students, there were those who were attracted to the enlightenment (Haskalah), but they had limited success in disseminating this school of thought to the very traditional town residents. The founding of the Zionist Histadrut movement kindled an interest in Hebrew language. It was the Bet Hamidrash that nurtured this interest in Hebrew in the period before the Tarbut and Tachkemoni schools were established.

Every Bet Hamidrash was amply endowed with scholars and bookcases overflowing with religious texts, and at every opportunity, especially between Mincha and Maariv prayers, these scholars would give a Gemara or Mishna lesson to the lay townspeople, that would listen with great interest. Specialists in holy articles would be brought from the “big city,” though in town, there lived Leibush the Scribe, whose occupation was to write Torah scrolls.

The town youth was well occupied with culture, politics and literature. Seasonal visits by the leadership of these movements served to spur on the youth of the town. The idealistic teachers in the town added their own impetus which was not lost on the young people. Despite this, the Jew in this land felt alienated; he was born there, as were his forefathers, yet the future looked gloomy, and the potential for life as a free and independent Jew seemed very, very distant indeed.

The Fire Department

The fire department was nominally a municipal organization, but in fact, its membership, except for the Chief, was made up of Jews, and they also established the fire department orchestra. There were meager fire fighting supplies -- several hand held pails and troughs, a storage area in the center of town that also served as a theater.

When fire broke out, the firemen would gather, and townsmen that owned horses would assist them in order to bring what little equipment they had to the scene of the fire. Understandably, most of the time they were late in arriving, and it was just the wind blowing that would cause the fire to spread...

The Orphanage

The war [World War I] left many youngsters orphaned, and led to the establishment of an orphanage. Young men in particular were drawn to offer assistance to those in need. Even American Jews committed themselves to this objective, and through the Joint Distribution Committee, they sent supplies of foodstuffs. A public kitchen was erected from which hot soup was dispensed, that put some life back into otherwise dried out bones...and on top of this was added the worry of how to teach them Torah.

In the absence of a hospital, pharmacy or even a doctor, it was Epstein the Feldsher, who offered medical assistance to most of the sick in the town [Eastern European Jews referred to Medics by this

[Page 10]

German term -JSB]. He would go out in all sorts of weather, with his bag in hand, and he gave a little cotton, iodine, quinine, and aspirin tablets. Those who caught cold, would have a need for cups (bahnkess), that were applied by women with facile hands that were skilled in applying the cups with a warm, and reddening pressure to the sick person's back, and if all this didn't help, then the afflicted departed this world, and not necessarily because of advanced age...

Occasionally, a seriously ill person would be taken to the district capital (Grodno?) or even to Warsaw to the Jewish hospital there. The expenses for such care were borne by the community at large.

“Sleep-In” with the Sick

This group supplied assistance to the sick. At night, two young men were assigned to come an sleep in with the sick person overnight.

Daily Life

Most families were large, and blessed with many children. They lived in simple houses that passed from one generation to the next by inheritance. Attached to the house there was normally a stable, or also a pen for domestic animals, and also a woodshed. Behind the house there was a small plot of land, on which there were several rows for planting vegetables, and also fruit trees that had been planted toward the end of the eighteenth century as a gift of the philanthropist, Baron Hirsch. On the edge of the town along the banks of the Zelvianka River, there was a stretch of about 100 dunams of land that served as a natural meadow for grazing animals. This land belonged to the Jews. Jewish shepherds would put their flocks out to graze in this meadow.

The Water Well

It was located in the middle of the square, and provided water for home use, and during fair season to all visitors, animals, even in the winter when the well was entirely encrusted with ice.

The Bath House

It was opened only on weekends. Each family followed the custom of bathing according to a set schedule. In those days, there were no bathtubs or privies in the individual homes. After several hours of scrubbing with a “brush”, washing with near boiling water, and rinsing with cold, one would return home clean and fresh. This contributed significantly to the health of the resident population. In the summer, people preferred to bathe in the river, and as a result almost everyone knew how to swim.

[Page 11]

The Ice House

This was a wide cellar, at the edge of the Shulhauf square, where several hundred tons of ice were stored, having been cut from the Zelvianka River, and moved to storage by volunteer labor in wintertime. Full of ice, it offered a respite in the summertime, apart from being mandatory for the sick to control fever. To put some ice on the forehead was the sought after remedy. The demand for ice was greatest at the time that the city was beset with severe illness, in particular after the German occupation, when typhus became endemic, and countless people died. The ice was the single medium that brought some relief amidst terrible suffering. During summer, the ice was also useful in preserving various foodstuffs, and in the manufacture of ice cream, by somewhat primitive manual methods.

Diet

Diet was not particularly distinguished. The principal staple was bread, corn, and small potatoes, and in the fall, some fruits and vegetables as well. Even rotten fruit was eaten, nothing went to waste. The well-to-do obtained cucumbers and cabbage, and stored them in their cellars for the winter. Meat and fish were eaten on the Sabbath or Holidays. A cow or nanny goat would give milk on most days, but in limited quantities.

There was never any concern about becoming overweight. The only one who needed to diet was a storekeeper who sold woven goods that he obtained from Lodz, the manufacturer would come with notes that he would not honor...

Clothing and Footwear

Many were involved in this area, and goods were plentiful and of good quality. There was heavy trade in woven goods, furs, and skins. Over the many years of war, large numbers of domestic animals were killed or eaten. By contrast, cotton, plastic, or synthetics were rarely heard of.

The farmers did not use shoes, and only in the winter would they fashion wooden sandals. The townspeople in particular suffered. Every item of clothing was handed down and fully utilized.

The Sabbath suit of the head of the household was turned inside out after several years of wear, and that's how its use was extended...

Zelva was already known as a city of commerce by the beginning of the nineteenth century. In those days, Jews would bring fruit, animal hides, and horses from Moscow and other cities. Because Zelva's location was between the main road and the railhead, the location became well known, and the merchants from the surrounding area, and even from more distant locations, came to do business. Consequently, the Zelva fairs became well known events. At the crack of dawn, thousands of farmers would descend on the city, by cart or on foot to the fair, to secure a good place in the gathering with the livestock.

[Page 12]

The whole town prepared for the fair which was a source of anticipation for weeks in advance. About half the Jews of the town were either merchants or storekeepers. The commercial center of town was built in a square, and the property was owned by a German family that had been invited to settle there by the Russian monarchy. This family charged rent to the occupying merchants, and even to the adjacent homes, on three sides of the square, the fourth side being set aside for the livestock market.

The selection of merchandise in the stores was modest and limited. The principal buyers, household suppliers, made do with the minimum. Most families with lots of children, even the farmers, were sober folks. While prices were low, this also meant that income was also low, though there were merchants and storekeepers that succeeded in their business despite the unreasonable pressure of the municipality. The tax rate was very heavy. The tax collector, Grabski, became famous for his “squeeze,” and no small number of Jews emigrated from the town as a direct result of his tactics. This aliyah was therefore called the “Grabski Aliyah”.

There was commerce in grain. Fortunately, the city was also a railhead, and the farmers of the area and landholders brought their produce there to be sold to merchants, and several tens of families prospered in this regard. However, in the beginning of the 1930's, with government instigation, a grain cooperative was established to provide jobs to new residents, who were Polish war veterans, and in this manner, Jews were pushed out of this important branch of economic activity.

Cattle traders did a good business, since they were suppliers to the army. Butchers that catered only to the general population did only a modest business, since people refrained from meat consumption during the middle of the week. Only on the Sabbath, or holidays, did meat appear on their tables. Only the well-to-do or the sick used to buy fowl that the farmers used to bring to market from time to time, which gave rise to the joke: “when does the pauper eat chicken? when one of them is sick..”.

Wagon peddlers would leave with their rigs on Sunday, and return on Friday for the Sabbath, going from village to village, and bartering their wares for agricultural produce.

Fruit merchants also tended the orchards of the nobility during flowering season, and would guard these orchards until harvest time, protecting the harvest from theft. They would deal with the crop honestly, storing the fruit and selling it for a good price and returning the profit.

The wide forests provided a livelihood for any number of Jews. Two sawmills were constructed on the banks of the Zelvianka River. The better one belonged to the Borodetzky family, several of whose descendants live in Australia, and one in Israel. The second one was built by the Jews of Volkovysk. There were also several lumber merchants. The Spector family constructed a building for this purpose in Warsaw, and did very well. The family son, Sandor, lives today in Australia. He saved himself by jumping from a train car on the way to the “Valley of Killing” (e.g. Treblinka)..

The only flour mill in the area also belonged to the Borodetzky family. All the townsfolk had need of it, including the Jews. Most families used to bring their grain to be ground, and used to wait in line for several days. The mill ran by water power, from a dam across the Zelvianka River. The most expert millers were the Jews.

[Page 13]

|

|

| The Holy Ark in the Great Synagogue of Zelva |

About five families ran bakeries, and they provided a variety of baked goods, especially to the farmers who came to market. Town residents, including the Jews, baked week to week, filling the ovens with loaves of bread, weighing 5 to 6 kg. apiece. The well-to-do also baked challahs for the Sabbath.

Immediately after Purim, the ovens in two of the bakeries were koshered for baking Passover matzoh. The rest [was baked] in ordinary homes. The families and their branches, organized and expedited all the work among themselves. The womenfolk in white aprons, with kerchiefs covering their hair, and even young men and the boys, participated in this undertaking. The matzoh was brought home in a white case. Under the roof was a wooden cache for storage. This had served for storing matzoh, meal, and flour for matzoh balls (knaidlach) for more than just one generation.

Jews engaged in the distribution of goods by running horse-drawn wagons. Several worked as teamsters, hauling to and from the train station, though mainly, they were employed in hauling merchandise to the city, the valley, and from there. Important cargo, destined for the capital city, such as grain and lumber, were taken only as far as the railroad station, where they were loaded on train cars.

The cooperative bank, which was founded by the efforts of several businessmen, breathed life into the faltering economy. The high level of trust in the bank leadership attracted funds for dowries and savings, that made it possible to extend loans to local businessmen. In the capital of Warsaw, a banking center was established along these lines that assisted with organization and audit.

Several people engaged in the exchange of dollars into gold. A sense of obligation, and concern for family, motivated Jews in America to send dollars to their needy relatives. The standard method of transaction was to exchange the note for a letter in a folio, and the “Men of the Bourse” would then exchange it for gold.

There were hardy souls who engaged in the liquor trade, literally taking their lives into their hands to bring hard liquor to saloons, despite the express prohibition by the government. The trade in alcohol was legally limited to wounded war veterans.

Several families were engaged in the building trades utilizing both lumber and bricks. The flour mills in the city and environs were their handiwork. They also repaired millstones and engaged in their care.

Giving Birth...

The concept of a maternity hospital was unknown. Instead midwives, drawn from the local populace, attended the expectant mother. Birth was facilitated in the home of the expectant mother. The newborn received his first bath in a bowl of warm water. If the infant was a baby boy, then an excerpt from the Book of Psalms, including the entire chapter of Shir HaMaalot, was pasted on each of the four walls of the room. This was the tried and true method of providing a watchful eye over the newborn and the mother...

Members of the immediate family were nearby, ready to spread the good news. Like an arrow loosed from a bow, the news would traverse the entire town, and after Mincha, children and their parents would gather at the home of the newborn to recite the Shema, and Shir HaMaalot, to strengthen the

[Page 14]

protection of the Almighty. All the invited guests contributed something for the occasion, and the rich also added candies. And from the attic, would be brought down a wooden cradle that had also served this purpose for many a generation. The infant was wrapped in swaddling clothes up to his neck to assure that he would have a straight and tall body. His mother would then nurse him till he was full, and afterwards, he was put to sleep without much trouble...

The status of the male infant changed on the eighth day, when, amidst a holiday atmosphere, and with the participation of his immediate family, the Rabbi or the Dayan, the Mohel performed his rite...and at the same time, his name was announced publicly, usually in memory of a departed grandfather or other relative.

From this day onward, the Jew began to writhe in agony and suffer... to ease his pain, his mother would rock the cradle, and if that didn't help, she would open his swaddling clothes and pour a little powder on him, her offspring lying frail, and wrapping the squalling infant up again, and, heaven forbid, he should start again... the mother would nurse her child until he started walking. He would be weaned when he began to bite the nipple he suckled on, with teeth that would have grown in the meantime...

The City of Zelva

Zelva served as a center to hundreds of villages, and was the seat of local government whose head, understandably, was an appointed Polish Christian, assisted by several deputies. The courthouse, post office, railroad station, the teachers in the public schools, the five policemen, and even the doctor sent by the central regime--all were purely Polish in character.

Two Russian Orthodox churches, and one Polish Catholic church were a magnet that drew the farmers that came in throngs to the pealing of their bells during Christian festivals.

Only the main street had any stone paving, and at that only partially so. There were no steps, and during the rainy season, or snows, one constantly had to slog through muck and mire. In summertime, and during harvest in the meadow, and in particular on return from the fields, the skies would fill with clouds of dust.

Most houses were one story high, built of wood. In the city center, there were some stone houses that had a fortress-like appearance. These served as watch stations for soldiers.

The commercial center, that was built as a square, was a center for storekeepers as well. Attached to the store was a modest dwelling for the tenants, and it had windows only on one side. The heavy stone walls served as a fortress to the standing army. Around the center, especially in the fall, wagoners would set up stands to sell fruit and baked goods.

During the season for military draft, the gentiles would gather the drafted peasants in this area, and after a ration of vodka, they would try to make merry, and in the process end up vandalizing and wrecking these stands, but these depredations did not last a long time. The braver butchers and wagoners took the fight back to these perpetrators and drove them off into the countryside...

The Tarbut School

World War I left orphans, destruction, poverty and disease in its wake. Sources of livelihood were cut off, shops were left bare, after they were pillaged at the hands of invading troops. Craftsmen went idle.

The new Polish regime began to establish itself. Among its directives was the adoption of the Polish language. A public school was opened that accepted students free of tuition. The Jews, however, did not accept this development enthusiastically, and continued to send their children to Heder. Among the refugees that had left the city, was a Hebrew language enthusiast, Yehuda Halevi Epstein. As a result of his energy, and with the assistance of several fathers of young children, he managed to continue to organize and provide a school for instruction of Hebrew--in Hebrew--in his own home. I was among his few students. But, to our great consternation, there was insufficient encouragement offered to him, and he left us amid groans of disappointment, and returned to his town, Slonim (may his memory be blessed!). He was among those who laid the foundation for education in our universal tongue.

The responsibility for the education of Jewish youth , especially in Hebrew language, occupied many good people, but there were also many who were very devoted to Yiddish - and the Bundists, and radical Leftists, to whom the study of Polish was mandatory. The establishment of a Hebrew School was a very difficult undertaking, but there were supporters to be found, men of vision, and idealistic teachers, who satisfied themselves with very modest life styles, and they opened the Tarbut Schule. As we have previously pointed out, in this period, most parents had rather large families, and not much in the way of means of support. It was in these circumstances, with the dedication of all participants, that this school began to accept students, make progress, and grow. From very little, in time, the number of students grew, and the level of instruction rose as well. And we, the youth, sublimated our desires, in order to master this treasured language of ours. This arduous undertaking, however, did bear fruit, and the Hebrew language became the heritage of the younger generation.

The Tachkemoni School

There were Jews, however, who were not satisfied with schooling limited to Hebrew language, and with the passage of time, they established the Tachkemoni School whose objective was to impart to the student tenets of faith and studies in Holy Scripture, in addition to skills in language. This institution, as its predecessor, flourished because of the dedication of its founders and teachers.

Several Hebrew newspapers, such as HaTzfira were still being received before the War, however, afterwards, in its place, we began to receive the paper, HaYom. It would pass from hand to hand, and we would devour its contents down to the very last...

With no framework for studies available to our generation other than the Heder, and with an overpowering desire for enlightenment, we decided to establish a library. To this end, we went out in pairs, from house to house, to gather books from whatever was at hand, and after taking inventory and cataloguing the books, that were donated with pleasure, the library became a source of enlightenment that was not a disappointment.

[Page 16]

|

|

| Organization of Fire Fighters - Zelva 1928 |

In addition, the library served as a meeting place and a location for intensive Zionist activities. The old Talmud Torah building that served as an annex to the Tarbut Schule, also housed the library.

The Wealth of the Enlightenment

From an early age on, little boys would follow their older brethren to the Bet Hamidrash, to listen to Torah lessons between the Mincha and Maariv prayers from a Maggid, or to sharpen their thoughts along with their friends in games derived from their discussions. On reaching the age of five, the young boy began study in a Heder, and would even participate in prayer. Studies were conducted in the home of an instructor, called the Melamed, around a long table. The students would be bent over their texts and copybooks, sitting on long benches without backs, and despite the crowding, found the ambience pleasant. The period of study extended from Passover to the New Year, and back again. Recess from study was only during holidays.

After several periods in the Heder, individual students or small groups would continue to study with some teachers for an hour a day or every other day. The following teachers especially endeared themselves to their pupils: Joseph Matlovsky (today, Matlov, in Canada), Moshe Lubetkin (today in America) and also Shmuel Boruch Freidin who died in the Holocaust.

The desire for the riches of the enlightenment impelled others to leave for the big city to study in a Yeshiva under extenuating circumstances, because not all had subsidized eating arrangements. These were arrangements whereby a student would eat his meals, first one day with one volunteer family, and the second day with another such family, and so on.

By the time he reached Bar Mitzvah age, even before the formal ceremony, which took place in the Bet Hamidrash, he already had mastered the ritual for putting on the Tefillin (Phylacteries). This, he normally learned from the older boys, who took him into their group. He, feeling that from now on he was qualified to fill out a Minyan, found that to be more than an adequate source of pride. The wealth of this subject matter occupied him for a lifetime, because there was no outlet for him in ordinary places of employment, because those were exclusively for the Poles. It was the youngster's refuge, and he belonged to them, and that is where he dedicated the majority of his time and energy.

Just as in all the cities of Eastern Europe, so in Zelva, there was an awakening and a ferment in the Jewish community in the aftermath of the First World War, especially after the Balfour Declaration. In it, many saw what they thought would be the beginning of the Final Redemption, the only ray of light in an otherwise dark and dismal era.

The Zionist Histadrut movement made much of the opportunity. The large majority of the youth sought to affiliate with one or another of the Zionist branches that were nurtured by dedicated partisans. Even the fund-raising organizations like the Keren HaYesod, and the “blue box” of the Keren Kayemet could be found in almost every home, and every family repeatedly would even deny itself necessities to assure that it could contribute a few pennies in order to redeem precious land in Israel.

In a collection for Israel, a representative from the Holy Land, Dr. Yaffo spoke, and motivated the women of the community to donate their jewelry in addition to the donations of the men. The education of the children, especially after the War, occupied many qualified people, and when it

[Page 17]

became possible to go to the big cities, the young people of our town, Zelva, began to leave for centers of learning despite the difficult economic circumstances of most Jews.

The following is a list of those who left, and their destinations:

Dina and Leib Lantzevitzky - To the Tarbut Gymnasium in Bialystok.

They live today in the U.S. Dina runs a pharmacy, and Leib Lantz is a dentist.

Rivkah Shulyak -To the Tarbut Gymnasium in Bialystok.

Leibel Kaplan - To the Vilna Polytechnicum.

After completing his studies, he crossed the border into Russia and joined his brothers, Chaim, Benjamin, and Pinchas, and his sisters, Lifsha and Hadassah, who were active in the establishment of the socialist-communist regime.

Sandor Spector - One of the Holocaust survivors, to the Vilna Polytechnicum, lives today in Australia.

Yaffa Spector - Sister of Sandor, also a Holocaust survivor, studied at the Vilna Tarbut Seminary. She also lives in Australia.

Akiva Shevisky and his sister Esther - To the Grodno Seminary.

Yocheved Shertzuk - To the Grodno Seminary.

My sister, Sarah Moorstein, and Nehama Slutsky - To the Tarbut Seminary in Vilna. My sister studied at several schools, and was considered a gifted schoolteacher. She was killed in the Holocaust, while serving as a principal of the Tarbut School in Slonim.

The sisters, Dvora Geiger, and Haya Meiner (née Srybnik[1]) went to Slonim to study at the “Kunitsa” gymnasium. They both emigrated to Israel, and were devoted to one another as sisters from childhood days. They both raised families. Today they are active in a variety of community affairs, including the production of this Memorial Book.

Shlomit Becker (today, Laykin) - To the “Kunitsa” gymnasium in Slonim.

Chaim Jonah Freidin (today, Gilony) - To the Hebrew Tarbut Gymnasium in Volkovysk [where he was a classmate of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who came from Ruzhany. -JSB]. He emigrated to the Holy Land in 1933, and is a lawyer by profession.

Dr. Nahum Gelman (Nathan Helman) - Emigrated together with his family to Canada, and is a dentist. Today, he lives in Jerusalem, Israel.

Joseph Kaplan - To a Yeshivah in Vilna, and lives today in the U.S.

Isaac Nahum Gerber - To a Yeshivah in Vilna, and lives today in the U.S.

The game of soccer was just becoming popular, and all the boys, even the older ones, were eager to participate. Practice was then organized outside the city, near the lime pits of Bezalel Lisitzky.

After intensive practice, it was decided to invite the soccer team from Dereczin for a game. And, on the appointed day, while we were still waiting for the opposing team, we suddenly realized that the entire playing field had been covered with flax to be dried! We didn't think much of it, and we approached the cleaning of the field with great vigor. The game began when the curious had gathered, standing around us, and we then spied from a distance, a crowd of farmers with sticks and clubs in their hands, coming to beat us up. This precipitated a flight of the onlookers and players to town, and it was then that the chief of police got involved, and he ruled that we had to make good to the farmers for the spoilage of the flax. But where would the money come from? The only solution was: each player would have to donate two weeks of labor in mucking out the stables, and this donation of labor would be accepted as reparations.

Man lives not by bread alone, and as a result, a theater group was established. It was a group of young people that volunteered to do this. Heshan Zalman, a new town resident, was the stage director, and his assistants included Hannan [Elchanan] Potztiveh, among others. The players included:

Jacob Moshe Einstein, Hashka Kaplinsky, Jacob Rotner, Joseph Freidin, my sister, Esther Moorstein, Tuvia Vishnivisky, and the Lifschitz sisters.

With the fire of youth only, they embarked on this undertaking, without props, and even without a theater hall, and behold the miracle: after several weeks of intensive work a stage was constructed speedily, in cooperation with the fire fighters. On one side, a prompter's box was constructed. Benches were borrowed from houses in the neighborhood, and voilà -- a theater.

The play, Mireleh the Milkmaid was a success. All the participants, the director, the prompter, the players, entranced the audience, and from behind the scenes, we applauded the performance - Potztiveh, Tuvia, and I with violin playing - the emotions ran very high. The extended reaction of the audience lasted until the following performance.

From time to time, evening dances were also scheduled, and members of the Christian community would also participate, such as the doctor, the lawyer and the chief of police.

Translator's footnote:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zelva, Belarus

Zelva, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 18 Nov 2021 by LA