|

|

[Page 39]

The Slaughter March

The Provincial Jews Action

It seems to me that there was never even one quiet day in our ghetto-life. If there were no direct “actions,” or Aktionen as they were called in German or Yiddish-that is, organized mass murders-there were rumors circulating, and indications that another action was about to start at any moment, that they were already digging new pits, that very soon they would again start taking. Our nerves were irritated and strained. We had no rest, not in the daytime and not at night. We lived in constant fright, in constant deadly fear.

The first mass slaughter in the Dvinsk ghetto, which took place at the beginning of August, 1941, before we arrived, was called the provincial Jews action, because those who died in it were mostly Jews from the surrounding towns, the province. If anyone was still, at that time, not well versed in the ways of mass slaughter, that action showed them what masquerades and deceptions the ingenious Germans used to carry out their tasks. Such methods were required, in order to entice and confuse the victims.

In the first days, when there simply wasn't enough room to squeeze all of the unfortunate Jews into the Dvinsk ghetto, rumors began to spread that a brand new, more comfortable ghetto had just opened up a few kilometers away. All those who wanted to could move there, it was said, but the provincial Jews were invited first. These Jews, who were mostly craftspeople, laborers, and other strong, hardworking common people, were delighted at the opportunity, and they, together with a small number of Dvinsk Jews, loaded their baggage onto their backs and allowed themselves to be led away. The well-known Dr.Gurevitch of Dvinsk, an idealist and an influential community activist, willingly undertook to be the leader of the group, and to give medical aid when needed.

On wings of hope, and without any suspicion, those people, as families, old and young, set out on their way. They were led by a couple of Germans and a few Latvian police. The sun was burning stronger and stronger, and the Jews walked, tired and burdened, bent under their packs of belongings.

They went a few kilometers from Dvinsk, they drew near to a small forest, a valley-and suddenly hundreds of uniformed Germans and Latvians with weapons sprung forth from the woods. There was shooting from all sides. Machine guns spattered, and grenades exploded. The confused Jews were surrounded and driven to the prepared pits. It didn't take long for the entire group, almost without exception, both dead and half-dead, to be shoved in.

The well-thought-out plan succeeded. The Jews, deceived and confused, did not grasp at first what was going on. They could not put up a defense,

[Page 40]

and were liquidated in the quickest way possible. The belongings that they brought with them, and the clothes that they were wearing, served as a handsome reward for the rapidly executed work. Hundreds of Latvian families were enriched the very next morning with the bloody Jewish wealth.

So far as anyone knows, there was only one single Jew, Dr. Gurevitch, who remained alive. An eizsarg acquaintance of his whom he had once helped hid him and rescued him from death, for a very large sum of money.

Thereafter, various legends about Dr. Gurevitch circulated in the Dvinsk ghetto. I later met him in the Riga ghetto, and he related to me, with all the details, everything about the provincial Jews slaughter. He said that the Germans and Latvians threw the Jews into the pits half-dead, and that the earth that was poured over them literally shifted and heaved, mixed throughout with blood and human limbs. The toll of the dead, it appeared, reached more than a couple of thousand.

“Such a violent slaughter!” Dr. Gurevitch said. “Such an outrageous, deceitful murder of innocent people, of mothers with children! Who could have believed, who could have imagined that people, civilized people, were capable of such things? And I watched it all, heard the screams and groans of the unfortunate, and saw how others fought like lions, protecting their wives and children. If we had had, at the time, the smallest suspicion of what was being prepared for us, they would not have wiped out the provincial Jews so easily. I myself saw, after all, how dozens of the deceived Jews, even those already wounded and soaked with blood, threw themselves at the murderers with bare hands and with stones and fought till they drew their last breath. Those were powerful, heroic Jews. They wounded more than a couple of dozen of the killers, and a few of them they choked to death and dragged with them into the pit. However, in the end the Jews were all killed. And what could I do for them then? And what can I do now?” That's how Dr. Gurevitch told the story, and wept in his grief and helplessness.

Dr. Gurevitch saved himself once, but on the 28th of July, 1944, when the great slaughter took place in Schtrasdenhof-near Riga, where he was last imprisoned-he did away with himself by consuming poison. So ended the life of a great Jewish idealist from Dvinsk, Dr. Gurevitch.

[Page 41]

The Selection-Who Shall Live, Who Shall Die

After the provincial Jews action, such mass slaughters occurred in the Dvinsk ghetto with the speed and systematic efficiency that the plan to exterminate the Jews required. The second action took place on the 8th of August. On that occasion, mostly older people, children, and those who didn't have “good” work tags were killed.

This time my family and I experienced the process of taking in all of its horror. From early morning on, the ghetto was hermetically closed and locked, surrounded by units of Latvian police. With beatings and shootings, they drove

[Page 42]

everyone out of their living spaces, and threw the sick out of the hospital. They dragged out those who had hidden in corners and in the outhouse pits. A few such people were killed on the spot. Then men, women, and children, old and young, stood in long rows in the courtyard, all day, waiting for the arrival of the high German command, and for the selection.

Finally there came, from town, a group of Germans in military uniforms. They were the higher-ranking men of the Gestapo and S. S. They walked along sedately and conducted a quiet conversation among themselves. In that sedate, systematic, matter-of-fact manner they began the bloody selection process, as though they were sorting not human beings but cattle, horses, or dead, soulless objects.

“Do you have a work permit? Show it. Go to the right.”They speak quietly, in calculated and measured words. They give restrained, polite orders. They look through the mass of people like experienced professionals who don't want to exert themselves too much. But the Latvian policemen beat the heads of the Jews with wire and rubber sticks, and see to it that the polite and quiet orders are carried out exactly.“You don't have a permit? Go to the left.” “Oh, you are too old to work? Go to the left.” “Your work permit is no good? Go to the left.”

“Whose children are these?You are lying; they are not yours. Go to the left. Go left!”

“Ah, you little old mother. Go there-there! Over there, left.”

Our row comes up. They look through us with sharp, inhuman glances. The heart stops, hardening into a painful, leaden lump. There is not enough breath. So, is this the end? With one blink of the eye, condemned, sent to death? The children, wife, myself, all of us? No, this time we are among the fortunate ones. My work permit is valid. They tell us to go to the right.

Night falls. It's pouring rain. We are soaked from head to foot, exhausted, dead tired. The children fall down, fatigued, and fall asleep on the wet stones. But they don't allow us to go away just yet. We must wait.

We can no longer see the human mass that was set apart, but we hear, quite nearby, coarse shouted commands and-a cry, a shout, and a wailing to high heaven. Here and there a shot is greeted with a frightened death-shout. The victims are driven uphill, and for a long time we can still hear the shouting and shooting. Then the mass of victims starts downhill, and everything is swallowed up in the darkness of the night.

This is not the place, and I am not the person, to analyze the tangle of feelings and thoughts that we endured at such moments, or more accurately, through such long, long hours. I remember a mental and physical collapse, a consciousness of absolute helplessness, and at the same time a kind of hopea hope for some miracle that might save us. And over everything hovered the grim terror of pain and death, the fear of being torn away from those dear

[Page 43]

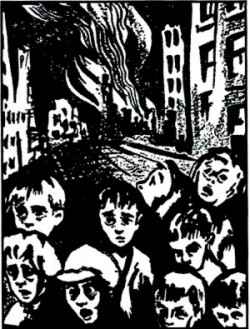

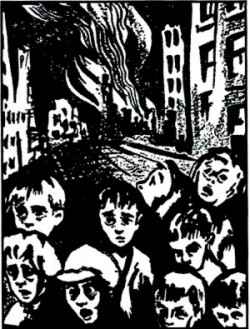

to us. With the wild shouting, and the beatings and shooting and spilling of blood, the deadly fright and confusion became overwhelming. Can anyone understand what it is like to be in that situation? I myself am unable to imagine it now. Perhaps the accompanying short poem, which I wrote at the time, can convey how people felt as they were being driven on their last journey.

Dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Dvinsk ghetto

| A person here, a person there... People are being selected. A shout of pain...a farewell tear... The multitudes are being driven to their death.

It is a human-no longer human: his spirit and power

The journey leads to a mass grave.

The journey to the end is short and long...

Is this then the end? In a grave, over there

At the hands of murderers, at the teeth of animals

You want to embrace your world |

[Page 44]

| You hold, you press your child to your breast, You want to protect it from the predator's hand. And the soul of the child, its joy in living, Goes out in a painful shiver.

The journey is short...the end is near...

It's the lastjourney...the last step...

(Written in the Dvinsk ghetto, 1942) |

Four or five kilometers from the ghetto, in the surrounding neighborhood of Pogulyanke, the prepared graves were waiting. There the victims were beaten to death, or tortured till half-dead, then forced to take off their shoes and clothes, to give up their “hidden valuables,” and to get down on their knees, facing the grave, at the very edge of it. From that position they could easily fall in, without any effort or help from the murderers.

All of those details, and the details of many other outrageously shameful deeds that one cannot, in humane and decent language, render on paper, were recounted by the Latvian eizsargs themselves, and by two young Jewish boys from Dvinsk-the only two who survived from that group of victims. The boys were slightly wounded, thrown into the grave, and covered with dirt, but at night they crept out. They hid themselves for a few days in the neighboring gardens and then came back to the ghetto.

Those two wounded youngsters who had fled the grave remained alive in the ghetto till the November slaughter. When that time came, there was no rescue for them, and no more life on this earth.

Cutting Down Grain, and People

It is the month of August. The summer skies have poured sunshine and rain, and the earth has bestowed upon the people a rich harvest. But at present the people are busy running a war, and there is a shortage of work hands to bring in the harvest.

Every day dozens of farmers come to the Latvian commandant of the ghetto and beg him to lend out Jews to bring in the grain from the fields. The farmers commit themselves in writing to return the Jews in the stipulated time, and the

[Page 45]

commandant releases a few hundred Jews for fieldwork. It doesn't cost him anything. The richer Jews of Dvinsk have brought him enough articles of gold for the favor of being released from the ghetto for a week.

Now luck is on my side. I remember my real calling: I am an agronomist, an educated farmer. I recall the fields and gardens with which I had a close relationship not so long ago. I make my way to the commandant, tell him my background and-a miracle. Without the least difficulty I am sent, with my family, for a week's time to do land management work.

My new boss packs us up on his wagon and drives away to his place in the village. I see again broad, fruitful fields, green forests, sunny skies, and a quiet environment of village farms. And it seems that respectable Latvians still exist. One of them is my boss, the good-hearted, honest, sympathetic Joseph Skrinda, with his friendly family members, from the village ofLiksna, fifteen kilometers from Dvinsk. Quiet work in the country, light and sunshine, a peaceful separate room, milk, butter, and meat-it is hard for us to believe that such a life is still possible on earth.

The week flies by like a sweet dream of the garden of Eden. Oh, how unwilling we are to journey back to the ghetto! Joseph Skrinda drives to the Dvinsk ghetto commandant, and with great difficulty works out a concession to allow us to remain for another week at his place.

But all things come to an end on the sinful earth, and on the 25th of August, after two weeks of living in this Garden of Eden, we were back in the Dvinsk ghetto. Oh God, what had taken place there in that short time! On the 17th and 18th of August, they again selected, and this time almost all the victims were those who had come back from work in the village farms. At times, the takers didn't even bother to drive up to the ghetto gate. They dragged fathers, mothers, and small children down off the wagons and threw them into large cargo trucks. They carried them, together with a thousand other victims, to the mass graves in Pogulyanke, from which there was no possibility of return.

Those unfortunate people had cut down grain only to be cut down like grain themselves. If that is a matter of luck, then luck was indeed on the side of me and my family. If we had been obliged to return from the village after the first week, we would, like all the others, have fallen into the exact moment of selection.

Pale, with large frightened eyes, the children of the ghetto would listen to the tales the grown-ups told about the Jews who had come back from the village farms-how the takers had thrown mothers and their children off the wagons, and had yelled at them, “Ha, you want to live in the village? Drink fresh milk? Get some rest? Come, come, you swine-dogs, we already have a resting place for you!” They threw the Jews into the trucks, the adults would continue, and there a lot of children suffocated, even before they were brought to the mass graves.

And the little children listening would take it all in. They would understand

[Page 46]

everything. A few weeks of ghetto-life had made them into grown-ups. They were adult children, loaded down with wisdom and experience. They would go back to playing again, and in their play they would build “molines” (hiding places, a German word widely used in the ghettoes and concentration camps) to hide themselves from the takers. Out of tin cans, sticks, and wire · they would make ingenious airplanes, weapons, and bombs with which to kill off Hitlers and Goebbelses. And with the greatest childish earnestness they would ask me, my two little children-eight-year-old Gideon and six-year-old Avremele (or Abraham)- “Pa, why don't we really do that? Kill them off, the pair of villains who give orders to shoot us? And then...we can go out of the ghetto and drive home.”

Poor innocent little Jewish children! There was no longer any home for you, nor any life, but it was better that you should not understand as fully as we grown-ups did.

Among the approximately four thousand Jews who vanished from the Dvinskghetto during the bloody days of August 1941, there was a close friend of mine-one of the brothers Zelikman, who were rich Jewish gardeners from the trans-Dvina territory. His boss brought him from his village to the ghetto gate, and there the angel of death was waiting for him.

Quiet Days in the Ghetto

The Dvinsk ghetto-life resumed its course, normal and dark, as it was meant to be, probably, in every ghetto of the twentieth century. Yes, after the actions the ghetto inhabitants got richer with bed linens, clothing, beds, tables, and other baggage. Also, conditions were less crowded. One could live a lot more comfortably. Yet soon the terror started again. Every day, every hour, brought new decrees, new torture, fright, and suffering, so that those who remained alive were constantly harassed, fighting for their own bodily existence, and could not grieve long and openly, could not lament the dead.

There was no one with whom you could talk your heart out, no one who could comfort you. The overturned life in the ghettos and concentration camps knew nothing of sensitivity, sympathy, or consolation. You had to swallow your sorrow and pain. You had to carry it deep within yourself, in the hiding places of the heart, and further, like a wordless beast, you had to go to your work, and even laugh and smile when you really wanted to weep and lament. These were the unwritten laws of ghetto-life, and that is how we were obliged to conduct ourselves.

And ghetto-life extended beyond the ghetto. Some hundreds of Jews had settled in Dvinsk itself, in a variety of military and police work units. They were mostly shoemakers, sewers, tailors, smiths, canners, carpenters, and other craftspeople, as well as ordinary Jews, men and women, who served the Germans. Those so-called city Jews considered themselves lucky, believing that a “steady job” in town provided an “assurance against death” for both

[Page 46]

them and their family members. That is what they thought, but unfortunately, in that they were bitterly deceived.

My own family was “protected” in this way. Since I was skilled in technical work, I was, after a short probationary period, made a machinist in the vulcanizing workshop that belonged to a military unit. The workplace was considered one of the best, and was known in Dvinsk by the name “tank job.” (It was last known to be in the former Jewish confectionery and chocolate factory of Kopilovsky, at the comer ofPostoyala and Ofitsirska streets.) After a ten-hour workday, I used to go “home”-that is, to the ghetto-together with a few of my Dvinsk friends, like Bobrov, Pressman, Yudelson, Goren, Weinstein, Katz, and Asinovsky. Later, I chose to settle in town, near the workplace, as did the remaining twenty to twenty-five of my comrades, but in the happy days when I still had someone to care for, I returned to the old Dvinsk crepost willingly. I would bring back bread, green vegetables, sometimes a little sugar, butter, and sausage.

The months of September and October were comparatively satisfying. They would often let people leave the ghetto and go into town almost without supervision. We only had to observe the rules strictly, wearing the yellow badges sewn on (not just loosely attached), walking in the middle of the street (not on the sidewalks), and refraining from all contact with non-Jews. If you didn't count the fact that a few Jews were shot or tortured in jail for not observing the aforementioned rules, those two months went by quietly.

But now November is coming on, and again the ghetto air is filled with a variety of rumors. Farmers tell us that mass graves are being dug again. Twice the ghetto is visited by German and Latvian officials of high rank. They examine everything and talk secretly among themselves. They call the head Jew, and say something or other to him, but we, the ordinary people, don't know what it is. We hear talk about taking again, and the ghetto darkness becomes even more dense, the faces even more hardened. The feeling is one of help- lessness, of no way out.

Then we cheer up. We think, We don't have to be that pessimistic. Soon better and brighter rumors are being spread. A few Latvian technicians and an engineer come down into the ghetto. They measure the buildings, make calculations-and that same day we learn that they are going to install electric lights. And we learn that they are going to open, officially, a Jewish folk school for the remaining children. The Germans are giving the Jews light and education! That is not only good and proper, but it is a clear indication that they count on us, that they care for us. Possibly, it is a sign that they will allow us to live. They are, after all, bringing in light for us!

We tell ourselves that the clouds are clearing away, that the Germans have driven out of themselves their dark thoughts. In reality, life is'bad, bitter in the ghetto, but people want to live, live, live....

Neither the Jewish ghetto-committee leaders nor the ordinary people have

[Page 47]

enough experience to comprehend how systematically the plan to exterminate the Jews is being carried out. No one knows how false, deceptive, and cunning the methods of the Nazis in power are.

The “Great Action”

On November the 7th, 1941, they divided the Dvinsk ghetto in half, and between the two halves they set up, in the long courtyard, a partition with barbed wire and a narrow little door to go through.

On November the 8th, a German manager, with the Latvian commandant and policemen, made a quiet, objective selection. The elderly fathers and mothers, the children without parents, and entire families that could not show that someone among them worked-all of these people they drove over into the smaller half of the ghetto and hermetically sealed off. How “guilty” the elderly fathers and mothers felt that day! How tearful were the children who had to “give up” their fathers and mothers! Only a few of the older people were successful in saving anyone, by hiding them in a clever way under baggage or in the outhouse pit.

Starting in the evening, those who had been selected were led out of the ghetto. We never saw any of them again.

On the morning of the 9th of November, after a sleepless, difficult night, a dreadful, indescribable feeling enveloped the remaining Jews. The ghetto was surrounded by German and Latvian police! They allowed no one to leave, not even the “most important” city workers! Today they were going to select again, because yesterday the necessary quota had not been reached! What to do? What to do?

Before long the Latvian policemen were running like wild animals across all the living spaces, ransacking every little comer, beating and battering anyone they caught in a hiding place, chasing everyone into the ghetto courtyard. There a new sorting out began-who to live, who to die....

After a selection that lasted many hours, the workers with their families, the entire medical personnel with their associates, and the ghetto-committee members with their families, assistants, and protected close relatives were separated from all the others-that is, from the condemned, who were led away to the sealed-off part of the ghetto. For them there was no longer any hope.

Then they separated us, the workers, from our families, and after a strict, thorough investigation, they sent us into town to our work. However simultaneously tragic and comical it may sound, we did feel fortunate and privileged, because our families were immediately provided with “red permits” or “life tags.” These special red tags were supposed to protect the wives and children of the men workers.

Yet I marched off into the town with a broken spirit. Nothing agreed with me

[Page 48]

that day-not food, not work, not rest. ... All of us workers were uneasy. We wanted evening to come as quickly as possible. We wanted to run to the ghetto and see what was going on there, and how our families were faring. Then all at once, something like a current of electricity cut through our minds. One of our German masters came from the ghetto and told us matter-of-factly, “I think they have also taken those with red permits. They did not have enough people for the necessary quota.... The Jewish wives and Jewish children shouted! They screamed like pigs when they were dragged off to the trucks.”

I don't remember exactly what occurred with me then. Without even considering that such an infraction of the rules might carry a death penalty, my friend Laib Bobrov and I threw down our work and in one breath ran away to the ghetto. No one prevented us from going in. A dead silence reigned there. On the bloodied ground dead people were lying everywhere. Blood was mixed throughout with fresh, wet snow.

We ran into the block where our families had been living, we searched, we called out, we ransacked every little comer, but there was no one there. From a dark little comer, from a pit under the floor, a young boy crawled out, frightened to death, and told us the news-that they had taken all of them, not from the courtyard but from our block. He alone had heard the whole thing from his pit, under the floor.

All the more heart-rending were the screams of the others who came back later and did not find their family members. A night of lamentations and of sharp biting pain went by, and in the morning, we were, like dull, dumb beasts, driven to our senseless slave labor. And again we had to look the murderers in the face, toiling for them, and smiling, when our hearts were bursting into pieces....

With that, a chapter of ghetto-life was locked away for me. My personal life lost all taste, every interest and value. Gone was the bright figure of my wife, Chava. The ebullient Gideon was not there; the delicate Avremele was gone. There was no one to care.for, or to live for, and-what was there for me to do in this world? What was still holding me among the living? Nothing.... Everything, all was already lost! Why go on living on the dark blood-soaked earth?

In the first hours, and also later, in the first days, in moments of hopeless pain and despair, I was close to suicide. To throw myself out of the attic window onto the cobblestone pavement and let everything be ended with the malicious earth...to go to my own people, the departed near and dear ones, to be together with them.... It would not be at all difficult, I thought. One has only to go over to the window, open it, crawl out, and ...be finished with the world of animal men, the world of inhuman crimes and endless suffering.

But bit by bit other thoughts began to press into my mind. Why should I go away of my own free will, run away like a coward from the mean world, and not even lift a finger to take revenge on the heartless villains and criminals, the cold and conscienceless mass murderers, the beasts in human form? After

[Page 49]

all, sooner or later there will come, there must surely come the longed-for hour of revenge-the holy revenge and the bloody reckoning of accounts that the freshly spilled blood of our fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and wives and children demands of us, of those who still live! Revenge! Revenge! That was surely the last shout, the last groan, the last gasp of breath with which they, the fallen victims, gave up their souls! Revenge-that is certainly the holy and eternal commandment for us who are still alive, for the coming generations! How dare I end my life by myself, I who can perhaps be useful? How can I allow myself to walk away from my holy debt to those slaughtered people, to my mother, to my wife and children, to my brothers? No, I must not do that. I must not!

Thus, approximately, did my thoughts spin around at that time, as did the thoughts of thousands of others in the inescapable sorrow for the family members who perished. We despaired, and we hoped to transform our blazing thoughts of revenge into blazing revenge deeds.

From then on, after the destruction of my family, I became obsessed with a single burning thought, a single goal-to run away, flee, escape! There was no longer anything, not one living person dear to me who might, as in the past, keep me bound to that place, to that environment, the ghetto. I was a “free man,” a single person, abandoned, cut off, tom out, a rootless thorn, and I could now walk and run and drag myself around in God's custody. There was no longer anyone to care for, no longer anyone to cling to. I was “free” from everything....

I must run away, I thought, and accomplish something, for as long as my life lasts!

And that is what I was later destined to do-run away to the woods and kill, stab, shoot, and spill the impure, beastly blood of the murderers.

Close to five thousand Jews from the Dvinsk ghetto vanished in the so-called great action of the seventh, eighth, and ninth of November, 1941.

| To the eternal memory of my nearest and dearest-Chava, Gideon, and Avremele-perished on the ninth of November, 1941, in the Dvinsk ghetto

Two children, like delicate flowers,

Children joke, laugh, make noise... |

[Page 51]

|

| Quickly flown away, like the spring, Are these happiness-filled days. What has led to the deep abyss Is the unfamiliar path of fate.

A war has broken out

The blood of children flows like water...

Tiny children hang and scream

Children thrown into the air

Lamentations, torture and death screams...

And among the thousands of victims

Childish souls are complaining,

My life is also extinguished, |

[Page 51]

|

There is no mother, and no children There is no more light, nor joy.

But do not suppose, you child-killers,

For the blood of children and mothers

For the blood of children, mothers

I, in concentration camps, in chains,

(Written in the concentration camp of Dvinsk, 1942.) |

In Honor of the Holiday of May 1st

No more than a thousand Jews, all together, remained in the town and ghetto of Dvinsk after the great action. Once the ghetto had been cleansed of dead bodies, blood, and scattered baggage, after the remaining Jews had been recounted and reregistered, the long procession of ghetto-days resumed, without hope for anything better. But of the ghetto's once crowded conditions there was no longer even the slightest reminder. Space and “comfort” had now become more than sufficient.

I and other town workers were by that time “barracksed” which is to say, housed and settled in the town itself, near the workplaces. Our work-group, the “well-integrated” tank job workers, consisted of about twenty-five people, almost all lonely, dried-up single men, cut off from once-blooming families. That was approximately what the rest of the work groups were like as well. There were a dozen or so workplaces with a couple of hundred Jews in Dvinsk.

The ghetto had meanwhile been hermetically locked away from the whole world. None of the remaining Jews were allowed in or out. Every outside delivery of food was halted. The roughly eight hundred Jews there were burdened with unusually hard, exhausting work. They suffered terribly from hun-

[Page 52]

ger, they were constantly beaten and terrorized, and for a variety of “crimes” they were shot or hanged. Nevertheless, by means of the hardest work, all hoped to save their lives.

I heard a few sad tales about those “quiet” ghetto-days. The wife of Meyerov, who had until then been able to save herself together with her five small children, was shot to death in the middle of the ghetto for trying to trade a tablecloth for a few pounds of flour. It wasn't long before her five little children were also liquidated.

The wife of Goetz, born Gitelson, was hanged in the middle of the ghetto, and remained hanging on the gallows for three days, allegedly for going without a yellow badge. The most gruesome and outrageous aspect of this incident was that the oldest Jewish police officer, Pasternak-actually a decent and honest man, a Jew from Kreslav-was forced to hang her. They threatened to hang his own small children before his eyes if he refused.

A young girl, Mashe Schneider, was hanged in the ghetto for hiding herself and for living by means of “Aryan” documents.

Such cases of hanging and execution by shooting, which were intended to frighten the last Jews in the ghetto and break their spirits, one could count by the dozens. But what value did individual human lives have when the fate of everyone had already been signed and sealed?

In honor of the “Jewish-communist” holiday of May 1st, they finally assembled a large group of Jews, the “last of the Mohicans,” including the head Jew Mischa Movshenson, the ghetto-committee, and the ghetto aristocrats. They took them down the well-beaten path to the mass graves of Dvinsk. This time the cruelty and beastliness of those who gathered the condemned together was more horrifying than ever. Little children, the sick, and those who had been hiding were shot right where they were with explosive bullets. They had their stomachs ripped open, or were thrown down from second-story windows. The dead were hurled about, some with a hand or a foot missing, and blood was spilled over the entire ghetto area. The remaining several dozen Jews, when they returned from their workplaces, had to collect the bits of flesh and blood rapidly, and clean up the ghetto.

In that fashion, on the 1st of May, 1942, the Dvinsk ghetto, in the old Dvinsk crepost on the opposite bank of the Dvina River, was liquidated. It was replaced by one more of the huge Jewish cemeteries. At that time-and even earlier, after the great action-a few dozen Jews of Dvinsk who had close relationships with town farmers succeeded in running away to Braslov, a town in Byelorussia a little over forty kilometers from Dvinsk. From the farmers and from the accounts of those who had run away but were brought back to Dvinsk, we learned that the Braslov area was a paradise. There were no ghettoes there. Jews remained comfortably in their own homes, and went around half-free, required only to wear yellow badges and keep away from others.

[Page 53]

We could not believe that there could still be such a happy life for Jews. Hundreds of us, and others with their whole families, got ready to run away to Braslov. But you had to h we a lot of money and valuable articles to pay the farmers for driving you there. Worse, the whole undertaking, which included putting yourself completely in the hands of your escorts, was risky. And in fact, a few of the escorts had “sold out” Jews, abandoning them or handing them over to the Germans. Nevertheless, my friend Bobrov and I were determined. We made a verbal agreement with a farmer and were ready to run away to Braslov.

But suddenly dreadful rumors began to circulate. It was said that they had slaughtered all the Jews in Braslov, and also the Jews of dozens of the surrounding villages. Afterwards, the news was confirmed. At the beginning of June, 1942, they had killed close to two thousand Jews in Braslov-the locals together with those who had come from Vilna, Dvinsk, and other places. It turned out that all who had fled there from Dvinsk had perished; I did not hear of any one of them who survived.

We who remained in Dvinsk decided to spare ourselves that flight to Braslov. The same bloody death we knew so well had marched there also.

“Let Us Eat and Drink, For Tomorrow We May Die”

After the liquidation of the small-ghetto, 430 Jews remained in Dvinskmen, women, and a few dozen children. Of these, 180 lived in the town of Dvinsk itself, in a dozen military workplaces, and 250 were housed in the citadel on the Dvinsk side of the Dvina River. There a few dozen craftspeople and others were assigned to sort out, clean, and repair old military uniforms and footwear for the German army.

That is the way things proceeded until the 28th of October, 1943. In this period, famine was unheard of. On the contrary, we came into frequent contact with the Christian population, with whom we traded various things for food, and we traded among ourselves also, so that no one experienced any shortage of food.

Under those conditions, there naturally emerged a new group of relatively well-to-do people, mostly merchants who owned quite substantial enterprises, and they carried on a conspicuously extravagant way of living, indulging themselves in gluttonous feasting and drunkenness. They played cards and held mindless balls and wild parties. For the most part, they were not evil by nature, but they were without principles, and had unbridled instincts, base inclinations, and limited understanding, all of which, together, earned them a reputation as underworld types. Such were the people who, in that last year, became the opinion makers and “community leaders” among the last group of Jews in Dvinsk. The Biblical saying “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we may die” (Isaiah, 22: 13) summed up their entire philosophy of life.

I would often think about, and discuss with a few of my closer friends,

[Page 54]

these questions: How do people come to have such a weird drive for illusory power? How is such blindness, egotism, injustice, and uninhibited animal behavior possible at a time when death hovers over all of us? I used to be astonished that in the midst of our darkly tragic life anyone could feel the urge for the lowest animal pleasures, for love affairs, shady business deals, wealth, importance. I could not comprehend how they could forget what was happening to us. Did they not grasp that we were lying trapped in the net, enslaved, under lock and key, with the slaughtering knife over our necks? Even today I still can't understand it. It seems that the rotting soil and abnormal life of ghettos and concentration camps nourished the lowest and darkest of human instincts, and brought to the surface the dirtiest side of the human soul. In such an upside-down life, the refuse apparently rose to the top of the heap.

What kind of complex psychological explanation could there be? Science and authorities on the human soul will have a wide field to research before they can offer a clarifying word on the subject.

The “good life” in Dvinsk, not counting a few shootings, lock-ins, beatings, and so on, persisted until the first weeks of October, 1943. Then a variety of nerve-wracking rumors began to spread around again, and the more they spread, the more people became anxious. We heard that the Russian armies were getting closer to Dvinsk, and that this was bound to seal the fate of the remaining Jews. It meant liquidation, final annihilation, death.

Some of the Jews had, from time to time, provided themselves with morphine or other poison with which to commit suicide, and others, mostly among the younger and more daring, prepared to run away. They hoped to hide out or join a partisan group and fight the Germans. Although farmers in the region had talked about partisan groups, which were supposed to have operated in the woods sixty to eighty kilometers from Dvinsk, many had little faith in that talk. They were frightened, and reasoned that one could not hope for any help or cooperation from the Christian population. One expected just the opposite-denunciations, persecutions, robbery, and violence.

Then a case occurred in which a few Jewish boys and girls ran away with some Russian prisoners of war who lived and worked in the citadel. The Jewish young people were hoping to connect up with partisans. But it turned out that the Russians had deceived them. They stripped them naked and took everything from them. The last ones fell into the hands of the Germans and were shot. That case made the Jews even more wary of running away.

There was no well-organized partisan movement among the Jews or in Dvinsk generally. The Jews were cut off from other Jewish settlements (kibutzim), so they had no leaders to show what might be possible. Nevertheless, a few dozen young people did run away. Some were caught and immediately paid with their lives, but others finally joined the ranks of Russian partisan groups. The most heroic was Ruvke Feldman, a healthy, simple young man who, together with a few friends, ran away from Dvinsk early on, in 1942. He

[Page 55]

lived in the woods, and then met up with Russian partisans and fought with them. It is possible that he died in battle, or remained in the Russian army, but he never came back to Dvinsk.

Among the active partisans from Dvinsk who remained alive, I later met Elke Gever, Chaimke Gordon, Yakov Israeleet, and Yitzchak Pachter. Of any other survivors we never heard anything.

The Final Liquidation of Jews

The final liquidation of Jews in Dvinsk and surrounding communities took place on October the 28th, 1943. At that time there were no more than four hundred Jews in town and in the citadel.

On October the 28th, quite early in the morning, while it was still dark out, bloody Latvian policemen suddenly surrounded and cut off all the workplaces and living quarters of the Jews. They ordered everyone to pack up their most useful things and get ready to go.

A fearful confusion came over everyone. No one imagined anything but that they would be led to their death, to prepared burial pits. And although no organized resistance took place (and could not have taken place among the scattered little groups), people nevertheless reacted in a variety of ways to the prospect of their last journey. In the citadel a great tragedy played out, of which I offer here a few images.

The more courageous young people were armed with revolvers, and they attempted to mount a resistance and run away. A few of them did in fact succeed in saving themselves, but the others were captured and shot right there or beaten to death. These heroic young people were the first to fall: Yudl Munitz, Dovid Bleier and Dovid Vechsler (the latter from Ponavesz, Lithuania), and a few others whose names I no longer remember. They wounded a few of the policemen, and as was afterwards recounted, killed four of them. Infuriated S. S. officers and other policemen meanwhile turned over every little comer in the citadel, dragged out those who had been hiding, and threw them, bloodied and battered, into the courtyard.

Other horrifying scenes involved suicide, or murder of relatives together with suicide. In the dilemma of despair, with no way out, dozens of people shot or poisoned or hanged themselves.

Dr. Hirsch Goldman gave large injections of morphine to a few people who requested it, and at the end, he did the same for his only sister and himself. Lying dead on their beds, they looked like people who had been frozen alive.

The butcher Bentzion Sapir poisoned his wife and seven-year-old child. Then, seeing how much they were suffering, he finished off his wife with a bullet and choked his child to death with his own fatherly hand. He himself lost his mind. He remained alive for a certain period, but I don't know what happened to him later.

Bentzl Katz shot his own mother, the lone survivor, besides him, of the

[Page 56]

whole family. He himself fled into the surrounding woods, committing himself into God's care. Nothing is known of his subsequent fate.

Opeskin and a few others hanged themselves at the very moment when the authorities came to get them. Others who tried to hang themselves were taken down off the rope, revived, and brought to the courtyard.

All of the assembled Jews from the citadel, from the town workplaces, and from the town “mini-ghetto” (a locked-up, isolated courtyard at the corner of Postoyaler and Rieger Streets, where they kept a hundred Jews)-all of those Jews were brought, under strong guard, to the freight train station, and there they were loaded into wagons to be transported away. At the last minute, a few Jews ran away and disappeared, having bribed Latvian guards with whom they were acquainted.

In that fashion, Dvinsk was supposedly left clean of Jews, or in the German terminology, “Juden-Frei,” not counting a couple of dozen who had hidden themselves and a couple of dozen craftspeople who were left behind by direct order of the Gestapo. But in fact, more Jews remained.

About the Jews of Dvinsk who survived, and those who returned from Russia, I will give an account later, in the last chapters.

Freight Cars Filled With the Dead

Whither were they transporting the “last Jews” of Dvinsk?

No one among us knew anything about it at first, not even the Latvian escorts and guards of the action. To death, to the crematoria-that was their simple answer. Tightly pressed together in freight cars, without food and drink, with the doors and windows locked tight and wired shut-that is how they drove us for three days and nights.

Another dozen people or more committed suicide. A few took poison, drinking up bottles of morphine, and afterwards suffered for hours, roaring and writhing, with foam on their lips. Seeing that the morphine was having too weak an effect, others both poisoned themselves and hanged themselves. In our car three people hanged themselves, almost before everyone's eyes, and nearby a certain Syoma Fagin, a lively youth who was very fond of strong drink, first got drunk on brandy and then attempted to hang himself while halfstanding on his knees. Like a person possessed, he roared, begging his friends to help him end his life. And they really did help him, hanging him up in the proper fashion. There are no words that can convey how those scenes affected the rest of us, pressed together in the same freight car.

How does one comprehend the inner turmoil of healthy, life-loving people who are being driven in locked and crowded freight cars like animals to the slaughterhouse? Can human language describe such helplessness and hopelessness? We had, by that time, heard a great deal about various crematoria, modern gas chambers, and coke-ovens in Poland and Germany. We had grasped that all Jews, without exception, were to be liquidated, annihilated,

[Page 57]

rooted out. The obvious conclusion to draw was that we were among the “last Jews,” that we were being driven down that same road as the others before us.

Under the impression of such horrible scenes and tragic thoughts, there took form in my brain a kind of farewell, addressed to myself and other Jews still on earth. Later, I wrote down the words on paper, and it turned into a kind of song with the title “Our Testament” or “The Testament of Generations.”

Yet despair was not the only thing I felt. However desperate our plight, the majority of us confined in the freight cars had not given up the idea of breaking out and saving ourselves. Deep down in my soul I felt that they were not yet taking us down that last road, and that better opportunities would still present themselves for running away, but I nevertheless talked over the idea of breaking out with my friend Laib Bobrov and a few others who were daring and embittered. We took to breaking the car's small windows and tearing off the barbed wire. We prepared ourselves to crawl through and jump off the moving train. Our plan was not successful; the S. S. guards noticed what we were doing, began shooting, and wounded two of us in the hands. But in another freight car a few Jews did crawl through a small window and jump off the train while it was moving.

In the end, it turned out that although the road we traveled was tragic and dark, it was not yet the last road. We were destined, this time, to remain alive, as we will later see.

| Do you know, Jew? Where blood cries from the graves, From mass graves, long and wide tombs, There your brothers fell down dead, There your father and mother lie dead! Do you know, Jew? Where souls still wander, lost, The tortured souls of a mother, a father, a child, There the heavens and the earth cry: Revenge! Vengeance for the horrifying sin!

If l should be mortally wounded by a murderer If I should fall dead today or tomorrow, |

[Page 58]

| And if you are the last Jew on earth, Then should you be the father of new tribes, Be the planter, the builder, and the shaper of them. Implant in them the strength and purity of spirit That belongs to the people that will forever live In spite of all those-the Hitlers, the enemies, Who strove so mightily to annihilate us.

And if my body should already be dead, deceased,

(Finished in the Popervaln concentration camp, 1943.) |

|

|

(Photo: G. Kadish, Kovno ghetto, 1943) |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

We Want to Live

We Want to Live

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Feb 2018 by LA