|

|

|

[Page 24]

Zabrze Following the War

Edited by Phyllis Oster

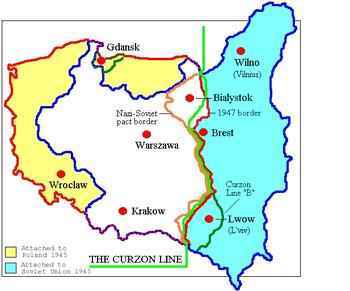

With the end of the war, the Soviet army ruled Hindenburg but soon handed over the city to the Polish administration in accordance with the Polish-Russian agreement based on the Yalta agreement. The Yalta conference was held in Yalta, Crimea, the Soviet Union. The participants consisted of Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union; Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the United States; and Winston Churchill, Britain. The conference took place February 4-11, 1945, and was supposed to settle the postwar European border issues. One of the most difficult issues was the frontiers of Poland. The Soviet Union or rather Stalin insisted that the areas that were invaded in 1939 by the Soviet army remain in Soviet hands. He insisted that Poland be compensated on its western border with Germany. Thus the blue areas on the map would become part of the Soviet Union and the yellow areas would become part of Poland. Stalin refused to budge on the issue.

|

|

| Poland's old and new borders, 1945 according to the Yalta Conference |

Roosevelt and Churchill had to accept the Soviet demands since the Soviet army had already liberated most of Poland and was in control of the areas in question. The Polish government in exile in London refused to accept the decision but could do little to alter the situation. Their opinions didn't matter to Stalin; he signed an agreement with a Polish committee that he created in the Soviet Union. The committee later became the provisional government that consented to the new borders and followed the Soviet army into liberated Poland. With the liberation of the city of Lublin, the provisional Polish government began to administer the liberated parts of Poland. The government moved to Warsaw when it was liberated.

The Polish-Soviet agreement had an important clause that stated that all Polish residents, even if they were forced to become Soviet citizens, could leave the areas that were given to the Soviet Union and move to Poland. Polish institutions like orphanages or old age homes were also given the same privileges. The Jews who survived the Shoah in these areas were also given the option of staying or moving to Poland. By the thousands, Poles left the ceded areas; in many instances they were forced to leave and moved to Poland. A majority of the population of the transferred areas were Ukrainians and Byelorussians who could not leave these areas. As a matter of fact, Ukrainians or Byelorussians who lived within Polish areas were also given the option to move to the Soviet Union. There were large Polish populations primarily in the cities such as Lwow or Lemberg, but their number in the rural areas was much smaller. The Polish government directed the flow of Polish refugees to the new areas that it had just acquired. Transport trains of Poles began to arrive in the new areas. They were joined by many Poles in Poland proper who saw an opportunity to advance themselves economically. The Polish government expelled the German residents of the areas and provided housing, jobs and other financial inducements to the Polish newcomers. The government was determined to “Polonize” the areas as fast as possible.

Many demobilized Polish and Soviet Jewish soldiers settled in the new areas where life was easier than in Poland proper where a wave of anti-Semitism began to spread. The Poles resented the present Communist-dominated Polish government that also happened to include a few Jews such as Jakob Berman, something that would not have occurred prior to World War II. Berman and other influential post holders were also members of the Communist Party. The Polish government in exile in London waged an active campaign against the government in Warsaw and used the Jewish office holders as proof that Jews controlled Poland. Furthermore, the London government claimed that they were not Poles but agents of the Soviet Union sent to rule Poland. The Polish masses bought these lies and the countryside supported the nationalist Polish elements. The government controlled the major cities and the new areas where the residents received many incentives. The Poles resented the loss of territory and the border changes.

Britain and the United States tried to mediate between the two Polish governments and managed to arrange a shaky agreement whereby some members of the London Polish government were assigned posts in the government in Warsaw. Stalin was determined to rule Poland regardless of Polish feelings. The nationalist forces fought the government everywhere; they even used weapons in an attempt to bring down the present Polish government in Poland. Jews were removed from trains and killed. Others were urged to leave their native places or face serious consequences. Many Jews decided to head to the new areas where there were already larger Jews settlements such as Wroclaw or Breslau, Gliwice, Bytom, Walbrzych or Waldenburg and Szczecin or Stettin.

Some small Jewish communities such as Zabrze, were soon reinforced by the mass arrival of Polish residents who had spent the war years in the Soviet Union, According to historian Yehuda Bauer, nearly 250,000 Polish Jews survived the war in the Soviet Union. The bulk of them, 177,000, returned between 1945 and the middle of 1946[1]. Some Polish Jews would continue to arrive in Poland for a number of years.

These repatriated Jews and Poles were Polish citizens who had fled their homes before the advancing German armies in 1939. The Polish government had urged all Poles, civilians and soldiers, to head to Eastern Poland or the area known as Kresy where a defensive line would be established to halt the German advance. Thousands of Polish soldiers and civilians headed to the East of Poland. Of course, these people did not know that the Germans and Soviets had signed a secret pact known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement whereby Poland would be divided between Germany and the Soviet Union. Germany was already in Poland and now the Soviet Union attacked Poland on September 17, 1939, and claimed its share of the spoils. The entire area that Russia took by force was immediately annexed to the Soviet Union. All native residents of the area were automatically converted to Soviet citizenship. All Polish refugees as well as Polish prisoners of war soldiers, were urged to apply for Soviet citizenship. Russia had taken about 230,000 Polish prisoners of war. Most of them refused to surrender their Polish citizenship. People began to disappear, rumors circulated, large security forces were everywhere and fear seized the inhabitants, especially those people who had recently

|

|

| German and Soviet officers shaking hands following the Polish invasion in 1939 |

|

|

| Polish prisoners of war captured by the Red Army during the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939 |

arrived in the area from German-occupied parts of Poland. The Soviet administration tried to force the Polish refugees to change their nationality but had little success.

Then on June 29, 1940, practically all Polish citizens who refused to accept Soviet citizenship were rounded up and escorted to waiting trains and dispersed throughout the Soviet Union, especially Siberia. The National Polish Institute of Remembrance states that about 350.000 Poles were deported to Russia, mainly Siberia and 150,000 of them died there. These numbers did not include the round ups that occurred prior to the massive deportations, which involved the removal of influential elements of society, namely political, intellectual, academic, religious, financial elements and elements hostile to the Soviet Union. There were many Jews among these deportees but the scale was rather limited. The main deportations were massive in the extent of people involved and the limited duration of the entire action.

Here is what Awraham Lang, a native of Krosno who escaped the German-occupied city and lived in Lesko, had to say: “I was awakened in the middle of the night and given two hours to pack lightly and was then escorted to the awaiting train by Russian security forces. I was shown into a railroad car with other Polish refuges and the doors were locked. The train soon started to roll. The trip was never ending and took weeks. From the final railway station we still had to walk to get to the special camp, which consisted of wooden barracks. The camp had no name but a number and it was in the area of Novosibirsk. The forest was everywhere but there were no chairs or tables or furniture in the barracks”.

“The men and single women were organized into labor battalions and marched to the forest to cut trees and reduce them to logs. These logs were then piled on top of each other and formed sizable triangles of logs. In the spring, the poles that held the triangles in place were removed and the logs rolled down the banks to the river. They floated downstream to a sawmill that converted them to wood products. Some of the branches were chopped into pieces for heating. Mothers, children and old people remained in the camp that was guarded. As a matter of fact, everything was guarded as though someone was going to run away from the forsaken place. Conditions in the camp were terrible; lack of food, lack of medicine and harsh weather caused many people to die. Still the

|

|

| Awraham Lang erecting a tombstone for his father Chaim Lang in Dzhambul, Kazakhstan in 1943 |

camp organized itself and began to function. Most of the camp officials were former political prisoners who were already free but were forbidden to leave the area. They lived in small poor and desolate villages. They were completely isolated from contact with the Soviet Union except for the official government messengers that the regional offices sent. These inhabitants and the poor captive prisoners were constantly watched and observed by the secret police that was everywhere and instilled fear in everybody, even in these remote areas. I soon learned that there were even harsher camps to which one could be sent if the local authorities took a dislike to someone and a number of people disappeared. The local people used to say: we too hoped that this will be over soon but look at us now, you too will get used to this way of life. Indeed they were hopeless.

“I became a lumberjack and so did the entire working population of the camp. The production was very limited since most of us were city people, hungry, resentful and lacked the basic tools and skills for the job. The work progressed but at a slow pace. I was always looking for food or for clothing as were the other inmates”. A black market developed in the camp with the approval of the police. The camp was transformed into a trading post that seemed to engulf the entire country. This situation was aggravated with the news that Germany had attacked Russia.

|

|

| Władysław Anders and Wladyslaw Sikorski with Joseph Stalin in Russia in 1941 |

Now everything was in short supply and there was a reason: the war. Everything was needed for the army. Still the German armies advanced rapidly through Russia until the gates of Moscow where they met the Russian's excellent defense system and a very harsh winter. The exhausted Germans came to a standstill. The Soviet government abandoned all slogans and reverted to the national Russian slogan “defend mother Russia.” Even in the distant camps of Siberia, films were shown describing the brutality of the German behavior towards the civilian Russian population. Newspapers like Pravda began to appear in the camp. I understood the spoken Russian language since it is similar in pronunciation to Polish but the written Russian language was a mystery to most of us since none of us were familiar with the Cyrillic alphabet.

The government tried to enlist the entire population in the war effort, even the so-called Polish enemies of the state. The general feeling eased a bit and people began to make an effort to help the country in the war effort. The Polish citizens in the camp suddenly became partners in the struggle against Germany following the agreement between the Soviet government and Wladyslaw Sikorski, the head of the Polish government in exile in London. Sikorski flew to the Soviet Union and signed the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement on August 17, 1941. The agreement called for the release of all Polish citizens from the prisons camps and “gulags”, the formation of a Polish army and the creation of an official Polish administration in the Soviet Union to care for all Polish citizens.

As a good will gesture, the Polish citizens were offered the opportunity to leave the camps for other parts of the Soviet Union where the climate was milder such as Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan. The response was so overwhelming that the government had to organize transports by allocating each camp to a particular city. My camp was assigned the city of Dzhambul in Kazakhstan. The camp was soon filled with Volga Germans, that is to say, people of German origins who had been living in Russia for generations and were distrusted by Stalin. So they were scooped up and sent to these camps that were just deprived of their Polish contingents. I left Siberia with other Polish refugees, mostly Jews, and headed for Dzhambul. Our train rolled and rolled days and nights, nights and days. Stops were frequent since military trains had priority. Each stop became an instant market; people were selling or trading goods for food. This scene would repeat itself throughout the journey. The days were getting warmer and longer and we soon arrived in this huge oriental city. Here the local administration, the Soviet authorities, the Polish Red Cross, and the Polish office of refugees assisted us. Soon other transports began to arrive from the same and different camps. The city's population underwent a radical change in composition. Polish refugees, mostly Jews, were present in large numbers and so were Soviet refugees that were evacuated by the Soviet government before the advancing German armies. Various epidemics started and many people died, especially Polish refugees, due to lack of food, medical facilities and drugs. The food situation was desperate and everybody was hungry. The Polish government later erected a massive monument honoring the Polish citizens who died in the Soviet Union during the war.

|

|

| Monument to the Fallen and Murdered in the East, in Warsaw Pomnik Poległym i Pomordowanym na Wschodzie |

Soon, help was on the way, American food began to arrive in large amounts as well as packages from relatives in the USA. The American Joint organization managed to obtain lists of names of Polish refugees in the Soviet Union and began to send them food packages. The Joint organized a supply center in Iran that would send relief packages to the Soviet Union. I received some of these packages and they saved my life and kept me going. I sold some of the products such as cigarettes on the black market and bought bread. Then I heard the first good news. The Polish army under the command of General Wladyslaw Anders was permitted to leave the Soviet Union for Iran. The army consisted of 88,000 soldiers and thousands of Polish civilians and orphans. There were very few Jews among the exodus. The Polish military authorities rejected many Jews who volunteered to fight the Germans.

“As the Soviet armies began to drive the Germans out of the Soviet Union, the food situation began to improve. So did the hope that the war would soon end and the refugees would be sent home. Nobody had any illusions about conditions back home but still nobody wanted to believe the rumors that were rife that large parts of Polish Jewry were destroyed. Everybody was certain that these rumors exaggerated the situation.

The Soviet armies pushed the Germans out of the Soviet Union and the Soviet refugees began to return to their homes. The Polish offices in the Soviet Union began to prepare lists to transport the Polish refuges back home. Slowly the Soviet armies liberated Poland and the first transports began to roll to Poland. The Polish government directed these transports to the new areas that Poland acquired since it wanted to settle the areas with Poles. It also wanted to direct the transports that contained many Jews to the new areas in order to avoid confrontations between Jews and non-Jews. I was soon contacted and given orders to prepare to head home to Poland. The transport left Dzhambul and headed to Poland. It was directed to Walbrzych. Along the road in Poland, many Poles left the transport and went home, but I and most of the Jewish passengers decided to follow to our destination since we already heard of unpleasant events that happened to Jews returning to Poland. The transport arrived and I was immediately assigned a flat from which the previous Germans occupants were simply expelled, escorted to trains and forced to board them. These transports headed to Germany.

It is estimated that 3.3 million Jews lived in Poland in September 1939. When the war ended in May 1945, only 42,662 Jews remained in Poland. Soon, starving survivors from the labor camps and concentrations camps returned home and increased the number of Jews to 80,000. By January 1946 the numbers increased to 106,492 with the discharge of Jewish soldiers from the Polish and Soviet armies. Many Polish citizens in the Soviet Union had been drafted into the Soviet armies. With the massive arrival of repatriated Polish Jews from the Soviet Union, the number of Polish Jews swelled to 240,489, still a small fraction in comparison with the prewar Polish Jewish population. Most of the Jewish population now lived in the new Polish areas. The Jewish population shifted from the eastern and central areas of Poland to those in the west. The new Jewish communities like Zabrze benefited by the shift of Jewish population.

|

Below is a loose translation of the document.

The document dated March 1946 in Zabrze, Slansk region and directed to the Central Committee of Polish Jews at 5 Szeroka Street, Warszawa-Praga, Statistical division.

We are complying with your requests and answering your questions to the best of our ability.

- List of institutions, their leaders and titles;

- Jewish Committee in Zabrze, Jakub Wieselberg, president

- Old age home, dr. Necha Geller, chairman

- The Orphanage, dr. Necha Geller, chairman

- The home for youngsters, Zofia Kacowa, chairman

- Religious slaughterer, Jakub Wieselberg, chairman

- Number of people registered with the committee – 432

- Children to the age of 14 years – 58

- Jews that returned from the Soviet Union – 326

- Number of Jews that are helped by the committee of Zabrze – 432

- The city is basically a military city

- The city is surrounded by mines and melting factories

- The Jewish population needs more cultural activities.

- The city needs a Jewish school

The above document also had an attachment that listed all the Jews that registered with the Zabzre Jewish Committee. The extensive list is attached at the end of the book. According to the list of Zabrze residents four Jews of Zabrze who survived the Shoah and were residents in Zabrze in 1946. Their names were[2];

Sarita Nizinska born 1926 in ZabrzeWilli Ofner born in 1906 in Zabrze

Arthur Orenstein born 1887 in Zabrze

Hilda Offenberg born 1888 in Zabrze

Of course, there were also some “mischling” or descendants of mixed parentage, namely Jews who married Christians and vice-versa, that were not added to the list. It is also possible that some Jews in Zabrze still lived under assumed names and refused to be identified as Jews. A list of all registered Jewish residents of Zabrze can be found at the end of this book.

The needs of the Shoah survivors and the repatriated Jews from the Soviet Union were immense. The Zabrze Committee like similar other committees submitted their requests to the Central Committee of Polish Jews in Warsaw that in turn assembled all the requests and submitted them to the Polish government. The Central Committee of Polish Jews, also referred to as the Central Committee of Jews in Poland and abbreviated CKZP, (Polish: Centralny Komitet Zydów w Polsce, Yiddish: צענטראל קאמיטעט פון די יידן אין פוילן was a state-sponsored political representation of Jews in Poland at the end of World War II. The creation of the Committee was approved on November 12, 1944, by the Provisional Polish Government. The Zionist Emil Sommerstein was appointed head of the Central Jewish Committee of Polish Jews.

|

|

| Emil Sommerstein |

Emil Sommerstein, born in the village of Chleszczewa near Lwow, was an attorney but devoted himself to Zionism and politics. A Zionist leader, Sommerstein was elected to the Polish senate in 1922-1927 and again in 1929-1934. He was also a member of several important commissions. In 1939 Sommerstein was arrested by the Soviet authorities and sent from gulag to gulag on various charges. But, because the Soviets wanted to legitimize their puppet Polish government to usurp any power from the Polish Government in Exile in London, they decided to rehabilitate former well-known Polish political figures like Sommerstein.

In 1944, the Soviets first flew Sommerstein, sick and a shadow of himself, to Moscow, where he was appointed a member of the Polish government. Sommerstein was appointed to the cabinet and urged to organize the Committee for Polish Jews. He hoped to reestablish the Jewish community in Poland. But Sommerstein was also a Zionist, a leader of the Ichud Zionist party or the Democratic Zionist center party. He believed that those Jews who wanted to leave for Palestine should be able to do so. But, he was certain that many Polish Jews would remain in Poland and would need all the help they could get from the Polish government. Sommerstein also published the Yiddish newspaper entitled “Dos Naje Leben” or The New Life.

As a Zionist leader, Sommerstein participated at a meeting of Zionist leaders in London in 1945. He described the conditions of the Jews in postwar Poland and appealed for help to revive the Jewish community.

|

|

Top row, left to right : Abba Hillel Silver, MosheKleinbaum–Sneh, Yitshak Grunbaum Middle row, left to right: unidentified, Moshe Sharett, Nahum Goldman Bottom row, left to right: Yitzak Zuckerman, Haykah Grossman, Emil Sommerstein with beard, Leib Salpeter, and Meler |

The Central Committee of Polish Jews consisted of six members of the Communist Party that called itself the Polish Workers' Party, four Bund representatives, four representatives of Ihud Zionist, three representatives of Poale Zion Left (leftist faction of Workers of Zion), three representatives of Poale Zion Right and one representative of Hashomer Hatzair. There were no religious representatives or right wing representatives. The presiding officer was Emil Sommerstein. The communist influence within the committee was obvious but Sommerstein wanted to get all the aid of the government for the needy Jewish survivors. The Polish government dealt only with this committee which had several district offices throughout liberated Poland, and all Jewish community requests were directed to it before being considered by the government. The Polish government granted most of the requests but it must be remembered that Poland was a devastated country after the war and its resources were limited.

Sommerstein also wanted to revive Jewish religious life in Poland. The Central Committee was not keen on the idea but the Polish government or rather the Soviet government liked the idea. The Russians were willing to do anything to score international political points in the fight against the London based government. Sommerstein obtained approval to bring Rabbi David Kahane to Lublin. He was one of the few rabbis in Poland to survive the Holocaust and later became Chief Rabbi of the Israeli Air Force and then Chief Rabbi of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

David Kahane was born March 15, 1903 in the village of Grzimalow in the Tarnopol region, Eastern Galicia. He was ordained as a Rabbi in 1929 in Vienna where he also received his Ph.D. After his studies, Kahane settled in Lwow (Lemberg), Poland, and became the Rabbi of the Sistoska synagogue. He held that position until the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939. In his memoir “Lwow Ghetto Diary,” Rabbi Kahane describes how he survived the war by playing cat and mouse with the Nazi troops searching the city for Jews, including being shot at when one of his hiding places was uncovered. Nevertheless, Kahane was soon captured and moved with the other Jews of Lwow to the Jewish ghetto built by the Nazis. Eventually he was deported

|

|

| Rabbi Doctor Major David Kahane, chief Jewish chaplain of the Polish army |

from the ghetto and wound up in the Janowska labor camp outside the city of Lwow. Janowska was also a transit camp. From there Jews unfit to work were sent to the death camp of Belzec. According to Rabbi Kahane, conditions in the camp were so horrible they defied description. The rabbi escaped the Janowska camp and begged for refuge in the palace of Lwow's Ukrainian Metropolitan Archbishop Andreas Sheptytsky. During the war Sheptytsky harbored hundreds of Jews in his residence and in Greek Catholic monasteries. He also issued the now famous pastoral letter, “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” to protest Nazi atrocities. Rabbi Kahane arranged with the Archbishop to place his own daughter in a convent. She survived the Holocaust as did Kahane's wife, who was admitted to a Uniate institution under orders of Sheptytsky. Archbishop Sheptytsky also issued orders to the Uniate convents of the Studite order in Eastern Galicia to accept Jewish children and hide them. The Archbishop died in 1944 and is buried in St. George's Cathedral in Lwow.

Rabbi Kahane's experience led him to a deep understanding of the complexities the Jewish community faced following the war. Having survived with his family due to the good offices of the Christian community, he respected any Christian family or institution that harbored Jews during the Nazi terrorist rule.

With the liberation, Lwow became Soviet territory. Rabbi Kahane began the uphill battle of reviving the decimated Jewish community of the city. One day Kahane was surprised to receive an invitation to come to Lublin where the Polish government had established

|

|

| Rabbi Doctor Major David Kahane (in his military uniform) with family |

its administration. He met Sommerstein and together they met the Polish Minister of Defense, General Rola-Zymiersky, who offered Rabbi Kahane the job of Chief Rabbi of the Polish Army with the rank of major. The Rabbi graciously accepted the post but only after requesting, and receiving permission to open a bureau to restore the destroyed Jewish religious communities throughout liberated Poland.

Sommerstein and Kahane were familiar with Soviet political tactics and knew full well that they were being used for propaganda purposes. They decided to use the opportunity to obtain as many benefits as possible for the Jewish survivors who needed all the help they could get.

Rabbi Kahane immediately began to tend to the needs of the 15,000 Jewish Polish soldiers. He also began to help restore Jewish religious communities in liberated Poland. The job was immense so he enlisted the help of a military chaplain named Aaron Becker. Kahane also tried to enlist the services of Private Yeshayahu Drucker. Drucker was active within the Polish army on behalf of Jewish spiritual matters, organizing a “seder meal for Jewish soldiers.” Kahane saw in Drucker a man who could help him restore Jewish religious life in Poland.

|

|

| Captain Yeshayahu Drucker |

Yeshayahu Drucker was born in 1914 to Israel and Rachel Drucker. The family lived in Jordanow, a small town near the large Galician town of Krakow where the father was a watchmaker and was very active in the religious Zionist movement “Mizrahi.” Young Drucker studied in various heders, traditional Hebrew schools, and then entered the Hebrew high school. On completing high school, he enrolled at the well-known teacher seminary “Poznansky” in Warsaw. He graduated from the institution with a teaching certificate in Jewish studies in 1939.

With the German advance in Poland, Drucker fled east. Arrested by the Soviets, he and his brother Aaron were sent to a gulag or labor camp in Siberia. Following the Polish-Soviet agreement in 1941, the brothers decided to join the Polish Army in the Soviet Union headed by General Wladyslaw Anders. Both were rejected as being Jewish. They tried to join later and were accepted in the new Polish Army headed by General Zygmunt Berling.

Both brothers fought their way to Germany. Both helped Jews along the way, especially Yeshayahu who petitioned the Polish Army command to provide the Jewish soldiers with the same spiritual assistance that was granted to Polish Catholic soldiers.

Yeshayahu's army unit was chosen to parade in Berlin following the defeat of Germany. Yeshayahu was then posted to the Polish city of Siedlice. This is where Rabbi Kahane met him and signed him up as a religious officer with the rank of captain in the Polish Army. Drucker was given the job of restoring Jewish religious communal life in Poland. He immersed himself in his work together with Rabbi Aaron Becker. Both rabbis visited newly established Jewish communities in liberated Poland and helped organize Jewish religious life. Everywhere, they tried to organize a local Jewish religious association that would provide the basic religious needs of the local Jews. All religious items such as prayer books or prayer shawls were in great demand. Drucker and Becker took the demands back to Warsaw and presented them to Rabbi Kahane. Kahane began to write letters of appeal for help to the various Jewish communities in Palestine, Britain and the United States. The response was overwhelming. Religious materials and money began to flow to the offices of Rabbi Kahane. He distributed the items to the various Jewish communities.

Drucker took some religious materials to the Jewish community of Zabrze, where he saw the Jewish compound with several buildings standing empty. He reported his findings to Rabbi Kahane who was looking for a Jewish home for orphans where rescued children would get a general and Jewish education, something that the Central Committee orphanages did not provide. With the liberation of Lublin in 1944, the Central Committee of Polish Jews established a Jewish children's home to cope with the young Jewish survivors. Other Jewish homes were soon established in Otwock near Warsaw, in Helenowek near Lodz, in Krakow, in Zakopane under the leadership of Lena Kichler, and other places. Usually it was Jewish individuals who had survived the war who established these homes, but eventually most of them came under the control of the Central Committee of Polish Jews or the local branch of the organization. Being an official institution of the Polish government, the Committee received building facilities, supplies and some financial assistance. At the end of 1945 there were already 11 Jewish foster homes. The homes were maintained by the Education Department of the Central Committee headed by Shlomo Herszenhorn, a Bund leader. These homes taught curriculum established by the Committee that followed newly created Polish educational curriculum. The emphasis was on Polish culture and language with a smattering of Yiddish culture and the Yiddish language. Rabbi Kahane and Captain Yeshayahu Drucker did not approve of the curriculum.

|

|

| Letter sent by Yaacov Herzog to Captain Drucker, dated December 29, 1946. “Enclosed is a list of Jewish children who survived the war hidden by non–Jewish families in Poland. Their families in Israel asked us to help them recover the children or at least to place them in Jewish institutions in Poland. We would appreciate if you could follow all these cases. Please let us know of the results. Please keep up written contact. Yours, with blessings from the Torah and the land of Israel.” (Freely translated by William Leibner) |

|

|

| Yaacov Herzog was Rabbi ItzhakHerzog's son and secretary |

Members of the Association of Religious Jewish Communities (ARJC) in Poland began reporting to the main office that Jewish children remained hidden with Christian families and asked for help to restore these children to their Jewish families. Meanwhile letters, pleas and appeals were being sent steadily to Rabbi Itzhak Halevy Herzog, chief rabbi of Mandate Palestine, to help locate Jewish children who had survived the war hidden with Christian families or institutions in Poland. Many of the saviors refused for one reason or another to restore the children to their Jewish families. Children who no longer had living relatives in Poland or no surviving family at all, presented special difficulties. Legally, no action could be instituted for the return of these children. Families who had fled Poland and were now living abroad were pleading for Rabbi Herzog to help.

|

|

| Rabbi Itzhak Halevi Herzog, chief rabbi of Mandate Palestine and later chief rabbi of the state of Israel |

Rabbi Herzog saw but one way to help all these Jewish families: the children must be redeemed in accordance with the old Jewish tradition of “Pidyon Shvuyim” or redemption of the Jewish prisoners by paying ransom. Herzog and Kahane now decided to apply this ancient tradition in Poland to restore the Jewish children to their families and community. They knew that large sums of money would have to be raised to implement the program.

Rabbi Kahane had the right man to implement the task: Captain Yeshayahu Drucker who spoke Polish fluently and had a Polish appearance. Drucker soon began to receive letters and lists of children that were supposedly hidden in Poland during the war years. Above is a letter addressed by Rabbi Herzog's son Yaakov to Drucker. Rabbi Kahane and Captain Drucker decided to open an orphanage for the rescued Jewish children. The Polish army actually had a tradition of caring for orphanages as General Anders removed his troops from the Soviet Union. Several Polish orphanages had followed the Polish army. So Kahane used all his connections within the Polish Army and received permission to open the Zabrze orphanage. All the permits were obtained in the name of the AJRC of Zabrze. The main building would be the orphanage except for the top floor, which was reserved for an old age home. The orphanage would also use the elementary school building that had been closed for many years.

|

|

| The Zabrze Jewish orphanage, previously an old age home |

There was one other building in the compound that was given to the Ichud Zionist organization where their kibbutzim or collective youth groups would train prior to leaving for Palestine. These groups were Zionist pioneers and were determined to head to Palestine. The kibbutzim were organized along political Zionist line and consisted of members of Maccabi Ha-tsa'ir and Gordonia. Gordonia was founded in Poland in 1925 had been very active prior to World War II and started up its activities immediately in liberated Poland after the war.

|

|

The kibbutz was made up of Holocaust survivors belonging to the Zionist youth movements Gordonia and Maccabi Ha –Tsa'ir In the photo: Ichezkel Flekier ( Yechezkel Fleker) – (middle row, fourth from the left)and his wife Elka, nee Popok (to the right of Ichezkel) Photographed on October 1, 1946 |

The first group soon left Poland and headed to Germany to a D.P. CAMP. The group would continue to move until it reached the shores of Italy or France and head illegally to Palestine. Another kibbutz would then take its place.

The Jewish community of Zabrze helped these institutions since they contributed greatly to the growth of Jewish life in the city.

|

|

Seated from left to right: Dawid Hubel, headmaster; Dr. Nechema Geller, administrator of the Zabrze orphanage; Captain and later Major Yeshayahu Drucker dressed in his military officer uniform Standing left to right: 1 Unknown; 2 Unknown; 3 Randolf Wittenberg, gym teacher and security officer; Mrs. Olnicka; Mrs, Englard, a teacher |

|

|

| The school building of the Zabrze home |

|

|

| Dr. Nechema Geller, administrator of the Zabrze orphanage |

Rabbi Kahane speedily proceeded to assemble a staff for the orphanage. He appointed Dr. Nechema Geller, a Shoah survivor, as headmistress of the orphanage and school. Her husband was also involved in the Jewish community of Zabrze and nearby Katowice

|

|

| David Hubel was the headmaster of the orphanage and the father figure. He survived the Shoah and was the official Hebrew teacher at the orphanage |

|

|

| Rudolf Wattenberg, gym teacher and security officer. With existing conditions in Poland, security was needed especially around Jewish institutions |

|

|

Seated from left to right: Mrs. Schapiro; Dr. Nechema Geller and her husband Dr. Geller, active in the Jewish community of Katowice; Mr. Gotlieb, secretary of Nechema Geller; dentist of the Zabrze home Standing from left to right: Unknown; Mr.Gotzed; Unkown; David Hubel; Unknown; Unknown |

With the staff completed, the orphanage of Zabrze was ready to receive the first Jewish orphans in post war Poland. Rabbi Kahane wrote to the JDC in Poland to help run the orphanage. The plea was received by David Guzik, director of the Joint Distribution Committee's operations in Poland.

David Guzik was born in Warsaw, Poland. He joined the JDC Warsaw office as an accountant in 1918. During the course of World War II, he became a central figure in JDC Warsaw. Using his skills to raise funds by legal or illegal means, he helped finance welfare services, medical help, and cultural and underground activities in the ghetto including the Oneg Shabbat project and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. He survived the war in hiding on the “Aryan” side. In 1945, he was appointed Director of JDC Operations in liberated Poland. David Guzik was killed in a plane crash in Prague in 1946 while returning from a conference in Paris, France. He had gone to Paris for consultations and met Dr. Joseph Schwartz, head of JDC operations in Europe.

|

|

| David Guzik |

Dr. Joseph Schwartz was a brilliant and exceptional man. Known as Packy to those close to him, he was born in Ukraine and moved to Baltimore at an early age. A distinguished educator and scholar and an authority on Semitics and Semitic Literature, Dr. Schwartz received his doctorate from Yale, following his graduation from the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Seminary of Yeshiva University. Dr. Schwartz taught at the American University in Cairo and at Long Island University and then served as Director of the Federation of Jewish Charities in Brooklyn. He served the JDC from 1939-1950/1, and then went on to become the Executive Vice Chairman of the United Jewish Appeal and later the Vice President of Israel Bonds. He passed away in 1975, leaving behind a legacy of countless good deeds.

Following World War II, Dr. Schwartz organized a massive organization that helped thousands of Shoah survivors and enabled them to regain their human composure. The Joint Distribution Committee not only provided food, medicine and financial help but also provided hope. Schwartz was especially concerned with the Jewish infants who had survived the war. Orphanages and Jewish youth centers were on top of his list. He of course endorsed the support for the Zabrze orphanage. With aid from JDC the Zabrze orphanage began to provide a loving home for rescued Jewish children.

|

|

| Dr. Joseph Schwartz in his military uniform |

| Institution | Address | Number of children |

| TOZ, Jewish Health Assoc. | Otwock, Olin | 40 Sanatorium |

| Glussyoe | 80 Preventorium | |

| Srodborow Cleszynska | 70 | |

| Religious Organizations | Krakow Dreitele | 29 |

| Agudas Israel | Dzierszew | 50 |

| Lodz | 10 | |

| Children Home | Dzierzoniow, Browarna 12 | 30 |

| Lodz, Zachodnia 66 | 10 | |

| Religious Congregation | Zabrze, Karlowicza 10 | 31 |

| Vaad Hatzala | Bytom, Smolenska 15 | 70 |

| Zionist Organizations | Headquarters, Lodz | |

| Poludniowa | 26 | |

| Mizrachi | Krakow, Miodova 26 | 25 |

| Mizrachi | Sosnowiec | 39 |

| Coordination of Zionist | Lodz, Zawadzka 17 | 93 |

| Hashomer Hazair | Srodmiejska 4 | 49 |

| Poale Zion | Bielawa | 52 |

| Central Jewish home | Committee Legnica, Piastowska 6 | 60 |

| Central Jewish home | Piotrolesie, Ogrodowa 10 | 88 |

| Central Jewish home | Chorsow, Katowicka 2 | 80 |

| Central Jewish home | Otwock, Bolesl. Pruss 11 | 80 |

| Central Jewish home | Srodborow, Cieszynska | 75 |

| Central Jewish home | Bielsko, Mickiewicza 22 | 56 |

| Central Jewish home | Srodborow, Literacka | 2 |

| Central Jewish home | Srodborowianka” | 104 |

| Central Jewish home | Helenowek | 117 |

| Central Jewish home | Krakow, Augustyuska Boczna 8 | 66 |

| Central Jewish home | Czestochowa, Jasnogorska | 32 |

This is a translation of the original Hebrew list of Jewish homes into English. The first column on the left gives the name of the organization of the home. The word central indicates that the home was under the control of the Central Committee of Polish Jews. The second column gives the address of the home and the last column indicates the number of children at the time of the visit of the inspectors of the Joint Distribution Committee. The number of children in the central homes remained relatively steady while the Zionist or Agudah homes constantly shipped children out of Poland.

|

|

| Original partial list of the orphanages that the Joint Distribution Committee supported in Poland |

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zabrze, Poland

Zabrze, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Oct 2016 by LA